94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Rehabil. Sci. , 21 October 2021

Sec. Disability, Rehabilitation, and Inclusion

Volume 2 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fresc.2021.705474

This article is part of the Research Topic Exploring Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour in Physical Disability View all 10 articles

Gita Ramdharry1,2†

Gita Ramdharry1,2† Valentina Buscemi1,2

Valentina Buscemi1,2 Annette Boaz3

Annette Boaz3 Helen Dawes4

Helen Dawes4 Thomas Jaki5,6

Thomas Jaki5,6 Fiona Jones3,7

Fiona Jones3,7 Jonathan Marsden8

Jonathan Marsden8 Lorna Paul9

Lorna Paul9 Rebecca Playle10

Rebecca Playle10 Elizabeth Randell10

Elizabeth Randell10 Michael Robling10

Michael Robling10 Lynn Rochester11

Lynn Rochester11 Monica Busse10*†

Monica Busse10*†Rare neurological conditions (RNCs) encompass a variety of diseases that differ in progression and symptoms but typically include muscle weakness, sensory and balance impairment and difficulty with coordinating voluntary movement. This can limit overall physical activity, so interventions to address this are recommended. The aim of this study was to agree a core outcome measurement set for physical activity interventions in people living with RNCs. We followed established guidelines to develop core outcome sets. Broad ranging discussions in a series of stakeholder workshops led to the consensus that (1) physical well-being; (2) psychological well-being and (3) participation in day-to-day activities should be evaluated in interventions. Recommendations were further informed by a scoping review of physical activity interventions for people living with RNCs. Nearly 200 outcome measures were identified from the review with a specific focus on activities or functions (e.g, on lower limb function, ability to perform daily tasks) but limited consideration of participation based outcomes (e.g., social interaction, work and leisure). Follow on searches identified two instruments that matched the priority areas: the Oxford Participation and Activities Questionnaire and the Sources of Self-Efficacy for Physical Activity. We propose these scales as measures to assess outcomes that are particularly relevant to assess when evaluating physical activity interventions mong people with RNCs. Validation work across rare neurological conditions is now required to inform application of this core outcome set in future clinical trials to facilitate syntheses of results and meta-analyses.

Rare neurological conditions (RNCs), where cases are ≤40 per 100,000 population (1), collectively incur a significant cost burden to healthcare, social care services and informal care (2). Despite variability across conditions, many of these conditions will share symptoms and signs at the level of body function, activities and participation (3). As such, common approaches to improve fitness (e.g., cardiovascular and strength training), activity (e.g., balance and gait training) and participation levels (e.g., supported self-management) are often implemented in clinical practice (4–8).

Physical activity is any bodily movement produced by the muscles that require us to expend energy and can include structured exercise, active transportation, household chores, and activity during work, play and recreation (9). Whilst trials of physical activity interventions in RNCs highlight the potential of physical activity interventions to improve fitness and function (10–13) they are often small studies that fail to influence clinical practice. There are a variety of factors that limit the impact of these trials, not least the selection of outcome measures. Measurement constructs may vary from physiological measures (e.g., strength and fitness), to functional assessments (e.g., walking speed, climbing stairs) or quality of life and well-being outcomes and do not typically take into account patient preferences (14). If we are to ensure that research is relevant and able to influence clinical practice and future research, we need to ensure the use (and reporting) of standardized, relevant outcome measures within the field that are applicable to people living with the conditions (15, 16). Importantly, it should not be assumed that measurement should be restricted to the agreed core outcomes but rather that these outcomes should always be gathered and reported to facilitate evidence synthesis across relevant trials and studies. Core outcome sets have been agreed for specific target conditions for example cancer, rheumatology and chronic pain as well as for specific care pathways for example maternity care (17, 18).

Core outcome sets have also been proposed for people with neurologic conditions (19), including adults with dementia (20). However, these core sets have not been tailored to physical activity interventions for people living with RNCs. Recommending measures would not only help to bring consistency in reporting, allowing comparisons or meta-analysis of future studies, but also ensure responses are measured of constructs important to people living with RNCs. This study focuses on the development of an agreed standardized set of outcomes termed a “core outcome set” (21) that should be at a minimum measured and reported in trials of physical activity interventions in people living with RNCs.

The study followed the guidelines of the COSMIN (COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments) and COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) initiatives. A four step approach was used to select outcome measurement instruments recommended within core outcome sets (21). The activities relevant to each step within the process are described in detail below.

We focused on groups of progressive RNCs, namely neuromuscular diseases, Ataxias, Huntington's Disease (HD), Atypical Parkinson Diseases (AP), including Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, Multiple Systems Atrophy, Corticobasal Degeneration, Motor Neuron Diseases (MND) and Hereditary Spastic Paraparesis (HSP). These conditions affect ~2–10 per 100,000 in the general population, collectively leading to limited mobility and poor balance for many individuals. People with neuromuscular diseases and MND experience profound weakness and muscle atrophy. People with Ataxia, HD, AP, and HSP experience difficulty controlling movement, with some muscle weakness and variable cognitive impairment. Many people across the conditions also experience pain, joint deformity, fatigue and depression which impacts on their ability to participate in routine activities of daily living.

People living with RNCs, carers of people with RNCs and representatives from five collaborating support groups and charities, namely the Muscular Dystrophy Association, Ataxia UK, HSP support group, PSP Association, HD Association of England and Wales were invited to join a stakeholder group. They attended an initial workshop (Workshop 1) to define conceptual considerations in relation to the physical activity interventions and outcomes in our target population, namely, people living with RNCs.

This was followed by a second stakeholder workshop (Workshop 2) with people living with RNC and the relevant charity representatives. They worked together to (a) explore issues and experiences relating to physical activity in the face of living with a RNC and (b) identify and priorities key constructs and domains of importance that would need to be measured when evaluating a physical activity intervention. Representatives from RNC charities were asked to gather views from their members living with RNCs prior to the meeting through their communication channels, e.g., surveys and social media platforms.

We conducted a scoping review of systematic reviews published between January 2008 and December 2018 to identify outcome measures used to measure efficacy of any type of physical activity intervention for adults with neuromuscular diseases, motor neurone disease (MND), HD, PSP, multiple system atrophy (MSA), inherited ataxias and HSP (Open Science Framework registration: https://osf.io/4cr32/). The research team, experts in this field, were aware that little research into physical activity had taken place until the early 2000s and reviews came later, hence the 10-year window. Studies were included if participants were adults and if the reviews reported at least one outcome measure to evaluate the efficacy of the physical activity intervention at either the body structure/function, activity and/or participation levels, according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (20). Constructs and domains of importance identified during Workshop 2, were matched with outcome measures identified in the scoping review. Where no measures matched the identified, domains, additional literature searches were done using the domain descriptions as search terms. Additional criteria for selection were use in RNC or other neurological diseases. Two of the descriptors, motivation and confidence, relate strongly to self-efficacy so this was also added as a search term. Elicitation of stakeholder opinions during a series of virtual meetings was undertaken to supplement this process and to identify proposed outcome measures that were consistent with the domains of importance identified by the stakeholder group.

Outcome measurement instruments that are included in a core outcome set should ideally be reliable and valid for use in the target populations (22). Feasibility of use is a further consideration. The rarity of the diseases being studied meant that the psychometric properties of the measurement tools we identified had not been examined in these conditions. We thus considered the psychometric properties of the tools as applied to more common long term, neurological conditions where there were indications of some common impairments. The evidence for each was collated for presentation at step four.

The outcome measure instruments under scrutiny matching the agreed domains of importance were examined by individual researchers then presented to the wider research team for technical discussions of the psychometric properties through a series of video meetings. Following the video meetings, lists of items assessed within each instrument were sent to the stakeholder group via e-mail to elicit further reflection on their relevance to the constructs of importance. A final face to face stakeholder workshop (workshop 3) and consensus procedure was undertaken to agree on the instruments for each outcome to be recommended for inclusion in the core outcome set.

People living with RNCs (workshop 1 N = 5; workshop 2 N = 3), carers (workshop 1 N = 1) and charity representatives (workshop 1 N = 5; workshop 2 N = 5) considered it important that measurement tools were able to detect outcomes across domains of (A) function and well-being and (B) participation in activities. In terms of (A), staying well, ensuring good sleep and maintaining positive mood were of highest priority whilst in relation to (B), the ability and confidence to take control and make choices along with normalization of participation and social engagement were important. Through further discussion, the stakeholder groups agreed that these aspects were well-centered around (i) physical well-being; (ii) psychological well-being and (iii) participation in day-to-day activities as the primary domains of meaningful importance. Relevant constructs within the physical domain were physical function and independence. Constructs in the psychological well-being domain were emotional well-being, mood, enjoyment, motivation for physical activity and confidence, whilst leisure activities, work and activity that matters (personal choice) were constructs of importance within the domain of participation.

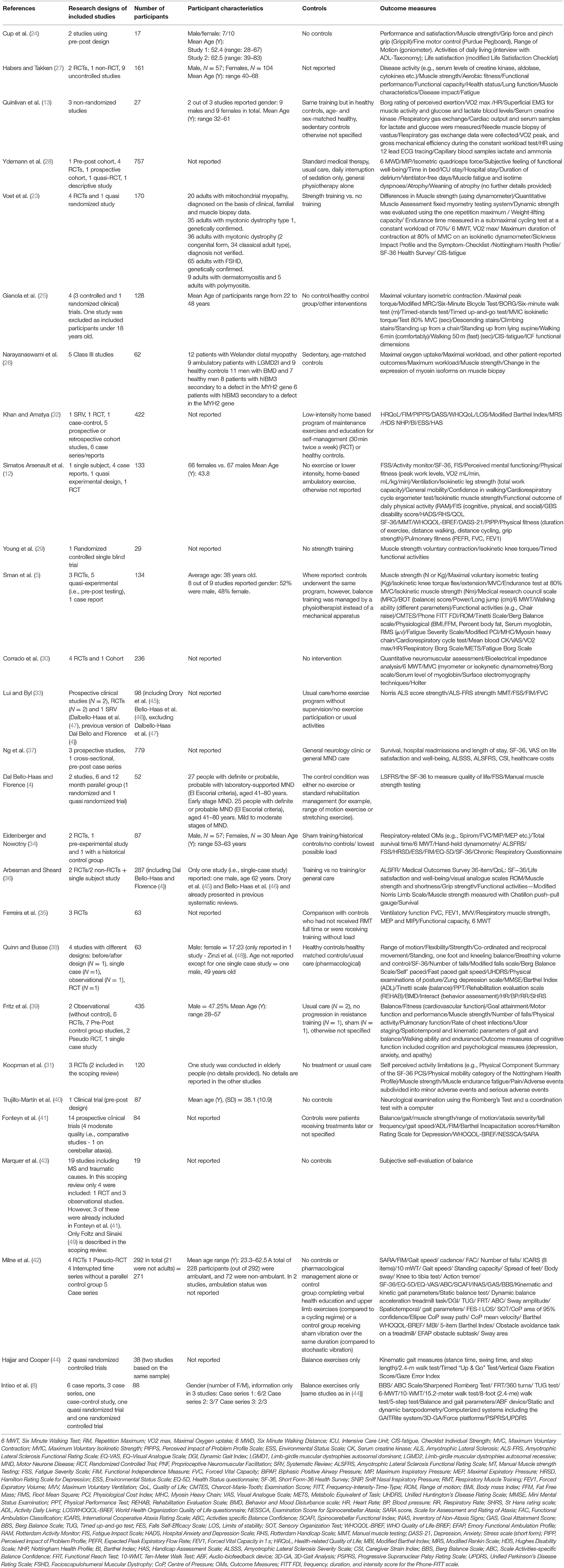

Database searches identified 5,435 articles, and, after removing duplicates, 4,433 were screened by titles and abstracts, leaving 62 articles for full-text eligibility assessment. They were screened and 27 were included in the scoping review (4, 5, 8, 12, 13, 23–44). The results of the scoping review will be presented in detail separately. Nearly 200 outcome measures assessing outcomes of structured physical activity interventions (Table 1) were identified within these 27 articles. Dosage, intensity and duration of training regimes were highly variable but typically involved strength training, aerobic and respiratory, functional training and combined programs with very few focusing on physical activity behavior change.

Table 1. Characteristics (including outcome measures utilized) reported in studies included in scoping reviews of physical activity interventions in RNCs.

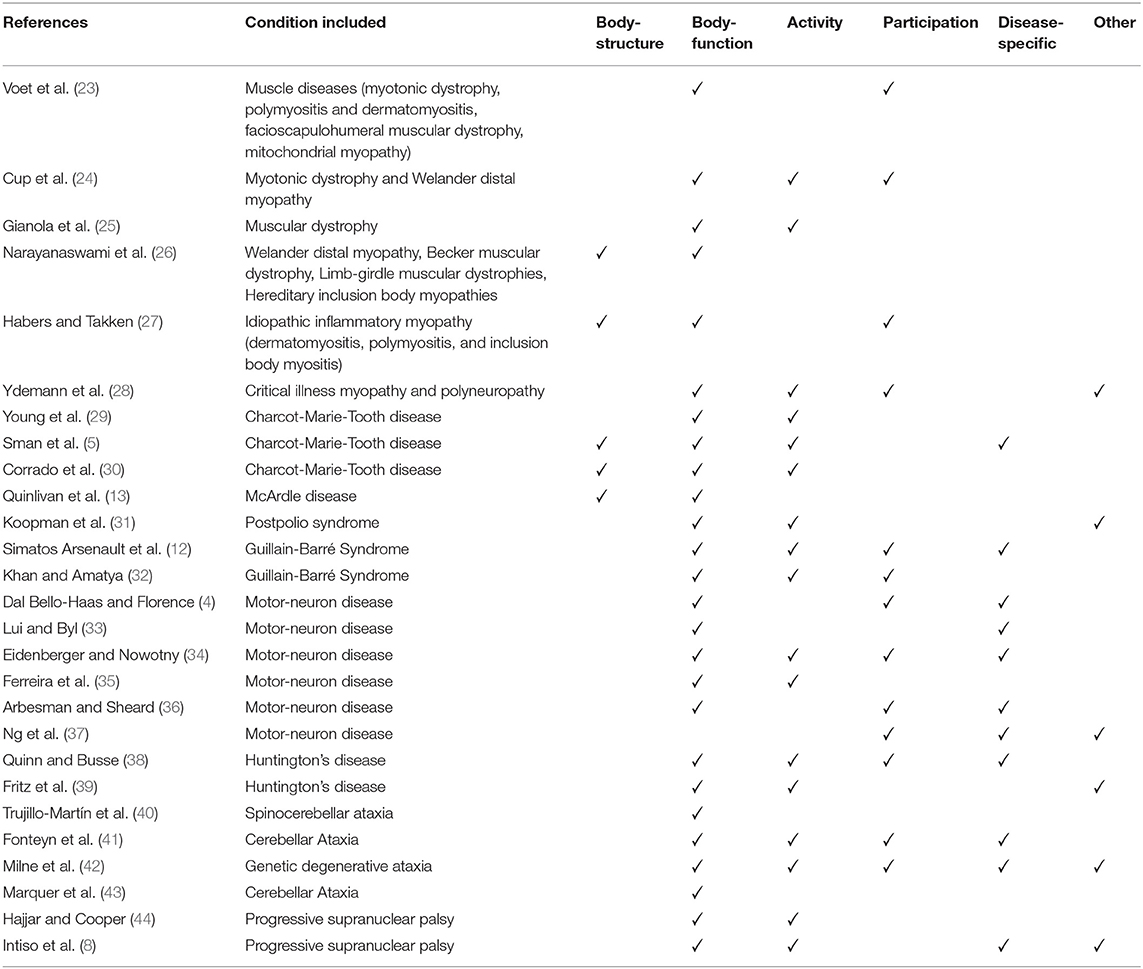

We mapped each outcome to the World Health Organisation International Classification of Function (ICF) domains (20) (see Table 2). The majority were related to function and activity. Outcomes reflective of both body structure impairments and participation were less frequently reported. Two domains were categorized as “Other” (e.g., Goal attainment score), and “Disease-specific” questionnaires (e.g., Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale or Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia).

Table 2. Mapping to World Health Organisation international classification of function ICF) domains.

Eleven reviews utilized disease-specific outcome measures, while in six reviews measures were not able to be represented within the ICF domains (i.e., in the “Other” category). Most studies (n = 17) included outcomes that were representative of three to five different domains. Notably, there was no evidence of stakeholder engagement or involvement of people with the condition being investigated in the selection of measures used as primary outcomes.

Constructs relevant to the physical and psychological well-being, and participation in day-to-day activities domains were cross-checked with the outcomes synthesized in the scoping review. No single outcome measurement instrument that addressed all three domains was identified. Measures were usually tailored to specific activities or functions (e.g., on lower limb function, ability to perform daily tasks). Alternative outcomes reflective of well-being were reviewed by stakeholders through a series of group discussions. None of these comprehensively matched the domains of importance identified in Step One.

Further literature searching resulted in the Oxford Participation and Activities Questionnaire (Ox-PAQ) (50, 51) being identified as an instrument that matched the majority of the constructs highlighted as relevant in Step One and has been used in one RNC disease group and other neurological conditions (50). Three constructs (i.e., enjoyment, motivation and confidence) are important predictors of physical activity behavior and not assessed within any of the Ox-PAQ items but are relate highly to self-efficacy. The Sources of Self-Efficacy for Physical Activity (52) was thus identified as an additional secondary outcome able to reflect these constructs. Other self-efficacy scales found in the search were specific to particular diseases and populations but did not include neurological conditions. It is important to note that these outcomes were not only reflective of that which is important to stakeholders but also additionally are able to provide mechanistic insight for researchers.

The OxPAQ questionnaire is a short, 23-item, patient-reported outcome measure, that has been specifically developed for cross-disease application and validated in three long term neurological conditions (MND, Parkinson's disease, Multiple Sclerosis) (50). It was developed using patient interviews and expert reviews and has a manual and online scoring. The Ox-PAQ reports on three domains, Routine Activities (14 items), Emotional Well-Being (5 items) and Social Engagement (4 items). Routine Activities assesses individuals' capacity to engage in regular activities that form the basis of daily life. Emotional Well-Being provides an indication of current mental health status, while Social Engagement assesses whether individuals can maintain relationships, both personal and from a wider community perspective. Internal reliability is high (Cronbach's α 0.81–0.96) and validity was demonstrated against relevant domains of the MOS SF-36 and the EQ-5D-5L (50). Sources of Self-Efficacy for Physical Activity is an 18-item questionnaire that measures six aspects (3 items for each source) of self-efficacy for physical activity, specifically: mastery experience, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion by others, self-persuasion, negative affective states and positive affective states (52). Items were pooled from prior qualitative studies, scales of feelings induced by physical activity and sources of self-efficacy more generally. It was refined in a study of 1,406 German adults through principal axis analysis with inter-related factors and confirmatory factor analysis. It is a reliable (Cronbach's α 0.75–0.93), valid (convergent and discriminant). It has not been validated in neurological populations, but the scale was designed to be generally inclusive allowing it to be applied across conditions and populations (52). Other self-efficacy scales target specific conditions and were not generalizable or applicable to people with RNC.

Following broad group communication and discussions and a final face to face consensus procedure involving small group discussions, it was agreed that the Ox-PAQ and the Sources of Self-Efficacy for Physical Activity measure should be assessed in trials evaluating physical activity interventions across RNCs given the ways in which they matched the domains and constructs of importance identified by the stakeholder group. This was a group decision by people living with RNC, charity representatives and the research team at the final workshop.

Physical activity research trials in RNCs to date have typically involved targeted exercise intervention and evaluation at the specific disease level despite these diseases leading to variable but similar impairments and functional impacts (for example fatigue, muscle weakness, balance problems, falls and difficulty walking). Our scoping review highlighted the prevalence of interventions, mainly focusing on structured exercise and typically underpinned by standard approaches (53) highlighting the role of physical activity and exercise as a critical enabler of participation for all those living with common and rarer long term neurological diseases (54). Our scoping review of the literature identified outcome measures appropriate for the specific body structure, function and activity level changes targeted by these interventions, but there was a degree of mismatch between these outcomes and constructs identified as important to people living with RNCs (e.g., assessments that capture changes at the level of participation).

We utilized a person-centered approach leading to the proposal of a meaningful core outcome measurement set for use when researching physical activity interventions for people living with RNCs. Our collaborative and participatory design involved members of the public, including people living with RNCs, representatives of charities and support groups for RNCs and is the first core outcome set to our knowledge which has specifically focused on physical activity interventions for RNCs. Stakeholder engagement is receiving increasing recognition in patient-reported outcomes research (18) and clinical trials (55, 56) so as to ensure that interventions and outcomes are relevant to the target populations. A core outcome set for disease modification trials for dementia has been developed with stakeholder input and involvement of the research community. This was achieved through a number of stages, including a systematic review of outcome measures, a consultation with patient and public involvement representatives and a final consensus reached with the dementia research community (20). A similar approach was used to develop a core outcome measure set for exercise studies in Multiple Sclerosis (57), where a group consisting of experts in the field, support group representatives and expert patients, jointly discussed a pre-defined core set for Multiple Sclerosis. This was based on the World Health Organisation International Classification of Function and included body structure and function, activity and participation categories. Our approach differed somewhat in that we initially elicited discussion and reflection from our stakeholder groups on the domains considered important when engaging in physical activity interventions, but without presenting any work undertaken in previous studies.

Outcomes identified in the scoping review assessed the effect of physical activity interventions primarily at the level of body functions and structures, functional activities. There were fewer identified outcomes at participation level, in contrast to the domains prioritized by our stakeholder group, namely physical and psychological well-being and participation to day-to-day activities. In the scoping review, measures of quality of life and health-related well-being were identified, but these did not (in the views of our stakeholder group) sufficiently capture the breadth of areas of importance in relation to participation and physical activity in RNCs. For example, the 36-Item Short Form Survey is more focused on levels of vigorous and moderate activities, rather than independence in day-to-day activities. The Ox-PAQ and the Sources of Self-Efficacy for Physical Activity measure were however considered to reflect meaningful outcomes of physical activity interventions for people with RNCs.

Whilst the identified and proposed outcomes are clearly relevant to people with RNC, it is not yet clear how well the measures perform within and between these populations nor whether they fully capture that which is meaningful to people with RNCs. For example, the Sources of Self-Efficacy Scale may not fully capture enjoyment for physical activity; it may be that a purpose developed enjoyment scale (58, 59) is more appropriate in different settings. The broad range of rare neurological diseases where physical activity interventions are indicated are a specific challenge. A key limitation is that we did not consistently have stakeholders present at all workshops with faster progressing conditions, those with significant cognitive disorders or carers, relying on the charity representatives to bring accounts of these experiences. People were invited, but the additional complexity of those conditions may have affected engagement in all steps. Future validation work will need to include these groups to inform the implementation of the proposed core outcome set.

We propose a core outcome set, developed in collaboration with people living with RNC and their representatives, for use in studies of physical activity interventions. The two measures proposed were selected to include domains of importance to people living with these diseases.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants, in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

GR and MB: conception and organization of the research project, design and review and critique of the analysis, and writing of the first draft and review and critique of the manuscript. VB: organization of the research project, design and review and critique of the analysis, and writing of the first draft and review and critique of the manuscript. HD: conception and organization of the research project, design of the analysis, and writing of the first draft and review and critique of the manuscript. AB, TJ, JM, LP, RP, MR, and LR: conception of the research project, design of the analysis, and review and critique of the manuscript. FJ and ER: conception and organization of the research project, design of the analysis, and review and critique of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was funded by an NIHR Programme Development Grant RP-DG-0517-10002 (Co-Chief Investigators: GR and MB). This is a summary of independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)'s Programme Development Grant Programme. Centre for Trials Research receives funding from Health and Care Research Wales and Cancer Research UK. Open Access funding has been made available from Cardiff University.

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We would like the acknowledge the input of our stakeholder groups and charity representatives from the Muscular Dystrophy UK, Ataxia UK, Hereditary Spastic Paraparesis support group, Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Association, Huntington's Disease Association of England and Wales, Multiple Systems Atrophy Trust, Motor Neuron Disease Association. The scoping review that formed part of this work was registered on the Open Science Framework https://osf.io/4cr32/.

1. Richter T, Nestler-Parr S, Babela R, Khan ZM, Tesoro T, Molsen E, et al. Rare disease terminology and definitions-a systematic global review: report of the ISPOR rare disease special interest group. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. (2015) 18:906–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.05.008

2. Angelis A, Tordrup D, Kanavos P. Socio-economic burden of rare diseases: a systematic review of cost of illness evidence. Health Policy Amst Neth. (2015) 119:964–79. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.12.016

3. WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability Health (ICF). WHO. World Health Organization. Available online at: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ (accessed September 2, 2020).

4. Dal Bello-Haas V, Florence JM. Therapeutic exercise for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2013) CD005229. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005229.pub3

5. Sman AD, Hackett D, Fiatarone Singh M, Fornusek C, Menezes MP, Burns J. Systematic review of exercise for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Peripher Nerv Syst JPNS. (2015) 20:347–62. doi: 10.1111/jns.12116

6. Collett J, Dawes H, Bateman J, Dawes H, Bateman J. Physical Activity for Long Term Neurological Conditions : Multiple Sclerosis and Huntington's Disease. Clinical Exercise Science. (2016). p. 155–77. Available online at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/ (accessed June 21, 2020).

7. Quinn L, Kegelmeyer D, Kloos A, Rao AK, Busse M, Fritz NE. Clinical recommendations to guide physical therapy practice for Huntington disease. Neurology. (2020) 94:217–28. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008887

8. Intiso D, Bartolo M, Santamato A, Di Rienzo F. The role of rehabilitation in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy: a narrative review. PM R. (2018) 10:636–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.12.011

9. WHO. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. WHO. Available online at: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_recommendations/en/index.html (accessed August 29, 2021).

10. Elsworth C, Winward C, Sackley C, Meek C, Freebody J, Esser P, et al. Supported community exercise in people with long-term neurological conditions: a phase II randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. (2011) 25:588–98. doi: 10.1177/0269215510392076

11. Wallace A, Pietrusz A, Dewar E, Dudziec M, Jones K, Hennis P, et al. Community exercise is feasible for neuromuscular diseases and can improve aerobic capacity. Neurology. (2019) 92:e1773–85. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007265

12. Simatos Arsenault N, Vincent P-O, Yu BHS, Bastien R, Sweeney A. Influence of exercise on patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome: a systematic review. Physiother Can. (2016) 68:367–76. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2015-58

13. Quinlivan R, Vissing J, Hilton-Jones D, Buckley J. Physical training for McArdle disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2011) CD007931. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007931.pub2

14. Heneghan C, Goldacre B, Mahtani KR. Why clinical trial outcomes fail to translate into benefits for patients. Trials. (2017) 18:122. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1870-2

15. Williamson P, Altman D, Blazeby J, Clarke M, Gargon E. Driving up the quality and relevance of research through the use of agreed core outcomes. J Health Serv Res Policy. (2012) 17:1–2. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2011.011131

16. Clarke M. Standardising outcomes for clinical trials and systematic reviews. Trials. (2007) 8:39. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-39

17. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. (2005) 113:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012

18. Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M, Horey D, OBoyle C. Evaluating maternity care: a core set of outcome measures. Birth Berkeley Calif. (2007) 34:164–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00145.x

19. Moore JL, Potter K, Blankshain K, Kaplan SL, O'Dwyer LC, Sullivan JE. A core set of outcome measures for adults with neurologic conditions undergoing rehabilitation: a clinical practice guideline. J Neurol Phys Ther. (2018) 42:174. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000229

20. Webster L, Groskreutz D, Grinbergs-Saull A, Howard R, O'Brien JT, Mountain G, et al. Development of a core outcome set for disease modification trials in mild to moderate dementia: a systematic review, patient and public consultation and consensus recommendations. Health Technol Assess. (2017) 21:1–192. doi: 10.3310/hta21260

21. Guideline for Selecting Instruments for a Core Outcome Set • COSMIN. COSMIN. Available online at: https://www.cosmin.nl/tools/guideline-selecting-proms-cos/ (accessed March 18, 2021).

22. COSMIN Taxonomy of Measurement Properties. Available online at: https://www.cosmin.nl/tools/cosmin-taxonomy-measurement-properties/ (accessed August 29, 2021).

23. Voet NBM, van der Kooi EL, Riphagen II, Lindeman E, van Engelen BGM, Geurts ACH. Strength training and aerobic exercise training for muscle disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2013) CD003907. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003907.pub4

24. Cup EHC, Sturkenboom IHWM, Pieterse AJ, Hendricks HT, van Engelen BGM, Oostendorp RAB, et al. The evidence for occupational therapy for adults with neuromuscular diseases: a systematic review. OTJR Occup Particip Health. (2008) 28:12–8. doi: 10.3928/15394492-20080101-02

25. Gianola S, Pecoraro V, Lambiase S, Gatti R, Banfi G, Moja L. Efficacy of muscle exercise in patients with muscular dystrophy: a systematic review showing a missed opportunity to improve outcomes. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e65414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065414

26. Narayanaswami P, Weiss M, Selcen D, David W, Raynor E, Carter G, et al. Evidence-based guideline summary: diagnosis and treatment of limb-girdle and distal dystrophies: report of the guideline development subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the practice issues review panel of the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Neurology. (2014) 83:1453–63. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000892

27. Habers GEA, Takken T. Safety and efficacy of exercise training in patients with an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy–a systematic review. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. (2011) 50:2113–24. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker292

28. Ydemann M, Eddelien HS, Lauritsen AØ. Treatment of critical illness polyneuropathy and/or myopathy - a systematic review. Dan Med J. (2012) 59:A4511. Available online at: https://ugeskriftet.dk/dmj/treatment-critical-illness-polyneuropathy-and-or-myopathy-systematic-review

29. Young P, De Jonghe P, Stögbauer F, Butterfass-Bahloul T. Treatment for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2008) CD006052. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006052.pub2

30. Corrado B, Ciardi G, Bargigli C. Rehabilitation management of the Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. Medicine. (2016) 95:e3278. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003278

31. Koopman FS, Beelen A, Gilhus NE, de Visser M, Nollet F. Treatment for postpolio syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) CD007818. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007818.pub3

32. Khan F, Amatya B. Rehabilitation interventions in patients with acute demyelinating inflammatory polyneuropathy: a systematic review. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. (2012) 48:507–22. Available online at: https://www.minervamedica.it/en/journals/europa-medicophysica/article.php?cod=R33Y2012N03A0507

33. Lui AJ, Byl NN. A systematic review of the effect of moderate intensity exercise on function and disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Phys Ther JNPT. (2009) 33:68–87. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e31819912d0

34. Eidenberger M, Nowotny S. Inspiratory muscle training in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review. NeuroRehabilitation. (2014) 35:349–61. doi: 10.3233/NRE-141148

35. Ferreira GD, Costa ACC, Plentz RDM, Coronel CC, Sbruzzi G. Respiratory training improved ventilatory function and respiratory muscle strength in patients with multiple sclerosis and lateral amyotrophic sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. (2016) 102:221–8. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2016.01.002

36. Arbesman M, Sheard K. Systematic review of the effectiveness of occupational therapy-related interventions for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Occup Ther. (2014) 68:20–6. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2014.008649

37. Ng L, Khan F, Mathers S. Multidisciplinary care for adults with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2009) CD007425. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007425.pub2

38. Quinn L, Busse M. Physiotherapy clinical guidelines for Huntington's disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag. (2012) 2:21–31. doi: 10.2217/nmt.11.86

39. Fritz NE, Rao AK, Kegelmeyer D, Kloos A, Busse M, Hartel L, et al. Physical therapy and exercise interventions in Huntington's disease: a mixed methods systematic review. J Huntingt Dis. (2017) 6:217–35. doi: 10.3233/JHD-170260

40. Trujillo-Martín MM, Serrano-Aguilar P, Monton-Alvarez F, Carrillo-Fumero R. Effectiveness and safety of treatments for degenerative ataxias: a systematic review. Mov Disord. (2009) 24:1111–24. doi: 10.1002/mds.22564

41. Fonteyn EMR, Keus SHJ, Verstappen CCP, Schöls L, de Groot IJM, van de Warrenburg BPC. The effectiveness of allied health care in patients with ataxia: a systematic review. J Neurol. (2014) 261:251–8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6910-6

42. Milne SC, Corben LA, Georgiou-Karistianis N, Delatycki MB, Yiu EM. Rehabilitation for individuals with genetic degenerative ataxia: a systematic review. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2017) 31:609–22. doi: 10.1177/1545968317712469

43. Marquer A, Barbieri G, Pérennou D. The assessment and treatment of postural disorders in cerebellar ataxia: a systematic review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. (2014) 57:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2014.01.002

44. Hajjar SH, Cooper JK. Progressive supranuclear palsy treatment—A systematic review. Basal Ganglia. (2016) 2:75–8. doi: 10.1016/j.baga.2016.01.004

45. Drory VE, Goltsman E, Reznik JG, Mosek A, Korczyn AD. The value of muscle exercise in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. (2001) 191:133–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00610-4

46. Bello-Haas VD, Florence JM, Kloos AD, Scheirbecker J, Lopate G, Hayes SM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of resistance exercise in individuals with ALS. Neurology. (2007) 68:2003–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000264418.92308.a4

47. Dalbello-Haas V, Florence JM, Krivickas LS. Therapeutic exercise for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2008) CD005229. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005229.pub2

48. Zinzi P, Salmaso D, De Grandis R, Graziani G, Maceroni S, Bentivoglio A, et al. Effects of an intensive rehabilitation programme on patients with Huntington's disease: a pilot study. Clin Rehabil. (2007) 21:603–13. doi: 10.1177/0269215507075495

49. Folz TJ, Sinaki M. A nouveau aid for posture training in degenerative disorders of the central nervous system. J. Musculoskeletal Pain. (1995) 3:59–70. doi: 10.1300/J094v03n04_07

50. Morley D, Dummett S, Kelly L, Jenkinson C. Measuring improvement in health-status with the Oxford Participation and Activities Questionnaire (Ox-PAQ). Patient Relat Outcome Meas. (2019) 10:153–6. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S198619

51. Morley D, Dummett S, Kelly L, Jenkinson C. Administering the routine activities domain of the Oxford participation and activities questionnaire as a stand-alone scale: the Oxford routine activities measure. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. (2018) 9:239–43. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S160263

52. Warner LM, Schüz B, Wolff JK, Parschau L, Wurm S, Schwarzer R. Sources of self-efficacy for physical activity. Health Psychol. (2014) 33:1298–308. doi: 10.1037/hea0000085

53. Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee I-M, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2011) 43:1334–59. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb

54. Quinn L, Morgan D. From disease to health: physical therapy health promotion practices for secondary prevention in adult and pediatric neurologic populations. J Neurol Phys Ther JNPT. (2017) 41:S46–54. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000166

55. Price A, Albarqouni L, Kirkpatrick J, Clarke M, Liew SM, Roberts N, et al. Patient and public involvement in the design of clinical trials: an overview of systematic reviews. J Eval Clin Pract. (2018) 24:240–53. doi: 10.1111/jep.12805

56. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Herron-Marx S, Hughes J, Tysall C, et al. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy. (2014) 17:637–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00795.x

57. Paul L, Coote S, Crosbie J, Dixon D, Hale L, Holloway E, et al. Core outcome measures for exercise studies in people with multiple sclerosis: recommendations from a multidisciplinary consensus meeting. Mult Scler Houndmills Basingstoke Engl. (2014) 20:1641–50. doi: 10.1177/1352458514526944

58. Mullen SP, Olson EA, Phillips SM, Szabo AN, Wójcicki TR, Mailey EL, et al. Measuring enjoyment of physical activity in older adults: invariance of the physical activity enjoyment scale (paces) across groups and time. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2011) 8:103. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-103

Keywords: physical activity, neuromuscular disease, motor neurone disease, Huntington's disease, inherited ataxias, hereditary spastic paraplegia, parkinsonism, outcome measurement instruments

Citation: Ramdharry G, Buscemi V, Boaz A, Dawes H, Jaki T, Jones F, Marsden J, Paul L, Playle R, Randell E, Robling M, Rochester L and Busse M (2021) Proposing a Core Outcome Set for Physical Activity and Exercise Interventions in People With Rare Neurological Conditions. Front. Rehabilit. Sci. 2:705474. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2021.705474

Received: 05 May 2021; Accepted: 23 September 2021;

Published: 21 October 2021.

Edited by:

Jennifer Ryan, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, IrelandReviewed by:

Paulo Henrique Silva Pelicioni, University of Otago, New ZealandCopyright © 2021 Ramdharry, Buscemi, Boaz, Dawes, Jaki, Jones, Marsden, Paul, Playle, Randell, Robling, Rochester and Busse. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Monica Busse, YnVzc2VtZUBjYXJkaWZmLmFjLnVr

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.