- 1Center for Advanced Study, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL, United States

- 2Institute of Physics II, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

We present mathematical models that also may be formulated as computer models for experiments that feature single photon resolution and multiple pairs of polarizers to determine the sorting into ordinary and extraordinary channels. The models are based on Einstein’s hypothesis of elements of physical reality that determine the photon properties and are at first developed for Malus-type experiments. It is then shown that analogous models apply to the well-known Clauser-Aspect-Zeilinger experiments and violate all Bell-type inequalities without violating Einstein’s separation principle. The Bell-type inequalities do not apply to the actual experiments, because they cannot obey the physically necessary symmetry with respect to polarizer-pair rotations. We believe that these findings suggest a change of current interpretations of quantum entanglement away from instantaneous influences at a distance, as promoted in the physics Nobel-lectures 2022, and back toward Einstein’s ideas as well as the more recent ideas of Gerard ‘t Hooft.

1 Introduction

The well-known debate between Einstein and Bohr can be summarized by the slogan “relativity versus probability”. Bohr maintained that, with respect to quanta, probability was a fundamental feature of nature and Pauli explained that in contrast to Bohr “… Einstein … considered quantum mechanics to be something like statistical gas theory … ” Einstein resisted indeed the Born-type probability theories that are defined without the involvement of elements of physical reality. At first glance, the differences of the two views appear minor. Probability theorists assume that Tyche, the goddess of fortune choses elements

It took Einstein years to produce an incisive response to Bohr and the teachings of the Copenhagen school. With Podolsky and Rosen he formulated a manuscript (now called the EPR paper (Einstein et al., 1935)) that offered a possibility to determine complementary properties of the quanta as follows: create pairs of quanta that are correlated by physical law. Then, if you measure the velocity of one piece of the pair you may deduce the velocity of the other from the physical law. Measuring the position of the other piece gives you, therefore, both properties. The Uncertainty Principle is not violated, because only one measurement is performed on each quantum, to obtain both complementary properties. We may, thus, believe that Tyche’s choices also represent elements of physical reality.

The actually performed first direct experiments related to EPR were a variation of a suggestion of Bohm: Kocher and Commins (Kocher and Commins, 1967) used measurements involving photon pairs and the concept of polarization. Judging from their results, Einstein’s ideas appeared to be possible. Kocher and Commins found excellent experimental correlations (entanglement) for equal polarizer angles that could be seen as representing a law of nature for the photon-pairs and the corresponding existence of properties.

However, the well-known inequality of J. S. Bell (Bell, 1964) has led to a different explanation of the photon-pair experiments. Note that Bell’s original theory was describing spin

The crucial question is why Bell’s model does not agree with quantum theory. Bell had an answer to this question. He was convinced that he, CHSH and others had derived the inequalities more or less exclusively based on Einstein’s physics and in particular Einstein’s separation principle and corresponding “local” properties of physical events (following from the limitations of all velocities to a maximum of the speed of light in vacuum). The violation of their inequalities indicated to Bell and CHSH that a special interpretation of the photon correlation (entanglement) that included “non-local” effects must be in order. As we will show, it is important to distinguish between different forms of “non-localities”, in order to understand what indeed the Bell-CHSH inequalities mean. The form that Einstein objected to was any instantaneous influences at a distance, such as a measurement in Tokyo influencing instantly the outcome of a measurement in New York. In contrast to this particular non-locality that Einstein called “spooky”, there are physically natural (at least to Einstein) non-localities. For example, any properly relativistic model requires the theoretician’s consideration of physical events relative to each other and involves, if these events are spatially separated, non-local theoretical considerations to start with. Such a non-locality may, however, retrospectively be explained without instantaneous influences by use of a space-time system. It is important to distinguish between the permitted global thinking of a theoretician using a space-time system and inappropriate introductions of instantaneous non-local occurrences. These subtle problems related to the physical nature of non-localities are enhanced by the mathematical complications of set theoretic probability that must be the basis of the derivation of the Bell-CHSH inequalities.

We highlight these problems and questions by detailed mathematical- and computer-models for two types of experiments: the Malus-type as explained in the Feynman lectures (Feynman Lectures, 1965) and the EPRB-type, including the experiments of Kocher and Commins (Kocher and Commins, 1967), of Aspect and coworkers (Aspect, 2015) and of Kwiat (Kwiat et al., 1999) and coworkers. Before doing so, however, we discuss what we mean by words like “local” or “measurement” etc. and how to avoid prejudicial conclusions about them.

2 Definitions and prejudices in discussions related to the Bell-CHSH inequalities

Concepts often involved when discussing Bell-CHSH, are those of entanglement, measurement, experiment, local vs. non-local, as well as deterministic vs. probabilistic. We also use these terms but only subject to the following considerations:

It is commonly claimed and believed that the Bell-CHSH inequalities must be valid within Einstein’s framework and definitions of physical principles. We put our main emphasis on the refutation of this important point and, therefore, do not involve concepts of quantum mechanics other than those pioneered by Einstein.

As a consequence, we never use any contemporary quantum mechanical meaning of the word “measurement”. What we mean by measurement follows from the most elementary explanations such as “a detector clicks”, or in another situation “a detector clicks after a photon has passed a polarizer”. We agree with the standard definition found on Internet-dictionaries: “Measurement is the quantification of attributes for an object or event, which can be used to compare with other objects and events.” It nicely encompasses the importance of the relative comparison of attributes and events. With the expression “experiment” we also refer to the dictionary meaning of “a scientific procedure undertaken to make a discovery, test a hypothesis, or demonstrate a known fact”.

When we talk about entanglement, we do mean something related to the quantum-entanglement as defined already by Schrödinger. In our present utilization of the word, we only refer to some basic correlation and hope that a future more detailed interpretation will benefit from our contributions to an understanding of the work of Bell-CHSH.

The concepts of “local” and “deterministic” appear in a vast Bell-CHSH-related literature, often with different meaning. We believe that what is acceptable as “local theory” spans a wide range that is not necessarily accepted by the followers of Bell-CHSH. For example, Einstein’s relativity teaches about measurement outcomes relative to each other. If these outcomes have a space-like distance, then naturally any relativistic thought-process of a theoretician involves non-local factors, as already mentioned. Yet, there are not many physicists who would think of such relativistic thinking as something that is physically undesirable or even forbidden. We, therefore, have limited ourselves to talk about “local” and “non-local” only in connection with specific experiments and measurements that we model also by computers to illustrate the non-local thought processes versus the local causal machinery that mother nature uses (according to Einstein) in a given measurement station.

We dismiss out of hand all definitions of “local” and “deterministic” that use certain conditional probabilities: Bell and followers have frequently used probabilities conditional to one particular element of physical reality (Gisin, 2012). Because the elements of physical reality may involve continua (distances, times, etc.), the Lebesgue measure of the probability that such a particular element of physical reality is actually encountered may be zero. Consequently, such a conditional probability cannot sensibly be defined within the confines of set theory (for additional explanations and problems see (Hess, 2023)).

Regarding the concepts of “deterministic vs. probabilistic”, we also adhere to the common-sense definition that: “Deterministic models produce the same exact outcome for any given exact same set of inputs, while probabilistic models do not.” However, we have to be cautious with this definition in the following respect. Bell’s model contains the symbols of Einstein’s elements of physical reality that may be randomly selected out of a continuum and may be modeled, as we will do below, by random real numbers out of the interval [-1, +1]. The subtle point is now that one may not be permitted to use the same real number again for different model-events. While it may be true then that we have the same exact outcome for the same exact input, the probability to encounter the same exact input may be zero. Such a model is, therefore, comparable to models of radioactive decay and must be seen as probabilistic. The consequences of this fact for the interpretation of experiments related to Bell-CHSH were discussed in (Jakumeit and Hess, 2024). Bell’s model is, therefore, probabilistic depending on the nature of his variable

We like furthermore to point to the fallacies of the very common Alice and Bob reasoning regarding locality considerations. Alice controls one polarizer angle without knowing anything about Bob, who controls the other polarizer angle. The confusion of the Alice-Bob stories arises from the fact that Alice and Bob are seen as somehow representing mother nature, who must, according to Einstein’s views, indeed be local causal. That does not mean however that a theoretician, say Charly, does not know global macroscopic instrument arrangements and designs the local causation of his model by using his global knowledge and the space-time system. For the particular case of EPRB experiments, Charly must know about the ancient principle that events may only be evaluated relative to each other, which Alice and Bob cannot accomplish to start with, because they do not know about each other. Without global physical laws and a space-time system, even the correlation of clocks in distant cities becomes a mystery.

We ask the reader not to abandon our reasoning, because of prejudices regarding the use and meaning of the discussed important terms.

We also like to point toward other important criticisms involving views more or less different to ours presented here. In particular, the concept of “contextuality” has been used in a number of ways to discuss violations of the Bell-CHSH inequalities. We do not use the loaded word “contextual” at all but only talk about “events being evaluated relative to each other”. Of course, in the case of spatially distant experiments relative evaluation encompasses a lot of the meaning of “contextuality”. Numerous important works have discussed related violations of Bell-CHSH. Particularly relevant points have been presented in the works of Khrennikov (2009) (see also the well-known Växjö conferences) and Kupczynski (2020) as well as references in their works.

3 Malus-type experiments for single photons with sequential polarizers

3.1 Geometry and measurement-outcomes of the Malus-type experiments

Perhaps the most illuminating experiment, at least with respect to modeling and the Alice-Bob “locality” assumptions by Bell and followers, is the standard Malus-type experiment performed with single photon resolution. Consider two special polarizers, Wollaston prisms, in sequence to the right of a single-photon source

Assume now that the source

Sequential measurements with two additional Wollaston prisms

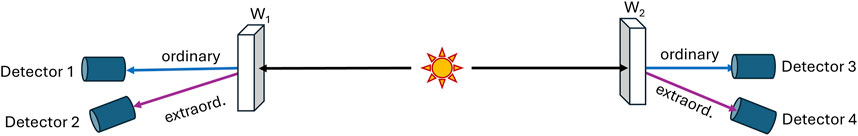

Figure 1. Experimental arrangement for single-photon Malus-type experiments. The polarizer is represented by Wollaston prism

The two sets

Einstein’s hypothesis is that the photons of these sets have certain properties. We denote these properties of the photons that are contained in the various sets above by the lower-case symbols:

Of all the photons that transfer into the ordinary channel of

photons will transfer into the ordinary channel of

The connection of the corresponding expressions in terms of the energy of macroscopic electromagnetic fields (instead of large numbers of photons), has been described in detail in introductory texts and also has been shown to be fully consistent with the laws of quantum mechanics (Feynman Lectures, 1965; Baym, 1973).

In order to provide an Einstein type model for the single photon Malus law we need to develop a model that is in principle described by a set theoretic probability theory that features events

3.2 Set theoretic mathematical model for the Malus-type experiments

It has been shown in great detail by David Williams in his textbook on probability theory (Williams, 2001) that experiments describing the possible machineries of our surrounding macroscopic world by using probabilities may be modeled by the set theoretically precise Fundamental Model of Probability Theory. The patient reader must remember that set-theoretic mathematics deals with a “fundamental triple” that includes a sample space

The Fundamental Model of probability theory uses the interval

To simulate the actual polarizer experiments by involving real numbers for the photon properties, it is convenient (as we will see below) to generalize the Fundamental model to include the extended interval

The sorting of the analyzers

According to the Fundamental Model, the probability measure that we indeed encounter such

Notice that the use of the relative polarizer angles

4 Polarizers on opposite sides of a source

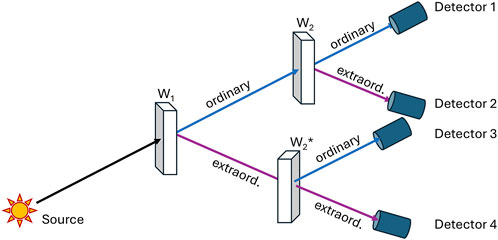

We now turn to the configuration with the polarizers on opposite sides of the source as illustrated in Figure 2, which shows the experimental arrangement along the lines of the EPR ideas with the modifications by Bohm and first implementation using photon-pairs and a stretched film of poly-vinyl alcohol containing oriented anisotropic molecules instead of a Wollaston prism, by Kocher and Commins (Kocher and Commins, 1967).

Unlike the Malus-type single-photon experiment, this experiment has been performed by many researchers starting with Kocher and Commins and continuing with significant extensions by groups around Clauser et al. (1969), Aspect (2015), Giustina et al. (2015), Kwiat et al. (1999) and others.

We use the same notation that we have used in the previous section, in order to highlight the important similarities and differences with respect to the modeling of the Malus-type. Wollaston

The source emanates now correlated photon-pairs (see explanations by Kocher and Commins (1967)). We assume in the following theoretical discussions that the correlation of the photon-pair is ideal and such that each photon is being recognized according to its properties in identical fashion by

As for the case of the Malus-type experiments, we need to maintain the principle that the measurements of events have only physical meaning relative to each other. Alice and Bob, knowing nothing about each other, may only judge their local measurements relative to their own previous measurements and thus conclude that the clicks of their detectors are random, corresponding to the detections for ordinary and extraordinary channels of

Therefore, if we wish to proceed to the understanding of the non-local distant correlations, we need to clearly distinguish on one hand between the theoretical knowledge that Charly must have about the global situation and on the other hand the local causality that must apply according to Einstein for the events in the respective stations.

The natural local interactions involve the polarizer angles

Note, that the experimenters must, as Charly does, involve more than their local knowledge of equipment configurations if they wish to consider relative outcomes. They too must have a global coordinate system and synchronized clocks (a space-time system), whenever they attempt to compare the outcomes

What is it then that can be measured, while the global rules of relative evaluation as well as the rules of local causes are strictly obeyed? Consider the case of registered detector clicks

We now apply the methods that we have developed for the Malus-type experiment in the previous section:

There exists one big difference of the EPRB-type experiments to the Malus-type. For these latter, we could use

We still use Einstein’s elements of physical reality that may be imagined as “markers” of the single photons that are the causes for

In our opinion, this approach synthesizes the views of Einstein and Bohr. The properties of the photons and photon pairs are only known after at least one measurement (with say

We turn now to our model in which all of Einstein’s elements of physical reality are simulated by real numbers out of [-1, +1]. Each of the randomly selected numbers signifies different properties and is denoted by

Based on all these facts, Charly lets:

and

in order to model the law of nature that determines the equal and not-equal relative outcomes

We do admit that our multiple assumptions, although very plausible, do not let us prove with certainty that quantum-non-localities are not involved in any way. Such proof can probably never be achieved. One simply cannot prove that “spooky” influences (in Einstein’s sense) do not exist.

There is just one minor modification necessary in order to fully compare this model with the experiments of Kocher, Clauser, Aspect and others. All these well-known actual experiments use complete anti-correlation instead of correlation. To obtain the results for anti-correlation, we just need to put

If and only if:

Equations 2a-c permit us to derive the well-known measured averages by our model. For any given polarizer-angle pair

In the limit of

This latter result agrees with the results of quantum mechanics, which appears entirely natural, because it represents in essence a Malus-type law and is very closely connected to the measurement-outcomes for single photon Malus type experiments.

This very result is, however, incompatible with the Bell-CHSH inequalities derived in (Clauser et al., 1969). How can that be? The obvious reason is that Bell-CHSH and followers have used the same measurement number

5 Bell-type inequalities as derived in the terms of the Fundamental Model

Bell-CHSH deduced by elementary manipulations that one expects:

Key to this finding is that they used identical

Notice that identical

which are now each cyclically connected (with three products known, the fourth is fully determined) and, therefore, all quadruples are equal to

As mentioned, Bell-CHSH have deduced their use of the identical

The astounding conundrum of the Bell-CHSH inequalities arose from the conviction of Bell and followers that their derivations followed mostly from Einstein’s separation principle. They did not realize that their derivation required additional mathematical conditions regarding the cardinality of Einstein’s elements of physical reality and a certain cyclicity of the polarizer angles. They also did not realize that these mathematical conditions have the consequence that the inequalities are physically not acceptable, because they are not invariant under rotations of the polarizer angle-pair around the z-axis. We show these facts in form of two theorems in the following section. We formulate these theorems in terms of the Fundamental Model that we have used all along. It is important to note that the theorems are derived without a direct use of Einstein’s separation principle (although it is indirectly guaranteed by the random draws of real numbers). All the above facts and following Theorems are also consistent with Gerard ‘t Hooft’s widely published ideas ('t Hooft, 2020) regarding the Einstein-Bohr debate and his recent additional important findings with regard to “hidden ontological variables” ('t Hooft, 2024).

6 Physical inconsistency of mathematically correct Bell-CHSH inequality: two theorems

6.1 Theorem 1

Given the polarizer geometry of Section 4, a cyclical arrangement of the polarizer angle pairs such as (

The Bell-CHSH-type inequalities may be validated if and only if the cardinality of the number of draws

6.2 Proof

6.2.1 Necessity

If Einstein’s elements are not countable and modeled by numbers selected randomly and uniformly from the interval [-1, +1] of the reals, all the chosen numbers are different with probability 1. We may, therefore, choose function-values

6.2.2 Sufficiency

Given are the cyclical arrangement of polarizer angles from above and an arbitrary finite number

The facts of this theorem with regard to the cardinality of Einstein’s elements vs. the number of draws were unknown to Bell and followers. They believed that it was rather “locality” that was the virtually sole non-trivial basis for their inequalities, while, in fact, it is only locality together with cardinality. The locality requirement that, at the source, Einstein’s elements are independent of the polarizer angles, is automatically fulfilled by the randomness of the draws. Note that our proof above has not assumed any probability measure for the possible function-outcomes of

Some may wish to indeed accept a finite number of Einstein’s elements as a physical fact and, thus, have the physical validity of the Bell-CHSH inequalities guaranteed. There is, however, another important factor to be considered. The results of quantum mechanics for the data averages of the above experiments (Equation 3) are invariant under rotations of the polarizer-pairs around the z-axis and this invariance has also been proven experimentally for the photon-pair experiments beyond reasonable doubt [see 2, 4, 6, 7, 15]. Consequently, the sum of three (Bell) or four (CHSH) such data averages of experimental runs should be invariant with respect to rotations of the polarizer pairs around the z-axis for one or more such experimental runs. However, we prove in Theorem two below that for a finite number

6.3 Theorem 2

Given the premises of Theorem 1 and a finite number

The Bell-CHSH inequalities are not invariant to rotations of the polarizer pairs around the z-axis.

6.4 Proof

Take the four polarizer angles used by CHSH. Then, the Bell-CHSH inequalities are valid according to Theorem 1.

Now rotate the two polarizers for each of the separate experimental runs with polarizer angle pairs (

The Bell-CHSH inequality is, therefore, not invariant with respect to rotations of the polarizer angles around the z-axis and violates, thus, both the results of quantum mechanics and of actual measurements. We emphasize again that we have not made the specific model assumptions of Equations 2a–c to derive the theorems. Theorem two does not tell us, for this reason, how large the violations of the Bell-CHSH inequalities are. The numerical experiment discussed in the next section shows that with the additional assumptions of our model, the violation is major and approximates the quantum results.

The above theorems leave us then with a very reasonable and physically acceptable corollary: the Bell-CHSH inequalities do simply not apply to the Clauser-Aspect-Zeilinger experiments. Furthermore, if we are willing to accept that Einstein’s elements of physical reality have the cardinality of a continuum, we can find a model that violates Bell-CHSH and is rotationally invariant. This model may also be implemented on two distant computers.

7 Two-computer model for EPRB experiments and application to actual experiments

We present now a numerical EPRB experiment, executed by two computers

Overall, we use precisely the same model that we have developed above and Equations 2a–c with two exceptions: We use a computer random number instead of a mathematical real number for

And we guess the law of nature that

if and only if

Remember that the subscript

The computer-model outcomes compare well with the results of quantum mechanics. Of course, we have included a fair number of definitions and theoretical assumptions and have used global space and time coordinates as well as rotational invariance, in order to develop this “theory laden” computer experiment.

Notice that any fast changes of

The necessary special and relative treatment of the

As a corollary, the Bell-CHSH inequalities should have never been considered as a staple of physical theory related to EPRB, because they violate rotational invariance that is a hallmark of quantum theory and the Malus law, and has been experimentally proven by countless single photon EPRB-type measurements.

7.1 Computer simulations illustrating Theorem 2

The just described computer model can be used in a straightforward way to simulate the results that are expected for a countable number of elements of physical reality. We just select randomly a set of

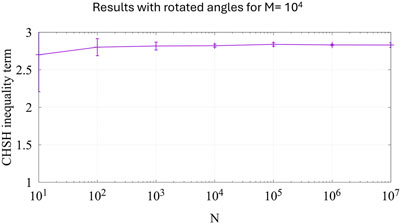

We have performed this calculation for the polarizer angles used by CHSH (Clauser et al., 1969) and Aspect (Aspect, 2015) for the given

Figure 3. Model results for the values of CHSH (defined by Equation 4) plotted versus the number of measurements

We then have rotated the four polarizer-angle-pairs in such a way around the z-axis that the angle

Figure 4. The CHSH values for a system of coordinates rotated such that we have

As clearly seen in Figure 4, the rotation of the polarizer angle-pairs has completely destroyed the validity of the CHSH inequality. Therefore, the CHSH inequality is not invariant to rotations of the polarizer angle-pairs and the coordinate system as is required by the results of quantum mechanics and by a world of experimental evidence including the classical limit for very large numbers of photons.

8 Conclusion

We have used the Fundamental Model of probability theory (Williams, 2001) for experiments using single photons or photon-pairs and polarizers in two very different configurations, one corresponding to Malus-type measurements, the other to EPRB-type measurements such as performed by Kocher and Commins (1967) and groups related to Aspect (2015), Clauser et al. (1969) and Kwiat et al. (1999); Giustina et al., 2015).

Our model shows a pronounced violation of the Bell-CHSH inequalities and agreement with the quantum result. We have shown that this unexpected violation of the highly respected inequalities arises, within the confines of the Fundamental Model (Williams, 2001), from the fact that there are precise premises that guarantee the mathematical validity of the inequalities. However, these mathematical premises lead to a mathematical-physical problem: The correctly derived Bell-CHSH inequalities are physically not acceptable, because they are not invariant to rotations of the polarizer-angle pairs. This lack of invariance makes Bell-CHSH physically unacceptable as a model for the actual experiments such as (Kocher and Commins, 1967; Clauser et al., 1969; Aspect, 2015; Kwiat et al., 1999; Giustina et al., 2015), which are invariant to such rotations. The paradox created by the work of Bell is, thus, resolved and proven to be no reason to suspect any failure of Einstein’s separation principle as well as the ideas of Einstein and ‘t Hooft ('t Hooft, 2020; 't Hooft, 2024) regarding the existence of ontological hidden variables and their local-causal nature.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

KH: Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing, Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Visualization. JK: Writing–review and editing, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Recent correspondence with Anthony J. Leggett has been a very valuable motivation for us to derive Theorems 1 and 2. While we agree on the importance of the cardinality, the Theorems may explain at least some of the differences of our views mentioned in (Leggett, 2024). Comments of Colin Naturman regarding finite subsets and subtleties for a countable-infinite number of elements of physical reality were helpful for our formulation of the Theorems. We also thank the referees for their important contributions to the clarity of the explanations.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aspect, A. (2015). Closing the door on Einstein and bohr’s quantum debate. Physics 8, 123. doi:10.1103/physics.8.123

Baym, G. (1973). Lectures on quantum mechanics. Redwood City: Adison-Wesley Publishing Company Inc., 1–8.

Bell, J. S. (1964). On the Einstein podolsky rosen paradox. Physics 1, 195–200. doi:10.1103/physicsphysiquefizika.1.195

Clauser, J. F., Horne, M. A., Shimony, A., and Holt, R. A. (1969). Proposed experiment to test local hidden-variable theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 23, 880–884. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.23.880

Einstein, A., Podolsky, B., and Rosen, N. (1935). Can quantum mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? Phys. Rev. 16, 777–780. doi:10.1103/physrev.47.777

Gisin, N. (2012). Non-realism: deep thought or a soft option? Found. Phys. 42, 80–85. doi:10.1007/s10701-010-9508-1

Giustina, M., Versteegh, M. A., Wengerowsky, S., Handsteiner, J., Hochrainer, A., Phelan, K., et al. (2015). Significant-loophole-free test of bell's theorem with entangled photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 250401–250407. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.115.250401

Hess, K. (2023). Logical conflict between Bell’s locality and probability theory. J. Mod. Phys. 14, 1762–1770. doi:10.4236/jmp.2023.1413105

't Hooft, G. (2024). The hidden ontological variable in quantum harmonic oscillators. Front. Quantum Sci. Technol. 3, 1505593.

Jakumeit, J., and Hess, K. (2024). Breaking a combinatorial symmetry resolves the paradox of einstein-podolsky-rosen and Bell. Symmetry 16, 255–265. doi:10.3390/sym16030255

Khrennikov, A. (2009). “Contextual approach to quantum formalism,” in Fundamental theories of physics. Springer Nature.

Kocher, C. A., and Commins, E. D. (1967). Polarization correlation of photons emitted in an atomic cascade. Phys. Rev. Lett. 18, 575–577. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.18.575

Kupczynski, M. (2020). Is the moon there if nobody looks: Bell inequalities and physical reality. Front. Phys. 8, 1–13. doi:10.3389/fphy.2020.00273

Kwiat, P. G., Waks, E., White, E. G., Appelbaum, I., and Eberhard, P. H. (1999). Ultrabright source of polarization-entangled photons. Phys. Rev. A 60, 773–776. doi:10.1103/physreva.60.r773

Leggett, A. J. (2024). The EPR-bell experiments: the role of counterfactuality and probability in the context of actually conducted experiments. Philosophies 9.5, 133. doi:10.3390/philosophies9050133

't Hooft, G. (2020). Deterministic quantum mechanics: the mathematical equations. Front. Phys. 8. doi:10.3389/fphy.2020.00253

Vorob’ev, N. N. (1962). Consistent families of measures and their extension. Theory Probab. Its Appl. 7, 147–163.

Keywords: Bell-inequalities, CHSH-inequalities, quantum-entanglement, EPR-experiments, Monte-Carlo simulation

Citation: Hess K and Jakumeit J (2025) Explicit mathematical models of multiple polarization-measurements and the Einstein-Bohr debate. Front. Quantum Sci. Technol. 4:1542466. doi: 10.3389/frqst.2025.1542466

Received: 09 December 2024; Accepted: 19 March 2025;

Published: 27 March 2025.

Edited by:

Luca Lepori, QSTAR, ItalyReviewed by:

Andrei Khrennikov, Linnaeus University, SwedenGerard 't Hooft, Utrecht University, Netherlands

Bengt Norden, Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden

Copyright © 2025 Hess and Jakumeit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jürgen Jakumeit, amFrdW1laXRAdW5pLWtvZWxuLmRl

Karl Hess

Karl Hess Jürgen Jakumeit

Jürgen Jakumeit