- 1Institute of Sport Science, College of Physical Education, Southwest University, Chongqing, China

- 2Department of Police Tactics, Chongqing Police College, Chongqing, China

- 3School of Physical Education, Sichuan Agricultural University, Ya'an, China

- 4School of Physical Education, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi'an, China

- 5Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health, Orebro University, Orebro, Sweden

- 6Unit of Integrative Epidemiology, Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

- 7International College, Krirk University, Bangkok, Thailand

This review examines the existing literature regarding the utilization of combat sports in virtual reality (VR) for disease rehabilitation and adaptive physical activity. A total of 18 studies were obtained from the Web of Science and Scopus databases. The results suggest that Boxing, the most studied combat sport in VR systems, has been primarily used to improve motor function and quality of life in patients with neurological conditions such as cerebral palsy, Parkinson’s disease, and stroke. Furthermore, VR combat sports have been shown to increase energy expenditure and physical activity intensity in individuals with disabilities, proving effective in maintaining overall physical health. Notably, VR boxing produces higher energy expenditure than other activities (e.g., tennis), with heart rate (HR) and oxygen consumption (VO2) during boxing sessions consistently exceeding those observed in tennis. Overall, research in this field remains limited and further explorations are warranted.

1 Introduction

Virtual Reality (VR) is a technology that uses computer simulations to create artificial realities, offering users a virtual environment that closely resembles the real world. Through devices like head-mounted displays (HMDs) (1) or 3D glasses, VR presents three-dimensional images to users, creating an immersive experience that allows real-time interaction with the virtual environment (2). Due to its affordability and lack of special requirements for use, VR has quickly gained popularity in fields such as education (3), sports (4), and entertainment (5), with increasing interest in its potential applications in rehabilitation and adaptive sports for individuals with disabilities.

Neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders, including Parkinson’s disease (PD), cerebral palsy (CP), and stroke, represent significant global health challenges due to their profound impact on motor function and quality of life. PD leads to motor impairments such as tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability, which severely hinder daily activities (6). CP results in abnormalities in muscle tone, movement, and motor skills, often leading to secondary complications such as hip pain, balance issues, and hand function impairment (7, 8). Stroke, a leading cause of adult disability, causes muscle weakness, spasticity, and cognitive deficits (9). For individuals affected by these conditions, even simple physical tasks, such as climbing stairs, can become considerable obstacles. These motor dysfunctions result in profound functional limitations and a marked decrease in life satisfaction (10, 11). As such, effective interventions for these disorders have garnered increasing attention.

In this regard, virtual reality (VR) has been utilized as a promising therapeutic approach to address these conditions, with exciting results in improving rehabilitation outcomes (12, 13). VR not only helps individuals with these disorders engage in tailored motor training but also offers a more engaging, interactive, and accessible form of rehabilitation. In addition, VR has demonstrated its effectiveness in reducing pain for injured athletes and enhancing their performance (14), while also providing cognitive skill training without the need for physical strain (15). Individuals with disabilities can also benefit from VR, such as experiencing effective training and rehabilitation without the limitations imposed by conventional therapies (16). Moreover, commercial VR game systems are gaining popularity in adaptive physical activity, with systems like Nintendo Wii Sports and Wii Fit offering immersive experiences that combine physical activity with engaging gameplay (17). These systems not only promote energy expenditure and physical activity but also contribute to maintaining overall health (18–20). Additionally, VR has been shown to provide high levels of enjoyment (21–23), potentially resulting in greater adherence to exercise routines (24).

Combat sports include many types, such as boxing, karate, taekwondo, wrestling, martial arts, judo, Muay Thai, and kickboxing. Combat sports are highly open and interactive activities, unconstrained by fixed routines or techniques, requiring athletes to continually adapt to new situations and respond quickly (25). Therefore, when integrating combat sports or related elements with electronic technologies or products, special attention must be given to their open and interactive nature. In this context, VR may be particularly well-suited for combining with combat sports or their elements, as VR is a technology that emphasizes proactivity and interactivity. Compared to other electronic media, VR increases users’ freedom of movement, allowing operators or players to fully immerse themselves and interact more conveniently and flexibly with others (such as real or virtual people) and their environment (such as virtual targets). These characteristics greatly enhance the enjoyment of such activities and may further increase participants’ physical activity levels, which can be particularly beneficial for those who need physical exercise to maintain basic health or recover from injury. Additionally, VR may overcome some of the limitations associated with the openness and interactivity of combat sports. Specifically, your training partner or opponent does not need to be physically present or even a real person. This is particularly useful for individuals in special settings, such as hospitals or rehabilitation centers.

To date, no study has specifically addressed the integration of combat sports with VR technology in academic efforts. Therefore, this mini-review is presented to explore the existing evidence regarding the effectiveness of incorporating combat sports into VR technology for disease treatment and adaptive sports among individuals with disabilities. By evaluating these studies, this paper seeks to provide insights and recommendations for future developments in this field.

2 Methods

We used keyword searches in WOS and Scopus (covering titles, abstracts, and keywords). Our search query was: Topic = “virtual reality” or “VR” AND Topic = “Boxing” OR “boxer” OR “combat sport*” OR “karate” OR “taekwondo” OR “wrestling” OR “fencing” OR “martial art*” OR “judo” OR “jiu jitsu” OR “wushu” OR “kung fu” OR “Muay Thai” OR “Krav Maga” OR “Sambo” OR “Aikido” OR “kickbox*”.

This search query was derived from a previous review on VR (26) and previous reviews on combat sports (27). We searched the databases from their inception to April 21, 2024. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Unavailable full text; (2) Grey literature: For example, excluding conference papers, abstracts, theses, etc.; (3) Information unrelated to disease recovery or adaptive sports.

3 Results

We included 101 papers from WOS and 114 papers from Scopus. After removing 150 irrelevant and 47 duplicate documents, 18 papers were analyzed.

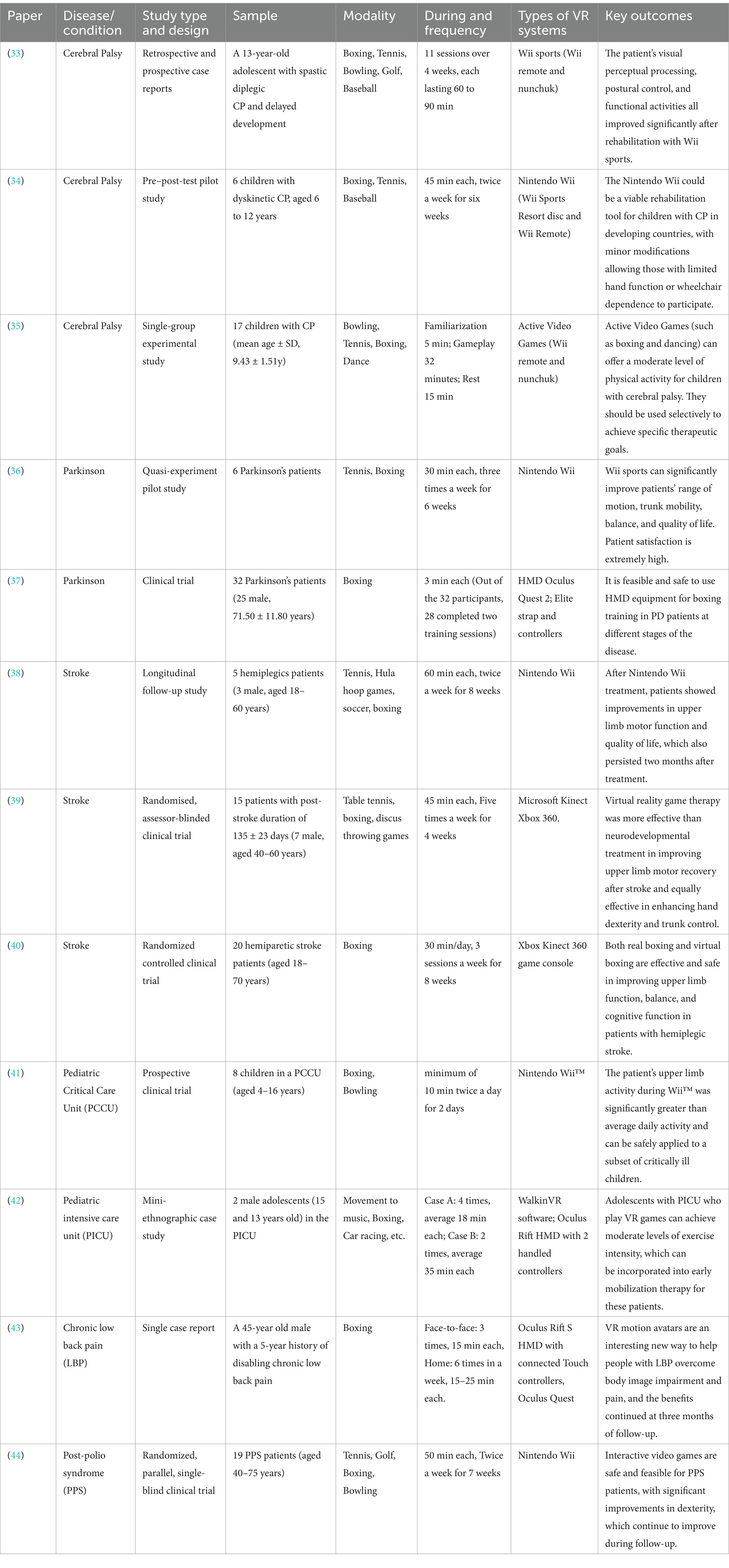

3.1 Potential of VR-based combat sports in rehabilitation and therapy

Virtual reality technology holds promise as a tool for therapy and improving rehabilitation outcomes (28–30). Often utilized in the form of virtual reality games, this technology aims to achieve its objectives by allowing patients to interact with various sensory environments. Nintendo Wii Sports is one of the most popular systems (31, 32). Wii games include activities such as tennis, baseball, boxing, and golf, providing patients with a variety of options. Based on the collected literature, boxing is the most common combat sport in this gaming system, primarily used for the treatment of individuals with cerebral palsy (CP), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and stroke.

Regarding cerebral palsy rehabilitation, the first published case report on using Wii for rehabilitation (33) documented the case of a 13-year-old CP patient who underwent 11 sessions of Wii Sports games, including boxing, lasting 60–90 min each (see Table 1). All games promoted trunk control, as boxing, for instance, requires trunk midline orientation and endurance of trunk muscles. Results showed positive outcomes in visual perception processing, postural control, and functional activities in CP patients using this gaming technology. Two studies explored the potential of using low-cost gaming systems as a therapeutic modality for CP patients, indicating the need for further research to ascertain its value (34, 35).

In Parkinson’s disease rehabilitation, an experimental study involving six PD patients underwent 18 interventions, including boxing and tennis (Wii Sports), yielding satisfactory results. Nintendo Wii enhanced the range of motion, trunk activity, and balance in PD patients, thereby improving their quality of life (36). Another study investigated the feasibility of using commercial wearable head-mounted displays (HMDs) and selected immersive virtual reality (IVR) sports games (boxing exercise mode) for PD patients. Consistent with previous research, users highly rated IVR as a therapeutic tool and expressed willingness to recommend it to others. Moreover, the safety of wearable devices was further confirmed (37).

Regarding stroke rehabilitation, researchers noted that two months after intervention, Nintendo Wii continued to have a sustained positive impact on sensory-motor recovery and quality of life in stroke patients (38). Both neurodevelopmental treatment and virtual reality games can improve hand flexibility and trunk control in stroke patients, but virtual reality games play a greater role in enhancing upper limb movement recovery (39). Ersoy and Iyigun (40) compared virtual reality boxing training with real-world boxing training and found both to be effective in improving upper limb function, balance, and cognitive function in stroke patients, with no significant differences between them.

In addition to these three major conditions, VR gaming systems also play a role in the rehabilitation of other conditions. Specifically, Abdulsatar et al. (41) and Lai et al. (42) explored the feasibility of engaging critically ill children in physical activities in pediatric intensive care units, indicating that VR exercise can be safely implemented for some critically ill patients. During VR game activities (such as boxing), upper limb movement was significantly higher than the average daily activity level (p = 0.049). Additionally, gameplay appeared to enhance participants’ mood and alertness, and motivated them to engage more actively in early mobilization therapy. An intriguing study proposed a novel approach to treating chronic low back pain by embodying movement in VR (as a boxer), helping chronic low back pain patients make positive progress in body image (perceived strength, vulnerability, agility, and movement confidence) and pain (43). Finally, a total of 39 patients with Post-Polio Syndrome were randomly assigned to either the VR interactive game group (including boxing games) (n = 19) or the active exercise group (n = 20). Participants engaged in training twice a week (50 min per session) for a duration of seven weeks. Both groups showed improvements in motor function, functionality, balance, pain, and fatigue after the intervention; however, the VR game group demonstrated superior performance (44).

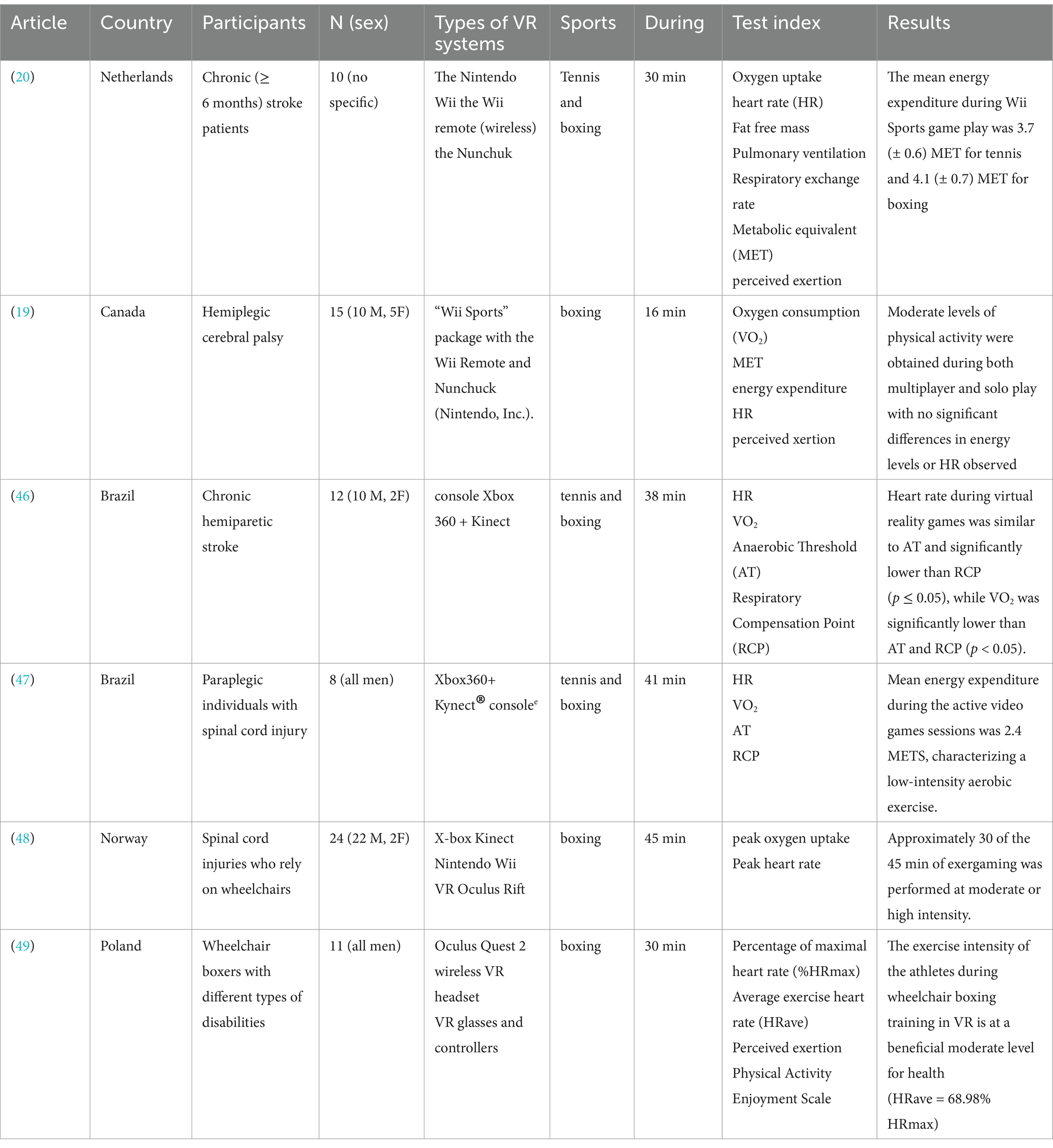

3.2 Role of VR-based combat sports in adaptive physical activities

VR plays essential roles in adaptive physical activities (16, 45). For individuals with disabilities, participating in regular sports activities may be unattainable, and a lack of activity could further deteriorate their health condition. Therefore, the advantages of virtual reality become pronounced in such scenarios.

Firstly, VR-based combat sports help increase energy expenditure in individuals with disabilities (see Table 2). An experiment tested the energy expenditure of 10 chronic stroke patients using Wii Sports for 15 min each of boxing and tennis activities (20). Due to physical limitations, 2 subjects could not complete the boxing game, and 3 did not participate in the tennis game. Except for one tennis participant, all other participants had an energy expenditure of ≥3 MET during the game sessions, with boxing (4.1 MET) slightly higher than tennis (3.7 MET), but the difference was not significant. The perceived exertion during boxing (5.3 MET) was higher than tennis (4.1 MET) (p < 0.05). Wii boxing, whether in single-player or multiplayer mode, provided moderate-level (MET >3.3) physical activity opportunities for children with unilateral cerebral palsy (19). The frequency of punching with the non-dominant arm was significantly higher in single-player mode, possibly because children are more relaxed without competition. In multiplayer mode, the frequency of punching with the dominant arm was higher, though not significant. Participants reported a preference for multiplayer games, and that the interactivity and enjoyable nature of multiplayer games may drive them to use Wii sports more actively. However, compared with single-player games, this may not be conducive to the recovery and treatment of their hemiplegic hand.

Secondly, VR-based combat sports help increase the intensity of physical activity. Regarding the evaluation of aerobic exercise intensity using the anaerobic threshold (AT) and respiratory compensation point (RCP), researchers organized four interventions consisting of virtual reality games (VRG) for 12 chronic hemiparetic stroke survivors, with 3 min of tennis, 1-min match change, and 4 min of boxing per group, with a 2-min interval between groups (46). Such interventions did not provide sufficient aerobic stimulus. Although heart rate (HR) and oxygen consumption (VO2) showed good reproducibility during VRG, VO2 was significantly lower than the AT and RCP, indicating only low-intensity aerobic exercise levels. Therefore, to enhance the aerobic capacity of stroke survivors through VRG, it is necessary to increase the intensity or volume of training. Additionally, authors found that HR and VO2 during boxing matches were always higher than tennis matches. A similar study further validated these findings in 8 spinal cord injury paraplegic patients (47). None reached the AT level during tennis matches, but 5 did during boxing matches, and energy expenditure (EE) during boxing matches of 3.0 (2.0–3.9). The MET values were also higher than those in tennis matches (mean = 2.3). However, Three-quarters of the participants had an EE below 3 MET during the entire game movement period.

Considering the physical limitations of individuals with disabilities, using relative exercise intensity (i.e., as a percentage of peak oxygen consumption or peak heart rate) is also a reasonable option. In a study, 24 wheelchair-dependent spinal cord injury patients played 3 different sports games (X-box Kinect, Fruit Ninja; Nintendo Wii, Wii Sports Boxing; VR Oculus Rift, boxing) for 15 min each with a 5-min break in between (48). Participants exercised an average of 6.6 min at high intensity, 24.5 min at moderate intensity, and 13.9 min at low intensity during the games (48). There was no significant difference in the time spent at moderate exercise intensity among the three sports games. Interestingly, participants engaged in significantly more high-intensity exercise during VR compared to Kinect.

Another study assessed the exercise intensity level of 11 wheelchair boxers during VR training using the average percentage of maximum heart rate (49). This study found that virtual reality games were highly effective in maintaining the physical health of individuals with disabilities, achieving a moderate health level. Users also rated VR games very highly. Additionally, the authors found that an additional 0.5 kg of hand-held weight did not significantly change the heart rate and intensity during training (49).

4 Discussion and future directions

We found that there were relatively few literature on VR technology in combat sports, with the majority of interest focused on using virtual reality games for patient therapy, providing them with physical activity and energy expenditure. This further underscores the critical role of integrating VR with combat sports in advancing this field.

Regarding the research on the energy expenditure of virtual reality games for individuals with disabilities, tennis and boxing are two popular sports. Three papers indicated that energy expenditure during VR boxing was higher than during tennis, including heart rate and VO2 (20, 46, 47). Two studies demonstrated that VR games could achieve a MET level of 3 for users (19, 20), while another study reported the opposite result (47), with 75% of individuals having energy expenditure below 3 MET during the game. This discrepancy may be related to different types of disabilities among users and inconsistent durations of gameplay. Therefore, future research should investigate the moderating effects by disabilities and focus on the effective duration. Existing literature indicates that VR games can only achieve low-intensity aerobic exercise standards for patients (46, 47). Subsequent research should explore ways to increase aerobic exercise intensity to better meet the exercise needs of individuals with disabilities.

Currently, we have observed that among various combat sports, only boxing has been integrated with VR technology for medical applications or adaptive sports for individuals with disabilities. Given the proactive nature of combat sports and their emphasis on dynamic interaction with others and the environment, it raises the question: could incorporating other sports, such as taekwondo or kickboxing, lead to comparable results? These sports, which involve significant lower-body engagement, may potentially increase energy expenditure in individuals with disabilities, addressing the challenge of insufficient energy consumption. Exploring these possibilities represents an important direction for future research. Moreover, the inclusion of such activities could provide patients with the opportunity to enjoy diverse forms of exercise, fostering their motivation to engage consistently in rehabilitation programs or more energy-intensive activities.

5 Conclusion

From the unique perspective of combat sports, we reviewed the role of VR technology in healthcare and adaptive sports for individuals with disabilities. Virtual reality games have demonstrated significant value by addressing challenges that traditional therapy and training methods cannot fully overcome. However, exploration in this area remains insufficient. As a nascent field, it presents substantial opportunities for further investigation and innovation. In conclusion, our findings highlight that the integration of VR technology into combat sports represents a highly promising domain with tremendous potential for future development.

Author contributions

YL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CJ: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. HL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YS: Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ML: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YC: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. GZ: Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The 2024 Chongqing Sports Science Research Project (project number: A202476).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Mascret, N, Montagne, G, Devrièse-Sence, A, Vu, A, and Kulpa, R. Acceptance by athletes of a virtual reality head-mounted display intended to enhance sport performance. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2022) 61:102201. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2022.102201

2. Grosprêtre, S, Marcel-Millet, P, Eon, P, and Wollesen, B. How exergaming with virtual reality enhances specific cognitive and Visuo-motor abilities: an explorative study. Cogn Sci. (2023) 47:e13278. doi: 10.1111/cogs.13278

3. Kavanagh, S, Luxton-Reilly, A, Wuensche, B, and Plimmer, B. A systematic review of virtual reality in education. Themes Sci Technol Educ. (2017) 10:85–119.

4. Li, C, and Li, Y. Feasibility analysis of VR Technology in Physical Education and Sports Training. IEEE access. (2020). doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3020842

5. Oriti, D, Manuri, F, Pace, FD, and Sanna, A. Harmonize: a shared environment for extended immersive entertainment. Virtual Reality. (2023) 27:3259–72. doi: 10.1007/s10055-021-00585-4

6. Balestrino, R, and Schapira, AHV. Parkinson disease. Eur J Neurol. (2020) 27:27–42. doi: 10.1111/ene.14108

7. Gulati, S, and Sondhi, V. Cerebral palsy: an overview. Indian J Pediatrics. (2018) 85:1006–16. doi: 10.1007/s12098-017-2475-1

8. Vitrikas, K, Dalton, H, and Breish, D. Cerebral palsy: an overview. Am Fam Physician. (2020) 101:213–20.

9. Tater, P, and Pandey, S. Post-stroke movement disorders: clinical Spectrum, pathogenesis, and management. Neurol India. (2021) 69:272–83. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.314574

10. Ekstrand, E, and Brogårdh, C. Life satisfaction after stroke and the association with upper extremity disability, sociodemographics, and participation. PM&R. (2022) 14:922–30. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12712

11. Rosengren, L, Forsberg, A, Brogårdh, C, and Lexell, J. Life satisfaction and adaptation in persons with Parkinson’s disease—a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:3308. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063308

12. Lei, C, Sunzi, K, Dai, F, Liu, X, Wang, Y, Zhang, B, et al. Effects of virtual reality rehabilitation training on gait and balance in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0224819. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224819

13. Ravi, DK, Kumar, N, and Singhi, P. Effectiveness of virtual reality rehabilitation for children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: an updated evidence-based systematic review. Physiotherapy. (2017) 103:245–58. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2016.08.004

14. Nambi, G, Abdelbasset, WK, Elsayed, SH, Alrawaili, SM, Abodonya, AM, Saleh, AK, et al. Comparative effects of isokinetic training and virtual reality training on sports performances in university football players with chronic low Back pain-randomized controlled study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2020) 2020:e2981273. doi: 10.1155/2020/2981273

15. Wood, G, Wright, DJ, Harris, D, Pal, A, Franklin, ZC, and Vine, SJ. Testing the construct validity of a soccer-specific virtual reality simulator using novice, academy, and professional soccer players. Virtual Reality. (2021) 25:43–51. doi: 10.1007/s10055-020-00441-x

16. Kang, S, and Kang, S. The study on the application of virtual reality in adapted physical education. Clust Comput. (2019) 22:2351–5. doi: 10.1007/s10586-018-2254-4

17. Yu, K, Wen, S, Xu, W, Caon, M, Baghaei, N, and Liang, H-N. Cheer for me: effect of non-player character audience feedback on older adult users of virtual reality exergames. Virtual Reality. (2023) 27:1887–903. doi: 10.1007/s10055-023-00780-5

18. Graves, LEF, Ridgers, ND, Williams, K, Stratton, G, Atkinson, G, and Cable, NT. The physiological cost and enjoyment of Wii fit in adolescents, young adults, and older adults. J Phys Act Health. (2010) 7:393–401. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.3.393

19. Howcroft, J, Fehlings, W, Karl, Z, Jan, A, and Biddiss, E. A comparison of solo and multiplayer active videogame play in children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Games Health J. (2012) 1:287–93. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2012.0015

20. Hurkmans, HL, Ribbers, GM, Streur-Kranenburg, MF, Stam, HJ, and van den Berg-Emons, RJ. Energy expenditure in chronic stroke patients playing Wii sports: a pilot study. J Neuroeng Rehabil. (2011) 8:38. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-8-38

21. Dębska, M, Polechoński, J, Mynarski, A, and Polechoński, P. Enjoyment and intensity of physical activity in immersive virtual reality performed on innovative training devices in compliance with recommendations for health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:19. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16193673

22. Lyons, EJ, Tate, DF, Ward, DS, Bowling, JM, Ribisl, KM, and Kalyararaman, S. Energy expenditure and enjoyment during video game play: differences by game type. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2011) 43:1987–93. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318216ebf3

23. Lyons, EJ, Tate, DF, Ward, DS, Ribisl, KM, Bowling, JM, and Kalyanaraman, S. Engagement, enjoyment, and energy expenditure during active video game play. Health Psychol. (2014) 33:174–81. doi: 10.1037/a0031947

24. Warburton, DER, Bredin, SSD, Horita, LTL, Zbogar, D, Scott, JM, Esch, BTA, et al. The health benefits of interactive video game exercise. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2007) 32:655–63. doi: 10.1139/H07-038

25. Ottoboni, G, Russo, G, and Tessari, A. What boxing-related stimuli reveal about response behaviour. Journal of Sports Sciences. (2015) 33:1019–1027. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2014.977939

26. Rojas-Sánchez, MA, Palos-Sánchez, PR, and Folgado-Fernández, JA. Systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis on virtual reality and education. Educ Inf Technol. (2023) 28:155–92. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11167-5

27. Vasconcelos, BB, Protzen, GV, Galliano, LM, Kirk, C, and Del Vecchio, FB. Effects of high-intensity interval training in combat sports: a systematic review with Meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. (2020) 34:888–900. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003255

28. Demeco, A, Zola, L, Frizziero, A, Martini, C, Palumbo, A, Foresti, R, et al. Immersive virtual reality in post-stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review. Sensors. (2023) 23:1712. doi: 10.3390/s23031712

29. So, BP-H, Lai, DK-H, Cheung, DS-K, Lam, W-K, Cheung, JC-W, and Wong, DW-C. Virtual reality-based immersive rehabilitation for cognitive- and behavioral-impairment-related eating disorders: a VREHAB framework scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:5821. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19105821

30. Wu, J, Zhang, H, Chen, Z, Fu, R, Yang, H, Zeng, H, et al. Benefits of virtual reality balance training for patients with Parkinson disease: systematic review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-regression of a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Serious Games. (2022) 10:e30882. doi: 10.2196/30882

31. Adie, K, Schofield, C, Berrow, M, Wingham, J, Freeman, J, Humfryes, J, et al. Does the use of Nintendo Wii sports™ improve arm function and is it acceptable to patients after stroke? Publication of the protocol of the trial of Wii™ in stroke – TWIST. Int J Gen Med. (2014) 7:475–81. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S65379

32. Saposnik, G, Teasell, R, Mamdani, M, Hall, J, McIlroy, W, Cheung, D, et al. Effectiveness of virtual reality using Wii gaming Technology in Stroke Rehabilitation: a pilot randomized clinical trial and proof of principle. Stroke. (2010) 41:1477–84. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.584979

33. Deutsch, JE, Borbely, M, Filler, J, Huhn, K, and Guarrera-Bowlby, P. Use of a low-cost, commercially available gaming console (Wii) for rehabilitation of an adolescent with cerebral palsy. Phys Ther. (2008) 88:1196–207. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080062

34. Gordon, C, Roopchand-Martin, S, and Gregg, A. Potential of the Nintendo Wii™ as a rehabilitation tool for children with cerebral palsy in a developing country: a pilot study. Physiotherapy. (2012) 98:238–42. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2012.05.011

35. Howcroft, J, Klejman, S, Fehlings, D, Wright, V, Zabjek, K, Andrysek, J, et al. Active video game play in children with cerebral palsy: potential for physical activity promotion and rehabilitation therapies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2012) 93:1448–56. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.02.033

36. Silva, F. D.Da, Polese, J. C., Alvarenga, L. F. C., and Schuster, R. C. (2013). Efeitos da Wiireabilitação Na Mobilidade de Tronco de Indivíduos com Doença de Parkinson: Um Estudo Piloto. Revista Neurociências, 21:364–368. doi: 10.34024/rnc.2013.v21.8159

37. Campo-Prieto, P, Cancela-Carral, JM, and Rodríguez-Fuentes, G. Wearable immersive virtual reality device for promoting physical activity in Parkinson’s disease patients. Sensors. (2022) 22:9. doi: 10.3390/s22093302

38. Carregosa, AA, Aguiar dos Santos, LR, Masruha, MR, Coêlho, MLDS, Machado, TC, Souza, DCB, et al. Virtual rehabilitation through Nintendo Wii in Poststroke patients: follow-up. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2018) 27:494–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.09.029

39. Kaur, A, Balaji, GK, Sahana, A, and Karthikbabu, S. Impact of virtual reality game therapy and task-specific neurodevelopmental treatment on motor recovery in survivors of stroke. Int J Ther Rehabil. (2020) 27:1–11. doi: 10.12968/ijtr.2019.0070

40. Ersoy, C, and Iyigun, G. Boxing training in patients with stroke causes improvement of upper extremity, balance, and cognitive functions but should it be applied as virtual or real? Top Stroke Rehabil. (2021) 28:112–26. doi: 10.1080/10749357.2020.1783918

41. Abdulsatar, F, Walker, RG, Timmons, BW, and Choong, K. “Wii-Hab” in critically ill children: a pilot trial. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. (2013) 6:193–202. doi: 10.3233/PRM-130260

42. Lai, B, Powell, M, Clement, AG, Davis, D, Swanson-Kimani, E, and Hayes, L. Examining the feasibility of early mobilization with virtual reality gaming using head-mounted display and adaptive software with adolescents in the pediatric intensive care unit: case report. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. (2021) 8:e28210. doi: 10.2196/28210

43. Harvie, DS, Rio, E, Smith, RT, Olthof, N, and Coppieters, MW. Virtual reality body image training for chronic low Back pain: a single case report. Front Virtual Real. (2020) 1. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2020.00013

44. Gouveia E Silva, EC, Lange, B, Bacha, JMR, and Pompeu, JE. Effects of the interactive videogame Nintendo Wii sports on upper limb motor function of individuals with post-polio syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Games Health J. (2020) 9:461–71. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2019.0192

45. Lotan, M, Yalon-Chamovitz, S, and Weiss, PL. Virtual reality as means to improve physical fitness of individuals at a severe level of intellectual and developmental disability. Res Dev Disabil. (2010) 31:869–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.01.010

46. Silva de Sousa, JC, Torriani-Pasin, C, Tosi, AB, Fecchio, RY, Costa, LAR, and Forjaz, CLDM. Aerobic stimulus induced by virtual reality games in stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2018) 99:927–33. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.01.014

47. Tosi, AB, de Sousa, JCS, de Moraes Forjaz, CL, and Torriani-Pasin, C. Physiological responses during active video games in spinal cord injury: a preliminary study. Physiother Theory Pract. (2022) 38:1373–80. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2020.1852635

48. Wouda, MF, Gaupseth, J-A, Bengtson, EI, Johansen, T, Brembo, EA, and Lundgaard, E. Exercise intensity during exergaming in wheelchair-dependent persons with SCI. Spinal Cord. (2023) 61:338–44. doi: 10.1038/s41393-023-00893-3

49. Polechoński, J, Langer, A, Akbaş, A, and Zwierzchowska, A. Application of immersive virtual reality in the training of wheelchair boxers: evaluation of exercise intensity and users experience additional load– a pilot exploratory study. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. (2024) 16:80. doi: 10.1186/s13102-024-00878-6

Keywords: virtual reality, boxing, combat sports, rehabilitation, adaptive physical activities

Citation: Li Y, Jiang C, Li H, Su Y, Li M, Cao Y and Zhang G (2025) Combat sports in virtual reality for rehabilitation and disability adaptation: a mini-review. Front. Public Health. 13:1557338. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1557338

Edited by:

Wellington Pinheiro dos Santos, Federal University of Pernambuco, BrazilReviewed by:

Jie Hao, Southeast Colorado Hospital, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Li, Jiang, Li, Su, Li, Cao and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guodong Zhang, Z3VvZG9uZy16aGFuZ0Bmb3htYWlsLmNvbQ==

Yike Li

Yike Li Chun Jiang

Chun Jiang Hansen Li

Hansen Li Yuqin Su

Yuqin Su Mengyao Li4

Mengyao Li4 Yang Cao

Yang Cao Guodong Zhang

Guodong Zhang