95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Public Health , 18 March 2025

Sec. Public Health Education and Promotion

Volume 13 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1548544

This article is part of the Research Topic Integrating Oral Health into Public Health: Bridging Gaps to Reduce Health Disparities in the US View all 7 articles

Solutions to advance oral health equity require a deeper understanding only achieved though partnership with the communities deeply impacted by barriers to care. While numerous studies and dental public health reports published over the years demonstrate a need for oral health equity, there is a paucity of literature regarding community engagement as a pathway to advancing oral health equity. As a human-centered design approach, Community-Engaged Research (CER) provides opportunities to engage communities as research partners, while developing trust and capacity for sustainable collaboration and participatory systems thinking. Building on literature and our experiences from leading a community-engaged oral health equity project in Texas, this perspective article offers actionable concepts of trust, time, and co-design to encourage the use of community-engaged practices that assess and address complex factors that impact oral health.

Numerous studies and dental public health reports published over the years demonstrate the importance of oral health due to the intrinsic connection to overall wellbeing, yet there is a paucity of literature regarding community-engaged research as a pathway to understanding and addressing barriers to oral and overall health (1). As a human-centered approach, Community-Engaged Research (CER) provides opportunities to engage communities as research partners (2–4), while simultaneously building trust (5), pathways, and capacity for sustainable solutions (6). Additionally, CER goes beyond the typical methods utilized for community health needs assessments or research by exploring research questions in authentic collaboration with the communities who experience the direct impacts of a given health concern. Put simply, where traditional research may be inadvertently exploitive of populations as subjects of academic inquiry, CER creates an opportunity to explore the issues with the community as co-investigators. Furthermore, evidence suggests the use of CER for health education, public health, social science (6), medicine (7), and oral health (2) research has benefited community (8), workforce development (9), and practice (10). Additionally, evidence and guidance from the American Dental Association (11, 12), Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors (13), United States Surgeon General (14), and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) (15) support the use of community-based approaches. Despite the need, there is limited literature available on the practical application and benefits of CER in oral health (2, 16) to (re)build trust and capacity building for systems change (17–19). As such, this perspective article highlights our experiences with community-engaged research to offer practical solutions for those seeking to use CER as a pathway to advance oral health equity across the United States.

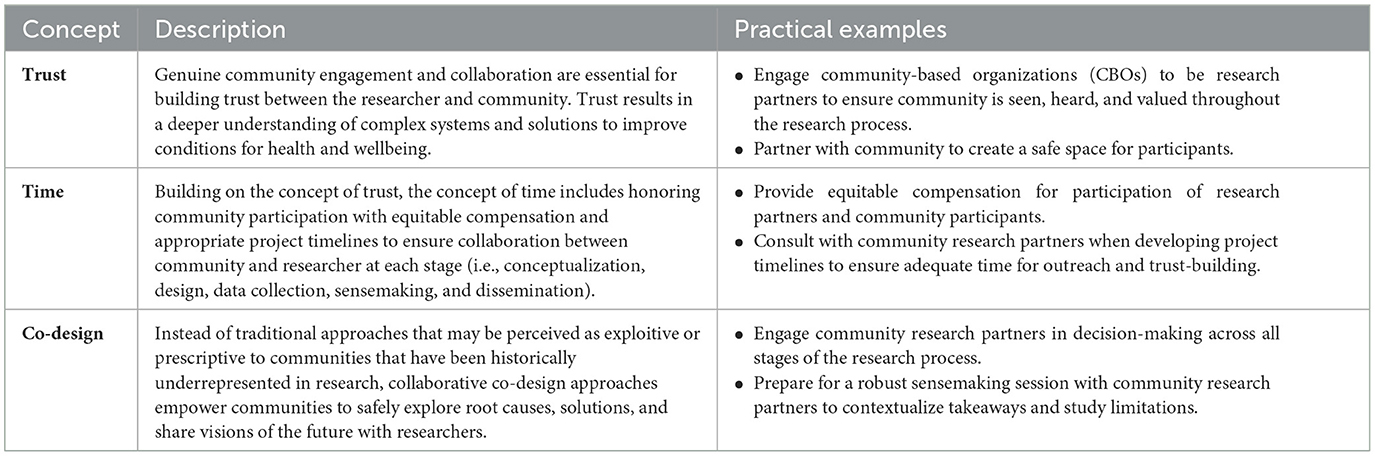

In 2023, we began an oral health initiative that sought: (1) a deeper understanding of the systems and conditions impacting oral health in Texas, and (2) action-oriented strategies to inform others working to advance population oral health in Texas and across the United States (20). The population and political contexts of Texas provide a unique opportunity to explore oral health needs by race, ethnicity, language, rurality, sexual orientation, gender identity, and disability status in a context where the voices of those inhabiting these identities have been historically marginalized in the oral health, public health, and political context. To accomplish this purpose and in recognition of the importance of CER to do so, we partnered with eight community-based organizations located throughout the state. As research partners on this initiative, the CBOs represented and advocated for their respective communities deeply impacted by barriers to oral healthcare. Together, we co-designed and conducted culturally and linguistically appropriate focus groups, contextualized findings during a sensemaking session to validate takeaways and limitations, and discussed strategies for next steps to include dissemination of the findings. In addition to this collaborative approach with CBOs, we also conducted key informant interviews with individuals leading oral health initiatives across the state. Insights from these interviews provided systems and political context. We triangulated findings from publicly available quantitative data, focus groups, and key informant interviews to develop actionable insights. While not exhaustive, the synthesis of community voices, context, and evidence informed the next phase of our oral health initiative. Drawing from our collective experiences with CER, this article focuses on three essential concepts to inform the practice of community-engaged research: (1) trust, (2) time, and (3) co-design (see also Table 1).

Table 1. Trust, time, and co-design: key concepts and practical examples of community-engaged research (CER).

As a human-centered approach, CER creates pathways for essential trust-building and a deeper understanding of the systems and conditions impacting oral health (5) that might not be achieved with traditional approaches (e.g., community health needs assessment or research project entirely led by an academic or research organization). Additionally, traditional research methods may be perceived by the study population as exploitive, transactional, or traumatic—particularly when they do not feel seen, heard, or valued throughout the research process. Without the valuable input and expertise from the impacted communities, methodologies that are entirely researcher-led may miss the opportunity to build trust that is crucial to understanding complex issues and developing sustainable solutions to address identified needs. As an alternative approach, the use of CER provides opportunities to engage the community in all phases of research—from design to dissemination, ensuring community voices are seen, heard, and valued. This collaboration between researchers and the community is essential to advance health equity, power scientific research, and implement effective solutions (5).

From our experiences with trust-building during this oral health initiative, we suggest researchers engage community-based organizations (CBOs) to serve as research partners given their roles as trust and cultural brokers within their respective communities and geographies. We selected and engaged our CBO research partners because they had well-established relationships and shared lived experiences with each of their respective populations—Texas-Mexico border communities (21, 22), rural residents of East Texas, members of historically Black neighborhoods of Houston and Austin (23, 24), and advocacy groups (25) representing faith leaders, Texans who have disabilities or special health care needs, and those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning, and other identities of the LGBTQ+ community. These organizations are well-positioned to speak to the unique needs of their communities, while collectively painting a portrait of the state as a whole.

In our partnership with CBOs, we also learned the importance of creating a safe space for participants. For example, we found focus group participants were more forthcoming in their responses due to their well-established relationships and shared experiences with the CBO. The CBOs facilitated conversations during the focus groups ultimately led to a deeper understanding of systems and conditions. Additionally, community members may be hesitant to participate in focus groups led by outside organizations due to fear or negative experiences. In an effort to mitigate this hesitancy, we co-designed transparent, plain-language communication strategies outlining the purpose of our research, consent process, and how we planned to utilize the findings while protecting their privacy. We feel this was essential to the success of our project and underscores the importance of trust and safety during recruitment, data collection, and reporting stages of research in ways that go beyond Institutional Review Board (IRB) requirements.

Building on the concept of trust, the concept of time is largely focused on the importance of the examples of equitable compensation and appropriate project timelines. In typical research approaches, participants may receive pre-determined incentives or compensation for attending a focus group. A project timeline might also be developed by the researcher without input from the community research partner—who may advise more time allocated to trust-building outreach. From our experience with CER on this project, we recommend that the compensation strategies and project timelines be developed with the CBO research partners.

Compensation strategies should include payment for the participating CBOs for their time as research partners, as well as the appropriate amount (and method) for community participants. In these compensation strategies, consider the valuable time participants take out of their busy schedules, transportation, food, and childcare. Also consider the logistics of compensation strategies to include the method of compensation (e.g., physical gift card vs. digital gift card, other forms of compensation). Consider also the importance of trust when discussing the logistics of compensation delivery, as participants may be hesitant to create digital footprints, or they may perceive the ‘gift card' as transactional. Your community research partners will offer valuable insights to create compensation strategies that simultaneously build trust and value the time of participants.

From a practical perspective, planning appropriate timelines for CER partnership activities can be challenging, as each project may vary due to budget and scope. Where possible and applicable, we recommend that timelines be co-developed with community research partners and rightsized accordingly. This requires researchers to create a space for partnership while honoring the time and capacity of community partners in critical phases of conceptualization, design, data collection, sensemaking, and dissemination. We explore this further in our next critical concept of co-design.

Building on the concepts of trust and time outlined above, co-design restores power and decision-making to communities that have been historically underrepresented in research, or who may perceive research as exploitive. Collaborative, co-design approaches empower communities to safely explore root causes, solutions, and share visions of the future (3) to improve systems and delivery of person-centered oral health care (26). Co-design is crucial to the success of CER.

From our experiences with CER on this project and seeing the eagerness of community to be seen, heard, and valued, we recommend integrating co-design in all stages of research. We conducted a kick-off meeting with CBOs to align our approach to this project and offered training on focus group facilitation. We feel their input on all stages of the project—from kick-off to dissemination—brought value to our project and understanding of oral health in Texas. In some cases, researchers may be critical of including partners in sensemaking (27, 28) and choose not to include community voice in soliciting feedback or interpretations. This exclusion may leave partners feeling exploited and less willing to participate in subsequent activities led by academic-focused individuals or organizations. By providing a venue and compensation for community partners to provide input during all stages, researchers demonstrate they are open to critique and recommendations—research quality and translation of findings into action.

For our project, community research partners had autonomy of their focus groups—location (virtual or in-person), date and time, method of participant compensation, and language—to create a safe and welcoming space that best meet the needs of their communities. As researchers, this may present an initial sense of discomfort due to the uncertainty that comes with sharing power typically only reserved for the ‘academic' in the partnership, and it may create challenges in navigating requirements set forth by an Institutional Review Board (IRB). This sense of discomfort and uncertainty underscores the importance of sharing best practices and strategies to encourage utilization of CER as a pathway to advancing oral health equity, ensure research integrity during co-design processes that inherently restore power to historically underrepresented communities, and address emerging concerns such as the rapidly evolving use of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

To prepare for a robust sensemaking with CBOs to contextualize findings and discuss study limitations, we conducted an initial inductive coding of qualitative data and organized emerging themes into a brief presentation. During the virtual sensemaking, we facilitated interactive discussions to explore the findings, limitations, considerations for reporting to ‘traditional' audiences (e.g., academic, public health professionals), and most importantly, returning the findings to community audiences to demonstrate how their participation is making an impact.

Community-engaged research (CER) provides a vital pathway to understand and address community, system, and policy barriers to the delivery of person-centered oral health care. Through active collaboration with the communities deeply impacted by barriers to timely, person-centered oral health care, CER serves a dual role—as a methodology and mechanism—that builds shared understanding, trust, and capacity essential for sustainable, impactful change. This article provides perspectives on concepts of trust, time, and co-design to guide genuine community engagement throughout the research process. A similar endeavor at the national level, “Barriers to Oral Health Care” led by the U.S Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, provides similar evidence and support for collaboration with community to advance the delivery of holistic, person-centered oral health care (29). To that end, while the alignment between these projects demonstrates the importance for continued community-engagement, more research on the practice of CER is needed. Moving forward, investments in training and capacity-building to implement CER are essential. Researchers and practitioners must be equipped with the tools and skills needed to engage communities effectively, including training in cultural humility, trauma-informed practices, and equitable partnership development. Funding mechanisms should also prioritize longer-term projects that allow for sustained trust-building, iterative collaboration, and support equitable compensation that respectfully honors the lived experience and expertise that community members bring to these efforts. Lastly, scientific venues and journals must expand their focus to highlight and share CER work, including lessons learned and best practices. Providing platforms for these efforts not only validates the importance of CER but also facilitates knowledge exchange, fosters innovation, and supports the replication and adaptation of successful strategies across different contexts.

As a result of our collaborative, community-engaged approach, we achieved a deeper understanding of the systems and conditions impacting oral health in Texas and identified opportunities within and beyond the context of clinical care to improve oral health. Despite triangulating our data sources (publicly available quantitative data, community-led focus groups, and qualitative interviews with key informants), limitations of CER include, but are not limited to the following: bias due to convenience sampling, community participants may have higher level of awareness of health resources or issues due to well-established relationships with CBOs, and the generalizability of focus groups may not be applicable for all in Texas and beyond. However, because of the input of our community research partners, we also have a deeper understanding of the study limitations.

We offer our perspectives and practical examples of CER to promote its use in public health. As such, we are thankful for our partnership with community and their trust as we continue to respectfully lift their voices in the pursuit of oral health equity for all.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

CP: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft. BW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AJ: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work would not have been possible without funding support from the CareQuest Institute for Oral Health.

Texas Health Institute would like to thank community members and key informants for sharing their perspectives and trusting us to respectfully lift their voices for the advancement of oral health equity and the eight community-based organizations who served as research partners on this project: Acres Homes Community Advocacy Group, Area Health Education Center, Cancer and Chronic Disease Consortium, Equality Texas, Maternal Health Equity Collaborative (Black Mamas ATX), Texas Impact, Texas Parent to Parent, and Tri-County Community Action. The team would also like to acknowledge Evelyn Nguyen, MPH, CPH, for her support, data analysis, and partnership on this project.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Nghayo HA, Palanyandi CE, Ramphoma KJ, Maart R. Oral health community engagement programs for rural communities: a scoping review. PLoS ONE. (2024) 19:e0297546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0297546

2. Chew C, Rosen D, Watson K, D'alesio A, Ellerbee D, Gloster J, et al. Implementing a community engagement model to develop a community-driven oral health intervention. Prog Community Health Partners. (2024) 18:67–77. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2024.a922331

3. Collaborating for Equity and Justice: Moving Beyond Collective Impact—Non Profit News. Nonprofit Quarterly. Available online at: https://nonprofitquarterly.org/collaborating-equity-justice-moving-beyond-collective-impact/ (accessed December 12, 2024).

4. Hacker K. Community-Based Participatory Research. 1 Oliver's Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP: SAGE Publications, Inc. (2013). Available online at: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/community-based-participatory-research (accessed December 12, 2024).

5. Gibbons GH, Pérez-Stable EJ. Harnessing the power of community-engaged research. Am J Public Health. (2024) 114:S7–11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2023.307528

6. Wallerstein N, Oetzel JG, Sanchez-Youngman S, Boursaw B, Dickson E, Kastelic S, et al. Engage for equity: a long-term study of community-based participatory research and community-engaged research practices and outcomes. Health Educ Behav. (2020) 47:380–90. doi: 10.1177/1090198119897075

7. Barkin S, Schlundt D, Smith P. Community-engaged research perspectives: then and now. Acad Pediatr. (2013) 13:93–7. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.12.006

8. Finlayson TL, Asgari P, Hoffman L, Palomo-Zerfas A, Gonzalez M, Stamm N, et al. Formative research: using a community-based participatory research approach to develop an oral health intervention for migrant Mexican families. Health Promot Pract. (2017) 18:454–65. doi: 10.1177/1524839916680803

9. Smith PD, Murray M, Hoffman LS, Ester TV, Kohli R. Addressing black men's oral health through community engaged research and workforce recruitment. J Public Health Dent. (2022) 82:83–8. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12508

10. Tiwari T, Sharma T, Harper M, Zacher T, Roan R, George C, et al. Community based participatory research to reduce oral health disparities in American Indian children. J Fam Med. (2015) 2:1028.

11. Rodriguez JL, Thakkar-Samtani M, Heaton LJ, Tranby EP, Tiwari T. Caries risk and social determinants of health: a big data report. J Am Dent Assoc. (2023) 154:113–21. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2022.10.006

12. Bastos JL, Borde E. What do we mean by social determinants of oral health?: on the multiple—and sometimes pernicious—uses of social determinants of health in public health and dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. (2024) 155:360–1. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2023.07.001

13. Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors. Policy Statement: Social Determinants of Health and Improving Oral Health Equity (2023).

14. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America—A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health (2000). Available online at: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2017-10/hck1ocv.%40www.surgeon.fullrpt.pdf (accessed February 4, 2024).

15. Anderson O. Building a Legacy: Dr. Natalia Chalmers on her Work at CMS. American Dental Association News (2024). Available online at: https://adanews.ada.org/ada-news/2024/september/building-a-legacy-dr-natalia-chalmers-on-her-work-at-cms/ (accessed November 25, 2024).

16. McNeil DW, Randall CL, Baker S, Borrelli B, Burgette JM, Gibson B, et al. Consensus statement on future directions for the behavioral and social sciences in oral health. J Dent Res. (2022) 101:619–22. doi: 10.1177/00220345211068033

17. Jones JM. Confidence in U.S. Institutions Down; Average at New Low. Gallup (2022). Available online at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/394283/confidence-institutions-down-average-new-low.aspx (accessed November 25, 2024).

18. Saad L. Historically Low Faith in U.S. Institutions Continues (2023). Available online at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/508169/historically-low-faith-institutions-continues.aspx (accessed November 25, 2024).

19. Kennedy B, Funk C. Americans' Trust in Scientists, Other Groups Declines. Pew Research Center (2022). Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/02/15/americans-trust-in-scientists-other-groups-declines/ (accessed November 25, 2024).

20. Texas Health Institute. Advancing Oral Health Equity in Texas: A Community-Driven Approach (2024). Available online at: https://texashealthinstitute.org/ (accessed November 25, 2024).

21. Area Health Education Center Facebook Page. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/AreaHealthEducationCenter/ (accessed November 10, 2024).

22. CCDC. Home (2024). Available online at: http://www.swccdc.org/html/index.html (accessed November 10, 2024).

23. It's Time to Show Up for Black Mothers—Black Mamas ATX. Available online at: https://blackmamasatx.com/ (accessed November 10, 2024).

24. Home. Acres Homes CAG (2024). Available online at: https://www.acreshomescag.org/ (accessed November 10, 2024).

25. Tri-County Community Action, Inc.—Nonprofit-Center, Texas. Available online at: https://tccainc.org/ (accessed November 10, 2024).

26. CareQuest Institute for Oral Health. Engaging Community. (2023). Available online at: https://www.carequest.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/Final_CareQuest_Institute_Engaging-Community_3.16.23.pdf

27. Motulsky SL. Is member checking the gold standard of quality in qualitative research? Qual Psychol. (2021) 8:389–406. doi: 10.1037/qup0000215

28. Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual Health Res. (2016) 26:1802–11. doi: 10.1177/1049732316654870

29. U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The Barriers to Oral Health Care Illustration. CMS (2023). Available online at: https://www.cms.gov/priorities/key-initiatives/burden-reduction/about-cms-office-burden-reduction-health-informatics/barriers-oral-health-care-illustration (accessed February 4, 2024).

Keywords: community, oral health equity, human-centered design, community-engaged research, system transformation

Citation: Price C, Williams B, Jacks AM and Sanghavi A (2025) Community-engaged research as a pathway to oral health equity: insights from a Texas initiative. Front. Public Health 13:1548544. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1548544

Received: 19 December 2024; Accepted: 28 February 2025;

Published: 18 March 2025.

Edited by:

Carla Shoff, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, United StatesReviewed by:

Shenam Ticku, Harvard University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Price, Williams, Jacks and Sanghavi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Blair Williams, YndpbGxpYW1zQHRleGFzaGVhbHRoaW5zdGl0dXRlLm9yZw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.