94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health, 26 February 2025

Sec. Occupational Health and Safety

Volume 13 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1547818

This article is part of the Research TopicAdvances in Radiation Research and Applications: Biology, Environment and MedicineView all 7 articles

Yanjun Xie1,2,3†

Yanjun Xie1,2,3† Xining Wang1,2,3†

Xining Wang1,2,3† Yuemin Lan1,4†

Yuemin Lan1,4† Xinyu Xu2,3

Xinyu Xu2,3 Shaoteng Shi2,3

Shaoteng Shi2,3 Zhihao Yang2,3

Zhihao Yang2,3 Hongqiu Li2,3

Hongqiu Li2,3 Jing Han2,3*‡

Jing Han2,3*‡ Yulong Liu1,4*‡

Yulong Liu1,4*‡Background: Radiation literacy, encompassing the understanding of basic principles, applications, risks, and protective measures related to ionizing radiation, is critical for medical personnel working in jobs that involve the use of radioactive materials or medical imaging. In the context of nuclear emergency preparedness, the level of radiation knowledge among healthcare professionals—such as doctors, nurses, and radiographers—directly influences the effectiveness and safety of emergency responses. This study aims to address this gap by evaluating the radiation knowledge of medical personnel and identifying areas for improvement in profession-specific training programs.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted using a convenience sampling method. The study included 723 participants attending a medical emergency response exercise and clinical management workshop on radiation injury in Suzhou, China, in November 2023. Data were collected through a structured questionnaire, descriptive statistics and chi-square tests were performed to analyze participants’ radiation knowledge and identify variations across different professional groups.

Results: The majority of participants were female (64.73%), married (75.10%), and held an undergraduate degree (69.99%). Nurses (40.11%) and clinical doctors (30.29%) constituted the largest professional groups. Significant disparities in radiation knowledge were observed among healthcare workers. Nurses and management personnel demonstrated a stronger grasp of fundamental radiation concepts, such as radioactive nuclides and absorbed doses, compared to clinical doctors. For instance, 85.52% of nursing personnel and 72.34% of management personnel accurately identified the half-life of iodine-131, while only 49.32% of clinical doctors showed comparable knowledge. Furthermore, substantial differences in radiation emergency response capabilities were noted across professions. These findings emphasize the necessity for tailored, profession-specific training programs in radiation protection and emergency preparedness.

Conclusion: The study reveals a generally insufficient understanding of basic radiation concepts and emergency response principles among medical personnel. Significant variations in radiation knowledge were observed across different professional groups, highlighting the need for specialized training modules. These modules should focus on fundamental radiation concepts, radiation exposure effects, and emergency response protocols, with content customized to address the unique needs of each professional group. By implementing such targeted training, the overall effectiveness and safety of nuclear emergency responses can be significantly enhanced.

Radiation literacy is the understanding and knowledge of the basic principles, applications, risks and protective measures of ionizing radiation (1–3). Diagnostic and therapeutic procedures have been revolutionized with the use of nuclear technologies in the practice of medicine, providing remarkable accuracy and effectiveness (4, 5). However, while these technologies improve patient outcomes, they also pose potential risks to patients and healthcare professionals due to radiation exposure (6–8). Therefore, it is imperative that healthcare professionals have a thorough understanding of radiation safety principles in order to effectively minimize these risks.

Radiation healthcare professionals often work in jobs that involve the use of radioactive materials or medical imaging, where they are required to handle radioactive materials and equipment and are at risk of radiation exposure (9). China has issued multiple standards and technical specifications, such as the Basic Standards for Ionizing Radiation Protection and Radiation Source Safety (GB 18871-2002), which clarify the specific requirements and operational norms for radiation protection (10). Despite the critical importance of radiation safety, there is evidence to suggest that knowledge levels among healthcare professionals may be inadequate. The results of a study conducted showed that 63% of first responders had received training related to radiological terrorism, while only 50% of first responders had used personal protective equipment (PPE) in the past year (11). A research survey in China showed that clinical nurses scored 60.40 points in the nuclear emergency rescue knowledge test, with 0 scoring good or above, 52 scoring moderate (18.6%), 103 scoring passing (37.0%), and 124 scoring failing (44.4%) (12). These gaps in knowledge can lead to unsatisfactory safety measures and increase the likelihood of radiation injury (13). Therefore, there is a need to assess the current state of radiation knowledge among medical personnel, especially those who have received nuclear training, to identify areas for improvement.

In China, there are specific regulations and requirements for radiation protection in medical practice. According to the regulatory framework of the National Health and Wellness Commission of China, healthcare professionals working with ionizing radiation must obtain a radiation protection license, which requires completing an accredited training programme and passing a certification examination. These requirements are enforced by the National Health and Wellness Commission (NHWC), which sets radiation safety standards and ensures compliance through regular 2-yearly inspections and audits (14). Nuclear training courses are designed to equip medical personnel with the necessary skills and knowledge to handle and use radioactive materials safely. These programmes typically cover a range of topics including principles of radiation physics, radiation biology, radiation protection and regulatory requirements (15, 16). However, it is uncertain whether the local health department has implemented the relevant assessment requirements, and the effectiveness of these training programs in imparting sufficient radiation knowledge remains uncertain (17).

Although there have been many studies examining the level of knowledge and awareness of healthcare workers regarding radiation protection, these studies have tended to focus on specific professional groups or a single healthcare organization and have lacked a comprehensive investigation of the radiation knowledge of healthcare workers with different characteristics during their training for nuclear emergencies (18, 19). This study aims to fill this gap by covering healthcare workers with varying professional experiences across multiple regions. The novelty of this research lies in its broad scope and detailed analysis, which will provide a scientific foundation for developing more targeted radiation protection training programs, ultimately enhancing the preparedness and safety of medical staff in nuclear emergency situations.

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design to evaluate healthcare workers’ knowledge and practices regarding radiation protection during a Medical Emergency Response Exercise and Clinical Management of Nuclear and Radiation Injuries workshop in November 2023. The survey targeted healthcare professionals involved in radiation-related occupations, while those who refused to participate or did not complete the questionnaire were excluded from the analysis.

A structured questionnaire was used for data collection, consisting of 47 questions divided into five main sections. These sections were as follows: Part 1, Demographic Characteristics (9 questions); Part 2, Basic Knowledge of Radiation (10 questions); Part 3, Effects of Radiation Exposure (10 questions); Part 4, Radiation Emergency Response Capabilities (10 questions); and Part 5, Radiation Medical Management (8 questions). Prior to full-scale implementation, the questionnaire was piloted to ensure clarity, reliability, and validity. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in this scale is 0.745, which is greater than 0.7, indicating high reliability in all dimensions of the scale (Table 1). The KMO value in this scale is 0.817, and if the KMO value is greater than 0.8, it meets the conditions for conducting factor analysis. The Bartlett sphericity test result shows an approximate chi square value of 2142.503. In addition, a significance probability p < 0.01 indicates that a significant level has been reached (Table 2).

This study employed the Kendall sample estimation method with a sample size of 5–10 times the number of items in the scale. To minimize potential error, the sample size was expanded by 20%. The scale consisted of 47 items, and the sample size was 47*10/80% = 587.5. Ultimately, 723 healthcare professionals from a wide range of backgrounds, experience levels, and job roles participated in the survey. This included clinicians (219, 30.29%), medical technicians (120, 16.60%), nursing staff (290, 40.11%), and management staff (94, 13.00%).

Inclusion criteria encompassed healthcare professionals with radiation-related job roles, while exclusion criteria applied to those who opted out of the study or failed to complete the questionnaire in its entirety. Data were collected through a self-administered questionnaire distributed during the workshop. The completed questionnaires were uniformly numbered and entered into the dataset using EpiData 3.1 software to ensure data accuracy and consistency.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 27.0. A chi-square test was used to compare the percentage of correct answers across different job categories for each section of the questionnaire. Statistical significance was set at a threshold of p = 0.05.

This study included 723 participants, the majority of whom were female (64.73%) and married (75.10%). The demographic details of all participants are provided in Table 3. Most participants had an undergraduate level of education (69.99%), with a smaller proportion holding graduate degrees (10.37%). Regarding job titles, junior (34.85%) and intermediate (35.27%) positions accounted for the largest proportion. In terms of professional roles, the nursing staff made up the largest group (40.11%), followed by clinical doctors (30.29%), with management personnel representing the smallest group (13.00%).

Additionally, more than two-thirds of the respondents did not work in radiation medicine (78.28%) or participated in rescue operations (76.76%). However, a significant portion of the participants had taken part in exercises or training related to radiation medicine (44.40%) (Table 3).

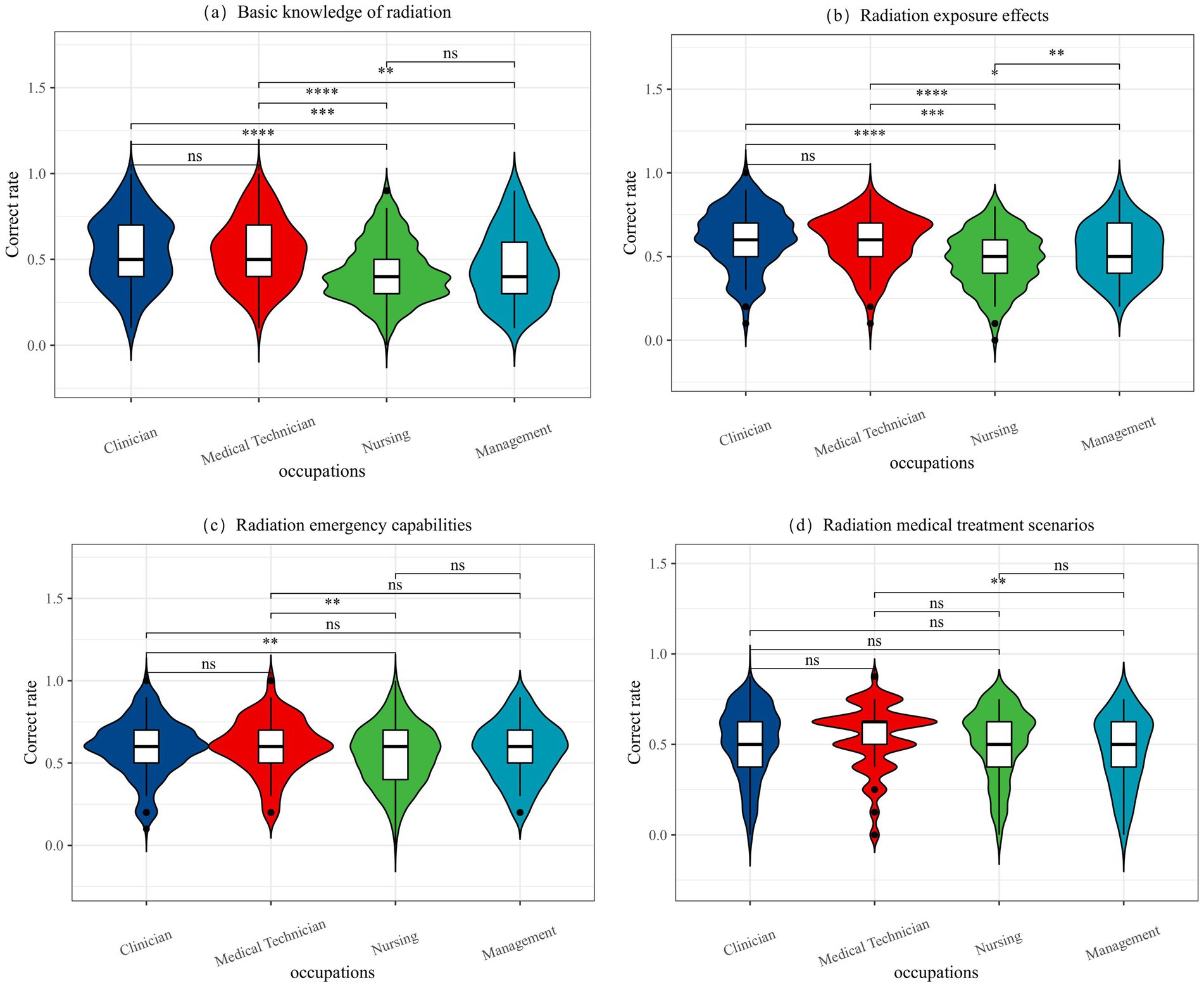

Table 4 and Figure 1 illustrate the differences in overall accuracy across the four knowledge modules among medical staff in different job types. The modules include basic knowledge of radiation, radiation exposure effects, radiation emergency capabilities, and radiation medical treatment scenarios. The average correct response rates for these modules were 49, 54, 57, and 51%, respectively. These results indicate that more than half of the medical workers lacked sufficient mastery of the fundamental knowledge related to radiation scenarios. In terms of individual knowledge modules, significant statistical differences were observed in the accuracy rates for basic knowledge of radiation, radiation exposure effects, and radiation emergency capabilities among medical personnel in different positions (p < 0.05). Specifically, management personnel demonstrated significantly lower accuracy rates compared to clinicians and nursing staff. However, in the module on radiation medical treatment scenarios, no significant differences were found in the correct response rates across the four occupational types, with all groups averaging around 50%.

Figure 1. The difference between the correct rate of each module in 4 occupations. (a) Basic knowledge of radiation, (b) Radiation exposure effects, (c) Radiation emergency capabilities, (d) Radiation medical treatment scenarios. “*” means that the difference between the two labeled is statistically significant (p < 0.05); the greater the number of “*,” the smaller the P; “ns” means that the difference between the two labeled is not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Table 5 highlights significant differences in basic radiation knowledge among different occupations. Nursing and management professionals demonstrated higher correct response rates on topics such as radioactive nuclides, absorbed dose, and the half-life of radioactive materials, with statistically significant differences (p < 0.05). While over half of the participants demonstrated an understanding of radiation hazards, clinical physicians had a relatively low correct response rate (49.32%, p < 0.001). Most nurses accurately identified the physical half-life of iodine-131 (85.52%, p < 0.001), whereas only a small proportion of clinical doctors correctly answered that photons are gamma rays and X-rays (22.83%, p = 0.029). Additionally, most medical technicians were able to correctly distinguish between nuclear emergencies and nuclear attacks (84.17%, p = 0.011), a difference that was statistically significant. Based on the data presented in Table 5, it is evident that nursing staff possess a relatively high level of radiation knowledge compared to other occupational groups.

Table 6 summarizes the understanding of the impact of radiation exposure on different professions. Nursing professionals consistently demonstrated high correct response rates, particularly in areas such as deterministic effects (18.28%, p < 0.001) and hematological syndrome (48.28%, p < 0.001). Both management and nursing professionals also achieved high scores in their understanding of the use of micronuclei for biological dose assessment, with correct response rates of 89.36 and 93.45%, respectively (p = 0.004). The importance of protecting infants and pregnant women from the risk of thyroid cancer was well recognized in each group, especially in nursing (87.59%, p < 0.001), and the differences were statistically significant (Table 6).

Table 7 highlights significant differences in radiation emergency knowledge among various professions. Nursing professionals recorded the highest correct response rates for radiation protection principles (35.86%) and the prevention of deterministic effects (16.55%), with statistically significant differences (p = 0.002 and p = 0.023, respectively). Management professionals demonstrated the highest understanding of international nuclear event levels, achieving a correct response rate of 50%, which was also statistically significant (p = 0.024). Clinicians led in their knowledge of the National Nuclear Emergency Medical Rescue Team’s rapid response and self-sufficiency, with a correct response rate of 65.75% (p = 0.031). These findings emphasize the variability in radiation emergency knowledge across professions and highlight the need for targeted training programs to address specific knowledge gaps among different occupational groups.

Table 8 shows the response levels of different professions regarding radiation medicine. Significant differences were observed in the knowledge related to high-dose local radiation therapy, with management and nursing professionals achieving the highest accuracy rates of 36.17 and 35.17%, respectively, and these differences were statistically significant (p < 0.001). In addition, a notable difference was observed in the understanding of the management of radiation medicine in second-level and higher hospitals, with management professionals scoring the highest at 53.19% (p = 0.032). However, other areas, such as prioritizing accident data collection and the role of hospital nursing and burn departments, did not show statistically significant differences. These results highlight variations in radiation rescue knowledge across different professions and underscore the need for targeted training in other occupational groups, as summarized in Table 8.

To sum up, our research has demonstrated that nursing and management personnel exhibit greater accuracy in basic radiation knowledge compared to clinical doctors and medical technicians, who tend to have lower accuracy rates. These findings highlight the disparities in radiation knowledge among various occupational groups and underscore the necessity for targeted training to enhance overall radiation response capabilities.

This study evaluated the radiation knowledge level of 723 medical personnel with different types of jobs, professional titles, educational backgrounds, and training experiences through a cross-sectional investigation. The results showed that medical personnel with different background characteristics had significant differences in basic radiation knowledge, radiation exposure effects, emergency response-ability, and medical treatment ability. This discovery prompts us to re-examine the effectiveness of current nuclear emergency preparedness training, particularly in addressing the training needs and knowledge gaps of medical personnel in different roles.

In terms of basic radiation knowledge, although most medical personnel have a sure grasp of practical knowledge such as “absorbed dose” and “α particle penetration distance, “the cognition degree of basic concepts such as “radionuclide” and “radioactivity” is generally not high, and the accuracy rate of clinicians and medical technicians is less than 30%. These differences not only reflect knowledge gaps between jobs and degrees, but also highlight the need to design educational content for different medical roles. This is consistent with the findings of Alghamdi et al. (20), who found that healthcare professionals have a woefully inadequate understanding of the concept of radiation and its implications. Similarly, Kew et al. (21) also found through a questionnaire survey that there was a noticeable gap in the theoretical knowledge of radiation protection among clinicians. These findings suggest the need to enhance the foundational theory of radiation training for medical staff. It is important to develop clear learning objectives tailored to the specific responsibilities of different medical roles. For example, clinicians may need to learn more about radiation protection and radiobiology, while paramedics may need to learn more about emergency management (22).

In terms of the cognition of radiation exposure effect, medical personnel in different positions showed significant differences in their grasp of the concepts of “deterministic effect, “random effect,” and “radioactive iodine accumulation organ,” The demand for knowledge of these concepts is closely related to their daily work, indicating that different positions require different scope of knowledge. As Hendee et al. (23) said, clinicians need a systematic study of radiation biology, and it is difficult to fully understand the potential harm of radiation to the human body. Clinicians, nurses, and medical technicians have a relatively good grasp of practical knowledge such as “micronucleus dose estimation” and “blood syndrome onset dose,” which may be related to their more practical duties. Managers have the highest awareness of “internal pollution damage effects,” possibly because they need to control and judge these conditions. Therefore, when medical personnel in different positions receive radiation protection training, the breadth and depth of knowledge should be customized according to their work content (10).

In terms of nuclear emergency response ability, different types of work have a distinct grasp of basic knowledge such as “radiation protection principles,” “accident classification,” and “emergency capacity requirements.” However, all types of workers generally have low awareness of specific practical aspects such as “emergency response objectives,” “primary tasks,” and “emergency exercise requirements,” This finding aligns with the research conducted by Bushberg et al. (24) and Obrador (25), who reported that medical personnel often lack practical skills training related to nuclear and radiation emergency response. In the future, it is necessary to strengthen not only basic theoretical training but also actual combat exercises to improve the rapid response and emergency response capabilities of medical personnel.

In terms of radiation medicine processing ability, the cognition level of management and nursing staff on “on-site medical management” and “hospital division of labor” was significantly higher than that of other jobs, but the cognition level of corresponding jobs on “clinical ability needs” and “surgical ability needs” was at a low level. This situation is alarming and in line with the views of Chen et al. (26), that is, medical personnel of different levels and professional backgrounds have significant differences in professional knowledge and skills and need to be taught by classification. Clinical front-line personnel also need to improve in radiation-related medical treatment knowledge, possibly due to less exposure to such knowledge in their daily work (27). Therefore, in the future, attention should be paid to cultivating interdisciplinary talents and providing more emergency drill opportunities for medical personnel.

In summary, this study reveals critical gaps in the understanding of basic radiation concepts and emergency response principles among medical personnel, particularly among front-line clinical staff and those with lower educational attainment. These findings align with established scientific theories, such as the Knowledge Gap Hypothesis and Adult Learning Theory (28, 29), which emphasize the importance of tailored educational interventions to address varying levels of prior knowledge and professional roles. The results underscore the necessity for the Nuclear Emergency Response Agency to design and implement specialized training modules that focus on fundamental radiation concepts, radiation exposure effects, and emergency response protocols. Furthermore, targeted training programs should be developed to address the distinct knowledge and skill gaps identified across different medical roles, such as clinicians, nurses, and management personnel. Additionally, interdisciplinary training in radiation biology and radiation injury first aid should be integrated into existing curricula to enhance the overall quality of nuclear emergency medical rescue. By adopting these evidence-based strategies, the preparedness and effectiveness of medical personnel in nuclear emergencies can be significantly improved.

However, this study also has some limitations. Its cross-sectional design restricts the ability to assess changes in knowledge and skills over time, and self-reported data may introduce bias, as respondents might overestimate their knowledge or abilities. Additionally, while the study sample was diverse, it may not fully represent all healthcare settings or regions, which could affect the generalization of the findings. To address these limitations, future research should consider employing longitudinal designs and conducting objective evaluations whenever feasible to enhance the reliability of the results. Expanding the sample size and including a broader range of settings will also contribute to improving the generalization of the findings.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (approval number: JD-LK2024040-I01). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

YX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YLa: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XX: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. HL: Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. JH: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. YLi: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (21BGL300), the platform open fund by the China Institute of Radiation Protection (ZFYFSHJ-2023004), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U2267220) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12405392).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Langbein, T, Weber, WA, and Eiber, M. Future of theranostics: an outlook on precision oncology in nuclear medicine. J Nucl Med. (2019) 60:13S–9S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.220566

2. Schöder, H, Erdi, YE, Larson, SM, and Yeung, HW. PET/CT: a new imaging technology in nuclear medicine. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2003) 30:1419–37. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1299-6

3. Ambrosini, V, Carrilho Vaz, S, Ahmadi Bidakhvidi, N, Chanchou, M, Cysouw, MCF, Serani, F, et al. How to attract young talent to nuclear medicine step 1: a survey conducted by the EANM oncology and Theranostics committee to understand the expectations of the next generation. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2023) 51:3–11. doi: 10.1007/s00259-023-06389-9

4. Zanzonico, P. Principles of nuclear medicine imaging: planar, SPECT, PET, multi-modality, and autoradiography systems. Radiat Res. (2012) 177:349–64. doi: 10.1667/RR2577.1

5. Hawley, L. Principles of radiotherapy. Br J Hosp Med. (2013) 74:C166–9. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2013.74.Sup11.C166

6. Marengo, M, Martin, CJ, Rubow, S, Sera, T, Amador, Z, and Torres, L. Radiation safety and accidental radiation exposures in nuclear medicine. Semin Nucl Med. (2022) 52:94–113. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2021.11.006

7. Mahesh, M, Ansari, AJ, and Mettler, FA Jr. Patient exposure from radiologic and nuclear medicine procedures in the United States and worldwide: 2009-2018. Radiology. (2023) 307:e221263. doi: 10.1148/radiol.221263. Erratum in: Radiology. 2023 Apr;307(1):e239006. doi: 10.1148/radiol.239006. Erratum in: Radiology. 2023 Jun;307(5):e239013

8. Fahey, FH, and Stabin, MG. In any use of ionizing radiation, consideration of the benefits of the exposures to possible risks is a central concern, for the physician and patient. Semin Nucl Med. (2014) 44:160–1. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2014.03.002

9. Baudin, C, Vacquier, B, Thin, G, Chenene, L, Guersen, J, Partarrieu, I, et al. Occupational exposure to ionizing radiation in medical personnel: trends during the 2009-2019 period in a multicentric study. Eur Radiol. (2023) 33:5675–84. doi: 10.1007/s00330-023-09541-z

10. Kollek, D, Welsford, M, and Wanger, K. Chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear preparedness training for emergency medical services providers. CJEM. (2009) 11:337–42. doi: 10.1017/S1481803500011386

11. Basic Standards for Protection against Ionizing Radiation and Safety of Radiation Sources (GB 18871-2002). (2002). China Institute of Nuclear Industry Standardization (CNIS).

12. Minjie, L. Investigation and study on the knowledge level and training needs of clinical nurses in nuclear emergency rescue. Nanhua University (2017).

13. Giammarile, F, Knoll, P, Kunikowska, J, Paez, D, Estrada Lobato, E, Mikhail-Lette, M, et al. Guardians of precision: advancing radiation protection, safety, and quality systems in nuclear medicine. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2024) 51:1498–505. doi: 10.1007/s00259-024-06633-w

14. Cui, S, Su, Y, Zhao, F, Xing, Z, Liang, L, Yan, J, et al. Implementation and revision of the Measures for the Management of Radiation Workers’ Occupational Health[J]. Chin. J. Radiol. Health. (2023) 32:335–40. doi: 10.13491/j.issn.1004-714X.2023.03.021

15. Waeckerle, JF, Seamans, S, Whiteside, M, Pons, PT, White, S, Burstein, JL, et al. Task force of health care and emergency services professionals on preparedness for nuclear, Biologiccal, and chemical incidents. Executive summary: developing objectives, content, and competencies for the training of emergency medical technicians, emergency physicians, and emergency nurses to care for casualties resulting from nuclear, biological, or chemical incidents. Ann Emerg Med. (2001) 37:587–601. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.115649

16. Phillips, AW, Landon, RA, Stacy, GS, Dixon, L, Magee, AL, Thomas, SD, et al. Optimizing the radiology experience through radiologist-patient interaction. Cureus. (2020) 12:e8172. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8172

17. Lin, X, and Huan, L. Meta analysis of the awareness rate of radiation protection knowledge among radiation workers in China. Occup Health. (2024) 40:2104–2107+2113. doi: 10.13329/j.cnki.zyyjk.2024.0387

18. Zhao, X, and Li, X. Comparison of standard training to virtual reality training in radiation emergency medical rescue education. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2022) 17:e197. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2022.65

19. Fu, XM, Yuan, L, and Liu, QJ. System and capability of public health response to nuclear or radiological emergencies in China. J Radiat Res. (2021) 62:744–51. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrab052

20. Alghamdi, A, Alsharari, Z, Almatari, M, Alkhalailah, M, Alamri, S, Alghamdi, A, et al. Radiation risk awareness among health care professionals: an online survey. J Radiol Nurs. (2020) 39:132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jradnu.2019.11.004

21. Kew, TY, Zahiah, M, Zulkifli, SS, Noraidatulakma, A, and Hatta, S. Doctors’ knowledge regarding radiation dose and its associated risks: cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital in Malaysia. Hong Kong J Radiol. (2012) 15:71.

22. Brenner, DJ, and Hall, EJ. Computed tomography--an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. (2007) 357:2277–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149

23. Hendee, WR, and Herman, MG. Improving patient safety in radiation oncology. Med Phys. (2011) 38:78–82. doi: 10.1118/1.3522875

24. Bushberg, JT, Kroger, LA, Hartman, MB, Leidholdt, EM Jr, Miller, KL, Derlet, R, et al. Nuclear/radiological terrorism: emergency department management of radiation casualties. J Emerg Med. (2007) 32:71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2006.05.034

25. Obrador, E, Salvador-Palmer, R, Villaescusa, JI, Gallego, E, Pellicer, B, Estrela, JM, et al. Nuclear and radiological emergencies: biological effects, countermeasures and biodosimetry. Antioxidants. (2022) 11:1098. doi: 10.3390/antiox11061098

26. Chen, JJ, Brown, AM, Garda, AE, Kim, E, McAvoy, SA, Perni, S, et al. Patient education practices and preferences of radiation oncologists and Interprofessional radiation therapy care teams: a mixed methods study exploring strategies for effective patient education delivery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2024) 119:1357–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2024.02.023

27. Smith, M, Thatcher, MD, Davidovic, F, and Chan, G. Radiation safety education and practices in urology: a review. J Endourol. (2024) 38:88–100. doi: 10.1089/end.2023.0327

28. Yoshida, Y, and Hasegawa, K. Training and education for radiological emergency preparedness: A review of current practices. Radiat Prot Dosim. (2017) 176:493–501. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncx143

Keywords: medical personnel, radiation knowledge, nuclear emergency, awareness, preparedness

Citation: Xie Y, Wang X, Lan Y, Xu X, Shi S, Yang Z, Li H, Han J and Liu Y (2025) Assessment of radiation knowledge among medical personnel in nuclear emergency preparedness: a cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health. 13:1547818. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1547818

Received: 18 December 2024; Accepted: 13 February 2025;

Published: 26 February 2025.

Edited by:

Yi Xie, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Shams A. M. Issa, Al-Azhar University, EgyptCopyright © 2025 Xie, Wang, Lan, Xu, Shi, Yang, Li, Han and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jing Han, YmJiaXNob3BAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Yulong Liu, eXVsb25nbGl1MjAwMkBzdWRhLmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

‡ORCID: Jing Han, orcid.org/0000-0003-1460-0114

Yulong Liu, orcid.org/0000-0003-2660-8076

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.