95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 01 April 2025

Sec. Infectious Diseases: Epidemiology and Prevention

Volume 13 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1470345

This article is part of the Research Topic Vaccine Education and Promotion View all 30 articles

Jia Ming Low1,2*

Jia Ming Low1,2* Erwin Jiayuan Khoo3,4

Erwin Jiayuan Khoo3,4 Meow Keong Thong5,6

Meow Keong Thong5,6 Chloe Soo1

Chloe Soo1 Anh Phuong Tran2

Anh Phuong Tran2 Le Ye Lee1,2

Le Ye Lee1,2 Fook Choe Cheah7,8

Fook Choe Cheah7,8Introduction: The rollout of successful vaccination programs during the COVID-19 pandemic has been impeded worldwide by high rates of vaccine hesitancy. We investigated vaccine hesitancy rates in Malaysia and Singapore, and explored whether these rates were associated with parents’ health beliefs.

Methods: A total of 226 Malaysian parents (MPs) and 635 Singaporean parents (SPs) participated in an online voluntary survey between November 2021 and August 2022.

Results: MPs were younger and had more children compared to SPs. SPs were more likely to have received the COVID-19 vaccine than MPs, and less likely to delay vaccinations for their children. SPs displayed greater trust in information about vaccines, their children’s doctors and healthcare authorities than MPs. Despite the similarities in ethnography and geographic proximity, the prevalence of perceived parental vaccine hesitancy was higher in Malaysia than in Singapore; this was associated with differences in healthcare beliefs.

Discussion: Beyond educational campaigns, strengthening community-based healthcare support, addressing misinformation, and fostering transparent communication from healthcare authorities may further enhance parental trust in vaccine.

Vaccine hesitancy is a worldwide but complex phenomenon listed among the top ten threats to global health by the World Health Organization in 2019 (1). The COVID-19 pandemic has further compounded the various factors contributing to vaccine hesitancy, perhaps due to heightened public attention and scrutiny of news surrounding the accelerated development and approval of COVID-19 vaccines, as well as the potential spread of misinformation on social media. When the vaccines are offered to children, parents play an important role in making informed decisions for their child’s well-being.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, both Malaysia and Singapore reported high overall national immunization rates of up to 95% (2, 3). Previous studies have reported that up to 8.0% of Malaysian parents had concerns about vaccine safety and side effects, driven by cultural and religious factors as well as misinformation (2, 4, 5). Similarly, in Singapore, localized pockets of hesitancy have been observed primarily for paediatric influenza and pneumococcal vaccines (6). This largely stemmed from the common misconception among both parents and healthcare workers that these vaccines were primarily required only when traveling overseas.

In Malaysia, COVID-19 childhood vaccination was first offered to teenagers aged 12 years and older from September 15, 2021, and subsequently to children younger than 12 years from February 3, 2022 (7). The brands of vaccines used in Malaysia were from Pfizer (61.2%), Sinovac (29.8%), AstraZeneca (7.9%), and Cansino (0.3%) (8). In Singapore, its Ministry of Health approved the use of the paediatric dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech/Comirnaty vaccine for teenagers in June 2021, and for children aged 5–11 years in December 2021. However, the uptake of the paediatric COVID-19 vaccination was significantly lower compared to the rate of adult and adolescent vaccination (9).

In facing the continuing waves of COVID-19, it is important to address the various factors contributing to vaccine hesitancy amongst parents in societies with diverse cultural and socioeconomic contexts. Malaysia and Singapore are two adjacent countries with similar diverse populations but differing economic wealth. Analyzing the results of vaccine hesitancy rates in these countries can provide valuable insights into common areas of interest, the different risk factors, and the development of solutions identified when one country performs better than the other in terms of vaccine acceptance. These findings can inform health care policies and communitarian decisions that shape appropriate public health interventions in the future.

The aim of this study was to determine and compare the healthcare beliefs among parents of eligible children for COVID-19 vaccination in Malaysia and Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also aimed to compare the social and demographic features of parents who perceived themselves as more vaccine hesitant, to determine parental trust in their healthcare systems, and to identify the preferred type of vaccine that they would have had considered for their children.

The online cross-sectional study was conducted from November 2021 to August 2022 through a secure electronic platform. A prospective, anonymous, and voluntary electronic survey modified from the previously developed “Measuring vaccine hesitancy: the development of a survey tool” was used (Supplementary Table 1), and it has been validated in a separate study (10). A translated version in Bahasa Melayu was utilized in Malaysia.

The study population consisted of parents of children who were hospitalized or attending outpatient clinics, as well as individuals who accessed the survey via links disseminated through official institutions’ social media platforms or official email channels. The study excluded parents less than 21 years of age who may not yet be eligible for the COVID-19 vaccines. Respondents did not receive any compensation for participating in the study.

The survey obtained demographic data of respondents and their children, as well as information on vaccine hesitancy, parental trust in the healthcare system, and preferred COVID-19 vaccine. Results were analyzed using chi-square analysis and multiple logistic regression analysis with Statistical Programme for Social Sciences (SPSS), IBM version 27. Statistical significance was defined when p < 0.05 in two-tailed tests.

The calculation of the sample size was based on the formula by Kish (11) for population survey using the StatCalc in EpiInfo software. With an estimated combined adult population in Malaysia and Singapore of 29,520,000 in 2022, an acceptable margin of error of 5%, an expected vaccine hesitancy prevalence of 50% (to optimize the sample size in view of the lack of previous studies for the current topic in the region) and, a design effect of 2.0 for possible clustering in the sampling, the calculated minimum sample size needed to achieve 95% confidence level was 768. The final sample size achieved was 861 – oversampling was done in anticipation of the high probability of non-response and missing data among the subjects.

The study was registered with the ethics review boards of the following institutions: Malaysia’s International Medical University (IMU) (reference no. 279/2021) and Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) (reference no. PPI/111/8/JEP-2021-824), as well as Singapore’s National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (NHG DSRB) (reference no. 2021/00900). Completion of the survey indicated participants’ consent to participate in the study.

Supplementary Table 2 (unweighted) shows the demographic data of 861 parents who participated in the study, comprising 226 (26.2%) Malaysian parents (MPs) and 635 (73.8%) Singaporean parents (SPs). Due to the much higher non-response rate of the respondents in the Malaysian population than the Singapore population, post-stratification weight was determined based on the estimated adult population percentage ratio in both countries for the year 2022 (24,700,000 and 4,820,000, respectively). Based on the calculation explained by DeBell and Kronsnick (12). The post-stratification weight for respondents from Malaysia is 3.19 (0.8367/0.2625), whereas the post-stratification weight for respondents from Singapore is 0.22 (0.1633/0.7375). Due to this adjustment, all analyses would be shown with the unweighted and weighted results for comparison. For the weighted analyses in SPSS, the complex samples procedure was used whereby the sample weight was based on the post-stratification weight and the estimation of error was based on sampling with replacement design.

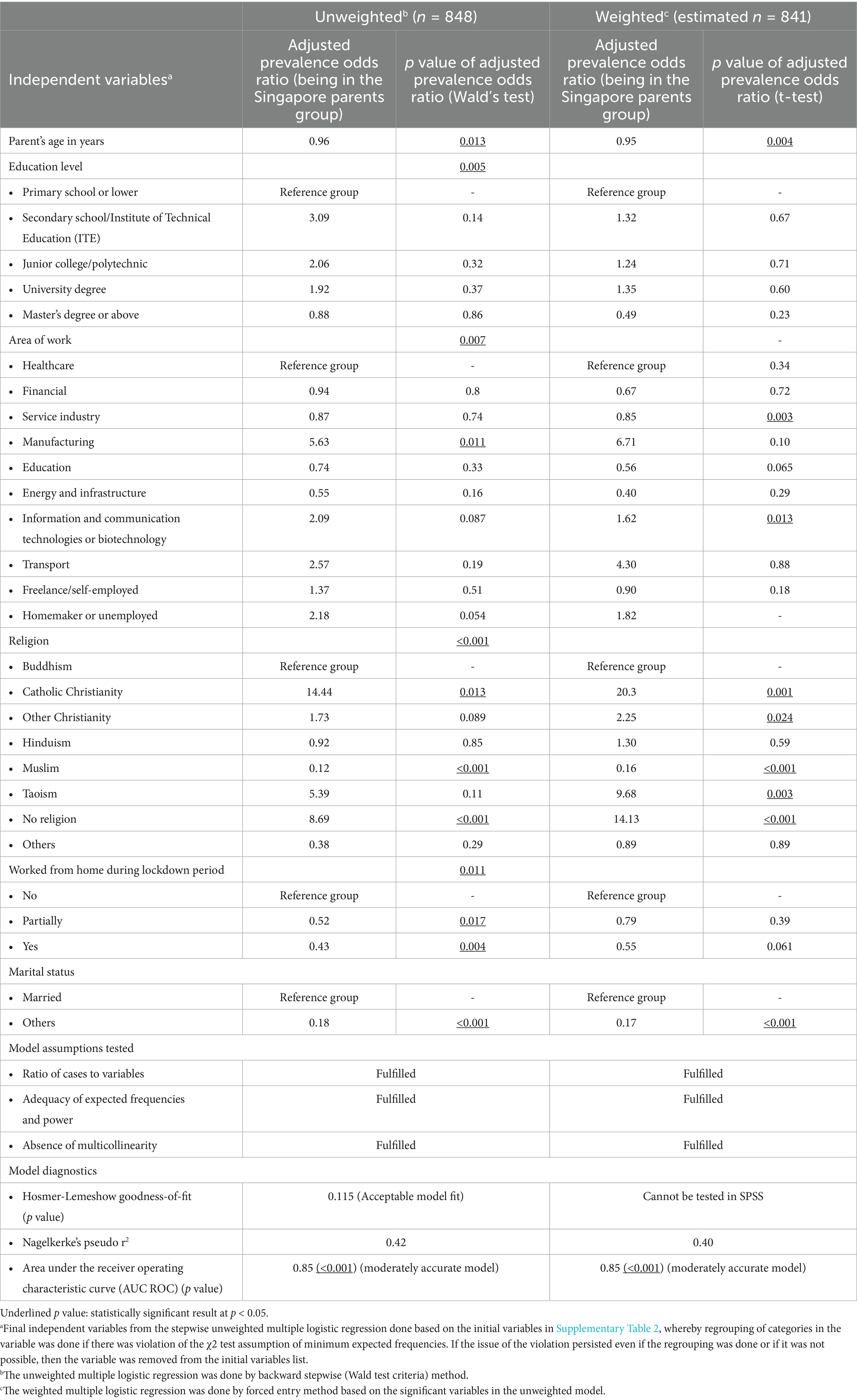

The findings show that MPs were generally younger, though the difference was not statistically significant (38.8 ± 8.8 vs. 39.1 ± 6.7 years, p = 0.64). Additionally, they had more children on average (2.4 ± 1.8 vs. 2.0 ± 0.8, p = 0.003) compared to SPs (Supplementary Table 2). There were also statistical differences noted in their educational level (p = 0.005) (Table 1), with more SPs having tertiary education than MPs (50.9% vs. 38.9%) (Supplementary Table 2). In terms of employment, more SPs were involved in the healthcare-related industries and information technologies, and were homemakers, while more MPs worked in the education sector (Supplementary Table 2; Table 1). With regards to their religious affiliations, SPs were more likely to identify themselves as Catholic, Christian, or with no religious belief, whereas MPs were more likely from the Muslim faith (Supplementary Table 2; Table 1). Comparing their marital statuses, a higher proportion of SPs were married (Supplementary Table 2; Table 1). This study found no significant difference in the proportions of parents who were able to work from home during the pandemic lockdown (Table 1).

Table 1. Multiple logistic regression analysis comparing socio-demographics of parents surveyed in Malaysia and Singapore.

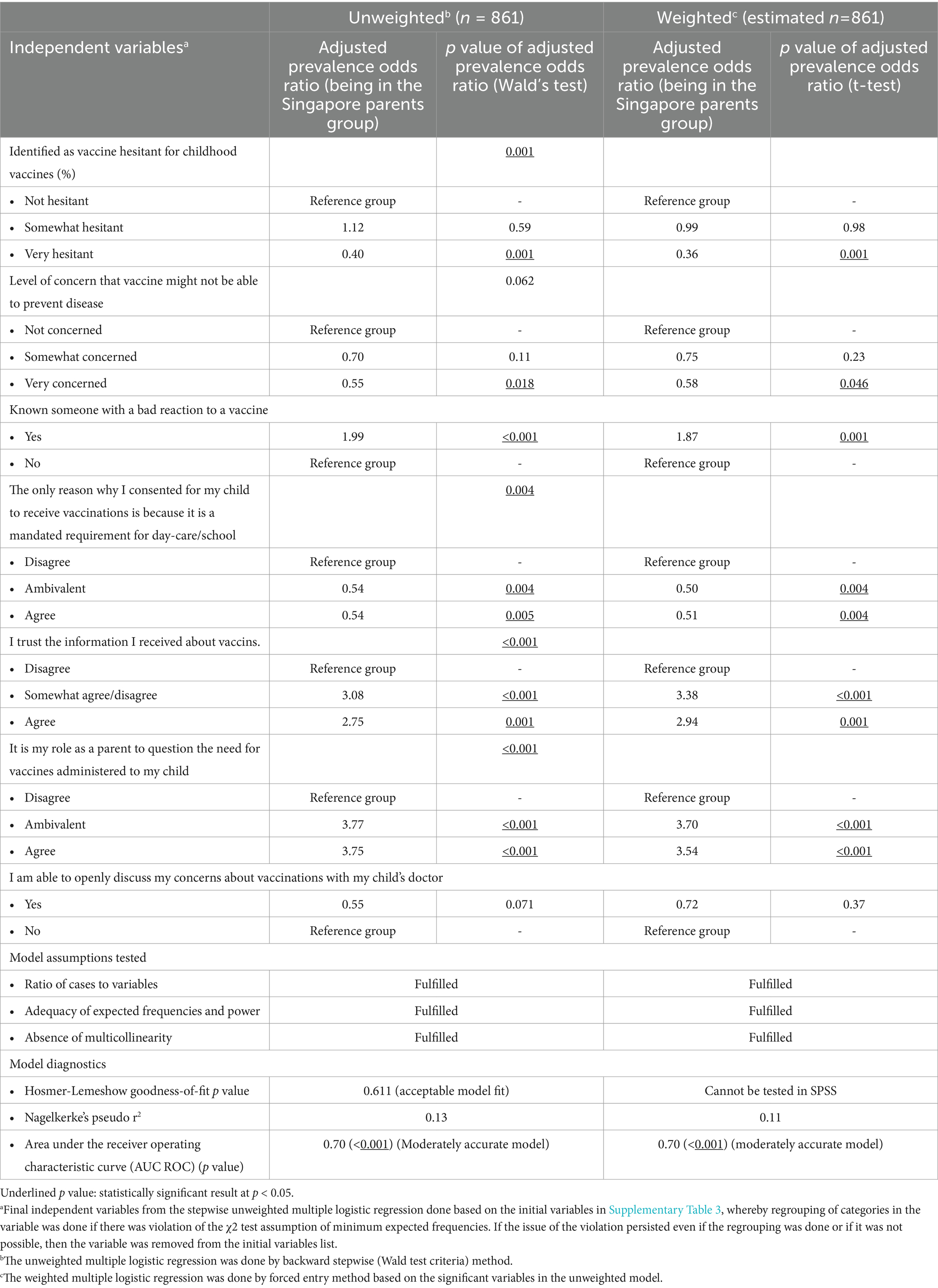

SPs were more likely to have received the COVID-19 vaccine themselves (99.1% vs. 96.5%, p = 0.013) and perceived themselves as less vaccine hesitant (5.8% vs. 16.4%, p < 0.001 for overall hesitancy categories) (Supplementary Table 2; Table 2). They were also less likely to delay vaccination for their children, although non-significant statistically (19.4% vs. 26.5%, p = 0.507 for overall delay categories), and perceived vaccine-preventable diseases as more severe (62.7% vs. 56.2%, p = 0.008 for overall perception categories) (Supplementary Table 2). More than one-third of MPs were “very concerned” that the vaccines may not actually prevent the disease (36.3% vs. 27.2%, p = 0.010 for overall “concern” categories) (Supplementary Table 2; Table 2). Of interest, perceived vaccine hesitancy was lower among SPs than MPs, although a significantly higher percentage of SPs knew of someone with a bad reaction to the vaccine (46.3% vs. 35.4%, p = 0.005) (Supplementary Table 2; Table 2).

Table 2. Multiple logistic regression analysis comparing parental views on childhood immunizations in Malaysia and Singapore.

The study also found that SPs were less likely to distrust the information that they received about vaccines (6.6% vs. 14.6%, p < 0.001 for overall “trust” categories) and were less likely to question the necessity of vaccinations for their child (5.5% vs. 12.8%, p = 0.001 for overall “agree” categories), compared to MPs (Supplementary Table 2; Table 2). However, most parents in both countries agreed that they were able to openly discuss their concerns about vaccinations with their child’s doctor. Approximately two-thirds of parents (65.5 and 65.2% in Malaysia and Singapore, respectively) agreed with the recommended childhood vaccination schedule by their government (Supplementary Table 2; Table 2).

As shown in Supplementary Table 3 (unweighted) and Table 3, 68.1% of MPs and 70.2% of SPs stated that they would give the COVID-19 vaccine to their child between 6–11 years of age (p = 0.556).

Table 3. Multiple logistic regression analysis of factors associated with vaccine hesitancy among parents in Malaysia and Singapore.

A higher proportion of parents expressed a willingness to vaccinate their teenager, with 79.2% of MPs and 82.8% of SPs indicating that they would do so (p = 0.224) (Supplementary Table 3). A significantly greater proportion of SPs than MPs expressed trust in information, advice, and recommendations regarding COVID-19 vaccination from their children’s doctors or healthcare authorities (80.8% vs. 69.9%, p = 0.005 for overall “source” categories) (Supplementary Table 3 and Table 3). Furthermore, respondents from both countries rated mRNA vaccines as the most effective in terms of preventing deaths and hospital admission compared to other types of COVID-19 vaccines (45.6% for MPs vs. 60.6% for SPs, p < 0.001 for overall vaccine categories) (Supplementary Table 3; Table 3).

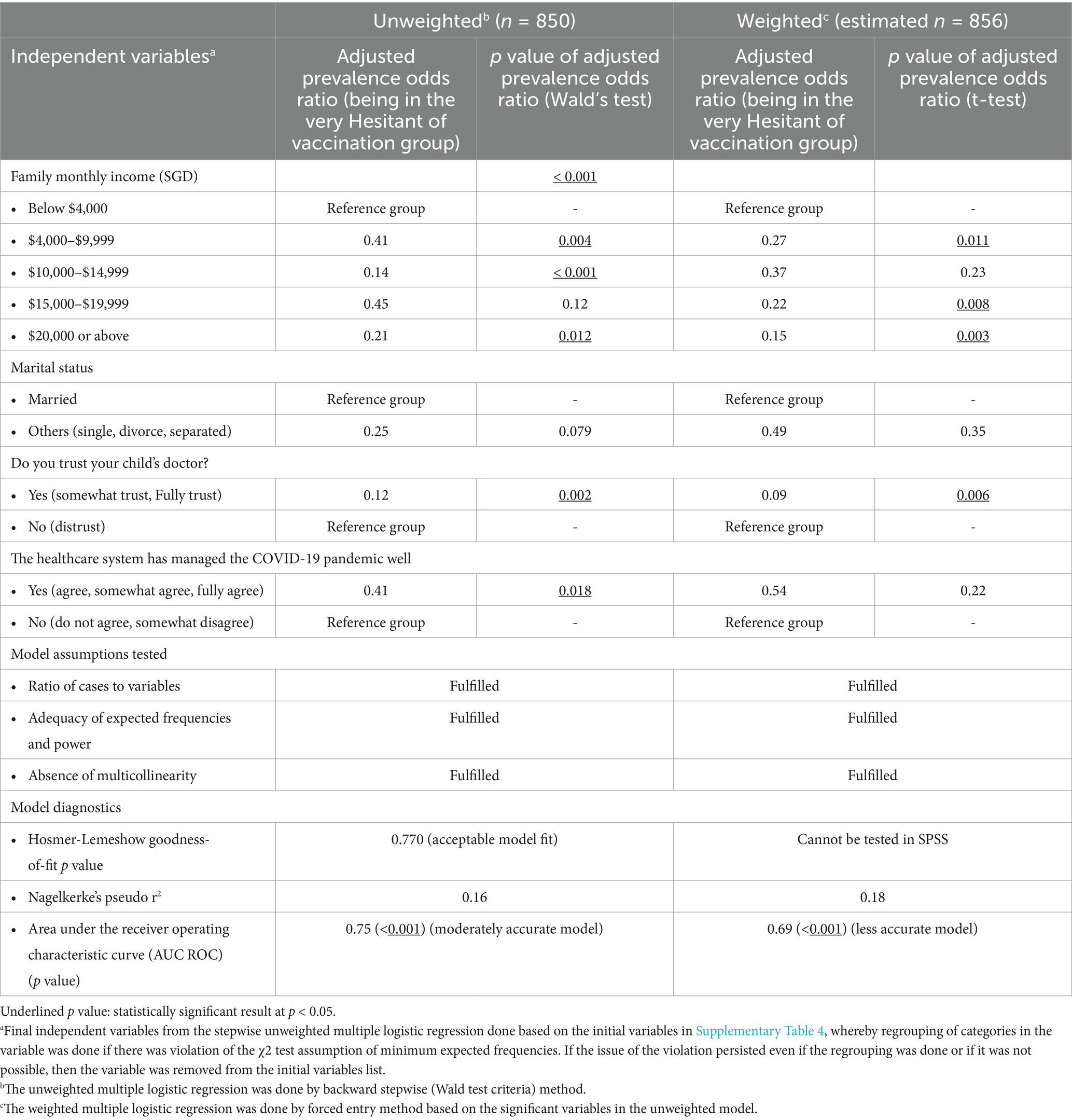

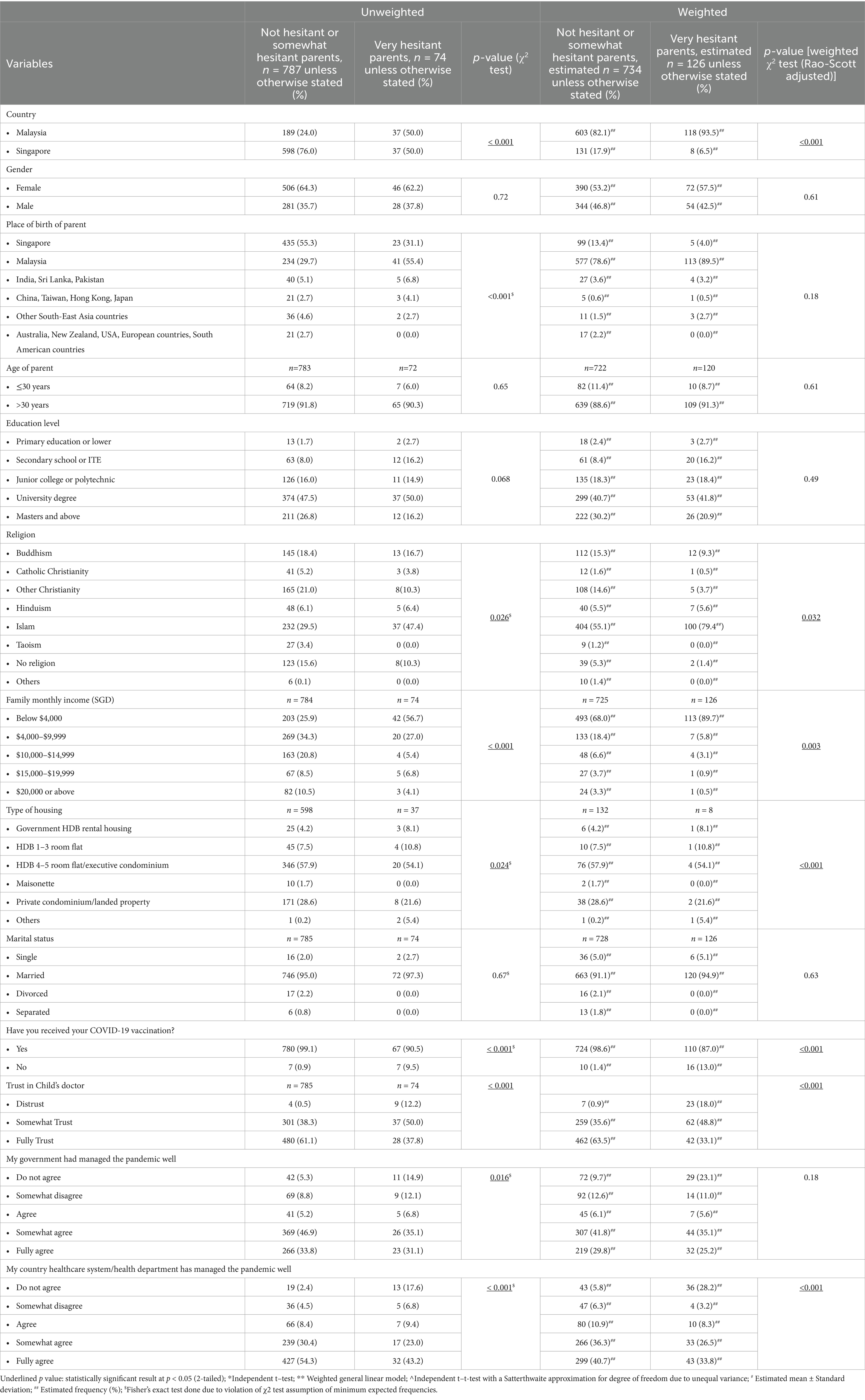

Table 4 (unweighted) shows a significantly higher proportion of perceived “very hesitant” parents in Malaysia compared to Singapore (p < 0.001). Furthermore, parents of Muslim faith exhibited a higher likelihood of perceived vaccine hesitancy compared to other religions (47.4% Muslims accounts for very hesitant group vs. 29.5% Muslims accounts for non-hesitant or somewhat hesitant group, p = 0.026 for overall religion categories). A notable association was also found between trust in the child’s doctor and vaccine hesitancy (p < 0.001), where parents who were fully trusting in their child’s doctor were less likely to be classified as “very hesitant.” Correspondingly, parents who disagreed with their government’s (p = 0.01) and healthcare system/department’s (p < 0.001) management of the pandemic were more likely to be “very hesitant” about vaccines (Table 4).

Table 4. Descriptive analyses of factors associated with perceived vaccine hesitancy among parents in Malaysia and Singapore.

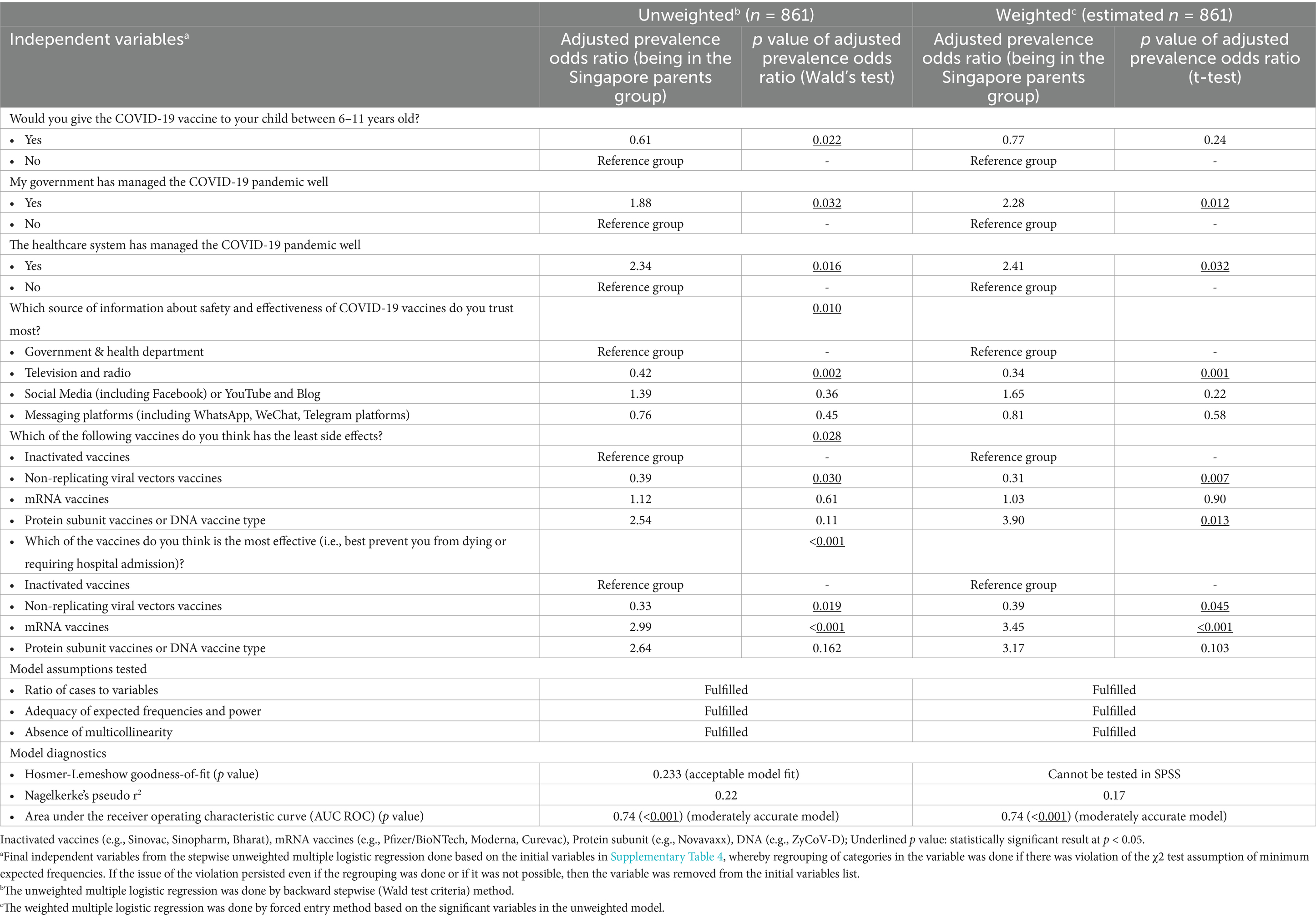

Based on the multiple logistic regression analysis (Table 5) (unweighted), vaccine hesitancy was associated with (i) the lower income group (i.e., compared to the $4,000 group, the other income groups have adjusted prevalence odds ratio below than 1); (ii) distrust of child’s doctor (i.e., those who trust their child doctor have adjusted prevalence odds ratio below than 1); and, (iii) perception that the healthcare system has not managed the COVID-19 pandemic well (i.e., those who agree that the healthcare system was successful have adjusted prevalence odds ratio below 1).

Table 5. Multiple logistic regression analysis of willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19, trust in the healthcare system and preferences for vaccine type.

This study findings suggest that there are significant differences in the COVID-19 vaccine health care beliefs among parents in the two neighboring Southeast Asian countries. Our results are aligned with other estimates from different countries in Asia where the level of parental vaccine hesitancy varies, reportedly ranging between 10.8 and 42.8% (10, 13–15).

Factors identified in our study showed that parental vaccination status, trust in their healthcare provider and system were key factors associated with differences in vaccine beliefs. These findings confirm the result of other authors. A cross-sectional nationwide survey of Malaysian parents also showed that parents’ history of COVID-19 vaccination was the strongest predictor of their willingness to vaccinate their children (7). Likewise, in Singapore, trust in the child’s doctors was rated more important than information obtained from social media despite the high media usage in the country (10).

As such, we recommend that in managing future pandemics, it is imperative for all primary health care providers to receive up to date accurate information for dissemination to the public during the clinic visits. Doing so will foster an environment of greater understanding and cooperation. It is also important that healthcare providers remain up to date and provide evidence-based reasoning with regards to vaccination strategies in the face of potential new variants.

Unsurprisingly, a critical factor undermining vaccine use was trust in healthcare systems (16). Parents might be aware of shortcomings in the healthcare systems, both currently and historically. There can also be suspicion that when financial gains are involved, it is not unreasonable for suspecting dishonesty from those producing, distributing or promoting the vaccine. This belief could potentially be influenced by profits generated from COVID-19 vaccination by the pharmaceutical companies (17). Recommendations for boosters, vaccinations in the paediatric population who have been relatively spared from the COVID-19 pandemic may have only exacerbated negative vaccine belief sentiments amongst some individuals. Furthermore, rapid changes to policy statements, masking and isolation requirements, make vaccine hesitant parents more sceptical of the need for vaccine and its reliability.

The results of this survey indicate that perceived parental vaccine hesitancy was more prevalent in Malaysia than Singapore. The surveyed MPs trust of their doctors and healthcare system did not rate as high as the SPs, with a higher proportion of the MPs themselves remained unvaccinated against COVID-19. This finding is consistent with previous research that suggests vaccine hesitancy is more common in developing countries where one of the reasons for this may be related to the level of health literacy (18). Dubov et al. identified four groups of vaccine-hesitant individuals, including the misinformed, uninformed, undecided and unconcerned (19). Identification would allow for tailored individualized interventions to each (19). For example, personal analogies may be more effective for the “misinformed” individual, while motivational interviewing may be better suited for the “undecided” cluster. The study also found that Muslim parents were more likely to be “very hesitant” towards COVID-19 vaccines than parents of other religions. This result may be attributed to the predominant Muslim faith among MPs although this finding is also consistent with another similar online cross-sectional study conducted in ten countries in Asia, Africa, and South America earlier in the pandemic (20). However, parents’ age, gender, educational level, and marital status were not significantly associated with vaccine hesitancy in this study. This contrasts with other research that reported these demographic factors to be associated with vaccine hesitancy (21, 22). A possible explanation for these results may be a preponderance of respondents from urban communities in this study.

Our findings reveal that parental vaccine hesitancy is driven by a complex interplay of parental concerns and beliefs. Apart from trust in health information and the healthcare system, the way parents perceive the severity of vaccine-preventable diseases can drive their decision making. Our results show that SPs, who are more likely to perceive these complications as severe, have lower levels of hesitancy. This may be attributed to a higher parental health literacy level in a generally more educated population. This perception may be reinforced by social norms and the influence of healthcare professionals, who strive to effectively convey the importance of vaccination.

It was also reflected in our survey that a large proportion of parents surveyed in both countries agreed with the recommended childhood vaccination schedule by their government whilst holding back on vaccinating their child against COVID-19. We speculate that some parents may view vaccinating against COVID-19 as separate and unrelated, possibly due to the novelty of the mRNA technology and the rapidity of the development. This concurs with other published literature which have also shown that vaccine beliefs are not a stable trait (23). Some may also wrongly classify the vaccine as “experimental” and may feel that they do not want to subject their child to an ongoing experiment even though monitoring of adverse events after FDA approval is a standard procedure for all pharmaceuticals (24). On the other spectrum of things and contrary to these perceptions, parents in this study rated mRNA vaccines as the “most effective” in terms of preventing deaths and hospital admission compared to other types of COVID-19 vaccines. The reason for this is not clear but it may have something to do with the efficacy data of mRNA vaccines from clinical trials and real-world studies. In contrast, 1 in 6 surveyed parent perceived inactivated and non-replicating viral vector vaccines are most effective in preventing death and hospital admission with almost 40% of the parents believed they have the least side effects. Such vaccines are used in some other developing countries for children, and perhaps by having more options available, this may increase the vaccine uptake.

To address this issue of vaccine-hesitancy, effective communication strategies that address key concerns from stakeholders are crucial. A systematic review of interventions has revealed that the most successful campaigns are those that are dialogue-based and multi-pronged (25). Healthcare policy makers should also leverage on routine childhood immunization visits at community health centres or private health facilities to engage and get the buy-in from this group of parents. Finally, infotainment products in various languages may be used as an outreach strategy to supplement these efforts and specific media campaigns can be optimized to the type of vaccine attitude amongst different individuals who might be unsure or willing (26).

Strengths of this study include a detailed comparative analysis exploring the role of healthcare beliefs on childhood vaccination uptake between two countries with similarities in ethnography and geographic proximity between these two countries. This study may provide insights in the event of future pandemics to help fill the gaps between public engagement and health care beliefs of parents when it comes to administering novel vaccines to their children in the light of a pandemic.

We acknowledge some of the limitations of this survey. Firstly, this study was static and may not capture the rapidly evolving reality in the science, understanding, disease statistics and vaccination coverage during this COVID-19 pandemic. Secondly, the rather small sample size of parents who participated, may not be entirely representative of the views of the population especially in the geographically vaster Malaysia. A larger study involving other Asian countries with diverse socioeconomic backgrounds may allow for more in depth examination of the factors that influence vaccine hesitancy, which is a global health problem. In addition, a deeper exploration of how public health initiatives shape parental attitudes towards vaccination would enhance this report. However, the aim of our study was to examine parental healthcare beliefs regarding COVID-19 vaccination. As such, our data did not include measures capturing the influence of different public health approaches. Lastly, compared to Malaysia, Singapore is characterized by a much smaller geographic area, higher per capita income, and centralized healthcare system. Thus, the vaccine supply chain may be more streamlined in Singapore, ensuring rapid and widespread access. Such robust infrastructure may have contributed to the higher levels of trust observed amongst Singaporean parents. In contrast, while Malaysia has made significant strides in its national immunization program, the country’s larger and more geographically diverse landscape may pose unique logistical challenges.

In conclusion, our study highlighted the importance of healthcare providers in promoting vaccine acceptance and addressing vaccine hesitancy, and the importance of effective communication and public health messaging in this respect. Despite the proximity of these two countries that share many ethnographic similarities, perceived parental vaccine hesitancy is more common in Malaysia than Singapore because of different healthcare beliefs. Increasing educational efforts and public health awareness campaigns may be an approach to increase parental trust to improve the uptake of COVID-19 vaccinations in the paediatric population. Future research should explore and identify effective strategies for promoting vaccine acceptance.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by International Medical University (IMU), MalaysiaUniversiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), MalaysiaNational Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board, Singapore. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

JL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CS: Writing – review & editing. AT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. FC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The Malaysian component of this survey was partially funded with an unrestricted educational grant provided to the College of Paediatrics, Academy of Medicine of Malaysia, which was disbursed to Cheah FC in UKM as project lead (FF-2021-481). Jia Ming Low received funding from the National University Health System (NUHS), Singapore, Clinician Scientist Program 2.0 (grant reference no.: NCSP2.0/2023/PVO/LJM) and the National Medical Research Council (Singapore) Research Training Fellowship (MH 095:003/008-337) to support this work.

The authors of this paper would like to thank (1) all the study participants who donated their time generously to complete the survey, (2) the doctors and nurses involved for their assistance in approaching the potential survey respondents for this study, (3) Dr. Jia Min Leong for her technical help, and (4) Ms. Sheena Nishanti Ramasamy for her assistance in formatting and submitting the manuscript. We accord our many thanks to our biostatistician, Mr. Boekhtiar Borhanuddin, Director & Chief Researcher at Boekh Statistical Solution, for his expert contribution to ensure the accuracy of the statistical computations in this paper. Finally, this paper is also dedicated to all the frontline healthcare providers who faced the pandemic in all its uncertainties and fought valiantly to protect their patients.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1470345/full#supplementary-material

1. Matos, C, Gonçalves, BA, and Couto, MT. Vaccine hesitancy in the global south: Towards a critical perspective on global health. Glob Public Health. (2022) 17:1087–98. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1912138

2. Trading Economics (2025). Malaysia – Immunization, DPT (% of Children Ages 12–23 Months). Available online at: https://tradingeconomics.com/malaysia/immunization-dpt-percent-of-children-ages-12-23-months-wb-data.html (accessed February 26, 2025).

3. Ministry of Health, Singapore (2025). Newsroom – National Childhood and Adolescent Immunisation [Parliamentary QA, 1 March 2016]. Available online at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/newsroom/national-childhood-and-adolescent-immunisation (accessed February 26, 2025).

4. Wong, LP, Wong, PF, and AbuBakar, S. Vaccine hesitancy and the resurgence of vaccine preventable diseases: the way forward for Malaysia, a Southeast Asian country. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2020) 16:1511–20. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1706935

5. Kalok, A, Loh, SYE, Chew, KT, Abdul Aziz, NH, Shah, SA, Ahmad, S, et al. Vaccine hesitancy towards childhood immunisation amongst urban pregnant mothers in Malaysia. Vaccine. (2020) 38:2183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.01.043

6. Zahari, M, Offeddu, V, Smith, GJD, and Tam, CC. Determinants of influenza and pneumococcal vaccine uptake among preschool children in Singapore. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0285561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0285561

7. Ng, DLC, Gan, GG, Chai, CS, Anuar, NAB, Sindeh, W, Chua, WJ, et al. The willingness of parents to vaccinate their children younger than 12 years against COVID-19: a cross-sectional study in Malaysia. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:1265. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13682-z

8. COVIDNOW (2022). Vaccinations in Malaysia. Available online at: https://covidnow.moh.gov.my/vaccinations/ (accessed February 26, 2025).

9. Ministry of Health, Singapore (2025). Newsroom – Expert Committee on COVID-19 vaccination recommends using the paediatric dose Pfizer-BioNTech/Comirnaty vaccine for children aged 5–11 years and extending booster vaccination to persons aged under 30 years [Press Releases, 10 December 2021]. Available online at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/expert-committee-on-covid-19-vaccination-recommends-using-the-paediatric-dose-pfizer-biontech-comirnaty-vaccine-for-children-aged-5-11-years-and-extending-booster-vaccination-to-persons-aged-under-30-years (accessed March 27, 2023).

10. Low, JM, Soo, CWT, Phuong, T, Zhong, Y, and Lee, LY. Predicting vaccine hesitancy among parents towards COVID-19 vaccination for their children in Singapore. Front Pediatr. (2022) 10:994675. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.994675

12. DeBell, M, and Krosnick, JA. Computing weights for American national election study survey data. Ann Arbor, MI, and Palo Alto, CA: American National Election Studies (2009). ANES Technical Report series, no. nes012427).

13. Ali, M, Ahmed, S, Bonna, AS, Sarkar, AS, Islam, MA, Urmi, TA, et al. Parental coronavirus disease vaccine hesitancy for children in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. F1000Res. (2022) 11:90. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.76181.2

14. Kuan, CI. Vaccine hesitancy and emerging parental norms: A qualitative study in Taiwan. Sociol Health Illn. (2022) 44:692–709. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.13446

15. Huynh, G, Nguyen, HTN, Van Tran, K, An, PL, and Tran, TD. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Postgrad Med. (2022) 134:303–8. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2022.2044142

16. Schmelz, K, and Bowles, S. Overcoming COVID-19 vaccination resistance when alternative policies affect the dynamics of conformism, social norms, and crowding out. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2021) 118:e2104912118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2104912118

17. Lee, J (2022). Pfizer expects a record $100 billion in revenue this year, thanks to COVID-19 vaccines and treatments (Market Watch). Available online at: https://www.marketwatch.com/story/pfizer-expects-a-record-100-billion-in-revenue-this-year-thanks-to-covid-vaccines-and-treatments-11644356651 (accessed March 27, 2023).

18. Jaafar, N, Perialathan, K, Krishnan, M, Juatan, N, Ahmad, M, Mien, TYS, et al. Malaysian Health Literacy: Scorecard Performance from a National Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:5813. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115813

19. Dubov, A, Distelberg, BJ, Abdul-Mutakabbir, JC, Beeson, WL, Loo, LK, Montgomery, SB, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers in Southern California: Not Just "Anti" vs. "Pro" Vaccine. Vaccines (Basel). (2021) 9:1428. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9121428

20. Harapan, H, Anwar, S, Yufika, A, Sharun, K, Gachabayov, M, Fahriani, M, et al. Vaccine hesitancy among communities in ten countries in Asia, Africa, and South America during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pathogens Glob Health. (2021) 116:236–43. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2021.2011580

21. Khatatbeh, M, Albalas, S, Khatatbeh, H, Momani, W, Melhem, O, Omari, OA, et al. Children's rates of COVID-19 vaccination as reported by parents, vaccine hesitancy, and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among children: a multi-country study from the Eastern Mediterranean Region. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:1375. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13798-2

22. Limbu, YB, Gautam, RK, and Pham, L. The Health Belief Model Applied to COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: A Systematic Review. Vaccines (Basel). (2022) 10:973. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10060973

23. Siegler, AJ, Luisi, N, Hall, EW, Bradley, H, Sanchez, T, Lopman, BA, et al. Trajectory of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Over Time and Association of Initial Vaccine Hesitancy With Subsequent Vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e2126882. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.26882

24. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) Office of the Federal Register (OFR) (2023). Code of Federal Regulations. Available online at: https://bookstore.gpo.gov/products/code-federal-regulations-2023 (accessed March 27, 2023).

25. Jarrett, C, Wilson, R, O'Leary, M, Eckersberger, E, and Larson, HJSAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy—A systematic review. Vaccine. (2015) 33:4180–90. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.040

Keywords: COVID-19, health beliefs, paediatric vaccines, trust, vaccine hesitancy

Citation: Low JM, Khoo EJ, Thong MK, Soo C, Tran AP, Lee LY and Cheah FC (2025) Comparative analysis of the role of healthcare beliefs on childhood vaccination uptake among parents in Malaysia and Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health. 13:1470345. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1470345

Received: 30 July 2024; Accepted: 10 March 2025;

Published: 01 April 2025.

Edited by:

Graça S. Carvalho, University of Minho, PortugalReviewed by:

Dumilah Ayuningtyas, University of Indonesia, IndonesiaCopyright © 2025 Low, Khoo, Thong, Soo, Tran, Lee and Cheah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jia Ming Low, cGFlbGptQG51cy5lZHUuc2c=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.