94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Public Health, 19 February 2025

Sec. Public Health Policy

Volume 13 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1464370

This article is part of the Research TopicWorld Health Day 2024: Frontiers in Public Health presents: "My Health, My Right"View all 12 articles

Wiebe Külper-Schiek1*

Wiebe Külper-Schiek1* Liudmila Mosina2

Liudmila Mosina2 Lisa A. Jacques-Carroll2

Lisa A. Jacques-Carroll2 Annika Falman1

Annika Falman1 Thomas Harder1

Thomas Harder1 Eduard Kakarriqi3

Eduard Kakarriqi3 Iria Preza4

Iria Preza4 Arman Badalyan5

Arman Badalyan5 Gayane Sahakyan6

Gayane Sahakyan6 Oxana Romanova7

Oxana Romanova7 Veronika Shimanovich8

Veronika Shimanovich8 Sanjin Musa9

Sanjin Musa9 Dinagul Bayesheva10

Dinagul Bayesheva10 Nurshay Azimbayeva11

Nurshay Azimbayeva11 Zuridin Nurmatov12

Zuridin Nurmatov12 Vera Toigombaeva13

Vera Toigombaeva13 Ninel Revenco14

Ninel Revenco14 Veaceslav Gutu15

Veaceslav Gutu15 Ljiljana Markovic-Denic16

Ljiljana Markovic-Denic16 Branka Bonaci-Nikolic16,17

Branka Bonaci-Nikolic16,17 Dilorom Tursunova18

Dilorom Tursunova18 Nigora Tadzhiyeva19

Nigora Tadzhiyeva19 Ole Wichmann1

Ole Wichmann1 Siddhartha Sankar Datta2

Siddhartha Sankar Datta2Introduction: A National Immunization Technical Advisory Group (NITAG) provides independent guidance to Ministries of Health (MoH) and policymakers, enabling them to make informed decisions on national immunization policies and practices. As of 2022, 50 of the 53 countries in the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region (the Region) had established a NITAG, with 58% of all NITAGs and 66% of those in middle-income countries (MICs) in the Region meeting all six WHO process indicators of NITAG functionality. However, many newly established NITAGs in MICs in the Region experience challenges in terms of their functioning, structure, and outputs.

Methods: To address these challenges and achieve the goal of evidence-informed decision making on immunizations, the WHO Regional Office for Europe and the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) implemented a project to strengthen the functioning of MIC NITAGs of the Region through comprehensive evaluations of nine NITAGs and development and implementation of improvement plans.

Results: All evaluated NITAGs are formally established and complete the most important aspects of NITAG functioning. The main challenge for all NITAGs is the lack of a well-staffed Secretariat to establish annual workplans and develop NITAG recommendations following a standardized process.

Discussion: The evaluation identified NITAGs' strengths and challenges. Some challenges have been addressed through improvement plan implementation. WHO and RKI will continue to evaluate NITAGs and support development and implementation of improvement plans. WHO and NITAG partners will continue to provide training on the standardized recommendation-making process and advocate increased MoH support to NITAGs, including dedicated Secretariat staff.

A National Immunization Technical Advisory Group (NITAG) is composed of multi-disciplinary experts who provide scientific evidence and support to Ministries of Health (MoH) and governments in making evidence-informed decisions related to immunization policies and practices (1, 2). The NITAG's role is to strengthen country ownership and public confidence in the national immunization programme by developing national recommendations that are based on the best available evidence using a transparent and systematic process to increase the credibility of MoH or government decisions and build the resilience of National Immunization Programmes (NIPs) (3, 4). In recent years, many low and middle-income countries (LMICs) have followed the lead of high-income countries by establishing NITAGs; the Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011–2020 called on all countries to establish or have access to a NITAG by 2020 (5).

As of 2022, 50 out of 53 countries in the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region (the Region), including all 18 MICs, reported having a NITAG in place through the WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form (JRF) (6). However, performance varies widely; in 2022, 58% of all NITAGs and 66% of NITAGs in MICs reported meeting all six process indicators of NITAG functionality. The main challenges in meeting the six indicators were in collecting a declaration of interest from all NITAG members, a lack of data on the number of meetings in the reporting year, and insufficient representation of the five required disciplines by NITAG members.

Evaluating NITAGs' structure, functioning and work processes helps NITAGs identify areas for improvement. Such evaluations have been conducted in the past by WHO and NITAG partners (e.g., the Supporting Independent Immunization and Vaccine Advisory Committees [SIVAC] initiative that conducted evaluations of the NITAG of Armenia in 2015, and of the NITAG of the Republic of Moldova in 2016) (7–11). Evaluation reports were provided to the team by the NITAGs. Additionally, in 2016, WHO conducted a survey to evaluate NITAGs from MICs. This survey revealed that the composition and function of some NITAGs were still not in line with WHO recommendations and most NITAGs of MICs did not have a systematic recommendation-making process.

Based on the findings from the SIVAC evaluations and the WHO survey, NITAG strengthening activities implemented in the Region from 2017 to 2019 focused on increasing NITAGs' functionality and capacity to develop systematic evidence-based recommendations (8). The Evidence to Recommendation (EtR) process is used by many long-functioning NITAGs such as the United States Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), Germany's Standing Committee on Vaccination (STIKO), and WHO's Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) and includes a process of systematic collection, quality-assessment, and synthesis of evidence, which allows for transparent communication of the evidence that leads to a recommendation (12–14). To assess the status of NITAG functionality in the Region after the implementation of strengthening activities and to gain an understanding of the remaining challenges, the Regional Office and Robert Koch Institute (RKI) initiated a joint project in 2020, the EURO NITAGs Project,1 with financial support from the German MoH. The project aims to conduct in-depth evaluations of NITAGs in 16 MICs in the Region, support NITAGs in developing and implementing improvement plans to address identified challenges and increase NITAGs' capacity to develop evidence-informed immunization policy recommendations.

This article outlines the project support provided, the evaluation process, and a concise summary of major evaluation results.

The evaluations were conducted using a detailed Evaluation Tool for NITAGs (15) (referred to hereafter as “the questionnaire”) developed specifically for this project. The questionnaire was developed by reviewing the structure, questions and answer options of existing evaluation tools (e.g., SIVAC evaluation tool, WHO NITAG Simplified Evaluation Tool) (16, 17). While the structure of the questionnaire is in line with those of existing tools, we rephrased, combined and added more detailed questions on specific aspects to allow the study team to get an in-depth understanding of the functioning of the MIC-NITAGs in the Region and identify specific strengths and challenges. The questionnaire includes questions covering three evaluation areas: (1) NITAG functionality, which includes the formal establishment of the NITAG, its membership and composition, available resources, funding, and independence; (2) Quality and results of the NITAG's work processes including the preparation and conduct of meetings, and the recommendation-making process; and (3) NITAG's integration into decision-making processes, including collaboration between the NITAG and MoH and other immunization stakeholders and the NITAG's public visibility. NITAGs complete the questionnaire, self-assess their performance in each area, and summarize their main strengths and challenges. To ensure clarity of the questions and usability of the tool, the questionnaire was piloted in two countries (in-country evaluation in Belarus and self-evaluation in Albania) and revised based on the countries' feedback.

The final version of the questionnaire is published on the Regional Office website and includes an instruction guide and NITAG improvement plan template (15).

The NITAG evaluations are conducted in four phases. During phase 1, the project team (Regional Office and RKI) conducts a briefing on the evaluation process with the NITAG Chair and Secretariat, obtain the NITAG's commitment to conduct the evaluation, and collect relevant documents such as meeting minutes, terms of reference (ToR), standard operating procedures (SOPs), and recently developed recommendations. During phase 2, the NITAG completes the questionnaire independently (self-evaluation) or with the project team's support (external evaluation). In phase 3, the project team reviews the completed questionnaire and relevant documents. Any unclear or inconsistent information from the questionnaire or shared documents is discussed with the NITAG Secretariat and/or Chair and misunderstandings of terminology and concepts are explained and clarified. Based on this discussion, the project team develops a detailed report for each NITAG including strengths and challenges identified by both parties and recommendations to overcome identified challenges. During phase 4, the NITAG, with the project team's support, develops an improvement plan based on the recommendations, including interventions and detailed activities for each area of improvement, persons responsible for each activity, NITAG partners to be involved, and an implementation timeframe.

Between 2020 and 2023, the project team conducted evaluations of nine NITAGs including Albania, Armenia, Belarus, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnia and Herzegovina), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, the Republic of Moldova, Serbia, and Uzbekistan. Evaluations of the remaining seven MIC NITAGs are scheduled for 2024–2025.

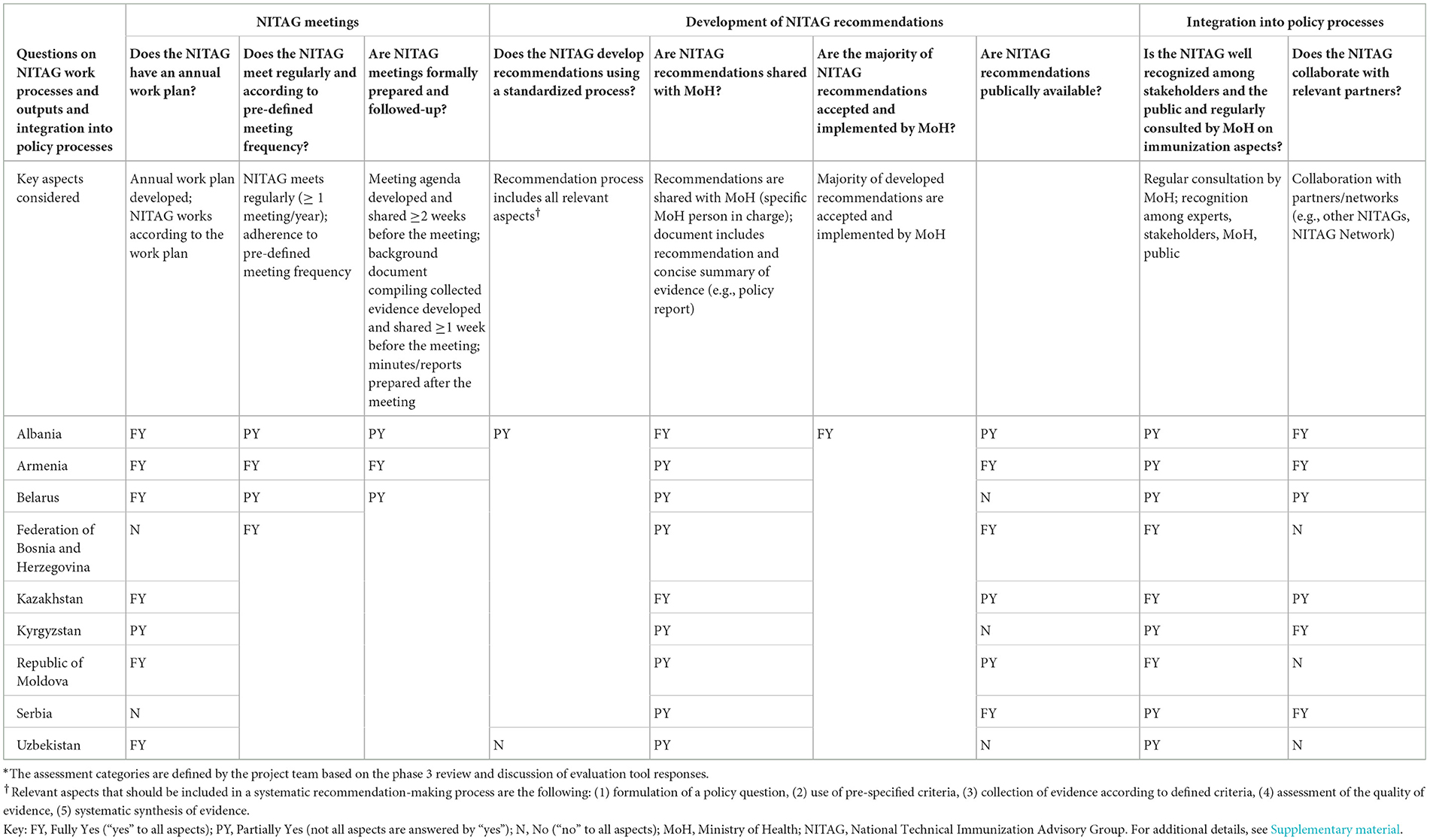

In the following section, the major results of the NITAG evaluations are presented. For the tabular presentation, the questions and sub-questions from the questionnaire were summarized and re-structured to provide overarching evaluation questions. Three assessment categories (fully yes, partially yes, and no) describe the NITAGs' functionality (Table 1), work processes, outputs, and integration into the policy process (Table 2) and are linked to the questions and key aspects indicated in the tables. Further details on the NITAG assessments are available as Supplementary material.

Table 2. Description of the work processes, outputs, and integration into the policy process of the evaluated NITAGs.*

All NITAGs were formally established as an advisory body through a MoH order. Most of the NITAGs (n = 7) have a document (e.g., ToR) that describes their functioning, however, two out of the seven do not address all relevant aspects that define the functioning of NITAGs in the ToR (see key aspects considered in Table 1).

All NITAGs have core members representing experts from various disciplines to decide on final NITAG recommendations. However, three NITAGs include core members who work for the MoH or NIP and therefore are not independent experts. All NITAGs have an appointed Chair and, except for one NITAG, the role of the Chair is defined in the NITAG's ToR. All NITAGs have a Secretariat in place to provide technical support to the NITAG. However, none of the evaluated NITAG Secretariats are considered “fully functional” (see key aspects considered in Table 1). The major challenge is the absence of dedicated Secretariat staff who can provide technical support to the NITAG. For most NITAGs, National Public Health Institute (NPHI) officers or NIP staff conduct Secretariat work in addition to their routine responsibilities. For two NITAGs, the Secretary also serves as the NITAG Chair (Bosnia and Herzegovina) or as a core NITAG member (Republic of Moldova)2. Five NITAGs have established working groups (WGs) to prepare specific topics for NITAG discussions while only three of these have developed a WG ToR. Three NITAGs have not established WGs due to resource constraints (human and time) or a lack of experts willing to serve in WGs.

Only one NITAG had secured sustainable funding to cover expenses for NITAG meetings including per diem for NITAG members.

Only one NITAG requests core members to declare their interests in writing and assesses declared interests externally (e.g., the NITAG Chair or Secretariat determines whether the declared interest could have any influence on the discussion topic), and has a pre-defined process for managing existing or perceived conflicts of interest (CoIs). Kyrgyzstan's NITAG includes all aspects in their ToR, but not all are implemented. Six NITAGs have a CoI policy that is either based on only oral declarations, or self-assessments of existing conflicts or does not pre-define how to manage identified conflicts. Two NITAGs have no CoI policy.

All but one NITAG aligns the discussion topics with the goals and targets of the NIP. Seven NITAGs develop an annual work plan that prioritizes topics throughout the year. The remaining NITAGs do not have an annual plan but define topics before meetings. All NITAGs meet regularly and provide background materials to members before the meeting. However, only one NITAG prepares background documents with a concise summary of the collected evidence, facilitating focused and effective deliberations. All NITAGs submit meeting minutes or reports to their MoHs.

Seven out of nine NITAGs have a pre-defined process to develop recommendations. However, none of the evaluated NITAGs implement all aspects of the EtR process (see explanation in Table 2) in their recommendation-making mechanisms. Most NITAGs do not develop structured policy questions, assess the quality of the collected evidence, and/or systematically synthesize the collected evidence. Reasons for not applying a systematic process were diverse, including a lack of human resources and time to conduct such a process or a lack of awareness of the importance of the process. NITAG recommendations are shared with the MoH mainly in the form of meeting minutes. A separate document (e.g., policy brief) that includes a concise summary of the evidence resulting in the NITAG recommendations is developed only by Kyrgyzstan's NITAG.

The main strength identified was that all NITAGs had developed recommendations that MoHs accepted and the majority of the recommendations were implemented. NITAG recommendations have led to the introduction of new lifesaving vaccines and the reduction of immunization inequities in the Region. Such recommendations included human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine introduction and national strategies for COVID-19 vaccination, some of which have also been published (9, 18, 19). Two NITAGs indicated that some of their recommendations were not implemented, but the MoH did not always communicate the reasons to the NITAG. NITAG recommendations are only publicly available in three countries. In Albania and the Republic of Moldova, recommendations are published upon the MoH's decision. In Albania and Kazakhstan, interested bodies can access recommendations upon request.

All NITAGs are recognized by national stakeholders, but two NITAGs indicated a lack of public recognition. Three NITAGs do not regularly consult with other NITAGs or participate in NITAG Networks (e.g., Global NITAG Network), whereas two NITAGs have interacted directly with other NITAGs.

With the project team's support, six of the evaluated NITAGs have developed improvement plans based on the provided recommendations. The improvement plans included revising the NITAGs' ToR to include important aspects of NITAG functioning, adapting the ToR to reflect current NITAG practices, or developing an SOP. In the remaining three countries, developing improvement plans were delayed due to capacity limitations; however, the project team continues working with the remaining three NITAGs to develop and implement improvement plans.

The project team supported the implementation of the NITAG improvement plans by developing specific tools and templates for NITAGs. To support NITAGs in implementing a systematic approach for evidence-based recommendation-making, guidance on an adapted EtR process for NITAGs was developed that acknowledged the human resource constraints within the Secretariats (20). In 2022 and 2023, hands-on NITAG training was conducted with the NITAGs of Armenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Republic of Moldova, Serbia, and Uzbekistan to apply the adapted EtR process to a specific policy question during periodic webinars with the NITAG WGs targeting each step of the process, resulting in a systematically developed vaccination recommendation.

The Regional Office has published a NITAG ToR template (21) and a WG ToR template will be published soon.

The evaluations allowed NITAGs to review their composition, functioning, and quality of work outputs. Areas for further improvement were identified and reasons for existing challenges were revealed. The evaluations allowed the Regional Office and NITAG partners in the Region to gain an in-depth understanding of the NITAGs' functioning and challenges to tailor support activities to the NITAGs' needs. When we compared the current results with those from previous evaluations conducted in MICs (e.g., SIVAC evaluation), we found that the majority of challenges identified in the past (e.g., lack of a comprehensive SOP, CoI policy, standardized recommendation framework, annual work plan, use of working groups) persist and have not been completely resolved in recent years. This reveals the importance of developing improvement plans based on the evaluation findings and stringent follow-up and support of NITAGs to allow for their implementation.

The development of NITAG improvement plans, informed by evaluation findings and recommendations, along with partners' support in their implementation, has significantly contributed to strengthening the evaluated NITAGs. NITAGs enhanced their composition and functioning by developing or revising NITAG charters and ToRs to align them with best practices and WHO recommendations. After participating in EtR training sessions, NITAGs improved and standardized their recommendation-making process by integrating the EtR process into their routine practice, ensuring that their scientific advice is based on the best available evidence.

Strengthening NITAGs' capacity through evaluation and the implementation of improvement plans plays an important role in promoting equitable vaccine access. By enhancing NITAGs, we ensure that they provide robust evidence-based recommendations that lead to more informed decision-making by MoHs on introducing new vaccines, thereby contributing to equal access to life-saving vaccines in all countries. Improved NITAG capacity helps to thoroughly consider and address potential barriers to equitable access to recommended interventions, ensuring that all population groups have equal access to life-saving vaccines. Furthermore, well-functioning NITAGs increase the credibility and public trust in MoH decisions, which is essential for increasing vaccine acceptance and uptake. These efforts also contribute to achieving the European Immunization Agenda 2030′s goal of increasing equitable access to new and existing vaccines for everyone (22). By ensuring that all countries have the capacity to make informed, evidence-based decisions about immunization, we move closer to achieving universal vaccine coverage and protecting public health on a global scale. NITAGs reported that conducting self-evaluations and implementing improvement plans required significant time and human resources, delaying the project's implementation. In the future, the project team should make greater efforts to motivate and incentivize NITAGs to participate in the evaluations. Sharing experiences and best practices between NITAGs regarding previous evaluations and improvement plans may be instrumental in overcoming this challenge.

A major challenge in implementing NITAG improvement plans and applying a systematic approach to the routine NITAG decision-making process was the lack of dedicated Secretariat staff. Personnel from NPHIs or NIPs, who serve as Secretariat for all evaluated NITAGs, have limited capacity because they manage Secretariat responsibilities alongside their primary job duties. WHO and NITAG partners should continue to advocate to MoHs for increased support of NITAGs, including financial support, to enable the provision of dedicated staff to serve as the Secretariat.

The Regional Office and RKI plan to conduct evaluations of the remaining seven MIC NITAGs in the Region and execute their improvement plans in 2024–2025. Based on the team's experience, it's important to have continuous follow-ups with NITAGs on the evaluation and the development and implementation of improvement plans. The experiences learned from countries that have already implemented improvement plans as well as the resources developed in the past years will make the development and implementation of future country plans easier. Additional training sessions on the adapted EtR process will be conducted and the training format will be adapted based on the results of a planned evaluation. NITAG evaluations will be repeated post-implementation to assess progress and identify areas requiring further enhancement.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

WK-S: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Writing – original draft. LM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. LJ-C: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. AF: Writing – review & editing. TH: Writing – review & editing. EK: Writing – review & editing. IP: Writing – review & editing. AB: Writing – review & editing. GS: Writing – review & editing. OR: Writing – review & editing. VS: Writing – review & editing. SM: Writing – review & editing. DB: Writing – review & editing. NA: Writing – review & editing. ZN: Writing – review & editing. VT: Writing – review & editing. NR: Writing – review & editing. VG: Writing – review & editing. LM-D: Writing – review & editing. BB-N: Writing – review & editing. DT: Writing – review & editing. NT: Writing – review & editing. OW: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SD: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Health through the Global Health Protection Program (Grant number: ZMVI-2519-GHP713).

The authors would like to acknowledge Silvia Bino, Lyudmila Niazyan, Svetlana Grigoryan, Oleg Doubovik, Elena Samoilovich, Palo Mirza, Kanat Sukhanberdiyev, Ainagul Kuatbaevy, Lena Kasabekova, Gulnara Zhumagulova, Zhanara Bekenova, Dumitru Capmari, Marko Pavlovic, Dusan Popadic, Miljan Rancic, Renat Latipov, and Anna Loenenbach for their contributions to this project.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1464370/full#supplementary-material

1. ^In 2023, the EURO NITAGs Project continued within the SENSE-project (Strengthening National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups and their Evidence-based Decision-making in the WHO European Region and globally; https://ghpp.de/en/projects/sense/).

2. ^As the aim of a Secretariat is to provide technical support to the NITAG by collecting and synthesizing evidence for NITAG recommendations, Secretariat staff is not fully independent and should not be involved in the NITAGs discussions and/or final NITAG recommendation-making.

1. Duclos P. National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs): Guidance for their establishment and strengthening. Vaccine. (2010) 28:A18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.027

2. World Health Organization. Guidance for the development of evidence-based vaccination-related recommendations. In: Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization. Geneva: World Health Organization (2017).

3. Bell S, Blanchard L, Walls H, Mounier-Jack S, Howard N. Value and effectiveness of National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative study of global and national perspectives. Health Policy Plan. (2019) 34:271–81. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czz027

4. Howard N, Bell S, Walls H, Blanchard L, Brenzel L, Jit M, et al. The need for sustainability and alignment of future support for National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs) in low and middle-income countries. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2018) 14:1539–41. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1444321

5. World Health Organization. Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011-2020. (2013). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-vaccine-action-plan-2011-2020 (accessed December 19, 2024).

6. World Health Organization. WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form on Immunization (JRF). (2024). Available at: https://immunizationdata.who.int (accessed June 4, 2024).

7. Senouci K, Blau J, Nyambat B, Coumba Faye P, Gautier L, Da Silva A, et al. The Supporting Independent Immunization and Vaccine Advisory Committees (SIVAC) initiative: a country-driven, multi-partner program to support evidence-based decision making. Vaccine. (2010) 28 Suppl 1:A26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.028

8. Mosina L, Sankar Datta S, Shefer A, Cavallaro KF, Henaff L, Steffen CA, et al. Building immunization decision-making capacity within the World Health Organization European Region. Vaccine. (2020) 38:5109–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.05.077

9. Mosina L, Külper-Schiek W, Jacques-Carroll L, Earnshaw A, Harder T, Martinón-Torres F, et al. Supporting National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups in the WHO European Region in developing national COVID-19 vaccination recommendations through online communication platform. Vaccine. (2021) 39:6595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.034

10. Adjagba A, Senouci K, Biellik R, Batmunkh N, Faye PC, Durupt A, et al. Supporting countries in establishing and strengthening NITAGs: lessons learned from 5 years of the SIVAC initiative. Vaccine. (2015) 33:588–95. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.12.026

11. Howard N, Walls H, Bell S, Mounier-Jack S. The role of National Immunisation Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs) in strengthening national vaccine decision-making: a comparative case study of Armenia, Ghana, Indonesia Nigeria, Senegal and Uganda. Vaccine. (2018) 36:5536–43. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.07.063

12. Lee G, Carr W. ACIP evidence-based recommendations work group. updated framework for development of evidence-based recommendations by the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2012) 67:45. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6745a4

13. STIKO. Standard Operating Procedure of the German Standing Committee on Vaccinations (STIKO) for the Systematic Development of Vaccination Recommendations, Version 3.1. (2018). Available at: https://www.rki.de/EN/Content/infections/Vaccination/methodology/SOP.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed June 17, 2024).

14. World Health Organization. Development of WHO Immunization Policy and Strategic Guidance: Methods and Processes Applied by the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) to Develop Evidence-Based Recommendations. (2024). Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376622/9789240090729-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed June 17, 2024).

15. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Self-evaluation Tool for National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups. (2024). Available at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/376139?locale-attribute=en& (accessed March 4, 2024).

16. World Health Organization. NITAG Simplified Evaluation Tool. (2018). Available at: https://www.nitag-resource.org/node/79661 (accessed October 22, 2023).

17. Supporting Independent Immunization and Vaccine Advisory Committees Initiative. Comprehensive NITAG Evaluation Tool. (2017). Available at: https://www.nitag-resource.org/media-center/comprehensive-evaluation-tool (accessed October 22, 2023).

18. Markovic-Denic L, Popadic D, Jovanovic T, Bonaci-Nikolic B, Samardzic J, Tomic Spiric V, et al. Developing COVID-19 vaccine recommendations during the pandemic: the experience of Serbia's expert committee on immunization. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:1056670. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1056670

19. Musa, S, Jacques-Carroll L, Palo M. The role of National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups in advising COVID-19 immunization policy during the pandemic: lessons from the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Front. Public Health. (2023) 10:3389. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1193281

20. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Guidance on an Adapted Evidence to Recommendation Process for National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. (2022). Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/356896 (accessed August 29, 2024).

21. World Health Organization. Template: Terms of reference of the National Immunization Technical Advisory Group. (2023). Available at: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/m/item/template–terms-of-reference-of-the-national-immunization-technical-advisory-group (accessed March 12, 2024).

22. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. European Immunization Agenda 2030. (2021). Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/348002/9789289056052-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed June 3, 2024).

Keywords: immunization, evidence-based decision making, middle-income countries, National Immunization Technical Advisory Group (NITAG), evaluation, immunization policy, vaccination, World Health Organization

Citation: Külper-Schiek W, Mosina L, Jacques-Carroll LA, Falman A, Harder T, Kakarriqi E, Preza I, Badalyan A, Sahakyan G, Romanova O, Shimanovich V, Musa S, Bayesheva D, Azimbayeva N, Nurmatov Z, Toigombaeva V, Revenco N, Gutu V, Markovic-Denic L, Bonaci-Nikolic B, Tursunova D, Tadzhiyeva N, Wichmann O and Datta SS (2025) Evaluation of National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs) of middle-income countries in the WHO European Region; a synopsis. Front. Public Health 13:1464370. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1464370

Received: 14 July 2024; Accepted: 27 January 2025;

Published: 19 February 2025.

Edited by:

Hubert Amu, University of Health and Allied Sciences, GhanaReviewed by:

Filippo Quattrone, Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies, ItalyCopyright © 2025 Külper-Schiek, Mosina, Jacques-Carroll, Falman, Harder, Kakarriqi, Preza, Badalyan, Sahakyan, Romanova, Shimanovich, Musa, Bayesheva, Azimbayeva, Nurmatov, Toigombaeva, Revenco, Gutu, Markovic-Denic, Bonaci-Nikolic, Tursunova, Tadzhiyeva, Wichmann and Datta. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wiebe Külper-Schiek, S3VlbHBlcldAcmtpLmRl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.