94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health, 07 April 2025

Sec. Infectious Diseases: Epidemiology and Prevention

Volume 13 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1445543

This article is part of the Research TopicWorld Hepatitis Day 2024: Advancing Hepatitis Elimination, Public Health Strategies and InnovationsView all 13 articles

Introduction: Barber-related infections, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), continue to be a major cause of illness and death. Numerous beauticians use razors and scissors on multiple customers without adequately sanitizing these tools. There is a lack of published research on the prevention practices and associated factors of hepatitis B virus infection among barbers in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the practice and associated factors of hepatitis B virus infection among barbers.

Method: A cross-sectional study was carried out involving 411 barbers selected through simple random sampling. Data collection was performed using an interviewer-administered questionnaire and an observational checklist. The collected data were first cleaned and entered into EpiData version 4.6 and then exported to SPSS version 25 for analysis. Model fitness was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, and multicollinearity was evaluated with the variance inflation factor. A binary logistic regression model was employed for the analysis. To address confounding factors, explanatory variables with a p-value of less than 0.25 in the bivariable logistic regression were included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis. Factors with a p-value of less than 0.05 in the multivariable analysis were considered statistically significant.

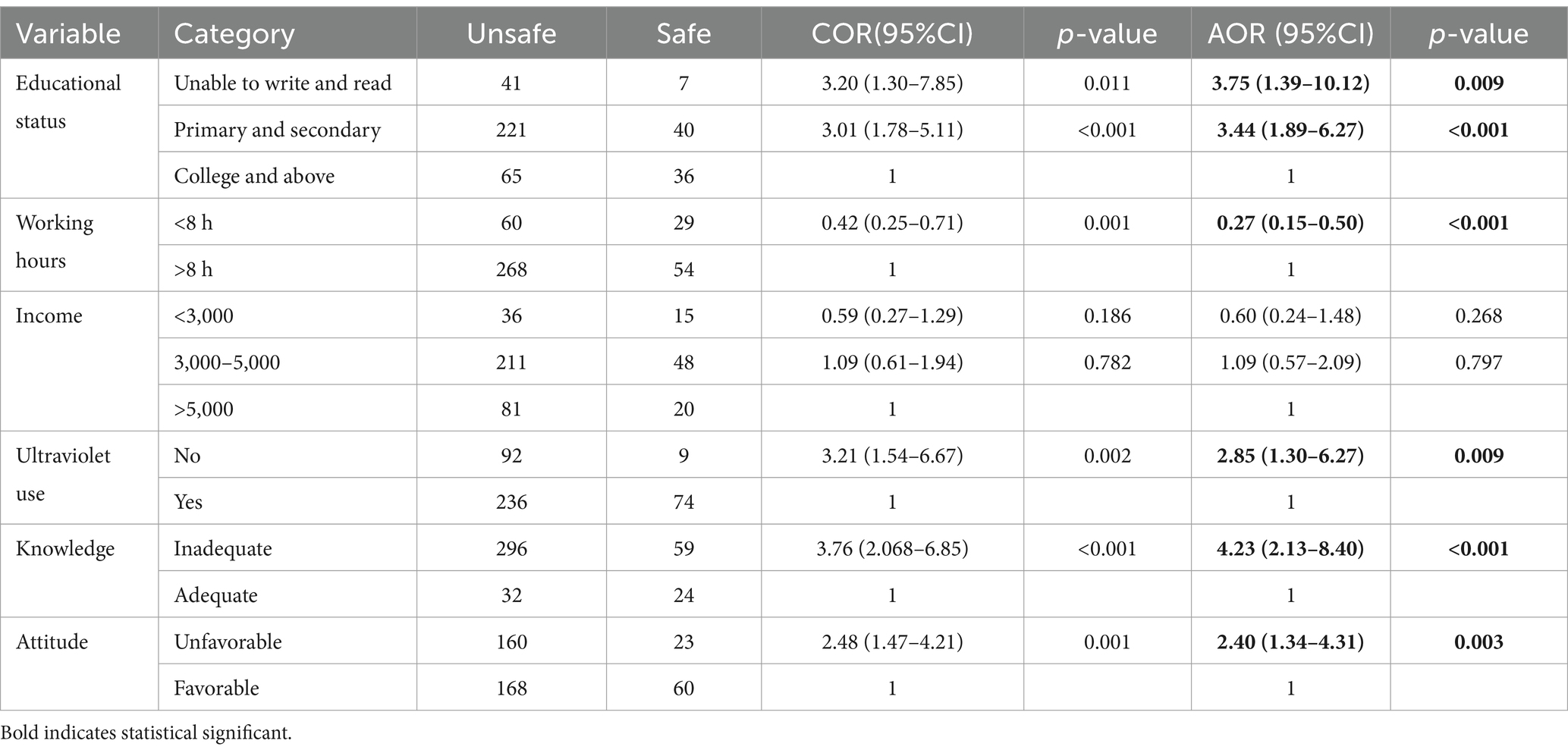

Results: Among the 411 participants, 328 (79.8, 95% CI: 75.6–83.6%) exhibited unsafe hepatitis B virus infection prevention practices. Unsafe practices were significantly associated with barbers who could not read or write (AOR 3.75, 95% CI: 1.39–10.12); primary and secondary education (AOR 3.44, 95% CI: 1.89–6.27) compared to those with college education and above; not using ultraviolet sterilizers (AOR 2.85, 95% CI: 1.30–6.27); insufficient knowledge (AOR 4.23, 95% CI: 2.13–8.40); unfavorable attitudes toward infection control (AOR 2.40, 95% CI: 1.34–4.31); and working hours of less than 8 h (AOR 0.27, 95% CI: 0.15–0.50).

Conclusion: Nearly four-fifths of barbers exhibited unsafe practices in preventing hepatitis B virus infection. Low education levels, not utilizing UV sterilizers, lack of knowledge, working fewer hours, and negative attitudes toward infection prevention were all strongly associated with unsafe practices in the prevention of hepatitis B virus among barbers. Consequently, these findings underscore the need for targeted educational programs, improved access to sterilization tools, and policy changes to promote safer practices.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a serious and potentially life-threatening infection that affects the liver (1). It is a major global public health problem (1).The highest burden of hepatitis B infection is observed in the WHO Western Pacific Region and the WHO Africa Region, with approximately 116 million and 81 million chronically infected people, respectively (2).

Barber-related infections, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), remain a significant cause of illness and death, particularly in emerging and impoverished countries. These challenges are worsened by factors such as poverty and poor sanitation (3, 4). The prevalence of HBV among barbers in Sudan is 10.1% (5).

In regions where unsafe hair-cutting practices are prevalent, there is an increased risk of HBV transmission among various populations, particularly those who frequently visit barbershops. It has been highlighted that individuals who are living in areas with high HBV prevalence are particularly vulnerable as regular visits to barbershops with inadequate infection control measures put them at heightened risk (6).

Unsafe hair-cutting practices are increasingly recognized as a significant risk factor for the transmission of HBV, especially in settings where hygiene standards are not adequately maintained. Studies have shown that barbers and hairdressers often use sharp tools, such as razors and clippers, which may come into contact with blood. If these tools are not properly sterilized, there is a high risk of transmitting HBV through minor cuts, nicks, or shared equipment (7).

Despite the significant occupational risks faced by barbers, those in developing countries often have limited knowledge about HBV (8–10). A study in Pakistan showed only moderate awareness among barbers about the various modes of transmission of hepatitis (10).

Shaving is a widely practiced cultural activity in barbershops and roadside barber setups across much of Africa. This common practice can potentially facilitate the spread of HBV (11). Compared to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), HBV is 50 to 100 times more contagious (12).

Despite their vital role in the community and the continuous support, many barbers do not follow proper and hygienic haircutting practices (13). This activity can promote the spread of certain viruses, thereby contributing to a higher incidence of infectious diseases in many developing countries (14).

Barbers engage in cutting different types of hair, shaving, and trimming beards as part of their work. They are especially vulnerable to infections due to frequent exposure to wounds and scratches caused by sharp tools (11). Hair salons can act as centers for the spread of various contagious diseases, making them potentially hazardous environments. The risk increases significantly if equipment is not thoroughly decontaminated between clients (15).

Many barbers use razors and scissors on multiple customers without properly cleaning them, reflecting a lack of awareness about the risks of spreading germs and viral hepatitis (16). Instruments used in barbershops include trimmers, scissors, hair clippers, razors, blades, shavers, capes, and scarves. Proper sterilization or disinfection of these instruments is important to prevent the transmission of health hazards, including HBV (17).

In many barbershops, the risk of infection is high due to the use of equipment that has not been properly cleaned or decontaminated. This risk extends from patrons to other customers and is further exacerbated if the barber has unprotected cuts or bruises (14). Many individuals use barbershop services in their communities without being aware of these risks. As a result, barbers’ workplaces and activities may become hidden sources of community transmission of communicable diseases (14, 16).

Barbers often have inadequate practices for preventing HBV infections. A lack of awareness about health risks leads to poor habits, insufficient decontamination, and ineffective preventive measures in the barbering industry, creating an environment that facilitates the transmission of HBV (17, 18).

Key risk factors for the transmission of HBV include sharing razors, inadequate sterilization and decontamination of equipment, use of ineffective or questionable cleaning solutions, barbers lacking proper personal protective equipment, and careless handling of sharp objects (11, 14, 16, 17, 19, 20). Barbers in Ethiopia have minimal training and experience in managing the biological hazards associated with their profession (16).

In low-resource countries, most barbers are not vaccinated against HBV, putting them at risk of contracting the virus through unintentional contact with a customer’s blood or bodily fluids while cutting or styling hair (21).

National and municipal health departments, public health agencies, and professionals are highlighting the serious implications of infectious diseases such as hepatitis B associated with this profession through national campaigns and initiatives, including print and electronic media. Despite these efforts, standards in hairdressing practices remain insufficiently high (20).

Despite its significant impact, severity, and adverse consequences, there are limited published studies on the practices and associated factors related to the prevention of HBV among barbers, specifically in the East Gojjam Zone. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the level prevention practice of HBV and identify factors associated with it in Northwest Ethiopia.

Cross-sectional study was employed.

The study was carried out in the East Gojjam Zone, located in the Amhara Regional State of Northwest Ethiopia, with its central city being Debre Markos. Debre Markos is approximately 299 kilometers from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, and approximately 268 kilometers from Bahir Dar, the capital of the Amhara Regional State. According to the 2014 Census by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia, the zone has a population of 2,451,959 total population (1,199,952 males and 1,252,006 females) (22). Within the zone, there are 9 city administrations and a total of 836 barbers. The study took place from 1 April 2023 to 15 June 2023.

All barbers who were working in East Gojjam Zone city administrations.

Barbers who were working in randomly selected cities in East Gojjam city administrations.

All barbers who were working in East Gojjam Zone city administrations.

Participants whose barbershops were closed during the data collection period were excluded from the study.

The sample size was calculated to assess both the level of prevention practices toward HBV and its associated factors. The calculation for the level of practice was based on the single population proportion formula. As the practice of HBV infection prevention and its associated factors had not been previously studied in Ethiopia, an assumption was made that 50% of barbers engaged in unsafe practices (23). With a confidence level of 95%, a margin of error of 5%, and considering a 10% non-response rate, the sample size was determined accordingly. The sample size was calculated by using the statistical formula for the practice level:

where n = desired sample size

Za/2 = Z score at d = 95% confidence level = 1.96,

p = 50% = 0.5.

D = margin of error = 0.05.

n = (1.96)2 (0.5) (0.5)/(0.05)2 n = 384

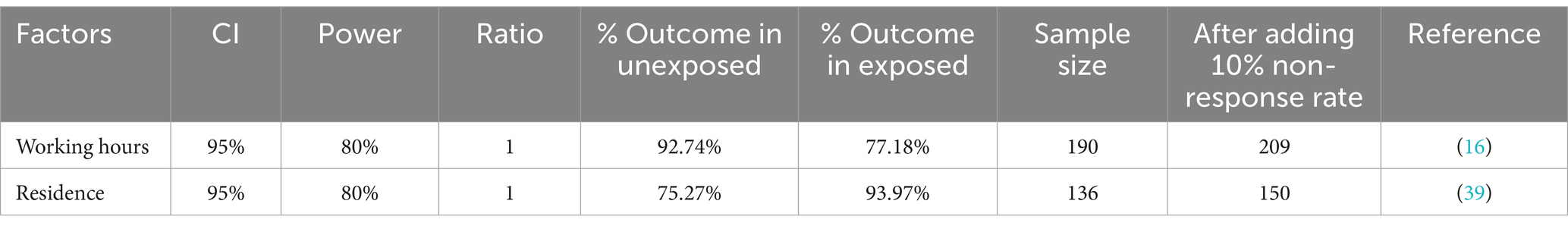

A sample size of 384 was used and after adding a non-response rate of 10%, the final sample size was 423. Sample size for associated factors was calculated (Table 1).

Table 1. Sample size calculation for the associated factors toward HBV prevention practice among Barbers in Northwest Ethiopia.

The largest sample size was found on using single population proportion formula, which was 423.Therefore, the final sample size was 423.

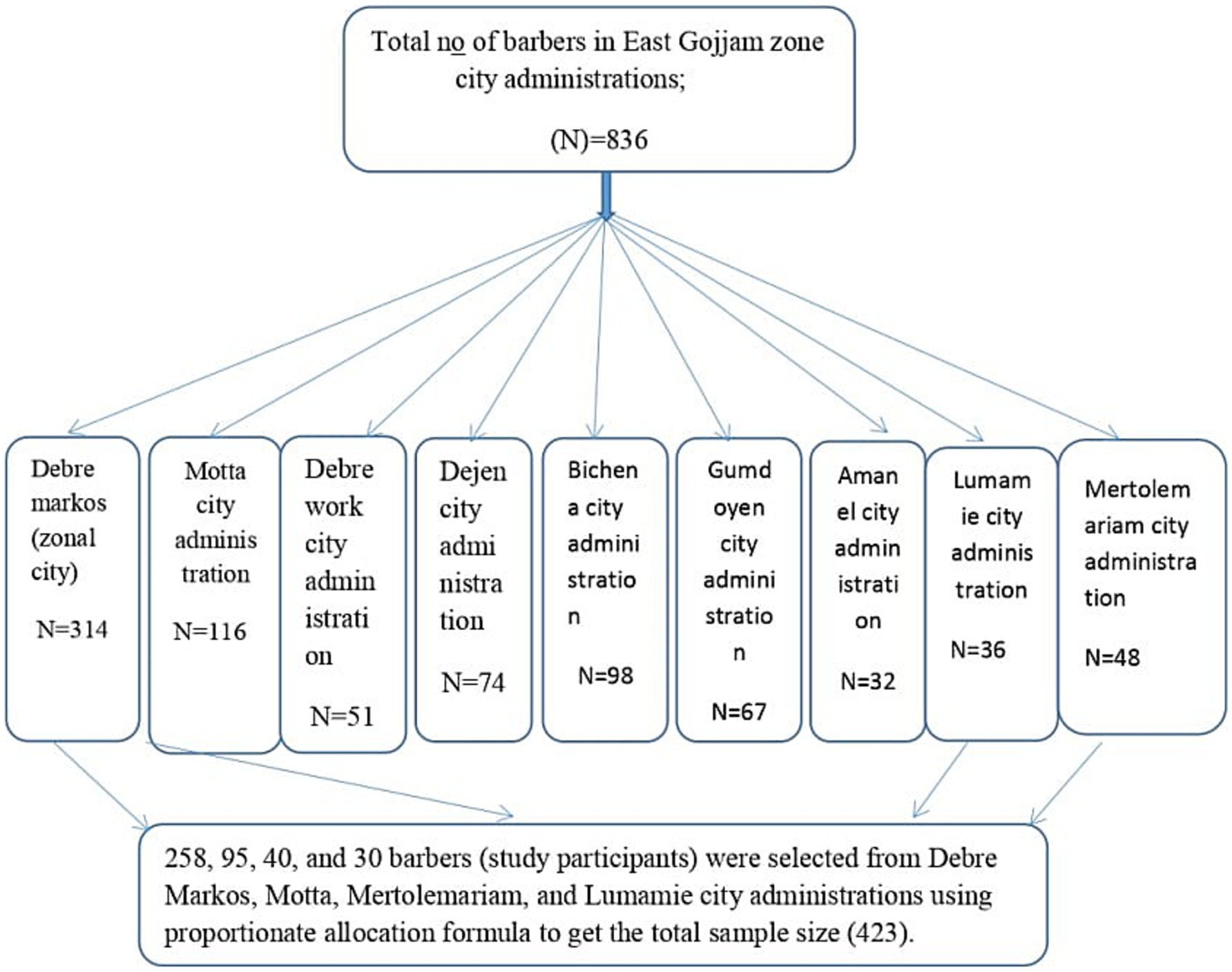

Among the nine city administrations, four of them, namely, Debre Markos, Motta, Mertolemariam, and Lumamie, were randomly selected using a lottery method. The proportionate allocation formula was used to distribute the sample size across the selected city administrations. Within each barbershop, one barber was randomly selected to participate in the study using a lottery method (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Sampling procedure for practice and associated factors toward prevention of hepatitis B virus among barbers in East Gojjam Zone city administrations, Northwest Ethiopia, 2023.

Barbers prevention practices regarding hepatitis B virus prevention (safe vs. unsafe practices).

The independent variables of this study included sociodemographic factors, such as age, sex, educational level, marital status, religion, income, working hours, and work experience, the presence of an ultraviolet sterilizer, and the participants’ knowledge and attitude levels.

Fourteen knowledge-related questions were used to measure the level of knowledge. These questions were structured as Yes or No, with participants earning a score of ‘1’ for a correct answer and ‘0’ for an incorrect one. The total possible score ranged from 0 to 14. Participants who correctly answered more than 50% (7 out of 14) of the questions were categorized as having adequate knowledge (24, 25).

Respondents who correctly answered 50% or fewer of the knowledge questions correctly were considered to have inadequate knowledge (24, 25).

Attitude was assessed using 10 Likert-type questions, with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The maximum possible score was 50, whereas the minimum score was 10. Respondents who correctly answered more than the mean score of 10 attitude questions of the respondents after calculating the mean using SPSS were considered to have a favorable attitude (26).

Respondents who correctly answered at or below the mean score of attitude questions of the respondents after calculating the mean using SPSS were considered to have an unfavorable attitude (26).

The practice level of the respondents was evaluated using 12 Yes or No questions related to practice. Participants received a score of 1 for each correct answer and 0 for each incorrect or unanswered question. The total possible score ranged from 0 to 12. Respondents who correctly answered more than 50% (more than six questions) of the practice questions were classified as having safe practices (24–26).

Respondents who answered 50% or fewer of the practice questions correctly were classified as having unsafe practices (24–26).

NO answer: in the knowledge, and practice questions No refers to the combined response of “No” and “Do not know.”

A barbershop is considered clean if there is no visible dust or dirt on the floor or walls, and if the instruments are shiny, and properly organized (27).

A barbershop is considered attractive if it draws interest through high-quality products, product displays, and a good location or accessibility (28).

A typical situation where outdoor air is exchanged with indoor air through a single window opening (29).

An interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to gather data on respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics (such as age, sex, educational status, and work experience), their practices regarding HBV prevention (using 12 questions), and their knowledge (using 14 Yes or No questions) and attitudes (using 10 Likert-scale questions) toward HBV transmission and prevention methods. Additionally, an observational checklist was used to collect data.

Data collection was carried out by four BSC nurses under the supervision of two BSC supervisors.

Training was provided to both data collectors and supervisors. A pretest was conducted on a 5% sample of the population in Basoliben Woreda 1 week prior to the actual data collection. This pretest aimed to assess the clarity of the data collection tools. Data collectors were trained to reduce ambiguity when respondents required assistance and to enhance the clarity of the information gathered. After data collection, each questionnaire was reviewed for errors and completeness. The collected data were properly handled and stored until analysis. The reliability of the questionnaires was checked using Cronbach alpha with the value of 0.741. This was very important to identify the clarity of the questions in the questionnaire, the time taken to complete the questions, and also, modification has been done.

First, the data were checked for completeness and consistency. Then, it was coded and entered into EpiData version 4.6. After that, the data were exported to SPSS version 25 for analysis. Model fit was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, which indicated good fit with a p-value of 0.48. Multicollinearity was checked using variance inflation factors, with a maximum value of 1.75.

A binary logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with the status of practices among barbers. This was done by calculating the odds ratio and p-value.

Explanatory variables with a p-value less than 0.25 in the bivariable logistic regression were entered into the final multivariable logistic regression analysis to control for possible confounding and to perform further analysis. Variables with a p-value less than 0.05 were considered significantly associated with the dependent variable.

Descriptive analysis using frequencies, proportions, and graphs was performed to describe the number and percentage of sociodemographic characteristics and other variables in the sample.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Review Board (IRERC) of Debre Markos University. The IRERC had reviewed the study protocol and approved it. The approval number provided by IRERC was R/C/S/D/102/01/23. Written informed consent was used. The data were not disclosed to any person other than the principal investigator. Confidentiality of the information was maintained throughout the study. An explanation of the objective of the study was given to the study participants. Written informed consent was used. In addition, affirmation that they are free to withdraw consent and to discontinue participation was made. To ensure confidentiality of the patients’ information, their names and address of the patients were not recorded during the data collection. The investigator used the collected data only to answer the stated objectives. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Out of 423 participants, 411 actually took part in the study, resulting in a response rate of 97.1%. Among these respondents, 335 (81.5%) were male. Approximately 39.9% of the participants were aged between 20 and 29 years, with a mean age of 31.69 years and a standard deviation of ±8.728. The majority, 380 (92.5%), were followers of the Orthodox Christian religion. Approximately 249 (60.6%) had less than 5 years of experience. Additionally, 322 (78.3%) of the participants worked greater than 8 h a day. Nearly three-fourths of the participants, 310 (75.4%), used UV sterilizers. Nearly two-thirds (63.0%) of the participants had a monthly income ranging from 3,000 to 5,000 Ethiopian birr (Table 2).

Out of the total participants, 355 (86.4%) had inadequate knowledge, whereas 56 (13.6%) had adequate knowledge, based on the knowledge questions they answered according to the operational definitions provided above (Table 3).

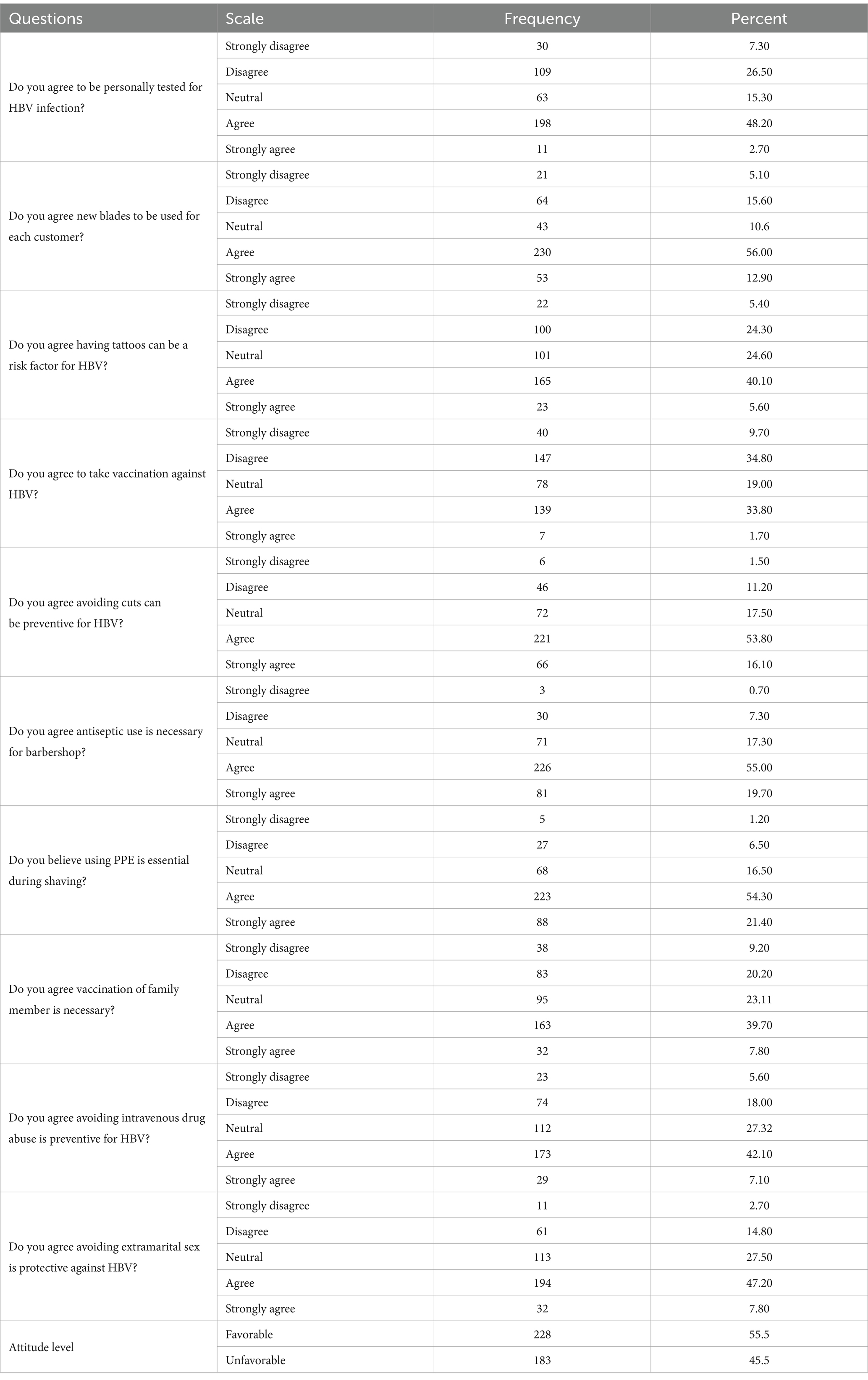

Approximately 228 (55.5%) of the barbers had a favorable attitude, whereas 183 (44.5%) had an unfavorable attitude. The attitudes of barbers were assessed through 10 questions, each rated from 1 to 5, with a total score range of 10 to 50. The mean score was used to classify attitudes: barbers who scored below or equal to the mean of 33.98 were considered to have an unfavorable attitude, whereas those who scored above the mean were regarded as having a favorable attitude (Table 4).

Table 4. Attitude of barbers on HBV infection prevention practices in East Gojjam Zone, 2023 (n = 411).

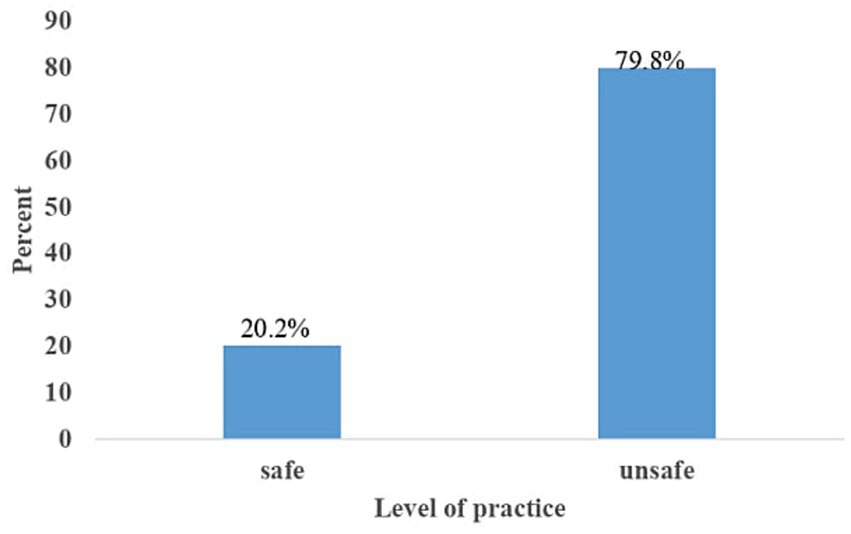

In this study, 328 (79.8%) of the respondents had unsafe practices (95% CI [75.6–83.6%], Figure 2). Among the respondents, 99 (24.1%) washed their hands before and after cutting and shaving, 21 (5.1%) used gloves, 302 (73.5%) used a new blade for each customer, and 347 (84.4%) reused towels without sterilization. Additionally, 269 (65.5%) disinfected or sterilized instruments, 380 (92.5%) used razors for shaving, 103 (25.1%) changed combs, and 334 (81.3%) used an apron during shaving. Only 20 (4.9%) were screened for HBV, and 9 (2.2%) were vaccinated for HBV. Furthermore, 200 (48.7%) properly disposed of blades, and 216 (52.6%) managed cuts with antiseptics (Table 5).

Figure 2. Hepatitis B virus prevention practice status among barbers in East Gojjam Zone city administrations, 2023.

Approximately 284 (69.1%) of the barbershops were well ventilated, 222 (54.0%) of the barbershops were clean, 233 (56.7%) of the barbershops were considered attractive, and 212 (51.6%) had their own water supply. Nearly all participants (408) had an electricity supply; those without electricity used manual shavers.

Approximately 359 (87.3%) of the respondents did not wash their hands. Almost all participants (408 or 99.3%) did not use gloves. Approximately 42 (10.3%) did not use a new blade for each customer. Approximately 130 (31.6%) reused towels without sterilization. Approximately 144 (35%) did not disinfect or sterilize instruments. Approximately 334 (81.3%) did not change combs; 388 (94.4%) used razors for shaving; approximately half of them, 223 (54.3%), did not properly dispose of blades; and 220 (53.5%) did not manage cuts with antiseptics.

In the bi-variable logistic regression analysis, the following variables were deemed eligible for inclusion in the multivariable logistic regression model based on a p-value of <0.25: educational status, income, working hours, knowledge, attitude of barbers, and ultraviolet sterilizer use.

In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, the predictor variables that were significantly associated with practice included educational status, working hours, knowledge, attitude of barbers, and the use of ultraviolet sterilizers.

This study found that barbers who could not read or write were nearly four times more likely to engage in unsafe practices (AOR 3.75, 95% CI [1.39–10.12]) than those with college education or higher. Additionally, barbers with primary and secondary school education were 3.4 times more likely to have unsafe practices (AOR 3.44, 95% CI [1.89–6.27]) than those with college education or higher.

Barbers who were using ultraviolet sterilizers were nearly three times more likely to have unsafe practices (AOR 2.85, 95% CI [1.30–6.27]) than those who did not use ultraviolet sterilizers.

This study revealed that barbers with inadequate knowledge were more than four times more likely to engage in unsafe practices (AOR 4.23, 95% CI [2.13–8.40]) than those with adequate knowledge. Additionally, barbers with an unfavorable attitude were more than two times as likely to have unsafe practices (AOR 2.40, 95% CI [1.34–4.31]) than those with a favorable attitude.

Furthermore, barbers who worked less than 8 h were 3.7 times less likely to practice unsafe methods (AOR 0.27, 95% CI [0.15–0.50]) than those working more than 8 h (Table 6).

Table 6. Bivariable and multi variable logistic regression results of factors affecting the barber’s prevention practices in East Gojjam Zone city administrations, 2023 (n = 411).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevention practices and associated factors related to the prevention of hepatitis B virus among barbers in East Gojjam, Northwest Ethiopia. In this study, 79.8% (95% CI: 75.6–83.6%) of the respondents had unsafe practice. This high prevalence of unsafe practices suggests the need for urgent intervention to improve awareness, training, and infection control measures in study setting.

This level of practice was higher than studies in Hawassa, Ethiopia 28.5% (30); Woldia, Ethiopia 59.5% (24); Mosul 58.33% (18); and Fiji (64.1%) (17). This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in socio-demographic factors, sample size, and economic status between regions (31). The sample size in the current study was relatively small, with 117 participants in Fiji and 60 participants in Mosul. In contrast, the sample size in Hawassa was larger, but there were differences in the items used to assess the practice level.

The findings of this study indicated that the level of unsafe practices was lower than those observed in studies conducted in Sudan (5), Yemen (32), Izmir (33), and Punjab (34). This discrepancy may be due to differences in access to healthcare infrastructure, resources, and technology among the countries, influenced by economic and other social factors. For example, barbers in more developed countries may have better access to sterilization equipment (e.g., ultraviolet sterilizers) and more disposable income to invest in these tools. In contrast, in developing countries like Ethiopia, economic constraints may limit access to such resources, leading to unsafe practices.

This study shows that barbers who did not use ultraviolet sterilizers (AOR 2.85, 95% CI: 1.30–6.27) were significantly associated with unsafe practices. This finding is supported by studies in Gondar, Ethiopia (16) and Hawassa, Ethiopia (30). This is because barbers who use ultraviolet sterilizers understand the significance of these devices. Ultraviolet sterilizers are highly effective in eliminating all types of microorganisms as they use light with a wavelength of at least 253.7 nanometers to disinfect bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms (35, 36), thus preventing infections. However, if barbers do not use this equipment, they may transmit microorganisms from one customer to another, potentially even to themselves. Moreover, the use of proper sterilization equipment is essential for preventing HBV transmission in barbershops. Inadequate sterilization practices, including the failure to use ultraviolet sterilizers, have been documented as major risk factors for the spread of bloodborne infections (37). This highlights the need for policies to ensure barbershops have access to and use effective sterilization tools, particularly in resource-limited settings. Poor knowledge is likely to be associated with unfavorable attitudes (38).

In this study, Barbers who cannot read and write [AOR, 3.75, 95% CI (1.39–10.12)] and barbers who were at primary and secondary levels [AOR, 3.44, 95% CI (1.89–6.27)] were significantly associated with unsafe practice. This result was supported by studies in Gondar, Ethiopia (39), and Italy (40). This is because when barbers have inadequate knowledge about the causes, risk factors, and transmission routes of infections, they fail to properly clean, disinfect, and sterilize barbering instruments to eradicate microorganisms. Additionally, they may not use personal protective equipment to minimize cross-contamination for both their customers and themselves (41). As a result, infectious diseases can spread from person to person.

Moreover, it is obvious that improving the educational status of barbers may be a crucial intervention for bettering HBV prevention practices as education plays a crucial role in fostering the use of health-promoting habits. These results recommends the importance of ensuring that barbers receive adequate education and training, particularly in the areas of infection control and disease prevention.

This study found that barbers with inadequate knowledge (AOR 4.23, 95% CI: 2.13–8.40) and unfavorable attitudes toward infection control (AOR 2.40, 95% CI: 1.34–4.31) were more likely to be engaged in unsafe practices. This is due to a lack of awareness about HBV transmission and prevention methods can lead to negligent practices that increase the risk of infection (20). Similarly, unfavorable attitudes toward infection control may reflect a lack of motivation or perceived importance of adhering to safety procedures. These findings emphasize the need for organized training programs that maintain barbers with the necessary knowledge about HBV transmission, prevention strategies, fostering positive attitudes toward infection control, and the importance of infection control measures.

Barbers who worked fewer than 8 h were 3.7 (1/2.70) times less likely to practice unsafe methods (AOR 0.27, 95% CI 0.15–0.50) than those working more than 8 h, contrary to studies in Gondar (16) and Hawassa (30). Barbers who work less hours may have more time to devote to infection control practices, like properly sterilizing instruments and following hygiene guidelines. However, extended workdays may result in exhaustion, rushed processes, and a disregard for safety precautions.

Barbers’ practices regarding the prevention of hepatitis B virus infection were found to be substandard. Unsafe practices were significantly associated with several factors, including lower education levels among barbers, non-use of ultraviolet sterilizers, inadequate knowledge, working less than 8 h, and having an unfavorable attitude toward hepatitis B infection prevention.

To improve the knowledge and practices of barbers, specific actions should be implemented, such as providing training on infection control. Barbers should use ultraviolet sterilizers and appropriate personal protective equipment to prevent the transmission of infectious diseases, including HBV. Qualitative studies could also be conducted to gain a deeper understanding of the poor attitudes and practices observed.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Research Ethics Review Board (IRERC) of Debre Markos University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

BTA: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BL: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ST: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

First, I would like to thank Debre Markos University College of Health Sciences for supporting and approval of the ethical concerns to develop this thesis. Moreover, I would like to thank all study participants, zonal health Bureau, and data collectors for their participation and support.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AOR, Adjusted odd ratio; CD, Communicable disease; CI, Confidence interval; COR, Crude odd ratio; HBV, Hepatitis B virus; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; UV, Ultraviolet; WHO, World Health Organization.

1. Poordad, FF. Presentation and complications associated with cirrhosis of the liver. Curr Med Res Opin. (2015) 31:925–37. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1021905

2. Iannacone, M, and Guidotti, LG. Immunobiology and pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus infection. Nat Rev Immunol. (2022) 22:19–32. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00549-4

3. Wazir, MS, Mehmood, S, Ahmed, A, and Jadoon, HR. Awareness among barbers about health hazards associated with their profession. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. (2008) 20:35–8.

4. Ambadekar, N, Wahab, S, Zodpey, S, and Khandait, D. Effect of child labour on growth of children. Public Health. (1999) 113:303–6. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(99)00185-7

5. Nafi, M, Elmonzir, M, Elkhair, A, and Abdeen, N. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus among barbers at South Khartoum. Sudan Med Lab J. (2022) 10:45–51. doi: 10.52981/smlj.v10i1.2773

6. Adjei-Gyamfi, S, Asirifi, A, Asobuno, C, and Korang, FK. Knowledge and occupational practices of beauticians and barbers in the transmission of viral hepatitis: a mixed-methods study in Volta region of Ghana. PLoS One. (2025) 20:e0306961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0306961

7. Yang, J, Hall, K, Nuriddin, A, and Woolard, D. Risk for hepatitis B and C virus transmission in nail salons and barbershops and state regulatory requirements to prevent such transmission in the United States. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2014) 20:E20–30. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000042

8. Mutocheluh, M, and Kwarteng, K. Knowledge and occupational hazards of barbers in the transmission of hepatitis B and C was low in Kumasi, Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. (2015) 20:20. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.260.4138

9. Belbacha, I, Cherkaoui, I, Akrim, M, Dooley, K, and El Aouad, R. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C among barbers and their clients in the Rabat region of Morocco. Eastern Medit Health J. (2011) 17:911–9. doi: 10.26719/2011.17.12.911

10. Waheed, Y, Saeed, U, Safi, SZ, Chaudhry, WN, and Qadri, I. Awareness and risk factors associated with barbers in transmission of hepatitis B and C from Pakistani population: barber’s role in viral transmission. Asian Biomed. (2010) 4:435–42. doi: 10.2478/abm-2010-0053

11. Sarkar, MAM, Saha, M, Hasan, MN, Saha, BN, and Das, A. Current status of knowledge, attitudes, and practices of barbers regarding transmission and prevention of hepatitis B and C virus in the north-west part of Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study in 2020. Public Health Pract. (2021) 2:100124. doi: 10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100124

12. Weinbaum, CM, Williams, I, Mast, EE, Wang, SA, Finelli, L, Wasley, A, et al. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. (2008) 57:1–20.

13. Hussain, I, Bilal, K, Afzal, M, and Arshad, U. Knowledge and practices regarding hepatitis B virus infection and its prevalence among barbers of rural area of Rahim Yar Khan. Infection. (2018) 13:13.

14. Chand, D, Mohammadnezhad, M, and Khan, S. An observational study on barbers practices and associated health Hazard in Fiji. Global J Health Sci. (2022) 14:108. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v14n3p108

15. Sawayama, Y, Hayashi, J, Kakuda, K, Furusyo, N, Ariyama, I, Kawakami, Y, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in institutionalized psychiatric patients. Dig Dis Sci. (2000) 45:351–6. doi: 10.1023/A:1005472812403

16. Beyen, TK, Tulu, KT, Abdo, AA, and Tulu, AS. Barbers' knowledge and practice about occupational biological hazards was low in Gondar town, North West Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. (2012) 12:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-942

17. Chand, D, Mohammadnezhad, M, and Khan, S. Levels and predictors of knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding the health hazards associated with Barber’s profession in Fiji. Inquiry: J Health Care Organ Prov Finan. (2022) 59:00469580221100148. doi: 10.1177/00469580221100148

18. Mahmood, HJ, and Hassan, ET. Assessment barbers Knowledge's and Practice's about hepatitis virus in Mosul City. Age. (2018) 15:16.

19. Mele, A, Corona, R, Tosti, ME, Palumbo, F, Moiraghi, A, Novaco, F, et al. Beauty treatments and risk of parenterally transmitted hepatitis: results from the hepatitis surveillance system in Italy. Scand J Infect Dis. (1995) 27:441–4. doi: 10.3109/00365549509047042

20. Shah, HBU, Dar, MK, Jamil, AA, Atif, I, Ali, RJ, Sandhu, AS, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of hepatitis B and C among barbers of urban and rural areas of Rawalpindi and Islamabad. J Ayub Med College Abbottabad. (2015) 27:832–6.

21. Adoba, P, Boadu, SK, Agbodzakey, H, Somuah, D, Ephraim, RKD, and Odame, EA. High prevalence of hepatitis B and poor knowledge on hepatitis B and C viral infections among barbers: a cross-sectional study of the Obuasi municipality, Ghana. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2389-7

22. Motbainor, A, Worku, A, and Kumie, A. Stunting is associated with food diversity while wasting with food insecurity among underfive children in east and west Gojjam zones of Amhara region, Ethiopia. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0133542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133542

24. Gebremeskel, T, Beshah, T, Tesfaye, M, Beletew, B, Mengesha, A, and Getie, A. Assessment of knowledge and practice on hepatitis B infection prevention and associated factors among health science students in Woldia University, Northeast Ethiopia. Adv Prev Med. (2020) 2020:1964. doi: 10.1155/2020/9421964

25. Shalaby, S, Kabbash, I, El Saleet, G, Mansour, N, Omar, A, and El Nawawy, A. Hepatitis B and C viral infection: prevalence, knowledge, attitude and practice among barbers and clients in Gharbia governorate, Egypt. Eastern Medit Health J. (2010) 16:10–7. doi: 10.26719/2010.16.1.10

26. Almasi, A, Dargahi, A, Mohammadi, M, Asadi, F, Poursadeghiyan, M, Mohammadi, S, et al. Knowledge, attitude and performance of barbers about personal health and occupational health. Arch Hyg Sci. (2017) 6:75–80. doi: 10.29252/ArchHygSci.6.1.75

29. Gan, G. Effective depth of fresh air distribution in rooms with single-sided natural ventilation. Energ Build. (2000) 31:65–73. doi: 10.1016/S0378-7788(99)00006-7

30. Daka, D. Barbers knowledge and practice of biological hazards in relation to their occupation: a case of Hawassa town, southern Ethiopia. J Public Health Epidemiol. (2017) 9:219–25. doi: 10.5897/JPHE2017.0919

31. Mills, A. Health care systems in low-and middle-income countries. N Engl J Med. (2014) 370:552–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1110897

32. Al-Rabeei, NA, Al-Thaifani, AA, and Dallak, AM. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of barbers regarding hepatitis B and C viral infection in Sana’a City, Yemen. J Community Health. (2012) 37:935–9. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9535-7

33. Mandiracioglu, A, Kose, S, Gozaydin, A, Turken, M, and Kuzucu, L. Occupational health risks of barbers and coiffeurs in Izmir. Indian J Occup Environ Med. (2009) 13:92–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.55128

34. Butt, AK, and Khan, AA. A pilot study of knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) of barbers and unqualified dentists in transmission of hepatitis band C in an urban and rural setting in Punjab. Proc SZPGMI IOI. (2007) 21:75–81.

35. Walker, RW, Markillie, LM, Colotelo, AH, Geist, DR, Gay, ME, Woodley, CM, et al. Ultraviolet radiation as disinfection for fish surgical tools. Anim Biotelem. (2013) 1:4–11. doi: 10.1186/2050-3385-1-4

36. Buonanno, M, Welch, D, Shuryak, I, and Brenner, DJ. Far-UVC light (222 nm) efficiently and safely inactivates airborne human coronaviruses. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67211-2

37. Rutala, WA, and Weber, DJ. Disinfection and sterilization in health care facilities: an overview and current issues. Infect Dis Clin N Am. (2016) 30:609–37. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2016.04.002

38. Hassali, MA, Shafie, AA, Saleem, F, Farooqui, M, Haseeb, A, and Aljadhey, H. A cross-sectional assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice among hepatitis-B patients in Quetta, Pakistan. BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-448

39. Gebrecherkos, T, Girmay, G, Lemma, M, and Negash, M. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards hepatitis B virus among pregnant women attending antenatal care at the University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Int J Hepatol. (2020) 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2020/5617603

40. Amodio, E, Di Benedetto, MA, Gennaro, L, Maida, CM, and Romano, N. Knowledge, attitudes and risk of HIV, HBV and HCV infections in hairdressers of Palermo city (South Italy). Eur J Pub Health. (2010) 20:433–7. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp178

Keywords: prevention practices, factors, hepatitis B virus, barber, Ethiopia

Citation: Amlak BT, Lake Mengistie B and Teshale SA (2025) Prevention practices of hepatitis B virus and its associated factors among barbers in East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia. Front. Public Health. 13:1445543. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1445543

Received: 07 June 2024; Accepted: 25 March 2025;

Published: 07 April 2025.

Edited by:

Ritthideach Yorsaeng, Chulalongkorn University, ThailandReviewed by:

Leykun Berhanu, Wollo University, EthiopiaCopyright © 2025 Amlak, Lake Mengistie and Teshale. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Baye Tsegaye Amlak, YmF5ZV90c2VnYXllQGRtdS5lZHUuZXQ=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.