- 1Department of Physiotherapy, Health University of Applied Sciences Tyrol, Innsbruck, Austria

- 2Queen Maud University College of Early Childhood Education, Trondheim, Norway

Environmental physiotherapy is epistemologically anchored in the critical recognition that physiotherapeutic practice is fundamentally embedded within a planetary ecological framework, demanding a holistic, systemically integrated approach to professional practice. This perspective article highlights and underscores the value of risky play for child health and the commonalities with environmental pediatric physiotherapy. The article starts with a discussion of current challenges in child health around the globe, often resulting from a lack of physical activity of children, and claims finding new, promising and sustainable ways that are able to attract children and their parents to playfully increase the time that children are physically active. Followed by an overview of physiotherapists’ roles and responsibilities in child public health, the authors point to the need to move beyond an isolated profession-centric approach when tackling the existing, concerning issues in child health worldwide. Foundational information about risky play underpinned with scientific results and its acknowledgment by other health professions is then presented. By including a perspective of what children want, the authors identify a gap between the world’s children’s actual needs and current societal offers. The benefits of risky play for child health are presented in detail, along with a discussion of various considerations pertaining to child safety. Concluding, this perspective article demonstrates how physiotherapists can contribute to better child health by including risky play in physiotherapy theory and practice.

1 Introduction

About 80% of the world’s youth does not meet the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) to be physically active for at least 60 min per day (1, 2), contributing to a global pandemic of physical inactivity, which is considered to be a major cause of global mortality (1–4). According to the WHO, in 2022, 37 million children under the age of 5 and 390 million children between 5 and 17 years old were overweight or obese, with increasing numbers in high-, middle-as well as in low-income countries (4, 5). One of the multifactorial reasons for this unfavorable development is insufficient levels of physical activity in children and adolescents (6), an accelerant for an early onset of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes type 2, cardiovascular diseases, neurological and mental health disorders, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases, or eating disorders (5, 7). Children with disabilities are even more predisposed to developing secondary health conditions (8).

Physical activity is clearly related to better health outcomes and recognized to be one of the most efficient ways to enhance a person’s overall health across their lifespan (9–12). A decrease of 15% in physical inactivity worldwide is targeted by the WHO Global Action Plan on NCDs, by 2030. However, the implementation of physical activity on national levels is still insufficient (13). Although there is enough research proving the health benefits of physical activity, conducted over decades, the number of NCDs still increases, and rates of physical activity are changing slowly. Do we miss something important? Of course, better infrastructures, more resources for physical activity, as well as effective coalitions of multiple sectors are important for achieving more meaningful results (1, 14). But considering the huge amount of children and adolescents identified as being physically inactive around the globe (15), new, effective, and low-threshold strategies of health promotion are required to address these concerning developments in child health. It has been identified as a worldwide priority to develop approaches to target these concerning issues that are accessible, acceptable, cost-effective, culturally adaptable, feasible and to ensure an optimal compliance—of course fun (3, 16–19).

There is a tendency for physical activity and sedentary behavior habits learned during childhood to persist into adulthood (20). This highlights the importance to find joyful and meaningful ways for children, at an early age, to bodily movement and being physically active. Children with disabilities and of course also those without disabilities experience physiotherapy more positively when it is engaging, fun and pleasurable (21). Promoting physical activity in children should enable a broader health experience, including a lively child-environment interaction (22), which contributes to satisfaction, enjoyment, perceptions of social inclusion, and self-efficacy (23). Playful physical activities are promising to reach a large group of children, allowing them to explore, develop and enhance their physical abilities, motor and social skills, sense of belonging, self-efficacy and self-awareness, as well as to playfully integrate and overcome their fears. Not only is a child’s right to play enshrined by Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (24), play is necessary for child development. It is considered to be therapeutic, an instinctive mode of self-directed learning and efficient means of teaching and guidance, and a contribution to and enactment of health and wellbeing (25). Interestingly, the UN’s general comment on the fulfillment of Article 31 has identified an increased safety focus and a lack of access to nature as threats to children’s free play (26).

Physiotherapists are well-situated to mitigate these threats impacting child health. They are autonomous experts (27), tailoring individualized activity programs aligning with each child’s unique motor developmental profile and functional capabilities (28). Physiotherapists engage with children and their families during developmental stages when health-related behaviors are amenable to intervention and modification and are expected to actively advocate for innovative strategies that foster health prevention and physical well-being among children throughout their lifespan (28–30). They work interdisciplinary in clinics, schools, communities, early childhood centers and hospitals, provide child and family-focused education, and identify and connect families with resources for health promotion and motor skill acquisition (28). Physiotherapists play an active role in bringing the United Nation’s Agenda 2023 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into life (31–34), create effective interdisciplinary coalitions to implement the WHO Global Action Plan on NCDs (1) and transcend biomedical perspectives on child health and disability into holistic perspectives by applying the WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY) (22, 35, 36). In this perspective article, we aim to highlight both, the value of risky play for child health and the worth of including this pedagogical stance into the provision of physiotherapy services. Contributing to this special issue on reframing the role of the physiotherapy profession in the Anthropocene, we will put weight on outdoor risky play during early childhood. We outline the well documented benefits of risky play for child health and overall development, and claim more and broader recognition of these benefits by the physiotherapy profession. Additionally, we advocate for future research investigating the interplay of physiotherapy, risky play and child health and the inclusion of knowledge about risky play in physiotherapy curricula to support contemporary pediatric physiotherapy.

2 Risky play

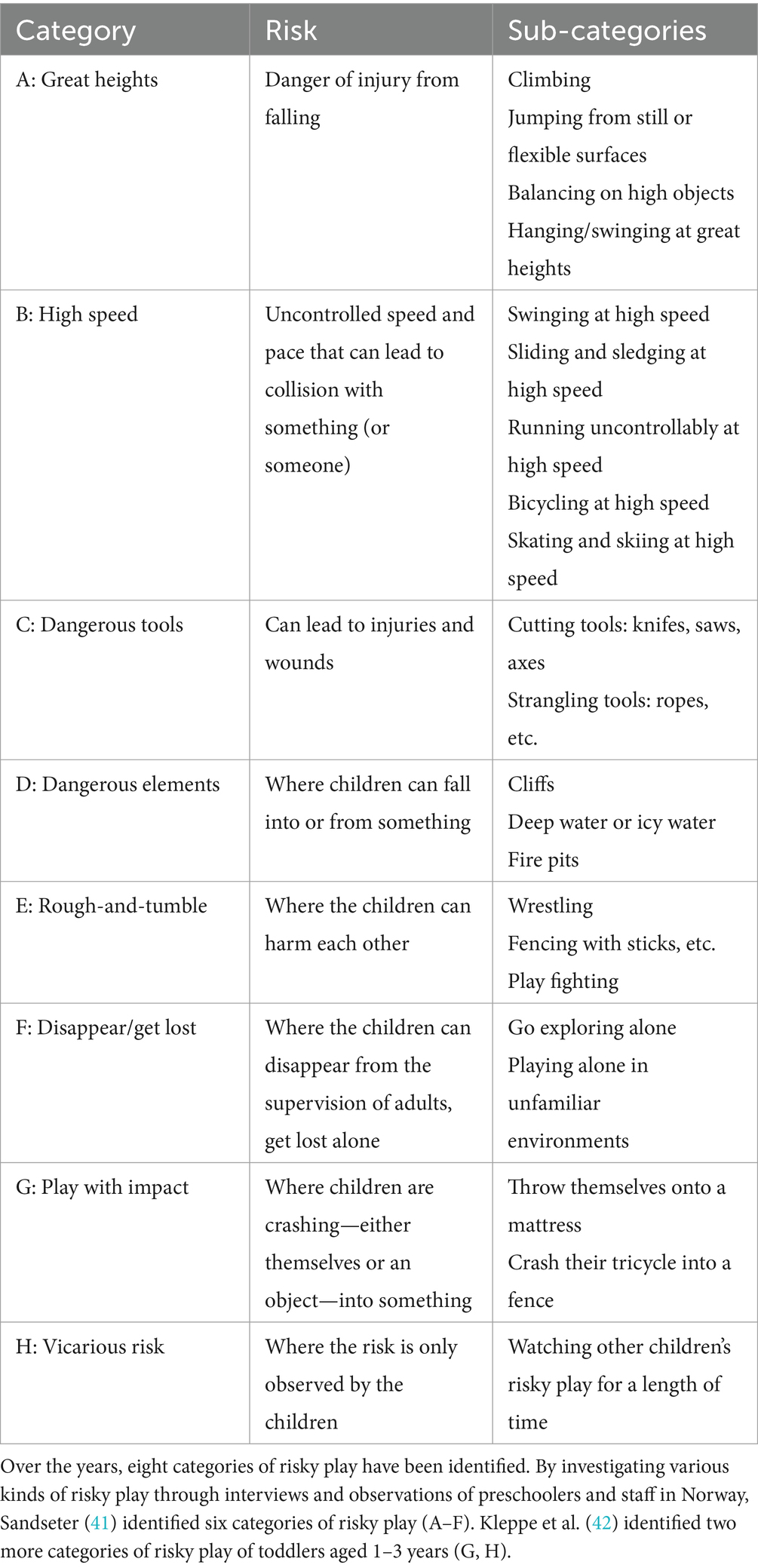

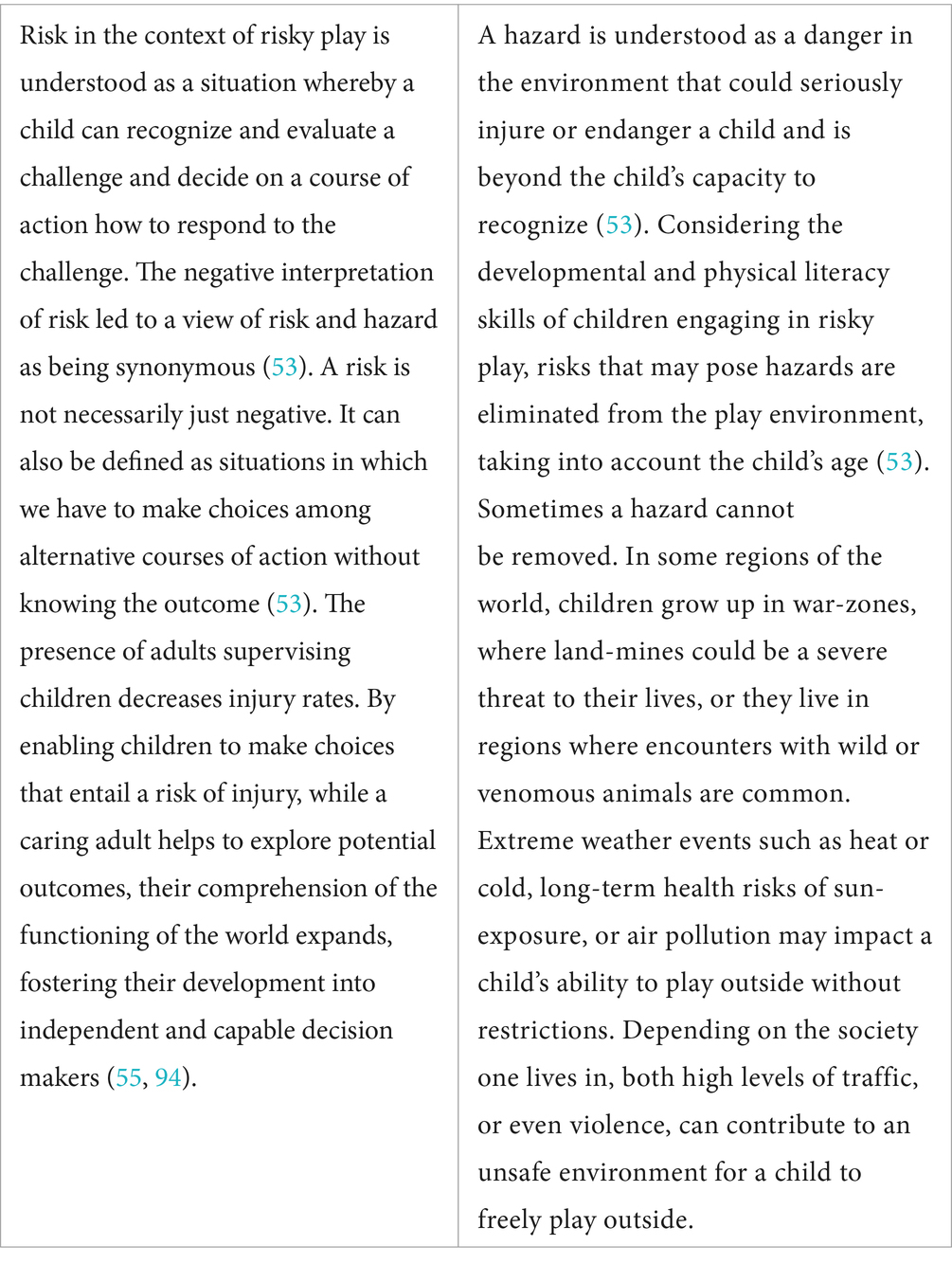

Risky play is defined as thrilling and exciting forms of play that involve a potential risk of injury (37), with ambiguity and uncertainty being understood as important characteristics (38). Risky play can happen indoors but is most common in outdoor settings where children are allowed to play freely (39, 40). Eight categories of risky play (see Table 1) have been identified through observations and interviews with children and adults (41, 42). Most of the research on children’s risky play has been situated within the context of early childhood education, focusing on 1 to 6-year-olds. Children seek thrills and risks in their play and on a level that suits their individual competence and courage (43–45). Research shows that risky play is a common type of play both among girls and boys and across ages in the early years (39, 41, 42). Taking risks in play is also strongly connected to children’s risk management skills. Research identifies how children are aware of the risk they are taking and how they mitigate or increase the risk according to their own skills and how they experience the situation (46, 47), and in addition, how risky play contributes to increased risk assessment skills (48).

In children with disabilities, the understanding of risk-taking and risky play is wider and more inclusive and does not contradict the original intention of the concept of risky play as being unstructured, child-driven activities (49). In a recent position statement, the Canadian Pediatric Society underscored the value of risky play for children’s healthy physical, mental, and social development (50) due to its potential to prevent injuries (51, 52) by children learning how to manage risks and tackling health problems such as poor development of motor functions, obesity, anxiety, and behavioral issues (9, 50, 53–56). Research showed that physical activity is 2.2 to 3.3 times higher when children are playing outdoors than indoors, independent of different age groups, sexes, and contexts (16). Children spend significantly more time being active in adventurous environments than where structures are pre-fabricated (55). Furthermore, natural environments provide the ideal conditions for children, regardless of varying developmental levels, to engage in challenging and exciting forms of playful physical activity (38, 57–59). Unfortunately, children’s opportunities to play freely outdoors are decreasing. The reasons for this can be grouped into four categories: time (nature-starved curriculum, time-poor parents, lack of time for free play), fear (stranger danger, dangerous streets, risk-averse culture); technology (rise of screen time); and space (vanishing green space) (60). Recently, the negative consequences of the rise of social media have been discussed in depth, pointing to risky play as an effective way to ensure ideal childhood development for current and future generations (61). Within the physiotherapy profession, the Australian Physiotherapy Association (APA) advocated for risky play as a response to school lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic (62), and an online course for rehabilitation professionals has been released to highlight the benefits of risky play for child health (63).

2.1 What children want

Children prefer playing with natural materials and in natural environments over screen time (25, 38). If children have the opportunity to experience nature, they develop a sense of care and a desire to conserve it (64). The experience of fun has been identified as a central experience for children, found within all physical and social environments. Children seek intense play experiences, want to make their own choices about what to play, and want to belong to their playgrounds (57). Obviously, what children around the globe mostly want and long for, differs more and more from what the societies they live in offer them: car-oriented, urbanized and increasingly highly digitalized, rather risk-averse societies as well overprotective environments, resulting in social encounters which rather isolate from each other than bringing communities actively together (61, 65), further contributing to nature-deficit disorders (66). Current generations of children spend less time playing outside and do so less frequently compared to their parents’ generation (64, 67, 68). There is a shift in children’s physical activity away from unsupervised and unstructured outdoor play toward structured and supervised activities that are primarily performed indoors (16, 18).

2.2 Why is risky play so important for children?

Engaging children in risky play is one of the best ways of injury prevention because their experiences lead to the ability to manage risks (52, 53). Children acquire coping mechanisms to handle risky situations by engaging in playful methods to evaluate and conquer risks, adapting to failure and adverse outcomes of their choices, leading to resilience and self-sufficiency (69). Risky play is naturally not only observed in children of all cultures but is found in many mammal species, representing an adaptive function (53, 54) by supporting the offspring in developing cognitive, emotional, motor, functional and social abilities. Playing freely plays an important role in the neurophysiological maturation of the prefrontal cortex, which influences self-regulation of behavior and impulsiveness and encourages self-reflection (56, 70–72). Risky play is considered to have an anti-phobic effect on a child’s physiological development, where a child will first show normal adaptive fears, which protect it against various risk factors. Risky play is a stepwise fear-reducing behavior. Hindering children from taking part in age-adequate risky play may result in increased neuroticism or psychopathology in society, as the fears may continue despite being no longer relevant due to a child’s physical and psychological maturation, possibly even turning into anxiety disorders (56).

The rising anxiety about children’s safety has been described as a common feature of modern societies. Besides overprotective parenting, also the conception of childhood has changed (65). The understanding of a child as resilient and capable shifted to the picture of a vulnerable child who needs continuous safeguarding, although this may not be true for all children and societies (73). Physiotherapists invest a great deal of time and effort by educating patients and the public to combat such misleading beliefs that can influence an individual’s lifestyle choices and quality of life (74, 75). Indeed, research shows that toddlers have the ability to assess and manage potential risks when they play outside in natural environments. Even 4 to 5-years old children were reported to be able to balance their risk-taking decisions between their evaluation of positive and negative outcomes of the play (76). Toddlers’ engagement in risky play promotes a sense of belonging through shared engagement in risky play experiences and by developing a personal connection with the place. Furthermore, social belonging to the group becomes evident when children demonstrate care and support towards each other when children’s peers stumble and fall whilst navigating through challenging environments (77).

Preschoolers spend up to twice as much time being sedentary indoors than when they are outdoors. The longer the time that children are outside, the more active they are (16). Natural landscapes play a significant role in the motor development of children, as gross motor functions such as running, jumping, throwing, climbing or crawling are predominant when children actively play in nature (78). Outdoor activity in children is related to lower diastolic blood pressure and to greater aerobic fitness (16). Additionally, nature-based activities in early childhood increase the diversity of children’s gut microbiome (79, 80), potentially reducing the risk of several immune-mediated diseases such as allergies, asthma, and type 1 diabetes (80), increase connectedness to nature, and may decrease perceived stress and anger frequency (79). Children with greater independent mobility meet more often to play with their peers, schoolmates and neighbors than children with less independent mobility (risky play category disappear/get lost, see Table 1). Physical activity outdoors also includes active transportation to commuting to school or other places (81), either by walking or riding a bike. The percentage of children using active transportation to get to and from places differs greatly between and among countries. The more developed the countries are, the lower they score in active transportation of children. In developing countries, active transportation may be the result of a lack of access to public transport and motor vehicles, but highly developed countries scoring high in active transport of children provide both infrastructure and policy to support active transportation (15). Rough and tumble play (see Table 1) is associated with higher interpersonal cognitive problem-solving in boys, but not with increased aggression (55). And, while we are on the subject of misleading convictions: the assumption that leaving children indoors is safer than outdoors may be wrong considering the potential harms of the internet including online-violence, cyber-bullying, pornography or image based sexual abuse (82), increased sedentary time and unnecessary incidental eating (18). These facts—both the encouraging and concerning ones—call for action.

What can physiotherapists do that current and future generations of children—the world’s later adults—are able to live how they wish, to gain the experiences that they need, and can build nourishing relationships with their bodies, their peers, their neighborhood, and their natural environment?

3 How physiotherapists can contribute

Restricted opportunities for outdoor and risky play were discussed as having a potentially negative impact on children’s physical activity behavior (55). Therefore, increasing the amount of time children spend outdoors seems to be a promising strategy to increase their physical activity levels and to promote healthy, active lifestyles (16) that persist into adolescence and adulthood. Physiotherapists are equipped with essential knowledge about both optimal childhood development and how various pediatric conditions can affect a child’s growth across multiple domains—including motor function, sensory processing, cardiorespiratory function, cognitive skills, and socio-emotional wellbeing (30). They are trained to autonomously choose and use a range of assessment approaches and therapeutic interventions, tailored to the child’s age and stage of development, and provide guidance to caregivers on how to create safe(-as-necessary) environments for their children (19, 29, 83). Therefore, physiotherapists are predestined to spread the word about the benefits of risky play for optimal child development and health prevention, and tackling existing health issues (84) by including elements of risky play (see Table 1) into pediatric physiotherapy interventions, where appropriate.

Around the globe, physiotherapists are well-situated in reaching out to large groups of children and their caregivers, serving diverse communities including minority cultural groups, immigrants/refugees, persons living with disabilities, and gender-diverse communities. They can translate elements of risky play into various environments and cultures (69, 85), contributing to justice (86, 87) and pleasurable, positive experiences and achievements, which are valued by children and their caregivers (21). The International Organization of Physical Therapists in Pediatrics (IOPTP) firmly recommends that pediatric physiotherapy education programs include content focused on health promotion, injury prevention and physical fitness (30)—all realms positively influenced by risky play. In some countries, due to legal regulations or a culture of litigation, supervising adults are concerned about potential lawsuits, when stretching their own limits pertaining to risk-taking in child play (69, 88). Working collaboratively with caregivers, educators, and other health professionals, as well as policymakers, legislators, and other stakeholders in child health and safety, physiotherapists can inform about the benefits of risk-taking in physical activities, to change the negative perception of risk in children’s play (see Table 2) (83, 84, 89). For example, the promotion of better public understanding of risky play’s importance for children’s health and development can be done through public talks, conferences, and interdisciplinary discussions, helping society to better understand why risky play matters and by advocating for environments and conditions that support it.

Physiotherapists can initiate multidisciplinary research collaborations to investigate the health benefits of risky play in various community settings, environments and cultures, raising meaningful questions to find solutions for today’s burning questions in child health. To list only a few suggestions, future research could explore the perceptions of risky play among physiotherapists and allied health professions. The effects of risky play on children’s motor skills development and fitness levels could be compared to more traditional pediatric physiotherapy interventions by using randomized controlled trials. At times, pediatric physiotherapy interventions need to be provided from infancy through adolescence and even into adulthood. Not all interventions chosen are appreciated by children and their families, but sometimes perceived being boring or dull (21). In this light, it might be valuable to study children’s and their families’ adherence to and satisfaction with physiotherapy, when including risky play interventions.

Physiotherapy and risky play are environmentally friendly (90), safe, low-cost and effective ways (91, 92) to improve children’s health and well-being. Pooling both fields’ strengths can help to increase children’s awareness of the wonders of nature and life and to prepare them to accept future responsibilities towards communities, their personal health as well as planetary health (93). Nourishing a sense of belonging and connectedness (93), and reflecting on positive, playful ways of how we can build relationships and shape environments such as educational and health institutions, neighborhoods and playgrounds would be a good starting point for a healthy future worth living for humans and all other species (87).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EBHS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BS: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors thank the Health University of Applied Sciences Tyrol, Innsbruck, Austria, and the Government of Vorarlberg (IIb-13.06-10/2024-3/€ 300,-) for the funding of the article processing costs.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Sallis, JF, Bull, F, Guthold, R, Heath, GW, Inoue, S, Kelly, P, et al. Progress in physical activity over the Olympic quadrennium. Lancet. (2016) 388:1325–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30581-5

2. World Health Organisation. (2020). WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240015128 (Accessed May 24, 2024).

3. Siefken, K, Ramirez Varela, A, Waqanivalu, T, and Schulenkorf, N. Better late than never?! Five compelling reasons for putting physical activity in low-and middle-income countries high up on the public health research agenda. J Phys Act Health. (2021) 1–2:1469–72. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2021-0576

4. Alruwaili, BF, Bayyumi, DF, Alruwaili, OS, Alsadun, RS, Alanazi, AS, Hadi, A, et al. Prevalence and determinants of obesity and overweight among children and adolescents in the Middle East and North African countries: an updated systematic review. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. (2024) 17:2095–103. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S458003

5. World Health Organisation. (2024). Obesity and overweight. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. (Accessed May 16, 2024)

6. Aubert, S, Brazo-Sayavera, J, González, SA, Janssen, I, Manyanga, T, Oyeyemi, AL, et al. Global prevalence of physical activity for children and adolescents; inconsistencies, research gaps, and recommendations: a narrative review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2021) 18, 18:81. doi: 10.1186/s12966-021-01155-2

7. Calcaterra, V, and Zuccotti, G. Non-communicable diseases and rare diseases: a current and future public health challenge within pediatrics. Children. (2022) 9:1491. doi: 10.3390/children9101491

8. World Health Organisation. (2023). Global report on children with developmental disabilities. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240080232 (Accessed July 24, 2024).

9. Sando, OJ, Kleppe, R, and Sandseter, EBH. Risky play and children’s well-being, involvement and physical activity. Child Indic Res. (2021) 14:1435–51. doi: 10.1007/s12187-021-09804-5

10. Posadzki, P, Pieper, D, Bajpai, R, Makaruk, H, Könsgen, N, Neuhaus, AL, et al. Exercise/physical activity and health outcomes: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1724. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09855-3

11. Schuch, FB, and Vancampfort, D. Physical activity, exercise, and mental disorders: it is time to move on. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. (2021) 43:177–84. doi: 10.47626/2237-6089-2021-0237

12. Mazereel, V, Vansteelandt, K, Menne-Lothmann, C, Decoster, J, Derom, C, Thiery, E, et al. The complex and dynamic interplay between self-esteem, belongingness and physical activity in daily life: an experience sampling study in adolescence and young adulthood. Ment Health Phys Act. (2021) 21:100413. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2021.100413

13. World Health Organisation. (2021). WHO Discussion Paper on the development of an implementation roadmap 2023–2030 for the WHO Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2023–2030. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/implementation-roadmap-2023-2030-for-the-who-global-action-plan-for-the-prevention-and-control-of-ncds-2023-2030. (Accessed May 16, 2024)

14. Amann, M, König, S, and Sturm, A. Sicher und fit im Ländle. Inf Physio Austria. (2024) 2024:30–33.

15. Aubert, S, Barnes, JD, Abdeta, C, Nader, PA, Adeniyi, AF, Aguilar-Farias, N, et al. Global matrix 3.0 physical activity report card grades for children and youth: results and analysis from 49 countries. J Phys Act Health. (2018) 15:S251–73. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2018-0472

16. Gray, C, Gibbons, R, Larouche, R, Sandseter, EBH, Bienenstock, A, Brussoni, M, et al. What is the relationship between outdoor time and physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and physical fitness in children? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2015) 12:6455–74. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120606455

17. Summers, JK, Vivian, DN, and Summers, JT. The role of interaction with nature in childhood development: an under-appreciated ecosystem service. Psychol Behav Sci. (2019) 8:142–50. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7424505/

18. Tremblay, MS, Gray, C, Babcock, S, Barnes, J, Bradstreet, CC, Carr, D, et al. Position statement on active outdoor play. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2015) 12:6475–505. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120606475

19. van der, WJ, Plastow, NA, and Unger, M. Motor skill intervention for pre-school children: a scoping review. Afr J Disabil. (2020) 9:747. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v9i0.747

20. Malina, RM. Adherence to physical activity from childhood to adulthood: a perspective from tracking studies. Quest. (2001) 53:346–55. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2001.10491751

21. Waterworth, K, Gaffney, M, Taylor, N, and Gibson, BE. The civil rights of disabled children in physiotherapy practices. Physiother Theory Pract. (2021) 1–13. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2021.2011511

22. World Health Organisation. (2012). Implementing the merger of the ICF and ICF-CY—Background and proposed resolution for adoption by the WHO FIC Council. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/implementing-the-merger-of-the-icf-and-icf-cy---background-and-proposed-resolution-for-adoption-by-the-who-fic-council (Accessed December 11, 2024).

23. Ross, SM, Bogart, KR, Logan, SW, Case, L, Fine, J, and Thompson, H. Physical activity participation of disabled children: a systematic review of conceptual and methodological approaches in health research. Front Public Health. (2016) 4:187. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00187

24. International Play Association (IPA World). (2024). The child’s right to play. Available at: https://ipaworld.org/childs-right-to-play/the-childs-right-to-play/ (Accessed November 29, 2022).

25. 5Rights Foundation and Digital Futures Commission. (2021). It’s time for playful by design: free play in a digital world. Available at: https://digitalfuturescommission.org.uk/blog/its-time-for-playful-by-design-free-play-in-a-digital-world/ (Accessed May 24, 2024).

26. UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC). (2013). General comment No. 17 (2013) on the right of the child to rest, leisure, play, recreational activities, cultural life and the arts (art. 31). Available at: https://www.refworld.org/legal/general/crc/2013/en/96090 (Accessed July 23, 2024).

27. World Physiotherapy. (2023). Policy statement: autonomy. Available at: https://world.physio/policy/ps-autonomy (Accessed November 6, 2024).

28. Wengrovius, C, Miles, C, Fragala-Pinkham, M, and O’Neil, ME. Health promotion and physical wellness in pediatric physical therapy. Pediatr Phys Ther. (2024) 37:72–79. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0000000000001160

29. Rapport, MJ, Furze, J, Martin, K, Schreiber, J, Dannemiller, LA, DiBiasio, PA, et al. Essential competencies in entry-level pediatric physical therapy education. Pediatr Phys Ther. (2014) 26:7–18. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0000000000000003

30. Cech, D, Milne, N, and Connolly, B. (2019). Paediatric essential and recommended content areas in entry level professional physical therapy education statement. Available at: https://www.ioptp.org/copy-of-manipulation-mobilisation-s (Accessed October 30, 2024).

31. World Physiotherapy. (2023). Policy statement: climate change and health. Available at: https://world.physio/policy/policy-statement-climate-change-and-health (Accessed May 16, 2024).

32. United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (Accessed May 24, 2024).

33. Maric, F, and Nicholls, DA. Paradigm shifts are hard to come by: looking ahead of COVID-19 with the social and environmental determinants of health and the UN SDGs. Eur J Physiother. (2020) 22:379–81. doi: 10.1080/21679169.2020.1826577

34. Narain, S, and Mathye, D. Do physiotherapists have a role to play in the sustainable development goals? A qualitative exploration. South Afr J Physiother. (2019) 75:466. doi: 10.4102/sajp.v75i1.466

35. Rosenbaum, P, and Gorter, JW. The ‘F-words’ in childhood disability: I swear this is how we should think! Child Care Health Dev. (2012) 38:457–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01338.x

36. Rosenbaum, PL. The F-words for child development: functioning, family, fitness, fun, friends, and future. Dev Med Child Neurol. (2022) 64:141–2. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.15021

37. Sandseter, EBH. Characteristics of risky play. J Adventure Educ Outdoor Learn. (2009) 9:3–21. doi: 10.1080/14729670802702762

38. Tangen, S, Olsen, A, and Sandseter, EBH. A GoPro look on how children aged 17–25 months assess and manage risk during free exploration in a varied natural environment. Educ Sci. (2022) 12:361. doi: 10.3390/educsci12050361

39. Sandseter, EBH, Kleppe, R, and Sando, OJ. The prevalence of risky play in young children’s indoor and outdoor free play. Early Child Educ J. (2021) 49:303–12. doi: 10.1007/s10643-020-01074-0

40. Sandseter, EBH, Storli, R, and Sando, OJ. The dynamic relationship between outdoor environments and children’s play. Education 3-13. (2022) 50:97–110. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2020.1833063

41. Sandseter, EBH. Categorising risky play—how can we identify risk-taking in children’s play? Eur Early Child Educ Res J. (2007) 15:237–52. doi: 10.1080/13502930701321733

42. Kleppe, R, Melhuish, E, and Sandseter, EBH. Identifying and characterizing risky play in the age one-to-three years. Eur Early Child Educ Res J. (2017) 25:370–85. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2017.1308163

43. Smith, SJ. Risk and our pedagogical relation to children: on the playground and beyond. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press (1998). 220 p.

44. Transcript, GC. ‘Can run, play on bikes, jump the zoom slide, and play on the swings’: exploring the value of outdoor play. Australas J Early Child. (2004) 29:1–5. doi: 10.1177/183693910402900202

45. Stephenson, A. Physical risk-taking: dangerous or endangered? Early Years. (2003) 23:35–43. doi: 10.1080/0957514032000045573

46. Nikiforidou, Z. ‘It is riskier’: preschoolers’ reasoning of risky situations. Eur Early Child Educ Res J. (2017) 25:612–23. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2017.1331075

47. Little, H, and Wyver, S. Individual differences in children’s risk perception and appraisals in outdoor play environments. Int J Early Years Educ. (2010) 18:297–313. doi: 10.1080/09669760.2010.531600

48. Lavrysen, A, Bertrands, E, Leyssen, L, Smets, L, Vanderspikken, A, and De Graef, P. Risky-play at school. Facilitating risk perception and competence in young children. Eur Early Child Educ Res J. (2017) 25:89–105. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2015.1102412

49. CNAC Podcast. (2022). Accessibility, disability and risky play. Available at: https://childnature.ca/topic/accessibility-risky-play/. (Accessed November 30, 2022)

50. Canadian Paediatric Society. (2024). Healthy childhood development through outdoor risky play: navigating the balance with injury prevention. Available at: https://cps.ca/en/documents/position/outdoor-risky-play (Accessed May 24, 2024).

51. Brussoni, M.. (2023). Why children need risk, fear, and excitement in play. Available at: https://www.afterbabel.com/p/why-children-need-risk-fear-and-excitement (Accessed March 1, 2024).

52. Brussoni, M, Brunelle, S, Pike, I, Sandseter, EBH, Herrington, S, Turner, H, et al. Can child injury prevention include healthy risk promotion? Inj Prev. (2015) 21:344–7. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2014-041241

53. Sandseter, EBH, and Kennair, LEO. Children’s risky play from an evolutionary perspective: the anti-phobic effects of thrilling experiences. Evol Psychol. (2011) 9:257–84. doi: 10.1177/147470491100900212

54. Caprino, F. (2017). When the risk is worth it: the inclusion of children with disabilities in free risky play. Today’s Children, Tomorrow’s Parents. 40–47. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/41657926/WHEN_THE_RISK_IS_WORTH_IT_THE_INCLUSION_OF_CHILDREN_WITH_DISABILITIES_IN_FREE_RISKY_PLAY (Accessed June 13, 2022).

55. Brussoni, M, Gibbons, R, Gray, C, Ishikawa, T, Sandseter, EBH, Bienenstock, A, et al. What is the relationship between risky outdoor play and health in children? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2015) 12:6423–54. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120606423

56. Sandseter, EBHH, Kleppe, R, and Ottesen Kennair, LE. Risky play in children’s emotion regulation, social functioning, and physical health: an evolutionary approach. Int J Play. (2022) 12:127–39. doi: 10.1080/21594937.2022.2152531

57. Morgenthaler, T, Schulze, C, Pentland, D, and Lynch, H. Environmental qualities that enhance outdoor play in community playgrounds from the perspective of children with and without disabilities: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:1763. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20031763

58. Sandseter, EBH. Affordances for risky play in preschool: the importance of features in the play environment. Early Child Educ J. (2009) 36:439–46. doi: 10.1007/s10643-009-0307-2

59. Johnstone, A, Mccrorie, P, Cordovil, R, Fjørtoft, I, Iivonen, S, Jidovtseff, B, et al. Nature-based early childhood education and children’s physical activity, sedentary behavior, motor competence, and other physical health outcomes: a mixed-methods systematic review. J Phys Act Health. (2022) 19:456–72. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2021-0760

60. The Wild Network. (2017). Breaking down the barriers to wild time. Available at: https://thewildnetwork.com/inspiration/breaking-down-the-barriers-to-wild-time/ (Accessed August 4, 2024).

61. Haidt, J. The anxious generation: how the great rewiring of childhood is causing an epidemic of mental illness. Dublin: Penguin Random House (2024). 385 p.

62. Australian Physiotherapy Association. (2020). School is out for the year, time to get our kids engaged in more risky play for physical and cognitive development. Available at: https://australian.physio/media/school-out-year-time-get-our-kids-engaged-more-risky-play-physical-and-cognitive-development (Accessed November 22, 2022).

63. Physiopedia International. (2024). Boosting children’s health through risky outdoor play. Available at: https://members.physio-pedia.com/learn/boosting-childrens-health-through-risky-outdoor-play-promopage/. (Accessed May 24, 2024)

64. England Marketing. (2009). Childhood and nature: a survey on changing relationships with nature across generations. Available at: https://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/5853658314964992 (Accessed July 24, 2024).

65. Gill, T. No fear: growing up in a risk averse society. London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation (2007).

66. Alvarez, EN, Garcia, A, and Le, P. A review of nature deficit disorder (NDD) and its disproportionate impacts on Latinx populations. Environ Dev. (2022) 43:100732. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2022.100732

67. Chaput, JP, Tremblay, MS, Katzmarzyk, PT, Fogelholm, M, Mikkilä, V, Hu, G, et al. Outdoor time and dietary patterns in children around the world. J Public Health Oxf Engl. (2018) 40:e493–501. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdy071

68. Bassett, DR, John, D, Conger, SA, Fitzhugh, EC, and Coe, DP. Trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviors of United States youth. J Phys Act Health. (2015) 12:1102–11. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0050

69. Little, H, Sandseter, EBH, and Wyver, S. Early childhood teachers’ beliefs about children’s risky play in Australia and Norway. Contemp Issues Early Child. (2012) 13:300–16. doi: 10.2304/ciec.2012.13.4.300

70. Colliver, Y, Harrison, LJ, Brown, JE, and Humburg, P. Free play predicts self-regulation years later: longitudinal evidence from a large Australian sample of toddlers and preschoolers. Early Child Res Q. (2022) 59:148–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.11.011

71. Greve, W, and Thomsen, T. Evolutionary advantages of free play during childhood. Evol Psychol. (2016) 14:1474704916675349. doi: 10.1177/1474704916675349

72. Shaheen, S. How child’s play impacts executive function-related behaviors. Appl Neuropsychol Child. (2014) 3:182–7. doi: 10.1080/21622965.2013.839612

73. Tchombe, TMS, Nsamenang, AB, Keller, H, and Fülöp, M. Cross-cultural psychology: an Africentric perspective. Limbe, CM: DESIGN House (2013).

74. Caneiro, JP, Bunzli, S, and O’Sullivan, P. Beliefs about the body and pain: the critical role in musculoskeletal pain management. Braz J Phys Ther. (2021) 25:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2020.06.003

75. Slater, D, Korakakis, V, O’Sullivan, P, Nolan, D, and O’Sullivan, K. “Sit up straight”: time to re-evaluate. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. (2019) 49:562–4. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2019.0610

76. Sandseter, EBH. Risky play and risk management in Norwegain preschools—a qualitative observational study. Saf Sci Monit. (2009) 13:1–12.

77. Little, H, and Stapleton, M. Exploring toddlers’ rituals of “belonging” through risky play in the outdoor environment. Contemp Issues Early Child. (2023) 24:281–97. doi: 10.1177/1463949120987656

78. Fjørtoft, I. Landscape as playscape: the effects of natural environments on children’s play and motor development. Child Youth Environ. (2004) 14:21–44. doi: 10.1353/cye.2004.0054

79. Sobko, T, Liang, S, Cheng, WHG, and Tun, HM. Impact of outdoor nature-related activities on gut microbiota, fecal serotonin, and perceived stress in preschool children: the play & grow randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:21993. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78642-2

80. Roslund, MI, Puhakka, R, Nurminen, N, Oikarinen, S, Siter, N, Grönroos, M, et al. Long-term biodiversity intervention shapes health-associated commensal microbiota among urban day-care children. Environ Int. (2021) 157:106811. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106811

81. Toner, A, Lewis, JS, Stanhope, J, and Maric, F. Prescribing active transport as a planetary health intervention—benefits, challenges and recommendations. Phys Ther Rev. (2021) 26:159–67. doi: 10.1080/10833196.2021.1876598

82. Barker, K, and Jurasz, O. Digital and online violence: international perspectives. Int Rev Law Comput Technol. (2024) 38:115–8. doi: 10.1080/13600869.2023.2295088

83. Brussoni, M. Promoting risky play: insights from the outside play lab. Open Access Gov. (2024) 43:36–7. doi: 10.56367/OAG-043-11459

84. Beaulieu, E, and Beno, S. Healthy childhood development through outdoor risky play: navigating the balance with injury prevention. Paediatr Child Health. (2024) 29:255–61. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxae016

85. Lee, EY, de Lannoy, L, Li, L, de Barros, MIA, Bentsen, P, Brussoni, M, et al. Play, learn, and teach outdoors-network (PLaTO-Net): terminology, taxonomy, and ontology. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2022) 19:66. doi: 10.1186/s12966-022-01294-0

86. Caryl, F, McCrorie, P, Olsen, JR, and Mitchell, R. Use of natural environments is associated with reduced inequalities in child mental wellbeing: a cross-sectional analysis using global positioning system (GPS) data. Environ Int. (2024) 190:108847. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2024.108847

87. Maric, F, and Nicholls, DA. Environmental physiotherapy and the case for multispecies justice in planetary health. Physiother Theory Pract. (2021) 38:2295–306. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2021.1964659

88. Kvalnes, Ø, and Sandseter, EBH. Risky play: an ethical challenge. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan (2023). 113 p.

89. Liu, J, and Birkeland, Å. Perceptions of Risky play among kindergarten teachers in Norway and China. Int J Early Child. (2022) 54:339–60. doi: 10.1007/s13158-021-00313-8

90. Astell-Burt, T, Pappas, E, Redfern, J, and Feng, X. Nature prescriptions for community and planetary health: unrealised potential to improve compliance and outcomes in physiotherapy. J Physiother. (2022) 68:151–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2022.05.016

91. Smith-Turchyn, J, Richardson, J, Sinclair, S, Xu, Y, Choo, S, Gravesande, J, et al. Cost effectiveness of physiotherapy services for chronic condition management: a systematic review of economic evaluations conducted alongside randomized controlled trials. Physiother Can. (2023):e20220016. doi: 10.3138/ptc-2022-0016

92. Canadian Physiotherapy Association. (2024). Physiotherapy could save Canada millions of dollars. Available at: https://physioisforeveryone.ca/impact-studies/ (Accessed August 4, 2024).

93. Chawla, L. Childhood nature connection and constructive hope: a review of research on connecting with nature and coping with environmental loss. People Nat. (2020) 2:619–42. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10128

Keywords: physiotherapy, environmental, child health, public health, risky play, physical therapy, pediatric

Citation: Sturm A, Sandseter EBH and Scheiber B (2025) Environmental pediatric physiotherapy and risky play: making the case for a perfect match. Front. Public Health. 12:1498794. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1498794

Edited by:

Berta Paz-Lourido, University of the Balearic Islands, SpainReviewed by:

Seçil Cengizoğlu, Atılım University, TürkiyeMarina Perelló-Díez, University of the Balearic Islands, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Sturm, Sandseter and Scheiber. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea Sturm, YW5kcmVhLnN0dXJtQGZoZy10aXJvbC5hYy5hdA==

Andrea Sturm

Andrea Sturm Ellen Beate Hansen Sandseter

Ellen Beate Hansen Sandseter Barbara Scheiber1

Barbara Scheiber1