94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health, 18 December 2024

Sec. Public Health Education and Promotion

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1498406

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Role of Nursing in Public Health Promotion and EducationView all 31 articles

Lammi Atomsa1*

Lammi Atomsa1* Sidise Temesgen1

Sidise Temesgen1 Abebe Dechasa2

Abebe Dechasa2 Mulatu Ayana2

Mulatu Ayana2 Nimona Amena2

Nimona Amena2 Dawit Teklehymanot3

Dawit Teklehymanot3 Firaol Regea1

Firaol Regea1Introduction: Preoperative teaching is fundamental nursing activity in which a nurse educates the patient about surgery and what to anticipate following the procedure. It is a process via which nurses give standard preoperative information to patients before surgery, and it enables the patients to understand their diagnosis and treatment, actively participate in their own care, overcome feelings of incapacity in relation to their condition, regain health, and maintain home care. However, there is a dearth of studies that determine the extent of preoperative teaching practice in Ethiopia in general and in the study area in particular.

Objective: This study aimed to assess preoperative patient teaching practices and the factors associated with these practices among nurses working in hospitals in the West Shoa, Oromia region, Ethiopia, in 2022.

Methods: An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 267 nurses from 1 September to 30 September 2022, at hospitals in the West Shoa Zone. Two-stage simple random sampling technique was used to select study participants. Data were collected using a pretested and structured self-administered questionnaire. The quantitative data were checked and entered using Epi-data version 4.6 and exported to SPSS version 26.0 for analysis. Bivariable and multivariable logistic analyses were performed, and p-values of <0.05 at a 95% confidence interval were considered statistically significant.

Result: A total of 253 nurses returned the entire questionnaire, yielding a response rate of 94.75%. The study enrolled 132 (52.2%) male, the highest percentage (231, 91.3%) of the participants were in the age group of 18–35, the majority of participants (152, 60.1%) were married, and 164 (64.8%) were protestant. Approximately 101 (39.9%) participants demonstrated good preoperative teaching practice. Lack of teaching material, lack of training workload, time constraints, insufficient staffing, language barrier, severity of patient cases, patient and family’s anxiety, and complexity of patients’ status were significantly associated with preoperative patient teaching practice.

Conclusion: The proportion of preoperative patient teaching practices among nurses working at hospitals in the West Shoa Zone was low. Concerned bodies should emphasize ways to improve preoperative teaching practice.

The preoperative period is the time between the decision to have surgery and the patient’s transport to the operating room (1). The preoperative period is one of the most stressful times, resulting in mild-to-severe anxiety (2, 3). Patient teaching, as part of professional nurses’ educational responsibilities, ensures that healthy knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and habits are learned by both healthy and sick individuals. Today’s patient teaching has lately moved from a concentration on sickness pathophysiology and treatment to one that encompasses disease prevention, patient development, and patients family care, as well as their engagement in care management (4).

Patients awaiting anesthesia and surgery are more likely to experience worry and fear (5). The prevalence of preoperative anxiety, reported in previous studies, was 60–80% of which 59.6% of them are afraid that they will not recover from anesthesia; 53.9% are afraid of mortality, dependency, and impairment; 51.7% are afraid of postoperative pain; and 43.3% are worried about their families (6, 7).

Preoperative anxiety is a psychological condition that frequently precedes surgery and may have a negative impact on the postoperative outcome (8). Patient with preoperative anxiety might have operation-related complication such as increased autonomic nerve fluctuations, a greater need for anesthesia, a higher risk of nausea and vomiting, and increased postoperative pain. Reports state that these issues may extend the length of the hospital stay and the rehabilitation period (8, 9).

Preoperative teaching is a process via which nurses give standard preoperative information to patients before surgery (10). Preoperative teaching enables the patients to understand their diagnosis and treatment, actively participate in their own care, overcome feelings of incapacity in relation to their condition, regain health, and maintain home care (11).

The main topics about which patients and their relatives should be informed before an operation are preoperative diagnosis, preparation, treatment, duration of operation, material to be used, frequency and duration of relatives’ visits, location of relatives’ waiting room, method of communication and how to share information with staff on the postoperative ward, and tubes to be inserted to the patient (12).

Preoperative teaching is crucial for alleviating fear and anxiety about surgery, relieving patient concerns, and preventing postoperative problems (13). It is also important to help clients better comprehend their surgical treatment, feel more in control, experience less postoperative discomfort and anxiety, spend less time in the hospital, and recover quickly (14). In addition, effective preoperative teaching could save approximately 5.7 million US$ cost of postoperative period per year (15).

Failure to provide adequate preoperative information causes anxiety, fear of pain, and uncertainty about the future, depression, anger, and inability to perform personal functions after the operation. As a result, both the risk of complications and length of hospital stay increase (3, 16). In this regard, all healthcare providers, particularly nurses, should recognize that the patient requires information on the procedures that occur before, during, and after the operation and incorporate preoperative education into patient care (17).

Recent studies reported that the level of preoperative teaching varies on different continents of the world and that implementation is low in developing countries (18–21). Some studies revealed that most of the nurses have a good knowledge of preoperative patient teaching and a positive attitude toward it, and those studies found a significant gap between knowledge and practice among the study participants. According to these studies, although the nurses have good knowledge, their practice is poor (22).

Considering preoperative teaching as a major duty of nurse professionals, investigating the extent of its practice found it to be one factor that has received little attention in various countries, including Ethiopia (23). To the best of our knowledge, few studies have assessed the practices and associated factors of preoperative patient teaching in Ethiopia. Thus, the researchers intended to assess preoperative patient teaching practice and associated factors among nurses working at hospitals in the West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia.

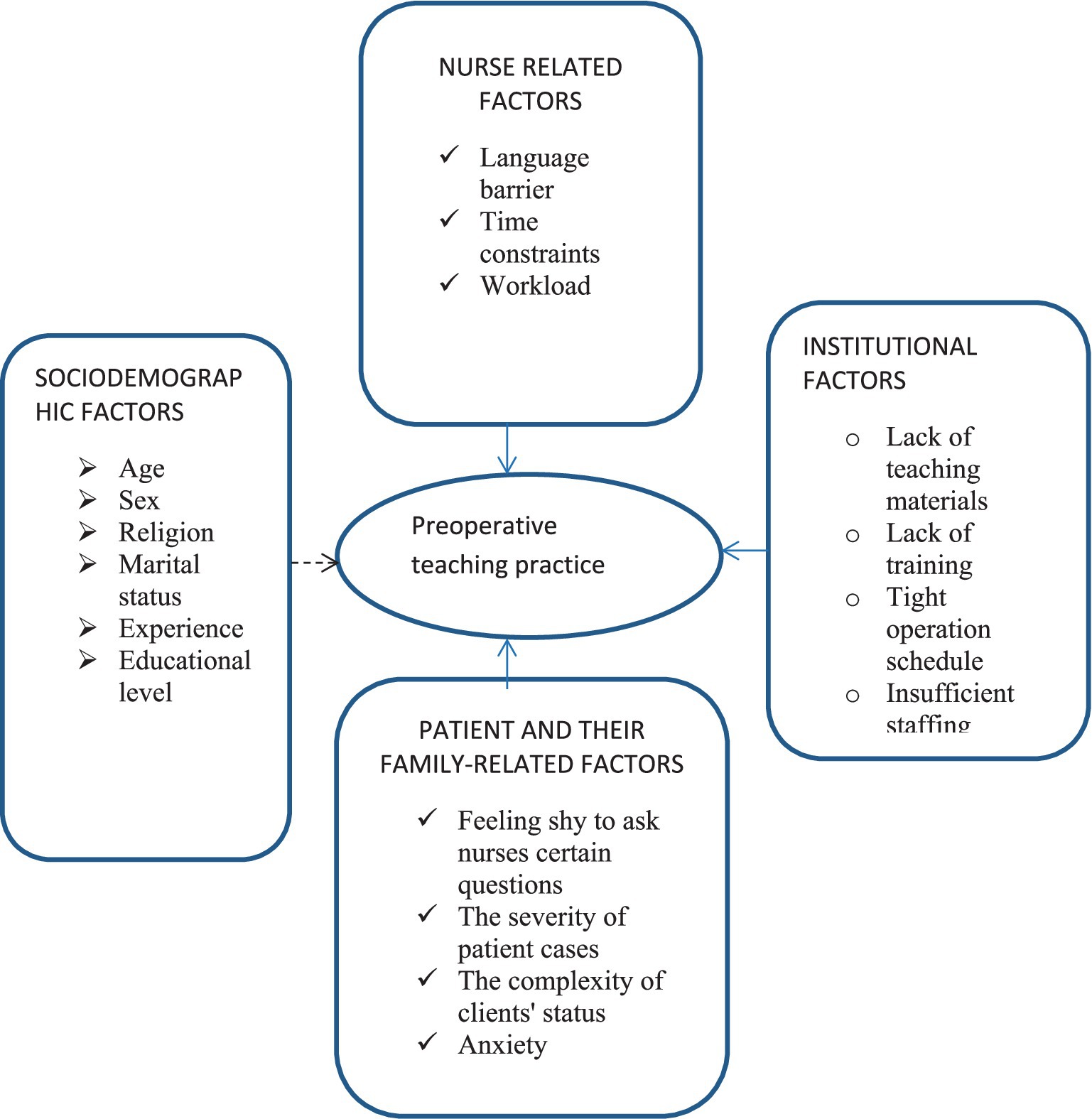

The conceptual framework was developed based on the review of different studies. Factors such as sociodemographic factors, nurse-related factors, institutional-related factors, and patient- and family-related factors are those determinant factors which can affect the preoperative teaching practice either proximally, intermediately, or distally (12, 14, 24–27) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Developed conceptual framework for preoperative teaching practice and associated factors among nurses working at hospitals in West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia, 2022.

The general objective of the study was to assess preoperative patient teaching practices and the factors associated with these practices among nurses working in hospitals in the West Shoa, Oromia region, Ethiopia, in 2022. The specific objectives the study are to determine the level of preoperative patient teaching practice and identify factors associated with preoperative patient teaching practices among nurses working at hospitals in the West Shoa Zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia, respectively.

The study was conducted from 1 September to 30 September 2022, at hospitals in the West Shoa Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022. The zone now has nine hospitals, including primary, secondary, and tertiary hospitals. All hospitals provide surgical services to patients.

The research questions and study design were created by the investigators, who then got them approved by the Ambo University’s institutional review board. None of the participants in this study were involved in its design, implementation, or dissemination techniques.

An institution-based quantitative cross-sectional study was employed.

The study’s source population consists of all nurses working in hospitals located in the West Shoa Zone. The study’s population consists of all sampled nurses who work in selected hospitals in the study area and coincide with the inclusion criteria. Individual nurses working at chosen hospitals in the study area were the study’s unit.

Nurses available during the data collection period who volunteered to participate were included in the study. Specialty nurses (such as psychiatry nurses, ophthalmologic nurses, and emergence and critical care nurses) were excluded because they were not assigned to the surgical ward or operating room during nursing rotation was excluded from the study.

Sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula by the following assumptions: Z = the standard normal deviation at a 95% confidence interval = 1.96 and d = margin of error that can be tolerated, 5% (0.05). The sample size was calculated by assuming p 0.5(50%) since there are no similar studies being conducted in Ethiopia.

However, because this is population of <10,000, the corrected sample size was calculated using the following formula:

where

• N = total number of nurses at hospitals in West Shoa Zone =657

• n = desirable sample size required for the study

• Z (α/2) = the critical value at 95% level of significance (1.96)

• P = proportion of nurses who demonstrate good preoperative teaching practices

• d = margin of error (5%).

Assuming 10% non-response rate, the final sample size was 267.

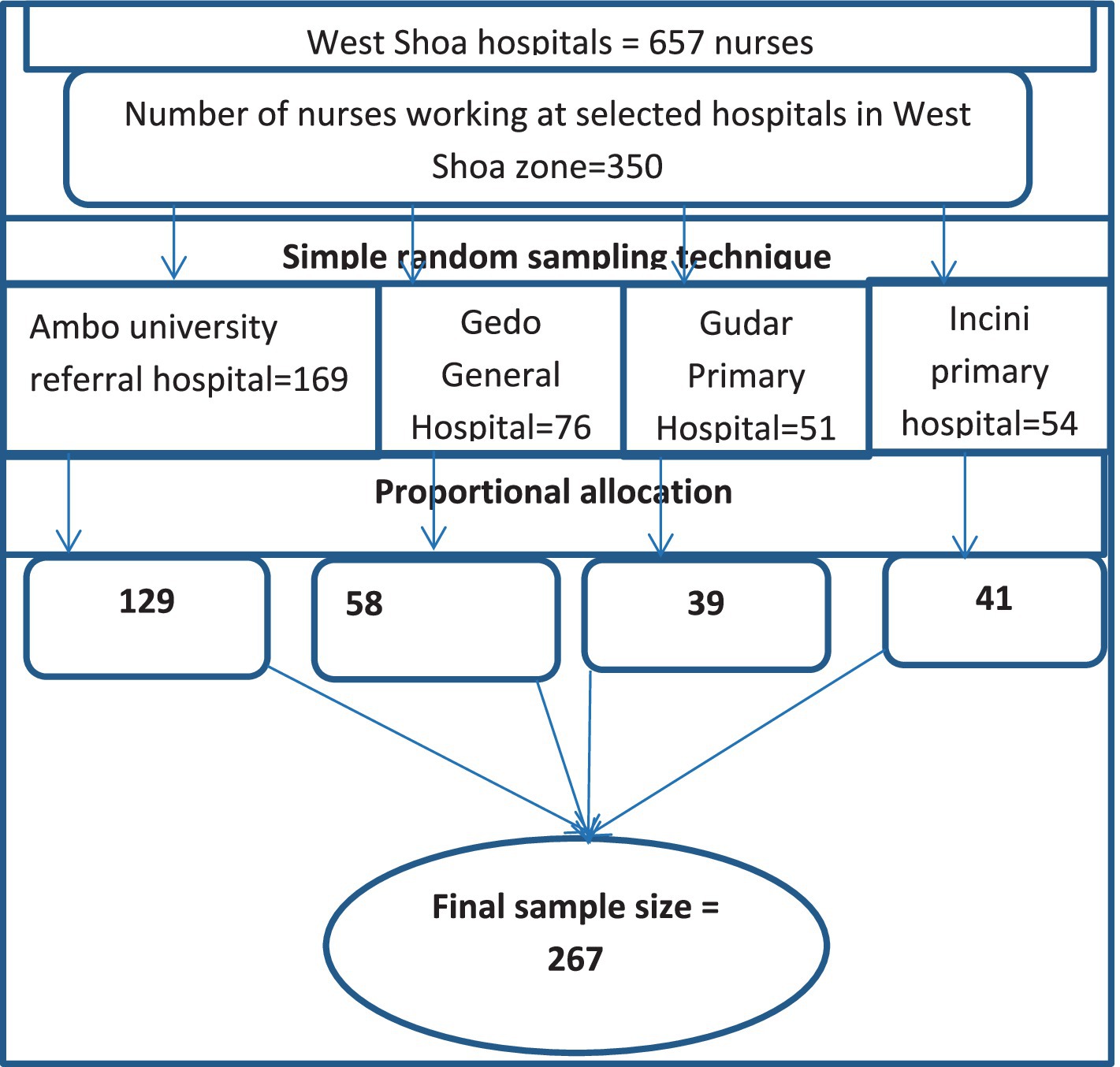

From a total of nine hospitals, four were selected to participate (Ambo University Referral Hospital, Gedo General Hospital, Incini Primary Hospital, and Gudar Primary Hospital) by simple random sampling technique. Next, sample size was proportionally allocated to the selected hospitals based on the number of nurses. Finally, simple random sampling method was used to select proportionally allocated study participants from each hospital using the lottery method.

Proportional allocation was calculated using the following formula:

where

• ni = the sample size of i th hospital

• n = n1 + n2 + …n4 is the total sample size

• Ni = the population size of i th hospital

• N = N1 + N2 + N3 + N4 is total hospital population (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic representation of sampling technique for preoperative patient teaching practice and associated factors among nurses working at hospitals in West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia, 2022.

Simple random sampling technique was used to select study participants.

Independent variable of study was preoperative teaching practice.

Independent variables of study were as follows:

Sociodemographic factors: age, sex, marital status, religion, work experience, and educational level.

Institutional factors: lack of teaching materials, lack of training, tight operation schedule, and insufficient staffing.

Nurse-related factors: workload, language barrier, and time constraints.

Patient- and family-related factors: feeling too shy to ask nurses certain questions, severity of patient cases, complexity of clients’ health status, and anxiety.

Good preoperative teaching practice: The participants answered “always” to all practice questions (14, 28, 29).

Poor preoperative teaching practice: Participants did not reply “always” to all practice questions.

A structured self-administered questionnaire was used to collect the necessary data from study participants. The questionnaire was adapted after reviewing different articles (10, 12, 14, 25, 30–32) and comprised three sections: The first section concerned the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, and the second part consists of a Likert scale designed to measure nurses preoperative teaching practice. The third section consisted of a Likert scale designed to measure perceived barrier to preoperative education. The two-point Likert scale is the simplest Likert scale question, for example, where there will be just two Likert options, such as agree and disagree as two poles of the scale. It is typically used to measure agreement. Because we intended to assess their agreement on such barriers, we used two-point Likert scales. The scale consisted of 11 questions to which participants responded either (Agree = 1 or Disagree = 2). One supervisor and four data collectors with BSc degree in nursing were recruited for data collection process. Prior to administering the questionnaire, the data collectors informed the study participants about the purpose of the study data collectors devoted as much time as possible to encouraging participants to respond to all items in the questionnaire.

One week before actual data collection, the questionnaire was pretested on 5% of the total sampled population working at Holeta Hospital to check clarity and consistency and make necessary amendments. Any ambiguity, confusion, difficult words, or differences in understanding were revised based on the pretest experience. The consistency and reliability of this survey were measured by Cronbach’s alpha which was 0.94 and 0.803 for the practice and barriers questions, respectively. Before the actual data collection period, supervisors and data collectors were oriented on the objective of the study, the questionnaire and extent of explanations, and the way to maintain privacy and confidentiality. The supervisor and investigators coordinated the data collection process.

To ensure data quality, training was provided to the data collectors and supervisor on the study objectives and questionnaires. The data collectors were supervised by the supervisor, and the investigator received a daily report. All data were checked for completeness and consistency by the investigator and supervisors on the day of data collection. Double data entry was performed to ensure the quality of data; data were intensively cleaned before analysis.

The data were coded and entered using Epi-data version 4.6 and exported to SPSS version 26.0. Categorical variables are summarized as frequencies and percentages. To measure the association between the outcome and independent variables, adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence interval were calculated. To identify factors associated with the outcome variable, a bivariate logistic regression analysis was first performed for one independent variable with the outcome variable. Variables with a p-value of less than 0.25 were considered potential candidates for multivariable logistic analysis. The multi-collinearity test was performed with a variance inflation factor (VIF), with maximum of 1.2. Model goodness of fit was tested using Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. A forward stepwise (likelihood ratio) method was used. Statistical significance was declared for variables with a p-value of less than 0.05.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review board (ERB) of Ambo University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences. Subsequently, a supporting letter was sent to all hospitals to conduct this research in the hospitals that were involved in this research, and written consent was obtained from respondents before data collection. All study participants were informed about the purpose of the study and their right to participate and were assured that their names would not be visible on their responses to the questionnaire to maintain their confidentiality.

A total of 253 nurses were returned completed questionnaire making a response rate of 94.75%. The study enrolled 132 (52.2%) male, most participants (231, 91.3%) were in the18–35 age group, the majority (152, 60.1%) were married, and 164 (64.8%) were protestant. The majority (210, 83.0%) of respondents had a Bachelor of Science in nursing, and 181 (78.5%) had worked in the nursing profession for 9 years or less (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of selected nurses working at hospitals in West Shoa, Ethiopia, 2022.

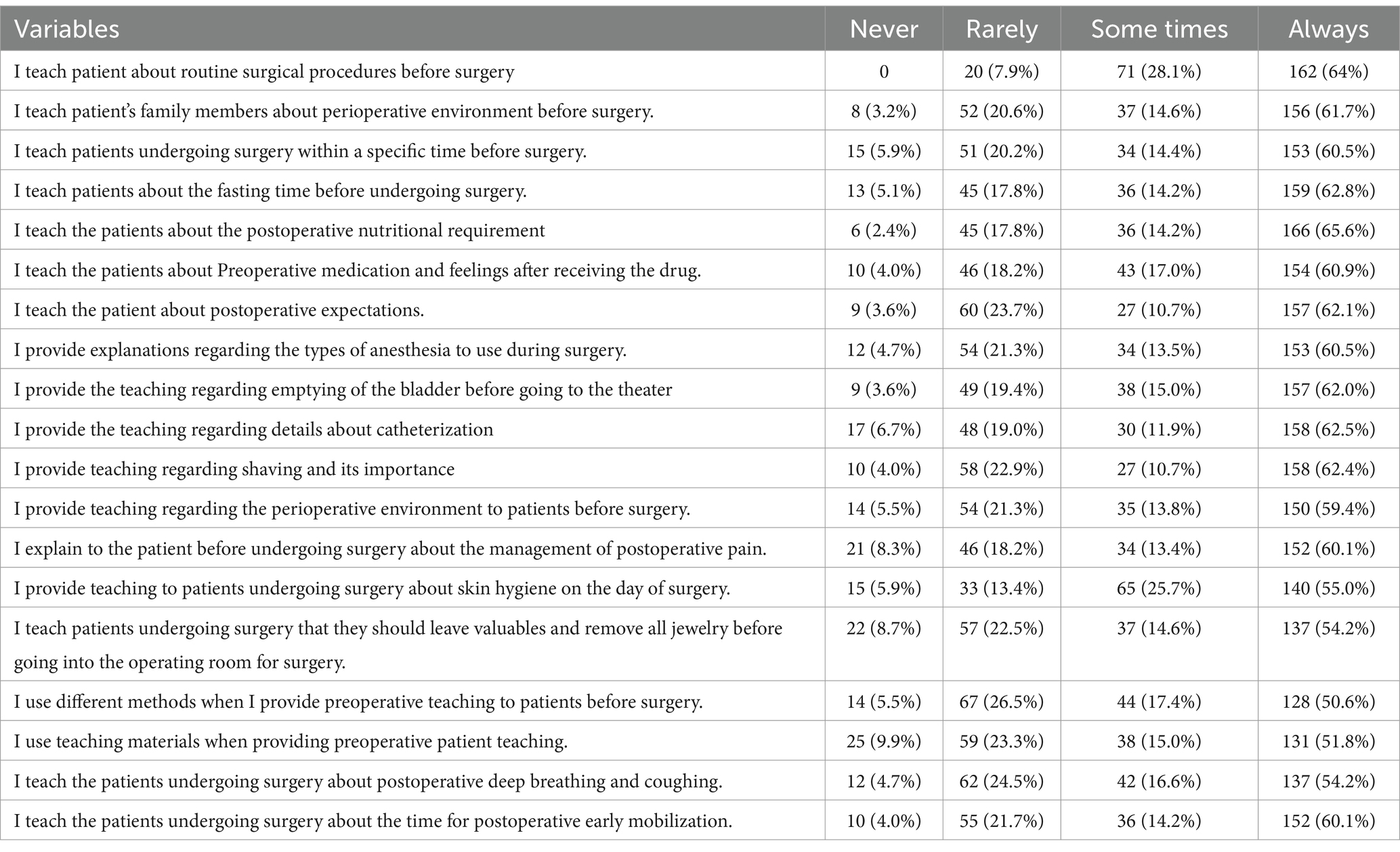

Among 253 participants, the majority (162, 64%) always taught the patients about routine surgical procedures before surgery; 52 (20.2%) rarely taught patient’s family members before surgery; 153 (60.5%) taught patients within specific time period before surgery; and 159 (62.8%) always taught patients about preoperative fasting before undergoing surgery. Approximately 50.6% of participants always use different methods when they provide preoperative teaching to patients before surgery. Approximately 166 (65.6%) of participants always informed the patients about the postoperative dietary requirements. Approximately 153 (60.5%) of survey participants always explained the forms of anesthetic to be used before surgery. 157 (62.0%) individuals offer instruction on bladder emptying before going to the theater.

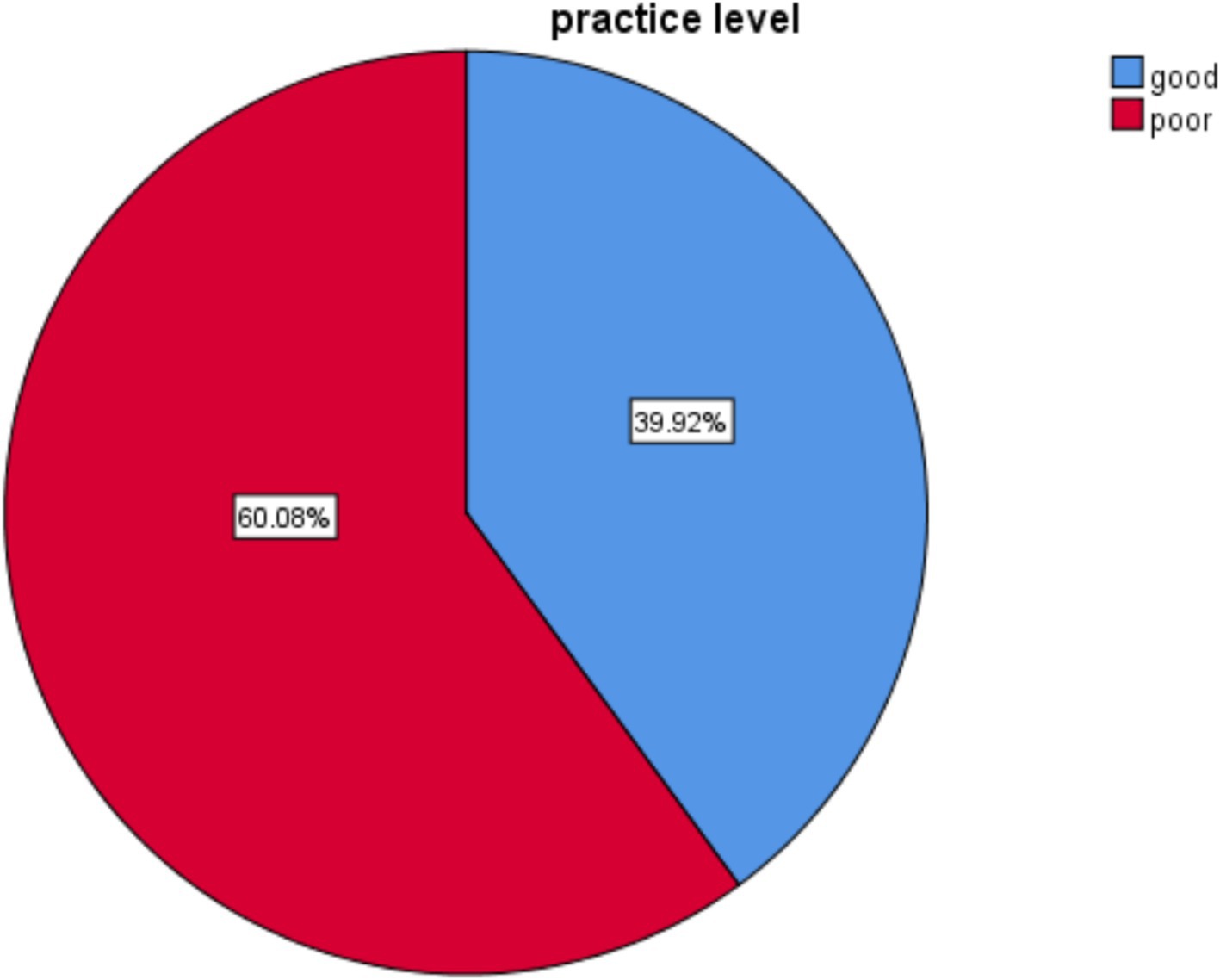

Of participants, 101 (39.9%; 95% CI: 33, 46) responded ‘Always’ to all 19 questions, demonstrating that they followed good practice. The remaining (132, 60.1% with 95% CI: 54, 66) participants demonstrate that they followed poor practice (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Level of practice on preoperative patient teaching among nurses working at hospitals in West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia, 2022.

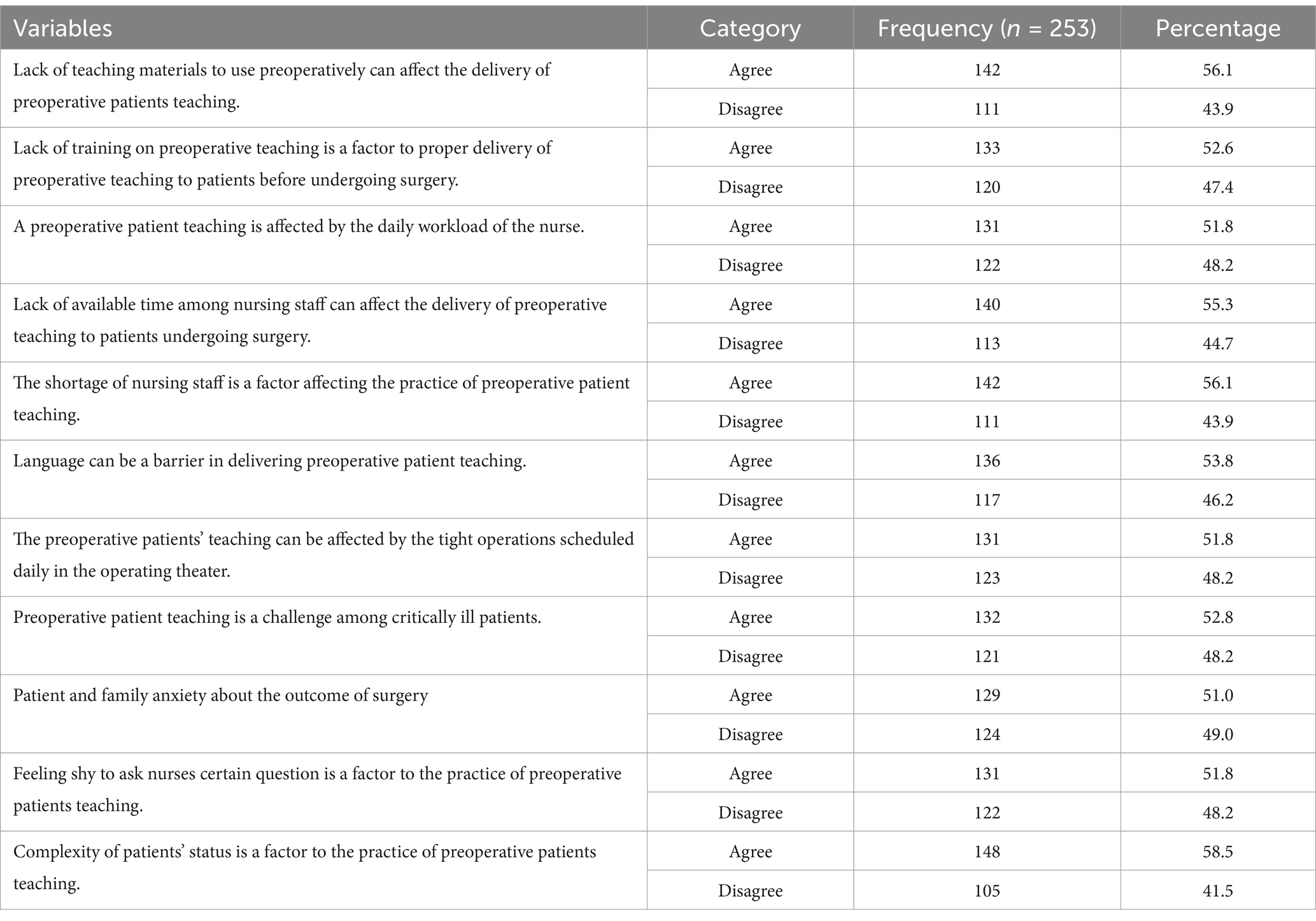

Among 253 participants, almost 148 (58.5%) of study participants agreed that the complexity of patients’ status influences the practice of preoperative patient teaching practice. The majority (142, 56.1%) agreed that lack of teaching materials used for preoperative teaching could affect the delivery of preoperative patient teaching. More than half (133, 52.6%) agreed that lack of training is a factor affecting delivery of preoperative education to patients before undergoing surgery, 131 (51.8%) agreed that it was affected by the daily workload of the nurse, and approximately 140 (55.3%) agreed that lack of time among nursing staff could also affect delivery. The majority (142, 56.1%) agreed that shortage of nursing staff was a factor affecting the practice of preoperative patient teaching. Almost all (148, 58.5%) of study participants agreed that the complexity of patients’ status influences the practice of preoperative patient teaching practice (Table 2).

Table 2. Perceived barriers of preoperative patient teaching practice among nurses working at hospitals in West Shoa, Ethiopia, 2022.

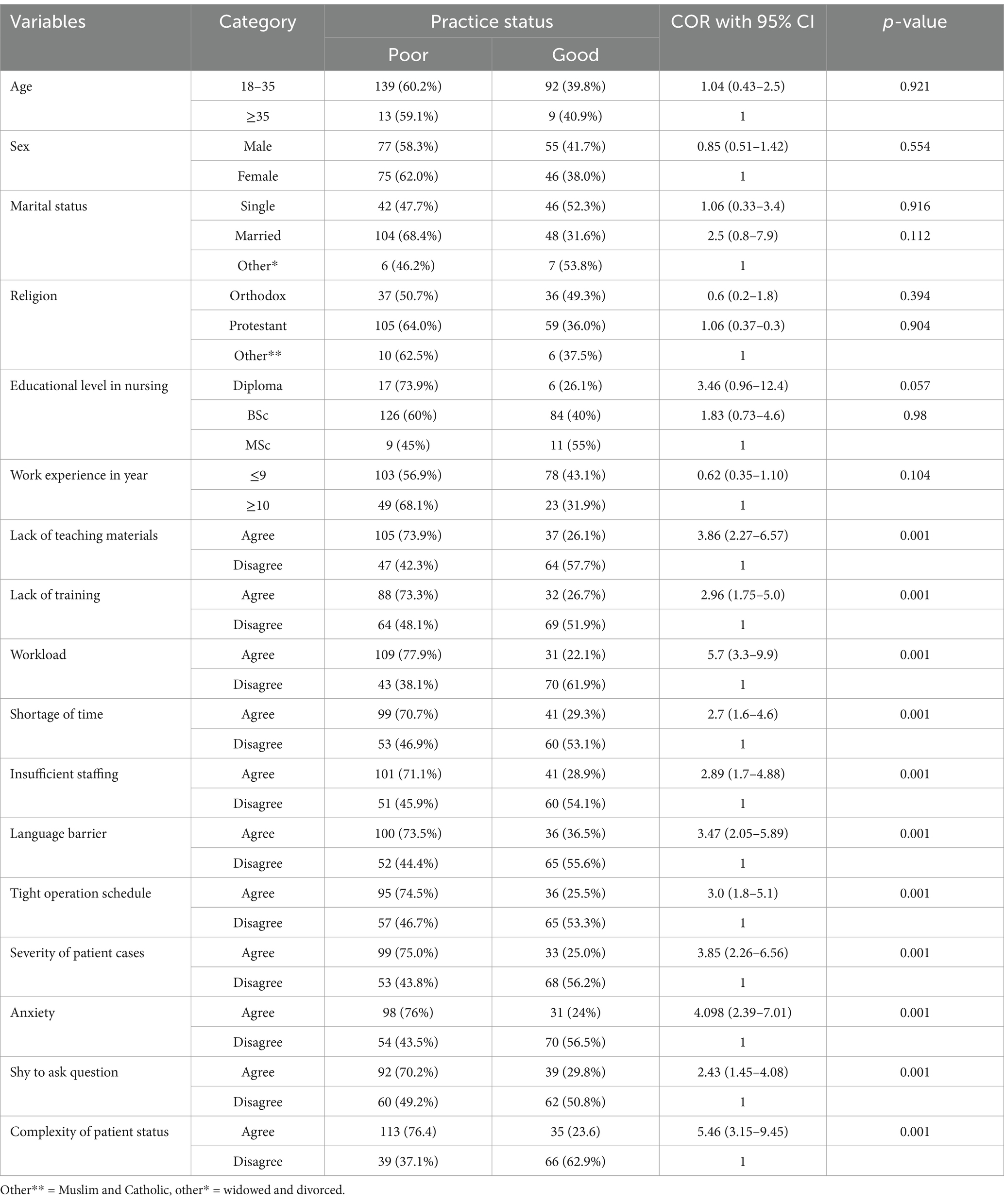

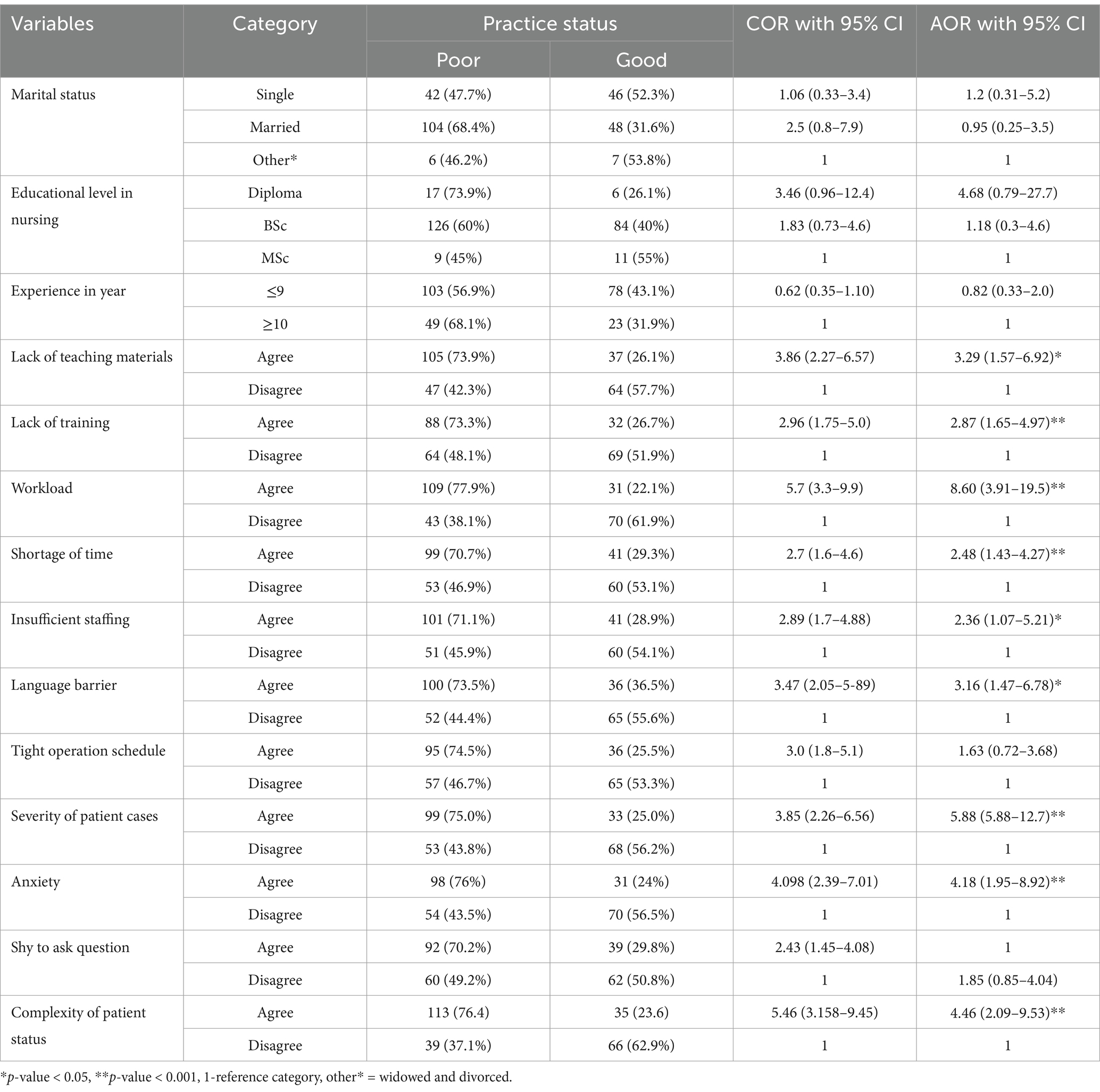

To assess the factors associated with nurses’ preoperative patient teaching practice, a bivariate analysis was performed. Accordingly, marital status, educational level, work experience, lack of teaching materials, lack of training, workload, time constraints, insufficient staffing, language barrier, tight operation schedule, severity of patient cases, anxiety, feeling too shy to ask questions, and complexity of patient status were significantly associated with nurses preoperative teaching practice (0.25). Variables associated with the dependent variable (p-value <0.25) were selected and subjected to multivariate logistic regressions analysis (Tables 3, 4).

Table 3. Bivariable logistic regression result of factors associated with preoperative teaching practice among nurses working at West Shoa, Ethiopia, 2022.

Table 4. Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression result of factors associated with preoperative teaching practice among nurses working at West Shoa, Ethiopia, 2022.

After adjusting for nine variables, the lack of teaching materials, lack of training, workload, time constraints, shortage of nurses, language barrier, severity of patient cases, anxiety, and complexity of patients’ status were significantly associated with nurses’ preoperative teaching practice (Table 5).

Table 5. Preoperative patient teaching practice among nurses working at hospitals in West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia, 2022.

In this study, we attempted to identify preoperative patient teaching practice and associated factors among nurses working at hospitals in West Shoa Zone. According to this study, 60.1% of study participants demonstrated poor preoperative patient teaching practices. Factors such as lack of teaching materials, lack of training, workload, time constraints, insufficient staffing, language barrier, severity of patient cases, patient and family’s anxiety, and complexity of patients’ status were statistically associated with preoperative patient teaching practice.

This finding is in line with studies conducted in East Amhara and Northwest Amhara Comprehensive Specialized Referral Hospitals, that is, only 61.5 and 53.7% of nurses, respectively, were found to demonstrate poor practices in delivering preoperative patient education. The similarities might be due to the study setting, the study population, sociodemographic traits, and curriculum.

This result is again supported by the studies conducted in Nigeria which revealed a positive attitude to patients’ preoperative education; however, the practice was not effective (33). Despite differences in socioeconomic status and level of health sector development, the current study and the Nigerian study may be similar due to the use of a similar study population (staff nurse) and study design. This is also in agreement with a study conducted in Gamo and Gofa, southern Ethiopia which revealed that only 36.6% of patients received good quality preoperative education (34).

However, this finding is better than that of study conducted in China which revealed that 46.5% of nurses did not provide all necessary preoperative information to patients (10). This inconsistency might be due to socioeconomic differences between the two countries. The results of our study are better than those of a study conducted in Cyprus which revealed that approximately 88.8% of nurses offered preoperative patient education and only 11.2% offered none (12). This discrepancy might be due to the nurse-to-patient ratio, training, and use of different data collection tool. Study conducted in Iran also revealed worse results than ours: 84.9% of nurses always educate their patients, and 15.1% do not always educate their patients (28). The socioeconomic differences between those two countries may be the cause of this discrepancy.

On the other hand, this result is lower than that of study conducted in Rwanda, which found that 97.3% of nurses demonstrate poor preoperative patient teaching practices (14). This discrepancy might be due to study setting, sample size, or educational level of nurses since most Rwandan nurses were diploma holders rather than BSc holders as was the case in our current study.

The findings of the current study revealed that lack of teaching materials was significantly associated with nurses’ preoperative teaching practices. Respondents who agreed that lack of teaching material affect preoperative patient teaching practice were three times more likely to demonstrate poor practice than their counterparts. This study is comparable with a study conducted in China and Rwanda which revealed that limited teaching resources affected preoperative teaching provided to surgical patients (10, 14). A possible explanation could be that the scarcity of teaching materials in both developed and developing nations has a negative impact on delivery of preoperative education.

Study showed that lack of training was significantly associated with nurses’ preoperative teaching practice and respondents who agreed this was a factor practicing preoperative teaching were three times more likely to demonstrate poor practice compared to those who disagreed. This result is supported by study conducted in China and Nigeria which showed that a lack of training is among the top factors affecting preoperative education provided for surgical patients (10, 27). This can be related to the increased knowledge of operation details and specific perioperative care gained from attending relevant surgical training courses; as a result, they were much more eager and satisfied to use their newly acquired knowledge to teach and provide more preoperative information to patients. This suggests that the responsible bodies are prepared to deliver service and in-service training programs for nurses on preoperative patient teaching practice based on the most recent evidence-based global and national recommendations. Similarly, work load was among the variables significantly associated with nurses’ preoperative teaching practice and those who agreed that workload is a factor in practicing preoperative teaching were 8.6 times more likely to demonstrate poor practice compared to their counterparts. This finding is in agreement with a studies conducted in Malaysia, China, Israel, Southern Alberta, Houston, Nigeria, and Rwanda (10, 14, 35–38). The argument that could be made is that in both developed and developing nations, workload prevents nurses from delivering preoperative patient education.

Insufficient staffing was another factor significantly associated with preoperative patient teaching practice. Study participants who agreed that insufficient staffing was a factor affecting preoperative patient teaching practice were twice likely to demonstrate poor preoperative patient teaching practice compared to the opposite one. This finding is supported by a studies conducted in Canada, Nigeria, and Rwanda (14, 27, 39). The argument that could be made is that both in developed and in developing nations, the shortage of nurses is a problem in delivering preoperative education for patients.

This study found that those nurses who had enough time were significantly associated with good preoperative patient teaching practice as compared with those nurses who did not have enough time. This study was consistent with the studies done in Hong Kong, Saudi Arabia, and northern Ethiopia (10, 20, 40). The possible explanation could be a lack of time due to the high burden of surgical cases following at the current time, as nurses’ engagement in preoperative education and time constraints in clinical practice prevented nurses from performing any patient education activities. This possible explanation is supported by the World Bank report, “The Health Workforce in Ethiopia,” which shows Ethiopia is one of the countries with a very low health workforce, five times below the minimum threshold of 4.45 per 1,000 population set by the World Health Organization to achieve the SDG Health.

Language barriers are another factor significantly associated with preoperative teaching practice and respondents who agreed that the language barrier was a factor were three times more likely to demonstrate poor practice than their counter parts. This finding is supported by studies conducted in China and Nigeria which showed that language barrier was among the highest ranked factors affecting the preoperative teaching practice. A possible justification might be that language is a powerful tool for teaching and learning in all contexts because it facilitates the transference of ideas. The severity of cases was also significant factor associated with quality of teaching practice.

Study participants who agreed it was difficult to teach critically ill patients were six times more likely to demonstrate poor practice than those who disagreed. This finding was also supported by study conducted in Cameroon which revealed that severe medical condition of patients was one of the major factors affecting preoperative teaching practice (25). This may be because teaching patients with serious medical conditions is challenging, and they may even be in comas.

Anxiety among patients and their families was another factor significantly associated with preoperative teaching practice. Respondents who agreed that the patients and their families’ anxiety is a barrier to the practice of preoperative teaching were four times more likely to demonstrate poor practice compared to their counterparts. This result is supported by a study conducted in Rwanda which revealed that 54.1% of respondents agreed that patient and family anxiety about the outcomes of surgery is a barrier to the practice of preoperative patient teaching (14). A possible explanation could be that they are afraid of the outcomes of surgery and are unable to follow or understand what the nurses are teaching them.

The complexity of patients’ status is significantly associated with preoperative teaching practice. The result of this study showed that study participants who agreed that complexity of patients’ status affected preoperative patient teaching practice were four times more likely to demonstrate than their counterparts. This finding is supported by a study conducted in Houston which revealed that the complexity of patients’ status was major factors influencing patient education (39). A possible reason for this finding might be that patients with more than one medical condition find it difficult to concentrate on what nurses are telling them regarding one surgical procedure because they are thinking about another of their conditions at the same time.

The study included different levels of hospitals from primary hospital to tertiary hospitals which increase the study’s representativeness. It was unique in study area as it comprehensively examined factors affecting preoperative teaching practice by examining many variables from different dimensions. As a limitation, the study used only a cross-sectional quantitative study design, which may not be sufficient to find all possible factors associated with preoperative patient teaching practice among nurses. In addition, the cause-and-effect relationship cannot be confirmed in this study because the research design was cross-sectional. Another limitation of the study is due to the resource constraint; we could not conduct an observational data collection method.

The good preoperative patient teaching practices demonstrated by nurses working in hospitals in the West Shoa Zone were found to be inadequate. Preoperative education practices was significantly associated with lack of teaching materials, a lack of training, a heavy workload, time constraints, insufficient staffing, a language barrier, the severity of patient cases, anxiety about postoperative outcomes, and the complexity of patients’ status. Establish preoperative patient teaching programs for nurses that exchange experiences. It is better to strengthen training, adequate staffing, and equip wards with standardized guidelines and teaching materials and motivate and create a safe working environment to provide adequate preoperative teaching.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical approval was obtained from Ambo University College of Medicine and Health Science Ethical review board before the recruitment of study participants reference no: AU/PGC/482/2014. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations or the Declaration of Helsinki. Following approval, a written official letter of cooperation was submitted to each hospital administration office before commencement of data collection. After obtaining permission from university, written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Each participating nurse was informed of the purpose of the study and approximately 10- 15 minutes were required to complete a self-administered questionnaire. To ensure confidentiality, no personal identification of participants was recorded.

LA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ST: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft. NA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft. DT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. FR: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors thank the data collectors and the study participants for their collaborations throughout the study period.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AOR, Adjusted odds ratio; BSc, Bachelor of Science; COR, Crude odds ratio; ERAS, Enhanced recovery after surgery; ERB, Ethical review board; HCP, Healthcare provider; MSc, Master of science; SPSS, Statistical package for the social sciences; VIF, Variance inflation factor.

1. Abouda, Asmaa. Preoperative Nursing Management. Available at:https://www.du.edu.eg/upFilesCenter/exStore/nur/1584383507.pdf

2. Jensen, CD, Sato, AF, Jelalian, E, Pulgaron, ER, Delamater, AM, Jensen, CD, et al. Operative anxiety. Encycl Behav Med. (2013) 1:1383–3. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_101191

3. Bayrak, A, Sagiroglu, G, and Copuroglu, E. Effects of preoperative anxiety on intraoperative hemodynamics and postoperative pain. J Coll Physicians Surg Pakistan. (2019) 29:868–73. doi: 10.29271/jcpsp.2019.09.868

4. Niedzielski, JK, Oszukowska, E, and Słowikowska-Hilczer, J. Undescended testis - current trends and guidelines: a review of the literature. Arch Med Sci. (2016) 12:667–77. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.59940

5. Dandena, F, Leulseged, B, Suga, Y, and Teklewold, B. Magnitude and pattern of inpatient surgical mortality in a tertiary Hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. (2020) 30:371–7. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v30i3.8

6. Wu, JX, Yan, JX, Zhang, LX, Chen, J, Cheng, Y, Wang, YX, et al. Corrigendum to “the effectiveness of distraction as preoperative anxiety management technique in pediatric patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials”. Int J Nurs Stud. (2022) 133:104285. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104285

7. Erkilic, E, Kesimci, E, Soykut, C, Doger, C, Gumus, T, and Kanbak, O. Factors associated with preoperative anxiety levels of Turkish surgical patients: from a single center in Ankara. Patient Prefer Adherence. (2017) 11:291–6. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S127342

8. Gu, X, Zhang, Y, Wei, W, and Zhu, J. Effects of Preoperative anxiety on postoperative outcomes and sleep quality in patients undergoing laparoscopic gynecological surgery. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:1835. doi: 10.3390/jcm12051835

9. Pokharel, K, Bhattarai, B, Tripathi, M, Khatiwada, S, and Subedi, A. Nepalese patients’ anxiety and concerns before surgery. J Clin Anesth. (2011) 23:372–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2010.12.011

10. Lee, C, Kong, L, and If, K. Preoperative patient teaching: the practice and perceptions among surgical ward nurses. J Clin Nurs. (2012) 22:2551–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04345.x

12. Dal Yilmaz, U, Bolat, HN, and Kubra, H. Nurses’ practice of Preoperative patient education in Cyprus. Int J Med Res Heal Sci. (2019) 8:7–14.

13. Yohanes, YB, and Yazew, KG. Preoperative anxiety in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis (2020). doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-17929/v1,

14. Dative, M. Knowledge, practices and barriers of preoperative patients teaching among nurses working in operating theatres at referral teaching hospitals in Rwanda, (2019).

15. Kelmer, GC, Turcotte, JJ, Dolle, SS, Angeles, JD, MacDonald, JH, and King, PJ. Preoperative education for Total joint arthroplasty: does reimbursement reduction threaten improved outcomes? J Arthroplasty. (2021) 36:2651–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.03.016

16. Şahin, A. An assessment of the preoperative information given to patients in the province of Karaman 1. (2015):8–10.

17. Sayin, Y, and Aksoy, G. The Nurse’s role in providing information to surgical patients and family members in Turkey: a descriptive study. AORN J. (2012) 95:772–87. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2011.06.012

18. Poland, F, Spalding, N, Gregory, S, McCulloch, J, Sargen, K, and Vicary, P. Developing patient education to enhance recovery after colorectal surgery through action research: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e013498. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013498

20. Tadesse, B, Kumar, P, Girma, N, Anteneh, S, Yimam, W, and Girma, M. Preoperative patient education practices and predictors among nurses working in East Amhara comprehensive specialized hospitals, Ethiopia, 2022. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2023) 16:237–47. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S398663

21. Girma, M. Preoperative patient education practices and predictors among nurses working in East Amhara comprehensive specialized hospitals. (2023):237–247.

22. Ali, RB, Lalani, NS, and Malik, A. Pre-operative assessment and education. Surg Sci. (2012) 3:10–4. doi: 10.4236/ss.2012.31002

23. Parks, L, Routt, M, and Villiers, ADE. Enhanced recovery after Surgery. J Adv Pract Oncol. (2018) 9:511–9.

24. Bazezew, AM, Nuru, N, Demssie, TG, and Ayele, DG. Knowledge, practice, and associated factors of preoperative patient teaching among surgical unit nurses, at Northwest Amhara comprehensive specialized referral hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia, 2022. BMC Nurs. (2023) 22:20. doi: 10.1186/s12912-023-01175-2

25. Facilities, H. A cross-sectional study of nurses’ practice of patient education in four healthcare Facilities in Buea, Cameroon. Asian J Res Nurs Health. (2020) 3:64–70.

26. Omondi, A, and Preoperative, L. Patient assessment practices: a survey of Kenyan perioperative nurses. Am J Nurs Sci. (2016) 5:185. doi: 10.11648/j.ajns.20160505.13

27. Oyetunde, MO, and Akinmeye, AJ. Factors influencing practice of patient education among nurses at the university college hospital. Ibadan Open J Nurs. (2015) 5:500–7. doi: 10.4236/ojn.2015.55053

28. Garshasbi, S, Khazaeipour, Z, Fakhraei, N, and Naghdi, M. Evaluating knowledge, attitude and practice of health-care workers regarding patient education in Iran. Acta Med Iran. (2016) 54:58–66.

29. Liddle, C. An overview of the principles of preoperative care. Nurs Stand. (2018) 33:74–81. doi: 10.7748/ns.2018.e11170

31. Dalayon, P. Components of preoperative patient teaching in Kuwait. J Adv Nurs. (1994) 19:537–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01118.x

33. Aliyu, D. Knowledge, attitude and practice of Preoperative visit: a survey of Nigerian perioperative nurses. Am J Heal Res. (2015) 3:54. doi: 10.11648/j.ajhr.s.2015030101.18

34. Asefa, G, Estifanos, W, and Chufamo, N. Quality of perioperative Informations provided and it ’ s associated factors among adult patients who undergone surgery in public hospitals of Gamo & Gofa Zones: A mixed design study, Southern Ethiopia, 2019. Int J Sci Basic App Res. (2019) 4531:53–66.

35. Ee, K, Ting, L, Sau, M, Ng, S, and Siew, WF. Patient perception about preoperative information to allay anxiety towards major surgery. IeJSME. (2013) 7:29–32. doi: 10.56026/imu.7.1.29

36. Livne, Y, Peterfreund, I, and Sheps, J. Barriers to patient education and their relationship to nurses’ perceptions of patient education climate. Clin Nurs Stud. (2017) 5:65. doi: 10.5430/cns.v5n4p65

37. Alawadi, ZM, Leal, I, Phatak, UR, Flores-Gonzalez, JR, Holihan, JL, Karanjawala, BE, et al. Facilitators and barriers of implementing enhanced recovery in colorectal surgery at a safety net hospital: a provider and patient perspective. Surg (United States). (2016) 159:700–12. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.08.025

38. Musa, ST, and Ali, WG. Adequacy of pre-operative teaching provided for surgical patients in selected hospitals of Kano state: patients’ perspectives. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci (IOSR-JNHS). (2018) 7:1–09.

39. Taraporevala, S, Sahin, M, Yorek, N, Torres, JP, Mendes, EG, Toenders, FGC, et al. Barriers and facilitators of preoperative education within enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs. Phys Educ. (2017) 23:1–10.

Keywords: preoperative teaching, practice, nurses, patient, Ethiopia

Citation: Atomsa L, Temesgen S, Dechasa A, Ayana M, Amena N, Teklehymanot D and Regea F (2024) Preoperative patient teaching practices and associated factors among nurses working at hospitals in West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia, 2022: a cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health. 12:1498406. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1498406

Received: 18 September 2024; Accepted: 30 November 2024;

Published: 18 December 2024.

Edited by:

Olga Ribeiro, Escola Superior de Enfermagem do Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Solomon Berihe Hiluf, Mizan Aman College of Health Science, EthiopiaCopyright © 2024 Atomsa, Temesgen, Dechasa, Ayana, Amena, Teklehymanot and Regea. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lammi Atomsa, bGFtaWF0b21zYTIwMTNAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.