95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Public Health , 28 March 2025

Sec. Substance Use Disorders and Behavioral Addictions

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1495151

This article is part of the Research Topic Improving and Implementing Addiction Care View all articles

Remai Mitchell1*

Remai Mitchell1* Kerry-Ann F. O’Grady1

Kerry-Ann F. O’Grady1 David Brain1†

David Brain1† Megumi Lim1†

Megumi Lim1† Natalia Gonzalez Bohorquez1†

Natalia Gonzalez Bohorquez1† Ureni Halahakone1†

Ureni Halahakone1† Simone Braithwaite2

Simone Braithwaite2 Joanne Isbel3

Joanne Isbel3 Shelley Peardon-Freeman3

Shelley Peardon-Freeman3 Madonna Kennedy2

Madonna Kennedy2 Zephanie Tyack1

Zephanie Tyack1Introduction: Tobacco smoking is a leading contributor to preventable morbidity and premature mortality globally. Although evidence-based smoking cessation programs have been implemented, there is limited evidence on the application of theories, models, and frameworks (TMFs), and implementation strategies to support such programs. This scoping review mapped the evidence for interventions, TMFs, and implementation strategies used for smoking cessation programs in the community.

Methods: We searched four electronic databases in addition to grey literature and conducted hand-searching between February and December 2023. Original studies of qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods were considered for inclusion. Studies reporting prospectively planned and/or delivered implementation of smoking cessation interventions or programs, incorporating contextual factors, use of implementation TMF, implementation strategies, or other factors influencing implementation were considered for inclusion. Intervention components were categorized using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist. Implementation strategies were mapped to the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) Strategy Clusters.

Results: A total of 31 studies were included. We identified 12 discrete interventions, commonly included as part of multicomponent interventions. Most studies reported tailoring or modifying interventions at the population or individual level. We identified 19 distinct implementation TMFs used to prospectively guide or evaluate implementation in 26 out of 31 included studies. Studies reported diverse implementation strategies. Three studies embedded culturally appropriate TMFs or local cultural guidance into the implementation process. These studies took a collaborative approach with the communities through partnership, participation, cultural tailoring, and community-directed implementation.

Discussion: Our findings highlight the methods by which the implementation of smoking cessation may be supported within the community. Whilst there is debate surrounding their necessity, there are practical benefits to applying TMFs for implementing, evaluating, and disseminating findings. We determined that whilst ERIC was well-suited as a framework for guiding the implementation of future smoking cessation programs, there was inconsistent use of implementation strategies across the ERIC domains. Our findings highlight a lack of harmonization in the literature to culturally tailor implementation processes for local communities.

Tobacco smoking contributes substantial global health burden through disability-adjusted life years (1), poor health-related quality of life (2), and preventable morbidity and premature mortality (3). In some settings, smoking causes more disease and death than alcohol and illicit drugs combined (4). Whilst overall smoking prevalence has declined in most Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development nations in the past decade (5), morbidity and mortality related to tobacco smoking continues to rise with global population growth (6). Whilst smoking cessation programs such as Quitline have been established as an effective, and cost-effective means of reducing tobacco smoking internationally (7–16), evidence-based interventions and practices may not achieve their full or desired effect if poorly implemented (17, 18).

Implementation science bridges the gap between knowledge and practice by evaluating how interventions that have been shown to be effective at small scale, within the controlled research environment, can be embedded on a large-scale into routine service structure and delivery (19–22). Implementation strategies describe the methods used to implement evidence-based practices into routine service provision, and are essential to ensuring successful implementation (23). However, implementation strategies are infrequently used and reported, or may lack an implementation theory, model, and/or framework (TMF) to support their use (23). Whilst there are a number of implementation TMFs reported in the literature (for example (24–28)), they are rarely applied to prospectively guide the study design, development and conduct, or to support interpretation of results from research projects or implementation studies (29). Limited use of implementation TMFs may be due to lack of provider familiarity or experience, or uncertainty about how to apply TMFs to an implementation effort (30). Reporting implementation strategies alongside TMFs supports the evaluation of how interventions, treatments, and services can be implemented successfully into routine care, at scale (31, 32). Furthermore, prospective use of TMFs can guide the design of implementation strategies (33). Reasons for inconsistent use and reporting of implementation strategies are not well understood, however may be due to confusing definitions, inconsistent application of terminology, and poorly described strategies (23). Proctor (23) argues that the degree of implementation success cannot be evaluated, nor can the implementation effort be replicated, without clear, accurate, and complete reporting of the implementation strategies used.

The implementation of smoking cessation programs has been evaluated previously in a number of systematic and scoping reviews (34–40). Existing reviews have focused on specific contexts, for example, within oncology clinics (34), or in hospitals (35, 36). Other reviews have focused on service provider outcomes (36, 39, 40), implementation outcomes (35, 37, 38), or barriers and facilitators of implementation (36, 40). Based on preliminary searches as part of our study, no reviews of the implementation of smoking cessation programs with a focus on the use of TMFs alongside implementation strategies were identified internationally. Therefore, this review focusses on the use of implementation strategies, guided by TMFs or principles where relevant, in the implementation of smoking cessation programs.

The aim of this scoping review was to map evidence regarding the real-world implementation of smoking cessation programs for adults in community contexts. The study objectives were to evaluate the following:

• What interventions are used in the implementation of smoking cessation programs to facilitate quit success?

• What implementation theories, models, and frameworks are used to guide the implementation of smoking cessation programs?

• What implementation strategies are used for smoking cessation programs?

A scoping review was selected to map the current literature and enable synthesis of key concepts across a broad range of study designs and topics (41). Scoping reviews are particularly relevant when the area of research is nascent, unclear, or complex (42, 43). Nicotine addiction is particularly complex due to the physiological, psychological, and behavioral drivers of addiction contributing to high prevalence of tobacco use in groups experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage (44, 45). The study protocol provides a full description of the methods, and is available as a pre-print (46). Minor deviations from the protocol included: (1) changes to the research questions in the study objectives to provide greater clarity for the reader; (2) updates to the inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure potentially relevant papers were included in this review (Tables 1, 2; Figure 1; 46).

We searched Medline via EBSCOhost, Cochrane CENTRAL, Embase, and Web of Science in addition to grey literature and hand searching for published and unpublished studies. Database searching took place on 21 February 2023, and grey literature searching took place from 21 to 23 August 2023. We performed forward and backward citation searching for all included studies via Citation Chaser (47) on 06 December 2023. Original qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods studies conducted between June 1997 and the final search date were considered for inclusion, consistent with the date of inception of the first Quitline in the world in Victoria, Australia (48). No language restrictions were used. The search strategy was adapted for each database or information source in consultation with a research librarian (Supplementary Table 1). Citations identified and retrieved from the search were loaded into EndNote 20.0.12021 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA) citation management system, and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts of remaining articles were loaded into the online platform, Rayyan (49).

The criteria for included studies were based on the JBI Population Concept Context (PCC) mnemonic for scoping reviews (50). Studies reporting a smoking cessation intervention or program in which implementation was prospectively planned and/or delivered and broadly incorporated one or more of the following: (1) implementation strategies; (2) use of a TMF or other factors that influenced planning and delivery of implementation as defined by the authors; (3) contextual factors influencing implementation. This review focusses on implementation strategies and the TMFs guiding these strategies. Contextual factors are beyond the scope of this review and will be reported in a separate paper. The inclusion criteria for studies are described in Table 1, and exclusion criteria described in Table 2.

Title and abstract screening of all studies retrieved during the search was performed independently by three authors; one author (RM) screened all articles, and the remaining two authors (NGB, ML) divided the number of articles evenly to screen for potential inclusion. Conflicts that arose during the screening process were resolved by an independent third reviewer; one author (NGB) resolved conflicts between RM and ML, while ML resolved conflicts between RM and NGB. Where conflicts were not able to be resolved, an additional reviewer resolved the conflicts (ZT). Full-text screening of all articles that passed title and abstract screening was performed by one author (RM) for eligibility against the inclusion criteria, with a random 20 percent verified by ZT. Conflicts that arose during full-text screening were resolved by KOG and DB. Results of the search and the process of inclusion for studies, including reasons for exclusion of studies that underwent full-text screening was reported in the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (51) (Figure 2).

Data were extracted from papers by two reviewers (RM, UH) using the data extraction template developed by the authors, and relevant to the review questions (Supplementary Table 2). The data extraction template was pilot tested and refined by RM and ZT using five randomly included citations, prior to formal extraction of all included papers. Twenty percent of the data extraction from all included studies was validated by two independent reviewers (NGB and ML). Study identifiers, for example, author, year of publication, country, study setting, participant population, sample size and study design were extracted. Data were categorized according to predetermined categories including intervention of interest, implementation TMFs, and implementation strategies (52). Implementation strategies reported in included papers were mapped according to the discrete strategy clusters within the nine domains described in The Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) (53).The ERIC clusters are a categorization of 73 implementation strategies, organized as a guide to implementers for selecting the most appropriate strategies specific to their context, to support the implementation effort (53). Extraction and charting of the data was an iterative process, verified through discussion by four authors (RM, ZT, KOG, DB) until consensus was reached.

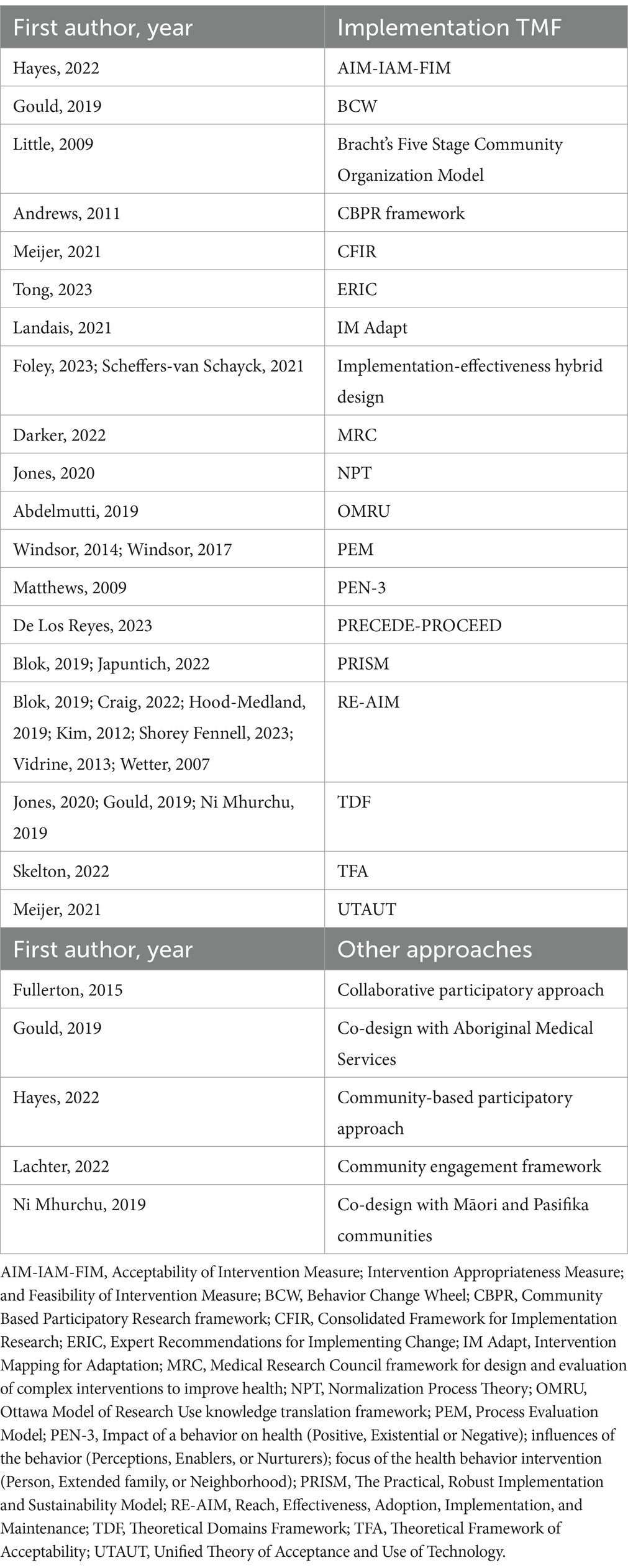

Quantitative and qualitative data from all included studies were extracted and reported using graphical and tabular descriptions of the results, and via narrative synthesis where appropriate. Intervention components were categorized using the template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist (54). Implementation TMFs as stated by the study authors were extracted and collated into a spreadsheet. We further categorized named TMFs within each study, or other identifiable implementation processes where no TMF were reported (Table 3). We checked for evidence on how the chosen TMFs were applied, and their alignment with planning, implementation and evaluation of outcomes. Implementation strategies used in studies were extracted and synthesized according to the nine ERIC strategy domains (53). We also aimed to include implementation strategies that fell outside of the given frameworks and report them separately. Implementation outcomes, and contextual factors and processes evaluated in included studies will be reported separately as they are beyond the scope of this paper.

Table 3. Implementation TMFs, or other approaches used to prospectively guide implementation or evaluation.

The initial database search returned 3,947 unique records after deduplication. Of these, 3,734 (95%) were excluded during title and abstract screening. Full-text publications of the remaining 213 papers were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Of the 213 articles, 21 (10%) were included in the review. An additional 10 papers were identified from grey literature and citation searching, resulting in 31 papers included in this review.

Characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 4. Studies were published between 2007 and 2023, and the majority were conducted in The United States of America (USA; n = 18/31, 58%). Studies used primarily quantitative methods (n = 18/31, 58%), the remaining studies used qualitative (n = 4/31, 13%), or a mixed-methods approach (n = 9/31, 29%).

A tabular description of interventions and characteristics are reported in Table 5. In total, 12 interventions were identified, including individual or group counselling, workbooks and self-help materials, and peer support. Most studies (n = 26/31, 84%) used a theoretical evidence base such as motivational interviewing (55), or clinical guidelines to develop and administer the intervention. Interventions were delivered by diverse providers including nurses, pharmacy staff, and peer supporters. Most studies (n = 27/31, 87%) reported delivering multicomponent interventions. Examples of interventions delivered included no-cost mono-or combination-pharmacotherapy reported in 12 studies (56–67). An additional four studies (68–71) reported provision of pharmacotherapy, but it was unclear whether there was a cost to participants. All studies offering free pharmacotherapy offered more than one intervention, with the majority including counselling (n = 11/12, 92%), alongside other intervention components. Three studies (58, 59, 72) included biofeedback in the form of exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) monitoring as a tool for education, and/or motivation for participants, in addition to verifying abstinence. One study (62) used CO monitoring to verify abstinence, and whilst biofeedback was not an intervention component, participants were offered the use of the CO monitor to track their own cessation progress if desired. Eleven studies used either CO monitoring (57, 63, 64, 66, 73, 74), or salivary or urinary cotinine (56, 60, 65, 69, 75) for the sole purpose of verifying abstinence, and not as an intervention component.

Tailoring and/or modifications were a common component of interventions across included studies (n = 28/31, 90%; Figure 3). We defined tailoring as service provision that takes into consideration the characteristics and needs of the people that the service is being delivered to at individual and population levels (76). Whereas modifications were broadly defined as alterations or additions to the design or delivery of interventions, whether intentional or inadvertent (77). A summary of tailoring and modifications is provided in Table 6. Seventeen studies employed tailoring of interventions at the population level, including developing culturally-tailored interventions for the intended populations (59, 61, 63, 78, 79), gender specific interventions for women (56, 58, 60, 72–74), tailored to the needs and characteristics of the intended populations (65, 66, 75, 80) and for specific patient groups (62, 81). Sixteen studies tailored interventions at the individual-level (57, 58, 60, 65–67, 70, 72–74, 78, 80, 82–85). For example, one study (57) engaged pharmacists to assess, and provide nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) according to each participant’s needs. Another study (84) included several dimensions of tailoring to pregnant participants, including messages via short messaging service (SMS) addressing participants by their first name with information about fetal development and pregnancy relevant to gestation. Messaging content was tailored according to participants’ responses, with the additional capacity to send an SMS to request more or less messages from the program. Participants who did not respond to messages or provide their details, would receive generic, non-tailored SMS. Another common form of tailoring among included studies was in the form of individual counselling tailored to the individual (58, 66, 67, 70, 73, 74, 80, 85). Notwithstanding tailoring, eight studies made modifications to the intervention for the intended population (67, 69, 71, 81, 84–87). Modifications most commonly consisted of counselling and written information made available in different languages (67, 71, 81, 85). Two studies made individual-level modifications which included offering flexibility with the timing of telephone calls with participants (71), or adding smokers in the participant’s household to the referral intervention where previously only individual smoking participants were included (86).

A summary of implementation TMFs, or other approaches to guide implementation is provided in Table 3. We identified substantial heterogeneity in TMFs across studies. Of the included studies, 26 out of 31 used 19 distinct implementation TMFs to prospectively guide and evaluate implementation. Whilst there was heterogeneity in the use of TMFs across studies overall, this was less apparent when observed by country. The Reach Effectiveness Adoption Implementation Maintenance (RE-AIM) Framework (25) was the most commonly applied TMF, used in seven studies (67, 68, 71, 75, 79, 86, 87), all based in the USA. Studies that took place in the USA (n = 18) applied 10 distinct TMFs and/ or community/ co-design approach. Only one study applied more than one TMF or approach (87). In contrast, studies taking place outside of the USA (n = 13/31, 42%) applied 15 distinct TMFs and/ or community/ co-design approaches. Five of these studies used more than one TMF or approach (59, 60, 72, 78, 83). For example, the Theoretical Domains Framework (88) was applied in three studies taking place in Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom (59, 72, 78); these studies also applied co-design with First Nations health services and communities or other TMF.

Examples of the application of TMFs included one study (59) which used both the Theoretical Domains Framework (88) and the Behavior Change Wheel (28) to inform the collaborative design of an intervention with a First Nations community. The frameworks supported the development of an intervention for health providers to the community, which was subsequently implemented. Another study (69) used an effectiveness-implementation hybrid design to support implementation over a number of stages, starting prior to commencement of the research by evaluating the suitability of potential sites to implement the intervention. Included studies that did not use a formal TMF (n = 5/31, 16%) included real-world, implementation projects or used community engagement in the implementation effort (58, 61, 62, 70, 84).

Nineteen studies (56, 57, 59, 63–67, 71–75, 81–83, 85, 86, 89) provided evidence of how the chosen TMF aligned with planning, implementation, or evaluation (90). Examples of this included one study (66) which used intervention mapping (91) through a multi-phased adaptation process. This process included an exploration, preparation, and implementation phase. A detailed description of the processes within each phase of the implementation aligned with the processes described in intervention mapping (91). Another study (85) provided descriptions of the implementation strategies used in the implementation process and how they aligned to the discrete ERIC strategy domains (53), in addition to post-implementation activities.

Diverse approaches to implementation were reported across studies. Of the included studies, one paper (85) used the refined ERIC strategy domains (53) to guide implementation. The remaining studies did not use ERIC (53) but we evaluated what was reported against the definitions provided in the ERIC Discrete Implementation Strategy Compilation (92). Findings are summarized in Table 7. Of the nine domains, “use evaluative and iterative strategies” (n = 24/31, 77%), “adapt and tailor to context” (n = 19/31, 61%), and “train and educate stakeholders” (n = 22/31, 71%) were the most commonly applied strategy domains identified. We did not identify any implementation strategies that could not be mapped to the ERIC compilation (53).

An example of strategies that fell within the ERIC domain “use evaluative and iterative strategies” was identified in one study (74) that developed a “Process Evaluation Model,” to measure adoption and implementation through a “Program Implementation Index (PII).” Individuals involved in various aspects of the implementation effort provided or received training in implementing the program intervention. Performance data were collected throughout study implementation and reviewed quarterly against the PII performance metric. A PII score of 80% or above was considered the standard for adoption. Providers with a PII over 90% were involved in reviewing the Process Evaluation Model results and provided advice on program policies for subsequent phases. After implementation of the new policies, the PII of providers was reviewed again. Whilst providers achieving a PII of 80% or above were sent congratulatory letters, those with a PII of 79% or less would be entered into a quality improvement plan with their supervisor and required re-training.

An example of strategies that fell within the ERIC domain “Adapt and tailor to context” was demonstrated in one study (81) which used a phased approach to implementation. In early phases, professionals were engaged to develop and integrate the intervention into existing digital infrastructure. Piloting was performed to identify how to adapt the intervention to the existing infrastructure, and audits took place to identify issues and needs at each site, to integrate the intervention into the clinical systems.

Another study (58) engaged strategies that fell within the ERIC domain “train and educate stakeholders.” This study engaged a “train the trainer” program, modifying an existing training program to align with the study’s aims. Training was performed by coordinators who developed and distributed materials to community facilitators who were instructed on how to deliver smoking cessation counselling to the intended population. Following the initial two and a half days of training, community facilitators received ongoing mentoring and support through scheduled phone calls or SMS. Community facilitators met in-person to evaluate and plan ongoing program delivery, and provide feedback to the coordinators about the training, and training procedures and materials for future programs.

Tailoring and modifications of interventions at the individual and population levels was employed in 28 out of 31 studies (Figure 3). In the process of evaluating tailoring, we identified three studies (59, 61, 78) in which tailoring was distinct. One study (78) used an implementation TMF (27) alongside behavior change theory (93) and a community participatory research approach. The researchers in this study formed an academic-community partnership established on participation and protection of the First Nations people, drawn from the principles of the founding Treaty of the country in which the study took place (94). The Treaty principles formed the basis of culturally informed community engagement, exploration, planning, feedback, design, iterative development, and piloting throughout the implementation. This study information was not included in the paper, but was detailed on the study website (95). Another study (59) was implemented in a similar fashion, using TMFs (27, 96) to guide culturally sensitive implementation according to First Nations ethics guidelines (97). The researchers partnered with a Stakeholder and Consumer Advisory Panel that included community members and service providers, to collaboratively guide First Nations-specific implementation for the communities involved in the project. Collaboration, cultural sensitivity, and First Nations ownership were emphasized through every stage of the project implementation. This information was outlined in the study protocol and related documents (98–100). A third study (61) did not use an implementation TMF, but used a community engagement framework (101) to guide the participatory approach. Partnership, and shared power and responsibility were emphasized through equitable inclusion of the goals and perspectives of the community, shared purpose, and mutual benefit. The community was engaged throughout project development, training of providers, implementation and monitoring. Community partners provided cultural guidance and designed and lead the community collaboration process. Roles and responsibilities were designated to each of the project partners according to their expertise.

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to evaluate the implementation of smoking cessation interventions alongside implementation theories, models, and frameworks, concurrently mapping implementation strategies to ERIC (53). We identified relevant studies across a range of designs and methods, participant groups, clinical and community settings, and geographic locations. Studies included a broad range of intervention types, delivery modes, providers, and theoretical evidence bases to inform intervention development. Evidence bases most commonly included motivational interviewing (55), and clinical guidelines or standards. There was substantial heterogeneity in TMFs reported across studies. Implementation strategies identified covered all nine ERIC domains, most of which were individual-level strategies (53). Our finding that no strategies fell outside of ERIC is somewhat surprising considering ERIC was compiled and refined in clinical, and mental health, rather than the community-based contexts that were the focus of this review (102).

This review summarized interventions used during the implementation of smoking cessation programs. Our results highlight the numerous intervention types, methods of delivery, providers, and theoretical foundations for implementing smoking cessation interventions in the community. We identified multicomponent interventions tailored to the intended populations, and/or individuals reported in most studies (n = 27/31). Multicomponent, tailored interventions have been shown to be more effective than single, less complex interventions for smoking cessation, particularly for vulnerable, at-risk, and culturally diverse groups (103–105). Furthermore, we identified peer counsellors and community supporters among intervention providers, in addition to peer support as an intervention component. Our findings corroborate with previous research emphasizing the importance of social support alongside intensive, multicomponent interventions (103), However, we did not evaluate the duration of interventions in included studies, which has been identified as an important element of cessation support (103).

We evaluated implementation theories, models and frameworks, limiting the inclusion criteria to studies using an implementation TMF, or other identifiable implementation components (23). Thus, most (n = 26/31) of the included studies used at least one TMF. In two studies that did not use a TMF (59, 61), and one study that did use a TMF (78), community participation and engagement was a strong component of implementation (58). Whilst there are numerous community participatory frameworks for implementation (106–110), a number of studies using community participation to guide the implementation without specifying TMF use have been reported previously in a review (111). There is current debate in the literature suggesting that “common sense” in the form of local knowledge, which could be garnered through community participation, could replace TMFs to guide implementation (32). Whereas others contend that conscientious use of TMFs can support the ability to plan, guide, conduct, and evaluate implementation (29). Furthermore, that TMFs can improve the generalizability and translation of findings through shared terminology and knowledge (29). This suggests that whilst community participation may be considered an effective standalone approach to implementation, judicious application of TMFs may support successful implementation, and translation of theory to practice. Translation to practice is particularly important in countries such as Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, where the First Nations people have considerably higher smoking prevalence due to the ongoing effects of colonization (112). As such, TMF selection should take into consideration the strengths and diversity, in addition to the needs and preferences of these populations for future implementation (113). Furthermore, Australia covers an expansive geographic area, with diverse communities spanning from urban, to very remote and varying access to health services (114). Such contextual factors should be considered when selecting a TMF, to ensure that implementation extends to populations that historically may have been excluded from implementation projects (115, 116).

We excluded studies that did not use a TMF, or other identifiable elements of implementation. Consequently, 129 studies reporting on implementation of smoking cessation programs, including “real-world” studies, were excluded from this review (Figure 2). Reasons for underutilization of TMFs may be due to a number of factors, including difficulty selecting from the overwhelming number of TMFs available, hesitancy in applying a TMF due to lack of knowledge or experience, or confusion due to inaccurate and inconsistent definitions related to implementation terminology (30, 117, 118). Whilst a TMF is not prerequisite for implementation, as demonstrated in a number of included studies (58, 61, 62, 70, 84), there are a number of possible implications to not applying TMFs to an implementation effort. For example, potential benefits for planning, delivery, evaluation, and reporting the implementation of smoking cessation programs may not be realised where a TMF is not applied (29, 119). When conducting full-text screening, we encountered a challenge in differentiating between implementation strategies and intervention components in some studies lacking a TMF, due to unclear terminology and definitions (23), and a lack of clear and methodical structure for implementation processes (120). Whilst smoking cessation interventions have been extensively researched (121), implementing effective interventions into routine practice is vital to combat the rising trajectory of morbidity and mortality related to tobacco smoking (6). Following the advice of others, we suggest taking a purposeful approach, applying the appropriate knowledge and tools that align with the studies purpose and goals to guide and support implementation (117, 119). The process of selecting appropriate TMFs for the target population, study purpose, or context, could be supported by use of checklists and tools (122). Deliberate and appropriate use of TMFs may support the transferability of implementation to other interventions and contexts (29).

We mapped implementation strategies in included studies across the strategy clusters detailed in ERIC, and did not identify any implementation strategies that could not be mapped to ERIC (53). Whilst strategies that fall outside of ERIC have been identified in other studies (123, 124), our findings suggest that ERIC (53) could be an appropriate framework for implementing smoking cessation interventions. We identified diverse approaches to implementation within the ERIC strategy domains in included studies. Individual-level strategies, within the domains of ‘use evaluative and iterative strategies’, ‘adapt and tailor to context’, ‘development of stakeholder interrelationships’, ‘train and educate stakeholders’, and ‘engage consumers’ were commonly applied across included studies. Whereas we noted less common application of service-level strategies within the domains of ‘provide interactive assistance’, ‘utilize financial strategies’, and ‘change infrastructure’. This finding may be due to use of TMFs other than ERIC to guide implementation in all but one study (85), or approaches to implementation without use of a TMF. Alternatively, these systems-level strategies may have been considered incompatible with the aims or scope of the included studies, nevertheless these strategies are vital to translating evidence to practice (125). We suggest that future studies implementing smoking cessation interventions should consider incorporating strategies across ERIC domains to support tailoring of implementation efforts, and translation to practice (126).

A novel finding in this review was the cultural tailoring applied to the process of implementation in three studies (59, 61, 78). Cultural tailoring includes modifications to study procedures and interventions in response to the cultural needs of the population (127), and has been established as an important component of smoking cessation and health services (104, 128, 129). Cultural tailoring is not limited to race and ethnicity, and refers to the shared characteristics that shape the attitudes and behaviors of a population through their interactions with their environment (130). In the three studies (59, 61, 78) that developed culturally tailored interventions, we identified further evidence that the implementation was culturally tailored through purposefully embedding Treaty principles (94), First Nations Ethics and Guidelines (97), and culturally guided application of a community engagement framework (101) to the implementation process. The collaboration between the researchers and communities, development of partnerships, shared decision making, and culturally guided, community-driven intervention and implementation planning, development, delivery, and evaluation aligns with a culture-centered approach (131). Community participation and ownership of the projects was emphasized throughout the implementation of the aforementioned studies (59, 61, 78). These approaches have been previously described using a co-creation lens, which encompasses principles of equity, reflexivity, reciprocity and mutuality, transformation and personalization, and relationship facilitation (132). Emphasis on health equity through genuine community engagement and partnership, shared goals and power, centered on the needs and culture of the community has been identified as critical to progressing the field of implementation science (133). Whilst the culture-centered approach and co-creation have been previously described (131, 134), employing and identifying such strategies in research may be hampered due to confusing terminology, a lack of guidance for design and implementation, and a need for more research on applying frameworks to planning and implementation (134–136). Given the effectiveness of culturally tailoring smoking cessation interventions (104, 137–139), we believe that tailoring the implementation process according to culturally specific guidelines and principles (94, 97) (hereafter referred to as cultural TMFs) has the potential to improve the implementation of smoking cessation programs for intended populations. This could be achieved firstly through advancing terminology and knowledge surrounding the culture-centered approach and the co-creation lens (131, 132). Secondly, by harmonizing approaches described in the aforementioned models, and finally, through improved understanding of how to select and apply appropriate cultural TMFs to implementation projects.

To the best of our knowledge, there are currently no comprehensive reviews mapping smoking cessation interventions, implementation theories, models and frameworks, and implementation strategies. This review contributes substantial knowledge to further the future implementation of smoking cessation interventions in community settings. Nevertheless, there are a number of limitations to this review. Five papers were excluded during full-text screening due to being non-English, additionally we did not include abstracts for which there was no full-text available. We limited the study setting to the community, therefore studies taking place exclusively in inpatient hospital settings were excluded thus limiting the generalizability of the results to non-community based contexts and providers. Whilst we provided a comprehensive report of smoking cessation interventions, TMFs, and implementation strategies, we did not evaluate the intensity and duration of interventions, their effectiveness for smoking cessation outcomes, nor implementation success. Furthermore, we did not evaluate the quality of implementation TMFs for smoking cessation interventions within included studies. Future systematic reviews could build on the findings of this review to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of theory-and non-theory-based implementation strategies for smoking cessation interventions. We mapped implementation strategies to ERIC, however, we acknowledge other taxonomies for implementation strategies exist and could be considered for mapping implementation strategies for smoking cessation programs. Finally, this review did not evaluate de-implementation, which is often required alongside implementation efforts and should be considered in future reviews.

This scoping review identified interventions, TMFs and other approaches, and implementation strategies for smoking cessation programs. We identified broad use of numerous, multi-component, and tailored interventions, by diverse providers, for smoking cessation programs, emphasizing the strategies by which cessation may be supported. These strategies included non-TMF approaches including co-design and community engagement. Culturally tailored implementation emerged as a distinct implementation strategy in three studies. Harmonizing strategies using a culture-centered approach and co-creation lens alongside relevant cultural TMFs could be considered as a means to improve implementation for intended populations, and thus public health.

RM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KOG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. DB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ML: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. NG: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. UH: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SB: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. JI: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. SP-F: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. MK: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. ZT: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by a PhD Supervisor Scholarship provided by the Preventive Health Branch, Queensland Health, to the Queensland University of Technology.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Cameron Rutter for assisting with the search strategy; Manasha Fernando for constructive feedback on the data extraction, analysis and data presentation; and Mark West for his ongoing support of this project. We thank the two reviewers whose feedback helped improve the quality of this manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1495151/full#supplementary-material

AusHSI, Australian Centre for Health Services Innovation; CO, Carbon monoxide; ERIC, The Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change; NRT, Nicotine replacement therapy; PCC, Population Concept Context; PII, Program Implementation Index; PRISMA-ScR, PRISMA extension for scoping reviews; QUT, Queensland University of Technology; RE-AIM, Reach Effectiveness Adoption Implementation Maintenance; SMS, Short messaging service; TIDieR, Template for intervention description and replication; TMF, Theory, model, and/or framework.

1. Reitsma, MB, Fullman, N, Ng, M, Salama, JS, Abajobir, A, Abate, KH, et al. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. (2017) 389:1885–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X

2. Purcell, K, Bellew, B, Greenhalgh, E, and Winstanley, M. 3.22 poorer quality of life and loss of function In: E Greenhalgh, M Scollo, and M Winstanley, editors. Tobacco in Australia: Facts & issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria (2020).

3. Bellew, B, Greenhalgh, E, and Winstanley, M. 3.36 The global tobacco pandemic In: E Greenhalgh, M Scollo, and M Winstanley, editors. Tobacco in Australia: Facts & issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria (2020).

4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019. Canberra: AIHW (2020).

6. Reitsma, MB, Kendrick, PJ, Ababneh, E, Abbafati, C, Abbasi-Kangevari, M, Abdoli, A, et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. (2021) 397:2337–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01169-7

7. Anderson, CM, and Zhu, SH. Tobacco quitlines: looking back and looking ahead. Tob Control. (2007) 16:i81:–i86. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020701

8. Carson-Chahhoud, K KZ, Sharrad, K, and Esterman, A. (2019). Evidence for smoking quitlines: An evidence check rapid review brokered by the sax institute. Cancer Council Victoria.

9. Thao, V, Nyman, JA, Nelson, DB, Joseph, AM, Clothier, B, Hammett, PJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of population-level proactive tobacco cessation outreach among socio-economically disadvantaged smokers: evaluation of a randomized control trial. Addiction. (2019) 114:2206–16. doi: 10.1111/add.14752

10. Tomson, T, Helgason, ÁR, and Gilljam, H. Quitline in smoking cessation: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2004) 20:469–74. doi: 10.1017/S0266462304001370

11. Meeyai, A, Yunibhand, J, Punkrajang, P, and Pitayarangsarit, S. An evaluation of usage patterns, effectiveness and cost of the national smoking cessation quitline in Thailand. Tob Control. (2015) 24:481. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051520

12. Nghiem, N, Cleghorn, CL, Leung, W, Nair, N, Deen, FSV, Blakely, T, et al. A national quitline service and its promotion in the mass media: modelling the health gain, health equity and cost-utility. Tob Control. (2018) 27:434–41. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053660

13. Hollis, JF, McAfee, TA, Fellows, JL, Zbikowski, SM, Stark, M, and Riedlinger, K. The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of telephone counselling and the nicotine patch in a state tobacco quitline. Tob Control. (2007) 16:i53. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.019794

14. Lal, A, Mihalopoulos, C, Wallace, A, and Vos, T. The cost-effectiveness of call-back counselling for smoking cessation. Tob Control. (2014) 23:437–42. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050907

15. Matkin, W, Ordóñez-Mena, JM, and Hartmann-Boyce, J. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2019) 5:2850. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002850.pub4

16. Ferguson, J, Docherty, G, Bauld, L, Lewis, S, Lorgelly, P, Boyd, KA, et al. Effect of offering different levels of support and free nicotine replacement therapy via an English national telephone quitline: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. (2012) 344:e1696. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1696

17. Marchand, E, Stice, E, Rohde, P, and Becker, CB. Moving from efficacy to effectiveness trials in prevention research. Behav Res Ther. (2011) 49:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.008

18. May, CR, Johnson, M, and Finch, T. Implementation, context and complexity. Implement Sci. (2016) 11:141. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0506-3

19. Bauer, MS, Damschroder, L, Hagedorn, H, Smith, J, and Kilbourne, AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. (2015) 3:32. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9

20. Skivington, K, Matthews, L, Simpson, SA, Craig, P, Baird, J, Blazeby, JM, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. (2021) 374:n2061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2061

21. Proctor, E, Silmere, H, Raghavan, R, Hovmand, P, Aarons, G, Bunger, A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Admin Pol Ment Health. (2011) 38:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

22. Kim, E, Boutain, DM, Lim, S, Parker, S, Wang, D, Maldonado Nofziger, R, et al. Organizational contexts, implementation processes, and capacity outcomes of multicultural, multilingual home-based programs in public initiatives: A mixed-methods study. J Adv Nurs. (2022) 78:3409–26. doi: 10.1111/jan.15276

23. Proctor, EK, Powell, BJ, and McMillen, JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:139. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139

24. Proctor, EK, Bunger, AC, Lengnick-Hall, R, Gerke, DR, Martin, JK, Phillips, RJ, et al. Ten years of implementation outcomes research: a scoping review. Implement Sci. (2023) 18:31. doi: 10.1186/s13012-023-01286-z

25. Glasgow, RE, Harden, SM, Gaglio, B, Rabin, B, Smith, ML, Porter, GC, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Public Health. (2019) 7:7. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064

26. Damschroder, LJ, Reardon, CM, Opra Widerquist, MA, and Lowery, J. Conceptualizing outcomes for use with the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR): the CFIR outcomes addendum. Implement Sci. (2022) 17:7. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01181-5

27. Atkins, L, Francis, J, Islam, R, O’Connor, D, Patey, A, Ivers, N, et al. A guide to using the theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. (2017) 12:77. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9

28. Michie, S, van Stralen, MM, and West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. (2011) 6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

29. Moullin, JC, Dickson, KS, Stadnick, NA, Albers, B, Nilsen, P, Broder-Fingert, S, et al. Ten recommendations for using implementation frameworks in research and practice. Implem Sci Commun. (2020) 1:42. doi: 10.1186/s43058-020-00023-7

30. Fernando, M, Abell, B, Tyack, Z, Donovan, T, McPhail, SM, and Naicker, S. Using theories, models, and frameworks to inform implementation cycles of computerized clinical decision support Systems in Tertiary Health Care Settings: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. (2023) 25:e45163:e45163. doi: 10.2196/45163

31. Cassar, S, Salmon, J, Timperio, A, Naylor, P-J, van Nassau, F, Contardo Ayala, AM, et al. Adoption, implementation and sustainability of school-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour interventions in real-world settings: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2019) 16:120. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0876-4

32. Nilsen, P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

33. Porat-Dahlerbruch, J, Fontaine, G, Bourbeau-Allard, È, Spinewine, A, Grimshaw, JM, and Ellen, ME. Desirable attributes of theories, models, and frameworks for implementation strategy design in healthcare: a scoping review protocol. F1000Research. (2022) 11:1003. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.124821.1

34. Young, AL, Stefanovska, E, Paul, C, McCarter, K, McEnallay, M, Tait, J, et al. Implementing smoking cessation interventions for tobacco users within oncology settings: A systematic review. JAMA Oncol. (2023) 9:981–1000. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.0031

35. Ugalde, A, White, V, Rankin, NM, Paul, C, Segan, C, Aranda, S, et al. How can hospitals change practice to better implement smoking cessation interventions? A systematic review. CA Cancer J Clin. (2022) 72:266–86. doi: 10.3322/caac.21709

36. Sharpe, T, Alsahlanee, A, Ward, KD, and Doyle, F. Systematic review of clinician-reported barriers to provision of smoking cessation interventions in hospital inpatient settings. J Smok Cessat. (2018) 13:233–43. doi: 10.1017/jsc.2017.25

37. Nagasawa, T, Saito, J, Odawara, M, Kaji, Y, Yuwaki, K, Imamura, H, et al. Smoking cessation interventions and implementations across multiple settings in Japan: a scoping review and supplemental survey. Implement Sci Commun. (2023) 4:146. doi: 10.1186/s43058-023-00517-0

38. He, L, Balaji, D, Wiers, RW, Antheunis, ML, and Krahmer, E. Effectiveness and acceptability of conversational agents for smoking cessation: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. (2023) 25:1241–50. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntac281

39. Tildy, BE, McNeill, A, Perman-Howe, PR, and Brose, LS. Implementation strategies to increase smoking cessation treatment provision in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies. BMC Primary Care. (2023) 24:32. doi: 10.1186/s12875-023-01981-2

40. Wolfenden, L, and Wolfenden, L. (2021). Barriers and enablers to embedding smoking cessation support in community service organisations: a rapid evidence summary prepared by the sax institute (www.saxinstitute.org.au) for the Tasmanian Department of Health.

41. Zauza, D, Dotto, L, Moher, D, Tricco, AC, Agostini, BA, and Sarkis-Onofre, R. There is room for improvement in the use of scoping reviews in dentistry. J Dent. (2022) 122:104161. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2022.104161

42. Pham, MT, Rajić, A, Greig, JD, Sargeant, JM, Papadopoulos, A, and McEwen, SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. (2014) 5:371–85. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1123

43. Peterson, J, Pearce, PF, Ferguson, LA, and Langford, CA. Understanding scoping reviews: definition, purpose, and process. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. (2017) 29:12–6. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12380

44. Mannino, DM. Why won't our patients stop smoking? The power of nicotine addiction. Diabetes Care. (2009) 32:S426–8. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S353

45. Twyman, L, Bonevski, B, Paul, C, and Bryant, J. Perceived barriers to smoking cessation in selected vulnerable groups: a systematic review of the qualitative and quantitative literature. BMJ Open. (2014) 4:e006414. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006414

46. Mitchell, R, O'Grady, K, Brain, D, and Tyack, Z. Evaluating the implementation of adult smoking cessation programs in community settings: protocol for a scoping review [version 1; peer review: awaiting peer review]. F1000Research. (2023) 12:5736. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.135736.1

47. Haddaway, NR, Grainger, MJ, and Gray, CT. Citationchaser: an R package for forward and backward citations chasing in academic searching. 0.0.3 ed2021. (2021).

48. Miller, CL, Wakefield, M, and Roberts, L. Uptake and effectiveness of the Australian telephone Quitline service in the context of a mass media campaign. Tob Control. (2003) 12:ii53–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii53

49. Ouzzani, M, Hammady, H, Fedorowicz, Z, and Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan — a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2016) 5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

50. Peters, MD, Godfrey, CM, Khalil, H, McInerney, P, Parker, D, and Soares, CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. (2015) 13:141–6. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

51. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2021) 10:89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

52. Peters, S, Sukumar, K, Blanchard, S, Ramasamy, A, Malinowski, J, Ginex, P, et al. Trends in guideline implementation: an updated scoping review. Implement Sci. (2022) 17:50. doi: 10.1186/s13012-022-01223-6

53. Waltz, TJ, Powell, BJ, Matthieu, MM, Damschroder, LJ, Chinman, MJ, Smith, JL, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:109. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0

54. Hoffmann, TC, Glasziou, PP, Boutron, I, Milne, R, Perera, R, Moher, D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. (2014) 348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687

55. Bischof, G, Bischof, A, and Rumpf, HJ. Motivational interviewing: an evidence-based approach for use in medical practice. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2021) 118:109–15. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0014

56. Darker, CD, Burke, E, Castello, S, O'Sullivan, K, O'Connell, N, Vance, J, et al. A process evaluation of 'We can Quit': a community-based smoking cessation intervention targeting women from areas of socio-disadvantage in Ireland. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:1528. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13957-5

57. De Los, RG, Ng, A, Valencia Chavez, J, Apollonio, DE, Kroon, L, Lee, P, et al. Evaluation of a pharmacist-linked smoking cessation intervention for adults experiencing homelessness. Subst Use Misuse. (2023) 58:1519–27. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2023.2231060

58. Fullerton, D, Bauld, L, and We Can Quit, Dobbie F. Findings from the Action Research Study 2015. Available at: https://www.cancer.ie/sites/default/files/2019-11/we_can_quit_report_2015.pdf (Accessed 09 August, 2023).

59. Gould, GS, Bovill, M, Pollock, L, Bonevski, B, Gruppetta, M, Atkins, L, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of indigenous counselling and nicotine (ICAN) QUIT in pregnancy multicomponent implementation intervention and study design for Australian indigenous pregnant women: a pilot cluster randomised step-wedge trial. Addict Behav. (2019) 90:176–90. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.10.036

60. Hayes, CB, Patterson, J, Castello, S, Burke, E, O'Connell, N, Darker, CD, et al. Peer-delivery of a gender-specific smoking cessation intervention for women living in disadvantaged communities in Ireland we can Quit2 (WCQ2)-A pilot cluster randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. (2022) 24:564–73. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntab242

61. Lachter, R, Rhodes, K, Roland, K, Villaluz, CC, Short, E, Vargas-Belcher, R, et al. Turning community feedback into a culturally responsive program for American Indian/Alaska native commercial tobacco users. Prog Commun Health Partnerships Res Educ Act. (2022) 16:321–9. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2022.0049

62. LeLaurin, JH, Dallery, J, Silver, NL, Markham, M-J, Theis, RP, Chetram, D, et al. An implementation trial to improve tobacco treatment for Cancer patients: patient preferences, treatment acceptability and effectiveness. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:2280. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072280

63. Matthews, AK, Sánchez-Johnsen, L, and King, A. Development of a culturally targeted smoking cessation intervention for African American smokers. J Community Health. (2009) 34:480–92. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9181-5

64. Skelton, E, Lum, A, Cooper, LE, Barnett, E, Smith, J, Everson, A, et al. Addressing smoking in sheltered homelessness with intensive smoking treatment (ASSIST project): A pilot feasibility study of varenicline, combination nicotine replacement therapy and motivational interviewing. Addict Behav. (2022) 124:107074. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107074

65. Andrews, JO, Tingen, MS, Jarriel, SC, Caleb, M, Simmons, A, Brunson, J, et al. Application of a CBPR framework to inform a multi-level tobacco cessation intervention in public housing neighborhoods. Am J Community Psychol. (2011) 50:129–40.

66. Landais, LL, van Wijk, E, and Harting, J. Smoking cessation in lower socioeconomic groups: adaptation and pilot test of a rolling group intervention. Biomed Res Int. (2021) 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2021/8830912

67. Shorey Fennell, B, Cottrell-Daniels, C, Hoover, DS, Spears, CA, Nguyen, N, Piñeiro, B, et al. The implementation of ask-advise-connect in a federally qualified health center: a mixed methods evaluation using the re-aim framework. Transl Behav Med. (2023) 13:551–60. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibad007

68. Craig, EJ, Ramsey, AT, Baker, TB, James, AS, Luke, DA, Malone, S, et al. Point of care tobacco treatment sustains during COVID-19, a global pandemic. Cancer Epidemiol. (2022) 78:102005. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2021.102005

69. Foley, KL, Dressler, EV, Weaver, KE, Sutfin, EL, Miller, DP Jr, Bellinger, C, et al. The optimizing lung screening trial (WF-20817CD): multicenter randomized effectiveness implementation trial to increase tobacco use cessation for individuals undergoing lung screening. Chest. (2023) 164:531–43. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2023.03.013

70. Smith, PM, Seamark, LD, and Beck, K. Integration of an evidence-based tobacco cessation program into a substance use disorders program to enhance equity of treatment access for northern, rural, and remote communities. Transl Behav Med. (2020) 10:555–64. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz162

71. Vidrine, JI, Shete, S, Cao, Y, Greisinger, A, Harmonson, P, Sharp, B, et al. Ask-advise-connect: a new approach to smoking treatment delivery in health care settings. JAMA Intern Med. (2013) 173:458–64. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3751

72. Jones, S, Hamilton, S, Bell, R, Araujo-Soares, V, and White, M. Acceptability of a cessation intervention for pregnant smokers: a qualitative study guided by normalization process theory. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1512. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09608-2

73. Windsor, R, Clark, J, Cleary, S, Davis, A, Thorn, S, Abroms, L, et al. Effectiveness of the smoking cessation and reduction in pregnancy treatment (SCRIPT) dissemination project: a science to prenatal care practice partnership. Matern Child Health J. (2014) 18:180–90. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1252-7

74. Windsor, R, Clark, J, Davis, A, Wedeles, J, and Abroms, L. A process evaluation of the WV smoking cessation and reduction in pregnancy treatment (SCRIPT) dissemination initiative: assessing the Fidelity and impact of delivery for state-wide, home-based healthy start services. Matern Child Health J. (2017) 21:96–107. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2098-6

75. Kim, A, Towers, A, Renaud, J, Zhu, J, Shea, JA, Galvin, RS, et al. Application of the RE-AIM framework to evaluate the impact of a worksite-based financial incentive intervention for smoking cessation. J Occup Environ Med. (2012) 54:610–4. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31824b2171

76. Beck, C, McSweeney, JC, Richards, KC, Roberson, PK, Tsai, PF, and Souder, E. Challenges in tailored intervention research. Nurs Outlook. (2010) 58:104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.10.004

77. Stirman, SW, Miller, CJ, Toder, K, and Calloway, A. Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:65. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-65

78. Ni Mhurchu, C, Te Morenga, L, Tupai-Firestone, R, Grey, J, Jiang, Y, Jull, A, et al. A co-designed mHealth programme to support healthy lifestyles in Māori and Pasifika peoples in New Zealand (OL@-OR@): a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Digit Health. (2019) 1:e298–307. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30130-X

79. Wetter, DW, Mazas, C, Daza, P, Nguyen, L, Fouladi, RT, Li, Y, et al. Reaching and treating Spanish-speaking smokers through the National Cancer Institute's Cancer information service. A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. (2007) 109:406–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22360

80. Scheffers-van Schayck, T, Wetter, DW, Otten, R, Engels, R, and Kleinjan, M. Program uptake of a parent-tailored telephone smoking cessation counselling: an examination of recruitment approaches. Tob Prev Cessat. (2021) 7:1–11. doi: 10.18332/tpc/133019

81. Abdelmutti, N, Brual, J, Papadakos, J, Fathima, S, Goldstein, DP, Eng, L, et al. Implementation of a comprehensive smoking cessation program in Cancer care. Curr Oncol. (2019) 26:361–8. doi: 10.3747/co.26.5201

82. Little, SJ, Hollis, JF, Fellows, JL, Snyder, JJ, and Dickerson, JF. Implementing a tobacco assisted referral program in dental practices. J Public Health Dent. (2009) 69:149–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2008.00113.x

83. Meijer, E, Korst, JS, Oosting, KG, Heemskerk, E, Hermsen, S, Willemsen, MC, et al. "at least someone thinks I'm doing well": a real-world evaluation of the quit-smoking app StopCoach for lower socio-economic status smokers. Addict Sci Clin Pract. (2021) 16:48. doi: 10.1186/s13722-021-00255-5

84. Naughton, F, Cooper, S, Bowker, K, Campbell, K, Sutton, S, Leonardi-Bee, J, et al. Adaptation and uptake evaluation of an SMS text message smoking cessation programme (MiQuit) for use in antenatal care. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e008871. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008871

85. Tong, EK, Zhu, S-H, Anderson, CM, Avdalovic, MV, Amin, AN, Diamant, AL, et al. Implementation, maintenance, and outcomes of an electronic referral to a tobacco Quitline across five health systems. Nicotine Tob Res. (2023) 25:1135–44. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntad008

86. Hood-Medland, EA, Stewart, SL, Nguyen, HH, Avdalovic, MV, MacDonald, S, Zhu, S-H, et al. Health system implementation of a tobacco Quitline eReferral. Appl Clin Inform. (2019) 10:735–42. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1697593

87. Blok, AC, Sadasivam, RS, Hogan, TP, Patterson, A, Day, N, and Houston, TK. Nurse-driven mHealth implementation using the technology inpatient program for smokers (TIPS): mixed methods study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2019) 7:14331. doi: 10.2196/14331

88. Cane, J, O’Connor, D, and Michie, S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. (2012) 7:37. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37

89. Japuntich, S, Adkins-Hempel, M, Lundtvedt, C, Becker, S, Helseth, S, Fu, S, et al. Implementing chronic care model treatments for cigarette dependence in community mental health clinics. J Dual Diagn. (2022) 18:153–64. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2022.2090647

90. Damschroder, LJ. Clarity out of chaos: use of theory in implementation research. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 283:112461. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.036

91. Highfield, L, Hartman, MA, Mullen, PD, Rodriguez, SA, Fernandez, ME, and Bartholomew, LK. Intervention mapping to adapt evidence-based interventions for use in practice: increasing mammography among African American women. Biomed Res Int. (2015) 2015:160103:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2015/160103

92. Powell, BJ, Waltz, TJ, Chinman, MJ, Damschroder, LJ, Smith, JL, Matthieu, MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

93. Michie, S, Ashford, S, Sniehotta, FF, Dombrowski, SU, Bishop, A, and French, DP. A refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: the CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol Health. (2011) 26:1479–98. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2010.540664

94. Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora (2023). Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Wellington, NZ: Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. Available at: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/te-tiriti-o-waitangi (Accessed 24 July, 2024).

95. The University of Auckland NZ (2017). OL@-OR@: The University of Auckland, New Zealand. Available at: https://olaora.auckland.ac.nz/ (Accessed 18 July, 2024).

96. Gould, GS, Bar-Zeev, Y, Bovill, M, Atkins, L, Gruppetta, M, Clarke, MJ, et al. Designing an implementation intervention with the Behaviour Change Wheel for health provider smoking cessation care for Australian Indigenous pregnant women. Implement Sci. (2017) 12:1:114.

97. AH&MRC Ethics Committee (2023). NSW Aboriginal Health Ethics Guidelines: Key Principles. Available at: https://www.ahmrc.org.au/resource/nsw-aboriginal-health-ethics-guidelines-key-principles/ (Accessed 30 July, 2024).

98. Bar-Zeev, Y, Bonevski, B, Bovill, M, Gruppetta, M, Oldmeadow, C, Palazzi, K, et al. The Indigenous Counselling and Nicotine (ICAN) QUIT in Pregnancy Pilot Study protocol: a feasibility step-wedge cluster randomised trial to improve health providers' management of smoking during pregnancy. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e016095. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016095

99. Bovill, M, Bar-Zeev, Y, Gruppetta, M, O'Mara, P, Cowling, B, and Gould, GS. Collective and negotiated design for a clinical trial addressing smoking cessation supports for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander mothers in NSW, SA and Qld – developing a pilot study. Aust J Prim Health. (2017) 23:497–503. doi: 10.1071/PY16140

100. Gould, G. SISTAQUIT - improving strategies to support pregnant aboriginal women to quit smoking, NHMRC and global Alliance for chronic disease. Impact. (2017) 2017:6–8. doi: 10.21820/23987073.2017.10.6

101. Ahmed, SM, and Palermo, AG. Community engagement in research: frameworks for education and peer review. Am J Public Health. (2010) 100:1380–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178137

102. Balis, LE, Houghtaling, B, and Harden, SM. Using implementation strategies in community settings: an introduction to the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) compilation and future directions. Transl Behav Med. (2022) 12:965–78. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibac061

103. Huynh, N, Tariq, S, Charron, C, Hayes, T, Bhanushali, O, Kaur, T, et al. Personalised multicomponent interventions for tobacco dependence management in low socioeconomic populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2022) 76:716–29. doi: 10.1136/jech-2021-216783

104. Leinberger-Jabari, A, Golob, MM, Lindson, N, and Hartmann-Boyce, J. Effectiveness of culturally tailoring smoking cessation interventions for reducing or quitting combustible tobacco: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Addiction. (2024) 119:629–48. doi: 10.1111/add.16400

105. Greenhalgh, E, and Scollo, M. 9.6 tailored and targeted interventions for low socioeconomic groups In: E Greenhalgh, M Scollo, and M Winstanley, editors. Tobacco in Australia: Facts & issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria (2022).

106. Collins, SE, Clifasefi, SL, Stanton, J, The Leap Advisory, B, Straits, KJE, Gil-Kashiwabara, E, et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am Psychol. (2018) 73:884–98. doi: 10.1037/amp0000167

107. Woodward, EN, Ball, IA, Willging, C, Singh, RS, Scanlon, C, Cluck, D, et al. Increasing consumer engagement: tools to engage service users in quality improvement or implementation efforts. Front Health Serv. (2023) 3:1124290. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2023.1124290

108. Gunn, CM, Sprague Martinez, LS, Battaglia, TA, Lobb, R, Chassler, D, Hakim, D, et al. Integrating community engagement with implementation science to advance the measurement of translational science. J Clin Transl Sci. (2022) 6:e107. doi: 10.1017/cts.2022.433

109. Cornish, F, Breton, N, Moreno-Tabarez, U, Delgado, J, Rua, M, et al. Participatory action research. Nat Rev Methods Prim (2023);3, doi: 10.1038/s43586-023-00214-1 [Epub ahead of print].

110. Fernandez, ME, Ruiter, RAC, Markham, CM, and Kok, G. Intervention mapping: theory-and evidence-based health promotion program planning: perspective and examples. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:209. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00209

111. Haldane, V, Chuah, FLH, Srivastava, A, Singh, SR, Koh, GCH, Seng, CK, et al. Community participation in health services development, implementation, and evaluation: A systematic review of empowerment, health, community, and process outcomes. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0216112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216112

112. Maddox, R, Waa, A, Lee, K, Nez Henderson, P, Blais, G, Reading, J, et al. Commercial tobacco and indigenous peoples: a stock take on framework convention on tobacco control progress. Tob Control. (2019) 28:574–81. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054508

113. Prehn, J. An Indigenous Strengths-based Theoretical Framework. Australian Social Work. (2024) 1–14.

114. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024). Rural and remote health. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-and-remote-health (Accessed 21 November, 2024).

115. McCalman, JR. The transfer and implementation of an aboriginal Australian wellbeing program: a grounded theory study. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:129. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-129

116. Woodward, EN, Singh, RS, Ndebele-Ngwenya, P, Melgar Castillo, A, Dickson, KS, and Kirchner, JE. A more practical guide to incorporating health equity domains in implementation determinant frameworks. Implem Sci Commun. (2021) 2:61. doi: 10.1186/s43058-021-00146-5

117. Strifler, L, Barnsley, JM, Hillmer, M, and Straus, SE. Identifying and selecting implementation theories, models and frameworks: a qualitative study to inform the development of a decision support tool. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2020) 20:91. doi: 10.1186/s12911-020-01128-8

118. Lynch, EA, Mudge, A, Knowles, S, Kitson, AL, Hunter, SC, and Harvey, G. "there is nothing so practical as a good theory": a pragmatic guide for selecting theoretical approaches for implementation projects. BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18:857. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3671-z

119. Birken, SA, Powell, BJ, Shea, CM, Haines, ER, Alexis Kirk, M, Leeman, J, et al. Criteria for selecting implementation science theories and frameworks: results from an international survey. Implement Sci. (2017) 12:124. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0656-y

120. Gold, R, Bunce, AE, Cohen, DJ, Hollombe, C, Nelson, CA, Proctor, EK, et al. Reporting on the strategies needed to implement proven interventions: an example from a “real-world” cross-setting implementation study. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016) 91:1074–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.03.014

121. United States Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon General; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health (2020). Smoking cessation: A report of the surgeon General Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services. Chapter 6, interventions for smoking cessation and treatments for nicotine dependence. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555596/ (Accessed 20 April, 2024).

122. Birken, SA, Rohweder, CL, Powell, BJ, Shea, CM, Scott, J, Leeman, J, et al. T-CaST: an implementation theory comparison and selection tool. Implement Sci. (2018) 13:143. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0836-4

123. Perry, CK, Damschroder, LJ, Hemler, JR, Woodson, TT, Ono, SS, and Cohen, DJ. Specifying and comparing implementation strategies across seven large implementation interventions: a practical application of theory. Implement Sci. (2019) 14:32. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0876-4

124. Nathan, N, Powell, BJ, Shelton, RC, Laur, CV, Wolfenden, L, Hailemariam, M, et al. Do the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) strategies adequately address sustainment? Front Health Serv. (2022) 2:905909. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.905909

125. Lovero, KL, Kemp, CG, Wagenaar, BH, Giusto, A, Greene, MC, Powell, BJ, et al. Application of the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) compilation of strategies to health intervention implementation in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Implement Sci. (2023) 18:56. doi: 10.1186/s13012-023-01310-2

126. Jones, LK, Sturm, AC, and Gionfriddo, MR. Translating guidelines into practice via implementation science: an update in lipidology. Curr Opin Lipidol. (2022) 33:336–41. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000835

127. Joo, JY, and Liu, MF. Culturally tailored interventions for ethnic minorities: A scoping review. Nurs Open. (2021) 8:2078–90. doi: 10.1002/nop2.733

128. Singh, H, Fulton, J, Mirzazada, S, Saragosa, M, Uleryk, EM, and Nelson, MLA. Community-based culturally tailored education programs for black communities with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and stroke: systematic review findings. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2023) 10:2986–3006. doi: 10.1007/s40615-022-01474-5

129. Lapinski, MK, Oetzel, JG, Park, S, and Williamson, AJ. (2024). Cultural tailoring and targeting of messages: a systematic literature review. Health Commun.1–14. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2024.2369340. [Epub ahead of print].

130. Griffith, DM, Efird, CR, Baskin, ML, Webb Hooper, M, Davis, RE, and Resnicow, K. Cultural sensitivity and cultural tailoring: lessons learned and refinements after two decades of incorporating culture in health communication research. Annu Rev Public Health. (2024) 45:195–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-060722-031158

131. Harding, T, and Oetzel, J. Implementation effectiveness of health interventions for indigenous communities: a systematic review. Implement Sci. (2019) 14:76. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0920-4

132. Pérez Jolles, M, Willging, CE, Stadnick, NA, Crable, EL, Lengnick-Hall, R, Hawkins, J, et al. Understanding implementation research collaborations from a co-creation lens: recommendations for a path forward. Front Health Serv. (2022) 2:2. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.942658

133. Brownson, RC, Kumanyika, SK, Kreuter, MW, and Haire-Joshu, D. Implementation science should give higher priority to health equity. Implement Sci. (2021) 16:28. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01097-0

134. Vargas, C, Whelan, J, Brimblecombe, J, and Allender, S. Co-creation, co-design, co-production for public health – a perspective on definitions and distinctions. Public Health Res Pract. (2022) 32:e2022. doi: 10.17061/phrp3222211

135. Longworth, GR, Goh, K, Agnello, DM, Messiha, K, Beeckman, M, Zapata-Restrepo, JR, et al. A review of implementation and evaluation frameworks for public health interventions to inform co-creation: a health CASCADE study. Health Res Policy Syst. (2024) 22:39. doi: 10.1186/s12961-024-01126-6

136. Oetzel, J, Scott, N, Hudson, M, Masters-Awatere, B, Rarere, M, Foote, J, et al. Implementation framework for chronic disease intervention effectiveness in Māori and other indigenous communities. Glob Health. (2017) 13:69. doi: 10.1186/s12992-017-0295-8

137. Mattock, R, Owen, L, and Taylor, M. The cost-effectiveness of tailored smoking cessation interventions for people with severe mental illness: a model-based economic evaluation. eClinicalMedicine. (2023) 57:101828. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101828

138. McEntee, A, Hines, S, Trigg, J, Fairweather, K, Guillaumier, A, Fischer, J, et al. (2022). Tobacco cessation and screening in culturally and linguistically diverse communities: an Evidence Check rapid review brokered by the Sax Institute (www.saxinstitute.org.au) for Cancer Council NSW. Available at: https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/evidence-check/tobacco-cessation-and-screening-in-cald-communities/.

139. Greenhalgh, E, and Scollo, M. 9A.2 culturally and linguistically diverse groups In: E Greenhalgh, M Scollo, and M Winstanley, editors. Tobacco in Australia: Facts & issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria (2022).

140. Blanchard, C, Livet, M, Ward, C, Sorge, L, Sorensen, TD, and McClurg, MR. The active implementation frameworks: A roadmap for advancing implementation of comprehensive medication Management in Primary care. Res Soc Adm Pharm. (2017) 13:922–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.05.006

Keywords: smoking cessation interventions, implementation science, theories, models, and frameworks, implementation strategies, scoping review, co-design

Citation: Mitchell R, O’Grady KF, Brain D, Lim M, Bohorquez NG, Halahakone U, Braithwaite S, Isbel J, Peardon-Freeman S, Kennedy M and Tyack Z (2025) Evaluating the implementation of adult smoking cessation programs in community settings: a scoping review. Front. Public Health. 12:1495151. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1495151

Received: 12 September 2024; Accepted: 09 December 2024;

Published: 28 March 2025.

Edited by:

Eline Meijer, Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC), NetherlandsReviewed by: