- 1State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases and National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases and Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 2State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases and National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases and Eastern Clinic, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

Cleft palate presents multifaceted challenges impacting speech, hearing, appearance, and cognition, significantly affecting patients’ quality of life (QoL). While surgical advancements aim to restore function and improve appearance, traditional clinical measures often fail to comprehensively capture patients’ experiences. Patient-reported outcomes measure (PROMs) have emerged as crucial tools in evaluating QoL, offering insights into various aspects such as esthetic results, speech function, and social integration. This review explores PROMs relevant to cleft palate complications, including velopharyngeal insufficiency, oronasal fistulas, maxillary hypoplasia, sleep-disordered breathing, and caregiver QoL. Additionally, the review highlights the need for cleft palate-specific scales to better address the unique challenges faced by patients. By incorporating PROMs, healthcare providers can achieve more personalized, patient-centered care, improve communication, and enhance treatment outcomes. Future research should focus on developing and validating specialized PROMs to further refine patient assessments and care strategies.

1 Introduction

Cleft palate may affect the soft/hard palate and alveolar region (1), significantly impacting speech, hearing, appearance, and cognition (2). Surgical techniques have been developed to restore velopharyngeal function and normal appearance, aiming to improve quality of life (QoL). However, traditional objective measures of surgical outcomes often lack the comprehensiveness needed to convey patients’ experiences to clinicians. Patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) are employed to gather information on patients’ QoL. PROMs offer a wide range of insights, including esthetic results, speech function, self-image, social integration, etc., obtained directly from simply one patient-completed questionnaire (3).

Cleft palate may significantly impact patients throughout their lives. Early challenges, such as feeding difficulties, can affect the patient’s growth (4). Meanwhile, cleft palate increases the risk of ear infections and hearing loss since eustachian tubes are poorly developed and food can easily enter the ear (5, 6). What’s more, speech dysfunctions and altered appearance can lead to social struggle due to difficulty in communication and odd pronunciation (7). Incorrect surgical treatments (e.g., bad timing or wrong technique) may result in complications such as oronasal fistulas, which allows food and liquids to enter the nasal cavity, inducing inflammation and halitosis (7). Sleep problems are also common after cleft palate repair, especially following secondary velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI) correction, and sleep deprivation can hinder growth, cause learning difficulties, and delay socialization (8). The bond between children with cleft palate and their caregivers is crucial for their self-esteem and development (9). Overall, cleft palate presents complex challenges to the patient’s entire life growth that are difficult to fully resolve through treatment and affects the patient’s QoL.

Therefore, it is paramount to utilizing appropriate instruments to comprehensively understand the nuanced aspects of the patient’s QoL. General questionnaires, like the Child Oral Health Impact Profile (COHIP) and the Child Oral Health Quality of Life Questionnaire (COHQOL), have been developed to measure the overall quality of life in children with cleft palate. However, the lack of scales targeting specific issues related to cleft palate makes it challenging for clinicians and researchers to obtain detailed information. There are generic questionnaires to measure the QoL in specific symptoms related to cleft palate and cleft palate-related complications (10). Although they may not be highly relevant to cleft palate, they can still collect more detailed data in specific areas. Herein, this mini review aims to give a brief introduction to these various assessment tools for cleft-palate-complications-related PROMs, which may help in developing cleft-palate-specific scales in the future.

2 Complications after cleft palate repair and patient-reported outcomes measure

2.1 Velopharyngeal insufficiency

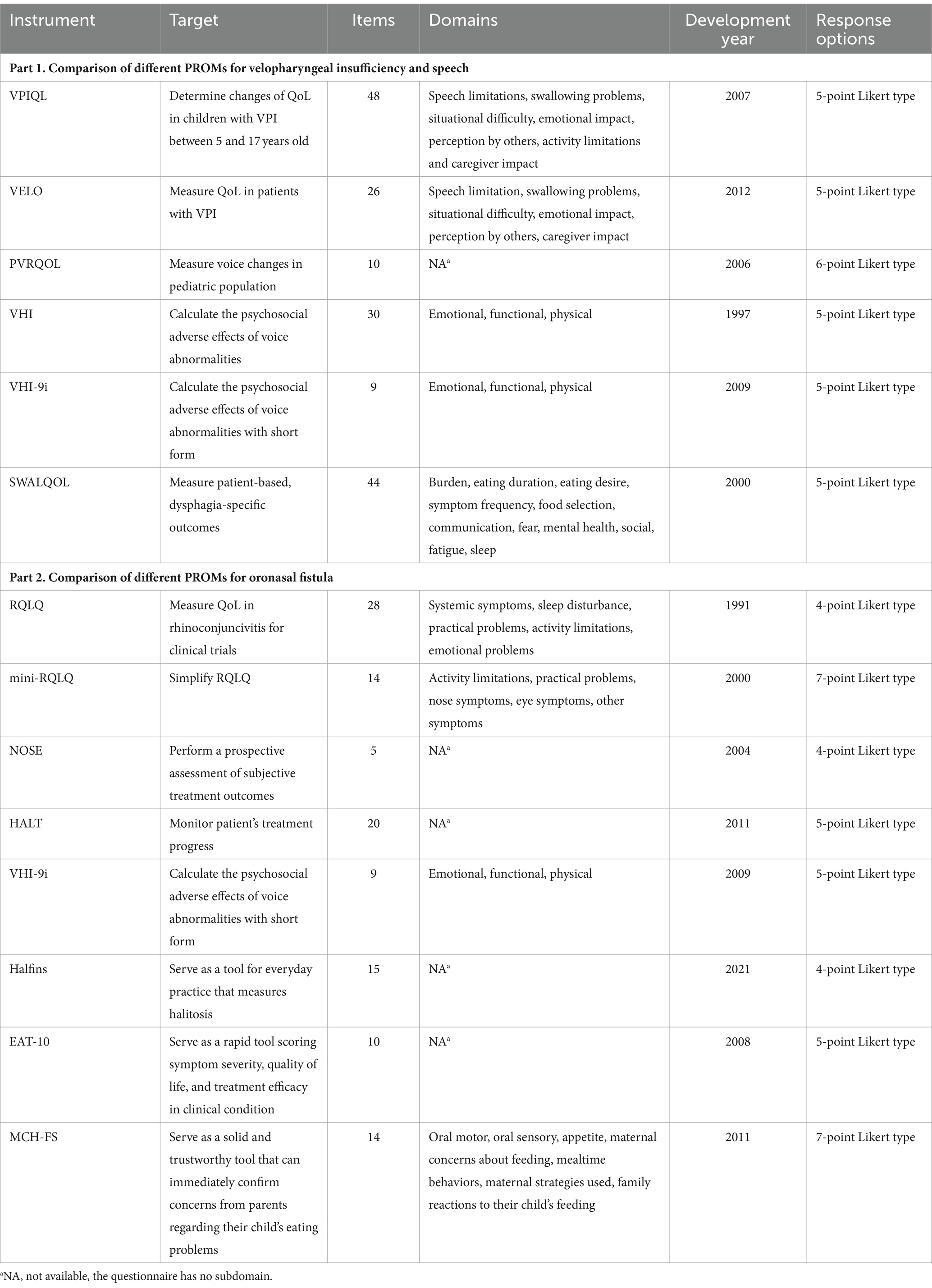

VPI can cause hypernasality and nasal air emission, leading to incomprehensible speech and affecting psychological well-being (11, 12). For PROMs related to VPI, we can use either questionnaires specifically designed for VPI or those focused on general speech-related issues (Table 1, Part 1).

Table 1. Comparison of different PROMs for velopharyngeal insufficiency and speech, and oronasal fistula.

The Velopharyngeal Insufficiency Quality of Life instrument (VPIQL) measures VPI impact in US patients (13), yet its length can be cumbersome for clinical use. Its revised version, VPI Effects on Life Outcomes (VELO), reduces patient and caregiver burden and is used in multiple countries, including China (14, 15), Nepal (16), Spain (17, 18), the Netherlands (19), Brazil (20), etc. It serves as a simple tool to help clinicians understand the social, emotional, and physical influences of VPI (14).

The Voice-Related Quality of Life Measure (VRQOL) is for adults, but does not fit for children (21). Its’ child-adapted version, the Pediatric Voice-Related Quality of Life survey (PVRQOL), provides a comprehensive view of children’s issues but lacks direct patient feedback (22). PVRQOL is more detailed than the Pediatric Voice Outcomes Survey (PVOS), though PVOS’s length limits its subdomain specificity (23), indicating its potential to measure voice-related quality of life (24).

The above questionnaires measure children’s overall quality of life rather than specific aspects. To measure psychosocial aspects, researchers and clinicians can consider the 9-Item Voice Handicap Index (VHI-9i), adapted from the Voice Handicap Index (VHI) (25). In clinical experience, VHI-9i is time-saving and patient-friendly, increasing its acceptance and practicality (25, 26).

Although the Swallowing Quality of Life questionnaire (SWAL-QOL) mainly focuses on evaluating chewing function, it can also assess communication-related QoL issues with oropharyngeal dysphagia (27). It can be a reference when designing instruments for cleft palate.

2.2 Oronasal fistula

Patients with ONF may experience sinusitis, food impaction, and halitosis due to food entering the nasal cavity through the fistula, as well as speech dysfunction related to the fistula itself (28). PROMs related to ONF can be evaluated using questionnaires designed for nasal functions, speech, and feeding-related issues (Table 1, Part 2).

The Rhino conjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (RQLQ) has been shortened to mini-RQLQ (29) for efficiency in large clinical trials and practice monitoring. It is reliable for patients with stable rhino conjunctivitis between clinic visits (30). While mini-RQLQ has strong measurement properties, its usefulness in patients with cleft palate needs further investigation.

It is reported that ONF can lead to nasal obstruction (31). Thus, the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) is a useful global tool for evaluating patients’ nose obstruction symptoms, correlating well with examination findings (32, 33). Halitosis, causing social discomfort, can be measured by the Halitosis Associated Life-quality Test (HALT), which monitors disease progression. The scale’s goal is to potentially measure change rather than draw conclusions about therapy effectiveness (34). The cut point is 14 and higher indicates halitosis. However, these should be used with organoleptic tests for a comprehensive diagnosis in all cases (35).

Speech impairment related to cleft palate can be assessed using VPIQL, VELO, PVOS, PVRQOL, VHI, and VHL-9i presented, as previously mentioned. VELO also evaluates swallowing problems in ONF patients, though it includes non-specific scales. Eating issues are significant in children with ONF, addressed by the 10-item Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10), which monitors dysphagia severity and treatment efficacy (36). The Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale (MCH-FS) addresses parental concerns about feeding problems, which may otherwise be overlooked in clinical conditions, with a bilingual format and clinical significance indicators (37).

Other pediatric feeding assessments include Behavioral assessment scale of oral functions in feeding (BASOFF) (38), Dysphagia Disorders Survey (DDS) (39), Functional Feeding Assessment modified (FFAm) (40), Standardized Eating Assessment (GVA) (40), Oral Motor Assessment Scale (OMAS) (41), Pediatric Assessment Scale for Severe Feeding Problems (PASSFP) (42), (Schedule for Oral-Motor Assessment) SOMA (43), and Screening Tool of Feeding Problems applied to children (STEP-CHILD) (44). However, many of these scales are too disease-specific for patients with cleft palate or do not align with their feeding behaviors. Despite this, they still hold potential for use in special conditions (45).

2.3 Maxillary hypoplasia

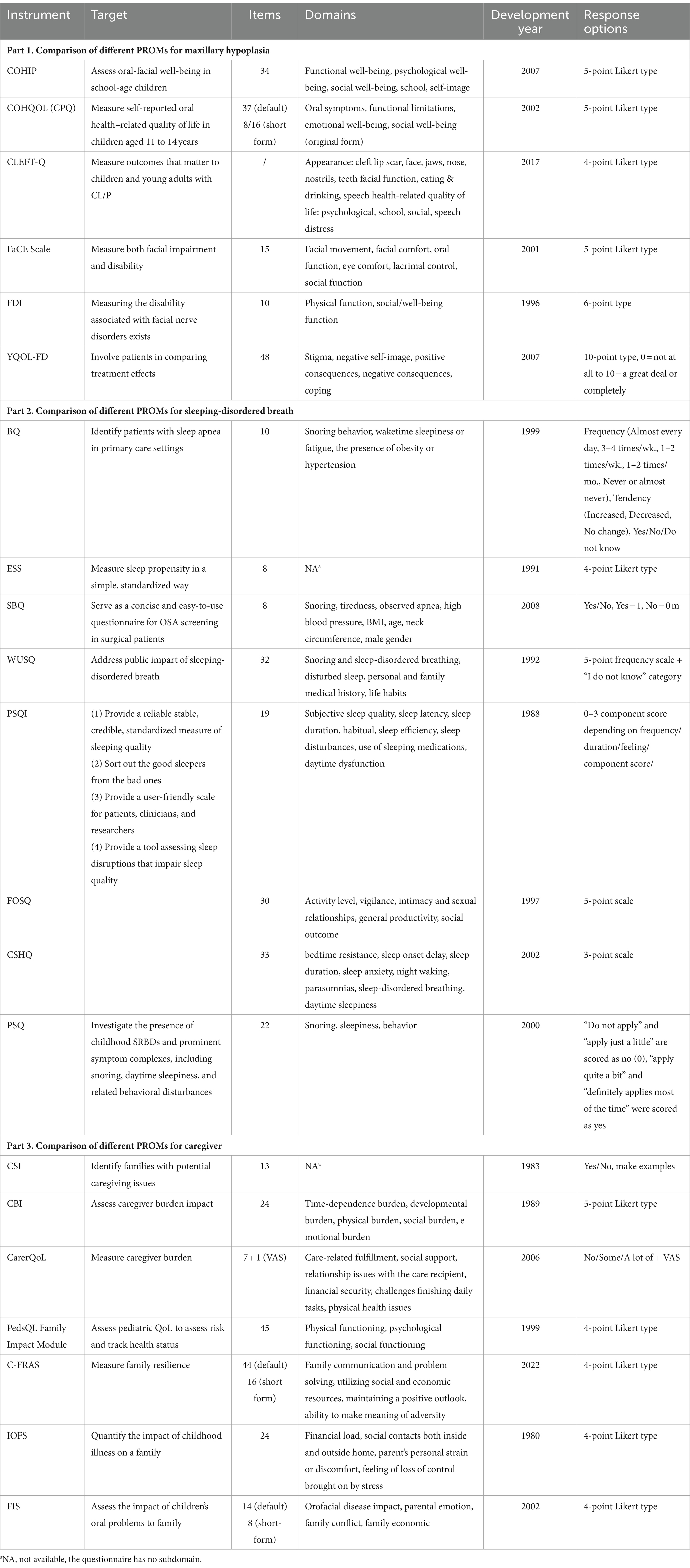

In individuals with cleft palate, the midfacial growth is often disrupted leading to maxillary hypoplasia. This means the maxilla does not develop to its full size and may appear smaller than normal. Additionally, cleft palate can cause malocclusion and other dental issues. Improper orthodontic treatment can also result in maxillary hypoplasia. This condition not only causes dental problems but can also lead to respiratory issues, speech impairment, facial asymmetry, esthetic concerns, and difficulties in chewing. To assess the overall impact of maxillary hypoplasia, several oral health-related questionnaires can be applied (Table 2, Part 1).

Table 2. Comparison of different PROMs for maxillary hypoplasia, sleeping-disordered breath, and caregiver.

Child’s Oral Health Impact Profile (COHIP) is a well-designed tool that has shown excellent reliability in measuring oral-facial well-being among children aged 8–15. It assesses several significant issues in patients with cleft palate and is cleft palate specific. The questionnaire can distinguish differences in oral health-related quality of life between those with craniofacial anomalies and those without (46, 47).

Child Oral Health Quality of Life Questionnaire (COHQOL) consists two components: the Parent-Caregiver Perception Questionnaire (P-CPQ) and the Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ). The CPQ is a self-administered tool measuring oral health-related quality of life in children aged 11–14, originally containing 37 items, with 16-item and 8-item shortened versions developed for clinical use (48–50).

CLEFT-Q, a rigorously developed instrument, includes a series of scales across three domains with 12 minor themes, suitable for patients aged 8 to 29 years. Each scale can be used separately to reduce patient burden, as patients only complete scales relevant to their problems. There is no total score, making it flexible for addressing specific concerns such as appearance, facial function, and health-related quality of life (51–53).

Facial Clinimetric Evaluation Scale (FaCE Scale) is originally developed for evaluating facial paralysis but has been adapted to assess facial dysfunction, a key feature of maxillary hypoplasia. It provides scores across seven areas: facial movement, facial comfort, oral function, eye comfort, lacrimal control, social function, and total score (54).

Facial Disability Index (FDI), a disease-specific instrument, examines physical impairment and psychosocial variables in individuals with facial nerve disorders. It features two domains, each with five items, and domain scores are transformed to a 100-point scale. Its brevity allows for quick completion and immediate score comparison, fitting well in outpatient settings (55).

The Youth Quality of Life-Facial Differences Questionnaire (YQOL-FD) is a craniofacial-specific quality of life module that complements the generic Youth Quality of Life Instrument (YQOL). It is suitable for youth aged 11–18 and readable for children in the fifth grade. The tool highlights the impact of facial differences on QoL from the patient’s perspective, offering a patient-centered profile for comparing treatment effects beyond clinician-derived outcomes of esthetics and function (56). However, it is not specifically customized for patients with cleft palate and may overlook some crucial aspects significant to this population (3).

2.4 Sleep-disordered breath

Patients with cleft palate are more susceptible to SDB. The cleft in the roof of the oral cavity can result in smaller airways and an abnormal nasal cavity, leading to breathing difficulties during sleep. Additionally, surgical repair of the cleft palate may contribute to SDB due to scarring and changes in the shape and function of the palate and surrounding tissues, which can further narrow the airway. Common symptoms of SDB in individuals with cleft palate include loud snoring, gasping or choking during sleep, restless sleep, and daytime sleepiness. The most prevalent condition among these patients is Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), characterized by repeated episodes of partial or complete upper airway collapse during sleep, leading to decreased oxygen levels and disrupted sleep. If left untreated, SDB in individuals with cleft palate can lead to long-term complications such as growth and developmental problems, cognitive deficits, and cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, applying assessment scales to guide timely treatment is essential (Table 2, Part 2).

The Berlin Questionnaire (BQ) identifies patients at risk of sleep apnea by asking risk factors. A patient is considered at high risk for sleep apnea if they exhibit symptoms in at least two categories. Those qualified for only one symptom category are considered as lower risk (57). The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) measures daytime sleepiness, with scores above 16 indicating a high tendency for daytime drowsiness (58). The STOP questionnaire is a brief and simple OSA screening tool for surgical patients, focusing on Snoring, Tiredness, Observed apnea, and high blood Pressure. The STOP-Bang questionnaire (SBQ) includes four additional demographic questions (BMI, Age, Neck circumference, Male gender), enhancing its sensitivity and effectiveness (59, 60). A score of 0–2 on the SBQ implies low risk of OSA, while a score of 3 or more indicates a higher risk. The SBQ is a more reliable instrument for identifying mild, moderate, and severe OSA than the BQ, STOP, and ESS (61).

The Wisconsin University Sleep Questionnaire (WUSQ), adapted from the Basic Northern Sleep Questionnaire, has been translated and validated for consistency (62, 63). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) assesses sleep quality over the previous month, distinguishing transient disturbances from persistent ones. It provides a “global” score indicating the severity of sleep difficulties (64). The Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ) measures how sleepiness affects daily functioning and is suitable for children above the 5th grade. Though designed to evaluate disorders of excessive sleepiness (DOES), it can also measure SDB-related quality of life (65).

Given that most cleft palate patients are children, pediatric-specific scales are necessary. The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) is a parent-report tool diagnosing sleep disorders in school-aged children (4–10) based on a typical week’s sleep behavior (66). The Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ) investigates childhood sleep-related breathing disorders and symptoms like snoring and daytime sleepiness in children aged 2–18 years, making it useful in clinical research when polysomnography is unavailable (67).

2.5 Caregiver QoL

Caregivers’ attitudes influence patients’ recovery, while caregivers’ feelings toward their child’s cleft defect also play a crucial role in the development of the child’s self-esteem (9). While the response of caregivers to their child with cleft palate is well-documented (68), the impact of caregivers’ psychological status on their children needs further study by PROMs (Table 2, Part 3).

The Caregiver Strain Index (CSI) identifies families with potential caregiving issues, with a score above 6 indicating the need for further assessment. However, CSI is designed for patients over 65 and lacks a subjective assessment of caregiving impact (69). The Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) is a multidimensional tool assessing caregiver burden, but dose not account for its impact on caregiver QoL.

The Care-Related Quality of Life Instrument (CarerQoL) includes two scales: CarerQoL-7D, which measures caregiver burden in two positive dimensions and five negative dimensions (70), and CarerQoL-VAS, which determines patients’ happiness by drawing a X on a number axis (71). CarerQoL-7D is widely used for informal caregivers, reflecting the situation of parents with children with cleft palate (72–75).

Caregiver stress can negatively impact families, causing emotional pressure, relationship strain, and health problems. Thus, assessing family impact of caregiver pressure is significant. The PedsQL Family Impact Module, part of the PedsQL measure, assesses parent self-reported QoL to evaluate risk and track health status (76). Parents’ perceptions of their children’s QoL often reflect their own stress levels. The Chinese Family Resilience Assessment Scale (C-FRAS) measures family resilience, with higher scores indicating greater resilience (77), and can be used to assess the resilience of families with a child who has a cleft palate.

The Impact on Family Scale (IOFS) quantifies the impact of childhood illness on families, with higher scores indicating a greater detrimental effect (78). IOFS reliably detects changes, making it a valuable tool for monitoring a family during illness course (79). The scale has been applied in monitoring the family impact of childhood cancer (80) and children with posterior urethral valves (81), obstetrical brachial plexus injury (82) and cleft palate (83). It confirms that having a child with cleft palate affects parents’ QoL (83). The Family Impact Scale (FIS), part of the Parental-Caregivers Perceptions Questionnaire (P-CPQ) (84), quantifies the impact of a child’s oral problems on the family. FIS is valid in determining the impact of orofacial cleft on family QoL (85), and its short form, FIS-8, has shown great internal consistency reliability (86). However, its sociodemographic patterns in China need further research.

3 Conclusion

Compared to traditional doctor-guided evaluation methods, PROMs better capture patients’ perspectives, especially their perceptions of their own health and QoL. PROMs serve as supplementary tools for assessing treatment effectiveness, aiding in clinical decision-making. Their application leads to more personalized care, allowing healthcare providers to tailor treatments to individual patient needs and preferences. PROMs facilitate better communication between patients and healthcare providers by promoting discussions about patient experiences, concerns, and treatment goals, significantly improving patient satisfaction. Medical institutions can assess healthcare quality by tracking PROMs over time.

In summary, PROMs are crucial for patients with cleft palate as they provide unique insights into the patient’s perspective, inform treatment decisions, enhance communication, evaluate healthcare quality, and support research. By applying PROMs, healthcare providers ensure comprehensive, patient-centered care for individuals with cleft palate.

Author contributions

WX: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software. MD: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. MW: Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. ZC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. RY: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. BS: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. HH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82301148); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024T170605); Sichuan Postdoctoral Science Foundation (TB2022005); Research Funding from West China School/Hospital of Stomatology Sichuan University (RCDWJS2024-7); Sichuan University Higher Education Teaching Reform Research Project (SCU10379).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Chen, YH, Liao, YF, Chang, CS, Lu, TC, and Chen, KT. Patient satisfaction and quality of life after orthodontic treatment for cleft lip and palate deformity. Clin Oral Investig. (2021) 25:5521–9. doi: 10.1007/s00784-021-03861-4

2. Mossey, PA, Little, J, Munger, RG, Dixon, MJ, and Shaw, WC. Cleft lip and palate. Lancet. (2009) 374:1773–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60695-4

3. Eckstein, DA, Wu, RL, Akinbiyi, T, Silver, L, and Taub, PJ. Measuring quality of life in cleft lip and palate patients: currently available patient-reported outcomes measures. Plast Reconstr Surg. (2011) 128:518e–26e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822b6a67

4. Bessell, A, Hooper, L, Shaw, WC, Reilly, S, Reid, J, and Glenny, A-M. Feeding interventions for growth and development in infants with cleft lip, cleft palate or cleft lip and palate. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2011) 2011:CD003315. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003315.pub3

5. Sheahan, P, and Blayney, AW. Cleft palate and otitis media with effusion: a review. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). (2003) 124:171–7.

6. Sheahan, P, Miller, I, Sheahan, JN, Earley, MJ, and Blayney, AW. Incidence and outcome of middle ear disease in cleft lip and/or cleft palate. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. (2003) 67:785–93. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(03)00098-3

8. MacLean, JE, Fitzsimons, D, Fitzgerald, DA, and Waters, KA. The spectrum of sleep-disordered breathing symptoms and respiratory events in infants with cleft lip and/or palate. Arch Dis Child. (2012) 97:1058–63. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302104

9. Broder, HL, Smith, FB, and Strauss, RP. Habilitation of patients with clefts: parent and child ratings of satisfaction with appearance and speech. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. (1992) 29:262–7. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1992_029_0262_hopwcp_2.3.co_2

10. Shkoukani, MA, Lawrence, LA, Liebertz, DJ, and Svider, PF. Cleft palate: a clinical review. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. (2014) 102:333–42. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21083

11. Willging, JP . Velopharyngeal insufficiency. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. (1999) 49:S307–9. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(99)00182-2

12. Skirko, JR, Weaver, EM, Perkins, JA, Kinter, S, Eblen, L, Martina, J, et al. Change in quality of life with velopharyngeal insufficiency surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2015) 153:857–64. doi: 10.1177/0194599815591159

13. de Almeida, JR, Park, RCW, Villanueva, NL, Miles, BA, Teng, MS, and Genden, EM. Reconstructive algorithm and classification system for transoral oropharyngeal defects. Head Neck. (2014) 36:934–41. doi: 10.1002/hed.23353

14. Huang, H, Chen, N, Yin, H, Skirko, JR, Guo, C, Ha, P, et al. Validation of the Chinese velopharyngeal insufficiency effects on life outcomes instrument. Laryngoscope. (2019) 129:E395–401. doi: 10.1002/lary.27792

15. Lu, L, Yakupu, A, Wu, Y, Li, X, Zhang, P, Aihaiti, G, et al. Quality of life in patients with velopharyngeal insufficiency in West China. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. (2022) 59:1024–9. doi: 10.1177/10556656211034107

16. Lindeborg, MM, Shakya, P, Pradhan, B, Rai, SK, Gurung, KB, Niroula, S, et al. Nepali linguistic validation of the velopharyngeal insufficiency effects on life outcomes instrument: VELO-Nepali. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. (2020) 57:967–74. doi: 10.1177/1055665620905173

17. Skirko, JR, Santillana, RM, Roth, CT, Dunbar, C, and Tollefson, TT. Spanish linguistic validation of the velopharyngeal insufficiency effects on life outcomes: VELO-Spanish. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. (2018) 6:e1986. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001986

18. Santillana, R, Skirko, J, Roth, C, and Tollefson, TT. Spanish linguistic validation for the velopharyngeal insufficiency effects on life outcomes. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. (2018) 20:331–2. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2018.0005

19. Bruneel, L, Van Lierde, K, Bettens, K, Corthals, P, Van Poel, E, De Groote, E, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with cleft palate: validity and reliability of the VPI effects on life outcomes (VELO) questionnaire translated to Dutch. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. (2017) 98:91–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.04.049

20. Denadai, R, Raposo-Amaral, CE, Sabbag, A, Ribeiro, RA, Buzzo, CL, Raposo-Amaral, CA, et al. Brazilian-Portuguese linguistic validation of the velopharyngeal insufficiency effects on life outcome instrument. J Craniofac Surg. (2019) 30:2308–12. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005679

21. Connor, NP, Cohen, SB, Theis, SM, Thibeault, SL, Heatley, DG, and Bless, DM. Attitudes of children with dysphonia. J Voice. (2008) 22:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.09.005

22. Hartnick, CJ . Validation of a pediatric voice quality-of-life instrument: the pediatric voice outcome survey. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2002) 128:919–22. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.8.919

23. Chen, N, Shi, B, and Huang, H. Velopharyngeal inadequacy-related quality of life assessment: the instrument development and application review. Front Surg. (2022) 9:796941. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.796941

24. Boseley, ME, Cunningham, MJ, Volk, MS, and Hartnick, CJ. Validation of the pediatric voice-related quality-of-life survey. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2006) 132:717–20. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.7.717

25. Caffier, F, Nawka, T, Neumann, K, Seipelt, M, and Caffier, PP. Validation and classification of the 9-item voice handicap index (VHI-9i). J Clin Med. (2021) 10:3325. doi: 10.3390/jcm10153325

26. Rosen, CA, Lee, AS, Osborne, J, Zullo, T, and Murry, T. Development and validation of the voice handicap index-10. Laryngoscope. (2004) 114:1549–56. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200409000-00009

27. McHorney, CA, Martin-Harris, B, Robbins, J, and Rosenbek, J. Clinical validity of the SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE outcome tools with respect to bolus flow measures. Dysphagia. (2006) 21:141–8. doi: 10.1007/s00455-005-0026-9

28. Miranda, BL, Junior, JLA, Paiva, MAF, Lacerda, RHW, and Vieira, AR. Management of Oronasal Fistulas in patients with cleft lip and palate. J Craniofac Surg. (2020) 31:1526–8. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000006213

29. Juniper, EF, and Guyatt, GH. Development and testing of a new measure of health status for clinical trials in rhinoconjunctivitis. Clin Exp Allergy. (1991) 21:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1991.tb00807.x

30. Juniper, EF, Thompson, AK, Ferrie, PJ, and Roberts, JN. Development and validation of the mini Rhinoconjunctivitis quality of life questionnaire. Clin Exp Allergy. (2000) 30:132–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00668.x

31. Dib, GC, Tangerina, RP, Abreu, CEC, Santos, R, and Gregório, LC. Rhinolithiasis as cause of oronasal fistula. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. (2005) 71:101–3. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31294-5

32. Stewart, MG, Witsell, DL, Smith, TL, Weaver, EM, Yueh, B, and Hannley, MT. Development and validation of the nasal obstruction symptom evaluation (NOSE) scale. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2004) 130:157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.09.016

33. Kahveci, OK, Miman, MC, Yucel, A, Yucedag, F, Okur, E, and Altuntas, A. The efficiency of NOSE obstruction symptom evaluation (NOSE) scale on patients with nasal septal deviation. Auris Nasus Larynx. (2012) 39:275–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2011.08.006

34. Kizhner, V, Xu, D, and Krespi, YP. A new tool measuring oral malodor quality of life. Eur Arch Otorrinolaringol. (2011) 268:1227–32. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1518-x

35. Gurpinar, B, Kumral, TL, Sari, H, Tutar, B, and Uyar, Y. A new halitosis screening tool: halitosis finding score derivation and validation. Acta Odontol Scand. (2022) 80:44–50. doi: 10.1080/00016357.2021.1936162

36. Belafsky, PC, Mouadeb, DA, Rees, CJ, Pryor, JC, Postma, GN, Allen, J, et al. Validity and reliability of the eating assessment tool (EAT-10). Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. (2008) 117:919–24. doi: 10.1177/000348940811701210

37. Ramsay, M, Martel, C, Porporino, M, and Zygmuntowicz, C. The Montreal Children's hospital feeding scale: a brief bilingual screening tool for identifying feeding problems. Paediatr Child Health. (2011) 16:147–e17. doi: 10.1093/pch/16.3.147

38. Stratton, M . Behavioral assessment scale of oral functions in feeding. Am J Occup Ther. (1981) 35:719–21. doi: 10.5014/ajot.35.11.719

39. Calis, EA, Veugelers, R, Sheppard, JJ, Tibboel, D, Evenhuis, HM, and Penning, C. Dysphagia in children with severe generalized cerebral palsy and intellectual disability. Dev Med Child Neurol. (2008) 50:625–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03047.x

40. Gisel, EG, Alphonce, E, and Ramsay, M. Assessment of ingestive and oral praxis skills: children with cerebral palsy vs. controls. Dysphagia. (2000) 15:236–44. doi: 10.1007/s004550000033

41. Ortega, ADOL, Ciamponi, AL, Mendes, FM, and Santos, MTBR. Assessment scale of the oral motor performance of children and adolescents with neurological damages. J Oral Rehabil. (2009) 36:653–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.01979.x

42. Crist, W, Dobbelsteyn, C, Brousseau, AM, and Napier-Phillips, A. Pediatric assessment scale for severe feeding problems: validity and reliability of a new scale for tube-fed children. Nutr Clin Pract. (2004) 19:403–8. doi: 10.1177/0115426504019004403

43. Reilly, S, Skuse, D, Mathisen, B, and Wolke, D. The objective rating of oral-motor functions during feeding. Dysphagia. (1995) 10:177–91. doi: 10.1007/BF00260975

44. Seiverling, L, Hendy, HM, and Williams, K. The screening tool of feeding problems applied to children (STEP-CHILD): psychometric characteristics and associations with child and parent variables. Res Dev Disabil. (2011) 32:1122–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.01.012

45. Barton, C, Bickell, M, and Fucile, S. Pediatric Oral motor feeding assessments: a systematic review. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. (2018) 38:190–209. doi: 10.1080/01942638.2017.1290734

46. Broder, HL, McGrath, C, and Cisneros, GJ. Questionnaire development: face validity and item impact testing of the child Oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. (2007) 35:8–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00401.x

47. Broder, HL, and Wilson-Genderson, M. Reliability and convergent and discriminant validity of the child Oral health impact profile (COHIP Child's version). Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. (2007) 35:20–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.0002.x

48. Jokovic, A, Locker, D, and Guyatt, G. Short forms of the child perceptions questionnaire for 11-14-year-old children (CPQ11-14): development and initial evaluation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2006) 4:4. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-4

49. Jokovic, A, Locker, D, Stephens, M, Kenny, D, Tompson, B, and Guyatt, G. Validity and reliability of a questionnaire for measuring child oral-health-related quality of life. J Dent Res. (2002) 81:459–63. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100705

50. Jokovic, A, Locker, D, Stephens, M, Kenny, D, Tompson, B, and Guyatt, G. Measuring parental perceptions of child oral health-related quality of life. J Public Health Dent. (2003) 63:67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2003.tb03477.x

51. Tsangaris, E, Wong Riff, KWY, Goodacre, T, Forrest, CR, Dreise, M, Sykes, J, et al. Establishing content validity of the CLEFT-Q: a new patient-reported outcome instrument for cleft lip/palate. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. (2017) 5:e1305. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001305

52. Klassen, AF, Riff, KWW, Longmire, NM, Albert, A, Allen, GC, Aydin, MA, et al. Psychometric findings and normative values for the CLEFT-Q based on 2434 children and young adult patients with cleft lip and/or palate from 12 countries. CMAJ. (2018) 190:E455–62. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170289

53. Wong Riff, KWY, Tsangaris, E, Forrest, CR, Goodacre, T, Longmire, NM, Allen, G, et al. CLEFT-Q: detecting differences in outcomes among 2434 patients with varying cleft types. Plast Reconstr Surg. (2019) 144:78e–88e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005723

54. Kahn, JB, Gliklich, RE, Boyev, KP, Stewart, MG, Metson, RB, and McKenna, MJ. Validation of a patient-graded instrument for facial nerve paralysis: the FaCE scale. Laryngoscope. (2001) 111:387–98. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200103000-00005

55. VanSwearingen, JM, and Brach, JS. The facial disability index: reliability and validity of a disability assessment instrument for disorders of the facial neuromuscular system. Phys Ther. (1996) 76:1288–98. doi: 10.1093/ptj/76.12.1288

56. Patrick, DL, Topolski, TD, Edwards, TC, Aspinall, CL, Kapp-Simon, KA, Rumsey, NJ, et al. Measuring the quality of life of youth with facial differences. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. (2007) 44:538–47. doi: 10.1597/06-072.1

57. Netzer, NC, Stoohs, RA, Netzer, CM, Clark, K, and Strohl, KP. Using the Berlin questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. (1999) 131:485–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002

58. Johns, MW . A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. (1991) 14:540–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540

59. Chung, F, Yegneswaran, B, Liao, P, Chung, SA, Vairavanathan, S, Islam, S, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. (2008) 108:812–21. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31816d83e4

60. Chung, F, Abdullah, HR, and Liao, P. STOP-Bang questionnaire: a practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. (2016) 149:631–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0903

61. Chiu, H-Y, Chen, P-Y, Chuang, L-P, Chen, N-H, Tu, Y-K, Hsieh, Y-J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP, and Epworth sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep apnea: a bivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. (2017) 36:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.10.004

62. Teculescu, D, Guillemin, F, Virion, J-M, Aubry, C, Hannhart, B, Michaely, J-P, et al. Reliability of the Wisconsin sleep questionnaire: a French contribution to international validation. J Clin Epidemiol. (2003) 56:436–40. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00029-5

63. Young, T, Palta, M, Dempsey, J, Skatrud, J, Weber, S, and Badr, S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. (1993) 328:1230–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704

64. Buysse, DJ, Reynolds, CF, Monk, TH, Berman, SR, and Kupfer, DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. (1989) 28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

65. Weaver, TE, Laizner, AM, Evans, LK, Maislin, G, Chugh, DK, Lyon, K, et al. An instrument to measure functional status outcomes for disorders of excessive sleepiness. Sleep. (1997) 20:835–43.

66. Owens, JA, Spirito, A, and McGuinn, M. The Children's sleep habits questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep. (2000) 23:1043–51. doi: 10.1093/sleep/23.8.1d

67. Chervin, RD, Hedger, K, Dillon, JE, and Pituch, KJ. Pediatric sleep questionnaire (PSQ): validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness, and behavioral problems. Sleep Med. (2000) 1:21–32. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(99)00009-X

68. Turner, SR, Rumsey, N, and Sandy, JR. Psychological aspects of cleft lip and palate. Eur J Orthod. (1998) 20:407–15. doi: 10.1093/ejo/20.4.407

69. Robinson, BC . Validation of a caregiver strain index. J Gerontol. (1983) 38:344–8. doi: 10.1093/geronj/38.3.344

70. van Dam, PH, Achterberg, WP, and Caljouw, MAA. Care-related quality of life of informal caregivers after geriatric rehabilitation. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2017) 18:259–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.09.020

71. Brouwer, WBF, van Exel, NJA, van Gorp, B, and Redekop, WK. The CarerQol instrument: a new instrument to measure care-related quality of life of informal caregivers for use in economic evaluations. Qual Life Res. (2006) 15:1005–21. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-5994-6

72. Hoefman, RJ, van Exel, NJA, Foets, M, and Brouwer, WBF. Sustained informal care: the feasibility, construct validity and test-retest reliability of the CarerQol-instrument to measure the impact of informal care in long-term care. Aging Ment Health. (2011) 15:1018–27. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.575351

73. Lutomski, JE, van Exel, NJA, Kempen, GIJM, Moll van Charante, EP, den Elzen, WPJ, Jansen, APD, et al. Validation of the care-related quality of life instrument in different study settings: findings from the older persons and informal caregivers survey minimum DataSet (TOPICS-MDS). Qual Life Res. (2015) 24:1281–93. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0841-2

74. van de Ree, CLP, Ploegsma, K, Kanters, TA, Roukema, JA, De Jongh, MAC, and Gosens, T. Care-related quality of life of informal caregivers of the elderly after a hip fracture. J Patient Rep Outcomes. (2017) 2:23. doi: 10.1186/s41687-018-0048-3

75. Baji, P, Golicki, D, Prevolnik-Rupel, V, Brouwer, WBF, Zrubka, Z, Gulácsi, L, et al. The burden of informal caregiving in Hungary, Poland and Slovenia: results from national representative surveys. Eur J Health Econ. (2019) 20:5–16. doi: 10.1007/s10198-019-01058-x

76. Varni, JW, Sherman, SA, Burwinkle, TM, Dickinson, PE, and Dixon, P. The PedsQL family impact module: preliminary reliability and validity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2004) 2:55. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-55

77. Leung, JTY, Shek, DTL, and Tang, CM. Development and validation of the Chinese family resilience scale in families in Hong Kong. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:1929. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20031929

78. Antiel, RM, Adzick, NS, Thom, EA, Burrows, PK, Farmer, DL, Brock, JW 3rd, et al. Impact on family and parental stress of prenatal vs postnatal repair of myelomeningocele. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2016) 215:522.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.045

79. Stein, RE, and Riessman, CK. The development of an impact-on-family scale: preliminary findings. Med Care. (1980) 18:465–72. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198004000-00010

80. Islam, MZ, Farjana, S, and Efa, SS. Impact of childhood cancer on the family: evidence from Bangladesh. Heliyon. (2021) 7:e06256. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06256

81. Tan, PSP, Mallitt, K-A, McCarthy, HJ, and Kennedy, SE. The impact of caring for children with posterior urethral valves. Acta Paediatr. (2021) 110:1025–31. doi: 10.1111/apa.15516

82. DeMatteo, C, Bain, JR, Gjertsen, D, and Harper, JA. 'Wondering and waiting' after obstetrical brachial plexus injury: are we underestimating the effects of the traumatic experience on the families? Plast Surg (Oakv). (2014) 22:183–7. doi: 10.1177/229255031402200313

83. De Cuyper, E, Dochy, F, De Leenheer, E, and Van Hoecke, H. The impact of cleft lip and/or palate on parental quality of life: a pilot study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. (2019) 126:109598. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.109598

84. Gilchrist, F, Rodd, H, Deery, C, and Marshman, Z. Assessment of the quality of measures of child oral health-related quality of life. BMC Oral Health. (2014) 14:40. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-40

85. Agnew, CM, Foster Page, LA, Hibbert, S, and Thomson, WM. Family impact of child Oro-facial cleft. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. (2020) 57:1291–7. doi: 10.1177/1055665620936442

Keywords: quality of life, cleft palate, patient-reported outcomes measure, velopharyngeal insufficiency, patient perception

Citation: Xia W, Du M, Wu M, Chen Z, Yang R, Shi B and Huang H (2024) Patient-reported outcomes measure for patients with cleft palate. Front. Public Health. 12:1469455. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1469455

Edited by:

Jing Kang, King’s College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Nina Musurlieva, Plovdiv Medical University, BulgariaCopyright © 2024 Xia, Du, Wu, Chen, Yang, Shi and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hanyao Huang, aHVhbmdoYW55YW9fY25Ac2N1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Wenbo Xia

Wenbo Xia Meijun Du

Meijun Du Min Wu1

Min Wu1 Renjie Yang

Renjie Yang Hanyao Huang

Hanyao Huang