- 1Department of Surgery, University of Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

- 2University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

- 3Department of Economics and Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

- 4Department of Surgery, Section of Plastic Surgery, University of Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

- 5University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Global Response Medicine, Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico

- 6Universitetet i Oslo, Oslo, Norway

- 7Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogota, Colombia

- 8Universidad Tamaulipeca, Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico

- 9Team fEMR, St Clair Shores, MI, United States

- 10Center for Global Health, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

- 11Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

- 12Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

Introduction: Shortages of health professionals is a common problem in humanitarian settings, including among migrants and refugees at the US-Mexico border. We aimed to investigate determinants and recruitment recommendations for working with migrants to better understand how to improve health professional participation in humanitarian efforts.

Methods: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with health professionals working with migrants at the US-Mexico border in Matamoros and Reynosa, Mexico. The study aimed to identify motivations, facilitators, barriers, and sacrifices to humanitarian work, and recommendations for effective learning approaches to increase participation. Participants included health professionals working within humanitarian organizations to deliver healthcare to migrants living in non-permanent encampments. Interviews lasted approximately 45 min and were analyzed in NVivo14 using a validated codebook and team-based methodology.

Results: Among 27 participants, most were female (70%) with median age 32. Health professionals included nurses (41%), physicians (30%), logisticians (11%), social workers (7%), an EMT (4%), and a pharmacist (4%) from the US (59%), Mexico (22%), Cuba (11%), Peru (4%), and Nicaragua (4%) working for four organizations. Participants expressed internal motivations for working with migrants, including a desire to help vulnerable populations (78%), past experiences in humanitarianism (59%), and the need to address human suffering (56%). External facilitators included geographic proximity (33%), employer flexibility (30%), and logistical support (26%). Benefits included improved clinical skills (63%), sociocultural learning (63%), and impact for others (58%). Negative determinants included sacrifices such as career obligations (44%), family commitments (41%), and safety risks (41%), and barriers of limited education (44%) and volunteer opportunities (37%). Participants criticized aspects of humanitarian assistance for lower quality care, feeling useless, and minimizing local capacity. Recommendations to increase the health workforce caring for migrants included integration of humanitarian training for health students (67%), collaborations between health institutions and humanitarian organizations (52%), and improved logistical and mental health support (41%).

Conclusion: Health professionals from diverse roles and countries identified common determinants to humanitarian work with migrants. Recommendations for recruitment reflected feasible and collaborative approaches for professionals, organizations, and trainees to pursue humanitarian health. These findings can be helpful in designing interventions to address workforce shortages in humanitarian migrant contexts.

1 Introduction

Health worker shortages are one of the most pressing problems affecting humanitarian and global health settings (1). This burden is exacerbated in low-middle income countries (LMICs), as 83 of 186 countries did not meet minimum health professional thresholds as outlined by the World Health Organization (2). While multiple components are needed for quality care delivery including adequate resources, access pathways, and political willingness, availability and capacity of health workers remains one of the hardest to solve in resource-constrained environments (3). With more than 100 million forcibly displaced persons worldwide depending on humanitarian health systems for necessary care (4), determining how to better motivate, recruit, and empower health professionals to work in such systems is imperative to optimizing migrant care (3). At the US-Mexico border, over 2.4 million migrants annually are seeking safe passage into the United States, with drastic increases in recent years (5). There, asylum seekers and refugees are living in non-permanent encampments lacking basic public health measures, face increased risks for disease and violence, and depend on humanitarian organizations for basic medical care (6). Despite increased health needs and potential acuity of vulnerable migrants at the US-Mexico border, there is a dearth of health professionals working with this population (6).

It is unclear why health worker shortages remain such a persistent problem in humanitarian and other low-resource health contexts (7, 8). Some factors are well-known, including a lack of compensation, fear of burnout or emotional exhaustion, and concerns for safety (8–11). In 2023, 2,562 incidents of violence against health professionals working in conflict settings were reported across 30 countries, a 25% increase from the previous year (12). Additional hypotheses include a lack of humanitarian career development pathways and limited opportunities for education among health professional students (13). Studies aimed at investigating motivations for humanitarian health work have demonstrated that religious and moral motivations, self-perceived usefulness, increased compensation, training opportunities, and leadership development can all incentivize health workers to work in these contexts (8, 14, 15). Some efforts have explored the impact of medical education initiatives to address health worker shortages in underserved areas, including exposing medical students to global health, service-learning opportunities, and increasing admissions of students from these areas (16, 17). However, many of these efforts focus specifically on rural or global health and fail to account for the specific characteristics of humanitarian contexts including safety risks, acute mobilization, and shorter-term commitments (17). Even less is understood about health worker motivations to care specifically for migrants in humanitarian settings, including refugees and asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border (18).

In this study, we aimed to investigate the determinants which motivate health professionals to work with migrant populations at the US-Mexico border, as well as recommendations for motivating others to address health workforce shortages among refugee populations. Specifically, we sought to understand the internal motivations and sacrifices, external facilitators and barriers, and challenges of humanitarian aid experienced by health professionals caring for migrants at the US-Mexico border. These findings could prove valuable in understanding best practices to promote facilitators, mitigate barriers, and enhance recruitment of qualified health professionals to improve health worker availability for vulnerable migrant populations.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

To determine the motivations, facilitators, sacrifices, barriers, and recruitment strategies for humanitarian health professionals, a qualitative study with a phenomenological approach was undertaken. This methodology was considered most appropriate given the complex internal and external, individual-centered factors involved in the study question and the opportunity to elicit detailed explanations provided by qualitative methods (19). First, a semi-structured interview script was created following a literature search of qualitative studies examining the experiences of health professionals working in migrant and other humanitarian contexts (20). Preliminary questions were content validated by administering the interview and receiving feedback from health professionals working at the US-Mexico border (n = 4). Following clarification of questions and purging repetitive items, the final interview script was designed to last 45 min and contained 25 items covering participant characteristics, incentives and disincentives, and tangible solutions to address health workforce shortages (Supplementary material 1).

2.2 Study setting and participants

This study took place at the US-Mexico border in Matamoros and Reynosa, Mexico. These study sites were selected as they are two of the major points of entry for those seeking asylum in the United States, and where migrant encampments have been established following changes to US immigration policy beginning in 2019. In these locations, migrants including asylum seekers and refugees live in non-permanent encampments with limited access to public health measures and face increased exposure to disease and violence (6). Humanitarian non-governmental organizations provide most health and other social services to migrants in these locations, while asylum seekers await processing into the US for indeterminate amounts of time (21). Global Response Medicine (GRM) and Médicos Sin Fronteras (MSF) are two of the major organizations providing physical and mental health services, respectively, to these populations in Matamoros and Reynosa (22). Eligible participants for this study included health professionals, defined as those delivering clinical care or health services to migrants residing within these camps. Such professionals included physicians, nurses, emergency medical technicians, logisticians, social workers, physical therapists, and clinical psychologists. Participants spoke English, Spanish, or both and were required to have worked with migrants for at least 1 week. Lawyers, paralegals, legal advocates for asylum seekers, and others without formal health professional training or limited clinical experience with migrants were excluded from this study.

2.3 Data collection

The first round of interviews was conducted in Matamoros, Mexico in the main migrant encampment in July 2020. The second round was conducted in February 2023, in Reynosa, Mexico in four camps located throughout the city. At both locations, a snowball sampling method was utilized to recruit participants with diverse ages, roles, and humanitarian experiences. First, investigators approached health professionals from GRM and MSF within the migrant camps and at established clinical sites. These participants were asked to recommend additional eligible persons from other humanitarian organizations who may be interested in participating. All interviews were administered by a bilingual, qualitative researcher who was not affiliated with a local humanitarian organization, and in a private location in English or Spanish according to patient preference. Interviews were audio recorded with the EasyVoiceRecorder app on iPhone and uploaded to a secure DropBox (Dropbox, Inc.; San Francisco United States) only available to study researchers. Interviews were continued until data saturation was reached, defined as the cessation of new themes according to preliminary analysis of the study team.

2.4 Data analysis

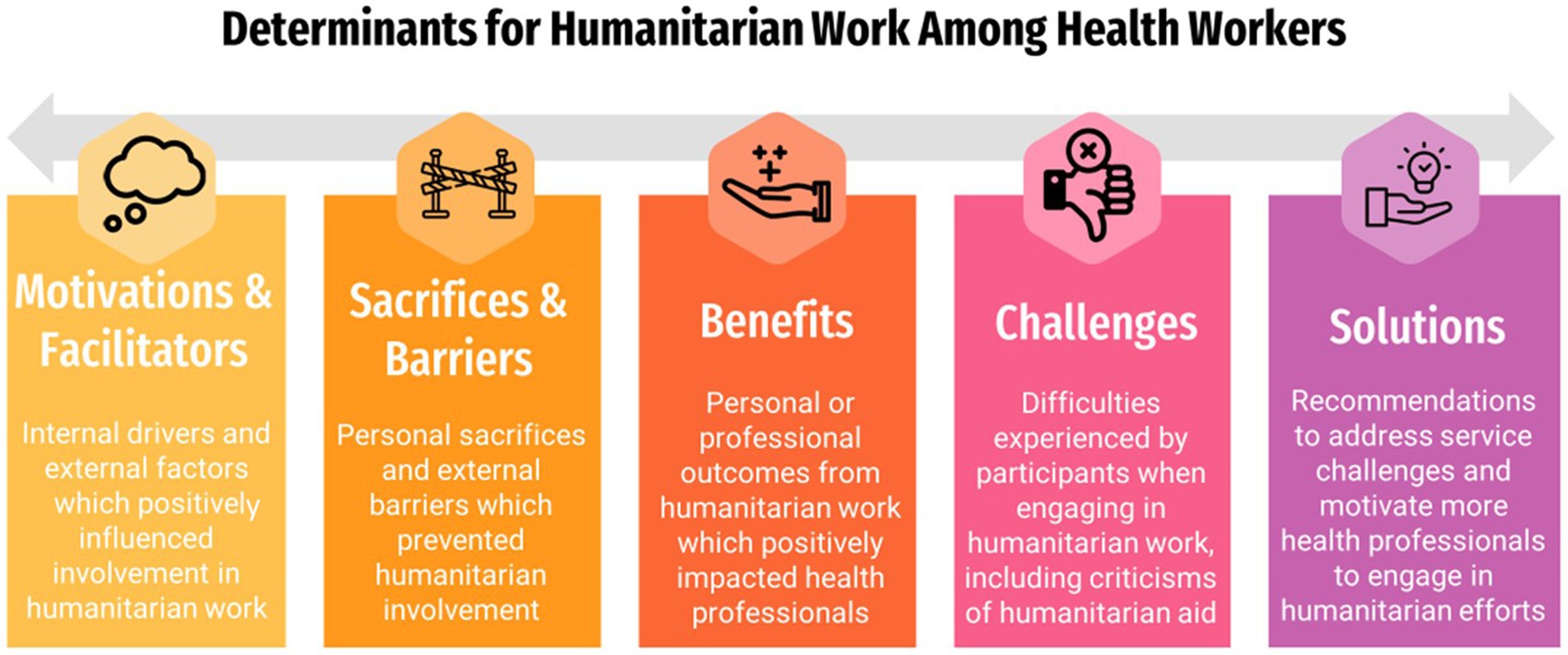

Participants were assigned a numeric code to further guarantee anonymity and interviews were transcribed verbatim in Microsoft Word. Analysis was conducted using a team-based content analysis approach with a validated codebook (23). Specifically, two researchers underwent inductive immersion into the transcripts to develop a codebook with major themes, which then underwent an interactive process of independent coding, calculating interrater agreement, and refinement to clarify themes (Supplementary material 2). Following three rounds of iteration, a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.79 (κ = 0.79) was achieved and considered adequate (24). The final codebook contained 61 subthemes categorized into seven major themes: motivations, facilitators, benefits, sacrifices, barriers, challenges, and solutions (Figure 1). Transcripts were coded in NVivo14 (QSR International, Burlington, MA, United States) and theme frequencies were calculated. Quotes were selected to represent a diverse range of participants and translated into English. Measures were taken to ensure trustworthiness of data including (i) using a team-based and validated coding method, (ii) independent and cooperative data analytic techniques by multiple study members, (iii) member checking with health professionals on the research team, and (iv) consensus on final results by research members.

Figure 1. Major themes describing determinants to work with migrants in humanitarian contexts among health professionals in Matamoros and Reynosa, Mexico.

2.5 Ethical compliance

This study adheres to SRQR guidelines for qualitative research (25).

3 Results

3.1 Participant characteristics

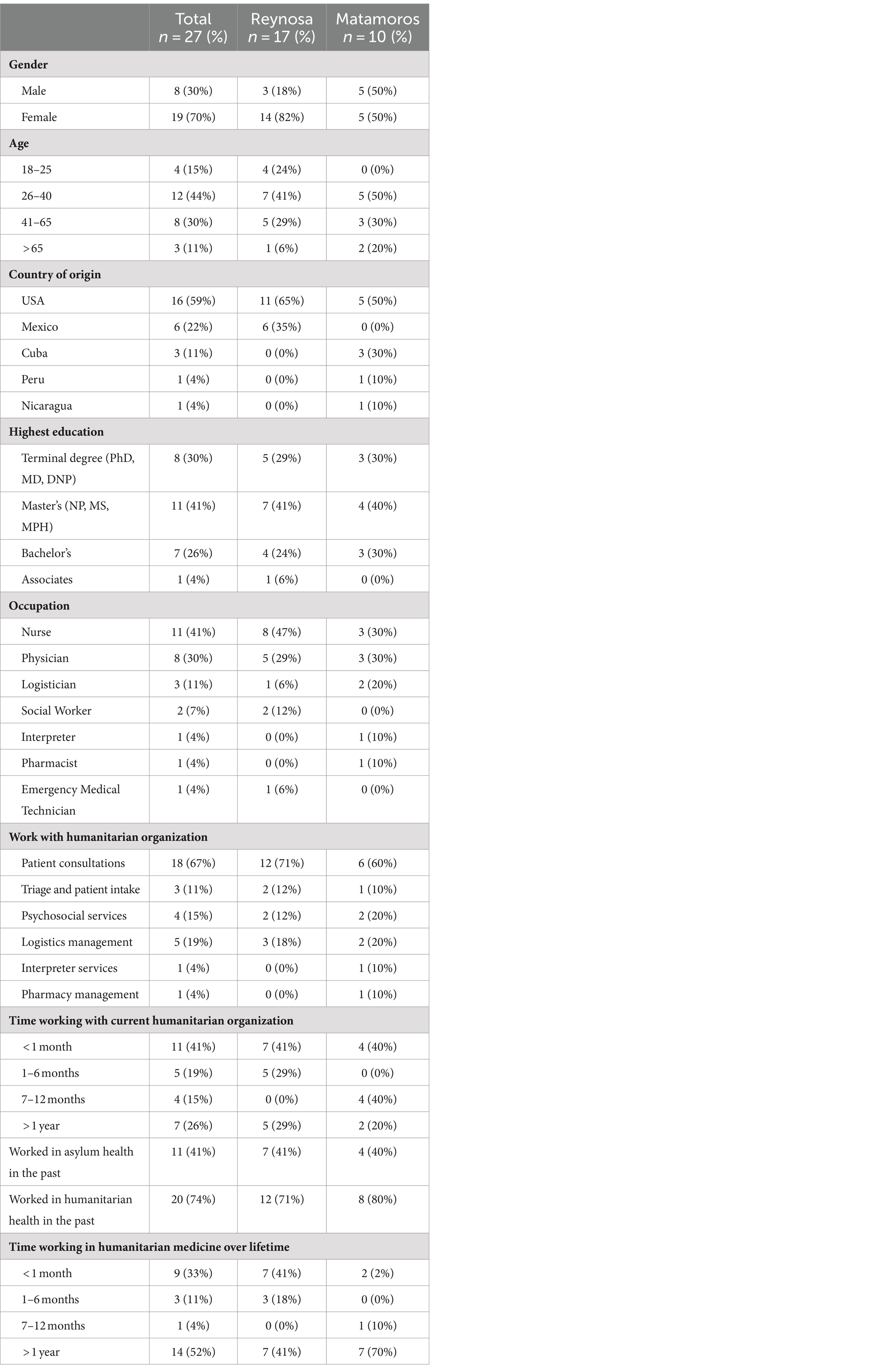

Twenty-seven interviews were conducted among humanitarian health workers in Reynosa (n = 17) and Matamoros, Mexico (n = 10; Table 1). Participants were mostly female (70%), with ages ranging from 22 to 67 years old (median = 32, IQR = 29–54). Participants hailed from the United States (59%), Mexico (22%), Cuba (11%), Peru (4%), and Nicaragua (4%), with varying levels of education and professional roles. Two-thirds performed patient consultations: “I am a general physician. So what I normally do is consult any patient that arrives: chronic patients, children, well-child visits, prenatal care, or whatever arrives, I administer treatments or any other procedure you would do in a consult” -Physician. Other roles included doing triage and patient intake (11%), providing psychosocial services (15%), logistics management (19%), interpreter services (4%), and pharmacy management (4%). There was a mix of short-term volunteers (41% <1 month) and long-term humanitarian workers (26% >1 year), with many having experience in other humanitarian settings (74%) and specifically with asylum seeker populations (41%). Participants from Matamoros had a higher likelihood of working in the camp for a longer period of time (>6 months) than those from Reynosa (p = 0.049; Figure 2).

Table 1. Participant characteristics among humanitarian health workers in Reynosa and Matamoros, Mexico.

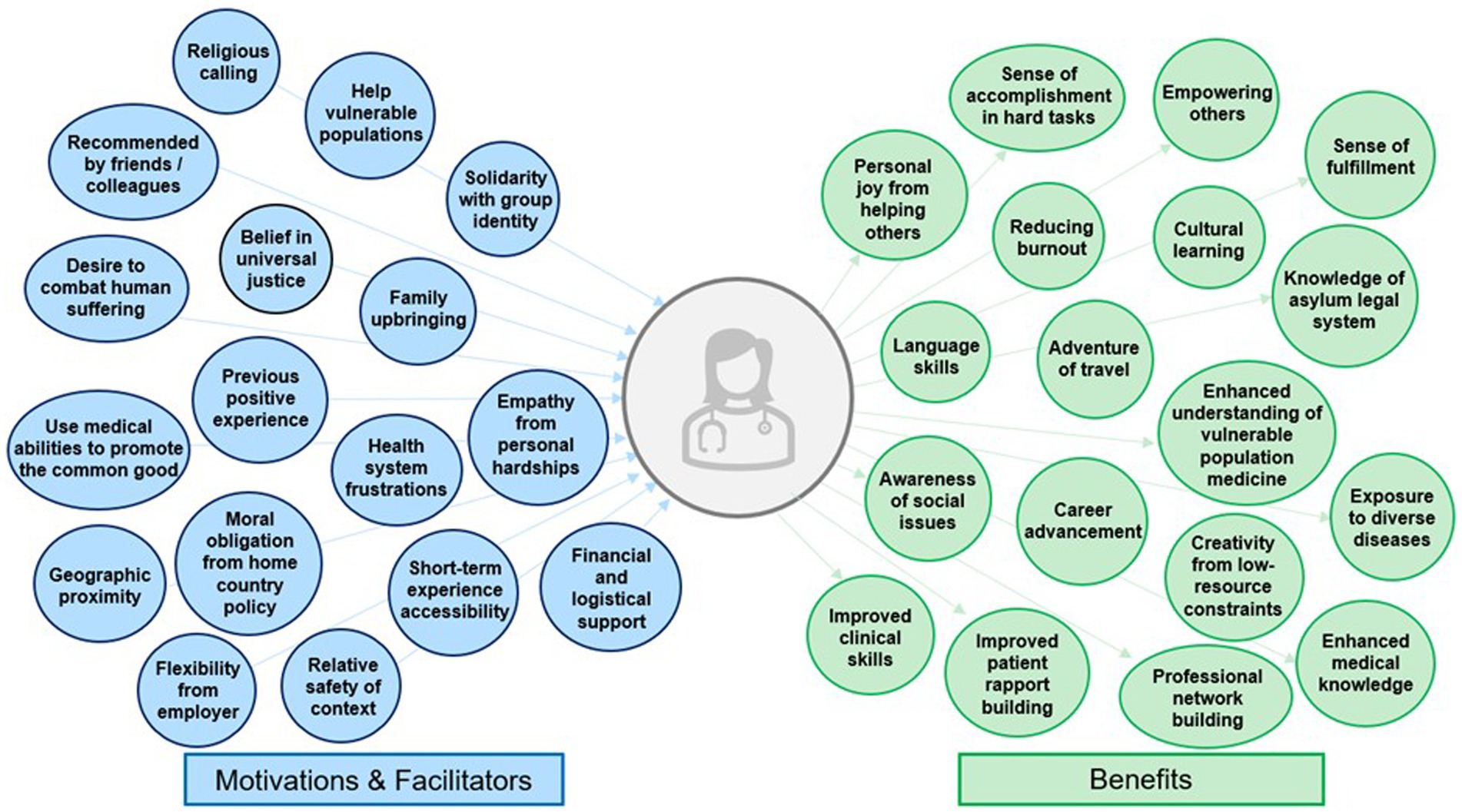

Figure 2. Subthemes of internal motivations, external facilitators, and benefits to working with migrants in humanitarian contexts among health professionals in Matamoros and Reynosa, Mexico.

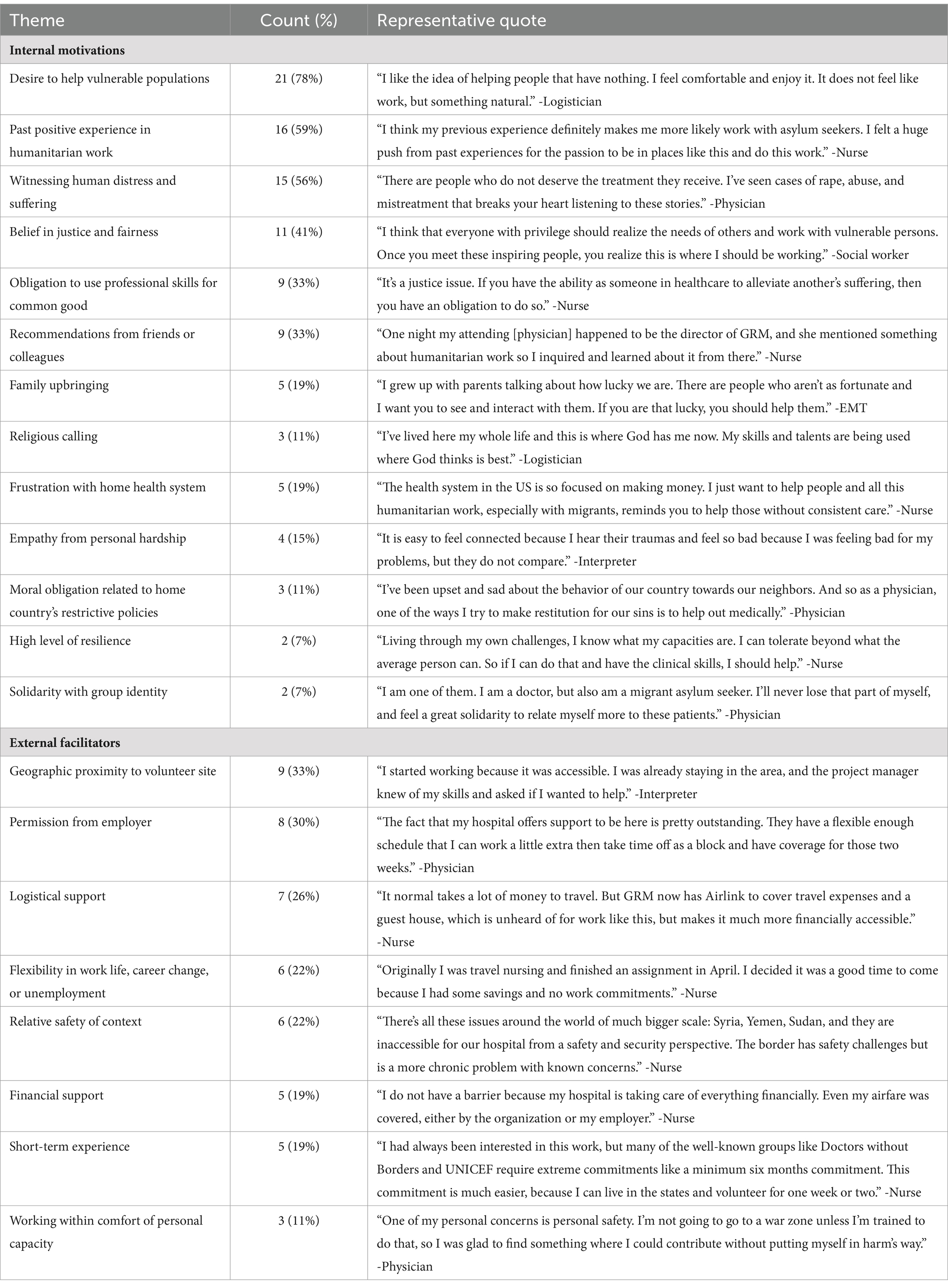

3.2 Motivations

Participants identified internal motivations to pursue humanitarian health work with migrants. Most commonly, participants expressed a personal desire to help vulnerable populations (78%; Table 2). There were multiple components of personal identity which motivated participation, including a belief in universal justice (41%), using one’s skills and privilege as a health professional for good (33%), a religious calling (11%), and family upbringing which encouraged service work (19%). Others expressed having a high level of personal resilience (7%), which they believed obligated them to humanitarian work given their unique persistence. Empathy was commonly mentioned, as participants witnessed the intense suffering of refugees (56%) or had undergone their own hardships (15%). Two providers from Matamoros who were asylum seekers themselves felt an especially deep form of solidarity and call to serve this population (7%). Some had positive experiences in the past with humanitarian or disaster relief work which inspired them to seek further opportunities (59%), while others were motivated by recommendations from colleagues and mentors (33%). Participants reported being frustrated with their home health systems (19%), which prioritized efficiency, revenue generation, and protocolization above care for those needing it most. These professionals hoped that doing humanitarian work could provide an antidote to burnout and recenter their original motivations for pursuing a health career: to care for others. Some motivations were unique to work at the US-Mexico border. US participants expressed a moral obligation to care for migrants at their Border, as they attributed the vulnerable health status and residence in camps of migrant patients to restrictive US immigration policy, which they felt responsible to reconcile (11%).

Table 2. Internal motivations and external facilitators to work with migrants in humanitarian contexts among health professionals in Reynosa and Matamoros, Mexico.

3.3 Facilitators

Participants expressed external facilitators which allowed them to do humanitarian work. The greatest facilitator was employer related. Among full-time humanitarian workers, they appreciated having employment which allowed them to use their skills while addressing a social problem. For short-term volunteers traveling from the US, employer support was a key facilitator (30%). In some cases, clinicians received salary or logistical support for their humanitarian work (19%), facilitated by employer-sponsored disaster, humanitarian, or global health institutes with the funding and flexibility to allocate this time. Participants in Reynosa were more likely to mention employer support, as many worked for institutions with established partnership to GRM’s Reynosa project. More commonly, participants sacrificed personal vacation time, were between jobs, or intentionally structured their careers with the freedom to volunteer, such as the case among travel nurses or career humanitarians (22%). A key facilitator even for seasoned humanitarians was logistical support from the organization, as GRM provided free housing and travel (26%). For those sacrificing vacation or salary, this support proved financially and emotionally beneficial. Finally, the US-Mexico border context yielded additional facilitators leading to commitment to do this work. Participants expressed that most organizations require commitments of months to years to do humanitarian work, place workers in distant and unfamiliar contexts, and may require willingness to work in conflict and other unsafe areas. While participants recognized safety concerns at the US-Mexico border, particularly with the presence of cartels, they felt that the opportunity to volunteer for shorter amounts of time (19%), proximity to home for US clinicians (33%), and relative safety (22%) increased their ability to dedicate time to this work.

3.4 Benefits

Health professionals identified multiple benefits to working with migrants. First, most expressed feeling a personal joy, fulfillment and increased sense of purpose from helping others and making a positive difference (58%): “It feels good to know you have helped someone, knowing you were a face that made them seen and valued despite what the rest of the world is telling. I enjoy being able to affirm people’s value in that way.” -Nurse. Others felt accomplished recruiting and empowering others to care for vulnerable migrants (22%): “The most satisfying piece is enabling people to do this work for the first time and in a professional, respectful, appropriate way. My hope is they go off and find a piece of this world which inspires them to keep doing this work.” -Nurse. Many appreciated the adventure of travel (22%) and increasing their network of colleagues with similar values and career interests (44%). Most benefited from learning about new cultures, as asylum seekers with diverse beliefs arrived from all over the world, particularly Latin America and the Caribbean (63%): “The biggest benefit is meeting people from all over the world. Listening to their stories and having friendships from other countries including with volunteers. It is beautiful to experience new places through the stories of others” -Logistician. Four clinicians even improved their Spanish language skills through patient consultations and collaboration with Mexican physicians (15%).

US workers gained a heightened awareness of social issues, particularly the politico-legal dimensions of immigration and asylum. 37% felt that their work with asylum seekers changed their perception on the best way to deliver care to vulnerable groups, including the importance of psychosocial issues, preventive care, and empowering migrant populations by involving them in health service co-design. Participants reported new clinical skills from the difficulty of this work, including caring for patients requiring extensive social services, treating diseases which were uncommon at home, and using creativity to provide quality care in a resource-constrained environment (63%). They reported improved care delivery methods and ways of relating to patients, particularly when language and resource barriers impaired care. Clinicians believed working with migrants made them better health professionals for their improved clinical skills, medical knowledge, and rapport-building: “I’ve gained so much knowledge, especially working in this context. When I started, I had a ‘school ideology’ based in North American textbooks but have learned how to integrate needed skills and learning. I’m always seeing the sickest patients, so that pushes me to do all I can for them. It has helped me grow into a better clinician” -Physician.

3.5 Sacrifices

Participants also counted personal sacrifices which disincentivized them from humanitarian work. Most frequently mentioned were career obligations, as many found it difficult to sacrifice time from work or devote vacation to humanitarian work (44%). While many reported improved patient skills, most employers did not value humanitarian work in a way that facilitated career rewards. Physicians more frequently mentioned this struggle when compared with other health professionals, as time away had to be compensated by practice partners. Participants reported financial sacrifices, including forgoing salary and self-funding travel and lodging to do this work (26%). Family commitments were second most common (41%). First-time volunteers expressed wanting to work with migrants earlier but not wanting to leave children or partners to do so. Long-term humanitarian professionals found it harder to establish long-term connections to a home base area and described the challenge of living a nomadic lifestyle (11%). Almost half of participants sacrificed safety and comfort for humanitarian work, causing nervousness when becoming involved (41%). Finally, one-third listed emotional difficulties, including witnessing intense human suffering and stark health inequities, leading to an emotional burden and occasional burnout (33%). One-third of participants explicitly stated they encountered no or negligible sacrifices to their humanitarian work (33%). Those living close to the border including Mexican physicians, asylum seeker health workers, and US clinicians residing in border states were more likely to report having no sacrifices to humanitarian work.

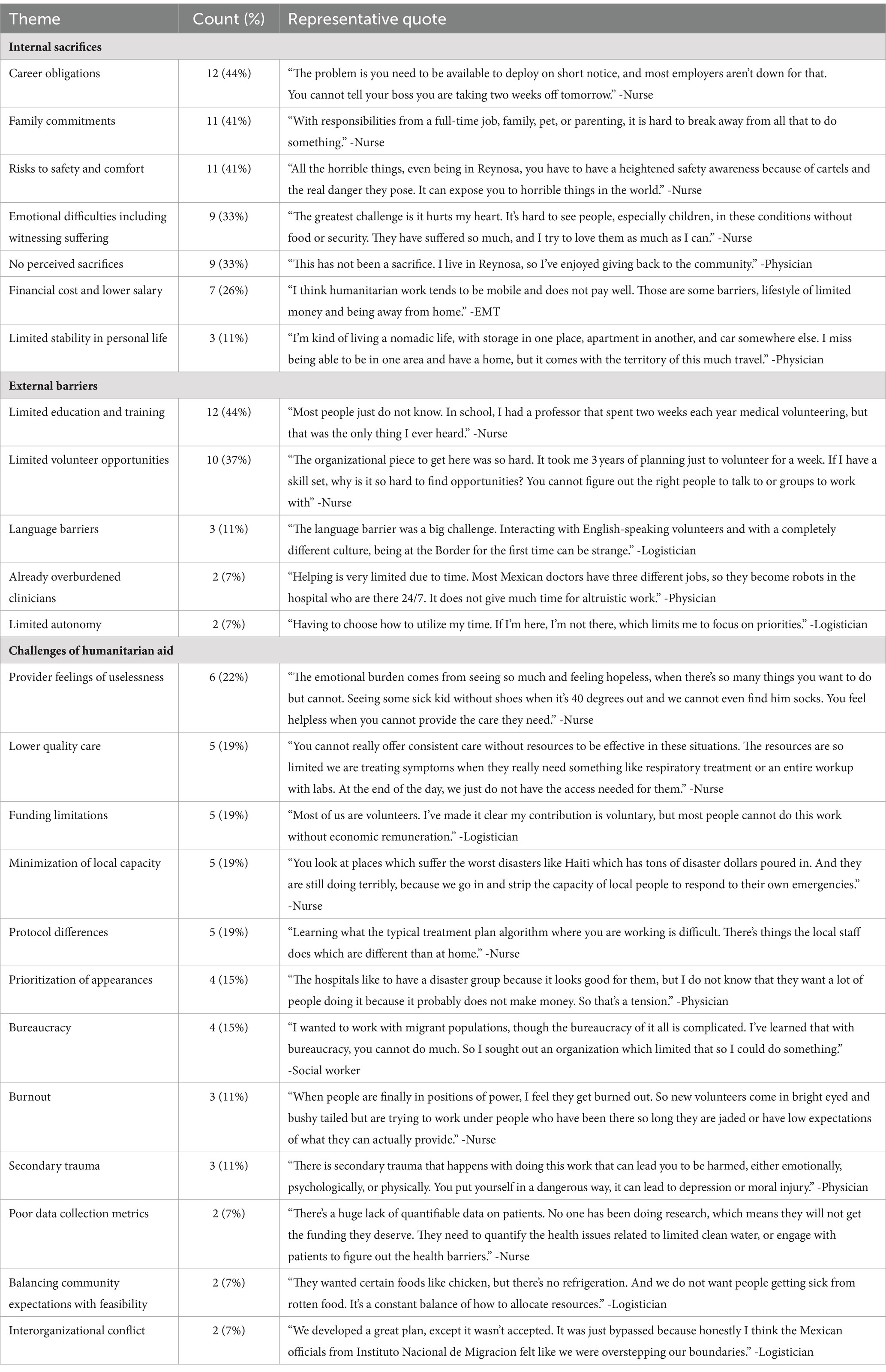

3.6 Barriers and challenges of humanitarian aid

Alongside personal sacrifices, participants cited external barriers to humanitarian health work, including overall criticisms of the field. Barriers included limited knowledge, education, and career development in humanitarian activities (44%). From the time of being students to fully certified clinicians, participants struggled to learn about, apply, and be accepted to volunteer with assistance groups (37%). Most actively sought out extracurricular or service-oriented volunteering but discovered limited long-term career development opportunities, as few planned academic or clinical careers around humanitarian work. Certain aspects of clinical work challenged participants’ effectiveness, including language barriers with primarily Spanish and Haitian Creole speaking patients (11%), limited autonomy depending on local delivery structures (7%), and unfamiliar protocols with different standards of care from typical practice (19%). Health professionals criticized aspects of humanitarian aid generally, including that organizations did not track reliable patient care metrics (7%), had limited resources and funding (19%), and created tensions between migrant community expectations with feasible resource provision (7%). Some professionals believed that quality standards were being lowered due to a lack of resources and objective accountability (22%). Five worried that the presence of humanitarian organizations could unintentionally minimize the capacity of local communities and governments to help themselves, particularly when done without equitable partnership (19%). Many worried that the rapid turnover and varied clinical specialties of volunteers limited consistency and standardization. Finally, participants expressed frustration with bureaucracy of humanitarianism (15%), the prioritization of appearances over quality work (15%), and conflicts between overlapping organizations (7%). Overall, first-time volunteers were just as likely to criticize humanitarian aid as experienced participants, as there was no association between the number of previous humanitarian experiences and likelihood of a participant to share critiques (Table 3).

Table 3. Perspectives on internal sacrifices, external barriers, and common challenges to humanitarian assistance from health professionals in Reynosa and Matamoros, Mexico.

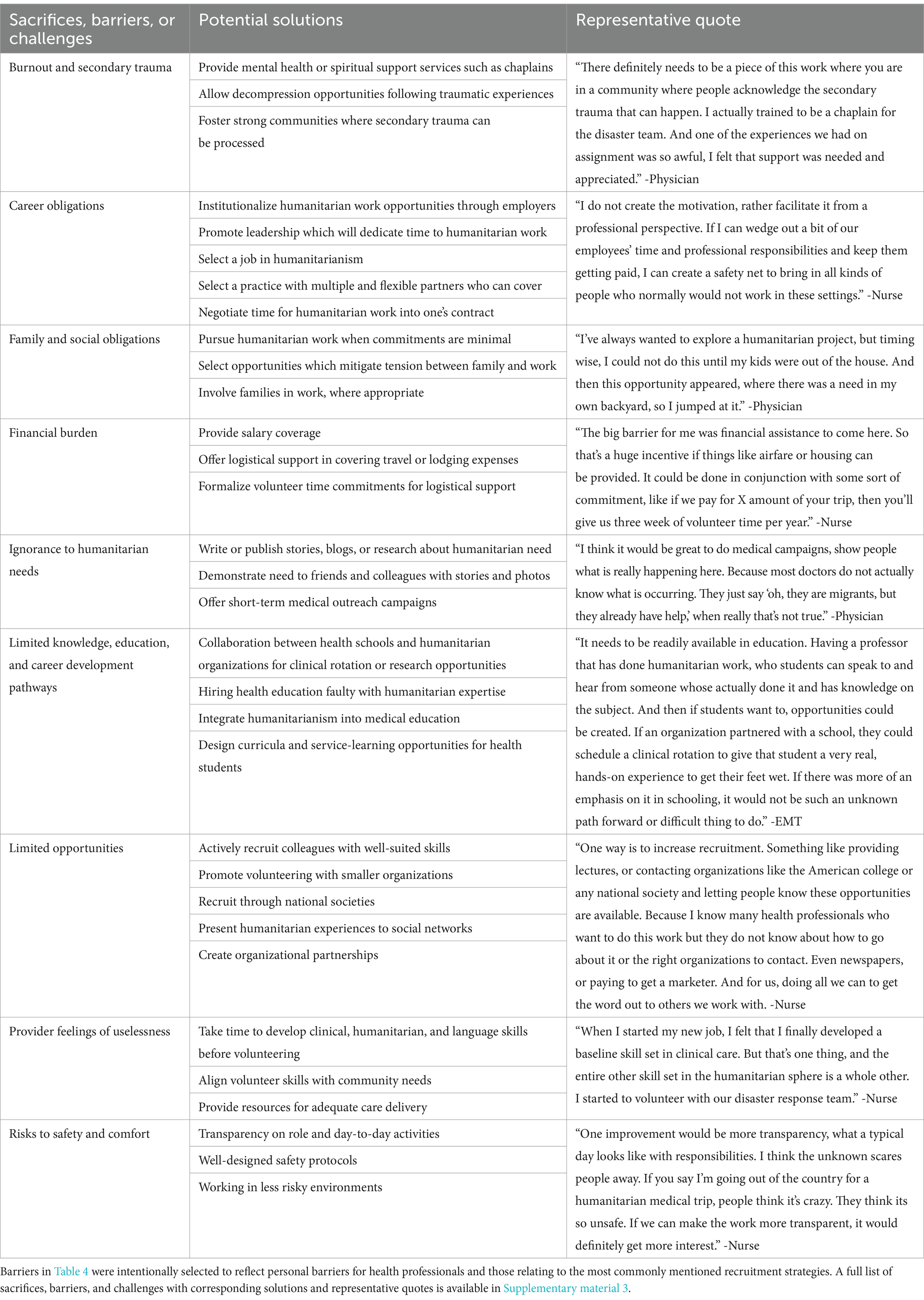

3.7 Recommended solutions

Participants recommended solutions to better motivate, support, and recruit health professionals to humanitarian health delivery for migrants. Solutions generally mirrored the sacrifices, barriers, and challenges identified by participants (Table 4; Supplementary material 3). First, participants highlighted the need for active recruitment and collaboration of health professionals and students (67%). Some believed that humanitarian electives should be a requirement to obtain a professional health degree. Many believed that pathways for career humanitarians should be better defined and that humanitarian clinical or research opportunities should be made accessible for health professionals working at private and academic medical centers (22%). Second, participants recommended fostering partnerships between aid organizations, US medical institutions, professional societies, and health education schools (52%). Such connections could provide mutual benefit by facilitating volunteering, demonstrating to younger trainees examples of long-term careers in humanitarianism, fostering research and fundraising collaborations, mitigating employer-related barriers for practicing clinicians, and providing mentors to trainees and young health professionals interested in this work. Participants emphasized the importance of actively encouraging colleagues to become involved, as this was an influential factor for many of them (59%). They recommended doing so with an interdisciplinary approach, where social workers, public health professionals, advocates, interpreters, and others outside of clinical care could contribute valuable skills to migrant care. Third, participants emphasized the importance of demonstrating the health needs of their migrant patients (67%). They believed that exposing this reality to their colleagues and trainees would motivate those who were previously unaware to become involved. Fourth, participants encouraged aid organizations to take steps to mitigate the uncertainties and nervousness of first-time volunteers by providing comprehensive information including travel logistics, role descriptions, and safety protocols prior to applying for a volunteer role (26%). Fifth, health professionals recommended improving knowledge and accessibility of humanitarian work by highlighting opportunities beyond premier, well-known organizations such as the United Nations and Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders), which can be restrictively competitive due to popularity (30%). Specifically, they suggested that smaller organizations engage in writing and publishing activities or provide examples of creative approaches from volunteers who successfully navigated commitments of work or home to participate (22%). Finally, they encouraged organizations to support humanitarian workers through mental health support services, logistical support including for housing and travel, and institutionalized mechanisms to identify and mitigate burnout (41%).

Table 4. Recommended solutions to handle challenges of humanitarian assistance among migrants in Reynosa and Matamoros, Mexico.

4 Discussion

In this qualitative study of health professionals at the US-Mexico border, our sample identified common positive and negative determinants for working with migrant populations, as well as recommendations to address health worker shortages in migrant humanitarian contexts. Positive factors included internal motivations, external facilitators, and personal and professional benefits including a desire to help vulnerable populations, career flexibility, improved clinical skills, and a sense of joy and fulfillment from their work. Negative measures reflected internal sacrifices and external barriers such as career and family commitments, safety risks, limited education and volunteer opportunities, and criticisms of humanitarianism in general. Considering these determinants, participants suggested several strategies to increase recruitment of health professionals caring for migrants in humanitarian settings. These recommendations, which aimed to enhance benefits and mitigate challenges, could provide feasible and attainable solutions for organizations, individuals, and health employers to address health workforce shortages in humanitarian settings.

Positive determinants reflected concepts of altruism including a desire to help and vocation for justice, positive past experiences of previous volunteering or colleagues’ recommendations, and personal identity through group affiliation, family values, or moral responsibility based on citizenship. External facilitators enabled the feasibility of humanitarian work including employer or social flexibility, geographic proximity and shorter commitments, mitigating safety risks, and financial support. Multiple benefits realized from this work impacted participants personally and professionally through improved clinical skills and knowledge, sociocultural and language learning, and network building, among others. These positive incentives have been shown to be common among health volunteers, including improved physical and emotional wellbeing and that there may be a reciprocally beneficial relationship between these factors (26). Negative determinants shared similar themes, including internal sacrifices of family, career, personal stability and safety, and external barriers which limited effective clinical work including language differences and limited education, career development, and volunteer opportunities. Though not explicitly referenced by our sample, many of these negative determinants can have negative long-term consequences including burnout, career stagnation, and a psychological toll from working in high-stress environments. Both positive and negative determinants to migrant work have been well documented in other humanitarian contexts. A systematic review among health professionals working with migrants in Europe demonstrated the importance of sociocultural competence, adequate training and funding, and collaboration among interdisciplinary actors, but that health workers frequently reported exhaustion and reliance on coping mechanisms for emotionally stressful work (20). For those working in refugee settings similar to our sample, key challenges included linguistic and cultural barriers, lack of training, and feelings of helplessness among providers (27).

These findings contribute to understanding how to better address health worker shortages in migrant and humanitarian contexts. Our sample recommended dozens of tangible and feasible interventions to better recruit, support, and retain qualified health professionals caring for migrants. Such recommendations included early educational interventions for health professional students including integration of humanitarian curricula, formalizing partnerships between established academic institutions and humanitarian organizations, and better defining and rewarding career pathways through mentor, research, and clinical rotation opportunities. While the number of humanitarian-specific training opportunities has been increasing, there remains global inequality in access to these programs due to financial and geographical constraints (28). Furthermore, such concepts are rarely integrated into health professional education in a way that is mandatory or accessible to interested students (29). These approaches may be effective, as early exposure to medical care among vulnerable populations, service-learning, and partnerships between institutions and volunteer organizations have all been shown to increase health worker interest and participation in medical work among vulnerable populations (30, 31). Examples of such programs could include sponsored clinical rotations in humanitarian settings, mentored research projects with contextual experience through data collection, and courses on adaptation to medical practice in humanitarian care delivery, some of which have already been successfully implemented at health education training programs in the US, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Thailand, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand (32). Other strategies from our sample focused on raising awareness to recruit current health workers including advertising through professional societies, running medical outreach trips to raise awareness for migrant health disparities, information dissemination through publication and presentation to colleagues, and for organizations to expand research efforts and volunteer pools to include interdisciplinary fields. Potentially most impactful, our sample recommended formalizing collaborations between health employers and humanitarian organizations to mitigate one of the greatest barriers of career obligations and create bidirectional benefit for each institution. While such approaches have been proposed for humanitarianism, few have been actualized in practice (33). Finally, material and emotional support could increase participation including assisting with travel and other financial logistics, defining roles to mitigate uncertainty, and attentiveness to the mental health needs of health professionals (20).

There were several novel aspects to this study. First, we interviewed health professionals at the US-Mexico border, which despite the large increases in migrant populations and health needs, remains an understudied area compared with other refugee contexts. Since most humanitarian contexts overlap with under-resourced or LMIC health systems, our findings could have greater impact for resource mobilization from the US given proximity to deployable resources and US-based charities. Compared with the experiences of health professionals in other humanitarian settings, our sample revealed many unique determinants that were specific to working at the US-Mexico border. These included a moral obligation from US citizens to counteract restrictive immigration policies implemented by their own country, geographic proximity, and accessibility of short-term commitments. These differences suggest the importance of context-specific determinant assessments in recruiting and retaining humanitarian health professionals. Second, we intentionally recruited participants across two ports of entry at the US-Mexico border and selected for a diverse sample of providers across multiple organizations, health professional roles, humanitarian experiences including long and short-term commitments, and varied countries of origin and primary language. This diversity revealed differences across participant groups, including that Matamoros workers were longer-term, Reynosa participants more often benefited from employer-humanitarian organization partnership, physicians more often emphasized employer flexibility as a key facilitator, and those living close to the border were less likely to report sacrifices. There were unique challenges between short and long-term workers, such as career or family obligations and instability in social lives, respectively. Interestingly, criticisms of humanitarian aid and most benefits and motivators did not differ between participants of varied experience level, age, or health professional role, as might be expected. Despite the variation in our sample, common responses from participants demonstrated the universality of many determinants to humanitarian work and that recommended solutions could hold promise for other humanitarian contexts. Third, three of the health professionals in our study were part of the asylum seeker population they served. When such efforts have been made in other settings, unintentional negative consequences may arise, such as the case with refugee health workers in Uganda who faced increased discrimination, costly credentialing processes, and unclear clinical scope (34). These barriers were not identified by our sample, suggesting the influence of contextual factors, such as the heterogeneous nature of the migrant population themselves, as well as GRM’s hiring and credentialing process as an effective approach to equitable inclusion of asylum seeker health professionals. Finally, our sample enumerated 12 criticisms of humanitarian aid which limit organizations from optimizing care delivery. While challenges with humanitarian assistance have been hypothesized previously, limited in-depth evidence has evaluated the nuance behind and consequences of these critiques for health professionals working in the field (35, 36). Our qualitative evidence provides multifaceted and diverse accounts of how these challenges can have direct impacts on health professionals and the populations they serve.

Other findings from our study were notable. First, it was surprising that participants listed limited volunteer opportunities as a major barrier to humanitarian work. In light of evidence showing quantifiable health worker shortages in such contexts, there is a notable discrepancy in willingness to volunteer and opportunities to do so. Exploring the etiology for this discrepancy and piloting quality improvement efforts aimed at increasing the capacity of humanitarian organizations to accept health workers or improve recruitment materials could be valuable. Second, participants infrequently mentioned fear of indiscriminate violence or political pressure, which are common among humanitarian workers in other settings (27). This difference could be attributed to the relative stability of the US-Mexico border compared with other refugee contexts and freedom of movement and expression for US or Mexican nationals. Our sample did not mention rigidity of the health system as a barrier, despite this being a frequent challenge for health providers in other refugee settings (27). Given that GRM and MSF worked in small, mobile health teams, these operations may have increased flexibility for staff. Opposingly, a lack of rigidity may contribute to unstandardized protocols, treatment guidelines, or resource availability. Humanitarian organizations could benefit from determining the appropriate amount of operational structure to facilitate quality care for patients, while granting sufficient autonomy to health workers. Finally, our participants mentioned operational challenges including bureaucratic inefficiencies and a lack of standardized protocols. A persistent challenge for many health systems, such issues could be addressed through systematic approaches to organization, care delivery, and outcomes reporting through frameworks such as implementation science (37). More specifically, implementing evidence-based approaches could mitigate these challenges, including standardized clinical practice guidelines derived from organizational resources and forming humanitarian clusters based on the World Health Organization model through which organizations can collaborate (38).

4.1 Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the qualitative nature of our methods limits generalizability to health workers outside of the US-Mexico border or even other ports of entry. Therefore, the challenges and determinants identified here may not fully represent those faced by health workers in all other global humanitarian settings. For example, the accessibility of volunteering, shorter-term commitments, and employer support as facilitators are likely unique to our sample and may not be available to those working in conflict zones or long-term development projects. We postulate that our findings may closely reflect those of other health workers working in border migrant settings but situated within more well-resourced environments. An additional limitation to generalizability was our smaller sample size with participants representing a limited number of humanitarian organizations. However, the in-depth explanations, varied roles, and extensive past humanitarian experiences from our sample suggest these results may be applicable in other settings, particularly when discussing determinants of border and migration humanitarianism. Second, our sample worked at the US-Mexico border for a limited amount of time among a select number of humanitarian organizations, which did not include all groups providing aid in Reynosa or Matamoros. This limitation could influence participant perspectives on operational challenges and intraorganizational dynamics. Our data collection periods were separated by approximately two and a half years, which could lead to different perspectives particularly in the US-Mexico border setting, where immigration policies are rapidly changing in nature and could have implications for migrant health. However, it was determined during analysis that major themes were shared between each location and that many of the providers who were interviewed in Reynosa had also worked in Matamoros over the preceding 3 years. Finally, our results only included health professionals. Though we included a diverse group of physicians, nurses, and logisticians among others, incorporating the perspectives of humanitarian organization administrators, government officials, or migrant patients themselves could produce more robust data.

5 Conclusion

Health professionals working with asylum seekers and refugees at the US-Mexico border were able to identify common positive and negative determinants to delivering health services to migrants in humanitarian settings, as well as recommendations to address health worker shortages. Determinants included incentivizing motivations, facilitators, and benefits, alongside disincentivizing sacrifices, barriers, and challenges. Recommendations reflected feasible and early intervention strategies for recruiting health professionals including integration of clinical and research opportunities into health professional education, collaboration between health institutions and humanitarian organizations to reduce employment-related barriers, and increasing transparency and professional support services to clarify the process for working with humanitarian organizations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (HUM00186322). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because oral informed consent was obtained in accordance with recommendations of the IRB to further guarantee anonymity of participants.

Author contributions

CR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SR: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. EA: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. IB: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SB: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. BT: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JB-A: Resources, Writing – review & editing. JI: Data curation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. PV: Data curation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. LO: Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. SD: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AM: Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. FS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by an Individual Global Grant from the University of Michigan. No external funder had influence over the study design, execution, or publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of Global Response Medicine for their support in project facilitation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1447054/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Makuku, R, and Mosadeghrad, AM. Health workforce retention in low-income settings: an application of the root stem model. J Public Health Policy. (2022) 43:445–55. doi: 10.1057/s41271-022-00361-x

2. Campbell, J, Dussault, G, Buchan, J, Pozo-Martin, F, Arias, M, Leone, C, et al. A Universal Healthcare: No Health Without a Workforce. World Health Organization; (2013). Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/health-workforce/ghwn/ghwa/ghwa_auniversaltruthreport.pdf?sfvrsn=966aa7ab_7&download=true (Accessed on 2024 May 29).

3. Jinah, N, Abdullah Sharin, I, Bakit, P, Adnan, IK, and Lee, KY. Overview of retention strategies for medical doctors in low-and middle-income countries and their effectiveness: protocol for a scoping review. JMIR Res Protoc. (2024) 13:e52938. doi: 10.2196/52938

4. Refugee Statistics . USA for UNHCR. (2024) Available from: https://www.unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/statistics/#:~:text=Refugee%20Facts&text=More%20than%20114%20million%20individuals (Accessed May 29, 2024).

5. Southwest Land Border Encounters . U.S. Customs and Border Protection. (2024). Available from: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-land-border-encounters (Accessed May 29, 2024).

6. Reynolds, CW, Ramanathan, V, Das, PJ, Schmitzberger, FF, and Heisler, M. Public health challenges and barriers to health care access for asylum seekers at the U.S.-Mexico border in Matamoros, Mexico. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2022) 33:1519–42. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2022.0127

7. Yakubu, K, Abimbola, S, Durbach, A, Balane, C, Peiris, D, and Joshi, R. Utility of the right to health for addressing skilled health worker shortages in low-and middle-income countries. Int J Health Policy Manag. (2022) 11:2404–14. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2022.6168

8. Dohlman, L, DiMeglio, M, Hajj, J, and Laudanski, K. Global brain drain: how can the Maslow theory of motivation improve our understanding of physician migration? Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:1182. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071182

9. Gupta, J, Patwa, MC, Khuu, A, and Creanga, AA. Approaches to motivate physicians and nurses in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic literature review. Hum Resour Health. (2021) 19, 1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00522-7

10. Dugani, S, Afari, H, Hirschhorn, LR, Ratcliffe, H, Veillard, J, Martin, G, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with burnout among frontline primary health care providers in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Gates Open Res. (2018) 2:4. doi: 10.12688/gatesopenres.12779.1

11. Harrell, M, Selvaraj, SA, and Edgar, M. DANGER! Crisis health Workers at Risk. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:5270. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155270

12. Rubenstein, L, and Wille, C. Critical Condition: Violence Against Health Care In Conflict. Adams E, Alnahhas H, Amon J, Bales C, Baidoun A, Barhoush Y, editors. (2023) Available from: https://insecurityinsight.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/2023-SHCC-Critical-Conditions.pdf (Accessed on 2024 May 29).

13. Das, PJ, Sagal, KM, Blanton, KL, Naidu, AS, Pavlis, W, Goyert, J, et al. U.S. medical student knowledge and interest in asylum seeker medical care. Educ primary care. (2022) 33:364–8. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2022.2137856

14. Gomez, R, Newell, BC, and Vannini, S. Empathic humanitarianism: understanding the motivations behind humanitarian work with migrants at the US–Mexico border. J Migr Hum Secur. (2020) 8:1–13. doi: 10.1177/2331502419900764

15. Muthuri, RNDK, Senkubuge, F, and Hongoro, C. Determinants of motivation among healthcare Workers in the East African Community between 2009–2019: a systematic review. Health. (2020) 8:164. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8020164

16. Matthews, N, and Walker, R. Training tomorrow's doctors: the impact of a student selected component in Global Health during medical school. MedEdPublish. (2016) 10:150. doi: 10.15694/mep.2021.000150.1

17. Elma, A, Nasser, M, Yang, L, Chang, I, Bakker, D, and Grierson, L. Medical education interventions influencing physician distribution into underserved communities: a scoping review. Hum Resour Health. (2022) 20:31. doi: 10.1186/s12960-022-00726-z

18. Wu, A, Choi, E, Diderich, M, Shamim, A, Rahhal, Z, Mitchell, M, et al. Internationalization of medical education - motivations and formats of current practices. Med Sci Educ. (2022) 32:733–45. doi: 10.1007/s40670-022-01553-6

19. Neubauer, BE, Witkop, CT, and Varpio, L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Educ. (2019) 8:90–7. doi: 10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2

20. Peñuela-O’Brien, E, Wan, MW, Edge, D, and Berry, K. Health professionals’ experiences of and attitudes towards mental healthcare for migrants and refugees in Europe: a qualitative systematic review. Transcult Psychiatry. (2022) 60:176–98. doi: 10.1177/13634615211067360

21. Bochenek, MG, Binford, W, Matlow, R, and Wang, E. “Like I’m Drowning”. Human Rights Watch. (2021). Available from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/01/06/im-drowning/children-and-families-sent-harm-us-remain-mexico-program (Accessed May 29, 2024).

22. Leiner, A, Sammon, M, and Perry, H. Facing COVID-19 and refugee camps on the U.S. border. J Emerg Med. (2020) 59:143–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.04.041

23. MacQueen, KM, McLellan, E, Kay, K, and Milstein, B. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. CAM Journal. (1998) 10:31–6. doi: 10.1177/1525822X980100020301

24. McHugh, ML . Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). (2012) 22:276–82. doi: 10.11613/BM.2012.031

25. O'Brien, BC, Harris, IB, Beckman, TJ, Reed, DA, and Cook, DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. (2014) 89:1245–51. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

26. Nichol, B, Wilson, R, Rodrigues, A, and Haighton, C. Exploring the effects of volunteering on the social, mental, and physical health and well-being of volunteers: an umbrella review. Voluntas. (2023) 35:97–128. doi: 10.1007/s11266-023-00573-z

27. Kavukcu, N, and Altıntaş, KH. The challenges of the health care providers in refugee settings: a systematic review. Prehosp Disaster Med. (2019) 34:188–96. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X19000190

28. Bahattab, AAS, Linty, M, Trentin, M, Truppa, C, Hubloue, I, Della Corte, F, et al. Availability and characteristics of humanitarian health education and training programs: a web-based review. Prehospital Disaster Med. (2021) 37:132–8. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X21001333

29. Shah, MH, Roy, S, and Flari, E. The critical need for disaster medicine in modern medical education. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2024) 18:e80. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2024.56

30. Demirören, M, and Atılgan, B. Impacts of service learning-based social responsibility training on medical students. Adv Physiol Educ. (2023) 47:166–74. doi: 10.1152/advan.00049.2022

31. Arebalos, MR, Botor, FL, Simanton, E, and Young, J. Required longitudinal service-learning and its effects on medical students’ attitudes toward the underserved. Medical Sci Educator. (2021) 31:1639–43. doi: 10.1007/s40670-021-01350-7

32. Johnson, GE, Wright, FC, and Foster, K. The impact of rural outreach programs on medical students’ future rural intentions and working locations: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. (2018) 18:196. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1287-y

33. Kohrt, BA, Mistry, AS, Anand, N, Beecroft, B, and Nuwayhid, I. Health research in humanitarian crises: an urgent global imperative. BMJ Glob Health. (2019) 4:e001870. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001870

34. Palmer, J, Sokiri, S, Char, JNB, Vivian, A, Ferris, D, Venner, G, et al. From humanitarian crisis to employment crisis: the lives and livelihoods of south Sudanese refugee health workers in Uganda. Int J Health Plann Manag. (2024) 39:671–88. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3777

35. Colombo, S, and Pavignani, E. Recurrent failings of medical humanitarianism: intractable, ignored, or just exaggerated? Lancet. (2017) 390:2314–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31277-1

36. Spiegel, PB . The humanitarian system is not just broke, but broken: recommendations for future humanitarian action. Lancet. (2017) S0140-6736:31278–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31278-3

37. Reynolds, CW, Hsu, PJ, and Telem, D. Implementation science in humanitarian assistance: applying a novel approach for humanitarian care optimization. Implement Sci. (2024) 19:38. doi: 10.1186/s13012-024-01367-7

Keywords: humanitarian assistance, migrant health, refugee, US–Mexico border, global health, immigration, health worker shortages

Citation: Reynolds CW, Ryan SF, Acharya E, Berberoglu I, Bishop S, Tucker B, Barreto-Arboleda JD, Ibarra JAF, Vera P, Orozco LJF, Draugelis S, Mohareb AM and Schmitzberger F (2024) Determinants for the humanitarian workforce in migrant health at the US-Mexico border: optimizing learning from health professionals in Matamoros and Reynosa, Mexico. Front. Public Health. 12:1447054. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1447054

Edited by:

Bruce Struminger, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Michelle Niescierenko, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, United StatesLorenzo Franceschetti, University of Milan, Italy

Copyright © 2024 Reynolds, Ryan, Acharya, Berberoglu, Bishop, Tucker, Barreto-Arboleda, Ibarra, Vera, Orozco, Draugelis, Mohareb and Schmitzberger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christopher W. Reynolds, Y2h3cmVAbWVkLnVtaWNoLmVkdQ==

Christopher W. Reynolds

Christopher W. Reynolds Savannah F. Ryan2

Savannah F. Ryan2 Ipek Berberoglu

Ipek Berberoglu Samuel Bishop

Samuel Bishop Juan Daniel Barreto-Arboleda

Juan Daniel Barreto-Arboleda Jorge Armando Flores Ibarra

Jorge Armando Flores Ibarra Sarah Draugelis

Sarah Draugelis Florian Schmitzberger

Florian Schmitzberger