- 1University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, United States

- 2Division of Gynecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, United States

- 3Center of Innovation and Value at Parkland, Parkland Health, Dallas, TX, United States

- 4Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, United States

- 5Department of Epidemiology, Human Genetics, and Environmental Sciences, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, United States

- 6Institute for Implementation Science, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, United States

- 7Division of General Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

Introduction: As health systems strive to screen for and address social determinants of health (SDOH), the role of access to childcare and barriers to healthcare posed by childcare needs remains underexplored. A gap exists in synthesizing existing evidence on the role of access to childcare as a SDOH.

Methods: This scoping review aimed to examine and analyze existing literature on the role of childcare needs as a social determinant of access to healthcare. We conducted a structured literature search across PubMed, Scopus, health policy fora, and professional healthcare societies to inclusively aggregate studies across interdisciplinary sources published between January 2000 and June 2023. Two independent reviewers reviewed results to determine inclusions and exclusions. Studies were coded into salient themes utilizing an iterative inductive approach.

Results: Among 535 search results, 526 met criteria for eligibility screening. Among 526 eligible studies, 91 studies met inclusion criteria for analysis. Five key themes were identified through data analysis: (1) barriers posed by childcare needs to healthcare appointments, (2) the opportunity for alternative care delivery models to overcome childcare barriers, (3) the effect of childcare needs on participation in medical research, (4) the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on childcare needs, and (5) the disproportionate burden of childcare experienced by vulnerable populations.

Discussion: Childcare needs remain underexplored in existing research. Current evidence demonstrates the relevance of childcare needs as a barrier to healthcare access, however dedicated studies are lacking. Future research is needed to understand mechanisms of childcare barriers in access to healthcare and explore potential interventions.

1 Introduction

Social determinants of health (SDOH) like housing, food security, transportation, and insurance, are the non-medical conditions that drive health outcomes (1). Access to healthcare, defined as all factors that facilitate or impede the use of healthcare services (2), cannot be viewed simply through the lens of availability of services, but also the means to obtain and utilize services (3). Recognizing that SDOH inequitably impact marginalized and minoritized communities, we must understand and address social and structural factors affecting engagement in healthcare to address health disparities (4, 5).

Recent analyses of barriers to care engagement in myriad clinical contexts demonstrate the importance of health-related social needs (HRSN) that affect presentation to care and adherence (6–9). Transportation (10, 11) and work leave (12, 13) have been established as HRSNs that are associated with missed appointments, deferral of care, and medication non-adherence (14, 15). Similarly, childcare needs are increasingly recognized as a driver of missed and deferred care, as notably highlighted by the 2017 Kaiser Family Foundation Women’s Health Survey (16). Childcare has emerged as a key policy issue for the current U.S. presidential administration in an effort to support caregiving needs among families (17). Childcare needs require additional scrutiny, given that low income and minoritized populations disproportionately struggle with access to childcare. Furthermore, childcare needs are a key step in advancing gender equity (18–22). Given increasing attention to lack of diversity in medical research (23) and need for increased investment in women’s health research (22, 24), access to childcare warrants further study as a SDOH given its disproportionate relevance to women.

While childcare has been examined in the context of pediatric outcomes like early childhood development and asthma (25, 26), the impact of childcare needs on the health of parents and caregivers requires additional investigation. Prior work in the policy literature has established the relevance of childcare in parental workforce engagement (18, 27), but the impact of childcare on parent and caregiver healthcare engagement and health outcomes remains less clear. This scoping review aims to identify and summarize current knowledge on unmet childcare needs as a barrier to healthcare access for caregivers as well as to identify gaps in researching and addressing this SDOH.

2 Methods

2.1 Research question

The literature search was guided by the following research questions: What does the existing literature say about childcare needs as a barrier to healthcare access for caregivers of children? What are the gaps in understanding and addressing childcare needs as a social determinant of health for caregivers?

2.2 Search strategy

A literature search was conducted between June 2023 and August 2023. The search was limited to full journal articles published in the English language between January 1, 2000 and June 1, 2023. This time period was selected to encompass literature published since the Centers for Disease Control released Healthy People 2010 (28), which included the stated objective of eliminating health disparities and included access to healthcare for the first time as a leading health indicator. The search strategy included the following terms: social determinant of health, healthcare access, childcare, barrier, and disparity. The Boolean term “AND” was employed to specify terms essential to the potential literature review results (e.g., healthcare AND access AND childcare), and the Boolean term “OR” was used to maximize results for terms that may be used synonymously (e.g., healthcare OR “health care,” childcare OR “child care,” barrier OR disparity OR “social determinant of health”). The search query used for PubMed was, “(((((barrier) OR (disparity)) OR (“social determinant of health”)) AND (((healthcare) OR (“health care”)) AND (access))) AND ((childcare) OR (“child care”))) NOT (Review[Publication Type]),” and the search query used for Scopus was, “(“social determinant of health”) AND (access) AND (healthcare OR “health care”) AND (childcare OR “child care”) AND (LIMIT-TO (SRCTYPE, “j”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “SOCI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “PSYC”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “NURS”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “MULT”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “HEAL”) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, “MEDI”)) AND (EXCLUDE (DOCTYPE, “re”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)).” These search queries were tailored further for individual databases based on database capability, as some healthcare societies and health policy sites did not recognize advanced search operators or heeded zero results with long search queries. Customizing search queries by database permitted an adequate number of results per site searched.

2.3 Data sources

The primary search was conducted using PubMed to encompass the medical literature related to the study purpose. A second search was conducted with Scopus to expand the search across the following subjects: social sciences, psychology, nursing, multidisciplinary, health professions. Lastly, searches were conducted across professional healthcare societies and health policy fora to explore relevant medical research, position papers, and health policy briefs that may not have been included in the PubMed results. These websites included JAMA Health Forum (to include publications prior to PubMed indexing), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the Society of General Internal Medicine, the Kaiser Family Foundation, the Commonwealth Foundation, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

2.4 Data extraction

Two independent reviewers downloaded search results from PubMed and Scopus into a spreadsheet. Results from other websites were manually transferred to a spreadsheet.

2.5 Data screening

The search yielded 535 results, which were subsequently screened for duplicates, publication date, eligible source types, and presence of discussing childcare in full body-text (Figure 1). Six duplicate results were excluded from review. Three results were excluded as ineligible media, including 1 audio book and 2 reference sheets. Thirteen results were excluded after screening revealed that “childcare” was mentioned in relation to “maternal and child care” within institutional titles, or academic affiliation (e.g., a manuscript published by an author group from the National Maternal and Child Health Center in Phnom Penh, a large maternal and child health system, however article content was not about childcare) (29). Four results were excluded because childcare was solely mentioned in the abstract, not in the manuscript text itself. The 21 results that failed to mention childcare in their entirety came from databases that did not comply with Boolean expressions and were excluded during data screening. After this initial data screening, 488 results remained eligible for inclusion.

2.6 Data analysis

Two independent reviewers (MM and PT) reviewed the 488 eligible full-text studies for exclusion criteria. A third reviewer (AG) was consulted if the first two reviewers were not in agreement in their decisions for inclusion or exclusion. Studies were analyzed for eligibility based on population, setting, measures, and article type.

Studies were excluded based on population (n = 239) if the study population was not comprised of caregivers of children. For example, studies examining the role of childcare on health outcomes among pediatric subjects (children as recipients of childcare, n = 188) were excluded. Several studies explored the economic and/or policy impacts of childcare needs, namely impact of childcare on workforce engagement and cost of living; these studies were excluded as primary outcomes related to childcare were not healthcare-related (n = 100). Studies that examined the role of childcare on health outcomes outside of access to healthcare, such as the impact of childcare burdens on mental health or time for self-care outside of healthcare settings, were excluded to focus the analysis on the role of childcare as a logistical barrier to healthcare access and engagement (n = 35). Review papers were excluded (n = 22). One article was inaccessible to the reviewers.

After the eligibility review, 91 studies met criteria for analysis. Analysis followed best practices delineated by a scoping review methodology consensus group (30). Included studies underwent data extraction for the following characteristics: author, journal, year of publication, study country, clinical setting, study design, study population size, age range of study population, percentage of female participants, age range of children requiring childcare, and other SDOH or HRSN explored alongside childcare needs. A standardized Excel data charting form was utilized for data extraction of included studies. Basic qualitative content analysis utilizing an inductive approach was conducted to map salient themes from included studies. Two authors (MM and PT) conducted in-depth review of included studies to map to emerging themes. Analysis was iteratively reviewed among MM, PT, and AG to code themes and refine mapping. Two themes, theme #1 and theme #2, were defined a priori by the study team based on existing knowledge of the literature. Theme #3 was defined among studies initially categorized under theme #1, and theme #4 was defined among studies initially categorized under theme #3. Theme #5 was defined as a cross-cutting theme that emerged across the first four themes, as such studies categorized under theme #5 were double-coded in addition to original mapping along themes #1–4.

3 Results

Characteristics of inclusion studies are listed in Table 1. Publications identifying childcare needs as a barrier to healthcare were noted to increase over time, as shown in Figure 2, with a lower volume of publications in 2023 due to the time frame of the literature search.

Inclusion studies were primarily published in the United States, but several more countries were represented, including Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia, among others. Caregiver ages typically ranged from about 20–50 years, as listed in Table 1, and most study populations were comprised of majority female participants. Inclusion studies represented a wide array of clinical contexts, including primary care and specialty care, outpatient and hospital medicine, research settings, and community outreach. Studies included many data sources, encompassing focus groups (n = 22), key informant interviews (n = 42), surveys (n = 43), chart reviews (n = 7), resource website or census data (n = 2), observation of healthcare delivery (including electronic medical record dashboard, n = 4), and conceptual framework (n = 2). Study design was similarly heterogeneous. More than half (n = 50) included some component of qualitative analysis. Among 48 studies that included quantitative analysis, 50% (n = 24) were descriptive analyses of survey data and 11 utilized other observational designs. Only 3 inclusion studies were randomized controlled trials, and notably these three studies studied childcare needs alongside trial engagement, not as a study exposure or outcome.

3.1 Theme #1: Childcare needs are a barrier to attending healthcare appointments

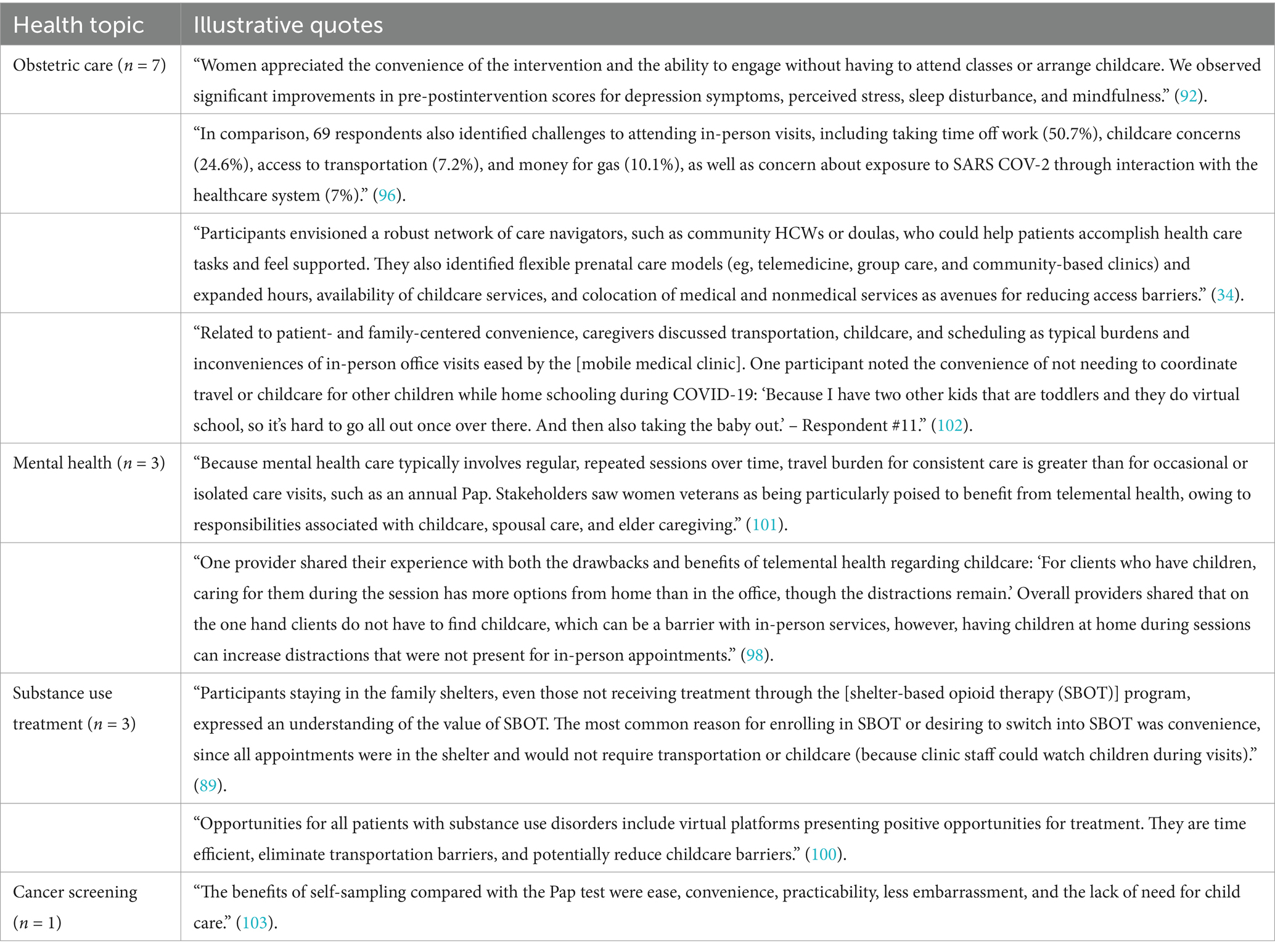

The majority of studies included (n = 71) examined childcare as a logistical barrier to attending health appointments among caregivers (Table 2). Childcare needs were identified across a wide distribution of health topics and clinical settings, including obstetric care (n = 17), access to care (n = 16), cancer screening (n = 7) and cancer treatment (n = 6), diabetes (n = 5), mental health (n = 5), family planning (n = 2), HIV care (n = 2), and more, as described in Table 2.

Table 2. Illustrative quotes from Theme #1: childcare needs are a barrier to attending healthcare appointments.

Across these studies, 52 specifically examined childcare barriers among women. Specific clinical contexts included obstetric care (n = 17) settings including access to (31–34) and experiences with prenatal care (35, 36), perinatal mental health (37–39), perinatal healthy weight services (40), management of gestational diabetes (41, 42), access to vaccinations during pregnancy (43), postpartum cardiovascular risk follow up (44), adherence to HIV care (45), and the prevention of preterm births (46). One study identified lack of childcare as a contributor to decreased rates of postpartum hospital readmissions in homeless women (47). Other clinical contexts where childcare needs posed a barrier to women’s healthcare access included prevention of diabetes after pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes (48, 49), access to HIV/AIDS care (50), access to sexual and reproductive healthcare for women enrolled in opioid use disorder treatment programs (51), access to smoking cessation programs (52), and access to abortion services (53). Childcare needs were also identified as a barrier to accessing breast and cervical cancer screening and treatment (6, 54–60).

A few studies also reported childcare as a logistical barrier to healthcare needs for the general caregiver population, not just for women. This barrier was identified in access to substance use treatment (n = 8), mental healthcare services (n = 5), dermatology visits (n = 1), elective surgeries (n = 1), oral care (n = 1) physical therapy (n = 1), and emergency department utilization (n = 1).

In theme #1, studies either considered unmet childcare needs as a discrete health-related social need (n = 37, 52.1%) or grouped childcare alongside other social needs (n = 34, 47.9%) in analysis and discussion. The 34 studies that examined childcare alongside other social needs often evaluated the affordability and accessibility of arranging childcare alongside transportation, income level, and language barriers. Among the 37 studies that discretely evaluated childcare as an individual barrier, 35 (94.6%) concluded that unmet childcare needs delayed care. Common reasons for missing or deferred appointments because of unmet childcare needs included limited affordability of childcare support (6, 10, 31–34, 36–40, 43–45, 48–52, 55–59, 61–89), distractions from children during care (42, 60, 84, 90–92), and limited flexibility of appointment times (52, 93–96). The remaining two studies did not find a significant association between childcare and delayed care (35) or noted uncertainty over childcare as a barrier to healthcare access (47).

Compared to studies that grouped childcare with other barriers, studies that examined childcare needs as an individual barrier to healthcare access were more likely to provide direct recommendations for interventions for childcare needs, including on-site childcare facilities at the point of healthcare access (31–33, 39, 51, 52, 55, 66, 67, 70, 72, 81, 83, 90, 92), subsidizing childcare (76), or dedicated case management for childcare services (50, 54). Four studies further examined how provision of childcare increased access to or engagement with healthcare services. One study found that patients receiving free onsite childcare were more likely to complete blood work for gestational diabetes (41); another demonstrated that a health center with onsite childcare facilitated medication adherence for women living with AIDS (50). Additionally, one study found that having social support for childcare permitted regular cervical cancer screening (54) and another identified free childcare as a potential intervention to increase access to risk reduction services for repeating a preterm birth (46).

3.2 Theme #2: Alternative care delivery models may alleviate barriers posed by childcare needs

Thirteen studies discussed the role of alternative healthcare delivery methods in contrast to traditional in-person visits onsite at healthcare facilities to circumvent logistical barriers to appointments, including childcare needs (Table 3). The most common alternative care delivery method reported was virtual care through telemedicine (n = 9). All but one of the studies focused on pregnant women seeking obstetric (n = 5) (35, 67, 97–99) or psychiatric care (n = 3) (93, 100, 101). While most studies (n = 8) concluded that virtual care allowed for greater patient engagement in women’s healthcare services by bypassing childcare barriers, one study discussed the mixed effectiveness of virtual care in overcoming childcare needs since children could distract from virtual care engagement even within the home during virtual visits (98). Though many of the studies included pregnant women who were predominantly white and from higher socioeconomic backgrounds (97–99), some studies further explored the benefits of virtual care in increasing access to mental health care for marginalized populations, including refugees (100), women receiving care in the Veteran Affairs Health System (102), and pregnant women with substance use disorders (101).

Table 3. Illustrative Quotes from Theme #2: alternative care delivery models may alleviate barriers posed by childcare needs.

One study deployed a mobile medical clinic as a response to health access barriers in maternal–infant care during COVID-19 (103). By addressing proximity to care, the mobile clinic was shown to reduce childcare barriers for women receiving care, particularly among Black and Latina mothers. Another study illustrated how childcare needs were circumvented with self-screening for cervical cancer in a population of Hispanic women (104). The use of outpatient methadone maintenance therapy in lieu of traditional residential drug treatment programs was identified as one possibility to ease the burden of childcare on access to opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment (77). Furthermore, in an attempt to address the disproportionate burden of OUD among people experiencing homelessness, a study identified shelter-based opioid treatment as an alternative treatment modality that that eased the burden of childcare needs (90).

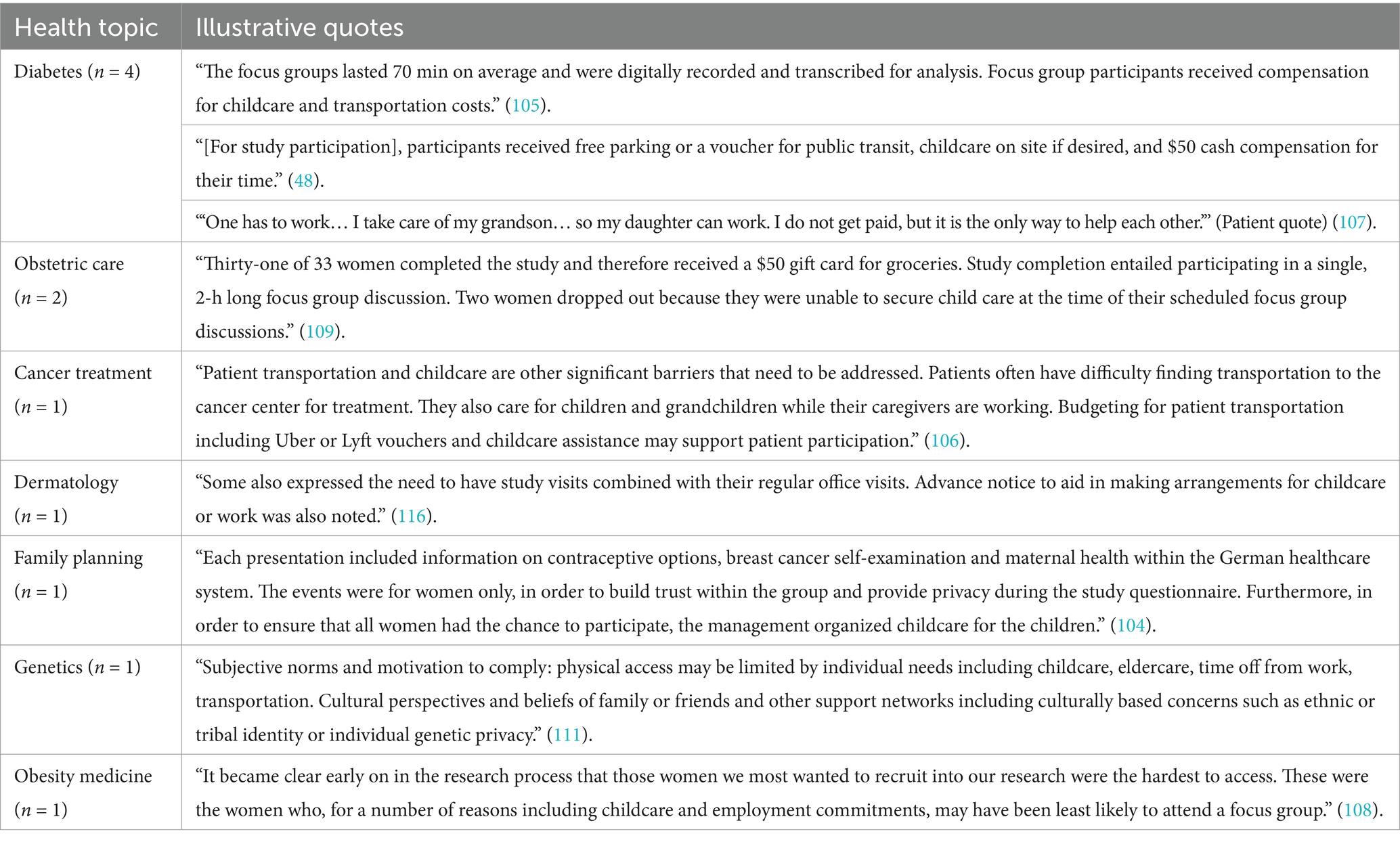

3.3 Theme #3: Childcare needs are a barrier to participating in medical research

Childcare as a barrier to healthcare access was noted to extend beyond clinical appointments to the ability to engage in medical research. Of the studies that investigated the effect of childcare in caregivers’ research participation (n = 11), 7 cited childcare as a barrier to research participation, and 4 directly addressed this barrier by providing childcare to facilitate enrollment of caregivers in research studies (Table 4). All four studies that used childcare resources as an incentive for research participation solely recruited women as the target population for research studies investigating obstetric outcomes and women’s health. Three studies provided on-site childcare to increase study participation, including a trial identifying risk factors for repeat preterm birth (46), interviews exploring barriers to diabetes screening among women with gestational diabetes (49), and family planning group visits among female refugees in Germany (105). One study provided compensation for childcare to supplement participation in focus groups discussing type 2 diabetes prevention for women with history of gestational diabetes (106).

Table 4. Illustrative quotes from Theme #3: childcare needs are a barrier to participating in medical research.

Studies that identified childcare as a barrier to research participation often sought to recruit racially diverse or socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals (n = 4). Two studies targeted recruitment of Latino participants (107, 108), one study recruited female refugees residing in Berlin (105), and one study aiming to recruit women from socioeconomically disadvantages areas concluded that, “…those women we most wanted to recruit into our research were the hardest to access” (109). Additionally, two studies specifically noted women as a vulnerable population for unmet childcare needs limiting research participation (110, 111). While most of studies examining childcare barriers to research were one-time focus group or interviews for participants (n = 5), one study assessed research participation barriers over a five-year period and concluded that barriers like childcare can longitudinally affect research engagement (111). A framework for promoting equitable inclusion in genetics and genomics research identified childcare as a need to be considered in expanding diverse research participation (112).

3.4 Theme #4: Childcare needs were exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic

Nine studies examined how the COVID-19 pandemic and associated childcare crisis (113) altered the way that caregivers access healthcare (Table 5). The effect of unmet childcare needs on healthcare access was made even more pronounced as closed schools and daycare centers forced parents and caregivers to isolate with their children and assume increased responsibilities for caregiving previously provided in institutional settings. Aside from immediately impacting changes in childcare, one inclusion paper explores the Public Health 3.0 framework, which consists of a collaborative effort across local public health institutions to identify and monitor health disparities and identifies childcare as a critical indicator for pandemic preparedness and response that requires further evaluation to determine the pandemic’s social impact on public health (114).

Table 5. Illustrative quotes from Theme #4: childcare needs were exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Studies reported a significant association between childcare barriers and delayed healthcare for low-income parents (73, 115). New public health restrictions deepened unmet childcare needs as women, particularly Latinx immigrant women (89), struggled with healthcare access when they were unable to bring children to appointments or secure childcare. Lastly, the impact of the pandemic on unmet childcare needs persisted long after the return to full health systems operations; one study noted that when non-essential surgeries resumed post-pandemic, childcare continued to serve as a barrier to scheduling surgeries, and that nonwhite participants were five times as likely to have childcare concerns (87).

The exacerbation of childcare needs during COVID-19 also galvanized innovations in alternative methods of healthcare delivery, as explored in theme #2 above. The mobile medical clinic introduced in theme #2 was one response to the heightened childcare needs during COVID-19 that successfully helped to circumvent this burden by bringing care closer to patients in their communities (103). Virtual healthcare also grew exponentially during the COVID-19 pandemic, and pregnant and postpartum patients with substance use disorders were reported to benefit from transitioning to telehealth by reducing in-person barriers, including childcare (101). Conversely, telehealth was noted to be potentially insufficient to close the gap in existing healthcare disparities due to residual structural inequities like the digital divide (116); one study that recognized childcare as a reason for delaying care also noted low rates of telehealth use among low-income, Black, and Latinx patients (115).

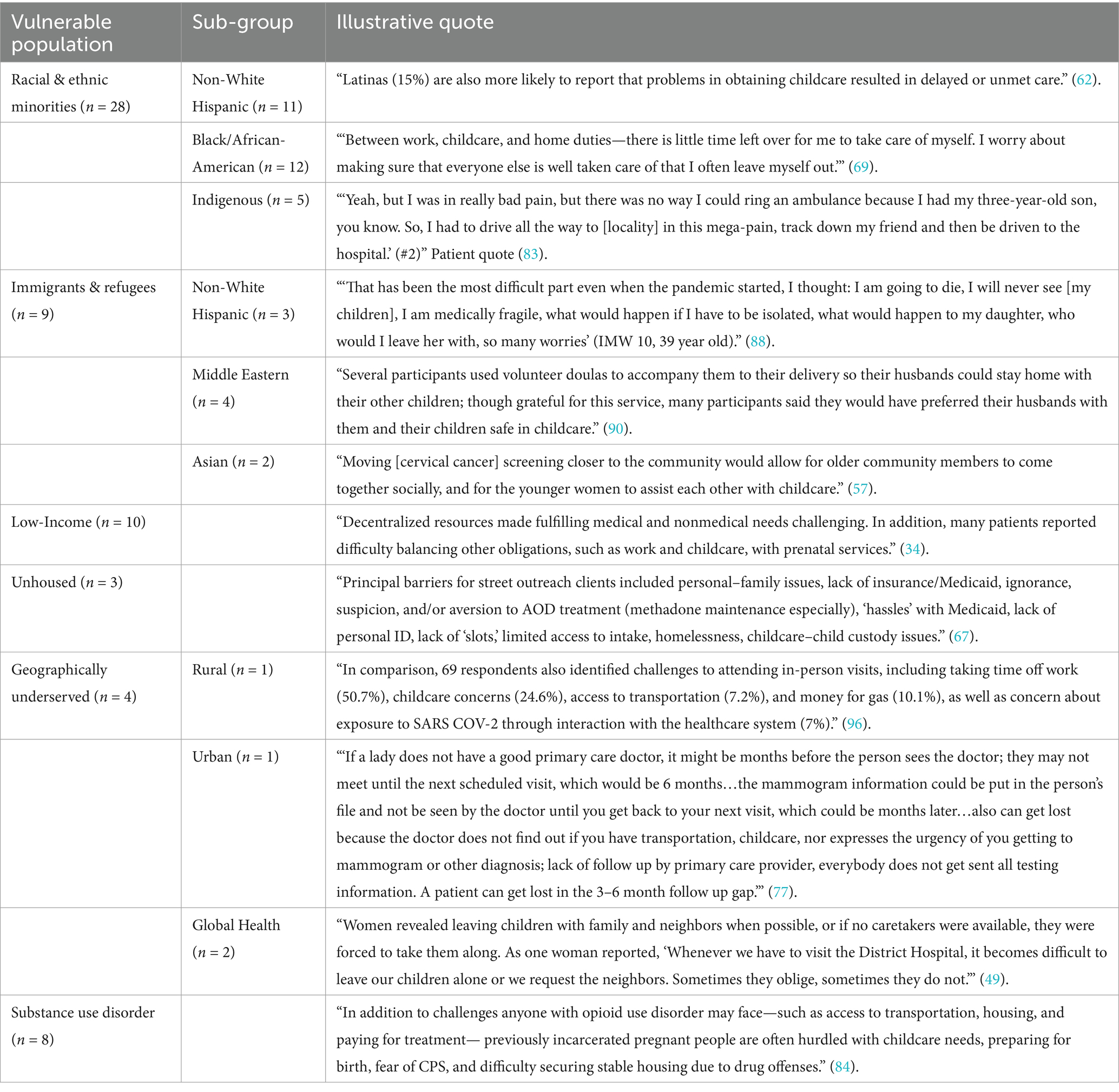

3.5 Theme #5: Childcare needs disproportionately impact marginalized populations

Vulnerable populations grappling with unmet childcare needs across all themes included women (n = 66), racial/ethnic minorities (n = 28), and low-income families and individuals (n = 10). Studies also highlighted the relevance of childcare needs among immigrants and refugees, residents of geographically isolated areas, and people with substance use disorders (Table 6). Twenty-eight total studies explored the impact of childcare on non-white Hispanic patients (n = 11), Black/African-American patients (n = 12), and indigenous patients (n = 5), among which 12 studies applied an intersectional approach to understanding childcare among women of color.

Table 6. Illustrative quotes from Theme #5: childcare needs disproportionately impact marginalized populations.

While reliance on social networks for childcare support was sometimes observed among minoritized communities (54), lack of social support was more often reported by caregivers as a main reason for facing unmet childcare needs (6, 31, 55, 61). Without social support for childcare, many caregivers also identified policies prohibiting bringing children to healthcare settings, further delaying their care (50, 92). Single mothers in New Zealand reported unmet childcare needs delayed emergency care, made appointments more stressful, made postpartum recovery difficult, and precluded one mother from accessing substance use treatment (84).

Additionally, literature identified that immigrants (n = 5) and refugees (n = 4) are likely to struggle with balancing healthcare access and childcare needs. Childcare needs identified in immigrant populations span across the globe, including immigrant Hispanic women in the United States (61, 75, 89), first-generation Somali women residing in London (55), and newly arrived immigrants from around the globe in Canada (58, 95). Refugee populations impacted by childcare needs included asylum seekers in the United States (100), refugees and asylum seekers in a government-funded housing center in Germany (105), and Syrian refugee women resettling in Canada (79, 91).

Among the 10 studies focused on low-income populations, paying for childcare or attending appointments was less prioritized over other competing financial demands like missing work (61, 70, 76). This experience of navigating changing constraints was also seen among postpartum mothers receiving care under Medicaid who lost insurance coverage shortly after birth (81). Other vulnerable populations identified in the literature included unhoused populations (n = 3), which were noted to have an added stressor related to custody of children and fear of being reported to Child and Family Services if children were brought to healthcare settings (47, 68). Two other studies examined childcare needs among unhoused caregivers seeking treatment for OUD (90) and clients of street outreach substance use disorder treatment programs (68).

Four studies focused on geographically vulnerable populations, including individuals living in rural areas (98, 110, 117) and urban medically underserved communities (78). Similarly, geographic isolation was explored in global health settings, such as among patients in Honduras (94). Alongside cost of care (94), inefficient medical resources (78), lack of social support (50), and a lack of access to technology (98), unmet childcare needs were an additional barrier that exacerbated spatial inequities.

Similarly, individuals with substance use disorders were noted to be a population susceptible to unmet childcare needs (n = 8), including the two studies previously mentioned exploring unhoused patients with addiction. Among patients with substance use disorders with childcare barriers, studies included female sex workers in northern Mexico with history of drug use (77), pregnant post-incarcerated women seeking treatment for OUD (85), among others (50, 89, 91, 100, 117). Individuals with substance use disorders often faced numerous barriers when seeking treatment, including financial difficulty, lack of insurance, and stigma, all factors compounded by extenuating childcare needs.

4 Discussion

This scoping review of childcare needs as a barrier to healthcare access identified five prominent themes from 91 inclusion studies: the role of childcare needs as a barrier to attending healthcare appointments; the opportunity for alternative care delivery models to circumvent childcare barriers; the impact of childcare needs on participation in medical research; the exacerbation of childcare needs during the COVID-19 pandemic; and the disproportionate impact of unmet childcare needs among marginalized populations. The data demonstrate that access to childcare is a SDOH that profoundly affects access to healthcare, from the ability to attend healthcare appointments to driving the transformation of care delivery models. While attention to childcare needs in the medical and public health literature is steadily increasing over time (Figure 2), additional investigation is needed to understand the mechanisms of childcare barriers in different disease states and practice settings and test interventions for childcare needs.

Our analysis demonstrated that the majority of studies on childcare needs in healthcare explore the role of childcare barriers on appointment completion and deferral of medical care (theme #1). Childcare barriers to attending healthcare appointments were represented across a variety of clinical contexts, unsurprisingly in women’s health settings like obstetric care and family planning, but also in the domains of substance use disorder treatment, cancer screening and treatment, and mental health. The breadth of relevance of childcare barriers across disease states and care settings suggests how widespread childcare needs are as a HRSN and how they may impact presentation to and engagement in healthcare through multiple heterogeneous mechanisms. Nonetheless, our analysis does find that childcare needs were often included in studies as one of multiple social determinants (n = 47, 51.6% of studies categorized in theme #1), rather than a discrete social need. Indeed, in screening of eligible studies, abstract texts and introductions of some studies referenced the term childcare but failed to study childcare needs as a variable or even allocate dedicated discussion to the role of childcare needs (n = 4). To truly characterize access to childcare as a SDOH, focused analysis is needed with dedicated attention to the role of childcare as a distinct driver of healthcare access. Importantly, current standardized tools to screen for HRSN do not proactively screen for childcare or caregiving needs (118–120); our findings would support incorporation of childcare needs in routine HRSN questionnaires to increase screening and ultimately inform intervention design.

Within theme #1’s focus on the impact of childcare barriers on timely appointment completion, theme #3 similarly found childcare barriers to participating in research. The theme of research participation is of unique interest given increasing attention to the need for diversification of medical research and clinical trials (121, 122), and disparities in clinical outcomes related to differential access to cutting-edge therapeutics (123, 124). All studies included in this theme intentionally acknowledged an understanding of childcare limiting research participation and facilitated childcare support to maximize recruitment, particularly for minoritized populations. Childcare needs commonly affect multiple aspects of research involvement, including limiting caregivers’ participation in both short-term focus group sessions and long-term clinical trials. While most research recruitment interventions addressed childcare needs with on-site childcare services, future work in this area may consider how alternative care delivery models, including community outreach methods, can improve access to research participation by reducing constraints from childcare needs.

Theme #2 highlighted the opportunity for care delivery redesign to circumvent the childcare barriers of themes #1 and #3. While possible solutions to attending in-person appointments explored in theme #1 included on-site childcare facilities, subsidizing childcare facilities, subsidizing childcare, or dedicated case management for childcare services, theme #2 highlighted the opportunity to develop new healthcare delivery systems obviating the need to travel to appointments altogether, namely through telehealth and home-based care models. This theme’s spotlight on the rise of telehealth intersects with theme #4 exploring the impact of COVID-19 on childcare needs, as pandemic conditions also galvanized and accelerated virtual care. While the COVID-19 pandemic affected many aspects of healthcare delivery and impacted the population at large, individuals with childcare needs experienced exponentiated difficulty accessing healthcare while balancing competing demands of social distancing, childcare responsibilities in the absence of schools and daycares, and their own health needs (125, 126). Consistent with prior literature exploring SDOH amidst pandemic conditions (127–129), theme #4 highlighted how the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated and unmasked pre-existing inequities related to childcare responsibilities.

Theme #5 traversed across the preceding four themes, highlighting the intersection of childcare needs with other domains of social vulnerability. Unsurprisingly, studies suggested that individuals from marginalized backgrounds based on their race and ethnicity, income-level, or experiencing social risk factors (e.g., navigating homelessness, financial strain, recent immigration) are disproportionately affected by unmet childcare needs. Vulnerable populations experienced unique considerations in the experience of childcare needs including fear of losing custody of their children, institutional policies restricting bringing children to appointments, and competing financial demands including paying for childcare or taking time off work. Theme #5 points to structural inequities that belie childcare needs: gender inequity and misogyny, income inequality, systemic racism and xenophobia, among others. These structural factors lie upstream of intersecting SDOH that can amplify and compete with childcare needs: homelessness, food insecurity, transportation barriers, and financial insecurity (130–133). Structural interventions through childcare policy reform such as subsidies, tax credits, and expansion of Head Start and Early Head Start programs (19, 134) have the potential to alleviate childcare needs through social supports; such policy interventions have the potential for collateral benefits to other co-occurring SDOH.

This review collated sources utilizing heterogeneous methodologies, including qualitative analysis, survey methods, observational study design, and randomized controlled trials. Qualitative and survey methods predominated; this finding is consistent with the relative nascency of childcare needs as a research topic in the medical and public health literature, recognizing that open-ended and descriptive analyses are needed to guide future research questions. Even among randomized controlled trials in the inclusion studies (n = 3), childcare needs were explored as a variable affecting recruitment strategies or as a mediating factor, not as an exposure or outcome. Additional studies examining childcare needs as the primary exposure of interest are needed to establish clearer causal pathways between childcare needs and health outcomes. Existing literature remains at the descriptive base of the evidence hierarchy; future research should explore causal inference between childcare needs and health outcomes with more advanced methodologies, policy evaluation, and ultimately through intervention testing. Future research could unpack multiple potential mechanisms through which childcare needs affect healthcare access: appointment adherence, delayed or deferred care, competing HRSN, convenience of healthcare, and balancing childcare and self-care. In this review, barriers posed by childcare needs to attending appointments emerged as the most prominent causal mechanism identified, and these studies were most likely to recommend onsite childcare for future intervention testing.

This review revealed other important gaps in the literature. Notably, the vast majority of studies were conducted in developed countries in North America and Europe (n = 85, 93.4%). The experience of childcare needs in developing countries remains underrepresented in the current literature, and the five themes identified in our analysis may not generalize to under-resourced settings. For example, the relevance of childcare barriers to research participation (theme #3) may be of lower priority in lower-income countries, and alternative care delivery models through community outreach or self-care innovations may be more relevant than digital health interventions (theme #2). Theme #5, exploring the role of childcare needs alongside other measures of marginalization, would be particularly salient in these settings. Additional research in these countries is needed, especially given that the disproportionate childrearing responsibilities borne by women are implicated in gender inequities in developing countries (135).

Moreover, the vast majority of study populations among inclusion studies were women; 64.8% (n = 59) were comprised exclusively of women, and only 2 studies were comprised of a majority of men. This finding stresses the inequitable burden of caregiving responsibilities faced by women and the unique relevance of access to childcare as a SDOH among women. Nonetheless, the current literature may undervalue the childcare contributions made by men (136) and underestimate the role of childcare barriers faced by male caregivers; additional research is needed to capture these experiences. Holistic approaches, inclusive of diverse family structures, are needed to advance public health understanding of access to childcare as a SDOH.

Our review has key limitations. As a scoping review, the broad goal of this study in surveying multiple disciplines across diverse literature sources necessitated the inclusion of heterogeneous study designs. To query interdisciplinary sources of literature, we searched across databases, including outside healthcare sources, which may not have been completely comprehensive. The heterogeneous results of our interdisciplinary search make it difficult to systematically appraise the quality of studies for exclusion in our study criteria. Similarly, broad descriptions of childcare, consisting of variable ages, numbers of children, and types of relationships between child and caregiver, were accepted in surveying the literature since there was no standardized definition for childcare and our study team sought to define “caregiver” inclusively. Lastly, there may be studies published since June 1, 2023, the time the search was conducted, on this topic that were not included based on our criteria. It is important to note that the critical appraisal for access to childcare as a SDOH remains nascent in the literature. The purpose of this scoping review was to serve as a starting point for new lines of inquiry to understand access to childcare through the lens of SDOH. Strengths of this review include an inclusive search strategy that aggregated inclusion studies from diverse, interdisciplinary sources. Additionally, we opted for full-text reviews during our eligibility process in contrast to initial abstract screening typically performed in scoping reviews as we quickly learned that potentially eligible articles failed to mention childcare in the entirety of the abstract. This was a common finding that illustrates the cursory treatment of childcare needs alongside other barriers to healthcare access. Full-text source review enabled our team to assess the heterogeneity of childcare needs represented in the current literature.

As our current healthcare system moves toward structural changes to truly increase access to care, this review demonstrates growing evidence for the role of childcare needs as a driver of healthcare access. The role of childcare needs should be further explored as medicine and public health work to make healthcare more accessible to all populations. The relevance of childcare needs in women’s health and marginalized populations requires an intersectional approach, as highlighted in our study findings. As an underrecognized HRSN, childcare needs warrant adoption of screening to better understand the extent of childcare barriers in access to care and to inform development and implementation of interventions. Future research dedicated to access to childcare as a distinct, clinically significant SDOH is needed to improve equitable access to care.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

MM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KK: Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. KB: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. BB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AG: Conceptualization, Supervision, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Program for the Development and Evaluation of Model Community Health Initiatives supported by the Office of the President of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding institution.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Social Determinants of Health . World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health (Accessed October 24, 2022).

2. Andersen, RM, and Davidson, PL. Improving access to Care in America: individual and contextual indicators In: Changing the U.S. health care system: key issues in health services policy and management. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA, US: Jossey-Bass (2007). 3–31.

3. Aday, LA, and Andersen, R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. (1974) 9:208–20.

4. Marmot, M, and Allen, JJ. Social determinants of health equity. Am J Public Health. (2014) 104:S517–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302200

5. Bambra, C, Gibson, M, Sowden, A, Wright, K, Whitehead, M, and Petticrew, M. Tackling the wider social determinants of health and health inequalities: evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2010) 64:284–91. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.082743

6. Boom, K, Lopez, M, Daheri, M, Gowen, R, Milbourne, A, Toscano, P, et al. Perspectives on cervical cancer screening and prevention: challenges faced by providers and patients along the Texas-Mexico border. Perspect Public Health. (2019) 139:199–205. doi: 10.1177/1757913918793443

7. Jiang, C, Yabroff, KR, Deng, L, Wang, Q, Perimbeti, S, Shapiro, CL, et al. Self-reported transportation barriers to health care among US Cancer survivors. JAMA Oncol. (2022) 8:775–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.0143

8. Adu, MD, Malabu, UH, Malau-Aduli, AEO, and Malau-Aduli, BS. Enablers and barriers to effective diabetes self-management: a multi-national investigation. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0217771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217771

9. Alcaraz, KI, Wiedt, TL, Daniels, EC, Yabroff, KR, Guerra, CE, and Wender, RC. Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: a blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA Cancer J Clin. (2020) 70:31–46. doi: 10.3322/caac.21586

10. Ahmed, SM, Lemkau, JP, Nealeigh, N, and Mann, B. Barriers to healthcare access in a non-elderly urban poor American population. Health Soc Care Commun. (2001) 9:445–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2001.00318.x

11. Wolfe, MK, McDonald, NC, and Holmes, GM. Transportation barriers to health Care in the United States: findings from the National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2017. Am J Public Health. (2020) 110:815–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305579

12. Peipins, LA, Soman, A, Berkowitz, Z, and White, MC. The lack of paid sick leave as a barrier to cancer screening and medical care-seeking: results from the National Health Interview Survey. BMC Public Health. (2012) 12:520. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-520

13. DeRigne, L, Stoddard-Dare, P, Collins, C, and Quinn, L. Paid sick leave and preventive health care service use among U.S. working adults. Prev Med. (2017) 99:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.01.020

14. Braveman, PA, Egerter, SA, and Mockenhaupt, RE. Broadening the focus: the need to address the social determinants of health. Am J Prev Med. (2011) 40:S4–S18. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.002

15. Knighton, AJ, Stephenson, B, and Savitz, LA. Measuring the effect of social determinants on patient outcomes: a systematic literature review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2018) 29:81–106. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0009

16. Ranji, U, Rosenzweig, C, Gomez, I, and Published, AS. Executive summary: 2017 Kaiser Women’s health survey. KFF. (2018). Available at: https://www.kff.org/report-section/executive-summary-2017-kaiser-womens-health-survey/ (Accessed May 30, 2024).

17. Families (ACF) A for C and Biden-Harris Administration Announces New Rule to Reduce Costs for More than 100,000 Families Receiving Child Care Subsidies . (2024). Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2024/02/29/biden-harris-administration-announces-new-rule-reduce-costs-more-than-100000-families-receiving-child-care-subsidies.html (Accessed May 30, 2024)

18. Feyman, Y, Fener, NE, and Griffith, KN. Association of Childcare Facility Closures with Employment Status of US women vs men during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. (2021) 2:e211297. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1297

19. Costly and Unavailable . America lacks sufficient child care supply for infants and toddlers. Center for American Progress. (2020). Available at: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/costly-unavailable-america-lacks-sufficient-child-care-supply-infants-toddlers/ (Accessed February 26, 2023).

20. Sandstrom, H, and Chaudry, A. ‘You have to choose your childcare to fit your work’: childcare decision-making among low-income working families. J Children Poverty. (2012) 18:89–119. doi: 10.1080/10796126.2012.710480

21. Jung, A-K, and O’Brien, KM. The profound influence of unpaid work on Women’s lives: an overview and future directions. J Career Dev. (2019) 46:184–200. doi: 10.1177/0894845317734648

22. Noursi, S, Clayton, JA, Shieh, C-Y, Sharon, L, Hopkins, D, Simms, D, et al. Developing the process and tracking the implementation and evaluation of the National Institutes of Health strategic plan for Women’s Health Research. Glob Adv Health Med. (2021) 10:21649561211042583. doi: 10.1177/21649561211042583

23. Coakley, M, Fadiran, EO, Parrish, LJ, Griffith, RA, Weiss, E, and Carter, C. Dialogues on diversifying clinical trials: successful strategies for engaging women and minorities in clinical trials. J Womens Health. (2012) 21:713–6. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3733

24. Hankivsky, O, Reid, C, Cormier, R, Varcoe, C, Clark, N, Benoit, C, et al. Exploring the promises of intersectionality for advancing women’s health research. Int J Equity Health. (2010) 9:5. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-9-5

25. Chung, EK, Siegel, BS, Garg, A, Conroy, K, Gross, RS, Long, DA, et al. Screening for social determinants of health among children and families living in poverty: a guide for clinicians. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. (2016) 46:135–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2016.02.004

26. Moore, TG, McDonald, M, Carlon, L, and O’Rourke, K. Early childhood development and the social determinants of health inequities. Health Promot Int. (2015) 30:ii102–15. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav031

27. Workman, Simon, and Hamm, Katie. 6 state strategies to improve child care policies during the pandemic and beyond. (2023). Available at: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/6-state-strategies-improve-child-care-policies-pandemic-beyond/ (Accessed August 24, 2023).

28. Healthy People 2010 . Centers for Disease Control National Center for Health Statistics. (2023). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2010.htm (Accessed May 30, 2024).

29. Sasaki, Y, Ali, M, Sathiarany, V, Kanal, K, and Kakimoto, K. Prevalence and barriers to HIV testing among mothers at a tertiary care hospital in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Barriers to HIV testing in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. BMC Public Health. (2010) 10:494. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-494

30. Pollock, D, Peters, MDJ, Khalil, H, McInerney, P, Alexander, L, Tricco, AC, et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. (2023) 21:520–32. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-22-00123

31. Heaman, MI, Moffatt, M, Elliott, L, Sword, W, Helewa, ME, Morris, H, et al. Barriers, motivators and facilitators related to prenatal care utilization among inner-city women in Winnipeg, Canada: a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2014) 14:227. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-227

32. Heaman, MI, Sword, W, Elliott, L, Moffatt, M, Helewa, ME, Morris, H, et al. Barriers and facilitators related to use of prenatal care by inner-city women: perceptions of health care providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2015) 15:2. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0431-5

33. Heaman, MI, Sword, W, Elliott, L, Moffatt, M, Helewa, ME, Morris, H, et al. Perceptions of barriers, facilitators and motivators related to use of prenatal care: a qualitative descriptive study of inner-city women in Winnipeg, Canada. SAGE Open Med. (2015) 3:2050312115621314. doi: 10.1177/2050312115621314

34. Delvaux, T, Buekens, P, Godin, I, and Boutsen, M. Barriers to prenatal care in Europe. Am J Prev Med. (2001) 21:52–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00315-4

35. Peahl, AF, Moniz, MH, Heisler, M, Doshi, A, Daniels, G, Caldwell, M, et al. Experiences with prenatal care delivery reported by black patients with low income and by health care workers in the US. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e2238161. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.38161

36. Nothnagle, M, Marchi, K, Egerter, S, and Braveman, P. Risk factors for late or no prenatal care following Medicaid expansions in California. Matern Child Health J. (2000) 4:251–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1026647722295

37. Ayres, A, Chen, R, Mackle, T, Ballard, E, Patterson, S, Bruxner, G, et al. Engagement with perinatal mental health services: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2019) 19:170. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2320-9

38. Schwartz, H, McCusker, J, Law, S, Zelkowitz, P, Somera, J, and Singh, S. Perinatal mental healthcare needs among women at a community hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. (2021) 43:322–328.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2020.08.015

39. Goodman, JH . Women’s attitudes, preferences, and perceived barriers to treatment for perinatal depression. Birth. (2009) 36:60–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00296.x

40. Fair, F, Marvin-Dowle, K, Arden, M, and Soltani, H. Healthy weight services in England before, during and after pregnancy: a mixed methods approach. BMC Health Serv Res. (2020) 20:572. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05440-x

41. Martis, R, Brown, J, McAra-Couper, J, and Crowther, CA. Enablers and barriers for women with gestational diabetes mellitus to achieve optimal glycaemic control - a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2018) 18:91. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1710-8

42. Rivers, P, Hingle, M, Ruiz-Braun, G, Blew, R, Mockbee, J, and Marrero, D. Adapting a family-focused diabetes prevention program for a federally qualified health center: a qualitative report. Sci Diabetes Self Manag Care. (2020) 46:161–8. doi: 10.1177/0145721719897587

43. Maisa, A, Milligan, S, Quinn, A, Boulter, D, Johnston, J, Treanor, C, et al. Vaccination against pertussis and influenza in pregnancy: a qualitative study of barriers and facilitators. Public Health. (2018) 162:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.05.025

44. Chan, SE, Nowik, CM, Pudwell, J, and Smith, GN. Standardized postpartum follow-up for women with pregnancy complications: barriers to access and perceptions of maternal cardiovascular risk. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. (2021) 43:746–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2021.03.006

45. Boehme, AK, Davies, SL, Moneyham, L, Shrestha, S, Schumacher, J, and Kempf, M-C. A qualitative study on factors impacting HIV care adherence among postpartum HIV-infected women in the rural southeastern USA. AIDS Care. (2014) 26:574–81. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.844759

46. Webb, DA, Mathew, L, and Culhane, JF. Lessons learned from the Philadelphia collaborative preterm prevention project: the prevalence of risk factors and program participation rates among women in the intervention group. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2014) 14:368. doi: 10.1186/s12884-014-0368-0

47. Sakai-Bizmark, R, Kumamaru, H, Estevez, D, Neman, S, Bedel, LEM, Mena, LA, et al. Reduced rate of postpartum readmissions among homeless compared with non-homeless women in New York: a population-based study using serial, Cross-sectional data. BMJ Qual Saf. (2022) 31:267–77. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-012898

48. Van Ryswyk, EM, Middleton, PF, Hague, WM, and Crowther, CA. Women’s views on postpartum testing for type 2 diabetes after gestational diabetes: six month follow-up to the DIAMIND randomised controlled trial. Prim Care Diabetes. (2016) 10:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2015.07.003

49. Sinha, DD, Williams, RC, Hollar, LN, Lucas, HR, Johnson-Javois, B, Miller, HB, et al. Barriers and facilitators to diabetes screening and prevention after a pregnancy complicated by gestational diabetes. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0277330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0277330

50. Nyamathi, AM, Sinha, S, Ganguly, KK, William, RR, Heravian, A, Ramakrishnan, P, et al. Challenges experienced by rural women in India living with AIDS and implications for the delivery of HIV/AIDS care. Health Care Women Int. (2011) 32:300–13. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2010.536282

51. Klaman, SL, Lorvick, J, and Jones, HE. Provision of and barriers to integrating reproductive and sexual health Services for Reproductive-age Women in opioid treatment programs. J Addict Med. (2019) 13:422–9. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000519

52. Minian, N, Penner, J, Voci, S, and Selby, P. Woman focused smoking cessation programming: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. (2016) 16:17. doi: 10.1186/s12905-016-0298-2

53. Aiken, ARA, Guthrie, KA, Schellekens, M, Trussell, J, and Gomperts, R. Barriers to accessing abortion services and perspectives on using mifepristone and misoprostol at home in Great Britain. Contraception. (2018) 97:177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.09.003

54. Clark, CR, Baril, N, Hall, A, Kunicki, M, Johnson, N, Soukup, J, et al. Case management intervention in cervical cancer prevention: the Boston REACH coalition women’s health demonstration project. Prog Community Health Partnersh. (2011) 5:235–47. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0034

55. Abdullahi, A, Copping, J, Kessel, A, Luck, M, and Bonell, C. Cervical screening: perceptions and barriers to uptake among Somali women in Camden. Public Health. (2009) 123:680–5. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.09.011

56. Augusto, EF, Rosa, MLG, Cavalcanti, SMB, and Oliveira, LHS. Barriers to cervical cancer screening in women attending the family medical program in Niterói, Rio de Janeiro. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2013) 287:53–8. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2511-3

57. Logan, L, and McIlfatrick, S. Exploring women’s knowledge, experiences and perceptions of cervical cancer screening in an area of social deprivation. Eur J Cancer Care. (2011) 20:720–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01254.x

58. Hulme, J, Moravac, C, Ahmad, F, Cleverly, S, Lofters, A, Ginsburg, O, et al. “I want to save my life”: conceptions of cervical and breast cancer screening among urban immigrant women of south Asian and Chinese origin. BMC Public Health. (2016) 16:1077. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3709-2

59. Freedman, RA, Revette, AC, Hershman, DL, Silva, K, Sporn, NJ, Gagne, JJ, et al. Understanding breast Cancer knowledge and barriers to treatment adherence: a qualitative study among breast Cancer survivors. BioResearch Open Access. (2017) 6:159–68. doi: 10.1089/biores.2017.0028

60. Al-Azri, M, and Al-Awaisi, H. Exploring causes of delays in help-seeking behaviours among symptomatic Omani women diagnosed with late-stage breast cancer - a qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2022) 61:102229. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2022.102229

61. Callister, LC, Beckstrand, RL, and Corbett, C. Postpartum depression and help-seeking behaviors in immigrant Hispanic women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. (2011) 40:440–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01254.x

62. Canty, HR, Sauter, A, Zuckerman, K, Cobian, M, and Grigsby, T. Mothers’ perspectives on follow-up for postpartum depression screening in primary care. J Dev Behav Pediatr. (2019) 40:139–43. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000628

63. KFF . Published: racial and ethnic disparities in Women’s health coverage and access to care. (2004). Available at: https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-womens-health/ (Accessed May 30, 2024).

64. Beavis, AL, Sanneh, A, Stone, RL, Vitale, M, Levinson, K, Rositch, AF, et al. Basic social resource needs screening in the gynecologic oncology clinic: a quality improvement initiative. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2020) 223:735.e1–735.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.028

65. FPM. Three tools for screening for social determinants of health. (2018). Available at: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/fpm/blogs/inpractice/entry/social_determinants.html (Accessed May 30, 2024).

66. Alvarez, KS, Bhavan, K, Mathew, S, Johnson, C, McCarthy, A, Garcia, B, et al. Addressing childcare as a barrier to healthcare access through community partnerships in a large public health system. BMJ Open Qual. (2022) 11:e001964. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001964

67. Andrejek, N, Hossain, S, Schoueri-Mychasiw, N, Saeed, G, Zibaman, M, Puerto Niño, AK, et al. Barriers and facilitators to resuming in-person psychotherapy with perinatal patients amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a multistakeholder perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:12234. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182212234

68. Appel, PW, Ellison, AA, Jansky, HK, and Oldak, R. Barriers to enrollment in drug abuse treatment and suggestions for reducing them: opinions of drug injecting street outreach clients and other system stakeholders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. (2004) 30:129–53. doi: 10.1081/ada-120029870

69. Fitzpatrick, TR, and Remmer, J. Needs, expectations and attendance among participants of a cancer wellness Centre in Montreal, Quebec. J Cancer Surviv. (2011) 5:235–46. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0176-8

70. Handler, A, Henderson, V, Johnson, R, Turino, C, Gordon, M, Franck, M, et al. The well-woman project: listening to Women’s voices. Health Equity. (2018) 2:395–403. doi: 10.1089/heq.2018.0031

71. Hanney, WJ, Munyon, MD, Mangum, LC, Rovito, MJ, Kolber, MJ, and Wilson, AT. Perceived barriers to accessing physical therapy services in Florida among individuals with low back pain. Front Health Serv. (2022) 2:1032474. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.1032474

72. Hilton, NZ, and Turan, C. Availability of services for parents living with mental disorders: a province-wide survey. Psychiatr Rehabil J. (2014) 37:194–200. doi: 10.1037/prj0000055

73. Hoskote, M, Hamad, R, Gosliner, W, Sokal-Gutierrez, K, Dow, W, and Fernald, LCH. Social and economic factors related to healthcare delay among low-income families during COVID-19: results from the ACCESS observational study. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2022) 33:1965–84. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2022.0148

74. Borland, T, Babayan, A, Irfan, S, and Schwartz, R. Exploring the adequacy of smoking cessation support for pregnant and postpartum women. BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:472. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-472

75. Betancourt, GS, Colarossi, L, and Perez, A. Factors associated with sexual and reproductive health care by Mexican immigrant women in new York City: a mixed method study. J Immigr Minor Health. (2013) 15:326–33. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9588-4

76. Benson, AB, Boehmer, L, Shivakumar, L, Trosman, JR, Weldon, CB, Hahn, EA, et al. Resource and reimbursement barriers to comprehensive cancer care (CCC) delivery: an Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC) survey research analysis. JCO. (2020) 38:2075–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.2075

77. Bazzi, AR, Syvertsen, JL, Rolón, ML, Martinez, G, Rangel, G, Vera, A, et al. Social and structural challenges to drug cessation among couples in northern Mexico: implications for drug treatment in underserved communities. J Subst Abus Treat. (2016) 61:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.08.007

78. White-Means, S, Dapremont, J, Davis, BD, and Thompson, T. Who can help us on this journey? African American woman with breast Cancer: living in a City with extreme health disparities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1126. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041126

79. Stirling Cameron, E, Ramos, H, Aston, M, Kuri, M, and Jackson, L. “COVID affected us all:” the birth and postnatal health experiences of resettled Syrian refugee women during COVID-19 in Canada. Reprod Health. (2021) 18:256. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01309-2

80. Slaunwhite, AK . The role of gender and income in predicting barriers to mental health Care in Canada. Commun Ment Health J. (2015) 51:621–7. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9814-8

81. Rodin, D, Silow-Carroll, S, Cross-Barnet, C, Courtot, B, and Hill, I. Strategies to promote postpartum visit attendance among Medicaid participants. J Womens Health. (2019) 28:1246–53. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7568

82. Nock, MR, Barbieri, JS, Krueger, LD, and Cohen, JM. Racial and ethnic differences in barriers to care among US adults with chronic inflammatory skin diseases: a cross-sectional study of the all of US research program. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2023) 88:568–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.09.054

83. Marshall, V, Stryczek, KC, Haverhals, L, Young, J, Au, DH, Ho, PM, et al. The focus they deserve: improving women veterans’ health care access. Womens Health Issues. (2021) 31:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2020.12.011

84. Lee, R, and North, N. Barriers to Maori sole mothers’ primary health care access. J Prim Health Care. (2013) 5:315–21. doi: 10.1071/HC13315

85. King, Z, Kramer, C, Latkin, C, and Sufrin, C. Access to treatment for pregnant incarcerated people with opioid use disorder: perspectives from community opioid treatment providers. J Subst Abus Treat. (2021) 126:108338. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108338

86. Kadaluru, UG, Kempraj, VM, and Muddaiah, P. Utilization of oral health care services among adults attending community outreach programs. Indian J Dent Res. (2012) 23:841–2. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.111290

87. Johnson, CL, Schwartz, H, Greenberg, A, Hernandez, S, Nnamani Silva, ON, Wong, LE, et al. Patient perceptions on barriers and facilitators to accessing low-acuity surgery during COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Res. (2021) 264:30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2021.01.028

88. Huang, BB, Radha Saseendrakumar, B, Delavar, A, and Baxter, SL. Racial disparities in barriers to Care for Patients with Diabetic Retinopathy in a Nationwide cohort. Transl Vis Sci Technol. (2023) 12:14. doi: 10.1167/tvst.12.3.14

89. Damle, M, Wurtz, H, and Samari, G. Racism and health care: experiences of Latinx immigrant women in NYC during COVID-19. SSM Qual Res Health. (2022) 2:100094. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100094

90. Chatterjee, A, Yu, EJ, and Tishberg, L. Exploring opioid use disorder, its impact, and treatment among individuals experiencing homelessness as part of a family. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2018) 188:161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.012

91. Stirling Cameron, E, Aston, M, Ramos, H, Kuri, M, and Jackson, L. The postnatal experiences of resettled Syrian refugee women: access to healthcare and social support in Nova Scotia, Canada. Midwifery. (2022) 104:103171. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.103171

92. Morrow, K, and Costello, T. HIV, STD and hepatitis prevention among women in methadone maintenance: a qualitative and quantitative needs assessment. AIDS Care. (2004) 16:426–33. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001683367

93. Kubo, A, Aghaee, S, Kurtovich, EM, Nkemere, L, Quesenberry, CP, McGinnis, MK, et al. mHealth mindfulness intervention for women with moderate-to-moderately-severe antenatal depressive symptoms: a pilot study within an integrated health care system. Mindfulness. (2021) 12:1387–97. doi: 10.1007/s12671-021-01606-8

94. Pearson, CA, Stevens, MP, Sanogo, K, and Bearman, GML. Access and barriers to healthcare vary among three neighboring communities in northern Honduras. Int J Family Med. (2012) 2012:298472:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2012/298472

95. Pandey, M, Kamrul, R, Michaels, CR, and McCarron, M. Identifying barriers to healthcare access for new immigrants: a qualitative study in Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. J Immigr Minor Health. (2022) 24:188–98. doi: 10.1007/s10903-021-01262-z

96. Shippee, ND, Shippee, TP, Hess, EP, and Beebe, TJ. An observational study of emergency department utilization among enrollees of Minnesota health care programs: financial and non-financial barriers have different associations. BMC Health Serv Res. (2014) 14:62. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-62

97. Peahl, AF, Powell, A, Berlin, H, Smith, RD, Krans, E, Waljee, J, et al. Patient and provider perspectives of a new prenatal care model introduced in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2021) 224:384.e1–384.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.10.008

98. Morgan, A, Goodman, D, Vinagolu-Baur, J, and Cass, I. Prenatal telemedicine during COVID-19: patterns of use and barriers to access. JAMIA Open. (2022) 5:ooab116. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooab116

99. Bruno, B, Mercer, MB, Hizlan, S, Peskin, J, Ford, PJ, Farrell, RM, et al. Virtual prenatal visits associated with high measures of patient experience and satisfaction among average-risk patients: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2023) 23:234. doi: 10.1186/s12884-023-05421-y

100. Weith, J, Fondacaro, K, and Khin, PP. Practitioners’ perspectives on barriers and benefits of Telemental health services: the unique impact of COVID-19 on resettled U.S. refugees and asylees. Community Ment Health J. (2023) 59:609–21. doi: 10.1007/s10597-022-01025-6

101. Jones, HE, Hairston, E, Lensch, AC, Marcus, LK, and Heil, SH. Challenges and opportunities during the COVID-19 pandemic: treating patients for substance use disorders during the perinatal period. Prev Med. (2021) 152:106742. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106742

102. Moreau, JL, Cordasco, KM, Young, AS, Oishi, SM, Rose, DE, Canelo, I, et al. The use of Telemental health to meet the mental health needs of women using Department of Veterans Affairs Services. Womens Health Issues. (2018) 28:181–7. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2017.12.005

103. Rosenberg, J, Sude, L, Budge, M, León-Martínez, D, Fenick, A, Altice, FL, et al. Rapid deployment of a Mobile medical clinic during the COVID-19 pandemic: assessment of dyadic maternal-child care. Matern Child Health J. (2022) 26:1762–78. doi: 10.1007/s10995-022-03483-6

104. Penaranda, E, Molokwu, J, Hernandez, I, Salaiz, R, Nguyen, N, Byrd, T, et al. Attitudes toward self-sampling for cervical cancer screening among primary care attendees living on the US-Mexico border. South Med J. (2014) 107:426–32. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000132

105. Inci, MG, Kutschke, N, Nasser, S, Alavi, S, Abels, I, Kurmeyer, C, et al. Unmet family planning needs among female refugees and asylum seekers in Germany – is free access to family planning services enough? Results of a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. (2020) 17:115. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-00962-3

106. Nicklas, JM, Zera, CA, Seely, EW, Abdul-Rahim, ZS, Rudloff, ND, and Levkoff, SE. Identifying postpartum intervention approaches to prevent type 2 diabetes in women with a history of gestational diabetes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2011) 11:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-11-23

107. Fischer, SM, Kline, DM, Min, S-J, Okuyama, S, and Fink, RM. Apoyo con Cariño: strategies to promote recruiting, enrolling, and retaining Latinos in a Cancer clinical trial. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. (2017) 15:1392–9. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.7005

108. Hildebrand, JA, Billimek, J, Olshansky, EF, Sorkin, DH, Lee, J-A, and Evangelista, LS. Facilitators and barriers to research participation: perspectives of Latinos with type 2 diabetes. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2018) 17:737–41. doi: 10.1177/1474515118780895

109. Welch, N, Hunter, W, Butera, K, Willis, K, Cleland, V, Crawford, D, et al. Women’s work. Maintaining a healthy body weight. Appetite. (2009) 53:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.04.221

110. Barkin, JL, Bloch, JR, Hawkins, KC, and Thomas, TS. Barriers to optimal social support in the postpartum period. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. (2014) 43:445–54. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12463

111. Robiner, WN, Yozwiak, JA, Bearman, DL, Strand, TD, and Strasburg, KR. Barriers to clinical research participation in a diabetes randomized clinical trial. Soc Sci Med. (2009) 68:1069–74. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.025

112. Rebbeck, TR, Bridges, JFP, Mack, JW, Gray, SW, Trent, JM, George, S, et al. A framework for promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in genetics and genomics research. JAMA Health Forum. (2022) 3:e220603. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0603

113. Palumbo, J . “Jay.” The childcare crisis: a deepening dilemma for modern families. (2023) Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenniferpalumbo/2023/12/13/the-childcare-crisis-a-deepening-dilemma-for-modern-families/ (Accessed December 13, 2023).

114. Wong, EY, Schachter, A, Collins, HN, Song, L, Ta, ML, Dawadi, S, et al. Cross-sector monitoring and evaluation framework: social, economic, and health conditions impacted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Public Health. (2021) 111:S215–23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306422

115. Figueroa, JF, Khorrami, P, Bhanja, A, Orav, EJ, Epstein, AM, and Sommers, BD. COVID-19–related insurance coverage changes and disparities in access to care among low-income US adults in 4 southern states. JAMA Health Forum. (2021) 2:e212007. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.2007

116. Ramsetty, A, and Adams, C. Impact of the digital divide in the age of COVID-19. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2020) 27:1147–8. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa078

117. Arriens, C, Aberle, T, Carthen, F, Kamp, S, Thanou, A, Chakravarty, E, et al. Lupus patient decisions about clinical trial participation: a qualitative evaluation of perceptions, facilitators and barriers. Lupus Sci Med. (2020) 7:e000360. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2019-000360

118. Billioux, Alexander, Verlander, Katherine, Anthony, Susan, and Alley, Dawn. Standardized screening for health-related social needs in clinical settings: the accountable health communities screening tool. National Academy of Medicine. (2017). Available at: https://nam.edu/standardized-screening-for-health-related-social-needs-in-clinical-settings-the-accountable-health-communities-screening-tool/ (Accessed June 30, 2023).

119. Davidson, KW, and McGinn, T. Screening for social determinants of health: the known and unknown. JAMA. (2019) 322:1037–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.10915

120. Karran, EL, Cashin, AG, Barker, T, Boyd, MA, Chiarotto, A, Dewidar, O, et al. The ‘what’ and ‘how’ of screening for social needs in healthcare settings: a scoping review. PeerJ. (2023) 11:e15263. doi: 10.7717/peerj.15263

121. Knepper, TC, and McLeod, HL. When will clinical trials finally reflect diversity? Nature. (2018) 557:157–9. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05049-5

122. Clark, LT, Watkins, L, Piña, IL, Elmer, M, Akinboboye, O, Gorham, M, et al. Increasing diversity in clinical trials: overcoming critical barriers. Curr Probl Cardiol. (2019) 44:148–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2018.11.002

123. Nazha, B, Mishra, M, Pentz, R, and Owonikoko, TK. Enrollment of racial minorities in clinical trials: old problem assumes new urgency in the age of immunotherapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. (2019) 39:3–10. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_100021

124. Kwiatkowski, K, Coe, K, Bailar, JC, and Swanson, GM. Inclusion of minorities and women in cancer clinical trials, a decade later: have we improved? Cancer. (2013) 119:2956–63. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28168

125. Petts, RJ, Carlson, DL, and Pepin, JR. A gendered pandemic: childcare, homeschooling, and parents’ employment during COVID-19. Gender Work Organ. (2021) 28:515–34. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12614

126. Sevilla, A, and Smith, S. Baby steps: the gender division of childcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. EBSCOhost. (2020) 36:S169–86. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/graa027

127. Tsai, J, and Wilson, M. COVID-19: a potential public health problem for homeless populations. Lancet Public Health. (2020) 5:e186–7. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30053-0

128. Chen, KL, Brozen, M, Rollman, JE, Ward, T, Norris, KC, Gregory, KD, et al. How is the COVID-19 pandemic shaping transportation access to health care? Trans Res Interdisciplin Perspect. (2021) 10:100338. doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2021.100338

129. Gundersen, C, Hake, M, Dewey, A, and Engelhard, E. Food insecurity during COVID-19. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. (2020) 43:153–61. doi: 10.1002/aepp.13100

130. Grant, R, Gracy, D, Goldsmith, G, Shapiro, A, and Redlener, IE. Twenty-five years of child and family homelessness: where are we now? Am J Public Health. (2013) 103:e1–e10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301618

131. Heflin, C, Arteaga, I, and Gable, S. The child and adult care food program and food insecurity. Soc Serv Rev. (2015) 89:77–98. doi: 10.1086/679760

132. Ohmori, N . Mitigating barriers against accessible cities and transportation, for child-rearing households. IATSS Res. (2015) 38:116–24. doi: 10.1016/j.iatssr.2015.02.003

133. Ganguly, AP, Alvarez, KS, Mathew, SR, Soni, V, Vadlamani, S, Balasubramanian, BA, et al. Intersecting social determinants of health among patients with childcare needs: a cross-sectional analysis of social vulnerability. BMC Public Health. (2024) 24:639. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18168-8

134. Hotz, VJ, and Wiswall, M. Child care and child care policy: existing policies, their effects, and reforms. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. (2019) 686:310–38. doi: 10.1177/0002716219884078

135. Jayachandran, S . The roots of gender inequality in developing countries. Ann Rev Econ. (2015) 7:63–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115404

136. van Polanen, M, Colonnesi, C, Tavecchio, LWC, Blokhuis, S, and Fukkink, RG. Men and women in childcare: a study of caregiver–child interactions. Eur Early Child Educ Res J. (2017) 25:412–24. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2017.1308165

137. KFF . Published: health coverage and access challenges for low-income women. (2004). Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/health-coverage-and-access-challenges-for-low/ (Accessed May 30, 2024).

138. Bryant, T, Leaver, C, and Dunn, J. Unmet healthcare need, gender, and health inequalities in Canada. Health Policy. (2009) 91:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.11.002

Keywords: childcare, social determinants of health, access to healthcare, caregiver, health-related social need, health equity