95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CURRICULUM, INSTRUCTION, AND PEDAGOGY article

Front. Public Health , 26 November 2024

Sec. Public Health Education and Promotion

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1440750

Life and death education is a distinct field of study that has potential practicality and life relevance for us to consider. For example, one notable inquiry pertaining to life education teaching entails appreciation and theoretical understanding of quality life functioning (e.g., a person’s desire to attain spiritual wisdom vs. a person’s desire to attain immense financial wealth). Our research undertakings recently involved the development of a blueprint or framework, which we termed as the ‘Life + Death Education Framework’. This framework is intended to provide relevant information that may serve to assist educators, stakeholders, caregivers, etc. with their teaching practices of life and death education. We premise that to date, there is no clear consensus or agreement among educators as to what one is expected (e.g., specific learning outcome) to teach to students who wish to study and learn about life and death education (e.g., do we introduce to students the metaphysical lens about death?). Moreover, from our point of view, the Life + Death Education Framework may yield insightful guidelines and life-related benefits, such as the heightening of a person’s well-being and/or his or her daily life functioning. As such, then, the focus of the present theoretical-conceptual article is for us to provide an in-depth narrative of the Life + Death Education Framework and how this framework, or potential universal blueprint, could help introduce and clarify our proposition of a life functioning-related concept known as ‘self well-being’. Self well-being, for us, is an alternative nomenclature that may be used in place of subjective well-being.

Life (1–3) and death (4–6) education is an interesting subject discipline in the social sciences for teaching and research development. Broadly speaking, as an introduction, life and death education teaching explores the intimate relationship between life and death. More recently, via means of philosophical reasoning, we have added an additional element – namely, one’s trans-mystical understanding of life and death (7), which in this case includes the premise of ‘post-death experience’ or what we term as ‘the thereafter’ (7, 8). For example, is it plausible that life, death, and the afterlife exist on a continuum?

We premise that the theoretical tenets of life and death education (3, 6, 9, 10), commonly referenced as one distinct subject (as opposed to ‘life education’ and ‘death education’), may coincide with the study of human agency (11–13) and the study of personal well-being (14–16). That human agency (e.g., a student’s state of determination to seek his or her own career pathway), in its totality, may detail and/or include the mentioning of a person’s ‘quality life functioning’ on a daily basis. In a similar vein, life education teaching (1–3) may help to explain and/or support the intricate nature of one’s personal well-being experience (e.g., how can life education learning help improve one’s personal well-being?).

The present theoretical-conceptual article introduces a philosophical narrative that may coincide with and support the scope of Frontiers in Public Health – namely: the potential use of life and death education to help understand the underlying nature of one’s well-being functioning on a daily basis. This line of inquiry, importantly, enables us to introduce a blueprint, or a framework, that we term as the ‘Life + Death Education Framework’. We contend that the Life + Death Education Framework, which we overview and discuss in this article, has immense theoretical and practical potentials for educators, researchers, stakeholders, etc. to consider. Central to this thesis is the extent to which relevant aspects detailed in the Life + Death Education Framework (e.g., essential themes of life and death education for teaching and learning) could help explain the underlying nature of the intricacies (e.g., improvement) of personal well-being (14–16). For example, how can an educator use his or her theoretical understanding of the Life + Death Education Framework to teach students the concept of personal well-being?

Overall, then, the focus of our theoretical inquiry is to use the Life + Death Education Framework to advance the study of personal well-being (14–16). Specifically, our research advancement involves the use of the Life + Death Education Framework to propose an alternative nomenclature and/or concept, which we term as ‘self well-being’ (i.e., in place of ‘personal well-being’). That the underlying nature of self well-being, in this case, consists of and/or incorporates different facets of life and death education teaching. We begin our theoretical-conceptual article by overviewing the premise of life and death education teaching, followed by our concise explanatory account of the Life + Death Education Framework and a detailed overview of our proposition of the concept ‘self well-being’.

To our knowledge, we are the first researchers or one of the first researchers to situate the concept of personal well-being (14–16) within the study and/or the context of life education (3, 10, 17, 18). This considered viewpoint, we contend, is novel and innovative given that life education teaching imparts relevant insights that may serve to advance the study of the nature of personal well-being. Life education, in terms of focus, considers the overarching emphasis of a person’s life functioning (2, 3). “Why do I want to live?,” “What is the meaning of life and/or in life?,” and “What do I want to do in life?” are sample questions that emphasize the nature of proactive life functioning.

We recently published a theoretical-conceptual article, where we detailed the basic philosophy of the nature of life education teaching (8). We contend that the subject context of life education makes its teaching (3, 10, 17, 18), at times, somewhat philosophical and transpersonal. Life education teaching, ‘soft pure theoretical’ and ‘soft applied’ in terms of intellectual classification (19, 20), differs from other subject disciplines, such as Educational Psychology, Mathematics, Physics, and the like. As an introductory account, the uniqueness of life education, in this case, relates to the teaching and learning of the following tenets:

i. Appreciating the fact that life education teaching, which differs from death education (4, 6, 9), is proactive and positive. For example, life education emphasizes the importance of the functioning of positive attributes such as aspiration (21), celebration (22), hope (23), optimism (24), and the like. A student’s aspiration to enter medical school, in this analysis, may serve to motivate him or her to strive for exceptional success.

ii. Recognizing the proactivity of life functioning, which coincides with the study of human agency or agentic engagement (25, 26). Motivation, aspiration, optimism, and similar attributes are proactive and may serve to energize a person’s state of functioning in life (e.g., a student’s state of motivation to seek mastery of Algebra). Proactivity, contrasting to the attributes of pessimism (27), procrastination (28), disengagement (29), etc., showcases and/or reflects a firm belief in achievement of optimal best and personal experience of flow.

iii. Emphasis pertaining to the notion of what is known as ‘life trajectories’ or ‘life courses’ (7, 30). The term life trajectory, in this case, suggests that every single one of us has a broad course in life that we strive to attain. A person’s lifespan, in this analysis, may consist of him or her having multiple life trajectories (e.g., a life trajectory of him being a part-time student and a life trajectory of him being a full-time bank employee). This life education teaching contends that a person’s ‘positive life experience’ may consist of different perceptions of successful life attainment – for example, a person’s satisfaction, which arises from his or her attainment of financial wealth (i.e., materialistic attainment) vs. a person’s self-fulfilment, which arises from his or her self-transcendence experience (i.e., spiritual, non-materialistic attainment).

iv. Understand and appreciate the importance or significance of ‘life contexts’ – that perceived multiple life contexts and subsequent experiences (e.g., the life context/experience of one experiencing temporary financial constraint vs. the life context/experience of one experiencing a successful promotion at work) give rise to the formation of what is known as a ‘holistic self’ (8), which details a person’s ‘multiple selves’. In this analysis, at any moment in time and/or in context, a person may manifest or exhibit multiple selves – for example, a teenager’s self of her as being a secondary school student (i.e., ‘Self 1’) vs. her perceived self as a sibling to her brother and sisters (i.e., ‘Self 2’) vs. her perceived ‘self’ as a daughter to her parents (i.e., ‘Self 3’).

v. Appreciating the non-definitive, non-conclusive premise of life education teaching. What does the notion of the ‘essence’ of life functioning actually entail? This teaching focuses on the importance and applicability of diversity in viewpoints and interpretations, reflecting different beliefs, values, perceptions, etc. about life functioning. For example, anthropological grounding and historical-sociocultural upbringing (e.g., an Indonesian child who is reared and grows up in South Africa) may serve to instill the belief in the self-fulfilment and gratification of ‘spiritual wisdom’ (31–33) as opposed to, say, the belief in the successful attainment of formal qualifications. Non-financial and/or non-materialistic attainments, in this analysis, showcase differing understandings of positive life qualities, such as the personal experience and gratification of spirituality (e.g., sharing knowledge of Buddhist spirituality with others in the community).

vi. The teaching of the acquirement of what is known as ‘life wisdom’ (33–35), and the ‘transformation’ of this acquired life knowledge for daily life purposes (36). This premise encapsulates the importance of applied practice or the nexus between life education knowledge and practicality. For example, non-academically, a Buddhist monk may utilize his personal understanding of Buddhist spirituality (31, 33, 37) to assist others in the community. In a similar vein, a university student may use her understanding of Maslow’s (38) humanistic teaching to embrace and appreciate the significance of self-transcendence experiences.

Our research inquiries and teaching experiences of life education (3, 10, 17, 18) have led us to surmise that personal understanding of life functioning is open-ended with different transpersonal interpretations (e.g., what is the purpose(s) of life? may yield different interpretations). For us, personally, the teaching of life education emphasizes one notable thesis: the ‘cultivation’ of quality life functioning (i.e., the notion of ‘life cultivation’). Cultivation of life functioning, or the notion of ‘life cultivation’ (3, 30), reflects and showcases the practice of growth and positivity, unlike deficit reasoning, which seeks to focus on remedy and preventive measures. How can I flourish?, What can I do to improve my health functioning?, and How can I enjoy life? are typical questions and/or phrases that place emphasis on the practice of cultivation (31, 39, 40).

Cultivation (31, 39, 40) is a proactive process, which seeks to promote and foster life wisdom and different types of characters, values, experiences, etc. for quality life functioning. Existing writings from a number of scholars including us, for example, have delved into the notion of what is known as ‘spiritual cultivation’ (3, 30, 31, 41), or the cultivation of spiritual faith or spiritual belief (e.g., the cultivation of ‘Buddhist spirituality’). One typical practice or engagement that may assist with the process of cultivation, in this analysis, involves the use of meditation (42–44) and personal understanding and perceived feeling of mindfulness (45–47). Our philosophical teaching to students contends that proactive meditation practice could, in fact, assist to cultivate individuals to experience perceived feelings of contentment, inner fulfilment, peace, calmness, and other similar attributes.

The underlying premise then, from the preceding sections, is that life education teaching (3, 10, 17, 18) focuses on or places emphasis on the pursuing of life ideals and human perfection. This tenet or indication is philosophical at best and may simply reflect a utopian discourse that is unattainable. ‘Life ideals’ are altruistic and/or moralistic endeavors that all of us may aspire to. For example, a teenager learning about life education may aspire to and/or wish to pursue the life ideals of having a pacifist society where there is love, a unifying world where there is no conflict, a community that practices love, peace, and harmony, etc. In a similar vein, the notion of ‘human perfection’ is an interesting but unattainable endeavor for many of us or all of us to accomplish. Individuals and societies are not perfect. Broadly speaking, at a societal level, we are confronted with difficulties, obstacles, conflicts, problems, etc. on a daily basis. At an individual level, likewise, a person may recognize that he or she has numerous deficiencies or shortcomings to overcome that require some form of remedy, resolution, prevention, etc. (e.g., a student acknowledges that he is impatient, or a father’s own omission that he has an anger management issue).

Pursuing life ideals and human perfection, we contend, are utopic, unrealistic, and/or unattainable. Striving to attain life ideals and human perfection, however, is euphoric, inspirational, life-changing and, of course, self-fulfilling. It is, in fact, the embodiment of the ‘positivity’ of life education teaching. What does this reference actually mean? Basically, as the term connotes, life education teaching (3, 10, 17, 18) is intended and/or is structured to impart philosophical insights and humanistic understandings into the positive nature of life functioning. It is, for us, a subject area that is esthetic, altruistic, and inspirational. Its intent, in this analysis, is to introduce to society and individuals the following:

• An appreciation for the personal belief in human perfection and the attainment of life ideals.

• An appreciation for the esthetic and altruistic nature of life functioning, showcasing reverence or respect for different life trajectories.

• Seeking to cultivate or to nurture the different types of life qualities for successful life adaptation and life purposes.

• Concerted attempts to contemplate and seek meanings to the true purpose(s) of life and in life (e.g., seeking to experience an altruistic state).

• Concerted attempts to be happy and to live a cherished and self-fulfilling life.

Death education (4, 6, 48) is somewhat different from life education and seeks to understand the personal experience of death and dying. For us, life is intimately linked to death. In other words, life education teaching (3, 10, 17, 18) closely associates with death education teaching. In order to understand the true nature of death and death-related matters (e.g., “How can I overcome grief?”), one has to understand the nature of life. We acknowledge that unlike life education, which is positive, esthetic, and aspirational, the subject of death and dying is grim, dark, and somewhat depressing for any person to study, learn, research, etc. Having said this, however, we note that death education teaching also imparts interesting and valuable aspects – for example: the philosophical understanding of death (e.g., does death also mean the demise of one’s state of consciousness?), and comparative cultural beliefs and values pertaining to death (7, 48, 49).

Death education, in brief, relates to the formal teaching and learning of death and death-related matters (4, 5, 36). Death in its simplistic form relates to the demise or the ceasing of life (30). Death education teaching can, in fact, be both pragmatic and philosophical. The notion of pragmaticism of death, in this analysis, entails actual, real-life contexts for consideration, acknowledgement, practice, understanding, etc. For example, Bollig and his colleagues [(e.g., 50–52)] have written about the importance of palliative care (53, 54), given that increasingly, many choose to die at home. What educational discourse is available, in person and/or online, that may help family members? Do current initiatives pertaining to ‘Public Palliative Care Education’ (50, 52), also known as ‘PPCE’, require any refinement and/or alternative(s)? These sample questions pertaining to understanding and practice of palliative care, we contend, emphasize the pragmatic nature of death education.

In a similar vein, pragmatic teaching of death education also seeks to understand the complexity and process of grief, loss, and bereavement (55–57). What does a person go through as he or she encounters the loss of a loved one? Is there anything that can be done to help family members overcome their grief? What formal education is available to inform us and/or to impart understanding of grief, loss, and bereavement? This teaching focuses on coping mechanisms (e.g., the use of spiritual faith as a coping mechanism) that may help alleviate the negative emotions and/or feeling that often associate with grief and bereavement.1 In a similar vein, death education teaching by the late Elisabeth Kübler-Ross details five stages of grief: denial (e.g., “This can’t be me; I am perfectly fine”), anger (e.g., “Surely not! Why me, of all people?”), bargaining (e.g., “Please, let me live a few more years ….”), depression (e.g., “I’m so depressed at the moment; what’s the point? I’m going to die anyway….”), and acceptance (e.g., “It’s going to be okay….”).2

Death education (4, 5, 36), as we mentioned, is not something that many would choose to study and learn. One only has to read about war ravaged countries, natural disasters, poverty-related deaths, and other life-related negativities to recognize the profound impact of death and dying. By all accounts, death education is morbid and non-esthetic for teaching and learning. Our scholarly research work in the area of holistic and positive life functioning [(e.g., 8, 58–60)], however, has led us to consider an alternative position: that it is still possible to view and approach death education teaching, despite its morbid and dark nature, with a sense of positivity (i.e., the perception of death education as being esthetic).

Philosophical teaching of death, which we engage in with our undergraduate and postgraduate students, is non-pragmatic and encourages introspection and personal contemplation for appreciation and meaningful understanding purposes. We contend that death education teaching (4, 5, 36), in this analysis, may embrace the use of a transpersonal or trans-mystical lens (7). A trans-mystical position, in this case, encourages and/or focuses on the following:

i. Stimulating intellectual curiosity for the seeking of knowledge, which delves into the ‘unknowns’ of life and death. Known unknowns and unknown unknowns of life (e.g., is there is scientific logic to the study of premonition?) and death (e.g., where does one’s state of consciousness and/or one’s soul go after death?) are somewhat ‘mystical’ (61–63) or trans-mystical (7), and may situate outside the realm of realistic objectivity and/or the realm of ordinary human psyche. Seeking to understand and to appreciate what we do not know about the broad universal contexts at large (e.g., the logic of what is known as ‘post-death experience’) may, in fact, help to alleviate our negative emotions and feelings (e.g., grief) pertaining to death. For example, deep, meaningful understanding of the tenet of saṃsāra (64, 65) or the concept of ‘reincarnation’ (66–68) may assist a person to appreciate and/or to welcome death at any moment in time.

ii. Concerted attempts to study, learn, and appreciate the importance of diversity in cultural practice, viewpoint, interpretation, perspective, etc. of death. This line of teaching inquiry of death education, as reflected by numerous writings from scholars in China (5), Malaysia (4), Taiwan (9), Tibet (69), Tonga (70), and Vietnam (48), suggests that historical-sociocultural contexts play a notable role. For example, aside from paying respect and/or reverence for the dead, some cultural groups (e.g., Chinese families) firmly believe that partaking in the cultural ritual of ‘ancestor worshipping’ (71–73) may also enable them to communicate with loved ones who have moved one (i.e., that the practice of ancestor worshipping serves as a form of ‘spirit communication’). In a similar vein, many Taiwanese in Taiwan believe in what is known as ‘the Underworld tour’ or ‘Guan Luo Yin’, a ritual that may enable one to communicate with the dead (30).

The mentionings above are theoretical examples that we use to support our philosophical teaching of death education. Central to this teaching practice is the emphasis, which seeks to introduce to students the importance of trans-mystical understanding of the unknowns and ‘abnorms’ of death – for example, is there anything beyond death (7, 8)?, and what does the ritual of ‘ancestor worshipping’ (71, 72, 74) actually connote? This theoretical approach (e.g., a focus on the transpersonal nature of death), somewhat metaphysical in nature, differs from the pragmatic approach (52, 55, 56) and imparts and/or encourages non-definitive and inconclusive issues for us to contemplate.

There are some academic topics and subjects that are objective and relatively straightforward, showcasing clearness and consistency in terms of interpretation, viewpoint, understanding, etc. For example, the topic of Algebraic Equations such as the solving of simplification of ‘2(x + 4) + 3(x – 5) – 2y = 0’3 always yields comparable or consistent understanding, regardless of where it is taught (e.g., a teacher teaching 2(x + 4) + 3(x – 5) – 2y = 0 in South Korea and a teacher teaching 2(x + 4) + 3(x – 5) – 2y = 0 in Australia). In other words, from our viewpoint, there is some form of ‘universality’ or ‘generality’. Universality, in this case, espouses standardization, consistency, and proper structure, regardless of learning and/or sociocultural contexts.

Our research and teaching experiences inform us that universality or generality does not necessarily apply to the case of life and death education (3, 6, 9, 10). Our aforementioned narrative has included some examples (e.g., personal understanding of a need to experience self-transcendence), which may serve to highlight the ‘non-universal’ nature of life and death education teaching. There is, for example, a clear difference in opinion, idea, and/or interpretation with regard to our mentioning of the ‘continuum of life, death, and the thereafter’ (8). In this analysis, we contend that not everyone and/or every culture is inclined to accept and/or to embrace the tenet of trans-mystical or metaphysical experiences. As such, then, some aspects or many aspects in life and death education are somewhat non-concrete and non-definitive, giving rise to a wide range of viewpoints.

One interesting facet that we note is the impact of the contextual environment or the ‘contextual milieu’ at large. This mentioning of the contextual milieu, in part, associates with and reflects the theoretical premise of ‘situated cognition’ (75, 76) and Uri Bronfenbrenner’s (77, 78) bioecological systems theory. In this analysis, a person’s development (e.g., his or her cognitive growth) is ‘embedded’ or is situated in context. For example, a child’s cognitive growth is likely to flourish somewhat differently if his or her society places strong emphasis on technological advances for usage (e.g., the child, in this case, is likely to grow up, wishing to be a software engineer). A society or a culture that is technologically deprived, in contrast, is more likely to constrain a child’s cognitive growth. Limited resources (e.g., the provision of high-speed internet connection), in this analysis, may negate opportunities for technological appreciation. As a result, then, anthropological grounding and historical-sociocultural context and upbringing (e.g., a German child who is reared and grows up in Mongolia) may shape a person’s interpretation of life and/or of death differently. Individual variation, in this sense, reflects personal upbringing and the uniqueness of one’s active construction of knowledge (79, 80).

The above mentioning is paramount to our discussion of the Life + Death Education Framework. Aside from formal documentations (e.g., a formal course outline for teaching purposes), it is poignant that we structure a positive social milieu (e.g., a positive learning environment) to help facilitate the embracement and acceptance of diversity. A conducive social milieu, in this analysis, may convey specific messages of acknowledgement of distinct personal historical backgrounds, epistemological beliefs, cultural values, etc. Moreover, such environmental-learning contexts may help a child to feel at ease with his or her own viewpoint, perspective, and/or cultural belief. The issue then, however, goes back to our original mentioning: whether it is possible for us to generalize the Life + Death Education to different learning-sociocultural settings. In other words, as a question for consideration, do we need to take into account the premise of universality when constructing and/or implementing the Life + Death Education Framework?

Our research collaborations, in terms of teaching and research development (e.g., our mentioning in Section 2 and Section 3), have led us to engage in several notable undertakings, for example: (i) conceptualizations of life education for empirical research studies (e.g., exploring the positive effect, β, of benevolent engagement on one’s state of emotional well-being), (ii) philosophical inquiries that seek to provide trans-mystical understanding of life and death experiences (e.g., does the notion of ‘post-death’ experience make logical sense?), (iii) conceptual-theoretical inquiries that relate the study of life and death education to other theoretical premises (e.g., the extent to which the study of positive psychology could relate to the teaching of life and death education), and (iv) curriculum development-related activities that may provide grounding and/or guidelines for quality teaching and learning purposes (e.g., development of the Life + Death Education Framework). These undertakings, we contend, are novel and creative and may, importantly, provide innovative sights for teaching and research advancement.

The Life + Death Education Framework, which we briefly mentioned earlier, was recently developed by us to help with quality teaching and curriculum development of life and (1–3) and death (4–6) education (81). We rationalize that, to date, there is no ‘universal’ blueprint or framework that we know of that may serve to assist educators with their curriculum structures. Even our own teaching of life and death education, for example, has involved the use of specific and purposive information (i.e., what we purposively choose to teach to students about life education). This lack of formalized information and/or proper structure has led us then, over the past several years, to consider developing a universal blueprint for guidance in terms of teaching and research purposes. This blueprint, or framework, consists of five interesting aspects of for educators, researchers, policymakers, etc. to consider:

i Abroad subject overview that introduces the nature of life education and the nature of death education:

That is, a detailed overview that describes the nature of both life and death education teaching.

ii Specific learning outcomes (LOs) for student accomplishment:

A designation of life education learning outcomes (e.g., Life Education LO-1: “To be able to understand the notion of ‘value contemplation’, which seeks to introduce the tenets of reflection, contemplation, and exploration of different core values, or life characteristics, for accomplishment.”) and death education learning outcomes (e.g., Death Education LO-1: “To learn and appreciate the transpersonal nature of death and dying.”) for students to accomplish e.g., (see Table 1 for full description).

iii Core competencies for student development:

That is, a formal testament of expected ‘proficiencies’ or competencies (e.g., Core Competency 1: “To demonstrate capability to philosophize, self-reflect, and contemplate.”) pertaining to the learning of life and death education that educators want students to develop e.g., (see Table 2 for full description).

iv Specific learning themes for teaching and learning:

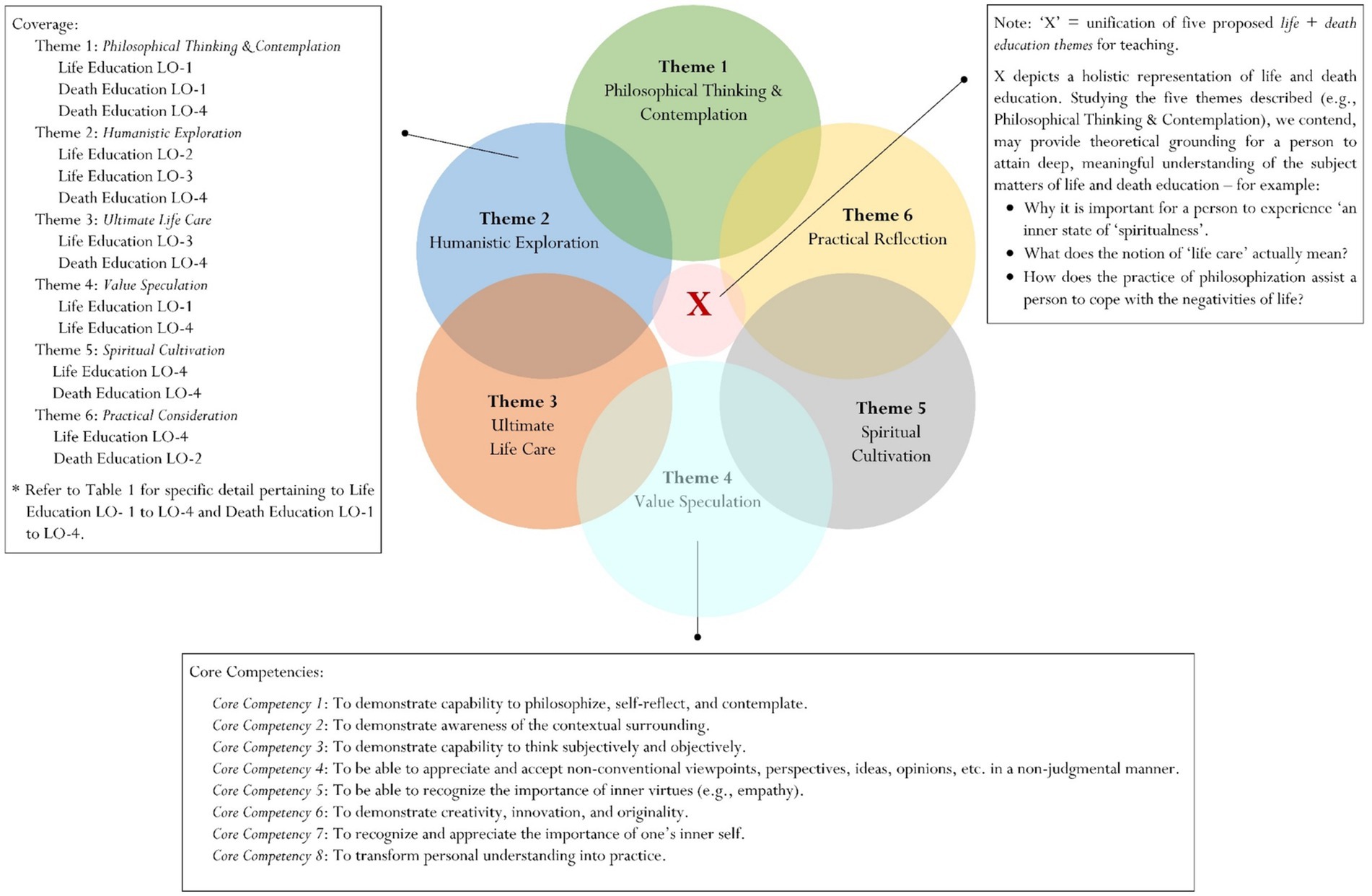

Designated topical themes of life and death education, as shown in Figure 1 and Table 3 (see for full description), for coverage in terms of teaching and learning. Overall, there are six interrelated themes for consideration:

a. Philosophical Thinking & Contemplation: is concerned with a person’s rational reflection of life knowledge, life skills, emotions, and attitudes that, in turn, may improve his or her ‘reflective thinking literacy’.

b. Humanistic Exploration: reflects a person’s interest and intellectual curiosity to seek meaningful understanding into the nature of humanism – for example: “What is a human being?,” “Who am I as a person?,” “What is it like to be human?,” etc.

c. Ultimate Life Care: relates to the issues of personal care, the true meaning of life, the intricate nature of suffering, grief, and suffering, and the aspiration, contemplation, and setting of personal goals for accomplishment.

d. Value Speculation: seeks to explore a person’s subjective viewpoint, interpretation, reasoning, judgment, etc. of what values most in life.

e. Spiritual Cultivation: is a positive endeavor that seeks to foster or cultivate one’s inner ‘incorporeal well-being’, which may consist of spiritual faith, spiritual wellness, spiritual understanding, and the like.

f. Practical Reflection: emphasizes the process of ‘transformation’, which intimates the nexus between theory and applied practice (e.g., how can I utilize my knowledge of life and death to help others in the community?).

Figure 1. Universal framework of life and death education for consideration. Note: Consult (81).

v Specific elements:

Designated elements, which there are four, for learning, attainment, and appreciation (e.g., Element: ‘Application’, which emphasizes the promotion of the application of the life and death education premise) e.g., (see Table 4 for full description).

Overall, then, the brief overview of the Life + Death Education Framework above showcases the important structures and/or guidelines for adherence to when one teaches the subject of life and death (3, 10, 17, 18). Moreover, we contend that the uniqueness of the Life + Death Education Framework lies in its established grounding that may enable and/or assist researchers with advancement and development of new theoretical premises, associations, concepts, etc. (e.g., the extent to which positive psychological teaching could help alleviate the perceived feeling of grief) (3). In this analysis, we purport that it is plausible to use the Life + Death Education Framework (i.e., the implementation of the Life + Death Education Framework) as theoretical grounding to conceptualize an alternative nomenclature and/or concept, which we term as ‘self well-being’. In the next section of the article, we explore in detail our conceptualization (e.g., Figure 2): that the Life + Death Education Framework may establish theoretical grounding to support the underlying nature of the proposed concept known as self well-being.

One important outcome of the school system or the schooling processes entails the fostering of positive well-being experiences (82, 83). This noting contends that successful schooling is more than just one’s ability to achieve exceptional school grades. In this analysis, successful schooling may involve a wide range of school-based experiences, such as one’s testimonial evidence of his or her positive well-being (16, 84). Moreover, as the literature (15, 83, 85–88) attests, positive well-being may serve as a dynamic ‘driver’ of change, helping to direct and govern a student’s behaviors, thought patterns, feelings for others, etc.

A prevalent line of inquiry exists at present, namely, what is personal well-being? This research question seeks to attain relevant insights into the meaning and underlying nature of personal well-being. Similar to the concept of intelligence (89–92), it is somewhat difficult for us to derive and/or to provide a clear, consistent definition of personal well-being. In a documentation published some years back, for example, Fraillon (15) provided a comprehensive overview of personal well-being with reference to the school contexts (i.e., the study of ‘student well-being’). According to the author’s summary, personal well-being (i.e., in this case, student well-being) is a ‘multifaceted construct’ that consists of different domains or components – for example: physical well-being, economic well-being, psychological well-being, cognitive well-being, and social well-being (93). Overviews from the Australian Catholic University (85), Dodge et al. (14), Pollard and Lee (93), Soutter (16), and others, likewise, serve to illustrate the complexity of the nature of personal well-being.

Our analysis of the literature has led to our identification of a number of key words and/or phrases that may depict the operational functioning of personal well-being – for example:

• Functioning: A person’s (e.g., student) internal state of functioning on a daily basis, including emotional, social, cognitive, and spiritual.

• Adaptation: A person’s (e.g., student) ability to successfully adapt to his or her contextual environment (e.g., classroom).

• Multidimensionality: That personal well-being (e.g., student well-being) is multidimensional or multifaceted, consisting of different domains, elements, factors, etc.

• Self-fulfilment of Needs: There is an inherent need for a person (e.g., student) to self-fulfil his or her inner needs (e.g., psychological needs).

• Positivity: That personal well-being (e.g., student well-being) is a positive construct or that it entails positive experiences. Having said this, however, it may be argued that there is also a negative scope (e.g., negative well-being experience).

• Optimal Experience: That a person’s well-being (e.g., student well-being) reflects his or her optimal experiences (e.g., optimal social experience).

• Personal Satisfaction: That personal well-being (e.g., student well-being), positive in experience, reflects and/or showcases one’s internal state of satisfaction.

Our considered interpretation of personal well-being, termed as self well-being or ‘individual self-being’ (Figure 2), is somewhat unique for its humanistic and ‘life functioning’ grounding. In this analysis, our interpretation of personal well-being uses the theoretical lens of life education teaching (e.g., our use of the Life + Death Education Framework), which differ from the existing psychological perspective (15, 85). Innovatively, the life education lens places emphasis on the practice of ‘introspection’ or introspective reflection (e.g., Theme 1: Philosophical Thinking and Contemplation, Theme 2: Humanistic Exploration), which is subjective and somewhat transpersonal. Using Theme 1 from the Life + Death Education Framework as theoretical grounding, we define introspection as:

A cognitive process, which directs a person to reflect on internalized information from the contextual environment for the purpose of seeking awareness, understanding, and appreciation of his or her inner self.

The underlying discourse then, in accordance with our proposition, is that engagement of introspection is paramount to the formation of self well-being. In this analysis, we theorize that one’s self-awareness of personal well-being experiences involves active introspective reflection, which is individual, measured, and contemplative. As such, the ‘evolution’ of a person’s self well-being is continuous and intimately associates with the process of introspection.

As shown in Figure 2, the nature or the formation of self well-being, or individual self-being, is made up of the unification of three distinct components: ‘reflective life characters’ (e.g., a person’s ‘trustworthiness’), ‘inner life values’ (e.g., a person’s ‘altruistic state’), and ‘life wisdom’ (e.g., a person’s acquired knowledge about the conflicting emotions that arise from personal experience of poverty)(See Figure 2 for detail). Central to this conceptualization is the theorization that one’s practice of introspection or introspective reflection, as defined earlier, may serve to facilitate the formation of self well-being. Every person’s self well-being, in this analysis, is unique and differs from another person’s self well-being.

Our conceptualization, derived from life education teaching (e.g., the use of the Life + Death Education Framework) (3, 10, 17, 18), contends that the underlying nature of self well-being (e.g., what is one’s personal well-being experience?) is more humanistic and transpersonal, involving a person’s inner thoughts, introspection, and philosophization. In this sense, the nature of self well-being is philosophical and open-ended, reflecting one’s attempts to introspect in order to obtain deep, meaningful understanding of the ‘inner self’, which is unique and serves to define one’s perceived sense of self-identity. Self-identity, a unification of life characters, inner life values, and life wisdom, we contend, is the embodiment of one’s ‘humanistic beingness’. That a person’s self-identity is unique and serves to define and/or espouse his or her well-being experiences. This theoretical premise, from our point of view, is significant as it:

i. Distinguishes our unique interpretation of personal well-being, which is humanistic and transpersonal, from other existing theoretical positions (e.g., the psychological position of personal well-being, which emphasizes the importance of both interpersonal and intrapersonal experiences) (15, 85). This interpretation suggests then that personal well-being, or humanistic beingness, is largely a construction of one’s own interpretation of oneself (e.g., what is an important life character or inner life value that I see as being most profound….?).

ii. Seeks to accentuate, in part, the importance of the concept of ‘self’ (8, 94–96), which delves into a person’s understanding of his or her inner nature (e.g., what is it that represents me?). Our theorization, again differing from existing theoretical viewpoints (e.g., psychological viewpoint), is unique for its attempt to relate the nature of personal well-being with the nature of self – hence, our coining of the term ‘self well-being’ (i.e., self + well-being).

iii. Emphasizes the uniqueness of acquired life wisdom (33–35), or life knowledge, as an entity of personal well-being. This conceptualization is indeed unique for its rationalization: that one’s personal well-being at the present time indicates, in part, a certain level of life wisdom, or that, alternatively, one’s acquired life wisdom level serves to highlight one’s personal well-being.

Overall, then, we contend that our use of the Life + Death Education Framework to offer an alternative interpretation of personal well-being is novel and innovative. Central to this thesis is the rationalization that personal well-being is intimately linked to the study of life and death education (3, 6, 9, 10). This considered viewpoint contends that a person’s perceived life functioning on a daily basis may serve to define his or her well-being. Perceived life functioning, in this analysis, involves a person’s introspective reflection of his or her inner self. The notion of ‘self-identity’, a contextual term that we have coined, plays an integral part in our alternative theorization of personal well-being. Self-identity, as conceptualized in Figure 2, is a ‘façade’ or a ‘self-image’ of a person that is unique, depicting his or her reflective life characters, inner life values, and acquired life wisdom. Every person’s self-identity is distinguished, showcasing his or her ‘deep, inner core’.

The Life + Death Education Framework, as overviewed in the preceding sections, is still in its early stage of evolution in terms of usage, implementation, research undertaking, etc. We acknowledge the potential limitations or caveats that may give rise to further advancement and development – for example, in terms of universality, can we apply or implement the Life + Death Education Framework to different learning-sociocultural contexts? By all accounts, our sample example regarding the use of the Life + Death Education Framework to explain the underlying nature of personal well-being (i.e., development of the concept ‘self well-being’) is simply speculative. Theoretical-conceptual inquiries (e.g., our proposition of the Life + Death Education Framework), using philosophical psychology (8, 30, 97) as a logical basis require robust empirical validation.

We urge educators, researchers, policymakers, etc. to use our Life + Death Education Framework for teaching and/or research purposes. There are several recommendations that are noteworthy for consideration. Firstly, consider refining the Life + Death Education Framework (e.g., refining the Life Education LOs) for the main purpose of contextualization (e.g., the Taiwanese learning-sociocultural context), relevance, and suitability (e.g., can a modified version of the Life + Death Education Framework be used to teach Japanese university students?). Secondly, consider using the Life + Death Education Framework as theoretical grounding for the conceptualization of a new theoretical premise (e.g., can our original version or a modified version of the Life + Death Education Framework be used to advance theoretical understanding of Public Palliative Care Education?). Thirdly, in terms of teaching and learning experiences, consider the potential generalization and/or the ‘universality’ of the Life + Death Education Framework (e.g., does the Life + Death Education Framework have the same meaning for different learning-sociocultural contexts?).

The study of life and death education (3, 6, 9, 10) is unique for its pragmatic, philosophical, and humanistic nature. Unlike other academic subjects and fields of research (e.g., Calculus), life and death education teaching may consist of subjective, non-definitive, and non-conclusive interpretations and understandings (e.g., what is the true meaning of life?). It is somewhat difficult, from our point of view, to streamline and/or to show consistency when teaching life and death education. For example, is it valid or logical for us to consider the premise of saṃsāra (64, 65), and/or the concept of ‘reincarnation’ (66–68) when teaching life and death education? Our teaching and research development over the past decade has led us to undertake an interesting discourse: the proposition of a blueprint or framework known as the ‘Life + Death Education Framework’.

The Life + Death Education Framework is unique for its theoretical tenets (e.g., LOs for accomplishment, Core Competencies for development), serving as guidelines and structures for teaching and research purposes. For example, in terms of teaching and learning, we purport that the Life + Death Education Framework may provide theoretical grounding to assist educators in their curriculum development of life and death education (e.g., what is a relevant theme pertaining to death education that is noteworthy for inclusion?). In a similar vein, for research purposes, we contend that the Life + Death Education Framework may offer informative insights, which could help researchers to formulate new ideas, theoretical premises, etc. In this analysis, as overviewed in the latter sections of this article, we used the Life + Death Education Framework to frame our conceptualization of concept, which we termed as ‘self well-being’.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

HP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BN: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. C-SH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. S-CC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

HP would like to express his appreciation to the University of New England, Armidale, Australia for allowing him to undertake his sabbatical in late 2022, which led to the preparation and writeup of this theoretical-conceptual article. A special thank you to the National Taipei University of Education and, in particular, the Department of Education for hosting the first author’s sabbatical. Finally, the four authors would like to extend their gratitude and appreciation to the Associate Editor, Abdolvahab Samavi, and the two reviewers for their insightful comments, which have helped to enhance the articulation of this conceptual analysis article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^Source: https://newsinhealth.nih.gov/2017/10/coping-grief, https://www.unicef.org/armenia/en/stories/strategies-cope-grief, https://www.apa.org/topics/families/grief.

2. ^Source: https://www.ekrfoundation.org/elisabeth-kubler-ross/, https://hdsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/13080.pdf.

3. ^Source: https://byjus.com/maths/algebraic-equations/.

1. Chen, S-C. Overview and reflection on the 20-year National Education Life Education Curriculum. Natl Educ. (2013) 53:1–6.

2. Huang, J. New orientation of life education in the 21st century: Spiritual awakening, classic study and environmental education. Proceedings of the ninth life education conference. Taiwan: Taipei City (2014).

3. Phan, HP, Ngu, BH, Chen, S-C, Wu, L, Lin, W-W, and Hsu, C-S. Introducing the study of life and death education to support the importance of positive psychology: an integrated model of philosophical beliefs, religious faith, and spirituality. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:1–16. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.580186

4. Seng, HZ, and Lee, PW. Death education in Malaysia: from challenges to implementation. Int J Practices Teach Learn. (2022) 2:1–8.

5. Shu, W, Miao, Q, Feng, J, Liang, G, Zhang, J, and Zhang, J. Exploring the needs and barriers for death education in China: getting answers from heart transplant recipients' inner experience of death. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1082979. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1082979

6. Zhu, Y, Bai, Y, Gao, Q, and Zeng, Z. Effects of a death education based on narrative pedagogy in a palliative care course among Chinese nursing students. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1194460. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1194460

7. Phan, HP, Ngu, BH, Hsu, C-S, Chen, S-C, and Wu, L-J. Expanding the scope of “trans-humanism”: situating within the framework of life and death education – the importance of a “trans-mystical mindset”. Front Psychol. (2024) 15:1380665. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1380665

8. Phan, HP, Ngu, BH, Chen, S-C, and Hsu, C-S. An ideal sense of self: proposition of holistic self and holistic mindset from the unique anthropological-sociocultural perspective of life and death education. J Theor Philos Psychol. (2024):1–28. doi: 10.1037/teo0000265

9. Fu, W. The dignity of death and the dignity of life: From dying psychiatry to modern life and death. Taipei City, Taiwan: The Middle (1993).

10. Lei, L, Lu, Y, Zhao, H, Tan, J, and Luo, Y. Construction of life-and-death education contents for the elderly: a Delphi study. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:802. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13197-7

11. Bandura, A. Growing primacy of human agency in adaptation and change in the electronic era. Eur Psychol. (2002) 7:2–16. doi: 10.1027//1016-9040.7.1.2

12. Bandura, A. Toward a psychology of human agency: pathways and reflections. Perspect Psychol Sci. (2018) 13:130–6. doi: 10.1177/1745691617699280

13. Parsell, C, Eggins, E, and Marston, G. Human agency and social work research: a systematic search and synthesis of social work literature. Br J Soc Work. (2016) 47:bcv145–255. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcv145

14. Dodge, R, Daly, AP, Huyton, J, and Sanders, LD. The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int J Wellbeing. (2012) 2:222–35. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4

15. Fraillon, J. (2004). Measuring student well-being in the context of Australian schooling: Discussion paper (E. Ministerial council on education, training and youth affairs, Ed.). The Australian Council for Research.

16. Soutter, AK. What can we learn about wellbeing in school? J Student Wellbeing. (2011) 5:1–21. doi: 10.21913/JSW.v5i1.729

17. Chen, S.-C. (2017). Constructing campus culture with life education: taking the education of HuaFan university as an example. International conference on life education, Taipei City.

18. Tsai, Y. Life and philosophy of life: definition and clarification. Commentary on Philosophy of National Taiwan University. (2008) 35:155–90.

19. Becher, T. The disciplinary shaping of the professions In: BR Clarke, editor. The academic profession. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press (1987). 271–303.

20. Becher, T. The significance of disciplinary differences. Stud High Educ. (1994) 19:151–61. doi: 10.1080/03075079412331382007

21. Carroll, A, Houghton, S, Wood, R, Unsworth, K, Hattie, J, Gordon, L, et al. Self-efficacy and academic achievement in Australian high school students: the mediating effects of academic aspirations and delinquency. J Adolesc. (2009) 32:797–817. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.009

22. Brick, D, Wight, K, Bettman, J, Chartrand, T, and Fitzsimons, G. Celebrate good times: how celebrations increase perceived social support. J Public Policy Mark. (2023) 42:115–32. doi: 10.1177/07439156221145696

23. Bernardo, ABI. Hope in early adolescence: measuring internal and external locus-of-hope. Child Indic Res. (2015) 8:699–715. doi: 10.1007/s12187-014-9254-6

24. Chen, Y, Su, J, Zhang, Y, and Yan, W. Optimism, social identity, mental health: findings form Tibetan college students in China. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:747515. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.747515

26. Williams, RN, Gantt, EE, and Fischer, L. Agency: what does it mean to be a human being? [conceptual analysis]. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.693077

27. Harpaz-Itay, Y, and Kaniel, S. Optimism versus pessimism and academic achievement evaluation. Gift Educ Int. (2012) 28:267–80. doi: 10.1177/0261429411435106

28. Wolters, CA. Understanding procrastination from a self-regulated perspective. J Educ Psychol. (2003) 95:179–87. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.179

29. Tam, FWM, Zhou, H, and Harel-Fisch, Y. Hidden school disengagement and its relationship to youth risk behaviors: a cross-sectional study in China. Int J Educ. (2012) 4:87–106. doi: 10.5296/ije.v4i2.1444

30. Phan, HP, Ngu, BH, Chen, S-C, Wu, L, Shih, J-H, and Shi, S-Y. Life, death, and spirituality: a conceptual analysis for educational research development. Heliyon. (2021) 7:e06971. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06971

31. Chattopadhyay, M. Contemplation: its cultivation and culmination through the Buddhist glasses. Front Psychol. (2022) 12:281. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.800281

32. Villani, D, Sorgente, A, Iannello, P, and Antonietti, A. The role of spirituality and religiosity in subjective well-being of individuals with different religious status. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:1525–5. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01525

33. Yeshe, L, and Rinpoche, LZ. Wisdom energy: Basic Buddhist teachings. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications (1976).

34. Goldstein, J, and Kornfield, J. Seeking the heart of wisdom: The path of insight meditation. Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications, Inc (1987).

35. Sternberg, R, and Glück, J. Wisdom: The psychology of wise thoughts, words, and deeds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2021).

36. Phan, HP, Chen, S-C, Ngu, BH, and Hsu, C-S. Advancing the study of life and death education: theoretical framework and research inquiries for further development. Front Psychol. (2023) 14:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1212223

37. Metzner, R. The Buddhist six-worlds model of consciousness and reality. J Transpers Psychol. (1996) 28:155–66.

39. Fredrickson, BL. Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and well-being. Prev Treat. (2000) 3:31. doi: 10.1037/1522-3736.3.1.31a

40. Gillham, J, and Reivich, K. Cultivating optimism in childhood and adolescence. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci. (2004) 591:146–63. doi: 10.1177/0002716203260095

41. Reddy, JSK, and Roy, S. The role of one’s motive in meditation practices and prosociality. Front Hum Neurosci. (2019) 13:48. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2019.00048

44. Zeidan, F, Johnson, SK, Diamond, BJ, David, Z, and Goolkasian, P. Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: evidence of brief mental training. Conscious Cogn. (2010) 19:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014

47. Xiao, Q, Yue, C, He, W, and Yu, J-Y. The mindful self: a mindfulness-enlightened self-view [hypothesis and theory]. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:Article 1752. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01752

48. Son, ND, and Nga, GB. Death and dying: belief, fear and ritual in Vietnamese culture In: H Selin and RM Rakoff, editors. Death across cultures: Death and dying in non-Western cultures. Berlin: Springer International Publishing (2019). 75–82.

49. Willis, J. Dying in country: implications of culture in the delivery of palliative care in indigenous Australian communities. Anthropol Med. (1999) 6:423–35. doi: 10.1080/13648470.1999.9964597

50. Bollig, G, and Bauer, EH. Last aid courses as measure for public palliative care education for adults and children - a narrative review. Ann Palliative Med. (2021) 10:8242–53. doi: 10.21037/apm-21-762

51. Bollig, G, Knopf, B, Meyer, S, and Schmidt, M. A new way of learning end-of-life care and providing public palliative care education in times of the COVID-19 pandemic – online last aid courses. Arch Health Sci. (2020) 4:1–2. doi: 10.31829/2641-7456/ahs2020-4(1)-123

52. Bollig, G, and Rosenberg, JP. Public health palliative care and public palliative care education. Healthcare. (2023) 11:745. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11050745

53. Li, WW, Chhabra, J, and Singh, S. Palliative care education and its effectiveness: a systematic review. Public Health. (2021) 194:96–108. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.033

54. Weissman, DE, and Blust, L. Education in palliative care. Clin Geriatr Med. (2005) 21:165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2004.08.004

56. Camacho, D, Pérez, N, and Gordillo, F. Guilt and bereavement: effect of the cause of death, and measuring instruments. Illn Crisis Loss. (2020) 28:3–17. doi: 10.1177/1054137316686688

57. Harrop, E, Scott, H, Sivell, S, Seddon, K, Fitzgibbon, J, Morgan, F, et al. Coping and wellbeing in bereavement: two core outcomes for evaluating bereavement support in palliative care. BMC Palliat Care. (2020) 19:29–15. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-0532-4

58. Granero-Gallegos, A, Phan, HP, and Ngu, BH. Advancing the study of levels of best practice pre-service teacher education students from Spain: associations with both positive and negative achievement-related experiences. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0287916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0287916

59. Phan, HP, Ngu, BH, Chen, S-C, Wu, L, Shi, S-Y, Shih, J-H, et al. Advancing the study of positive psychology: the use of a multifaceted structure of mindfulness for development. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:1–19. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01602

60. Phan, HP, Ngu, BH, Wang, H-W, Shih, J-H, Shi, S-Y, and Lin, R-Y. Achieving optimal best practice: an inquiry into its nature and characteristics. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0215732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215732

63. Schneiderman, L. Psychological notes on the nature of mystical experience. J Sci Study Relig. (1967) 6:91–100. doi: 10.2307/1384201

64. Lama, D, and Chodron, T. Samsara, nirvana, and Buddha nature. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications (2019).

65. Park, M-SK. Samsara: When, where and in what form shall we meet again? Sydney: University of Sydney (2014).

66. Barua, A. The reality and the verifiability of reincarnation. Religions. (2017) 8:1–13. doi: 10.3390/rel8090162

67. Nagaraj, A, Nanjegowda, RB, and Purushothama, S. The mystery of reincarnation. Indian J Psychiatry. (2013) 55:171–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105519

69. Prude, A. Death in Tibetan Buddhism In: TD Knepper, L Bregman, and M Gottschalk, editors. Death and dying: An exercise in comparative philosophy of religion, vol. 2. Berlin: Springer International Publishing (2019). 125–42.

70. MacAlpine, AG. Tonga religious beliefs and customs. J R Afr Soc. (1906) 5:257–68. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a094825

71. Clark, KJ, and Palmer, CT. Ancestor worship In: V Weekes-Shackelford, TK Shackelford, and VA Weekes-Shackelford, editors. Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science. New York: Springer International Publishing (2016). 1–3.

72. Steadman, LB, Palmer, CT, and Tilley, CF. The universality of ancestor worship. Ethnology. (1996) 35:63–76. doi: 10.2307/3774025

73. Townsend, N. Ancestor worship and social structure: A review of recent analyses. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University (1969).

74. Lakos, W. Chinese ancestor worship: A practice and ritual oriented approach to understanding Chinese culture. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing (2010).

75. Brown, JS, Collins, A, and Duguid, P. Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educ Res. (1989) 18:32–42. doi: 10.3102/0013189X018001032

76. Lave, J, and Wenger, E. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1991).

77. Bronfenbrenner, U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (1979).

78. Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological systems theory In: R Vasta, editor. Annals of child development: Theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues, vol. 6. Stamford, CT: JAI Press (1989). 187–251.

79. Piaget, J. The child's construction of reality (M. Cook, trans.). London: Routledge & Paul (1955).

81. Phan, H, Ngu, B, Hsu, C-S, and Chen, S-C. The life + death education framework: Proposition of a ‘Universal’ framework for implementation. Omega: J. Death Dying. (2024) 26:302228241295786. doi: 10.1177/00302228241295786

82. New South Wales Commission for Children and Young People. Ask the children: Overview of children's understanding of wellbeing. Surrey Hills, NSW: NSWCCYP (2007).

83. NSW Department of Education and Communities. The well-being framework for schools (NSW Department of Education and Communities, trans.). Sydney, NSW: NSW Department of Education and Communities (2015).

84. Soutter, AK, O'Steen, B, and Gilmore, A. The student well-being model: a conceptual framework for the development of student well-being indicators. Int J Adolesc Youth. (2014) 19:496–520. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2012.754362

85. ACU and Erebus International. Scoping study into approaches to student wellbeing: Literature review. Report to the Department of Education, employment and workplace relations. Fitzroy: Australian Catholic University (2008).

86. Butler, N, Quigg, Z, Bates, R, Jones, L, Ashworth, E, Gowland, S, et al. The contributing role of family, school, and peer supportive relationships in protecting the mental wellbeing of children and adolescents. Sch Ment Heal. (2022) 14:776–88. doi: 10.1007/s12310-022-09502-9

87. Kern, ML, Waters, LE, Adler, A, and White, M. Assessing employee wellbeing in schools using a multifaceted approach: associations with physical health, life satisfaction, and professional thriving. Psychology. (2014) 5:500–13. doi: 10.4236/psych.2014.56060

88. Vasquez-Salgado, Y, Greenfield, PM, and Burgos-Cienfuegos, R. Exploring home-school value conflicts: implications for academic achievement and well-being among Latino first-generation college students. J Adolesc Res. (2015) 30:271–305. doi: 10.1177/0743558414561297

91. Sternberg, RJ. Beyond IQ: A triarchic theory of intelligence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1985).

92. Sternberg, RJ, and Grigorenko, EL. Successful intelligence in the classroom. Theory Pract. (2004) 43:274–80. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4304_5

93. Pollard, EL, and Lee, PD. Child well-being: a systematic review of the literature. Soc Indic Res. (2003) 61:59–78. doi: 10.1023/A:1021284215801

95. Markus, H, and Nurius, P. Possible selves. Am Psychol. (1986) 41:954–69. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954

96. Oyserman, D, Elmore, K, and Smith, G. Self, self-concept, and identity In: MR Leary and JP Tangney, editors. Handbook of self and identity. New York, NY: The Guilford Press (2012). 69–102.

97. Thagard, P. The self as a system of multilevel interacting mechanisms. Philos Psychol. (2014) 27:145–63. doi: 10.1080/09515089.2012.725715

98. de Brito Sena, MA, Damiano, RF, Lucchetti, G, and Peres, MFP. Defining spirituality in healthcare: a systematic review and conceptual framework [systematic review]. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.756080

99. Lancaster, BL, and Linders, EH. Spirituality and transpersonalism In: L Zsolnai and B Flanagan, editors. The Routledge international handbook of spirituality in society and the professions. 1st ed. London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group (2019). 40–7.

100. Llanos, LF, and Martínez Verduzco, L. From self-transcendence to collective transcendence: in search of the order of hierarchies in Maslow’s transcendence [original research]. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.787591

101. Ruschmann, E. Transcending towards transcendence. Implicit Religion. (2011) 14:421–32. doi: 10.1558/imre.v14i4.421

102. Seligman, M, and Csíkszentmihályi, M. Positive psychology: an introduction. Am Psychol. (2000) 55:5–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5

Keywords: Life + Death Education Framework, life care, life enhancement, self well-being, positive psychological personal, life education, death education

Citation: Phan HP, Ngu BH, Hsu C-S and Chen S-C (2024) Advancement of life and death education research: recommending implementation of the Life + Death Education Framework for teaching and research purposes. Front. Public Health. 12:1440750. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1440750

Received: 30 May 2024; Accepted: 23 October 2024;

Published: 26 November 2024.

Edited by:

Abdolvahab Samavi, University of Hormozgan, IranReviewed by:

Toshiko Kikkawa, Keio University, JapanCopyright © 2024 Phan, Ngu, Hsu and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huy P. Phan, aHBoYW4yQHVuZS5lZHUuYXU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.