- 1School of Public Health, Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel

- 2Population Health Science Department, College of Population Health Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 3Department of Surgery, Imperial College, London, United Kingdom

- 4Research Institute for Health Law and Science, School of Medicine, Sigmund Freud University, Vienna, Austria

- 5Department of Public Health, Ashkelon Academic College, Ashkelon, Israel

- 6Department of International Health, Care and Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), FHML, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands

- 7Department of Health Policy Management, Institute of Public Health, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland

- 8Department of Health Policy and Management, Guilford Glazer Faculty of Business and Management and Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, Israel

- 9The Israeli Association of Public Health Physicians (IPAPH), Israeli Medical Association, Ramat-Gan, Israel

- 10Department of Health Promotion and e-Health, Faculty of Health of Science, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Kraków, Poland

- 11School of Public Health, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

- 12Hebrew University-Hadassah, Braun School of Public Health and Community Medicine, Jerusalem, Israel

- 13The Swedish Red Cross University Stockholm, Huddinge, Sweden

Introduction: We examined the perceptions of the Master of Public Health (MPH) degree graduates regarding their personal competencies, job performance and professional development using a mixed method, explanatory sequential design.

Methods: A cross-sectional, self-administered questionnaire of the Haifa School of Public Health alumni who graduated between 2005 and 2022 was disseminated to 849 graduates between March and June 2022, from which 127 responded (response rate: 14.90%). This was followed by 24 in-depth interviews with alumni from the same sample (conducted between November 2022 and March 2023).

Results: The sample included 74.8% of females with a mean age of 40.7 years, 35% of alumni agreed that the MPH degree helped them attain a promotion in their present position (in rank or salary), and 63.8% felt that the degree helped them improve their job performance and contribute to their current workplace. Most (80.3%) alumni reported not changing jobs after graduation. The interview themes revealed that the MPH contributed to their personal and professional lives, provided them with a holistic view of public health and health systems, and improved their in-depth scientific skills. The main reported barriers to professional development included missing core competencies, low salaries, and a lack of information regarding suitable jobs. Surprisingly, an MPH was not a requirement for some public health sector jobs. Alumni reported that the MPH degree contributed to improving many graduates’ careers and satisfaction levels and to build their leadership competencies in public health.

Discussion: There seems to be a lack of coordination between the academic curriculum and the jobs available for alumni, hindering better alumni professional development. Regular discussions, information sharing, and curriculum refinements between MPH program leaders and health sector leaders might help address many of the concerns of MPH degree graduates.

1 Introduction

The central roles of the Public Health (PH) services in response to 21st century challenges have highlighted the need to maintain a highly effective PH workforce (PHW). The PHW across the world has had to react and adjust swiftly to existential challenges such as the pandemic, wars, and natural disasters, in addition to performing ongoing PH responsibilities (e.g., monitoring of infectious and chronic diseases, routine childhood vaccine programs) and controlling other emerging health threats (1). Yet, not enough is known in Israel and many other places about whether the outcomes and impacts of a Master of Public Health (MPH) degree training prepares graduates with the right competencies needed for the PHW and helps graduates secure fulfilling and effective jobs. The capacity-building in higher education project “Sharing European Educational Experience in Public Health for Israel” (SEEEPHI) was established to transfer knowledge and best practices from European Union Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to countries and HEIs outside the EU. The project was funded through ERASMUS+, with The Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region (ASPHER) as the coordinating organization (2).

A Master of Public Health (MPH) degree is expected to teach the essential competencies needed for graduates to perform their PHW tasks (3–5). The World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe and ASPHER, define ten competency categories that focus on PH content and contexts, relations and interactions, performance, and achievement (6). The WHO-ASPHER Competency Framework for the Public Health Workforce in the European Region (CFPHW) provides standardization and consistent definitions for the competencies required by PH professionals. Most Schools of Public Health incorporate these into their study curricula. However, it is not clear how the MPH effectively prepares their graduates for lifelong satisfying jobs in the PHW and how the MPH sub-specializations address the public health needs of the 21st century. This is important for low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) and high-income countries alike (7), and relates to the general debate on the relevance of higher education to society and specific professions and jobs (8).

Studies have shown that despite extensive efforts to define PH professional competencies in academic programs, PH graduates do not possess the real-world needed competencies as measured by the Essential Public Health Operations (9, 10). Measuring the outcomes and impacts of educational programs is fraught with methodological difficulties (11, 12). Zwanikken et al. (13) suggested that the impact of an MPH program can be conceptualized as “impact in the workplace” and “impact on society.” They surveyed graduates of MPH programs in six countries and reported that the MPH programs contributed to the graduates’ use of competencies especially in regards to the workplace and had less impact on society (7). They also found clear differences between MPH programs. The same authors in a follow-up qualitative study found considerable impacts on the workplace at the national level in two countries (13). Additional studies have looked at other types of related programs, such as Belkowitz et al. (14) who surveyed recent graduates of a four-year MD/MPH program and found many had fulfilling leadership roles in their careers, contributed to research and about one-third worked in public health during their residency.

This study aimed to identify and analyze MPH alumni perceptions of the impacts that their Master of Public Health degree had on graduates’ careers, the application of competencies acquired in the MPH degree and their workplace.

2 Methods

We conducted an exploratory prospective, mixed methods study as part of a multinational Erasmus Plus Capacity Building European Union grant in Higher Education entitled “Sharing European Educational Experience in Public Health for Israel (SEEEPHI): harmonization, employability, leadership, and outreach” (15).

2.1 Study design and population

This is a cross-sectional, mixed-methods explanatory sequential design study of the University of Haifa graduates. The Haifa School of Public Health is one of four graduate Schools of Public Health in Israel. In addition, there is one undergraduate program at Ashkelon College. The Haifa School of Public Health was founded in 2003 and has nine different sub-specializations, with approximately 120 new students each year in the MPH program and about seven new PhD students. The students are mainly health professionals, including nurses, physicians, nutritionists, and others. The students are mainly in their 30’s and are a few years after their undergraduate studies, therefore have a few years of experience as healthcare workers, a minority are not healthcare workers. In their undergraduate studies the vast majority of MPH students are directed at acquiring a healthcare profession, such as nursing, medicine, or nutrition, and they are not exposed to public health.

The healthcare professions the alumni acquired in their undergraduate studies are geared towards individual patient care and in contrast, the MPH studies provide a new outlook on health issues, looking at the community as a whole. The MPH studies at the University of Haifa are intended mainly for professionals in mid-career, working full-time in the healthcare system. The large majority of students study one day a week and the rest of the time are employed. In addition to the holistic public health perspective, alumni obtained skills and competencies they did not have before. The specific competencies obtained depended on the sub-specializations they chose. For example, in the ‘Nutrition, Health, and Behavior,’ sub-specialization, the curriculum contains courses related to nutritional therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, and in the ‘Health Promotion’ sub-specialization, the students are planned to acquire competencies to develop and promote health interventions. The students decide to study MPH and which specialization to choose without any national (or other) directing or funding. There is no governmental or other support for MPH studies.

This study included a quantitative survey, conducted between March and June 2022, followed by qualitative interviews among a sub-sample, conducted between November 2022 and March 2023, of the MPH alumni who graduated from the Masters of Public Health degree program between the years 2005 and 2022.

2.2 Data collection

After obtaining ethics approval to contact alumni, the School of Public Health at the University of Haifa’s secretary sent an email in March 2022 to all graduates from 2005 to 2022. A reminder was sent in April 2022, and the survey closed in June 2022. Participation in the survey was voluntary, responses were anonymous, and participants had the option to withdraw at any stage. The questionnaire was disseminated to 849 graduates between March and June 2022, of which 127 responded (response rate: 14.90%).

At the end of the questionnaire, the alumni were invited to participate in an in-depth interview. Alumni agreeing to an in-depth interview completed a separate form providing their contact details and consent. A follow up letter was sent to those who consented and an explanation was provided of the goals of the qualitative study and an explanation about recording their consent at the beginning of the interview. In addition, direct contact was made with alumni who did not answer the questionnaire to better represent all sub-specialties and genders.

The qualitative data collection was performed until complete saturation was achieved. The in-depth interviews were conducted by a sole interviewer (YD), conducted remotely using Zoom video software, and lasted 30–40 min on average. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, with the recordings subsequently deleted to preserve the anonymity of participants. The video recording was deleted subsequent to the interview.

The core study group (OBE, YD, DIW, MPR, SZS) developed the survey and the interview protocol. The survey was pretested with four alumni and revised based on comments received. The questionnaires underwent face, content and consensual validity by the SEEEPHI participants. The survey was hosted on Google Forms and contained 16 open and multiple-choice questions. All questionnaires were anonymously collected and analyzed. The full questionnaires are available in Supplementary material S1.

The in-depth interview protocol was developed based on the survey’s findings. A semi-structured interview protocol including nine open-ended questions to elicit in-depth information regarding alumni’s feelings towards their MPH degree and its impact on their work, profession and satisfaction. The interviewer (YD), highly experienced in conducting interviews, prompted the interviewee with probing questions to further investigate their opinions and feelings.

2.3 Data analysis

The quantitative data was analyzed using Microsoft Excel software. Descriptive statistics included demographic data and frequencies of answers to the questions (i.e., the number of participants, their mean age, gender, and year of graduation).

The interviews were transcribed and analyzed by two researchers (YD and DIW) who performed a thematic analysis of the transcribed data. The analyses included both a deductive approach based on categories in the interview guide and an inductive approach that developed new categories and themes throughout the analysis process (16) A review of the interview scripts served as the basis for a preliminary category structure, followed by axial coding to identify relationships and patterns for theme development.

Furthermore, an expansion methodology was employed to address a central theme not covered in the questionnaire and that emerged prominently during the interviews, enriching the study’s findings with a broader perspective derived from the qualitative data analysis (17). Integration of the qualitative and quantitative data analyses was based on weaving narrative, joint display, and an integrated discussion by the research team (18). The qualitative data offered more detailed descriptions of the alumni’s experiences, while the quantitative data allowed for general and representative findings (19).

2.4 Ethics

The University of Haifa Ethics Committee granted ethical approval for the study, including the interview guide and participants’ information sheets, and waived the requirement of signed informed consent from the participants (approval #060/22).

3 Results

3.1 Demographics of respondents

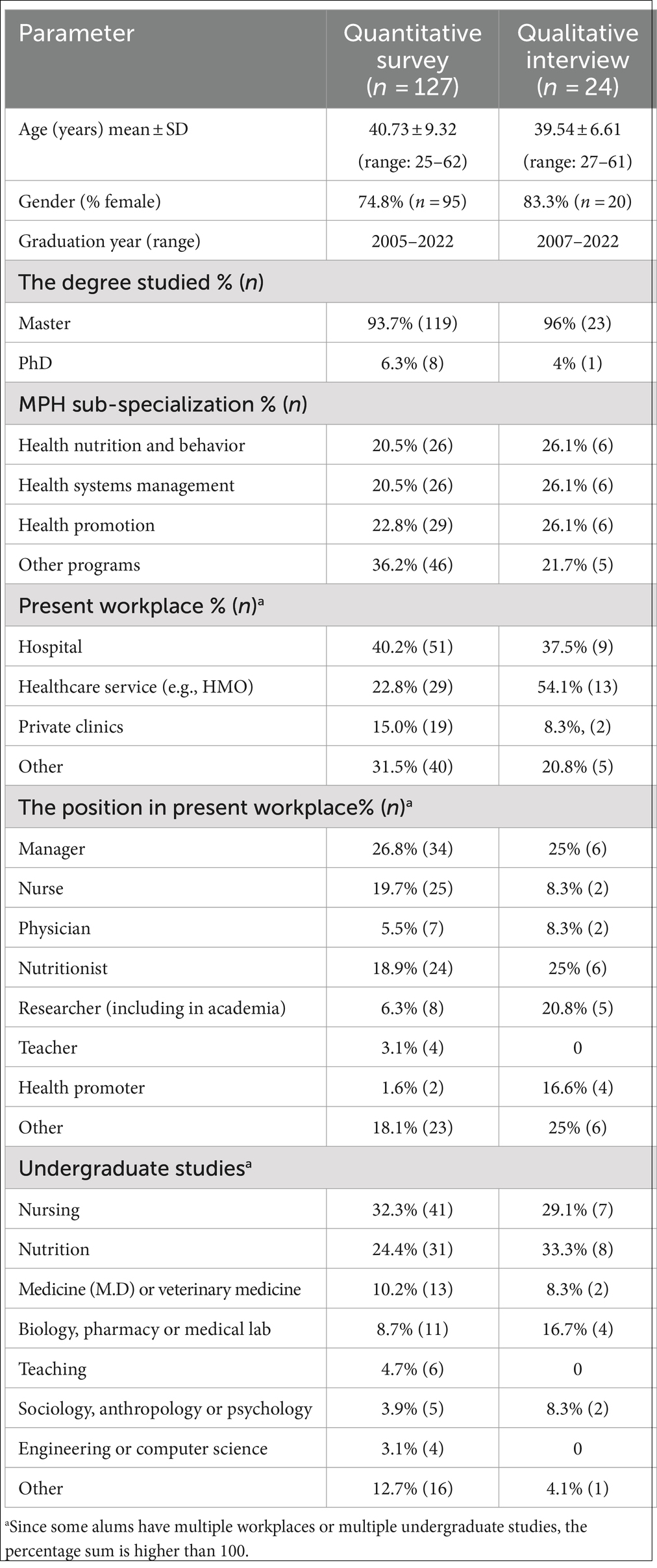

The survey was sent to 849 graduating alumni between 2005 and 2022 from the graduate studies at the School of Public Health, University of Haifa. Of those, 127 alumni (14.9% response rate) answered the questionnaire. The mean age of the respondents was 40.73 ± 9.3 (range: 25–62), and 74.8% were women (n = 95) which is representative of the school’s student body having female majority, with an average percentage of women in the past 10 years of 78%. Most, 93.7% (n = 119), of the respondents graduated with a master’s degree, and 6.3% (n = 8) graduated with a PhD degree. Regarding the PH sub-specializations, 20.5% graduated from the Health Nutrition and Behavior program, 20.5% from the Health Systems Management program, and 59.0% from Public Health (i.e., epidemiology, health promotion, health system administration, etc.). This represents the distribution of students between the sub-specializations in the school. A total of 24 alumni (20 women and 4 men) agreed to be interviewed using in-depth interviews. One participant graduated with a PhD, and 23 graduated with an MPH; of those, 15 completed research projects and submitted a thesis to earn their degree. The remaining participants did not do a research thesis for their degree. Regarding the PH sub-specialization, 26.1% studied in the Health Nutrition and Behavior program, 26.1% in the Health Systems Management program, and 47.8% graduated from the other sub-specializations (Table 1).

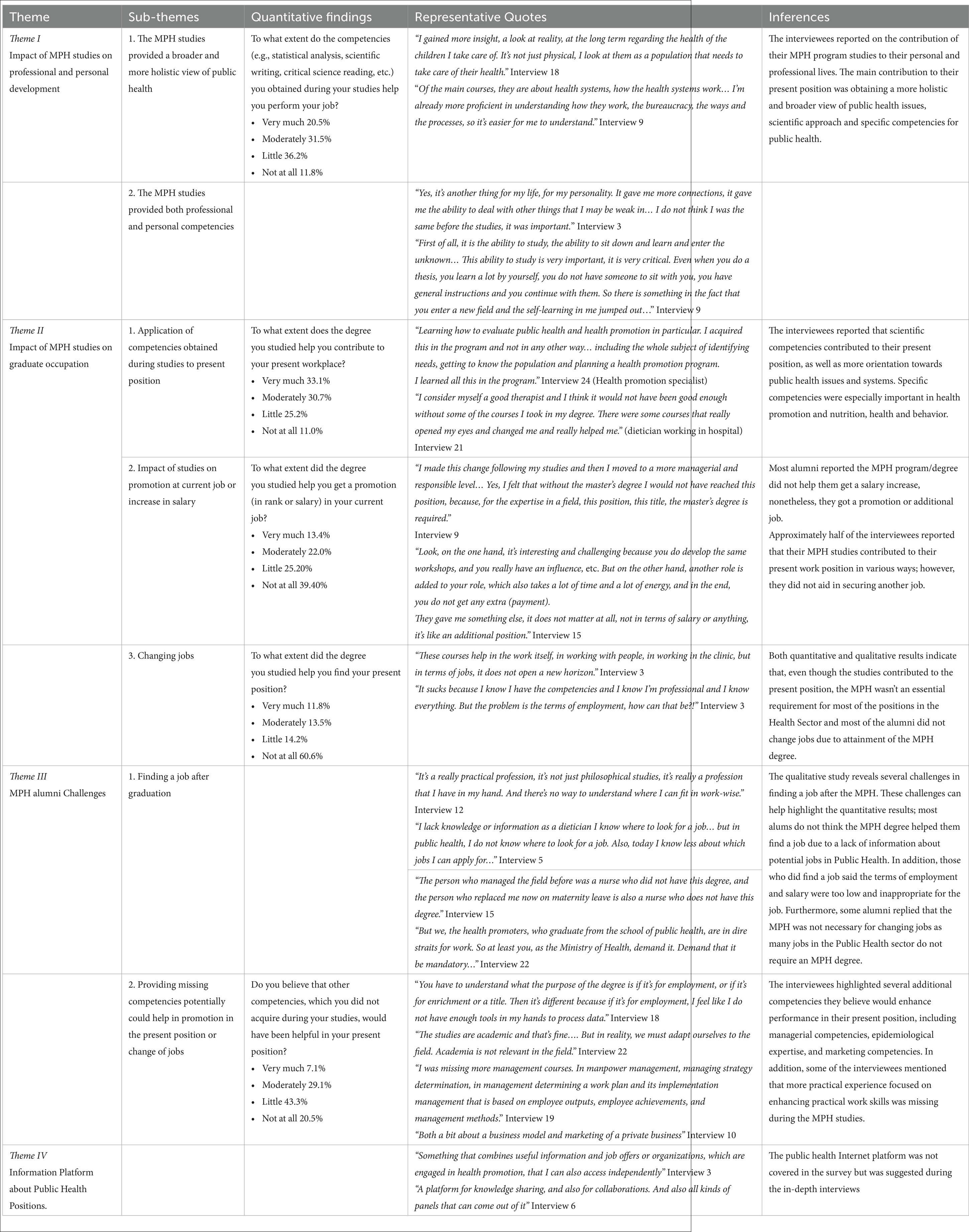

The data analysis resulted in four main themes and seven sub-themes that emerged from the interviews: (I) Impact of MPH studies on professional and personal development, (II) Impact of MPH studies on occupation (present job, promotion, increase in salary, and changing jobs), (III) Challenges and difficulties; and, (IV) Information Platform about Public Health Positions. Table 2 illustrates the integrated analysis of the quantitative and qualitative data, including the themes, sub-themes, and representative quotes related to the impacts of the MPH degrees.

3.2 Theme I: impact of MPH studies on professional and personal development

Alumni were asked how the MPH program contributed to their personal and professional lives. Around 64% reported that the degree helped contribute to their job and current workplace very much or moderately, and 52% reported that they used the competencies obtained in their studies in their present position very much or moderately. A more in-depth understanding was obtained from the interviews and suggested that the MPH training provided a broad and holistic view of health and specific competencies that graduates could utilize in their workplace. The holistic view included a broader view of health, public health and health systems in Israel and around the world, as well as a broader view of aspects of public health, such as financial, political, organizational, and more. The competencies included managerial and scientific competencies.

3.3 Theme II: impact of MPH studies on graduate occupation

The sub-themes included three professional outcomes related to graduation from the MPH program, (a) impact on current job, (b) promotion or increase in salary within the present position, and (c) changing jobs.

The first sub-theme was the application of competencies obtained during studies to the current position. The competencies obtained during the alumni MPH studies provided the ability to approach the graduate’s work more scientifically. The competencies alumni acquired included mainly statistical and scientific tools. In addition, they acquired competencies enabling them to promote the health of the population and competencies to enhance nutritional therapy. The latter was relevant mainly for Health Promotion and Health Nutrition and Behavior sub-specializations graduates. In addition, alumni reported that the studies strengthened their abilities to better address various challenges, such as managing task loads, problem-solving, and overcoming personal and professional challenges. Furthermore, alumni reported that their scientific competencies, such as how to approach research, analytical reading of scientific articles, and seeking reliable data, improved as a result of their studies.

Most respondents did not change their jobs after graduation (80.8%). Therefore the second sub-theme suggests an impact of the studies on promotion or increase in salary at the current job. The quantitative data suggests that 36% received an increase in salary or promotion within their present position. The interviews corroborated this finding, and some said the promotion did not bring with it a salary raise but did increase their job load as additional tasks were given to them.

The third sub-theme included a change of jobs due to MPH studies. Those alumni who did change jobs or positions (19.2%), reported that the change happened due to specific competencies obtained during their MPH studies; these were required for some jobs, such as managerial positions, epidemiology, and health promotion. Exposure to conferences and academic staff helped them find relevant new jobs they were not aware of before; this networking played a major role for those who did find new jobs.

Alumni who did not change jobs or positions reported that many public health jobs did not require an MPH degree even though they were public health positions. Therefore, they were not in a better position to earn these jobs after graduation. This was a recurring complaint of many of the alumni.

3.4 Theme III: MPH alumni challenges

The interviewees reported significant challenges in applying the MPH studies and competencies in their careers. They reported challenges in how to advance their careers due to a lack of knowledge and information about where to find a job, what the options were in the public health sector, and where are the available positions. The differences in salary scales between public health and other healthcare professions are seen as not favorable to public health professionals, and therefore, alumni have no incentive to change jobs and move to public health jobs, quite the opposite. This causes disappointment for those with expectations for professional advancement at the end of their studies.

A second major challenge was the missing competencies, with 36.2% reporting on competencies they felt (very much or moderately) were missing from their studies that could have helped them in their current job and in finding a new job. The interviewees highlighted the competencies that were missing including managerial, epidemiological, and marketing competencies as well as practical experience in managing PH challenges.

3.5 Theme IV: information platform about public health positions

The study is part of the EU SEEEPHI project wherein one of the goals was to develop a platform to share information about public health positions. Interestingly, some interviewees suggested such a network without prompting, and the responses were recorded. This aligns with alumni suggestions for how best to overcome the hurdle of insufficient information regarding available jobs. All agreed that using Internet social networking platforms could help expose students and graduates to various jobs and positions in the public health arena. In addition, they suggested having public health employment fairs organized by the school or public health organizations. When asked about an internet platform to support alumni job placements, it was very positively accepted, and they stated that it could be very helpful and could be used for additional public health issues.

The public health designed Internet platform was not covered in the survey but was addressed during the interviews. The interviewees shared their perspectives on the required content of the platform and mentioned key topics such as employment, networking, collaboration, public health updates, innovations, conferences, and training opportunities. In addition, they highlighted the potential advantages of this platform, including posting job offers, transparent employment terms, employer profiles, and CV uploads for graduates to facilitate direct job offers. The platform will also enable sharing public health updates, studies, seminars, and conferences. It will showcase successful projects, provide valuable links to public health organizations, and allow organizations to articulate their roles and visions. In addition, the platform could provide access to scientific resources and data, promote information sharing about ongoing or planned studies, and facilitate research collaborations. Additionally, it could foster networking and cooperation between public health professionals, enable consultations across disciplines, and strengthen the connections between universities and graduates.

4 Discussion

This mixed methods study looked at MPH alumni in Israel to understand how the graduate degree could help to prepare alumni for and improve their professional career performance. Academic studies aim to broaden knowledge and skills and increase cognitive and practical abilities that can then be applied in the graduates’ professional lives, generally (20) and specifically in public health (21).

Our findings suggest that the MPH degree studies provide a holistic public health perspective that students did not acquire in their undergraduate studies. It should be noted that undergraduate studies for the vast majority of students embarking on an MPH program are directed at acquiring a healthcare profession, such as nursing, medicine, or nutrition, and they have limited exposure to public health in their undergraduate studies. Other studies also suggest that academic studies of public health enhance the student’s roles in areas such as public health policy analysis, planning, implementation and evaluation, leadership, and research (22) and acquiring specific competencies for public health (7).

However, many of the respondents did not feel their MPH studies helped them improve their job position or income, which led to disappointment. A minority of respondents reported major changes in their employment. The study suggests three major outcomes, including improvement in their job performance, change in employment for the better and increases in salary or position. Two-thirds of alumni reported improvements in their current job performance, however, less than 20% reported changing jobs as a result of their studies. Over 60% reported little or no increases in salary or position. It must be noted that the MPH studies were intended to help students improve their ability to use the skills that were taught and not intended to help increase their salary or change jobs, even though this often was the expectation of many students.

In a review of the subject, Krasna et al. found that few studies focused on employment outcomes as we did in this study (21). Buunaaisie et al. (22) did look at employment in an international program in England and found that 63% of graduates were employed 1 year after graduation. However, our student characteristic is different as most of them are employed before joining the program, but only a third report improving their employment.

A few barriers that may prevent improving alumni in the workforce were identified. A major barrier is that salaries in the public health workforce are low compared to salaries of workers in healthcare roles. The public health domain does not have a strong union, successful in demanding increases in salaries, and therefore transferring to a public health position frequently does not come with a salary increase, even if it is a better position. We did not find this barrier reported in other studies, this may be that in other countries public health jobs are paid well or that the other studies interviewed graduates and not alumni.

As an additional barrier, some positions in public health did not require the MPH degree as a prerequisite, so there is little incentive to transfer to a public health position especially for low level positions. In a study in Germany, Arnold et al. (23) reported that they had considerable difficulties in attracting well-qualified personnel to the public health services and identified barriers to increasing the attractiveness of public health as a career.

Our study demonstrated that less than half the alumni saw improvements in their position or salary after graduation, however, we need to consider the large range of follow-up time since graduation in our sample. These results suggest our school needs to provide students with better information regarding positions available for MPH graduates, as the interviewees suggested in the in-depth interviews (24, 25).

Previous studies looked at MPH alumni’s opinions regarding their studies but less so regarding their work performance as a result of their studies. Le et al. (26) interviewed 187 graduates in Hanoi, which reported high rates of developing relevant skills and satisfaction, however, they felt the MPH emphasized research methods at the expense of management and operational competencies.

There is a great need to better understand how best to enhance the compatibility between public health training program competencies and the implementation of competencies required by employers to address emerging public health needs in Israel (9). Therefore Baskin et al. interviewed 49 PH managers in an attempt to understand this. The authors found deficiencies in all categories of PH competencies. Employers reported they need better-trained graduates and that the PH graduates were deficient in essential competencies, concluding that there is an urgent need for PHW to have the ability to deal with increasingly complex and diversified jobs (15). In this study alumni reported missing competencies, such as managerial, epidemiological, and marketing competencies. These gaps between curricula and work needs could be due to the changing public health landscape and newer developments in technology and the workforce requiring a combination of multiple skills from several disciplines.

Other studies also looked at deficiencies in the MPH programs, in Canadian MPH programs, there also seems to be a lack of courses addressing core competencies, especially diversity and inclusiveness communication and leadership (27). As a result of social and economic changes, the Boston University public health department redesigned the program (28). They aimed to “provide students with integrated foundational knowledge; specialized skills and training in key areas sought” with the aim to close gaps between competencies learned in the program and those needed by employees.

Closing these mentioned gaps in competencies of graduates in a changing and complex public health landscape may help promote finding jobs and improve job position or salary post MPH graduation. This may strengthen the argument of the importance and necessity of MPH graduates in the health system.

There is room for revamping the public health curricula in Israel, both adding competencies alumni reported missing and building an accessible platform with information regarding available PH jobs.

4.1 Limitations

This study is exploratory and has several limitations. First, it was performed in only one school of public health in Israel, and therefore may not represent the total alumni of public health schools in Israel, even though we are not aware of any differences between the schools except for their geographical location. This study can serve as a case study focusing on a single school, similar to many other studies on this subject, as pointed out in a scoping review (21). It can help build a more complete picture of gaps and opportunities in public health education. As part of the study is qualitative the importance of the representativeness is less of a limitation as the information collected gives an in-depth view of the subject.

Second, the sample size was not large and the response rate was low, therefore the level of representativeness is not clear. However, we did approach the total population of learners relevant to the study’s goals and made efforts to get a reasonably representative sample of our alumni at least by gender, age and time from graduation. As this is a mixed methods approach, the addition of the qualitative interviews provides an in-depth view of the outcomes and validates the quantitative results, somewhat overcoming the partial representativeness of the sample by extracting themes from the alumni. Explanations for the low response rate may be that there is no ongoing email follow-up with alumni due to restrictions imposed by the Israeli Communications Law (commonly known as the “Spam Law”), which sets strict regulations on sending electronic communications. That said, response rates for email surveys targeting healthcare professional alumni, tend to be low (29), perhaps influenced by the increasing volume of email communications healthcare professionals receive, their busy schedules, and the lack of personal incentives.

Third, the study results reflect the Israeli health and higher education systems, which may not be generalized to other countries with their distinct public health delivery and training systems, comprising unique organizational characteristics, barriers to job hires, and different clinical and political settings. It is unclear to what degree this study can be generalized to other countries even though the curriculum of the Haifa University Public Health School adheres to the WHO-ASPHER Competency Framework (6). However, the Israeli academic system does not differ significantly from systems in Europe and America, therefore we think the results can contribute to understanding the place of the MPH studies for the workforce and the PH services.

Fourth, to address potential validity threats, we made all efforts to ensure methodological rigor by using a standardized codebook, meeting frequently, sharing and comparing our results, and performing a pilot analysis.

Fifth, the quotes chosen for Table 2 were translated from Hebrew to English and back-translated to ensure their correct meaning.

Finally, we did not measure objective occupational measures like salaries of graduates versus undergraduates or the impacts that alumni had on society, which can be tested in future studies.

Further studies are needed to identify specific groups with specific barriers and problems and follow up these alumni and see how their career playouts in the long run. In addition, there is also a need to compare and correlate the results with opinions of the employers that employ the graduates to verify the significance of the opinions expressed in this study. This would serve as a validation of the study. This calls for further studies not only among alumni but also among employees and employers in the public health services and curative healthcare services. Also, looking at how the public health services changed over time regarding the needs required from graduates could teach us of trends in the public health workforce.

5 Conclusion

Public health graduate studies at the University of Haifa School of Public Health in Israel are successful in providing a holistic view of health and the healthcare system and basic competencies for the workforce. However, alumni reported less satisfaction in enhancing job opportunities. There is a need to align the curricula with the needs of the PHW and increase the ability of alumni to utilize their acquired skills and competencies more effectively. The study also suggests there is a need to develop pathways between the academy and field to translate graduate studies into occupational promotion and economic revenue. Future studies are needed to evaluate and enhance MPH degree learning outcomes and create a better-prepared and resilient workforce.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Haifa Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Alumni agreeing to an in-depth interview completed a separate form providing their contact details and consent. Then another letter was sent to those who consented explaining the goals of the qualitative study and an explanation about recording their consent at the beginning of the interview.

Author contributions

OB-E: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. DI-W: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PB: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. OB: Writing – review & editing. KC: Writing – review & editing. KD: Writing – review & editing. ND: Writing – review & editing. SJ: Writing – review & editing. FM: Writing – review & editing. MM: Writing – review & editing. LO-E: Writing – review & editing. MP-R: Writing – review & editing. SZ-S: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The current study is part of a multinational Erasmus+ Capacity Building in Higher Education funded project-Sharing European Educational Experience in Public Health for Israel (SEEEPHI): harmonization, employability, leadership, and outreach. The project is financed by EU funds within the framework of the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union (Grant Agreement 618578-EPP-1-2020-1-BE-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP). Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the participants to the study and to thank all the other consortium members not on the author list.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1429474/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

PH, Public Health; PHW, Public Health Workforce; MPH, Master of Public Health.

References

1. Xing, C, and Zhang, R. COVID-19 in China: Responses, Challenges and Implications for the Health System. Healthcare (Basel). (2021) 9:82. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9010082

2. SEEEPHI. Sharing European Educational Experience in Public Health for Israel (SEEEPHI) (2024). Available at: https://www.seeephi.aspher.org/about.html (Accessed April 29, 2024)

3. Bashkin, O, Otok, R, Kapra, O, Czabanowska, K, Leighton, L, Dopelt, K, et al. Identifying the gaps between public health training and practice: a workforce competencies analysis. Eur J Pub Health. (2023) 33(Supplement_2), ckad160–1470. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckad160.1470

4. Dopelt, K, Shevach, I, Vardimon, OE, Czabanowska, K, De Nooijer, J, Otok, R, et al. Simulation as a key training method for inculcating public health leadership skills: a mixed methods study [Original Research]. Front Public Health. (2023) 11. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1202598

5. Gershuni, O, Orr, JM, Vogel, A, Park, K, Leider, JP, Resnick, BA, et al. A systematic review on professional regulation and credentialing of public health workforce. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:4101. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20054101

6. World Health Organization. WHO-ASPHER competency framework for the public health workforce in the European region (2020).

7. Zwanikken, PA, Huong, NT, Ying, XH, Alexander, L, Wadidi, MS, Magana-Valladares, L, et al. Outcome and impact of Master of Public Health programs across six countries: education for change. Hum Resour Health. (2014) 12:40. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-40

8. Walker, M., McLean, M., Dison, A., and Vaughan, R. Higher education and poverty reduction: The formation of public good professionals in universities. Unpublished paper. School of Education: University of Notthingham (2010).

9. Bjegovic-Mikanovic, V, Wenzel, H, De Leeuw, E, and Laaser, U. Schools of public health in Europe: common mission—different progress. J Public Health Emerg. (2021) 5:26. doi: 10.21037/jphe-21-4

10. Laaser, U, Bjegovic-Mikanovic, V, Vukovic, D, Wenzel, H, Otok, R, and Czabanowska, K. Education and training in public health: is there progress in the European region? Eur J Pub Health. (2020) 30:683–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckz210

11. Blömeke, S. The Challenges of Measurement in Higher Education: IEA’s Teacher Education and Development Study in Mathematics (TEDS-M) In: Modeling and measuring competencies in higher education. Brill| Schöningh: Brill (2013). 91–112.

12. Rotem, A, Zinovieff, MA, and Goubarev, A. A framework for evaluating the impact of the United Nations fellowship programmes. Hum Resour Health. (2010) 8:1–8.

13. Zwanikken, PA, Alexander, L, and Scherpbier, A. Impact of MPH programs: contributing to health system strengthening in low-and middle-income countries? Hum Resour Health. (2016) 14:52. doi: 10.1186/s12960-016-0150-7

14. Belkowitz, J, Payoute, S, Agarwal, G, Lichtstein, D, King, R, Shafazand, S, et al. Early career outcomes of a large four-year MD/MPH program: Results of a cross sectional survey of three cohorts of graduates. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0274721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274721

15. Bashkin, O, Dopelt, K, Mor, Z, Leighton, L, Otok, R, Duplaga, M, et al. The future public health workforce in a changing world: a conceptual framework for a European–Israeli knowledge transfer project. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:9265. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179265

16. Gioia, DA, Corley, KG, and Hamilton, AL. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ Res Methods. (2013) 16:15–31. doi: 10.1177/1094428112452151

17. Onwuegbuzie, AJ, and Collins, KM. A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. Qual Rep. (2007) 12:281–316.

18. Fetters, MD, Curry, LA, and Creswell, JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Serv Res. (2013) 48:2134–56. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117

19. Harrison, RL, Reilly, TM, and Creswell, JW. Methodological rigor in mixed methods: An application in management studies. J Mixed Methods Res. (2020) 14:473–95. doi: 10.1177/1558689819900585

20. Chan, RY. Understanding the purpose of higher education: an analysis of the economic and social benefits for completing a college degree. J Educ Policy Plann Admin. (2016) 6:1–40.

21. Krasna, H, Gershuni, O, Sherrer, K, and Czabanowska, K. Postgraduate employment outcomes of undergraduate and graduate public health students: a scoping review. Public Health Rep. (2021) 136:795–804. doi: 10.1177/0033354920976565

22. Buunaaisie, C, Manyara, A, Annett, H, Bird, E, Bray, I, Ige, J, et al. Employability and career experiences of international graduates of MSc Public Health: a mixed methods study. Public Health. (2018) 160:62–9. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.03.032

23. Arnold, L, Kellermann, L, Fischer, F, Gepp, S, Hommes, F, Jung, L, et al. What factors influence the interest in working in the public health service in Germany? Part I of the OeGD-Studisurvey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:11838. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191811838

24. Bashkin, O, Otok, R, Leighton, L, Czabanowska, K, Barach, P, Davidovitch, N, et al. Emerging lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic about the decisive competencies needed for the public health workforce: A qualitative study [Original Research]. Front Public Health. (2022) 10. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.990353

25. Sellers, K, Leider, JP, Harper, E, Castrucci, BC, Bharthapudi, K, Liss-Levinson, R, et al. The public health workforce interests and needs survey: the first national survey of state health agency employees. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2015) 21:S13–27. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000331

26. Le, LC, Bui, QT, Nguyen, HT, and Rotem, A. Alumni survey of masters of public health (MPH) training at the Hanoi School of Public Health. Hum Resour Health. (2007) 5:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-5-24

27. Apatu, E, Sinnott, W, Piggott, T, Butler-Jones, D, Anderson, LN, Alvarez, E, et al. Where are we now? A content analysis of Canadian Master of Public Health Course Descriptions and the Public Health Agency of Canada’s core competencies. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2021) 27:201–7. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001173

28. Sullivan, LM, Velez, A, Edouard, VB, and Galea, S. Realigning the master of public health (MPH) to meet the evolving needs of the workforce. Pedagogy Health Promot. (2018) 4:301–11. doi: 10.1177/2373379917746698

Keywords: Masters of Public Health, alumni, mixed methods, professional development, competencies, higher education

Citation: Baron-Epel O, Douvdevany Y, Ivancovsky-Wajcman D, Barach P, Bashkin O, Czabanowska K, Dopelt K, Davidovitch N, Jakubowski S, MacLeod F, Malowany M, Okenwa-Emegwa L, Peled-Raz M and Zelber-Sagi S (2024) Professional development: a mixed methods study of Masters of Public Health alumni. Front. Public Health. 12:1429474. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1429474

Edited by:

Christiane Stock, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Jacey Greece, Boston University, United StatesErwin Calgua, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala

Copyright © 2024 Baron-Epel, Douvdevany, Ivancovsky-Wajcman, Barach, Bashkin, Czabanowska, Dopelt, Davidovitch, Jakubowski, MacLeod, Malowany, Okenwa-Emegwa, Peled-Raz and Zelber-Sagi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Orna Baron-Epel, b3JuYWVwZWxAcmVzZWFyY2guaGFpZmEuYWMuaWw=

Orna Baron-Epel

Orna Baron-Epel Yana Douvdevany1

Yana Douvdevany1 Paul Barach

Paul Barach Osnat Bashkin

Osnat Bashkin Katarzyna Czabanowska

Katarzyna Czabanowska Keren Dopelt

Keren Dopelt Nadav Davidovitch

Nadav Davidovitch Szczepan Jakubowski

Szczepan Jakubowski Fiona MacLeod

Fiona MacLeod Maureen Malowany

Maureen Malowany