- College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch, Ethiopia

Background: Key essential nutrition actions (ENA) messages are a comprehensive and evidence-based nutritional package designed to improve the nutritional status during the critical first 1,000 days of life. The poor practice of ENA contributes significantly to mortality and morbidity related to malnutrition in young children. However, there is a dearth of studies focusing on the practice of key ENA messages among mothers and the factors associated with their practice. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the practice of key ENA messages among mothers of children aged 6 months to 2 years in Karat town, Konso zone, South Ethiopia in 2024.

Methods: A community-based cross-sectional study involving 421 mothers of children aged 6 months to 2 years was conducted in Karat town, Konso zone, South Ethiopia from January 15 to February 29, 2024. Respondents were chosen using computer-generated random numbers. A structured, pretested, and interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. Following coding and entry into EpiData 3.1, the data were exported to SPSS version 25 for analysis. Logistic regression (bivariate and multivariable) was employed to identify factors influencing mothers’ practice of key ENA messages, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 with a 95% confidence interval.

Results: The study found that 47.6% (95% CI: 42.8, 52.42%) of mothers demonstrated good practices. Having secondary education or higher, institutional delivery, receiving nutritional counseling during antenatal care (ANC), receipt of postnatal care (PNC) services, having good knowledge, and having a good attitude towards ENA all increase the likelihood of good practice.

Conclusion: This study emphasizes the need for multifaceted interventions to improve ENA practice among mothers residing in Karat town. To effectively address this issue, it is crucial to implement targeted education programs, strengthen postnatal care services, and nutritional counseling into routine antenatal care, promote institutional deliveries, and enhance awareness.

Introduction

The first 1,000 days of a child’s life, spanning from conception through the initial 2 years, are a crucial period for growth and development, with profound implications for long-term health outcomes (1, 2). Studies indicate that the failure to provide essential nutrients during this period leads to developmental delays, stunted growth, cognitive impairments, and heightened risks of chronic diseases in adulthood (3, 4).

The essential nutrition actions (ENA) framework provides a comprehensive approach to addressing critical nutritional needs during this period. This framework emphasizes seven key areas: exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding, and nutritional care for sick children, nutrition during pregnancy and lactation, and prevention of vitamin A, iron, and iodine deficiencies for women and children (1, 2).

The significance of ENA extends beyond individual health as it directly contributes to universal health coverage and helps alleviate the substantial economic burden associated with addressing malnutrition, which is estimated to be around 3.5 trillion US dollars annually (5, 6). By focusing on ENA, we can also make significant progress towards achieving the United Nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGs 2 and 3) targets (7) and World Health Organization (WHO’s) 2025 global nutrition targets (8).

Notably, ENA has the potential to prevent over 2 million maternal and child deaths each year. Despite its undeniable significance, over half of the children worldwide still lack access to these essential life-saving interventions (9).

Globally, in 2021, nearly 5 million children under the age of five lost their lives (10). Among these tragic fatalities, Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 55%, with nearly 2.4 million deaths occurring before the children reached their second birthday, and 1 million of these occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa (10, 11). Malnutrition-related issues contribute to nearly 45% of all under-five fatalities (12), and 25% of nutrition-related morbidity and mortality were a result of poor practice of ENA (8).

Inadequate young child feeding practices (IYCF) during the first 2 years of life alone contribute to 40% of child fatalities, which rises to 25–50% in middle-income and low-income countries (13–15). Ethiopia, in particular, faces a significant challenge with malnutrition. The 2019 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) revealed that 37% of children under the age of five suffer from stunting, with 12% classified as severely stunted. Despite recommendations from WHO, optimal feeding practices in Ethiopia remain below average, with only 59% of infants under 6 months being exclusively breastfed and a mere 14% meeting the minimum dietary diversity (16).

Maternal nutrition during pregnancy plays a crucial role in reducing the incidence of small-for-gestational-age babies by 21% and increasing the average birth weight by 41 g. However, nearly 27% of pregnant mothers in Ethiopia experience malnutrition (17). Micronutrient deficiencies, particularly iron, vitamin A, and iodine further exacerbate the situation. Iron deficiency anemia affects around 20% of preschoolers globally and 40% of women of reproductive age in Africa, with Ethiopia experiencing significant prevalence rates of 57% of children under the age of five and 40% of women of reproductive age groups (18–21).

Vitamin A deficiency has also become prevalent in Ethiopia, with 33.9% of children under the age of two and 29% of pregnant women being affected. This deficiency contributes to more than 1 million childhood deaths and over 1.5 million cases of childhood blindness worldwide (22, 23).

Additionally, iodine deficiency affects 75% of pregnant women and 30% of preschool children globally, with the highest prevalence in Africa (42%). In Ethiopia, over 39.9% of children are iodine deficient, and only 37% of households use adequately iodized salt (24, 25).

In South Ethiopia, as reported in the most recent EDHS, the prevalence of wasting and stunting among children under five is 6.3 and 36.4%, respectively. Alarmingly, only 37% of children aged 6–35 months receive vitamin A supplementation. The report also revealed that the median duration of exclusive breastfeeding is only 4 months, and a mere 9.3 and 43.9% of children meet the minimum dietary diversity and meal frequency, respectively (16).

Previous studies in Ethiopia highlighted poor ENA practices, with factors such as educational status, monthly income, parity, place of birth, utilization of postnatal care services, level of knowledge, and attitude significantly influencing maternal practices (26, 27).

However, these studies predominantly emphasized rural settings. Therefore, this study aimed to address this gap by assessing maternal practices in an urban area, Karat town, and determining the potential role of nutritional counseling during antenatal care (ANC) on mothers’ practices, which has not been the focus of previous studies.

Methods and materials

Study area and period

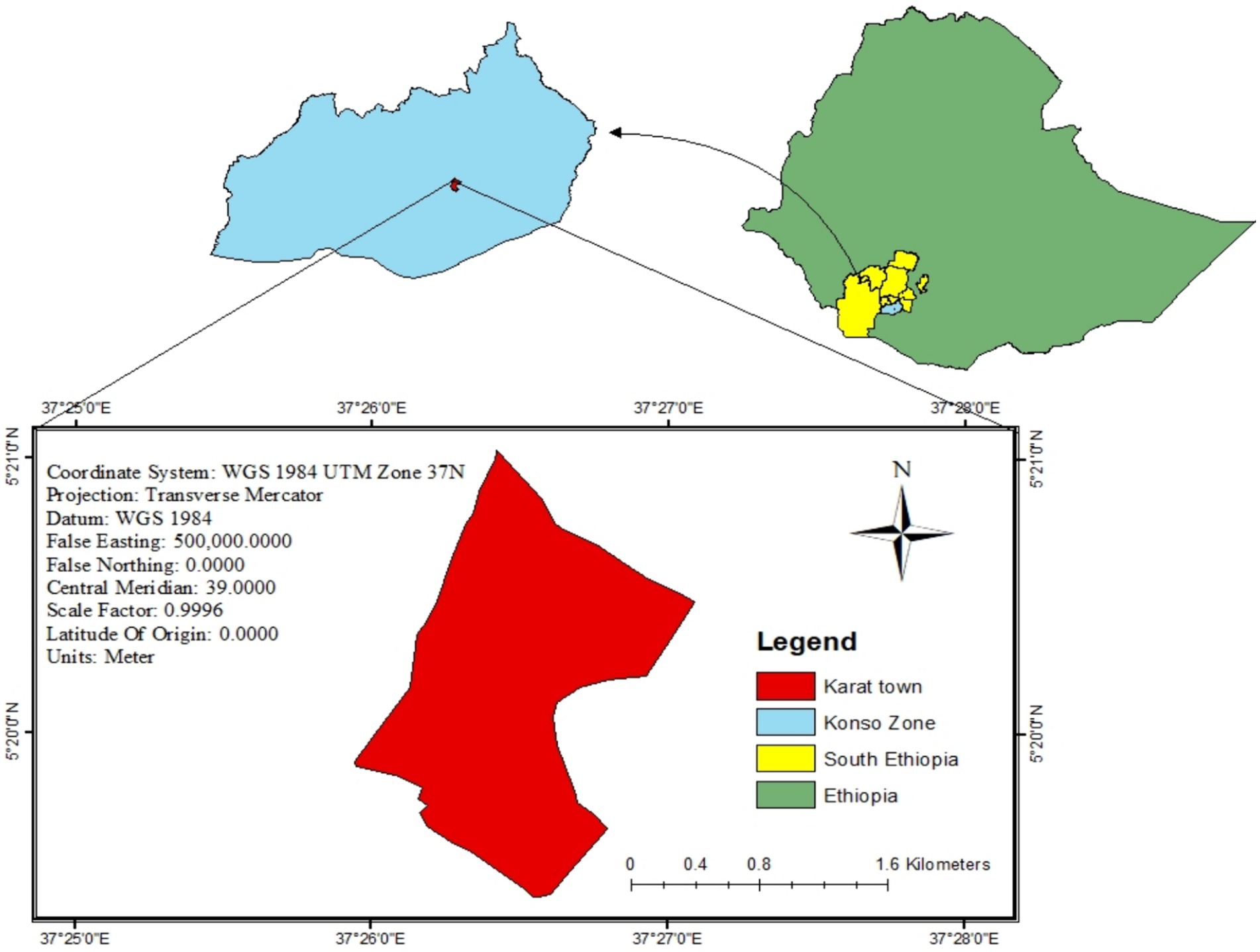

The study was conducted in Karat town, Konso Zone, South, Ethiopia. Karat is the capital town of Konso Zone, situated 607.2 km away from Addis Ababa. According to the information obtained from the town’s statistics office report (28), the total population of the town was 42,546, of whom 21,613 were female, 20,933 were male, 1,494 mothers had children from the age of 6 months to 2 years, and 8,676 households. There was 1 primary hospital and 1 health center with 7 health posts. Based on the health post they used, the town was divided into 7 administrative units (kebele) called Garisale, Dokatu, Dara paleta, Karate, Nalaya Segen, Etigele, and Gamole (Figure 1). The study was conducted from January 15 to February 29, 2024.

Figure 1. Geographic information system (GIS) representation of Karat town, Konso zone, South Ethiopia, 2024.

Study design

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted.

Source population

All mothers of children aged from 6 months to 2 years old in Karat town.

Study population

All mothers of children aged from 6 months to 2 years old in Karat town who fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria and eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

All mothers who have children aged 6 months to 2 years, have lived in Karat town for more than 6 months, and have signed consent forms were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Mothers who had proven mental illnesses or were critically ill were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination

The sample size of the study was determined using the single population proportion formula. Taking into account a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a 5% margin of error (d), along with a prevalence rate of 47.4% for the practice of key ENA messages among mothers from a study in Lemo District, Southern Ethiopia (27), and accounting in a 10% non-response rate, the final sample size was 421.

Sampling technique and procedure

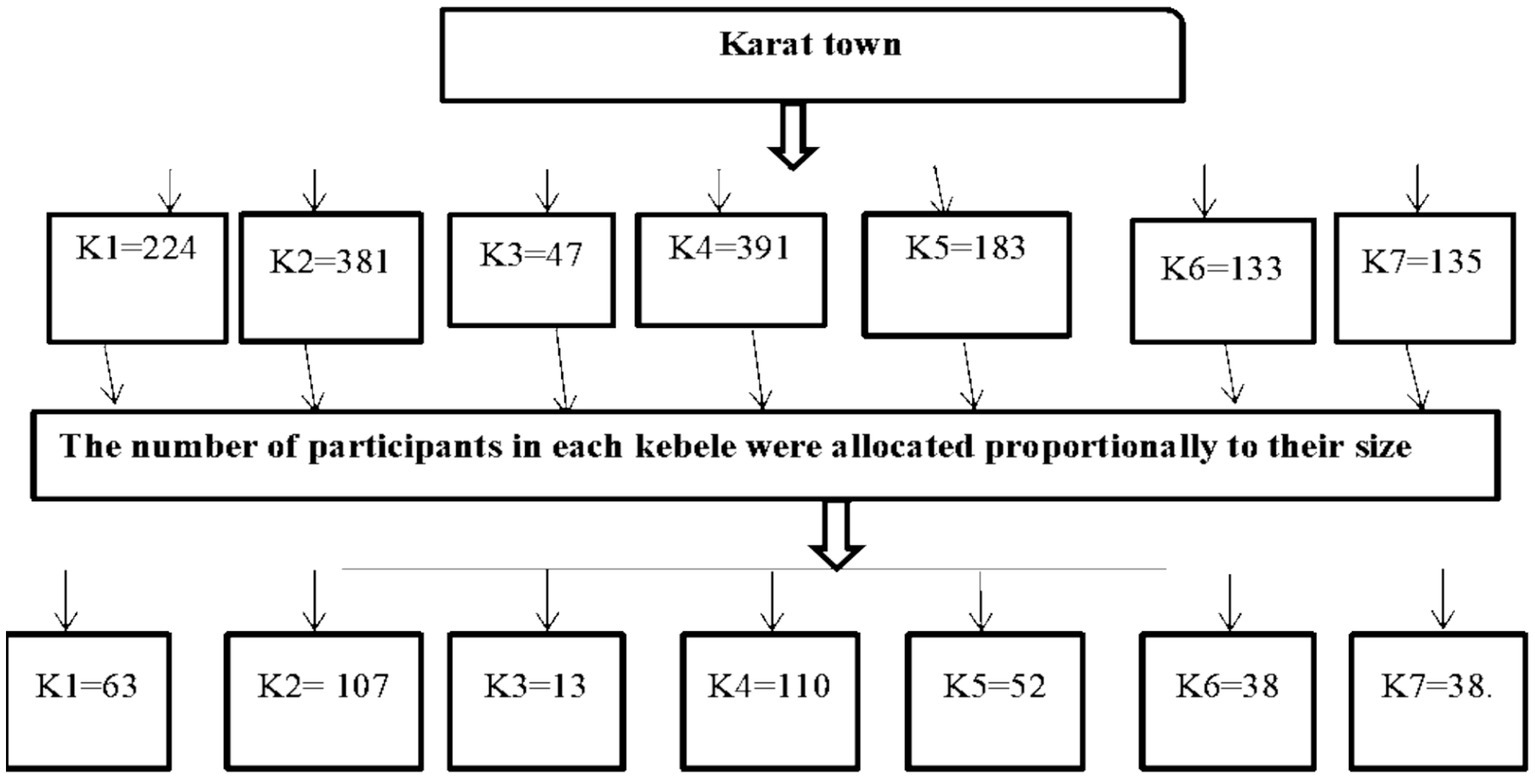

A stratified random sampling technique was employed to select mothers with children aged 6 months to 2 years. The sample size was proportionally allocated to each kebele based on the total number of mothers with children aged 6 months to 2 years. The total number of mothers with children in the target age range (N) was determined (1,494). A proportional allocation factor (Nh) was calculated (n/N). This factor (0.282) was multiplied by the number of mothers in each kebele (ni) to determine the sample size allocated to each kebele (nh). To select the required sample, in each kebele, a computer-generated random number was used from the family folders registry, which was obtained from the health extension workers (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic presentation of the sampling procedure used to assess the practice of key essential nutrition action messages and associated factors among mothers of children aged 6 months to 2 years in Karat town, Konso zone, South Ethiopia, 2024. The sampling included seven kebeles: K1 = Garisale Kebele, K2 = Dokatu Kebele, K3 = Dara paleta Kebele, K4 = Karate Kebele, K5 = Nalaya Segen Kebele, K6 = Etigele kebele, and K7 = Gamole Kebele.

Data collection instruments and procedures

Data collected for this study were obtained through a paper-based approach. A structured, pretested interviewer-administered questionnaire was used, which was adapted from previous studies (26, 27). Additionally, participants’ wealth status was evaluated using a tool consisting of 37 items adapted from EDHS (29). The questionnaire was divided into different sections, covering socio-demographic and economic factors which included eleven items (Section 1), maternal health service utilization which included three items (Section 2), mothers’ knowledge of ENA which included twenty-eight items (Section 3), mothers’ attitudes towards ENA messages included eighteen items (Section 4), and mothers’ practices related to key ENA which included twenty-seven items (Section 5).

The data collection team consisted of four diploma nurses who had previous experience in data collection. Additionally, two supervisors with Bachelor of Science degrees in nursing were recruited to oversee the study. To ensure the adequacy of the data collection tool, a pre-test was conducted on 21 mothers of children aged 6 months to 2 years in Karat zuria Woreda Fasha kebele 1 week before the actual data collection period. Based on the pretest experience, any ambiguities, confusion, or difficult words in the tool were revised. Furthermore, the internal consistency of the items in the knowledge, attitude, and practice sections was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, resulting in values of 0.8, 0.79, and 0.88, respectively.

Data quality control

To ensure quality, the questionnaire was initially developed in English and then translated into Amharic and Konsogna (local language), and then back to the English version by two independent language experts to assure consistency.

Appropriately designed and validated data collection tools were used, and data collectors and supervisors got 1 day of intensive training on the interview protocol, practice interviews, and discussions to address any questions or concerns. Supervisors and investigators maintained close oversight of the data collection processes daily. Investigators were checked for inconsistencies, and possible corrections were made during the data collection period. Study participants were interviewed in separate rooms in the house to reduce social desirability bias. To minimize the potential for recall bias, data collectors employed vitamin A, iron, and folic acid capsule samples during the data collection process. Additionally, respondents were provided with ample time to recall information accurately. Furthermore, study participants who were initially unavailable were revisited three times to ensure their inclusion in the study.

Operational definition

Key ENA messages- A total of 27 items were used to assess the practice of key ENA messages and response categories for each practice assessment question were formed as “1 = correct response” and “0 = incorrect response”. A composite index of ENA practice was calculated, with zero indicating that women did not practice any ENAs and 27 indicating that those women practiced all ENA (26, 27).

Good practice

Those respondents who score mean and above the mean score of practice questions (26, 27).

Poor practice

Those respondents who scored below the mean score of practice questions (26, 27).

Knowledge of key ENA messages

A total of 28 items were used to assess the knowledge regarding ENAs and assessment questions were formed as “1 = correct response” and “0 = incorrect response”, and women who attained at least the mean score for the ENA knowledge assessment questions was labeled as having good knowledge, while those who did not will be labeled as poor knowledge (26, 27).

Attitudes of key ENA messages

A set of 18 items was used to evaluate attitudes using the Likert scale. Each item is assigned a score ranging from 1 to 3, where 1 indicates “not good,” 2 represents uncertainty or “not sure,” and 3 signifies “good.” Mothers who achieved a score equal to or higher than the mean score for the ENA attitude assessment questions were categorized as having a good attitude, while those who fell below the mean score were classified as having a poor attitude (26).

Sick child-feeding practices involved asking mothers about the frequency of feeding their children during illness. For children aged 6–8 months, the correct response was feeding more than 2–3 meals per day, while for those aged 9–23 months, it was more than 3–4 meals per day. On the other hand, mothers who provided the usual amount of liquids or less than usual, or withheld feeding, were classified as having poor sick baby-feeding practices (30).

Appropriate feeding

This means beginning breastfeeding within the first hour of birth, continuing to EBF for 6 months, and introducing semisolids, solids, and soft foods that are culturally appropriate from 6 months while breastfeeding is continued until 2 years and beyond, and the response was categorized as “yes” or “no” to each component (31).

Minimum meal frequency

Feeding 2–3 times per day for a child aged 6–8 months and 3–4 times per day for a 9–23 months aged child among breastfeeding mothers and at least 4 times per day among non-breastfeeding mothers, assessed by asking mothers the number of meals or feeds a child receives in the last 24 h before actual data collection (32, 33).

Minimum dietary diversity is the consumption of four or more food groups for higher quality, to meet the daily energy and nutrient requirements of the seven recommended food groups namely grains, roots, & tubers, legumes, and nuts, dairy products, flesh foods, fruits, and vegetables in the last 24 h prior actual data collection, responses were categorized as “yes” or “no” for each food group, and children who score at least four were considered to have met the requirement (34).

Wealth index

It is a composite measure of a household’s cumulative living standard. Based on the net score, the wealth status of respondents is classified into three. For a total of 37 items, including domestic animals, durable assets, productive assets, and dwelling characteristics, the response was categorized as “1 = yes” and “0 = no”, and any variable or assets owned by more than 90% or less than 5% were excluded. The Keiser-Mayer Olkin measure of sample adequacy (≥0.6) is used to check the principal component analysis (PCA) assumption, anti-image correlations (> 0.4), and Bartlett Sphericity Test (p-value 0.05) (27).

Proper utilization of iodized salt

Adding salt to cooking at the end or right after cooking in the last 24 h (35).

Having postnatal care service

Mothers who attend at least one PNC service from health institutions by health professionals within 42 days of delivery (36).

Data processing and analysis

After the data were collected, it was checked for completeness and coded before being entered. Then, the data were entered into epi data version 3.1 statistical software and then exported to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 for analysis. Descriptive statistics such as percentages, frequency, mean, and standard deviation was used to summarize the characteristics of the study participants and the findings were presented by using tables and graphs. The binary logistic regression model was fitted to identify factors associated with the practices of mothers towards key ENA. Initially, bivariable analysis was done to identify the candidate explanatory variables for the multivariable analysis. Thereafter, all explanatory variables having a p-value of less than 0.25 in the bivariable analysis were included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis to handle the effect of possible confounders and identify independent predictors of the practice of ENA messages in the final model. Model fitness for the final model was checked using Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit (0.367). Multicollinearity was checked using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF < 10). Adjusted odds ratio with 95% CI and a p-value of less than 0.05 were used to determine the level of significance.

Result

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

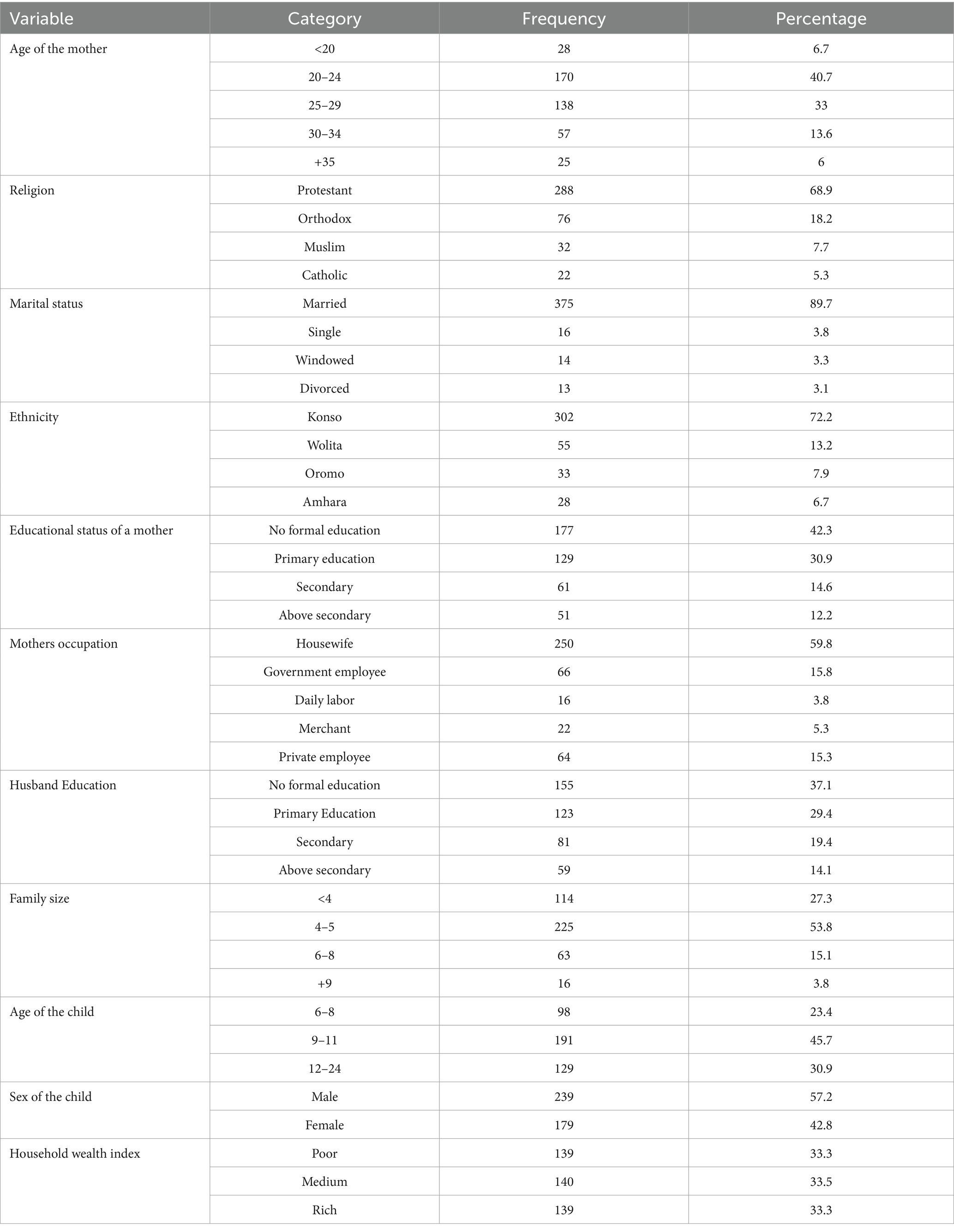

This study included a total of 418 mothers of children aged 6–24 months, resulting in a response rate of 99.3%. The mean age of the mothers was 25.66 years ±4.93.40.7% of them fell within the age range of 20–24 years, followed by those aged 25–29 (33%). The mean age of the children was 11.28 months ±3.9. Most of the respondents were married (89.7%), and 68.9% identified as followers of the Protestant Christian religion Additionally, 53.8% reported having a family size of four to five, while 42.3% had no formal education. A significant portion of the respondents were housewives (59.8%), around 34% had a medium household wealth index, and 37.1% reported that their husbands had no formal education (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of mothers of children aged 6 months to 2 years old in Karat town, Konso zone, South Ethiopia, 2024.

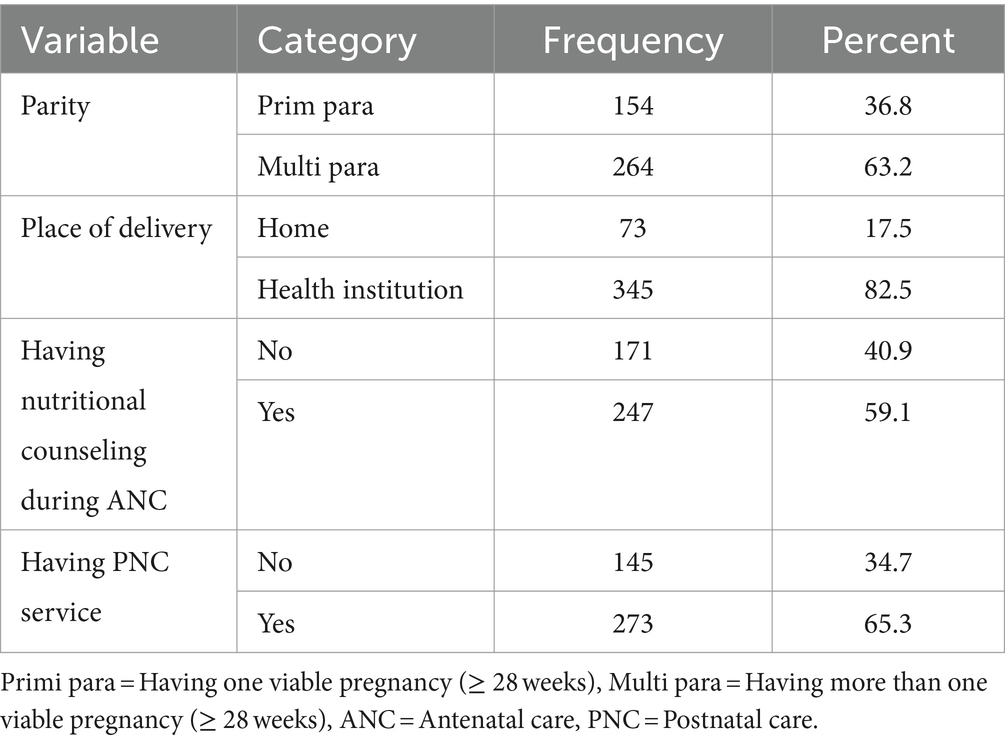

Maternal and child health-related information of study participants

Among the study participants, more than half (63.2%) were multiparous, and the majority (82.5%) delivered their child to a healthcare facility. Furthermore, 65.3% of mothers received at least one postnatal service, and 59.1% of participants received nutritional counseling during antenatal care (ANC) (Table 2).

Table 2. Maternal and child health-related information of mothers of children aged 6 months to 2 years old in Karat town, Konso zone, South Ethiopia,2024.

Knowledge of respondents towards key ENA messages

In Karat town, 48.1% (95% CI, 43.28 to 52.9%) of mothers of children aged 6 months to 2 years were knowledgeable about key essential nutrition action messages. Specifically, most of the (83.7%) mothers exhibited a strong understanding of preventing vitamin A deficiency, while 60.8% knew about preventing iron deficiency anemia. However, only 41.1% of mothers were knowledgeable about exclusive breastfeeding (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Good knowledge of respondents towards key ENA message in Karat town, Konso zone, South Ethiopia, 2024.

Attitudes of the mother towards key ENA messages

In this study, 47.6% (95% CI, 42.8–52.42) of mothers had a good attitude regarding key essential nutrition action messages.

The practice of respondents on key ENA messages

The overall practice of key ENA messages among mothers 47.6% (95% CI: 42.8, 52.42%) had good practice. Iron deficiency anemia prevention and iodine deficiency prevention were the most commonly practiced items by 63.9 and 59.8% of respondents, respectively. However, 41.6% of respondents had good practice in complementary feeding (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Good practice of key essential nutrition action messages among mothers of children aged 6 months to 2 years old in Karat town, Konso zone, South Ethiopia, 2024.

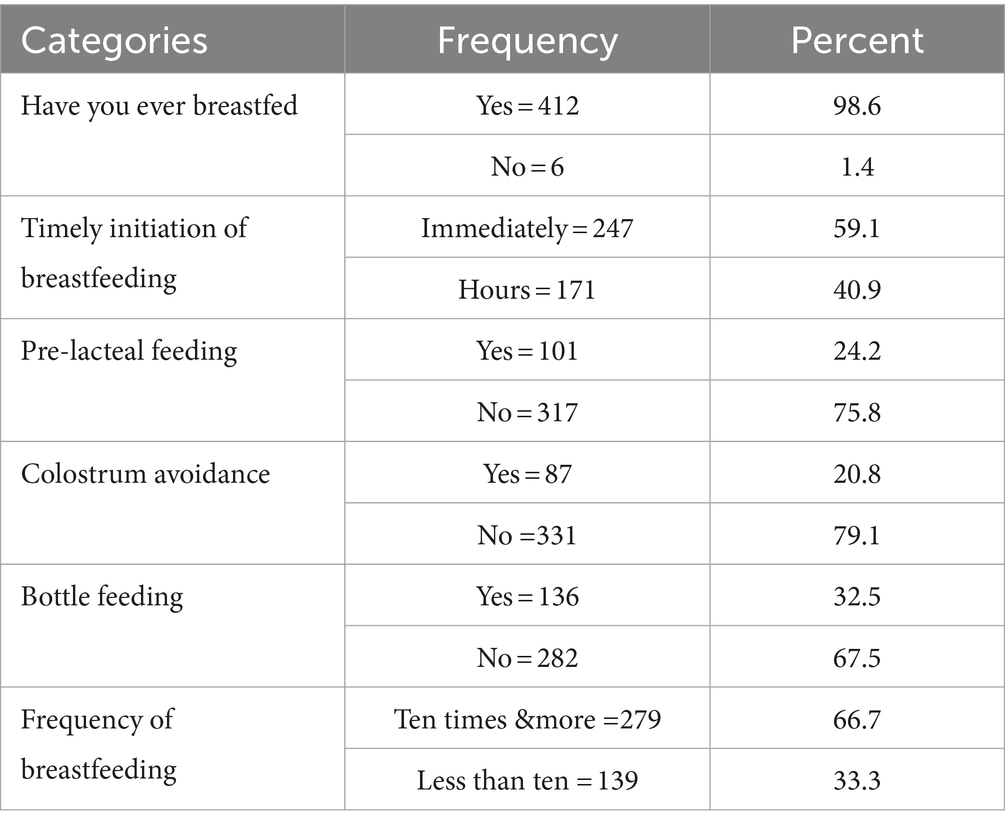

Exclusive breastfeeding practice

In this study, 98.6% of mothers chose to breastfeed their children, with 59.1% initiating breastfeeding promptly. However, 24.2% of mothers practiced pre-lacteal feeding, 20.8% avoided feeding colostrum, and 32.5% resorted to bottle feeding (Table 3).

Table 3. Exclusive breastfeeding practice of mothers of children aged 6 months to 2 years old in Karat town, Konso zone, South Ethiopia, 2024.

Complementary feeding practice

The study revealed that a majority of participants (94.7%) introduced complementary feeding to their children. Of those 71.1% of them initiated at 6–8 months of age. Less than half of the mothers (44.7%) were able to meet the minimum meal frequency (MMF) requirements for their children, and only 25.8% managed to offer the minimum dietary diversity recommended for their children. Furthermore, 98.1% of mothers continued to give breastfeeding to their children.

Sick child feeding practice

In this study, about half (50.5%) of study participants reported that their children had experienced illness in the 2 weeks preceding data collection. Among mothers of these children, 49% (95% CI: 44–53.8%) were found to exhibit good feeding practices with 73% providing more breast milk than usual, 19.9% offering the same amount as usual, and 7.1% giving lesser amount than usual to their sick children. Regarding fluid intake, 58.8% of mothers of sick children gave extra fluids, 27% gave the same amount as usual, and 14.2% gave less fluid than usual. Furthermore, concerning the quantity of food being provided, the majority (53.1%) of sick children were given more than the usual amount, followed by 36% who were provided with the same amount as usual, and 10.9% were given less than the usual amount.

Regarding the nutritional practice of respondents during their pregnancy and lactation period in the study, 56.9% of respondents reported having an additional meal. Notably, 84.2% of respondents included animal products in their meal variety.

Practice of respondents on the prevention of vitamin a, iron deficiency anemia, and iodine deficiency

Less than half (45.7%) of mothers consumed Vitamin A supplements within 45 days of delivery, while 78% of their children received vitamin A supplementation at least once. In the 24 h dietary recall before the date of data collection, 59.8% of participants consumed green leafy vegetables, 39.2% consumed animal sources, and only 1% consumed ripe fruits like mango, from vitamin A-rich foodstuffs.

Regarding iron deficiency anemia prevention practice, three-fourths (74.4%) of participants reported taking iron/folic acid supplements. Furthermore, 81.1% of individuals included organ meats and other animal products in their diets. Additionally, a significant 81.1% of participants consumed green leafy vegetables.

Moreover, in terms of iodine deficiency prevention practice, only 31.1% of mothers used non-iodized salt for preparing meals. Of those who added salt to stew, 62.2% did so in the middle of the cooking process, while 37.8% added it at the end. Additionally, 62% of mothers stored salt in a closed container.

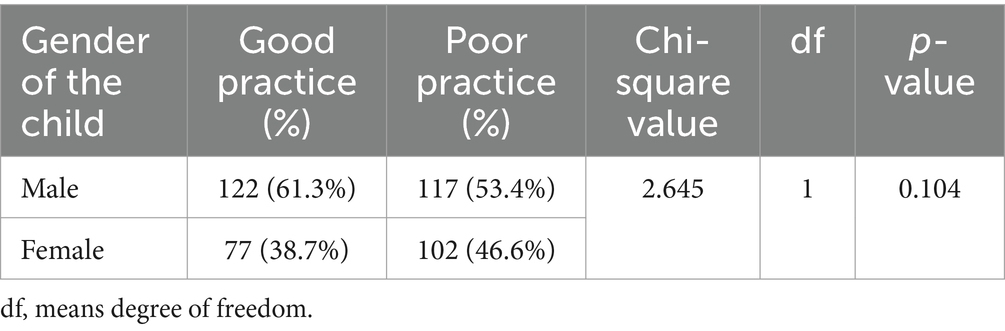

The association of the gender of the child with maternal practice towards key essential nutrition action messages

The study found that there is no significant association between the gender of the child and maternal practice towards key essential nutrition action messages, with its Pearson chi-square test value (2.645) and its p-value of (0.104) (Table 4).

Table 4. The association of gender of the child with maternal practice towards key essential nutrition action in Karat town, Konso zone, South Ethiopia, 2024.

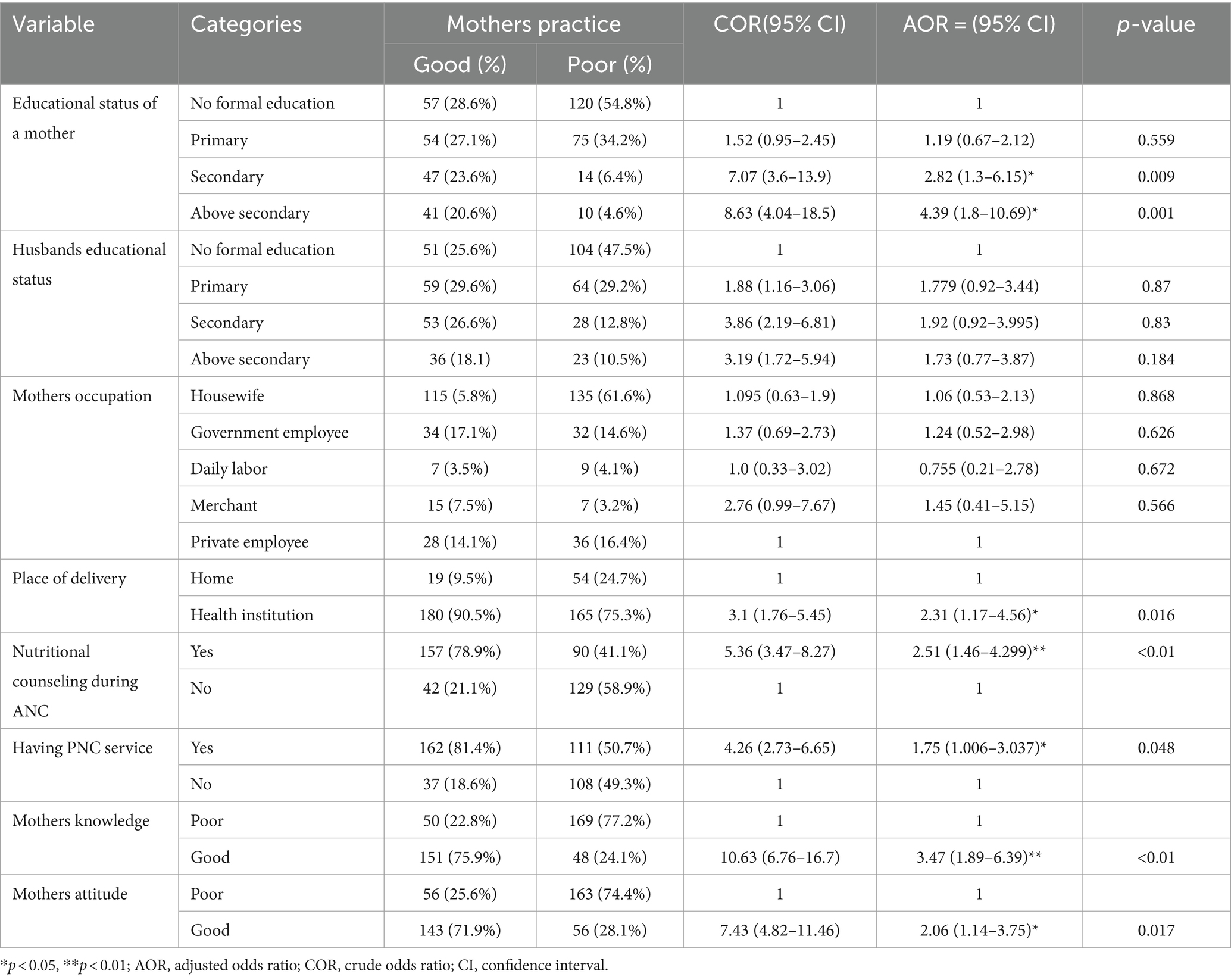

Factors associated with the practice of key ENA messages

In the bivariable analysis, factors such as the mother’s education level, the husband’s education level, the mother’s occupation, place of delivery, receiving nutritional counseling during ANC, receiving PNC services, knowledge, and attitudes towards key ENA messages were found to have statistical significance (p < 0.25). However, in the multivariable analysis, after considering all these factors together, the educational status of the mother, receiving nutritional counseling during ANC, receiving PNC services, place of delivery, knowledge, and attitudes towards key ENA messages were identified as statistically significant (p < 0.05).

The odds of practice approximately three times with Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR: 2.82, 95% CI: 1.3–6.15) were higher among mothers with secondary education and about four times (AOR: 4.39, 95% CI: 1.8–10.69) higher among mothers with above secondary education than mothers with no formal education. In comparison to mothers who did not receive nutritional counseling during ANC, the odds of practice increased about three times (AOR: 2.51, 95% CI: 1.46–4.299) in those who received it. The odds of practice were 1.75 times more likely in mothers who receive postnatal care services when compared to their counterparts (AOR: 1.75, 95% CI:1.006–3.037), Mothers who deliver their child in a health institution were about two times more likely to practice than those who delivered at home (AOR: 2.31, 95% CI:1.17–4.56). Furthermore, mothers who had good knowledge and attitude towards key ENA were about three times (AOR: 3.47, 95% CI: 1.89–6.39) and two times (AOR: 2.06, 95% CI: 1.14–3.75) higher in practicing key ENA messages than those who had not, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5. Factors associated with the practice of key essential nutrition action messages among mothers of children aged 6 months to 2 years old in Karat town, Konso zone, South Ethiopia, 2024.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the practice of key ENA messages and associated factors among mothers of children aged 6 months to 2 years in Karat town, Konso zone, South Ethiopia. According to the findings of this study, the overall magnitude of good ENA practice was 47.6% (95% CI: 42.8, 52.42%).

The result of this study is consistent with similar studies conducted in the Northeast (46.5%) (26) and Southern Ethiopia (47.4%) (27). However, it was lower compared to a study in Southwest Ethiopia (37). Possibly due to differences in the study population, the level of knowledge, and the attitude of respondents towards ENA.

The exclusive breastfeeding practice in this study was found to be 52.4%, which is higher than the rates reported in previous studies conducted in Addis Ababa (29.3%) (38) and Northern Ethiopia (30.7, 34.8%) (39, 40). However, it falls below rates reported in the Amhara (79%) (41) and Sidama regions of Ethiopia (60.9%) (42). These variations could be attributed to factors such as maternal employment status, and utilization of maternal and child health services.

Complementary feeding practices were found to be inadequate, with only 25.8% of children meeting the minimum dietary diversity requirement. Consistent with findings in a study in Eastern Ethiopia (24.4%) (43), and (27.3%) in Wolita (33), but higher than rates reported in rural settings studies in the Oromia region (16%) (44), and (12.6%) in Northwest Ethiopia (45). Conversely, higher rates were observed in urban areas such as Addis Ababa (59.9%) (34). This could be influenced by socio-economic factors and access to diverse food and nutrition awareness (46–48).

Regarding sick child feeding practices, 49% of mothers demonstrated good practices, which is consistent with studies conducted in Eastern Ethiopia (45%) (49), the Gamo zone in South Ethiopia (45%) (50), and Addis Ababa (54%) (30). However, it is lower than the study conducted in Mirab Abaya, South Ethiopia (70.7%) (51). The variations in results could be attributed to factors such as marital status, access to support for child feeding, information availability, and the educational background of the mothers.

In terms of nutritional practice during pregnancy and lactation, 56.6% of participants reported consuming an additional meal, a higher percentage compared to previous studies in Southern (36.9%) (52), and Northeast Ethiopia (43.9%) (53). However, it was lower than the study in the Oromia region (75.4%) (54). The observed variations in nutritional practices could be attributed to factors such as access and utilization of maternal and child health services, socio-economic status, and the educational background of the respondents.

In terms of the prevention of vitamin A deficiency practice, 45.7% of mothers reported taking vitamin A within 45 days of delivery. This is higher than 39.1% in a study conducted in Southern Ethiopia (27) The possible reason might be differences in the study areas, period, and socio-demographic characteristics. However, it is lower than 63.5% in the Amhara region (26). The disparities in uptake could be attributed to varying levels of knowledge and attitudes towards ENA among mothers. Additionally, 78% of children received vitamin A supplements at least once, which is notably higher compared to previous studies in the Sidama region (36.2%) (55), and (58%) in Southern Ethiopia (56). The rural settings and lower educational backgrounds of mothers in these studies may contribute to the differences.

Regarding the practice of mothers on iron deficiency anemia prevention, 74.4% of mothers took iron/folic acid during their recent pregnancy, which was found to be higher than rates reported in South and Eastern Ethiopia (50.06%) (57), Kenya (31.7%) (58) and Pakistan (38.3%) (59). The higher compliance could be linked to factors like urban residence, facility-based deliveries, and higher educational levels among participants.

Furthermore, regarding iodine deficiency prevention practice, 68.9% of participants reported utilizing iodized salt, which closely aligns with 72.2% in the Tigray region (60). However, it is higher compared to studies in Southeast Ethiopia (56.6%) (61), and the Somali region (26.6%) (62). The urban setting of this study and a higher proportion of mothers with primary education or above may contribute to better awareness and easier access to iodized salt.

Regarding factors associated with the practice of key ENA messages, mothers with secondary education or above are more likely to practice ENA, compared to mothers with no formal education. This finding is congruent with previous studies conducted in the Amhara region (26) and Southern Ethiopia (27). The increased awareness of health-related issues, including nutrition, among educated participants, positively influences their engagement in ENA practices. This, in turn, leads to better maternal and child nutrition outcomes (63, 64).

Another significant factor that influences ENA practices is the place of delivery. Delivery in health institutions increases twice the odds of practicing ENA, than those who gave birth at home. Which was found to be congruent with studies in Northern (26) and Southern Ethiopia (27). This could be attributed to the nutritional education and support provided by trained health professionals in health institutions, which leads to immediate benefits such as improved postnatal nutrition and reduced risk of malnutrition.

Mothers who received nutritional counseling during ANC were found to be three times more likely to engage in ENA practices compared to those who did not receive it. This finding is supported by a study conducted in Southwest Ethiopia (37), and Eastern Ethiopia (65). A possible explanation for this effect is that nutritional counseling provides valuable information about dietary requirements during pregnancy and lactation (66), increasing mothers’ knowledge about essential nutrition actions (67). Moreover, counseling facilitates behavioral changes related to healthier eating habits and lifestyle choices, as well as equipping mothers with information on where to access nutritious foods and supplements (68). The use of positive reinforcement techniques during counseling sessions further strengthens desired behaviors associated with ENA (69).

Moreover, receiving PNC services is also associated with higher odds of practicing ENA. This finding is consistent with studies in the Amhara region (26), and Southern Ethiopia (27). The reason behind this might be, that PNC sessions often include nutrition education, emphasizing exclusive and complementary feeding practices. This likely encourages mothers to adopt and adhere to ENA, which helps to address nutritional challenges for both mothers and children.

Additionally, attitude and knowledge emerged as other influencers, and the likelihood of practice increased twice among a mother who had a good attitude regarding ENA. This finding is concurrent with a previous study in the Amhara region (26). A possible explanation could be that a positive attitude towards a given behavior will lead to more practice of that behavior as evidenced by different research studies (70, 71), and by a well-known cognitive consistency theory (72).

Furthermore, mothers who had good knowledge were more likely to practice essential nutrition action. This is in agreement with a study in the Amhara region (26). The possible reason could be, that mothers with good knowledge are more likely to practice exclusive breastfeeding and more likely to consult healthcare professionals when they have concerns about their child’s nutrition, which can lead to better nutrition practices for their children (70, 73).

The study’s results have important clinical implications for enhancing dietary diversity, improving health education and awareness initiatives, empowering healthcare professionals to provide comprehensive postnatal care and nutritional counseling, advocating for institutional deliveries, and guiding the development of evidence-based policies and programs aimed at enhancing maternal and child nutrition in Ethiopia.

Conclusion

This study revealed that the practice of key essential nutrition action messages among mothers was found to be poor. Factors such as having secondary education or higher, delivering in a health institution, receiving postnatal care services, and nutritional counseling during antenatal care, and possessing good knowledge and attitudes were significantly associated with good practice.

Recommendation

The concerned body including governmental and non-governmental organizations should give due emphasis on maternal education for those with lower education levels, enhancing postnatal care services, strengthening nutritional counseling into routine ANC, and promoting institutional deliveries. Future research should focus on healthcare providers’ perspectives on delivering ENA messages and the role of social support networks in promoting optimal nutrition practices among mothers to uncover other influencing factors.

Strength and limitation of the study

Strengths

The study’s strengths lie in its focus on key ENA messages tailored specifically for mothers residing in urban areas, rather than solely focusing on rural settings. Additionally, the study’s ability to offer an accurate snapshot of maternal practices within this particular population without requiring long-term follow-up.

Limitations

The cross-sectional nature of this study makes causal relationships between dependent and independent variables impossible. Since the study was based on self-reports, the respondents might be prone to social desirability bias. Finally, because women were asked about incidents that had already occurred before the study period, there may be a risk of recall bias.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institution’s Research Ethics Review Board of Arbaminch University (protocol No. IRB/1433/ 2023). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ND: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZJ: Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software. FM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Arba Minch University deserves our heartfelt gratitude for allowing us to conduct this research and present the thesis report. We also appreciate the dedication and time spent by data collectors, supervisors, and study participants during the data collection period.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

AOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; ANC, Antenatal Care; CI, Confidence Interval; COR, Crude Odds Ratio; EDHS, Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey; ENA, Essential Nutrition Action; IYCF, Infant Young Child Feeding; MCH, Maternal and Child Health; PNC, Postnatal Care; WHO, World Health Organization.

References

1. World Health Organization . Essential nutrition (2019). 210 p https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/326261/9789241515856-eng.pdf.

2. Gebremichael, B, Beletew Abate, B, and Tesfaye, T. Mothers had inadequate knowledge towards key essential nutrition action messages in mainly rural Northeast Ethiopia. J Nutr Sci. (2021) 10:e19. doi: 10.1017/jns.2021.10

3. We are IntechOpen , The world’s leading publisher of open access books built by scientists, for scientists TOP 1% introductory chapter: Impact of first 1000 days nutrition on child development and general health. Al-Zwaini, I.J., Al-Ani, Z.R. and Hurley, W. Infant Feeding: Breast Versus Formula. BoD–Books on Demand. (2020).

4. Likhar, A, and Patil, MS. Importance of maternal nutrition in the first 1, 000 days of life and its effects on child development: a narrative. Review. (2022) 14:e30083–13. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30083

5. WHO (World Health Organisation) . Nutrition in universal health coverage. World Health Organization, (WHO/NMH/NHD/19.24). License: CC BY-NC-SA.3.0 IGO. (2019). 19 p. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-19.24.

6. Global P . The cost of malnutrition: why policy action is urgent. Glob Panel Agric Food Syst Nutr. (2016) 3:1–11.

7. Osborn, D, Cutter, A, and Ullah, F. Universal sustainable development goals: understanding the transformational challenge for developed countries. Univers Sustain Dev Goals. (2015) May:1–24.

8. Organization WH . Global targets 2025 to improve maternal, infant and young child nutrition. World Health Organization. (2017).

9. Guyon, A, Quinn, V, Nielsen, J, and Stone-Jimenez, M. Essential Nutrition Actions and Essential Hygiene Actions training guide: Health workers and nutrition managers. Washington, DC: Core Group. (2015).

10. Sharrow, D, Hug, L, You, D, Alkema, L, Black, R, Cousens, S, et al. Global, regional, and national trends in under-5 mortality between 1990 and 2019 with scenario-based projections until 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Lancet Glob Health. (2022) 10:e195–206. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00515-5

11. Karlsson, O, Kim, R, Hasman, A, and Subramanian, SV. Age distribution of all-cause mortality among children younger than 5 years in low- and middle-income countries. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:1–13. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.12692

12. Black, RE, Victora, CG, Walker, SP, Bhutta, ZA, Christian, P, De Onis, M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. (2013) 382:427–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X

13. Hassen, SL, Temesgen, MM, Marefiaw, TA, Ayalew, BS, Abebe, DD, and Desalegn, SA. Infant and young child feeding practice status and its determinants in Kalu District, Northeast Ethiopia: community-based cross-sectional study. Nutr Diet Suppl. (2021) 13:67–81. doi: 10.2147/NDS.S294230

14. Zong, X, Wu, H, Zhao, M, Magnussen, CG, and Xi, B. Global prevalence of WHO infant feeding practices in 57 LMICs in 2010–2018 and time trends since 2000 for 44 LMICs. EClinicalMedicine. (2021) 37:100971–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100971

15. Habtewold, TD, Mohammed, SH, Endalamaw, A, Akibu, M, Sharew, NT, Alemu, YM, et al. Breast and complementary feeding in Ethiopia: new national evidence from systematic review and meta-analyses of studies in the past 10 years. Eur J Nutr. (2019) 58:2565–95. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1817-8

17. Yismaw, WS, and Teklu, TS. Nutritional practice of pregnant women in Buno Bedele zone, Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. (2022) 19:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12978-022-01390-1

18. Han, L, Zhao, T, Zhang, R, Hao, Y, Jiao, M, Wu, Q, et al. Burden of nutritional deficiencies in China: findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Nutrients. (2022) 14:3919. doi: 10.3390/nu14193919

19. Negash, BT, and Ayalew, M. Trend and factors associated with anemia among women reproductive age in Ethiopia: a multivariate decomposition analysis of Ethiopian demographic and health survey. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0280679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0280679

20. Wilunda, C, Tanaka, S, Esamai, F, and Kawakami, K. Prenatal anemia control and anemia in children aged 6–23 months in sub-Saharan Africa. Matern Child Nutr. (2017) 13:1–10. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12375

21. Gebreweld, A, Ali, N, Ali, R, and Fisha, T. Prevalence of anemia and its associated factors among children under five years of age attending at Guguftu health center, south Wollo, Northeast Ethiopia. PLoS One. (2019) 14:1–13. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6611584/pdf/pone.0218961.pdf

22. Abrha, T, Girma, Y, Haile, K, Hailu, M, and Hailemariam, M. Prevalence and associated factors of clinical manifestations of vitamin a deficiency among preschool children in an asked-tsimbl rural district, North Ethiopia, a community-based cross-sectional study. Arch Public Health. (2016) 74:4–8. doi: 10.1186/s13690-016-0122-3

23. Eyeberu, A, Getachew, T, Tiruye, G, Balis, B, Tamiru, D, Bekele, H, et al. Vitamin a deficiency among pregnant women in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Health. (2023) 15:630–43. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihad038

24. Candido, AC, de Morais, N, Dutra, LV, Pinto, CA, Franceschini, SDCC, and Alfenas, RCG. Insufficient iodine intake in pregnant women in different regions of the world: a systematic review. Arch. Endocrinol Metab. (2019) 63:306–11. doi: 10.20945/2359-3997000000151

25. Zimmermann, MB, and Andersson, M. Update on iodine status worldwide. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. (2012) 19:382–7. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e328357271a

26. Beletew, B, Gebremichael, B, Tesfaye, T, Mengesha, A, and Wudu, M. The practice of key essential nutrition action messages and associated factors among mothers of children from birth up to 2 years old in Wereilu Wereda, south Wollo zone, Amhara, Northeast Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. (2019) 19:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1814-y

27. Habte, A, Gizachew, A, Ejajo, T, and Endale, F. The uptake of key essential nutrition action (ENA) messages and its predictors among mothers of children aged 6–24 months in southern Ethiopia, 2021: a community-based crossectional study. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0275208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275208

29. Gunasekera, HR . Demographic and health survey--1993. Sir Lanka J Popul Stud. (1998) 1:107–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00328.x

30. Degefa, N, Tadesse, H, Aga, F, and Yeheyis, T. Sick child feeding practice and associated factors among mothers of children less than 24 months old, in Burayu town, Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr. (2019) 2019:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2019/3293516

31. Hoche, S, Meshesha, B, and Wakgari, N. Sub-optimal breastfeeding and its associated factors in rural communities of Hula District, southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Ethiop J Health Sci. (2018) 28:49–62. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v28i1.7

32. Wagris, M, Seid, A, Kahssay, M, and Ahmed, O. Minimum meal frequency practice and its associated factors among children aged 6-23 months in Amibara District, north East Ethiopia. J Environ Public Health. (2019) 2019:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2019/8240864

33. Mekonnen, TC, Workie, SB, Yimer, TM, and Mersha, WF. Meal frequency and dietary diversity feeding practices among children 6–23 months of age in Wolaita Sodo town, southern Ethiopia. J Health Popul Nutr. (2017) 36:18. doi: 10.1186/s41043-017-0097-x

34. Solomon, D, Aderaw, Z, and Tegegne, TK. Minimum dietary diversity and associated factors among children aged 6–23 months in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int J Equity Health. (2017) 16:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0680-1

35. Hawas, SB, Lemma, S, Mengesha, S, Demissie, H, and Segni, M. Proper utilization of adequately iodized salt at household level and associated factors in Asella town Arsi zone Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. J Food Process Technol. (2016) 7:573. doi: 10.4172/2157-7110.1000573

36. Fantaye, C, Melkamu, G, and Makeda, S. Postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among mothers who delivered in Shebe Sombo Woreda, Jimma zone, Ethiopia. Int J Womens Health Wellness. (2018) 4, 3–6. doi: 10.23937/2474-1353/1510078

37. Mudasir, S, Muktar, E, and Oumer, A. The practice of key essential nutrition actions among pregnant women in Southwest Ethiopia: implications for optimal pregnancy outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2024) 24:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12884-024-06354-w

38. Shifraw, T, Worku, A, and Berhane, Y. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices of urban women in Addis Ababa public health centers, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. (2015) 10:22–9. doi: 10.1186/s13006-015-0047-4

39. Biks, GA, Tariku, A, and Tessema, GA. Effects of antenatal care and institutional delivery on exclusive breastfeeding practice in Northwest Ethiopia: a nested case-control study. Int Breastfeed J. (2015) 10:30–6. doi: 10.1186/s13006-015-0055-4

40. Chekol, DA, Biks, GA, Gelaw, YA, and Melsew, YA. Exclusive breastfeeding and mothers’ employment status in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. (2017) 12:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13006-017-0118-9

41. Asemahagn, MA . Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practices among mothers in Azezo district, Northwest Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. (2016) 11:22–7. doi: 10.1186/s13006-016-0081-x

42. Adugna, B, Tadele, H, Reta, F, and Berhan, Y. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in infants less than six months of age in Hawassa, an urban setting, Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. (2017) 12:4–11. doi: 10.1186/s13006-017-0137-6

43. Sema, A, Belay, Y, Solomon, Y, Desalew, A, Misganaw, A, Menberu, T, et al. Minimum dietary diversity practice and associated factors among children aged 6 to 23 months in Dire Dawa City, Eastern Ethiopia: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Glob Pediatr Health. (2021) 8:2333794X2199663. doi: 10.1177/2333794X21996630

44. Agize, A, Jara, D, and Dejenu, G. Level of knowledge and practice of mothers on minimum dietary diversity practices and associated factors for 6-23-month-old children in Adea Woreda, Oromia, Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int. (2017) 2017:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2017/7204562

45. Beyene, M, Worku, AG, and Wassie, MM. Dietary diversity, meal frequency and associated factors among infant and young children in Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2333-x

46. Aliyo, A, Golicha, W, and Fikrie, A. Household dietary diversity and associated factors among rural residents of Gomole District, Borena zone, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. (2022) 9:233339282211080–8. doi: 10.1177/23333928221108033

47. Kolliesuah, NP, Olum, S, and Ongeng, D. Status of household dietary diversity and associated factors among rural and urban households of northern Uganda. BMC Nutr. (2023) 9:83–16. doi: 10.1186/s40795-023-00739-4

48. Rahman, MA, Kundu, S, Rashid, HO, Tohan, MM, and Islam, MA. Socio-economic inequalities in and factors associated with minimum dietary diversity among children aged 6-23 months in South Asia: a decomposition analysis. BMJ Open. (2023) 13:e072775. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-072775

49. Semahegn, A, Tesfaye, G, and Bogale, A. Complementary feeding practice of mothers and associated factors in Hiwot Fana specialized hospital, eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. (2014) 18:1–11. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.143.3496

50. Hailu, FM, Kefene, SW, Sorrie, MB, Mekuria, MS, and Guyo, TG. Sick child’s feeding practices and associated factors among mothers with sick children aged less than 2 years in Gamo zone, southern Ethiopia. Does the participation of fathers contribute to improving nutrition? A facility-based cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1256499

51. Fikadu, T, and Girma, S. Feeding practice during diarrheal episode among children aged between 6 to 23 months in Mirab Abaya District, Gamo Gofa zone, Southern Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr. (2018) 2018:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2018/2374895

52. Abute, L, Beyamo, A, Erchafo, B, Tadesse, T, Sulamo, D, and Sadoro, T. Dietary practice and associated factors among pregnant women in Misha Woreda, South Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. J Nutr Metab. (2020) 2020:5091318. doi: 10.1155/2020/5091318

53. Aliwo, S, Fentie, M, Awoke, T, and Gizaw, Z. Dietary diversity practice and associated factors among pregnant women in north East Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. (2019) 12:123–6. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4159-6

54. Tsegaye, D, Tamiru, D, and Belachew, T. <p>factors associated with dietary practice and nutritional status of pregnant women in rural communities of Illu aba Bor zone, Southwest Ethiopia</p>. Nutr Diet Suppl. (2020) 12:103–12. doi: 10.2147/NDS.S257610

55. Nigusse, T, and Gebretsadik, A. Vitamin a supplementation coverage and ocular signs among children aged 6-59 months in Aleta Chuko Woreda, Sidama zone, southern Ethiopia. J Nutr Metab. (2021) 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2021/8878703

56. Berihun, B, Chemir, F, Gebru, M, and GebreEyesus, FA. Vitamin a supplementation coverage and its associated factors among children aged 6–59 months in west Azernet Berbere Woreda, south West Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. (2023) 23:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12887-023-04059-1

57. Mengistu, GT, Mengistu, BK, Gudeta, TG, Terefe, AB, Habtewold, FM, Senbeta, MD, et al. Magnitude and factors associated with iron supplementation among pregnant women in southern and eastern regions of Ethiopia: further analysis of mini demographic and health survey 2019. BMC Nutr. (2022) 8:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40795-022-00562-3

58. Kotonto, AS, and Wakoli, AB. Factors associated with iron and folic acid supplementation among pregnant women aged 15-45 years attending Naroosura health center, Narok County, Kenya. Int J Community Med Public Health. (2021) 8:4672. doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20213760

59. Nisar, YB, Dibley, MJ, and Mir, AM. Factors associated with non-use of antenatal iron and folic acid supplements among Pakistani women: a cross-sectional household survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2014) 14:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-305

60. Desta, AA, Kulkarni, U, Abraha, K, Worku, S, and Sahle, BW. Iodine level concentration, coverage of adequately iodized salt consumption and factors affecting proper iodized salt utilization among households in North Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr. (2019) 5:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40795-019-0291-x

61. Obssie, GF, Ketema, K, and Tekalegn, Y. Availability of adequately iodized dietary salt and associated factors in a town of Southeast Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional survey. J Nutr Metab. (2020) 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2020/1357192

62. Tahir, A, Seyoum, B, and Kadir, H. Use of iodized salt at household level in jig Jiga town, Eastern Ethiopia. Asian J Agric Life Sci. (2016) 1:18–24.

63. Makate, M, and Nyamuranga, C. The long-term impact of education on dietary diversity among women in Zimbabwe. Rev Dev Econ. (2023) 27:897–923. doi: 10.1111/rode.12980

64. Neelon, M, Price, N, Srivastava, D, Zheng, L, and Trzesniewski, K. Association between educational attainment and EFNEP participants’ food practice outcomes. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2022) 54:902–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2022.06.001

65. Roba, AA, Tola, A, Dugassa, D, Tefera, M, Gure, T, Worku, T, et al. Antenatal care utilization and nutrition counseling are strongly associated with infant and young child feeding knowledge among rural/semi-urban women in the Harari region, eastern Ethiopia. Front Pediatr. (2022) 10:10. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.1013051

66. Wakwoya, EB, Belachew, T, and Girma, T. Effects of intensive nutrition education and counseling on nutritional status of pregnant women in east Shoa zone, Ethiopia. Front Nutr. (2023) 10:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1144709

67. Asmuniati, L, Herawati, DMD, and Djais, JTB. The impact of nutritional Counseling on nutritional knowledge and energy intake among obese children in junior high school. Althea Med J. (2019) 6:107–9. doi: 10.15850/amj.v6n3.1645

68. Abd-El Mohsen, SA, and Mohamed, AA. Effect of nutritional Counseling on nutritional practices and dietary health habits of pregnant women. Am J Nurs Res. (2019) 7:947–51. doi: 10.12691/ajnr-7-6-6

69. Takano, M . Pathogenesis and pathology of defecatory disturbances. Japan Med Assoc J. (2003) 46:9, 367–372.

70. Zelalem, T, Mikyas, A, and Erdaw, T. Nutritional knowledge, attitude and practices among pregnant women who attend antenatal care at public hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int J Nurs Midwifery. (2018) 10:81–9. doi: 10.5897/IJNM2017.0289

71. Gezimu, W, Bekele, F, and Habte, G. Pregnant mothers’ knowledge, attitude, practice and its predictors towards nutrition in public hospitals of southern Ethiopia: a multicenter cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. (2022) 10:205031212210858. doi: 10.1177/20503121221085843

72. Kruglanski, AW, Jasko, K, Milyavsky, M, Chernikova, M, Webber, D, Pierro, A, et al. All about cognitive consistency: a reply to commentaries. Psychol Inq. (2018) 29:109–16. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2018.1480656

Keywords: essential nutrition action, practice, mothers, children, Konso zone, Ethiopia

Citation: Kasse T, Aschalew Z, Desalegn N, Jebero Z, Moga F and Haile A (2024) Practice of key essential nutrition action messages and associated factors among mothers of children aged six months to two years old in Karat town, Konso zone, South Ethiopia, 2024: a community-based cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health. 12:1422203. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1422203

Edited by:

Qi Zhang, Old Dominion University, United StatesReviewed by:

Marilyn Bartholmae, Eastern Virginia Medical School, United StatesHalah Eldoseri, Old Dominion University, United States

Futun Alkhalifah, Old Dominion University, United States,in collaboration with reviewer HE

Copyright © 2024 Kasse, Aschalew, Desalegn, Jebero, Moga and Haile. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tsehaynew Kasse, dHNlaGF5bmV3a2Fzc2VAZ21haWwuY29t

Tsehaynew Kasse

Tsehaynew Kasse Zeleke Aschalew

Zeleke Aschalew Zenebe Jebero

Zenebe Jebero Fikre Moga

Fikre Moga Addisalem Haile

Addisalem Haile