- Health and Education Section, Division for Peace and Sustainable Development, Education Sector, UNESCO, Paris, France

The reciprocal relationship between education and health is well-established, emphasizing the need for integrating health, nutrition, and well-being components into educational sector planning. Despite widespread acknowledgment of this need, countries lack concrete measures to achieve this integration. We examine challenges that countries have faced and the progress they have made in integrating these components into education sector plans and review the extent to which existing educational planning guidelines and tools address health and well-being. The review reveals a significant underrepresentation of health, well-being, and related themes in existing educational planning frameworks. Recent tools and frameworks developed to support a more holistic approach to education have not yet been widely adopted in standard education sector planning processes. The implementation of such approaches remains inconsistent, with significant barriers including limited cross-sectoral collaboration, lack of capacity, and insufficient funding, among others. Addressing these gaps requires improved guidance, technical support, and a multisectoral approach to education planning that includes health, nutrition, and well-being as fundamental components of foundational learning, supported by political commitment, capacity, and adequate financing.

Introduction

The nexus between education and health has been extensively studied and firmly established (1). Children and adolescents who are healthy, well-nourished, engage in regular physical activity, and study in a safe environment learn better (2–5). Conversely, educational attainment has a predominantly beneficial effect on a broad spectrum of health outcomes (6). Recognizing this reciprocal relationship, it is now rare to encounter a country that has not adopted school health and nutrition (SHN) policies or provided health services in school settings at some level (7). The unprecedented school closures triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic have not only clarified the connections between health, well-being, and learning but have also emphasized the critical role of schools in ensuring educational continuity as well as in supporting physical health and addressing emotional and mental health challenges.

Building upon this understanding, the 2022 Transforming Education Summit (TES) has brought to light the global commitment to addressing these challenges and transforming education. Analysis of 143 national statements of commitment post-TES reveals a widespread acknowledgment of the need to support students’ and teachers’ psycho-social and mental well-being, with nearly 60% of countries advocating for enhanced physical and mental health and safety measures (84 out of 143 countries) (8, 9). This analysis serves as a crucial barometer for understanding global education sector priorities and commitments toward integrating health and well-being in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Despite the clear recognition of these needs, very few countries have articulated concrete measures to achieve them (8). This gap between commitment and implementation underscores the urgency for the school health community, United Nations, and development partners to provide support in actualizing this vision. Education stakeholders may see health and well-being as competing with other pressing priorities, such as the need to respond to learning poverty.1 A key role for UNESCO and its partners is to demonstrate how health and well-being are also fundamental aspects of learning and can be part of an approach that supports foundational learning2 through a holistic understanding of learners’ needs. This involves advocacy, but importantly, it also involves improving the guidance and provision of technical support on how to achieve these goals in practice.

Challenges and progress in integrating health and well-being in education planning

Countries are increasingly considering how to transform their education systems and integrate health and well-being, albeit at varying levels, influenced by national context and priorities. Pioneering approaches in Kenya and Indonesia demonstrate the effectiveness of a unified government strategy involving multiple line ministries, including education, health, and home affairs, to promote inclusive education through comprehensive SHN programs (12). From 2000 to 2015, Sub-Saharan Africa saw a notable rise in health and nutrition interventions within education sector plans (ESPs) (13).

However, this progress has been uneven, with varying coverage and implementation. Country-specific analyses have shown diverse levels of SHN policies and interventions, often aimed at promoting equity and inclusion (14, 15). Some examples from diverse regions illustrate this variation: In Egypt, the 2023–2027 ESP recognizes the constrained resources for school feeding, water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) as an important barrier. Nepal’s 2022/23–2031/32 ESP includes strategies for basic health and nutrition services, WASH, and addressing abuse, discrimination, and bullying. Liberia’s 2022/23–2026/27 ESP provides for skill-based health education through girls’ clubs, nutrition services, and reducing gender-based violence. The level of ambition in relation to school health and well-being is evident, but all three plans also highlight significant financing gaps.

For many such countries attempting to address health and well-being in schools, questions remain about the feasibility of interventions reaching national coverage. Often, the evidence basis for interventions is unclear; they are relatively small in scale and are insufficiently funded. Many plans lack an overall theory of change or references to globally established definitions and frameworks (14). Cooperation between sectors and human resource capacity is often not in place to implement these plans (15). Deficiencies in strategic planning knowledge and skills and low levels of stakeholder engagement prevent these intersectoral planning processes from working as intended (16).

Gaps in existing educational planning tools and processes

In the education sector, a number of tools have played an essential role in supporting analysis and planning. Developed primarily between 2014 and 2021, these include the Guidelines for Education Sector Plan Preparation (17) and the Education Sector Analysis methodological guidelines (18–20).

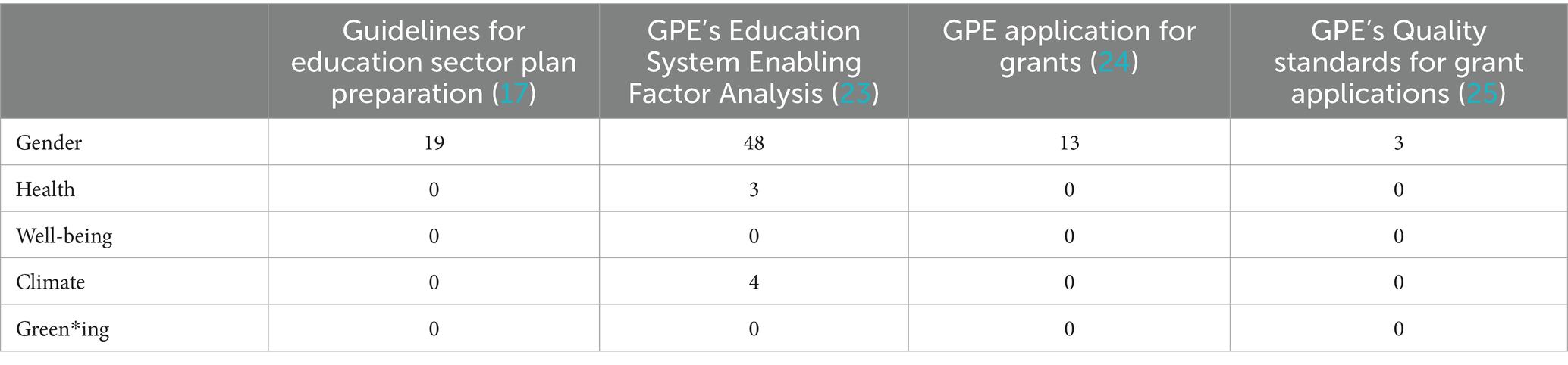

Despite their wide usage and appreciation within the global education sector, these tools do not yet provide the support that countries need when it comes to health and well-being. In particular, recent work recognizes the transformative potential of education – to empower learners to make informed decisions and take actions concerning their health, nutrition, well-being, global citizenship, and issues such as climate change and peace (21, 22). A keyword analysis reveals a stark underrepresentation of these essential themes and the need for cross-sectoral work in education sector planning tools and in guidelines such as those produced by the Global Partnership for Education (GPE), indicating a significant disconnect between current educational strategies and evolving global challenges (Table 1).

These documents primarily emphasize ‘traditional’ education metrics such as enrolment and internal efficiency, and discussions on ‘health’ are often confined to screening and health service provision (18). They do not incorporate the more recent specialized tools designed to help countries and education systems collect data, assess the status of their policies and practices, and identify areas for improvement in order to promote learners’ health, safety, and well-being. The following sections describe some of these tools, with suggestions on how they can be used more effectively.

New tools to help bridge the gap

Since the early 2000s, many new tools have been developed, often the result of burgeoning cooperation among international organizations in this arena. Specifically, there are now multiple (i) frameworks and guidelines, (ii) policy diagnostic tools, (iii) evidence reviews, (iv) survey instruments, and (v) global data sources that can support this work.

Key frameworks include Focusing Resources on Effective School Health (FRESH), launched by UNESCO, UNICEF, WHO, and the World Bank during the World Education Forum, Dakar, in April 2000 (26). FRESH is an intersectoral framework for promoting educational success, health, and development of school-age children and adolescents and has expanded over time to generate a set of linked diagnostic tools for analysis of topics, such as how contexts may support or undermine school health, the status of evidence generation in each country, what resources are committed to school health, and the prioritization of specific policy areas or programs.

Under its Systems Approach for Better Education Results (SABER) initiative, the World Bank drew on FRESH to produce ‘What Matters Most for School Health and School Feeding’ (27), presenting a conceptual framework, a set of policy goals, and guidance around the trade-offs that may be involved in implementing school health and school feeding. Health-promoting schools—a long-standing whole-school approach capitalizing on the potential of schools to foster the physical, social–emotional, and psychological conditions for better health as well as educational attainment—has been advanced in recent years with the development of a set of global standards and indicators, to support governments in embedding the approach in all aspects of education systems (28).

Such frameworks are needed in education sector planning to ensure that the analysis of health in education, dialog and consultation around it, and the planned policy and program responses are holistic and coherent, reflecting a suitable level of ambition in terms of education and health interventions that mutually support each other. In addition, standards and indicators have recently been developed around specific areas, such as sexuality education (29, 30) and safety from violence in and around schools (31). Frameworks for ending violence against children include INSPIRE and Safe to Learn (32, 33), and the INSPIRE toolkit includes specific and extensive guidance on implementation, adaptation, scale-up, and results indicators (34–36). These help planners design concrete and consistent sets of activities.

Policy diagnostic tools guide policymakers and planners through analyzing the components of school health and well-being to reach a better understanding of what the barriers are, the strengths and weaknesses of current policies and programs, and what adaptations and new resources might be needed to make faster progress. These are particularly important for education sector analysis at the start of a planning cycle. Such tools are often linked to the frameworks listed above, as is the case for those developed as part of SABER, FRESH, Safe to Learn (37), and the Sexuality Education Review and Assessment Tool (SERAT) (38). UNICEF (39) developed a checklist tool for promoting effective and equitable learning recovery following COVID-19 school shut-downs, which includes consideration of services to meet children’s learning, health, nutrition, psycho-social well-being, and other needs through cross-sectoral collaboration and to ensure protection, safety and referral systems.

In many countries, education reforms focused on health and nutrition will involve new areas of programming, and countries will need to review practices that have been effective globally and adapt these to local contexts. A number of global evidence reviews now exist to support this process, consolidating the best available global evidence on interventions in relation to school health and well-being. Systematic reviews of interventions to improve access to and learning in school have analyzed the impacts of school-based health and nutrition programs (40). A volume in the Disease Control Priorities series presented the latest evidence on high-return investments in school health and proposed a package of interventions for countries to consider implementing (41). The INSPIRE guidelines developed by WHO, UNICEF, and others (32) propose seven strategies for ending violence against children and document the evidence and country cases for each strategy.

Survey instruments have been developed that improve our understanding of the health and well-being of school-age children and adolescents and the extent to which their home and school environments promote better health. Where these have already been carried out, they can inform education sector analysis, but many countries may need to enhance their existing routine data collection as part of their education management information systems (EMIS), and sometimes as monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for new programs.

Major international household survey initiatives, such as Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS), and the World Bank-supported Living Standards Measurement Surveys (LSMS), have long collected data on health, immunization, water, sanitation, hygiene, food security, stunting, and early childhood development; and relatively recent additions cover aspects such as child discipline and disability in standardized formats. The Global School-Based Student Health Survey (42) measures and assesses the behavioral risk factors and protective factors related to the leading causes of morbidity and mortality among students, while the Violence Against Children and Youth Survey (43) measures physical, emotional, and sexual violence against children and youth up to age 24, both in and outside of school.

Facility-based surveys include the Global School Health Policies and Practices Survey (44), which asks head teachers about health services, the physical environment, food and nutrition, health education, physical education, governance and leadership, and school policies and resources. The Brief Early Childhood Quality Inventory (45)—a checklist for analyzing the quality of early childhood development centers—also incorporates items on clean and safe environments and physical punishment. While most countries have conducted at least some of these surveys, low and middle-income countries continue to struggle with insufficient recent data for analysis and planning.

Global data sources enable countries and international partners to rapidly access the results from these surveys and compare them across countries. These are important tools for national education sector analysis, allowing countries to understand how they stand in relation to comparator countries, and helping global actors shape their support.

The UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) tracks the indicators for Sustainable Development Goal 4, including the number of young children who are developmentally on track in health, learning and psycho-social development; the extent to which global citizenship education and education for sustainable development are mainstreamed in national education policies; the percentage of schools providing life skills-based HIV and sexuality education; percentage of students showing understanding of global citizenship and sustainability; the percentage of students showing proficiency in environmental science or geoscience; proportion of schools with access to water, sanitation and hygiene facilities; bullying; and, attacks on students, personnel and institutions. However, the availability of data on these indicators remains limited in many cases. The annual Global Education Monitoring Report tracks progress on the full range of education indicators around the world, while Ready to Learn and Thrive (7) summarizes the data that are available on SHN and highlights the many gaps that remain.

UNICEF’s Foundational Learning Action Tracker tracks the number of countries implementing nationwide policy measures to improve foundational learning, including the development of psycho-social support and well-being (46). The school violence dataset developed by the Center for Global Development (47) brings together DHS, VACS, and several other sources to document the extent and nature of school violence around the world. The creators of this dataset highlight that, despite an increasingly large number of surveys collecting information on violence, most counties still lack actionable data to address school-related violence.

Together, these tools and resources represent a growing body of work that can support national policymakers and their international partners in incorporating health and well-being into their education sector planning. The resources highlight many of the gaps in data and evidence that remain. However, filling these gaps should in itself be part of the cross-sectoral planning and evidence-informed policymaking processes, and many of the instruments and frameworks needed to do so already exist.

Discussion

The frameworks, guidelines, tools, evidence reviews, diagnostics, and data sources listed above, most of which are relatively recent, fill important gaps in the ability of countries to improve health and well-being in schools. The tools can be brought in at each stage in the education sector planning cycle (17):

• Education sector analysis can increasingly draw on data from new surveys, diagnostic tools, and global sources.

• Prioritization and consultation exercises can use health and education frameworks to ensure a holistic dialog, reflecting the potential for mutual benefit across the two sectors and help delineate responsibilities between different actors in the sectors.

• Program design and implementation planning can use the same frameworks to ensure a coherent and comprehensive response, both for the sector as a whole and for specific areas of intervention, such as WASH or sexuality education, and can draw on new evidence reviews to form appropriate responses to health and education challenges.

• Monitoring and evaluation of education programs can use the new frameworks and evidence reviews to develop theories of change and can use the new survey instruments and diagnostic tools to develop indicators and standards to measure progress.

However, these tools have not yet been integrated into the standard tools and processes of international support to education sector planning and may be difficult for education planners to put into practice. To address this, it is essential to develop a clear implementation strategy, which includes a commitment by the UN and development partners to create a comprehensive handbook that consolidates all frameworks, tools, and evidence reviews. This handbook should be made available to education sector planners in countries and promoted by development partners, UN organizations, and GPE. Building local capacity within the relevant departments of the ministries is imperative, ensuring education sector planners are trained on the use of these tools. Additionally, establishing a support network for cross-country learning and technical support, where countries can share experiences and best practices, is crucial.

The tools vary in their scope from the specific to the holistic, but it is essential that they be seen as part of a wider, holistic vision of transformative education—education that supports learners’ health, well-being, and understanding of sustainable development, peace, and citizenship. Such a vision provides a framing that can bring together these diverse elements and help education planners build them into a cohesive strategy. Moreover, it is essential for the wider vision to articulate how health and well-being are essential to foundational learning and ending ‘learning poverty’. The recent Commitment to Action on Foundational Learning, endorsed by many governments and international organizations, does this, recognizing the need to support the health, nutrition, and psycho-social well-being of every teacher and child and, in turn, recognizing how foundational learning contributes to productive citizenship, sustainable development, gender equality and other national goals (10, 11, 48).

A core aspect of this transformative vision is for education sector planning and policymaking to become more multisectoral, drawing in health, community development, and other social sectors to support child development. The need for deeper cross-sectoral coordination and engagement of other sectors in education sector planning has long been recognized, particularly for early childhood development programming (49), yet remains an aspiration in many cases.

Regardless of the availability of frameworks and tools, their impact will be limited if stakeholders, particularly donors and development partners, do not actively utilize them in their support to countries. There is a risk that external assistance remains driven by each donor’s priorities rather than the needs identified in the evidence generated within each country. This could potentially hinder the effective implementation of a comprehensive school health agenda, deviating from a truly learner-centered model.

The development of a better and more integrated set of tools does not in itself guarantee better policy or practices on health and well-being in schools. Many governments, in particular the education authorities, will need direct technical support or training to make the best use of these tools, backed up by mechanisms for cross-country support and learning, and a coherent framework is needed to guide the different international bodies offering this support. The integration of evidence into policymaking and planning involves a complex process in which political, ideological, and economic factors all play a role (50, 51). A supportive political economy and domestic financing, in particular, will be necessary in the longer term to sustain financing for school health programs. Showing that there is already a strong global evidence base for such programs and coherent, integrated technical guidance on how they can be put into practice is an essential foundation for such political and financial resources to be mobilized.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AI: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CC: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work is supported by the Governments of Norway and Sweden through their pooled contributions to UNESCO’s special account for Health and Well-being. The funder did not play a role in the design of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Learning poverty means being unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10 (10).

2. ^Foundational learning refers to basic literacy, numeracy, and transferable skills such as socio-emotional skills (11).

References

1. Eide, ER, and Showalter, MH. Estimating the relation between health and education: what do we know and what do we need to know? Econ Educ Rev. (2011) 30:778–91. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.03.009

2. Basch, CE . Healthier students are better learners: a missing link in school reforms to close the achievement gap. J Sch Health. (2011) 81:593–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00632.x

3. Owen, KB, Parker, PD, Astell-Burt, T, and Lonsdale, C. Regular physical activity and educational outcomes in youth: a longitudinal study. J Adolesc Health. (2018) 62:334–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.09.014

4. Viner, RM, Ozer, EM, Denny, S, Marmot, M, Resnick, M, Fatusi, A, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. (2012) 379:1641–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4

5. Bond, L, Butler, H, Thomas, L, Carlin, J, Glover, S, Bowes, G, et al. Social and school connectedness in early secondary school as predictors of late teenage substance use, mental health, and academic outcomes. J Adolesc Health. (2007) 40:357.e9–357.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.013

6. Hamad, R, Elser, H, Tran, DC, Rehkopf, DH, and Goodman, SN. How and why studies disagree about the effects of education on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of compulsory schooling laws. Soc Sci Med. (2018) 212:168–78. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.016

7. UNESCO, UNICEF, World Food Programme . Ready to learn and thrive: school health and nutrition around the world. UNESCO (2023). Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000384421 (Accessed March 18, 2023).

8. UNESCO . Analysis of National Statements of commitment, transforming education summit. (2022). Available at: https://transformingeducationsummit.sdg4education2030.org/system/files/2022-12/Analysis%20of%20TES%20National%20Statements%20of%20Commitment_23.10.2022_FINAL.pdf (Accessed March 18, 2023).

9. Dashboard of Country Commitments and Actions to Transform Education. Available at: https://www.unesco.org/sdg4education2030/en/knowledge-hub/dashboard?TSPD_101_R0=080713870fab2000ed3b3b0dcb3a6ecf96b57a8cda43bbc20f25cb9b883b30d1e481e4e10fbe60f20841601ab6143000832951b91fe142880eb13471e8bb798903cd68e3748ebe1af8bc41ea549a60fd6b51c56915d518ad7b8f3db027cc80ec (Accessed March 23, 2024)

10. World Bank . Brief: Ending Learning Poverty. (2022). Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/brief/ending-learning-poverty#:~:text=Learning%20poverty%20means%20being%20unable,simple%20text%20by%20age%2010 (Accessed March 28, 2024).

11. UNICEF . Commitment to Action on Foundational Learning-Ensure foundational learning as a key element to transform education. (2022). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/learning-crisis/commitment-action-foundational-learning#commitment (Accessed March 28, 2024)

12. Bundy DAP, World Bank ed. Rethinking school health: A key component of education for all. Washington, DC: World Bank (2011). 299 p.

13. Sarr, B, Fernandes, M, McMahon, B, Peel, F, and Drake, L. The evolution of school health and nutrition in the education sector 2000–2015 in sub-Saharan Africa. Front Public Health. (2017) 4:271. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00271

14. Shahraki-Sanavi, F, Rakhshani, F, Ansari-Moghaddam, A, and Mohammadi, M. A study on school health policies and programs in the southeast of Iran: a regression analysis. Electron Physician. (2018) 10:7132–7. doi: 10.19082/7132

15. Fathi, B, Allahverdipour, H, Shaghaghi, A, Kousha, A, and Jannati, A. Challenges in developing health promoting schools’ project: application of global traits in local realm. Health Promot Perspect. (2014) 4:9–17. doi: 10.5681/hpp.2014.002

16. Bantilan, JC, Deguito, PO, Otero, AS, Regidor, AR, and Junsay, MD. Strategic planning in education: a systematic review. Asian J Educ Soc Stud. (2023) 45:40–54. doi: 10.9734/ajess/2023/v45i1976

17. UNESCO, IIEP, GPE . Guidelines for education sector plan preparation. IIEP; (2015). Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000233767/PDF/233767eng.pdf.multi (Accessed March 18, 2023).

18. UNESCO IIEP Dakar, Africa Office, World Bank, UNICEF . Education sector analysis: methodological guidelines. Volume 1: sector-wide analysis, with emphasis on primary and secondary education. Dakar: International Institute for Educational Planning (2014).

19. UNESCO IIEP Dakar, Africa Office, World Bank, UNICEF . Education sector analysis methodological guidelines: Volume 2: Sub-sector specific analysis. Paris: UNESCO/World Bank/UNICEF/Global Partnership for Education (2014).

20. UNESCO IIEP Dakar, Africa Office, UNICEF, Global Partnership for Education, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office . Education sector analysis: methodological guidelines. Volume 3: Thematic analyses. Dakar: International Institute for Educational Planning (2014).

21. UNESCO . Reimagining our futures together: a new social contract for education. (2021). Available at: https://unevoc.unesco.org/pub/futures_of_education_report_eng.pdf (Accessed March 18, 2024)

22. UNESCO . 5th UNESCO forum on transformative education for sustainable development, global citizenship, health and well-being. Recommendations for action towards transformative education. UNESCO; (2022). Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381592/PDF/381592eng.pdf.multi (Accessed March 23, 2024).

23. GPE . Enabling factors screening questionnaire and analysis. GPE; (2023). Available at: https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/enabling-factors-screening-questionnaire-and-analysis (Accessed March 23, 2024)

24. GPE . Application form for GPE grants. GPE; (2024). Available at: https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/application-form-gpe-grants (Accessed March 23, 2024)

25. GPE . Quality standards for the assessment of system transformation grants and multiplier programs. GPE; (2023). Available from: https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/quality-standards-assessment-system-transformation-grants-and-multiplier-programs (Accessed March 23, 2024)

26. Joerger, C, and Hoffmann, AM. FRESH: A comprehensive school health approach to achieve EFA. UNESCO, 2002 on behalf of FRESH Initiative. (2002).

27. World Bank . What matters most for school health and school feeding: A framework paper. (2012). Available at: http://wbgfiles.worldbank.org/documents/hdn/ed/saber/supporting_doc/Background/SHN/Framework_SABER-School_Health.pdf (Accessed March 18, 2024).

28. WHO, UNESCO, UNICEF, WFP . Making every school a health-promoting school: Implementation guidance. (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025073 (Accessed March 18, 2024).

29. UNESCO . International technical guidance on sexuality education: an evidence-informed approach for schools, teachers and health educators. (2009). Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000183281 (Accessed March 22, 2024)

30. Herat, J, Plesons, M, Castle, C, Babb, J, and Chandra-Mouli, V. The revised international technical guidance on sexuality education - a powerful tool at an important crossroads for sexuality education. Reprod Health. (2018) 15:185. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0629-x

31. UNESCO and UN Women . Global guidance on addressing school-related gender-based violence. Paris: UNESCO (2016).

32. World Health Organization . INSPIRE: Seven strategies for ending violence against children. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016). 108 p.

33. Safe to learn . Safe to learn during COVID-19: recommendations to prevent and respond to violence against children in all learning environments. (2020). Available at: https://www.end-violence.org/sites/default/files/paragraphs/download/STL%20COVID%2019%20response%20Key%20messages_%20%28002%29.pdf (Accessed March 18, 2024).

34. INSPIRE Working Group . INSPIRE guide to adaptation and scale up. WHO; (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/inspire-guide-to-adaptation-and-scale-up (Accessed March 25, 2024)

35. UNICEF . INSPIRE Indicator Guidance and Results Framework. (2018). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/inspire-indicator-guidance-and-results-framework (Accessed March 25, 2024)

36. World Health Organization . INSPIRE handbook: action for implementing the seven strategies for ending violence against children. Geneva: World Health Organization (2018).

37. Safe to Learn . Safe to learn diagnostic tool. Safe to Learn; (2021). Available at: https://www.end-violence.org/sites/default/files/paragraphs/download/Safe%20to%20Learn%20Diagnostic%20Toolkit%202021_0.pdf (Accessed March 18, 2024).

38. UNESCO . Sexuality education review and assessment tool (SERAT). (2020). Available at: https://healtheducationresources.unesco.org/library/documents/sexuality-education-review-and-assessment-tool-serat (Accessed March 22, 2024)

39. UNICEF . Checklist of key considerations to promote effective and equitable learning recovery. (2022). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/media/115711/file/Checklist%20of%20Key%20Considerations%20.pdf (Accessed March 22, 2024)

40. Snilstveit, B, Stevenson, J, Menon, R, Phillips, D, Gallagher, E, Geleen, M, et al. The impact of education programmes on learning and school participation in low-and middle-income countries 3ie; (2016). Available at: http://www.3ieimpact.org/media/filer_public/2016/09/20/srs7-education-report.pdf (Accessed March 23, 2024).

41. Bundy, DAP, de Silva, N, Horton, S, Jamison, DT, and Patton, GT. Optimizing education outcomes: high-return Investments in School Health for increased participation and learning. 3rd ed. Washington, D.C: World Bank (2018).

42. WHO . Global school-based student health survey (GSHS). Available at: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/global-school-based-student-health-survey (Accessed March 23, 2024)

43. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention . Towards a violence-free generation: violence against children surveys (VACS). (2017).

44. WHO . Global school health policies and practices survey (G-SHPPS). Available at: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/global-school-health-policies-and-practices-survey (Accessed March 23, 2024)

45. Raikes, A, Koziol, N, Davis, D, and Burton, A. Measuring quality of preprimary education in sub-Saharan Africa: evaluation of the measuring early learning environments scale. Early Child Res Q. (2020) 53:571–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.06.001

46. UNICEF and Hempel Foundation . Tracking progress on foundational learning | UNICEF. (2023). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/reports/tracking-progress-foundational-learning-2023 (Accessed March 22, 2024)

47. Smarelli, G, Wu, D, Evans, D, and Hares, S. Introducing a new dataset of datasets: where, when, and how much data exists on school violence. Center For Global Development (2023). Available at: https://www.cgdev.org/blog/introducing-new-dataset-datasets-where-when-and-how-much-data-exists-school-violence (Accessed March 18, 2024)

48. UNICEF . Briefing note: commitment to action for foundational learning. (2022). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/media/126926/file (Accessed March 23, 2024).

49. Vegas, E, and Santibáñez, L. The promise of early childhood development in Latin America and the Caribbean. World Bank Publ-books. (2010); Available at: https://ideas.repec.org//b/wbk/wbpubs/9385.html (Accessed March 28, 2024)

50. Strydom, W, Funke, N, Nienaber, S, Nortje, K, and Steyn, M. Evidence-based policymaking: a review. South Afr J Sci. (2010) 106:8. doi: 10.4102/sajs.v106i5/6.249

Keywords: education, school, cross-sectoral planning, school health, school nutrition, well-being, child health, adolescents

Citation: Abduvahobov P, Cameron SJ, Ibraheem A, Herat J and Castle C (2024) The need for stronger international support to integrate health and well-being and transform education: a perspective on developing countries. Front. Public Health. 12:1415992. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1415992

Edited by:

Samrat Singh, Imperial College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Samuel Honório, Polytechnic Institute of Castelo Branco, PortugalCopyright © 2024 Abduvahobov, Cameron, Ibraheem, Herat and Castle. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Parviz Abduvahobov, cC5hYmR1dmFob2JvdkB1bmVzY28ub3Jn

Parviz Abduvahobov

Parviz Abduvahobov Stuart J. Cameron

Stuart J. Cameron Ayodeji Ibraheem

Ayodeji Ibraheem Joanna Herat

Joanna Herat