- 1Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Liyang People's Hospital, Liyang, China

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Liyang People's Hospital, Liyang, China

Background: Nurse burnout is a prevalent issue in healthcare, impacting both nurses’ well-being and patient care quality. This cross-sectional study examined the association between humor styles and nurse burnout.

Methods: A total of 244 nurses in China completed an online self-report measure to assess their humor styles and burnout levels using the Humor Styles Questionnaire (HSQ) and the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS). Spearman correlation analysis and stepwise regression analysis were conducted.

Results: The results showed that affiliative and self-enhancing humor were moderately used, while aggressive and self-defeating humor were rated low among the nurses. Emotional exhaustion was moderate, depersonalization was severe, and personal accomplishment was low. Correlation analyses uncovered significant relationships between humor styles and burnout dimensions. Self-enhancing humor exhibited negative correlations with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, while aggressive and self-defeating humor styles displayed positive correlations with these burnout factors. Affiliative humor was also negatively correlated with depersonalization. Additionally, self-enhancing humor was positively correlated with personal accomplishment, whereas aggressive humor showed negative correlations with this dimension of burnout. Stepwise regression analysis revealed that self-defeating humor positively predicted emotional exhaustion while self-enhancing humor negatively predicted it. Aggressive humor positively predicted depersonalization, and affiliative and self-enhancing humor also positively predicted this dimension of burnout. Self-enhancing humor positively predicted personal accomplishment, while aggressive and self-defeating humor negatively predicted this dimension.

Conclusion: The findings highlighted the importance of considering different types of humor in understanding the various dimensions of nurse burnout. The use of self-defeating and aggressive humor appears detrimental, while the use of self-enhancing humor may be beneficial in mitigating burnout among nurses.

1 Introduction

Humor is a complex and multifaceted construct that has been extensively studied in various fields, including psychology, sociology, pedagogy, and medicine (1–4). It is defined as a cognitive and emotional response characterized by amusement and laughter, involving mental processes designed to create and perceive comic stimuli (5, 6). Humor can be understood as any message designed to evoke smiles or laughter, conveyed through action, speech, writing, images, or music (7, 8). The production of humor involves a complex interplay of psychological and cognitive processes, including emotional, cognitive, and value judgments (9). Humor can be classified into various forms, such as jokes, satire, irony, hyperbole, and stereotypes, each with its own unique function and impact (10). While some universal elements of humor exist, the specific expressions and content of humor vary across cultures, often limited by an individual’s cultural background and worldview (11). Several major theories attempt to explain the nature and role of humor, including superiority theory, release theory, incongruity theory, cognitive problems theory, and psychoanalytic perspective (12). Superiority theory suggests that humor stems from feelings of superiority over the weaknesses of others (13), release theory proposes that humor is a release of tension (13), incongruity theory emphasizes the role of inconsistencies between expectations and reality (13), and cognitive-problems theory and psychoanalytic perspectives explain humor in terms of cognitive processing and underlying psychodynamics (12). Additionally, the style of humor is an important aspect of research in this field. One commonly accepted classification is to divide humor into four categories: affiliative humor, which involves using humor to enhance relationships and reduce tension; self-enhancing humor, which involves using humor to cope with stress and maintain a positive outlook; aggressive humor, which involves using humor to enhance one’s status at the expense of others; and self-defeating humor, which involves using humor to gain approval and acceptance from others by putting oneself down (6). Each of these categories is associated with different psychological and behavioral outcomes, and understanding the nuances of each can be critical in workplace settings (14). The use of humor promotes communication, enhances health, helps cope with unpleasant situations, and reduces tension, discomfort, and stress (15). Despite its often positive and adaptive nature, not all humor is beneficial. Affiliative and self-enhancing humor are considered positive humor styles that can promote health, improve social skills, and increase work engagement and well-being (16). Conversely, aggressive and self-defeating humor are considered negative styles, negatively correlated with mental health, and can increase emotional exhaustion and decrease resilience and social competence (17, 18).

Nurse burnout is a persistent and pervasive issue characterized by physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion resulting from prolonged exposure to demanding work environments (19). Current research reveals a concerning prevalence of burnout among nurses, with numerous contributing factors including heavy workloads, understaffing, lack of autonomy, and the emotional strain of caring for patients in distress (20). Additionally, the nature of nursing work, which involves managing high-stress situations and often witnessing suffering and loss, further exacerbates the risk of burnout (21). High levels of burnout symptoms early in a nurse’s life are significantly associated with more frequent symptoms of cognitive dysfunction, depression, and impaired sleep later in life (22). Nurses also face high emotional demands from caring for patients, dealing with patient deaths, and managing complex patient needs, all of which can deplete emotional resources (23). Other factors, such as lack of support from management, role ambiguity, and work-life imbalance, have also been linked to increased burnout among nurses (24, 25). The consequences of nurse burnout are significant, both for individual nurses and the healthcare system as a whole. Burnout has been associated with decreased job satisfaction, increased turnover intentions, and higher rates of absenteeism (26). Burnout can also negatively impact patient care, with studies showing links between nurse burnout and poorer patient outcomes, including increased medical errors and lower patient satisfaction (27, 28). Nurse burnout is a global issue, with high rates reported worldwide. Estimates suggest that up to 30–50% of nurses in the United States experience burnout (29, 30). Similarly, elevated burnout levels have been documented in Europe, with over 25% of nurses in Germany, France, and England reporting high emotional exhaustion (31). High burnout rates, exceeding 30%, have also been reported among nurses in South Korea (32). In China, a nationwide questionnaire survey revealed a burnout rate of up to 50% of nurses (33). While the exact prevalence varies, the widespread nature of nurse burnout across diverse healthcare settings underscores its global significance as a critical challenge facing the nursing profession.

The extant literature has explored the relationship between nurses’ use of various humor styles and their work-related outcomes. Appropriate use of humor can help nurses alleviate work-related stress, foster trusting relationships with patients, and improve patient satisfaction (34). Furthermore, the judicious application of humor by nurses has been found to enhance their job satisfaction and sense of professional pride, ultimately improving the overall quality of nursing care (35). Studies have shown that affiliative and self-enhancing humor styles were strongly associated with higher levels of well-being, sociability, hope, and life satisfaction, while aggressive humor was linked to low life satisfaction and high nursing stress, and self-defeating humor was associated with better health outcomes among nurses (36). However, little literature has comprehensively examined the correlation between different humor styles and nurse burnout (37). The existing literature has predominantly focused on Western samples, with a paucity of research examining these relationships within the unique cultural context of China, where nurse burnout has been particularly problematic (38, 39). Nurses in China often face additional challenges, such as high patient loads, limited resources, and a hierarchical healthcare system, which may contribute to elevated levels of burnout (39). The current study aims to address these gaps in the literature and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between humor styles and the multidimensional construct of burnout in the Chinese cultural context. By examining the association between different humor styles (affiliative, self-enhancing, aggressive, and self-defeating) and the three dimensions of burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment), this study seeks to contribute to the existing knowledge on this topic.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Design

This cross-sectional study was conducted at a tertiary hospital in China, where hospitals are categorized into three grades based on regular government reviews of their overall healthcare capacity and quality. The higher the hospital grade, the greater its overall capacity. The study aimed to explore the characteristics of humor styles and nurse burnout within a single-center cohort and examine the association between them. Our research hypothesis was that positive humor styles, such as affiliative and self-enhancing humor, would be positively associated with nurse burnout, while negative humor styles, such as aggressive and self-defeating humor, would be negatively associated with nurse burnout.

2.2 Participants

The data collection period spanned from June to October 2023, during which an online questionnaire was disseminated to all nursing staff at the hospital through the nursing department. The questionnaire provided a comprehensive overview of the study’s objectives, research methodology, and the requirement for informed consent. The questionnaire was uploaded to an online survey platform named Wen Juan Xing. Before starting the questionnaire, participants were presented with an electronic informed consent form, which explained the purpose of the study, mode of participation, and privacy protection. Participants were required to check “I have read and agree to participate in this study” before proceeding to the formal questionnaire.

2.3 Materials

The Humor Styles Questionnaire (HSQ) is a widely used self-report measure to assess an individual’s humor styles. It has been translated into over 30 languages and validated for reliability (6, 40). The HSQ consists of four subscales: affiliative humor, self-enhancing humor, aggressive humor, and self-defeating humor. The affiliative humor subscale measures the use of humor to enhance relationships and reduce tension, while the self-enhancing humor subscale assesses the use of humor to cope with stress and maintain a positive outlook. The aggressive humor subscale measures the use of humor to enhance one’s own status at the expense of others, and the self-defeating humor subscale assesses the use of humor to ingratiate oneself with others at the expense of oneself. The final Chinese version of the HSQ consists of 25 items, and participants rated each item on a 7-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating a higher degree of humor in a given category. Affiliative humor contains 8 items with scores ranging from 8 to 56, self-enhancing humor contains 5 items with scores ranging from 5 to 35, aggressive humor contains 7 items with scores ranging from 7 to 49, and self-defeating humor contains 5 items with scores ranging from 5 to 35. The scores were grouped as follows: high (affiliative ≥41, self-enhancing ≥26, aggressive ≥35, self-defeating ≥26), moderate (affiliative 25–40, self-enhancing 16–25, aggressive 22–34, self-defeating 16–25), and low (affiliative ≤24, self-enhancing ≤15, aggressive ≤21, self-defeating ≤15).

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) is a widely recognized and extensively used self-report measure specifically designed to evaluate burnout in the workplace, offering tailored versions to suit different industries (41, 42). In this study, the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) version was selected to assess burnout among nurses. The Chinese version of the MBI-HSS utilized in this study consists of 22 items. The emotional exhaustion dimension reflects the depletion of emotional resources and is scored according to the frequency of feelings experienced. It contains 9 items with scores ranging from 0 to 54; the higher the score, the more severe the emotional exhaustion. Similarly, the depersonalization dimension measures apathy and cynicism toward the patient and is scored by assessing the frequency of negative attitudes and reactions. It contains 5 items with scores ranging from 0 to 30; the higher the score, the greater the degree of depersonalization. The personal accomplishment dimension assesses feelings of inefficiency and lack of accomplishment at work. It contains 8 items with scores ranging from 0 to 48, with lower scores indicating a decreased sense of personal accomplishment and a higher degree of burnout. High burnout was defined as emotional exhaustion score ≥27, depersonalization ≥10, and personal accomplishment ≤33; moderate burnout was emotional exhaustion score of 19–26, depersonalization of 6–9, and personal accomplishment 34–39; and low burnout as emotional exhaustion score ≤18, depersonalization ≤5 and personal accomplishment ≥40.

2.4 Data collection

The collected data encompassed three key components: demographic data (including age, gender, work experience, education, technical rank, marital status, and the existence of children), the HSQ, and MBI-HSS.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The study employed descriptive statistics to present the demographic characteristics and scale scores of the participants. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to analyze the reliability of the HSQ and MBI-HSS. Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to assess the presence of common method bias. For qualitative variables, frequencies and percentages were reported, while means and standard deviations were used for quantitative variables. Spearman correlation tests were used to estimate the correlations between variables. Stepwise regression analysis was then performed to identify the predictive power of different humor styles across the three dimensions of nurse burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment). Statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). A two-sided test was used for significance testing, with the significance level set at p < 0.05.

2.6 Ethics statement

In adherence to ethical guidelines, this study followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethical Review Committee of Liyang People’s Hospital (No. LY2023034). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

3 Results

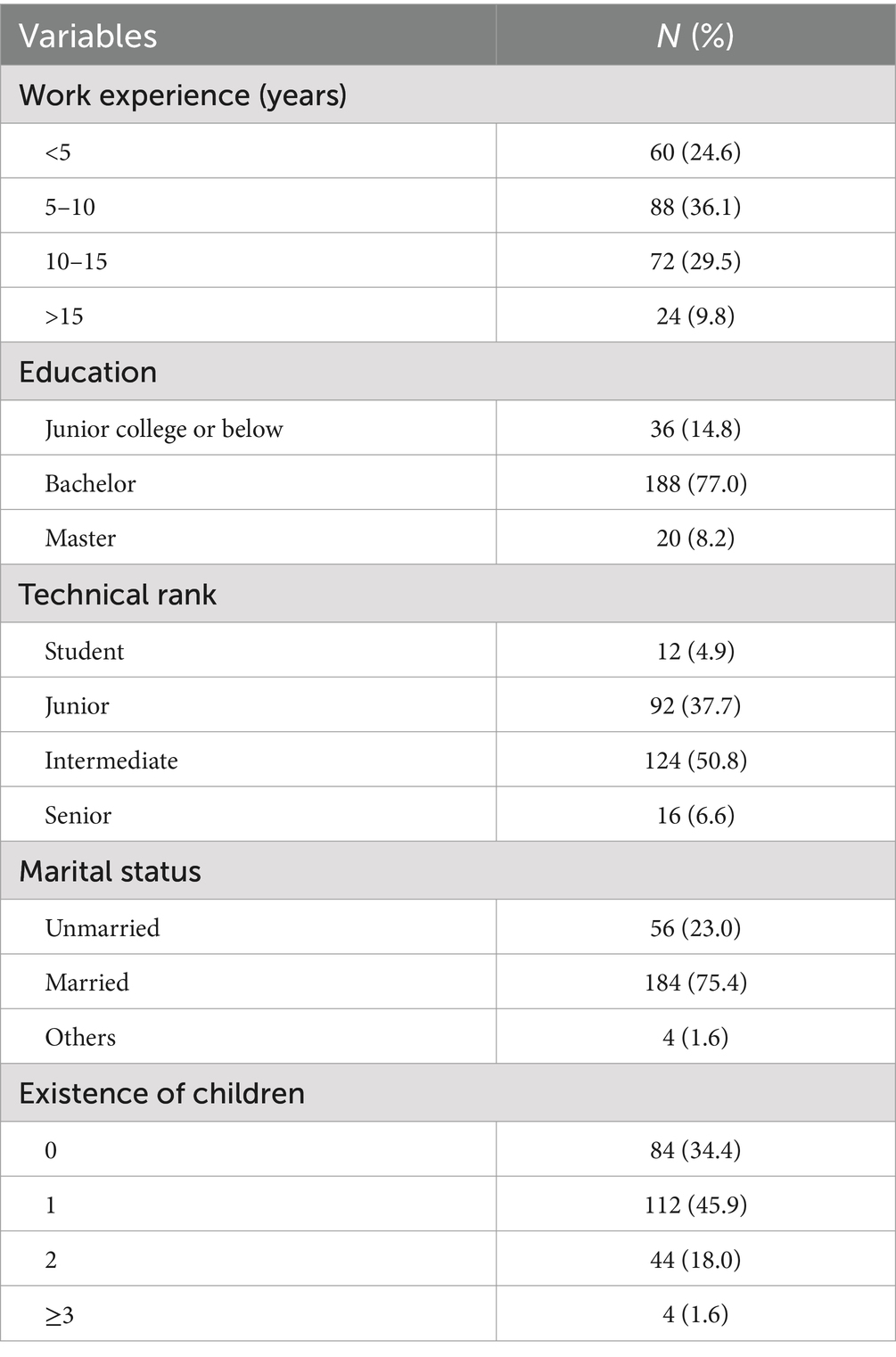

During the study period, a total of 754 nurses were registered at Liyang People’s Hospital, and questionnaires were distributed to all of them. Ultimately, 244 nurses signed the informed consent form and completed the questionnaire items, resulting in a response rate of 32.4%. Among the participants, 242 (99.2%) were female and 2 (0.8%) were male, with ages ranging from 19 to 55 years and a mean age of 31.57 ± 6.57 years. A comprehensive overview of the demographic characteristics is provided in Table 1.

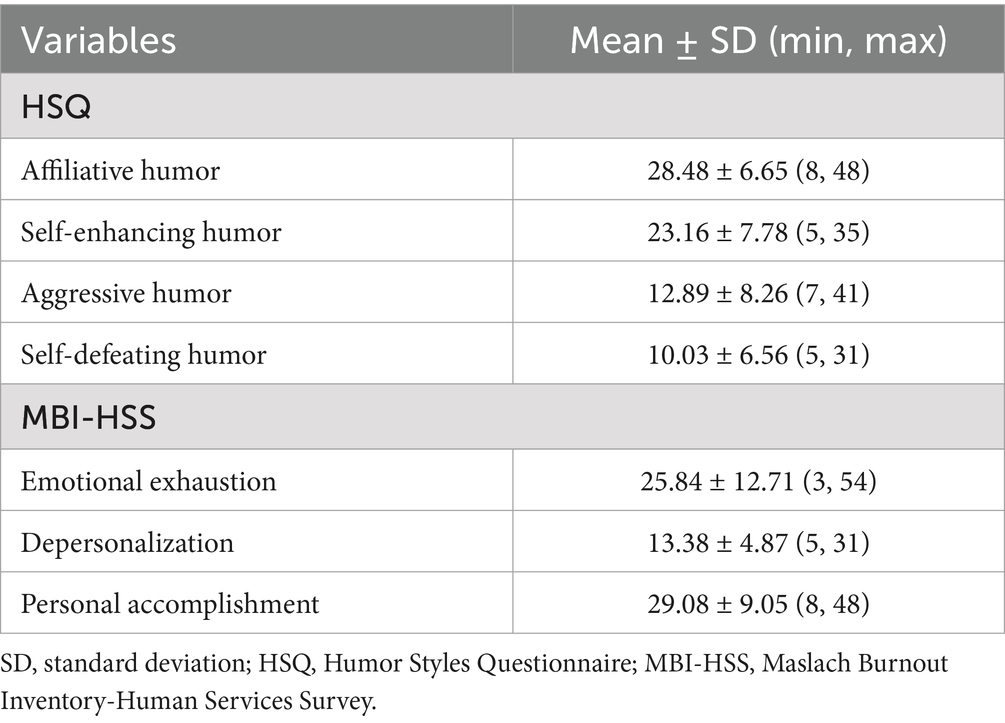

The Harman single-factor test was used to assess common method bias. Factor analysis was performed on all items of the scales, and the first extracted factor had a variance explanation rate of 36.38%, which is less than 40%, indicating that there was no significant common method bias. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the HSQ subscales were 0.87 for affiliative humor, 0.81 for self-enhancing humor, 0.83 for aggressive humor, and 0.78 for self-defeating humor. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the MBI-HSS subscales were 0.89 for emotional exhaustion, 0.81 for depersonalization, and 0.87 for personal accomplishment, indicating good reliability of the instruments. The scores of HSQ and MBI-HSS are summarized in Table 2. Analysis of the HSQ revealed that affiliative and self-enhancing humor were rated as moderate, while aggressive and self-defeating humor were rated as low. In the MBI-HSS, emotional exhaustion was rated as moderate, depersonalization as high, and personal accomplishment as low.

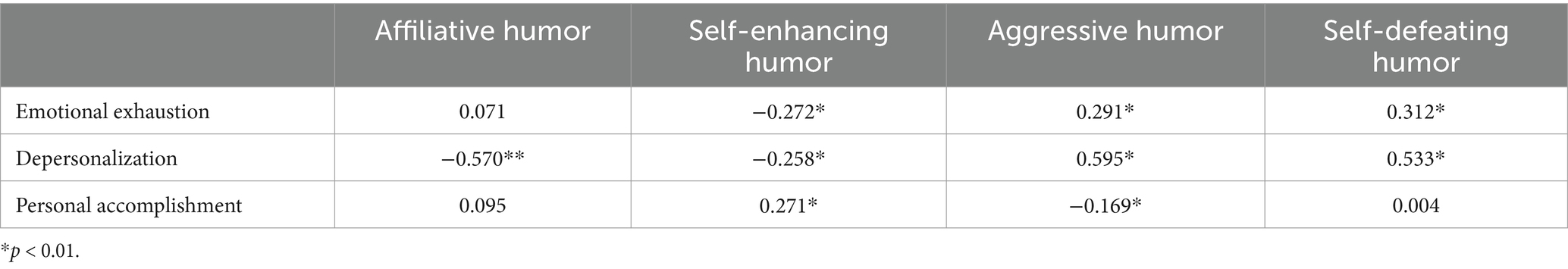

Correlation analysis revealed significant relationships between different humor styles and the three dimensions of the MBI-HSS, as outlined in Table 3. Self-enhancing humor style had significant negative correlations with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, while aggressive and self-defeating humor styles displayed positive correlations with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. Affiliative humor was also found to have a negative correlation with depersonalization. Additionally, self-enhancing humor exhibited a positive correlation with personal accomplishment, while aggressive humor showed a negative correlation with personal accomplishment.

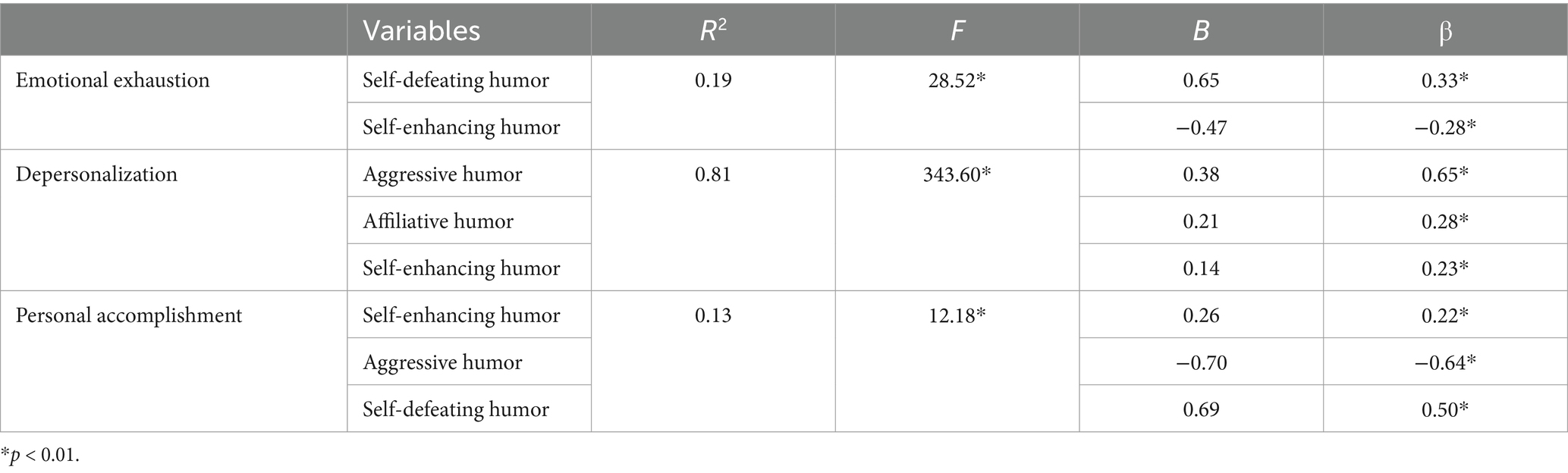

The results of the stepwise regression analysis presented in Table 4 provided insights into the relationship between different types of humor and the three dimensions of nurse burnout. For emotional exhaustion, the model indicated that self-defeating humor positively predicted emotional exhaustion (β = 0.33, p < 0.01), while self-enhancing humor negatively predicted emotional exhaustion (β = −0.28, p < 0.01). Regarding depersonalization, the model showed that aggressive humor positively predicted depersonalization (β = 0.65, p < 0.01), while affiliative humor (β = 0.28, p < 0.01) and self-enhancing humor (β = 0.23, p < 0.01) also positively predicted this dimension of burnout. For personal accomplishment, the model revealed that self-enhancing humor positively predicted personal accomplishment (β = 0.22, p < 0.01), while aggressive humor (β = −0.64, p < 0.01) and self-defeating humor (β = 0.50, p < 0.01) negatively predicted this dimension.

4 Discussion

The present study investigated the correlation between humor styles and nurse burnout among nurses at Liyang People’s Hospital. The response rate of 32.4% indicated a substantial level of participation. The predominance of female nurses in the sample aligns with the gender distribution commonly observed in Chinese nurses (43). Analysis of humor styles using the HSQ indicated moderate scores for affiliative and self-enhancing humor, and low scores for aggressive and self-defeating humor, suggesting a predominance of positive and affiliative humor styles among the nurses. Furthermore, the assessment of burnout levels using the MBI-HSS revealed moderate levels of emotional exhaustion, high levels of depersonalization, and low levels of personal accomplishment. The correlation analysis demonstrated significant relationships between humor styles and burnout dimensions, with specific humor styles showing significant correlations with emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. The results of the stepwise regression analysis suggested that the use of self-defeating humor positively predicted emotional exhaustion while self-enhancing humor negatively predicted it. Regarding depersonalization, the model showed that aggressive, affiliative, and self-enhancing humor positively predicted this dimension of burnout. For personal accomplishment, the model revealed that self-enhancing humor positively predicted this dimension, while aggressive and self-defeating humor negatively predicted it. Overall, the results highlighted the importance of considering different types of humor in understanding the various dimensions of nurse burnout. The use of self-defeating and aggressive humor appears to be detrimental, while the use of self-enhancing humor may be beneficial in mitigating burnout among nurses.

The moderate scores for affiliative and self-enhancing humor styles among the nurses in this study are indicative of a tendency to use humor to foster positive relationships and cope with stress. This aligns with previous research suggesting that affiliative humor can contribute to a supportive and cohesive work environment, potentially serving as a protective factor against burnout (44, 45). Similarly, the moderate prevalence of self-enhancing humor, involving the use of humor to maintain a lighthearted perspective and cope with stress, reflects the nurses’ adaptive coping strategies. These findings are consistent with studies indicating that self-enhancing humor can act as a resilience factor, helping individuals maintain a positive outlook in challenging situations (46). The low scores for aggressive and self-defeating humor styles further indicate a minimal inclination among nurses to use humor in ways that may be detrimental to themselves or others. Overall, the prevalence of positive humor styles suggests that nurses at Liyang People’s Hospital utilize humor as a constructive coping mechanism, potentially influencing their experiences of burnout.

The assessment of nurse burnout using the MBI-HSS revealed noteworthy findings regarding the emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment dimensions. The moderate levels of emotional exhaustion observed among the nurses in this study indicate a significant degree of work-related stress and depletion of emotional resources. This finding is particularly concerning, as emotional exhaustion is a core component of burnout and can have detrimental effects on nurses’ well-being and patient care (47–49). The high levels of depersonalization, characterized by negative and cynical attitudes toward patients, suggest a potential erosion of empathy and compassion among nurses (50). This is a critical issue, as depersonalization can lead to decreased quality of patient care and further contribute to the cycle of burnout (51). Moreover, the low levels of personal accomplishment highlight a diminished sense of professional efficacy and achievement among the nurses, which can impact their motivation and job satisfaction (52). These findings underscore the multifaceted nature of nurse burnout and emphasize the need for targeted interventions to address emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment among nurses.

Based on the study’s findings, it’s clear there is a significant association between humor styles and nurse burnout. The results revealed that nurses who exhibit higher self-enhancing and affiliative humor styles tend to report lower levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, while also demonstrating higher levels of personal accomplishment. Conversely, nurses who exhibited higher aggressive and self-defeating humor styles tend to experience higher levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. These findings underscore the correlation between humor styles and nurse burnout. This supports existing literature suggesting that affiliative and self-enhancing humor can serve as adaptive coping mechanisms, buffering against the negative effects of job-related stress and burnout (53). On the other hand, nurses who exhibited higher aggressive and self-defeating humor styles were associated with higher levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. The implications of these findings are substantial for healthcare organizations and nursing management. Interventions aimed at promoting positive humor styles among nurses could serve as a preventive strategy for addressing and reducing burnout (54). This may involve incorporating humor-based training programs or workshops to cultivate positive humor styles and enhance coping mechanisms for stress and emotional exhaustion (55). By fostering a workplace culture that values and encourages positive humor, healthcare organizations can strive to create a supportive environment that promotes nurse well-being and, in turn, improves the quality of patient care (56). In conclusion, the study’s findings highlight the significant association between humor style and nurse burnout, emphasizing the potential for targeted interventions to harness the positive impact of humor on mitigating burnout and enhancing the well-being of nurses.

While this study provides valuable insights into the association between humor styles and nurse burnout, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the cross-sectional design of the study limits the ability to establish causality or temporal relationships between humor styles and nurse burnout dimensions. Longitudinal research would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how humor styles may influence the development and progression of nurse burnout over time. Additionally, the use of self-report measures for both humor styles and burnout may introduce common method bias and social desirability effects, potentially impacting the accuracy of the reported relationships. Future research could benefit from incorporating multiple data sources, such as observational or peer ratings of humor styles, and objective measures of burnout. Furthermore, the study sample was drawn from a specific geographic region and healthcare setting, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings to other nursing populations. Replication of the study with diverse samples would enhance the external validity of the results.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the complex relationships between different types of humor and the multifaceted nature of nurse burnout. The findings highlight the importance of promoting the use of self-enhancing humor among nurses. Conversely, the study suggests that the reliance on self-defeating and aggressive forms of humor may be detrimental. These results underscore the importance of considering the nuances of humor styles when addressing the issue of burnout in the nursing profession.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethical Review Committee of Liyang People’s Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CF: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SF: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. DC: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. YZ: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. WF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for the generous contributions of all the nurses who participated in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

8. Reference

1. Chelly, F, Kacem, I, Moussa, A, Ghenim, A, Krifa, I, Methamem, F, et al. Healing humor: the use of humor in the nurse-patient relationship. Occupat Dis Environ Med. (2022) 10:217–31. doi: 10.4236/odem.2022.103017

2. Lu, M-C, Tsai, C-F, and Chang, C-P. A study on the relationship among optimistic attitude, humor styles, and creativity of school children. Creat Educ. (2023) 14:1509–25. doi: 10.4236/ce.2023.147096

3. Tsukawaki, R, Imura, T, and Hirakawa, M. In Japan, individuals of higher social class engage in other-oriented humor. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:9704. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13755-4

4. Drake, AC, and Sears, CR. Do humour styles moderate the association between hopelessness and suicide ideation? A comparison of student and community samples. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0295995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0295995

5. Martin, RA. Humor, laughter, and physical health: methodological issues and research findings. Psychol Bull. (2001) 127:504–19. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.504

6. Martin, RA, Puhlik-Doris, P, Larsen, G, Gray, J, and Weir, K. Individual differences in uses of humor and their relation to psychological well-being: development of the humor styles questionnaire. J Res Pers. (2003) 37:48–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-6566(02)00534-2

7. Veale, T, Feyaerts, K, and Brône, G. The cognitive mechanisms of adversarial humor. Humor. (2006) 19:305–39. doi: 10.1515/HUMOR.2006.016

8. Kramer, CK, and Leitao, CB. Laughter as medicine: a systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies evaluating the impact of spontaneous laughter on cortisol levels. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0286260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0286260

9. Samson, AC, and Gross, JJ. Humour as emotion regulation: the differential consequences of negative versus positive humour. Cognit Emot. (2012) 26:375–84. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.585069

10. Raecke, J, and Proyer, RT. Humor as a multifaceted resource in healthcare: an initial qualitative analysis of perceived functions and conditions of medical Assistants' use of humor in their everyday work and education. Int J Appl Posit Psychol. (2022) 7:397–418. doi: 10.1007/s41042-022-00074-2

11. Yue, XD. Exploration of Chinese humor: historical review, empirical findings, and critical reflections. Humor. (2010) 23:403–20. doi: 10.1515/HUMR.2010.018

12. Berger, AA. Why we laugh and what makes us laugh: 'The enigma of Humor'. Eur J Psychol. (2013) 9:210–3. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v9i2.599

13. Warren, C, Barsky, A, and McGraw, AP. What makes things funny? An integrative review of the antecedents of laughter and amusement. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. (2021) 25:41–65. doi: 10.1177/1088868320961909

14. Romero, EJ, and Arendt, LA. Variable effects of humor styles on organizational outcomes. Psychol Rep. (2011) 108:649–59. doi: 10.2466/07.17.20.21.Pr0.108.2.649-659

15. Rosenberg, C, Walker, A, Leiter, M, and Graffam, J. Humor in workplace leadership: a systematic search scoping review. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:610795. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.610795

16. Leñero-Cirujano, M, Torres-González, JI, González-Ordi, H, Gómez-Higuera, J, and Moro-Tejedor, MN. Validation of the humour styles questionnaire in healthcare professionals. Nurs Open. (2023) 10:2869–76. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1528

17. Guenter, H, Schreurs, B, Van Emmerik, IH, Gijsbers, W, and Van Iterson, A. How adaptive and maladaptive humor influence well-being at work: a diary study. Humor Int J Humor Res. (2013) 26:573–94. doi: 10.1515/humor-2013-0032

18. Yip, JA, and Martin, RA. Sense of humor, emotional intelligence, and social competence. J Res Pers. (2006) 40:1202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.005

19. Jalili, M, Niroomand, M, Hadavand, F, Zeinali, K, and Fotouhi, A. Burnout among healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. (2021) 94:1345–52. doi: 10.1007/s00420-021-01695-x

20. Shah, MK, Gandrakota, N, Cimiotti, JP, Ghose, N, Moore, M, and Ali, MK. Prevalence of and factors associated with nurse burnout in the US. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e2036469. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36469

21. Geuens, N, Verheyen, H, Vlerick, P, Van Bogaert, P, and Franck, E. Exploring the influence of core-self evaluations, situational factors, and coping on nurse burnout: a cross-sectional survey study. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0230883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230883

22. Rudman, A, Arborelius, L, Dahlgren, A, Finnes, A, and Gustavsson, P. Consequences of early career nurse burnout: a prospective long-term follow-up on cognitive functions, depressive symptoms, and insomnia. EClinicalMedicine. (2020) 27:100565. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100565

23. Khamisa, N, Peltzer, K, and Oldenburg, B. Burnout in relation to specific contributing factors and health outcomes among nurses: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2013) 10:2214–40. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10062214

24. Leiter, MP, and Maslach, C. Nurse turnover: the mediating role of burnout. J Nurs Manag. (2009) 17:331–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01004.x

25. Ren, Y, Li, G, Pu, D, He, L, Huang, X, Lu, Q, et al. The relationship between perceived organizational support and burnout in newly graduated nurses from Southwest China: the chain mediating roles of psychological capital and work engagement. BMC Nurs. (2024) 23:719. doi: 10.1186/s12912-024-02386-x

26. Boudrias, J-S, Desrumaux, P, Gaudreau, P, Nelson, K, Brunet, L, and Savoie, A. Modeling the experience of psychological health at work: the role of personal resources, social-organizational resources, and job demands. Int J Stress Manag. (2011) 18:372–95. doi: 10.1037/a0025353

27. Poghosyan, L, Clarke, SP, Finlayson, M, and Aiken, LH. Nurse burnout and quality of care: cross-national investigation in six countries. Res Nurs Health. (2010) 33:288–98. doi: 10.1002/nur.20383

28. Welp, A, Meier, LL, and Manser, T. Emotional exhaustion and workload predict clinician-rated and objective patient safety. Front Psychol. (2014) 5:1573. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01573

29. Aiken, LH, Sloane, DM, Ball, J, Bruyneel, L, Rafferty, AM, and Griffiths, P. Patient satisfaction with hospital care and nurses in England: an observational study. BMJ Open. (2018) 8:e019189. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019189

30. McHugh, MD, Kutney-Lee, A, Cimiotti, JP, Sloane, DM, and Aiken, LH. Nurses' widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Affairs (Project Hope). (2011) 30:202–10. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0100

31. Estryn-Béhar, M, Van der Heijden, BI, Ogińska, H, Camerino, D, Le Nézet, O, Conway, PM, et al. The impact of social work environment, teamwork characteristics, burnout, and personal factors upon intent to leave among European nurses. Med Care. (2007) 45:939–50. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31806728d8

32. Park, YM, and Kim, SY. Impacts of job stress and cognitive failure on patient safety incidents among hospital nurses. Saf Health Work. (2013) 4:210–5. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2013.10.003

33. Zhang, W, Miao, R, Tang, J, Su, Q, Aung, LHH, Pi, H, et al. Burnout in nurses working in China: a national questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Pract. (2021) 27:e12908. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12908

34. Cadiz, E, Buxman, K, Angel, M, Resseguie, C, Wilder, C, Chan, L, et al. Original research: exploring Nurses' use of humor in the workplace: a thematic analysis. Am J Nurs. (2024) 45:512–9. doi: 10.1097/01

35. Sousa, LMM, Marques-Vieira, CMA, Antunes, AV, Frade, MFG, Severino, SPS, and Valentim, OS. Humor intervention in the nurse-patient interaction. Rev Bras Enferm. (2019) 72:1078–85. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2018-0609

36. Navarro-Carrillo, G, Torres-Marín, J, Corbacho-Lobato, JM, and Carretero-Dios, H. The effect of humour on nursing professionals' psychological well-being goes beyond the influence of empathy: a cross-sectional study. Scand J Caring Sci. (2020) 34:474–83. doi: 10.1111/scs.12751

37. Jamshidian Ghalehshahi, P, Manshaee, G, and Yaghoobzadeh, M. A study of the relationship between humor styles and dimensions of burnout among nurses in Najaf Abad in 2013. Modern Care. (2014) 11:203–10.

38. Jiang, H, Ma, L, Gao, C, Li, T, Huang, L, and Huang, W. Satisfaction, burnout and intention to stay of emergency nurses in Shanghai. Emerg Med J. (2017) 34:448–53. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2016-205886

39. Li, L, Fan, J, Qiu, L, Li, C, Han, X, Liu, M, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with job burnout among nurses in China: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Open. (2024) 11:e2211. doi: 10.1002/nop2.2211

40. Martin, R, and Kuiper, NA. Three decades investigating humor and laughter: an interview with professor rod Martin. Eur J Psychol. (2016) 12:498–512. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v12i3.1119

41. Hassankhani, A, Amoukhteh, M, Valizadeh, P, Jannatdoust, P, Ghadimi, DJ, Sabeghi, P, et al. A Meta-analysis of burnout in radiology trainees and radiologists: insights from the Maslach burnout inventory. Acad Radiol. (2023) 31:1198–216. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2023.10.046

42. Xiao, Y, Dong, D, Zhang, H, Chen, P, Li, X, Tian, Z, et al. Burnout and well-being among medical professionals in China: a National Cross-Sectional Study. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:761706. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.761706

43. Lu, H, Hou, L, Zhou, W, Shen, L, Jin, S, Wang, M, et al. Trends, composition and distribution of nurse workforce in China: a secondary analysis of national data from 2003 to 2018. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e047348. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047348

44. Paran, M, Sover, A, Dudkiewicz, M, Hochman, O, Goltsman, G, Chen, Y, et al. Comparison of sense of humor and burnout in surgeons and internal medicine physicians. SouthMedJ. (2022) 115:849–53. doi: 10.14423/smj.0000000000001470

45. Salas-Vallina, A, Ferrer-Franco, A, and Fernández, GR. Altruistic leadership and affiliative humor's role on service innovation: lessons from Spanish public hospitals. Int J Health Plann Manag. (2018) 33:17. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2549

46. Ho, SK. The relationship between teacher stress and burnout in Hong Kong: positive humour and gender as moderators. Educ Psychol. (2017) 37:272–86. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2015.1120859

47. Abusamra, A, Rayan, AH, Obeidat, RF, Hamaideh, SH, Baqeas, MH, and Albashtawy, M. The relationship between nursing care delivery models, emotional exhaustion, and quality of nursing care among Jordanian registered nurses. SAGE Open Nurs. (2022) 8:10. doi: 10.1177/23779608221124292

48. Lang, GM, Patrician, P, and Steele, N. Comparison of nurse burnout across Army Hospital practice environments. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2012) 44:274–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01462.x

49. Nantsupawat, A, Nantsupawat, R, Kunaviktikul, W, Turale, S, and Poghosyan, L. Nurse burnout, nurse-reported quality of care, and patient outcomes in Thai hospitals. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2016) 48:83–90. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12187

50. Zhang, YY, Han, WL, Qin, W, Yin, HX, Zhang, CF, Kong, C, et al. Extent of compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnout in nursing: a meta-analysis. J Nurs Manag. (2018) 26:810–9. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12589

51. Van Bogaert, P, Clarke, S, Wouters, K, Franck, E, Willems, R, and Mondelaers, M. Impacts of unit-level nurse practice environment, workload and burnout on nurse-reported outcomes in psychiatric hospitals: a multilevel modelling approach. Int J Nurs Stud. (2013) 50:357–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.05.006

52. Whittington, KD, Shaw, T, McKinnies, RC, and Collins, SK. Promoting personal accomplishment to decrease nurse burnout. Nurse Lead. (2021) 19:416–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mnl.2020.10.008

53. Timofeiov-Tudose, IG, and Măirean, C. Workplace humour, compassion, and professional quality of life among medical staff. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2023) 14:2158533. doi: 10.1080/20008066.2022.2158533

54. Kantarci, B, and Kaya, SF. The relationship between the humor styles of nurses and psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. (2024) 43:87–95. doi: 10.1097/dcc.0000000000000626

55. Yağan, F, and Kaya, Z. Cognitive flexibility and psychological hardiness: examining the mediating role of positive humor styles and happiness in teachers. Curr Psychol (New Brunswick, NJ). (2022) 42:29943–54. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-04024-8

Keywords: humor styles, nurse, burnout, emotional exhaustion, cross-sectional study

Citation: Fang C, Fan S, Chen D, Zhou Y and Fan W (2024) The relation between humor styles and nurse burnout: a cross-sectional study in China. Front. Public Health. 12:1414871. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1414871

Edited by:

Kun-Shan Wu, Tamkang University, TaiwanReviewed by:

Rute F. Meneses, Fernando Pessoa University, PortugalLeonidas Hatzithomas, University of Macedonia, Greece

Copyright © 2024 Fang, Fan, Chen, Zhou and Fan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Fan, eHR4enlleUBmb3htYWlsLmNvbQ==

Cuiyun Fang1

Cuiyun Fang1 Wei Fan

Wei Fan