- 1Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board, Portland, OR, United States

- 2Allyson Kelley & Associates PLLC, Sisters, OR, United States

Background: When a person dies by suicide, it takes a reverberating emotional, physical, and economic toll on families and communities. The widespread use of social media among youth and adolescents, disclosures of emotional distress, suicidal ideation, intent to self-harm, and other mental health crises posted on these platforms have increased. One solution to address the need for responsive suicide prevention and mental health services is to implement a culturally-tailored gatekeeper training. The Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board (NPAIHB) developed Mind4Health, an online gatekeeper training (90 min) and text message intervention for caring adults of American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) youth.

Methods: The Mind4Health intervention was a multi-phase, single-arm, pre-and post-test study of users enrolled in the intervention that is available via text message (SMS) or via a 90 min online, self-paced training. We produced four datasets in this study: Mobile Commons, pre-survey data, post-survey data, and Healthy Native Youth website’s Google Analytics. The analysis included data cleaning, basic frequency counts, percentages, and descriptive statistics. Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic content analysis methods and hand-coding techniques with two independent coders.

Results: From 2022 to 2024, 280 people enrolled in the Mind4Health SMS training, and 250 completed the 8-week intervention. Many messages in the sequence were multi-part text messages and over 21,500 messages were sent out during the timeframe. Of the 280 subscribers, 52 participated in the pre-survey. Pre-survey data show that 94% of participants were female, and nearly one-fourth lived in Washington state, 92% of participants in the pre-survey were very to moderately comfortable talking with youth about mental health (n = 48). Most participants interact with youth in grades K–12. Post-survey data demonstrate changes in knowledge, beliefs, comfort talking about mental health, and self-efficacy among participants. Mind4Health improved participant’s skills to have mental health conversations with youth and refer youth to resources in their community.

1 Introduction

When a person dies by suicide, it takes a reverberating emotional, physical, and economic toll on families and communities. In 2019, suicide was the fourth leading cause of death globally for people aged 15–29 years (1). In the United States, there were 48,183 suicide deaths in 2021, and suicide was the second leading cause of death among people aged 10–14 years and 20–34 years (2). Some populations in the United States have higher rates, including American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) people, veterans, individuals living in rural areas, and sexual and gender minorities (2). Unresolved trauma, grief, and loss are key factors associated with suicidal ideation and attempts (2).

From 2011 to 2021, suicide death rates significantly increased among people of color. AI/AN populations had the highest increase, from 16.5 to 28.1 per 100,000, followed by Black populations, which had a 58% increase from 5.5 to 8.7 per 100,000 during this period (3). Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted daily life with widespread lockdowns and school closures. Meherali et al. conducted a rapid systematic review of youth and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the results showed an increase in emotional stress, fear, anxiety, and depression (4). Bridge et al. identified 5,568 American youth aged 5–24 who died from suicide in 2020 during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, and an estimated 3.1% (170) were AI/AN youth (5). The pandemic had negative social, economic, and cultural consequences for AI/AN communities that may have contributed to an increase in suicides during this period (5, 6).

Internet and social media platform use increased significantly during the first year of the pandemic as many utilized these tools to stay connected with peers, family, and friends during social distancing measures (7). Social media platforms, such as X, formerly known as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok, have become a more integral part of daily life in recent years (8). An estimated 95% of youth have access to a smartphone device; over 77% of youth used YouTube, 58% used TikTok, and 50% used Instagram applications daily according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in 2022 (9).

With the widespread use of social media among youth and adolescents, disclosures of emotional distress, suicidal ideation, intent to self-harm, and other mental health crises posted on these platforms have increased (8, 10, 11). Gritton et al. conducted a focus group study with AI/AN youth in Washington and Oregon to examine views, interpretations, and actions taken when a peer publishes a concerning post online (10). A total of 32 AI/AN youth participated in three focus groups at community events. Three themes emerged from their findings: (1) youth often respond alone to concerning posts; (2) barriers to action, including difficulty understanding the true meaning of a concerning post and experiencing responder fatigue; and (3) the importance of confiding in a trusted adult or third-party responder when a concerning post is seen (10). Their findings identified a need for resources to help caring adults and peers intervene promptly to provide support and assistance to the person in distress (11).

To better prepare caring adults for that role, raining community gatekeepers is an evidence-based prevention strategy used to “identify and assist” people at-risk of suicide (12). Gatekeepers are community members: teachers, student peers, coaches, clergy, first responders, and other non-specialists who are trained to identify others experiencing suicidal ideation (13, 14). Community gatekeeper training programs are associated with increased knowledge to identify individuals at-risk for suicide and increased skills to intervene (13). The Question, Persuade, and Refer (QPR) gatekeeper training is the among the most widely utilized, validated trainings, endorsed by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center (15). The model teaches trainees to recognize suicidal warning signs, reduce immediate suicide risks, and connect at-risk individuals to appropriate mental health services (13). McKay et al. studied an online suicide prevention gatekeeper program focused on empowering parents to engage and support a child who exhibits suicidal ideation or suicidal behavior (16). The study took place in Victoria, Australia, with a total of 127 participants who identified themselves as parents of young people aged 12–25 years (16). The findings suggested suicide prevention training increased parents’ self-efficacy to intervene and help a suicidal individual as well as reduce the stigma around suicide.

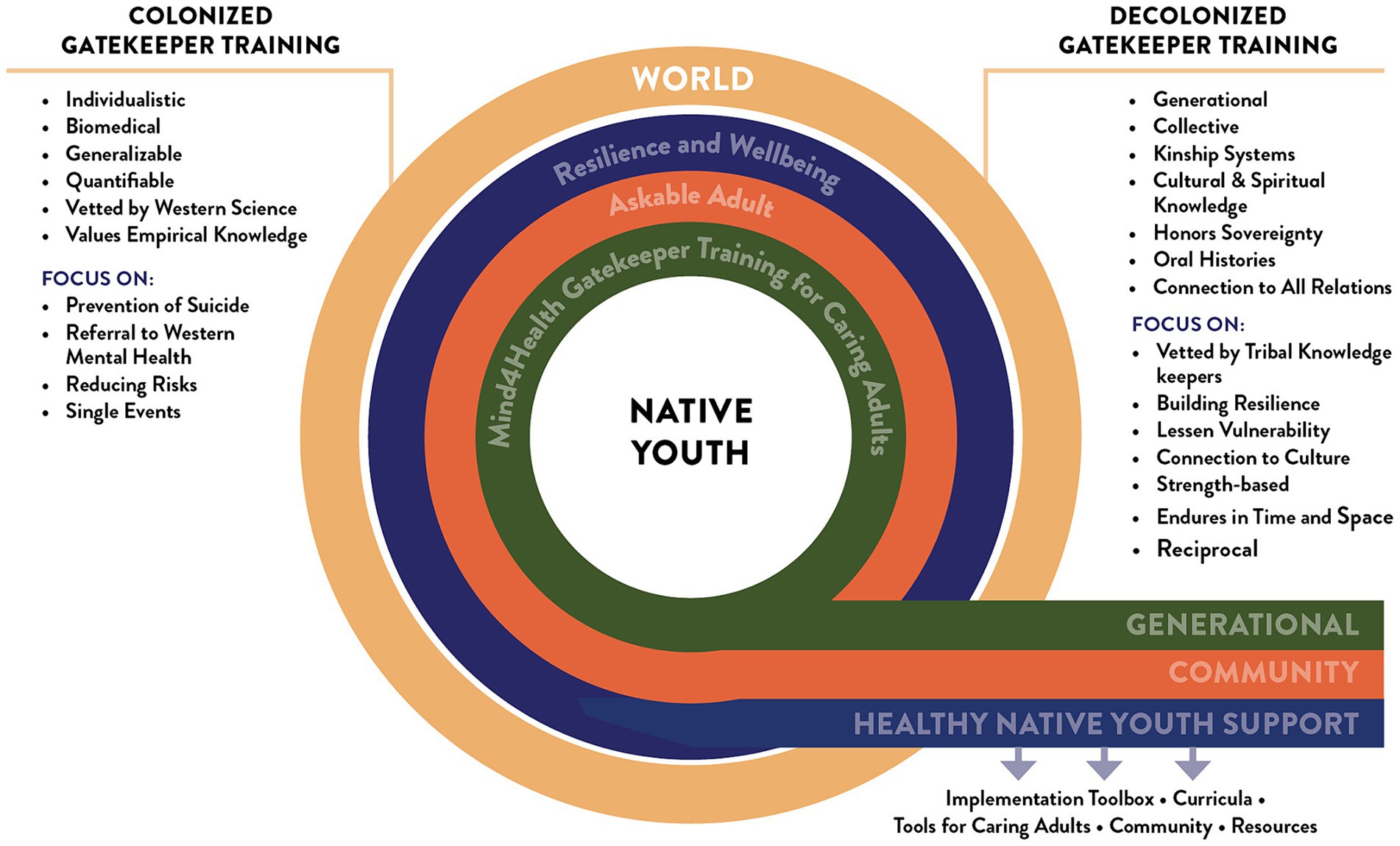

While evaluations of gatekeeper training models are associated with improved knowledge and skills to recognize and prevent suicides, they are not always culturally-tailored to AI/AN communities, who demonstrate the highest need for such interventions (17). There is a need for decolonized gatekeeper trainings grounded in traditional knowledge and Indigenous Ways of Knowing where respect, relationship, and reciprocity serve as a guide (18). A scarcity of decolonized suicide prevention services and/or resources makes it challenging to respond and identify suicide risks and resiliency factors in AI/AN communities. Moreover, a lack of culturally tailored decolonized gatekeeper suicide intervention trainings can create barriers by using strategies that do not resonate with AI/AN culture, language, and beliefs on suicide (18–20).

Gatekeeper training programs like Question Persuade Refer (QPR), Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST), Native Motivational Interviewing, and Youth Mental Health First Aid for Tribal Communities and Indigenous Peoples have cultural adaptations or in some cases, are taught by AI/AN trainers (21). However, to our knowledge, the cultural relevance of these trainings have not been systematically reviewed with AI/AN stakeholders. Anecdotal data from past participants indicates that the training materials were adapted by adding AI/AN suicide rates (a surface-level adaptation) (22). However, no deeper-level inclusion of culturally-relevant teaching methods, values, or learning styles were woven into the training. These are important features of culturally responsive teaching strategies (20).

Designing with intention a culturally tailored, decolonized AI/AN-specific suicide prevention framework can encourage generational healing, kinship, and reciprocity that builds resilience, lessens vulnerability, connects to kinship systems that endure over time. Characteristics of a culturally tailored gatekeeper training for AI/AN populations would include the following: deep cultural tailoring which is developed and reviewed by AI/AN community members and experts to include cultural values, beliefs, along with surface cultural tailoring of peripheral, evidential, and linguistic components. This type of training increases cultural awareness and cultural resiliency, addresses AI/AN strengths and community risk factors, and values the lived experiences of AI/AN community members (20). This paper fills an essential gap in the literature by documenting the development and preliminary outcomes of a decolonized, AI/AN stakeholder-reviewed, culturally-centered gatekeeper training for caring adults working with AI/AN youth, delivered online and via Short Message Service (SMS) text messaging.

1.1 Designing culturally relevant gatekeeper trainings

The Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board (NPAIHB) is a regional, tribal nonprofit organization serving the 43 federally recognized Tribes in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. The Northwest Tribal Epidemiology Center is housed under NPAIHB and provides support through research, surveillance, and public health capacity building in partnership with the Northwest Tribes. The gatekeeper trainings discussed in this paper were designed by the THRIVE suicide prevention project, Behavioral Health, and the Adolescent Health teams at the NPAIHB. NPAIHB recruited participants, delivered the SMS gatekeeper text messages, and led the design of data collection tools, data collection, and data analysis.

In 2017, the NPAIHB partnered with the Social Media & Adolescent Health Research Team to design, implement, and evaluate the first iteration of this gatekeeper training: Responding to Concerning Posts on Social Media (22, 23). The evaluation of the web-based training included 70 adults. Adults in Arm 1 watched a 30-min gatekeeper video and read handouts. Adults in Arm 2 watched the 30-min training video, reviewed accompanying training handouts, and participated in an interactive role-play scenario with a coach that took place via text message. Evaluation findings demonstrate that the intervention produced significant improvements across several areas, including confidence in starting conversations, confidence in containing a person who posted something concerning, and confidence in recommending support services to youth (22). This was the first gatekeeper training for adults that provided guidance for responding to concerning posts on social media with AI/AN youth (22).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the NPAIHB updated the Responding to Concerning Posts gatekeeper training and made several improvements based on user feedback from the pilot study. The primary updates consisted of adding additional opportunities for participant engagement, extending the duration of the training, and developing animations that role-model gatekeeping skills and culturally tailored mental health strategies. For example, participants wanted more practical tips on how to respond to a youth who was contemplating suicide.

1.2 The Mind4Health intervention

The new iteration was re-named Mind4Health. The decolonized Mind4Health online gatekeeper training intervention focuses on three behavior change areas: respond, heal, and grow, and utilizes aspects of Bandura’s self-efficacy theory and the theory of planned behavior (24). Traditional suicide gatekeeper interventions focus on changing knowledge, beliefs, stigma, and self-efficacy (25). Our decolonized theoretical framework focuses on the same learning outcomes, but also recognizes the impacts of colonization, the importance of lived experiences and stories, and supports a strengths-based approach to intervention and healing. Since its launch in July 2022, over 280 caring adults have signed up for the new Mind4Heath text message campaign.

During the update, developers added three new role model videos to the training, demonstrating the skills needed to be an “Askable Adult,” incorporated a text message sequence to practice and build up mental health skills over time, and incorporated Indigenous Ways of Knowing and Healing to support youth’s mental health. To our knowledge, this is the only suicide prevention gatekeeper training offered via SMS (see Figure 1).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Mind4Health components

The Mind4Health intervention includes two components. The first intervention component is a SMS text message sequence. The second intervention component is an online self-paced gatekeeper training, supplementing the SMS series.

Frequently asked questions about Mind4Health:

• Who can enroll in Mind4Health? Mobile Commons, the software used to deliver the text messages, is most reliable in the U.S.—in the lower 48 States. However, the online training components are available worldwide.

• Who should enroll? Mind4Health is designed for parents, coaches, counselors, and families who work with Native youth.

• What is the cost? There is no cost to participants.

• How is Mind4Health delivered? Online and/or via text message.

• What happens at enrollment? Caring adults receive 1–2 text messages per week for 8-weeks with role-model videos, conversation starters, tips, and words of encouragement that are culturally tailored with an Indigenous lens (22).

• What happens upon completion? Upon completion of the text messages, participants are asked to complete an online post-survey and receive a $30 gift card.

• What topics does Mind4Health cover? Topics cover gatekeeping and referral skills and focus on the themes of Response, Heal, and Grow.

• How is Mind4Health evaluated? Trainees complete a pre- and post-survey. Google Analytics and Mobile Commons data document dissemination and reach.

2.2 Study design

The Mind4Health intervention was a multi-phase, single-arm, pre-and post-test study of users enrolled in the gatekeeper intervention available via SMS and a 90-min online, self-paced training. All data collection tools were reviewed by the Portland Area Indian Health Service Institutional Review Board (PA IHS IRB) in Portland, OR (PI: Craig Rushing) and the evaluation findings were approved for publication. The pre & post-survey tools collected basic demographic information required by the funder (SAMSHA) when conducting gatekeeper trainings—including tribal affiliation, state, gender, primary professional role. The post-survey also included questions adapted from our prior evaluation of the Concerning Post training, which Mind4Health is modeled after (18).

2.2.1 Participant recruitment and eligibility

Adults were recruited via the NPAIHB’s social media channels (Facebook, text message, Instagram), THRIVE’s listserv reaching Tribes, tribal health organizations, Indian education and human service organizations that serve AI/AN teens and young adults. Adults were asked to text the keyword “Mind4Health” to the shortcode 65664. This prompted a series of eligibility and consent text messages, including a link to an online consent form for more information about Mind4Health.

The study included self-identified adults. All participants were required to have a cell phone with text message capabilities. Those who enrolled were asked to complete the pre-survey online (SurveyMonkey). Participants could opt out of the SMS sequence or online training at any time.

2.2.2 Delivery of the online training and text messaging intervention

Messages were delivered in a pre-scheduled format, which was based on their enrollment date. The first message in the sequence arrived 3 days after signing up. We tracked message delivery by the participant’s phone number, delivery date, and content. Some messages also included link tracking, which recorded engagement through unique link clicks, showing how many times a given URL resource was opened.

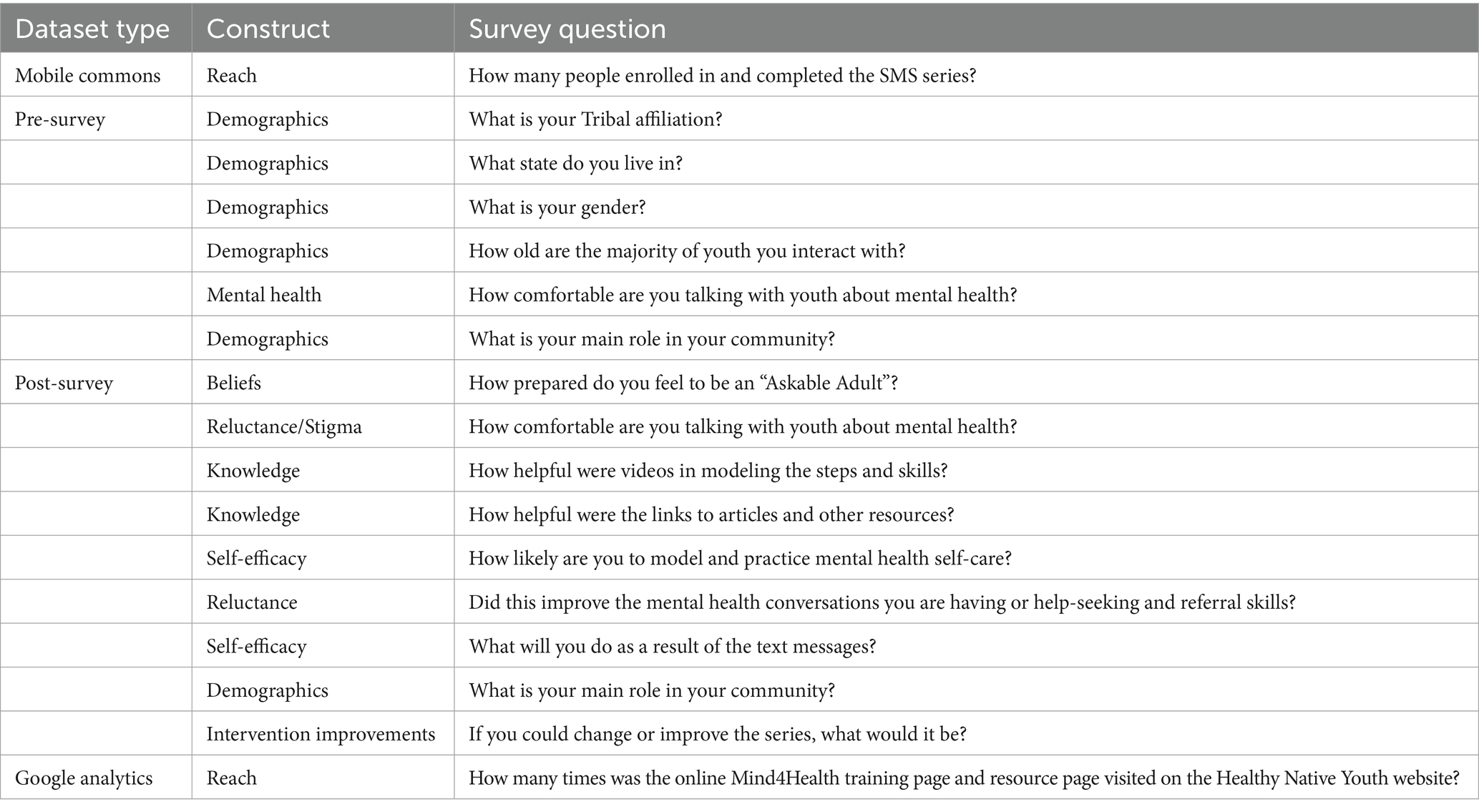

2.3 Datasets

We produced four datasets in this study. The first dataset came from Mobile Commons and documents the enrollment and reach of the intervention. The second dataset represents pre-survey data; the third dataset includes post-survey data. The pre-survey includes demographic questions, the age of the youth they work with, their comfort level in talking about mental health, and their role in the community. The post-survey includes questions about how prepared they feel to be an askable adult after receiving the intervention, comfort talking about mental health, helpfulness of the resources provided, help-seeking and referral skills, behavior changes because of the intervention, and areas for improvement. Last, the Healthy Native Youth website’s Google Analytics dashboard provides information about the number of participants accessing the website and online training. Table 1 highlights dataset types, constructs, and survey questions (see Supplementary material for the actual surveys).

2.3.1 Data analysis

Data were downloaded into SPSS version 29.0. The analysis included data cleaning, basic frequency counts, percentages, and descriptive statistics. An independent-sample, non-parametric statistical test (Fisher’s Exact Test) was used to examine the differences in participants’ responses to the question: “How comfortable are you talking with youth about mental health?” (26). Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic content analysis methods and hand-coding techniques with two independent coders (27). Qualitative analysis followed published guidelines and included open coding text responses from surveys to create a codebook. Coders reviewed data systematically for themes first to explore concepts and categories in the data and then group data into themes based on their similarity (27). Quantification was used to summarize the frequency of themes identified.

3 Results

From 2022 to 2024, 280 people enrolled in the Mind4Health SMS training, and 250 completed the 8-week intervention. Many messages in the sequence were multi-part text messages and over 21,500 messages were sent out during the timeframe (See Supplementary material for example of SMS texting sequence). We received 980 responses, including text message reactions (i.e., thumbs-up emojis or replies with “loved this message”) and opt-outs. There was a 38% click-through rate among the links that were tracked for engagement. Mind4Health pre- and post-survey data show improvements in knowledge. Participants shared positive feedback about resources and feel more prepared to be an askable adult. The Mind4Health Gate Keeper Training and Tools for Caring Adults are some of the most viewed resources on the Healthy Native Youth website.

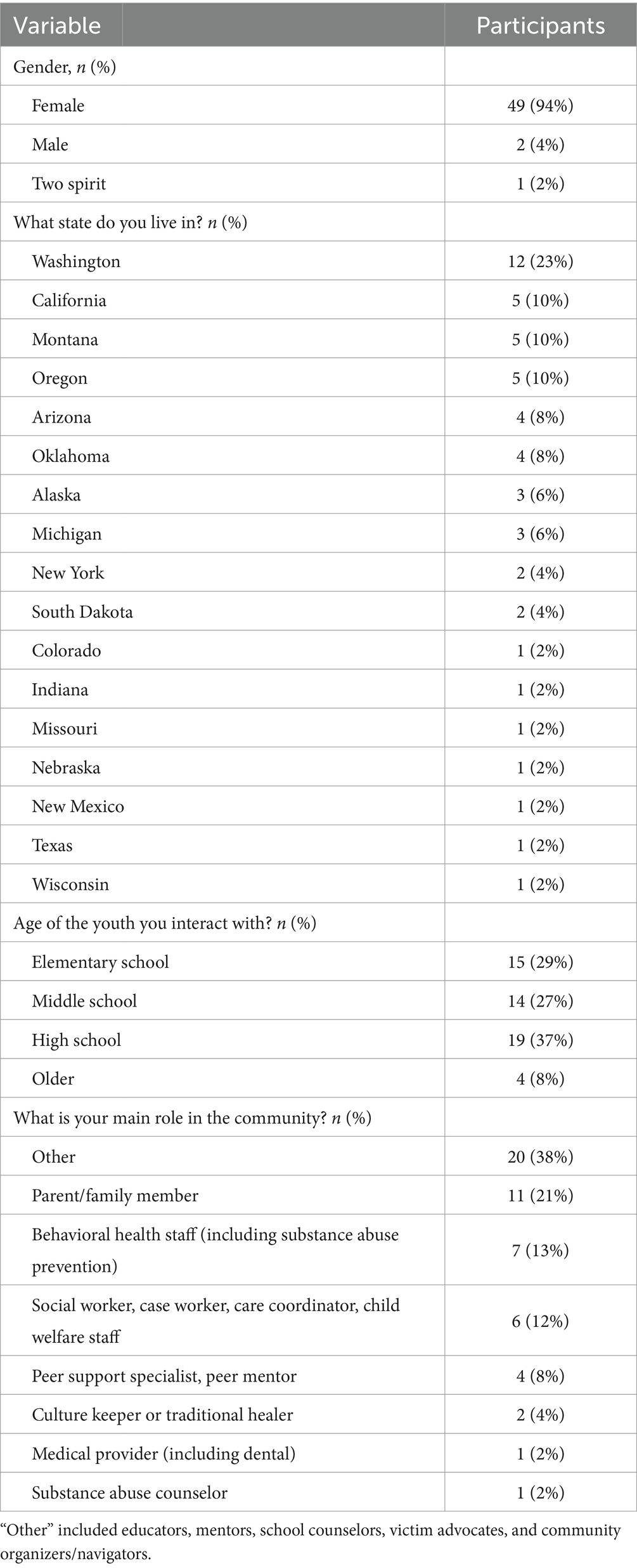

3.1 Mind4Health pre-survey

Fifty-two subscribers completed the pre-survey. Pre-survey data show that 94% of participants were female, and nearly one-fourth lived in Washington state, 92% of participants in the pre-survey were very to moderately comfortable talking with youth about mental health (n = 48). Most participants interact with youth in grades K–12. Roles varied, from educators and mentors to parents and family members in Table 2.

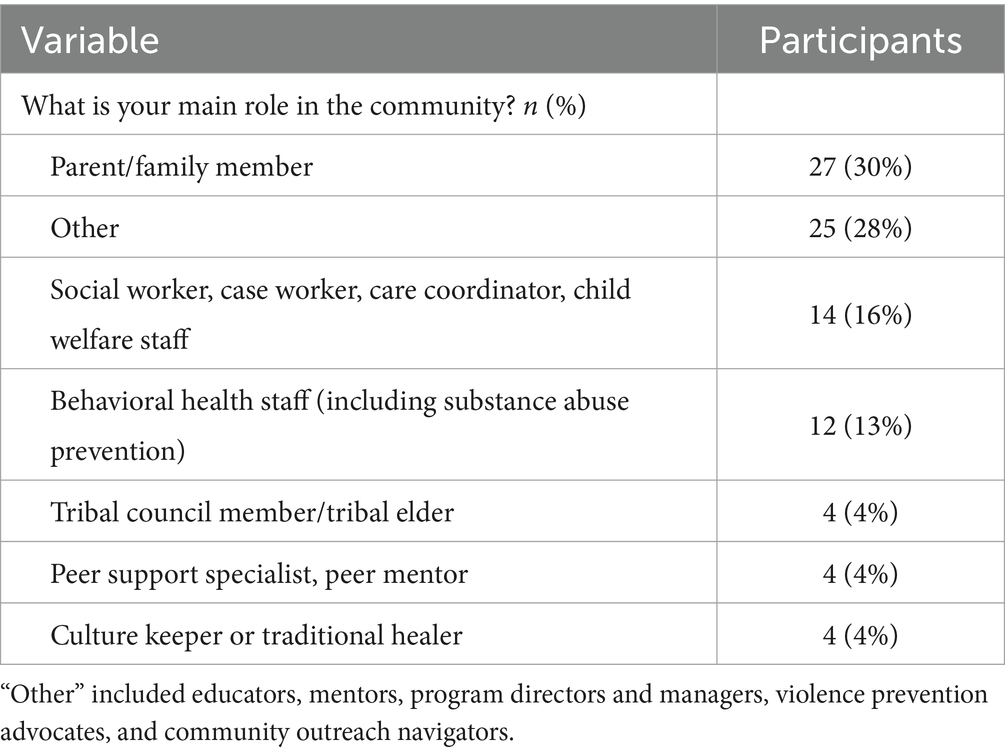

3.2 Mind4Health post survey

Participant roles in the community at post-survey were similar to the pre-survey, with parents, family members, educators, and outreach roles being most frequent in Table 3. Ninety subscribers completed the post-survey.

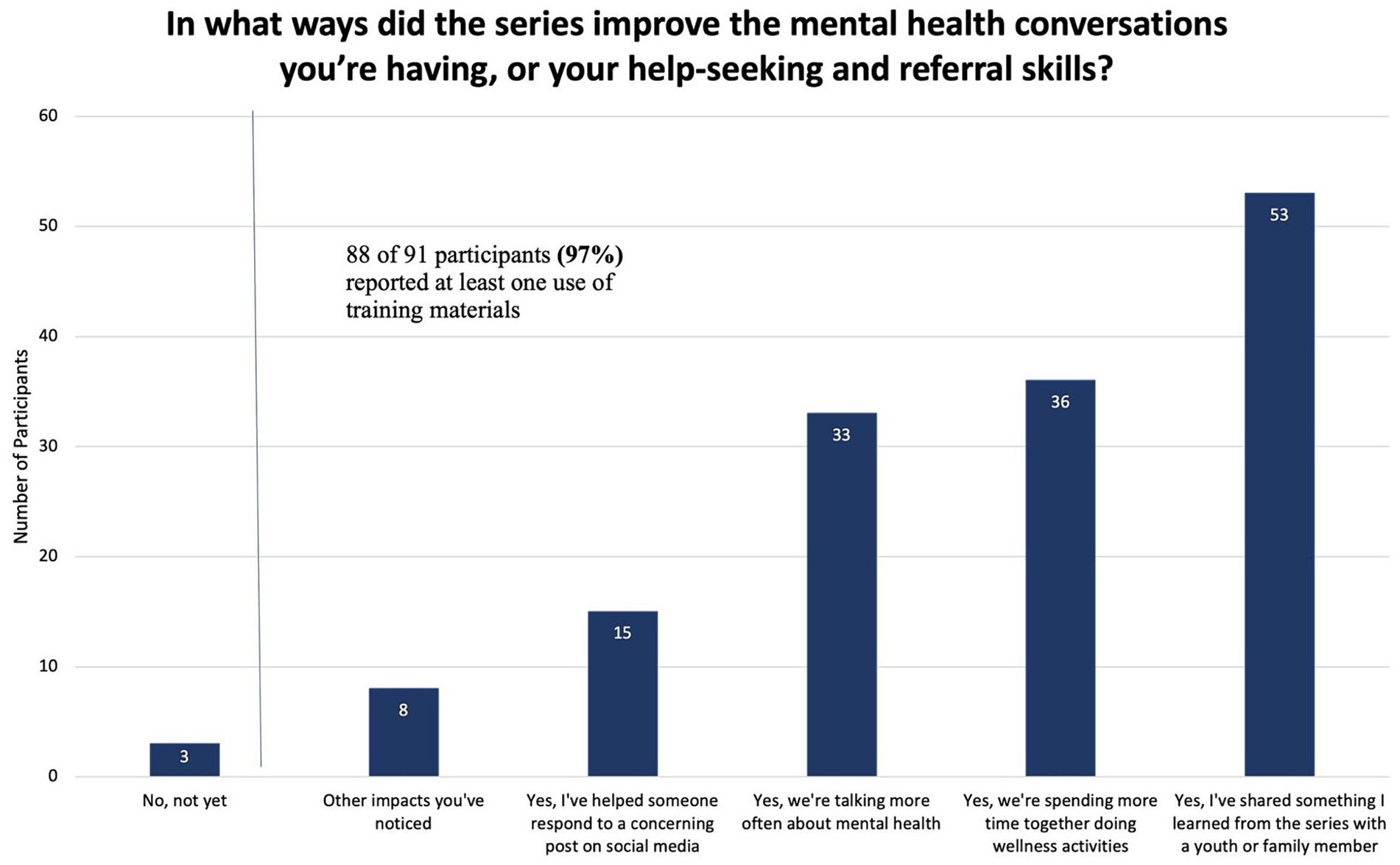

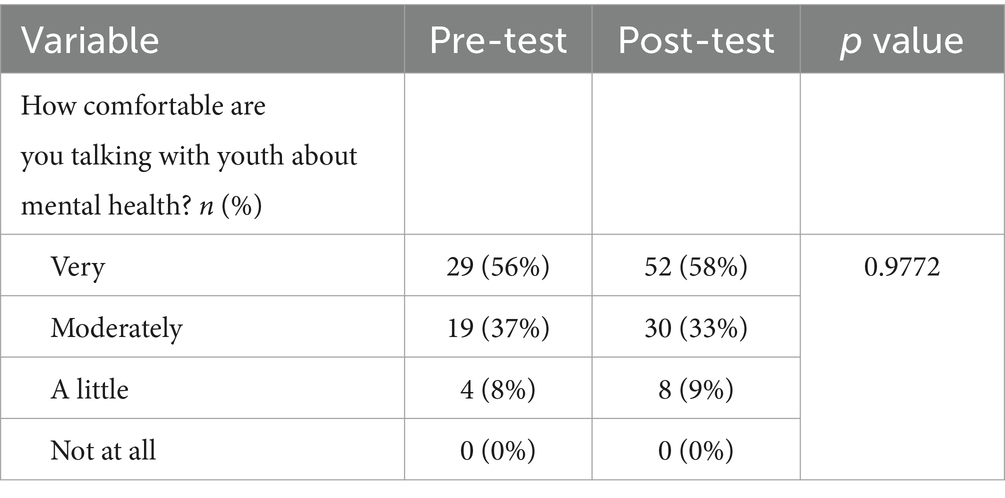

Post-survey data demonstrate changes in knowledge, beliefs, comfort talking about mental health, and self-efficacy among participants. Mind4Health improved participant skills to have mental health conversations with youth and refer youth to resources in their community (see Figure 2). However, the comfort level of participants talking about mental health did not change significantly from pre- to post-survey in Table 4.

Differences in participants’ responses to the question: “How comfortable are you talking with youth about mental health?” are highlighted in Table 4. Participants were provided with responses of “not at all,” “a little,” “moderately,” or “very.” As shown in Table 4 above, there was no statistically significant difference in the distribution of participants’ levels of comfort talking with youth about mental health pre vs. post (p = 0.9772).

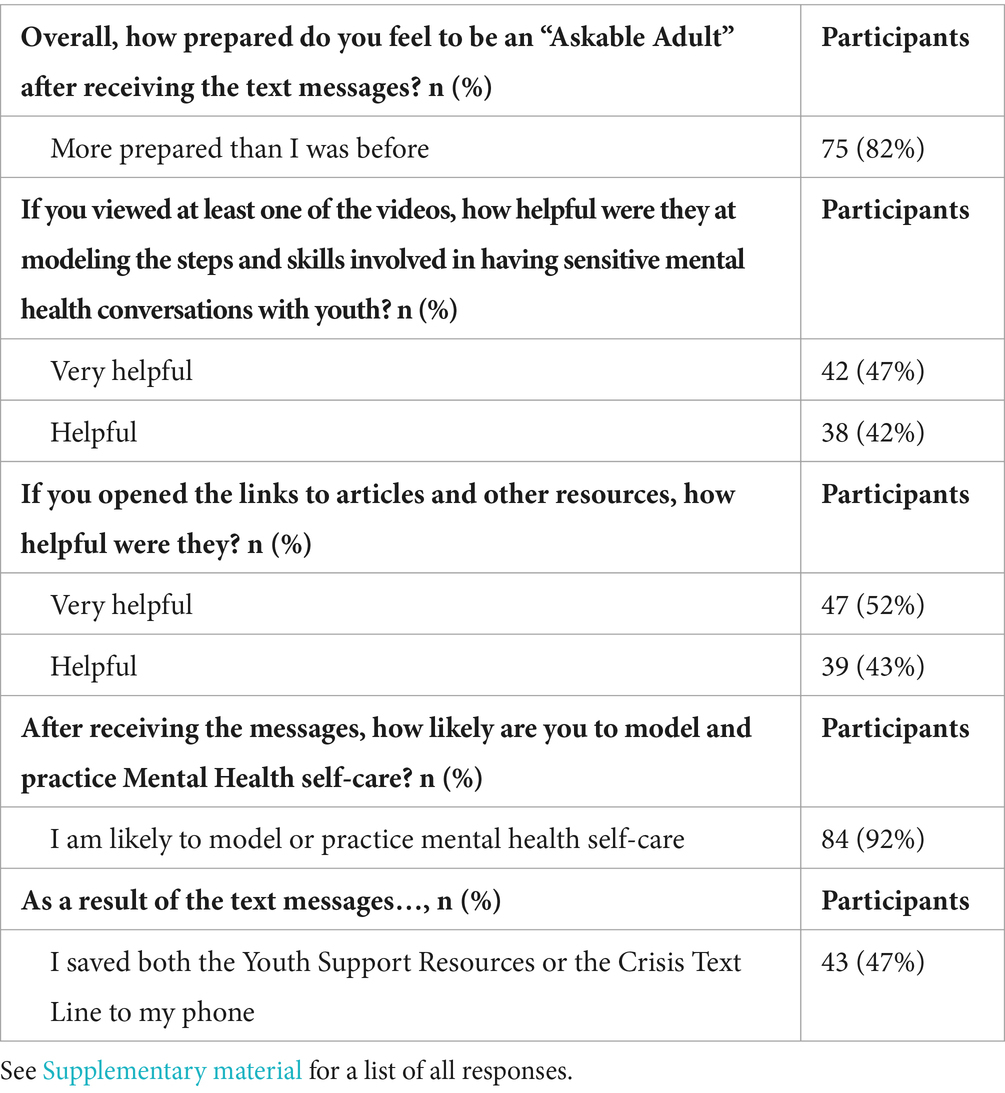

After completing the series, 75% of participants felt more prepared to be an askable adult and 42% found the videos very helpful, and 52% found the articles and resources very helpful, noted in Table 5.

In the final question, participants were asked: We appreciate your honest feedback. If you could change or improve something about the series, what would it be? Qualitative recommendations for changes to improve the Mind4Health intervention included: please continue the service, send “more frequent texts,” suggestions for additional content and resources—like “stickers to send out would be nice”—and providing clarification on the characters depicted in the role model video, “sometimes using names confused me…,” included in Table 6.

3.3 Mind4Health dissemination

From 2022 to 2024, the Mind4Health “Tools for Caring Adults” webpage had 1,307 pageviews, from 730 users. The number of pageviews per user was 1.79, and the average engagement time on the page was 58 s. During that period, the Mind4Health “Tools for Caring Adults” resource page was the 14th most visited page on the Healthy Native Youth website: https://www.healthynativeyouth.org/resources/mind4health/.

From 2022 to 2024, the Mind4Health Gatekeeper Training page had 1,007 pageviews, from 573 users. The number of pageviews per user was 1.76, and the average engagement time on the page was 56 s. During that period, the Mind4Health Gatekeeper Training curricula page was the 18th most visited page on the Healthy Native Youth website: https://www.healthynativeyouth.org/curricula/mind4health-training/.

The Articulate Software used to design and host the 90-min online training does not track “views” or participant engagement (i.e., embedded polls or reflection activities) and are thus not included in this paper.

4 Discussion

Outcomes from this study show several benefits from the Mind4Health training among intervention participants. Participants felt more prepared to have mental health conversations after the training. Resources, links, and articles were helpful and utilized by participants. Notably, participants reported they shared information and resources from the Mind4Health resource page with youth and other family members. Participants increased their knowledge, confidence, and skills to recognize a person in mental health distress and are better able to link those people to appropriate resources. Findings from this evaluation are unique; no other studies cite the use of a decolonized gatekeeper training to address suicide in AI/AN populations. The results of this study support the continued use of decolonized gatekeeper trainings to address the suicide epidemic by building community-based knowledge, addressing stigma that often surrounds mental health help-seeking, and growing the self-efficacy of trusted, askable adults.

Recommended improvements to the Mind4Health intervention were minimal and are likely because the curriculum was designed and vetted by AI/AN stakeholders and updated from previous work with AI/AN communities. Some participants wanted to receive additional text messages, others felt additional content, resources, and information would be helpful. These recommendations will be integrated into future iterations of the Mind4Health training.

Our study findings are supported by other evaluations of gatekeeper trainings to prevent suicide (28, 29). Such studies demonstrate the importance of gatekeeper training for building knowledge, and self-efficacy, addressing stigma, and providing resources to lessen suicide risk. However, these evaluations were not conducted using a decolonized gatekeeper approach. Findings from colonized trainings are limited because they focus narrowly on quantitative outcomes and effect sizes, and value Western educational systems and degrees as a benchmark for assessing knowledge and self-efficacy. This is in contrast to a decolonized model, where a generational connection to all relations, lived experience, subjective data and cultural resilience are the focus.

Every AI/AN community has a unique history, culture, language, and tradition. A one-size-fits-all approach to gatekeeper training interventions is not possible. In fact, standardized approaches to developing and implementing gatekeeper training with AI/AN populations may not be effective if they are incongruent with the experiences of AI/AN youth and families in those communities. Most do not recognize the etiology of suicide and distress leading to suicide, including colonization, residential boarding schools, assimilation, structural violence, and oppression (18). Biomedical and individualistic approaches to addressing suicide in AI/AN populations are limited in their effectiveness and sustainability because they fail to honor the significance of relational and spiritual connections, world view, historical and intergenerational trauma, and kinship systems that are at play in communities, not always measured or counted in the Western context.

Stigma and reluctance to discuss suicide are common, especially in AI/AN communities (29). Culturally-tailored SMS and online gatekeeper interventions such as Mind4Health may be more effective in reaching people because user-engagement is anonymous and can be completed at the participant’s convenience and staggered readiness levels; they do not require live or in-person conversations and roleplays with others. Changing the focus and language from suicide to vulnerability may be necessary to fully decolonize gatekeeper trainings. In Mind4Health, the focus is on identifying and building local support networks and empowering people to tap into local and national resources before a crisis occurs. To help build help-seeking skills among those at-risk, the NPAIHB also designed and delivers Caring Text Messages (CTM), an evidence-based intervention modeled after Caring Contacts, which has been shown to prevent suicide in a variety of settings. The Caring Text Messages were co-developed with AI/AN teens, college students, and veterans, and were designed to increase protective factors, like cultural pride, hope, and self-esteem. While doing so, the CTMs offer participants a personal connection to peers they could relate to (30).

The Promoting Community Conversations About Research to End Suicide approach is another example of a decolonized intervention to address a vulnerability that focuses on the role of stories, connections, hope, culture, and belonging (31). By following a broader path of prevention and response, decolonized interventions have the potential to reach entire communities and address not just suicidality but the broader social and structural determinants of health that lead to deaths of despair in AI/AN communities (32).

4.1 Strengths and limitations

While this study has multiple strengths, a few limitations should be noted based on the preliminary data collected. First, participants assessed at the pre-test were unable to be paired at the post-test due to the lack of a reliable and unique identifying variable. Although we employed Fishers’ Exact Test to examine differences (25), this does not tell the entire story. Most participants enrolling in the Mind4Health series have interests, knowledge, and experiences with mental health conversations. Participants were moderate to very comfortable before and after the intervention, and this may be related to how individuals were recruited for the series and their involvement with THRIVE and other mental health promotion programs. Moreover, participants could select to complete the online self-paced webinar and the SMS sequence, alone or combined. This study does not differentiate between those who completed both versus one. Data are based on self-report measures, and social desirability bias or recall bias may be present.

There was a high level of competence of participants at the pre-survey to have mental health conversations with youth. This led to no significant change in pre- and post-survey data related to comfort level with having mental health conversations. Qualitative data reported by trainees does not represent all possible areas for improvement and does not include responses of appreciation or no comment. These findings may not be generalizable to all Tribal communities, trainees, and professionals because of the small sample size, purposive recruitment methods, and limited digital access and inequality that is pervasive in AI/AN communities. Even with these limitations in mind, this preliminary report demonstrates promising outcomes for the first decolonized gatekeeper training to prevent suicide in AI/AN communities, delivered online or via text message.

5 Conclusion

The findings from this study suggest promising results from the first-ever gatekeeper training for AI/AN caring adults, delivered via text message and a 90-min online training. As policymakers, professionals, and leaders consider how to address the suicide epidemic in this population, they must also address the broader social conditions that increase the risk of suicide. Strengthening the knowledge and skills of “Askable Adults” in AI/AN communities is the first step in addressing the epidemic. Future efforts are necessary to continue these conversations while addressing beliefs about mental health and the reluctance many feel to ask another person if they are considering suicide. Building the self-efficacy of gatekeepers to ask these difficult questions, while directing youth and families to culturally centered resources like those found on the Healthy Native Youth website, is the first step in a decolonized prevention approach.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by exempt from IRB review as (1) the surveys were anonymous and cannot be linked to individuals, and (2) the training is designed for educational purposes. However, IRB permission was obtained by the Portland Area Indian Health Service IRB to analyze the pre- and post-survey data to prepare this manuscript. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

CC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. AKa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. LG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AKe: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was developed, in part, under grant number SM082106 from SAMHSA.

Acknowledgments

We are eternally grateful to the caring adults and parents who enrolled in the Mind4Health intervention to teach us more about what it means to Respond, Heal, and Grow. The NPAIHB team who have written inspirational messages and resources for the intervention. And to the many relatives, peers and allies who are part of the Healthy Native Youth community.

Conflict of interest

Author AKe was employed by company Allyson Kelley & Associates PLLC.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The views, opinions and content of this publication are those of the authors and contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of CMHS, SAMHSA, or HHS, and should not be construed as such.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1397640/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Material 1 | Pre-survey.

Supplementary Material 2 | Post survey.

Supplementary Material 3 | Selected messages from the Mind4Health SMS texting sequence.

Supplementary Material 4 | Full list of responses from Table 5. Frequency of Mind4Health participant responses (N = 91).

References

1. World Health Organization: WHO. Suicide. Who.int World Health Organization: WHO. (2019). Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/suicide#tab=tab_1 (Accessed March 1, 2024).

2. Facts about suicide. www.cdc.gov. (2022). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html#:~:text=Suicide%20is%20a%20serious%20public (Accessed March 1, 2024).

3. Saunders, H, and Panchal, N. A look at the latest suicide data and change over the last decade. KFF. (2023). Available at: https://www.kff.org/mental-health/issue-brief/a-look-at-the-latest-suicide-data-and-change-over-the-last-decade/ (Accessed March 1, 2024).

4. Meherali, S, Punjani, N, Louie-Poon, S, Abdul Rahim, K, Das, JK, Salam, RA, et al. Mental health of children and adolescents amidst COVID-19 and past pandemics: a rapid systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:3432. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073432

5. Bridge, JA, Ruch, DA, Sheftall, AH, Hahm, HC, O’Keefe, VM, Fontanella, CA, et al. Youth suicide during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr Int. (2023) 151:e2022058375. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-058375

6. Ivanich, JD, O’Keefe, V, Waugh, E, Tingey, L, Tate, M, Parker, A, et al. Social network differences between American Indian youth who have attempted suicide and have suicide ideation. Community Ment Health J. (2021) 58:589–94. doi: 10.1007/s10597-021-00857-y

7. Draženović, M, Vukušić Rukavina, T, and Machala, PL. Impact of social media use on mental health within adolescent and student populations during COVID-19 pandemic: review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:3392. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20043392

8. Teo, AR, Strange, W, Bui, R, Dobscha, SK, and Ono, SS. Responses to concerning posts on social media and their implications for suicide prevention training for military veterans: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e22076. doi: 10.2196/22076

9. Vogels, EA, and Gelles-Watnick, R. Teens and social media: key findings from Pew Research Center surveys. Pew Research Center. (2023). Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/04/24/teens-and-social-media-key-findings-from-pew-research-center-surveys/ (Accessed March 1, 2024).

10. Gritton, J, Craig Rushing, S, Stephens, D, Ghost Dog, T, Kerr, B, and Moreno, MA. Responding to concerning posts on social media: insights and solutions from American Indian and Alaska native youth. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. (2017) 24:63–87. doi: 10.5820/aian.2403.2017.63

11. Liu, J, Shi, M, and Jiang, H. Detecting suicidal ideation in social media: an ensemble method based on feature fusion. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:8197. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19138197

12. Suicide Prevention Resource Center. A comprehensive approach to suicide prevention: SPRC. (n.d.). Available at: https://sprc.org/effective-prevention/comprehensive-approach (Accessed March 1, 2024).

13. Quinnett, P. The certified QPR pathfinder training program: a description of a novel public health gatekeeper training program to mitigate suicidal ideation and suicide deaths. J Prevent. (2023) 44:813–24. doi: 10.1007/s10935-023-00748-w

14. Yonemoto, N, Kawashima, Y, Endo, K, and Yamada, M. Gatekeeper training for suicidal behaviors: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. (2019) 246:506–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.052

15. Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Choosing a suicide prevention gatekeeper training program – a comparison table: SPRC. (2018). Available at: https://sprc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/GatekeeperMatrix6-21-18_0.pdf (Accessed March 1, 2024).

16. McKay, S, Byrne, SJ, Clarke, A, Lamblin, M, Veresova, M, and Robinson, J. Parent education for responding to and supporting youth with suicidal thoughts (PERSYST): an evaluation of an online gatekeeper training program with Australian parents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:5025. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095025

17. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The national tribal behavioral health agenda: SAMHSA. (2016). Available at: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep16-ntbh-agenda.pdf (Accessed March 1, 2024).

18. Richardson, M, and Waters, SF. Indigenous voices against suicide: a meta-synthesis advancing prevention strategies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:7064. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20227064

19. Nasir, BF, Hides, L, Kisely, S, Ranmuthugala, G, Nicholson, GC, Black, E, et al. The need for a culturally-tailored gatekeeper training intervention program in preventing suicide among indigenous peoples: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:357. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1059-3

20. Kreuter, MW, Lukwago, SN, Bucholtz, RD, Clark, EM, and Sanders-Thompson, V. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: targeted and tailored approaches. Health Educ Behav. (2003) 30:133–46. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251021

21. LivingWorks ASIST. LivingWorks. (2023). Available at: https://livingworks.net/training/livingworks-asist/ (Accessed March 1, 2024).

22. Kerr, B, Stephens, D, Pham, D, Ghost Dog, T, McCray, C, Caughlan, C, et al. Assessing the usability, appeal, and impact of a web-based training for adults responding to concerning posts on social media: pilot suicide prevention study. JMIR Mental Health. (2020) 7:e14949. doi: 10.2196/14949

23. Caughlan, C. Responding to concerning posts by native youth. Portland Oregon: American Association for Suicidology annual conference. (2019).

24. Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. (1977) 84:191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

25. Question Persuade Refer Institute. Research and theory. PR Institute. (2013). Available at: https://qprinstitute.com/research-theory (Accessed March 1, 2024).

26. Kim, HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: logistic regression. Restorat Dent Endodont. (2017) 42:342. doi: 10.5395/rde.2017.42.4.342

27. Joffe, H, and Yardley, L. Chapter four: content and thematic analysis In: D Marks and L Yardley, editors. Research methods for clinical and health psychology. London: Sage Publications (2003). 56–68.

28. Mueller-Williams, AC, Hopson, J, and Momper, SL. Evaluating the effectiveness of suicide prevention gatekeeper trainings as part of an American Indian/Alaska native youth suicide prevention program. Community Ment Health J. (2023) 59:1631–8. doi: 10.1007/s10597-023-01154-6

29. Holmes, G, Clacy, A, Hermens, DF, and Lagopoulos, J. The long-term efficacy of suicide prevention gatekeeper training: a systematic review. Arch Suicide Res. (2019) 25:177–207. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2019.1690608

30. Caughlan, C, Kakuska, A, Manthei, J, Martinez, A, DiBianco, L, and Craig Rushing, S. Formative research to design and evaluate caring text messages for American Indian and Alaska native youth, college students, and veterans. Health Promot Pract. (2024)

31. Wexler, L, White, J, and Trainor, B. Why an alternative to suicide prevention gatekeeper training is needed for rural indigenous communities: presenting an empowering community storytelling approach. Crit Public Health. (2014) 25:205–17. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2014.904039

Keywords: American Indian, suicide prevention, gatekeeper training, health education, text message intervention

Citation: Caughlan C, Kakuska A, Manthei J, Galvin L, Martinez A, Kelley A and Craig Rushing S (2024) Mind4Health: decolonizing gatekeeper trainings using a culturally relevant text message intervention. Front. Public Health. 12:1397640. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1397640

Edited by:

Mosad Zineldin, Linnaeus University, SwedenReviewed by:

Deborah Goebert, University of Hawaii at Mānoa, United StatesJacinta Hawgood, Griffith University, Australia

Copyright © 2024 Caughlan, Kakuska, Manthei, Galvin, Martinez, Kelley and Craig Rushing. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Colbie Caughlan, Y2NhdWdobGFuQG5wYWloYi5vcmc=

Colbie Caughlan1*

Colbie Caughlan1* Jane Manthei

Jane Manthei Aurora Martinez

Aurora Martinez Allyson Kelley

Allyson Kelley Stephanie Craig Rushing

Stephanie Craig Rushing