- Australian Health Policy Collaboration, Victoria University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

This rapid review delves into the realm of social prescribing as a novel approach to suicide prevention by addressing the social determinants of health. Through an exploration of various databases including MEDLINE, PsychInfo, WILEY, and Sage, a total of 3,063 articles were initially identified as potentially relevant to the research. Following a meticulous screening process, 13 articles were included in the final review, shedding light on the potential effectiveness and impact of social prescribing interventions on suicide prevention. Key findings indicate the need for additional monitoring and support for individuals at risk of suicide, emphasising warm referrals and sustained connections after referral to enhance the efficacy of social prescribing models. The review also highlights the importance of social capital and trust among vulnerable populations, underscoring the significance of community-based referrals in suicide prevention initiatives. Overall, this review identifies the potential of social prescribing as a valuable tool in mitigating suicide risk factors and promoting mental health and wellbeing in diverse populations.

1 Introduction

Social prescribing involves the referral of individuals to non-clinical care to address or prevent adverse effects of the social, environmental and economic factors that are inextricably linked with health and wellbeing. These are commonly referred to as the social determinants of health.

Social prescribing recognises that improving health or managing health conditions for individuals can require more than clinical care and that health professionals do not necessarily have the expertise, resources or time to address these needs (1–5). This additional form of prescribing enables health professionals to refer patients with social or practical needs that contribute or potentially will contribute to poor health, to a local community provider of non-clinical services (1, 3–6). This enables a wider range of options for care and management to be provided at the primary care level.

Social prescribing models have been developed internationally in the United Kingdom, Europe, United States, Canada, New Zealand, Scandinavia, Asia and Australia. In Australia, there are currently a growing number of practice or area-based programmes in several states. A trial of social prescribing to support mental health, particularly for older people, has been initiated in the state of Victoria following recommendations by a Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System (7).

Most recently, the Commonwealth and the state of Queensland have announced a new trial of Distress Brief Support, a two-week programme to support people experiencing psychological distress, offer practical solutions to manage that distress and identify additional services to aid longer-term recovery (8). The trial will be undertaken in two sites in Queensland and is to provide access to non-clinical support for people who are experiencing distress and who may be at heightened risk of suicide.

Social determinants of health, chronic illness, loneliness, mental health and wellbeing are all inextricably linked to suicide risk (9). Suicide prevention or management of suicidal distress is not explicitly targeted by existing social prescribing models in Australia. However, the current trials, and particularly the recently announced Queensland trials, of social prescribing directly inform suicide prevention given the shared underpinnings between chronic disease, social isolation, and suicide risk (e.g., social determinants of health, social capital, etc.).

Social prescribing, as an adjunct to clinical care and a resource for health professionals, particularly in primary health care, can form a bridge between the clinical care setting and the community sector to connect people to practical help to address social factors contributing to risks for suicide and influence wellbeing.

2 The evidence for social prescribing in prevention

The broader social prescribing literature supports the benefits of social prescribing for health and wellbeing, as well as the general acceptability of social prescribing for both patients and clinicians.

Suicide risk is understood to be a complex combination of biological, psychological, clinical, environmental and social factors (10). Although broader social prescribing literature has not been developed through an explicit suicide prevention lens, this paper assesses relevant evidence that the social and health benefits of social prescribing more widely are also relevant and applicable to suicide risk.

There is a significant overlap between risk factors for suicide and broader health concerns (10). For example, common psycho-social risk factors; certain physical illnesses and socio-economic factors; and some mental health conditions (11); as well as overlap in population-level approaches using risk factors.

Social prescribing has been found to be effective in reducing depression and anxiety (12). While positive results about social prescribing continue to accumulate, there remain weaknesses in the available research evidence as many studies are small-scale, do not have a control group, and focus on progress rather than outcomes, or relate to individual interventions rather than the social prescribing model. This makes the call for rigorous evaluation protocols even more pertinent (13).

Social prescribing may be able to play a role in suicide prevention by providing patients with access to community-based support services that can help address the underlying social determinants of health that contribute to suicide risk (12). Social prescribing can help address social isolation and loneliness, which are known risk factors for suicide (14).

Additionally, social prescribing models for broader health and wellbeing are likely to share many characteristics with models for suicide prevention. Though this literature is not focused explicitly on suicide prevention, this evidence is relevant in considering the efficacy and feasibility of suicide prevention models.

3 Social prescribing for suicide prevention: a rapid review

To build on the broader social prescribing literature and to examine the evidence specific to social prescribing for suicide prevention, a rapid review of the literature was conducted.

3.1 Methods

This review was guided by interim guidance on rapid reviews from the Cochrane Review Methods Group (15). A rapid review expedites the process of conducting a traditional systematic review by streamlining or omitting certain steps to produce evidence in a resource-efficient way. Complete details of the rapid review methodology can be viewed elsewhere (15).

Databases were selected to include specialised databases relevant to suicide prevention and/or social prescribing and were limited for the purposes of this rapid review. A search of databases Medline EBSCOhost, PsychInfo, Wiley and Sage was conducted. Search terms included social prescribing, suicide and efficacy with their related terms. A supplemental search was conducted of authors’ existing libraries, including grey literature. The search strategy was peer reviewed by all authors and details are included in Appendix 1.

All articles were initially reviewed by title and abstract, and all remaining articles underwent full-text review. Based on the aims, timeline and resources of this project (to inform rapid decision-making), a single author conducted the review with consultation of co-authors where required. A single author extracted data and synthesised the evidence.

Publications were included if they (i) addressed social prescribing for suicide or suicide risk factors (ii) included an evaluation component (iii) included referral outside of the medical system and (iv) were published in English. Publications were excluded if they (i) did not include community referral (e.g., referred only to an emergency department or helpline), (ii) focused only on a standalone suicide prevention intervention (e.g., gatekeeping), (iii) did not include evaluation component, (iv) were not explicitly about suicide (v) were not about social prescribing (vi) or a full text could not be sourced.

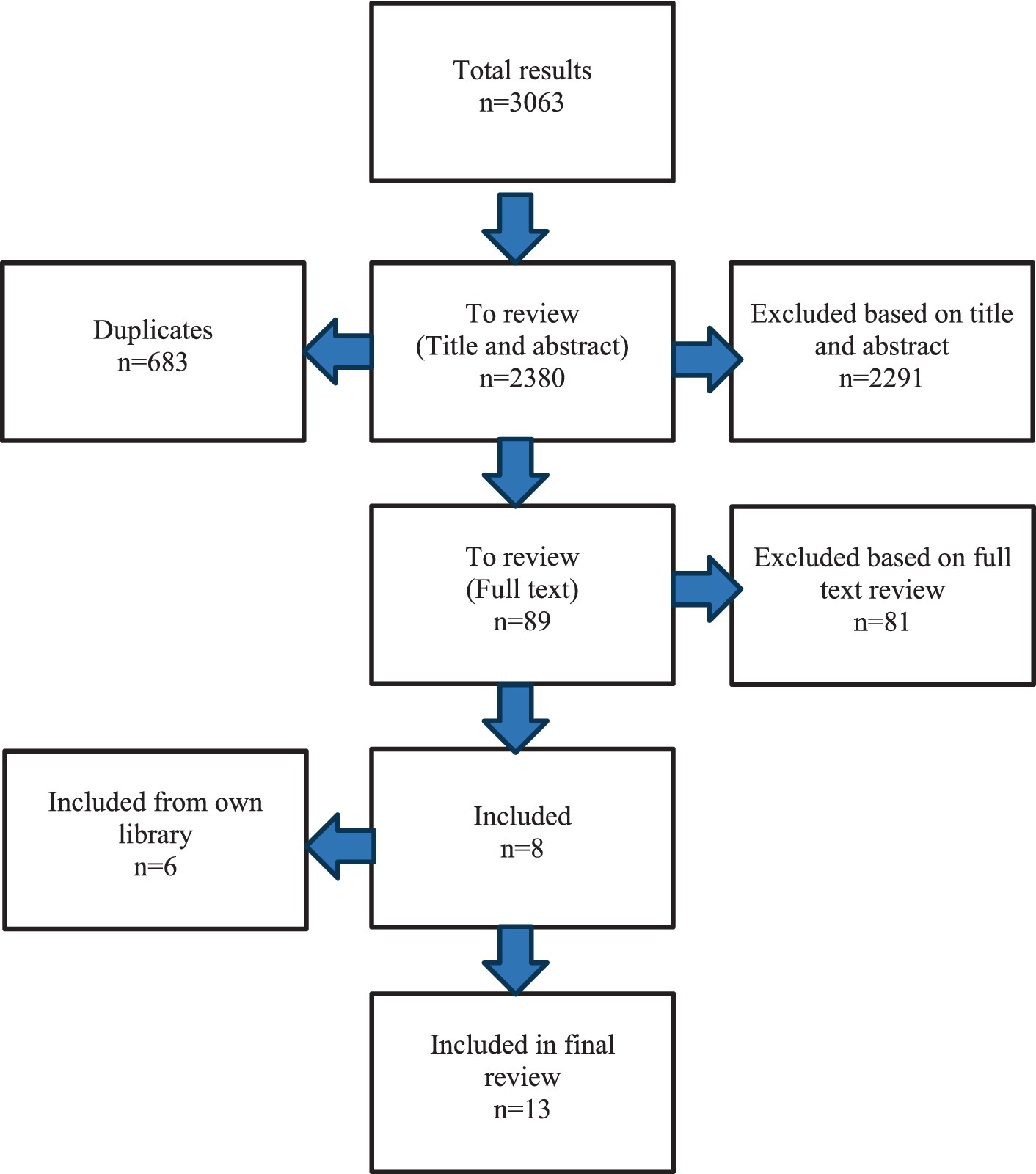

A total of 3,063 publications were identified from all databases, of which 683 were duplicates. Publications were evaluated for eligibility against inclusion and exclusion criteria. After review of 2,380 titles and abstracts, 89 publications were selected for full-text review. After full-text review of the 89, a total of 8 publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in this rapid review. Reasons for exclusions included (i) did not include community referral (e.g., referred only to an emergency department or helpline) n = 27 (ii) focused only on a standalone suicide prevention intervention (e.g., gatekeeping) n = 27, (iii) did not include evaluation component n = 5 (iv) were not explicitly about suicide n = 9 (v) were not about social prescribing n = 11 (vi) or a full text could not be sourced n = 4. An additional 6 publications were identified from the authors’ libraries and were also included in the review. A summary of the review process is outlined in Appendix 1 (Figure 1).

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Social prescribing: addressing risk factors of suicide

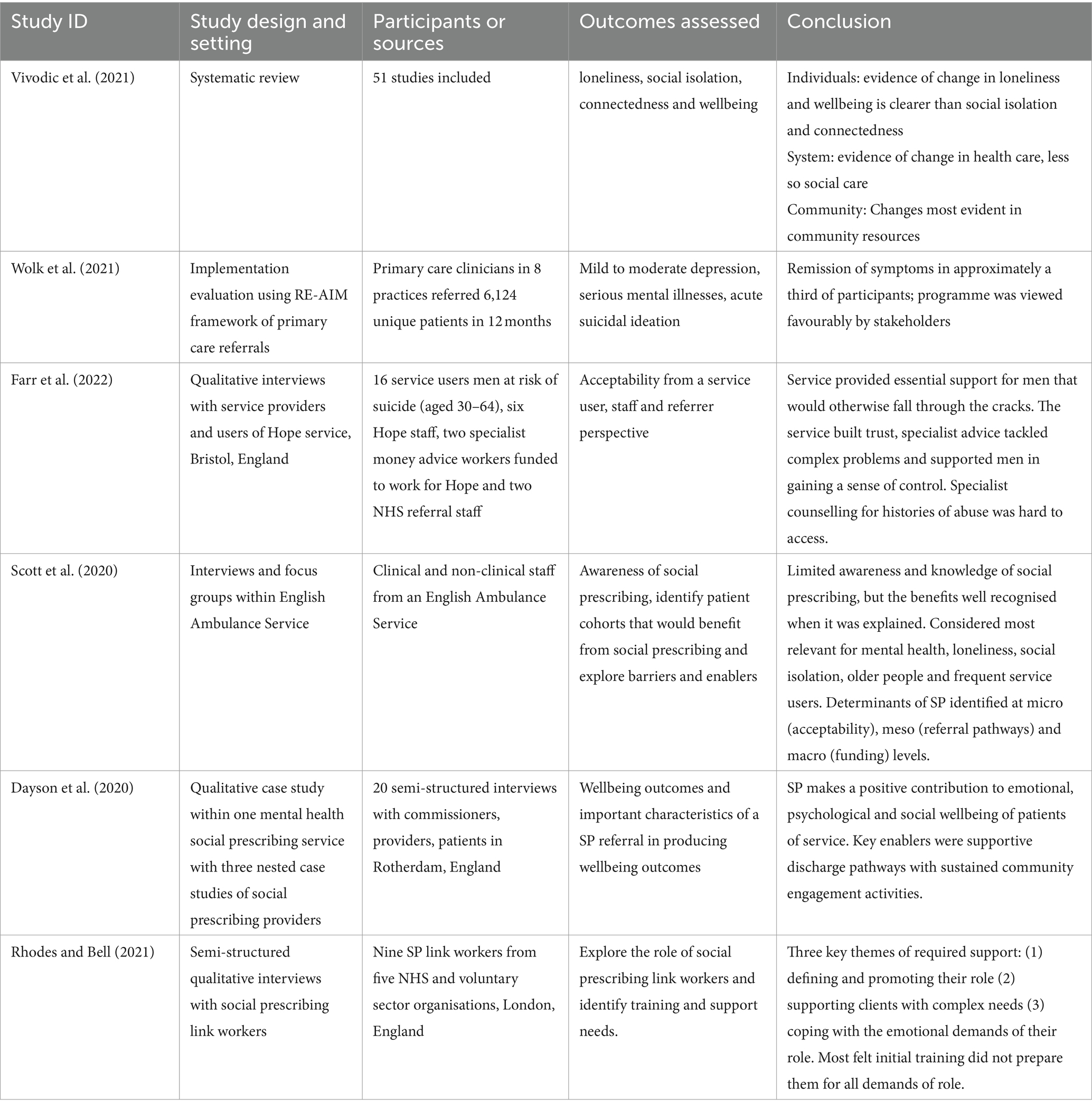

Most of the included literature examined social prescribing models relevant to suicide prevention through suicide risk factors, such as loneliness, social isolation or mental health concerns (Table 1). Two recent systematic reviews evaluated the literature on the impact of social prescribing on social risk factors for suicide. Reinhardt et al. (16) assessed the impact of social prescribing programmes on loneliness. A total of nine studies met inclusion criteria, all of which, as reported by Reinhardt et al., described overall positive impacts of social prescribing programmes. Three of the studies reported a reduction in service use (e.g., GPs, social worker) and one demonstrated that belongingness reduces both loneliness and healthcare use.

Similarly, Vivodic et al. (17) conducted a systematic review of the impact of social prescribing on loneliness, social isolation, connectedness and wellbeing. They examined a total of 51 studies of adults aged 18 or older. When looking at individual outcomes, the authors identified that findings were clearer in relation to loneliness and wellbeing compared to social isolation and connectedness. System-level findings of this review include reductions in health care usage (e.g., emergency department visits, healthcare appointments). Importantly, Vivodic et al. identify that few studies made clear causal links between positive outcomes and the social prescribing model. Authors identified barriers to effective programme delivery (e.g., patient accessibility, funding). However, there are few descriptions of key components of social prescribing models. Both systematic reviews identify significant variation in measuring outcomes and identifying pathways of impact and call for improved evidence on how social prescribing works and how best to define its impact.

One study tested a model of collaborative care for referred patients with unmet mental health needs. Wolk et al. (18) developed and implemented the US-based Penn Integrated Care programme; a new model of collaborative care that includes a triage and referral management system based on a resource centre that also provided support for individuals to be referred to appropriate community health services and resources. The programme was trialled by primary care clinicians in 8 practices. Patients with specific conditions, ranging from mild to moderate depression, serious mental illnesses, to acute suicidal ideation, were referred to community programmes based on clinical assessment, their preferences, insurance coverage and information from the primary care clinician. The centre then assisted with scheduling an appointment and followed up to ensure the individuals attended and engaged with care. If not, the centre linked them to other services. Mental health professionals were available for ‘warm’ referrals when patients were in crisis, however, most referrals were conducted electronically. Where appropriate, patients were referred to community-based programmes, psychiatrists or specialists. In 12 months, over 6,000 patients were referred, primarily to collaborative care (26%) or specialty mental health care with active referral management (70%). Of the over 6,000 referred to the programme, approximately 3,500 were provided with resources and referrals, the majority of whom (approx. 2,500) were provided community referrals. Patients enrolled in collaborative care had an average of 7 encounters over an average of 78 days. Remission of symptoms was obtained in approximately a third of participants and the programme was viewed favourably by stakeholders. Although this model does not examine all types of community referral (e.g., addressing social determinants of health), it demonstrates some efficacy of community referral in addressing suicide risk factors and active suicidal ideation.

More specifically, four studies describe qualitative findings of social prescribing models for suicide risk factors. Farr et al. (19) described the Hope service, a programme developed for men at risk of suicide (aged 30–64) to provide psychosocial and practical advice in relation to money, employment and housing that is based in Bristol, England. A previous pilot randomised trial found it to be feasible and acceptable (20). This study aimed to evaluate the acceptability from a service user, staff and referrer perspective and to understand which factors of the programme influence its impact. The programme used a project team member who delivered up to 8 face to face sessions within this intervention to connect each user to other agencies. While not described as such, the intervention was that of a ‘link worker’, a role now well established in social prescribing services that provides the link between the referring health or other professional and the community support sector relevant to a person’s identified or assessed needs. The evaluation research identified key elements of the programme including creating a safe space, building trust and specialist advice on psychosocial problems. The researchers also found that suicide ideation in men was closely linked to life crises. Addressing social factors improved a sense of control, which supported mental health. Men may also have felt less threatened by Hope project workers than those in mainstream health services. The authors noted limitations of interviewing those who were well engaged with the programme but reported that the service overall was considered useful and important.

Scott et al. (21) published a qualitative study exploring the potential for a social prescribing model within pre-hospital emergency and urgent care in England. They specifically examined groups that might benefit from this model, including those with suicidal risk factors. They conducted interviews (n = 15) and a focus group (n = 3) with clinical and non-clinical staff from an English Ambulance Service covering emergency and non-emergency calls. They wanted to determine awareness of social prescribing, identify patient cohorts that would benefit from social prescribing and explore barriers and enablers. Participants had varying levels of awareness of social prescribing. Key groups identified as suitable cohorts were patients with mental health conditions, lonely and/or socially isolated groups and older people and frequent callers. They identified key criteria for implementing a social prescribing model, including patient and staff acceptability of the model, knowledge of services, available triage pathways, funding and commissioning and equitable access across areas. At a micro level, they identified the importance of the acceptability of social prescribing; at a meso level, the importance of triage and referral pathways and at a macro level, that social and health infrastructure is essential.

Dayson et al. (22) described a social prescribing model within the NHS in England, which currently operates in primary but not secondary care. This existing primary-care based model was unable to handle referrals from community mental health services, so a second model was needed. The service helps patients tailor packages of support and enables them to participate in peer-led community events. Community mental health centres and link workers work together for 10 weeks to ensure patients are engaged with community-based activities and community mental health centres remain involved for up to 6 months. The authors conducted 20 semi-structured interviews with a mix of commissioners, service providers and patients accessing social prescribing. Patients reported improvements in quality of life and identified that social prescribing activities brought a sense of purpose, particularly that they enabled integration for previously isolated patients. The supportive transition model was very important. Not all participants engaged and/or could be discharged, so social prescribing may not be effective for everyone.

Lastly, Rhodes and Bell (23) conducted semi-structured interviews with nine social prescribing link workers across five organisations in London, exploring the role of link workers and examining training and support needs. While these link workers were not operating in an explicit suicide prevention model, they encountered suicide risk within their role. Key support needs included defining and promoting their link worker role, coping with the emotional challenges of the role and managing clients with complex needs. Most link workers felt their training was not adequate for the most challenging parts of their role, which often included suicide risk.

Overall, the literature on social prescribing for suicide risk factors indicates some positive impacts on suicide risk factors such as loneliness, belonging, social connectedness and sense of purpose. However, there are limitations to drawing causal links between social prescribing models and these outcomes, and further research is warranted. Although these models were generally considered acceptable by patients and staff, several authors outline infrastructure-associated barriers to implementing or scaling up these programmes.

3.2.2 Social prescribing for suicide bereavement and prevention

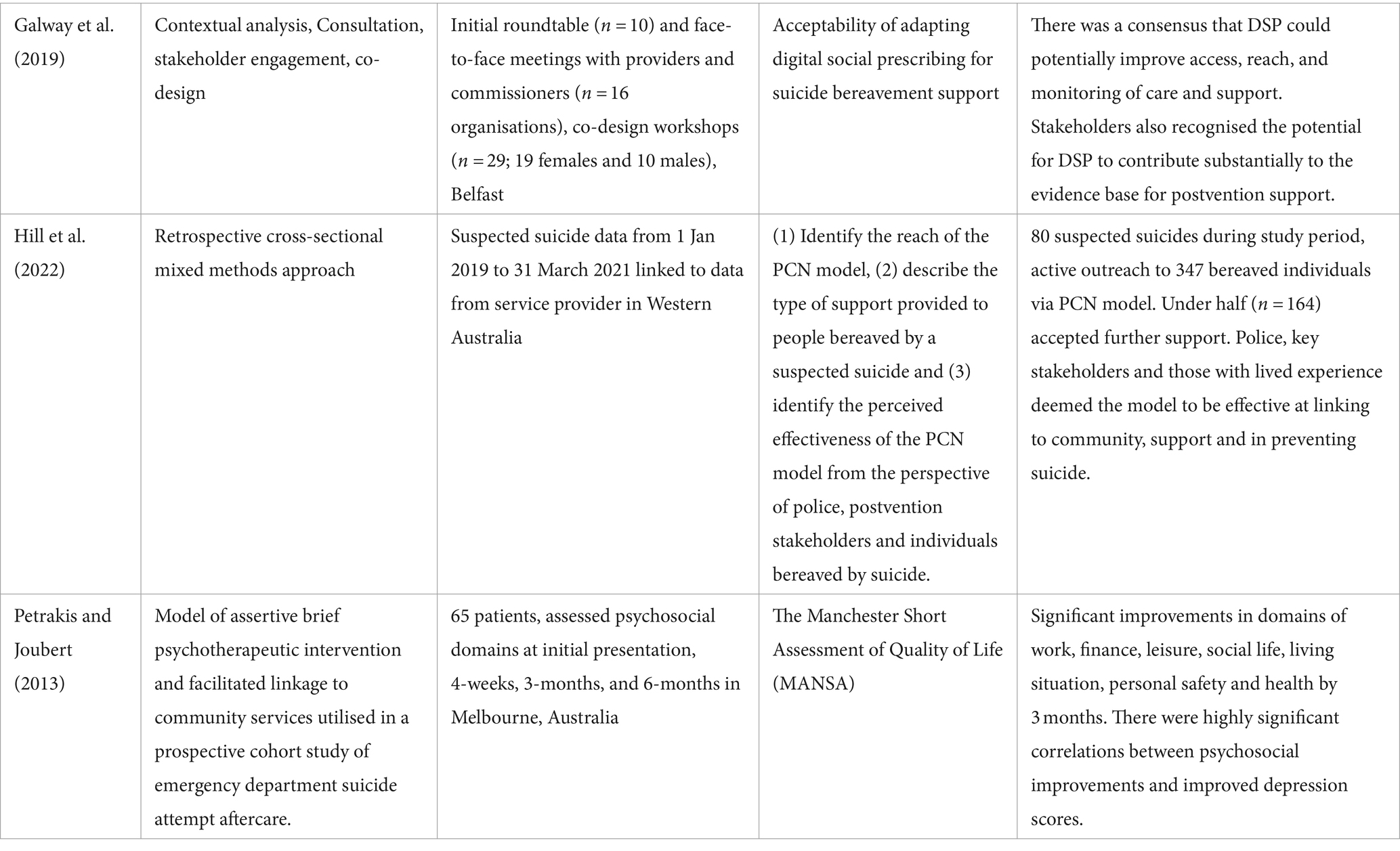

Three studies included in the rapid review examined social prescribing models that included suicide (Table 2). Importantly, two of these studies focused on suicide bereavement and one included those with reduced social support, an important suicide risk factor.

Studies by Galway et al. (24) and Hill et al. (25) both tested social prescribing for suicide bereavement support. Galway et al. tested the acceptability of adapting digital social prescribing for suicide bereavement support based in North Ireland. There was a consensus that digital social prescribing could potentially improve access, reach and monitoring of care and support. However, the stigma of care, reluctance to access support, matching types of support to needs and some limitations of digital resources (e.g., rural areas, limited internet) were noted.

Exploring a more traditional social prescribing model, Hill et al. examined a Primary Care Navigator model for people bereaved by suicide. This took place in Western Australia, and bereaved individuals were referred by police into the model. The Primary Care Navigator assessed the needs of the person(s) referred and connected them with other community services (e.g., meals, housing, sporting clubs) as needed. Over 15 months there were 90 suspected suicides and this model reached 347 bereaved individuals, just under half of whom accepted further support. While bereavement information and clinical support were the most prevalent, individuals also accessed financial assistance, meals, housing assistance, and referrals to community services (11–16%). This model was perceived to be effective by police, stakeholders and people with lived experience of a suspected suicide.

Lastly, Petrakis and Joubert (26) evaluated an intervention that, among other objectives, focused on facilitated community linkage responding to impaired social support. This was monitored through the number of referrals and subsequent engagement with existing community resources. Although the details of linkage pathways are not clearly outlined, the authors make practice recommendations about improving the interface between acute care and community care. Without monitoring, patients often do not follow up on referrals as advised. Particularly among patients with depression, monitoring and support is required for referral uptake and retention.

These studies highlight that literature explicitly taking a prevention-based approach to suicide prevention through social prescribing is limited. Importantly, engagement and effectiveness data of suicide bereavement may not readily translate to suicide prevention (e.g., people may be more likely to engage with social prescribing as an early intervention, rather than amidst a crisis). Given the unique needs and challenges of a suicide prevention social prescribing service, additional research is required.

3.2.3 Social prescribing pilots in Australia

There are several social prescribing programmes targeting risk factors associated with suicide that have been trialled and evaluated in Australia. Although other programmes may be ongoing, just three programmes were retrieved during rapid review and met inclusion criteria (Table 3).

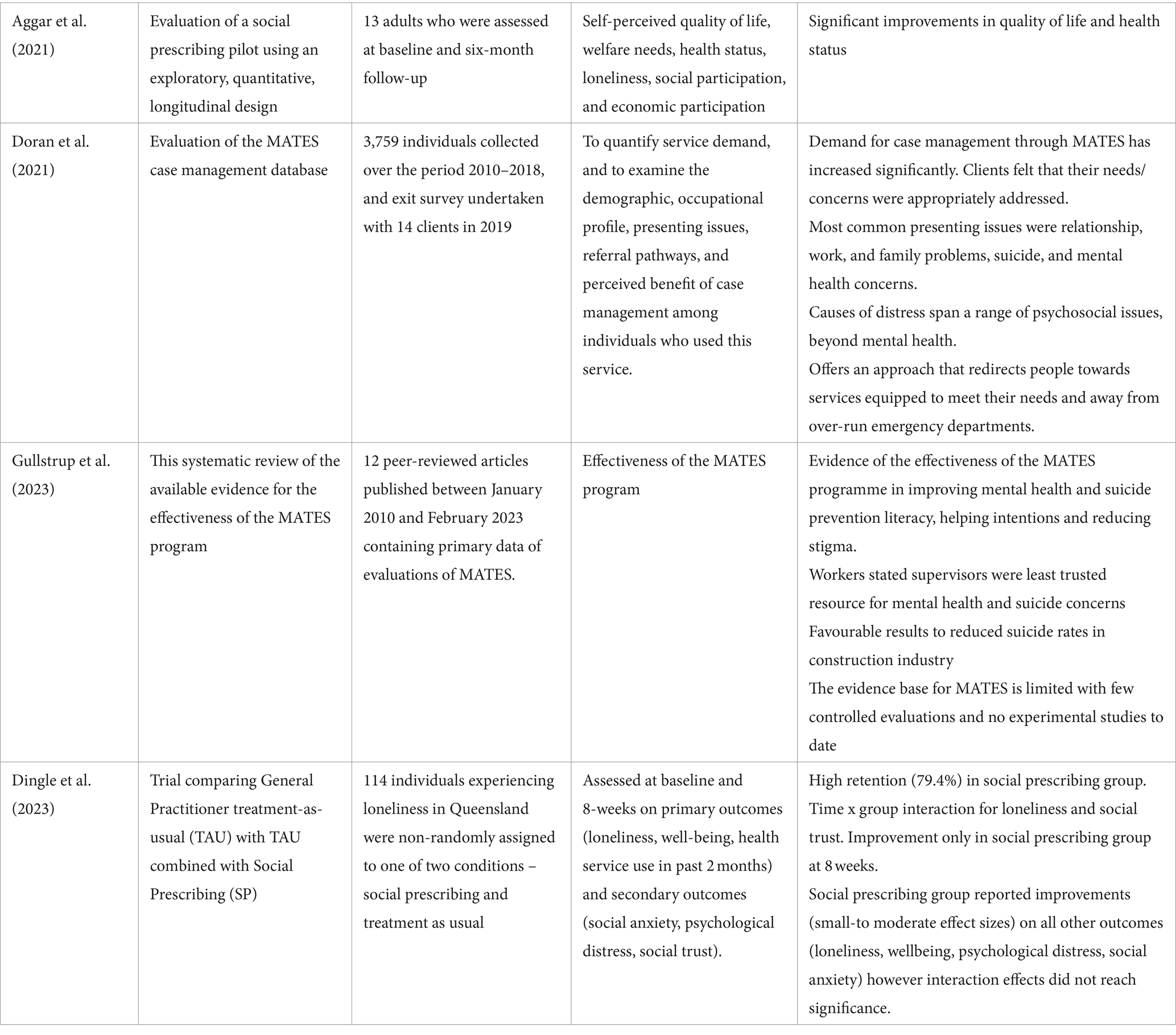

In 2021, Aggar et al. (27) published Social Prescribing for Individuals Living with Mental Illness in an Australian Community Setting: A Pilot Study. The authors describe this as Australia’s first social prescribing pilot programme (Plus Social) for individuals with mental illness (mood and psychotic spectrum disorders), and the programme was implemented in Sydney in 2016/2017. This study provides an evaluation of that programme.

A total of 13 individuals participated and were assessed at baseline and six-month follow-up; results indicate significant improvements in quality of life and health status. Participants were referred by a GP into the programme and were assessed by a mental health social worker (link worker) who referred onwards (e.g., NSW Health House and Accommodation Support Initiative) as needed. All participants also attended weekly arts and crafts classes. The results indicate that participants who completed the programme experienced significant improvements in psychological and physical quality of life, health satisfaction, and self-perceived health status. Importantly, the results show no significant differences in social participation and self-rated loneliness, although scores suggest participants experienced less loneliness through the duration of the study.

Results of an Australian-based workplace suicide prevention and early intervention programme called MATES in Construction were also published in 2021 (28). The paper evaluates service demand, demographic and occupational profile of users, reasons for access, referral pathways and perceived benefits.

MATES in Construction was developed by the Building Employees Redundancy Trust in 2008 to prevent suicide in the construction industry. The programme offers mental health training, non-clinical case management, an outreach service and a 24-h support service to employees. Previous evaluations of the programme demonstrated its validity, effectiveness in shifting beliefs around suicide, improved suicide prevention literacy and increased intentions to seek help for themselves, as well as significant economic return on investment.

The programme uses a case management approach, though MATES case managers do not provide mental health care to clients. They use a brokerage model where case managers endeavour to help clients identify services and broker supportive services over a short contact period. This model assumes the individual will voluntarily access services when they know what is available and how to access them. The focus is less on direct service to the client, and a focus on assessing needs, planning a service strategy, connecting and following up with clients. Clients are most commonly referred to Employee Assistance Programmes, followed by mental health, counselling or wellbeing services and a small proportion were referred to medical services. The findings of this evaluation indicate that clients felt their needs were addressed. Results also confirm that presenting issues include a range of psychosocial concerns.

Recently, Gullstrup et al. (29) conducted a systematic review on the effectiveness of the MATES in Construction program. The review included 12 peer-reviewed articles published between 2010 and 2023. The review identified evidence to support the effectiveness of the MATES programme in improving mental health and suicide literacy among participants, helping intentions, and reducing stigma surrounding mental health. These results were positive in relation to reduced suicide risk in the construction industry, but few studies were well-controlled and there were no experimental studies. Therefore, more research is required to understand the causal relationship between MATES and suicide risk.

Lastly, a pre-print of a paper published by Dingle et al. (30) provides a controlled evaluation of 8-week outcomes of a social prescribing project addressing loneliness in adults in Queensland. The trial compared (1) treatment as usual only with (2) treatment as usual plus social prescribing among adults experiencing loneliness. A total of 114 participants were assigned to the two groups and were tested at baseline and at 8-weeks on a range of wellbeing metrics including loneliness and wellbeing. The findings showed a time with condition interaction with only the social prescribing group showing improvements over 8 weeks. Although there were small-moderate improvements on other measures (e.g., psychological distress, loneliness, wellbeing, social anxiety) among the social prescribing group, these were not significant.

Participants were recruited from five GP clinics and/or community centres and allocation to treatment group was not randomised. Participants who were allocated to treatment as usual either declined the social prescribing group or referral wasn’t feasible, or their GP did not’ consider referral necessary. Importantly, there were some baseline differences between participants who opted to participate in social prescribing—e.g., the social prescribing group reported being more challenged. Over the first 8 weeks, loneliness decreased in social prescribing patients but increased in treatment as usual patients. Overall, compared to treatment as usual, there were significant effects on loneliness and trust among the social prescribing group.

These findings suggest that social prescribing models that address suicide prevention and/or suicide risk factors are only just beginning to emerge in the literature. In alignment with broader social prescribing evidence, these studies demonstrate that social prescribing models were generally effective at addressing needs and reducing risk factors such as loneliness. Generally, these studies did not provide substantial detail on the development of their models or the logistics of referral, indicating the importance of consulting with experts embedded in this work.

4 Discussion

The literature review on social prescribing for suicide prevention has unveiled crucial insights that can inform the development of effective intervention models. Key findings emphasise the necessity for tailored monitoring and support mechanisms for individuals at risk of suicide, highlighting the importance of ensuring follow-through in referrals. Moreover, the significance of warm referrals and sustained relationships in social prescribing initiatives for suicide prevention has been underscored, particularly in populations with lower levels of social capital and trust. These findings collectively advocate for a holistic and community-centred approach to suicide prevention through social prescribing.

Despite the valuable insights gained from the rapid review, several limitations warrant consideration. The limited number of studies included in the review may restrict the generalizability of findings to broader populations. Additionally, the focus on English-language publications may have introduced language bias, potentially overlooking valuable contributions from non-English sources. Furthermore, the rapid nature of the review process may have constrained the depth of analysis and synthesis of findings, necessitating further in-depth investigations to validate the efficacy of social prescribing in diverse contexts.

Several key considerations emerged from the literature that should be considered in developing a social prescribing model for suicide prevention, including:

• Additional monitoring and support of referrals may be required among those at suicide risk to support follow-through (26).

• Given lower levels of social capital and social trust among those at risk for suicide (31, 32), warm referrals and ongoing connections/relationships are important in social prescribing models for suicide prevention.

• Using a system-level approach, Scott et al. (21) note three key aspects of intervention:

o at a micro level, the acceptability of social prescribing is needed;

o at a meso level, triage and referral pathways are necessary; and

o at a macro level, social and health infrastructure is required.

• Those at risk of suicide are considered particularly complex and challenging for link workers (23) and additional training and resourcing may be required.

• Digital services are being explored for suicide bereavement support, but their application is currently limited to digital outcomes-based reporting to improve the capacity for measuring the effectiveness of interventions.

In conclusion, the findings from this rapid review underscore the potential of social prescribing as a promising avenue for suicide prevention by addressing social determinants of health and fostering community connections. Moving forward, it is imperative to enhance the evidence base through rigorous evaluation of social prescribing interventions tailored to individuals at risk of suicide. By integrating warm referrals, ongoing support, and community engagement into social prescribing models, healthcare systems can better equip themselves to prevent suicide and promote mental wellbeing effectively. This review sets the stage for future research and implementation efforts aimed at harnessing the power of social prescribing in mitigating suicide risk factors and enhancing overall health outcomes.

Author contributions

SD: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. MC: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. RC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This rapid review was funded by the National Suicide Prevention Office (NSPO), Australian Government to the Australian Health Policy Collaboration at Victoria University. The granting agency had no involvement in the literature search, data extraction nor interpretation of the findings.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Carrie Lambie, Sharon Lawn and Simone Jones for their contribution and feedback on the development of this model as experts working within various models of social prescribing. We also owe our thanks to Michael Cook and Bill Howarth from the National Suicide Prevention Office on their policy guidance for this report. We are grateful for their time and expertise.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Bickerdike, L, Booth, A, Wilson, PM, Farley, K, and Wright, K. Social prescribing: less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e013384. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013384

2. Healthy London Partnership, “Social prescribing: Steps towards implementing self-care - a focus on social prescribing,” London, (2017). Accessed: Jan. 10, 2022. Available at: https://www.healthylondon.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Social-prescribing-Steps-towards-implementing-self-care-January-2017.pdf

3. Pescheny, JV, Pappas, Y, and Randhawa, G. Facilitators and barriers of implementing and delivering social prescribing services: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18:86. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2893-4

4. Polley, DM, Bertotti, M, Kimberlee, R, Pilkington, K, and Refsum, C. A review of the evidence assessing impact of social prescribing on healthcare demand and cost implication. London: University of Westminster (2017).

5. South, J, Higgins, TJ, Woodall, J, and White, SM. Can social prescribing provide the missing link? Prim Health Care Res Dev. (2008) 9:310–8. doi: 10.1017/S146342360800087X

6. Chatterjee, HJ, Camic, PM, Lockyer, B, and Thomson, LJM. Non-clinical community interventions: a systematised review of social prescribing schemes. Arts Health. (2018) 10:97–123. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2017.1334002

7. A. Department of Health. Victoria, “Social Prescribing Trials.” Accessed: Jan. 09, 2023. Available at: https://www.health.vic.gov.au/mental-health-wellbeing-reform/social-prescribing-trials

8. A. G. D. of H. and A. Care, “Early support for people in distress in Queensland,” Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. (2023). Accessed: Sep. 04, 2023. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-emma-mcbride-mp/media/early-support-for-people-in-distress-in-queensland?language=en

9. Steele, IH, Thrower, N, Noroian, P, and Saleh, FM. Understanding suicide across the lifespan: a United States perspective of suicide risk factors, Assessment & Management. J Forensic Sci. (2018) 63:162–71. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.13519

10. Turecki, G, Brent, DA, Gunnell, D, O’Connor, RC, Oquendo, MA, Pirkis, J, et al. Suicide and suicide risk. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2019) 5:74. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0121-0

11. Favril, L, Yu, R, Uyar, A, Sharpe, M, and Fazel, S. Risk factors for suicide in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological autopsy studies. Evid Based Ment Health. (2022) 25:148–55. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2022-300549

12. Anderson, J, Mitchell, PB, and Brodaty, H. Suicidality: prevention, detection and intervention. Aust Prescr. (2017) 40:162–6. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2017.058

13. Dingle, GA, Sharman, LS, Hayes, S, Chua, D, Baker, JR, Haslam, C, et al. A controlled evaluation of the effect of social prescribing programs on loneliness for adults in Queensland, Australia (protocol). BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:1384. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13743-3

14. Australian Government. “Social wellbeing key to effective suicide prevention,” National Mental Health Commission. (2022). Accessed: Feb. 23, 2024. Available at: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/News-and-media/media-releases/2022/September/Social-wellbeing-key-to-effective-suicide-preventi

15. Garritty, C, Gartlehner, G, Kamel, C, King, VJ, and Nussbaumer-Streit, B. Cochrane rapid review: Interim guidance from the Cochrane rapid review methods group. BMJ. (2020).

16. Reinhardt, G, Vidovic, D, and Hammerton, C. Understanding loneliness: a systematic review of the impact of social prescribing initiatives on loneliness. Perspect Public Health. (2021) 141:204–13. doi: 10.1177/1757913920967040

17. Vidovic, D, Reinhardt, GY, and Hammerton, C. Can social prescribing Foster individual and community well-being? A systematic review of the evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:5276. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105276

18. Wolk, CB, Last, BS, Livesey, C, Oquendo, MA, Press, MJ, Mandell, DS, et al. Addressing common challenges in the implementation of collaborative Care for Mental Health: the Penn integrated care program. Ann Fam Med. (2021) 19:148–56. doi: 10.1370/afm.2651

19. Farr, M, Mamluk, L, Jackson, J, Redaniel, MT, O’Brien, M, Morgan, R, et al. Providing men at risk of suicide with emotional support and advice with employment, housing and financial difficulties: a qualitative evaluation of the Hope service. J Ment Health. (2022) 33:3–13. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2022.2091756

20. Barnes, MC, Haase, AM, Scott, LJ, Linton, MJ, Bard, AM, Donovan, JL, et al. The help for people with money, employment or housing problems (HOPE) intervention: pilot randomised trial with mixed methods feasibility research. Pilot Feasibility Stud. (2018) 4:172. doi: 10.1186/s40814-018-0365-6

21. Scott, J, Fidler, G, Monk, D, Flynn, D, and Heavey, E. Exploring the potential for social prescribing in pre-hospital emergency and urgent care: a qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community. (2021) 29:654–63. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13337

22. Dayson, C, and Batty, E. Social prescribing and the value of small providers: Evidence from the evaluation of the Rotherham social prescribing service. Sheffield: Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University (2020).

23. Rhodes, J, and Bell, S. “It sounded a lot simpler on the job description”: a qualitative study exploring the role of social prescribing link workers and their training and support needs (2020). Health Soc Care Community. (2021) 29:e338–47. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13358

24. Galway, K., “IJERPH | Free Full-Text | Adapting Digital Social Prescribing for Suicide Bereavement Support: The Findings of a Consultation Exercise to Explore the Acceptability of Implementing Digital Social Prescribing within an Existing Postvention Service.” (2019). Accessed: Jul. 06, 2023. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/16/22/4561

25. Hill, NTM, Walker, R, Andriessen, K, Bouras, H, Tan, SR, Amaratia, P, et al. Reach and perceived effectiveness of a community-led active outreach postvention intervention for people bereaved by suicide. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1040323

26. Petrakis, M, and Joubert, L. A social work contribution to suicide prevention through assertive brief psychotherapy and community linkage: use of the Manchester short assessment of quality of life (MANSA). Soc Work Health Care. (2013) 52:239–57. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2012.737903

27. Aggar, C, Thomas, T, Gordon, C, Bloomfield, J, and Baker, J. Social prescribing for individuals living with mental illness in an Australian community setting: a pilot study. Community Ment Health J. (2021) 57:189–95. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00631-6

28. Doran, CM, Wittenhagen, L, Heffernan, E, and Meurk, C. The MATES case management model: presenting problems and referral pathways for a novel peer-led approach to addressing suicide in the construction industry. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:1–11. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18136740

29. Gullestrup, J, King, T, Thomas, SL, and LaMontagne, AD. Effectiveness of the Australian MATES in construction suicide prevention program: a systematic review. Health Promot Int. (2023) 38:daad082. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daad082

30. Dingle, GA. A controlled evaluation of social prescribing on loneliness for adults in Queensland: 8-week outcomes. Review. (2023) 15: 1–10. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2853260/v1

31. Congdon, P. Latent variable model for suicide risk in relation to social capital and socio-economic status. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2012) 47:1205–19. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0429-x

32. Kelly, BD, Davoren, M, Mhaoláin, ÁN, Breen, EG, and Casey, P. Social capital and suicide in 11 European countries: an ecological analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2009) 44:971–7. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0018-4

Appendix 1: Rapid review methods

MEDLINE.

((“social prescri*” OR referral OR pathway OR linkage)) AND suicid* AND ((efficacy OR effectiveness OR impact OR benefits OR outcomes OR reduction))

English only.

Results: 1691.

PsychInfo.

((“social prescri*” OR referral OR pathway OR linkage)) AND suicid* AND ((efficacy OR effectiveness OR impact OR benefits OR outcomes OR reduction))

(All Text)

English only.

Results: 1217.

WILEY.

““social prescribing” OR “social prescription”“and “suicid*” and “efficacy OR effectiveness OR impact OR benefits OR outcomes OR reduction.”

(Anywhere)

Results: 85.

Sage.

“social prescribing” OR “social prescription” AND suicid*.

*Note that including ‘outcome’ search led to 0 results in this database.

Results: 59.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria:

Papers were included if they focused on social prescribing for suicide or suicide prevention risk factors, had some component of quantitative or qualitative evaluation, and included referrals outside of the medical system. Papers were excluded if they were in a language other than English, focused only on a single intervention (e.g., gatekeeping trials) or did not include community referrals.

Keywords: suicide, social prescribing, efficacy, prevention, review, evidence

Citation: Dash S, McNamara S, de Courten M and Calder R (2024) Social prescribing for suicide prevention: a rapid review. Front. Public Health. 12:1396614. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1396614

Edited by:

Tushar Singh, Banaras Hindu University, IndiaReviewed by:

Valentina Opancina, University of Kragujevac, SerbiaGeoffrey Walcott, University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica

Copyright © 2024 Dash, McNamara, de Courten and Calder. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maximilian de Courten, TWF4aW1pbGlhbi5kZWNvdXJ0ZW5AdnUuZWR1LmF1

Sarah Dash

Sarah Dash Stella McNamara

Stella McNamara Maximilian de Courten

Maximilian de Courten Rosemary Calder

Rosemary Calder