- 1Nursing School of Porto (ESEP), Porto, Portugal

- 2Center for Research in Health Technologies and Services (CINTESIS@RISE), Porto, Portugal

Introduction: Preoperative anxiety, with its multifactorial origins, affects a wide range of surgical patients, leading to adverse physiological and psychological effects in the perioperative period. Customized, autonomous nursing interventions are needed to address individual person needs. The shift toward outpatient surgery emphasizes the need for restructured nursing approaches. Existing literature suggests that preoperative nursing consultations offer opportunities for assessing needs, providing information, and prescribing anxiety-reduction strategies. Psychoeducation, a specialized skill within mental health and psychiatric nursing, has proven effective in alleviating preoperative anxiety and reducing postoperative complications. The aim is to obtain and analyze the information reflecting nurses’ understanding of the design, structure, and operationalization of a psychoeducation program to reduce preoperative anxiety in adults.

Methods: A qualitative, exploratory, descriptive study was conducted. Data were collected through a 90-min focus group session held online via Zoom Meetings videoconferencing platform. Inclusion criteria for the participant’s selection were established. The focus group was guided to deliberate on potential strategies for crafting effective psychoeducational interventions. Data collection ceased upon reaching theoretical saturation and gathered information was submitted for content analysis. Ethical procedures were ensured.

Results: Of the participants, 10 were specialist nurses (7 working in mental health and psychiatric nursing and the remaining in medical-surgical nursing), with an average age of 41 and an average of 15 years working in surgical services. The nurses selected the target population, the structure and content of the psychoeducation sessions, and the resources and addressed the perceived importance, effectiveness, and feasibility of the designed psychoeducation program.

Discussion: The study revealed the nurses’ understanding of the design of a psychoeducation program potentially effective in reducing preoperative anxiety in adults, in an outpatient surgery context. This result will allow the transfer of the produced knowledge to nurses’ professional practice reflecting lower levels of anxiety and promoting a better surgical recovery. This is an unprecedented study conducted in Portugal, adding substantial knowledge to the nursing discipline. However, further research into implementing psychoeducation in a surgical context is suggested aiming to consolidate the results of research already carried out internationally.

1 Introduction

Currently, there is a paradigm shift in surgical care with the development of outpatient surgery since it allows for a reduction in waiting times for surgery and hospital stays. This provides less exposure to infections, and a rapid return to daily and social activity, thus contributing to the individualization of care (1) and a reduction in hospital costs (2). In contrast, this also implies less contact with health professionals, which can contribute to increased anxiety for the person undergoing surgery and hinder the continuity of care provided by nurses (2).

The literature shows that surgical intervention is perceived as an external threat and a trigger for anxiety (3). It is estimated that more than 50 per cent of people experience some level of preoperative anxiety (4, 5), and in Western countries, the prevalence of preoperative anxiety is estimated at 70 per cent (6).

Preoperative anxiety generates adverse physiological and psychological effects (7, 8), negatively impacting the perioperative period, for example, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, increased blood pressure, tachycardia, pain, high levels of inflammation, respiratory problems, delayed healing of surgical wounds, and increased morbidity and mortality rates (4, 5, 7, 9–13). Similarly, evidence shows that the highest level of anxiety occurs on the day of surgery (14) and that controlling anxiety reduces the dose of anesthesia and analgesia required (15, 16).

Anxiety is an emotion, a warning sign, an anticipation of a future threat (17). Therefore, it is considered a person’s natural reaction to potential threats, motivating the search for coping strategies. However, the intensity and meaning attributed to anxiety differ for each person, and if it exceeds the person’s reaction capacity, it can lead to serious complications. It is a unique and multifactorial experience and, thus, a challenge when prescribing individualized nursing interventions.

Spielberger (18) defined a theory that distinguishes between anxiety as a personality trait and anxiety as a transitory emotional state. Trait anxiety refers to a relatively stable state, corresponding to the individual’s baseline level of anxiety. State anxiety is a complex emotional reaction evoked by a stimulus perceived as a danger or threat to the individual.

The same author (18) also developed the STAI (State–Trait Anxiety Inventory), which is referred to as the gold standard for measuring anxiety levels in the surgical context (3, 7, 12, 13), validated for the Portuguese population by McIntyre and McIntyre (19). Notably, using anxiety assessment instruments on admission to the surgical service allows identifying people with high anxiety levels and developing preventative mitigation interventions (20). On the other hand, knowing the factors associated with higher anxiety levels helps define patients who can benefit from these preventive interventions.

There is no consensus on these risk factors, although variables such as gender, age, education, comorbidities, previous surgical experience, previous anesthesia, use of anxiolytics, waiting time, family dysfunction, level of knowledge about the procedure, type of surgery, psychiatric pathology, and anxiety disorders emerge as potential predictors of anxiety levels (7, 21).

According to the above-mentioned, coupled with the fact that high levels of anxiety can lead to the cancelation of surgeries (22), nurses play a key role in implementing autonomous and personalized interventions aimed at early diagnosis and intervention to reduce preoperative anxiety (12, 23), since the most common interventions include anxiolytics and sedative medication (24). Hence, nurses must reprogram care delivery to meet the real needs of ambulatory surgical patients (25) undergoing a health-disease transition process (16). This process differs from person to person and requires qualified and individualized care to reduce anxiety levels, with particular emphasis on preoperative nursing care, namely the nursing visit/consultation (26).

Several studies show that preoperative nurse consultation is a crucial time to provide information and diagnose needs by establishing a specific nursing care plan that helps reduce anxiety (2, 7, 21, 27, 28) and, consequently, reduce possible complications (26).

In addition, nurses play a crucial role in implementing interventions to reduce preoperative anxiety, as they are trained professionals in direct contact with the patient from admission to discharge (12), allowing them to use various strategies such as effective communication with patients, education about procedures, pain management and postoperative care, relaxation techniques, creating a calm and relaxing environment, and providing emotional support throughout the process.

On the other hand, nurses are encouraged to develop models for providing information in the preoperative period to reduce anxiety (29). This is essential because, in Portugal, many patients have little or no information about surgical procedures, and most health institutions do not have consistent preoperative preparation protocols (8).

Considering the above stated, there is a consensus that preoperative education on anxiety management strategies can reduce preoperative and postoperative anxiety levels and consequent complications and that intervention strategies include psychoeducation, information associated with surgery, and relaxation techniques (30, 31).

The term psychoeducation was first used in 1980 for treating patients with schizophrenia (32). Since then, psychoeducation has been used as a systematic and structured intervention in different health contexts, such as cardiovascular disease, oncological disease, and dementia, among others (33).

Psychoeducation can be defined as educating a person about the symptoms, treatment, and prognosis inherent in a health condition. However, more than providing information, it is essential to promote the person’s awareness and involvement, empowering them with skills and providing tools to help them manage, cope with, and live with their condition, thus facilitating changes related to attitudes and behaviors (34, 35) to attain optimal health and well-being.

Psychoeducational intervention can have different focuses, for example, compliance/adherence, illness, treatment, and rehabilitation (36), allowing for prevention, promotion, and health education (37). It involves emotional support, including empowering people, managing expectations and emotions (38), helping change the meanings of mental disorders, and integrating psychotherapeutic, didactic, and systematic interventions to inform users about treatment and pathology.

Psychoeducation combines elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy, group therapy and pedagogy (36). Recent studies show that psychoeducation has been mostly applied with other psychosocial therapies rather than as an isolated therapy (39). It can be developed in a group or individually (37), with the individual modality favoring a personalized approach according to each person’s needs (40). However, this approach is more time-and cost-consuming, although it allows people to express themselves more easily (39). Group psychoeducation facilitates dynamic interaction between group members by sharing problems, feelings, experiences, ideas, and reactions (39).

Psychoeducation models vary according to the target group and the psychoeducation focus. An information model, a skills training model, a support model, or a more comprehensive approach can be used (36). The information model focuses on knowledge about the illness and its management, while the skills training model centers on developing self-competencies for more effective management of illness. The support model is focused mainly on the help of support groups to encourage the patient’s family members to share their feelings. The most comprehensive model combines the various models to respond to the needs of users and their families/carers (33, 36).

Also, psychoeducation can be active or passive. In active psychoeducation, the psychoeducation facilitator is actively involved with the person/family, leading to interaction. In passive psychoeducation, the individuals/family members are provided with pamphlets and audio/video material to read and assimilate information independently (36).

The facilitator can have either a paternalistic or a collaborative approach. The paternalistic approach considers the knowledge transmitted by the facilitator without considering the person’s preferences, while in the collaborative approach, there is a dialog between the professional and the person in a co-construction approach aimed at reflecting on the particularities of their experiences (33).

Therefore, the design of psychoeducational interventions can vary according to the context, the facilitator, the number of sessions, and group or individual, among others. Deciding on the best methodology depends on the individual’s needs, the content, the existing resources (time, materials, and human resources), and the objective to be achieved (33). The structure of the psychoeducational program is usually organized as systematized, pre-planned multi-sessions, following a deductive alignment starting with theoretical content and ending with training in daily life skills (33). Psychoeducation usually comprises 5 to 24 sessions, lasting 40 to 60 min each, mainly weekly (36). Nevertheless, the literature is not consistent since some studies suggest different designs, with brief psychoeducation emerging as a new concept. According to Zhao et al. (41), brief psychoeducation is a short period of psychoeducation, including 10 sessions or less. Brief psychoeducation can improve overall condition in the long term, promote improvement in mental state in the short term, and reduce the incidence and severity of anxiety in the medium term; however, the usefulness of brief psychoeducation remains questionable (41). On the other hand, the average duration of psychoeducation is around 12 weeks(41).

Regarding anxiety management, psychoeducation is a relevant intervention, supported by its positive effects on anxiety relief (30, 33, 42).

Gomes and Pergher (43) also believe that psychoeducation should be used as a form of surgical psychoprophylaxis in pre-and post-surgical follow-up for patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery. The authors concluded that obtaining information about the disease and treatment reduces anxiety and that in addition to information, relaxation is another resource commonly used with hospitalized patients because it reduces anxiety, stimulates self-care, and improves motivation for treatment (43). The same authors stress that Jacobson’s progressive muscle relaxation and breathing training can be combined with guided imagination, autosuggestion, and distraction exercises, encouraging their use in the surgical context (43). Other studies, including psychoeducational intervention and relaxation practice, show a reduction in stress and an improvement in psychological health, including anxiety symptoms (44).

Considering the lack of national and international publications on psychoeducation programs to reduce preoperative anxiety in adult outpatients (3), it is pertinent to design a psychoeducation program in nursing with this objective and evaluate its impact. The specialist nurse in mental health and psychiatric nursing is responsible for the psychoeducational intervention in Portugal (45).

Thus, the present study is part of a broader research project, which includes three tasks: 1-A study of the scientific evidence on psychoeducation programs on preoperative anxiety in adults, which has already been carried out (3); 2-Design of a nursing psychoeducation program to reduce preoperative anxiety in adults (currently under development); 3-Evaluation of the effectiveness of the nursing psychoeducation program in reducing preoperative anxiety in adults, which will be conducted by a randomized controlled clinical trial.

This present study refers to task 2 of the broader research project. Thus, the objective of this task is to design a nursing psychoeducation program aimed at reducing preoperative anxiety in adults.

2 Materials and methods

This study was a qualitative, exploratory-descriptive study. Data was collected through a focus group (FG) session to understand nurses’ opinions on the design, structure, and applicability of a psychoeducation program. The qualitative method, more specifically focus groups, was considered a methodologically appropriate strategy to delve deeper into the subjective experiences and perceptions of nurses. This method enables research based on the naturalistic paradigm, which values the meaning or nature of the experience lived by participants in a specific context, the understanding and interpretation of the phenomenon under study (46). Therefore, allows for highlighting the experience and skills of each nurse within a surgical context. FG facilitate dynamic discussions that can reveal diverse opinions and subtle nuances, crucial for effectively developing and adapting the psychoeducation program to meet the specific needs of people facing preoperative anxiety. The planning of the session was supported by the generic objectives of the extended project.

Considering that the size of FG can vary between four and 12 participants (46), 12 nurses were recruited (via email and/or telephone) to participate in the FG, selected from the contact network of the researchers of this study (47).

To recruit an accessible, diverse sample with advanced skills and professional experience in the field of surgery and/or mental health, the inclusion criteria were (i) nurses specialized in mental health and psychiatric nursing or medical-surgical nursing, (ii) having experience in the field of surgical patient care (inpatient or operative room).

Prior approval was obtained from the ethics committee (ethical approval number: 03/2023) to conduct this study.

2.1 Operationalization of the focus group

The FG was held online via the Zoom Meetings videoconferencing platform on 28 April 2023 and lasted 90 min.

The FG session began with a presentation of the broader research project. Then, the context in which the psychoeducation program will be implemented was presented (the Ambulatory Surgery Unit - UCA) of an institution in the north of the country, which has a preoperative nursing consultation for patients scheduled to undergo certain types of surgery).

This was followed by a theoretical presentation on the concept of psychoeducation and the results of the scoping review carried out in the project’s first study, which aimed to map knowledge about existing psychoeducation programs to reduce preoperative anxiety in adults (3).

Nurses were asked to complete a socio-professional characterization questionnaire, and after being informed of the rules of the FG and its objectives, they signed an informed consent form.

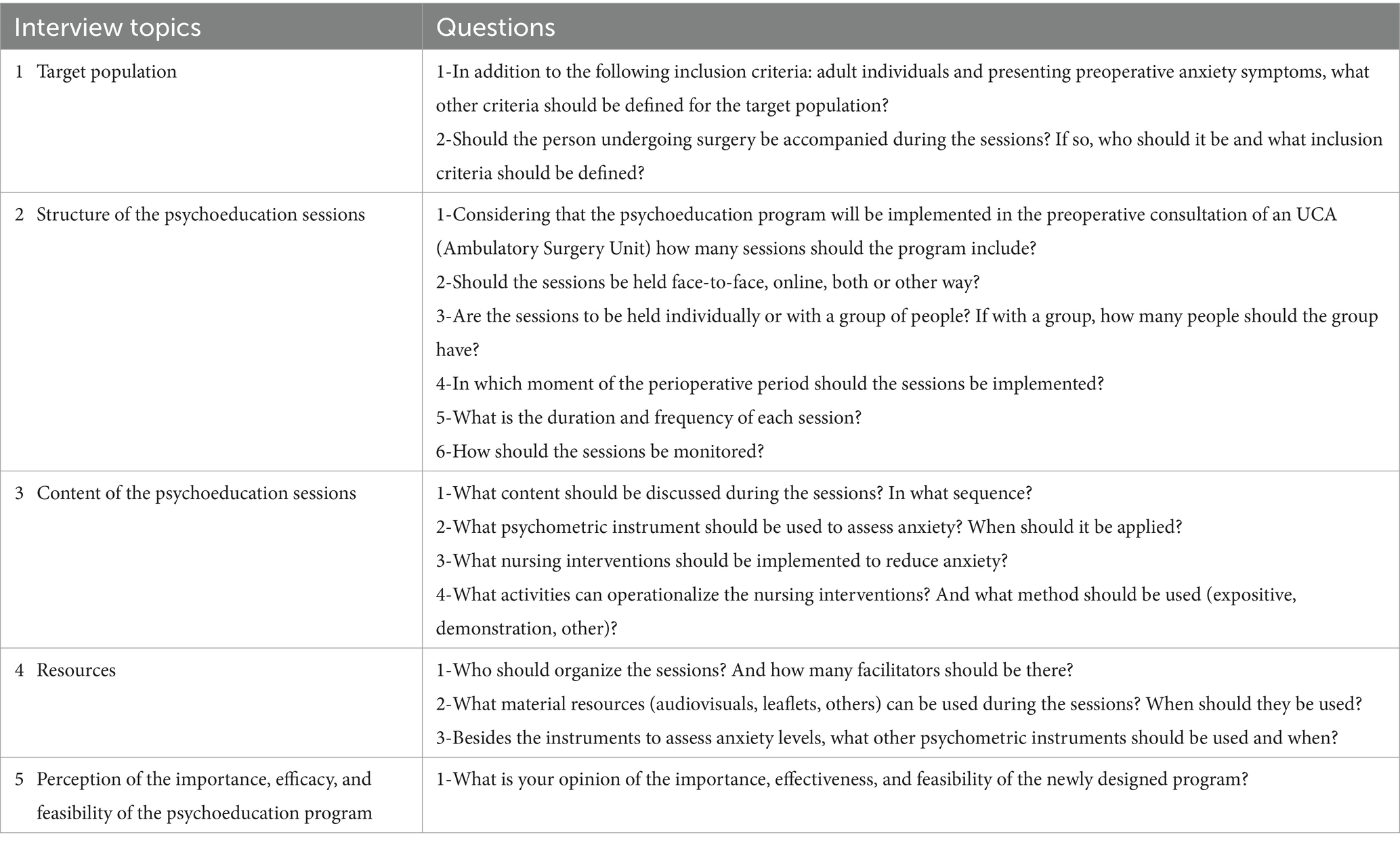

The discussion of ideas during the FG was organized based on a list of topics previously formulated and validated by the members of the project’s research team (see Table 1). During the FG session, all participants had the opportunity to communicate freely, spontaneously, and with motivation, and there was a comfortable atmosphere among the participants during the FG.

The session was videorecorded, and the information was transcribed verbatim and then submitted to content analysis (48). The data were coded independently by two researchers (PO and RP). The results were interpreted and compared, and differences were discussed until a consensus was reached.

At the end of the session, all participants considered that there was no new information about the psychoeducation program that required analysis/discussion, and theoretical saturation was considered to exist, as the mapping of the themes analyzed adequately explained the psychoeducation program. Additionally, information saturation was also validated by peer analysis, that is, by a second researcher who participated in the FG through its content analysis. On the other hand, research was carried out exhaustive research on the phenomenon under study, checking the density of the data obtained and finding no new explanations, interpretations, or descriptions of the phenomenon, in addition to the fact that the FG was supported on the results of the scoping review and, included experienced participants in the surgical context and in mental health, therefore, it was considered that the criterion of saturation was reached.

In operationalizing of the FG, it should be noted that the methods and strategies inherent to qualitative methodology were adopted in the information collection and processing processes, so other elements of the trustworthiness were also considered. Concerning the credibility, we sought to faithfully translate reality, resulting from the ability to establish an empathetic relationship with participants, maintaining an active listening stance and reflection on situations, as well as emotional distancing from the information provided. Reliability validation was achieved by directly questioning participants about the meaning of what they mentioned and by final analysis of the participants’ program design, and still, we detailed the methods and procedures, enabling the study to be reproducible within similar contexts. Regarding transferability, our objective was not to produce generalizations but to understand and gain knowledge about the problem under study in a specific context. However, we believe these study findings find similarities in identical ecologies and circumstances and can contribute to analytical generalizability, and there is potential for it to be transferable.

3 Results

Of the 12 invited nurses, 10 were able to participate in the FG. The most defiant topics were related to the number and frequency of sessions and how to operationalize the content to be discussed in each session.

3.1 Characterization of the participants

Nurses were aged between 26 and 54, with an average age of 41, and only one was male. On average, they had been working for 19 years, and in surgery settings for 15 years. All nurses have experience in the surgical context and in providing care to people with pre-operative anxiety. They are also specialist nurses, with seven nurses were specialized in mental health and psychiatric nursing, and the remaining in medical-surgical nursing. This means that most nurses have advanced knowledge and skills in anxiety reduction strategies, experience in clinical practice in a surgical context, and have carried out preoperative anxiety management interventions.

3.2 Psychoeducation program to reduce preoperative anxiety in adults

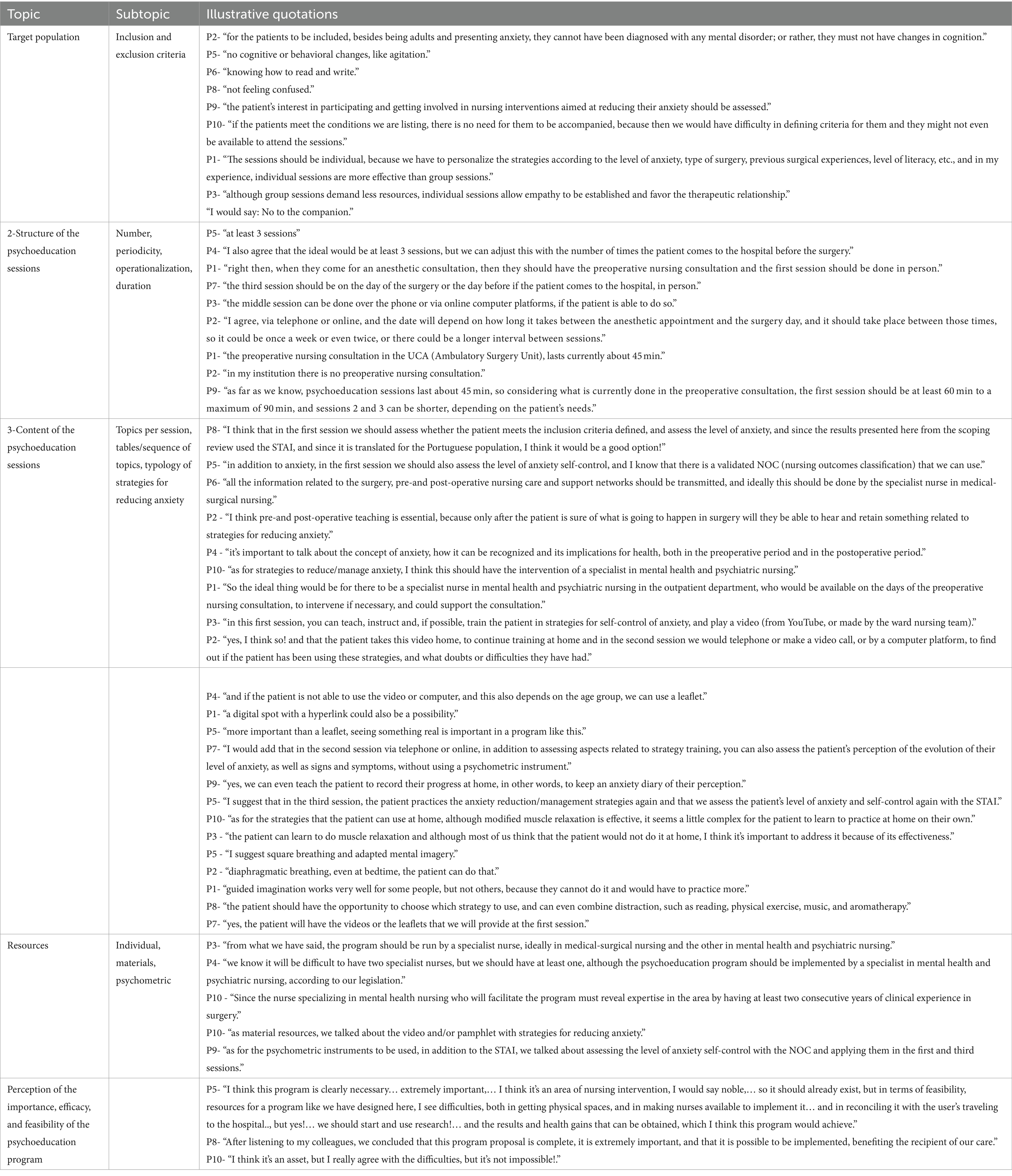

The results are presented in five sections, according to the topics that guided the discussion for the construction of the psychoeducation program, using the participants’ verbatim (Table 2).

Table 2. Design of the psychoeducation program to reduce preoperative anxiety in adults: illustrative quotations.

3.3 Target population

The psychoeducation program is aimed at adults under 65, in a preoperative situation, who show anxiety, the ability to read and write, motivation to participate and signed an informed consent form. They must not have cognitive or behavioral disorders. The sessions are only aimed at the individual who will be submitted to surgery and meets the abovementioned criteria.

3.4 Structure of the psychoeducation sessions

The psychoeducation program should include three individual sessions. The first and third sessions will be in-person, and the second will be via telephone or computer platforms.

Session 1 will be held during the preoperative nursing consultation (60 to 90 min), and Session 2 will take place at an unspecified time (depending on the availability of the nurse and the patient and the timing between the anesthetic consultation and the surgery) and Session 3 on the day of the surgery. Sessions 2 and 3 can be shorter, and the duration will depend on the person’s identified needs.

3.5 Contents of the psychoeducation sessions

In Session 1, the specialist nurse in mental health and psychiatric nursing should sequentially assess whether the person meets the inclusion criteria for the program, the level of anxiety using the STAI in the Portuguese version (19), the level of anxiety self-control using the NOC (Nursing Outcomes Classification) “level of anxiety self-control” (49), teach about preoperative and postoperative care, clarify doubts, teach about anxiety, teach, instruct, and train anxiety management strategies (provide a video, pamphlet or link, to promote training at home). On the other hand, nurses consider that anxiety management strategies should be personalized (Table 2).

In Session 2, the nurse contacts the person by telephone or via a computer platform to assess the perception of the evolution of anxiety and its daily record, monitor the frequency of training and type of strategies used to manage anxiety and clarify doubts.

In Session 3, the nurse supervises the person adopting anxiety management strategies, assesses the level of anxiety using the Portuguese version of the STAI (19), and assesses the level of self-control of anxiety using the NOC.

Regarding the anxiety management strategies, the nurses suggested modified muscle relaxation, diaphragmatic breathing, square breathing, guided imagination, mental imagery, aromatherapy, and the use of distraction techniques (music, physical exercise, reading), so the person should be involved in selecting the strategies to be used, either isolated or combined.

3.6 Resources

A nurse specialized in mental health and psychiatric nursing will be conducting the psychoeducation sessions. This professional nurse who will participate in the three sessions has the appropriate training and skills while working at UCA. Moreover, this professional has clinical practice experience of at least 2 years in a surgical context (Table 2).

Video or pamphlets can be used as material resources.

In sessions 1 and 3, the STAI (19) will assess the level of anxiety and the NOC’s “self-control level of anxiety” (49).

3.7 Perception of the importance, effectiveness, and feasibility of the psychoeducation program

The nurses recognize the importance of designing a psychoeducation program and that the outlined program is potentially effective in reducing preoperative anxiety. However, they acknowledge the difficulty in implementing this program in current healthcare institutions. This difficulty is explained by the fact that this implementation requires conditions adapted to the program, such as human resources, materials, and the professional’s availability of time, coupled with the difficulty of the patient traveling to the hospital.

4 Discussion

In the context of outpatient surgery, the psychoeducation program to reduce preoperative anxiety in adults was designed according to the concept of psychoeducation and the structuring of an intervention program. This design was supported by the results of international research, and its development was conducted and supported in a scoping review (3) carried out for this purpose. Four studies were identified on psychoeducation programs to reduce preoperative anxiety in a hospital setting, with different characteristics, three of which showed a reduction in anxiety levels (50–52).

Notably, in the present study, the nurses prioritized the personalization of their interventions for the target population, stating that the sessions should be individual and mostly face-to-face, favoring the establishment of effective communication that supports the development of a therapeutic and trusting relationship between the nurse and the recipient of care. This is corroborated by other studies (13, 53), which state that people experience surgery differently, so individualized care based on the needs and personal characteristics of the patients is essential and should be considered when selecting the methods to manage anxiety and the quantity and quality of information and ways of providing this information (30).

Research shows that providing information can reduce the patient’s anxiety, and nurses play a crucial role in advising and informing; thus, these professionals need appropriate knowledge and skills (54, 55). In addition, preoperative education should be adapted to each person’s information-seeking styles since the evidence shows that individualized adaptation effectively reduces preoperative anxiety (13).

Thus, a face-to-face preoperative nursing consultation led to the creation of communication channels that stimulate expressing emotions such as anxiety, making it easier for the nurse to identify the person’s needs and enabling care tailored to them (21, 56). Nurses, and more specifically, the specialist nurse in mental health and psychiatric nursing, must develop communication techniques that facilitate interaction with the care client, and they can use interpersonal relationship theory to support their actions (57). This is favored by the organizational model associated with outpatient surgery, as it is person-centered, where face-to-face nursing consultations facilitate quality care (2), making it possible to draw up and implement an individualized nursing process. Nurses will be able to better understand people in the face of the transitions they experience, adopting the role of facilitator of a healthy transition (58), where the person must be empowered with information and have an active role in making decisions about their health (2).

Emphasis was given to the ability to read and write and the absence of changes in cognition, among others, when defining the inclusion criteria. These criteria have been cited in other studies stating that the information provided throughout the peri-operative course should be individualized, considering literacy and cognitive ability (59). On the other hand, other research shows that people with lower education levels are prone to being more anxious (60), likely related to difficulties in understanding the information provided and the lack of confidence in decision-making inherent to the process.

Several studies suggest that preoperative anxiety is present in all surgical patients, regardless of diagnosis (61). These studies also suggest that even in minor surgeries, patients experience high anxiety levels; therefore, all patients who undergo surgery should be targeted for intervention to avoid postoperative complications (62).

Regarding the structure of the psychoeducation sessions, the nurses opted for a short period of psychoeducation (three sessions), called brief psychoeducation (41). Research shows that this type of approach can reduce the incidence and severity of anxiety in the medium term, although the usefulness of brief psychoeducation raises some critical questions (41).

The sessions should be held individually and face-to-face, using the telephone or computerized platforms. The duration of the sessions varies according to the needs identified, with Session 1 being the longest, between 60 and 90 min. Similarly, the scoping review by Oliveira and colleagues (3) showed variations in the frequency, duration, and periodicity of sessions in international psychoeducation programs. Also, some studies applied a single-session intervention lasting on average less than 30 min (13).

Regarding the time for implementing the intervention, the nurses recommend that the first session be held during the preoperative nursing consultation associated with the anesthesia consultation and Session 3 on the day of surgery, with the intermediate session having no fixed time. There was also diversity in the studies included in the scoping review regarding the time interval between the moment of implementation and the date of surgery (3).

Concerning the context in which intervention programs are implemented, the need for a preoperative, face-to-face nursing consultation is highlighted (2, 21), enabling nurses to welcome the patient, assess their specific needs, and provide information related to surgery and preparation for discharge (25). Similarly, the studies included in the scoping review were conducted in an outpatient clinic or during hospitalization (3). In fact, Leal (63) proposes that the preoperative nursing consultation should take place 5 to 6 days before the intervention in the surgery department after the anesthesia consultation.

Regarding the content of the psychoeducation sessions, the nurses established the contents, sequence, and operationalization strategies, namely, what, and when to use the psychometric instruments. The Portuguese version of the STAI was used, similar to the study by Oliveira and colleagues (3). The suggested nursing interventions follow the scope of assessment, information, teaching, instructing, and training (64). Also, they include a pedagogical component about the aspects inherent to the surgical act, the concept of anxiety, and a psychic component oriented toward anxiety management strategies. The nurses also considered how the user’s training in anxiety management strategies should be monitored, stressing that they should participate in selecting each isolated or combined strategy, allowing for individualized and participatory care.

Concerning the anxiety management strategies, the nurses suggested interventions such as modified muscle relaxation, diaphragmatic breathing, guided imagination, and distraction techniques (music, physical exercise, reading), among others. These interventions, suggested by participants, are in line with what has been suggested by the best scientific evidence (3, 43, 65). In this context, systematic preoperative training by nurses, with the support of an information manual and relaxation strategies (muscle relaxation, deep and rhythmic inhalations), proved effective in reducing anxiety levels (66).

The study by Zhuo et al. (13) revealed music as the most used intervention to reduce preoperative anxiety, where patients could select the music; however, massage and video were also commonly used in adult patients. In fact, music is mentioned as a viable option instead of the use of sedative and anxiolytic medication, for reducing preoperative anxiety or at least reducing the need for these drugs (67). However, no nurse in this study suggested massage intervention as an option for inclusion in the program. This might be explained by the fact that most massages need to be performed by someone other than the patient, and the program was tailored only to the recipient of the intervention.

Concerning the resources needed for the psychoeducation program, the participants mentioned that it should be implemented by specialists (mental health and psychiatric nursing). They identified the psychometric instruments to be used and that the interventions could be supported with videos or pamphlets.

In Portugal, the competencies required of a nurse in the outpatient setting are the same as those required in the inpatient setting (25). However, patients have different needs; thus, somewhat different approaches are necessary (63). In addition, it is also crucial to carefully evaluate the identified needs, with the nurse playing a decisive role.

On the other hand, nursing consultations require nurses to have technical, human, and scientific competencies. These are defined in the competencies of the specialist nurse in medical-surgical nursing and comprise several complementing areas, particularly in the peri-operative consultation, where the specialist nurse is autonomous in managing the patient’s therapeutic process (68). The specialist nurse in medical-surgical nursing plays a fundamental role in empowering the person to properly manage the surgical experience, ensuring that they understand the information provided to favor the patient’s self-determination and decision-making (2).

It should also be noted that in the preoperative period, the nurse’s focus is preparing the patient physically and psychologically for surgery, providing them with the tools they need to manage their emotions (63). Therefore, alongside the role of the specialist nurse in medical-surgical nursing, the specialist nurse in mental health and psychiatric nursing emerges, who is the nurse who has the skills to implement a psychoeducation program. Psychoeducational interventions are commonly attributed to mental health nurses (45), aiming at empowering, and enabling people to manage and control their anxiety levels (69). The specialist nurse in mental health and psychiatric nursing is responsible for mobilizing the interaction dynamics with the patient; therefore, this professional is a crucial element in intervening and implementing psychoeducational interventions that promote knowledge, enable understanding and management of the disease process, and empower the patient to adopt appropriate strategies to cope with their living conditions, contributing to the maintenance, improvement, and recovery of their health (33).

Regarding material resources, many institutions use the information leaflet as a standard intervention, increasing the patients’ knowledge but not always reducing people’s anxiety levels because it does not respect their individuality, expectations, and fears (30). The present study adopted passive psychoeducation since the pamphlet is easy to implement and disseminate, enabling it to reach many people at a relatively low cost (70). Passive psychoeducation is common for patients experiencing anxiety, and in addition to the pamphlet, books or videos can be used to provide additional information about this condition (36). This allows the assimilation of the content transmitted verbally (37). However, the information should be as individualized as possible and meet the patient’s needs for quantity and quality (30).

As for the use of video, several studies describe it as an efficient and appropriate audiovisual strategy for transmitting information to patients, thus reducing anxiety levels (71).

Therefore, nurses advocate the use of passive psychoeducational interventions and active psychoeducational interventions (36) in their programs, using a collaborative approach (33).

The participants also expressed their perception of the importance, effectiveness, and feasibility of the psychoeducation program, stating that they are aware of the importance and relevance of its development and its impact on the delivery of nursing care and in reducing the patient’s anxiety levels. However, they also identify difficulties in its implementation, mainly related to material and human resources and nurses’ time availability.

In Portugal, surgery is primarily performed in an outpatient setting (2), so developing adapted professional practice and more research in this context is recommended. However, according to Leal (63), in the Portuguese context, the reduction in hospitalization stays means that nurses have less time to invest in pre-and postoperative care, increasing the financial burden derived from the incidence of late complications due to the patient’s lack of knowledge. The study by Lopes (2) on face-to-face nursing consultations for people undergoing outpatient surgery identifies some difficulties in its implementation, overlapping some of the difficulties expressed by the nurses in this study. For example, the patient’s travel to the consultation site, the lack of adjustment of parameterization and organization of the consultation, the training and time availability of the nurses, inadequate physical space, and a lack of human resources are mentioned.

Despite the difficulties expressed by the nurses, the feasibility and effectiveness of the psychoeducation program are perceived as positive, and the advantages are recognized since less anxious patients are more prone to cooperate, reducing surgery time, the need for drugs, and the number of surgical complications (27).

Non-pharmacological approaches to reducing anxiety, such as psychoeducation, are cost-effective, minimally invasive, and have a low risk of adverse effects (13). However, one of the major obstacles to implementing and using psychoeducation is likely the lack of knowledge and skills in its execution due to a lack of training opportunities (72, 73). In addition, nurses need specific training in strategies to reduce preoperative anxiety (66). Therefore, to implement anxiety management strategies effectively, and more specifically, regarding the necessary training, the specialist nurse in mental health and psychiatric nursing has the academic training and regulated skills (44). Concerning the resources, it should be noted that it will be necessary to provide an appropriate setting specifically identified for this purpose, having the necessary equipment (e.g., couch) to implement each strategy to reduce anxiety and ensure that the specialist nurse in mental health and psychiatric nursing has time available to implement each session. But the human resources are guaranteed, as the UCA has more than one nurse specialist in mental health and psychiatric nursing, with over 2 years of clinical practice in surgery. Regarding the necessary support, the hospital organization where the nursing psychoeducation program will be implemented, demonstrates interest through the institutional policies adopted and recognizes the clinical potential in health gains for the surgical client by investing in and valuing this type of intervention. So, we consider that the conditions for implementing the psychoeducation program are met, namely with authorization from the ethics committee and the UCA Clinical Director.

The knowledge that has emerged from this study supports the implementation of the last stage of the broader research project, aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of the psychoeducation program, providing a significant contribution to the knowledge of nursing as a discipline. It will support the development of the competencies required for nurses’ care practices in surgical settings, where specialist nurses in mental health and psychiatric nursing play a crucial role in reducing the emotion, anxiety. Most importantly, helping reduce/manage the anxiety levels of the recipient of care will enable the transferability of knowledge to nurses’ professional practice.

4.1 Limitations of the study

Despite nurses’ extensive professional experience in surgical settings and being familiarized with the topics under discussion, they originate from different hospital institutions with specific realities. This can enrich the discussion by sharing different perspectives. However, the fact that some of the nurses do not have a preoperative consultation established or the same functioning, especially concerning outpatient surgery (complexity of the surgeries, consultation scheduling, among others), may have also hindered the ability of some nurses putting into perspective the implementation of the outlined psychoeducation program.

4.2 Implications for practice and future research

Notably, the design of the newly constructed psychoeducation program was developed by nurses experienced in surgery and mental health and psychiatric nursing, aiming at its implementation by nurses in different outpatient surgery settings. But it could be complemented or extended to other professionals within a multidisciplinary health team.

Thus, nurses are actively involved in interventions to reduce preoperative anxiety in adults. However, despite the advantages of being a personalized design and an unprecedented advance in research in Portugal, comparing this study to other studies can be challenging. Scientific evidence has shown that psychoeducation as a health intervention produces positive results manifested in multiple ways, impacting the individual/family’s quality of life. However, comparing, and systematizing results poses some problems deriving from the diversity of methodologies used in research (40).

Therefore, research must focus on effective non-pharmacological strategies to reduce preoperative anxiety, particularly the effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions, which are less expensive than pharmacological interventions (70). In addition, nurses should invest in psychoeducation and anxiety management strategies training.

In light of the above-mentioned, a new study is planned to evaluate the effectiveness of the designed psychoeducation program, expanding the search for evidence on the effectiveness of psychoeducational programs, considering their specific content, the duration of the psychoeducational intervention, and the evaluation methodology.

On the other hand, these study results will support nurses’ clinical practice in a surgical context, boosting health gains for people undergoing surgery. Moreover, these outcomes may raise awareness of the need for specialist nurses in mental health and psychiatric nursing to practice their skills. This will enable the individual to experience the transition processes associated with surgery in a healthier way, promoting more adaptive responses and enhancing their quality of life.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Comissão de Ética da Sociedade Portuguesa de Enfermagem de Saúde Mental (ethical approval number: 03/2023) approved this study on 14/03/2023. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

PO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RP: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RS: Project administration, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. CS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This article was supported by National Funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., within CINTESIS, R&D Unit (reference UIDB/4255/2020 and reference UIDP/4255/2020).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants of this study and financial supporters. The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of the professional translator Maria do Amparo Alves in the translation/editing of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Boltz, M, Capezuti, L, Fulmer, TT, and Zwicker, D. Evidence-based geriatric nursing protocols for best practice. New York: Springer Publishing Company (2016).

2. Lopes, E. A consulta de enfermagem presencial à pessoa submetida a cirurgia ambulatória. [Master’s thesis]. Viana do Castelo (Portugal): Instituto politécnico de Viana do Castelo, Escola Superior de Saúde (2020). Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11960/2510.

3. Oliveira, P, Porfírio, C, Pires, R, Silva, R, Carvalho, JC, Costa, T, et al. Psychoeducation programs to reduce preoperative anxiety in adults: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 20:327. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20010327

4. Abate, SM, Chekol, YA, and Basu, B. Global prevalence and determinants of preoperative anxiety among surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg Open. (2020) 25:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijso.2020.05.010

5. Bedaso, A, and Ayalew, M. Preoperative anxiety among adult patients undergoing elective surgery: a prospective survey at a general hospital in Ethiopia. Patient Saf Surg. (2019) 13:198. doi: 10.1186/s13037-019-0198-0

6. Nigussie, S, Belachew, T, and Wolancho, W. Predictors of preoperative anxiety among surgical patients in Jimma University specialized teaching hospital, South Western Ethiopia. BMC Surg. (2014) 14:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-14-67

7. Oliveira, E. Ansiedade Pré-operatória. [Master’s thesis]. Porto (Portugal): Universidade do Porto, p. 22. (2011). Available at: https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/bitstream/10216/62152/2/Ansiedade%20PrOperatria.pdf.

8. Porfírio, C. Programa de psicoeducação de redução da ansiedade em adultos no pré-operatório: uma scoping review. [Master’s Thesis on the Internet]. Porto (Portugal): Escola Superior de Enfermagem do Porto, p. 201. (2020). Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/35002.

9. Alanazi, AA. Reducing anxiety in preoperative patients: a systematic review. Br J Nurs. (2014) 23:387–93. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2014.23.7.387

10. Gümüs, K. The effects of preoperative and postoperative anxiety on the quality of recovery in patients undergoing abdominal surgery. J Perianesth Nurs. (2021) 36:174–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2020.08.016

11. Kassahun, WT, Mehdorn, M, Wagner, TC, Babel, J, Danker, H, and Gockel, I. The effect of preoperative patient-reported anxiety on morbidity and mortality outcomes in patients undergoing major general surgery. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:6312. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-10302-z

12. Agüero-Millan, B, Abajas-Bustillo, R, and Ortego-Maté, C. Efficacy of nonpharmacologic interventions in preoperative anxiety: a systematic review of systematic reviews. J Clin Nurs. (2023) 32:6229–42. doi: 10.1111/jocn.16755

13. Zhuo, Q, Ma, F, Cui, C, Bai, Y, Hu, Q, Hanum, AL, et al. Effects of pre-operative education tailored to information-seeking styles on pre-operative anxiety and depression among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. (2023) 10:174–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2023.03.015

14. Wilson, CJ, Mitchelson, AJ, Tzeng, TH, el-Othmani, MM, Saleh, J, Vasdev, S, et al. Caring for the surgically anxious patient: a review of the interventions and a guide to optimizing surgical outcomes. Am J Surg. (2016) 212:151–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.03.023

15. Bayrak, A, Sagiroglu, G, and Copuroglu, E. Effects of preoperative anxiety on intraoperative hemodynamics and postoperative pain. J. Coll. Phys. Surg. Pak. (2019) 29:868–73. doi: 10.29271/jcpsp.2019.09.868

16. Chen, YYK, Soens, MA, and Kovacheva, VP. Less stress, better success: a scoping review on the effects of anxiety on anesthetic and analgesic consumption. J Anesth. (2022) 36:532–53. doi: 10.1007/s00540-022-03081-4

17. American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5: Manual Diagnóstico e Estatístico de Transtornos Mentais. Virginia, US: American Psychiatric Association (2014).

18. Spielberger, CD. Theory and research on anxiety In: C Spielberger, editor. Anxiety and behavior. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press (1972). 3–19.

19. McIntyre, L, and McIntyre, S. State trait anxiety inventory (STAI). Portugal: Universidade do Minho (1995).

20. Santos, TT. Ansiedade Pré-Operatória: O reflexo no doente cirúrgico. [master’s thesis]. Leiria (Portugal): Escola Superior de Saúde de Leiria. (2019). Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.8/4714. (Accessed Oct 9, 2023).

21. Machado, S. Ansiedade do Doente no Pré-Operatório de Cirurgia de Ambulatório: Influência da Consulta de Enfermagem. [Master’s thesis]. Coimbra (Portugal): Escola Superior de Enfermagem de Coimbra, p. 86. (2016). Available at: http://web.esenfc.pt/?url=Vhg8OmDG (Accessed Oct 9, 2023).

22. De Sousa Ferreira, CVA, Da Ferreira, SSC, and De Pimentel, LVC. O pré-operatório e a ansiedade do paciente: a aliança entre o enfermeiro e o psicólogo. Rev SBPH, No. 13. pp. 282–298. (2010). Available at: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1516-08582010000200010&lng=pt (Accessed October 12, 2023).

23. Williams, JB, Alexander, KP, Morin, JF, Langlois, Y, Noiseux, N, Perrault, LP, et al. Preoperative anxiety as a predictor of mortality and major morbidity in patients >70 years of age undergoing cardiac surgery. Am. J. Cardiol. (2013) 111:137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.08.060

24. Bandelow, B, Michaelis, S, and Wedekind, D. Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2022) 19:93–107. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.2/bbandelow

25. Associação dos Enfermeiros de Sala de Operações Portugueses. In Enfermagem Perioperatória—Da Filosofia à Prática dos Cuidados. Lusodidacta: Loures, Portugal (2006).

26. Freiberger, M, and Mudrey, E. A importância da visita pré-operatória para sistematização da assistência em enfermagem perioperatória. Rev Cien Faculd Educ Meio Ambiente. (2011) 2:1–26. doi: 10.31072/rcf.v2i2.96

27. Fonseca, M. (2014). A influência do ensino pré-operatório de enfermagem na redução da ansiedade intra-operatória em cirurgia ambulatória de extração de catarata. Enformação. Agosto-outubro; 28-34 (2014). Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.17/1954.

28. Luna, A. (2014). Importância da visita pré-operatória de enfermagem: a satisfação do cliente [master’s thesis]. Setúbal (Portugal): Instituto Politécnico de Setúbal, Escola Superior de Saúde, p. 214. (2014). Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/6992 (Accessed Oct 9, 2023).

29. Gonçalves, M, and Cerejo, M. Construção e validação de uma Escala de Avaliação de Informação Pré-Operatória. Rev Enferm Ref. (2020) 2020:67. doi: 10.12707/RV20067

30. Mendes, A, Silva, A, Nunes, D, and Fonseca, G. Influência de um Programa Psico-educativo no Pré-operatório nos Níveis de Ansiedade do Doente no Pós-operatório. Rev Enferm Ref. (2005) 2:9–14.

31. Firmino, H, Santiago, L, Andrade, J, and Nogueira, V. Psiquiatria Básica em Medicina Familiar. 1st ed. New York, Lidel: (2019).

32. Anderson, CM, Hogarty, GE, and Reiss, DJ. Family treatment of adult schizophrenic patients: a psycho-educational approach. Schizophr Bull. (1980) 6:490–505. doi: 10.1093/schbul/6.3.490

33. Fortes, BMP, De Marques, MF, Dos, SR, and Malheiro, MLR. Eficácia da intervenção psicoeducativa na pessoa com sintomatologia depressiva e ansiosa. Rev Am Saúde Envelhecimento. (2022) 7:357–74. doi: 10.24902/r.riase.2021

34. Colom, F. Keeping therapies simple: psychoeducation in the prevention of relapse in affective disorders. Br J Psychiatry. (2011) 198:338–40. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.090209

35. Chien, WT, and Lee, IYM. The mindfulness-based psychoeducation program for Chinese patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. (2013) 64:376–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.002092012

36. Sarkhel, S, Singh, O, and Arora, M. Clinical practice guidelines for psychoeducation in psychiatric disorders general principles of psychoeducation. Indian J Psychiatry. (2020) 62:319–23. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_780_19

37. Lemes, CB, and Neto, JO. Aplicações da psicoeducação no contexto da saúde. Temas Psicol. (2017) 25:17–28. doi: 10.9788/TP2017.1-02

38. Amaral, A, Almeida, E, and Sousa, L. Intervenção psicoeducacional In: C Sequeira and F Sampaio, editors. Enfermagem em Saúde Mental: Diagnósticos e Intervenções. 2nd ed. Virginia: LIDEL (2021)

39. Duman, Z, and Dorttepe, Z. Psicoeducação em doenças mentais, In Pesquisas sobre Ciência e Arte na Turquia do Século 21. Gece Kitapligi. (2017). Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321671044_Psyhoeducation_in_mental_illnesses (Accessed Oct 7, 2023).

40. Godoya, D, Eberhard, A, Abarca, F, Acuña, B, and Muñoz, R. Psicoeducación en salud mental: una herramienta para pacientes y familiares. Rev Med Clin Condes. (2020) 31:169–73. doi: 10.1016/j.rmclc.2020.01.005

41. Zhao, S, Sampson, S, Xia, J, and Jayaram, MB. Psychoeducation (brief) for people with serious mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 2015:4. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010823.pub2

42. Wong, SYS, Yip, BHK, Mak, WWS, Mercer, S, Cheung, EYL, Ling, CYM, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. group psychoeducation for people with generalised anxiety disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. (2016) 209:68–75. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.166124

43. Gomes, JAL, and Pergher, GK. A TCC no pré e pós-operatório de cirurgia cardiovascular. Rev Bras Terap Cogn. (2010) 6:173–94.

44. Klainin-Yobas, P, Ignacio, J, He, HG, Lau, Y, Ngooi, BX, and Koh, SQD. Effects of a stress-management program for inpatients with mental disorders. Biol Res Nurs. (2015) 18:213–20. doi: 10.1177/1099800415595877

45. Ordem dos Enfermeiros. Regulamento de Competências Específicas do Enfermeiro Especialista em Enfermagem de Saúde Mental e Psiquiátrica. Ordem Enferm, p. 7. (2018).

46. Silva, IS, Veloso, AL, and Keating, JB. Focus group. Considerações teóricas e metodológicas. Rev Lusófona Educ. (2014) 26:175–90.

49. Sampaio, FMC, Araújo, OSS, Sequeira Ca Da, C, Lluch Canut, MT, and Martins, T. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of NOC outcomes “anxiety level” and “anxiety self-control” in a Portuguese outpatient sample. Int J Nurs Knowl. (2017) 29:184–91. doi: 10.1111/2047-3095.12169

50. Román, C, Martínez, EP, González, ST, Vicente, MM, and Rodríguez-Marín, J. Psychological effects of a structured programme for preparing bariatric surgery patients. Ansiedad Estres. (2012) 18:231–9.

51. Shakeri, M. Study the effect of planned and writing training on the anxiety of patients undergoing orthopedic surgery. Biomed Pharmacol J. (2015) 8:125–30. doi: 10.13005/bpj/568

52. Malek, N, Zakerimoghadam, M, Esmaeili, M, and Kazemnejad, A. Effects of nurse-led intervention on patients’ anxiety and sleep before coronary artery bypass grafting. Crit Care Nurs Q. (2018) 41:161–9. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000195

53. Gezer, D, and Arslan, S. The effect of education on the anxiety level of patients before thyroidectomy. J Perianesth Nurs. (2019) 34:265–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2018.05.017

54. Sundus, HA, and Jacoub, SM. Effectiveness of preoperative psycho-educational program on stress of cardiac surgery patients. Iraqi Natl. J. Nurs. Spec. (2015) 28:83.

55. Xu, Y, Wang, H, and Yang, M. Preoperative nursing visit reduces preoperative anxiety and postoperative complications in patients with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Medicine. (2020) 99:e22314. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022314

56. Formiga, N. Os estudos sobre empatia: reflexões sobre um construto psicológico em diversas áreas científicas. Psicologia.pt – o portal dos psicólogos, pp. 1–14. (2012). Available at: https://www.psicologia.pt/artigos/textos/A0639.pdf.

57. Peplau, H. Interpersonal relations in nursing: A conceptual frame of references for psychodynamic nursing. New York: Springer Publishing Company (1988).

58. Meleis, A. Transitions theory: Middle-range and situation-specific theories in nursing research and practice. New York: Springer Publication (2010).

59. Samuelsson, KS, Egenvall, M, Klarin, I, Lökk, J, Gunnarsson, U, and Iwarzon, M. The older patient’s experience of the healthcare chain and information when undergoing colorectal cancer surgery according to the enhanced recovery after surgery concept. J Clin Nurs. (2018) 27:e1580–8. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14328

60. Jin, Z, Ding, P, Liu, L, Yang, Q, Chen, M, and Liu, L. Factors related to anxiety and depression in patients undergoing adrenalectomy in 220 Chinese people. Int J Clin Exp Med. (2015) 8:8168–72.

61. Renouf, T, Leary, A, and Wiseman, T. Do psychological interventions reduce properative anxiety? Br J Nurs. (2014) 23:1208–12. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2014.23.22.1208

62. Pereira, L, Figueiredo-Braga, M, and Carvalho, IP. Preoperative anxiety in ambulatory surgery: the impact of an empathic patient-centered approach on psychological and clinical outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. (2016) 99:733–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.11.016

63. Leal, M. Cirurgia ambulatória: estaremos atentos ao seu impacto sobre a enfermagem? Pensar Enfermagem. (2006) 10:67–74.

64. Garcia, T., Galvão, M., Nóbrega, M.M., and Cubas, M. Classificação internacional para a prática de enfermagem, versão 2019/2020, p. 28. (2020).

65. Wang, S, Timmer, J, Scheider, S, Sporrel, K, Akata, Z, and Kröse, BJA. A data-driven study on preferred situations for running. Wiardi Beckman foundation (Wiardi Beckman foundation). (2018).

66. Pinar, G, Kurt, A, and Gungor, T. The efficacy of preopoerative instruction in reducing anxiety following gyneoncological surgery: a case control study. World J Surg Oncol. (2011) 9:38. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-38

67. Gokçek, E, and Kaydu, A. The effects of music therapy in patients undergoing septorhinoplasty surgery under general anesthesia. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. (2019) 86:419–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2019.01.008

68. dos Enfermeiros, O. Regulamento n.° 429/2018. Regulamento de competências específicas do enfermeiro especialista em Enfermagem Médico-Cirúrgica. Diário da República n° 135/2018, Série II de 2018-07-16. (2018).

69. Brazão, I. Psicoeducação no controle da ansiedade na mulher com cancro da mama: Proposta de intervenções especializadas em enfermagem master’s thesis. Portalegre (Portugal): Instituto Politécnico de Portalegre, p. 120. (2020). Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/33797 (Accessed Oct 9, 2023).

70. Donker, T, Griffiths, KM, Cuijpers, P, and Christensen, H. Psychoeducation for depression, anxiety, and psychological distress: a meta-analysis. BMC Med. (2019) 7:79. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-79

71. Jlala, HA, French, JL, Foxall, GL, Hardman, JG, and Bedforth, NM. Effect of preoperative multimedia information on perioperative anxiety in patients undergoing procedures under regional anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. (2010) 104:369–74. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq002

72. Motlova, LB, Balon, R, Beresin, EV, Brenner, AM, Coverdale, JH, Guerrero, APS, et al. Psychoeducation as an opportunity for patients, psychiatrists, and psychiatric educators: why do we ignore it? Acad Psychiatry. (2017) 41:447–51.

Keywords: adult, anxiety, nursing, preoperative period, program development, psychoeducation

Citation: Oliveira P, Pires R, Silva R and Sequeira C (2024) Design of a nursing psychoeducation program to reduce preoperative anxiety in adults. Front. Public Health. 12:1391764. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1391764

Edited by:

Abdulqadir J. Nashwan, Hamad Medical Corporation, QatarReviewed by:

Aneta Grochowska, University of Applied Sciences in Tarnow, PolandGeorge Joy, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar

Copyright © 2024 Oliveira, Pires, Silva and Sequeira. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Palmira Oliveira, cGFsbWlyYW9saXZlaXJhQGVzZW5mLnB0

Palmira Oliveira

Palmira Oliveira Regina Pires

Regina Pires Rosa Silva

Rosa Silva Carlos Sequeira

Carlos Sequeira