- 1Institute of Higher Education, Changsha University, Changsha, China

- 2West Virginia University School of Medicine, Morgantown, WV, United States

- 3Department of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry, West Virginia University School of Medicine, Morgantown, WV, United States

- 4Mental Health & Counseling, Yale Health, New Haven, CT, United States

- 5School of Economics and Management, Changsha University, Changsha, China

Objective: To conduct a systematic literature review of education and training (E&T) programs for telemental health (TMH) providers in the past 10 years to qualitatively clarify field offerings and methodologies, as well as identify areas for future growth.

Methods: We searched five major electronic databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, CINAHL, and Web of Science for original publications on TMH E&T from January 2013 to May 2023. We extracted information from each publication and summarized key features of training programs including setting, target group, study aims, training modality, methods of assessing quality, and outcomes.

Results: A total of 20 articles were selected for the final review. Articles meeting inclusionary criteria were predominantly comprised of case studies and commentaries, focused on a TMH service/practice for a specific region/population, and were performed after 2020. All of the selected studies demonstrated a significant increase in the measured knowledge, skills, and abilities of the participants after TMH training. Nevertheless, there remains a lack of standardization of training methodologies, limited sample sizes and demographics, variability in study methodologies, and inconsistency of competency targets across studies.

Conclusion: This systematic review highlighted the diversity of methods for TMH E&T. Future research on this topic could include more varied and larger-scale studies to further validate and extend current findings, as well as explore potential long-term effects of TMH training programs on both provider attitudes and patient outcomes.

1 Introduction

Telemental health (TMH) is used to refer to mental health services that are provided via telecommunications technologies (e.g., email, video, telephone, messaging programs). This field has demonstrated rapid development over the past three decades (1, 2). Advances in technology have enabled real-time distant consultations, assessments, therapy, and training opportunities. The distinction between traditional mental health providers and TMH lies in the mode of service delivery. Traditional mental health providers usually supply in-person services while TMH providers utilize telecommunication technologies for remote mental health service. While TMH continues to gain wider acceptance and adoption, driven by factors such as the need for increased access to mental health services, advancements in technology, and recognition of its efficacy and effectiveness (3), it has also faced criticism, especially on its use in psychotherapy and psychodynamic procedures (4, 5).

The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated the implementation and adoption of TMH as an essential means of delivering mental healthcare. Many studies showed that when properly adapted from in-person practices, TMH approaches effectively promoted the mental health and well-being of participants with various mental problems (6). To ensure proper adaptation, a growing number of research studies detailed how TMH has been implemented, adopted, and perceived by diverse individuals and providers (7–9).

Many studies have demonstrated that education and training (E&T) in TMH is needed, as a lack of education can lead to suboptimal care and a lack of knowledge about how to address technological-related issues. Contrastingly, proper E&T has been suggested as positively impacting provider attitudes and knowledge, and subsequently patient outcomes (10–12). However, there is a lack of standardization in TMH E&T (13, 14). Some researchers have attempted to propose core competencies for TMH (12, 15–18) to include, but not necessarily be limited to, knowledge of the literature and evidence-based practices for different demographic characteristics, TMH modalities, and settings; evidence-informed methods of adapting in-person techniques (e.g., clinical work, interpersonal skills, rapport, communication) for digital administration; ethics of TMH practice; legality of TMH practice (e.g., cross-jurisdiction practice, data security); professionalism in practice, selection and troubleshooting of technology; diversity considerations of unique populations; administrative tasks (e.g., documentation, billing); and interdisciplinary collaboration. Nevertheless, to date, there has been little success in establishing standardized competencies, let alone efficient, scalable strategies for training existing TMH providers in said competencies. Additionally, very few E&T programs are dedicated to long-term career development for future TMH providers (19). For example, limited TMH education has been suggested as available in graduate education, affecting a provider’s knowledge and future use of TMH technologies in clinical care. This lack of training may be partially due to the relative youth of the field though has been suggested as an issue in need of addressing (20, 21).

To meet the increasing demand for evidence-based TMH providers, it is important to develop evidence-informed methods of E&T. The evidence-informed usage of TMH can guide ethical, legal, evidence-informed, and safe provider usage to not only maximize outcomes, but to reduce challenges that arise from the use of technology in clinical practice (22–24). Unfortunately, no known review has consolidated literature to clarify current field offerings and future directions. Therefore, there is a need for a systematic review concerning E&T of TMH providers to identify currently available programs, strengths and weaknesses of said programs, and the ongoing needs of the field. This information will help inform future adjustments in training design to better reflect the rapid changes in the field of TMH.

The objective of this study was to review and aggregate recent literature on TMH E&T to clarify field offerings and methodologies, as well as identify areas for further growth. Several research questions were derived to guide analyses: (a) who provided TMH E&T (i.e., setting), (b) who was the TMH E&T provided to, (c) what was the aim of TMH E&T, (d) how was the TMH E&T provided, (e) how was the quality of the TMH E&T assessed, and (f) what were the outcomes of the TMH E&T. Given limited prior literature to guide research questions, the current study was viewed as exploratory.

2 Methods

2.1 Study type

This study was conducted as a systematic review. The method of a systematic review was chosen over other methods, such as a scoping review, due to its rigorous and comprehensive approach in synthesizing existing literature to address focused research questions rather than summarize a broader and more diverse field of study.

2.2 Search strategy

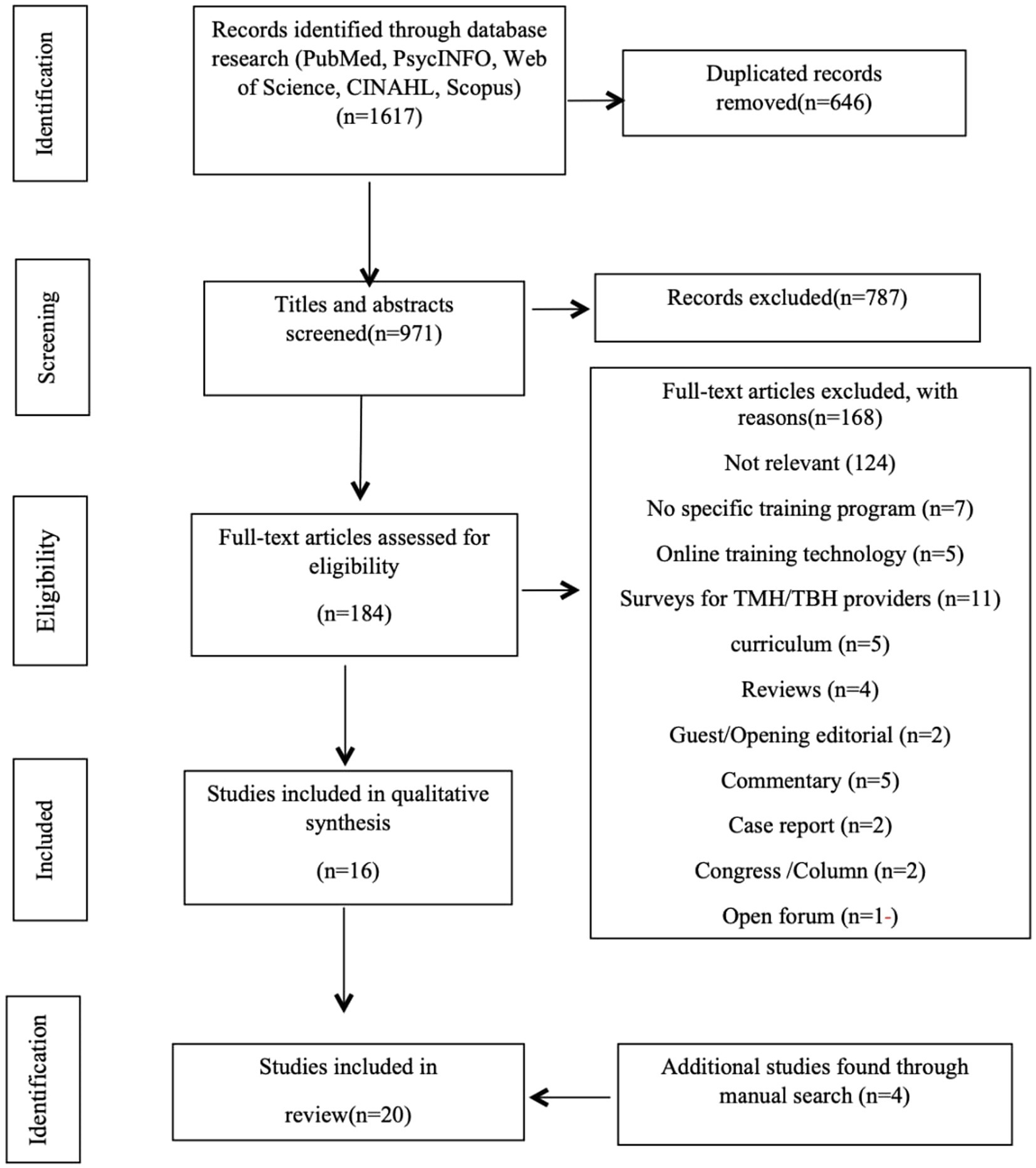

This review was conducted according to the PRISMA standard with the involvement of every member of the research team (25). The screening process for determining which papers were to be analyzed in this study is depicted in Figure 1. We used the PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases to search TMH related English language articles published from January 2013 to May 2023. Keywords utilized were telemental health, TMH, telepsychology, telepsychiatry, telebehavioral health, TBH, and mobile mental health; all of these keywords were also separately paired with “education” and “training” to further expand the search. The full search strategies for each database, including complete keyword combinations, Boolean operator usage, and filtering criteria, can be found in the Supplementary material. Initially, title and abstract screening were conducted to assess relevance of the articles in the search results. Then, full-text screening was performed for eligible articles. Every article reviewed in this process was screened independently by at least two study members with any disagreements resolved through a group consensus. The Systemic Review Accelerator (SRA) was a computer tool that was utilized to facilitate this process.

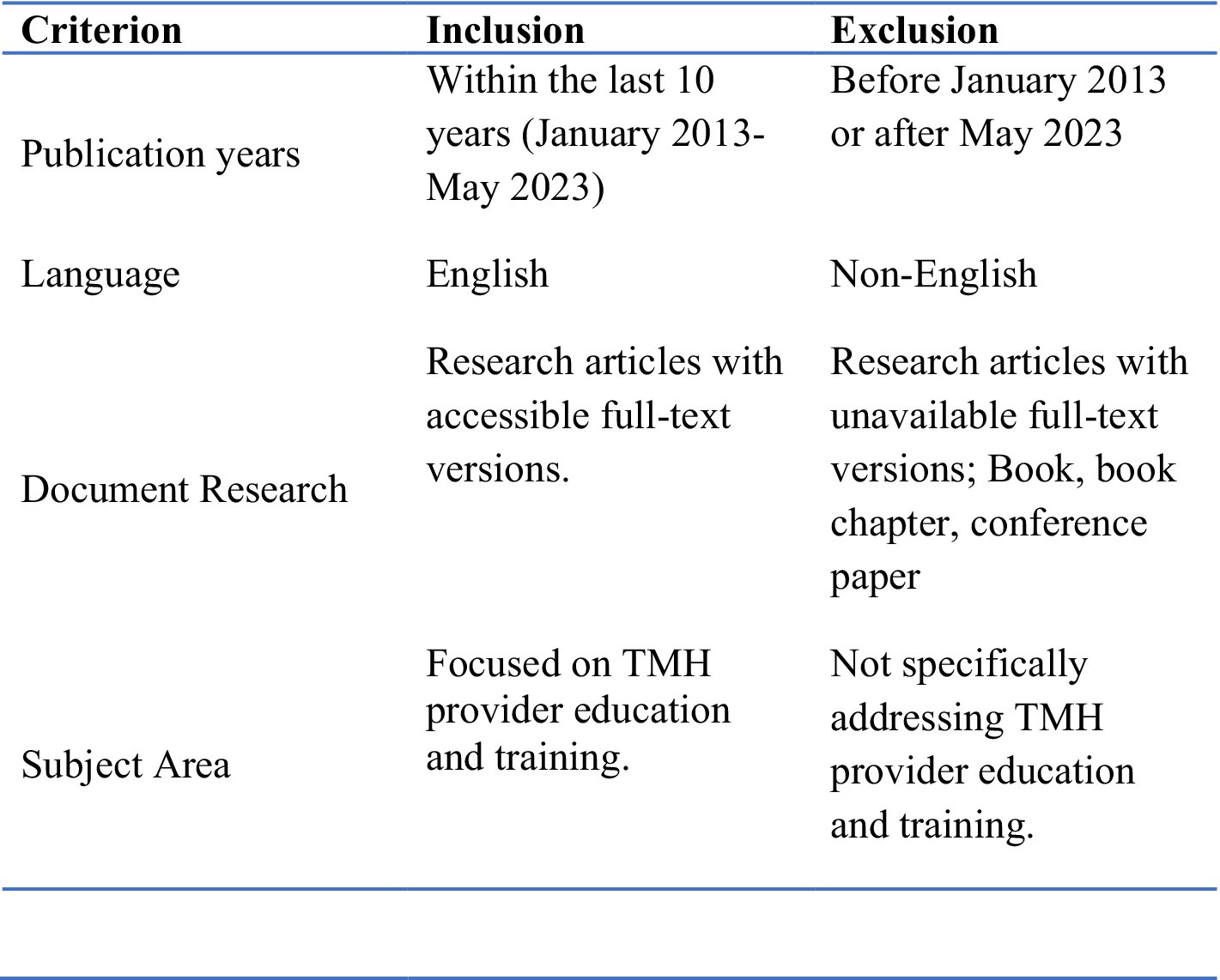

2.3 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were based on relevance to education, training and competency development of TMH providers. Studies providing a description of education or training programs for mental health-focused telehealth providers were included. Contrastingly, articles focusing on only providers’ experiences or perspectives of TMH E&T were excluded. Papers that utilize remote or online technology to train providers in the fields of mental health or psychiatric informatics were also excluded, unless they were sufficient to cover all necessary training content and requirements of TMH itself. Papers examining the educational needs or the level of knowledge and skills of providers in TMH were also excluded if they were not in the context of a specific training program.

The current study elected to review the literature from only the past decade, as other reviews have covered July 2003 to March 2013 (3). Due to the rapid advances, a review of the last ten years is believed to better reflect the current status of TMH E&T than prior research.

2.4 Quality of studies

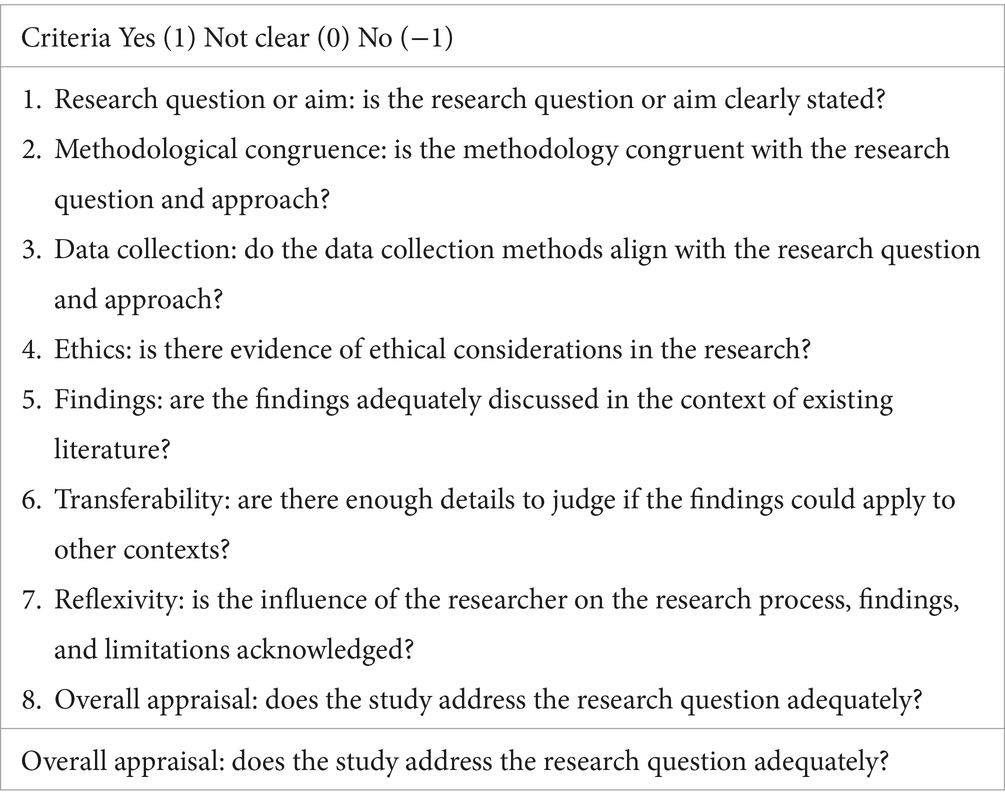

Each article meeting inclusionary criteria was assessed for relevance, quality, and contribution to the topic of TMH providers’ education, training, and competency development. The quality of studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Appraisal and Review Instrument (JBI QARI) Critical Appraisal checklist for Interpretive and Critical Research (Attachment). This quality assessment tool was modified for this systematic review; less relevant elements were removed as based upon consensus by the authors. The papers in this study were subsequently qualitatively analyzed through this tool to identify factors relevant to address research questions (See Tables 1, 2).

Table 2. Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Appraisal and Review Instrument (JBI QARI) critical appraisal checklist for interpretive and critical research.

3 Results

3.1 Review composition

The electronic searches identified 971 articles. An additional 4 were identified by a manual search from references. The abstracts of all 971 papers were reviewed with 184 meeting the inclusion criteria and 787 excluded. Based on full-text reading of the remaining 184, a further 168 papers were excluded, adding 4 additional records searching for manually and leaving a final set of 20 studies for inclusion in this review (Figure 1).

3.2 Characteristics of studies

A summary of the remaining 20 study’s objective, target group, training modality, outcomes and other characteristics can be seen in Table 3.

Despite the analysis spanning ten years, review suggested that a majority (i.e., n = 14, 70%) of articles meeting inclusionary criteria were published following 2020.

3.3 Providers of TMH E&T

The TMH training programs were held in various settings, including, but not limited to university counseling centers, community clinics, private practices, VA hospitals, and prisons/jails. A significant portion of the settings were affiliated with academic institutions. Many clinical service settings, such as VA, expanded TMH E&T during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the urgent need for TMH at that time. While beneficial to all patient demographics, the option for TMH was especially useful for certain populations, such as children and adolescents (29), people with social anxiety disorder (30), and individual experiencing schizophrenia (44).

3.4 Users of TMH E&T

The target trainees were diverse and included military personnel, doctoral students, healthcare providers, interdisciplinary practitioners, and a mix of students and qualified professionals. The majority, however, were psychology/social worker students or clinicians. Of note, each program had a training focus area and goals unique to the training program.

3.5 Aims of TMH E&T

Almost all training programs included in the study focused on enhancing the skills and knowledge of TMH providers. Study objectives collectively aimed to improve the reach of mental health professionals, especially in the context of public health crises and underserved communities, while leveraging technology for future training and service delivery. While some studies described specific training activities among specific trainee populations (e.g., psychology practicum training for specific interventions, telepsychiatry) (27, 37), others assessed the feasibility and efficacy of TMH E&T more broadly among different cultural (30), and clinical settings (34). A few studies focused on promoting access to mental health services through telehealth, addressing barriers (31), and examining participant experiences with online training tools (35). Additionally, some studies focused on comparing different training modalities, and exploring factors influencing telepsychology training from the perspective of doctoral students (40).

3.6 Methods of providing TMH E&T

While the training modalities all included virtual components such as web-based courses, live sessions or asynchronous audio-video communications, there were some notable differences. For example, some programs incorporated specialized in-person training (36), or diverse formats (e.g., training to use a specific online platform) to meet the specific needs of the training (37). A mixed-methods approach, combining various training components, was evident in some studies to provide a comprehensive learning experience (38). Many training programs involved interactive elements such as group supervision, role-plays, case discussions, and hands-on training to engage participants (34, 37, 39) which were delivered via digital methods including videoconferencing, online platforms, and other digital resources (See Figure 2).

3.7 Quality assessment of TMH E&T

Most evaluations of the effectiveness, feasibility, and impact of TMH training programs were done through surveys. Those included competency-based evaluations (29), feedback (34, 37), programmatic evaluations (28, 33), and sustainability assessments (43). Most assessments focused on using feedback and data to improve training programs, guidelines, and processes (36, 40, 43); however, some assessments, particularly in programmatic evaluations, aimed to provide resource savings in training delivery (42). One study used both quantitative and qualitative data to evaluate the effectiveness of training programs (40).

3.8 Outcomes of TMH E&T

All training programs were found to be effective in achieving their goals, including expanding access to services, improvement of competencies, facilitating global collaboration among international institutions, and facilitating rapid adaptation during time-sensitive public health crises. User satisfaction was a common theme, indicating that participants found the training programs to be helpful, timely, and relevant (34, 36, 38). The results also highlighted the adaptability of these programs in response to challenges, such as the rapid adoption of telepsychology during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the importance of collaboration, outreach, and ongoing support in reaching diverse audiences and expanding the positive impact of TMH training efforts (29).

4 Discussion

The current systematic review of TMH E&T summarized the setting, target group, study aims, training modality, quality of training assessment, and outcomes of studies over the last 10 years.

While present to some degree prior, the study of TMH E&T demonstrated the most notable growth since 2020. While definitive reasons for this finding are unclear, as they were often not directly addressed in each study’s methodology, it is hypothesized that the growing recognition of the importance of TMH E&T arose in response to the exponential increase in clinical usage following the advent of COVID-19 (i.e., providers experienced a rapid and unanticipated transition to telehealth, despite having limited prior training). As a result, providers, training programs, and researchers recognized the gap in both literature and training related to TMH competencies, prompting the increase in study.

4.1 Current field offerings

Analysis suggested that while still in its relative infancy, literature on TMH E&T is developing. Data indicated that trainings have occurred across a wide variety of locations (e.g., university counseling centers, community clinics, hospitals), and for healthcare providers across professional developmental levels (e.g., doctoral level, licensed providers). While professional emphasis varied, the majority of identified literature focused on psychology or social worker students and licensed professionals rather than other healthcare specialties. Related to aims, training programs predominantly focused on developing both knowledge and skill domains, two equally important, but different, components necessary to develop competency in the numerous telehealth competencies (e.g., ethics, legal, adaptations of practice) (45). Such programs included E&T through practicum training and focused continuing education provided in-person, via technology (e.g., web-based courses, live sessions), or a hybrid approach of both. Trainings were broadly concluded as feasible, and yielding positive impact on provider self-perceived knowledge of TMH, as well as allowing for expansion of access to clinical services. Finally, satisfaction of the trainings was generally high among trainees, suggesting the sustainability of the outlined programs either as currently designed, or as adapted/updated for future use.

4.2 Key factors and themes

As based upon primary findings, key factors and themes for the studies can be summarized as follows:

• Supervision and manpower: availability of flexible on-ground supervisors is crucial for effective TMH E&T. This includes ensuring there is adequate support, follow-up, and ongoing assistance for trainees (28, 39).

• Technology quality and reliability: the success of TMH interventions is contingent upon the quality and reliability of the technology used in training. Factors such as audiovisual communication quality and internet signal strength play significant roles (34, 38, 39, 42).

• Cultural and linguistic appropriateness: ensuring interventions are culturally and linguistically appropriate is highlighted as an important factor for successful TMH E&T (28).

• Integration into healthcare systems: successful integration into existing healthcare systems is crucial for the success of TMH interventions. Addressing broader social and political factors affecting mental healthcare is also emphasized (28).

• Addressing barriers: barriers at provider, system, and patient levels, such as lack of familiarity with technology, limited access, concerns about quality, and lack of a supportive, training-oriented environment must be addressed through comprehensive training programs (31, 40).

• Continuous interaction and feedback: constant interaction, ongoing support, and a phased approach to training are essential to ensure effectiveness (34, 39, 42).

• Choice of applications and training approach: factors like the choice of applications, clinician engagement, and the overall training approach significantly impact the effectiveness of TMH E&T (38, 43).

• Evaluation methodology: the use of frameworks like PARiHS and RE-AIM for evaluation is emphasized, underlining the importance of robust evaluation methodologies (38, 43).

• These factors collectively stress the need for a comprehensive, context-specific, and culturally sensitive approach to ensure the effectiveness of TMH E&T programs.

4.3 Limitations of the literature and areas for future TMH E&T growth

Reviewed studies collectively had limitations that may affect their generalizability. First, a majority of studies were case examples of local/regional training programs. While serving as a template for other locations, direct application may not be possible to other settings/locations without adaptation. Similarly, most existing studies were based on small sample sizes and specific target groups, and therefore limit the generalizability of the findings. Larger-scale research in more diverse settings is needed to confirm the generalizability of the results. Additionally, many studies relied on one-time self-reported surveys as opposed to more objective data collection of specific operationally-defined targets, such as changes in attitude towards TMH, usage of TMH, how providers adapted (or did not adapt) practices following TMH E&T, locations served via TMH, and long-term use of TMH. Objective evaluation is believed necessary, as just because a provider gains new knowledge and skills does not necessarily mean that they will integrate such information into their practice in the immediate or long-term, especially if barriers present (e.g., lack of time, financial challenges). As a result, external validation of assessments currently utilized, as well as longitudinal data collection are required (30). Related to the training itself, there remains a lack of uniformity in terms of how the information is presented (e.g., length, methodology) (27). More concerning, many studies failed to define what was actually being taught in terms of TMH modality (e.g., video vs. email) or competencies. Finally, a wider range of provider demographic characteristics is needed to determine the influence of location (i.e., rural, urban), race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, treated population, and technology modalities (e.g., video, telephone, email) on training outcomes. Towards this end, additional evaluation should evaluate provider current practices, and directly inquire about what is most needed to tailor the E&T to unique populations of providers (e.g., underserved or remote areas).

While collective results are promising, findings highlight the need for additional and targeted study on TMH E&T in terms of defining necessary competencies for providers, greater diversity of study location and demographic considerations, and long-term follow-up to clarify provider ongoing use and outreach activities (e.g., whether TMH E&T fostered a desire for additional outreach efforts than what the provider offered prior to the training). Future studies should seek to remedy noted limitations.

4.4 Application of findings

With consideration of both strengths and areas of improvement of current literature, several recommendations for future application of E&T are presented. Most importantly, field experts, training programs, and guiding organizations must work to consolidate literature to identify essential and universal TMH competencies, both knowledge- and skill-based. Additionally, optimal means of conveying such information (e.g., in-person training, web-based self-guided, hybrid approach) is necessary. As part of this training (or following), supervision of TMH usage is vital (46). Supervision of TMH allows for the trainee to receive targeted feedback of both strengths and areas for improvement, allows for advancement of knowledge and skills, and gatekeeps the profession. To track trainee progress, evaluate training program efficacy and effectiveness, and allow for iterative development of the programs, comprehensive and consistent objective outcome measures are required. Utilization of similar measures across studies will allow for cross-site comparison. Targets of evaluation can include satisfaction, as well as the program’s ability to foster greater TMH knowledge, greater TMH skills, and outreach efforts to rural and underserved communities. Additionally, evaluation should consider cost effectiveness of the programs to optimize both training methodologies and costs to create sustainable and scalable programs that can provide a template for TMH education, while allowing the ability to tailor to different regions, states, provinces, territories, or countries to accommodate different languages, cultures, and contexts. Of important note, E&T is not a one-time endeavor. Similar to other aspects of healthcare, continuing education is a lifelong activity. As such, E&T efforts should be designed around different professional developmental stages. More specifically, E&T should be created and adopted by graduate-level training programs to provide novice providers with education and supervision of TMH practices. Such practices can be augmented and supplemented by additional E&T on internships, fellowships, and residencies. Finally, continuing education activities and programs should be tailored to those more senior providers who already have experiences with TMH, but require updates to ensure adherence to ever-changing evidence-based standards and regulations surrounding the use of technology in healthcare services. To formalize training activities, policy makers (e.g., American Psychological Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Medical Association) who guide and/or accredit healthcare training programs, and license regulators (e.g., state licensing boards) should encourage consistent TMH accreditation standards for training and continuing education requirements for maintenance of licensure.

4.5 Limitations of the current study

While the current study is believed to address an identified gap in the literature, it is not without limitations that should be considered in the finding’s interpretation. First, the study pulled from five databases. While broad databases were chosen, it is recognized that additional relevant literature may be available in other databases. Similarly, only peer-reviewed manuscripts were considered for inclusion, potentially excluding relevant literature that has yet to be published, or included in non-peer-reviewed outlets (e.g., books). In addition, this review focused on TMH E&T broadly and did not include discussion of other technologies such as AI, a rapidly emerging technology revolutionizing today’s health care. Further, the study aimed to qualitatively describe current field offerings and guide future directions. Nevertheless, it is recognized that future work should consider quantitively defining and analyzing data to further understand current strengths and limitations. Such future study should also seek to address identified field limitations, such as small sample sizes, limited external validity, poor standardization of competencies across studies, and different methodologies that each create challenges for direct comparison.

5 Conclusion

Telemental health has rapidly expanded in recent years, subsequently producing a myriad of different training programs, each with unique strengths and limitations. While meaningful progress has been made related to TMH E&T, additional work is required. As the use of TMH is projected to continue (47), it remains prudent for E&T programs to work towards standardization of training foci and methodologies in line with evidence-based literature and developing literature and policies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

QJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research was supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences Planning Fund Project of the Ministry of Education (22YJA710010), and the Philosophy and Social Science Fund Project of Hunan Province (21JD051), China.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all study participants for their contributions. We thank the editor and reviewers who provided valuable and constructive comments that significantly improved this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1385532/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Shaver, J. The state of telehealth before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Prim Care. (2022) 49:517–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2022.04.002

2. Perle, JG. A mental health provider’s guide to telehealth: providing outpatient videoconferencing services Routledge (2021).

3. Hilty, DM, Ferrer, DC, Parish, MB, Johnston, B, Callahan, EJ, and Yellowlees, PM. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemedicine e-Health. (2013) 19:444–54. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0075

4. Gordon, RM, Wang, X, and Tune, J. Comparing psychodynamic teaching, supervision, and psychotherapy over videoconferencing technology with Chinese students. Psychodyn Psychiatry. (2015) 43:585–99. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2015.43.4.585

5. Jesser, A, Muckenhuber, J, and Lunglmayr, B. Psychodynamic Therapist’s subjective experiences with remote psychotherapy during the COVID-19-pandemic-a qualitative study with therapists practicing guided affective imagery, hypnosis and autogenous relaxation. Front Psychol. (2022) 12:777102. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.777102

6. Mohamadzadeh Tabrizi, Z, Mohammadzadeh, F, Davarinia Motlagh Quchan, A, and Bahri, N. COVID-19 anxiety and quality of life among Iranian nurses. BMC Nurs. (2022) 21:27. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00800-2

7. Shreck, E, Nehrig, N, Schneider, JA, Palfrey, A, Buckley, J, Jordan, B, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing a US Department of veterans affairs telemental health (TMH) program for rural veterans. J Rural Ment Health. (2020) 44:1–15. doi: 10.1037/rmh0000129

8. Chen, CK, Palfrey, A, Shreck, E, Silvestri, B, Wash, L, Nehrig, N, et al. Implementation of Telemental health (TMH) psychological services for rural veterans at the VA New York Harbor healthcare system. Psychol Serv. (2021) 18:1–10. doi: 10.1037/ser0000323

9. Lipschitz, JM, Connolly, SL, Van Boxtel, R, Potter, JR, Nixon, N, and Bidargaddi, N. Provider perspectives on telemental health implementation: lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic and paths forward. Psychol Services. (2022) 20:11. doi: 10.1037/ser0000625

10. Disney, L, Mowbray, O, and Evans, D. Telemental health use and refugee mental health providers following COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Soc Work J. (2021) 49:463–70. doi: 10.1007/s10615-021-00808-w

11. Robertson, EL, Piscitello, J, Schmidt, E, Mallar, C, Davidson, B, and Natale, R. Longitudinal transactional relationships between caregiver and child mental health during the COVID-19 global pandemic. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. (2021) 15:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13034-021-00422-1

12. Perle, JG. Mental health providers’ telehealth education prior to and following implementation: a COVID-19 rapid response survey. Prof Psychol Res Pract. (2022) 53:143–50. doi: 10.1037/pro0000450

13. Abel, EA, Glover, J, Brandt, CA, and Godleski, L. Recommendations for the reporting of Telemental health (TMH) literature based on a systematic review of clinical video teleconferencing (CVT) and depression. J Technol Behav Sci. (2017) 2:28–40. doi: 10.1007/s41347-016-0003-1

14. Baird, MB, Whitney, L, and Caedo, CE. Experiences and attitudes among psychiatric mental health advanced practice nurses in the use of telemental health: results of an online survey. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. (2018) 24:235–40. doi: 10.1177/1078390317717330

15. Drude, KP, Hertlien, KM, Maheu, MM, Hilty, DM, and Wall, K. Telebehavioral health competencies in interprofessional education and training: a pathway to interprofessional practice. J. technol. behav. sci. (2020) 5:30–9. doi: 10.1007/s41347-019-00112-y

16. Maheu, MM, Wright, SD, Neufeld, J, Drude, KP, Hilty, DM, Baker, DC, et al. Interprofessional telebehavioral health competencies framework: implications for telepsychology. Prof Psychol Res Pract. (2021) 52:439–48. doi: 10.1037/pro0000400

17. Merrill, CA, Maheu, MM, Drude, KP, Groshong, LW, Coleman, M, and Hilty, DM. CTiBS and clinical social work: telebehavioral health competencies for LCSWs in the age of COVID-19. Clin Soc Work J. (2022) 50:115–23. doi: 10.1007/s10615-021-00827-7

18. Hilty, DM, Crawford, A, Teshima, J, Chan, S, Sunderji, N, Yellowlees, PM, et al. A framework for telepsychiatric training and e-health: competency-based education, evaluation and implications. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2015) 27:569–92. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1091292

19. Perle, JG, Burt, J, and Higgins, WJ. Psychologist and physician interest in telehealth training and referral for mental health services: an exploratory study. J Technol Hum Serv. (2014) 32:158–85. doi: 10.1080/15228835.2014.894488

20. Perle, JG, Perle, AR, Scarisbrick, DM, and Mahoney, JJ III. Fostering telecompetence: a descriptive evaluation of clinical psychology predoctoral internship and postdoctoral fellowship implementation of telehealth education. J Rural Health. (2023) 39:444–51. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12709

21. Perle, JG, Perle, AR, Scarisbrick, DM, and Mahoney, JJ. Educating for the future: a preliminary investigation of doctoral-level clinical psychology training program’s implementation of telehealth education. J Technol Behav Sci. (2022) 7:351–7. doi: 10.1007/s41347-022-00255-5

22. Crawford, A, Gratzer, D, Jovanovic, M, Rodie, D, Sockalingam, S, Sunderji, N, et al. Building eHealth and telepsychiatry capabilities: three educational reports across the learning continuum. Acad Psychiatry. (2018) 42:852–6. doi: 10.1007/s40596-018-0989-0

23. Khan, S, and Ramtekkar, U. Child and adolescent telepsychiatry education and training. Psychiatr Clin. (2019) 42:555–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2019.08.010

24. Mohammadzadeh, Z, Maserat, E, and Davoodi, S. Role of telemental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: an early review. Ir J Psychiatr Behav Sci. (2022) 16:116597. doi: 10.5812/ijpbs.116597

25. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol. (2021) 134:103–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003

26. Mishkind, MC, Boyd, A, Kramer, GM, Ayers, T, and Miller, PA. Evaluating the benefits of a live, simulation-based telebehavioral health training for a deploying army reserve unit. Mil Med. (2013) 178:1322–7. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00278

27. McCord, CE, Saenz, JJ, Armstrong, TW, and Elliott, TR. Training the next generation of counseling psychologists in the practice of telepsychology. Couns Psychol Q. (2015) 28:324–44. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2015.1053433

28. Jefee-Bahloul, H, Barkil-Oteo, A, Shukair, N, Alraas, W, and Mahasneh, W. Using a store-and-forward system to provide global telemental health supervision and training: a case from Syria. Acad Psychiatry. (2016) 40:707–9. doi: 10.1007/s40596-015-0423-9

29. Alicata, D, Schroepfer, A, Unten, T, Agoha, R, Helm, S, Fukuda, M, et al. Telemental health training, team building, and workforce development in cultural context: the Hawaii experience. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. (2016) 26:260–5. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0036

30. Thew, GR, Powell, CL, Kwok, AP, Chan, MHL, Wild, J, Warnock-Parkes, E, et al. Internet-based cognitive therapy for social anxiety disorder in Hong Kong: therapist training and dissemination case series. JMIR Form Res. (2019) 3:e13446. doi: 10.2196/13446

31. Caver, KA, Shearer, EM, Burks, DJ, Perry, K, De Paul, NF, McGinn, MM, et al. Telemental health training in the veterans administration puget sound health care system. J Clin Psychol. (2020) 76:1108–24. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22797

32. Perrin, PB, Rybarczyk, BD, Pierce, BS, Jones, HA, Shaffer, C, and Islam, L. Rapid telepsychology deployment during the COVID-19 pandemic: a special issue commentary and lessons from primary care psychology training. J Clin Psychol. (2020) 76:1173–85. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22969

33. Wilkerson, DA, Wolfe-Taylor, SN, Deck, CK, Wahler, EA, and Davis, TS. Telebehavioral practice basics for social worker educators and clinicians responding to COVID-19. Soc Work Educ. (2020) 39:1137–45. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2020.1807926

34. Malhotra, S, Chakrabarti, S, Gupta, A, Sharma, K, and Sharma, M. Training nonspecialists in clinical evaluation for telepsychiatry using videoconferencing: a feasibility and effectiveness study. Indian J Psychiatry. (2021) 63:462–6. doi: 10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_336_21

35. Kroll, K, Brosig, C, Malkoff, A, and Bice-Urbach, B. Evaluation of a systems-wide Telebehavioral health training implementation in response to COVID-19. J Patient Exp. (2021) 8:237437352199773. doi: 10.1177/2374373521997739

36. Olson, JR, Lucy, M, Kellogg, MA, Schmitz, K, Berntson, T, Stuber, J, et al. What happens when training Goes virtual? Adapting training and technical assistance for the school mental health workforce in response to COVID-19. Sch Ment Heal. (2021) 13:160–73. doi: 10.1007/s12310-020-09401-x

37. Parish, MB, Gonzalez, A, Hilty, D, Chan, S, Xiong, G, Scher, L, et al. Asynchronous telepsychiatry interviewer training recommendations: a model for interdisciplinary, integrated behavioral health care. Telemedicine and e-Health. (2021) 27:982–8. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0076

38. Felker, B. L., McGinn, M. M., Shearer, E. M., Raza, G. T., Gold, S. D., Kim, J. M., et al., (2021). Implementation of a telemental health training program across a mental health department

39. McCord, CE, Console, K, Jackson, K, Palmiere, D, Stickley, M, Williamson, MLC, et al. Telepsychology training in a public health crisis: a case example. Couns Psychol Q. (2021) 34:608–23. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2020.1782842

40. Dopp, AR, Mapes, AR, Wolkowicz, NR, McCord, CE, and Feldner, MT. Incorporating telehealth into health service psychology training: a mixed-method study of student perspectives. Digital Health. (2021) 7:205520762098022. doi: 10.1177/2055207620980222

41. Atuel, HR, and Kintzle, S. Comparing the training effectiveness of virtual reality and role play among future mental health providers. Psychol Trauma. (2021) 13:657–64. doi: 10.1037/tra0000997

42. Buck, B, Kopelovich, SL, Tauscher, JS, Chwastiak, L, and Ben-Zeev, D. Developing the workforce of the digital future: leveraging technology to train community-based Mobile mental health specialists. J Technol Behav Sci. (2023) 8:209–15. doi: 10.1007/s41347-022-00270-6

43. Felker, BL, Towle, CB, Wick, IK, and McKee, M. Designing and implementing TeleBehavioral health training to support rapid and enduring transition to virtual care in the COVID era. J Technol Behav Sci. (2023) 8:225–33. doi: 10.1007/s41347-022-00286-y

44. Tyagi, V, Khan, A, Siddiqui, S, Kakra Abhilashi, M, Dhurve, P, Tugnawat, D, et al. Development of a digital program for training community health workers in the detection and referral of schizophrenia in rural India. Psychiatry Q. (2023) 94:141–63. doi: 10.1007/s11126-023-10019-w

45. Perle, JG. Training psychology students for telehealth: a model for doctoral-level education. J Technol Behav Sci. (2021) 6:456–9. doi: 10.1007/s41347-021-00212-8

46. Perle, JG, and Zheng, W. A primer for understanding and utilizing telesupervision with healthcare trainees. J Technol Behav Sci. (2023) 9:46–52. doi: 10.1007/s41347-023-00322-5

Keywords: telemental health (TMH), education and training, competency development, telepsychology, telepsychiatry, telebehavioral health (TBH)

Citation: Jiang Q, Deng Y, Perle J, Zheng W, Chandran D, Chen J and Liu F (2024) Education and training of telemental health providers: a systematic review. Front. Public Health. 12:1385532. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1385532

Edited by:

Julian Schwarz, Brandenburg Medical School Theodor Fontane, GermanyReviewed by:

Eva Meier-Diedrich, Medizinische Universität Brandenburg Theodor Fontane, GermanyMaría Soledad Burrone, Universidad de O’Higgins, Chile

Copyright © 2024 Jiang, Deng, Perle, Zheng, Chandran, Chen and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiaoling Jiang, NTY1NDgzOTM2QHFxLmNvbQ==; Yongjia Deng, eWQwMDAyQG1peC53dnUuZWR1

Qiaoling Jiang

Qiaoling Jiang Yongjia Deng

Yongjia Deng Jonathan Perle3

Jonathan Perle3 Wanhong Zheng

Wanhong Zheng