94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health, 31 July 2024

Sec. Aging and Public Health

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1377869

Introduction: Older adults commonly face the risk of social isolation, which poses a significant threat to their quality of life. This study explores the association between social participation and life satisfaction among older Chinese adults.

Methods: Data were sourced from the 2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Regression analysis and mediation analysis were employed to examine the relationship between social participation and life satisfaction, with a focus on the roles of loneliness and self-rated health.

Results: The results indicate that social participation is significantly positively associated with older adults' life satisfaction. Furthermore, the positive association is more pronounced with increased diversity in social activities. Mediation analysis reveals that reductions in feelings of loneliness and improvements in health levels mediate the relationship between social participation and life satisfaction. Further analysis showed that social participation had a greater positive association among rural older adults and those lacking family companionship.

Discussion: This study provides evidence for enhancing life satisfaction among older adults and highlights the importance of diversity in social participation.

Population aging is a basic national condition faced by major economies (1). China became an aged society in 2022 and is currently one of the countries experiencing high population aging rates. Data from the National Bureau of Statistics show that, by the end of 2022, the population aged 60 years and above reached approximately 280 million, making up 19.8% of the total population. Such a large older adult population will have a far-reaching impact on various aspects of society and the economy, and corresponding policies must be formulated to cope with the impact of aging (2). It is important to enhance the quality of life of older adults, provide them with better access to services, and enable them to enjoy their golden years peacefully. Life satisfaction is a comprehensive evaluation of an individual's overall life and is a key indicator of mental health and life quality (3), which is a significant reflection of societal progress and development (4). In this context, this study aimed to explore how to improve the life satisfaction of the older adults.

In recent years, an increasing number of scholars have analyzed the influencing factors of the life satisfaction and explored the differences in life satisfaction among different groups (5, 6). Early studies concluded that individuals with high life satisfaction are typically young, well-educated, optimistic, high-income, married, and reside in favorable community environments (6–9). Additionally, studies have examined the impact of social participation on older adults' quality of life and have highlighted the importance of effective social activities in enhancing life quality among the older adults (10). Informal activities such as physical activity and community interactions have been emphasized in studies that investigate enhanced life satisfaction in older adults (10–13), whereas formal activities such as volunteering and club activities are important for older adults' perceptions of self-worth and can enhance their subjective life satisfaction (14, 15). For instance, a Spanish community-based longitudinal survey found that physical activity positively impacted the life satisfaction of older adults (16). Existing literature widely acknowledges that social participation is crucial for older adults to adapt to the changes that occur with aging and to actively embrace the aging process (17, 18). Countries worldwide have implemented various measures, such as the “China 14th Five-Year Plan for Healthy Aging,” which emphasizes promoting healthy aging in China by encouraging older adults to adopt healthy lifestyles and improve their health and quality of life (19). Despite these efforts, the relationship between social participation and life satisfaction among older adults in China remains underexplored. Therefore, we propose hypothesis H1: Social participation can positively predict the life satisfaction of older adults.

Social participation also plays a role in reducing loneliness and improving health among older adults. The lack of social interaction can lead to social isolation and increased loneliness, negatively affecting life satisfaction (20–22). Engaging in community activities and maintaining social networks can reduce feelings of loneliness and enhance emotional wellbeing (10, 23, 24). Older adults can reduce feelings of loneliness and enhance their life satisfaction by participating in various forms of social interactions, which can help them understand and realize their values from the spiritual perspective of self-actualization (17). Additionally, social participation is linked to better health outcomes, including reduced depression, improved physical status, and lower mortality rates (25–30). Existing studies also suggest that both physical and psychological health contribute to life satisfaction among older adults (31, 32). Such findings highlight the importance of social participation in maintaining both mental and physical health, as it contributes to overall life satisfaction. We propose the research hypotheses H2: Health and loneliness play mediators in the relationship between social participation and life satisfaction among Chinese older adults.

Existing literature acknowledges the differences among various groups of older adults, particularly in terms of urban-rural disparities and variations in family support. There exists conspicuous inequality between urban and rural areas in China, resulting in unfairness between urban and rural residents (33). Urban older adults have more frequent contact with their offspring, easier access to information, and stronger social connections (34–36). Conversely, rural areas suffer from scarce support resources, exacerbating the disparity in health-related living conditions between rural and urban older adults individuals (5, 37–39). It is generally believed that rural older adults individuals experience poorer life quality, while emphasizing the positive impact of social participation on rural older adults individuals (40, 41). Research indicates that rural populations may experience a greater influence from social participation due to their potentially greater need to compensate for emotional deficits through social interaction (42, 43). Social participation also contributes to the life satisfaction of older adults lacking family support (44). Studies indicate that older adults living alone, without family companionship, experience lower life satisfaction and poorer health (45, 46). Widowed individuals may have lower life satisfaction due to the absence of spousal support (47). Intergenerational interactions also influence life satisfaction, with less interaction with younger generations associated with lower satisfaction (48, 49). Therefore, individuals lacking family support rely more on social resources for psychological adjustment and require more social support compared to those with frequent family contact (50). So, we introduce the following research hypotheses H3: H3a: Social participation correlates more strongly with life satisfaction for rural older adults compared to urban older adults. H3b: Social participation correlates more strongly with life satisfaction for older adults lacking family companionship compared to those with family support.

Building upon the aforementioned research hypotheses, this study utilized data from the 2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS2018) to investigate the association between social participation and life satisfaction among older adults. Specifically, we focused on two main aspects: first, we explored the relationship between older adults' social participation and their life satisfaction, including potential mediating factors; second, we investigated the variability of social engagement effects across different regions and family contexts among older adults. Through the study of these issues, we hoped to gain insight into the relationship between healthy lifestyles and the quality of life of older adults and explore the characteristics of older adults in terms of emotional and social needs, in order to provide a perspective on experiences and insights which may inform the future design of older adults' services and policies.

The data used in this study were obtained from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), which covers approximately 10,000 households and 17,000 individuals in 150 county- and 450 village-level units. CHARLS aimed to collect and analyze high-quality microdata from middle-aged and older adults aged 45 years and older, representing the aging population of China. This study used the cross-sectional data, released in 2018, focusing on individuals aged 60 years and older, to examine the impact of social participation on their life satisfaction. There were 15,941 valid samples in the original data for 2018. The data processing steps in this study are as follows: First, we combined household and individual databases. Second, to retain the sample of our research subjects, we excluded individuals under 60 years old (7,600). Finally, we removed samples with missing primary variables (229), resulting in 8,112 observations being included in the analysis.

The dependent variable in this article was the life satisfaction of older adults, which was measured using a questionnaire that asked respondents, “How satisfied are you with your life?” with possible responses of “extremely satisfied, very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, not satisfied, not at all satisfied.” In this study, these five responses were assigned values of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively, and the resulting average value was 2.7.

The core independent variable was social participation. A questionnaire was used to ask the respondents if they had engaged in the following 11 social activities in the past month: “visiting friends,” “playing mahjong, chess, or cards, going to the community activity room,” “providing help to relatives, friends or neighbors who do not live with you,” “dancing, exercising, practicing qigong, etc.,” “participating in club activities,” “volunteering or charity work,” “caring for patients or disabled people who do not live with you,” “going to school or attending training courses,” “stock trading (funds and other financial securities),” “using the internet,” and “other social activities.” The 11 options were summarized to measure the older adults' social participation. We examined the richness of social activity participation because it firstly reflects whether individuals actively engage in social activities and secondly represents the extent of social activity involvement. This variable better reflects individuals' social habits. We also considered a dummy variable indicating whether individuals engage in social activities. The purpose of this approach is to allow readers to more intuitively understand the difference in life satisfaction between those who participate in social activities and those who do not, which is a common practice in the literature (51, 52).

To control for other factors affecting older adults' life satisfaction, based on an analysis of the literature (6), the study controls for three levels of variables that affect older adults' life satisfaction: individual, family, and social.

At the individual level, we controlled for personal characteristics such as sex, age, education level, religious beliefs, insurance status, employment status, and personal health. At the household level, we controlled for household consumption, residential area, number of household members, whether address has changed, and whether there was a partner. At the social level, we used fixed effects at the community level, such as infrastructure and community services, to control for the effects of inherent community-level characteristics on older adults' satisfaction.

The mediation analysis was based on two variables: self-rated health and loneliness. Self-rated health is an ordinal variable of decreasing magnitude, with values from 1 to 5 indicating very healthy, healthy, fair, unhealthy, and very unhealthy individuals, respectively. Self-rated health is widely utilized in the literature and can to some extent reflect individuals' health status (32, 53). Loneliness is an ordinal variable of increasing magnitude, measured by asking how often participants felt lonely in the last week, with values from 1 to 4 being “ < 1,” “1–2,” “3–4,” and “5–7 days.”

We performed statistical analysis using Stata17. Based on the characteristics of the main research variables, this study used ordered probit (Oprobit) regression as the main regression to analyze the data. We conducted mediation analysis using stepwise regression and heterogeneity analysis using grouped regression. We have also employed OLS regression for the main analysis included the results in Supplementary Table 1. To verify the robustness of the analysis, we conducted a propensity score matching (PSM) analysis, with the results reported in Supplementary material A. Oprobit regression is widely used in the literature to deal with cases in which the explanatory variables are ordered, and based on the characteristics of the explanatory variables here, the model was set as follows:

In Equations (1, 2), the is the latent variable of the dependent variable “life satisfaction,” which is unobservable, and Yi is a non-linear function. The relationship between them is as follows: when is lower than the threshold value μ1 the older person is extremely satisfied with life (Yi = 1); when is higher than μ1 but < μ2 then the older person is very satisfied with life (Yi = 2). When is higher than μ4 the older person is very dissatisfied with life (Yi = 5). In Equation (1), Si is the independent variable “social participation,” Xi includes all control variables at the individual level and household level, and εi is the random disturbance term. Assuming that εi follows a normal distribution across different observations, its mean and variance are standardized to 0 and 1. Z denotes all the explanatory variables, and the probability of Yi can be obtained as shown in Equation (3).

All variables are presented in Table 1. The sample consists of slightly more males (51.5%) than females (48.5%). Most individuals are aged between 60 and 70 years. A larger proportion of older adults reside in rural areas (58.8%) compared to urban areas (41.2%). Regarding family connections, 18.5% of older adults do not have a partner, and 57.4% are not involved in caring for grandchildren. The number of older adults participating in social activities (50.7%) is comparable to those not participating (49.3%). Figure 1 illustrates that older adults who engage in social activities report lower scores and higher life satisfaction than those who do not.

Table 2 presents the results of the hierarchical Oprobit regression models that investigated the relationship of social activity participation and life satisfaction in older adults. In column (1–3), they respectively include individual-level control variables, individual and household-level control variables. The regression coefficients continue to show significant negative associations, while the R-squared value gradually increases (β = −0.0339, P < 0.01; β = −0.0472, P < 0.01; β = −0.0474, P < 0.01). This suggests that participating in social activities effectively associated the life satisfaction of older adults, and this positive association becomes more pronounced with greater richness of participation. In column (4–6), the measurement of the dependent variable was changed to whether they engage in social activities, and the correlation still exists (β = −0.0396, P < 0.05; β = −0.0590, P < 0.05;β = −0.0603, P < 0.05), demonstrating the robustness of the results. Furthermore, Table 2 also sheds light on other factors predicting older adults' life satisfaction, Age (β = −0.0186, P < 0.01), education (β = −0.0286, P < 0.01), work status (β = −0.138, P < 0.01), basic disease (β = 0.0785, P < 0.01), place of residence (β = 0.743, P < 0.01), and companionship (β = −0.114, P < 0.01). The results of the VIF analysis for each variable in the analytical model are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

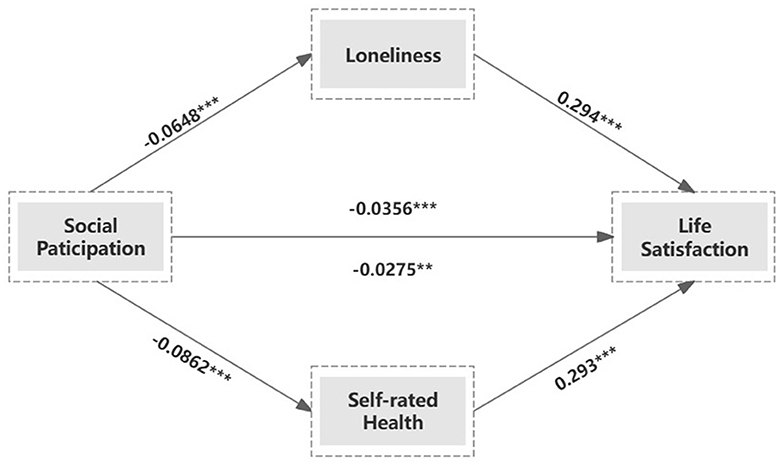

The results of the mediation analyses are reported in Table 3. Based on the estimates presented in Table 3 (1–2), social participation predicted lower levels of loneliness among older adults (β = −0.0648, P < 0.01) and there was a significant positive relationship between social participation and life satisfaction (β = 0.294, P < 0.01). The statistical results shown in Table 3 (3–4) indicate that engaging in social activities enhances self-rated health (β = −0.0862, P < 0.01), and self-rated health is significantly positively correlated with life satisfaction (β = 0.293, P < 0.01). In both mediation analyses, the absolute value of the correlation coefficients between social participation and life satisfaction (β = −0.0356, P < 0.01; β = −0.0275, P < 0.05) were smaller than the direct correlation coefficient between social participation and life satisfaction (β = 0.0474, P < 0.01). The results of the mediation analysis are visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Path diagram of association between social participation and life satisfaction. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

The results, shown in Table 4 (1–2), indicate that there are differences in the positive correlation of social participation with the life satisfaction of rural and urban older adults. The absolute value of correlation coefficient with life satisfaction for rural older adults (β = −0.0603, P < 0.01) is greater than that for urban older adults (β = −0.0358, P < 0.05). The second examination of heterogeneity explored the association between social participation and life satisfaction among older adults with different levels of emotional support from their families. The findings reported in Table 4 (3–6) suggest a significant correlation between social participation and the life satisfaction of older adults without partners (β = −0.086, P < 0.05). In contrast, the relationship between social participation and the life satisfaction of older adults with partners appears to be weaker (β = −0.0356, P < 0.05). Among those not providing care for grandchildren, the coefficient of social engagement on life satisfaction was −0.0713, significant at the 1% level. However, for older adults providing care for grandchildren, the coefficient was only −0.034, significant at the 10% level.

Older adults are a vulnerable group in society, and their population will continue to increase for a long time in the future. Improving the life satisfaction of older adults is an inherent requirement and a key point in the development of a global health strategy, and it is of great significance to promote healthy aging.

The study found a significant positive association between participation in social activities and the life satisfaction of older adults. Additionally, the richness of participation in different types of social activities correlates with greater life satisfaction. This finding consistent with Hypothesis H1 and empirically contributes to the research on the relationship between social activities and life satisfaction (6).

The mediation analysis in our study showed that loneliness and self-rated health partially mediate the relationship between social participation and life satisfaction, with participation in social activities significantly associated with life satisfaction by reducing loneliness and improving self-rated health. We believe that different social activities contribute differently to the older adult population. For example, participating in community activities helps maintain neighborhood relationships among the older adults (9), while volunteering and interest activities broaden their social networks (15, 54), all of which can reduce loneliness and improve mental health. Physical exercise helps older adults improve their physical health (55). The health level of older adults is closely related to their life satisfaction, and good health can bring more life opportunities, a higher quality of life, and higher satisfaction to older adults (56). Both health and loneliness of older adults have been studied as important factors affecting their quality of life (57, 58), which was also verified in the analysis. Our findings support Hypothesis H2 that health and loneliness mediate the relationship between social participation and life satisfaction. This underscores the importance of encouraging active social engagement among older adults and provides useful references for policies on healthy aging, emphasizing social participation's role in alleviating loneliness and promoting health and life satisfaction.

Our study also provides extensive information on heterogeneity. First, social participation has a greater impact on rural older adults than on urban older adults. This may be due to the relative lack of leisure and entertainment facilities in rural areas compared with cities, and the higher quality of life expectations among older adults in urban areas (59). Simultaneously, it is easier and more convenient for urban older adults to meet their children (60). With the outflow of young and middle-aged people from rural areas in China, the number of empty-nest older adults in rural areas is increasing, making it difficult for them to obtain their sense of life satisfaction from their families (45). Older adults in rural areas are mostly left behind and have fewer face-to-face interactions with their children (37). Therefore, they are more inclined to seek emotional support through external social activities to enhance their life satisfaction. This result supports Hypothesis H3a.

Second, participation in social activities has a greater association with older adults who lack family companionship, suggesting that social participation may partially offset the absence of family companionship. On one hand, there is a marginal diminishing effect on the improvement of life satisfaction (61), and older adults with sufficient family companionship may have higher life satisfaction (60). On the other hand, the older adults lacking companionship are more likely to seek emotional support from outside (62), so subjective life satisfaction is more influenced by social activities. This further supports Hypothesis H3b, highlighting the need for more attention to be paid to vulnerable older adult populations with emotional deficits, thus aiding them in enjoying their later years.

This study argued that advocating for older adults to participate in social activities and enhance their sense of social inclusion is a key measure for further enhancing their life satisfaction and promoting healthy aging. Therefore, this paper puts forward the following recommendations: first, promote the development of public, cultural, and sports undertakings; improve and enrich relevant services at the community level, such as increasing sports equipment and providing activity venues for older adults; and second, encourage older adults to participate in social activities, such as community volunteer and interest activities, thus reducing the opportunity cost of their social participation. Finally, attention should be paid to older adults in rural areas and those who lack family companionship because their participation in social activities has a significant impact on their quality of life and should be encouraged. In summary, increasing opportunities and choices for older adults to participate in social activities is an important measure for creating an age-friendly society and is of great significance to the development of healthy aging.

First, despite the use of multiple methods to enhance the reliability of the results, this was a cross-sectional study owing to data limitations. The panel data allowed us to explore the dynamic changes after participating in social activities. Subsequent research employing panel data will bolster the robustness and reliability of causal inferences. Second, the data for this study were from China; however, the practical situation varies between countries, the utilization of data from diverse countries could enhance the generalizability of this study. Third, the measurement of life satisfaction is self-reported and may be influenced by factors such as social expectations. The adoption of a more objective measurement indicator, if feasible, would be advantageous.

This study showed that social participation can help older adults reduce their loneliness and improve their self-reported health, thereby improving their life satisfaction. Among all the older adults study participants, those who were lacking family companionship and residing in rural areas showed a stronger association between their life satisfaction and social participation. This study helps us understand the important link between social participation and the older adults' life satisfaction. Future research should continue to discuss the factors that influence the quality of life of older people and make efforts to help them enjoy their golden years.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The data underlying the results presented in this study are available from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), and more information on data requests can be found on the CHARLS website: http://charls.pku.edu.cn/.

MW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. DY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. YT: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Soft Science Project of the Sichuan Province Science and Technology Plan in 2023 (grant no. 2023JDR0265) and 2022 Chengdu Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (grant no. 2022BS132).

We would like to extend special thanks to the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), project implemented by the Institute of Social Science Survey (ISSS) at Peking University. The rich dataset from CHARLS has laid a profound foundation for our research, enabling us to comprehensively understand and analyze various issues in the field of social science.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1377869/full#supplementary-material

1. WHO. Ageing and Health. (2023). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed June 8, 2024).

2. Chen X, Giles J, Yao Y, Yip W, Meng Q, Berkman L, et al. The path to healthy ageing in China: a Peking University-Lancet Commission. Lancet. (2022) 400:1967–2006. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01546-X

3. Diener E, Inglehart R, Tay L. Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Soc Indic Res. (2013) 112:497–527. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0076-y

4. Bonini AN. Cross-national variation in individual life satisfaction: effects of national wealth, human development, and environmental conditions. Soc Indic Res. (2008) 87:223–36. doi: 10.1007/s11205-007-9167-6

5. Chen Y, Yang C, Feng S. The effect of social communication on life satisfaction among the rural elderly: a moderated mediation model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:E3791. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16203791

6. Khodabakhsh S. Factors affecting life satisfaction of older adults in Asia: a systematic review. J Happiness Stud. (2022) 23:1289–304. doi: 10.1007/s10902-021-00433-x

7. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Personal Assess. (2010) 49:71–5. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

8. Markides KS, Martin HW. A causal model of life satisfaction among the elderly. J Gerontol. (1979) 34:86–93. doi: 10.1093/geronj/34.1.86

9. Lu P, Shelley M, Kong D. Unmet community service needs and life satisfaction among chinese older adults: a longitudinal study. Soc Work Public Health. (2021) 36:665–76. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2021.1948942

10. Baeriswyl M, Oris M. Social participation and life satisfaction among older adults: diversity of practices and social inequality in Switzerland. Ageing Soc. (2021) 2021:1–25. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X21001057

11. Huxhold O, Miche M, Schüz B. Benefits of having friends in older ages: differential effects of informal social activities on well-being in middle-aged and older adults. J Gerontol Ser B. (2014) 69:366–75. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt029

12. Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. (2009) 50:31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103

13. Jacobs JM, Rottenberg Y, Cohen A, Stessman J. Physical activity and health service utilization among older people. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2013) 14:125–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.023

14. Onyx J, Warburton J. Volunteering and health among older people: a review. Austral J Ageing. (2003) 22:65–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2003.tb00468.x

15. Barron JS, Tan EJ, Yu Q, Song M, McGill S, Fried LP. Potential for intensive volunteering to promote the health of older adults in fair health. J Urban Health. (2009) 86:641–53. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9353-8

16. Balboa-Castillo T, León-Muñoz LM, Graciani A, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, Guallar-Castillón P. Longitudinal association of physical activity and sedentary behavior during leisure time with health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2011) 9:47. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-47

17. Ballantyne A, Trenwith L, Zubrinich S, Corlis M. “I feel less lonely”: what older people say about participating in a social networking website. Qual Ageing Older Adults. (2010) 11:25–35. doi: 10.5042/qiaoa.2010.0526

18. Kutubaeva RZ. Analysis of life satisfaction of the elderly population on the example of Sweden, Austria and Germany. Popul Econ. (2019) 3:102–16. doi: 10.3897/popecon.3.e47192

19. Government Department Documents. China Government Website. Notice on Issuing the “14th Five-Year Plan” for Healthy Aging. Available online at: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-03/01/content_5676342.htm (accessed June 8, 2024).

20. Golden J, Conroy RM, Bruce I, Denihan A, Greene E, Kirby M, et al. Loneliness, social support networks, mood and wellbeing in community-dwelling elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2009) 24:694–700. doi: 10.1002/gps.2181

21. Luanaigh CÓ, Lawlor BA. Loneliness and the health of older people. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2008) 23:1213–21. doi: 10.1002/gps.2054

22. Fakoya OA, McCorry NK, Donnelly M. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: a scoping review of reviews. BMC Publ Health. (2020) 20:129. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8251-6

23. Bartlett H, Warburton J, Lui C-W, Peach L, Carroll M. Preventing social isolation in later life: findings and insights from a pilot Queensland intervention study. Ageing Soc. (2013) 33:1167–89. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X12000463

24. Zhang K, Kim K, Silverstein NM, Song Q, Burr JA. Social media communication and loneliness among older adults: the mediating roles of social support and social contact. Gerontologist. (2021) 61:888–96. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa197

25. Amagasa S, Fukushima N, Kikuchi H, Oka K, Takamiya T, Odagiri Y, et al. Types of social participation and psychological distress in Japanese older adults: a five-year cohort study. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0175392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175392

26. Lara R, Vázquez ML, Ogallar A, Godoy-Izquierdo D. Optimism and social support moderate the indirect relationship between self-efficacy and happiness through mental health in the elderly. Health Psychol Open. (2020) 7:2055102920947905. doi: 10.1177/2055102920947905

27. Kim J-H, Lee SG, Kim T-H, Choi Y, Lee Y, Park E-C. Influence of social engagement on mortality in Korea: analysis of the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (2006–2012). J Korean Med Sci. (2016) 31:1020–6. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.7.1020

28. Niedzwiedz CL, Richardson EA, Tunstall H, Shortt NK, Mitchell RJ, Pearce JR. The relationship between wealth and loneliness among older people across Europe: is social participation protective? Prev Med. (2016) 91:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.07.016

29. Ang S. Social participation and mortality among older adults in Singapore: does ethnicity explain gender differences? J Gerontol Ser B. (2018) 73:1470–9. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw078

30. Latham K, Clarke PJ. Neighborhood disorder, perceived social cohesion, and social participation among older Americans: findings from the national health & aging trends study. J Aging Health. (2018) 30:3–26. doi: 10.1177/0898264316665933

31. Elgar FJ, Davis CG, Wohl MJ, Trites SJ, Zelenski JM, Martin MS. Social capital, health and life satisfaction in 50 countries. Health Place. (2011) 17:1044–53. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.06.010

32. Pinto JM, Fontaine AM, Neri AL. The influence of physical and mental health on life satisfaction is mediated by self-rated health: a study with Brazilian elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2016) 65:104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.03.009

33. Tang S, Meng Q, Chen L, Bekedam H, Evans T, Whitehead M. Tackling the challenges to health equity in China. Lancet. (2008) 372:1493–501. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61364-1

34. You X, Zhang Y, Zeng J, Wang C, Sun H, Ma Q, et al. Disparity of the Chinese elderly's health-related quality of life between urban and rural areas: a mediation analysis. Br Med J Open. (2019) 9:e024080. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024080

35. Takano T, Nakamura K, Watanabe M. Urban residential environments and senior citizens' longevity in megacity areas: the importance of walkable green spaces. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2002) 56:913–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.12.913

36. Mao S, Lu N, Xiao C. Perceived neighborhood environment and depressive symptoms among older adults living in Urban China: the mediator role of social capital. Health Soc Care Community. (2022) 30:e1977–90. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13631

37. Luo Y, Wu X, Liao L, Zou H, Zhang L. Children's filial piety changes life satisfaction of the left-behind elderly in rural areas in China? Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:4658. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19084658

38. Sun J, Lyu S. Social participation and urban-rural disparity in mental health among older adults in China. J Affect Disord. (2020) 274:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.091

39. Huang W, Zhang C. The power of social pensions: evidence from China's new rural pension scheme. Am Econ J. (2021) 13:179–205. doi: 10.1257/app.20170789

40. Takagi D, Kondo K, Kawachi I. Social participation and mental health: moderating effects of gender, social role and rurality. BMC Publ Health. (2013) 13:701. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-701

41. Zhu Z, Ma W, Leng C, Nie P. The relationship between happiness and consumption expenditure: evidence from rural China. Appl Res Qual Life. (2021) 16:1587–611. doi: 10.1007/s11482-020-09836-z

42. Liu L-J, Guo Q. Loneliness and health-related quality of life for the empty nest elderly in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Qual Life Res. (2007) 16:1275–80. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9250-0

43. Guo Q, Bai X, Feng N. Social participation and depressive symptoms among Chinese older adults: a study on rural-urban differences. J Affect Disord. (2018) 239:124–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.036

44. Arling G. The elderly widow and her family, neighbors and friends. J Marriage Fam. (1976) 38:757–68. doi: 10.2307/350695

45. He W, Jiang L, Ge X, Ye J, Yang N, Li M, et al. Quality of life of empty-nest elderly in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med. (2020) 25:131–47. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2019.1695863

46. Shin Sh, Sok Sr. A comparison of the factors influencing life satisfaction between Korean older people living with family and living alone. Int Nurs Rev. (2012) 59:252–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2011.00946.x

47. Wilder SE. Communication practices and advice in later-life widowhood: “we just talked about what it is like to not have your buddy.” Commun Stud. (2016) 67:111–26. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2015.1119171

48. Wu Z-Q, Sun L, Sun Y-H, Zhang X-J, Tao F, Cui G-H. Correlation between loneliness and social relationship among empty nest elderly in Anhui rural area, China. Aging Ment Health. (2010) 14:108–12. doi: 10.1080/13607860903228796

49. Kim IK, Kim C-S. Patterns of family support and the quality of life of the elderly. Soc Indic Res. (2003) 62:437–54. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-0281-2_21

50. Tan K-K, He H-G, Chan SwC, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K. The experience of older people living independently in Singapore. Int Nurs Rev. (2015) 62:525–35. doi: 10.1111/inr.12200

51. Kouvonen A, Swift JA, Stafford M, Cox T, Vahtera J, Väänänen A, et al. Social participation and maintaining recommended waist circumference: prospective evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of aging. J Aging Health. (2012) 24:250–68. doi: 10.1177/0898264311421960

52. Kikuchi H, Inoue S, Fukushima N, Takamiya T, Odagiri Y, Ohya Y, et al. Social participation among older adults not engaged in full- or part-time work is associated with more physical activity and less sedentary time. Geriatr Gerontol Int. (2017) 17:1921–7. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12995

53. Achdut N, Sarid O. Socio-economic status, self-rated health and mental health: the mediation effect of social participation on early-late midlife and older adults. Isr J Health Policy Res. (2020) 9:4. doi: 10.1186/s13584-019-0359-8

54. Courtin E, Knapp M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Commun. (2017) 25:799–812. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12311

55. Ruiz-Comellas A, Sauch Valmaña G, Mendioroz Peña J, Roura Poch P, Sabata Carrera A, Cornet Pujol I, et al. Physical activity, emotional state and socialization in the elderly: study protocol for a clinical multicentre randomized trial. J Int Med Res. (2021) 49:3000605211016735. doi: 10.1177/03000605211016735

56. Smith JL, Bryant FB. The benefits of savoring life: savoring as a moderator of the relationship between health and life satisfaction in older adults. Int J Aging Hum Dev. (2016) 84:3–23. doi: 10.1177/0091415016669146

57. Gardiner C, Geldenhuys G, Gott M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review. Health Soc Care Commun. (2018) 26:147–57. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12367

58. Tian H, Chen J. Study on life satisfaction of the elderly based on healthy aging. J Healthc Eng. (2022) 2022:e8343452. doi: 10.1155/2022/8343452

59. Vogelsang EM. Older adult social participation and its relationship with health: rural-urban differences. Health Place. (2016) 42:111–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.09.010

60. Kim S-Y, Sok SR. Relationships among the perceived health status, family support and life satisfaction of older Korean adults. Int J Nurs Pract. (2012) 18:325–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2012.02050.x

61. Kushlev K, Heintzelman SJ, Oishi S, Diener E. The declining marginal utility of social time for subjective well-being. J Res Pers. (2018) 74:124–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2018.04.004

Keywords: aging, older adults, social participation, life satisfaction, loneliness

Citation: Wu M, Yang D and Tian Y (2024) Enjoying the golden years: social participation and life satisfaction among Chinese older adults. Front. Public Health 12:1377869. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1377869

Received: 28 January 2024; Accepted: 16 July 2024;

Published: 31 July 2024.

Edited by:

Shane Andrew Thomas, Federation University Australia, AustraliaReviewed by:

Gigi Lam, Hong Kong Shue Yan University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaCopyright © 2024 Wu, Yang and Tian. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yihao Tian, eWloYW90aWFuQHNjdS5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.