- 1Department of Medicine, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, United States

- 3Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, United States

- 4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Miami, Miami, FL, United States

- 5Family Action Network Movement, Miami, FL, United States

- 6Community Health and Empowerment Network, Miami, FL, United States

- 7College of Arts and Sciences, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, United States

Objective: To explore and describe the experiences of Haitians/Haitian Americans in Miami-Dade County, Florida during the COVID-19 pandemic, including their attitudes and practices towards vaccination.

Design: We interviewed 15 community members and 15 stakeholders in the Haitian/Haitian American community in Miami-Dade County, Florida using a semi-structured interview guide. The qualitative interviews were conducted between February 4, 2021, and October 1, 2021. They were conducted in both English and Haitian Creole, audio recorded transcribed/translated, and coded using thematic content analysis.

Results: The analyses revealed 9 major themes: (1) thoughts about the pandemic, (2) concerns about the COVID-19 vaccines, (3) healthcare access, February–October 2021, (4) intrapersonal relationship dynamics, (5) thoughts about individuals diagnosed with COVID-19, (6) thoughts about prevention measures (e.g., wearing masks, hand hygiene, social distancing, vaccination), (7) mental health struggles and coping, (8) food insecurity, and (9) overall experiences of the pandemic. The findings reveal that the COVID-19 public health emergency negatively affected Haitians/Haitian Americans across several domains, including employment, healthcare access, personal relationships, and food security.

Conclusion: This research echoes the compounding negative experiences reported by multiple disadvantaged groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. From loss of employment to healthcare barriers, the pandemic forced many Haitians/Haitian Americans into greater economic and social instability. Interventions addressing these issues should recognize how these factors may interact and compound the experiences of this group. Health and public health agencies should work alongside community partners to build trust so that preventive efforts will be more readily accepted during public health emergencies.

Introduction

The first documented COVID-19 death in Miami-Dade County was a 94-year-old Haitian woman, and from that point on, Haitians/Haitian Americans were severely impacted by the pandemic (1). Although COVID-19 negatively affected the entire world, within the United States (U.S.) and Florida (FL), its impact on racial and ethnic minorities was devastating, with those populations having higher than average rates of infection, hospitalization, and mortality (2). Since the pandemic began in 2020, African American/Black individuals have consistently faced a disproportionate burden of COVID-19-related health and socioeconomic risks (3). Unfortunately, state health officials did not always routinely track diagnoses by ethnicity, and Haitian/Haitian Americans, like other Afro-Caribbeans, are often grouped with African Americans in reporting, confounding attempts to parse the experiences of different ethnic groups (1, 4). Haitians reportedly account for about 4% of the population in Miami-Dade County (1). Miami-Dade County has a population of approximately 2.7 million individuals (5). Haitian Americans accounted for at least 5% of those affected by COVID-19. As of the end of August 2020, at least 105 of the more than 2,000 deaths in Miami-Dade County had been members of the Haitian community. This is thought to be an under count (1). Given missing ethnicity data for hospitalizations, it is not possible to discern if Haitians were disproportionately affected (1). Many factors contributed to the disproportionate negative effects of COVID-19 on Black individuals, including linked historical structural inequities (e.g., racism, poverty, food deserts), more crowded and polluted living conditions, a higher likelihood of having public front-facing employment (e.g., service, food, transportation industries), and the population’s likelihood of having more pre-existing comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease) (6). Economic instability likely amplified the pandemic’s negative consequences for many Haitians and Haitian Americans (4). The Haitian community is an ethno-racial, linguistic community which also contains individuals with low income. Data from the Thrive305 survey conducted in Miami-Dade County by the government collected data from participants of Haitian descent during the COVID-19 pandemic indicated evidence of discrimination. When answering the question, I think that residents of all backgrounds including my own, are welcomed and respected “by fellow residents of Miami-Dade”, the highest numbers of responses were “disagree.” In addition, when asked “I think that residents of all backgrounds, including my own, have equal employment opportunities in Miami-Dade County,” the highest numbers of responses were “strongly disagree” (7).

The limited current literature suggests that the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were felt disproportionately by Haitian/Haitian Americans in many ways (2, 4). For example, 40% of the Haitian diaspora in the U.S. works in public service-related industries, which were among the first to face major economic loss and unemployment due to social distancing policies (8). In addition, food insecurity for many increased, and Black and Latino households were twice as likely as white households to report that their families did not have enough to eat (9). COVID-19 hurt social relationships and mental health as well (9). In a case study conducted in Miami Gardens, found that Black community members rated their physical and mental health less positively since the pandemic began, reporting increased loneliness (9, 10).

Structural interventions are needed to reduce the pandemic’s harm on this population, including making testing and vaccines free and accessible, improving tracing/reporting data, and continuing economic relief for those affected. In addition, existing prevention methods (such as wearing masks) must be better utilized to reduce morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, although vaccination is known to be the most effective mechanism to prevent COVID morbidity and mortality, vaccination rates remain low among Black communities in the U.S. and in Haiti (10, 11). Chery et al. (12) found that among 1,071 survey respondents in Haiti, only 27% had positive attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine and had been vaccinated.

This study aimed to better understand the experiences of Haitians/Haitian Americans, during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly with regard to (1) thoughts/concerns about the pandemic, (2) thoughts about COVID-19 vaccines, (3) healthcare access during the study period, (4) intrapersonal relationship dynamics, (5) thoughts about individuals diagnosed with the COVID-19, (6) prevention measures (e.g., wearing masks), (7) mental health struggles and coping, (8) food insecurity, and (9) overall experiences. A better understanding of Haitians/Haitian Americans’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic will allow us to provide guidance on addressing its continued negative consequences and develop more effective mitigation strategies for future pandemics and other public health emergencies. The Health Equity Impact Assessment highlights social determinants of health that are relevant to Haitians/Haitian Americans and COVID-19 (13). The social determinants of health addressed in this manuscript are income/social status, social support networks, employment, social environments, personal health practices, coping skills, health services, and culture.

Materials and methods

A qualitative research design was used to collect and analyze data. In partnership with the Family Action Network Movement and Community Health and Empowerment Network, 30 Haitians/Haitian Americans were recruited face-to-face and by phone. Participants included community members and those in community leadership positions (stakeholders) in Miami, FL. The participants did not have a relationship with the study team prior to the study. The study used convenience sampling. Data were collected between February 4, and October 1, 2021, at community-based organizations, churches, and via phone. Participants were recruited using flyers and face-to-face by study team and staff members of community partners at the Family Action Network Movement and Community Health and Empowerment Network, as well as other community-based organizations and churches across Miami-Dade County. Participants who expressed interest and met eligibility criteria were enrolled. The research team consisted of female and male staff experienced in qualitative research and bilingual in Haitian Creole and English. The interview guides were reviewed and modified with feedback from the Family Action Network Movement and Community Health and Empowerment Network. Thirty sociodemographic surveys and semi-structured interviews were conducted with Haitians/Haitian Americans (15 community members and 15 stakeholders). One potential participant was unable to complete the study due to scheduling conflicts. The interviews were conducted by the principal investigator (an MD), a research associate, a community consultant, and three other research team members in person at a private space and/or by the phone. The study team verbally read the consent form to participants and provided a copy of the document in their preferred language. All participants provided verbal informed consent to participate in this study. Interviews were audio recorded and lasted for 30–45 min, during which notes were taken. No interviews were repeated. Interviews conducted in Haitian Creole were later transcribed and translated to English. All participants were given $30 gift cards for their participation. The University of Miami Institutional Review Board (Study #: 20200190) approved this study’s protocol and materials prior to data collection in the field.

Measures

Sociodemographic assessments

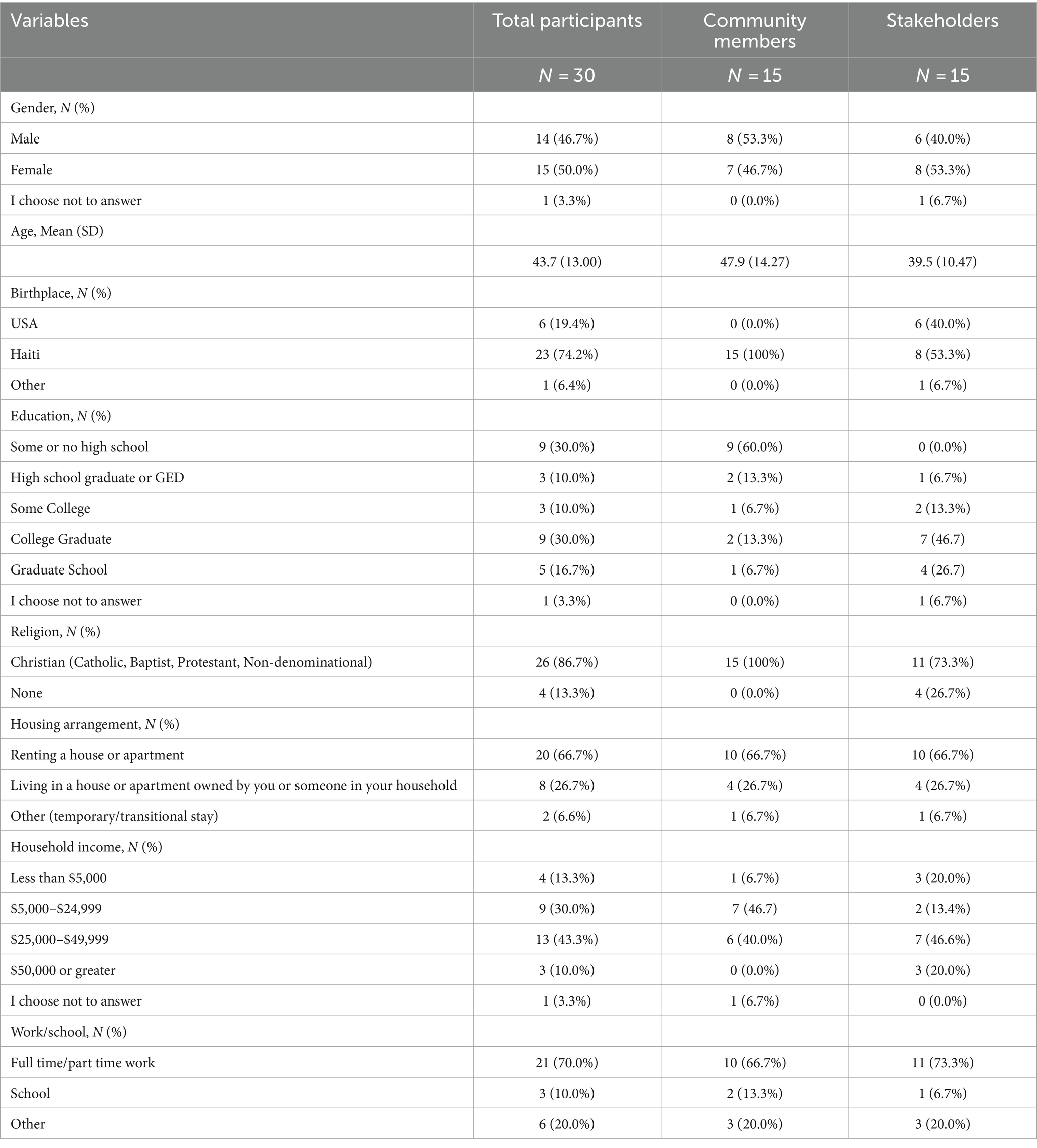

The verbally administered sociodemographic survey collected information on gender, age, birthplace, education, religion, housing status, income, and work/school status. Demographic characteristics can be found in Table 1. All responses were recorded into Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure web-based application used for data collection (14).

Semi-structured interviews

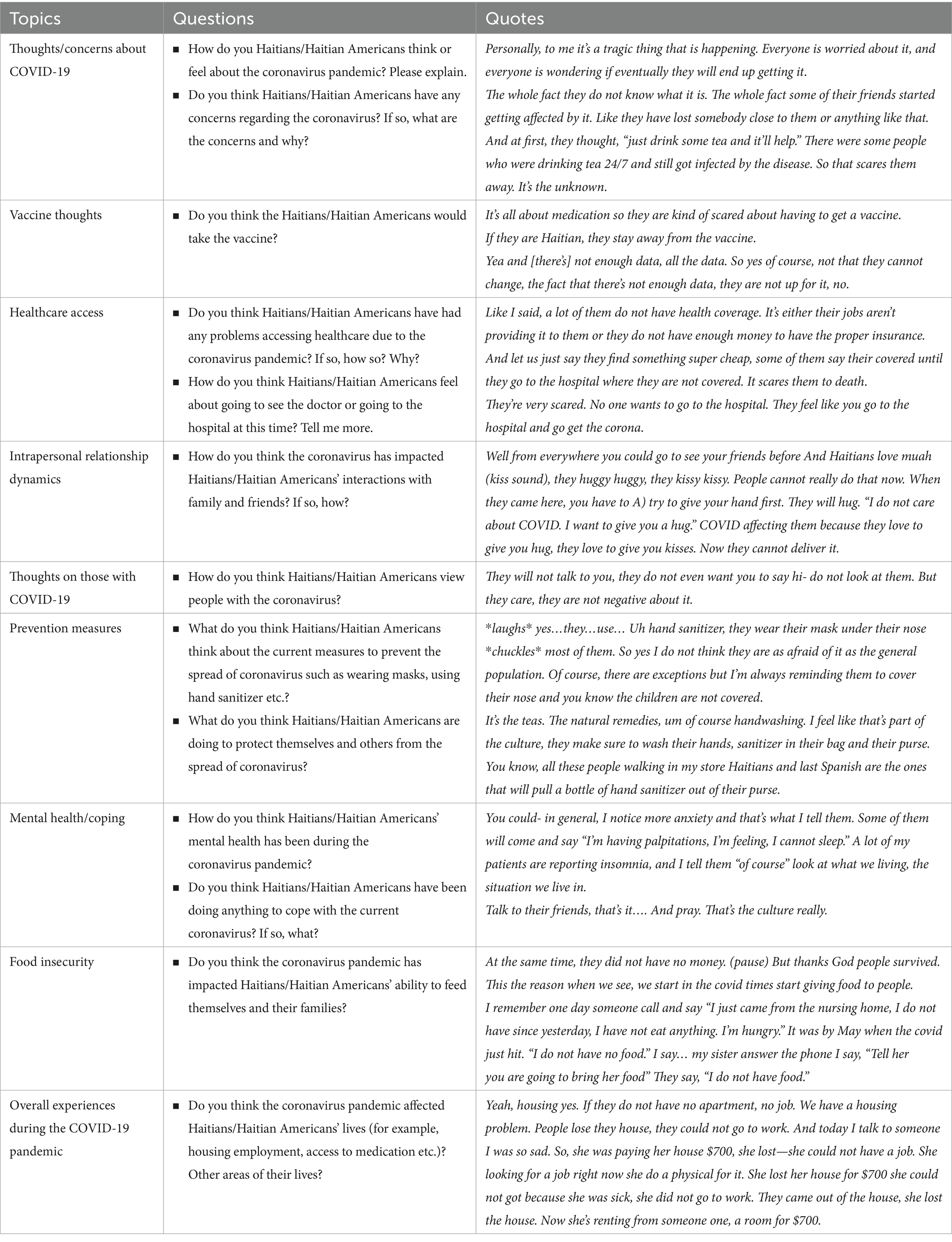

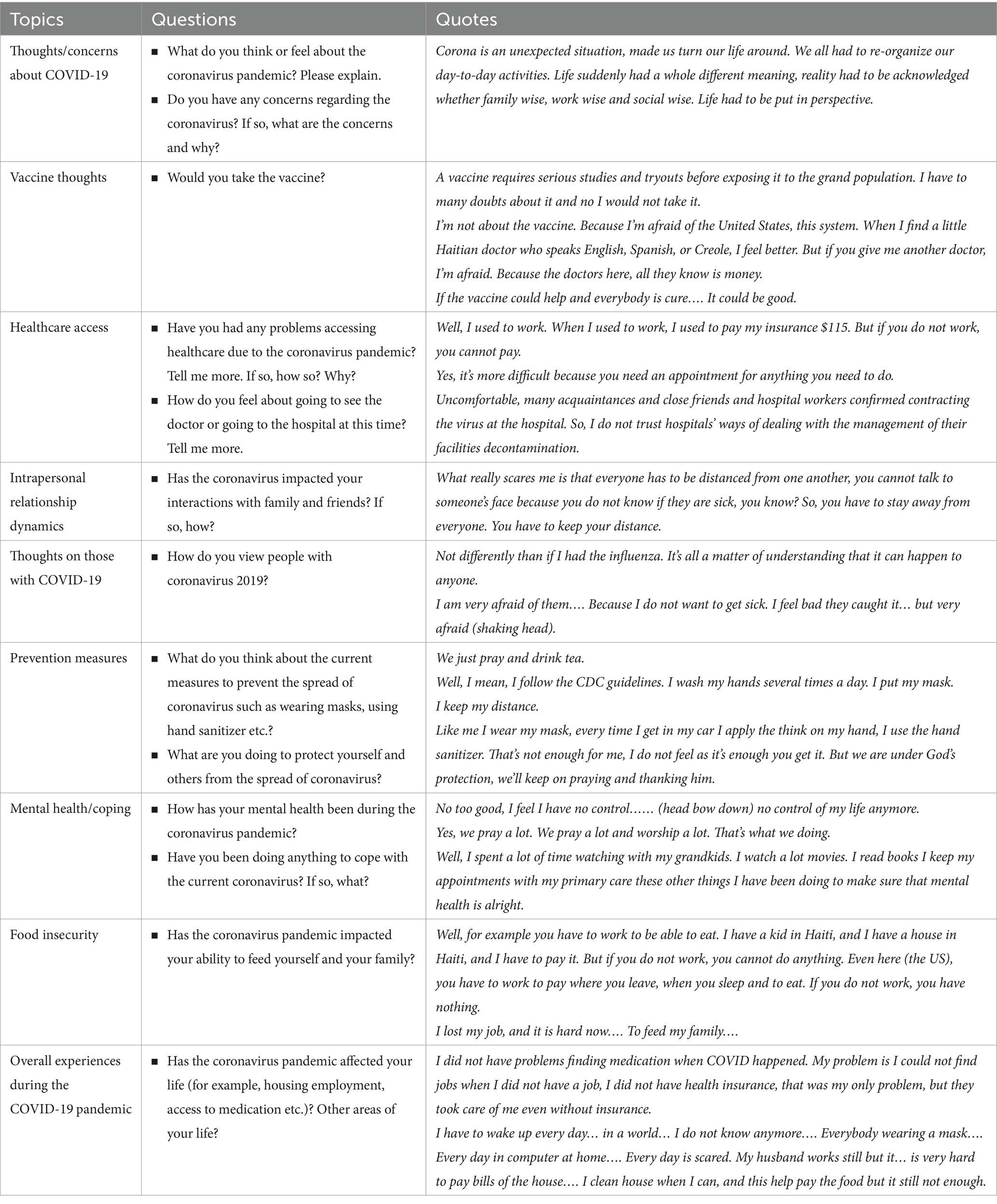

The semi-structured interviews encouraged discussions regarding experiences during the pandemic and the vaccine stance(s) of individuals within the Haitian community. Separate interview guides were created for community members and stakeholders to assess their thoughts. We obtained data regarding 9 main topics: (1) Thoughts/concerns about the pandemic, (2) Thoughts about COVID-19 vaccines, (3) Healthcare access during the study period, (4) Intrapersonal relationship dynamics, (5) Thoughts about individuals diagnosed with the COVID-19, (6) Prevention measures (e.g., wearing masks, hand hygiene, social distancing, and COVID-19 vaccination), (7) Mental health struggles and coping, (8) Food insecurity, and (9) Overall experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The members of the community were asked questions about their own thoughts on the coronavirus pandemic, how it affected their personal lives, and whether they would take the vaccine(s) (which, at that time, were under development and beginning their initial release). The stakeholders were asked to relay their thoughts about the pandemic and the experiences of Haitian and Haitian American community members. Interview guides with verbatim questions are presented in Tables 2, 3.

Data analysis

A codebook was developed by the principal investigator, supervising researcher, and a study team member based on 10 interviews. A sample of 3 interviews was coded by both the principal investigator and a study team member using NVivo. The Kappas were above 0.8. The resulting codebook was used to code the remainder of the interviews. With the 30 interviews, we were able to achieve data saturation.

Results

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants. Of the 30 participants, 15 were community members, and 15 were stakeholders. Participants self-identified as female (15; 50%) and male (14; 46.7%), while one preferred not to answer (1; 3.3%). The average age of the community members was 47.9 (SD = 14.27), while the stakeholders’ average was 39.5 (SD = 10.4). All 15 of the community members were born in Haiti. Of the stakeholders, 6 were born in the U.S., 8 were born in Haiti, and 1 was born elsewhere. Approximately 60% of the community members had not completed high school while 93% of the stakeholders graduated from high school or higher. Of the 30 participants, 86.7% identified as Christian. Over half (66.7%) of the community members and stakeholders reported that they were renting a house or apartment. More than 53% of the community members reported a household income of less than $25,000, and about 67% of them were working full- or part-time. Over half (66.7%) of the stakeholders reported an income of $25,000 or more, with 73.3% working full- or part-time. The community stakeholders represented community-based organizations, were medical professionals, or worked for the government. Twenty interviews were conducted in English and ten were in Haitian Creole.

Both community members and stakeholders provided insightful information regarding (1) thoughts/concerns about the pandemic, (2) thoughts about COVID-19 vaccines, (3) healthcare access during the study period, (4) intrapersonal relationship dynamics, (5) thoughts about individuals diagnosed with the COVID-19, (6) prevention measures (e.g., wearing masks, hand hygiene, social distancing, and COVID-19 vaccination), (7) mental health struggles and coping, (8) food insecurity, and (9) overall experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Thoughts/concerns regarding COVID-19

Overall, participants thought the COVID-19 had a negative effect on the Haitian community. Among this group, COVID-19 concern had been at the center of the participants’ thoughts due to misinformation about the disease, fear of contracting the infection, and absence of a cure. One participant noted: “Personally, to me, it’s a tragic thing that is happening. Everyone is worried about it, and everyone is wondering if eventually they will end up getting it.”

Thoughts about vaccines

While 33% of the community members expressed that they would be willing to take the new COVID-19 vaccine, 67% responded that they would not take it or were hesitant. There were some concerns regarding the speed of the vaccine’s development and mistrust of the medical community. There were also suggestions of a conspiracy involving the COVID-19 vaccine. One participant suggested that “If they are Haitian, they stay away from the vaccine.” This suggests that culture may play a role.

Healthcare access

The pandemic affected access to healthcare for our study participants. Many discussed losing their jobs and therefore not being able to pay for care. In addition, some clinics were closed, leading to worsened healthcare access. Both health services and employment/income, key social determinants, were affected. One of the stakeholders noted: “Like I said, a lot of them do not have health coverage. It’s either their jobs aren’t providing it to them, or they do not have enough money to have the proper insurance. And let us just say they find something super cheap, some of them say they are covered until they go to the hospital where they are not covered. It scares them to death.”

Intrapersonal relationship dynamics

Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative effect on social relationships and environments. Some members of the community (3 out of 15 community members) experienced isolation and were unable to express themselves in a culturally congruent manner. One participant noted that “You could go to see your friends before, and Haitians love muah (kissing sound), they huggy huggy, they kissy kissy. People cannot really do that now.”

Thoughts on those diagnosed

At that time, there was both concern for those diagnosed and some fear of being exposed to COVID. In addition, social stigma against individuals with COVID was not unusual. Social environments and social support networks were affected. All of the community members who were infected with COVID (3 out of 3 community members) expressed that they had felt isolated primarily because of the behavior of others towards them: “They will not talk to you, they do not even want you to say hi- do not look at them. But they care, they are not negative about it.”

Prevention measures

Overall, it appeared that at that moment, the community was attempting to follow behavioral prevention measures. One participant noted that there might be a generational difference in willingness to follow guidelines, such that older individuals were more adherent. In addition, some participants (8 out of 15 community members) turned to more traditional prevention measures, arguing that herbal remedies could play a significant role in prevention. “It’s the teas. The natural remedies, um of course handwashing. I feel like that’s part of the culture, they make sure to wash their hands, sanitizer in their bag and their purse.”

Mental health/coping

Prayer and spirituality was particularly important for many individuals (6 out of 15 community members) in the Haitian community for both coping and prevention. The participants of this study believed that religion and social support from friends played a healing role in coping with the COVID-19 pandemic. “Talk to their friends, that’s it…. And pray. That’s the culture really.”

Food insecurity

Food insecurity was a problem for some (5 out of 15 community members). The participants connected job loss with an inability to provide essentials for their families such as food. “Tell her you are going to bring her food. They say I do not have food.”

Overall experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 appeared to affect members of the Haitian community on many levels. Employment was key. Several members reported that they lost their jobs or had a family member lose a job (7 out of 15 community members). Employment affected other areas of life as well, such as healthcare access and food insecurity. “I mean it affects the Black community a lot because a lot of us was already into poverty so let us say a lot of people was losing their jobs and the government was not really helping us really. So, they were giving out stimulus but they not really doing anything to help the Black community with their needs.”

Discussion

In the U.S., the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted racial and ethnic minority groups negatively, including Haitians/Haitian Americans (2). Our findings agree with others suggesting that this population experiences similar barriers to healthcare as other immigrant communities in South FL (4). The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants in this study provide a holistic representation of this segment of the Miami community. With nearly three-fourths of the participants having been born in Haiti, the findings of this study offer unique insights that reflect the lived experiences and perceptions of first-generation immigrants, an essential factor when examining their responses to a global health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic.

One key observation from this study is the prevailing apprehension towards the COVID-19 vaccine. The hesitancy mirrored findings from Chery et al., which also noted reluctance among the Haitian population due to factors such as misinformation, cultural beliefs, and lack of trust in the health system (12). The concerns regarding the rapid development of the COVID-19 vaccine and conspiracy theories seen in this sample suggest that external narratives play a significant role in shaping perceptions of vaccines. Such apprehensions are consistent with the community’s historical marginalization and the resulting mistrust towards medical interventions and historically based mistrust of the medical establishment, which can be linked to earlier health crises (15). Furthermore, studies from the Caribbean have found rural dwelling, lower education, and financial insecurity to be associated with vaccine hesitancy among Haitians/Haitian Americans (4, 16, 17). These barriers prompted Haitian/Haitian Americans to be less likely to be vaccinated against COVID-19 than other racial and ethnic minority groups (16–21). Avoidance of vaccines was also attributed to participants’ preference for traditional, cultural remedies over the use of Western medicine (19, 22–24). The apprehension towards the COVID-19 vaccine observed among Haitians/Haitian Americans parallels concerns seen in other minoritized populations within the US, such as Cubans, other Afro-Caribbean groups, and Latin Americans. These groups similarly grapple with misinformation, cultural beliefs, and a deep-seated mistrust towards the health system. For example, research among Latin American immigrants has highlighted significant hesitancy towards vaccinations, attributed to a combination of misinformation spread through social media and historical distrust in government and healthcare institutions (25–27). Similarly, studies on Black Americans have documented longstanding mistrust in the U.S. healthcare system, which has contributed to vaccine hesitancy, partly stemming from unethical historical medical experiments like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (28). These patterns underscore a broader theme of mistrust among minoritized populations, stemming from historical injustices and compounded by current systemic barriers in healthcare access and information dissemination.

Our findings on food insecurity draw attention to the cascading effects of economic challenges. The interplay between employment, healthcare access, and food insecurity elucidated by study results is reminiscent of the multifaceted vulnerabilities, such as having jobs affected by economic downturns and healthcare or immigration barriers observed during past crises in the Haitian diaspora (29). The compounded vulnerabilities of Haitians/Haitian Americans are not isolated experiences but are shared across various minoritized communities. For instance, Afro-Caribbean and Latin American immigrants often encounter language barriers, immigration status concerns, and lack of culturally competent care, which exacerbate disparities in healthcare (30). Food insecurity, amplified by the pandemic, has similarly affected Black, Latino, and immigrant households at disproportionately high rates, reflecting broader systemic inequities (31, 32).

This study reveals structural challenges in urban settings like Miami, aligning with literature that delves into the challenges faced by immigrant communities in accessing healthcare (12, 33). The effects of the pandemic on intrapersonal relationships in the community suggest a deeper socio-cultural rift. Cultural congruence in expressing emotions and maintaining relationships is integral to communities with close-knit family and friendship ties, such as those of this community (34, 35). Thus, the reported isolation due to COVID-19 could have potential long-term implications on the community’s mental and emotional well-being.

Preventive measures used by this community reflected an interplay of traditional practices and global health guidelines. The significant role of herbal remedies signifies a blend of ancestral knowledge with contemporary health advice, similar to patterns seen in other minority communities (36). This blending was further echoed in the reliance on prayer and spirituality, aligning with past literature on the Haitian community’s coping mechanisms (37).

While the COVID-19 pandemic has affected communities globally, this study confirms the disproportionate negative experiences faced by members of the Haitian community in Miami, reflecting both universal challenges and unique socio-cultural dynamics. Although the COVID-19 pandemic started over 3 years ago, these data are important for addressing the support needs of this community and for overcoming vaccine hesitancy in future pandemics. Further studies are needed to explore these and other negative health consequences that disproportionately affected this population during COVID and other public health emergencies.

Although those who were interviewed brought up mistrust of the medical community, we were unable to distinguish between mistrust of the medical community and mistrust directed towards the public health community. Future studies should delineate and characterize these differing forms or reasons for mistrust directed at each of these two professional communities.

Finally, to address social determinants of health, structural interventions are needed to improve employment opportunities and other resources for this population to cope with the negative experiences due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Reducing healthcare barriers, building trust within the community, and improving transparency and communication are among the critical actions that can be taken to improve this population’s access and uptake of public health interventions like the COVID-19 vaccines. Addressing these challenges will require an integrated coordinated approach, taking into account the Haitian/Haitian American community’s cultural norms, historical experiences, and structural barriers. All of these lessons learned have practice implications for how medicine and public health should improve to better deal with the COVID-19 crisis and other similar issues that are likely to emerge or reemerge in future public health emergencies. Future work may benefit from comparing the experiences of Haitians and other communities using larger samples. Furthermore, future work on the Haitian community may benefit from a priori use of methodologies such as the Health Equity Impact Assessment.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board (Study #: 192 20200190). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the [patients/participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin] was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Verbal consent from participants was approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board.

Author contributions

CS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DR: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VE: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DM: Writing – review & editing. AF: Writing – review & editing. MT: Writing – review & editing. AM: Writing – review & editing. MA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research is supported by the University of Miami’s Center for HIV and Research in Mental Health (CHARM; P30MH116867 (D-ARC), P30MH133399 (ARC) [NIMH]). The PI (Sternberg) is also supported by the Miami Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, funded by a grant (P30AI073961) from the NIH (which is supported by the following NIH co-funding and participating institutes and centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMHD, NIA, and NINR); the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, award number P50MD017347-02S1 and the University of Miami CTSI through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, award number KL2TR002737. SD is also funded by R56MH121194 and R01MH121194 from NIMH. This work is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institute of Health.

Acknowledgments

The team would like to thank the study participants. We would also like to thank the Family Action Network Movement, the Community Health and Empowerment Network and their staff. We would also like to thank the University of Miami Writing Center for the editorial support. We would also like to thank Blonsky Batalien for his help with data collection on this project.

Conflict of interest

AF was employed by Family Action Network Movement. MT is the President/CEO of the Community Health and Empowerment Network. SD is a co-investigator on a Merck & Co. funded project on “A Qualitative Study to Explore Biomedical HIV Prevention Preferences, Challenges and Facilitators among Diverse At-Risk Women Living in the United States” and has served as a workgroup consultant on engaging people living with HIV for Gilead Sciences, Inc.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Charles, J., and Ovalle, D. "COVID-19, a stigma to many, quietly taking a toll on South Florida’s Haitian community." Miami Herald Coronavirus takes a heavy toll on Haitians in South Florida Miami Herald (2020). Available at: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/haiti/article244725852.html (Accessed May 25, 2024)

2. Romano, SD, Blackstock, AJ, and Taylor, EV. Trends in Racial and Ethnic Disparities in COVID-19 Hospitalizations, by Region — United States, March–December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:560–565. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7015e2

3. Millett, GA, Jones, AT, Benkeser, D, Baral, S, Mercer, L, Beyrer, C, et al. Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on black communities. Ann Epidemiol. (2020) 47:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.003

4. Semé, JL, Bivins, BL, Sternberg, CA, Barnett, JD, Junis-Florian, T, Nicolas, G, et al. The educational, health, and economic impacts of COVID-19 among Haitians in the USA: time for systemic change. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2022) 9:2171–9. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01156-8

5. Miami-Dade County, "About Miami-Dade County." (2022) Available at: https://www.miamidade.gov/global/disclaimer/about-miami-dade-county.page (Accessed June 28, 2024).

6. Webb Hooper, M, Napoles, AM, and Perez-Stable, EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. (2020) 323:2466–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598

7. Miami-Dade County, “Thrive305.” (2021) Available at: www.miamidade.gov/initiative/thrive305/home.page (Accessed June 25, 2024).

8. Bovell-Ammon, A, Ettinger de Cuba, S, Lê-Scherban, F, Rateau, L, Heeren, T, Cantave, C, et al. Changes in economic hardships arising during the COVID-19 pandemic: differences by nativity and race. J Immigr Minor Health. (2023) 25:483–8. doi: 10.1007/s10903-022-01410-z

9. Paat, Y, Orezzoli, M, Ngan, C, and Olimpo, JT. Racial health disparities and black heterogeneity in COVID-19: a case study of Miami Gardens. J Appl Soc Sci. (2023) 17:190–208. doi: 10.1177/19367244221142565

10. Embrett, M, Sim, SM, Caldwell, HAT, Boulos, L, Yu, Z, Agarwal, G, et al. Barriers to and strategies to address COVID-19 testing hesitancy: a rapid scoping review. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:750. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13127-7

11. Virginia Department of Health. "COVID-19 testing and contact tracing health equity guidebook. (2020). Available at: https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/76/2020/09/Testing-and-Contact-Tracing-Health-Equity-Guidebook-July-2020_Copyright.pdf (Accessed March 31, 2024)

12. Chery, MJ, Dubique, K, Higgins, JM, Faure, PA, Phillips, R, Morris, S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in three rural communes in Haiti: a cross-sectional study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2023) 19:2204048. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2023.2204048

13. Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. "Health equity impact assessment workbook". (2012). Available at: https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/professionals/heia/health-equity-impact-assessment-workbook2012-pdf.pdf (Accessed June 28, 2024).

14. Kragelund, SH, Kjærsgaard, M, Jensen-Fangel, S, Leth, RA, and Ank, N. Research electronic data capture (REDCap®) used as an audit tool with a built-in database. J Biomed Inform. (2018) 81:112–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2018.04.005

15. Farmer, P . AIDS and accusation: Haiti and the geography of blame, updated with a new preface University of California Press (2006).

16. Saint-Jean, G, and Crandall, LA. Sources and barriers to health care coverage for Haitian immigrants in Miami-Dade county, Florida. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2005) 16:29–41. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0016

17. Saint-Jean, G, and Crandall, LA. Utilization of preventive care by Haitian immigrants in Miami, Florida. J Immigr Minor Health. (2005) 7:283–92. doi: 10.1007/s10903-005-5125-z

18. Baack, BN, Abad, N, Yankey, D, Kahn, KE, Razzaghi, H, Brookmeyer, K, et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage and intent among adults aged 18-39 years – United States, March-May 2021. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:928–33. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7025e2

19. Coreil, J, Lauzardo, M, and Heurtelou, M. Cultural feasibility assessment of tuberculosis prevention among persons of Haitian origin in South Florida. J Immigr Health. (2004) 6:63–9. doi: 10.1023/B:JOIH.0000019166.80968.70

20. Khubchandani, J, and Macias, Y. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in Hispanics and African-Americans: a review and recommendations for practice. Brain Behav Immun Health. (2021) 15:100277. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100277

21. Kricorian, K, and Turner, K. COVID-19 vaccine reluctance in older Black and Hispanic adults: cultural sensitivity and institutional trust. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2021) 69:7.

22. Goodman, A . Religious and cultural interpretation of illness in the Boston Haitian community and its impact on healthcare. Gynecol Oncol. (2005) 99:S199–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.082

23. Nicolas, G, DeSilva, AM, Grey, KS, and Gonzalez-Eastep, D. Using a multicultural lens to understand illnesses among Haitians living in America. Prof Psychol Res Pract. (2006) 37:702–7. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.37.6.702

24. Volpato, G, Godinez, D, Beyra, A, and Barreto, A. Uses of medicinal plants by Haitian immigrants and their descendants in the province of Camaguey, Cuba. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. (2009) 5:16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-16

25. Garcini, LM, Ambriz, AM, Vázquez, AL, Abraham, C, Sarabu, V, Abraham, C, et al. Vaccination for COVID-19 among historically underserved Latino communities in the United States: perspectives of community health workers. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:7. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.969370

26. McFadden, SM, Demeke, J, Dada, D, Wilton, L, Wang, M, Vlahov, D, et al. Confidence and hesitancy during the early roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines among black, Hispanic, and undocumented immigrant communities: a review. J Urban Health. (2022) 99:3–14. doi: 10.1007/s11524-021-00588-1

27. Rossi, MM, Parisi, MA, Cartmell, KB, and McFall, D. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the Hispanic adult population of South Carolina: a complex mixed-method design evaluation study. BMC Public Health. (2023) 23:2359. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16771-9

28. Corbie-Smith, G . Vaccine hesitancy is a scapegoat for structural racism. JAMA Health Forum. (2021) 2:e210434. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0434

29. Higashi, RT, Lee, SC, Pezzia, C, Quirk, L, Leonard, T, and Pruitt, SL. Family and social context contributes to the interplay of economic insecurity, food insecurity, and health. Ann Anthropol Pract. (2017) 41:67–77. doi: 10.1111/napa.12114

30. Jacquez, F, Vaughn, L, Zhen-Duan, J, and Graham, C. Health care use and barriers to care among Latino immigrants in a new migration area. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2016) 27:1761–78. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0161

31. Dabone, C, Mbagwu, I, Muray, M, Ubangha, L, Kohoun, B, Etowa, E, et al. Global food insecurity and African, Caribbean, and black (ACB) populations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2022) 9:420–35. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-00973-1

32. Payán, DD, Perez-Lua, F, Goldman-Mellor, S, and Young, M-EDT. Rural household food insecurity among Latino immigrants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients. (2022) 14:Article 13. doi: 10.3390/nu14132772

33. Suphanchaimat, R, Kantamaturapoj, K, Putthasri, W, and Prakongsai, P. Challenges in the provision of healthcare services for migrants: a systematic review through providers' lens. BMC Health Serv Res. (2015) 15:390. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1065-z

34. Long, E, Patterson, S, Maxwell, K, Blake, C, Bosó Pérez, R, Lewis, R, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on social relationships and health. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2022) 76:128–32. doi: 10.1136/jech-2021-216690

35. Naser, AY, Al-Hadithi, HT, Dahmash, EZ, Alwafi, H, Alwan, SS, and Abdullah, ZA. The effect of the 2019 coronavirus disease outbreak on social relationships: a cross-sectional study in Jordan. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2021) 67:664–71. doi: 10.1177/0020764020966631

36. Malapela, RG, Thupayagale-Tshweneagae, G, and Baratedi, WM. Use of home remedies for the treatment and prevention of coronavirus disease: an integrative review. Health Sci Rep. (2023) 6:e900. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.900

Keywords: COVID-19, Haitians, Haitian Americans, healthcare, Miami-Dade, pandemic

Citation: Sternberg CA, Richard D, Daniel VE, Chery MJ, Beauvoir M, Marcelin D, Francois A, Titus M, Mann A, Alcaide ML and Dale SK (2024) Exploring the experiences of Haitians/Haitian Americans in Miami-Dade County, Florida during the COVID-19 pandemic: how this community coped with the public health emergency. Front. Public Health. 12:1364260. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1364260

Edited by:

Monica Catarina Botelho, Universidade do Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Tony Kuo, University of California, Los Angeles, United StatesGiada Minelli, National Institute of Health (ISS), Italy

Copyright © 2024 Sternberg, Richard, Daniel, Chery, Beauvoir, Marcelin, Francois, Titus, Mann, Alcaide and Dale. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Candice A. Sternberg, Yy5hdXJlbHVzQG1pYW1pLmVkdQ==

Candice A. Sternberg

Candice A. Sternberg Danelle Richard1

Danelle Richard1 Maurice J. Chery

Maurice J. Chery Maika Beauvoir

Maika Beauvoir Dora Marcelin

Dora Marcelin Maria L. Alcaide

Maria L. Alcaide