- Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

Background: Sailors undergo anxiety and sleep disturbances due to prolonged journeys and the nature of their work on ships. Earlier studies indicate Cyclic Meditation (CM) being beneficial for managing anxiety and improving sleep quality. Thus, the current study was designed to investigate the effect of CM on anxiety and sleep quality among sailors.

Materials and methods: Fifty sailors were assigned to experimental (n = 25) and control (n = 25) groups. The experimental group received 45 min of CM, 7 days a week for 3 weeks. Control group continued with their routine activities and were offered CM practice the following 3 weeks. Hamilton Anxiety Scale for anxiety (HAM-A) and the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) for sleep along with blood pressure and pulse rate were taken at baseline and by the end of 3 weeks. Data were analyzed using Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (RM ANOVA) for within and between group effects.

Results: Significant differences were found between the groups following 3 weeks for all the variables. Experimental group demonstrated reduced anxiety (p < 0.001) and improved sleep (p < 0.001) along with improvements in blood pressure and pulse rate. The control group did not show any significant changes following 3 weeks.

Conclusion: CM could be incorporated as a routine for sailors to manage their anxiety and improve sleep quality during the period on board ships.

1 Introduction

Currently, 80% of the world trade is carried out by the international shipping industry (1). Waterborne vessels like barges, ships, boats, and sailboats are the only means of transport over the water bodies. The work of a sailor is to foresee the dangers and obstructions in the path of water-based vessels and manage cargo onboard ships and other vessels. According to the International Chamber of Shipping, the estimated worldwide population of seafarers serving on internationally trading merchant ships is 1,892,720. Of these, 857,540 are officers and 1,035,180 are ratings. The largest suppliers of ratings and officers working on merchant ships are the Philippines, the Russian Federation, Indonesia, China, and India (2).

The shipboard environment and nature of shipping services can adversely impact physical and psychological health of the onboard personnel (3). A study conducted on over 1,000 sailors reported greater concerns over habitability (e.g., high noise, high temperature, extreme weathers, shaking movements etc.) were directly associated with poorer mood and greater symptoms of anxiety and depression (4). Furthermore, these sailors often work at rotating shifts, which itself can lead to increased stress and psychopathologies (5). Additionally, numerous studies have documented the adverse impact of these environment and occupational factors on sleep health and functioning (2, 4, 6), which have in turn impact on the psychological health (7). In addition, social factors such as separation from family and friends repeatedly and for prolonged duration, with limited communication due to technological constraints, and work schedules contribute to poor mental health (3, 8). These disruptions in communication and concerns about friends and family back home can lead to loneliness or greater deployment stress (9, 10). Also, interpersonal conflict in ships can lead to stress and psychological health problems among sailors (3). Thus, anxiety and poor sleep quality are common health issues among the sailors on board.

Several coping strategies are deployed to help sailors get through the difficult working environment. Team building activities bring cohesion among sailors, which can help them stay motivated and protect each other during their time on board (11, 12). To overcome or maintain their psychological health, many ships implement mental health programs, basic mental health facilities and access to counseling services for those who need them (13, 14). Several psychotherapy methodologies including cognitive behavioral therapy are employed to combat the mental health issues among sailors (15). In addition, physical and social programs like fitness facilities and movie screenings etc. are also encouraged while on board (16). Also participating in sports can boost mental health (17). The World Health Organization and National health agencies are providing guidelines related healthcare provision in ships, including the use of alternative and complementary medical practices (18). This expansion provides a great opportunity to demonstrate the usefulness of integrative health at the healthcare system level in various fields (19). The Taheri study, along with research by Camacho-Montaño LR (20) and Williams BA (21), highlights how confinement leads to decreased physical activity and poorer sleep quality among athletes, children, and prisoners, respectively. These findings underscore the detrimental impact of confinement on various occupational groups, contributing to adverse health outcomes within the population (22).

Yoga represents a holistic approach that encompasses multiple dimensions, combining physical, mental, social, and spiritual elements within its ambit. The beneficial effects of yoga have been evidenced across diverse occupational fields. In recent studies, yoga practices are found to be useful in managing pain (23), chronic venous insufficiency and fatigue (24), visual strain (25, 26) among various occupational groups. Specific yoga practices such as meditations have been found specifically for improving sleep as well as anxiety (27–29). The practice of laughter yoga has been effective in managing sleep disturbances in a recent study (30). Mindfulness-based meditation has been useful in reducing anxiety in various study populations (31, 32). The approach to practice of meditation has been diverse and various schools have evolved different types of meditation techniques.

Cyclic Meditation (CM) is one of the meditation techniques evolved based on the principle from the Mandukya Upanishad, one of the oldest texts in Indian wisdom (33). CM as a dynamic meditation technique is performed to master the mind, offering a pathway when thoughts overwhelm the mind. The CM practice involves cyclic stimulation through asanas and relaxation along with body awareness. Earlier studies of CM have shown significant improvement in the reduction of state anxiety and improvement in memory (34), induces a state of low physiological activation, reducing anxiety, decreasing stress, enhancing attention, and discriminative abilities, and promoting better sleep with increased slow-wave sleep (35, 36).

Numerous scientific studies have revealed that the mental well-being of sailors is at risk due to the inherently stressful and hostile environment of seafaring, which has been on the rise in recent years. Given that working and leisure time are spent in the same confined environment for prolonged periods, many stressors in seafaring can be considered chronic. Since they struggle with various mental conflicts, the practice of cyclic meditation proves beneficial in addressing these challenges. However, limited studies exist on this topic, underscoring the need for this study.

2 Materials and methods

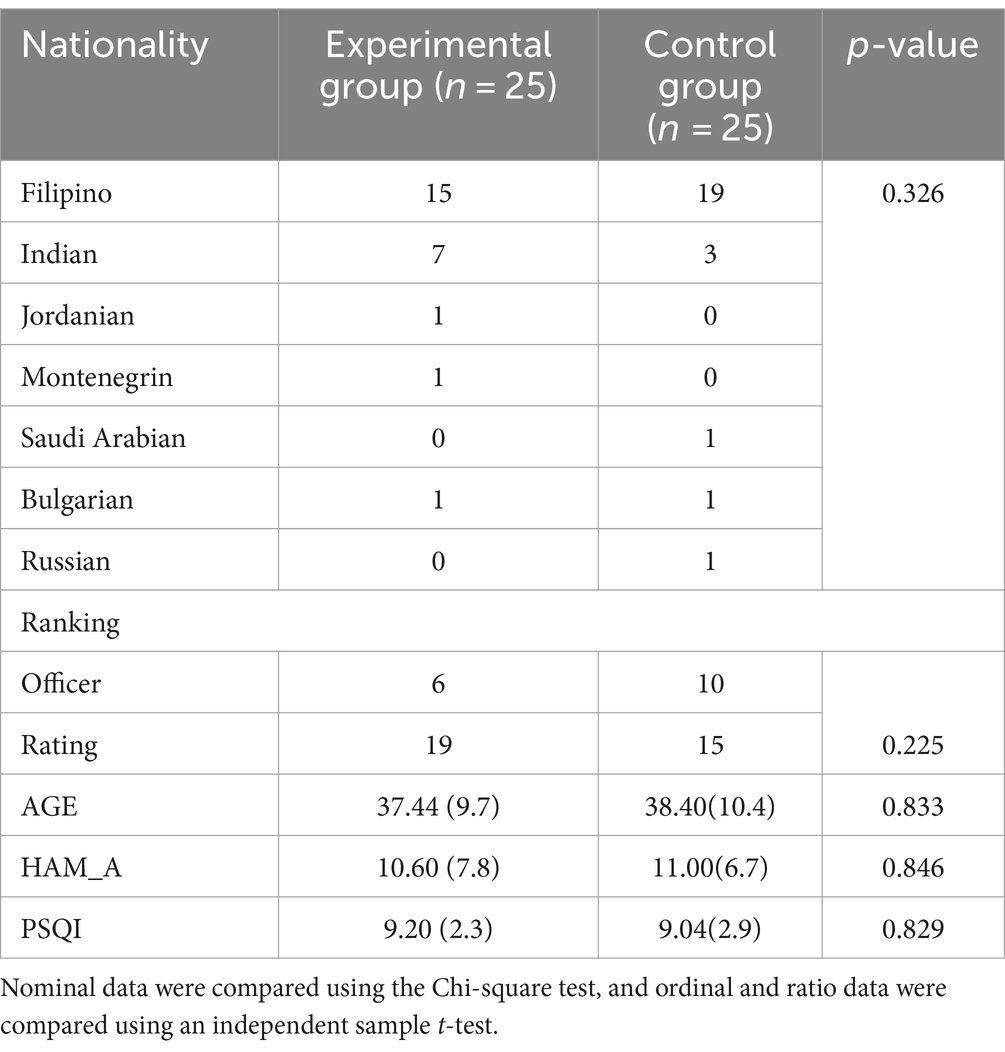

Trial Design and Participants: A matched controlled study with a quasi-experimental design comprising two groups (experimental and control) was executed. A total of 72 male navy sailors from the merchant ships of Wedyan and Aslaf were briefed about the study protocol. The inclusion criteria of the study included volunteers who scored more than 18 on the pre-HAM A scale, which is considered moderate anxiety and severe, and who scored more than 5 in pre-PSQI, which is associated with poor sleep quality. We included participants with no prior experience with any type of Yoga practice. We excluded volunteers who are under medication and have any disease like the presence of cognitive or neurological disorders, respiratory or cardiac, and sensory abnormalities. Finally, 54 male navy sailors with their mean (±SD) age 37.74 (9.79) years were recruited to the study. The demographic data is depicted in Table 1. A quasi-experimental, non-randomized, matched control group was used. The participants were matched based on their, age, gender and rank, and then assigned to experimental or control groups. Both groups are taken from different ships namely Wedyan and Aslaf.

Ethical consideration: The Institutional Ethics Committee of the University approved the study. Clearance was obtained from the authorities of merchant ships of Wedyan and Aslaf to conduct the meditation sessions on board and written informed consent was obtained from individual participants before their recruitment to the study. We have ensured voluntary participation and we considered their schedules and privacy (Figure 1).

2.1 Intervention

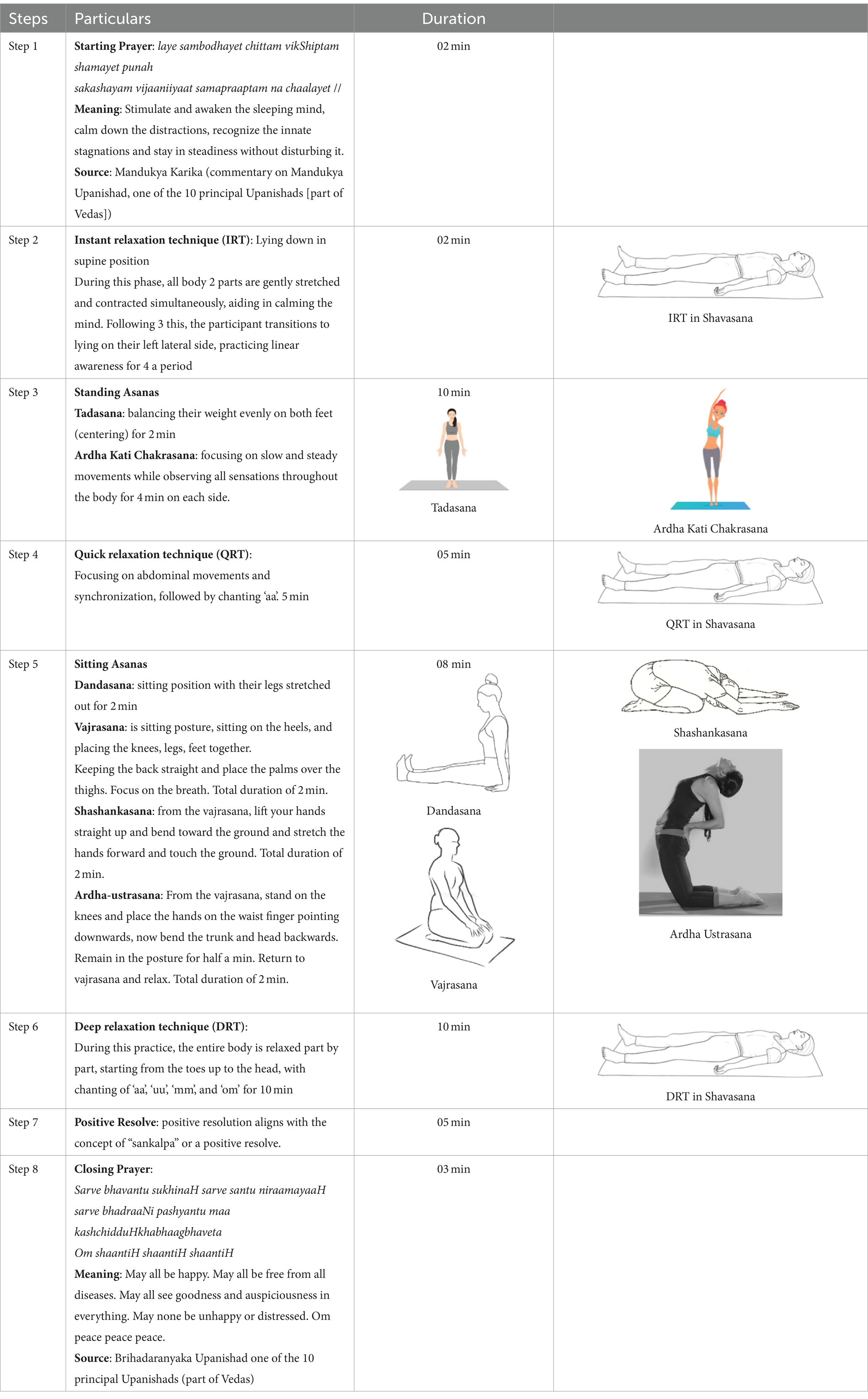

Experimental: Cyclic meditation: Throughout the practice, subjects kept their eyes closed, and followed pre-recorded instructions. The instructions emphasized carrying out the practice slowly, with awareness and relaxation. The practice began by repeating a verse (40 s) from the yoga text, the Mandukya Upanishad (33); followed by stimulation and relaxation of the body. The practice lasted for a total of 45 min, with the intervention administered continuously for 21 days, keeping a gap of 90 min following dinner, starting from 8:30 PM and concluding at 9:15 PM each evening.

Cyclic Meditation is a structured procedure that alternates between stimulation and relaxation techniques. Participants begin by starting prayer for 2 min and lying down in a supine position, where they experience instant relaxation for 2 min. During this phase, all body parts are gently stretched and contracted simultaneously, aiding in calming the mind. Following this, the participant transitions to lying on their left lateral side, practicing linear awareness for a period. Then, they stand in Tadasana, balancing their weight evenly on both feet (centering) for 2 min. Next, participants perform asanas such as Ardha Kati Chakrasana on both sides, focusing on slow and steady movements while observing all sensations throughout the body for 4 min on each side. After the asana practice, the participant returns to Shavasana. A quick relaxation technique is applied, focusing on abdominal movements and synchronization, followed by chanting ‘aa’ for 5 min. They then turn to the left lateral side and come to a sitting position with their legs stretched out for 2 min, followed by practicing Vajrasana, Ardha Ushtrasana, and Shashanka Asana, each for 2 min. The session concludes with the participant lying on their back in Shavasana for a deep relaxation technique. During this practice, the entire body is relaxed part by part, starting from the toes up to the head, with chanting of ‘aa’, ‘uu’, ‘mm’, and ‘om’ for 10 min. Afterward, a positive affirmation is repeated for 2 min, followed by a closing prayer for 3 min (37). The brief outline intervention is given in Table 2.

Waitlist Control Group: The control group participants were asked to continue their routine daily activities for the follow-up duration of 21 days. Following the 21 days, they were offered the same intervention as cyclic meditation.

Assessments: The impact of cyclic meditation was assessed using self-report measures such as the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A) for anxiety and the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) for sleep. The assessment was conducted on the first day at the same time of the day, before the intervention, for both the experimental and control groups.

HAM-A assesses the presence and degree of severity of types of anxiety symptoms to provide a patient’s status ranging from mild to severe. The scale, developed by Hamilton in 1959 the scale contains 14 entries. It uses the 5-level rating method of 0 to 4 points. The total score is 0 ∼ 56, and the anxiety level can be divided as follows: < 7 means no anxiety, 7 ∼ 14 means possible anxiety, 15 ∼ 21 means certain anxiety, 21 ∼ 29 means obvious anxiety, and > 29 means severe anxiety. Score 14 is generally the critical value. The Cronbach’s α of the Hamilton Anxiety Scale was 0.77 to 0.92 (38, 39).

PSQI which is a validated questionnaire for the assessment of sleep patterns was developed by the University of Pittsburgh. It is a self-reported questionnaire that assesses sleep quality over a 1-month time interval, and addresses 7 components, i.e., subjective sleep quality, latency, duration, efficiency, disturbance, need for medications to sleep and day dysfunction due to sleepiness, with a maximum score being 21 points. A cut-off of five was considered to identify respondents with poor sleep quality. The Cronbach’s α of the PSQI fluctuated between 0.70 and 0.85 (40, 41).

Evaluation of BP and PR: We evaluated the patient’s BP and PR using an automated Oscillometric upper-arm BP monitoring device (Omron HEM7120). The participants were seated in a quiet room at a comfortable temperature and were instructed to avoid talking during the procedure. The BP measurements were started after the participants had rested for 5 min. The participants sat on a chair with their legs uncrossed and their feet flat on the floor. All BP measurements were performed on the participant’s left arm at the level of the heart and have taken measurements at the same time. The BP and PR were recorded thrice in a single sitting and the average of the three recordings was taken to ensure reliability of the data.

Data Extraction and Analysis: The data for HAM-A and PSQI were extracted using questionnaire manuals and organized in Microsoft Excel version 2016. The BP was organized in systolic and diastolic BP and expressed as mmHg. PR was expressed in beats/min. Data analysis was performed using the JASP statistical package version 0.17.0 (42).

3 Results

A total of 54 participants took part in the study. Four participants were lost to follow-up in an experimental study, whose data were not considered for final analysis. Finally, the data of 50 participants were analyzed. The demographic data were compared using the Chi-square test, and ordinal and ratio data were compared using RM ANOVA. The demographic data is represented in Table 1.

3.1 Within-group changes

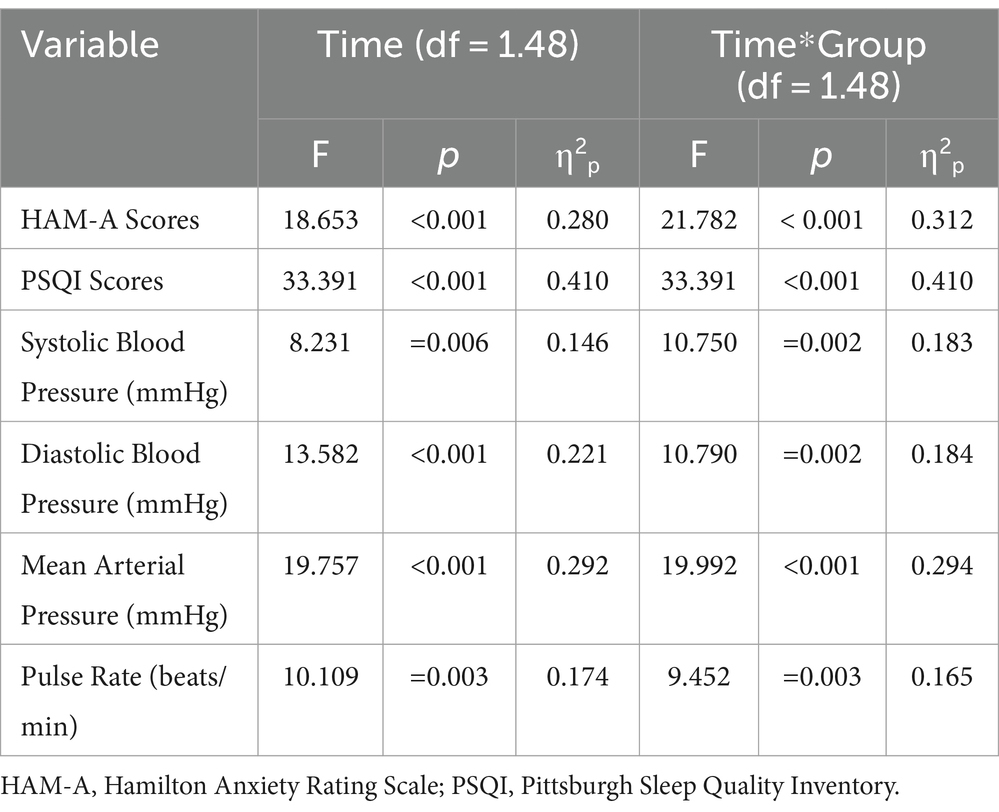

The RM ANOVA demonstrated significant within-subjects in HAM-A scores F = 18.653, p < 0.001; PSQI scores F = 33.391, p < 0.001, Systolic BP F = 8.231, p = 0.006, Diastolic BP F = 13.582, p < 0.001, Mean arterial pressure F = 19.757, p < 0.001, Pulse rate F = 10.109, p = 0.003. The within-subjects changes obtained through RM ANOVA are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Results of the repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) for within-subject effects.

3.2 Between-group changes

Pairwise comparisons between the groups performed through RM ANOVA with Holms corrections demonstrated significantly higher scores following cyclic meditation when compared with baseline for HAM-A scores, t = − 3.257, p = 0.009; PSQI scores, t = −4.682, p < 0.001; Systolic BP, t = −2.095, p = 0.041; Diastolic BP, t = −2.446, p = 0.018; Mean arterial pressure, t = 0.717, p = 0.015; Pulse rate, t = −2.037, p = 0.014. The effect sizes and t-values between groups using RM ANOVA with Holm’s correction along with the group mean and SD are reported in Table 4.

3.3 Adverse effects

Throughout the study, participants were encouraged to report any adverse effects to the investigators. Only two participants in the experimental group reported mild headaches following the practice of CM on the first day. No other adverse events were reported.

4 Discussion

The purpose of this study is to observe the impact of 21 days of Cyclic meditation intervention on sleep quality and anxiety levels in merchant navy sailors while on board the vessel. After 21 days of CM, statistically significant results are noticed in sleep quality, anxiety levels, and secondary variables of Systolic blood pressure and Diastolic Blood pressure, mean arterial pressure and pulse rate. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the effect of cyclic meditation on anxiety and sleep quality in merchant navy sailors.

The study outcomes are similar to earlier studies of cyclic meditation. Based on a polysomnographic study conducted on 30 male participants, it was observed that CM for 2 days resulted in a decrease in the number of rapid eye movements and awakenings at night (35). Additionally, the self-rating of sleep showed an increase in the feeling that sleep was refreshing and an improvement of sleep duration (43). The immediate effect of CM was assessed by using the Wechler Memory Scale, Spielberg’s State Anxiety Inventory, and Digit Span Test. The results showed that the CM participants had a heightened memory score, improved attention, and a significant reduction in anxiety (34). Another study conducted on the immediate effect of CM evaluated the performance of participants on the Six letter cancelation test, this test is known to assess selective attention and visual scanning abilities. These findings suggest that CM has a positive impact on selection attention & visual scanning abilities (44, 45).

A study involving 26 asymptomatic male managers revealed that a two-day CM (stress management) program led to a notable decrease in both occupational stress levels and baseline autonomic arousal. This reduction in sympathetic activity indicates a significant positive impact. The mechanism driving the decline in stress levels may involve both decreased autonomic arousal and psychological factors. Coccharia’s research (46) supports this by highlighting the effectiveness of yoga in managing stress among occupational workers. Several other studies indicate beneficial role of yoga practices in various occupational settings, including farmers (47), industry workers (23, 24), healthcare workers (48), computer professionals (26) etc. Consequently, employers are encouraged to incorporate yoga into their workplace wellness programs for its potential benefits in stress management (49).

According to epidemiological studies, 50% of individuals with anxiety suffer from sleep deprivation, particularly insomnia. This deprivation of sleep can lead to a negative impact on work efficiency. Work stress, which manifests as fatigue and frustration, is associated with various negative reactions, including job dissatisfaction, low organizational commitment, and a high propensity to resign. Ultimately, anxiety negatively impacts employee performance (50).

According to studies, practicing yoga has been shown to improve sleep and reduce anxiety levels (51), which in turn helps to reduce occupational stress and improve work efficiency (52, 53). Several nonpharmacological interventions that could help sleep disturbances have been in practice such as acupuncture and aromatherapy (54, 55). Our study’s results conform with these earlier findings from studies conducted in other work environments (56). However, this study is the first one conducted on board in a group of international seafarers, applying the intervention of Cyclic Meditation specifically. Our results of increased sleep quality and reduced levels of anxiety indicate better performance and could bring a safer work and living atmosphere on board.

Several limitations were encountered, as the study setting was on board the ships. The sample size was inevitably restricted, and collecting numerous samples simultaneously posed a challenge due to the crew working in shifts aboard the vessel. Also, the sample was restricted to male seaboard crew only, which limits the generalization of the results of this study. Additionally, the absence of an active control group could be considered another major limitation of the study. Longer interventions cannot be utilized as they may hamper the work rest hours onboard. More variables could have been used to make the study stronger.

5 Conclusion

The practice of 21 days of cyclic meditation led to positive changes in sleep quality and reduced anxiety in merchant navy sailors while sailing. This initial quasi-experimental study can pave the way for large-scale trials with robust designs and an active control group. Looking ahead, the long-term effects of cyclic meditation could offer valuable support in managing stressors inherent in ship life, thereby enhancing overall well-being. Additionally, there is potential to explore the impact of cyclic meditation on depression levels among sailors, offering promising avenues for future research and intervention.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BP: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NB: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The current study was supported by the Institutional Seed Money Grant by Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana (S-VYASA), Deemed to be University, Bengaluru.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Brodie, P . International chamber of shipping. In: Commercial shipping handbook. 3rd edn, Routledge. (2015).

2. Russell, DW, Markwald, RR, and Jameson, JT. Self-reported sleep and sleep deficiency: results from a large initiative of sailors attached to U.S. navy warships. J Sleep Res. (2021) 30:e13397. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13397

3. Brooks, SK, and Greenberg, N. Mental health and psychological wellbeing of maritime personnel: a systematic review. BMC Psychol. (2022) 10:139. doi: 10.1186/S40359-022-00850-4

4. Matsangas, P, and Shattuck, NL. Habitability in berthing compartments and well-being of sailors working on U.S. navy surface ships. Hum Factors. (2021) 63:462–73. doi: 10.1177/0018720820906050

5. Schmied, EA, Martin, RM, Harrison, EM, Perez, VG, and Thomsen, CJ. Studying the health and performance of shipboard sailors: an evidence map. Mil Med. (2021) 186:E512–24. doi: 10.1093/MILMED/USAA459

6. Schmied, EA, Harrison, EM, Dell’Acqua, RG, Perez, VG, Glickman, G, and Hurtado, SL. A qualitative examination of factors that influence sleep among shipboard sailors. Mil Med. (2021) 186:E160–8. doi: 10.1093/MILMED/USAA321

7. Harrison, EM, Easterling, AP, Schmied, EA, Hurtado, SL, and Glickman, GL. Chronotype and self-reported sleep, alertness, and mental health in U.S. sailors. Mil Med Res. (2021) 8:43. doi: 10.1186/S40779-021-00335-2

8. Carter, SP, and Renshaw, KD. Spousal communication during military deployments: A review. J Fam Issues. (2016) 37:2309–32. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14567956

9. Cacioppo, JT, Cacioppo, S, Adler, AB, Lester, PB, Mcgurk, D, Thomas, JL, et al. The cultural context of loneliness: risk factors in active duty soldiers. J Soc Clin Psychol. (2016) 35:865–82. doi: 10.1521/JSCP.2016.35.10.865

10. Ramchand, R, Rudavsky, R, Grant, S, Tanielian, T, and Jaycox, L. Prevalence of, risk factors for, and consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems in military populations deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2015) 17:37. doi: 10.1007/S11920-015-0575-Z

11. Kanesarajah, J, Waller, M, Zheng, WY, and Dobson, AJ. Unit cohesion, traumatic exposure and mental health of military personnel. Occup Med (Lond). (2016) 66:308–15. doi: 10.1093/OCCMED/KQW009

12. Mcandrew, LM, Markowitz, S, Lu, SE, Borders, A, Rothman, D, and Quigley, KS. Resilience during war: better unit cohesion and reductions in avoidant coping are associated with better mental health function after combat deployment. Psychol Trauma. (2017) 9:52–61. doi: 10.1037/TRA0000152

13. Pipere, A, Mārtinsone, K, Regzdiņa-Pelēķe, L, and Grišķeviča, I. Sailing across the Atlantic: an exploration of the psychological experience using arts-based research. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:572028. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572028

14. Schmied, EA, Harrison, EM, Englert, RM, Thomsen, CJ, and Glassman, LH. Challenges and opportunities to maximize mental health among shipboard sailors: A qualitative study. Mil Behav Health. (2023):1–12. doi: 10.1080/21635781.2023.2258785

15. Baker, JC, Grover, S, Gunn, LH, Charles, C, Rikli, H, Franks, MJ, et al. Group brief cognitive behavioral therapy for suicide prevention compared to dialectal behavior therapy skills group for military service members: a study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. (2023) 23:904. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-05282-x

16. Borges, GA, Tortorella, G, Rossini, M, and Portioli-Staudacher, A. Lean implementation in healthcare supply chain: a scoping review. J Health Organ Manag. (2019) 33:304–22. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-06-2018-0176

17. Tahira, S . The association between sports participation and physical fitness. Int J Sport Stud Health. (2022) 4:127001. doi: 10.5812/intjssh-127001

18. Rees, L, and Weil, A. Integrated medicine: imbues orthodox medicine with the values of complementary medicine. BMJ: British Med J. (2001) 322:119–20. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.322.7279.119

19. Madsen, C, Vaughan, M, and Koehlmoos, TP. Use of integrative medicine in the United States military health system. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2017) 2017:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2017/9529257

20. Camacho-Montaño, LR, Iranzo, A, Martínez-Piédrola, RM, Camacho-Montaño, LM, Huertas-Hoyas, E, Serrada-Tejeda, S, et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on sleep in children: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. (2022) 62:101596. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101596

21. Williams, BA . Older prisoners and the physical health effects of solitary confinement. Am J Public Health. (2016) 106:2126–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303468

22. Taheri, M, Irandoust, K, Reynoso-Sánchez, LF, Muñoz-Helú, H, Cruz-Morales, KN, Torres-Ramírez, R, et al. Effects of home confinement on physical activity, nutrition, and sleep quality during the COVID-19 outbreak in amateur and elite athletes. Front Nutr. (2023) 10:1143340. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1143340

23. Pravalika, B, Yamuna, U, and Saoji, AA. Yoga for musculoskeletal pain, discomfort, perceived stress, and quality of sleep in industry workers: a randomized controlled trial. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. (2023) 96:1349–60. doi: 10.1007/S00420-023-02013-3

24. Yamuna, U, Pravalika, B, Madle, K, Majumdar, V, and Saoji, AA. Effect of yoga in industrial workers with chronic venous insufficiency: A randomized controlled trial. J Integrative Complement Med. (2024) 96:1349–60. doi: 10.1089/jicm.2023.0691

25. Saoji, AA, Swathi, PS, Bhat, R, Bansal, B, Mohanty, S, and Raj Lakshmi, RKR. Exploring the effect of Trataka (A yogic cleansing technique) and cold eye pack on eye strain during COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized three-arm trial. J Integrative Complement Med. (2023) 30:345–51. doi: 10.1089/JICM.2023.0175

26. Swathi, PS, Saoji, AA, and Bhat, R. The role of trataka in ameliorating visual strain and promoting psychological well-being during prolonged use of digital displays: A randomized controlled trial. Work. (2022) 71:327–33. doi: 10.3233/WOR-210834

27. Rusch, HL, Rosario, M, Levison, LM, Olivera, A, Livingston, WS, Wu, T, et al. The effect of mindfulness meditation on sleep quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2019) 1445:5–16. doi: 10.1111/NYAS.13996

28. Goyal, M, Singh, S, Sibinga, EMS, Gould, NF, Rowland-Seymour, A, Sharma, R, et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. (2014) 174:357–68. doi: 10.1001/JAMAINTERNMED.2013.13018

29. Malviya, S, Saoji, AA, and Pravalika, B. Yoga nidra for mental health: A systematic review of current evidence. J Spiritual Ment Health. (2023):1–27. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2023.2290249

30. Heidari, E, Shirazi, M, and Sanaguye Moharer, GR. The effectiveness of laughter yoga training on quality of sleep and positive and negative affect of female teachers with diabetes. Applied Family Therapy J. (2023) 4:49–68. doi: 10.61838/kman.aftj.4.4.4

31. Mohammad Salehi, S, Yousefi, N, and Moradi, O. Comparing the effectiveness of Wells’ Meta-cognition training with Kabat-Zinn’s mindfulness training on academic procrastination of students with math anxiety. J Adolescent Youth Psychol Stud. (2022) 3:452–67. doi: 10.61838/kman.jayps.3.3.35

32. Heidari, M, Mirshabani, ZS, Sadegh Masjedi, A, and Mortezaei, H. The effectiveness of mindfulness group therapy based on cognition in reducing anxiety and increasing the quality of life of couples with delinquent husbands. Applied Family Therapy J. (2023) 4:291–303. doi: 10.61838/kman.aftj.4.2.18

33. Nagendra, HR, and Nagaratna, R. New perspectives in stress management (SMET). Bengaluru: Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashana (2014).

34. Subramanya, P, and Telles, S. Effect of two yoga-based relaxation techniques on memory scores and state anxiety. Biopsychosoc Med. (2009) 3:8. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-3-8

35. Patra, S, and Telles, S. Positive impact of cyclic meditation on subsequent sleep. Med Sci Monit. (2009) 15:CR375–81.

36. Patra, S, and Telles, S. Heart rate variability during sleep following the practice of cyclic meditation and supine rest. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. (2010) 35:135–40. doi: 10.1007/s10484-009-9114-1

37. Sarang, SP, and Telles, S. Changes in p300 following two yoga-based relaxation techniques. Int J Neurosci. (2006) 116:1419–30. doi: 10.1080/00207450500514193

38. Thompson, E . Hamilton rating scale for anxiety (HAM-A). Occup Med (Chic Ill). (2015) 65:601–1. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv054

39. Hamilton, M . The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. (1959) 32:50–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x

40. Mollayeva, T, Thurairajah, P, Burton, K, Mollayeva, S, Shapiro, CM, and Colantonio, A. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index as a screening tool for sleep dysfunction in clinical and non-clinical samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. (2016) 25:52–73. doi: 10.1016/J.SMRV.2015.01.009

41. Carpenter, JS, and Andrykowski, MA. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index. J Psychosom Res. (1998) 45:5–13. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00298-5

42. JASP Team . JASP version 0.14.1. (2020). Available at: https://jasp-stats.org/

43. Subramanya, P, and Telles, S. A review of the scientific studies on cyclic meditation. Int J Yoga. (2009) 2:46–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.60043

44. Sarang, SP, and Telles, S. Immediate effect of two yoga-based relaxation techniques on performance in a letter-cancellation task. Percept Mot Skills. (2007) 105:379–85. doi: 10.2466/pms.105.2.379-385

45. Subramanya, P, and Telles, S. Performance on psychomotor tasks following two yoga-based relaxation techniques. Percept Mot Skills. (2009) 109:563–76. doi: 10.2466/PMS.109.2.563-576

46. Krylov, SS, Petrov, AN, Losev, SS, Georgianova, EK, and Lychakov, AV. Behavioral effects of thyroliberin on animals of various species. Farmakol Toksikol. (1986) 49:30–3.

47. Dhansoia, V, Majumdar, V, Manjunath, N, Singh Gaharwar, U, and Singh, D. Breathing-focused yoga intervention on respiratory decline in chronically pesticide-exposed farmers: A randomized controlled trial. Front Med (Lausanne). (2022) 9. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.807612

48. Upadhyay, V, Saoji, AA, Verma, A, and Saxena, V. Development and validation of 20-min yoga module for reducing burnout among healthcare worker(s). Complement Ther Clin Pract. (2022) 46:101543. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2022.101543

49. Zhang, M, Murphy, B, Cabanilla, A, and Yidi, C. Physical relaxation for occupational stress in healthcare workers: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Occup Health. (2021) 63:e12243. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12243

50. Chen, B, Wang, L, Li, B, and Liu, W. Work stress, mental health, and employee performance. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:1006580. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1006580

51. Nalgirkar, S, Vinchurkar, S, Saoji, A, and Mohanty, S. Yoga as a therapeutic intervention in the Management of Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding: A controlled pilot study. J Midlife Health. (2018) 9:8–13. doi: 10.4103/jmh.JMH_76_17

52. Strijk, JE, Proper, KI, van Mechelen, W, and van der Beek, AJ. Effectiveness of a worksite lifestyle intervention on vitality, work engagement, productivity, and sick leave: results of a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2013) 39:66–75. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3311

53. Zheng, L-W, Chen, Y, Chen, F, Zhang, P, and Wu, L-F. Effect of acupressure on sleep quality of middle-aged and elderly patients with hypertension. Int J Nurs Sci. (2014) 1:334–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2014.10.012

54. Das, P, Mohanty, S, and Saoji, AA. Influence of acupuncture with three specific acu-points on quality of sleep in residents of an elderly nursing home in rural India: A pilot randomized placebo-controlled trial. Adv Integr Med. (2022) 9:110–4. doi: 10.1016/j.aimed.2022.02.001

55. Sun, A, and Wu, X. Efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions on improving sleep quality in depressed patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. (2023) 172:111435. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2023.111435

Keywords: yoga, shipping, occupational health, meditation, sleep, psychological health

Citation: Paranthatta S, George T, Vinaya HM, Swathi PS, Pandey M, Pradhan B, Babu N and Saoji AA (2024) Effect of cyclic meditation on anxiety and sleep quality in sailors on merchant ships—A quasi-experimental study. Front. Public Health. 12:1363750. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1363750

Edited by:

Morteza Taheri, University of Tehran, IranReviewed by:

Khadijeh Irandoust, Imam Khomeini International University, IranDavid Shannahoff-Khalsa, University of California, San Diego, United States

Mehdi Rostami, KMAN Research Institute, Canada

Copyright © 2024 Paranthatta, George, Vinaya, Swathi, Pandey, Pradhan, Babu and Saoji. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Apar Avinash Saoji, YXBhcnNhb2ppQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Sukesh Paranthatta†

Sukesh Paranthatta† H. M. Vinaya

H. M. Vinaya P. S. Swathi

P. S. Swathi Apar Avinash Saoji

Apar Avinash Saoji