94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Public Health, 12 April 2024

Sec. Aging and Public Health

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1335692

Background: Frequent social participation among older adults is associated with greater health. Although understanding how sex and gender influence social participation is important, particularly in developing sex-inclusive health promotion and preventive interventions, little is known about factors influencing engagement of older women and men in social activities.

Aim: This study thus aimed to examine factors influencing social activities of older women and men.

Methods: A mixed-method systematic review was conducted in nine electronic databases from inception to March 2023. The studies had to define social participation as activities with others and examine its influencing factors among community-dwelling older women and men. Data were analyzed using convergent synthesis design from a socio-ecological perspective.

Results: Forty-nine studies, comprising 42 quantitative, five qualitative and two mixed method design were included. Themes identified concerned: (a) sociodemographic factors, (b) personal assets, (c) interpersonal relationships and commitments, (d) physical environment, and (e) societal norms and gender expectations. The findings identified the heterogeneous needs, preferences and inequalities faced by older women and men, considerations on sociocultural expectations and norms of each gender when engaging in social activities, and the importance of having adequate and accessible social spaces. Overall, this review identified more evidence on factors influencing social participation among women than in men.

Conclusion: Special attention is needed among community care providers and healthcare professionals to co-design, implement or prescribe a combination of sex and gender-specific and neutral activities that interest both older women and men. Intersectoral collaborative actions, including public health advocates, gerontologists, policymakers, and land use planners, are needed to unify efforts to foster social inclusion by creating an age-friendly and sustainable healthy environment. More longitudinal studies are required to better understand social participation trajectories from a sex and gender perspective and identify factors influencing it.

Systematic reviews registration: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO, identifier [CRD42023392764].

Worldwide, the proportion of people aged 60 and older is expected to more than double in the next 30 years and surpass 1.5 billion by 2050 (1). Over their life course, people often lose their social roles than acquire new ones (2, 3) but, as one ages, they seek for continuity in social relationships and engagement in social activities in the community (4). Social participation has been broadly described as an individual’s involvement in activities that provide opportunities for connection with others in community life and other important shared areas (5). Changing in response to available time and resources and based on societal context and what individuals perceived as meaningful (5), social participation has steadily declined, giving rise to a new epidemic of loneliness and isolation (6). Frequent social participation among older adults contributes to greater social integration and improves health outcomes such as cardiovascular health (7–9) and cognition (10). Greater social participation also reduces the risk of social isolation, increases socioemotional support, promotes a sense of being valued (7, 11), and protects against depressive symptoms (12, 13). Given the potential benefits of social participation, a substantial body of literature and reviews have examined the associations between social participation and various health outcomes (10, 14). Studies have also examined the effectiveness of various interventions fostering social participation, including the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs), among older adults (15–18). A recent study by Alvarado Vazquez, Madureira (19) highlighted the potential of utilizing ICTs in the planning, design, and maintenance of public spaces to enhance social participation. In their chapter within the book “Aging, Technology and Health”, Bixter, Blocker (20) discussed the potential that social engagement technologies hold to alleviate the barriers to social interactions that numerous older adults encounter, including physical, cognitive, and financial obstacles. As poorer health outcomes have been found to be associated with social isolation among older adults, it is imperative to accelerate the development of interest, and building of capabilities and competencies for social prescription programs linked to community resources and fostering social participation (21, 22). Although the global benefits of social participation in old age are obvious (23, 24), differences in social participation have been found according to sex and gender (25, 26).

Usually categorized as male or female, sex refers to biological characteristics associated with physical and physiological features, while gender is socially constructed based on roles, behaviors, expressions, and identities of women, men, and gender-diverse people (27). Growing older is not the same for everyone. Across one’s lifespan, sex and gender influence social opportunities and economic means, which are linked to healthy lifestyle choices (28), including social participation. Among the several studies that have examined social participation among community-dwelling older adults, some have identified specific sex and gender differences. However, the existing literature lacks a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing the engagement in social activities between older women and men. Personal factors include health, resilience, and personality. For example, participation in social activities is more likely to be affected by poor health in older men than women (29). Furthermore, physical and social characteristics of the environment can influence social participation differently according to sex. For instance, one study using photography (30) reported that most interactions within open public spaces were segregated by sex. Moreover, differences between genders may be influenced by sociocultural factors. In Chinese culture, Confucianism is a significant social value that requires women to be responsible for the household and men to work as breadwinners (31). Older women were thus confined to primarily caring for the family and less likely to develop close relationships with friends (32).

To our knowledge, a rigorous, integrative, and comprehensive portrait of social participation in older adults specific to sex and gender and the underlying factors that influence it is still lacking. While systematic reviews have examined social participation according to age (33) and its barriers and facilitators among older adults (34, 35), knowledge specific to sex is limited. Therefore, conducting a mixed method systematic review is necessary to address this gap in the literature and comprehensively synthesize the existing evidence to inform healthcare professionals, community care providers, and policymakers on ways to improve social participation from a sex and gender perspective. This study thus aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of factors influencing social participation according to sex and gender among older adults. Such a synthesis of current knowledge represents an original contribution and may ultimately support decisions and the development of innovative policies and practices improving social participation among all older adults.

Following Pluye and Hong (36) framework using a convergent integrated approach, the review was driven by a broad question: What are the factors influencing older women and men when engaging in social participation? The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number CRD42023392764). This study adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (37) (Appendix A).

This review included studies involving older adults aged 60 and older (Table 1) who were community-dwelling or living in residential settings (38). Studies that focused on specific clinical populations were excluded (e.g., individuals with knee osteoarthritis, suicidal ideation, Alzheimer’s disease). While this review acknowledged the complexity of gender and that sex and gender have distinct meanings, a binary conceptualization had to be used where individuals were identified as male or female. This conceptualization is justified by the confusion surrounding “gender” and “sex” where the majority of the studies used these terms interchangeably and presented results according to sex only and not gender or did not fully consider the extent of gender. Studies reporting no specific sex or gender-related findings were excluded.

To distinguish social participation from parallel but different concepts, the 6-level Taxonomy of social activities (39) was used (Table 2). This review only included studies that defined social participation as activities performed with others, which refers to level three to level six of the taxonomy. These social activities can be performed with or without a common goal or benefiting others or society. Studies were thus excluded when (i) if social activities examined lacked interaction with other people, (ii) it was unclear if the studies focused on activities involving interaction with others, and (iii) focused on a single type of social activity (e.g., only volunteering, caregiving, and religious participation), which reflected too narrow participation (40). To comprehensively inform about the influence of sex and gender-specific factors on social participation among older adults, this review included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies (Table 1). Only studies that were available in full texts were included in the data synthesis of this review.

A three-step search strategy was used. An initial search limited to PubMed and Scopus was first carried out. The words in the title and abstracts of relevant articles and index terms were used to develop a full search strategy refined by a university research librarian (Appendix B). Keywords included were related to ‘older adults,’ ‘social participation,’ and ‘sex/gender differences.’ ASSIA, CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, Social Science Database, Web of Science, and ProQuest Theses and Dissertations were searched for studies published from inception to March 2023. The search was limited to ‘humans’ and ‘English language’ articles but without restrictions to publication date or geographic area. The inclusion of English publications only ensures consistency and coherence of the process by simplifying the synthesis and interpretation of data and reducing potential linguistic and translational barriers that might arise when dealing with multiple languages. Reference lists of included articles were manually searched to identify additional relevant studies.

With studies imported into EndNote Version 20 (41), two independent reviewers (OCH & PBL) screened all the titles, abstracts, and full texts of potential studies. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion, with the assistance of a third reviewer (BS).

Two reviewers used five tools to independently assess the methodological quality according to the design (OCH and PBL). Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklists (42) were used for cross-sectional, cohort, and prevalent studies, while Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (43) and Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (44) were used, respectively, for qualitative and mixed methods studies. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers. As recommended by Hong, Pluye (44), no study was excluded based on quality appraisal to consolidate all available evidence and provide insights on sex and gender differences in social participation.

The following data were extracted by OCH: studies’ characteristics (author, publication year, country, other context-related information) and other descriptive information (aim, design, sampling method, participant characteristic, the phenomenon of interest, reported findings, and text relevant to our research objective, emergent themes, authors’ conclusions). These data were recorded in an extraction form modified from the JBI manual, which was pilot tested to ensure reliability, i.e., completed by both reviewers, compared, and improved after discussion. The data extracted was independently reviewed by PBL. All disagreements were resolved through discussions between the two reviewers. Although authors of seven papers were contacted to request for missing or additional data and four of them responded, the information provided was either akin to the published data or limited and could not be used.

The use of the advanced qualitative convergent meta-integration was justified by the review question, in which identifying influencing factors predispose to include work being qualitative in nature and mixed methods studies (45). First, the studies were categorized, and mixed methods studies were fractionated into qualitative and quantitative data and evidence. Data transformation was performed to ensure that included studies were analyzed using the same synthesis method. Quantitative data and evidence were then narratively summarized, as recommended in the JBI manual (46). Next, iterative intra-method analysis and synthesis were conducted; the transformed quantitative and qualitative datasets were coded separately, with emerging findings compared. This step was followed by iterative inter-method integration; the two sets of codes were integrated and compared. Finally, ‘qualitized’ and qualitative findings were integrated using thematic synthesis (47) based on the socio-ecological model (48). This model was used to comprehensively understand the socio-ecological context that influenced social participation among older women and men across different domains, including individual, interpersonal relationships, community, and societal levels. Line-by-line inductive coding allowed the first author (OCH) to create codes, which were then deductively matched and grouped into categories to identify specific descriptive factors influencing social participation. These factors were identified and synthesized by re-examining the inferred evidence with the studies’ textual data, generating themes. Finally, the descriptive factors and themes were finalized when consensus was reached through discussions among the research team.

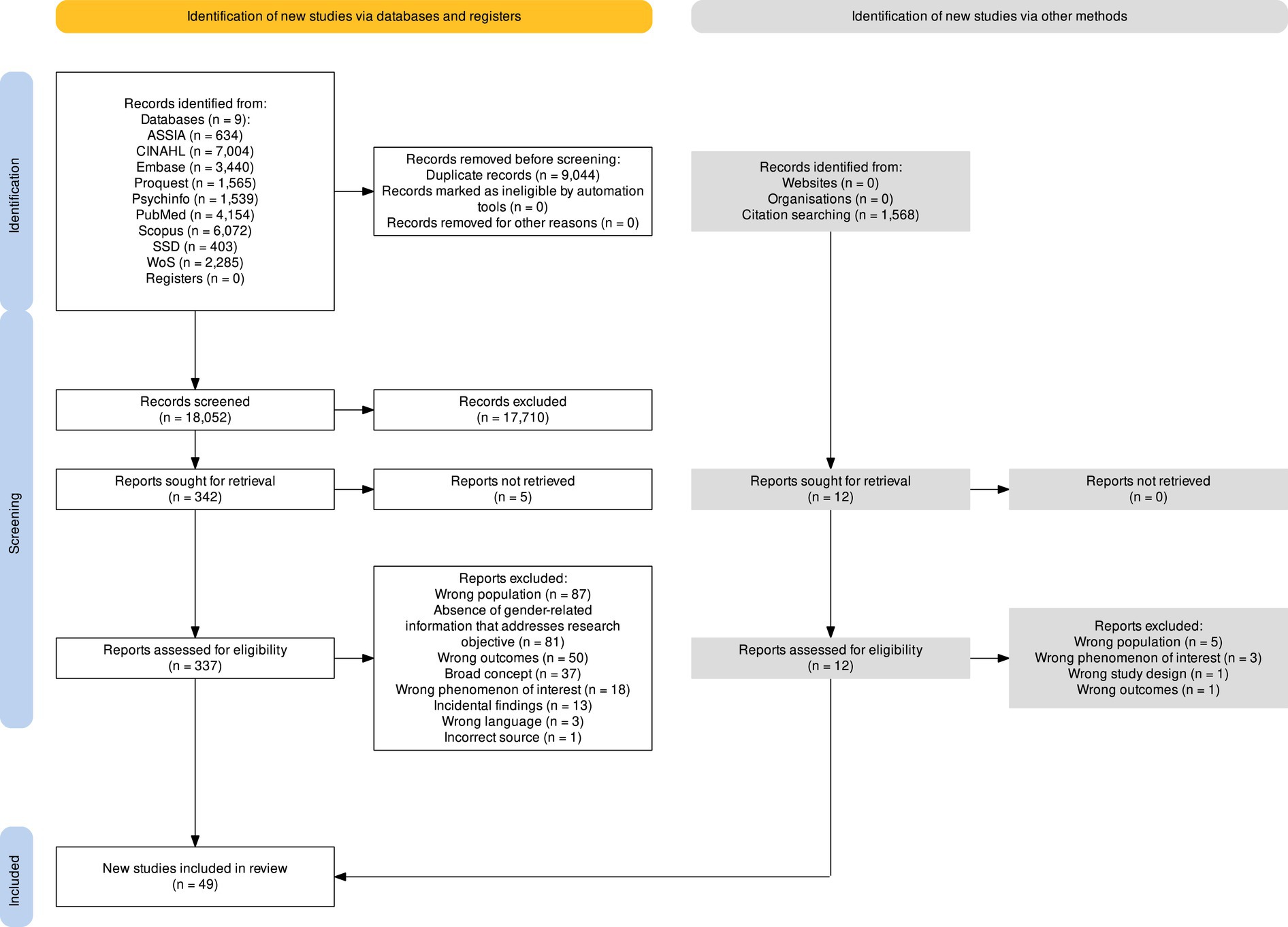

A total of 27,096 records were retrieved. After deduplication, 17,709 papers were screened for their title and abstracts and 343 full texts (Figure 1). After adding two studies from reference lists, 49 studies were subjected to quality appraisal, data extraction, and analysis.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram (59).

Twenty studies were conducted in Asian countries, 12 in North America, eight in Europe, three in South America, two in Middle Eastern, three in Australia, and one in multiple European countries (Table 3). The study designs varied: 42 were quantitative, five were qualitative, and two mixed methods. Approximately two-thirds (n = 34; 69.4%) of the studies were published within the last decade (2012–2023).

In most quantitative studies, social participation was measured either dichotomously, i.e., engaged in social activity (yes/no), or with the frequency of social engagement (Table 3). Across the included studies, variability in the definitions, understandings, and measurements of social participation was observed. Only 19.0% (n = 8) of quantitative studies used a standardized measure of social participation such as the Older Adult Activity Inventory Questionnaire (49), Participation and Activity Limitation Survey (50), or 15-item short form of the Australian Community Participation Questionnaire (51). About one quarter (n = 13; 26.5%) of the quantitative studies were longitudinal, followed by 57.1% (n = 28) cross-sectional, and one prevalent (Table 3). For quantitative and mixed methods studies, the sample sizes ranged from 132 to 31,428, while it was from 18 to 89 for qualitative.

Most studies had a clear aim, and the analyses and interpretations of findings were generally appropriate (Appendix C). The main methodological issue was potential measurement bias secondary to variations in social participation questionnaires used in quantitative studies, mostly relying on self-answered or assisted questionnaires.

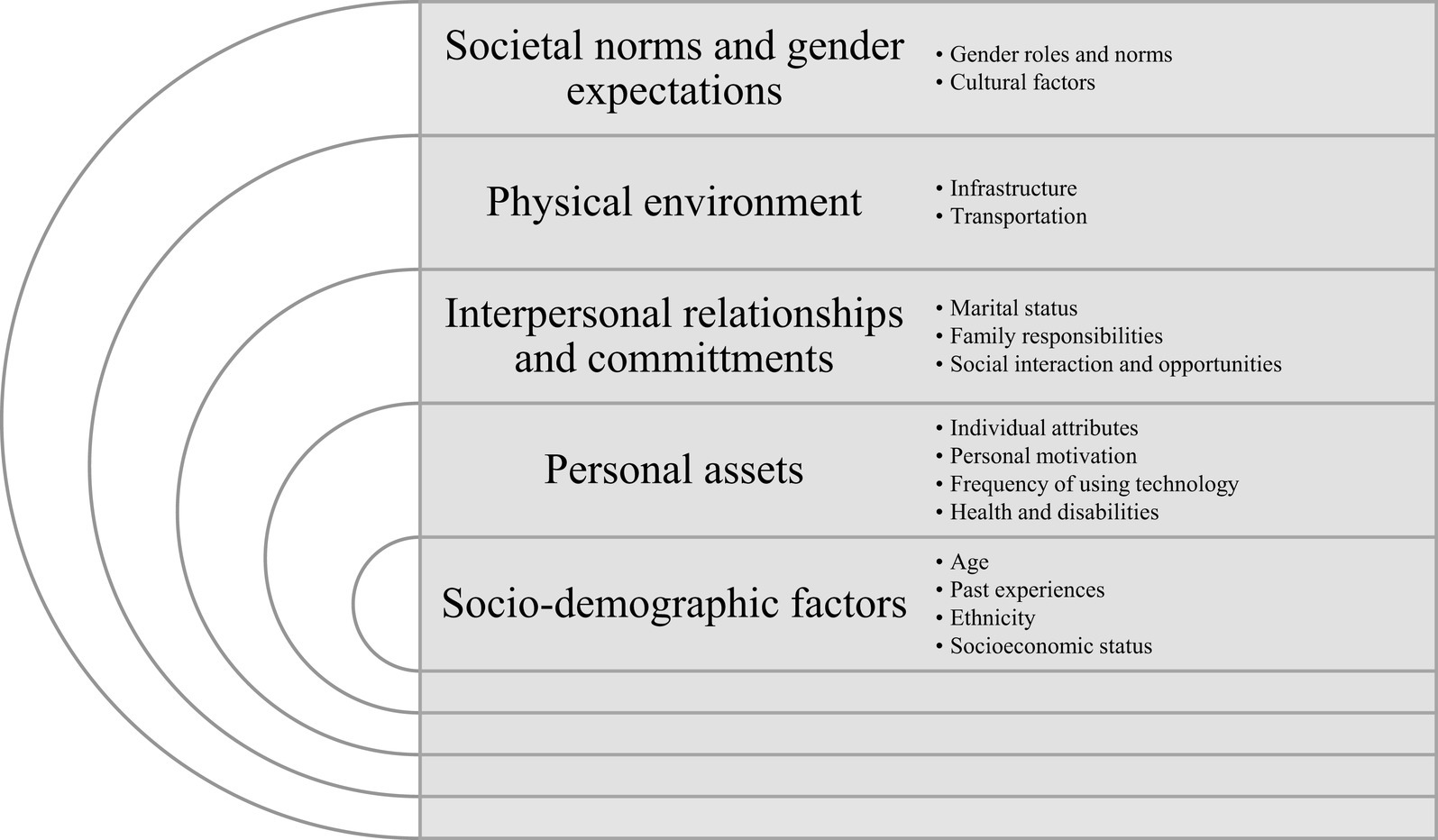

Individual and environmental factors influencing the social participation of older women and men were categorized in the following themes: (a) sociodemographic factors, (b) personal assets, (c) interpersonal relationships and commitments, (d) physical environment, and (e) societal norms and gender expectations (Figure 2). Overall, this review identified more evidence of factors influencing social participation among women than in men.

Figure 2. Summary of themes and descriptive factors influencing social participation among older men and women adults from socio-ecological perspective.

At an individual level, sociodemographic factors, including age, past experiences, ethnicity, and socio-economic status shaped social participation among older women and men. Among women compared to men, advanced age and higher socio-economic status (SES) were found to have a greater influence, respectively negative and positive.

Social participation was found to decrease as both women and men get older (52, 53). Advanced age was reported as having a greater negative influence on women’s social participation (54, 55). Sex difference in social participation seemed to however disappear after 80 years old (56, 57). Participation in recreational activities was more frequent (OR = 0.42–0.45; p < 0.05) among both sexes from the 65–74 years old group compared to those 75 years and above (53) while receiving visitors at home increased during the ages from 75 to 80 (58).

Earlier in their lives, women generally had more experience with primary relationships, e.g., with family and friends, and personal and intimate relations. Contrarily, men presented more secondary relationships, e.g., with people from the wider community, or participated in activities organized around narrower ranges of interests (60). Older women and men who engaged weekly in at least two of these social activities (visiting others, having visitors at home, participating in external social activities) earlier in their lives were more likely to have higher social participation in later years (58).

Ethnicity also had a differential effect on the social participation of older women and men (61–63). Among certain ethnic groups, i.e., Tamil and Sinhala, men had greater access to social activities than women (63). Social activities that older women and men engaged in also differed across ethnic groups. For example, compared to women, Chinese men participated less frequently in religious services but similarly in sports, while Malay and Indian men had higher participation in both activities (62).

According to 14 studies, higher SES, specifically education level (64, 65), employment (53, 61), and financial status (52, 54, 66–73) positively influenced the ability to participate and access to social activities of older women and men. Generally, women had nevertheless lower SES and fewer resources than men (66). Thus, having higher financial support (74) and education level (54) greatly increased social participation among women more than men.

The second theme provides valuable insights into the unique personal qualities and resources, comprising individual attributes, personal motivation, frequency of using technology, as well as health and disabilities, that influence social participation among older women and men. Particularly, the use of technology for health matters and having good health had a positive influence on the social participation of both women and men.

For both older women and men, individual attributes such as open-mindedness (70), satisfaction with life (75), orientation towards high social contribution (53), and a strong sense of community belonging (76) were found to be associated with greater social participation. The association between community belonging and social participation varied as a function of resilience, especially in men. Greater community belonging further enhanced social participation, especially among women (p = 0.03) and men (p < 0.01) with greater resilience (moderator effect).

Women and men reported similar motivations to engage in social activities such as coping with social isolation, reducing boredom and loneliness, keeping body and mind active, learning new things, and eating food (70, 77). Lack of interest and preference to be alone were reasons for not participating in social activities among both sexes (70). Participating in numerous interpersonal activities was found to predict increased Ikigai (sense of purpose), which was in turn found to be associated with greater motivation for new interactions with others among women (78). This association was not moderated by physical function (78). Men reported being too busy to participate more frequently than women did (79). While women focused on healthy eating (73), religious activities (70), and altruism through exchanging reciprocal aids, sharing values, and gaining emotional support (70, 80), men tend to emphasize maintaining an active lifestyle and engaging in meaningful activities (70, 73). Interestingly, experiencing positive emotions has been found to have a stronger influence on men’s social participation than on women (61).

Only one study examined the influence of Information Communication and Technology (ICT) usage and access on social participation (81). Having ICT access at any place and knowing how to use a computer increased social participation among women but not men. Using ICT for health matters increased family or friends visits among men and attendance for clubs, classes, and volunteering among women. ICT use for personal tasks was associated with decreased religious participation in both sexes.

Good health was shown to have a positive influence on participation in social activities among both sexes (70, 72, 79, 82). Strong associations were observed between chronic diseases and social participation, through activity limitation (83). Older women and men who maintained high cognitive functioning reported greater participation in social activities (80, 84). Experiencing fewer depressive symptoms among women was found to be a ‘pre-requisite’ to participating in both collective and productive social activities (84). The results on the influence of good physical function on social participation according to sex were mixed. Functional disability and physical deterioration affected women’s social participation more in some studies (85, 86) while affecting men more according to others (61, 87).

The third theme describes factors relating to interpersonal relationships and commitments, including marital status, family responsibilities, and social interactions and opportunities, which collectively influence social participation among older women and men. Having a larger social network generally increases the uptake of social activities while greater caregiving responsibilities reduce social participation among women and men. Specifically, marriage had a greater positive influence on men.

Older adults having a spouse reported greater abilities to engage in social activities independently compared to those without, but this positive influence was found to be lower in women than men (54). Married men tend to engage in more relationships (53, 88) and have more frequent and positive social participation (54, 68, 81). As they were expected to care for their partner’s needs, being married reduced women’s social participation (57), which can be explained by men’s reliance on their spouse for intimacy, emotional, instrumental, and caregiving support (67, 87). Conversely, widowed women were found to have a higher social participation. Despite the loss of their spouse, widows described positive aspects of being single, such as having personal freedom and not having to look after a partner (77). The importance of friendships during widowhood was salient; friends provided emotional support, encouragement to get outside, and fulfilled the desire to be with others. In addition, widowers typically reported having smaller friendship networks and, consequently, are at greater risk of social isolation than widows (89). Nonetheless and over time, widowhood positively influenced social participation more among men than in women (66). Widowers were more likely to participate in clubs or organizations, voluntary work, veteran groups, or conservation work compared to widows (66, 77, 89). Widowers were also found to be more likely to establish new intimate relationships, providing an important source of social contact and intimacy, which further emphasized men’s heavy reliance on support from women (77).

Caregiving responsibilities, which are a competing priority among women compared to men, influence social participation. These responsibilities stemmed from the multifaceted demands placed upon women, encompassing responsibilities such as childcare, eldercare, and household management (80, 90). As the primary provider of family income, men were more involved in social activities (64). Meanwhile, married women staying at home with their children (65, 68) had restricted social participation due to their caregiving responsibilities (55, 65, 72, 76, 91–93). These caregiving duties often required a substantial time commitment and emotional investment, potentially limiting the availability and energy that women could allocate to social activities beyond their caregiving responsibilities. Once they were no longer caregivers, older women reported being able to form new social relationships and combat loneliness (57).

Social support is essential for the social participation of both women and men (68, 84), particularly emotional support (74). Men have been found to view social activities as opportunities to connect with others, expand their social networks, and foster new relationships (70). For both sexes, a larger network increases the probability of being introduced to various social groups, thus facilitating active social engagement (53). Women valued developing close interpersonal bonds, emphasizing the significance of cultivating strong relationships with others in their social networks (78). Notably, men who perceived themselves as having a greater number of reliable relationships tend to exhibit greater social participation (88). Positive social participation of men remains unaffected in the presence of conflicted relations (88). In this context, men displayed resilience to negative emotions and interactions and continued to actively participate in social activities.

Social network plays a significant role in influencing social participation, with both women and men acknowledging the importance of intergenerational contact for healthy aging (73). Men seemed to benefit mostly from socially active networks, while women relied on diverse networks (67). Women tend to engage more in social activities within the friends and community domains, whereas men primarily focused on immediate household interactions (53, 81, 82). Married women with limited social networks tend to exhibit restricted social participation (67).

By shaping an individual’s social interactions and networks, living arrangements also play a role in social participation. For instance, women living only with their spouses might experience a decrease in social activities, while those living with married children might witness a decline in childcare-centered activities (54, 65, 68). Unlike women, men living alone were less likely to be involved in any social group (53). The type of interactions and living arrangements thus influence social participation for both women and men.

The fourth theme presents the crucial contributions of the physical environment in determining access to community spaces, namely infrastructure and transportation, which influence social participation among older women and men. Proximity to services and facilities as well as transportation were found to play an important role in facilitating women’s social participation.

Compared to men, women relied more on proximity services (94) and were more affected by living environments such as safety in the neighborhood, infrastructure development, and the presence of culturally restrictive norms or practices (54, 60, 65, 70) that might impact their ability to participate in social activities. Only one study reported greater perceived proximity to neighborhood resources enhanced social participation among women and men, but only in men with minor or no disability, i.e., not when having moderate to severe disabilities (95). Additionally, women were more likely to be satisfied with services from community organizations (60); while older men expressed the lack of specific social opportunities for themself after retirement: “there are a lot more opportunities and things for women… men have other interests.” (73). Although restricted social participation was observed among older adults from rural areas (73), men living in small towns were found to have greater social functioning than those in major metropolitan areas (52, 61). Moreover, men who have been long-time residents of their local community were more inclined to participate in formal social activities compared to other men with shorter duration of residence (53).

Not having a car or driving license, driving cessation and transportation problems restrict social participation among both women and men (73, 83, 94). The cessation or limitation in driving decreased mobility independence for older adults, as they had to rely on family members for assistance with transportation to events, appointments, and errands (77). The unreliability and inconvenience of taking public transport, as well as transportation challenges faced by individuals with disabilities, were reported by women and men (70). Compared to their younger counterparts, women older than 85 were more affected by transportation problems (71). Meanwhile, older men in urban centers reported transportation problems more often than rural ones (79).

This last theme unveils how gender roles and norms, as well as culture, have an influence on the beliefs, societal views, and expectations of how women and men ought to behave and fulfill social roles which in turn influenced their social participation. Men were often viewed as the breadwinner while women as the caregiver which greatly influenced the frequency and type of social activities that they engaged in.

Traditional gender expectations in Asia assign men the role of the primary breadwinners, while women are often expected to be the primary caregivers within the household (86, 96, 97). This societal context influences men’s motivation and opportunities for social participation. Men who had the opportunity to tap into their abilities by taking leadership and organizational roles within friendship or alumni organizations (80, 98) might acquire greater motivation to engage in such activities (90). As they continued to maintain their roles as breadwinners, which enhanced their sense of belonging to society, and contributed to life satisfaction, paid work played a significant role in fostering men’s social participation (97). Men’s engagement in social activities was often linked to their primary role of providing family income (64), leading to high participation in social groups related to occupation, paid labor, and politics (56, 91, 97). Additionally, men who endorsed the traditional masculinity ideology seemed more satisfied with their social participation (88).

In contrast to men, women faced traditional gender role expectations that assign them additional responsibilities within the home, including housework and childcare (54). Compounded by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, these expectations increased the challenge for women to continue participating socially (93). In many cultures, women primarily took care of the family, while men undertook activities such as purchasing and social communication on behalf of the family (91). Women tend to engage in milder intensity social activities closer to the family and neighborhood nucleus (85), prioritizing family commitments and cultural activities as their primary means of being socially active (91, 93). Compared to men, women also presented a higher likelihood of participating in weekly religious group activities (55, 57, 97) and engaging in socializing with family or friends (70, 82). The social engagement of older women was often influenced by gender norms and societal expectations, which shaped the type of activities they participate in and the frequency of their engagement.

Culture also influences social participation according to gender among older adults, as observed in various societies (55). In countries where patriarchal values are strong, such as Japan and China, men often sought meaning and identity through their valued roles in the workplace (99). Engaging in citizenship activities, which aligned with cultural notions of manhood, led to greater life satisfaction among men (98). While, in societies, such as Korea, where the family holds a central role, women assumed substantial caregiving and family responsibilities in late life, which, as mentioned, limited their opportunities for social participation (100). Additionally, cultural practices related to religion also shaped gender disparities in social activities (92). For instance, in Malay communities where Islam was practiced, differences between women and men were observed in rates of attendance at religious services due to religious expectations (62). These cultural variations provided insights into gender differences observed in the participation in specific social activities among older adults.

This review offered a comprehensive socio-ecological perspective of how sex and gender play a role in social participation among older women and men. The findings identified how individual socio-demographic factors, personal assets, interpersonal relationships and commitments, access and adequacy of physical environment, societal norms and gender expectations influence the participation in social activities of older women and men. The consolidation of these evidence specific to each gender is unique and a key contribution to the existing literature. The findings of this review are salient in understanding how socially isolated older women and men can be approached to encourage and facilitate participation in social activities, mitigate loneliness, and cultivate habitual change in their social interactions. The factors identified in this review are discussed alongside practical implications for community practice and research.

The findings of the present study revealed that, compared to men, older women tend to have lower SES and financial resources to engage in social activities, which can lead to a higher risk of being under constrained circumstances and less inclined to participate socially. Advanced age also has a greater influence on women’s social involvement compared to men. This phenomenon can be attributed to the gender-health paradox, which posits that despite having a longer lifespan, women encounter a higher prevalence of chronic degenerative conditions that can limit their ability to participate in social activities (101). Additionally, because of their inclination toward intimate social connections, women are more susceptible to distress when someone they are emotionally close to, e.g., an immediate family member, close friend, or relative, undergoes stressful life events (102). Greater support might thus be necessary to assist older women experiencing depressive symptoms in discovering suitable social activities and increasing their motivation to participate purposefully. Consequently, participating in social activities might be more challenging for older women, as they may need to prioritize meeting the needs of other members within their social networks (103). Nevertheless, this does not imply that men consistently enjoy better health, higher SES, and greater social participation.

Sex differences in social participation were found to diminish after the age of 80, possibly as a result of reduced engagement in social activities and a shrinking social network. Pinto and Neri (33) noted that older men tend to withdraw from political and organizational activities, while women had a similar pattern for recreational, health-related, and informal social activities. As individuals age, their needs are found to become more diverse and complex, and their perspective of time and space shifts towards deeper matters such as existence and spirituality (104). Consequently, some social participation activities may have a lower priority for them in later life (105). This transcendent perspective may be influenced by an age-related health decline and increased risk of social isolation due to shrinking social networks (106, 107).

The present findings suggested that community care providers need to pay attention to older adults who are physically, socially, or economically disadvantaged, especially women, when planning and implementing community-based programs. While health or community care providers can refer these older adults to relevant social programs such as peer support groups and befriending, administrative processes of such referral services can be reviewed and simplified when possible, especially to alleviate inconveniences for individuals with fewer resources. Co-design and co-production of social and physical activities is an innovative and person-centered approach that can be used by community care providers to empower socially frail older adults, establish trust and relations, and develop sustainable solutions to engage them (108). Alternatively, regular surveys and focus groups can be conducted to gather feedback and better understand the evolving needs and preferences of specific sex, age, or other target groups of older adults. Additionally, leveraging ICT platforms such as videoconferencing (17) or customized innovative solutions such as virtual spaces (109) can provide a means to engage frail older women in the comfort of their homes. Since the association between social participation and health is bidirectional, active social engagement can also influence health, for example, by motivating a healthier lifestyle (110). More longitudinal studies considering the sex and gender perspective are also needed. Finally, policymakers should further play a critical role in allocating resources and funding to facilitate the implementation of effective social welfare programs that not only fulfill the basic needs of socially frail older adults but also cushion them from economic barriers and facilitate opportunities for social participation.

Interestingly, the present findings indicated that marriage offers men opportunities for companionship and social interactions with their spouse and others, resulting in increased social participation (111). For women, however, because they prioritize attending to the needs of their spouses and caregiving responsibilities, marriage tends to have the opposite effect. Consistent with the MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging, the findings of the present review supported that men primarily relied on their spouses for psychosocial support, whereas women are more supported by friends, relatives, and children (112). These findings are aligned with the socioemotional selectivity theory (113), which suggests that companionship becomes an increasingly essential motivator in later life. Given the differences in how marital status and social networks play a role in the socialization of older women and men, healthcare providers involved in social prescription and community care providers should consider the older adult’s familial interactions and commitments, and leverage these established connections to stimulate social participation. Other than organizing activities exclusively tailored for older adults, senior activity centers can collaborate with local community organizations and relevant agencies to plan purposeful community events or intergenerational activities that involve older adults’ existing social network, such as spouses, other family members, and friends. Older adults should also be given opportunities to volunteer with children and youth, as well as mentoring programs to facilitate meaningful relationships across different age groups and foster generativity and connection between generations (114). Future qualitative research should explore the perspectives and experiences of older couples to understand the contributory role of marriage and companionship in social participation. By exploring these elements, researchers will gain valuable insights and understanding about the dynamics of marital and familial relationships and their impact on older adults’ social engagement.

Like past reviews (40, 115, 116), the present findings demonstrated that the availability, accessibility, and appeal of social spaces can significantly impact opportunities for social engagement among older adults. Yet, this review added that women were more likely to be limited by obstacles of the built environment, such as neighborhood safety, services provided in spatial proximity, and lack of accessibility to transport services, e.g., not possessing a driving license. The present findings suggested that increased outreach efforts, as well as ground up community initiatives, are needed to foster social participation among older women in neighborhoods with limited social amenities. On the other side, men were found to be less satisfied with social opportunities and lacked appeal towards these activities and programs available in community organizations. Firstly, this might be due to perceived gender norms toward certain organized social activities, e.g., flower arrangement and cooking that are perceived as feminized or domestic activities. Secondly, perceived gender norms regarding men upholding stereotypical masculinity of being hyper-independent, strong, and stoic individuals and women easily affiliating with close interpersonal relationships in social settings might make the participation in organized social activities more socially appealing and appropriate for women. Community organizations serving older adults need to rethink and provide a combination of sex-specific and neutral activities that interest both older women and men. The present findings also reiterated the importance of considering proximity as well as ease of access and travel to community spaces during land use planning at the municipality level. This consideration requires dialogue and multisectoral collaboration among public health advocates, gerontologists, policymakers, and land use planners to implement experimental and structural interventions within neighborhoods to create an age-friendly and sustainable environment (115).

The present findings accentuated the sociocultural perceptions that femininity and masculinity affect the type of activity in which older adults participate. The social role theory posits cultural norms and expectations regarding gender roles that shape individuals’ behavior and adherence to these societal beliefs (117). Men’s social engagement often revolves around work and tends to decrease after retirement, while women’s social engagement tends to be more centered around family and continues even after retirement (118). This can be attributed to men associating their self-identity with work and occupational status, while women priorities relationships as integral to their identity (117). Often, men are perceived as the family breadwinners and women as caregivers (119). Such gender norms thus prevent most men from assuming equal caregiving responsibilities at home. As men retire, formal social participation becomes crucial in filling the vacated roles and preserving the continuity of social relationships (120). For women who have been homemakers, religious activities can offer non-material support and a sense of belonging (120). Given that men often derive their self-identity and contributory role from their occupations, having to replace, recreate, or maintain sources of meaning acquired from work life is crucial while transiting to and during retirement (121). The present findings suggested that healthcare providers involved in social prescription and community care providers attending to older men should guide conversations in exploring activities that are perceived personally valuable and acknowledged by others, as well as those that seek to reestablish a sense of being part of a social group (121). By facilitating open dialogues with both older women and men on their preferences, aspirations, personal strengths, and past experiences of social participation, healthcare providers and community care providers can also enhance their self-awareness, receptivity, and empathy, thereby fostering a more sex and gender-inclusive and accepting community. From a broader perspective, with increasing economic participation among women and dual-career households, perceptions towards sociocultural norms and roles of women and men among future cohorts of older adults may represent more openness and gender neutrality. Nonetheless, more longitudinal studies are needed to verify if differences in social participation are attributable to gender or individual differences, especially among future cohorts of older adults.

Finally, this review revealed a need to identify more factors that influence men’s social participation than women. Although the specific nature of these findings — limited evidence on factors influencing social participation among older men remains to be confirmed, it is important to promote and facilitate men’s engagement in social activities, as they generally present smaller social networks, and consequently being more at risk of social isolation (122–124). To ensure that community programs are accessible and appealing to all, it is crucial for healthcare providers involved in social prescription and community care providers to acknowledge and address men’s unique needs and preferences.

This review’s main strength is the integration of diverse study designs which comprehensively addresses the review question. As such, the findings can inform relevant community care providers regarding the development and implementation of social programs and activities from a gender perspective. This review also included studies that were conducted across countries with differing cultural and social contexts, though the majority of them were from Asia. Nonetheless, cultural or cross-geographic differences pertaining to the influencing factors of social participation among older women and men were not observed in this review. This might be attributed to the inherent heterogeneity in cultural, social, and healthcare contexts between regions, such as European and Asian countries. Alternatively, our choice of data analysis approach involves integrating data from the included studies which amalgamates findings across diverse geographical regions and cultural contexts, and this might have limited direct cultural or cross-geographical comparisons.

Due to unavailable literature on gender, one key limitation of this review is the lack of inclusion of older adults with alternate sexual orientation and gender identity, such as the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community. None of the studies make the distinction between sex and gender, making the understanding blurred. Also, it was more difficult to compare qualitative results by sex as differences relied on a small sample and might be due to personal preferences. Studies not available in full texts or published in non-English languages were excluded, so potential studies may have been missed (125). Furthermore, variability in how social participation was measured across studies had influenced the result of the current review; Only 19% (n = 8) of studies used standardized measures of social participation. Although some studies combined standardized measures and unvalidated measures, most studies developed their method of measuring participation based on a combination of frequency of attendance, social network size, or descriptive interviews. Restricted use of social participation definitions and associated measures may limit the generalizability of the findings of the present study and challenge the development of clear guidelines for policymakers, practitioners, or researchers.

This systematic review synthesized the findings on the available evidence of factors influencing the social participation of older women and men using the socio-ecological health lens. The findings highlighted the importance of considering the heterogeneous needs, preferences, and inequalities faced by older women and men, as well as recognizing societal norms and expectations surrounding gender when planning and implementing programs and creating adequate and accessible social spaces. Special attention is needed among community care providers and healthcare professionals to co-design, implement, and prescribe a combination of sex and gender-specific and neutral activities that interest both older women and men. Intersectoral collaborative efforts, including public health advocates, gerontologists, policymakers, and land use planners are needed to unify efforts to foster social inclusivity by creating an age-friendly and sustainable physical and social environment. More longitudinal studies are required to better understand social participation trajectories from a sex and gender perspective and identify factors influencing it.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

OCH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PBL: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ML: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. GRT: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. BS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the publication of this article. This research was funded by the Alice Lee Centre for Nursing Studies, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. At the time of the study, Professor Levasseur was a Fonds de la recherche du Québec Santé (FRQS) Senior Researcher (#298996; 2021–2025). She holds a Tier 1 Canadian Research Chair in Social Participation and Connection for Older Adults (CRC-2022-00331; 2023–2030).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1335692/full#supplementary-material

1. United Nations DoEaSA, Population division. World population ageing 2019: Highlights. United Nations (ST/ESA/SER.A/444).

2. Evandrou, M, and Glaser, K. Family, work and quality of life: changing economic and social roles through the lifecourse. Ageing Soc. (2004) 24:771–91. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X04002545

3. Lee, C, and Powers, JR. Number of social roles, health, and well-being in three generations of Australian women. Int J Behav Med. (2002) 9:195–215. doi: 10.1207/S15327558IJBM0903_03

4. Atchley, RC. A continuity theory of normal aging. Gerontologist. (1989) 29:183–90. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.2.183

5. Levasseur, M, Lussier-Therrien, M, Biron, ML, Raymond, E, Castonguay, J, Naud, D, et al. Scoping study of definitions of social participation: update and co-construction of an interdisciplinary consensual definition. Age Ageing. (2022) 51:1–13. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afab215

6. Office of the U.S. Surgeon General. Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation: the U.S. surgeon General’s advisory on the healing effects of social connection and community. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services. (2023).

7. Adams, KB, Leibbrandt, S, and Moon, H. A critical review of the literature on social and leisure activity and wellbeing in later life. Ageing Soc. (2011) 31:683–712. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X10001091

8. Luoh, M-C, and Herzog, AR. Individual consequences of volunteer and paid work in old age: health and mortality. J Health Soc Behav. (2002) 43:490–509. doi: 10.2307/3090239

9. Harris, AHS, and Thoresen, CE. Volunteering is associated with delayed mortality in older people: analysis of the longitudinal study of aging. J Health Psychol. (2005) 10:739–52. doi: 10.1177/1359105305057310

10. Kelly, ME, Duff, H, Kelly, S, McHugh Power, JE, Brennan, S, Lawlor, BA, et al. The impact of social activities, social networks, social support and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review. Syst Rev. (2017) 6:259. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0632-2

11. Thomas, PA. Trajectories of social engagement and limitations in late life. J Health Soc Behav. (2011) 52:430–43. doi: 10.1177/0022146511411922

12. Cruwys, T, Dingle, GA, Haslam, C, Haslam, SA, Jetten, J, and Morton, TA. Social group memberships protect against future depression, alleviate depression symptoms and prevent depression relapse. Soc Sci Med. (2013) 98:179–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.013

13. Li, C, Jiang, S, Li, N, and Zhang, Q. Influence of social participation on life satisfaction and depression among Chinese elderly: social support as a mediator. J Community Psychol. (2018) 46:345–55. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21944

14. Wanchai, A, and Phrompayak, D. Social participation types and benefits on health outcomes for elder people: a systematic review. Ageing Int. (2019) 44:223–33. doi: 10.1007/s12126-018-9338-6

15. Zagic, D, Wuthrich, VM, Rapee, RM, and Wolters, N. Interventions to improve social connections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2022) 57:885–906. doi: 10.1007/s00127-021-02191-w

16. Benoit-Dubé, L, Jean, EK, Aguilar, MA, Zuniga, A-M, Bier, N, Couture, M, et al. What facilitates the acceptance of technology to promote social participation in later life? A systematic review. Disability and rehabilitation. Assist Technol. (2020) 18:274–84. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2020.1844320

17. Heins, P, Boots, LMM, Koh, WQ, Neven, A, Verhey, FRJ, and de Vugt, ME. The effects of technological interventions on social participation of community-dwelling older adults with and without dementia: a systematic review. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:2308. doi: 10.3390/jcm10112308

18. Todd, E, Bidstrup, B, and Mutch, A. Using information and communication technology learnings to alleviate social isolation for older people during periods of mandated isolation: a review. Australas J Ageing. (2022) 41:e227–39. doi: 10.1111/ajag.13041

19. Alvarado Vazquez, S, Madureira, AM, Ostermann, FO, and Pfeffer, K. The use of ICTs to support social participation in the planning, design and maintenance of public spaces in Latin America. ISPRS Int J Geoinf. (2023) 12:237. doi: 10.3390/ijgi12060237

20. Bixter, MT, Blocker, KA, and Rogers, WA. Enhancing social engagement of older adults through technology In: R Pak and AC McLaughlin, editors. Aging, technology and health. San Diego: Academic Press (2018). 179–214.

21. Grover, S, Sandhu, P, Nijjar, GS, Percival, A, Chudyk, AM, Liang, J, et al. Older adults and social prescribing experience, outcomes, and processes: a meta-aggregation systematic review. Public Health. (2023) 218:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2023.02.016

22. Paquet, C, Whitehead, J, Shah, R, Adams, AM, Dooley, D, Spreng, RN, et al. Social prescription interventions addressing social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Meta-review integrating on-the-ground resources. J Med Internet Res. (2023) 25:e40213. doi: 10.2196/40213

23. Maier, H, and Klumb, PL. Social participation and survival at older ages: is the effect driven by activity content or context? Eur J Ageing. (2005) 2:31–9. doi: 10.1007/s10433-005-0018-5

24. Marhánková, J. ‘Women are just more active’ – gender as a determining factor in involvement in senior centres. Ageing Soc. (2014) 34:1482–504. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X13000275

25. Amagasa, S, Fukushima, N, Kikuchi, H, Oka, K, Takamiya, T, Odagiri, Y, et al. Types of social participation and psychological distress in Japanese older adults: a five-year cohort study. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0175392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175392

26. Ang, S. Social participation and health over the adult life course: does the association strengthen with age? Soc Sci Med. (2018) 206:51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.03.042

27. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. What is gender? What is sex? Canada: Government of Canada (2023).

28. Oertelt-Prigione, S. Why we need ageing research sensitive to age and gender. Lancet Healthy Longev. (2021) 2:e445–6. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00149-5

29. Freysinger, VJ, and Stanley, D. The impact of age, health, and sex on the frequency of older Adults' leisure activity participation: a longitudinal study. Act Adapt Aging. (1995) 19:31–42. doi: 10.1300/J016v19n03_03

30. Noon, RB, and Ayalon, L. Older adults in public open spaces: age and gender segregation. Gerontologist. (2018) 58:149–58. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx047

31. Chan, CL, Yip, PS, Ng, EH, Ho, PC, Chan, CH, and Au, JS. Gender selection in China: its meanings and implications. J Assist Reprod Genet. (2002) 19:426–30. doi: 10.1023/A:1016815807703

32. Ho, C-H, and Card, J. Older Chinese women immigrants and their leisure experiences: before and after emigration to the United States. (Eds.) Todd, Sharon, comp. Proceedings of the 2001 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium. Gen. Tech. Rep. NE-289. (Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station), 291–297. (2002).

33. Pinto, JM, and Neri, AL. Trajectories of social participation in old age: a systematic literature review. Brazilian J. Geriatrics Gerontol. (2017) 20:259–72. doi: 10.1590/1981-22562017020.160077

34. Wanchai, A, and Phrompayak, D. A systematic review of factors influencing social participation of older adults. Pacific Rim Int. J. Nurs. Res. (2019) 23:131–41. Available from: https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/PRIJNR/article/view/114770

35. Townsend, BG, Chen, JT, and Wuthrich, VM. Barriers and facilitators to social participation in older adults: a systematic literature review. Clin Gerontol. (2021) 44:359–80. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2020.1863890

36. Pluye, P, and Hong, QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. (2014) 35:29–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182440

37. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

38. UNHCR. Older persons emergency handbook (2020) Available at:https://emergency.unhcr.org/protection/persons-risk/older-persons#:~:text=Overview,or%20age%2Drelated%20health%20conditions

39. Levasseur, M, Richard, L, Gauvin, L, and Raymond, E. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: proposed taxonomy of social activities. Soc Sci Med. (2010) 71:2141–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.041

40. Levasseur, M, Genereux, M, Bruneau, JF, Vanasse, A, Chabot, E, Beaulac, C, et al. Importance of proximity to resources, social support, transportation and neighborhood security for mobility and social participation in older adults: results from a scoping study. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15:503. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1824-0

42. Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools: Joanna Briggs Institute (2017) Available at:https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

43. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist [internet]. United Kingdom: CASP; (2018). Available at: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (Accessed December, 2022).

44. Hong, QN, Pluye, P, Fabregas, S, Bartlett, G, Boardman, F, Cargo, M, et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada.

45. Frantzen, KK, and Fetters, MD. Meta-integration for synthesizing data in a systematic mixed studies review: insights from research on autism spectrum disorder. Qual Quant. (2016) 50:2251–77. doi: 10.1007/s11135-015-0261-6

46. Lizarondo, L, Stern, C, Carrier, J, Godfrey, C, Rieger, K, Salmond, S, et al. Mixed methods systematic reviews In:. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. (Eds.) Aromataris, E, and Munn, Z. United States: JBI (2020)

47. Thomas, J, and Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2008) 8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

48. McLeroy, KR, Bibeau, D, Steckler, A, and Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. (1988) 15:351–77. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401

49. Lefrancois, R, Leclerc, G, Dubé, M, Hamel, S, and Gaulin, P. Valued activities of everyday life among the very old. Act Adapt Aging. (2001) 25:19–34. doi: 10.1300/J016v25n03_02

50. Statistics Canada (2006) The Participation and Activity Limitation Survey: Disability in Canada 2006. Available at: https://publications.gc.ca/collection_2007/statcan/89-628-X/89-628-XIF.html

51. Berry, HL, Rodgers, B, and Dear, KB. Preliminary development and validation of an Australian community participation questionnaire: types of participation and associations with distress in a coastal community. Soc Sci Med. (2007) 64:1719–37. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.12.009

52. Park, SM, Jang, SN, and Kim, DH. Gender differences as factors in successful ageing: a focus on socioeconomic status. J Biosoc Sci. (2010) 42:99–111. doi: 10.1017/S0021932009990204

53. Katagiri, K, and Kim, J-H. Factors determining the social participation of older adults: a comparison between Japan and Korea using EASS 2012. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0194703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194703

54. Yuying, Z, and Jing, C. Gender differences in the score and influencing factors of social participation among Chinese elderly. J Women Aging. (2022) 34:537–50. doi: 10.1080/08952841.2021.1988313

55. Sousa, NFDS, Lima, MG, Cesar, CLG, and de Azevedo Barros, MB. Active aging: prevalence and gender and age differences in a population-based study. Cad Saude Publica. (2018) 34:1–15. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00173317

56. Bukov, A, Maas, I, and Lampert, T. Social participation in very old age: cross-sectional and longitudinal findings from BASE. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2002) 57:P510–7. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.P510

57. Ponce, MS, Rosas, RP, and Lorca, MB. Social capital, social participation and life satisfaction among Chilean older adults. Rev Saude Publica. (2014) 48:739–49. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048004759

58. Sørensen, LV, Axelsen, U, and Avlund, K. Social participation and functional ability from age 75 to age 80. Scand J Occup Ther. (2002) 9:71–8. doi: 10.1080/110381202320000052

59. Haddaway, NR, Page, MJ, Pritchard, CC, and McGuinness, LA. (2022). PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews. 18:e1230. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1230

60. Eckert, MA. The influence of past and present life experiences on the social participation of the elderly. (Volumes I and II). Unpublished PhD’s thesis. Department of Sociology. Ann Arbor: New York University (1985), 576.

61. Ye, LL, Xiao, J, and Fang, Y. Heterogeneous trajectory classes of social engagement and sex differences for older adults in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1–15. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228322

62. Ang, S. Social participation and mortality among older adults in Singapore: does ethnicity explain gender differences? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2018) 73:1470–9. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw078

63. Marsh, C, Agius, PA, Jayakody, G, Shajehan, R, Abeywickrema, C, Durrant, K, et al. Factors associated with social participation amongst elders in rural Sri Lanka: a cross-sectional mixed methods analysis. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:636. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5482-x

64. Amirkhosravi, N, Adib-Hajbaghery, M, Lotfi, M-S, and Hosseinian, M. The correlation of social support and social participation of older adults in Bandar Abbas, Iran. J Gerontol Nurs. (2015) 41:39–47. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20150325-02

65. Khadr, Z. Differences in levels of social integration among older women and men in Egypt. J Cross Cult Gerontol. (2011) 26:137–56. doi: 10.1007/s10823-011-9140-3

66. Atchley, RC. Dimensions of widowhood in later Lif. Gerontologist. (1975) 15:176–8. doi: 10.1093/geront/15.2.176

67. Choi, KW, and Jeon, GS. Social network types and depressive symptoms among older Korean men and women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:11175. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111175

68. He, Q, Cui, Y, Liang, L, Zhong, Q, Li, J, Li, Y, et al. Social participation, willingness and quality of life: a population-based study among older adults in rural areas of China. Geriatr Gerontol Int. (2017) 17:1593–602. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12939

69. Li, YW, Xu, L, Chi, I, and Guo, P. Participation in productive activities and health outcomes among older adults in urban China. Gerontologist. (2014) 54:784–96. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt106

70. Martinez, IL, Kim, K, Tanner, E, Fried, LP, and Seeman, T. Ethnic and class variations in promoting social activities among older adults. Act Adapt Aging. (2009) 33:96–119. doi: 10.1080/01924780902947082

71. Naud, D, Généreux, M, Alauzet, A, Bruneau, JF, Cohen, A, and Levasseur, M. Social participation and barriers to community activities among middle-aged and older Canadians: differences and similarities according to gender and age. Geriatr Gerontol Int. (2021) 21:77–84. doi: 10.1111/ggi.14087

72. Rozanova, J, Keating, N, and Eales, J. Unequal social engagement for older adults: constraints on choice. Can J Aging. (2012) 31:25–36. doi: 10.1017/S0714980811000675

73. Schladitz, K, Förster, F, Wagner, M, Heser, K, König, HH, Hajek, A, et al. Gender specifics of healthy ageing in older age as seen by women and men (70+): a focus group study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:3137. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19053137

74. Wangliu, Y. Does intergenerational support affect older People's social participation? An empirical study of an older Chinese population. SSM Popul Health. (2023) 22:101368. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101368

75. Vega-Tinoco, A, Gil-Lacruz, AI, and Gil-Lacruz, M. Does civic participation promote active aging in Europe? Voluntas. (2022) 33:599–614. doi: 10.1007/s11266-021-00340-y

76. Levasseur, M, Roy, M, Michallet, B, St-Hilaire, F, Maltais, D, and Généreux, M. Associations between resilience, community belonging, and social participation among community-dwelling older adults: results from the eastern townships population health survey. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2017) 98:2422–32. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.03.025

77. Isherwood, LM, King, DS, and Luszcz, MA. Widowhood in the fourth age: support exchange, relationships and social participation. Ageing Soc. (2017) 37:188–212. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X15001166

78. Seko, K, and Hirano, M. Predictors and importance of social aspects in Ikigai among older women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:1–11. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168718

79. Naud, D, Généreux, M, Bruneau, JF, Alauzet, A, and Levasseur, M. Social participation in older women and men: differences in community activities and barriers according to region and population size in Canada. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:1124. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7462-1

80. Lee, Y, and Jean Yeung, WJ. Gender matters: productive social engagement and the subsequent cognitive changes among older adults. Soc Sci Med. (2019) 229:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.08.024

81. Kim, J, Lee, HY, Christensen, MC, and Merighi, JR. Technology access and use, and their associations with social engagement among older adults: do women and men differ? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2017) 72:836–45. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw123

82. Siette, J, Berry, H, Jorgensen, M, Brett, L, Georgiou, A, McClean, T, et al. Social participation among older adults receiving community care services. J Appl Gerontol. (2021) 40:997–1007. doi: 10.1177/0733464820938973

83. Adamson, J, Lawlor, DA, and Ebrahim, S. Chronic diseases, locomotor activity limitation and social participation in older women: cross sectional survey of British Women's heart and health study. Age Ageing. (2004) 33:293–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh090

84. Katja, P, Timo, T, Taina, R, and Tiina-Mari, L. Do mobility, cognitive functioning, and depressive symptoms mediate the association between social activity and mortality risk among older men and women? Eur J Ageing. (2014) 11:121–30. doi: 10.1007/s10433-013-0295-3

85. Costa, TB, and Neri, AL. Associated factors with physical activity and social activity in a sample of Brazilian older adults: data from the FIBRA study. Braz J Epidemiol. (2019) 22:e190022. doi: 10.1590/1980-549720190022

86. Dury, S, Stas, L, Switsers, L, Duppen, D, Domènech-Abella, J, Dierckx, E, et al. Gender-related differences in the relationship between social and activity participation and health and subjective well-being in later life. Soc Sci Med. (2021) 270:113668. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113668

87. Thomas, PA. Gender, social engagement, and limitations in late life. Soc Sci Med. (2011) 73:1428–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.035

88. Thompson, EH Jr, and Whearty, PM. Older Men's social participation: the importance of masculinity ideology. J Mens Stud. (2004) 13:5–24. doi: 10.3149/jms.1301.5

89. Isherwood, L. The gendered experience of social resources in the transition to late-life widowhood. Ageing Soc. (2021) 43:1–17. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X21000829

90. Yuta, N, Kumiko, N, Masami, H, Takashi, K, Ushio, M, Yoh, M, et al. Factors that promote new or continuous participation in social group activity among Japanese community-dwelling older adults: a 2-year longitudinal study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. (2018) 18:1259–66. doi: 10.1111/ggi.13457

91. Hsu, HC, Liang, J, Luh, DL, Chen, CF, and Wang, YW. Social determinants and disparities in active aging among older Taiwanese. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:3005. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16163005

92. Li, Y-P, Lin, S-I, and Chen, C-H. Gender differences in the relationship of social activity and quality of life in community-dwelling Taiwanese elders. J Women Aging. (2011) 23:305–20. doi: 10.1080/08952841.2011.611052

93. Goto, R, Ozone, S, Kawada, S, and Yokoya, S. Gender-related differences in social participation among Japanese elderly individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. J Prim Care Community Health. (2022) 13:215013192211111. doi: 10.1177/21501319221111113

94. Giesel, F, and Rahn, C. Everyday life in the suburbs of Berlin: consequences for the social participation of aged men and women. J Women Aging. (2015) 27:330–51. doi: 10.1080/08952841.2014.951248

95. Levasseur, M, Gauvin, L, Richard, L, Kestens, Y, Daniel, M, Payette, H, et al. Associations between perceived proximity to neighborhood resources, disability, and social participation among community-dwelling older adults: results from the VoisiNuAge study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2011) 92:1979–86. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.06.035

96. Sabbath, EL, Matz-Costa, C, Rowe, JW, Leclerc, A, Zins, M, Goldberg, M, et al. Social predictors of active life engagement. Res Aging. (2016) 38:864–93. doi: 10.1177/0164027515609408

97. Lee, H, and Ang, S. Productive activities and risk of cognitive impairment and depression: does the association vary by gender? Sociol Perspect. (2020) 63:608–29. doi: 10.1177/0731121419892622

98. Lu, N, Jiang, N, Lou, VWQ, Zeng, Y, and Liu, M. Does gender moderate the relationship between social capital and life satisfaction? Evidence from urban China. Res Aging. (2018) 40:740–61. doi: 10.1177/0164027517739032

99. Takagi, D, Kondo, K, and Kawachi, I. Social participation and mental health: moderating effects of gender, social role and rurality. BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:701. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-701

100. Park, NS, Jang, YR, Lee, BS, Haley, WE, and Chiriboga, DA. The mediating role of loneliness in the relation between social engagement and depressive symptoms among older Korean Americans: do men and women differ? J Gerontol Series B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2013) 68:193–201. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs062

101. Verbrugge, LM. The twain meet: empirical explanations of sex differences in health and mortality. J Health Soc Behav. (1989) 30:282–304. doi: 10.2307/2136961

102. Kawachi, I, and Berkman, LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. (2001) 78:458–67. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458

103. Belle, D. Gender differences in the social moderators of stress. Stress and coping: An anthology, 3rd ed. New York: Columbia University Press (1991), 258–274

104. George, W, and Dixon, A. Understanding the presence of gerotranscendence among older adults. Adultspan J. (2018) 17:27–40. doi: 10.1002/adsp.12051

105. Cachadinha, C, Pedro, J, and Fialho, JC, Social participation of community living older persons: Importance, determinants and opportunities. International conference on inclusive design" the role of inclusive Design in Making Social Innovation Happen.” London: Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design, Royal College of Art (2011)

106. Dawson-Townsend, K. Social participation patterns and their associations with health and well-being for older adults. SSM Popul Health. (2019) 8:100424. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100424

107. van Hees, SGM, van den Borne, BHP, Menting, J, and Sattoe, JNT. Patterns of social participation among older adults with disabilities and the relationship with well-being: a latent class analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2020) 86:103933. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2019.103933

108. Terkelsen, AS, Wester, CT, Gulis, G, Jespersen, J, and Andersen, PT. Co-creation and co-production of health promoting activities addressing older people-a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:1–20. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192013043

109. Thangavel, G, Memedi, M, and Hedström, K. Customized information and communication Technology for Reducing Social Isolation and Loneliness among Older Adults: scoping review. JMIR Ment Health. (2022) 9:e34221. doi: 10.2196/34221

110. Ma, R, Romano, E, Vancampfort, D, Firth, J, Stubbs, B, and Koyanagi, A. Physical multimorbidity and social participation in adult aged 65 years and older from six low- and middle-income countries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2021) 76:1452–62. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbab056

111. Moen, P, and Flood, S. Limited engagements? Women's and Men's work/volunteer time in the encore life course stage. Soc Probl. (2013) 60:206–33. doi: 10.1525/sp.2013.60.2.206

112. Gurung, RA, Taylor, SE, and Seeman, TE. Accounting for changes in social support among married older adults: insights from the MacArthur studies of successful aging. Psychol Aging. (2003) 18:487–96. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.487

113. Carstensen, LL. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Am. Psychol. Assoc. (1992) 7:331–8. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.3.331

114. Zhong, S, Lee, C, Foster, MJ, and Bian, J. Intergenerational communities: a systematic literature review of intergenerational interactions and older adults' health-related outcomes. Soc Sci Med. (2020) 264:113374. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113374

115. Bonaccorsi, G, Milani, C, Giorgetti, D, Setola, N, Naldi, E, Manzi, F, et al. Impact of built environment and neighborhood on promoting mental health, well-being, and social participation in older people: an umbrella review. Ann Ig. (2023) 35:213–39. doi: 10.7416/ai.2022.2534

116. Kadowaki, L, and Mahmood, A. Senior Centres in Canada and the United States: a scoping review. Can J Aging. (2018) 37:420–41. doi: 10.1017/S0714980818000302

117. Eagly, AH, and Wood, W. Social role theory of sex differences. The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of gender and sexuality studies. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers (2016). 1–3.

118. Huang, S-W, and Yang, C-L. Gender difference in social participation among the retired elderly people in Taiwan. Am J Chin Stud. (2013) 20:61–74.

119. Lim-Soh, JW, and Lee, Y. Social participation through the retirement transition: differences by gender and employment status. Res Aging. (2023) 45:47–59. doi: 10.1177/01640275221104716

120. Zhao, D, Li, G, Zhou, M, Wang, Q, Gao, Y, Zhao, X, et al. Differences according to sex in the relationship between social participation and well-being: a network analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:1–11. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192013135

121. Kristensen, MM, Simonsen, P, Mørch, KKS, Pihl, ML, Rod, MH, and Folker, AP. "It's not that I don't have things to do. It just all revolves around me" - men's reflections on meaning in life in the transition to retirement in Denmark. J Aging Stud. (2023) 64:101112. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2023.101112

122. Cudjoe, TKM, Roth, DL, Szanton, SL, Wolff, JL, Boyd, CM, and Thorpe, RJ. The epidemiology of social isolation: National Health and aging trends study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2020) 75:107–13. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby037