- Department of Behavioral, Social and Health Education Sciences, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States

Introduction: Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a risk factor for homicides and suicides. As poverty is both a predictor and a consequence of IPV, interventions that alleviate poverty-related stressors could mitigate IPV-related harms. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), a monthly cash assistance program, is one such potential intervention. In the state of Georgia, the TANF diversion program, which provides a non-recurrent lump-sum payment to deter individuals from monthly TANF benefits, is an understudied component of TANF that may influence the effectiveness of state TANF programs in supporting IPV survivors.

Aim: This study quantifies and qualifies the role of Georgia’s TANF diversion program in shaping IPV-related mortality.

Methods: This study relies on a mixed-methods sequential explanatory design. Using data from the Georgia Violent Death Reporting System (GA-VDRS), an interrupted time series analysis was conducted to estimate the effect of TANF diversion on IPV-related homicides and suicides. Semi-structured interviews were then administered with TANF policy experts and advocates, welfare caseworkers, and benefit recipients (n = 20) to contextualize the quantitative findings.

Results: The interrupted time series analysis revealed three fewer IPV-related deaths per month after implementing TANF diversion, compared to pre-diversion forecasts (coefficient = −3.003, 95%CI [−5.474, −0.532]). However, the qualitative interviews illustrated three themes regarding TANF diversion: (1) it is a “band-aid” solution to the access barriers associated with TANF, (2) it provides short-term relief to recipients making hard choices, and (3) its limitations reveal avenues for policy change.

Discussion: While diversion has the potential to reduce deaths from IPV, it may be an insufficient means of mitigating the poverty-related contributors to IPV harms. Its limitations unveil the need for improved programs to better support IPV survivors.

1 Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV), defined as “physical, psychological, or sexual abuse or aggression that occurs in a current or former romantic relationship” (1), is a pressing public health and policy concern. In its most severe forms, IPV can culminate in homicides or suicides of the victim, perpetrator or other individuals (i.e., corollary victims) (2). Since gender-based violence was decreed a political issue in the 1960s and 1970s (3), much of the public and legislative dialogue around government protections against IPV in the U.S. emphasized measures that were more reactive than preventive in nature. The most well-known of these include the Violence Against Women Act of 1994, which supported the criminalization of IPV and sought to equip victims with resources; the #MeToo movement, which increased awareness of sexual violence victimization; and, most recently, the ongoing advocacy for strengthening state-level anti-sexual assault statutes in response to Dobbs v. Jackson (2022), where the Supreme Court overturned the constitutional right to abortion (3–6). Relatively less attention has been paid to the factors that can initiate IPV, such as material hardship or economic stress (7–15).

A nascent body of both peer-reviewed and gray literature demonstrates how economic policies (such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, Section 8 housing vouchers, paid family leave, pandemic stimulus payments, and cash assistance from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program) can serve as primary and secondary prevention tools against various forms of violence (11, 16–26). Such efforts are critical for intervening early and curtailing violence before it begins or interrupting a cycle of violence. Additionally, because such policies are already in place in many cases, it can be resourceful and cost-effective to understand whether they have incidental effects on IPV (25) and elucidate possible areas for improvement to better respond to the needs of those in vulnerable circumstances. For instance, there is inconclusive evidence on whether TANF is currently reaching its full potential in addressing the needs of violence survivors (23). Examining the specific components of TANF may therefore allow researchers and policymakers to delineate the factors that promote or hinder TANF’s potential to support families and protect against IPV. This paper examines one such understudied policy in the state of Georgia: TANF diversion. As detailed in the literature review below, Georgia holds contextual value and public health significance for the study of welfare and IPV, given its notable prevalence of material hardship and violence victimization. Accordingly, this study aims to understand the role of TANF diversion in shaping IPV outcomes by (1) quantitatively estimating the effect of Georgia’s TANF diversion policy on IPV-related mortality with an interrupted time-series design and (2) qualitatively contextualizing Aim 1 findings through semi-structured interviews with key informants with TANF experience and expertise.

1.1 Literature review

The toll of IPV is both physical and psychological (1), impacting an estimated 10 million people in the U.S annually (27). In addition to being a significant public health problem that increases the risk of chronic disease, sexually transmitted infections, mental illness, substance use, and injury (28, 29), IPV is a risk factor for both homicides and suicides (2, 30). Roughly 1 in 5 homicide victims are killed by an intimate partner (1). Although studies on IPV-related suicides have largely taken place at state- and municipal-levels (31, 32), it is estimated that there may be over 2,900 IPV-related suicides occurring annually at the national level (31). Since IPV is underreported, even these grave prevalence figures likely underestimate the severity of the public health issue (33, 34).

Two decades of research demonstrate that poverty is both a predictor and a consequence of IPV, exerting mutually reinforcing effects (7–15, 35). For example, lower incomes may increase the likelihood of IPV exposure and IPV exposure may lower the survivor’s likelihood of remaining financially independent or escaping poverty (36, 37). This potential feedback loop suggests that interventions that alleviate poverty-related stressors could also be avenues for mitigating IPV-related harms. Indeed, 50 to 60 percent of IPV survivors participate in economic security programs (38), lending opportunities for intervention in such contexts. The Family Stress Model is a widely applied theoretical framework that can elucidate such levers for intervention; this model describes how financial stressors contribute to family economic pressure, which can impair mental health, and, in turn, produce relationship conflict or distress (12). The FSM has been directly applied to intimate partner violence (IPV) in a handful of studies (23, 24, 39), and an abundance of prior research implicitly demonstrates its applicability to IPV. For instance, there is evidence that economic hardship in the family can be a risk factor for caregiver depression, relationship dissatisfaction, relationship conflict, and aggression toward an intimate partner (12). Although the FSM extends beyond relationship conflict or IPV to issues related to child development, the present study focuses solely on IPV to better understand potential interventions for this specific pathway (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Family stress model adapted for violence (26).

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), a federal block grant program that provides monthly cash assistance to families in poverty, is one such intervention with the potential to reduce IPV-related harms (23, 40). However, the effectiveness of TANF has been subject to debate. In 1996, the United States Congress held a bipartisan agreement that welfare should neither disincentivize work nor promote dependency (41). This resulted in the passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), which concluded a 60-year-old program for qualified families to receive cash assistance (42). Legal researchers acknowledge that PRWORA dramatically reshaped the culture of public benefits in the United States, aligning with then-president Bill Clinton’s campaign pledge to “end welfare as we know it.” (41, 42). Specifically, one of the decreed objectives of the policy was to “end the dependence of needy parents on government benefits by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage.” (43) To meet this statutory goal, the New Deal-era cash assistance program, Aid to Family Dependent Children (AFDC) as well as other welfare programs were abolished, and TANF was introduced in their stead as a “workfare” program. TANF is a fixed block grant from the federal government that provides approximately $16.5 billion to states, the District of Columbia, U.S. territories, and federally recognized tribes. The stated goals of TANF are four-fold: (1) Provide assistance to needy families so that children can be cared for in their own homes or in the homes of relatives; (2) End the dependence of needy parents on government benefits by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage; (3) Prevent and reduce the incidence of out-of-wedlock pregnancies; and (4) Encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families (43). The block grant funding structure of TANF substantially differs from that of the AFDC, where the federal government contributed at least $1 in matching funds for every dollar states spent (43). In contrast, the TANF block grant transformed welfare into a program that afforded states considerable discretion on how they used their TANF funds (43). Furthermore, while the AFDC was almost exclusively a cash assistance program, states are free to use TANF funds for services and non-cash benefits (44). For example, besides cash, states can provide childcare vouchers and job training programs to those who qualify based on income and asset limits, as well as legal residency status (43). The discretion granted to states has led to wide variations in the use of TANF funds on basic cash assistance and reduced spending on basic cash assistance over time (43). For instance, state-level differences lie in who qualifies for TANF receipt, how much in cash assistance one can receive on a monthly basis, who is mandated to fulfill work requirements, if recipients are privy to benefit reductions for not fulfilling work requirements (i.e., sanctions), the maximum number of months recipients are eligible for benefits (i.e., lifetime limits), reductions in benefits after receiving payments for a certain period (i.e., benefit reduction limits), and penalties for having an additional child while receiving TANF (i.e., family caps) (23, 45, 46). This warrants additional research on specific components of TANF that may be helping or harming TANF’s potential to support families in general, and survivors of IPV in particular.

Diversion, a non-recurrent lump-sum payment aimed at diverting individuals from ongoing TANF benefits, is another component of TANF policy (45). In states such as Georgia, a diversion payment renders a TANF recipient ineligible for monthly assistance for up to 12 months; in others, the ineligibility period depends on the number of months’ worth of benefits the family received as a diversion payment (45, 47). The potential impact of TANF diversion on IPV is inconclusive because diversion has received less research attention compared to other TANF policy components, such as sanctions (23, 24, 48–51), and time limits (23, 24, 50, 52, 53). Currently, the District of Columbia and 32 states have a diversion policy in place, including Georgia (45). In 2020, a total of 642 individuals in Georgia received some form of diversion payment, and the average diversion payment per client was $168.72 (54), but can be as high as 4 months’ worth of cash benefits received through the regular TANF program (55). In contrast, the regular monthly TANF cash assistance payment is $223 for a family of three (or $2,676 per year if uninterrupted) (56).

Economic hardship and IPV are both pressing public health concerns in the state of Georgia. Its 14% poverty rate and $34,516 per capita income (55), coupled with its sharp 49% increase in IPV-related fatalities since 2020 (57) warrant policy-relevant solutions. The state experiences numerous racial and ethnic disparities in both poverty and IPV. For instance, the poverty rate of Hispanic, Black, and American Indian/Alaska Native individuals in Georgia are 19.7%, 20.3%, and 27% respectively, compared to the 9.5% poverty rate among White individuals (58). Additionally, Black women are disproportionately impacted by IPV in Georgia, at a rate that is 35% higher than that of White women and 2.5 times the rate of women of other races (59). As such, the state of Georgia deserves greater attention in the TANF literature to address these disparities.

Among the small handful of studies that do examine diversion policies, all but one (23) predate the last decade (60–64). Moreover, only one of these studies addresses Georgia, albeit limitedly, and the diversion policy discussed is different from the state’s present-day diversion program (64). Furthermore, only Spencer et al. (23) estimate the impact of diversion on IPV outcomes in 20 cities (with null results), but these are outside of Georgia. This study contributes to the literature by using evidence from Georgia to study the downstream influence of the current TANF diversion program on IPV.

1.2 Study hypothesis

Cash assistance programs and policies are widely held as effective anti-poverty measures that provide social protection and promote well-being (65). They can be lump-sum or recurring, and conditional versus unconditional (21). They operate in many countries across the world, with replicable evidence pointing to their capacity to inhibit IPV, even when such reductions are not an explicit objective of their programming (65, 66). For example, a review of 22 studies found that cash transfer programs in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), whose focus was primarily poverty reduction, led to a decrease in some form of IPV (emotional, physical, sexual) in 73% of the cases examined (67). Similarly, a meta-analysis of 14 evaluation studies of cash transfer programs in LMICs found, on average, decreases in all types of IPV (68). In the context of contemporary American social policy, the effects of cash or near-cash transfers on IPV are less conclusive. While some studies have found that the Earned Income Tax Credit can improve the material well-being and relationship quality in low-income families (69, 70), others have not observed a relationship between EITC and IPV (16, 71). Relatedly, while studies in the early 2000s suggest that more generous TANF policies may be protective against IPV (72–75), a more recent analysis found that fewer TANF restrictions increased coercive victimization (23).

Similarly, in the present study, TANF diversion has the potential to either act as a facilitator or a barrier in reducing IPV-related harms. On one hand, a diversion payment can support IPV survivors with an immediate crisis without requiring them to undergo a strict, time-intensive application process to qualify for monthly TANF benefits. On the other hand, the reduced access to regular cash benefits may increase their financial strain and exacerbate IPV-related harms. As much of the evidence and the Family Stress Model (12) point to financial support as a protective factor for IPV, it was hypothesized that TANF diversion, which is aimed at reducing access to monthly TANF benefits, will increase the incidence of IPV-related deaths in Georgia.

2 Methods

This study utilized a mixed-methods explanatory sequential design (76) comprised of two phases: (1) an interrupted time-series analysis to estimate the effect of Georgia’s TANF policy on IPV-related mortality, and (2) semi-structured qualitative interviews with 20 key informants to contextualize the quantitative findings.

2.1 Phase 1 (quantitative): Interrupted time series design

2.1.1 Data sources

The exposure of interest was the implementation of TANF diversion policy. The Urban Institute’s Welfare Rules Database (77) was referenced to determine July 2011 to December 2019 as the time period for analysis. Georgia’s ongoing diversion policy period began in February 2015. Before this, the state had another diversion policy in place from April 2006 to June 2011. Thus, July 2011 was used as the starting point to allow for a true “no policy” baseline, and December 2019 was used as an endpoint to avoid contamination of effects related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The dataset was split into two ‘before’ and ‘after’ periods based on the February 2015 start date of Georgia’s ongoing diversion policy. There were 1,278 observations in the 43 months prior to the implementation of the diversion policy (hereafter referred to as pre-diversion), and 1,579 observations in the 59 months following policy implementation (hereafter referred to as post-diversion).

The outcome of interest was intimate partner violence (IPV)- and intimate partner problem (IPP)-related mortality in the state of Georgia. Restricted state-level data on IPV- and IPP-related deaths, as well as decedents’ demographic information (age, sex, race, ethnicity), were obtained from the Georgia Violent Death Reporting System (GA-VDRS) through the Georgia Department of Public Health (78). The GVDRS consolidates data on violent deaths abstracted from death certificates, law enforcement records, coroners’ and medical examiners’ records, and Emergency Medical Services (EMS) reports. In this dataset, data are organized at the decedent level (i.e., one victim per observation). IPV- and IPP-related deaths were defined as homicides or suicides related to immediate or ongoing conflict or violence between current or former intimate partners. IPV- and IPP-related deaths were inclusive of corollary victims (for example, ex-husband kills his ex-wife’s new boyfriend, the child of an intimate partner, friend of the victim, or bystander). GA-VDRS defined an intimate partner as a current or former girlfriend/boyfriend, dating partner, ongoing sexual partner, or spouse, and is inclusive of same-sex partners. From July 2011 to December 2019. the dataset consists of 2,857 reports of IPV- and IPP-related deaths.

2.1.2 Analysis

To understand the demographic makeup of the dataset, univariate analysis of race, ethnicity, gender, and age variables was conducted. An interrupted time series design estimated with an ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average) model was then used to analyze the effect of Georgia’s TANF diversion policy on reports of IPV- and IPP-related deaths. ARIMA is a modeling technique with a time-dependent outcome variable, a function of past counts of the variable and error values. It can be used for evaluating the impact of policy-level interventions on time-dependent outcomes as it controls for underlying trends, autocorrelation, and seasonality (79). It consists of four model components: autoregressive (AR) model, moving average (MA) model, seasonal model, and differencing. An ARIMA model is constructed by combining the four model components and is notated as ARIMA (p, d, q; P, D, Q). Here, p is the lag value of the AR component, d is the differencing interval, and q is the lag value of the MA component, and P is the seasonal lag value of the AR component, D is the seasonal differencing interval, and Q is the seasonal lag value of the MA component (79).

The model was used to examine the number of IPV- and IPP-related violent deaths at monthly time points from July 2011 to December 2019. Indicator variables for diversion were assigned to separate pre- and post-diversion data. The Box-Jenkins approach was followed (79), and an initial ARIMA model was developed to fit only the pre-diversion data. After establishing that the series was stationary prior to the introduction of TANF diversion, the optimal (p, d, q; P, D, Q) values for the ARIMA model were determined by examining the autocorrelation (ACF) and partial autocorrelation functions (PACF). Upon performing diagnostic checks of the residual ACF and PACF, the optimal (p, d, q; P, D, Q) values of the best-fitting model that achieved white noise were (0,0,3; 0,0,1)9. The ARIMA model was re-estimated for the entire time series, including the post-diversion data. A coefficient test was performed to estimate the effect of the diversion policy on the number of IPV- and IPP-related deaths.

2.2 Phase 2 (qualitative): Semi-structured interviews and thematic analysis

2.2.1 Recruitment and consent

To contextualize the findings from Phase 1, in-depth semi-structured interviews (80) were conducted with key informants possessing experience and expertise in TANF. Eligible interviewees met one or more of the following criteria: (1) having a history of in-depth engagement with Georgia’s TANF policy through research and direct action, (2) bearing a professional responsibility to identify and refer eligible clients to TANF, or (3) being a current or former recipient of any TANF benefit in Georgia. Due to the recruitment challenges associated with a stigmatized, hard-to-reach group, as well as the rapidly declining population of TANF recipients in the state, eligibility criteria were not limited to TANF recipients with a history of receiving TANF diversion or experiencing IPV.

The study team’s existing relationships with community-based organizations and policy research institutes were instrumental in facilitating recruitment. Using purposive and snowball sampling methods (81), key informants were contacted from four child and family advocacy groups, one policy research organization, a school district, and a safety net hospital, all located in Georgia. Additionally, one interviewee was recruited from a policy research organization operating at the federal level. These initial touchpoints allowed the study team to engage TANF policy experts and caseworkers responsible for referring eligible individuals to TANF (e.g., pro-bono attorneys and a school-based specialist) as interviewees. The interviewees then disseminated a study flyer within their networks to aid the recruitment of current and former TANF recipients. TANF recipients contacted the study team via phone or email to express their interest and eligibility in participating in an interview. The final sample of interviewees consisted of six policy experts, three caseworkers, and 11 TANF recipients (n = 20).

All interviewees provided informed consent. Two members of the study team read a verbal consent document, provided an opportunity for interviewees to ask questions, and asked the interviewees to reiterate key components of the consent document to confirm their understanding of the study terms: Would you describe in your own words what you are being asked to do? What would happen if you decided to stop the study? Interviewees’ consent to participate and permission to record interviews were then documented. Following the interview, all interviewees received a $50 gift card as remuneration.

2.2.2 Study instruments and data collection

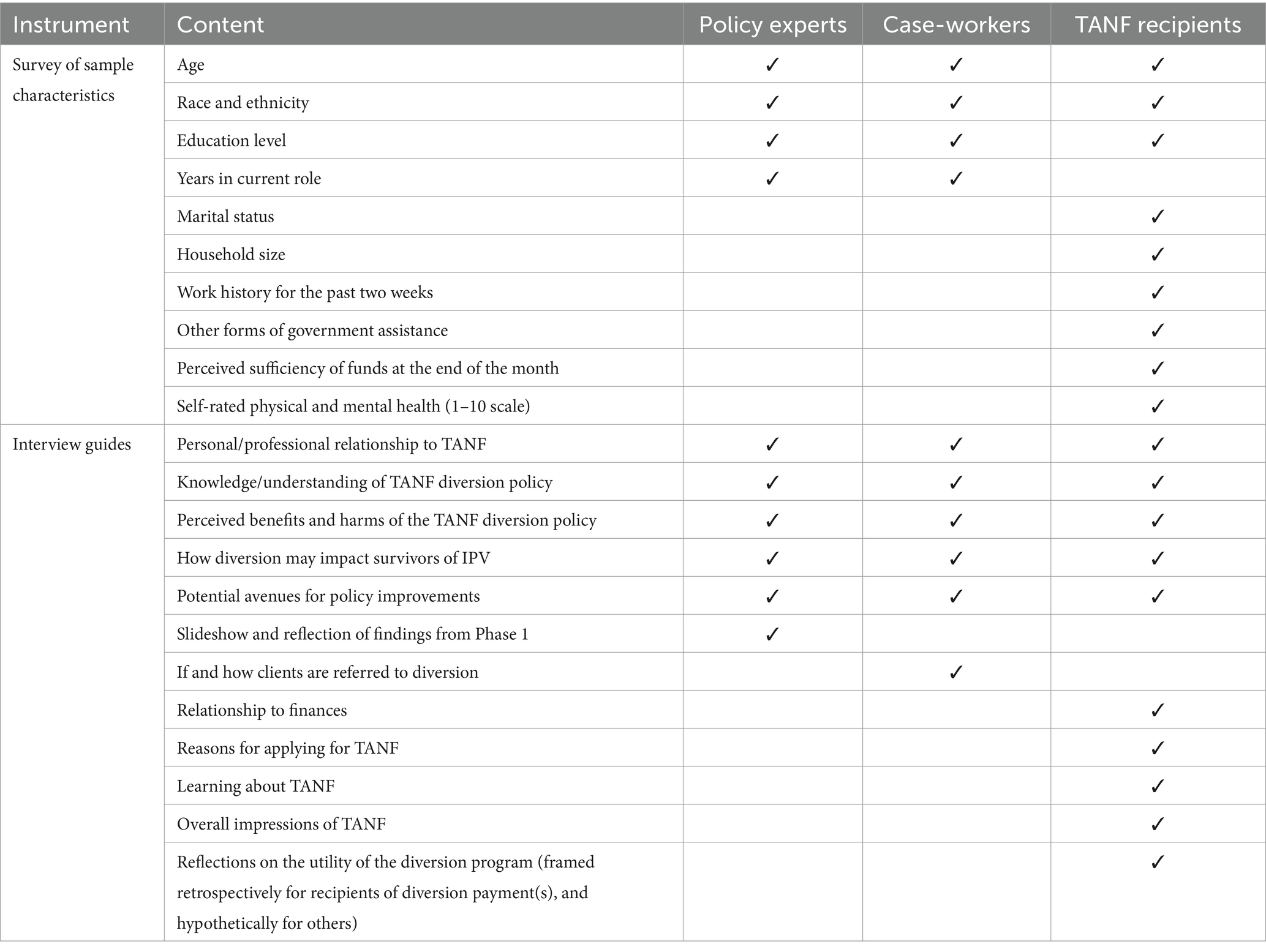

All interviews were held over Zoom. Interviewees who did not have access to a computer joined the call using a teleconferencing number. To document the interviews, study team relied on Zoom’s record feature (preserving only the audio recordings) and professional transcription services. All interviews were anonymized. Table 1 summarizes the content of each study instrument administered during the interviews.

Surveys of Sample Characteristics . Each interview began with an interviewer-administered survey via Qualtrics. Survey questions were tailored based on the grouping of the interviewee as a policy expert, caseworker, or TANF recipient (Table 1). All interviewees were asked about their age, race, ethnicity, and education level. TANF policy experts and caseworkers were additionally queried about the number of years in current role. The questions for TANF recipients were also tailored to include questions about marital status, household size, work history for the past 2 weeks, other forms of government assistance, perceived sufficiency of funds at the end of the month, as well as self-rated physical and mental health (1–10 scale).

Interview Guides . The survey of sample characteristics was followed by an in-depth semi-structured interview. Based on theory (23, 24, 39, 82) and prior research on TANF and violence (23, 24), three interview guides were developed for each group of interviewees: policy expert, caseworker and TANF recipient (Table 1). All interviewees were asked about their personal or professional relationship to TANF, their understanding of TANF diversion policy, perceived benefits and harms of the TANF diversion policy, and recommendations. Policy experts were delivered a slideshow of findings from Phase 1 and asked to reflect on the implications of the results in relation to their own knowledge and experience of TANF. TANF caseworkers were asked if and how they referred participants to the TANF diversion program. TANF recipients were queried about their relationship to their finances (i.e., their current financial support system, whether finances are a source of stress, their income in relation to their expenses), their reasons for applying for TANF, how they learned about TANF, and their overall impressions of TANF. In addition, two distinct sets of questions related to the diversion program were drafted for recipients, which were to be used based on their experience with diversion. For those who had received a diversion payment, a set of retrospective questions were developed to understand their experience and perceptions of the diversion program. For TANF recipients without exposure to TANF diversion, a set of hypothetical questions asked to reflect on circumstances where they would benefit from a one-time diversion payment over the monthly TANF schedule, and vice-versa. Since none of the recruited interviewees received a diversion payment, only the hypothetical questions were utilized.

2.2.3 Analysis

Univariate analysis was conducted to summarize the data from demographic surveys. Interview transcripts were analyzed using an iterative thematic approach (83) in a series of steps. First, codes and subcodes were developed using a combination of inductive and deductive approaches. Inductive codes were borne out of the first four transcripts, whereas deductive codes stemmed from the interview guide. To ensure that the codes were meaningful and consistent, the first, second, and third authors collaborated on a codebook that standardized each code with definitions and constructs. The first and second authors then referenced the codebook to designate codes to all interview transcripts. To capture new concepts as they emerged, codes were revised iteratively until saturation (i.e., until the codes fully represented all the relevant information in the transcripts). Two coders then coded each transcript and met to reconcile codes and resolve discrepancies. Based on the patterning of the codes, salient themes were derived and substantiated with quotations.

3 Results

3.1 Quantitative Phase 1: Interrupted time series design

3.1.1 GA-VDRS sample description

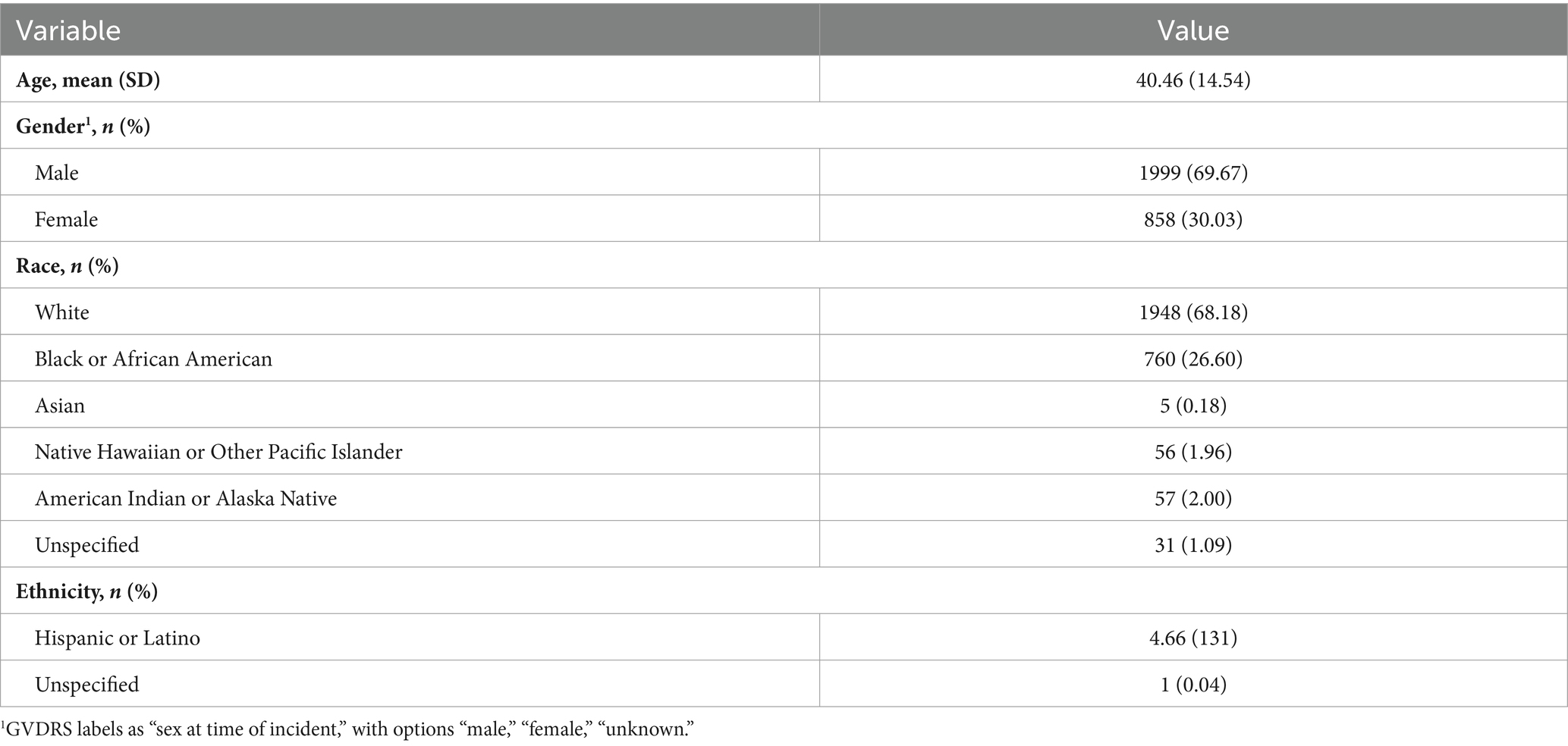

Table 2 summarizes the demographic makeup of Georgia’s IPV and IPP mortality data reported on the NVDRS from 2011 to 2019.

3.1.2 Findings from interrupted time series analysis

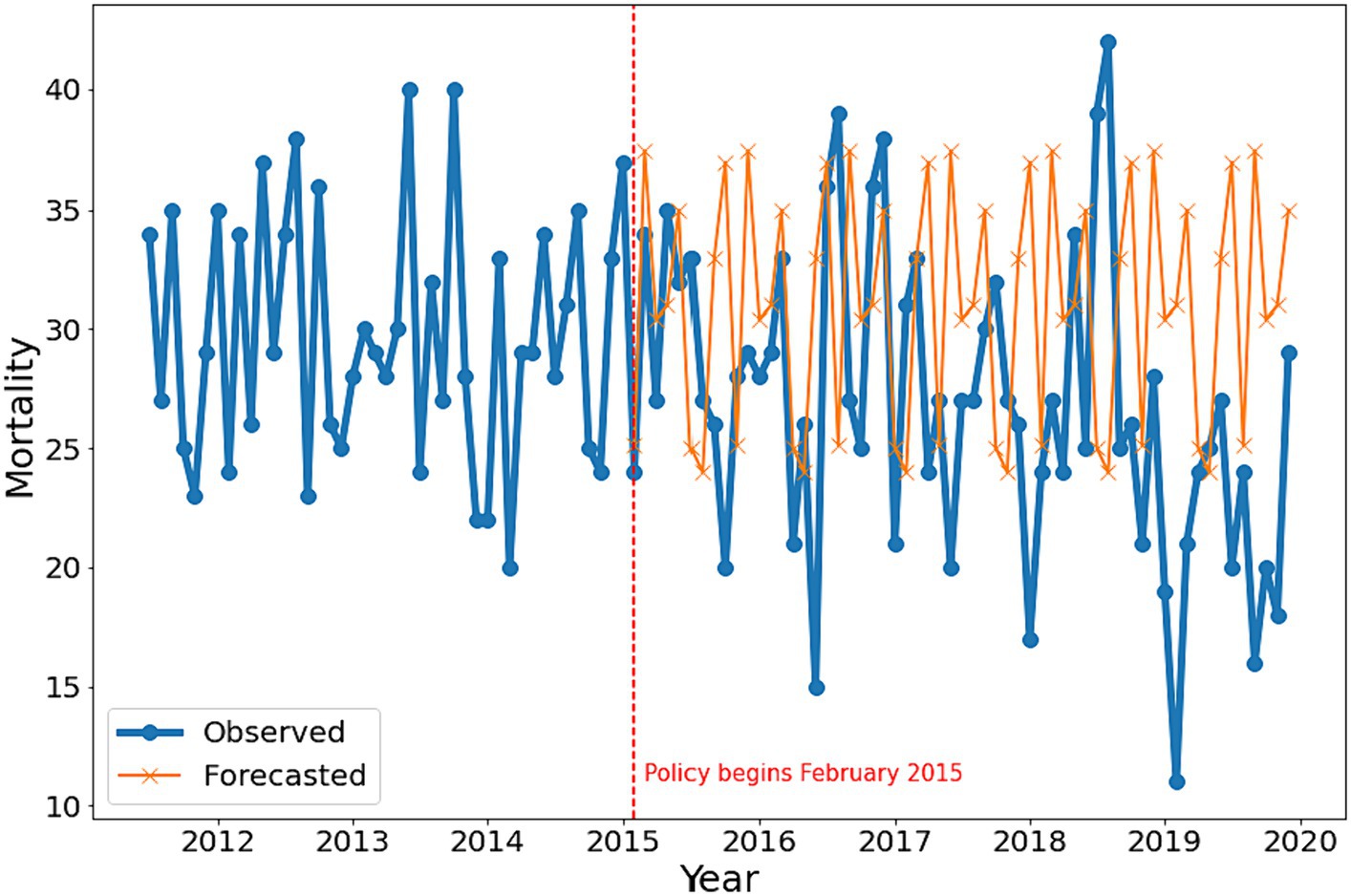

With the inclusion of post-diversion mortality data, the ARIMA (0,0,3 0,0,1)9 model revealed 3 fewer observed deaths per month, compared to pre-diversion forecasts (coefficient = −3.003, 95%CI [−5.474, −0.532], p = 0.017). As such, the findings did not support the study’s initial hypothesis (i.e., that diversion will result in an increase in IPV-related mortality). Figure 2 illustrates the change in IPV- and IPP-related mortality trends after the 2015 diversion policy and compares the forecasted pre-diversion mortality trend to the observed post-diversion mortality trend.

Figure 2. Comparison of observed and forecasted IPP and IPV-related mortality before and after TANF diversion policy implementation in 2015 (2012–2019).

3.2 Qualitative Phase 2: Semi-structured interviews

3.2.1 Interviewee sample description

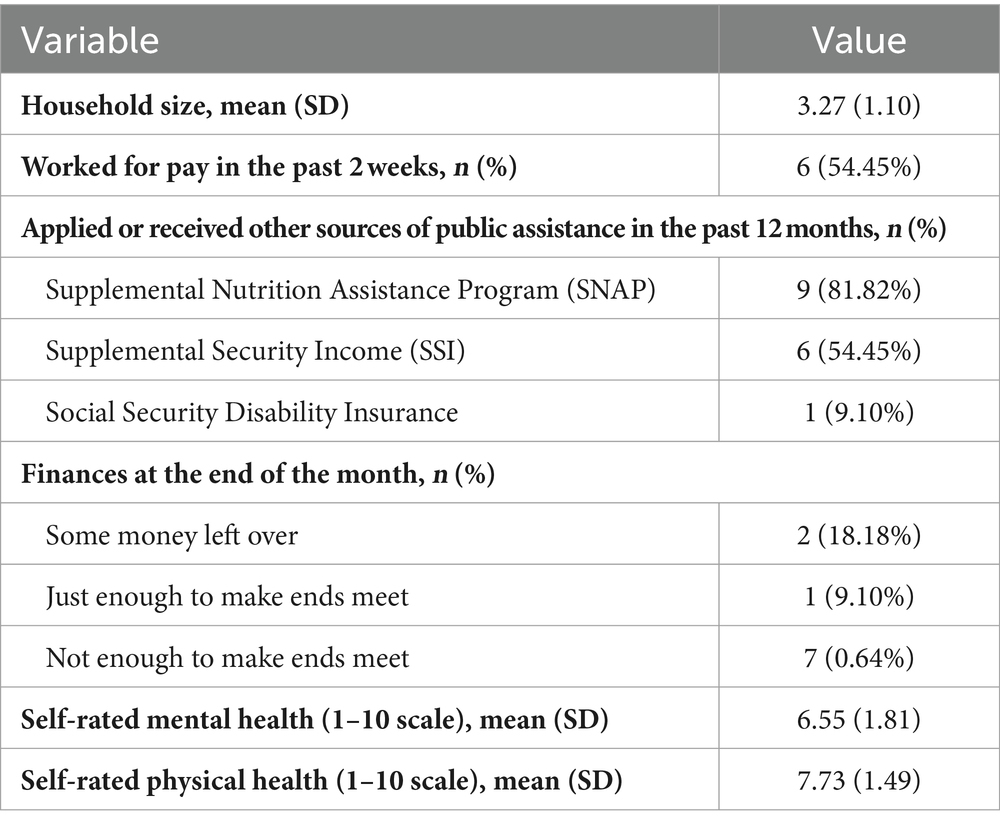

Table 3A summarizes the demographic information of the policy experts, caseworkers and TANF recipients interviewed about TANF diversion. Table 3B provides information on additional details gathered from TANF recipients.

3.2.2 Findings from thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews

Theme 1: Diversion as a “band aid” solution for the access barriers to receiving monthly TANF payments

Subtheme 1.1: Diversion disincentivizes seeking public assistance

Despite the quantitative findings on the protective effects of diversion payments on IPV-related mortality, diversion payments were largely considered unfavorable by interviewees because they offered a smaller one-time payment than what the recipients would have received with regular TANF payments over the course of a year.

Caseworkers described diversion as a deliberate effort to turn individuals away from receiving their fair share of public assistance:

“Cynically, it is an effort to pay off poor people with one little bit of money, foregoing some other little bit more money.” (Caseworker)

Multiple interviewees described that there was little benefit to receiving a small amount of assistance through a one-time TANF diversion payment:

“For my clients to benefit from TANF, the amounts need to be livable [….]. My clients need easier accessibility. My clients need childcare. My clients need child support services. My clients need accessible healthcare and resources that help them with their food insecurity. Diverting them to try and put a lump sum of some smaller amount [….] would not be helpful for my clients. [….] I can’t see any helpfulness except from my clients’ perspective that any funds to help them immediately is better than the anticipation of long-term help, which they never see.” (Caseworker)

Subtheme 1.2: Potential harms of diversion

According to some policy experts, the diversion program may even be harmful because it disqualifies TANF recipients from accessing other TANF benefits and the monthly TANF payments for the next 12 months:

“To have the one-year pause seems like it’s a lot. It seems like that might be overkill. If there was a way to lessen that, I think it might be beneficial. I mean, again, the reason why people are in the program is because they are needy. That’s the N part of [TANF]. To think that this one-time payment is going to overcome the year in the future? I do not know. I just think that that’s too long.” (Policy Expert).

According to one interviewee, the harms of TANF diversion go beyond losing access to monthly cash payments:

“What happens when you get a diversion payment is you lose access to some of the other services that TANF provides. So, if there is case management services, if there is childcare assistance, if there is help with the things you need to go to work, you lose access to all of those. So, what you’re getting is a short-term cash payment, but nothing else.” (Policy Expert)

Another interviewee also perceived TANF diversion to have harmful implications from a broader population health perspective:

“I could see it deterring health equity. I think whenever you have these programs that say, “I’m happy to help you now, but that means I can’t help you in the future”. People who are going to take you up on that offer are going to be the ones that are the most vulnerable. And, by definition, [….], they’re the highest risk for health disparities and health inequities. So I definitely feel like this has a potential to be harmful, just even despite seeing your graphs about the deaths.” (Policy Expert)

Subtheme 1.3: Barriers to accessing traditional TANF payments

Interviewees also highlighted multiple barriers to receiving the “traditional” monthly TANF payments, suggesting that this was not an easily accessible resource. One policy expert described how such barriers may be particularly detrimental to IPV survivors:

“Georgia is famous for having really extreme barriers in order to access cash. And it’s really unfortunate because if you are in a situation where you are potentially under threat of violence or have already experienced violence, […] moving quickly and accessing resources quickly to either get out of that circumstance is essential so that that’s the harm, basically, you have this resource, but you’re making it putting up so many barriers that it’s almost as if the resource may not available to you, right, if you don’t need these certain conditions. And to me, [that] should not be the point of a cash assistance program.” (Policy Expert)

Logistical hurdles during the TANF application process, such as depending on public transportation to the Department of Child and Family Services (DCFS) and lengthy office wait times, made the application process itself more difficult to access. Recipients also noted the unfavorable conditions of the DCFS facilities, lack of resources, and unreliable staff assistance as additional barriers, citing employee burnout and insufficient staffing as potential reasons for the difficulties during the process:

“I’m very serious when I say I think they are burned out and no one wants to do that job anymore because I remember standing in lines where women have two or three children. It’s hot, they have barely any AC. The lines are out the door. And then the computers break down.” (TANF Recipient)

Application completion and processing times were cited as barriers to accessing the monthly TANF benefits. One participant recounted the length of time it took for them to complete the application, and the time it took for them to receive an update on their application status:

“If people still are getting benefits, I would like to see how they’re doing it. Maybe they’re taking a whole day off to go there because that’s basically what you have to do now. You can’t just go in for 30 minutes and leave. It’s a whole day job going to the DFCS [Division of Family and Children’s Services] office. […] It took like a whole – like a month for them to process everything and then for them to send me out a letter to tell me when I was approved. It took like 30 days.” (TANF Recipient)

Additionally, recipients described excessive documentation requirements, including those that may not be readily on-hand, which delayed their time to complete the application:

“You’ve got to have, first, the kids’ information, like their birth certificates, social security numbers, stuff like that. I can’t say it was easy. […] When I was doing [the application] I did get a little frustrated, ’cause I was like, […] “dang, y’all ask for so much stuff. Why y’all ask for all this stuff?” And I had to take stuff back up because some stuff I didn’t have at the time; I had to go get it and take it back up there. So that really made the process even a little longer.” (TANF Recipient)

Many recipients expressed being denied TANF benefits multiple times and having to complete two or more applications before being approved. Interviewees were dissatisfied by caseworker communication and the extensive amount of time it took to be followed-up with on their application. One interviewee also described never being contacted about their application status or the reason for the final decision:

“Oh my God. It was kind of rough and stressful. Cause the first time that I applied a caseworker never called and contacted me. She didn’t ever get in contact. And I checked my gateway account and I was denied. But she didn’t ever tell me why. So it was stressful cause I could never get in contact with her.” (TANF Recipient)

Subtheme 1.4: Diversion as an alternative (albeit imperfect) solution for barriers to accessing traditional TANF payments

Given these and other potential hurdles to receiving monthly TANF payments, policy experts contended the one-time diversion payment be a more readily-available alternative in these circumstances:

“The hassle factor in TANF programs is really high and significant. And so, [diversion] gives families who need small amounts of income […] a better source of help than going through the onerous requirements that what they’d otherwise have to go through.” (Policy Expert)

Interviewees deemed TANF diversion as a possible mechanism to overcome eligibility criteria that may not always be easy for IPV survivors to meet, such as work requirements:

“So, I think [diversion] could be helpful for families who have pretty significant barriers who can’t meet the work rate. So, they’re going to lose assistance, then they might actually get some assistance rather than not getting anything.” (Policy Expert)

Thus, although TANF diversion in and of itself is not a desirable policy, the challenges associated with receiving the monthly TANF payments suggest that TANF diversion might be operate as a “band aid” solution to these barriers. This may explain the findings on the protective effect of diversion on IPV-related mortality in Phase 1, as suggested by policy expert interviewees:

“Georgia’s TANF program is so horrendous in terms of allowing people to access it […] because their program is so bad that diversion payments actually offer an alternative.” (Policy Expert)

Theme 2: Diversion as short-term relief to recipients making hard choices

All interviewees agreed that the main benefit of diversion, especially to victims of IPV, is that the one-time payment may overcome some of the hurdles of the regular TANF application by providing quicker assistance. One caseworker explains the need for IPV victims to have immediate access to resources:

“We have discovered that victims of domestic violence need the financial resources they can gather before they can leave. The fewer resources that they have at their fingertips, the less likely it is that they and their children will be able to escape beatings, abuse, and murder without those resources.” (Caseworker)

Other policy experts described how diversion can play a role in providing this short-term relief:

“If we’re thinking about people who are in crisis and need access to cash supports, diversion is one mechanism that could be helpful. So instead of going through, which might be perhaps more a little bit more rigorous of an application process, diversion could be a way to more quickly get access to those cash supports to help somebody in crisis to quickly just address needs of safety and economic stability.” (Policy Expert)

Another interviewee similarly described the temporary utility of this relief in assisting an IPV survivor escaping crisis situations:

“I imagine that our patients do need cash assistance, especially because a lot of times people need safety transfers. They come in and they’re injured close to their home or someplace where they don’t feel safe going back and they do need cash assistance to help them out of that situation and get rid of those environmental stressors. I can see where the benefit would be just to have this money easily or hand it to them. That’s the only benefit because I think in the long term, if they’re not having a whole year after that, it can be pretty detrimental, especially if people are relying on that assistance. I think the risk will outweigh the benefit, though, in the long term.” (Policy Expert)

This was corroborated by a TANF recipient who suggested that diversion can help survivors transition away from dire circumstances:

“Since they’ll try to use these funds to make their ends meet, at least they can settle with it and at least move on from their problems or what they have gone through.” (TANF Recipient)

Beyond this, it was challenging for interviewees to perceive other, more long-term benefits to diversion. One caseworker suspected diversion to be a mechanism of absolving the TANF program of its responsibilities to provide for families in the long-term:

“This sounds like a big cost-cutting effort that would prey on desperately needy and desperately poverty-stricken women who need money immediately to feed their children or get them through some kind of emergency. I would assume that was the purpose of it and to cut the cost of it.” (Caseworker).

Consistent with the quote above, caseworkers contended that diversion particularly affects individuals making hard choices. During these periods of vulnerability, individuals may opt for quick access to the one-time payment, even if the dollar amount is lower than what they may have received over the course of 12 monthly payments:

“Exactly. If you have to pay your rent, you have to do what you have to do to keep yourself and your child from going homeless. It’s not a hard choice. You would make it. I would make it. Any parent would make it to keep their child from being homeless or from being hungry or from being sick.” (Caseworker).

These difficult circumstances were similarly acknowledged by another interviewee:

“I think about the families that I serve, if you’re stuck between a rock and a hard place, you are likely going to take this big lump sum, I would think.” (Caseworker)

Theme 3: Limitations to TANF diversion reveal avenues for policy change.

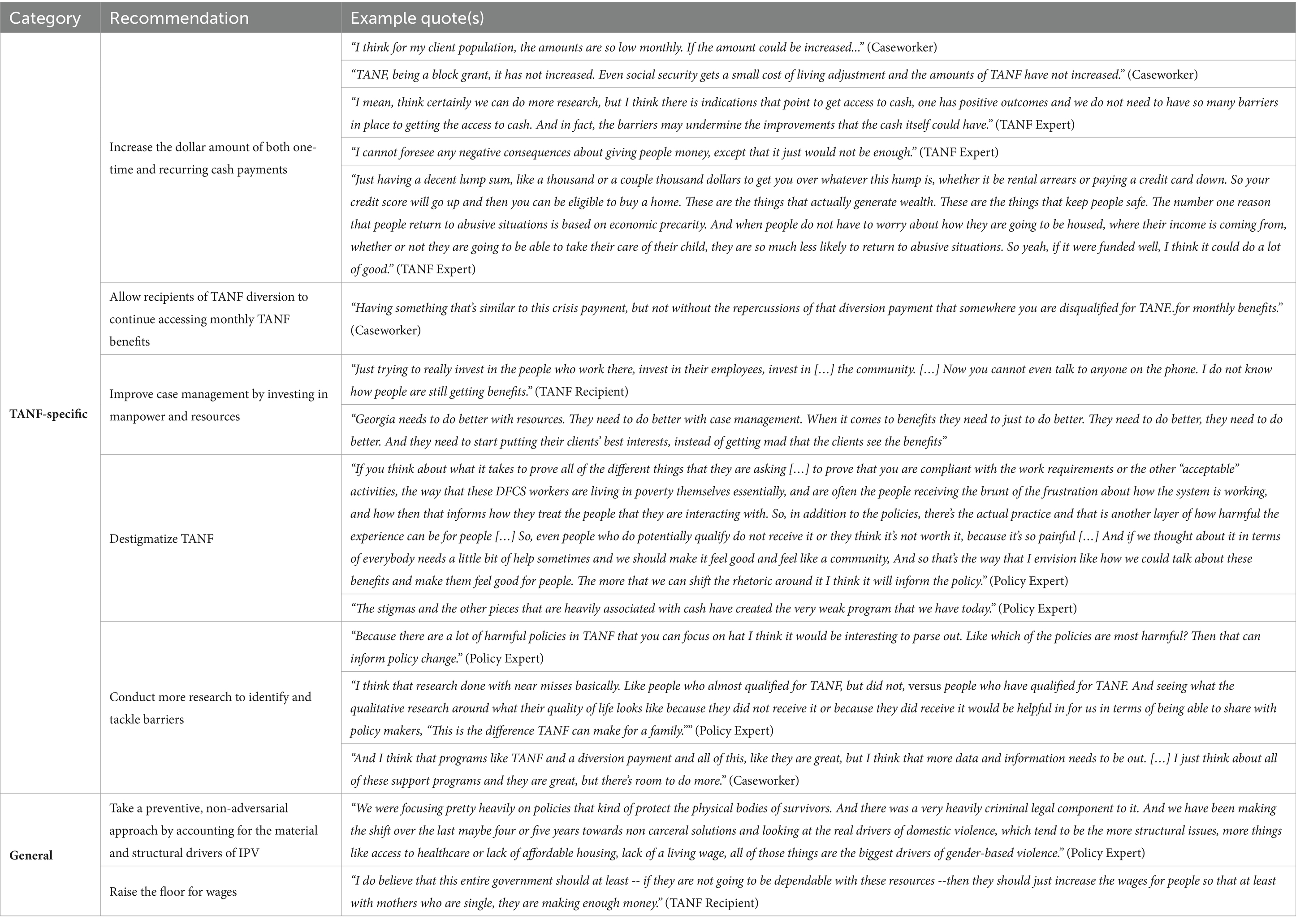

There was consensus among interviewees that Georgia’s TANF program, and diversion specifically, are fraught with limitations. Accounting for these challenges, TANF recipients, caseworkers, and policy experts shared several avenues for policy advocacy to improve the material conditions of IPV survivors. Some proposed ways of improving Georgia’s implementation of TANF, whereas others cited policy alternatives that may be better suited for curtailing IPV. Table 4 summarizes these recommendations.

4 Discussion

Findings did not support the hypothesis that diversion will increase the number of IPV-related deaths in Georgia. Instead, three fewer deaths per month were observed after the implementation of TANF diversion. However, the qualitative findings suggest that diversion (1) is a “band-aid” solution to the access barriers associated with TANF, (2) only provides short-term relief to recipients making hard choices, and (3) has limitations that reveal avenues for policy change.

Our quantitative findings suggest that TANF diversion in Georgia carries the potential to reduce IPV-related harms. These findings stand in contrast to the literature demonstrating the protective effects of ongoing cash assistance on IPV (11, 16–26). Further investigation is necessary to determine whether TANF diversion is only reducing the escalation to death in incidences of IPV, or mitigating IPV more broadly.

As documented previously, there are numerous hurdles to receiving TANF benefits in Georgia, including but not limited to stringent eligibility criteria (84), 45-day-long application processing times (85), 30-hour work requirements, and 48-month time limits (43). This is also evidenced in the historically low TANF-to-poverty ratio in Georgia, wherein for every 100 families living in poverty, only five receive assistance through TANF; this TANF-to-poverty ratio has declined 77 points since the mid-1990s (86, 87). Indeed, in 1994, there were 141,596 families in Georgia receiving TANF assistance; last year, in 2022, only 5,734 families received assistance – a 96% decline in TANF receipt (88). Therefore, for many, a diversion payment may be the only route for cash assistance, and it cannot be assumed that monthly TANF payments are a readily available alternative. Additionally, to receive a diversion payment, an individual would not have to subject themselves to the potentially challenging work requirements associated with the recurring monthly TANF benefits (89), which may facilitate access to cash benefits. These lower barriers to accessing diversion payments relative to traditional TANF monthly benefits may potentially explains some of the protective effects observed in the time-series analysis.

Coupled with the results from the time-series analysis, the qualitative findings on the role of diversion as short-term relief suggest that many individuals may opt for a diversion payment to curb an acute stressor before their challenges intensify, such as emergency assistance to pay rent, utility bills, repairs, other housing- or vehicle-related costs, or domestic violence services. This has been suggested by other examinations of TANF diversion at the national level (47). Additionally, there is broad recognition among psychologists that IPV is associated with psychological stress of varying intensities and durations (24, 90–93). For example, IPV survivors may endure long-term or chronic stress from continual violence and intimidation, as well as short-term stressors that culminate over time, such as becoming unemployed or lacking the transportation to escape (24, 93–95). Therefore, administering short-term interventions have been identified as an important element of coordinated community responses to IPV (96). However, the current evidence on short-term IPV interventions prioritizes psychotherapeutic modalities and shows greatest promise for intrapsychic needs – and even then, the effects of these short-term interventions are known to attenuate over time (96). While there is some exploratory evidence on the role of small amounts of cash for short-term (yet insufficient) relief among IPV survivors who are TANF recipients (24) and women living with HIV (97), there is a need for additional research to conclusively determine whether quick material support (such as a one-time payment) can specifically function as a short-term intervention against acute stressors. It is also critical to examine how these short-term resources can be paired with more durable, long-term interventions that relieve more chronic concerns and sustain the well-being of IPV survivors.

While some scholars have coined TANF a failure due to its limited reach and the barriers noted above (41, 86), TANF’s past and present suggest that the policy may be functioning as intended, with unlimited discretion at the state level. Considering (a) the program’s original goal of keeping families off welfare rolls (98) without accountability for ensuring their self-sufficiency (41), (b) its efforts to divert individuals from receiving monthly benefits (45), (c) its marginalization of Black and Latinx families (87, 99), (d) states’ redirection of TANF funds to other programs (100), (e) states’ accumulation of TANF surplus funds, (e.g., $2.2 million in Georgia) (87) and (f) the paucity of federal oversight as states carry out these activities (100, 101) suggests that TANF’s inertia in lifting families out of poverty may be systemic. Indeed, TANF closely represents neoliberal philosophy: government responsibility is relegated and decentralized to lower administrative units that determine the roles and implementation, and eligibility for aid is determined through the lens of economic productivity and exchange (i.e., work requirements), rather than broader social and systemic forces (102). Accordingly, TANF should not be considered a panacea for alleviating poverty (101). However, it is one of the only income-support programs of its kind in the U.S. since Unemployment Insurance and Supplemental Security Income have more precise eligibility criteria, and EITC would be insufficient as the sole anti-poverty program. Because TANF still provides relief to a small proportion of families in poverty, it is important not to abandon the policy without introducing structural reforms that remedy the inequities and material conditions forcing families to seek TANF in the first place.

4.1 Limitations and strengths

Although this study moves the TANF literature forward by examining an understudied policy component, several limitations must be acknowledged. Beyond the possibilities noted above, other unexplored factors may be shaping the relationship between TANF diversion and IPV-related mortality. With limited data availability, and the inability to randomize diversion payments, an interrupted time-series design was the most robust alternative for examining the outcomes of interest. The results from this analysis may be nullified should other confounders occur near the time that TANF diversion policy went into effect. Of note, the COVID-19 pandemic assistance relief is not one of these confounders, as the study does not use mortality data from 2020. One potential confounder may be state legislation that extended unemployment benefits to IPV survivors in 2015 (103). As more data becomes available, future research should model the effect of both policies simultaneously.

Additionally, the study only examines TANF diversion in Georgia. Because the association between TANF diversion and IPV-related mortality may vary by contextual factors and state-level differences in the implementation of TANF policy, findings may not be generalizable to other states implementing a TANF diversion policy. As such, future research should replicate these analyses in other states.

Despite these limitations, there are multiple strengths to this study. Population-level studies of the impact of social and economic policies on violence are only recently receiving research attention in the U.S. The study contributes to this growing body of evidence by investigating a specific element of a welfare policy that can influence its effectiveness in supporting disadvantaged families. Because TANF is a complex program, malleable to social and political conditions at the state level, this natural experiment lends an opportunity to evaluate the impact of a TANF policy component within the “real world.”

Additionally, the focus on mortality data in the interrupted time series analysis responds to a recent call in the injury and violence field to examine the forms of IPV that culminate in lethal outcomes (2). According to this call, these instances of IPV represent missed opportunities to intervene before the escalation to fatalities, either due to ineffective interventions or a complete lack thereof (2). These fatal cases of IPV, therefore, deserve greater research attention to identify alternative mechanisms of prevention. However, the field may also benefit from additional research that characterizes the effect of TANF diversion on incidences of IPV that do not necessarily result in deaths to clarify whether the program prevents IPV more broadly, or merely its escalation. The qualitative work for the present study can lay the groundwork for understanding potential mechanisms that may also apply to non-fatal forms of IPV.

Overall, this analysis is strengthened with the mixed-methods approach. Although quantitative methods such as ARIMA modeling can serve as robust tools for examining whether specific policies can impact health outcomes, they do not necessarily capture complex phenomena in their entirety. In these instances, combining quantitative and qualitative methods with a mixed-methods design can allow researchers to contextualize and explain quantitative findings.

5 Conclusion

This study estimated the role of Georgia’s TANF diversion policy in shaping IPV. There was an observed decrease in the IPV-related morality in Georgia after the TANF diversion policy went into effect. However, policy experts, caseworkers, and TANF recipients engaged in this study revealed that the TANF diversion policy is likely fraught with limitations, despite the short-term relief it may provide to vulnerable recipients. Few studies examine the impact of social and economic policies on violence-related inequities. This study underscores the importance of paying close attention to the caveats of social policy, wherein seemingly inconsequential or previously unobserved policy elements can have critical implications for the health and well-being of families in poverty. It also highlights the importance of context: no two state-level TANF policies are alike, and state-level case studies of TANF policy components are vital for proposing tailored interventions and policy alternatives.

While this study elucidates the potential implications of TANF diversion for violence prevention, it is merely a starting point. More information can be gleaned by comparing the effects of TANF diversion policy to that of other states and states that have no TANF diversion programs in place. Future work may also consider examining the effects of the program on non-fatal IPV, as well as other forms of violence (e.g., community violence). It may also be valuable for the field to understand whether TANF diversion has differential effects across demographic groups.

Lastly, the benefits of community-engaged research for triangulating qualitative and quantitative data are widely recognized (104, 105). Policy researchers are encouraged to tap into these strengths, while broadening their definition of “experts” to account for communities beyond the research setting that frequently interact with policies of interest. Such an approach may facilitate a stronger understanding of the social mechanisms observed in natural experiments.

Data availability statement

The dataset from Phase 1 is not readily available because an application to the Georgia Department of Public Health is required to obtain the data. Deidentified qualitative data from Phase 2 can be made available upon reasonable request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to dGFzZmlhLmphaGFuZ2lyQGVtb3J5LmVkdQ==.

Ethics statement

The study involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board. Participants of Phase 2 provided their verbal informed consent to take part in this study.

Author contributions

TJ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CD: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RD: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. MDL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. BWJ: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article from the Injury Prevention Research Center at Emory (IPRCE). This article does not represent the viewpoints of the funder.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Georgia Department of Public Health for their collaboration. We are grateful to our community partners, who have facilitated our recruitment of interviewees, shared their expertise to make the project more meaningful for the populations under study, and disseminated our findings.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor UK declared a shared affiliation with the author(s) at the time of review.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fast facts: preventing intimate partner violence. (2022) [cited 2022 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html

2. Abi Nader, MA, Graham, LM, and Kafka, JM. Examining intimate partner violence-related fatalities: past lessons and future directions using U.S. National Data J Fam Viol. (2023) 38:1243–54. doi: 10.1007/s10896-022-00487-2

3. Kelly, CJ. The personal is political. (2022) [cited 2023 Mar 6]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/the-personal-is-political

4. Me too. [cited 2023 Mar 6]. Me too. Available from: https://metoomvmt.org/

5. National Network to end domestic violence (NNEDV). NNEDV (2017) [cited 2023 Mar 6]. Violence Against Women Act. Available from: https://nnedv.org/content/violence-against-women-act/

6. Goodmark, L. Reimagining VAWA: why criminalization is a failed Policy and what a non-Carceral VAWA could look like. Violence Against Women. (2021) 27:84–101. doi: 10.1177/1077801220949686

7. Beyer, K, Wallis, AB, and Hamberger, LK. Neighborhood environment and intimate partner violence: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2015) 16:16–47. doi: 10.1177/1524838013515758

8. Cochran, KA, Kashy, DA, Bogat, GA, Levendosky, AA, Lonstein, JS, Nuttall, AK, et al. Economic hardship predicts intimate partner violence victimization during pregnancy. Psychol Violence. (2023) 13:396–404. doi: 10.1037/vio0000454

9. Gillum, TL. The intersection of intimate partner violence and poverty in black communities. Aggress Violent Behav. (2019) 46:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2019.01.008

10. Hammett, JF, Halmos, MB, Parrott, DJ, and Stappenbeck, CA. COVID stress, socioeconomic deprivation, and intimate partner aggression during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14093-w

11. Machado, DB, de Siqueira Filha, NT, Cortes, F, Castro-de-Araujo, LFS, Alves, FJO, Ramos, D, et al. The relationship between cash-based interventions and violence: a systematic review and evidence map. Aggress Violent Behav. (2024) 75:101909. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2023.101909

12. Masarik, AS, and Conger, RD. Stress and child development: a review of the family stress model. Curr Opin Psychol. (2017) 13:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.008

13. Medel-Herrero, A, Shumway, M, Smiley-Jewell, S, Bonomi, A, and Reidy, D. The impact of the great recession on California domestic violence events, and related hospitalizations and emergency service visits. Prev Med. (2020) 139:106186. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106186

14. Sangeetha, J, Mohan, S, Hariharasudan, A, and Nawaz, N. Strategic analysis of intimate partner violence (IPV) and cycle of violence in the autobiographical text –when I hit you. Heliyon. (2022) 8:e09734. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09734

15. Schneider, D, Harknett, K, and McLanahan, S. Intimate partner violence in the great recession. Demography. (2016) 53:471–505. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0462-1

16. Edmonds, AT, Moe, CA, Adhia, A, Mooney, SJ, Rivara, FP, Hill, HD, et al. The earned income tax credit and intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. (2022) 37:NP12519–41. doi: 10.1177/0886260521997440

17. Jayasundara, DS, Legerski, EM, Danis, FS, and Ruddell, R. Oil development and intimate partner violence: implementation of section 8 housing policies in the Bakken region of North Dakota and Montana. J Interpers Violence. (2018) 33:3388–416. doi: 10.1177/0886260518798359

18. Klevens, J, Barnett, SBL, Florence, C, and Moore, D. Exploring policies for the reduction of child physical abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl. (2015) 40:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.013

19. Klevens, J, Luo, F, Xu, L, Peterson, C, and Latzman, NE. Paid family leave’s effect on hospital admissions for pediatric abusive head trauma. Inj Prev. (2016) 22:442–5. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041702

20. Niolon, PH, Kearns, MC, Dills, J, Rambo, K, Irving, S, Armstead, TL, et al. Preventing intimate partner violence across the lifespan: a technical package of programs, policies, and practices. Ctr Dis Control Prev. (2017):64.

21. Pilkauskas, NV, Jacob, BA, Rhodes, E, Richard, K, and Shaefer, HL. The COVID cash transfer study: The impacts of an unconditional cash transfer on the wellbeing of low-income families. University of Michigan; (2022) [cited 2023 Mar 20]. Available from: https://www.aeaweb.org/doi/10.1257/rct.5852-1.0

22. Schneider, W, Bullinger, LR, and Raissian, KM. How does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment and parenting behaviors? An analysis of the mechanisms. Rev Econ Househ. (2022) 20:1119–54. doi: 10.1007/s11150-021-09590-7

23. Spencer, RA, Livingston, MD, Woods-Jaeger, B, Rentmeester, ST, Sroczynski, N, and Komro, KA. The impact of temporary assistance for needy families, minimum wage, and earned income tax credit on Women’s well-being and intimate partner violence victimization. Soc Sci Med. (2020) 266:113355. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113355

24. Spencer, RA, Lemon, ED, Komro, KA, Livingston, MD, and Woods-Jaeger, B. Women’s lived experiences with temporary assistance for needy families (TANF): how TANF can better support Women’s wellbeing and reduce intimate partner violence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:1170. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031170

25. Tankard, M, and Iyengar, R. Economic policies and intimate partner violence prevention: emerging complexities in the literature. J Interpers Violence. (2018) 33:3367–87. doi: 10.1177/0886260518798354

26. Woods-Jaeger, B, Livingston, MD, Lemon, ED, Spencer, RA, and Komro, KA. The effect of increased minimum wage on child externalizing behaviors. Prev Med Rep. (2021) 24:101627. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101627

27. Huecker, MR, King, KC, Jordan, GA, and Smock, W. Domestic violence. Stat pearls Treasure Island (FL): Stat Pearls Publishing (2022).

28. Stubbs, A, and Szoeke, C. The effect of intimate partner violence on the physical health and health-related behaviors of women: a systematic review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2022) 23:1157–72. doi: 10.1177/1524838020985541

29. World Health Organization. Violence against women. (2021) [cited 2022 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

30. Kafka, JM, Moracco, KE, Young, BR, Taheri, C, Graham, LM, Macy, RJ, et al. Fatalities related to intimate partner violence: towards a comprehensive perspective. Inj Prev. (2021) 27:137–44. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043704

31. Kafka, JM, Moracco, K, Taheri, C, Young, BR, Graham, LM, Macy, RJ, et al. Intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration as precursors to suicide. Health. (2022) 18:101079. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101079

32. Walsh Brown, S, and Seals, J. Intimate partner problems and suicide: are we missing the violence? J Injury and Violence Res. (2019) 11:53–64. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v11i1.997

33. Gleicher, L. ICJIA | Illinois criminal justice information authority. (2021) [cited 2022 Aug 13]. Available from: https://icjia.illinois.gov/researchhub/articles/understanding-intimate-partner-violence-definitions-and-risk-factors

34. Visschers, J, Jaspaert, E, and Vervaeke, G. Social desirability in intimate partner violence and relationship satisfaction reports: an exploratory analysis. J Interpers Violence. (2017) 32:1401–20. doi: 10.1177/0886260515588922

35. Conner, DH. Financial freedom: women, money, and domestic abuse. William & Mary J Race, Gender, and Social Justice. (2014) 20:60.

36. Lin, HF, Postmus, JL, Hu, H, and Stylianou, AM. IPV experiences and financial strain over time: insights from the blinder-Oaxaca decomposition analysis. J Fam Econ Iss. (2023) 44:434–46. doi: 10.1007/s10834-022-09847-y

37. Postmus, JL, Hoge, GL, Breckenridge, J, Sharp-Jeffs, N, and Chung, D. Economic abuse as an invisible form of domestic violence: a multicountry review. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2020) 21:261–83. doi: 10.1177/1524838018764160

38. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). TANF and domestic violence: cash assistance matters to survivors. (2021) [cited 2024 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/tanf-and-domestic-violence-cash-assistance-matters-to-survivors#:~:text=Access%20to%20cash%20assistance%20programs,a%20survivor%20and%20their%20children.

39. Ahmadabadi, Z, Najman, JM, Williams, GM, Clavarino, AM, d’Abbs, P, and Abajobir, AA. Maternal intimate partner violence victimization and child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. (2018) 82:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.05.017

40. Office of Family Assistance. Temporary assistance for needy families (TANF). (2015) [cited 2022 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/programs/temporary-assistance-needy-families-tanf

41. Lens, V. TANF: what went wrong and what to do next. Soc Work. (2002) 47:279–90. doi: 10.1093/sw/47.3.279

42. Miller, KJ. Welfare and the minimum wage: are workfare participants “employees” under the fair labor standards act? Univ Chic Law Rev. (1999) 66:183–212. doi: 10.2307/1600388

43. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). Policy basics: temporary assistance for needy families. (2022) [cited 2023 Mar 20]. Available from: https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/temporary-assistance-for-needy-families

44. Moffitt, R. Welfare reform: the US experience. IFAU - Institute for Labour Market Policy Evaluation, working paper series. (2008);14. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5095868_Welfare_reform_The_US_experience

45. Dehry, I, Knowles, S, and Shantz, K. Graphical overview of state TANF policies as of July 2021. Urban Institute. (2023):18.

46. Sawafi, A, and Reyes, C. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2021) [cited 2022 Aug 13]. States must continue recent momentum to further improve TANF benefit levels. Available from: https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/states-must-continue-recent-momentum-to-further-improve-tanf-benefit

47. Shantz, K, Dehry, I, and Knowles, S. Urban Institute. (2021) [cited 2023 mar 21]. States can use TANF diversion payments to provide critical support to families in crisis. Available from: https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/states-can-use-tanf-diversion-payments-provide-critical-support-families-crisis

48. Kaplan, K, Farooqui, S, Clark, J, Dobson, E, Jefferson, R, Kelly, N, et al. Temporary assistance for needy families: sanctioning and child support compliance among black families in Illinois: study examines sanctions levied on parents receiving TANF benefits, the role of child support compliance, and the impact on the health of children in black families residing in Illinois. Health Aff. (2022) 41:1735–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00746

49. Walker, A, Spencer, RA, Lemon, E, Woods-Jaeger, B, Komro, KA, and Livingston, MD. The impact of temporary assistance for needy families benefit requirements and sanctions on maternal material hardship, mental health, and parental aggravation. Matern Child Health J. (2023) 27:1392–400. doi: 10.1007/s10995-023-03699-0

50. Wang, JSH. TANF coverage, state TANF requirement stringencies, and child well-being. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2015) 53:121–9. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.03.028

51. Wu, CF, Cancian, M, and Wallace, G. The effect of welfare sanctions on TANF exits and employment. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2014) 36:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.10.022

52. Narain, K, and Ettner, S. The impact of exceeding TANF time limits on the access to healthcare of low-income mothers. Soc Work Public Health. (2017) 32:452–60. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2017.1360817

53. Pepin, G. The effects of welfare time limits on access to financial resources: evidence from the 2010s. South Econ J. (2022) 88:1343–72. doi: 10.1002/soej.12565

54. Division of Family & Children Services. Welfare reform in Georgia annual report: Senate bill 104. (2020).

55. U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts: Georgia. (2021) [cited 2022 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/GA

56. McNamara. Need help paying bills. [cited 2023 Mar 21]. Cash assistance Georgia. Available from: https://www.needhelppayingbills.com/html/georgia_cash_assistance.html

57. Georgia Commission on Family Violence. Official website of the state of Georgia. (2022) [cited 2023 Mar 21]. Family Violence Data. Available from: https://gcfv.georgia.gov/resources/data

58. KFF. (2022) [cited 2023 Apr 15]. Poverty rate by race/ethnicity. Available from: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/poverty-rate-by-raceethnicity/

59. Georgia Coalition Against Domestic Violence (GCADV). African American/black women and intimate partner violence: Georgia fact sheet. Georgia Coalition against domestic violence (GCADV); (2019). Available from: https://gcadv.org/wp-content/uploads/AA-Factsheet_Final_DEC19.pdf

60. Fears, CS. Welfare reform: diversion as an alternative to TANF benefits. Congressional Service Research; (2006) p. 31. Available from: https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20060616_RL30230_b270bf7c3d243a9144db47248058bef65c4b2163.pdf

61. Hetling, A, Tracy, K, and Born, CE. A rose by any other name? Lump-sum diversion or traditional welfare Grant? JPolicy Prac. (2006) 5:43–59. doi: 10.1300/J508v05n02_04

62. Hetling, A, Ovwigho, PC, and Born, CE. Do welfare avoidance Grants prevent cash assistance? Soc Serv Rev. (2007) 81:609–31. doi: 10.1086/522593

63. Lacey, D, Hetling-Wernyj, A, and Born, CE. Life without welfare: Prevalence and outcomes of diversion strategies in Maryland. Baltimore, MD: Family Welfare Research and Training Group, School of Social Work, University of Maryland (2002).

64. Rosenberg, L, Derr, M, Pavetti, L, Asheer, S, Angus, MH, Sattar, S, et al. A study of states’ TANF diversion programs final report, December 2008. Mathematica Policy Res. (2008) 72

65. Peterman, A, and Roy, S. Cash transfers and intimate partner violence: A research view on design and implementation for risk mitigation and prevention. 0th ed. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (2022).

66. Palermo, T, Barrington, C, Buller, AM, Heise, L, Hidrobo, M, Ranganathan, M, et al. Global research into cash transfers to prevent intimate partner violence. Lancet Glob Health. (2022) 10:e475. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00038-9

67. Buller, AM, Peterman, A, Ranganathan, M, Bleile, A, Hidrobo, M, and Heise, L. A mixed-method review of cash transfers and intimate partner violence in low- and middle-income countries. World Bank Res Obs. (2018) 33:218–58. doi: 10.1093/wbro/lky002

68. Baranov, V, Cameron, L, Contreras Suarez, D, and Thibout, C. Theoretical underpinnings and Meta-analysis of the effects of cash transfers on intimate partner violence in low- and middle-income countries. J Dev Stud. (2021) 57:1–25. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2020.1762859

69. Braga, B, Blavin, F, and Gangopadhyaya, A. The long-term effects of childhood exposure to the earned income tax credit on health outcomes. J Public Econ. (2020) 190:104249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104249

70. Evans, WN, and Garthwaite, CL. Giving mom a break: the impact of higher EITC payments on maternal health. Am Econ J Econ Pol. (2014) 6:258–90. doi: 10.1257/pol.6.2.258

71. Moe, CA, Adhia, A, Mooney, SJ, Hill, HD, Rivara, FP, and Rowhani-Rahbar, A. State earned income tax credit policies and intimate partner homicide in the USA, 1990–2016. Inj Prev. (2020) 26:562–5. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043675

72. Cheng, TC. Impact of work requirements on the psychological well-being of TANF recipients. Health Soc Work. (2007) 32:41–8. doi: 10.1093/hsw/32.1.41

73. Kalil, A, Seefeldt, KS, and Wang, H. Sanctions and material hardship under TANF. Soc Serv Rev. (2002) 76:642–62. doi: 10.1086/342998

74. Joo Lee, B, Slack, KS, and Lewis, DA. Are welfare sanctions working as intended? Welfare receipt, work activity, and material hardship among TANF-recipient families. Soc Serv Rev. (2004) 78:370–403. doi: 10.1086/421918

75. Pavetti, L, and Kauff, J. When five years is not enough: identifying and addressing the needs of families nearing the TANF time limit in Ramsey County, Minnesota Mathematica Policy Research; (2006) [cited 2022 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.mathematica.org/publications/when-five-years-is-not-enough-identifying-and-addressing-the-needs-of-families-nearing-the-tanf-time-limit-in-ramsey-county-minnesota

76. Ivankova, NV, Creswell, JW, and Stick, SL. Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: from theory to practice. Field Methods. (2006) 18:3–20. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05282260

77. Urban Institute. Welfare rules Databook: state TANF policies as of July 2021. (2023). Available from: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/welfare-rules-databook-state-tanf-policies-july-2021#:~:text=The%20Welfare%20Rules%20Databook%20provides,policies%20from%201996%20through202021.

78. Georgia Department of Public Health (GDPH). Georgia Violent Death Reporting System (2023). Available from: https://dph.georgia.gov/GVDRS

79. Schaffer, AL, Dobbins, TA, and Pearson, SA. Interrupted time series analysis using autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models: a guide for evaluating large-scale health interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2021) 21:58. doi: 10.1186/s12874-021-01235-8

80. Jamshed, S. Qualitative research method-interviewing and observation. J Basic Clin Pharma. (2014) 5:87–8. doi: 10.4103/0976-0105.141942

81. Palinkas, LA, Horwitz, SM, Green, CA, Wisdom, JP, Duan, N, and Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Admin Pol Ment Health. (2015) 42:533–44. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

82. Fox, GL, Benson, ML, DeMaris, AA, and Van Wyk, J. Economic distress and intimate violence: testing family stress and resources theories. J Marriage Fam. (2002) 64:793–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00793.x

84. Division of Family & Children Services. Georgia department of human services. [cited 2023 Mar 21]. TANF Eligibility Requirements. Available from: https://dfcs.georgia.gov/services/temporary-assistance-needy-families/tanf-eligibility-requirements

85. Scroggy, R, Herren, K, and Kelley, D. Temporary Assistance to Needy Families Available from: https://dhs.georgia.gov/sites/dhs.georgia.gov/files/related_files/document/DFCS.TANF%205.12.pdf

86. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2022) [cited 2023 Mar 21]. State Fact Sheets: Trends in State TANF-to-Poverty Ratios. Available from: https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/state-fact-sheets-trends-in-state-tanf-to-poverty-ratios

87. Floyd, I. Georgia Budget and Policy institute. (2021) [cited 2023 Mar 21]. Georgia Can Afford to Begin to Modernize TANF and Move Past Its Racist Legacy. Available from: https://gbpi.org/georgia-can-afford-to-begin-to-modernize-tanf-and-move-past-its-racist-legacy/

88. Falk, G, and Landers, PA. The temporary assistance for needy families (TANF) block Grant: responses to frequently asked questions. Congressional Research Service; (2023) p. 23. Available from: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL32760.pdf

89. Seefeldt, KS. Serving No One Well: TANF nearly twenty years later. J Sociol Soc Welf. (2017) 44. doi: 10.15453/0191-5096.3849

90. Cerda-De La, OB, Cerda-Molina, AL, Mayagoitia-Novales, L, De La Cruz-López, M, Biagini-Alarcón, M, Hernández-Zúñiga, EL, et al. Increased cortisol response and low quality of life in women exposed to intimate partner violence with severe anxiety and depression. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:8017. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.898017

91. Goldberg, X. Female survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) and mental health In: C Martin, VR Preedy, and VB Patel, editors. Handbook of anger, aggression, and violence. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2022). 1–23.

92. Schwab-Reese, LM, Peek-Asa, C, and Parker, E. Associations of financial stressors and physical intimate partner violence perpetration. Inj Epidemiol. (2016) 3:6. doi: 10.1186/s40621-016-0069-4

93. Yim, IS, and Kofman, YB. The psychobiology of stress and intimate partner violence. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2019) 105:9–24. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.08.017

94. Nahar, S, and Cronley, C. Transportation barriers among immigrant women experiencing intimate partner violence. Transp Res Rec. (2021) 2675:861–9. doi: 10.1177/03611981211004587

95. Tur-Prats, A. Unemployment and intimate partner violence: a cultural approach. J Econ Behav Organ. (2021) 185:27–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2021.02.006

96. Arroyo, K, Lundahl, B, Butters, R, Vanderloo, M, and Wood, DS. Short-term interventions for survivors of intimate partner violence: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2017) 18:155–71. doi: 10.1177/1524838015602736

97. Hémono, R, Mnyippembe, A, Kalinjila, A, Msoma, J, Prata, N, Dow, WH, et al. Risks of intimate partner violence for women living with HIV receiving cash transfers: A qualitative study in Shinyanga, Tanzania. AIDS Behav. (2023) 27:2741–50. doi: 10.1007/s10461-023-03997-2

98. Shrivastava, A, and Thompson, GA. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). (2015) [cited 2023 Apr 8]. TANF cash assistance should reach millions more families to lessen hardship | Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Available from: https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/tanf-cash-assistance-should-reach-millions-more-families-to-lessen

99. Floyd, I, Pavetti, L, Meyer, L, Sawafi, A, and Schott, L. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2021) [cited 2022 Aug 14]. TANF policies reflect racist legacy of cash assistance. Available from: https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/tanf-policies-reflect-racist-legacy-of-cash-assistance

100. Bergel, J.The Pew Charitable Trusts. (2020). States raid fund meant for needy families to pay for other programs. [cited 2023 Apr 4]. Available from: https://pew.org/3fWqKNN

101. Schott, LCenter on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). (2016) Why TANF is not a model for other safety net programs. [cited 2023 Mar 20]. Available from: https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/why-tanf-is-not-a-model-for-other-safety-net-programs

102. Toft, J. History matters: racialized motherhoods and neoliberalism. Soc Work. (2020) 65:225–34. doi: 10.1093/sw/swaa021

103. Georgia Coalition Against Domestic Violence (GCADV). The basics. Available from: https://gcadv.org/public-policy/

104. Beames, JR, Kikas, K, O’Gradey-Lee, M, Gale, N, Werner-Seidler, A, Boydell, KM, et al. A new Normal: integrating lived experience into scientific data syntheses. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:763005. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.763005

105. Wasti, SP, Simkhada, P, Van Teijlingen, E, Sathian, B, and Banerjee, I. The growing importance of mixed-methods research in health. Nepal J Epidemiol. (2022) 12:1175–8. doi: 10.3126/nje.v12i1.43633

106. Staggs, SL, Long, SM, Mason, GE, Krishnan, S, and Riger, S. Intimate partner violence, social support, and employment in the post-welfare reform era. J Interpers Violence. (2007) 22:345–67. doi: 10.1177/0886260506295388