95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 23 February 2024

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1250085

This article is part of the Research Topic Insights In Sleep, Behavior and Mental Health View all 4 articles

A commentary has been posted on this article:

Commentary: Sleep quality, quality of life, fatigue, and mental health in COVID-19 post-pandemic Türkiye: a cross-sectional study

Aim: This study explores the predictors and associated risk factors of sleep quality, quality of life, fatigue, and mental health among the Turkish population during the COVID-19 post-pandemic period.

Materials and methods: A cross-sectional survey using multi-stage, stratified random sampling was employed. In total, 3,200 persons were approached. Of these, 2,624 (82%) completed the questionnaire package consisting of socio-demographic information, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the WHO Quality of Life Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF), Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS), Patients Health Questionnaire (PHQ-15), GAD-7 anxiety scale, and the 21-item Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale (DASS-21).

Results: Significant differences between genders were found regarding socio-demographic characteristics (p < 0.01). Using PHQ-15 for depressive disorders, significant differences were found between normal and high severity scores (≥ 10), regarding age group (p < 0.001), gender (p = 0.049), educational level (p < 0.001), occupational status (p = 0.019), cigarette smoking (p = 0.002), waterpipe-narghile smoking (p = 0.039), and co-morbidity (p = 0.003). The WHOQOL-BREF indicated strong correlations between public health, physical health, psychological status, social relationships, environmental conditions, and sleep disorders (p < 0.01). Furthermore, comparisons of the prevalence of mental health symptoms and sleeping with PHQ-15 scores ≥ 10 (p = 0.039), fatigue (p = 0.012), depression (p = 0.009), anxiety (p = 0.032), stress (p = 0.045), and GAD-7 (p < 0.001), were significantly higher among the mental health condition according to sleeping disorder status. Multiple regression analysis revealed that DASS21 stress (p < 0.001), DASS21 depression (p < 0.001), DASS21 anxiety (p = 0.002), physical health (WHOQOL-BREF) (p = 0.007), patient health depression-PHQ-15 (p = 0.011), psychological health (WHOQOL-BREF) (p = 0.012), fatigue (p = 0.017), and environmental factors (WHOQOL-BREF) (p = 0.041) were the main predictor risk factors associated with sleep when adjusted for gender and age.

Conclusion: The current study has shown that sleep quality was associated with the mental health symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, and fatigue. In addition, insufficient sleep duration and unsatisfactory sleep quality seemed to affect physical and mental health functioning.

According to the 2023 report by the WHO, the COVID-19 pandemic, which started in November 2019, produced over 760 million confirmed cases worldwide, and over 6.9 million reported deaths as of August 2023. Since the beginning of the pandemic, significant measures have been taken across the world, such as travel restrictions and home confinements, to control the pandemic. With the progress achieved in the management of the pandemic through the year 2021, the restrictions were gradually lifted. However, more than 3 years since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, serious impacts on many aspects of public health are still being observed, including sleep disturbances and mental health symptoms, along with various physiological symptoms (1, 2). Therefore, it is important to explore how the pandemic situation affected public health in order to reduce negative consequences and promote changes in lifestyles and improvements in overall health and life quality among the population. However, pandemic conditions have left an ongoing impact on the physical and mental health of many individuals regardless of whether they had the infection or not. The current research focuses particularly on sleep quality, quality of life, and several mental health symptoms during the aftermath of pandemic restrictions among the Turkish population.

Sleep disturbances, such as difficulty falling asleep or maintaining sleep, are quite common in many countries around the world (3, 4). Since poor sleep quality is linked to many medical and psychological disorders including obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and depression, and has a direct effect on life quality, investigating these effects of sleep quality is important (5–8). Several neurocognitive dysfunctions such as attention deficits and cognitive performance impairment, as well as psychological disorders such as stress, depression, anxiety, and impulse control problems, are related to sleep disturbances (5, 9). If untreated, such sleep-related deficits may lead to further potentially health-threatening consequences such as increased risk of cardiovascular diseases (4). Furthermore, disturbed sleep quality also has important consequences on quality of life, as it can lead to daytime impairments that affect people's performance at work and quality of social life (4, 5).

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, multiple studies have shown increased sleep disturbances due to factors related to the pandemic [8, 1, 9, (10)]. A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating changes in the quality of sleep and disturbances of sleep among the general population prior to and during the COVID-19 lockdown has revealed a decline in sleep quality and sleep efficiency, and an increase in sleep disturbances (11). The worldwide pandemic created an unpredictable, stressful, anxiety-provoking environment, with fear of infection and financial concerns added to social isolation and other negative consequences of lockdowns (12–14). Home confinement also resulted in increased screen time as many individuals turned to the media and the internet for information on the pandemic or to distract themselves from the stressful situation. These psychological and physical conditions may have had a negative impact on the quality of sleep experienced by the general population (13, 15–17).

In the initial phases of the pandemic, people with mental health problems in the general population were reported to be struggling with higher levels of depression, anxiety, stress, and fear symptoms (6, 12, 18–24). Indeed, several studies conducted in various countries have reported the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of the general population (1, 14). Multiple studies have also shown associations among depression, anxiety, stress, and negative changes in sleep (13, 15, 25, 26).

Although the number of infection cases has dramatically declined and most of the world has lifted restrictions concerning COVID-19, it is still important to assess the long-term health consequences of experiencing the pandemic among the general population.

Accordingly, the objective of this study is to examine the predictors and associated risk factors of sleep quality, quality of life, fatigue, and mental health among the Turkish population during the post-COVID period. For this purpose, several demographic variables, habits, and living conditions were explored as predictor variables of the outcome health variables. In addition, based on the literature reviewed, poor sleep quality is expected to be correlated with negative mental health symptoms, fatigue, and poor quality of life.

The research used a cross-sectional multi-center-based survey, conducted among the urban and rural populations of Istanbul, including men and women (aged 20 years and over). The sample size calculations were derived from the following parameters: a margin of error of 2.0% with a confidence level of 99%, and an estimated sample proportion of 25% to be considered. Accordingly, a multi-stage total of 3,200 individuals were approached. A total of 2,624 (82%) participants completed the questionnaire between 1 January and 31 December 2022.

The WHOQOL-BREF (27) has 26 questions consisting of four domains: physical health, psychological status, social relationships, and environmental conditions. The WHOQOL-BREF has been shown to have good reliability and validity in a number of different populations.

The PHQ-15 is a screening tool for depressive disorders (28). The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the PHQ-15 exhibited satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.78). Total scores can range from 0 to 30, resulting in the following categories: 0–4 none, 5–9 mild, 10–14 moderate, and 15–30 severe. The recognized cut-off value is 10.

The 21-item DASS-21 by Lovibond and Lovibond (24) was used to assess depression, anxiety, and stress. Cronbach's alpha internal consistency coefficient was found as α = 0.86 for the depression subscale, α = 0.84 for the anxiety subscale, and α = 0.80 for the stress subscale in the current study. The scale categorizes the participants into five categories: normal, mild, moderate, severe, and very severe.

The GAD-7 is a simple instrument containing seven items that track anxiety symptoms (29). The reliability coefficient of Cronbach's α for the overall GAD-7 scale is 0.86, which is greater than the recommended value of 0.80, suggesting excellent reliability. The total scores range from 0 to 21 and were categorized as follows: minimal/no anxiety (0–4), mild (7–9, 13, 15), moderate (11, 12, 14, 16, 17), and severe (1, 18–23).

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was developed by Buysse et al. (30). The reliability and validity of PSQI in the current study population was 0.84. The categorization of the total scores of PSQI is as follows: PSQI ≤ 5= “Good sleep quality,” PSQI 6–8= “Average sleep,” and PSQI ≥ 9 = “Poor sleep.”

The Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS), developed by Michielsen et al. (31), is a 10-item self-report questionnaire intended to assess general fatigue. The FAS displayed good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.91). A total FAS score ranging from 10 to 21 indicates no fatigue (normal) and FAS scores ranging from 22 to 50 indicate fatigue.

SPSS v25 was utilized to analyze the present data, and percentages were computed for each categorical variable. To assess the normal distribution of the data, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and normality plots were utilized. Student's t-test was used to ascertain the significance of differences between mean values. The chi-square test was used to determine significant differences between categorical variables. A multivariate stepwise regression analysis was performed to predict potential risk factors (determinants) for sleep and mental health. Furthermore, the multiple stepwise regression analysis was used to control for the effects of gender and age. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and p < 0.01 was considered significant.

A significant difference was found between men and women in educational level, occupational status, monthly income, place of residence as urban or rural, number of rooms, and number of family members (p < 0.01) (Table 1). The educational status ranged from primary school to university degree and postgraduate levels. In terms of occupational status, the majority were in professional/sedentary and clerical occupation categories.

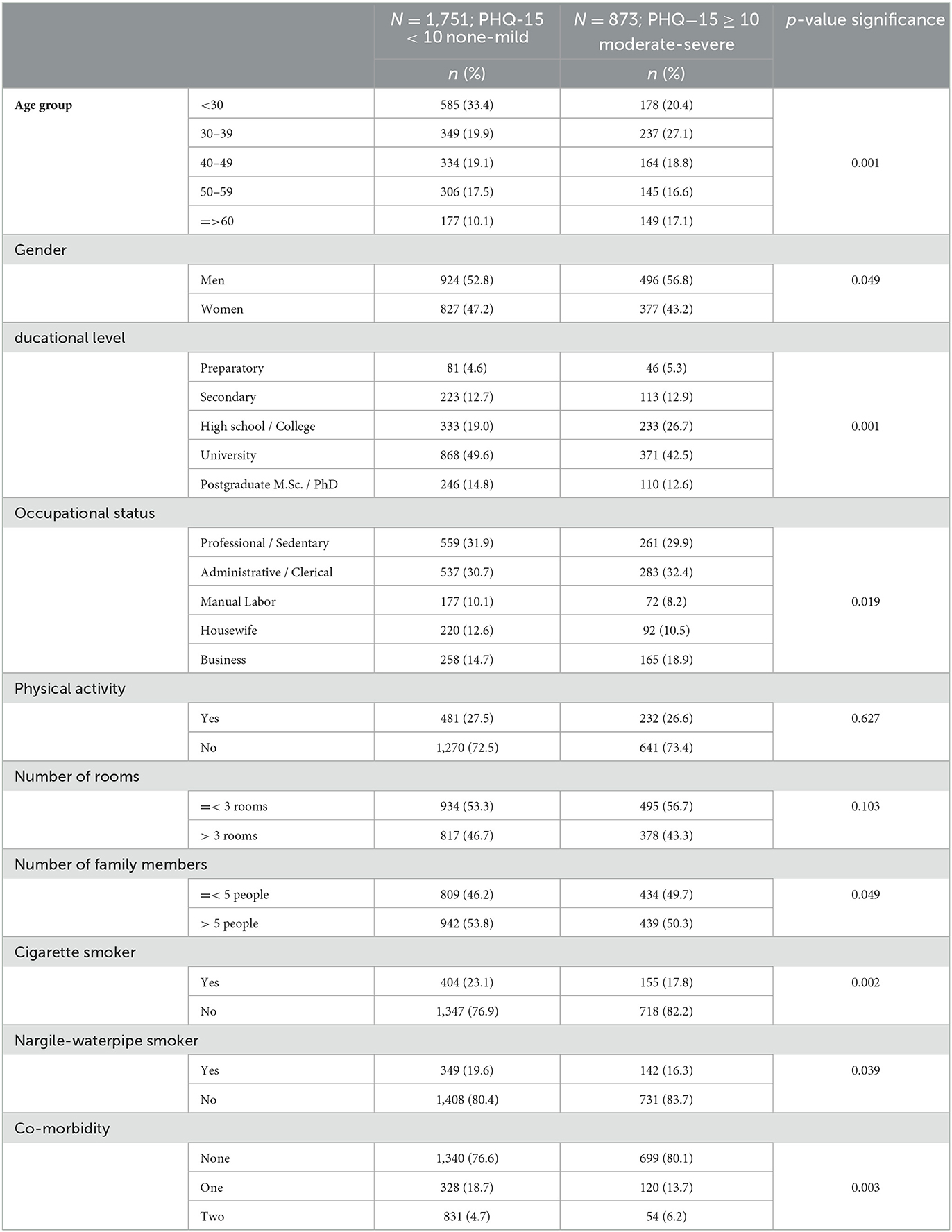

Table 2 provides participants' characteristics, lifestyle behavior, and level of depression using PHQ-15, and the results indicate significant differences between normal and high severity regarding age group (p < 0.001), gender (p = 0.049), educational level (p < 0.001), occupational status (p = 0.019), smoking cigarettes (p = 0.002), waterpipe-narghile smoking (p = 0.039), and co-morbidity (p = 0.003). Smoking cigarettes was reported by 25% of the participants, and narghile waterpipe use was reported by 20%.

Table 2. Participants' characteristics, lifestyle behavior, and depression using PHQ-15 tools (N = 2,624).

Table 3 shows the prevalence of mental health symptoms by gender. The prevalence of depression was 30% among women and 20% among men. The prevalence of mental health symptoms is significantly higher among women than men regarding depression (p < 0.001), anxiety (p < 0.001), stress (p = 0.031), GAD-7 (p = 0.030), and PSQI (p = 0.010).

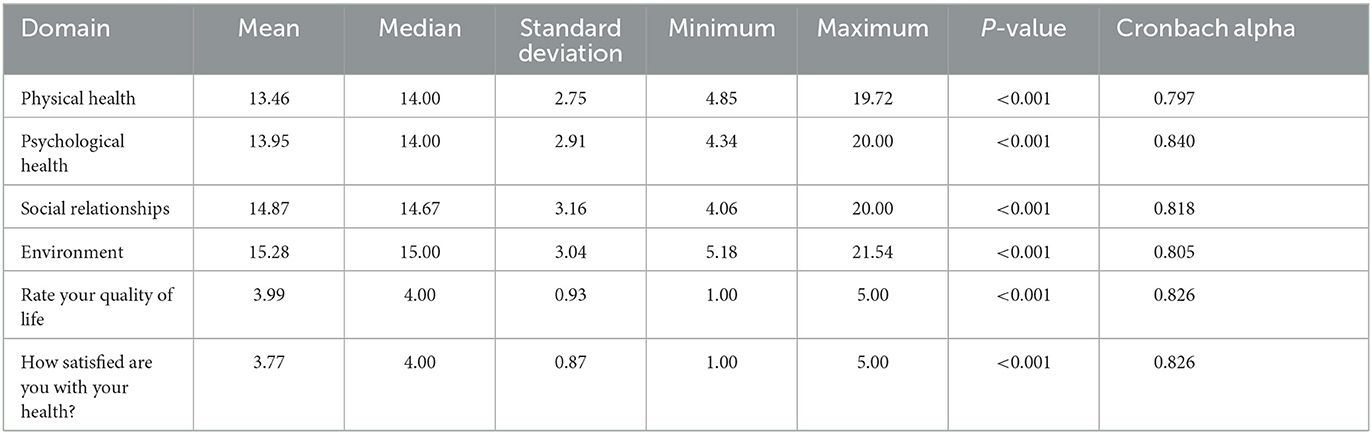

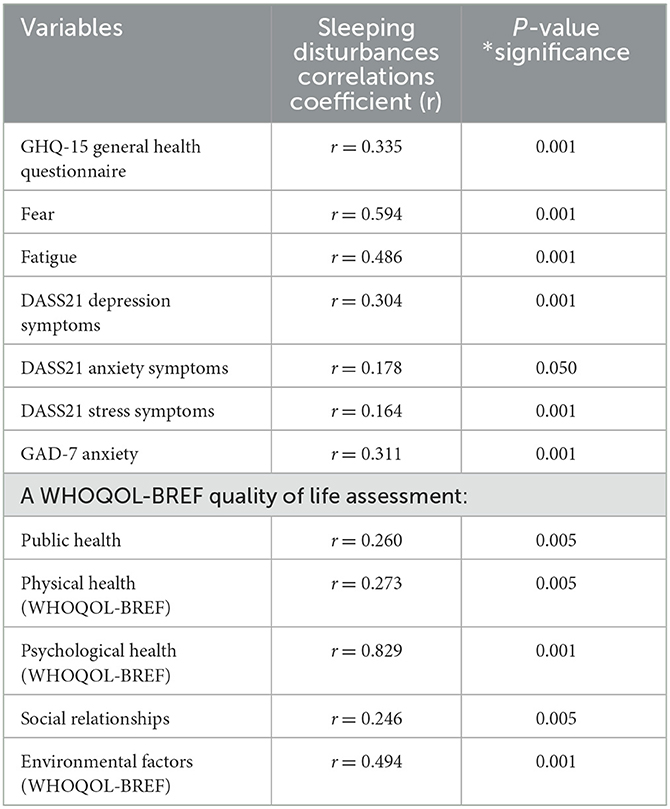

Table 4 presents the quality of life descriptive with the test for normality of distribution and reliability of the domains. The WHOQOL-BREF domains were all normally distributed. Furthermore, Table 5 reveals higher statistically significant positive correlations between WHOQOL-BREF public health, physical health, psychological status, social relationships, environmental conditions, and sleeping disorders (p < 0.01). The correlation between WHOQOL-BREF physical health and sleeping disorders was r = 0.40, p < 0.01.

Table 4. Quality of life descriptive statistics with the test for normality of distribution and reliability of the domains.

Table 5. Pearson's Correlation between sleeping disturbances and mental health parameters (N = 2,624).

Table 6 shows the prevalence of mental health symptoms and sleeping disorders. The prevalence of PHQ-15 scores ≥ 10 was 10% among people with sleeping disorders and 5% among people without sleeping disorders. The prevalence of PHQ-15 scores ≥ 10 was 10% among people with sleeping disorders and 5% among people without sleeping disorders. As can be seen, the prevalence of PHQ-15 ≥ 10 scores (p = 0.039), fatigue (p = 0.012), depression (p = 0.009), anxiety (p = 0.032), stress (p = 0.045), and GAD-7 (p < 0.001) were significantly higher among the mental health condition compared to sleeping disorder status.

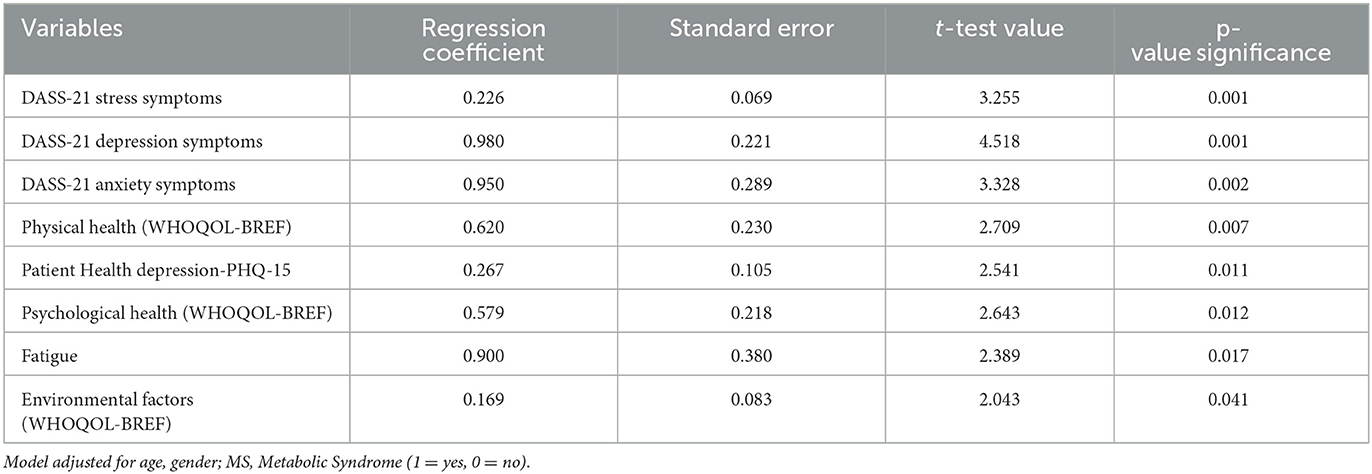

Table 7 shows the relationships between sleeping disorders and mental health using multivariate stepwise regression analysis. It can be seen from this table that DASS21 stress (p < 0.001), DASS21 depression (p < 0.001), DASS21 anxiety (p = 0.002), physical health (WHOQOL-BREF) (p = 0.007), patient health depression-PHQ-15 (p = 0.011), psychological health (WHOQOL-BREF) (p = 0.012), fatigue (p = 0.017), and environmental factors (WHOQOL-BREF) (p = 0.041) were considered as the main predictor risk factors associated with sleep quality after adjusting for age and gender.

Table 7. The relationships between sleeping disorders and mental health using multivariate stepwise regression analysis (N = 2,624).

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the management and prevention of the negative health consequences of the pandemic have become a major concern. Globally, a significant emphasis has been placed on addressing and preventing the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on health since its onset, and this has emerged as a significant public health priority. Further research into the ongoing effects of COVID-19 is still needed to provide better insight into COVID-19-related physical and mental symptoms, and for the development of preventive measures and programs to promote healthy living (12, 18, 19, 23, 24). The findings of the current study contribute to this process by showing that negative health consequences of COVID-19 are still present in major populations.

The current research focused particularly on sleep quality, quality of life, fatigue, and mental health during the post-COVID-19 period. The findings indicated the prevalence of mental health symptoms and sleeping disorders among the Turkish population during the aftermath period of the pandemic. In addition, depression, stress, anxiety, physical and psychological health, fatigue, and environmental factors are shown as the main predictors of sleep quality in the current findings. The current findings concur with previous multinational research showing that people who experience increased symptoms of depression were more vulnerable to experiencing psychological burdens because of the COVID-19 pandemic (32). Furthermore, studies have reported increased depression, anxiety, and stress, and poor sleep quality (16, 33, 34), as well as increased mental and physical health conditions related to COVID-19 exposure among Chinese populations (13, 17).

COVID-19 has created considerable amounts of fear, fatigue, depression, anxiety, and stress in many communities, and is considered the greatest pandemic in centuries (12–14, 17, 23, 24, 32). Recently, studies conducted on populations in Istanbul, Turkey, found a high level of fatigue, stress, and fear associated with COVID-19 (12, 14, 24, 25). More recently, a systematic review and meta-analysis (11) comparing the effects of COVID-19 before and during lockdown, has shown a significant negative impact of the lockdown period in terms of changes in sleep quality among the general population. Consistently, the present study indicates the prevalence of poor sleep quality among Turkish populations and provides supporting evidence for the link between mental health symptoms and sleep disturbances. Studies examining associations between sleep quality and mental health symptoms often discuss the unclear direction of causality (3, 16). While mental health problems can result in the deterioration of sleep, on the other hand, sleep deprivation may lead to hormonal changes that can contribute to the development of mental health problems such as depression and anxiety. The present study suggests that the prevalence of sleep disorders remains high in the aftermath of the pandemic, and taking measures to improve sleep quality among the population should be considered a public health priority. Considering the main predictors and risk factors addressed in this research, implementing interventions to improve sleep quality among the general population could yield positive effects on both physical and mental health.

We are aware that our study has some limitations. First, we utilized a cross-sectional design, which may limit the ability to detect causal relationships. Second, the study was limited by the instruments employed to assess the variables. Our findings were derived from self-report assessments, and the assessment of mental health states did not involve clinical evaluation. The potential for recall bias and underreporting should therefore be considered. Third, since the study was based on self-administrated surveys, there is a possibility of selection bias in including participants based on their availability. On the other hand, one of the considerable strengths of the current study is its inclusion of a large sample size, enabling a thorough investigation that contributes valuable evidence supporting the link between sleep quality and mental health symptoms in a post-COVID-19 population.

The current study revealed the prevalence of mental health symptoms (such as depression, stress, anxiety, and fatigue) among the general Turkish population who experienced the social trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study provided supporting evidence concerning the association between sleep quality and mental health symptoms and indicated the substantial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on this association. The findings show that, while negative mental health significantly contributes to poor sleep quality, insufficient sleep duration and unsatisfactory sleep quality have a negative impact on physical and mental health functioning. The current findings highlight the importance of providing adequate treatment and prevention strategies for sleep disorders as a public health concern, and this may help reduce the likelihood of the worsening, or onset, of several mental health disorders among the population.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Istanbul Medipol University, Institutional Review Board (Research Protocol IRB# E.10840098-604.01.01-0.14180 and IRB# E. 10840098-604.01.01- 1328). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

AB, EM, and MT contributed to the conception, design, data collection, organization, statistical analysis, wrote the first draft of the article, they also contributed to the interpretation of the data, and writing and critical revision of the approved the final version of the manuscript. AV and TJ contributed to the conception, wrote the first draft of the article, contributed to the interpretation of the data and writing, and undertook critical revisions of the approved final version of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

The authors would like to thank the Istanbul Medipol University for their support.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) AB declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Dos Santos Alves Maria G, de Oliveira Serpa AL, Ferreira CDMC, de Andrade VD, Ferreira ARH, de Souza Costa D, et al. Impacts of mental health in the sleep pattern of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. J Affect Disord. (2023) 323:472–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.11.082

2. Taheri M, Irandoust K, Reynoso-Sánchez LF, Muñoz-Helú H, Cruz-Morales KN, Torres-Ramírez R, et al. Effects of home confinement on physical activity, nutrition, and sleep quality during the COVID-19 outbreak in amateur and elite athletes. Front Nutr. (2023) 10:1143340. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1143340

3. de Souza Lopes C, Robaina JR, Rotenberg L. Epidemiology of Insomnia: Prevalence and Risk Factors. In:Sahoo S, , editor. In Can't Sleep? Issues of Being an Insomniac Shanghai: In Tech (2012), 1–21.

4. Mollayeva T, Thurairajah P, Burton K, Mollayeva S, Shapiro CM, Colantonio A. The pittsburgh sleep quality index as a screening tool for sleep dysfunction in clinical and non-clinical samples: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. (2016) 25:52–73. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.01.009

5. Manzar MD, BaHammam AS, Hameed UA, Spence DW, Pandi-Perumal SR, Moscovitch A, et al. Dimensionality of the pittsburgh sleep quality index: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2018) 16:1–22. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0915-x

6. Franceschini C, Musetti A, Zenesini C, Palagini L, Scarpelli S, Quattropani MC, et al. Poor sleep quality and its consequences on mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:3072. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.574475

7. Taheri M, Irandoust K. The exercise-induced weight loss improves self-reported quality of sleep in obese elderly women with sleep disorders. Sleep Hypn. (2018) 20:54–9. doi: 10.5350/Sleep.Hypn.2017.19.0134

8. Taheri M, Irandoust K. The relationship between sleep quality and lifestyle of the elderly. Iran J Ageing. (2020) 15:188–99. doi: 10.32598/sija.13.10.110

9. Bener A, Griffiths MD, Cahit Barisik C, Inan FC, Morg E. Impacts of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health: depression, anxiety, stress and fear among adult population in Turkey. Arch Clin Biomed Res. (2022) 6:1010–20. doi: 10.26502/acbr.50170312ee

10. Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 89:531–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048

11. Limongi F, Siviero P, Trevisan C, Noale M, Catalani F, Ceolin C, et al. Changes in sleep quality and sleep disturbances in the general population from before to during the COVID-19 lockdown: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 14:1166815. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1166815

12. Morgul E, Bener A, Atak M, Akyel S, Aktaş S, Bhugra D, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and psychological fatigue in Turkey. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2021) 10:20764020941889. doi: 10.1177/0020764020941889

13. Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 288:112954. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954

14. Uysal B, Görmez V, Eren S, Morgül E, Öcal NB, Karatepe HT, et al. Living with COVID-19: Depression, anxiety and life satisfaction during the new normal in Turkey. J Cogn Psychother. (2021) 10:257. doi: 10.5455/JCBPR.62468

15. Salfi F, Lauriola M, D'Atri A, Amicucci G, Viselli L, Tempesta D, et al. Demographic, psychological, chronobiological, and work-related predictors of sleep disturbances during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:11416. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90993-y

16. Gupta R, Grover S, Basu A, Krishnan V, Tripathi A, Subramanyam A, et al. Changes in sleep pattern and sleep quality during COVID-19 lockdown. Indian J Psychiatry. (2020) 62:370. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_523_20

17. Sun QM, Qin QS, Chen BX, Shao RF, Zhang JS, Li Y. Stress, anxiety, depression and insomnia in adults outside Hubei province during the COVID-19 pandemic. Zhonghua Yi Xue za Zhi. (2020) 100:3419–24. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20200302-00557

18. Khan AA, Lodhi FS, Rabbani U, Ahmed Z, Abrar S, Arshad S, et al. Impact of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on psychological well-being of the Pakistani general population. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:564364. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.564364

19. Elhadi M, Alsoufi A, Msherghi A, Alshareea E, Ashini A, Nagib T, et al. Psychological health, sleep quality, behavior, and internet use among people during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:632496. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.632496

20. Zavlis O, Butter S, Bennett K, Hartman TK, Hyland P, Mason L, et al. How does the COVID-19 pandemic impact on population mental health? A network analysis of COVID influences on depression, anxiety and traumatic stress in the UK population. Psychol Med. (2021) 16:1–9. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/8xtdr

21. Liu C, Liu D, Huang N, Fu M, Ahmed JF, Zhang Y, et al. The combined impact of gender and age on post-traumatic stress symptoms, depression, and insomnia during COVID-19 outbreak in China. Front Public Health. (2021) 21:620023. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.620023

22. Pan KY, Kok AAL, Eikelenboom M, Horsfall M, Jörg F, Luteijn RA, et al. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with and without depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders: a longitudinal study of three Dutch case-control cohorts. Lancet Psychiatry. (2021) 8:121–9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30491-0

23. Casagrande M, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Forte G. The enemy who sealed the world: effects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population. Sleep Med. (2020) 75:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.011

24. Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2 Edn. Sydney: Psychology Foundation (1995).

25. Bener A, Morgul E, Atak M, Barişik CC. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic disease exposed with mental health in Turkey. Int J Clin Psych Mental Health. (2020) 8:16–9. doi: 10.12970/2310-8231.2020.08.04

26. Taheri M, Esmaeili A, Irandoust K, Mirmoezzi M, Souissi A, Laher I, et al. Mental health, eating habits and physical activity levels of elite Iranian athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Sports. (2023) 38:527–33. doi: 10.1016/j.scispo.2023.01.002

27. WHOQOL-BREF. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. WHOQOL Group Psychol. Med. (1998) 28:551–8. doi: 10.1017/S0033291798006667

28. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. (2022) 64:258–66. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00008

29. Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. (2008) 46:266–74. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

30. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. (1989) 28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

31. Michielsen HJ, De Vries J, Van Heck GL. Psychometric qualities of a brief self-rated fatigue measure: the fatigue assessment scale. J Psychosom Res. (2003) 54:345–52. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00392-6

32. Brailovskaia J, Cosci F, Mansueto G, Miragall M, Herrero R, Baños RM, et al. The association between depression symptoms, psychological burden caused by COVID-19 and physical activity: an investigation in Germany, Italy, Russia, and Spain. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 295:113596. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113596

33. Verma S, Mishra A. Depression, anxiety, and stress and socio-demographic correlates among general Indian public during COVID-19. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2020) 66:756–62. doi: 10.1177/0020764020934508

34. World Health Organization. Corona Virus Disease (COVID-2019) Situation Reports. (2023) Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19-situation-reports (accessed March 30, 2023).

Keywords: COVID-19, sleep quality, quality of life, mental health, depression, anxiety, stress

Citation: Bener A, Morgul E, Tokaç M, Ventriglio A and Jordan TR (2024) Sleep quality, quality of life, fatigue, and mental health in COVID-19 post-pandemic Türkiye: a cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 12:1250085. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1250085

Received: 29 June 2023; Accepted: 02 February 2024;

Published: 23 February 2024.

Edited by:

Colin Shapiro, University of Toronto, CanadaCopyright © 2024 Bener, Morgul, Tokaç, Ventriglio and Jordan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abdulbari Bener, YWJkdWxiYXJpLmJlbmVyQGlzdGFuYnVsLmVkdS50cg==; YWJlbmVyOTlAeWFob28uY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.