94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health, 29 September 2023

Sec. Public Health Policy

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.957653

This article is part of the Research TopicSystems thinking: strengthening health systems in practiceView all 11 articles

Introduction: Interest in applying systems thinking (ST) in public health and healthcare improvement has increased in the past decade, but its practical use is still unclear. ST has been found useful in addressing the complexity and dynamics of organizations and welfare systems during periods of change. Exploring how ST is used in practice in national policy programs addressing complex and ill-structured problems can increase the knowledge of the use and eventually the usefulness of ST during complex changes. In ST, a multi-level approach is suggested to coordinate interventions over individual, organizational, and community levels, but most attempts to operationalize ST focus on the individual level. This study aimed to investigate how ST is expressed in policy programs addressing wicked problems and describe the specific action strategies used in practice in a national program in Sweden, using a new conceptual framework comprising ST principles on the organizational level as an analytical tool. The program addresses several challenges and aims to achieve systems change within women's healthcare.

Methods: The case study used a rich set of qualitative, longitudinal data on individual, group, and organizational levels, collected during the implementation of the program. Deductive content analysis provided narrative descriptions of how the ST principles were expressed in actions, based on interviews, observations, and archival data.

Results: The results showed that the program management team used various strategies and activities corresponding to organizational level ST. The team convened numerous types of actors and used collaborative approaches and many different information sources in striving to create a joint and holistic understanding of the program and its context. Visualization tools and adaptive approaches were used to support regional contact persons and staff in their development work. Efforts were made to identify high-leverage solutions to problems influencing the quality and coordination of care before, during, and after childbirth, solutions adaptable to regional conditions.

Discussion/conclusions: The organizational level ST framework was useful for identifying ST in practice in the policy program, but to increase further understanding of how ST is applied within policy programs, we suggest a multi-dimensional model to identify ST on several levels.

Many public health and social issues are complex and so are the interventions that can affect them. Such multi-dimensional issues often represent ‘wicked problems', i.e., problems that involve multiple sectors, multiple organizational levels, and many actors, and that are dynamic and difficult to define (1–4). This complexity makes it difficult to implement, evaluate, and scale up health interventions (5). How wicked problems should be addressed has been debated as most of the ill-structured and wicked problems defy solutions (6, 7). Usually, they are addressed as if they could be solved, or by reducing them into well-structured problems to control them. An alternative could be to use a coping strategy that focuses on the process of repeatedly trying to resolve the wicked problem (8). Soft-law initiatives, i.e., non-legislative modes of policymaking based on voluntary cooperation, have been a way to deal with such complex policy problems, especially in the Nordic countries (9). However, the focus on the process, the aim to incorporate multiple and competing perspectives on the problem, and the continuously changing contextual conditions make it difficult to lead such soft-law initiatives.

An approach based on systems thinking (ST) can be useful for tackling complex issues when leading soft-law initiatives (2, 10). ST has also been suggested as an aid when identifying high-leverage solutions that can improve multiple health outcomes (11). The interest in applying ST in public health and healthcare improvement has increased in the past decade (12–14). Even so, relatively few applied studies focus on ST within public health, and more research is needed to understand how ST is used in this field (15–17).

Systems thinking is a theoretical approach found to be useful in addressing the complexity and dynamics of organizations and welfare systems when trying to change a current situation (2, 10, 11, 13, 18). ST has multiple origins from diverse scientific traditions, and it involves a wide range of terminologies, theories, and tools (10). Unlike reductionist approaches, ST considers the complexity of a phenomenon and its context, e.g., that interventions are interdependent on each other and on the environment (19–21). A recent review shows that most articles published on ST are conceptual (17). Thus, there is a need for more knowledge about how ST can be put into action within public health and healthcare improvement (18), and the need for further studies and development of practical applications is highly relevant (10, 17).

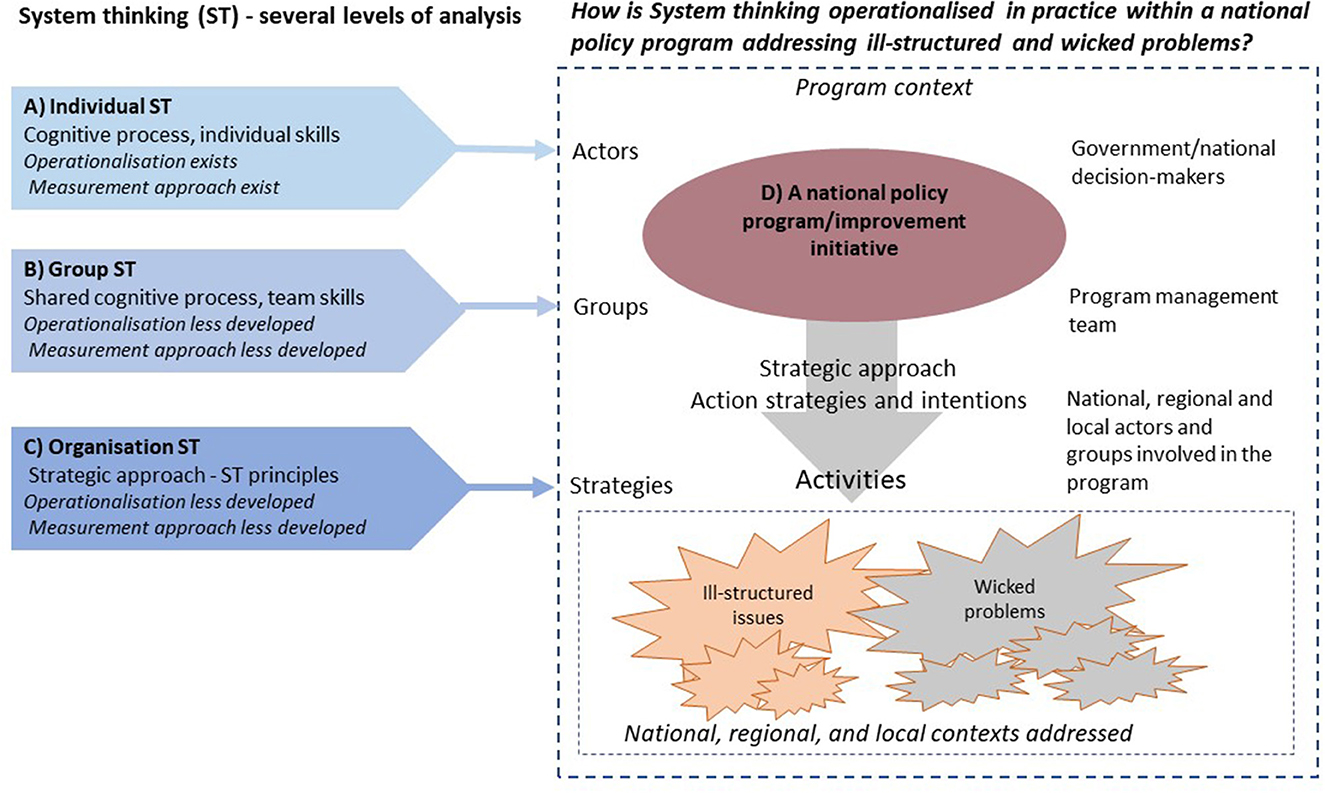

There are challenges in studying how ST is manifested in practice. At the same time, identifying how ST can be expressed in actions and strategies is an important step in building knowledge about the practical application of ST in public health (22) and the mechanisms behind the effects of quality improvement initiatives (23). ST emphasized the coordination of interventions across multiple levels of change, e.g., individual, organizational, and community levels (24). This “multi-level” approach is in line with what is needed when national policy programs address ill-structured or wicked problems in public health and healthcare.

Most attempts to operationalize and measure ST focus on the individual level relating ST to individuals' understandings, abilities, skills, and cognitive processes. Studies on ST emphasize individuals' knowledge and abilities, for example, to be able to understand how the system is organized, managed, and led; to understand and be able to manage system stakeholders and networks; and to have the ability to conceptualize, model, and understand dynamic change (24–26) as important to facilitate change. To assess ST on the individual level, system attributes have been used when investigating and comparing ST preferences with preferences for reductionism (27–29). There are also attempts made to define and measure ST as a cognitive process (30). Richmond's taxonomy of “thinking skills” (31, 32) has been used in several studies [e.g., (33, 34)], where, for example, more complex ST skills have been linked to better decision-making (33). Measurement of ST on the individual level mostly relies on the subjective judgment of one's experiences or preferences, sometimes in relation to described fictive situations.

Implementation of policy programs typically involves many different types of actors, and, usually, there is a team responsible for the program, which potentially can benefit from ST to address wicked problems and the dynamic changes inherent in them. Some indications of the use of ST on a group level have been described in the literature. Different people have different objectives and perspectives, which affects the situation at hand (35, 36). Addressing a complex and problematic situation requires understanding multiple perspectives, and Soft Systems Methodology is one ST approach designed to tackle diffuse real-world problems (37). Mental models of managerial teams' ST have been related to organizational learning processes, especially when the teams' shared understandings and action strategies change (38). More recently, factors that foster collaborative ST in teams have been studied (39). Studies of ST at the group level focus on a mixed social and cognitive process. Concepts described in other research fields, such as shared cognition [e.g., (40)], team mental modeling [e.g., (41)], sense-making as a social process [e.g., (42, 43)], and team learning (44), can aid the understanding of the use of ST in groups. Finding ways to achieve shared cognition and team mental models among key actors involved in policy programs is important to achieve systems change (45, 46).

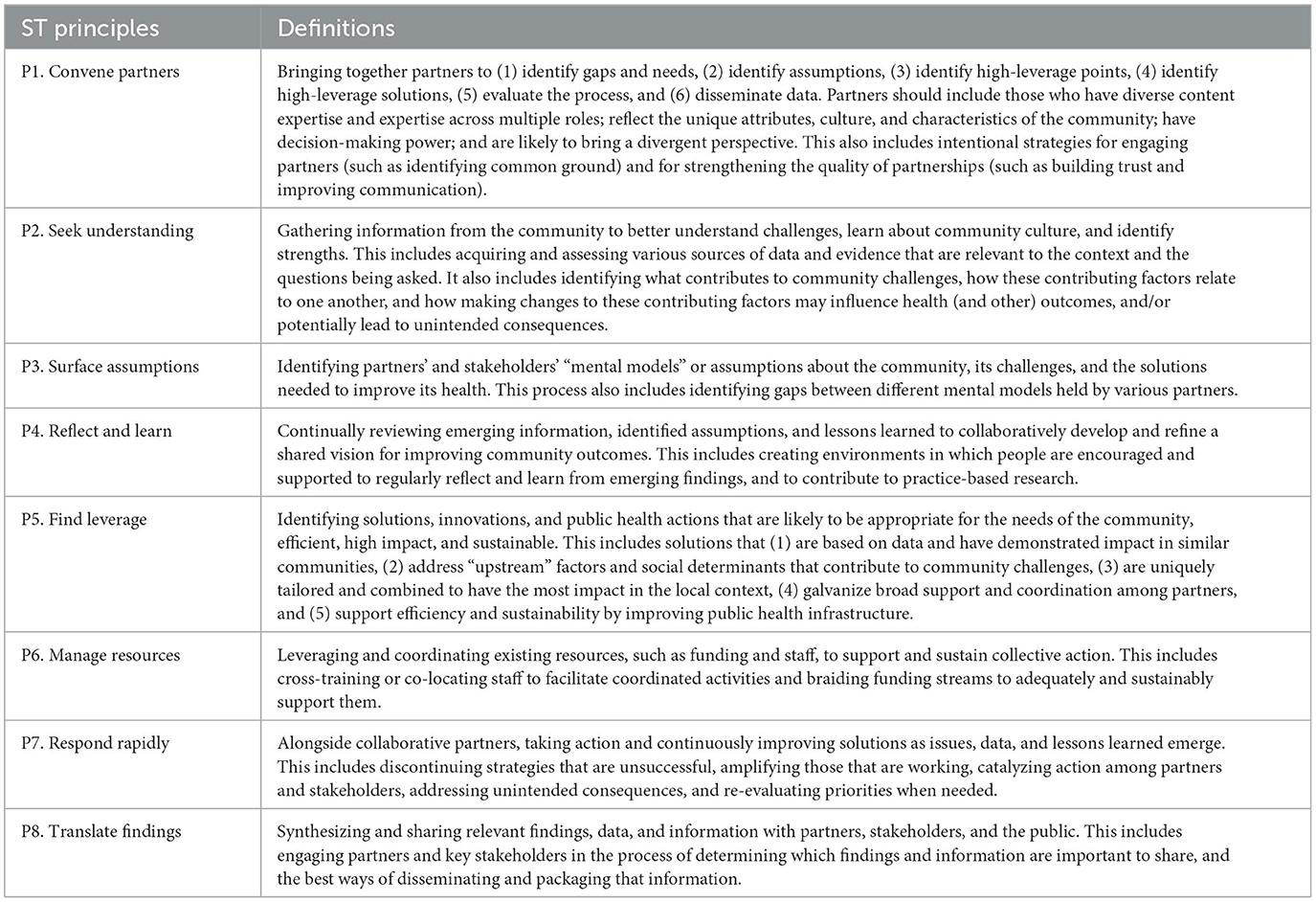

Operationalization of ST on the organizational level is also scarce. Indicators that can provide insights into how and to what extent organizations apply ST are limited or even seen as lacking, especially within the public health domain (22, 47). Smith et al. (47) have recently proposed a framework for ST in public health, which combines ST, collaborative inquiry and action, and systemic science and methods. The framework is based on previous public health frameworks (48), and the framework's initial concepts (49) were further refined drawing on insights from public health scientists and practitioners with experiences from nine policy programs (22). It has been further operationalized and tested by Wilkins et al. (22), and eight principles of a systems orientation have been proposed (Table 1). Wilkins et al. (22) also developed and tested quantitative indicators of the ST principles within organizations (i.e., state public health departments) focusing on the area of state injury and violence prevention. Their attempt is focused on evaluation and is considered a first step “toward measuring ST at the organizational level in public health” [23, p.76]. Their study provides quantitative indications of an ST aspect in terms of numbers, presence or absence, or percentage, e.g., Convene partners—the number of internal (health departments) and external partners engaged to advance injury and violence prevention activities/strategies/programs/policies per year. It is proposed that such indicators can be used to identify ST in an organization. However, it does not provide a detailed description of how ST is used in practice or describe strategies that can aid those who work with soft-law initiatives addressing ill-structured or wicked problems.

Table 1. Definitions of the eight principles of ST on the organizational level (22).

This study focuses on how ST was used in practice within a national soft-law initiative that addressed several wicked problems and was launched in a decentralized healthcare system. To find indications of if and how ST is used in practice within such policy program, observations of individual skills and social and cognitive processes in groups would benefit from being complemented with other indications (22), and Wilkins et al.'s ST principles have a potential to enrich our understanding of how ST reveals itself in practical activities and the action strategies used within a policy program.

This study aimed to investigate how ST is expressed in practice in complex policy programs addressing wicked problems and describe the specific action strategies used in practice in a national program in Sweden, using a new conceptual framework comprising ST principles on the organizational level (22) as an analytical tool. Providing narrative descriptions of how ST is used in practice, complementary to Wilkins et al.'s (22) test of indicators, can aid others involved in similar soft-law initiatives and policy programs. The underlying assumption behind the study is, in line with previous research, that ST can facilitate change and development within public health [e.g., (10, 13, 14, 16, 49)], by promoting a more holistic understanding of complex social phenomena in complex settings and by supporting collaborative approaches to address ill-structured problems.

This explorative case study uses a rich set of longitudinal data collected during the multi-year implementation of a national policy program in Sweden. The program was chosen partly due to convenience (i.e., access to data) but mainly due to its complexity, representing a comprehensive policy program aimed at several large improvement areas representing wicked problems within a large, complex national setting comprising many geographical areas (i.e., 21 self-governed regions), types of care providers (primary and specialized hospital care, and public and private providers), types of care (e.g., delivery care and neonatal care), units (e.g., primary healthcare units and delivery care clinics), and actors. The study was reviewed by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, and they found a formal ethical approval was not needed (ref no. 2018/620-31).

The Swedish healthcare system is comparatively decentralized and divided into 21 regional self-governing authorities and 290 municipalities. The regions, which vary in size and demography, are responsible for the provision of healthcare services, and the municipalities for providing home healthcare and social care. The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR) is a member organization representing the self-governing regions and municipalities and, as such, is an influential policy actor. Healthcare is mainly tax-funded, and most care providers are publicly owned. Maternal healthcare is provided at outpatient maternal healthcare clinics led by midwives (50). These clinics work with health in connection to pregnancy, support to families, contraceptive counseling, and public health. During pregnancy, women have access to free controls starting from weeks 8 to 12. Unless there is a health problem, women do not see a doctor during the pregnancy. After pregnancy, routine post-partum care is offered (50).

Improving Women's Health and Care before, during, and after Pregnancy program (WHCP program) aims to affect an extensive system, i.e., maternity care, antenatal care, delivery care, post-partum care, and, from 2018, neonatal care, in all 21 regions. The organizations of these subsystems have regional variations. Maternity can be part of the same subsystem as delivery care and gynecology or be organized under primary healthcare. The variation also concerns the number of private care providers, mainly offering maternity care before childbirth. Private care providers were essentially absent in some regions and more common in the large urban regions.

The program was initiated in late 2015 to be implemented between 2016 and 2019. It is based on agreements between the national and regional political levels, i.e., between the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs and SALAR, the latter a national organization representing the 21 self-governed regions that attend to, support, and coordinate the regions' common interests. Instead of addressing the complex challenges and (wicked) problems via laws or regulations, they were addressed by an agreement that the regions would put efforts into improving certain areas, based on and adapted to the local situation, and receive funding for this from the government. The agreements were based on mutual trust rather than on control or enforcement. The first agreement was followed by several additional agreements, increasing the scope of the program, and extending the implementation period until the end of 2023. Thus, the implementation of the policy program stretches over almost 9 years. The program aims to improve women's sexual and reproductive health and maternity, antenatal, and post-partum care. The agreement is more decentralized than some previous ones [e.g., (51–53)] where the funding was linked to performance measures.

In 2015, a national program team was formed at SALAR, responsible for leading, coordinating, supporting, and following up on the program's progress and its outcomes. This team had little mandate to enforce the program and did not influence the allocation of the program's finances, which were sent directly to the regions. In 2018, the national program team developed a strategic plan based on the agreement, see Figure 1—adapted from (54), which formed the basis for the forthcoming program. The strategic plan visualized and described the program vision, goals, prerequisites, and overarching strategies.

The program is decentralized, implying that the 21 regions are responsible for identifying needs, prioritizing, and implementing interventions to improve their work within the strategic areas of the program. Regional contact persons, appointed by the director of health in each region, function as the nodes for contact and interaction with the WHCP program team at SALAR. The funding was distributed directly to the regions based on the size of their population, with a smaller amount designated to the program team, and the funding for some special missions was given to public authorities, e.g., the National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW). Thus, the regions could decide how to distribute the funding to reach the goals of the program, based on their knowledge of the regional and local conditions. The Swedish Agency for Health and Care Services Analysis was given the mission to evaluate the program's outcomes.

Since 2017, data about the program have been collected and compiled in a comprehensive case study database by external researchers (among them authors MEN, ST, and VS), as a part of a longitudinal (still ongoing) research project. The database consists of semi-structured individual and group interviews conducted with program team members (2018–2021), contact persons from all regions (2018 and 2020–2021), and external program evaluators (2020); non-participant observations of meetings (2017–2022); and documents (e.g., reports, evaluations, policy documents, meeting agendas, and presentation material), survey data, quality registry data, and national and regional publicly available statistics.

In this study, we have used a representative sample of interviews, observations, and archival data sources chosen to represent various types of data, content, actors, and time periods from the database which cover a 5-year period (March 2017 to March 2022), excluding outcome data, i.e., quality registries (Table 2). The sample consisted of 12 interviews with the program team (2018; 2020), 4 representative interviews with regional contact persons, 20 observations of meetings and conferences (2017–2022), and 34 documents (2016–2022). Interviews with the program team and with contact persons covered similar themes: national or regional program organization; strategies and activities; conditions and enabling and hindering factors; communication; support; follow-up and evaluation; effects; learnings; and plans for the next year. In two rounds of interviews, the program team members described their experiences of situations, important activities, perceived effects, and, if they can, the intentions and rationales behind them. Interviews contain both current and retrospective data. Interview guides can be found in Supplementary material 1–4. Interviews with regional contact persons were added to represent their experiences of the program activities and action strategies. Twenty non-participant observations of activities performed within the program and their detailed content (i.e., what was presented and discussed) were collected. The observation template and an example of observation data can be found in Supplementary material 5. Descriptions of activities and their content could be found in documentation, i.e., archival data (see Supplementary material 5 for examples of different types).

The definitions of the eight ST principles (see Table 1) in the refined conceptual framework (22) were used to identify and categorize indications of the practical use of ST within the program.

First, the researchers familiarized themselves with the eight ST principles by discussing examples of what type of program content and data potentially could contain indications of the principles (Table 1). Then, relevant data sources, representative of the program process over time, were identified and selected from the large database (Table 2).

An iterative approach based on deductive content analysis (55) was applied using the definitions of the principles in the framework (22), presented in Table 1. Multiple data sources (e.g., interviews and archival data) were used to triangulate information about activities and expressed strategies fitting the definition of each principle. The first step of the analysis was performed by two researchers (ST and MN) by coding data information in the data sample using the principles in the framework. After sharing these extracts, all four researchers met in six 1–3 h-long meeting sessions to scrutinize and further discuss the interpretation of the identified text in relation to each principle and to reach a consensus on program findings that could represent the principles, if found. The procedure intended to ensure reliability and validity in the interpretations of the qualitative data and resulted in a few alterations of the narrative descriptions used (i.e., one activity description was not used, and one was placed under another ST principle). Interview quotations and extracts of text used for the illustration of the principles were chosen during this process. Finally, a synthesis of data on each principle, including identified action strategies, formed the basis for a narrative description of how ST was used in the program.

In this section, narrative descriptions are presented about how the organizational level ST principles (P1–8), put forward by Wilkins et al. (22), were applied in practice in the WHCP program. For each principle, examples from different data sources can be found in Supplementary material 5, while Tables 3–10 provide the action strategies and detailed examples for each principle.

The principle Convene Partners concerns identifying, reaching, involving, and engaging the right actors at the right time and comprises both the variety of involved stakeholders and partners and what they do together, which includes the forthcoming principles. How to identify, reach, and involve the right actors at the right time depends on the complexity of the program and its setting.

To address the issues and reach the WHCP program goals of a more equal, accessible, safe, knowledge-based, and person-centered care for women over the entire country meant identifying and involving many different actors and professions from different parts and levels of the healthcare system, from politicians to patient representatives. This was recognized by the program team members and described in interviews as being important from the start of the program. It was also visible in the amount and type of actors involved in the various program activities over time (see Figure 2). Different actors were involved in the identification and analyses of challenges, problems, and contextual influences and in problem-solving, planning, and follow-up activities, either regularly or for limited periods of time. This ensured that many perspectives could be considered when planning and implementing program activities. The regular interaction with other national authorities and programs was perceived by the program team members to reduce the risk of launching competing activities. The interaction with and consideration of the different actors and their interests require significant amounts of time and skills on behalf of the program team. Reaching and involving higher regional decision-makers was difficult. They were informed when the program was initiated and later in their monthly national meetings. Depending on the chosen regional contact person and regional strategy meant that key actors on a higher regional level could have been more or less involved in the realization of the program intentions. The team coordinating the program at the national level was based at SALAR, which is a members' and an employers' organization for all the regions in Sweden. This created unique opportunities for the team to get a national overview and facilitate linkages between national and regional levels. This platform secured a mandate to facilitate collaborations and coordinate ongoing system changes. Due to the decentralized approach regarding regional power over the choices of problem areas and interventions, the regional contact persons were key actors in stimulating regional change. The five main action strategies identified are described in Table 3. Figure 2 provides an overview of the types of actors involved in the program and the action strategies used.

The principle Seek Understanding concerns gathering information from the context to better understand what contributes to challenges and strengths, how these contributions relate to each other, and how making changes to these contributions may influence outcomes and potentially lead to unintended consequences.

The WHCP program comprised several multi-faceted issues, e.g., equity in care, attracting and keeping competent staff, patient safety, availability of care, person-centered care, and integrated care. How to understand this range of issues, what contributes to the challenges and also consider regional variations and context-specific conditions for providing healthcare, was addressed in meetings and some team members expressed in interviews as a challenge.

The analyses of problems and needs were an important strategy on behalf of the program team. Mappings and gap analyses were conducted and presented in reports and then communicated, discussed, and reflected on during several meetings with regional actors. Monitoring different media also became important for understanding the region's various conditions and challenges. The program team's efforts to gather information to better understand regional and contextual challenges, often together with program stakeholders and partners, were perceived to contribute to a better understanding of both the system features and the complex improvement areas the program aimed to affect, especially for new members in the program team and contact persons, and also for others involved, for example, from national authorities. The strategic plan developed in 2018 (Figure 1) was an important tool for aiding the understanding of the program, especially as each region could, based on their context-specific needs, choose which areas of the program to focus on and which interventions to use. The seven main action strategies identified are described in Table 4.

The principle Surface Assumption concerns identifying partners' and stakeholders' assumptions about the focus areas and the program and the challenges and solutions needed to improve care and women's health. The overarching goals and structure of the program were set in negotiation between actors representing the government, politicians, and decision-makers from the regions and representatives from SALAR. Thus, the agreement was originally based on the mental models and assumptions of those involved in negotiating, writing, and signing the agreement, mirroring mainly a political perspective on issues and on what constitutes good care for women before, during, and after pregnancy. The negotiations resulted in a high degree of freedom regarding the implementation of the agreement, and the goals were rather general to suit stakeholders with divergent needs (see Figure 1). Due to the program's comprehensive character and being a national initiative aiming to influence processes in the autonomous regions, the program team would need to identify the underlying assumptions held by actors on multiple system levels, which could reduce confusions and conflicts, and facilitate the program team's choices of implementation support.

The program team worked to surface assumptions held by stakeholders directly involved in the implementation, and those held by the contracting parties in the policy agreement, i.e., the government and SALAR. This is partly expressed in Principle 2 in the ways the team tried to seek understanding by involving different actors, but it was not explicitly described in the team members' interviews as a strategy. For program team members and contact persons, the knowledge gained on different perspectives and assumptions would increase their awareness of the existing and contradicting views when planning or adapting program activities. However, most of the analysis of actors' assumptions, mental models, and potential conflicts of interest did not occur during the actual meetings with the invited stakeholders, but rather in discussions after these meetings. Deeper analyses of stakeholders' mental models and the potential effect of contradicting assumptions did not occur as often as the discussions aimed to reveal or clarify them. We found no indication that this principle was used with the higher-level regional decision-makers, whose assumptions can affect the program implementation. The three main action strategies identified are described in Table 5.

The principle Reflect and Learn concerns continually reviewing new information, assumptions, and learnings to jointly be able to develop and refine a shared vision for, in this case, the improvement of women's sexual and reproductive healthcare. An important part of this principle is to create environments where people are encouraged to reflect and learn.

Initially, the program team focused mostly on spreading information about the program and less on creating opportunities for mutual interaction. However, the focus shifted and efforts to create opportunities and arenas for reflection and learning increased over time. We found many indications of the use of this principle in the program activities and in the described action strategies (see Table 6). The arenas and opportunities to review new information, reveal assumptions, and reflect and highlight lessons learned increased over the program period. From having contact persons meeting twice a year to meetings every month plus two 2-day conferences each year. This development within the program team resulted in the discussion of if and how suggestions, activities, and solutions stemming from different actors, and their perspectives should be incorporated into the new yearly agreements or in the implementation of the program. The arenas and opportunities used for reflection and learning were perceived by program team members to have increased the capacity for change among actors in the regions. Mutual reflection and learning were adapted to the medium used for the meetings (face-to-face or digital meetings) and the time restrictions (length and regularity of meetings). The known effects of the team's attempts to enhance learning to aid program implementation in the regions are limited. The five main action strategies identified are described in Table 6.

The principle Finding Leverage concerns identifying solutions, innovations, and actions that are efficient, have a high impact, are sustainable, and meet the needs of the community, in this case, those delivering care to women in all regions before, during, and after childbirth. The solutions should be based on data, address “upstream” factors, be tailored to the local context, provide support, aid coordination among involved partners, and improve infrastructure (in the area focused on).

Finding high-leverage solutions to the many issues in the WHCP program that could have a high effect nationwide, and in the complex settings of 21 different regional systems, was important but challenging for the program team. Efforts were made to identify and analyze problem areas, spread existing knowledge, and successfully test innovations in each of the program's main goals and strategies (Table 7). Analyses of issues and identification of gaps and knowledge were done both to seek understanding (P2) and to find successful solutions (P5). The generated reports formed a basis for other activities, e.g., webinars and workshops. Developing the regional capacity to facilitate innovation and improvement and to spread and sustain high-impact solutions was identified as important to enable regional actors to implement the changes needed in the program's focus areas. However, although the interrelations among the focus areas and how the issues could be tackled in integrated ways were sometimes discussed within the program team and briefly together with other actors, potential solutions or examples of them were not made as explicit or clearly presented in meetings as the solutions found on single issues or within single focus areas. The five main action strategies identified are described in Table 7.

The principle Manage Resources concerns levering and coordinating resources in terms of funding, people, technology, and equipment. To manage resources means to allocate them in a strategic way, so they support any chosen intervention's impact and follow-up on the results. This can, for example, involve temporal aspects, choices of high-leverage solutions, or prioritizing between target areas.

In the WHCP program, the needed changes outlined in the national policy agreement were to take place in, and ultimately be managed by, the self-governing regions. This limited the mandate of the program team to manage resources in relation to the change process, compared to what might be the case in organizations. Since the program was based on a series of separate, but related, policy agreements between the government and SALAR as a representative for all the regions, funding varied over time as new agreements were settled. The program team at SALAR received funding for coordinating national activities to support the regions' improvement efforts, but the main part of the resources was directly transferred to the regions, based on their population size. The regions then allocated these program resources according to local needs and regional priorities. Thus, in practice, the national level had little control over how the resources were allocated and had to find ways to get information from the regions. Initially, the program's reporting requirements were neither very strict nor detailed, but successively requirements changed and increased, and the regional activity reports gained more importance over time.

The national level had two primary means to influence the allocation of resources within the regions. The first was the selection of indicators from National Quality Registries and the National Pregnancy Survey used for follow-ups and presented to the regions. The other was the design of the questionnaire-like template for the regions' yearly activity report, highlighting the importance of thinking about the whole change process, including how the resources were used. Therefore, the program team also offered support sessions to the contact persons when it was time to compile the activity reports. For the 2021 agreement, there was a specific request for detailed information on how the funding had been used in the areas highlighted in this agreement. The four main action strategies identified are described in Table 8.

The principle Respond Rapidly concerns taking actions and continuously improving solutions or discontinuing unsuccessful strategies, catalyzing action among stakeholders and partners, and re-evaluating when needed. A long-term, nationwide program in a decentralized setting that involves many regions, organizations, and people puts special demands on the interaction between the national and the regional and local levels.

The close interaction that the program team developed with the regional representatives led to expectations on the team to respond swiftly to highlighted problems and needs, expressed in interviews and during meetings. The strategies, both for how to find signals and how to respond to them, constantly evolved as information was accumulated and needs discovered, based on discussions with involved actors, mappings, and data from the National Pregnancy Survey and the quality registries. The three main action strategies identified are described in Table 9.

The principle Translate Findings means synthesizing and sharing relevant findings, data, and information with partners, stakeholders, and the public. In this process, key partners and stakeholders will be engaged to determine the importance of information and how to spread it. This process can be more or less of a challenge, depending on the complexity of the problems addressed, interventions used, data collected, and settings where information and findings shall be disseminated. In a large improvement initiative such as the WHCP program, this was a rather complex task.

The intention to translate relevant findings, i.e., prioritizing what information was important to share, with whom, how, and why, together with key actors, permeated the entire program. The ability to translate and use findings in the program increased over time, as more data became available via National Quality Registries, the National Pregnancy Survey, and the yearly regional activity reports. Team members described the use of findings and data to support both improvements and learning. Sharing of data and findings created both an interest in and a better understanding of the program and its focus, challenges, and effects on both partners and stakeholders and in media.

Aiming to increase the knowledge of how ST is used in practice in national policy programs addressing wicked problems, we searched for indications of ST in data describing the main program activities and action strategies in a national program addressing complex issues in women's healthcare in Sweden. We used a conceptual framework comprising principles of organizational level ST (22) as an analytical tool, and we have provided narrative examples and descriptions of action strategies used in the program for each principle. This differs from the study of Wilkins et al. (22), which focused on organizations working with the implementation of policies, and their work on identifying and testing quantitative indicators of the operationalization of the ST principles in these organizations and within the area of injury and violence prevention. In this study, we have tested a way to retrospectively identify whether and how ST principles were used (intentionally or unintentionally) within a national soft-law policy program where ST had not been discussed or intentionally introduced as a strategy.

The proposed ST principles (22) may seem logical to follow for any project manager. However, the complexity and dynamics of the policy program (its content and organization), the decentralized healthcare system setting, and the multi-dimensionality of the problems addressed pose additional challenges to actors involved in the implementation of the studied program. Thus, the application of ST on a system level is more complicated than in most (single) organizational settings. Initial understanding and analyses of the system, the issues addressed, and the program features are a foundation for being able to identify stakeholders and important actors to initially involve before considering the other ST principles.

Improving healthcare, or the health of the population, means dealing with complex issues or wicked problems (2, 3). It is difficult to create a holistic view of a complex program aiming to improve several ill-structured issues and induce changes in a large healthcare system. Similarly, it is difficult to design activities for supporting such changes, since it requires considering multiple perspectives, stakeholders, subsystems, and transformation and adaption processes. The ST principles provide some main categories that can aid the classification and description of the action strategies used in the WHCP program. Some main learnings may aid future attempts to understand and facilitate the use of ST in practice when implementing complex policy programs addressing ill-structured and wicked problems in large and decentralized healthcare systems.

To convene actors with a different perspective (ST Principle 1) involve them as partners or use collaborative approaches are not exclusively connected to ST or a policy program. Collaborative approaches are the most often promoted ways to tackle complex issues and ensure that important perspectives of those affected by changes and those that can affect them are incorporated into interventions (56). Individuals and teams involved in the core of developing and implementing national policy programs will have to make decisions, solve problems, and use sense-making to create momentum in change processes, but due to the inherent complexity when addressing ill-structured and wicked problems in a complex system, achieving change is a collaborative challenge involving more actors than in organizational change attempts. To comply with national soft-law policies is not mandatory, but research has shown that the Swedish regions find it hard not to participate in national policy agreements (9). Reasons for this can be compliance mechanisms, such as peer pressure and a sense of moral responsibility, and also SALAR's role as an intermediate actor, i.e., being both the region's representative on the national level and a contracting party in the agreement (9). In this case, there was a shared awareness of the problems in women's healthcare and a readiness for improvements among the regions. The regions also had a high degree of freedom to choose which interventions to focus on within the policy program, based on their own needs, and there were no strict performance requirements or target levels as in some of the previous national agreements [e.g., (51)].

The mix of actors involved aided the processes of understanding and identifying leverage that integrated the perspectives of multiple levels. Engaging actors with decision-making power in the ST processes was also a way for the program team to indirectly try to influence the allocation of resources to enable the intended changes. Still, it was difficult to reach higher-level decision-makers, and the use of separate regional dialogue meetings with a group of regional representatives for each of the 21 regions was one activity that was described as having some impact. For stakeholders, especially higher-level decision-makers, to engage, there needs to be a will and an understanding of the needs and benefits of getting involved in an interactive process of building a shared mental model of the system and the issues to be solved. In a complex program context, it might also be beneficial to further define expectations on a program partner or stakeholder, as their interest and agendas can vary (57). Carefully analyzing and clarifying what types of actors are important to involve and how to involve them can aid the work of a program team. However, the team may need to prioritize and channel their interaction efforts to make the largest impact on the program, especially if resources are scarce.

The composition of individuals in a team leading a program is of special importance. If ST is a guiding approach in large and complex programs, this requires some attention in the initial forming of a team. A clear strategy in the studied program was to include members with different competencies and perspectives, some with connections to other related national agreements, and some with their basic employment in the regions. It is unlikely even for skilled program managers to possess all the capabilities needed to manage a national program focusing on large system transformation. This strategy was also seen as an effective way to extend the team's network, improve communication with stakeholders and partners, and promote an understanding of the program as part of a larger system transformation, i.e., to enhance ST in the team. Previous research on program management has focused on individual program managers and their competencies and actions, but less is known about the nature of the distributed capabilities among other actors in the core and extended program team and how they may contribute to a more holistic view of the program and its change process (58).

The need to address complex and interrelated issues and wicked problems in healthcare in Sweden or elsewhere is not new, but there has been an increase in more complex national initiatives over time. The WHCP program is one example where the goals concern development in a diversity of areas, comprising great challenges. Challenges faced by decision-makers, care providers, and patients may be similar in a general sense, but the dynamic regional and local conditions must be considered when aiming for more sustainable changes (59). Thus, the program team had to consider assumptions and mental models held by actors on multiple levels and develop strategies to connect these views. This was difficult, but the strategic plan, represented also in graphical format, played an important part in this process in several ways. First, by involving stakeholders in the development of the plan, i.e., operationalizing the political intentions expressed in the agreement, which helped to develop a shared vision of the program and its goals, and second, by functioning as a visual communication tool for the team (both internally and externally). Using visualization to represent concepts, components, and their interrelationships is a powerful methodology within ST that can aid sense-making and the creation of shared mental models (45). Even so, to reveal underlying assumptions in general, and especially of important strategic-level stakeholders and decision-makers on higher regional levels, was less described as a strategy by the program team. Also, higher-level regional managers were hard to reach to inform about and discuss the program, and revealing assumptions would require more interaction. Instead, the program team focused on other regional actors easier to access, such as the contact persons.

In a large, complex, and long-term policy program, there are many dimensions and conditions that must be considered to enable reflection, learning, and collaboration among the involved actors. The challenge is to create opportunities and communication arenas that can support collaboration, reflection, and learning, and find and develop ways to deal with ill-structured and complex issues. Achieving deeper learning and changing people's behavior and action strategies takes time. This requirement may not fit very well with the restricted time and/or resources of a program, or with the expectations and views of involved stakeholders and partners.

An important aspect of the program was to provide opportunities and arenas for reflection, feedback, and learning, on group and individual levels. The frequent use of group discussions in meetings is one example. In meetings, there was often a mix of participants from different levels of the healthcare system, which enabled learning and exchange of experiences across national, regional, and local levels. Sometimes, single participants have multiple perspectives, e.g., a regional contact person could also be involved in national groupings, such as producing guidelines. Altogether, the large number of activities designed for enabling interaction, reflection, and learning, such as network meetings, the teams' regular half-day meetings, and numerous workshops and courses, can be interpreted as representing a learning culture within the program, especially on behalf of the program team and the contact persons' network. Active reflection and learning opportunities are at the core of a change process, especially when aiming to achieve double-loop learning for more substantial behavioral changes in both individuals and organizations (60, 61).

Synthesizing and sharing relevant findings and using them to enhance learning and change was a core task for the program team. Interactions and relations with partners and stakeholders were central to the program's communication strategy, which emphasized responsiveness and an adaptive approach regarding how to reach different target groups and audiences. Strategic communication within the program involved a meta-process of integrating information, understandings, and learnings on the program level, making sense of the results in a larger perspective, and choosing the best way to package the information and feed it back to key actors. Management of such processes requires ST skills (30, 33).

One aspect of the learning approach applied in the program was to engage a variety of actors in developing interventions that could affect and improve issues identified in each program focus area. ST has been suggested to aid the process of identifying high-leverage solutions that can address multiple health outcomes (11). The program focused on many interconnected challenges. Finding leverage and multi-level solutions that can affect the whole system and its sub-parts is seen as important (14), but in the decentralized Swedish healthcare context with 21 autonomous regions, it presents a real challenge. The program team used a strategy with iterative reflection and learning loops to build joint understandings and consensus on problems and collaborative approaches to search for interventions to improve issues that could be adapted to various regional and local contexts.

Understanding ST in use in a policy program involves an understanding of the overlapping nature of the hierarchical system levels in the program context, i.e., national, regional, and local system levels (Figure 2), and the interactions among the organizational, group, and individual-level ST potentially at play in the program strategies.

In the WHCP program, it was important to achieve a holistic view and a common understanding of the program issues among actors in different parts of the system, e.g., politicians, authorities, and professional organizations on the national level, and politicians, public management, and care providers in the autonomous regions. Even so, in-depth discussions to identify gaps between mental models together with partners were less frequent and gaps would typically become evident after some time and discussed in other group constellations. Reasons for this might be the complex political landscape and the dual role of SALAR as both the coordinator of change initiatives stemming from the government and the organization representing the rather independent regions and municipalities (9, 53).

Much of the previous research on how ST can be used in practice has focused either on the individual, group, or organizational level. Combined approaches are scarcer but exist [e.g., (43)]. Figure 3 shows the system levels involved in a large healthcare policy program and examples of aspects influencing ST on each level. The community/society level can be added, but it remains to be seen if ST can be investigated on this level. However, the wider national context and its structure and culture will have an impact on policy programs, and the external context of the healthcare system addressed in such a program must be understood. Among other things, ST highlights “the importance of coordinated and effective interventions across multiple levels of change (e.g., individual, organizational, community) (…) and the critical role of strategic communications to catalyze, coordinate and support change” [25, p. 154–55]. Our studied case provides some practical examples of these aspects, in terms of the action strategies used by a policy program team.

Figure 3. Systems thinking (ST) on several levels of analysis in relation to a national policy program.

One reason for the limited empirical studies of the use of ST in practice, especially within public health (15–17), might be the complexity of a combined approach and the difficulties of comprehensively presenting such studies. Looking at the implementation of a national policy program from an overarching system perspective, it is evident that ST may be used at the individual, group, and organizational levels simultaneously (Figure 3), and that an integrated approach is needed to understand how ST is expressed in practice, how its use can be supported, and assessing the possible impacts of using ST to facilitate change on different levels (individual, group, and organizational levels). For example, it seems important to actively choose a person who possesses ST skills as a program manager, to foster collaborative ST in program teams and regional teams, and to develop action strategies in line with organizational-level ST.

A general observation when applying the ST principles to our qualitative data is that the principles are somewhat overlapping. A holistic view is more evident in some of the principles, and it emerges as the principles are added to one another. Another observation was that as we analyzed the data, we found that multiple principles were enacted simultaneously in each of the main program activities. This study describes the nuances of how ST is used in practice within a policy program context.

It is difficult to judge the effects of the use of the ST principles on the outcomes of the ongoing program as this would require a more extensive understanding of both the issues addressed and the mechanisms underlying the ST principles and the action strategies related to them. In addition, the way ST is used, or not, in the 21 regions needs to be addressed. Also, wicked problems cannot be seen as having linear cause–symptom–effect relationships, they evolve unpredictably over time and involve value conflicts among actors (62). This makes it difficult to assess the impact of ST principles on the WHCP program outcomes; possibly, the impact on involved stakeholders and partners, and their action strategies, could have been assessed, based on additional interviews.

The study is limited to one case, a policy program. The WCHP program was chosen for several reasons: It represents a complex system (14) as it addresses complex issues and challenges in a decentralized healthcare system; it is a longitudinal program where the opportunities to develop ST have been good, and indications on a comprehensive approach have been described in previous reports (in Swedish). In addition, an extensive case study database exists, where indications of applications of ST can be found. However, we did not analyze all the data in the database in this study, as it was not feasible due to its scope and the time available. All interviews conducted with the program team over time were analyzed, but regarding the other types of data sources (e.g., observations and archival data), a representative sample was selected and analyzed. An analysis of the total dataset may have yielded a slightly different or more complete and richer picture of ST in practice within the program. However, the researcher's familiarity with the data and the knowledge gained by studying the program for 6 years guided the selection of data. Theoretical generalization (63) can broaden the use of the study but still, the specific conditions of this example from the Swedish healthcare system must be considered.

There are some main learnings and implications from using the organizational-level ST framework to identify and describe how ST is applied in practice in the context of a national policy program addressing several wicked problems in a decentralized national healthcare system. Some practical implications may also aid future attempts both to understand and to facilitate the use of ST in policy programs.

First, engaging the right partners in the change process, who represent a broad range of different perspectives and have a mandate to act, is key for enabling ST on the organizational level, but even more so in a national program aiming for impact in 21 self-governing regional systems. Thus, this first ST principle forms the basis for applying the other seven principles described in Wilkins et al.'s framework.

Second, the high degree of complexity of the program content and the variety and dynamics of the settings that a national policy program often encounters create conditions that need special attention from the actors involved. A high degree of program dynamic and complexity executed in a complex program setting require a deeper understanding of underlying principles guiding ST, and more time and effort to plan and execute ST-informed action strategies. The strategies must be used, and adjusted, repeatedly during an extended time period. Such programs will need more resources, time, and competence during their implementation than programs with less complexity.

Third, even very basic use of ST tools (e.g., developing a graphical representation of a strategic plan) can function as important levers for ST in practice in a large policy program aiming for system change. Visualization is a practical tool of special importance if the program and setting complexity are high.

Furthermore, the narrative descriptions of the action strategies related to ST principles provided in this study, as well as the described difficulties encountered by the program team when using them, provide details that can aid others who lead and support the implementation of soft-law initiatives and policy programs.

Detailed, systematic descriptions of action strategies used to support changes in large systems initiatives are still scarce. A multi-level approach is needed to fully grasp how ST is expressed in practice, as individual, group, and organizational-level ST are all inherent in a policy program. To increase the understanding of how to identify and learn more about the practical use of ST in policy programs and public health, we suggest further studies of how ST is used in practice in other policy programs, both in similar and different national contexts. The framework of the organizational ST principles used in this study, together with our observations of the interrelationships between different levels and dimensions of ST in practice, can contribute to such studies.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The study was reviewed by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, and they found not to need for a formal ethical approval and issued a statement of this (Ref. No. 2018/620-31).

MN and HS designed the study and drafted the manuscript. MN, ST, and VS collected the data. MN, ST, VS, and HS conducted the analyses. All authors read, contributed to the article, and approved the final manuscript.

This study was financially supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE), i.e., the Large System Transformation Strategies project (Grant No. 2018-00220), with additional funding from the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs in Sweden, via the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Region (with no restrictions impeding the research content).

The authors would like to thank the program participants for their time and effort when sharing their experiences and documentation.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.957653/full#supplementary-material

ST, Systems thinking; SSM, Soft Systems Methodology; WHCP program, The improving Women's Health and Care before, during, and after Pregnancy program; NBHW, The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare; SALAR, The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions.

1. Conklin J. Wicked problems and social complexity. In: Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (2005).

2. Riley BL, Willis CD, Holmes BJ, Finegood DT, Best A. Systems thinking in dissemination and implementation research. In: Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2012).

3. Raisio H, Puustinen A, Vartiainen P. The concept of wicked problems: improving the understanding of managing problem wickedness in health and social care. In: The Management of Wicked Problems in Health and Social Care. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group (2018).

4. Strehlenert H. From Policy to Practice: Exploring the Implementation of a National Policy for Improving Health and Social Care. Stockholm: Karolinska Institutet (2017).

5. Green LW. Closing the chasm between research and practice: evidence of and for change. Health Promot J Aust. (2014) 25:25–9. doi: 10.1071/HE13101

6. Rittel HWJ, Webber MM. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. (1973) 4:155–69. doi: 10.1007/BF01405730

8. Daviter F. Coping, taming or solving: alternative approaches to the governance of wicked problems. Pol Stud. (2017) 38:571–88. doi: 10.1080/01442872.2017.1384543

9. Fredriksson M, Blomqvist P, Winblad U. Conflict and compliance in Swedish health care governance: soft law in the “shadow of hierarchy.” Scand Pol Stud. (2012) 35:48–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2011.00279.x

10. Peters DH. The application of systems thinking in health: why use systems thinking? Health Res Pol Syst. (2014) 2:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-51

11. Diez Roux AV. Complex systems thinking and current impasses in health disparities research. Am J Public Health. (2011) 101:1627–34. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300149

12. Luke DA, Stamatakis KA. Systems science methods in public health: dynamics, networks, and agents. Annu Rev Public Health. (2012) 33:357–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101222

13. Leischow SJ, Best A, Trochim WM, Clark PI, Gallagher RS, Marcus SE, et al. Systems thinking to improve the public's health. Am J Prev Med. (2008) 35:S196-203. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.014

14. Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, Bibby J, Cummins S, Finegood DT, et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet. (2017) 390:2602–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31267-9

15. Chughtai S, Blanchet K. Systems thinking in public health: a bibliographic contribution to a meta-narrative review. Health Pol Plan. (2017) 32:585–94. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw159

16. Carey G, Malbon E, Carey N, Joyce A, Crammond B, Carey A. Systems science and systems thinking for public health: a systematic review of the field. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e009002. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009002

17. Rusoja E, Haynie D, Sievers J, Mustafee N, Nelson F, Reynolds M, et al. Thinking about complexity in health: a systematic review of the key systems thinking and complexity ideas in health. J Eval Clin Pract. (2018) 24:600–6. doi: 10.1111/jep.12856

18. Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Studying complexity in health services research: Desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med. (2018) 16:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1089-4

19. Swanson RC, Cattaneo A, Bradley E, Chunharas S, Atun R, Abbas KM, et al. Rethinking health systems strengthening: key systems thinking tools and strategies for transformational change. Health Pol Plan. (2012) 27:iv54–61. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs090

20. Russell E, Swanson RC, Atun R, Nishtar S, Chunharas S. Systems thinking for the post-2015 agenda. Lancet. (2014) 383:2124–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61028-X

21. Cabrera D, Colosi L, Lobdell C. Systems thinking. Eval Prog Plan. (2008) 31:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.12.001

22. Wilkins NJ, Kossover-Smith RA, Hogan SA, Espinosa R, Wilson LF. Developing indicators to evaluate systems thinking and application in state injury and violence prevention programs. N Direct Evaluat. (2021) 170:67–80. doi: 10.1002/ev.20456

23. Dolansky MA, Moore SM, Palmieri PA, Singh MK. Development and validation of the systems thinking scale. J Gen Int Med. (2020) 35:2314–20. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05830-1

24. Best A, Holmes B. Systems thinking, knowledge and action: towards better models and methods. Evid Pol. (2010) 6:145–59. doi: 10.1332/174426410X502284

25. Best A, Clark PI, Leischow SJ, Trochim WMK. Greater Than the Sum: Systems Thinking in Tobacco Control. Tobacco Control Monograph No. 18. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (2007). doi: 10.1037/e566202009-001

26. Shaked H, Schechter C. Systems thinking among school middle leaders. Educ Manag Admin Lead. (2017) 45:699–718. doi: 10.1177/17411432156179

27. Jaradat RM, Keating CB. Systems thinking capacity: implications and challenges for complex system governance development. Int J Syst Syst Eng. (2016) 7:75–94. doi: 10.1504/IJSSE.2016.076130

28. Jaradat RM. Complex system governance requires systems thinking-how to find systems thinkers. Int J Syst Syst Eng. (2015) 6:53–70. doi: 10.1504/IJSSE.2015.068813

29. Castelle KM, Jaradat RM. Development of an instrument to assess capacity for systems thinking. Proc Computer Sci. (2016) 95:80–6. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2016.09.296

30. Grohs JR, Kirk GR, Soledad MM, Knight DB. Assessing systems thinking: a tool to measure complex reasoning through ill-structured problems. Think Skills Creat. (2018) 28:110–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2018.03.003

31. Richmond B. The “thinking” in systems thinking: how can we make it easier to master. Syst Thinker. (1997) 8:1–5.

32. Richmond B. Systems thinking: critical thinking skills for the 1990s and beyond. Syst Dyn Rev. (1993) 9:113–33. doi: 10.1002/sdr.4260090203

33. Maani KE, Maharaj V. Links between systems thinking and complex decision making. Syst Dyn Rev. (2004) 20:21–48. doi: 10.1002/sdr.281

35. Checkland PB. Soft systems methodology*. Hum Syst Manag. (1989) 8:273–89. doi: 10.3233/HSM-1989-8405

36. Williams B, Hummelbrunner R. Chapter 14: soft systems methodology. In: Systems Concepts in Action: a Practitioner's Toolkit. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press United States (2010).

37. Augustsson H, Churruca K, Braithwaite J. Re-energising the way we manage change in healthcare: the case for soft systems methodology and its application to evidence-based practice. BMC Health Serv Res. (2019) 19:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4508-0

38. Senge PM, Sterman JD. Systems thinking and organizational learning: acting locally and thinking globally in the organization of the future. Eur J Operat Res. (1992) 59:137–50. doi: 10.1016/0377-2217(92)90011-W

39. Lamb CT, Rhodes DH. Collaborative systems thinking: uncovering the rules. IEEE Aerospace Elect Syst Magaz. (2010) 25:4–10. doi: 10.1109/MAES.2010.5638799

40. Lamb CT, Nightingale D, Rhodes DH. Collaborative systems thinking: towards an understanding of team-level systems thinking. In: 6th Conference on Systems Engineering Research. Redondo Beach, CA (2008). Available online at: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/84133

41. Resnick LB. Shared cognition: thinking as social practice. In: Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition. American Psychological Association (1991). doi: 10.1037/10096-018

42. Jeffery AB, Maes JD, Bratton-Jeffery MF. Improving team decision-making performance with collaborative modeling. Team Perf Manag. (2005) 11:40–50. doi: 10.1108/13527590510584311

43. Jordan ME, Lanham HJ, Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stange KC, et al. The role of conversation in health care interventions: enabling sense making and learning. Implement Sci. (2009) 4:1–3. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-15

44. Senge PM. The Fifth Discipline, the Art And Practice of the Learning Organization. London: Random House (1990).

45. Nyström ME, Tolf S, Strehlenert H. Sense-making, mutual learning and cognitive shifts when applying systems thinking in public health - examples from Sweden: Comment on “what can policymakers get out of systems thinking? Policy partners' experiences of a systems-focused research collaboration in preventive health”. Int J Health Pol Manag. (2021) 10:338. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.106

46. Nyström ME, Terris DD, Sparring V, Tolf S, Brown CR. Perceived organizational problems in health care: a pilot test of the structured problem and success inventory. Qual Manag Health Care. (2012) 2193–203. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0b013e31824d18ff

47. Smith LS, Wilkins NJ, McClure RJ. A systemic approach to achieving population-level impact in injury and violence prevention. Syst Res Behav Sci. (2021) 38:21–30. doi: 10.1002/sres.2668

48. Lavinghouze SR, Snyder K, Rieker PP. The component model of infrastructure: a practical approach to understanding public health program infrastructure. Am J Public Health. (2014) 104:e14–24. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302033

49. de Savigny D, Adams T. Systems Thinking for Health Systems Strengthening. World Health Organization (2009).

50. Svensk Förening för Obstetrik och Gynekologi (SFOG). Mödrahälsovård, Sexuell och Reproduktiv Hälsa. SFOG Report (2008). Available online at: https://www.sfog.se/natupplaga/ARG76web43658b6c2-849e-47ab-99fa-52e8ac993b7d.pdf (accessed March 5, 2022).

51. Nyström ME, Strehlenert H, Hansson J, Hasson H. Strategies to facilitate implementation and sustainability of large system transformations: a case study of a national program for improving quality of care for elderly people. BMC Health Serv Res. (2014) 14:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-401

52. Strehlenert H, Richter-Sundberg L, Nyström ME, Hasson H. Evidence-informed policy formulation and implementation: a comparative case study of two national policies for improving health and social care in Sweden. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:169. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0359-1

53. Strehlenert H, Hansson J, Nyström ME, Hasson H. Implementation of a national policy for improving health and social care: a comparative case study using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Health Serv Res. (2019) 19:730. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4591-2

54. Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner,. Strategier för kvinnors hälsa - före, under och efter graviditet [Strategies for women's health - before, during after pregnancy]. Stockholm: Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner (2019). Available online at: https://skr.se/skr/tjanster/rapporterochskrifter/publikationer/strategierforkvinnorshalsa.65557.html (accessed March 1, 2022).

55. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

56. Roberts N. Wicked problems and network approaches to resolution. Int Public Manag Rev. (2000) 1:1–19 Retrieved from: https://ipmr.net/index.php/ipmr/article/view/175

57. Brugha R, Varvasovszky Z. Stakeholder analysis: a review. Health Pol Plan. (2000) 15:239–46. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.3.338

58. Martinsuo M, Hoverfâlt P. Change program management: toward a capability for managing value-oriented, integrated multi-project change in its context. Int J Proj Manag. (2018) 36:134–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.04.018

59. Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117

61. Argyris C, Schön DA. Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method and Practice. Reading PA: Addison Wesley (1996).

62. Dentoni D, Bitzer V, Schouten G. Harnessing wicked problems in multi-stakeholder partnerships. J Bus Ethics. (2018) 150:333–56. doi: 10.1007/s10551-018-3858-6

Keywords: systems thinking, healthcare improvement, policy implementation, public health, healthcare services

Citation: Nyström ME, Tolf S, Sparring V and Strehlenert H (2023) Systems thinking in practice when implementing a national policy program for the improvement of women's healthcare. Front. Public Health 11:957653. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.957653

Received: 31 May 2022; Accepted: 31 August 2023;

Published: 29 September 2023.

Edited by:

Maria Del Rocio Saenz, University of Costa Rica, Costa RicaReviewed by:

Christopher Mierow Maylahn, New York State Department of Health, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Nyström, Tolf, Sparring and Strehlenert. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Monica E. Nyström, bW9uaWNhLm55c3Ryb21Aa2kuc2U=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.