- 1The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health, Houston, TX, United States

- 2Center for Health Promotion and Prevention Research, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health, Houston, TX, United States

- 3Southwest Center for Occupational and Environmental Health, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health, Houston, TX, United States

- 4The University of Texas Health Science Center School of Public Health, Dallas, TX, United States

- 5The University of Texas Health Science Center School of Public Health, Brownsville, TX, United States

- 6Institute for Implementation Science, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, United States

Background: Diabetes is considered one of the most prevalent and preventable chronic health conditions in the United States. Research has shown that evidence-based prevention measures and lifestyle changes can help lower the risk of developing diabetes. The National Diabetes Prevention Program (National DPP) is an evidence-based program recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; it is designed to reduce diabetes risk through intensive group counseling in nutrition, physical activity, and behavioral management. Factors known to influence this program’s implementation, especially in primary care settings, have included limited awareness of the program, lack of standard clinical processes to facilitate referrals, and limited reimbursement incentives to support program delivery. A framework or approach that can address these and other barriers of practice is needed.

Objective: We used Implementation Mapping, a systematic planning framework, to plan for the adoption, implementation, and maintenance of the National DPP in primary care clinics in the Greater Houston area. We followed the framework’s five iterative tasks to develop strategies that helped to increase awareness and adoption of the National DPP and facilitate program implementation.

Methods: We conducted a needs assessment survey and interviews with participating clinics. We identified clinic personnel who were responsible for program use, including adopters, implementers, maintainers, and potential facilitators and barriers to program implementation. The performance objectives, or sub-behaviors necessary to achieve each clinic’s goals, were identified for each stage of implementation. We used classic behavioral science theory and dissemination and implementation models and frameworks to identify the determinants of program adoption, implementation, and maintenance. Evidence- and theory-based methods were selected and operationalized into tailored strategies that were executed in the four participating clinic sites. Implementation outcomes are being measured by several different approaches. Electronic Health Records (EHR) will measure referral rates to the National DPP. Surveys will be used to assess the level of the clinic providers and staff’s acceptability, appropriateness of use, feasibility, and usefulness of the National DPP, and aggregate biometric data will measure the level of the clinic’s disease management of prediabetes and diabetes.

Results: Participating clinics included a Federally Qualified Health Center, a rural health center, and two private practices. Most personnel, including the leadership at the four clinic sites, were not aware of the National DPP. Steps for planning implementation strategies included the development of performance objectives (implementation actions) and identifying psychosocial and contextual implementation determinants. Implementation strategies included provider-to-provider education, electronic health record optimization, and the development of implementation protocols and materials (e.g., clinic project plan, policies).

Conclusion: The National DPP has been shown to help prevent or delay the development of diabetes among at-risk patients. Yet, there remain many challenges to program implementation. The Implementation Mapping framework helped to systematically identify implementation barriers and facilitators and to design strategies to address them. To further advance diabetes prevention, future program, and research efforts should examine and promote other strategies such as increased reimbursement or use of incentives and a better billing infrastructure to assist in the scale and spread of the National DPP across the U.S.

Introduction

Prediabetes is one of the most prevalent chronic health conditions diagnosed in the United States (U.S.), estimated to affect 88 million individuals (1). Nearly 40% of those diagnosed with prediabetes will likely be diagnosed with diabetes within 4 years (2). This progression can be largely prevented through behavioral lifestyle changes that incorporate a sustainable healthy diet and physical activity resulting in a 5–7% weight loss (2, 3). The National Diabetes Prevention Program (National DPP) is an effective, evidence-based lifestyle change program shown to reduce the incidence of diabetes (4, 5). The National DPP includes a 22-h curriculum delivered via group sessions over the course of 12 months and focuses on helping participants make healthy lifestyle changes including improving nutrition, physical activity, and psychological well-being to achieve sustainable weight loss (5, 6). Individuals eligible to participate in the National DPP are typically referred to the program by health care providers but they can also self-enroll (7).

Although the National DPP has shown to be effective in delaying diabetes diagnoses (8, 9), its widespread adoption and implementation have been hindered by multiple barriers (10–12). At the provider level, barriers include limited awareness of the program among clinic staff and/or healthcare providers, limited provider referrals to the program, and lack of provider buy-in (10–12). In their assessment of multi-level barriers to program implementation, Baucom et al. (12) identified clinicians’ lack of knowledge about the National DPP as the primary barrier to referring patients. At the clinic level, limited use of electronic health records (EHR) features to assist with referrals, lack of reimbursement or incentive structures to support National DPP referrals and delivery, and lack of health educators to deliver the program are impediments to wider adoption and implementation of the program (13). Patient-level barriers include time, cost, and inconvenient program locations (12). Raising provider and patient awareness about the National DPP and increasing “brand recognition” remains an important priority to increase participation in the program.

Investigators from The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health Center for Health Promotion and Prevention Research and the Center for Quality Health IT Improvement at the School of Biomedical Informatics (hereafter referred to as UTHealth team) partnered with the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) to carry out a five-year project funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The goal was to use Implementation Mapping to design and implement strategies to implement diabetes prevention guidelines and the National DPP in primary care clinics located in the DSHS Public Health Region (PHR) 6/5S (Gulf Coast). This process has real-world applications that can guide healthcare institutions in their efforts to scale the National DPP in their communities.

Methods

The UTHealth team first recruited primary care clinics to participate in the project and identified partner National DPP sites. The UTHealth team and clinic partners (hereafter “team”) then used Implementation Mapping, a systematic planning framework, to develop strategies to adopt, implement, and sustain a referral system to National DPP sites (14).

Clinic recruitment

The UTHealth team recruited primary care clinics to participate in the project using purposeful sampling based on their location within the Texas DSHS PHR 6/5S and their previous relationship with the UTHealth Center for Quality Health IT Improvement. UTHealth team members (e.g., research coordinators, and quality improvement specialists) created a list of clinics in the selected public health region that were currently or had previously received quality improvement, data analysis, and reporting services from the Center for Quality Health IT Improvement. Clinics’ leadership staff from the identified clinics were contacted by phone and email and were provided with a brief overview of the project, including the goal of assisting clinics with National DPP implementation. Once a clinic indicated interest in participating, an introductory teleconference was scheduled with the clinic leadership team. During the introductory meeting, the DPP program was described, and clinic staff responded to unstructured questions to learn more about the clinic’s priorities and its overall diabetes prevention and management goals.

Partnering with National DPP

The UTHealth team identified and recruited CDC-recognized National DPPs based on their coverage area within the Texas DSHS PHR 6/5S, ability to offer virtual classes, cost to participants, and ability to provide program materials in English and Spanish. As the initial step in the recruitment process, the UTHealth team created a list of CDC-recognized National DPPs registered on the CDC website located in the selected public health region. Additional National DPPs were identified in advertisements in the American Medical Association newsletter and through referrals from the funding agency. The UTHealth team reached out to each program to gauge their interest in partnering with one of the participating clinics. The recruitment process focused primarily on National DPP that could offer classes that could meet the needs of the clinics’ patient population who were primarily under or uninsured and Spanish-speaking. Thus, the selected National DPPS offered classes at no cost to the participants (i.e., their program was already funded by public or private grants) and had classes in English and Spanish. Furthermore, since this implementation started while social distancing restrictions were still in place due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we selected programs offering remote or in-person classes. The National DPPs selected who partner with the clinics were a City of Houston-sponsored program, a Silicon Valley-based program, and a local private practice.

Strategy planning using implementation Mapping

Implementation Mapping incorporates theory, stakeholder input, and data to guide implementation strategy development (15). The process leads planners through five iterative tasks: (1) conduct a needs and assets assessment and identify program adopters, implementers, and maintainers; (2) identify adoption, implementation, and maintenance outcomes, performance objectives (i.e., specific tasks or sub-behaviors required to adopt, implement, and maintain a program), and determinants, and create matrices of change objectives (i.e., changes required in each determinant that will influence the achievement of each performance objective); (3) select evidence- and/or theory-based methods and identify or develop implementation strategies; (4) produce implementation protocol and materials; and (5) evaluate implementation outcomes (14).

Task 1: Conduct a needs and assets assessment and identify program adopters, implementers, maintainers, and champions

Leaders at the four participating clinics completed an online 56-item survey and 60-min interviews to assess: (1) awareness of National DPP; (2) barriers to National DPP adoption, implementation, and maintenance; (3) clinics’ approaches to prediabetes diagnosis and management; (4) the use of clinical decision support for chronic disease management and technological capabilities; (5) existing referral systems to external lifestyle change programs; and (6) use and capacity of the clinic’s EHR system. Clinic decision support (CDS) is any EHR tool designed to enhance decision-making in the clinical workflow. Tools may include alerts and reminders to care providers and patients, clinical guidelines, condition-specific order sets, focused patient data reports and summaries, documentation templates, diagnostic support, and contextually relevant reference information. Upon completion of the needs and assets assessment survey and interviews, the UTHealth team worked with each clinic to develop and sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) indicating an intent to adopt the National DPP.

The team defined the following roles responsible for adopting and integrating National DPPs into clinic processes at each clinic site. A program adopter was defined as a clinic staff member with the decision-making authority to start using a National DPP program (i.e., clinic leadership) and/or a staff member (i.e., clinic administration) directly involved in deciding to set up program referral processes. A program implementer was a staff member (i.e., physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant) responsible for making program referrals and/or a clinic administrator responsible for educating staff. A program champion (i.e., a health care provider or clinic administration) was an implementer that advocated for promoting the National DPP among other clinic staff (e.g., communicating with technical support personnel to ensure that EHR referral procedures were in place and fit the goal of being able to refer patients to a program in a timely manner). Finally, program maintainers (i.e., clinic leaders from administration, health care providers, and National DPP providers) were those who were responsible for ensuring that the program was maintained over time.

Task 2: Identify adoption, implementation, and maintenance outcomes, performance objectives and determinants, and create matrices of change objectives

In Task 2, the team stated the adoption, implementation, and maintenance outcomes, and performance objectives associated with each outcome. The overall goal is a statement that clinics intend to adopt, implement, and maintain a program while adoption, implementation, and maintenance outcomes are specific to each adopter, implementer, and maintainer. Performance objectives are the specific actions or sub-steps required to adopt, implement, and maintain the National DPP in each clinic (14). To create performance objectives, the team asked, “who needs to do what to ensure that the program is adopted?” with similar questions asked for implementation and maintenance.

Next, the UTHealth team identified determinants influencing adoption, implementation, and maintenance. Determinants answer the question why an adopter, implementer, or maintainer would complete performance objectives and outcomes (14). For example, “why would clinic leadership adopt the National DPP at their clinic?” The UTHealth team identified an initial list of determinants based on Task 1 data, a review of the literature, health behavior theories, and implementation and dissemination frameworks, and then provided clinic stakeholders with the list and solicited feedback to select final determinants. Stakeholders rated determinants based on perceived importance and changeability.

Finally, the team created a matrix of change objectives by crossing performance objectives (rows) with determinants (columns). Change objectives in each cell stated what needs to change in a determinant to achieve the performance objective and provided a blueprint for identifying, selecting, or developing implementation strategies (14).

Task 3: Select theory-based methods and identify implementation strategies

In Task 3, the team collaborated to identify evidence- and theory-based methods targeting determinants. Evidence- and theory-based methods are techniques influencing determinants and may work at the individual- and/or clinic-levels (14). Collaboration to identify methods included brainstorming, identifying previously successful methods in implementing organizational change at each clinic, and reviewing the literature. Next, the team operationalized methods as implementation strategies, the specific approaches to enhance National DPP adoption, implementation, and maintenance in participating clinics (14, 16, 17).

Task 4: Produce implementation protocols and materials

In Task 4, the team produced protocols and materials to facilitate National DPP adoption, implementation, and maintenance. Clinic action plans and supporting materials were developed and discussed during monthly TA calls to ensure the clinics’ feedback was incorporated. Clinic action plans delineated the implementation timeline. Supporting materials were developed and tailored to meet the needs of the clinics (e.g., staff, EHR capability, and patient population).

Task 5: Evaluate implementation outcomes

Data collection for evaluation is ongoing. Evaluation will include assessment of National DPP referrals via the EHR and adoption and implementation outcomes including program appropriateness, acceptability, feasibility, and fidelity measured via healthcare provider and clinic leadership surveys (15). Evaluation methods will include clinic leadership and healthcare provider surveys and document review of meeting notes, EHR screen captures, workflow/process flowcharts, and clinic policies.

Results

Clinic and National DPP partnerships

Four clinics meeting eligibility criteria agreed to participate. These included: Clinic A, a federally qualified health center (FQHC) with four clinic sites; Clinic B, a Rural Health Center (RHC); and Clinics C and D, two private community-based healthcare clinics. FQHCs are community-based health facilities eligible to receive federal funds because they provide affordable services to patients based on their ability to pay (18). RHCs are clinics that serve both private and publicly insured populations in rural, underserved areas; they can be for-profit or non-profit clinics (19). All participating clinics serve diverse patient populations and provide services to primarily under and uninsured patients with limited access to healthcare. The UTHealth team worked closely with stakeholders from each clinic including clinic leadership (e.g., chief executive officer, chief operations officer, chief medical officer, chief nursing officer); clinic administrators (e.g., technology/data analyst, practice administrator, practice manager); and health care providers (e.g., physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants).

The UTHealth team established partnerships with three National DPP, all of which were providing only virtual sessions as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The National DPPs were paired (i.e., the clinic needs matched with the program services) with clinics based on the capacity and preferences of the two partnering entities. For example, one clinic was paired with a local National DPP that offered face-to-face classes in English and Spanish reflecting the language needs of the clinic’s patient population.

Implementation mapping

Task 1: Conduct a needs and assets assessment and identify program adopters, implementers, maintainers, and champions

Conduct a needs and assets assessment

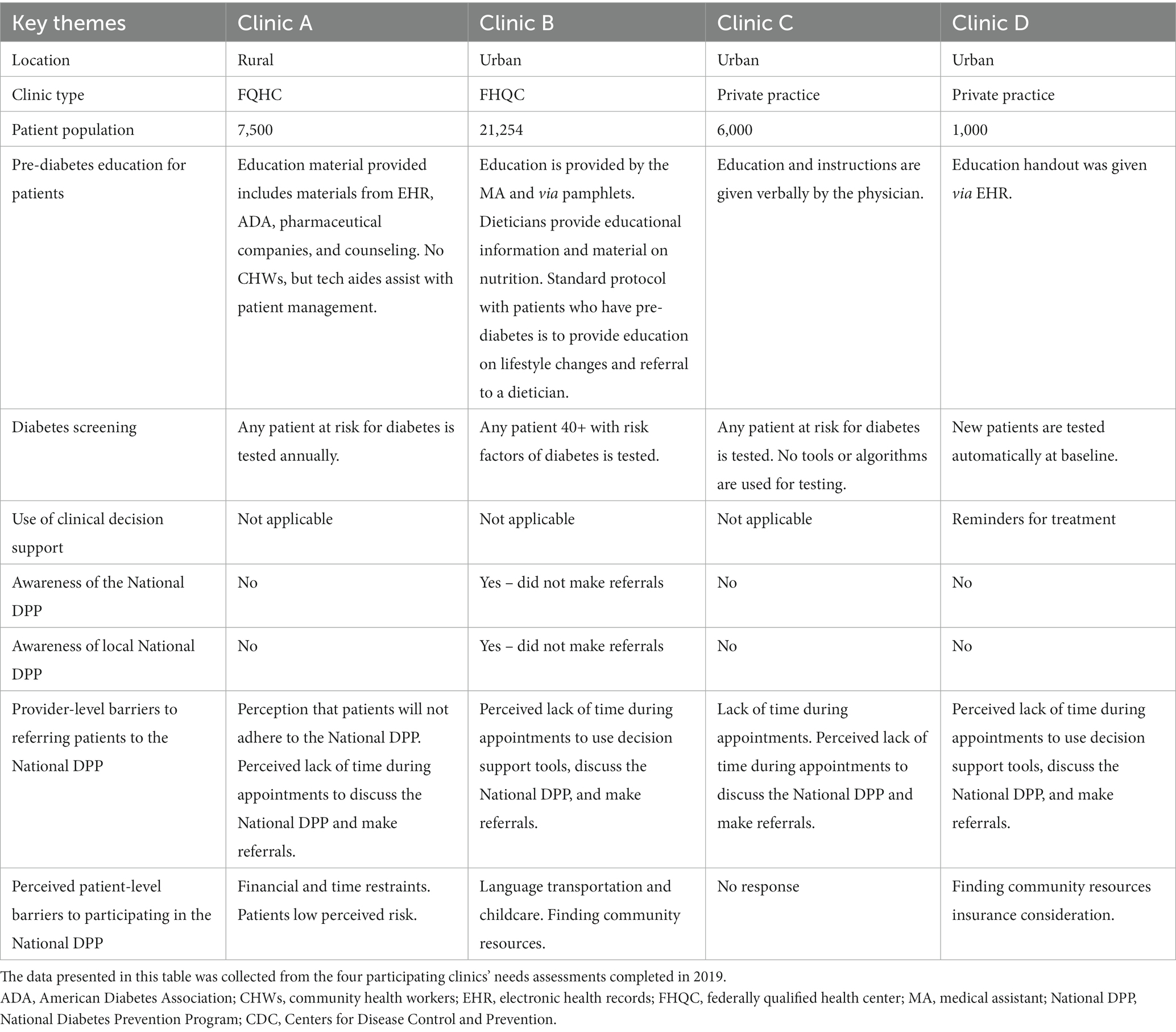

Table 1 summarizes the results of the clinics’ needs assessment survey and interviews. Each clinic provided some form of patient education about diabetes prevention, although sources for materials differed by clinic. Screening for the risk of diabetes also varied by clinic, and only one clinic used clinical decision support to identify patients with prediabetes. Three of the four clinics were not aware of the National DPP or of its availability in their communities.

Table 1. Summary of the 2019 needs assessment survey and interview responses from clinics participating in the National Diabetes Prevention Program.

Clinic stakeholders identified the following two provider-level barriers to referring patients to the National DPP: (1) a perceived lack of time during appointments for the provider to use decision support tools, discuss the National DPP, and make referrals; and (2) the provider perception that patients will not adhere to the National DPP. The clinic stakeholders identified the following six perceived patient barriers to participating in a National DPP: (1) low understanding of diabetes risk perception; (2) language barriers; (3) financial and time constraints; (4) transportation difficulties; (5) childcare concerns; and (6) lack of health insurance.

Clinics reported using different EHRs including NextGen, Athena, Practice Fusion, and eClinicalWorks. Four clinics’ digital systems were not certified EHR products, had basic capabilities for setting appointments and billing, and were connected through the regional health information exchange and electronic provider-to-provider (P2P) referral networks. Most clinics used reminders for the treatment of diabetes as a CDS tool.

Identify program adopters, implementers, champions, and maintainers

Program adopters at clinics included clinic leadership (i.e., chief executive officer, chief operations officer, chief medical officer, and chief nursing officer). Program implementers included clinic administration staff (i.e., technology/data analyst, practice administrator, and practice manager), and healthcare providers (i.e., physicians making referrals, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants). Program champions were identified from both health care providers and clinic administration staff in each clinic. Finally, program maintainers were identified from leadership (i.e., chief executive officer, chief operations officer, chief medical officer, and chief nursing officer), clinic administration (i.e., technology/data analyst, practice administrator, and practice manager), and healthcare providers (i.e., physicians making referrals, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants).

Task 2: Identify National DPP adoption, implementation, and maintenance outcomes, performance objectives, and determinants and create matrices of change objectives

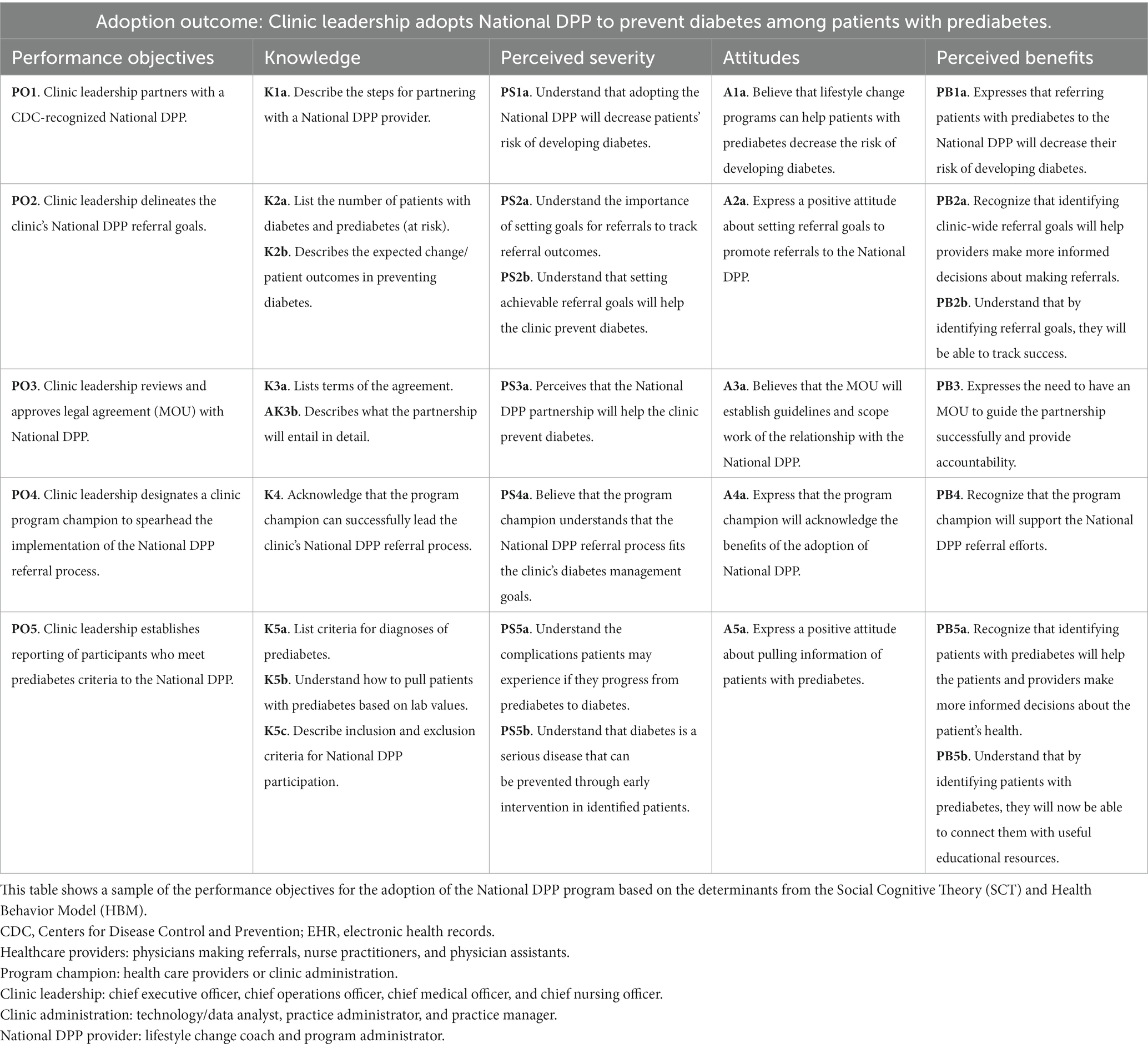

The identified outcomes were to adopt, implement, and maintain guidelines for diabetes prevention and the National DPP. Table 2 lists all adoption, implementation, and maintenance outcomes and performance objectives.

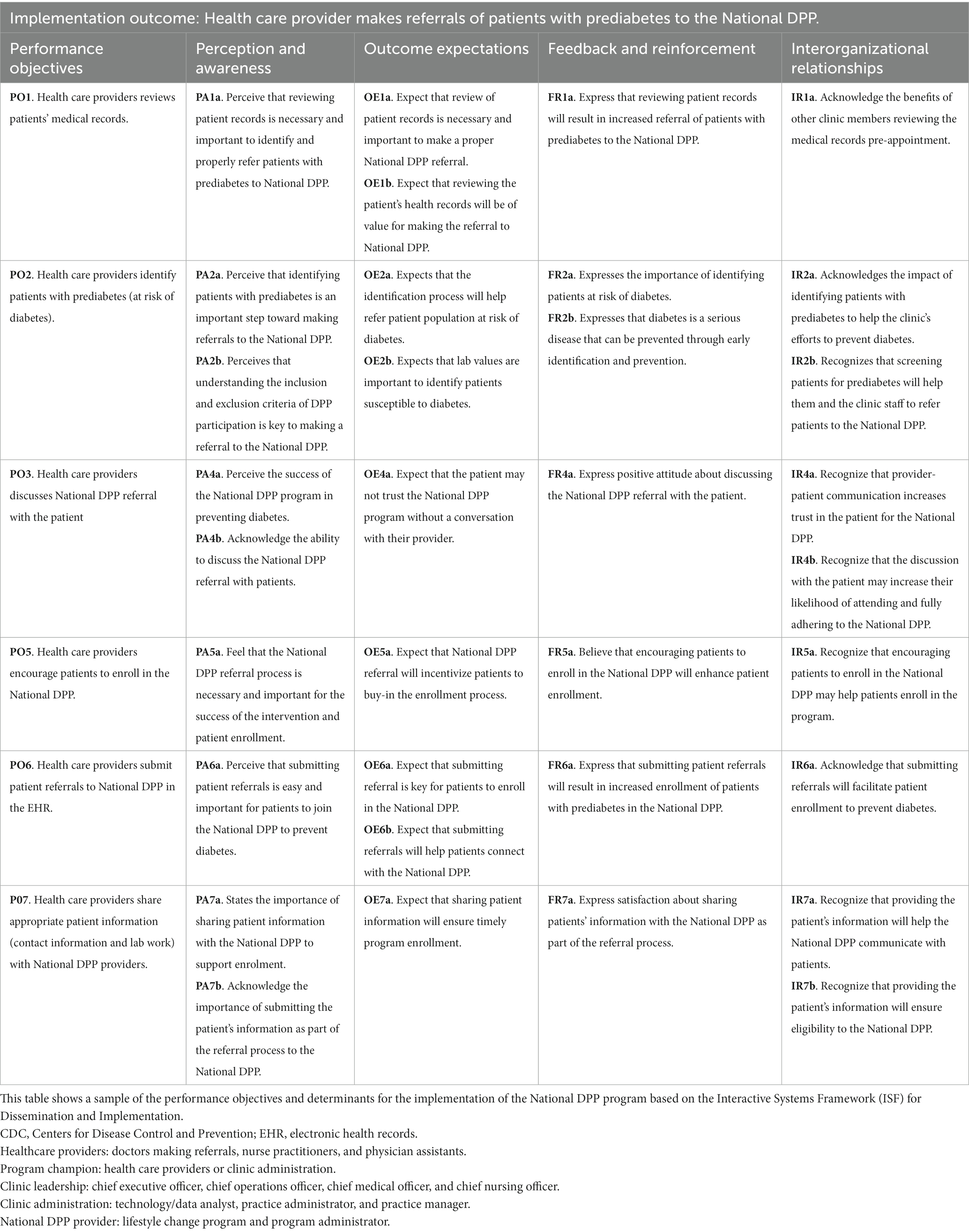

Adoption, implementation, and maintenance determinants that clinic stakeholders considered important and changeable included those from the Social Cognitive Theory (20) and Interactive Systems Framework (21). These included: stakeholder and providers’ attitudes toward the importance of diabetes prevention, knowledge about the program, perceived severity of failing to refer prediabetic patients, perceived program benefits, perceived program effectiveness, staff capacity and motivation to overcome barriers, and staff capacity and motivation to implement the program. The team crossed all determinants with performance objectives to create change objectives. Tables 3, 4 provide example matrices of change objectives for National DPP adoption and implementation in clinics.

Table 3. Sample matrices of change objectives for the adoption of the National Diabetes Prevention Program among the participating clinics in Texas, United States.

Table 4. Sample matrices of change objectives for the implementation of the National Diabetes Prevention Program among participating clinics in Texas, United States.

Task 3: Select theory-based methods and identify implementation strategies

The team identified three primary evidence- and theory-based methods to influence determinants: enhancing network linkages; participatory problem solving, providing technical assistance, facilitation, goal-setting, framing, tailoring, and guided practice.

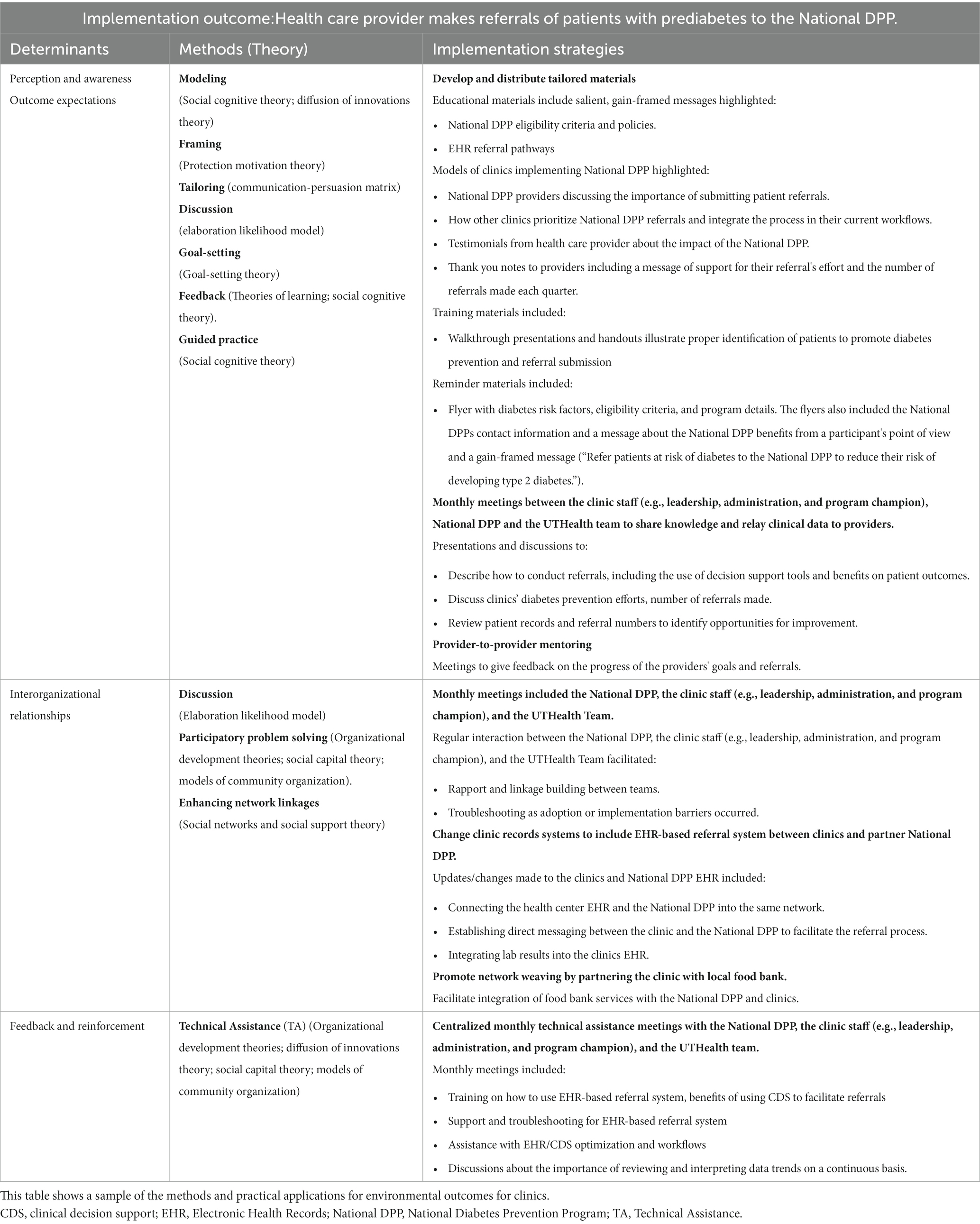

Methods were operationalized as specific implementation strategies to increase National DPP adoption, implementation, and maintenance. These included: (1) developing and distributing providing education materials; (2) monthly meetings between the clinic staff, the National DPP provider, and the UTHealth team; (3) changing clinic records systems to include an EHR-based referral system between clinics and partner National DPPs; and (4) provider-to-provider mentoring. Table 5 depicts determinants, linked theoretical methods, and implementation strategies operationalizing the methods.

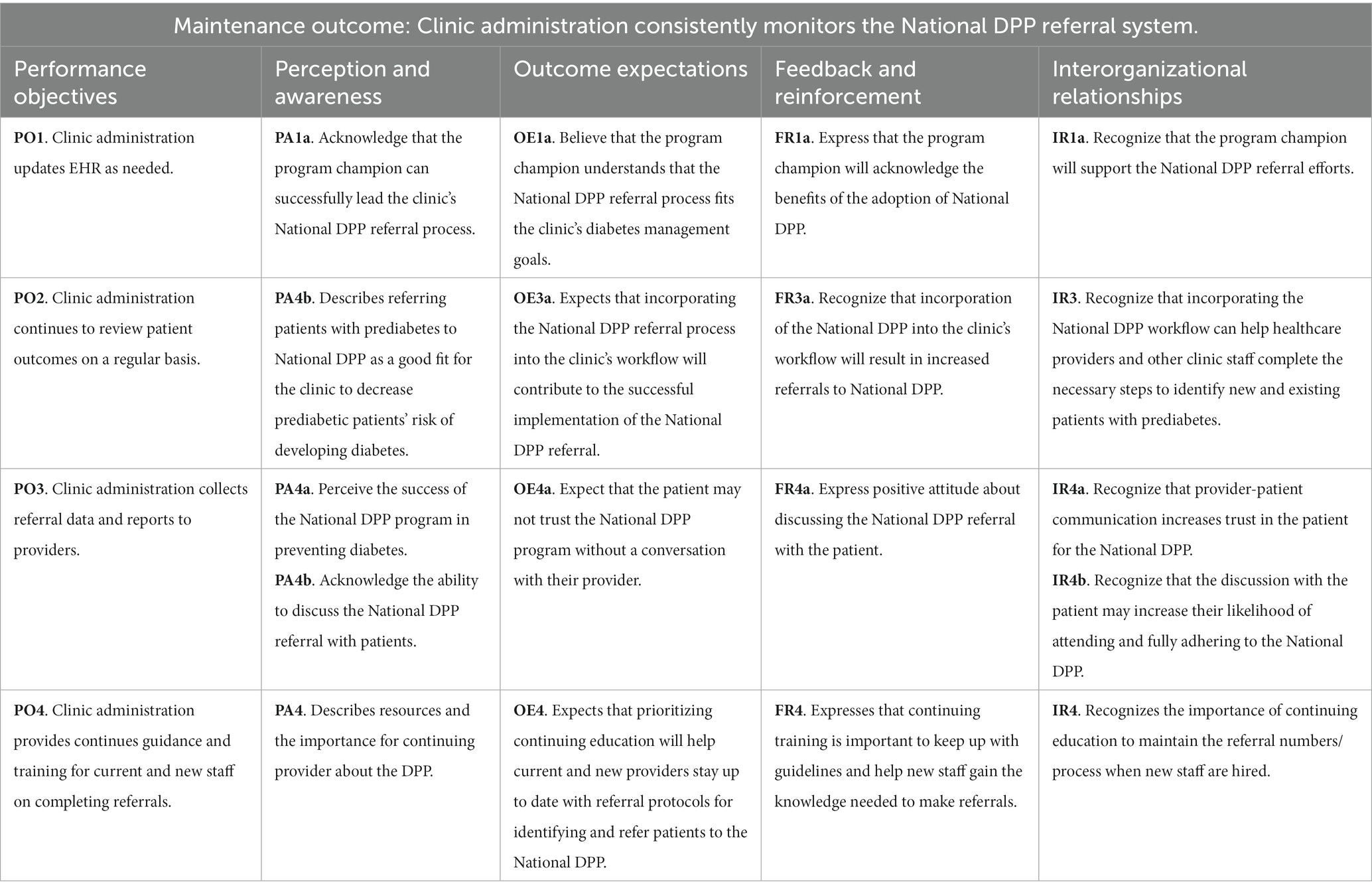

Table 5. Sample matrices of change objectives for the maintenance of the National Diabetes Prevention Program among participating clinics in Texas, United States.

Task 4: Produce implementation protocol and materials

Once the referral network was established between the clinics and the National DPP providers, the partnering program began to contact and enroll participants. Through participatory planning sessions with each clinic and its assigned program provider, we identified the need for introductory sessions, referred to as “Session 0,” to help participants become familiar with the virtual platform used by the National DPPs. The partnering program established a virtual meeting, assigned participants to 15-min time slots, and provided guidance to the team on what aspects of the program were critical to communicate to participants. The clinic’s program champion, the program’s lifestyle change coaches, and the UTHealth team facilitated Session 0 by introducing participants to the National DPP, connecting them to their coach, and answering any questions about the virtual platform (Table 6).

During planning sessions with the clinics, the team identified a need for materials to educate and inform patients and healthcare providers about the National DPP and the importance of program referrals. Collaborating with each clinic, the team developed National DPP referral policies, workflows, flyers and posters. Clinical workflows delineated who did what during the rooming, identification, referral, and follow-up process of patients eligible to the National DPP. Clinical pathways were captured during one-on-one TA calls with the clinic’s EHR specialist and a step-by-step document of the EHR referral process was shared with the clinic staff to orient providers making referrals using the clinics EHR. The flyers and posters were displayed on the clinics’ websites and within the clinics’ waiting and exam rooms. Flyers for providers included messaging about National DPP eligibility criteria and the selected National DPP provider(s) that had partnered with the clinic. In contrast to provider flyers, patient flyers provided an overview of the program and prompted them to speak with their health care provider about the program. While creating these materials, the team focused on integrating messaging that would address the change objectives in the matrices. For instance, an infographic was developed for clinic staff to use and post on their intranet that prompted providers to ask, “Are your patients at risk for diabetes?” and then prompted them to act with the call to action, “Refer patients at risk of diabetes to the National DPP to reduce their risk of developing type 2 diabetes.” Which was reinforced with the eligibility criteria of the program and a description of the benefits provided by the program. All of these developed protocol documents and materials were co-created and clinic staff provided the final review and approval prior to implementation.

Task 5: Evaluate implementation outcomes

Evaluation is ongoing and future manuscripts will report National DPP referrals made, adoption outcomes, and implementation outcomes.

Discussion

Successful integration of the National DPP into the U.S. healthcare system is critically needed to counter the rapidly rising incidence of diabetes nationwide. By utilizing the Implementation Mapping planning framework, our coalition of primary care clinics and National DPP providers implement strategies to implement diabetes prevention guidelines and the National DPP with the intent of improving the identification of people with prediabetes and refer them to CDC-recognized lifestyle change programs for Type 2 diabetes prevention.

Through systematic planning using Implementation Mapping, we designed implementation strategies to address barriers, build capacity, and create systems to foster the adoption and implementation (10–12). We chose evidence- and theory-based methods and practical applications to improve acceptance and uptake of the implementation.

In the present project, Implementation Mapping proved to be a useful, systematic approach for identifying POs centered around the multiple actor-specific tasks required to ensure proper integration of the National DPP into the four clinics’ workflows. The Implementation Mapping framework helped us map practical applications to address determinants needed to achieve the POs needed to promote and identify local National DPP providers, promote the program’s value to clinic patients and providers, and optimize EHR capabilities to effectively communicate referrals between clinics and National DPP providers.

Strengths and limitations

An important strength of this project was the experience and background of a collaborative transdisciplinary team including engaged partners. Team members included those experienced in using Implementation Mapping to scale preventive health programs, and others skilled in providing technical assistance on EHRs and referral pathways for clinical use. This rich history of collaboration and capabilities were instrumental in building rapport and trust with the four participating clinics, and in facilitating culturally appropriate support and materials that were individualized for each of the clinics.

A limitation of the project was the design of the needs assessment. The original survey and interviews did not ask about the clinics’ level of readiness nor their capacity to adopt and implement the referral procedures that are necessary to refer patients to National DPP providers. The focus of the project was implementation and promotion of the National DPP referrals. However, gaps in knowledge of the readiness and capacity of the clinics likely impeded some of the actions that could be taken during the Implementation Mapping process (22). As a result, the UTHealth team suggested examining inner setting factors that impact the sustainability of the National DPP and future studies.

Conclusion

Diabetes is among the most prevalent chronic diseases in the U.S. This condition has devastating impacts on the quality of life of patients, with these negative consequences ranging from premature death and coexisting morbidity from complications to loss of work productivity and high health care costs (15, 23, 24). Yet, identifying individuals who are at risk for diabetes (i.e., people with prediabetes and/or a history of gestational diabetes) and helping them lower this risk have not been priorities for many health systems, even though evidence-based programs like the National DPP are available to patients and are now reimbursable under Medicare and several state Medicaid plans (24). Emerging research on program implementation suggests that patient and health care providers limited knowledge of the National DPP, along with the difficulties in maintaining patient attendance, and the sustainability of referrals process to the National DPP have been barriers to the wider use of this program (12). The implementation strategies developed helped clinics overcome barriers by educating providers about the National DPP and its benefits on diabetes prevention, promoting patient education, and facilitating the use of EHRs (12).

Enrollment is just the first step in this process, and adherence is also critical. There is a need for studies that explore how to increase adherence and how implementation could include use of incentives. For example, the UTHealth team is currently piloting an intervention that includes participation incentives to better understand its effect on patient adherence to promote National DPP attendance (12). The program demonstrated how Implementation Mapping can be used to help clinics and National DPP providers overcome implementation barriers. In the long term, healthcare leaders can use experiences of programs such as these to expand and help improve the quality of National DPP delivery and to increase its access for patients who are at high risk of developing diabetes.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subject University of Texas Health Science Center. The ethics committee waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation.

Author contributions

WP directed research directly and helped study design and wrote manuscript. PM and FV-H project manager, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed extensively. CP project manager, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed. SB worked in project, wrote manuscript, and reviewed. NH designed the project, reviewed implementation mapping process, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed. SR reviewed implementation mapping manuscript. PF worked in project and reviewed. BR and JM reviewed manuscript. RC oversaw project and reviewed. MF and PI were responsible project and wrote and reviewed manuscript. GW a reviewer of the manuscript requested an extensive reorganization of the methods and discussion section of the manuscript. I played a key role in this organization process making the manuscript which included rewriting parts, adding additional literature citations and adding new dimensions to the discussion. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This manuscript was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial assistance award totaling $3.8 million with 100 percent funded by CDC/HHS (project No. HHS001000100001). The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by Texas DSHS (Department of State Health Services), CDC/HHS, or the US Government. This research was partially funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (Award No. T42OH008421) through the Southwest Center for Occupational and Environmental Health (SWCOEH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge our partners, the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) and the affiliated clinics and National DPP programs.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National diabetes statistics report 2020: estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. (2022). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf (Accessed March 2, 2023).

2. Tuso, P . Prediabetes and lifestyle modification: time to prevent a preventable disease. Perm J. (2014) 18:88–93. doi: 10.7812/TPP/14-002

3. Salinardi, TC, Batra, P, Roberts, SB, Urban, LE, Robinson, LM, Pittas, AG, et al. Lifestyle intervention reduces body weight and improves cardiometabolic risk factors in worksites. Am J Clin Nutr. (2013) 97:667–76. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.046995

4. Knowler, WC, Barrett-Connor, E, Fowler, SE, Hamman, RF, Lachin, JM, Walker, EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. (2002) 346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512

5. Albright, AL, and Gregg, EW. Preventing type 2 diabetes in communities across the U.S.: the National Diabetes Prevention Program. Am J Prev Med. (2013) 44:S346–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.009

6. Center for Disease Control and Prevention . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention diabetes prevention recognition program standards and operating procedures. (2021). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/pdf/dprp-standards.pdf (Accessed March 2, 2023).

7. Neamah, HH, Kuhlmann, AKS, and Tabak, RG. Effectiveness of program modification strategies of the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Educ. (2016) 42:153–65. doi: 10.1177/0145721716630386

8. Ratner, RE, Diabetes Prevention Program Research . An update on the diabetes prevention program. Endocr Pract. (2006) 12 Suppl 1:20–4. doi: 10.4158/EP.12.S1.20

9. Ali, MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui, J, and Williamson, DF. How effective were lifestyle interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the diabetes prevention program? Health Aff. (2012) 31:67–75. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1009

10. Whittemore, R . A systematic review of the translational research on the diabetes prevention program. Behav Med Pract Policy Res. (2011) 1:480–91. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0062-y

11. Carroll, J, Winters, P, Fiscella, K, Williams, G, Bauch, J, Clark, L, et al. Process evaluation of practice-based diabetes prevention programs. Diabetes Educ. (2015) 41:271–9. doi: 10.1177/0145721715572444

12. Baucom, KJW, Pershing, ML, Dwenger, KM, Karasawa, M, Cohan, JN, and Ozanne, EM. Barriers and facilitators to enrollment and retention in the National Diabetes Prevention Program: perspectives of women and clinicians within a health system. Women's Health Rep. (2021) 2:133–41. doi: 10.1089/whr.2020.0102

13. Stokes, J, Gellatly, J, Bower, P, Meacock, R, Cotterill, S, Sutton, M, et al. Implementing a national diabetes prevention programme in England: lessons learned. BMC Health Serv Res. (2019) 19:991. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4809-3

14. Fernandez, ME, ten Hoor, GA, van Lieshout, S, Rodriguez, SA, Beidas, RS, Parcel, G, et al. Implementation mapping: using intervention mapping to develop implementation strategies. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:158. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00158

15. Leeman, J, Birken, SA, Powell, BJ, Rohweder, C, and Shea, CM. Beyond “implementation strategies”: classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and practice. Implement Sci. (2017) 12:125. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0657-x

16. Proctor, EK, Powell, BJ, and McMillen, JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:139. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139

17. Chambers, DA, Vinson, CA, and Norton, WE. Advancing the science of implementation across the cancer continuum. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2018).

18. Rural Health Information Hub . Rural health clinics (RHCs). Rural Health Information Hub Web site. (2021). Available at: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/rural-health-clinics (Accessed March 2, 2023).

19. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) . Health center program award recipients. (2022). Available at: https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/eligibility-and-registration/health-centers/fqhc (Accessed March 2, 2023).

20. Bandura, A . Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol. (1989) 44:1175–84. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

21. Wandersman, A, Duffy, J, Flaspohler, P, Noonan, R, Lubell, K, Stillman, L, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: the interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. Am J Community Psychol. (2008) 41:171–81. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z

22. Fernandez, ME, Walker, TJ, Weiner, BJ, Calo, WA, Liang, S, Risendal, B, et al. Developing measures to assess constructs from the inner setting domain of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implement Sci. (2018) 13:52. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0736-7

23. Vos, T, Allen, C, Arora, M, Barber, RM, Bhutta, ZA, Brown, A, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. (2016) 388:1545–602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6

Keywords: underserved, implementation mapping, diabetes, prevention, primary care, prediabetes

Citation: Perkison WB, Rodriguez SA, Velasco-Huerta F, Mathews PD, Pulicken C, Beg SS, Heredia NI, Fwelo P, White GE, Reininger BM, McWhorter JW, Chenier R and Fernandez ME (2023) Application of implementation mapping to develop strategies for integrating the National Diabetes Prevention Program into primary care clinics. Front. Public Health. 11:933253. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.933253

Edited by:

Zephanie Tyack, Queensland University of Technology, AustraliaReviewed by:

Aleksandra Gilis-Januszewska, Jagiellonian University Medical College, PolandMechelle Sanders, University of Rochester, United States

Copyright © 2023 Perkison, Rodriguez, Mathews, Velasco-Huerta, Pulicken, Beg, Heredia, Fwelo, White, Reininger, McWhorter, Chenier and Fernandez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: William B. Perkison, V2lsbGlhbS5CLlBlcmtpc29uQHV0aC50bWMuZWR1; Serena A. Rodriguez, U2VyZW5hLkEuUm9kcmlndWV6QHV0aC50bWMuZWR1

William B. Perkison

William B. Perkison Serena A. Rodriguez

Serena A. Rodriguez Fernanda Velasco-Huerta

Fernanda Velasco-Huerta Patenne D. Mathews

Patenne D. Mathews Catherine Pulicken

Catherine Pulicken Sidra S. Beg

Sidra S. Beg Natalia I. Heredia

Natalia I. Heredia Pierre Fwelo

Pierre Fwelo Grace E. White

Grace E. White Belinda M. Reininger

Belinda M. Reininger John W. McWhorter

John W. McWhorter Roshanda Chenier

Roshanda Chenier Maria E. Fernandez

Maria E. Fernandez