95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 31 October 2023

Sec. Life-Course Epidemiology and Social Inequalities in Health

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1285419

This article is part of the Research Topic Towards 2030: Sustainable Development Goal 3: Good Health and Wellbeing. A Sociological Perspective View all 10 articles

Dede K. Teteh1,2†

Dede K. Teteh1,2† Betty Ferrell2

Betty Ferrell2 Oluwatimilehin Okunowo3

Oluwatimilehin Okunowo3 Aidea Downie4

Aidea Downie4 Loretta Erhunmwunsee5

Loretta Erhunmwunsee5 Susanne B. Montgomery6

Susanne B. Montgomery6 Dan Raz5

Dan Raz5 Rick Kittles7

Rick Kittles7 Jae Y. Kim5†

Jae Y. Kim5† Virginia Sun2,5*†

Virginia Sun2,5*†Introduction: Social determinants of health (SDOH) are non-clinical factors that may affect the outcomes of cancer patients. The purpose of this study was to describe the influence of SDOH factors on quality of life (QOL)-related outcomes for lung cancer surgery patients.

Methods: Thirteen patients enrolled in a randomized trial of a dyadic self-management intervention were invited and agreed to participate in semi-structured key informant interviews at study completion (3 months post-discharge). A conventional content analysis approach was used to identify codes and themes that were derived from the interviews. Independent investigators coded the qualitative data, which were subsequently confirmed by a second group of independent investigators. Themes were finalized, and discrepancies were reviewed and resolved.

Results: Six themes, each with several subthemes, emerged. Overall, most participants were knowledgeable about the concept of SDOH and perceived that provider awareness of SDOH information was important for the delivery of comprehensive care in surgery. Some participants described financial challenges during treatment that were exacerbated by their cancer diagnosis and resulted in stress and poor QOL. The perceived impact of education varied and included its importance in navigating the healthcare system, decision-making on health behaviors, and more economic mobility opportunities. Some participants experienced barriers to accessing healthcare due to insurance coverage, travel burden, and the fear of losing quality insurance coverage due to retirement. Neighborhood and built environment factors such as safety, air quality, access to green space, and other environmental factors were perceived as important to QOL. Social support through families/friends and spiritual/religious communities was perceived as important to postoperative recovery.

Discussion: Among lung cancer surgery patients, SDOH factors can impact QOL and the patient’s survivorship journey. Importantly, SDOH should be assessed routinely to identify patients with unmet needs across the five domains. SDOH-driven interventions are needed to address these unmet needs and to improve the QOL and quality of care for lung cancer surgery patients.

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are factors that contribute to the conditions by which people live, work, age, play, and worship that determine their quality of life (QOL) and mortality (1, 2). SDOH are organized into five broad domains: economic stability, education access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, healthcare access and quality, and social and community context (3). While understudied in oncology research, SDOH factors impact the QOL of patients and their family caregivers (4).

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths. Survival is low due to late diagnosis. Despite the proven effectiveness of screening for early detection, access is not equitably distributed (5). Patients also experience several detrimental health outcomes throughout their survivorship journeys that are compounded by SDOH factors (4). Non-clinical factors such as race/ethnicity, insurance status, education, neighborhood features, and income have been associated with perioperative complications and survival following surgery (6). Patients with private insurance are less likely to have postoperative complications (7) and disparities in postoperative mortality for non-white patients (8) from low median-income communities and lower educational attainment persist (7).

Additionally, patients commonly experience mental health challenges, such as worry about transportation, treatment cost, symptoms and side effects, lack of social support, anxiety about function decline, and impact on work (9, 10). As patients experience a decreased QOL due to the disease and treatment process (11, 12) (e.g., surgery and chemotherapy), social support (13, 14) and spiritual/religious wellness resources (15, 16) have been shown to improve outcomes. The importance of addressing psychosocial support access for patients is critical during their survivorship journey (17–20). Sex assigned at birth, age, and other sociodemographic factors have influenced supportive care needs (17). For instance, female status, poor emotional functioning, and younger age have been associated with increased use of psychosocial support services (19). With respect to QOL, prior research has also noted the importance of the provision of palliative care and end-of-life care support (21–23), including practices such as symptom management, education, and coping mechanisms for patients and family caregivers.

Furthermore, levels of economic stability can impact a patient’s lung cancer diagnosis (24–26), treatment access (27), and QOL (28, 29). Educational attainment may also inform delays in treatment referrals (30) and healthcare access for lung cancer patients (31). Finally, there remain significant challenges in neighborhood and built environment conditions, including occupational and residential exposures related to diagnosis and access to care (32–35). Neighborhood-level characteristics have been used to identify high-risk lung cancer behavioral patterns in Maryland (36). The negative effects of lower socioeconomic status on treatment and survival have also been determined with the effects of segregation and economic deprivation determining receipt of lung cancer surgery in Georgia (37). Thus, an individual’s geographical residence may determine their treatment and survival (36–38). However, the current literature on the impact of SDOH on lung cancer patient outcomes is limited and focused primarily on healthcare access and quality, economic stability, and social and community context domains (4). Research on lung cancer surgery patients is also lacking narratives from this population and warrants additional inquiry (6). Thus, to better understand potential barriers to QOL for lung cancer surgery patients, we explored SDOH-related outcomes across the five established SDOH domains.

This study is a part of a randomized trial of a multimedia self-management intervention for lung cancer surgery patients and family caregivers from a National Cancer Institute designated comprehensive cancer center in Southern California.

Participants enrolled in the parent study were eligible for the qualitative study at 3 months post-discharge and following completion of the parent study. During informed consent of the parent study (before surgery), participants were able to select whether they were willing to be contacted for participation in the qualitative study. The parent study followed participants for up to 3 months post-discharge from surgery. Thus, many participants were in the post-treatment survivorship trajectory or completing additional adjuvant treatments based on the stage of the disease. A nurse interventionist and research assistant from the parent study invited participants who agreed to be contacted for the qualitative study. Patient eligibility criteria included: (a) diagnosis of lung cancer as determined by surgeons; (b) underwent curative intent surgery for lung cancer treatment; (c) a family caregiver (FCG) enrolled in the parent study; (d) age 21 years or older; and (e) able to read, speak, or understand English.

The lead author (DT) conducted the semi-structured key informant interviews (Appendix A) with a co-facilitator (VS). The interview guide was developed in collaboration with co-authors and pilot-tested with patients in the same data collection pool. Questions were developed in three-phases. To introduce the concept of SDOH to participants, Phase 1 included a review of the “A Tale of two Zip Codes” (Two Zip Codes) video (39) followed by three awareness questions. The Two Zip Codes video was developed by the California Endowment to detail the SDOH impact on life expectancy in the United States in the context of racial and economic discrimination. The video highlights these SDOH factors on health by comparing two individuals from affluent and disadvantaged communities. Phase 2 included questions on QOL and survivorship by SDOH domains, and Phase 3 questions were developed to solicit how SDOH information can be incorporated into patients’ survivorship care planning. Interview questions were developed based on previous research findings (4) and subject matter expert recommendations from our research team. The interview guide was revised and refined based on pilot test implementation.

Each interview lasted approximately 60 min and was conducted via Microsoft Teams to minimize travel burden for participants. Instructions on how to operate Teams were provided via email, and an outlook calendar invite was sent to participants before each interview. A nurse interventionist and research assistant also reminded patients via telephone and/or email and reviewed Teams’ instructions with patients before their scheduled interviews.

Demographic and SDOH information was obtained at the baseline of the parent study using the Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PRAPARE) (40). This 21-item instrument measures SDOH domains for patients related to environment, economic stability, and social and emotional health factors. PRAPARE is a standardized patient and social risk assessment tool informed by research on SDOH and aligns with national initiatives (e.g., the Department of Health and Human Services’ Healthy People), federal reporting requirements, and the International Classification of Diseases-10 clinical coding system. Participants provided consent for this study during the parent study onboarding procedures. An institutional review board approved the study protocol and procedures.

The conventional content analysis approach was used to identify themes from patients’ experiences (41). Codes and subsequent themes were derived from participants’ interviews and relevant research, or theory was used to interpret meaning from data. Our research team published a systematic literature review on the impact of SDOH on FCG as well as lung cancer patients which informed our interpretation of the data for this study (4). We used the US Department of Health and Human Services’ SDOH framework which includes five broad domains: economic stability, education access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, healthcare access and quality, and social and community context. The process included four independent coders (DT, VS, JK, and BF) followed by four independent reviewers (DT, VS, JK, and AB) who developed the initial content themes. Two reviewers (DT and VS) reviewed and finalized the themes. Coding and/or theme disagreements were discussed, refined, and resolved. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patients’ demographic characteristics. For continuous variables, median and interquartile range were reported; sample size and proportion were reported for categorical variables.

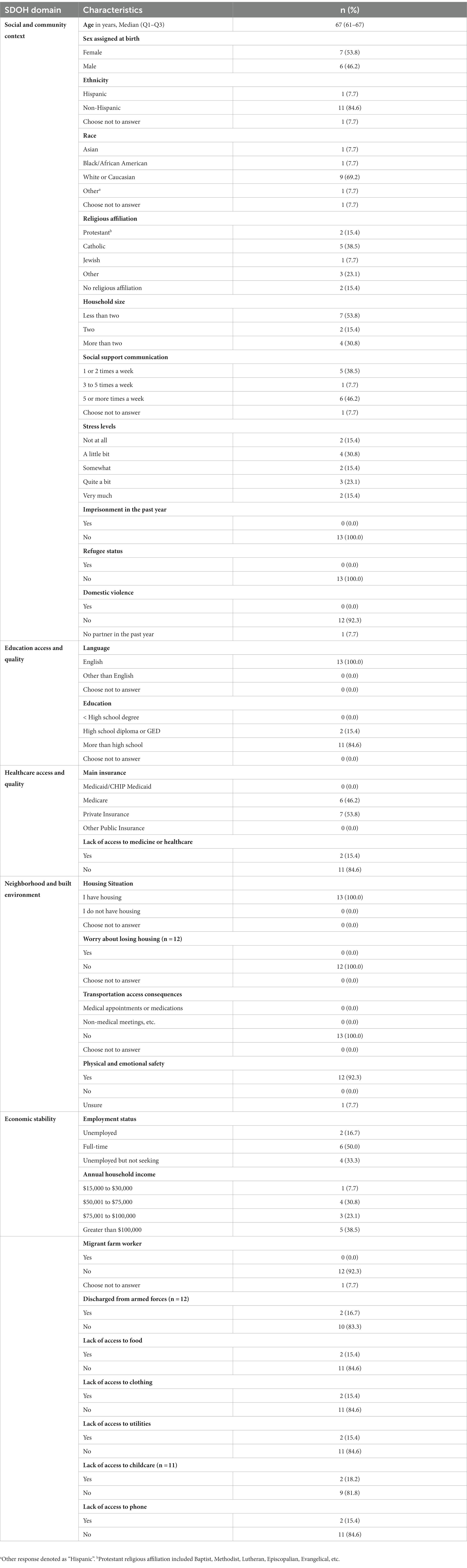

A total of 106 participants of the parent study agreed to be contacted to participate in the qualitative study. Out of this total, we interviewed 13 lung cancer surgery patients for the study and were able to reach saturation with the sample size. Participants were primarily non-Hispanic (85%) and white or Caucasian (69%) with catholic religious affiliation (39%). Most patients (as shown in Table 1) spoke with their social support network five or more times a week (46%). Participants’ stress levels varied before surgery ranging from “very much” (15%) to “a little bit” (31%). English was the primary language spoken by respondents, and most individuals (85%) completed more than a high school education. Patients were either insured through Medicare (46%) or private insurance (54%) and had adequate access to healthcare services. In addition, respondents did not have any housing insecurities, transportation issues, or neighborhood safety challenges. While some patients were unemployed (17%) or retired (33%), most were working full-time (50%) and reported an annual household income greater than $100,000 (39%). Two patients were discharged from the Armed Forces and very few respondents lacked access to food, clothing, utilities, childcare, or a phone in the past year. One respondent did indicate a lack of access to “all utilities” and another participant did not provide additional information about utility needs.

Table 1. Lung cancer surgery patients’ demographic characteristics by social determinants of health (SDOH) domains (N = 13).

Patients were knowledgeable about the concept of SDOH before watching the “Tale of two Zip Codes” video illustration. The video as a result reinforced concepts about the impacts of social and environmental factors on QOL (five subthemes). The discussion of socioeconomic privilege, access to parks, nutrition, healthcare access, and race/ethnicity were highlighted as determinants of positive health outcomes (see Table 2). There was also consensus on the usefulness of providers knowing SDOH factors to tailor the survivorship care plan of surgery patients (two subthemes). SDOH was seen as an implementation of a whole-person care plan that exemplified the attributes of a caring provider. Some considered the need for knowledge about resource availability before and after treatment, healthcare access related to affordability of co-payments and insurance, and a better understanding of the patient’s worldview to tailor health solutions. Patients did not recall discussing the impact of SDOH on their health outcomes with their providers before surgery. Patients also stated that while the information may have been useful, the priority of the provider was to treat their disease.

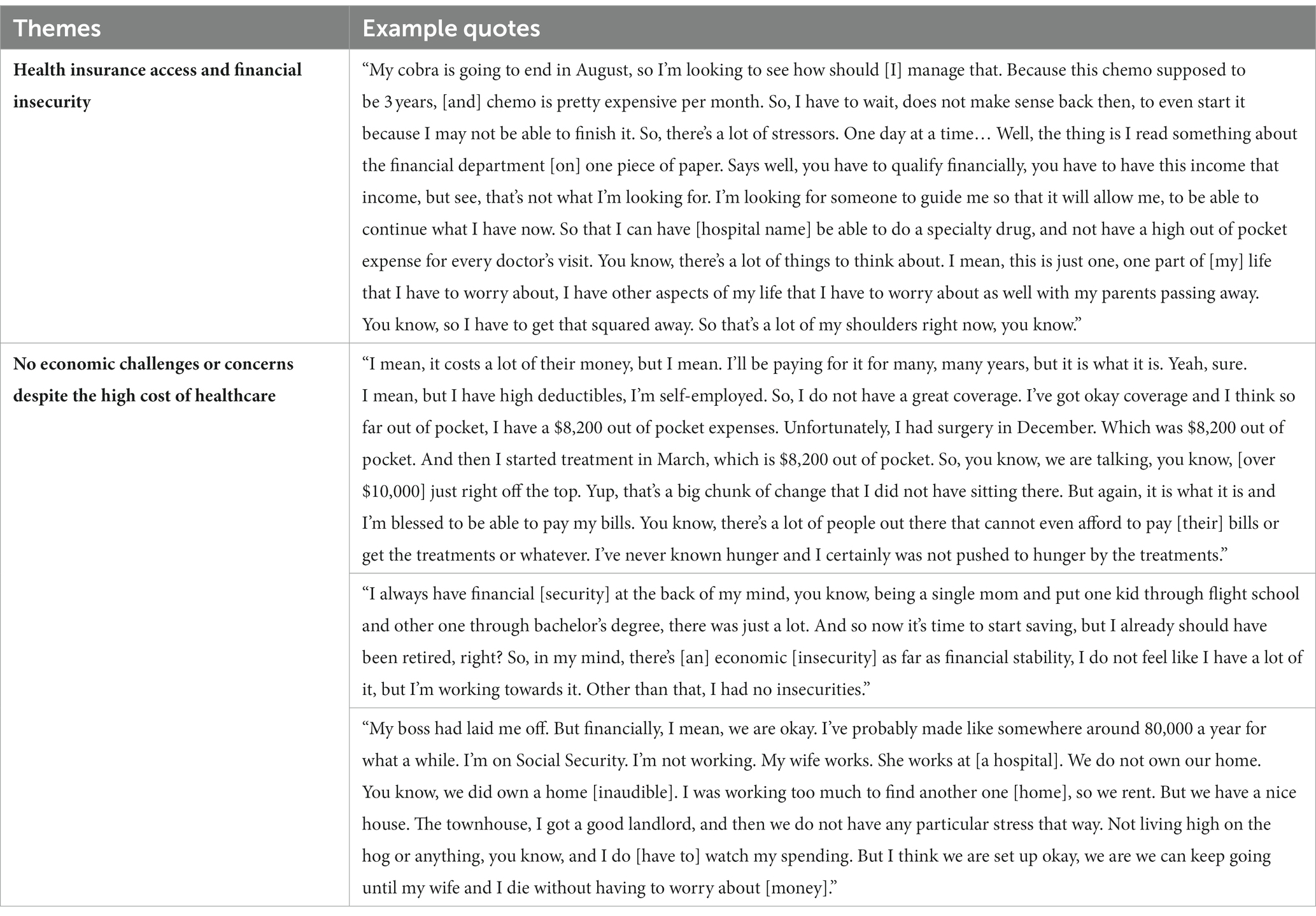

Several patients experienced economic challenges during their treatment resulting in detrimental financial toxicity-related QOL concerns as described in two primary themes (as shown in Table 3). One patient returned to work to have access to health insurance and paid time off during treatment. Another patient’s worries about continuing treatment after the expiration of her Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) insurance benefits were a source of chronic stress. For others, financial insecurity stressors had always been persistent but were now exasperated by a cancer diagnosis, which was the case for a single mom with worries of not having sufficient savings for retirement. Fortunately, some patients did not have economic stability concerns despite high deductibles, and out-of-pocket healthcare costs associated with their treatments.

Table 3. Economic stability challenges and financial toxicity related concerns of lung cancer surgery patients.

Four subthemes described the variable experiences of education on QOL for patients. They included the importance of education for healthcare navigation, lifestyle decision-making strategies for health behavior change, the connection among education, economic mobility opportunities, and better health outcomes, as well as no impact of education on QOL (as shown in Table 4). The benefits of matriculating through an academic degree program were described by participants to include the ability to conduct personal research, comprehension of medical terms or increased health literacy, and decision-making strategies related to the types of questions to ask providers to navigate the healthcare system. There were also benefits for some that propelled lifestyle decision-making strategies or modifications of unhealthy behavior patterns. However, as described by a few participants, the knowledge of a topic does not always result in avoidance of actions such as smoking that have known detrimental health consequences. In addition, participants also briefly discussed the connection between education and economic mobility opportunities that could lead to better health and improved QOL. However, most participants did not agree with the statement “people with higher levels of education live healthier and longer lives.” Their understanding of education extended beyond the mere attainment of an academic degree. Several patients attributed their health literacy to their lived experiences, which in turn resulted in their improved ability to navigate their survivorship journeys and better overall health. They also noted that having a positive and/or inquisitive mindset and professional background (e.g., real estate and claims adjuster) had a positive impact on health outcomes.

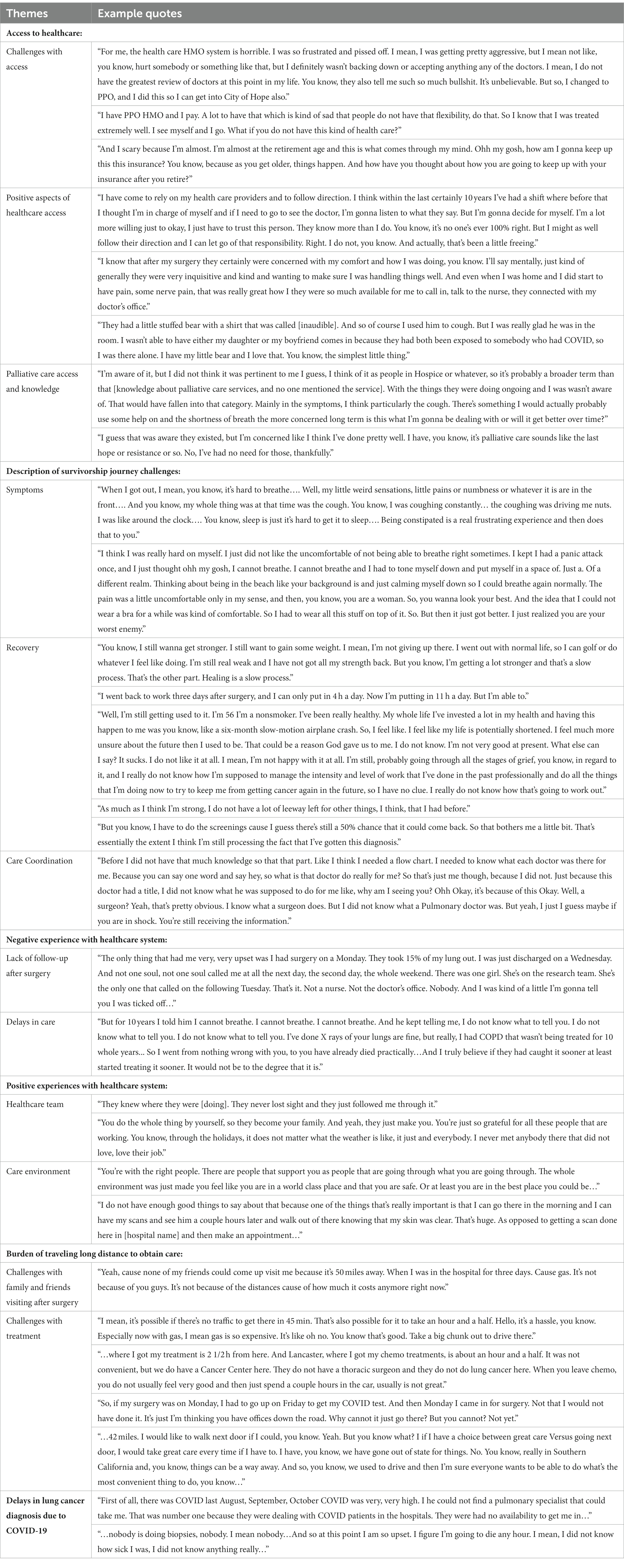

Seven subthemes described participants’ experiences with access and receipt of quality healthcare (see Table 5 for details). Overall, access to healthcare was not a major problem for participants. Positive aspects of healthcare access were common, with overall satisfaction with the quality of care. Proactive postoperative follow-up by the healthcare team on postoperative symptoms and overall wellbeing was viewed as quality care. A quality care environment that promoted clinical excellence, safety, and compassion was important for participants.

Table 5. Access to quality healthcare included insurance status, lack of follow-up after surgery, and COVID-19 challenges.

Others shared examples of challenges in accessing healthcare that were associated with insurance coverage. Despite having insurance coverage, access to quality healthcare was not guaranteed for many participants. Fears and anxiety around insurance coverage as participants faced retirement age were prominent. Negative experiences with the healthcare system included a lack of follow-up after surgery and initial delays in diagnosis. Due to COVID-19, participants described delays with initial diagnosis due to the inability to see specialists and have biopsies. The authors described the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care delivery and QOL for this population in a previous publication (42). Additionally, travel burdens to obtain cancer care and for family/friends to visit were primarily financial, with high gas costs. For participants, long trips after chemotherapy were challenging due to post-infusion toxicities.

Finally, descriptions of survivorship journey challenges were mainly focused on symptoms, recovery, and care coordination. Participants described challenges with dyspnea, prolonged coughing, pain, constipation, and weight loss. They described recovery and healing as a slow process, and frustrations with their inability to participate in activities that they used to enjoy and return to work. On the survivorship journey, participants were still “processing their diagnosis” and “grieving” the reality of being diagnosed. Challenges related to care coordination included not knowing which clinician was responsible for different aspects of their care.

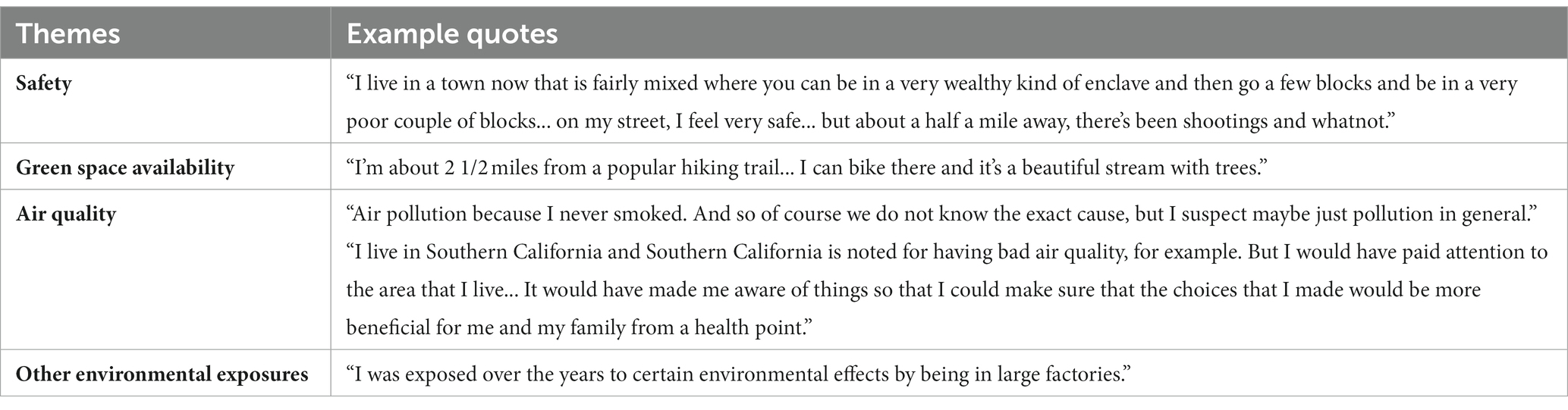

The overarching theme that emerged from the patient interviews was a common understanding of significant disparities in the neighborhood and the built environment, even among those participants who were not negatively affected by these factors. Four sub-themes centered around safety, air quality, access to parks and green space, and other environmental causes of cancer (Table 6).

Table 6. Neighborhood and built environment disparities and health impact variability for lung cancer surgery patients.

Although most participants felt that they lived in relatively safe areas, they acknowledged the stark disparities between safe neighborhoods and unsafe neighborhoods. Some participants noted that safe neighborhoods were sometimes geographically very close to unsafe neighborhoods. All the participants in the study lived in Southern California, so it was unsurprising that air quality was a common issue. Several participants felt that poor air quality contributes to developing lung cancer, particularly among never smokers. Other participants commented that certain parts of Southern California have better air quality—communities close to the beach and some less densely populated areas. Participants noted very tangible air pollution, which they could sense from traffic or recent wildfires. Generally, participants felt more affluent areas have better air quality.

Participants also commonly expressed they had adequate access to parks or other green spaces in the form of hiking trails. Some patients noted that local parks were not well maintained. Others commented that although they had parks in their neighborhood, they seldom used them. Finally, participants raised the issue of other environmental exposures to carcinogens. One participant wondered whether living near a gas station may have affected her health. Others questioned whether prior experiences of living near factories or other industrial complexes may have caused their cancers.

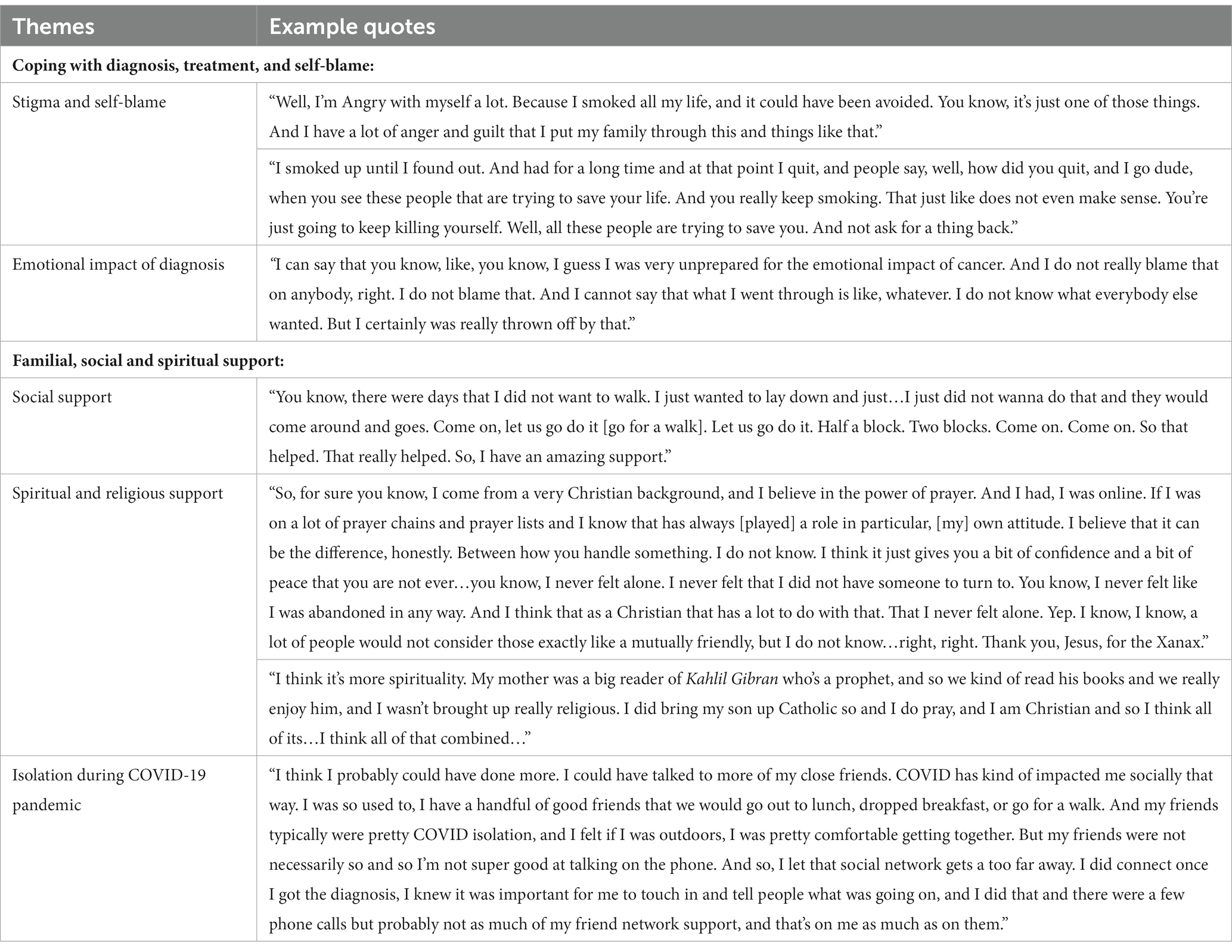

Participants provided perspectives about their emotional, relational, and coping strategies for dealing with the challenges of their survivorship journeys including access to familial, social, spiritual, and religious support systems. As shown in Table 7, two main themes and four subthemes describe the experiences of patients. Overall, patients stressed the importance of having a positive outlook, with one patient noting that a person could be their own worst enemy in this process. Particularly, some patients discussed the stigma and self-blame of being former smokers, the consequences of their past actions that led to their diagnosis, and the burden on their families which weighed heavily on them.

Table 7. Social, interpersonal, coping, and community context perspectives of lung cancer surgery patients.

Patients used varying coping strategies to navigate their diagnosis and treatment journeys. Most patients were unprepared to deal with the emotional and physical ramifications of their diagnosis and treatments which impacted their ability to breathe, work, and socialize, resulting in decreasing their activity levels and minimizing their caregiving responsibilities for other family members. Several patients initially withdrew from their familial and social relationships but eventually found solace in allowing the care and presence of their social network to provide support. Many noted that their familial and social relationships were supportive and encouraged activities beneficial to their recovery that they would not have otherwise been motivated to complete. Participants who were dually patients and caregivers experienced stressors related to caring for children with special healthcare needs and other family members during their recovery. Others discussed feeling isolated or disconnected from relationships in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition, spiritual and religious support was used by patients as a tool for connection, and a way to cope with their mortality using traditional and non-traditional religious formats. Patients’ actions ranged from lighting a candle before prayer, asking God for forgiveness, blessing of good health, going to church on Sunday in person or via Zoom, returning to the practices of Catholicism to receive their last rites, and reading poetic essays from The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran about love, life, religion, and death.

Lung cancer surgery patients experience an array of detrimental factors related to their survivorship journeys that are compounded by SDOH conditions. Despite most participants having health insurance, they experienced several challenges related to financial toxicity, access to quality healthcare, neighborhood and built environment accessibility and exposures, as well as social and interpersonal barriers due to their diagnosis and treatment. They were knowledgeable about the impact of SDOH on their QOL, and the potential effectiveness of including discussions of SDOH in their survivorship care plan. Patients, however, understood that the primary directive of their healthcare team was to treat their disease.

Financial toxicity is one of the most common concerns for patients with cancer including lung cancer (43). Similar to previous studies (44, 45), some of our participants experienced distress related to medical insurance status, out-of-pocket costs, and treatment expenses that negatively affected their QOL. Fortunately, most patients did not have economic stability challenges or financial toxicity concerns. According to Hazell et al., protective factors against financial toxicity for lung cancer patients include older age, white race, employment status, having Medicare insurance, and an annual household income of more than $100,000 (44). Patients in our study were from privileged socioeconomic backgrounds with annual household incomes greater than $100,000 and white, with Medicare or private insurance. For example, one patient spent over $10,000 out of pocket during the initiation of their lung cancer treatment, and another patient was on social security and receiving spousal financial support with no economic stability concerns. Although we lacked representation from minoritized and under-resourced communities who carry a great burden of the disease, it is critical to examine SDOH disparities (46, 47) including financial toxicity concerns and their impact on under-resourced and minoritized lung cancer surgery patients in future studies. Doing so, using mixed methods with the use of validated screening tools such as PRAPARE (40) or the comprehensive score for financial toxicity (48), may better our understanding of the impact of financial toxicity on QOL and survival.

Educational attainment is associated with economic mobility opportunities which influences other SDOH factors such as income, healthcare access, food and housing security, transportation, and neighborhood residence (1, 2). Participants in our study did not discuss challenges related to food, clothing, and utilities. English was the primary language, and most patients had more than a high school education. Education is associated with survival rates of patients with lung cancer (49, 50). Patients of higher education have better survival rates and earlier diagnosis of disease than patients from lower educational attainment (e.g., grade school education). Additionally, the definition of education for patients and its impact on their QOL extended beyond a formal academic degree. An individual’s lived experience provides similar health literacy skills as completing an academic degree. This speaks to the potential limitations of solely relying on questions such as “what is the highest level of school that you have finished?” (40) to determine the impact of education on QOL. While the literature on the positive association between education and longevity is clear (51), determinants of educational attainment for lung cancer surgery outcomes are developing. It is important to include parallel educational experiences in addition to academic degree attainment when determining the impact of these variables on QOL.

Furthermore, SDOH disparities in healthcare impact the quality of lung cancer surgical care, management, and survival of lung cancer patients (52, 53). These healthcare disparities are associated with less use of surgery, more frequent use of more invasive surgical approaches, and lower postoperative survival rates (52). Minoritized groups including Black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Alaskan Native Americans are less likely to receive surgery for early-stage lung cancers even when adjusting for socioeconomic variables (52). As discussed by Bonner and Wakeam (6), there is a “de facto segregation” of lung cancer surgical care where non-white individuals on Medicaid or uninsured are more likely to receive treatment at low-volume hospitals where the quality of care maybe compromised, which consequently may impact the short- and long-term survival and overall QOL of these patients. With an underrepresented sample of these groups in our sample, we lack the data to adequately determine the burden of SDOH factors on healthcare access and quality. However, the burden of access was present in our study from the context of future worries about receiving care due to insurance status (e.g., ending of COBRA). Additionally, as the literature on SDOH disparities in lung cancer surgical care continues to expand, future research designs could benefit from including variations in outcome measures including volume, specific clinical complications, long-term survival, and mortality (6). The evaluation of these outcomes in conjunction with increased inclusion of socioeconomic information may inform disparities-focused interventions that improve access and surgical care delivery for patients.

Participants also acknowledged the relationship between their neighborhood and built environment and health outcomes. Safety, green space, and air quality were determinants of better QOL for participants. Patients also questioned the carcinogenetic effects of environmental pollutants due to proximity to factories, gas stations, and other industrial complexes. Pizzo et al. found significant associations between environmental pollution from a sewage and industrial plant in Italy and increased lung cancer risk for individuals living within 1.5 km (54). Patients residing in lower socioeconomic neighborhoods in Southern California with higher levels of airborne pollutants (e.g., PM2.5 exposure) have an increased probability of having a TP53-mutated lung cancer diagnosis which is associated with poor survival rates (55). Similar findings were shown by Yu and colleagues, with an association between air pollution from the combustion of coal and aggressive tumor biology for Chinese residents (56). In concert with social factors, future research designs should incorporate biological and environmental assessments of patients to better understand the burden of SDOH on QOL.

Moreover, social and community factors can determine patients’ QOL throughout their survivorship journey (4). Factors related to their psychosocial wellbeing, community engagement, and social support availability contribute to their health (1). Participants in our study received social support from their family and friends as well as through their spiritual activities and religious networks. Social support is an important factor for improving QOL for lung cancer patients (57). Particularly, the availability of social support for lung cancer patients is important for symptom management and better psychological and physical QOL (58, 59). For instance, early implementation of an interdisciplinary social support care model had long-term QOL improvements related to psychological distress 12 months after lung cancer surgery (60).

Additionally, the largest religious affiliation of participants from the study was Catholic (38.5%), and few had no religious affiliation. We did not quantitatively assess the spiritual wellbeing of patients but explored their understanding of their religion or spiritual support through interviews. It is important to note descriptions for these terms as their assessments are not synonymous and some patients provided distinctions between their spiritual practices that did not include religious doctrines. Spirituality can be described as the belief in a greater energy or force beyond oneself and the actualization of that belief in connection with self, others, nature, and the sacred (4). Religion includes traditions, rituals, and social practices combined with the belief in an unseen world and a deity which is often represented through doctrines (61). Religion can be an expression of one’s spirituality and is not always dependent on a religious affiliation.

Nevertheless, spiritual support positively impacts perceptions of disease (62) and can be protective against emotional distress for lung cancer survivors (63). Spiritual wellbeing of these studies was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT-Sp-12) which includes measurements of meaning and peace, and the role of faith in illness (64) to understand the protective factors against emotional distress of patients. A religious and spiritual support intervention delivered by chaplains also has demonstrated similar salutary effects on lung and gastrointestinal cancer patients’ QOL (65). Religious support for the intervention was used to measure religious involvement which included three dimensions of religiosity: organizational religious activity, non-organization religious activity, and intrinsic religiosity (66). Spiritual wellbeing was also measured using the FACIT-Sp-12 tool. The critical importance of social support including spiritual and religious support is well-established (57). However, the integration or formal assessments of these support systems for lung cancer surgery patients is not well-known for patients throughout their survivorship journeys. While our patients discussed the importance of these systems for their QOL, their needs were not assessed before their surgery. This begs the question, how do we integrate these SDOH assessments into healthcare practice and provide support when needs are identified? This question is out of the scope of the current study, but an important next step is answering this question for future interventions for this population. Additionally, we recommend that SDOH assessments be considered a fifth vital sign (67) for lung cancer surgery patients and embedded into the standard of care practice and workflow.

The findings should be considered in the context of several strengths and limitations. This study used a mixed methods approach to access barriers to QOL of lung cancer surgery patients from an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center in Southern California. The use of PRAPARE in conjunction with qualitative questions across the five broad SDOH domains provided an informative narrative on SDOH disparities for this population. The use of a multimedia tool “A tale of two Zip Codes” supported the discussion with participants on SDOH. The use of Microsoft Teams is a notable strength as the burden of travel was minimized and allowed the research team to pilot the teleconferencing technology for qualitative data collection. The main limitation of this study is the lack of representation from under-resourced and minoritized communities. However, the sociodemographic background of participants mirrors the catchment area of the cancer center. We also did not address perspectives from family caregivers or clinicians in this study, but these perspectives will be evaluated in future studies as both groups were involved with our data collection efforts.

Lung cancer surgery patients experience several barriers during their survivorship journeys combined with SDOH influences that impact their QOL. Notably, some patients experienced financial toxicity but reported that they received quality healthcare and social support throughout their diagnosis and treatment. Considerations for neighborhood safety and green space were discussed to have salutary impacts on health in addition to explorations about exposures to environmental pollutants due to proximity to industrial complexes. Education was described beyond the attainment of an academic degree and the inclusion of individual lived experiences to support the survivorship journey. SDOH remains an important consideration for QOL and survivorship, but the inclusion of these assessments and the implementation of solutions once needs are identified remain a challenge as the primary objective of the healthcare team is to treat the disease.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

DT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BF: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. OO: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AD: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. LE: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SM: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. DR: Writing – review & editing. RK: Writing – review & editing. JK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research reported in this study is supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number 3R01CA217841-03S1. The statements presented in this article are solely the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors thank the patients who shared their lived experiences with the research team and the members of the parent study Jacqueline Carranza and Rosemary Prieto for their support in recruiting eligible participants for the study, as well as Jovani Barajas, Madeleine Love, and Fernanda Perez for supporting the key informant interviews as note-takers. Fernanda Perez also supported the cleaning of the qualitative data transcripts for the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1285419/full#supplementary-material

1. Asare, M, Flannery, M, and Kamen, C. Social determinants of health: a framework for studying cancer health disparities and minority participation in research. Oncol Nurs Forum. (2017) 44:20. doi: 10.1188/17.ONF.20-23

2. Braveman, P, and Gottlieb, L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. (2014) 129:19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Social determinants of health. (n.d.). Available from: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives#social-determinants-of-health.

4. Teteh, DK, Love, M, Ericson, M, Chan, M, Phillips, T, Toor, A, et al. Social determinants of health among family caregiver centered outcomes in lung cancer: a systematic review. J Thorac Dis. (2023) 15:2824–35. doi: 10.21037/jtd-22-1613

5. Sosa, E, D'Souza, G, Akhtar, A, Sur, M, Love, K, Duffels, J, et al. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in lung cancer screening in the United States: a systematic review. CA Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:299–314. doi: 10.3322/caac.21671

6. Bonner, SN, and Wakeam, E. The volume-outcome relationship in lung cancer surgery: the impact of the social determinants of health care delivery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2022) 163:1933–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.02.104

7. Melvan, JN, Sancheti, MS, Gillespie, T, Nickleach, DC, Liu, Y, Higgins, K, et al. Nonclinical factors associated with 30-day mortality after lung Cancer resection: an analysis of 215,000 patients using the National Cancer Data Base. J Am Coll Surg. (2015) 221:550–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.03.056

8. Lam, MB, Raphael, K, Mehtsun, WT, Phelan, J, Orav, EJ, Jha, AK, et al. Changes in racial disparities in mortality after Cancer surgery in the US, 2007-2016. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2027415. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27415

9. Martin, MY, Fouad, MN, Oster, RA, Schrag, D, Urmie, J, Sanders, S, et al. What do cancer patients worry about when making decisions about treatment? Variation across racial/ethnic groups. Support Care Cancer. (2014) 22:233–44. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1958-5

10. Lyons, KS, Miller, LM, and McCarthy, MJ. The roles of dyadic appraisal and coping in couples with lung Cancer. J Fam Nurs. (2016) 22:493–514. doi: 10.1177/1074840716675976

11. Kyte, K, Ekstedt, M, Rustoen, T, and Oksholm, T. Longing to get back on track: Patients' experiences and supportive care needs after lung cancer surgery. J. Clin. Nurs. (2019) 28:1546–54. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14751

12. Hung, HY, Wu, LM, and Chen, KP. Determinants of quality of life in lung Cancer patients. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2018) 50:257–64. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12376

13. Dogan, N, and Tan, M. Quality of life and social support in patients with lung Cancer. Int J Caring Sci. (2019) 12:263–9.

14. Madani, H, Pourmemari, M, Moghimi, M, and Rashvand, F. Hopelessness, perceived social support and their relationship in Iranian patients with Cancer. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. (2018) 5:314–9. doi: 10.4103/apjon.apjon_5_18

15. Skalla, KA, and Ferrell, B. Challenges in assessing spiritual distress in survivors of Cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. (2015) 19:99–104. doi: 10.1188/15.CJON.99-104

16. Chang, NW, Lin, KC, Hsu, WH, Lee, SC, Chan, JY, and Wang, KY. The effect of gender on health-related quality of life and related factors in post-lobectomy lung-cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2015) 19:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.10.015

17. Rose, P, Quail, H, McPhelim, J, and Simpson, M. Experiences and outcomes of lung cancer patients using electronic assessments. Cancer Nurs. Pract. (2017) 16:26–30. doi: 10.7748/cnp.2017.e1434

18. Lee, CS, and Lyons, KS. Patterns, relevance, and predictors of dyadic mental health over time in lung cancer. Psycho-Oncology. (2019) 28:1721–7. doi: 10.1002/pon.5153

19. Eichler, M, Hechtner, M, Wehler, B, Buhl, R, Stratmann, J, Sebastian, M, et al. Use of psychosocial services by lung cancer survivors in Germany: results of a German multicenter study (LARIS). Strahlenther Onkol. (2019) 195:1018–27. doi: 10.1007/s00066-019-01490-1

20. Shi, Y, Gu, F, and Hou Ll, H. Self-reported depression among patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Thoracic. Cancer. (2015) 6:334–7. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12179

21. Ermers, DJM, KJH, Bussel, Perry, M, Engels, Y, and Schers, HJ, van van Bussel, KJH. Advance care planning for patients with cancer in the palliative phase in Dutch general practices. Fam Pract (2019) 36, 587–593. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmy124

22. Falchook, AD, Dusetzina, SB, Tian, F, Basak, R, Selvam, N, and Chen, RC. Aggressive end-of-life care for metastatic cancer patients younger than age 65 years. JNCI. (2017) 109:1–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx028

23. Temel, JS, Greer, JA, El-Jawahri, A, Pirl, WF, Park, ER, Jackson, VA, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative Care in Patients with Lung and GI Cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. (2017) 35:834–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5046

24. Hovanec, J, Siemiatycki, J, Conway, DI, Olsson, A, Stücker, I, Guida, F, et al. Lung cancer and socioeconomic status in a pooled analysis of case-control studies. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0192999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192999.

25. Nicolau, B, Madathil, SA, Castonguay, G, Rousseau, MC, Parent, ME, and Siemiatycki, J. Shared social mechanisms underlying the risk of nine cancers: a life course study. Int J Cancer. (2019) 144:59–67. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31719

26. Behrens, T, Groß, I, Siemiatycki, J, Conway, DI, Olsson, A, Stücker, I, et al. Occupational prestige, social mobility and the association with lung cancer in men. BMC Cancer. (2016) 16:395. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2432-9

27. Zhou, LF, Zhang, MX, Kong, LQ, Lyman, GH, Wang, K, Lu, W, et al. Costs, trends, and related factors in treating lung Cancer patients in 67 hospitals in Guangxi. China Cancer Invest. (2017) 35:345–57. doi: 10.1080/07357907.2017.1296156

28. Adorno, G, and Wallace, C. Preparation for the end of life and life completion during late-stage lung cancer: an exploratory analysis. Palliat Support Care. (2017) 15:554–64. doi: 10.1017/S1478951516001012

29. Barbaret, C, Delgado-Guay, MO, Sanchez, S, Brosse, C, Ruer, M, Rhondali, W, et al. Inequalities in financial distress, symptoms, and quality of life among patients with advanced Cancer in France and the U.S. Oncologist. (2019) 24:1121–7. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0353

30. Verma, R, Pathmanathan, S, Otty, ZA, Binder, J, Vangaveti, VN, Buttner, P, et al. Delays in lung cancer management pathways between rural and urban patients in North Queensland: a mixed methods study. Intern Med J. (2018) 48:1228–33. doi: 10.1111/imj.13934

31. Billmeier, SE, Ayanian, JZ, He, Y, Jaklitsch, MT, and Rogers, SO. Predictors of nursing home admission, severe functional impairment, or death one year after surgery for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Surg. (2013) 257:555–63. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828353af

32. Torres-Durán, M, Ruano-Ravina, A, Kelsey, KT, Parente-Lamelas, I, Provencio, M, Leiro-Fernández, V, et al. Small cell lung cancer in never-smokers. Eur Respir J. (2016) 47:947–53. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01524-2015

33. Torres-Durán, M, Ruano-Ravina, A, Parente-Lamelas, I, Leiro-Fernández, V, Abal-Arca, J, Montero-Martínez, C, et al. Lung cancer in never-smokers: a case-control study in a radon-prone area (Galicia, Spain). Eur Respir J. (2014) 44:994–1001. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00017114

34. Rodríguez-Martínez, Á, Ruano-Ravina, A, Torres-Durán, M, Vidal-García, I, Leiro-Fernández, V, Hernández-Hernández, J, et al. Small cell lung cance. Methodology and preliminary results of the SMALL CELL study. Arch Bronconeumol. (2017) 53:675–81. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2017.04.016

35. Torres-Durán, M, Ruano-Ravina, A, Parente-Lamelas, I, Leiro-Fernández, V, Abal-Arca, J, Montero-Martínez, C, et al. Residential radon and lung cancer characteristics in never smokers. Int J Radiat Biol. (2015) 91:605–10. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2015.1047985

36. Klassen, AC, Hsieh, S, Pankiewicz, A, Kabbe, A, Hayes, J, and Curriero, F. The association of neighborhood-level social class and tobacco consumption with adverse lung cancer characteristics in Maryland. Tob Induc Dis. (2019) 17:06. doi: 10.18332/tid/100525

37. Johnson, AM, Johnson, A, Hines, RB, and Bayakly, R. The effects of residential segregation and neighborhood characteristics on surgery and survival in patients with early-stage non-small cell lung Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. (2016) 25:750–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-15-1126

38. Erhunmwunsee, L, Wing, SE, Zou, X, Coogan, P, Palmer, JR, and Lennie, WF. Neighborhood disadvantage and lung cancer risk in a national cohort of never smoking black women. Lung Cancer. (2022) 173:21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2022.08.022

39. The California Endownment. A Tale of Two Zip Codes. (2016). Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eu7d0BMRt0o (Accessed July 11, 2023)

40. The National Association of Community Health Centers. Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients' Assets, Risks, and Experiences. (n.d.). Available at: http://www.nachc.org/research-and-data/prapare/

41. Hsieh, H-F, and Shannon, SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

42. Teteh, DK, Barajas, J, Ferrell, B, Zhou, Z, Erhunmwunsee, L, Raz, DJ, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care delivery and quality of life in lung cancer surgery. J Surg Oncol. (2022) 126:407–16. doi: 10.1002/jso.26902

43. Fu, L, Zhuang, M, Luo, C, Zhu, R, Wu, B, Xu, W, et al. Financial toxicity in patients with lung cancer: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e057801. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057801

44. Hazell, SZ, Fu, W, Hu, C, Voong, KR, Lee, B, Peterson, V, et al. Financial toxicity in lung cancer: an assessment of magnitude, perception, and impact on quality of life. Ann Oncol. (2020) 31:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.006

45. Friedes, C, Hazell, SZ, Fu, W, Hu, C, Voong, RK, Lee, B, et al. Longitudinal trends of financial toxicity in patients with lung Cancer: a prospective cohort study. JCO Oncol. Pract. (2021) 17:e1094–109. doi: 10.1200/op.20.00721

46. Mitchell, E, Alese, OB, Yates, C, Rivers, BM, Blackstock, W, Newman, L, et al. Cancer healthcare disparities among African Americans in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. (2022) 114:236–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2022.01.004

47. Ashing, KT, Jones, V, Bedell, F, Phillips, T, and Erhunmwunsee, L. Calling attention to the role of race-driven societal determinants of health on aggressive tumor biology: a focus on black Americans. JCO Oncol Pract. (2022) 18:15–22. doi: 10.1200/op.21.00297

48. Boulanger, M, Mitchell, C, Zhong, J, and Hsu, M. Financial toxicity in lung cancer. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:1004102. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1004102

49. Zhou, K, Shi, H, Chen, R, Cochuyt, JJ, Hodge, DO, Manochakian, R, et al. Association of Race, socioeconomic factors, and treatment characteristics with overall survival in patients with limited-stage small cell lung Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e2032276–6. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.32276

50. Herndon, JE, Kornblith, AB, Holland, JC, and Paskett, ED. Patient education level as a predictor of survival in lung cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. (2008) 26:4116–23. doi: 10.1200/jco.2008.16.7460

51. Roy, B, Kiefe, CI, Jacobs, DR, Goff, DC, Lloyd-Jones, D, Shikany, JM, et al. Education, race/ethnicity, and causes of premature mortality among middle-aged adults in 4 US urban communities: results from CARDIA, 1985–2017. Am J Public Health. (2020) 110:530–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2019.305506

52. Namburi, N, Timsina, L, Ninad, N, Ceppa, D, and Birdas, T. The impact of social determinants of health on management of stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Surg. (2022) 223:1063–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.10.022

53. Farjah, F, Grau-Sepulveda, MV, Gaissert, H, Block, M, Grogan, E, Brown, LM, et al. Volume pledge is not associated with better short-term outcomes after lung cancer resection. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:3518–27. doi: 10.1200/jco.20.00329

54. Pizzo, AM, Chellini, E, and Costantini, AS. Lung cancer risk and residence in the neighborhood of a sewage plant in Italy. A case-control study. Tumori. (2011) 97:9–13. doi: 10.1177/030089161109700102

55. Erhunmwunsee, L, Wing, SE, Shen, J, Hu, H, Sosa, E, Lopez, LN, et al. The association between polluted neighborhoods and TP53-mutated non-small cell lung Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. (2021) 30:1498–505. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-20-1555

56. Yu, XJ, Yang, MJ, Zhou, B, Wang, GZ, Huang, YC, Wu, LC, et al. Characterization of somatic mutations in air pollution-related lung Cancer. EBioMedicine. (2015) 2:583–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.04.003

57. Hofman, A, Zajdel, N, Klekowski, J, and Chabowski, M. Improving social support to increase QoL in lung Cancer patients. Cancer Manag Res. (2021) 13:2319–27. doi: 10.2147/cmar.S278087

58. Gu, W, Xu, YM, and Zhong, BL. Health-related quality of life in Chinese inpatients with lung cancer treated in large general hospitals: across-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2018) 8:e019873. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019873

59. Huang, ZP, Cheng, HL, Loh, SY, and Cheng, KKF. Functional status, supportive care needs, and health-related quality of life in advanced lung Cancer patients aged 50 and older. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. (2020) 7:151–60. doi: 10.4103/apjon.apjon_50_19

60. Raz, DJ, Sun, V, Kim, JY, Williams, AC, Koczywas, M, Cristea, M, et al. Long-term effect of an interdisciplinary supportive care intervention for lung cancer survivors after surgical procedures. Ann Thorac Surg. (2016) 101:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.031

61. McKim, DK. The Westminster dictionary of theological terms: Revised and expanded. Germantown, TN: Westminster John Knox Press (2014) ISBN: 0664238351.

62. Kahraman, BN, and Pehlivan, S. The effect of spiritual well-being on illness perception of lung cancer patıents. Support Care Cancer. (2023) 31:107. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-07527-z

63. Gudenkauf, LM, Clark, MM, Novotny, PJ, Piderman, KM, Ehlers, SL, Patten, CA, et al. Spirituality and emotional distress among lung cancer survivors. Clin Lung Cancer. (2019) 20:e661–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2019.06.015

64. Peterman, AH, Fitchett, G, Brady, MJ, Hernandez, L, and Cella, D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med. (2002) 24:49–58. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06

65. Perez, SEV, Maiko, S, Burke, ES, Slaven, JE, Johns, SA, Smith, OJ, et al. Spiritual care assessment and intervention (SCAI) for adult outpatients with advanced cancer and caregivers: a pilot trial to assess feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects. Am. J. Hospice Palliative Med. (2022) 39:895–906. doi: 10.1177/10499091211042860

66. Koenig, HG, and Büssing, A. The Duke University religion index (DUREL): a five-item measure for use in epidemological studies. Religions. (2010) 1:78–85. doi: 10.3390/rel1010078

Keywords: cancer, community support, lung cancer surgery, patients, oncology, quality of life, social determinants of health, structural determinants of health

Citation: Teteh DK, Ferrell B, Okunowo O, Downie A, Erhunmwunsee L, Montgomery SB, Raz D, Kittles R, Kim JY and Sun V (2023) Social determinants of health and lung cancer surgery: a qualitative study. Front. Public Health. 11:1285419. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1285419

Received: 29 August 2023; Accepted: 05 October 2023;

Published: 31 October 2023.

Edited by:

Andrzej Klimczuk, Warsaw School of Economics, PolandReviewed by:

Soo-Dam Kim, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KIOM), Republic of KoreaCopyright © 2023 Teteh, Ferrell, Okunowo, Downie, Erhunmwunsee, Montgomery, Raz, Kittles, Kim and Sun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Virginia Sun, dnN1bkBjb2gub3Jn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.