94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 30 October 2023

Sec. Aging and Public Health

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1264088

This article is part of the Research Topic Community Series in Mental Illness, Culture, and Society: Dealing with the COVID-19 Pandemic, volume VIII View all 63 articles

Introduction: Engaging in social activities is an essential component of a healthy lifestyle for community-dwelling older adults. Critically, as with past disasters, there is concern about the effects of long-term activity restrictions due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on health of older adults. However, the precise associations between fear of COVID-19, lifestyle satisfaction, leisure activities, and psychological distress are unclear.

Objective: The purpose of this study was to comprehensively determine the associations between fear of COVID-19, lifestyle satisfaction, leisure engagement, and psychological distress among community-dwelling older adults in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods: A questionnaire survey administered by mail was conducted from October 1 to October 15, 2021. The questionnaire included the Fear of COVID-19 Scale, the Lifestyle Satisfaction Scale, the Leisure Activity Scale for Contemporary Older Adults, and the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale-6. Based on previous studies, we developed a hypothetical model for the association between fear of COVID-19, lifestyle satisfaction, leisure engagement, and psychological distress and performed structural equation modeling to assess the relationships between these variables.

Results: Participants included 301 Japanese citizens (23.6% male, 76.4% female), with a mean age of 76.7 ± 4.58 years. Goodness-of-fit from structural equation modeling was generally good. Analysis of standardized coefficients revealed a significant positive relationship between fear of COVID-19 and psychological distress (β = 0.33, p < 0.001) and lifestyle satisfaction and leisure activities (β = 0.35, p < 0.001). We further observed a significant negative relationship between fear of COVID-19 and lifestyle satisfaction (β = −0.23, p < 0.001) and between leisure activities and psychological distress (β = −0.33, p < 0.001).

Conclusion: Fear of COVID-19 is significantly associated with psychological distress, both directly and via its effects on lifestyle satisfaction and leisure activities. That is, not only did fear of COVID-19 directly impact psychological distress of participants, it also affected psychological distress through lifestyle disruption and leisure restriction. This results may be used to better understand how a national emergency that substantially restricts daily life, such as COVID-19 or an earthquake disaster, can affect the psychological health and wellbeing of older, community-dwelling adults.

Japan is one of the most rapidly aging societies in the world, with a life expectancy at birth of 81.5 years for Japanese men and 86.9 years for women in 2019. In contrast, healthy life expectancy at birth is only 72.6 years for men and 75.5 years for women (1), approximately 9 years shorter than average life expectancy for men and 11 years shorter for women. Given that healthy life expectancy refers to the period during which a person can live a healthy life without any hindrance in daily living, there is growing emphasis on extending this period to improve quality of life for older individuals.

Studies have shown that for older adults dwelling in communities, having a sense of Ikigai (i.e., purpose that gives life meaning) through leisure activities is important for leading a healthy life (2, 3). In particular, the health hazards associated with restricted social activities have been clearly demonstrated after past disasters, such as the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011 (4–6). Accordingly, there is substantial concern about the effects of long-term activity restrictions on health of older adults during the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

COVID-19 was first reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and has since spread across the globe, significantly impacting society at every level (7–9). In Japan, the first case of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection was confirmed on January 15, 2020, after which the disease was rapidly disseminated throughout the country. To slow the spread in infection, the first state of emergency was declared for Tokyo, Saitama, Chiba, Kanagawa, Osaka, Hyogo, and Fukuoka on April 7, 2020. The scope of application subsequently expanded nationwide, and the decree was lifted on May 25 of the same year. However, in response to the ongoing evolution of the pandemic and spread of COVID-19, a total of three states of emergency (April–May 2020, January–March 2021, and April–September 2021) were declared in the following years, depending on the region. Unlike lockdowns in other countries, the state of emergency declaration in Japan is not mandatory but rather is only a request for self-restraint. Even so, the emergency declarations and the COVID-19 pandemic, in general, have had a significant impact on people's lives, forcing them to change their conventional lifestyles, such as by refraining from going out and working from home, and resulting in the closure of educational institutions, restaurants, and stores (10).

To prevent the continued spread of COVID-19, it is important to reduce human contact as much as possible (11, 12). To this end, public health experts have recommended the “new normal,” which includes staying home, keeping physical distance, and avoiding the 3Cs: closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings. Because older adults, in particular, are more susceptible to severe COVID-19 (13), it is critical for these individuals to avoid infection. However, the resulting reduction in interpersonal contact has also decreased opportunities for social and leisure activities that older individuals used to engage in. These changes in daily life, such as limiting or refraining from social activities, can have a significant impact on the physical and mental health of older adults.

Since the early stages of the pandemic, efforts have been aimed at assessing the effects of COVID-19 on mental and physical functions, with several published reports focusing on social activities and mental health of older adults. Studies measuring social activities have noted a decrease in physical activity (14), interpersonal interaction (15), and engagement in leisure activities (16) due to a long period of self-restraint. In parallel, mental health studies have reported increased fear and anxiety about contracting SARS-CoV-2, which is at the core of the problem, as well as secondary effects of depression and anxiety due to restricted activity (17–19). Collectively, these findings reveal that the mental health of older adults in response to COVID-19 is affected by a variety of factors. Therefore, to fully understand the effects of the pandemic on mental health, it is necessary to comprehensively consider not only the fear of COVID-19 but also lifestyle changes, engagement in leisure activities, and other factors. However, to our knowledge, previous studies have only examined each factor separately, focusing primarily on one-to-one interactions, and none has comprehensively examined the causal relationships between fear of COVID-19, lifestyle satisfaction, leisure activities, and psychological distress.

The aim of this study was to determine the association between fear of COVID-19, lifestyle satisfaction, leisure activities, and psychological distress among community-dwelling older adults in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. For this purpose, we developed hypothetical models for each of these variables, in which we hypothesized that the fear of COVID-19 would influence psychological distress. In addition, we expected that fear of COVID-19 would affect the participants' lifestyle satisfaction and leisure activities, such as social roles and routines, and that the inability to engage in prior activities would exacerbate psychological distress. Overall, we anticipate that this study may provide useful information for understanding the impacts on older individuals when social activities are restricted by new infectious disease outbreaks or future major disasters, such as earthquakes.

This study is part of an ongoing cohort study since 2007. A questionnaire survey administered by mail was conducted from October 1 to October 15, 2021. Subsequently, 498 older adults participated in this survey after attending a workshop project sponsored by the Ibaraki Prefecture in Japan. Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous, and participants could withdraw from the study at any time. Approval for this research was obtained from the Research Review and Ethics Committee of the affiliated institution, and protection of personal information and research consent procedures were carried out in accordance with ethical regulations. The purpose and content of the study was explained to the participants in a written form, and they were considered to consent by filling out the survey.

The questionnaire included the Japanese version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S), the Lifestyle Satisfaction Scale, the Leisure Activity Scale for Contemporary Older Adults (LASCO), and the Japanese version of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale-6 (K6). Scale details are outlined in the following section. Demographic information collected included participants' age, gender, marital status, and living situation, as well as self-rated health status (1, very good; 2, good; 3, somewhat poor; 4, poor), outpatient treatment, financial situation, and frequency of going out (less or more than once per week). The 301 participants who responded in person and had no missing variables in their responses were included in this analysis.

The Japanese version of the FCV-19S was used to assess fear of COVID-19 (20). The FCV-19S is a self-administered questionnaire that measures fear of novel coronaviruses and requires responses to seven questions using a five-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all applicable) to 5 (very applicable). Higher scores indicate greater fear of COVID-19. The FCV-19S is used worldwide because it is easy to measure, and its reliability and validity have been verified in Japan (21–23).

This item aimed to investigate lifestyle disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, but an appropriate rating scale could not be found. Therefore, we asked participants to respond to their current lifestyle (i.e., habits, routines, and roles) using a four-point scale, ranging from 1 (not satisfied) to 4 (very satisfied), as described in previous studies (24). Higher scores indicate greater lifestyle satisfaction, and lower scores indicate lifestyle disruption.

This instrument was used to assess engagement in leisure activities (25). The survey consists of 11 items (i.e., Technology Use, Social–Public, Social–Private, Physical, Developmental, Cultural, Travel, Creative, Raising Plants, Intellectual Games, and Competitive Games), and participants were asked to indicate their implementation status using a four-point scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (often). The reliability of this scale has been confirmed for older adults living in urban areas of Japan (25).

We measured psychological distress using the Japanese version of the K6 (26, 27). Participants were asked to respond to six questions using a five-point scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (always). The total score ranges from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating greater distress. This instrument has been used in many studies to screen for mental disorders and psychological distress in population health studies.

All analyses were performed using SPSS28.0 and Amos29.0 software. For each scale, a factor analysis was conducted to examine its structure and structural validity. In this factor analysis, items with factor loadings <0.4 were deleted, and Cronbach's alpha scores were also calculated to check for internal consistency. Correlation coefficients were then calculated to compute descriptive statistics and examine associations between variables. In addition, structural equation modeling was performed based on the hypothetical model created in this study. The following goodness-of-fit indices were used to evaluate the degree of fit: Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) > 0.90, comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.90, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) <0.06 (28). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Demographic information for the study participants is shown in Table 1. Participants include 301 older Japanese adults (23.6% male, 76.4% female) living in the Ibaraki prefecture, with a mean age of 76.7 ± 4.58 years; 76% of participants were married at the time of survey completion, and 82.3% lived with a cohabitant. Although 82.9% of participants had regular outpatient treatment, 87.7% reported their health status as relatively healthy. In addition, 83.6% of participants were financially comfortable, and 95% went out at least once a week. Of all participants, 47.0% lived in urban areas and 39.9% in rural areas.

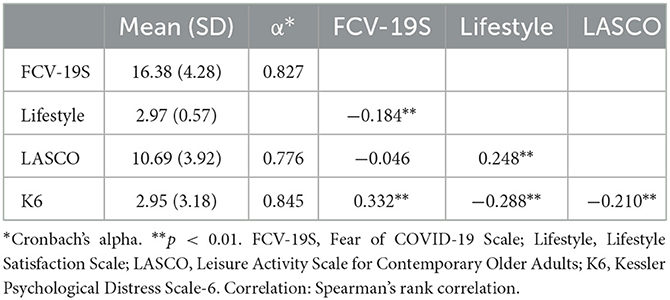

We first conducted an exploratory factor analysis on each scale to examine the factor structure of the scales. For the FCV-19S, one item suspected of multicollinearity was deleted, and six items with one factor were used. Seven items from the LASCO with a factor loading of 0.4 or higher were retained. For the K6, six items with one factor were retained without deleting any item. All Cronbach's alpha scores are shown in Table 2. We then performed correlation analysis with the FCV-19S, Lifestyle Satisfaction Scale, LASCO, and K6; results are presented in Table 2. Correlations were found between all measures except the FCV-19 and LASCO.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and Cronbach's alpha scores for the FCV-19S, lifestyle satisfaction, LASCO, and K6 and correlations between measures.

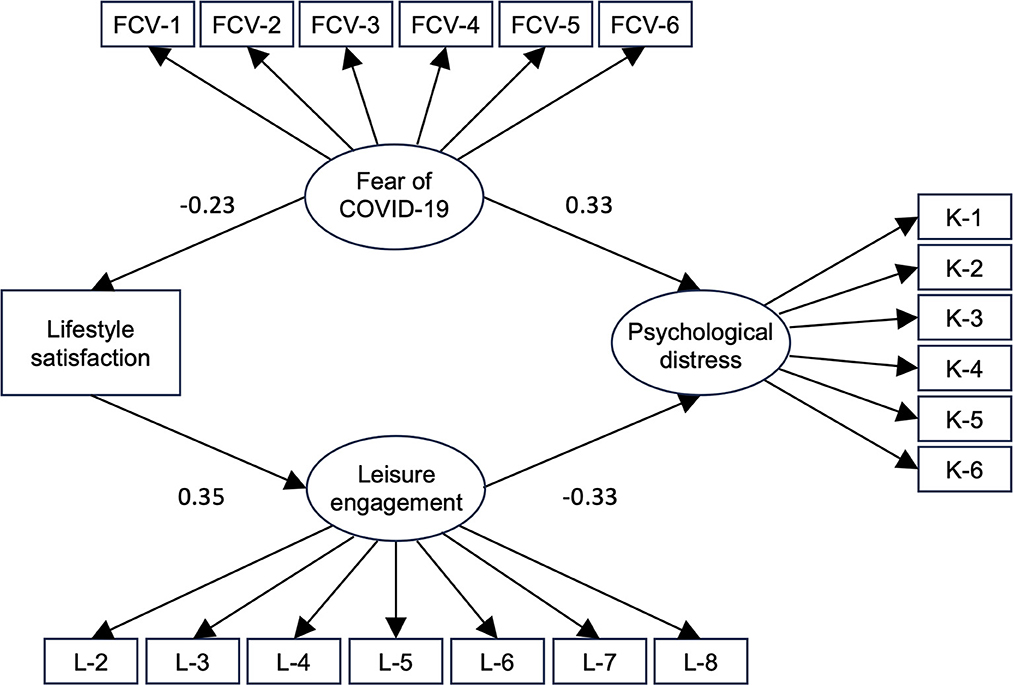

Structural equation modeling was performed to examine the relationships among the variables (Figure 1). Goodness-of-fit indices were as follows: TLI = 0.936, CFI = 0.946, and RMSEA = 0.047, indicating an acceptable level of fit. Standardized coefficients showed a significant positive relationship between fear of COVID-19 and psychological distress (β = 0.33, p < 0.001) and lifestyle satisfaction and leisure activities (β = 0.35, p < 0.001). We further detected a significant negative relationship between fear of COVID-19 and lifestyle satisfaction (β = −0.23, p < 0.001) and between leisure activities and psychological distress (β = −0.33, p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Structural equation modeling results. Standardized coefficients are shown in the figure. Lifestyle satisfaction was measured using the Lifestyle Satisfaction Scale created for this study.

In Japan, “the community-based integrated care system” has been established to enable older adults to live their own way in their own neighborhoods. This model promotes health and care prevention through social participation such as leisure activities (29). Indeed, prior research has reported that taking part in social activities decreases risk of functional impairment, maintains cognitive function, and decreases prevalence of depressive symptoms (30–32). Therefore, it is important for community-dwelling older adults to be encouraged to engage in social activities.

Participants of this study included older adults in a resident-participating long-term care-prevention project. The mean age was 76.7 years, and the majority of participants were older than 75. The male/female ratio was 76.4%, with more females. In general, women are more likely to participate in care-prevention activities in the community, and this group was classified as active, with 95% of participants going out at least once a week. Study participants were gathered from various regions throughout the prefecture and are considered representative of community-dwelling older adults.

We found that fear of COVID-19 had a positive effect on psychological distress; that is, a stronger fear of COVID-19 led to increased psychological distress. Since March 2020, the lives of older adults have changed drastically relative to before the COVID-19 pandemic (33), resulting in various psychological problems. For example, fear and anxiety about contracting COVID-19 can have a significant impact on the mental health of older adults (34–36). Previous studies have similarly reported that fear of COVID-19 affects mental health. We note that our study was conducted in October 2021, approximately 1.5 years after the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, it is clear that fear of COVID-19 has a long-term impact on psychological distress. Another published study noted short-term effects on psychological wellbeing in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as long-term effects due to a prolonged period of self-restraint (37). Thus, our findings are similar to those reported in previous studies and support our hypothesis that fear of COVID-19 affects psychological distress.

Because of their vulnerability and susceptibility to severe illness due to SARS-CoV-2 infection, older individuals have been asked to refrain from or limit their activities. Although these restrictions serve as important infection-prevention measures, prolonged self-restraints result in lifestyle changes and reduce opportunities for leisure and social activities. This new normal to prevent viral infection has had profound social, psychological, and physical effects. In particular, the negative impact of restricted leisure activities on mental health has been noted in several published studies (16, 38). Given that leisure activities are important for maintaining lifestyle satisfaction and good physical and mental health in older adults (39), there are also concerns about prolonged self-restraint leading to increased frailty, a condition referred to as Corona-Frailty (40). These observations highlight the need to comprehensively relationships among these factors in older adults.

This study is novel in that it revealed a comprehensive association between variables, rather than the one-to-one associations previously examined. Notably, we found that fear of COVID-19 affected psychological distress through effects on lifestyle satisfaction and engagement in leisure activities. Thus, these results suggest that fear of COVID-19 increases psychological distress by disrupting lifestyle and restricting engagement in leisure activities. Previous studies have noted a one-to-one association between fear of COVID-19 and psychological distress (35) and between engagement in leisure activities and mental health (16). However, a comprehensive association between fear of COVID-19 and psychological distress via lifestyle satisfaction and engagement in leisure activities is a new finding.

Restrictions associated with the new normal are required to reduce transmission during an infectious pandemic, such as COVID-19. However, given the ongoing nature of the pandemic, social activities for older adults have been restricted for a long period of time, and it has been difficult for these individuals to establish a new normal. Previous studies have reported many limitations for older adults in the wake of COVID-19, including those affecting leisure and social activities and interpersonal interactions (41–43). Results from this study suggest that failure to establish a new lifestyle that includes social and leisure activities will adversely affect the mental health of older individuals. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, it was known that social and leisure activities are important for healthy living among older adults (30). Our results are consistent with these findings and suggest that safe social activities are important to prevent deterioration of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The results of this study suggest that improving lifestyle satisfaction and engagement in leisure activities may prevent psychological distress among older adults. Thus, for those who have a strong fear of COVID-19, it is likely that psychological distress could be improved by providing support increase lifestyle satisfaction and enable engagement in safe leisure activities. Since 2020, the spread of SARS-CoV-2 has necessitated self-restraint and limitations in social interactions to prevent infection, and as a result, the lives of older adults have changed drastically. In response, there is increasing concern about the decline in physical and mental functions of older adults, with various reports describing Corona-Frailty (44–46) and a separate report claiming that fear of COVID-19 increases the risk of frailty in older adults (47).

Regardless of social circumstances, engaging in leisure and other activities has always been important for the health of older adults. Moreover, it is important for one's health to have a good living environment and to engage in leisure activities of one's choice. Thus, our findings indicate that following national emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, efforts to promote lifestyle restructuring and engagement in leisure activities are needed to maintain mental and physical health among community-dwelling older adults.

We understand that this study has several limitations. First, our data are from a cross-sectional analysis conducted at a single point in time. Thus, without longitudinal data, we are unable to examine causal relationships over time. Second, the subjects were participants in a resident-participating long-term care-prevention project and are considered to be a group with high health consciousness and good physical and mental functions compared to their peers. Third, we assumed they are all Japanese based on their name, but ethnicity data was not included in the survey which may limit our implications. Lastly, the majority of participants were female. As gender differences in social and leisure activities have been reported, additional research is needed to investigate the effects of gender on the observed relationships.

We conducted a mailed questionnaire survey of community-dwelling older adults to investigate the relationship between fear of COVID-19, lifestyle satisfaction, leisure engagement, and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that not only did fear of COVID-19 directly affect psychological distress, it also indirectly impacted psychological distress through lifestyle disruption and leisure restriction. These findings suggest it is necessary to focus on lifestyle and leisure engagement in order for older adults living in community settings to continue experiencing good mental and physical health, particularly following a national emergency, such as COVID-19 or an earthquake disaster, which can greatly restrict daily life. However lifestyle and leisure varies among different gender and personal preferences, and further study is necessary to provide tailored support for older adults.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee of Kitasato University School of Allied Health Sciences. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

YZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. AK: Investigation, Validation, Writing—review & editing. TI: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI; Grant Number JP18K10704).

We would like to thank the study participants for their cooperation in the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. World Health Organization. Life Expectancy and Healthy Life Expectancy. Global Health Observatory data repository. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.688?lang=en (accessed July 10, 2023).

2. Okuzono SS, Shiba K, Kim ES, Shirai K, Kondo N, Fujiwara T, et al. Ikigai and subsequent health and wellbeing among japanese older adults: longitudinal outcome-wide analysis. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. (2022) 21:100391. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100391

3. Sasaki R, Hirano M. Development of a scale for assessing the meaning of participation in care prevention group activities provided by local governments in Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:4499. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124499

4. Ito K, Tomata Y, Kogure M, Sugawara Y, Watanabe T, Asaka T, et al. Housing type after the great east japan earthquake and loss of motor function in elderly victims: a prospective observational study. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e012760. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012760

5. Tomata Y, Suzuki Y, Kawado M, Yamada H, Murakami Y, Mieno MN, et al. Long-term impact of the 2011 great east japan earthquake and tsunami on functional disability among older people: a 3-year longitudinal comparison of disability prevalence among japanese municipalities. Soc Sci Med. (2015) 147:296–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.016

6. Yokoyama Y, Otsuka K, Kawakami N, Kobayashi S, Ogawa A, Tannno K, et al. Mental health and related factors after the great east Japan earthquake and Tsunami. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e102497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102497

7. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. (2020) 395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

8. Cerami C, Canevelli M, Santi GC, Galandra C, Dodich A, Cappa SF, et al. Identifying frail populations for disease risk prediction and intervention planning in the COVID-19 era: a focus on social isolation and vulnerability. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:626682. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.626682

9. Babicki M, Kowalski K, Bogudzinska B, Mastalerz-Migas A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental well-being. A nationwide online survey covering three pandemic waves in Poland. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:804123. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.804123

10. Chiba A. The effectiveness of mobility control, shortening of restaurants' opening hours, and working from home on control of COVID-19 spread in Japan. Health Place. (2021) 70:102622. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102622

11. Flaxman S, Mishra S, Gandy A, Unwin HJT, Mellan TA, Coupland H, et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature. (2020) 584:257–61. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2405-7

12. Bo Y, Guo C, Lin C, Zeng Y, Li HB, Zhang Y, et al. Effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 transmission in 190 countries from 23 January to 13 April 2020. Int J Infect Dis. (2021) 102:247–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.066

13. Chidambaram V, Tun NL, Haque WZ, Majella MG, Sivakumar RK, Kumar A, et al. Factors associated with disease severity and mortality among patients with covid-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0241541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241541

14. Yamada M, Kimura Y, Ishiyama D, Otobe Y, Suzuki M, Koyama S, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 epidemic on physical activity in community-dwelling older adults in japan: a cross-sectional online survey. J Nutr Health Aging. (2020) 24:948–50. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1501-6

15. Krendl AC, Perry BL. The impact of sheltering in place during the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults' social and mental well-being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2021) 76:e53–e8. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa110

16. Shen X, MacDonald M, Logan SW, Parkinson C, Gorrell L, Hatfield BE. Leisure engagement during COVID-19 and its association with mental health and wellbeing in U.S. adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:1081. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031081

17. Callow DD, Arnold-Nedimala NA, Jordan LS, Pena GS, Won J, Woodard JL, et al. The mental health benefits of physical activity in older adults survive the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2020) 28:1046–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.06.024

18. Carriedo A, Cecchini JA, Fernandez-Rio J, Mendez-Gimenez A. COVID-19, psychological well-being and physical activity levels in older adults during the nationwide lockdown in Spain. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2020) 28:1146–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.007

19. Heid AR, Cartwright F, Wilson-Genderson M, Pruchno R. Challenges experienced by older people during the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Gerontologist. (2021) 61:48–58. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa138

20. Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2022) 20:1537–45. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8

21. Masuyama A, Shinkawa H, Kubo T. Validation and psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the fear of COVID-19 scale among adolescents. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2022) 20:387–97. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00368-z

22. Midorikawa H, Aiba M, Lebowitz A, Taguchi T, Shiratori Y, Ogawa T, et al. Confirming validity of the fear of COVID-19 scale in japanese with a nationwide large-scale sample. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0246840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246840

23. Wakashima K, Asai K, Kobayashi D, Koiwa K, Kamoshida S, Sakuraba M. The Japanese version of the fear of COVID-19 scale: reliability, validity, and relation to coping behavior. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0241958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241958

24. Lee SW, Kielhofner G. Habituation: patterns of daily occupation. In: Kielhofner's Model of Human Occupation (2017). p. 57–73.

25. Iwasa H, Yoshida Y, Ishioka Y, Suzukamo Y. Development of a leisure activity scale for contemporary older adults: examination of its association with cognitive function. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. (2019) 66:617–28. doi: 10.11236/jph.66.10_617

26. Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2003) 60:184–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184

27. Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Slade T, Andrews G. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of mental health and well-being. Psychol Med. (2003) 33:357–62. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006700

28. Hu Lt, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equat. Model. (1999) 6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

29. Ministry Ministry of Health Labour Welfare. Establishing the Community-Based Integrated Care System. Available online at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/ care- welfare/care- welfare- elderly/dl/establish_e.pdf (accessed July 10, 2023).

30. Kanamori S, Kai Y, Aida J, Kondo K, Kawachi I, Hirai H, et al. Social participation and the prevention of functional disability in older Japanese: the jages cohort study. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e99638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099638

31. Hikichi H, Kondo K, Takeda T, Kawachi I. Social interaction and cognitive decline: results of a 7-year community intervention. Alzheimers Dement. (2017) 3:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2016.11.003

32. Du M, Dai W, Liu J, Tao J. Less social participation is associated with a higher risk of depressive symptoms among Chinese older adults: a community-based longitudinal prospective cohort study. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:781771. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.781771

33. Engels C, Segaux L, Canouï-Poitrine F. Occupational disruptions during lockdown, by generation: a european descriptive cross-sectional survey. Br J Occupat Ther. (2021) 85:603–16. doi: 10.1177/03080226211057842

34. Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Pakpour AH. The association between health status and insomnia, mental health, and preventive behaviors: the mediating role of fear of COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med. (2020) 6:2333721420966081. doi: 10.1177/2333721420966081

35. Han MFY, Mahendran R, Yu J. Associations between fear of COVID-19, affective symptoms and risk perception among community-dwelling older adults during a COVID-19 lockdown. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:638831. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.638831

36. Olapegba PO, Chovwen CO, Ayandele O, Ramos-Vera C. Fear of COVID-19 and preventive health behavior: mediating role of post-traumatic stress symptomology and psychological distress. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2021) 20:2922–33. doi: 10.1007/s11469-021-00557-4

37. Moustakopoulou L, Adamakidou T, Plakas S, Drakopoulou M, Apostolara P, Mantoudi A, et al. Exploring loneliness, fear and depression among older adults during the covid-19 era: a cross-sectional study in greek provincial towns. Healthcare. (2023) 11:1234. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11091234

38. Tanikaga M, Uemura JI, Hori F, Hamada T, Tanaka M. Changes in community-dwelling elderly's activity and participation affecting depression during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:4228. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20054228

39. Sajin NB, Dahlan A, Ibrahim SAS. Quality of life and leisure participation amongst malay older people in the institution. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. (2016) 234:83–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.10.222

40. Yamada M, Kimura Y, Ishiyama D, Otobe Y, Suzuki M, Koyama S, et al. The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and new incidence of frailty among initially non-frail older adults in Japan: a follow-up online survey. J Nutr Health Aging. (2021) 25:751–6. doi: 10.1007/s12603-021-1634-2

41. Tomaz SA, Coffee P, Ryde GC, Swales B, Neely KC, Connelly J, et al. Loneliness, wellbeing, and social activity in scottish older adults resulting from social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:4517. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094517

42. Kim EJ, Park SM, Kang HW. Changes in leisure activities of the elderly due to the COVID-19 in Korea. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:966989. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.966989

43. Parlapani E, Holeva V, Nikopoulou VA, Sereslis K, Athanasiadou M, Godosidis A, et al. Intolerance of uncertainty and loneliness in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:842. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00842

44. Braude P, McCarthy K, Strawbridge R, Short R, Verduri A, Vilches-Moraga A, et al. Frailty is associated with poor mental health 1 year after hospitalisation with COVID-19. J Affect Disord. (2022) 310:377–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.05.035

45. Lozupone M, La Montagna M, Di Gioia I, Sardone R, Resta E, Daniele A, et al. Social frailty in the COVID-19 pandemic era. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:577113. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.577113

46. Shinohara T, Saida K, Tanaka S, Murayama A. Actual frailty conditions and lifestyle changes in community-dwelling older adults affected by coronavirus disease 2019 countermeasures in Japan: a cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Nurs. (2021) 7:23779608211025117. doi: 10.1177/23779608211025117

Keywords: leisure activities, psychological distress, lifestyle, COVID-19, healthy aging

Citation: Zenba Y, Kobayashi A and Imai T (2023) Psychological distress is affected by fear of COVID-19 via lifestyle disruption and leisure restriction among older adults in Japan: a cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 11:1264088. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1264088

Received: 20 July 2023; Accepted: 12 October 2023;

Published: 30 October 2023.

Edited by:

Mohammadreza Shalbafan, Iran University of Medical Sciences, IranReviewed by:

Oksana Zayachkivska, Danylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, UkraineCopyright © 2023 Zenba, Kobayashi and Imai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yosuke Zenba, eW96ZW5Aa2l0YXNhdG8tdS5hYy5qcA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.