95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 17 November 2023

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1258798

This article is part of the Research Topic Childhood Traumatic Experiences: New Clinical Perspectives and Interventions View all 10 articles

Introduction: Multiple evidence suggests that the vast majority of children in the Child Welfare System (CWS) are victims of early, chronic, and multiple adverse childhood experiences. However, the 10-item version of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (ACE-10) has never been tested in such a particularly vulnerable population as adolescents living in the CWS. We aimed to assess the psychometric properties of the ACE-10 in a community sample of 240 Hungarian adolescents placed in family style group care (FGC) setting.

Methods: Demographic data, the 10-item version of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (ACE-10), the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), and the HBSC Bullying Measure were used.

Results: Our results showed acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.701) and item-total correlations (rpb = 0.25–0.65, p < 0.001). However, our results also reflect that item 6 (“Parental separation/divorce”) is weakly correlated with both the cumulative ACE score and the rest of the questionnaire items. When item 6 is removed, the 9-item version of the ACE produces more favorable consistency results (α = 0.729). Strong and significant associations of the cumulative ACE score with emotional and behavioral symptoms and bully victimization confirm the concurrent criterion validity of both versions of the instrument.

Discussion: Our findings suggest that ACE-9 and ACE-10 are viable screening tools for adverse childhood experiences in the CWS contributing to the advancement of trauma-informed care. We recommend considering the use of either the 9-item or the 10- item version in the light of the characteristics of the surveyed population. The implications and limitations are discussed.

The social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the broader set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life (1). The social determinants of health represent a broader concept, whereas child maltreatment covers its specific aspect related to the family context. Poverty, unemployment, low socio-economic status and resulting chronic stress, and family structure characteristics (e.g., divorce, household substance use, household mental illness) are risk factors for child maltreatment (2, 3). The ecological model of the etiology of child abuse views maltreatment as a system of interacting risk and protective factors at four levels: the individual or ontogenic level, the family microsystem, the contextual level, and the social macrosystem (4). Accordingly, child maltreatment contributes to maintaining unfavorable social positions.

Child maltreatment (neglect, emotional, physical, sexual abuse) is a major public health issue worldwide. Over the past 20 years, studies were launched to explore child maltreatment on an increasingly broad scale. Some studies attempted to explore the prevalence of different forms of child abuse and neglect (5–10), whereas others focused on exploring their risk factors (2, 3, 11–13) and consequences (14–16). Recent research, however, has started examining a wider range of adverse factors affecting children; therefore, instead of using the term “child maltreatment,” we will use the broader term extended “adverse childhood experiences” (ACEs), which also includes dysfunctional family environments (household dysfunction) in addition to maltreatment (neglect and abuse) (15). Research has confirmed that adverse childhood experiences within the family are strong predictors of mental disorders and somatic outcomes, including chronic diseases (14–16).

Children in child protection are one of the most vulnerable populations, supporting their growth and providing them with psychological/social care is a major challenge worldwide (17). Children who are displaced from their biological families have a much more difficult life path (18). Children in CWS have a high prevalence of various adverse childhood experiences, ranging from 28 to 80% (19–26). The different prevalence results of these studies are influenced by differences in definitions and groupings of adversities/trauma, differences in measurement instruments, as well as age differences in the sample (27).

The conceptual model ACE pyramid represents the life-long consequences of persistent adverse experiences in childhood (28). Early onset, cumulative and prolonged adverse experiences can result in disrupted neurodevelopment, immune and endocrine system modifications (29–31). Attachment difficulties, emotional and behavioral dysregulation result in a lack of appropriate problem-solving (or coping mechanism) strategies, leading some of those exposed to adversity to engage in persistent health-damaging behaviors (28, 32–34). Some of these children suffering from social, emotional and cognitive impairments will develop mental and somatic illnesses over their life course, which leads to disability and/or social impairments later in life (28, 31).

Understanding the prevalence and characteristics of adverse childhood experiences is essential for planning interventions aimed at reducing child maltreatment, this requires easy-to-use, reliable measurement tools (27, 35, 36).

ACEs can be measured through self-assessment questionnaires or expert interviews. The advantage of questionnaires is that they are economical, easy to administer and score, and ensure anonymity, which can reduce the chance of biased responses triggered by shame associated with trauma (35, 37). Self-report by adolescents is still found to be more reliable than agency records, parental reports of adolescent victimization or adult retrospective self-report (37, 38).

Measures used to assess the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences should use consistent concepts about the types of child maltreatment and the same stands for their definitions (39). To avoid underestimation, items in measures should be behavior-specific, not ambiguous or non-specific (40). Ideally, all five forms of child maltreatment (physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction) should be measured simultaneously, as a number of children experience resulting polyvictimization and its increased consequences (16, 41, 42).

In a previous study methods to assess ACEs among children and families were identified and compared (35). Measuring tools commonly used in children and adolescents (without attempting to be comprehensive): Yale-Vermont Adversity in Childhood Scale; Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire; Adverse Childhood Experiences Abuse Short Form (ACE-ASF); Philadelphia Childhood Adversity Questionnaire (CAQ); Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF); Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire (JVQ) (35, 43–45).

The 10-item ACE Score Calculator examines simultaneously all five forms of child maltreatment outlined above, with clear, unambiguous questions that are behavior-specific and concrete. In this way, the questionnaire is also suitable for testing an adolescent population in the child welfare system, so the clarity of the questions allows for the examination of children. To the best of our knowledge, only one study so far has examined the psychometric properties of this questionnaire in a normal adolescents population (46), although it is perfectly suitable for screening a larger population for adverse childhood experiences (as it can be applied simply and quickly).

The aim of our study was to assess the psychometric properties of the 10-item ACE Score Calculator and to demonstrate its reliability and validity in a specific sample of Hungarian adolescents placed in the Child Welfare System. There are no validated tools in Hungary for screening the vulnerable group of children living in CWS. The advances of the ACE-10 questionnaire mentioned above make it suitable for screening children in child welfare system for adverse childhood experiences. Increased attention to screening and assisting this population is needed, not only for the benefit of the population concerned, but also for the society as a whole.

The data collection on adolescents (aged 12˗17) under child protection services was carried out in 31 family-style group care (FGC) settings in 3 counties of Hungary, and was conducted between March 2018 and January 2020. The sampling frame for the CWS sample consisted of 309 mentally sound adolescents living in 31 FGCs. After having been provided oral and written information, the adolescents and their guardians signed the informed consent form to participate in the study. Adolescents filled in the questionnaire anonymously. The questionnaires were filled in during group sessions, where each three adolescents were supervised by one health psychology Msc student, whose help was mainly needed in case of reading or attention difficulties. When emotional, cognitive, or other reasons made it necessary, the questionnaires were completed in individual sessions instead. A total of 271 adolescents completed the questionnaire. The reasons for the missing responses were that some adolescents were not at home on the day of data collection, were runaways, or either the guardians or the adolescents refused to provide consent. After data cleaning (elimination of incompletely filled questionnaires), the final sample size was 240. Ethics approval was issued by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hungarian Medical Research Council under the approval number ETT TUKEB 47848-7/2018/EKU.

The demographic data of the studied adolescents were assessed using a self-developed questionnaire with items asking for information on gender, age, nationality, school type, grade, and residential location. We administered the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (47, 48) and the HBSC (Health Behavior in School-aged Children Questionnaire) Bullying Measure (49, 50) to assess concurrent criterion validity of the ACE Score Calculator. Multiple studies have demonstrated that the social, emotional, and behavioral symptoms and roles in bullying (perpetration/victimization) are significant correlates of the accumulation of childhood adversities (16, 51–55).

ACEs were assessed using 10-item version of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (ACE-10), which is a retrospective self-report questionnaire consisting of 10 items (56). The questions in this survey aim to assess 10 types of early ACEs suffered before the age of 18. These ACEs cover the possible forms of maltreatment (physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, and physical, emotional neglect) and household dysfunction (parental separation/divorce, household physical violence, household substance abuse, household mental illness or suicide attempt, incarcerated household member). Previous research has demonstrated the different and distinct nature of these events through a series of analyses. This is why the questionnaire includes these items (15, 56, 57).

A cumulative ACE score between 0 and 10 is calculated by summing the number of ‘yes’ responses for each question, based on the number of types of ACEs. The ACE score is a severity index that measures the accumulation of different types of adverse experiences, showing how many types of adversities a person has experienced in their childhood. Our previous study confirms that the ACE-10 is suitable for assessing intrafamilial adverse childhood experiences in adolescents (46). The content of the items and the response options are provided in the Supplementary appendix.

For the assessment of social, emotional, and behavioral symptoms the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was employed (47, 48). The items of this questionnaire can be grouped in five factors as follows: hyperactivity, emotional problems, behavioral disorders, peer relationship problems, and prosocial conduct. The Hungarian version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire was adapted and validated by Birkás et al. (58). The questionnaire was found to have acceptable internal consistency in the sample (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.70).

Bullying was assessed using the relevant questions of the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children Questionnaire (HBSC-2014) (49, 50). The HBSC questionnaire is a comprehensive measure of health behaviors administered among school-aged children every 4 years. The HBSC study is based on a standardized methodology and conducted in more than 40 countries in international collaboration with the World Health Organization (59). The HBSC Bullying Measure includes questions on bullying, the role of perpetrators and victims of physical and emotional abuse and cyberbullying, and participants of physical fight. Previous studies have reported good reliability of scales (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76–0.84) (60, 61). First, the phenomenon of bullying was introduced, followed by four questions about bullying (in-person bullying victimization, cyberbullying victimization, bullying perpetration, and physical fight). In all the four categories the answers to choose from were: never/once or twice/2 or 3 times a month/about once a week/ several times a week. After combining the categories of bullying variables, we defined frequency as a binary variable (never vs. at least once in the past 12 months) (61).

Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). The sociodemographic and ACE characteristics, the mean and standard deviation of SEB symptom scores, and the frequency of bullying variables were described in the sample overall and by gender. Psychometric properties of the ACE Score Calculator were investigated through internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha calculation), intercorrelations (Phi correlation), item-total correlations (Point-biserial correlations), and association analyses for concurrent criterion validity. Since the studies conducted during the development and evolution of the test confirmed the distinct nature of the events tested in each item, the dimensionality of the test was not examined (15, 56, 57).

Generalized linear models with entry method were used to test associations of ACE score with SEB symptoms, and logistic regression models with backward (Wald) method for ACE score with bullying variables. All models were adjusted for age, gender, and location, and post-test analysis was carried out with the help of the adjusted Wald test.

The total sample consisted of 240 adolescents [54.17% girls, mean age 14.9 (SD = 1.58)]. 7.5% (n = 17) of them reported no ACE, while 22.4% (n = 51) reported one, 18% (n = 41) reported two, 11.8% (n = 27) reported three and 40.4% (n = 92) reported four or more ACEs.

The most frequent type of reported child maltreatment was emotional abuse in 32.1% (n = 76), and emotional neglect in 30.1% (n = 71) of the sample. The least prevalent reported child maltreatment was sexual abuse in 13.6% (n = 32) of the respondents. Parental divorce or separation was reported by 71.2% of the adolescents (n = 196), which was followed by incarcerated household member 48.5% (n = 114) and household substance abuse (32.5%, n = 76). These three dysfunctions were the most prevalent reported dysfunctional household conditions, while the least prevalent was having experienced household physical violence (21.5%, n = 51) (Table 1).

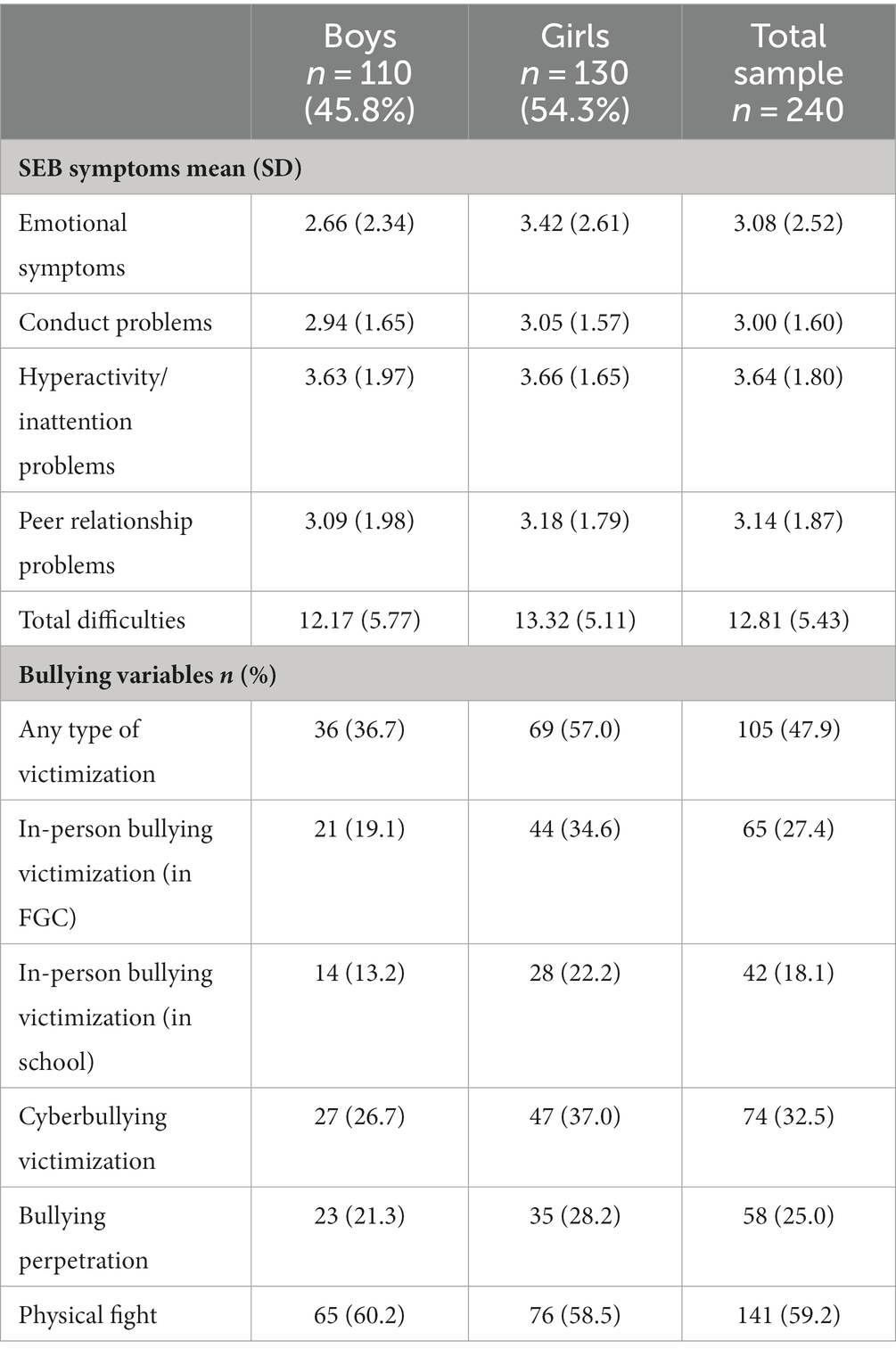

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of SEB symptoms and bullying variables in the sample. The mean scores of SEB symptoms ranged from 3.00 (SD = 1.60) (conduct problems) to 3.64 (SD = 1.80) (hyperactivity/inattention problems), while the mean for the total difficulties score was 12.81 (SD = 5.43).

Table 2. Social, emotional, and behavioral (SEB) symptoms and bullying characteristics of the sample overall and by gender.

In terms of bullying, almost half of the respondents (47.9%, n = 105) reported some type of victimization. The most prevalent form of bullying was physical fight (59.2%, n = 141) and cyberbullying victimization (32.5%, n = 74).

Around one-quarter reported in-person bullying victimization (27.4%, n = 65) and bullying perpetration (25%, n = 58).

The Cronbach’s alpha reliability shows an acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.700).

Intercorrelations of ACEs (Table 3) were used to study the strength of associations between the frequency of occurrence of each adverse event. The item “Parental separation/divorce” barely correlated with the other types of ACEs, and the item “Sexual abuse” only correlated with four of the rest of the adverse events.

Point-biserial correlations were carried out to investigate the item-total correlation of the questionnaire. Table 4 shows that “Parental separation/divorce” was the only item to show weak correlation with the cumulative ACE score. In the case of the rest of the items, at least moderate correlations were found, which suggests the appropriate item-total correlations of the scale. “Physical abuse” exhibited the strongest correlation with the cumulative ACE score.

Reviewing the data on intercorrelations and item-total correlations, the item “Parental separation/divorce” proved to be the least correlating item with the rest of the test items and the cumulative score. Consequently, we decided to examine the concurrent criterion validity of the test when the ACE 6 item (“Parental separation/divorce”) is removed.

Considering the above results, the concurrent criterion validity was tested for both the 10-item and the 9-item version (excluding the item for parental separation/divorce). The comparison yielded similar results in the two versions with equal or somewhat stronger predictive potentials in the 9-item version. We used generalized linear models with entry method to examine the associations between ACE accumulation and SEB symptoms adjusted for age, gender, and location. The cumulative ACE score was significantly associated with more emotional symptoms (ACE-10: B = 0.20, p = 0.005; ACE-9: B = 0.23, p = 0.002), conduct problems (ACE-10: B = 0.15 p = 0.001; ACE-9: B = 0.16; p = 0.001), hyperactivity/inattention symptoms (ACE-10: B = 0.16, p = 0.002; ACE-9: B = 0.18, p = 0.001), and overall difficulties (ACE-10: B = 0.50, p = 0.002; ACE-9: B = 0.57, p = 0.001). Peer relationship problems did not correlate with the cumulative ACE score in the sample (ACE-10: B = 0.05, p = 0.391; ACE-9: B = 0.07; p = 0.255).

Logistic regressions with backward (Wald) method were applied to examine the relationship between ACE and bullying variables. Models were adjusted for age, gender, and location. One point increase in the ACE score significantly increased the possibility of being a victim of any measured type of bullying by 12 and 20% in ACE-10 and ACE-9, respectively (ACE-10: OR = 1.12, p = 0.007; ACE-9: OR = 1.20, p = 0.009). In details, the correlation of ACE score with in-person bullying victimization in FGC was marginally significant in ACE-10 and significant in ACE-9 (ACE-10: OR = 1.14, p = 0.059; ACE-9: OR = 1.15, p = 0.44), while in-person victimization in school was not significant (ACE-10: OR = 1.13, p = 0.115; ACE-9: OR = 1.13, p = 0.139). At the same time, being a victim of cyberbullying was in significant positive relationship with ACE accumulation (ACE-10: OR = 1.17, p = 0.014; ACE-9: OR = 1.17, p = 0.022), which was significantly associated with increased odds of involvement in physical fight (ACE-10: OR = 1.27, p = 0.001; ACE-9: OR = 0.127, p = 0.001). The association between ACE score and bullying perpetration were not significant in the sample, but p-values were nearing the margin (ACE-10: OR = 1.12, p = 0.094; ACE-9: OR = 1.13, p = 0.086).

When calculating the Cronbach’s alpha reliability index of the 9-item version, we found a more favorable value than in the case of the 10-item version (α = 0.729).

In the present study, we conducted the psychometric evaluation of the ACE-10 questionnaire in a sample of Hungarian adolescents in the CWS. We assessed the intercorrelations, item-total correlations, concurrent criterion validity, and reliability of the instrument. The 10-item short form of the original ACE questionnaire comprised questions measuring 5 types of maltreatment (physical, emotional, sexual abuse, physical, and emotional neglect), and 5 types of household dysfunction.

Consistently with our study on average adolescent population (46), the ACE-10 showed appropriate internal consistency and reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70. For internal correlation, we found that sexual abuse is only correlated with dysfunctional family factors (apart from physical neglect). This may be explained by the fact that sexual abuse is the only item that refers not only to harm suffered within the family but also to abuse suffered outside the family (15). The CWS population is an at-risk population, where a severely dysfunctional family system increases the risk of exposure to harm outside the family. Accordingly, we can assume that the “yes” responses for these item do not only refer to events experienced within the family, as opposed to the rest of the items. The item “Parental separation/divorce” is only correlated with the item “incarcerated household member,” and the correlation there is only a weak one. The results found for these two items are not in line with the results of our study on the average population, where both “Sexual abuse” and “Parental separation/divorce” were correlated with the other items of the scale.

The ACE-10 scale assessed in the CWS population showed adequate item-total correlations. However, not all of the ACE-10 items were found to be equally relevant in the Point-biserial analysis. Again, it is the item “Patental separation/divorce” that barely correlated with the ACE cumulative score. This result differs from our study on the average sample, where this item showed a moderate correlation with the ACE score.

A possible explanation for the less favorable psychometric indicators of this item may be found in the wording of the item itself: “Were your parents ever separated or divorced?” This is meant to provide information on the fact of separation itself, but eventually raises other relevant questions. Did the parents ever live together? How old was the child when the parents separated? How old was the child when he/she was placed in CWS? When did the parents separate compared to the time of the child’s placement in CWS? Was this a high-conflict separation/divorce or not (62)? Was it the parents’ cohabitation or their separation that had a major contribution more on the child’s placement in CWS?

It is worth noting that 71% of the adolescents in the sample reported having separated parents. This means that the sample can be considered as almost homogeneous in this regard, which may also have contributed to the results described above.

In addition, it is important to note that Hungary has relatively high divorce rates (1.9–2.2/1,000 people) in the European Union (63). It is also known that divorce rates are higher among people of lower socio-economic status (52), which is the social segment from which the majority of children in CWS across Europe are reported (53). This raises the question whether parental separation/divorce as an adverse experience should be asked about in this population at all, and if the psychometric properties of the test were still adequate if the item was omitted.

Accordingly, in the next stage we removed the sixth item and checked the psychometric properties of the 9-item version of the ACE. Our results show that the 9-item version of the test yielded better psychometric properties on the CWS population. In the light of the results, we recommend the careful use of item 6 (“Parental separation/divorce”). We suggest that the relevance of this item should be considered after careful examination of the population to be studied. However, our results also indicate that both the 10-item version or the ACE 9-item version of ACE can provide reliable information with appropriate psychometric properties.

The concurrent criterion validity of the instrument was good in our sample. We found strong and cumulative associations of the total ACE score with emotional and behavioral symptoms and bully victimization. The prevalence and gender distribution of reporting bully perpetration and victimization were similar to those found in other studies, in which girls also dominated in both cases (64). However, contrary to our expectations, the severity of peer relationship problems was independent from the cumulative ACE score. Given the previous evidence on clear correlation between ACE accumulation and the severity of peer problems in the general adolescent population (55), the setting of the CWS may be a clear explanation for our findings. Price and Brew (65) conclude that displacement and transitions themselves present unique social challenges for children. These transitions force them to adapt to new social expectations, such as fitting in with a new peer group. When placed in structured settings like group care, their interactions with peers are limited. These can exacerbate social difficulties that are already present as a result of maltreatment. Taking all these into consideration, the problems of peer relationships are very much related to transitions and dependent on the social context, equally for those reporting fewer or more ACEs. ACEs are individual experiences, but the transition adolescents face and the challenges it brings are collectively present, and collectively make it difficult for these youngsters to build and maintain proper relationships.

Our study respondents were adolescents, which was advantageous for our study: they are closer in time to the period when they experienced the adversities compared to adults. Although children and adolescents may generally differ from adults in their ability to understand long-term consequences and regulate behavior, their cognitive abilities are not significantly different from those of adults (66–68). Similarly, adolescents’ cognition and reliable episodic memory are sufficiently developed to allow their participation in this type of research (69, 70). The advantages of using scores to measure adverse childhood experiences lie in the simplicity of the scores, which facilitates their widespread application in policy, public health and clinical settings. It is particularly important to use an internationally accepted measure to focus attention on this population.

On the other hand, the disadvantage of using a cumulative score is that it fails to take into account the fact that there are other indicators of severity in addition to ACE cumulation, which may be particularly important when assessing children in child protection. The non-representativity of the sample allows no extrapolation of the results, and the sensitive nature of the topic may cause bias and can potentially reduce the willingness of reporting ACEs. Nevertheless, self-report by adolescents is still found to be more reliable than agency records, parental reports of adolescent victimization or adult retrospective self-report (37, 38). A psychometric limitation of our study is that in the absence of other validated trauma questionnaires in Hungarian, convergent validity could not be assessed. In addition, the reliability levels, although acceptable, are at the limit of acceptability. The number of items and sample size also suggest caution.

A further limitation to the results may be that adolescents living in CWS may not recognize the adversities as adversities, as they have been socialized in them. Furthermore, in their case, self-reporting may have a biasing effect as they may wish to be reunited with their family of origin. Also, dissociation and memory deficits may bias the results downwards (71).

The results indicate that both the 10-item version and the 9-item version (without item 6) of the ACE is a valid and reliable measure of childhood adversities among disadvantaged adolescents living in CWS. We suggest that the relevance of item 6 (“Parental separation/divorce”) should be considered in relation with the population under study. Screening for trauma among children in CWS and detailed investigation of trauma types is of utmost importance in CWS, as targeted interventions can be based on these data. In order to follow the principles of trauma-informed care (72, 73), a valid measurement tool is needed as a first step. The ACE questionnaire is a brief, time- and cost-efficient, easy-to-understand instrument, which makes it suitable for disadvantaged children, considering that early impairment can lead to reading, comprehension and learning difficulties (24, 31, 74). Its suitability for repeated testing is another advantage. We see it as an appropriate tool for the purposes of screening, research, and treatment planning.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics approval was issued by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hungarian Medical Research Council under the approval number ETT TUKEB 47848-7/2018/EKU. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

BO: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IKSZ: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. BK-T: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Special thanks to Ágnes Bajzát, Márta Vincze, Ágnes Papp, Regina Nagy, Vivien Kabai, Andrea Tóth, and Kamilla Fazekas for their participation in the process of data collection.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1258798/full#supplementary-material

ACEs, Adverse Childhood Experiences; ACE-10, 10-Item Version of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire; CWS, Child Welfare System; FGC, Family Style Group Care; HBSC, Health Behavior of School Children; HBSC-SCL, Health Behavior of School Children Symptom Checklist; SEB, Social, Emotional and Behavioral Symptoms; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

1. WHO. Social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization. (2023). Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (Accessed October 17, 2023).

2. Jenkins, JVW, Hooper, DP, and De Bellis, SRMD. Direct and indirect effects of brain volume, socioeconomic status and family stress on child Iq. J Child Adolesc Behav. (2013) 1:1000107. doi: 10.4172/2375-4494.1000107

3. Walsh, D, McCartney, G, Smith, M, and Armour, G. Relationship between childhood socioeconomic position and adverse childhood experiences (Aces): a systematic review. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2019) 73:1087–93. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-212738

4. Belsky, J. Etiology of child maltreatment: an ecological integration. Am Psychol. (1980) 35:320–35. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.35.4.320

5. Finkelhor, D, Vanderminden, J, Turner, H, Hamby, S, and Shattuck, A. Child maltreatment rates assessed in a National Household Survey of caregivers and youth. Child Abuse Negl. (2014) 38:1421–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.05.005

6. Moody, G, Cannings-John, R, Hood, K, Kemp, A, and Robling, M. Establishing the international prevalence of self-reported child maltreatment: a systematic review by maltreatment type and gender. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:18. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6044-y

7. Sethi, D, Bellis, M, Hughes, K, Gilbert, R, Mitis, F, and Galea, G. European report on preventing child maltreatment. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe (2013).

8. Stoltenborgh, M, Bakermans-Kranenburg, MJ, and van IJzendoorn, MH. The neglect of child neglect: a Meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Soc Psych Psych Epid. (2013) 48:345–55. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0549-y

9. Ward, CL, Artz, L, Leoschut, L, Kassanjee, R, and Burton, P. Sexual violence against children in South Africa: a nationally representative cross-sectional study of prevalence and correlates. Lancet Glob Health. (2018) 6:E460–e468. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109x(18)30060-3

10. WHO. Global status report on preventing violence against children: World Health Organization. (2020). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/sites/default/files/2020-06/Global-status-report-on-preventing-violence-against-children-2020.pdf (Accessed May 15, 2023).

11. Belsky, J, Hancox, RJ, Sligo, J, and Poulton, R. Does being an older parent attenuate the intergenerational transmission of parenting? Dev Psychol. (2012) 48:1570–4. doi: 10.1037/a0027599

12. Bower-Russa, ME, Knutson, JF, and Winebarger, A. Disciplinary history, adult disciplinary attitudes, and risk for abusive parenting. J Community Psychol. (2001) 29:219–40. doi: 10.1002/jcop.1015

13. Sidebotham, P, Heron, J, and Bristol, ASTU. Child maltreatment in the "children of the nineties": a cohort study of risk factors. Child Abuse Negl. (2006) 30:497–522. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.005

14. Bellis, MA, Hughes, K, Ford, K, Rodriguez, GR, Sethi, D, and Passmore, J. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. (2019) 4:E517–e528. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30145-8

15. Felitti, VJ, Anda, RF, Nordenberg, D, Williamson, DF, Spitz, AM, Edwards, V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults - the adverse childhood experiences (ace) study. Am J Prev Med. (1998) 14:245–58. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

16. Hughes, K, Bellis, MA, Hardcastle, KA, Sethi, D, Butchart, A, Mikton, C, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. (2017) 2:E356–e366. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

17. UNICEF. Children in alternative care. Growing up in an institution puts children at risk of physical, emotional and social harm. (2021). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/protection/children-in-alternative-care (Accessed October 13, 2023).

18. Munro, E. The Munro review of child protection: Final Report, a Child-Centred System. London, UK: The Stationery Office (2011).

19. Collin-Vezina, D, Coleman, K, Milne, L, Sell, J, and Daigneault, I. Trauma experiences, maltreatment-related impairments, and resilience among child welfare youth in residential care. Int J Ment Health Ad. (2011) 9:577–89. doi: 10.1007/s11469-011-9323-8

20. Gallitto, E, Lyons, J, Weegar, K, Romano, E, and Team, MR. Trauma-symptom profiles of adolescents in child welfare. Child Abuse Negl. (2017) 68:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.011

21. Greeson, JKP, Briggs, EC, Kisiel, CL, Layne, CM, Ake, GS, Ko, SJ, et al. Complex trauma and mental health in children and adolescents placed in Foster Care: findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Child Welfare. (2011) 90:91–108.

22. Hodgdon, HB, Liebman, R, Martin, L, Suvak, M, Beserra, K, Rosenblum, W, et al. The effects of trauma type and executive dysfunction on symptom expression of Polyvictimized youth in residential care. J Trauma Stress. (2018) 31:255–64. doi: 10.1002/jts.22267

23. Kisiel, C, Summersett-Ringgold, F, Weil, LEG, and McClelland, G. Understanding strengths in relation to complex trauma and mental health symptoms within child welfare. J Child Fam Stud. (2017) 26:437–51. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0569-4

24. Leloux-Opmeer, H, Kuiper, C, Swaab, H, and Scholte, E. Characteristics of children in Foster Care, family-style group care, and residential care: a scoping review. J Child Fam Stud. (2016) 25:2357–71. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0418-5

25. Lum, JAG, Powell, M, and Snow, PC. The influence of maltreatment history and out-of-home-care on Children's language and social skills. Child Abuse Negl. (2018) 76:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.10.008

26. Oswald, SH, Heil, K, and Goldbeck, L. History of maltreatment and mental health problems in Foster children: a review of the literature. J Pediatr Psychol. (2010) 35:462–72. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp114

27. Mathews, B, Pacella, R, Dunne, MP, Simunovic, M, and Marston, C. Improving measurement of child abuse and neglect: a systematic review and analysis of National Prevalence Studies. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0227884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227884

28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adverse childhood experiences prevention strategy. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021).

29. De Bellis, MD, and Zisk, A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. (2014) 23:185–222. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2014.01.002

30. Teicher, MH, Andersen, SL, Polcari, A, Anderson, CM, Navalta, CP, and Kim, DM. The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2003) 27:33–44. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(03)00007-1

31. Shonkoff, JP, Garner, AS, Fa, CPAC, Depe, CECA, and Pediat, SDB. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. (2012) 129:E232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663

32. Doyle, C, and Cicchetti, D. From the cradle to the grave: the effect of adverse caregiving environments on attachment and relationships throughout the lifespan. Clin Psychol. (2017) 24:203–17. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12192

33. Riggs, SA. Childhood emotional abuse and the attachment system across the life cycle: what theory and research tell us. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. (2010) 19:5–51. doi: 10.1080/10926770903475968

34. Sheffler, JL, Piazza, JR, Quin, JM, Sachs-Ericsson, NJ, and Stanley, IH. Adverse childhood experiences and coping strategies: identifying pathways to resiliency in adulthood. Anxiety Stress Copin. (2019) 32:594–609. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2019.1638699

35. Bethell, CD, Carle, A, Hudziak, J, Gombojav, N, Powers, K, Wade, R, et al. Methods to assess adverse childhood experiences of children and families: toward approaches to promote child well-being in policy and practice. Acad Pediatr. (2017) 17:S51–69. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.04.161

36. Lacey, RE, and Minnis, H. Practitioner review: twenty years of research with adverse childhood experience scores - advantages, disadvantages and applications to practice. J Child Psychol Psyc. (2020) 61:116–30. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13135

37. Hardt, J, and Rutter, M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psyc. (2004) 45:260–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x

38. Johnsona, R, Kotch, J, Catellier, D, Winsor, J, Dufort, V, Hunter, W, et al. Adverse Behavioural and emotional outcomes from child abuse and witnessed violence. Child Maltreat. (2002) 7:179–86. doi: 10.1177/1077559502007003001

39. Manly, JT. Advances in research definitions of child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. (2005) 29:425–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.04.001

40. Fisher, BS. The effects of survey question wording on rape estimates evidence from a quasi-experimental design. Violence against Wom. (2009) 15:133–47. doi: 10.1177/1077801208329391

41. Finkelhor, D, Ormrod, RK, and Turner, HA. Re-victimization patterns in a National Longitudinal Sample of children and youth. Child Abuse Negl. (2007) 31:479–502. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.012

42. Gilbert, R, Widom, CS, Browne, K, Fergusson, D, Webb, E, and Janson, S. Child maltreatment 1 burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. (2009) 373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7

43. Hagborg, JM, Kalin, T, and Gerdner, A. The childhood trauma questionnaire-short form (Ctq-sf) used with adolescents - methodological report from clinical and community samples. J Child Adoles Traum. (2022) 15:1199–213. doi: 10.1007/s40653-022-00443-8

44. Hamby, SL, Finkelhor, D, Ormrod, RK, and Turner, HA. The juvenile victimization questionnaire (Jvq): Administration and scoring manual. Durham, NH: Crimes Against Children Research Center (2004).

45. Meinck, F, Cosma, A, Mikton, C, and Baban, A. Psychometric properties of the adverse childhood experiences abuse short form (ace-Asf) among Romanian high school students. Child Abuse Negl. (2017) 72:326–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.08.016

46. Kovacs-Toth, B, Olah, B, Szabo, IK, and Fekete, Z. Psychometric properties of the adverse childhood experiences questionnaire 10 item version (ace-10) among Hungarian adolescents. Front Psychol. (2023) 14:14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1161620

47. Goodman, R, Meltzer, H, and Bailey, V. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur Child Adoles Psy. (1998) 7:125–30. doi: 10.1007/s007870050057

48. Turi, E, Toth, I, and Gervai, J. Further examination of the strength and difficulties questionnaire (Sdq-Magy) in a community sample of Young adolescents (Képességek És Nehézségek Kérdőív (Sdq-Magy) További Vizsgálata Nem-Klinikai Mintán, Fiatal Serdülők Körében). Psychiatr Hung. (2011) 26:415–26.

49. Inchley, JCD, Young, T, Samdal, O, Torsheim, T, Augustson, L, Mathison, F, et al. Growing up unequal: gender and socioeconomic differences in Young People’s health and well-being. International Report from the 2013/2014 Survey. (2016). Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/303438/HSBC-No.7-Growing-up-unequal-Full-Report.pdf (Accessed September 15, 2021).

50. Németh, Á, and Költő, A. Health behaviour in school-aged children [Hbsc]: a who-collaborative cross-National Study National Report 2014 [Egészség És Egészségmagatartás Iskoláskorban. Nemzeti Jelentés]. (2014). Available at: http://mek.oszk.hu/16100/16119/16119.pdf (Accessed September, 15, 2020).

51. Afifi, TO, Taillieu, T, Salmon, S, Davila, IG, Stewart-Tufescu, A, Fortier, J, et al. Adverse childhood experiences (Aces), peer victimization, and substance use among adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. (2020) 106:106. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104504

52. Duke, NN, Pettingell, SL, McMorris, BJ, and Borowsky, IW. Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. (2010) 125:E778–e786. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0597

53. Flaherty, EG, Thompson, R, Litrownik, AJ, Theodore, A, English, DJ, Black, MM, et al. Effect of early childhood adversity on child health. Arch Pediat Adol Med. (2006) 160:1232–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.12.1232

54. Forster, M, Gower, AL, McMorris, BJ, and Borowsky, IW. Adverse childhood experiences and school-based victimization and perpetration. J Interpers Violence. (2020) 35:662–81. doi: 10.1177/0886260517689885

55. Kovacs-Toth, B, Olah, B, Papp, G, and Szabo, IK. Assessing adverse childhood experiences, social, emotional, and behavioral symptoms, and subjective health complaints among Hungarian adolescents. Child Adol Psych Men. (2021) 15:12. doi: 10.1186/s13034-021-00365-7

56. Anda, RF, Butchart, A, Felitti, VJ, and Brown, DW. Building a framework for global surveillance of the public health implications of adverse childhood experiences. Am J Prev Med. (2010) 39:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.015

57. Ford, DC, Merrick, MT, Parks, SE, Breiding, MJ, Gilbert, LK, Edwards, VJ, et al. Examination of the factorial structure of adverse childhood experiences and recommendations for three subscale scores. Psychol Violence. (2014) 4:432–44. doi: 10.1037/a0037723

58. Birkás, E, Lakatos, K, Tóth, I, and Gervai, J. Screening childhood behavior problems using short questionnaires I.: the Hungarian version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Psychiatr Hung. (2008) 23:358–65.

59. Currie, C, Gabhainn, SN, Godeau, E, Network, IHBSC, and Comm, C. The health behaviour in school-aged children: who collaborative cross-national (Hbsc) study: origins, concept, history and development 1982-2008. Int J Public Health. (2009) 54:131–9. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-5404-x

60. Solberg, ME, and Olweus, D. Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus bully victim questionnaire. Aggressive Behav. (2003) 29:239–68. doi: 10.1002/ab.10047

61. Roberson, AJ, and Renshaw, TL. Structural validity of the Hbsc bullying measure: self-report rating scales of youth victimization and perpetration behavior. J Psychoeduc Assess. (2018) 36:628–43. doi: 10.1177/0734282917696932

62. Joyce, AN. High-conflict divorce: a form of child neglect. Family Court Rev. (2016) 54:642–56. doi: 10.1111/fcre.12249

64. Mohapatra, S, Irving, H, Paglia-Boak, A, Wekerle, C, Adlaf, E, and Rehm, J. History of family involvement with child protective services as a risk factor for bullying in Ontario schools. Child Adol Ment H-Uk. (2010) 15:157–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2009.00552.x

65. Price, JM, and Brew, V. Peer relationships of Foster children: developmental and mental health service implications. J Appl Dev Psychol. (1998) 19:199–218. doi: 10.1016/S0193-3973(99)80036-7

66. Albert, D, and Steinberg, L. Judgment and decision making in adolescence. J Res Adolescence. (2011) 21:211–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00724.x

67. Casey, BJ, Jones, RM, and Hare, TA. The adolescent brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2008) 1124:111–26. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.010

68. Steinberg, L, Icenogle, G, Shulman, EP, Breiner, K, Chein, J, Bacchini, D, et al. Around the world, adolescence is a time of heightened sensation seeking and immature self-regulation. Dev Sci. (2018) 21:10.1111/desc.12532. doi: 10.1111/desc.12532

69. Borgers, N, De Leeuw, E, and Hox, J. Children as respondents in survey research: cognitive development and response quality (2000) 66:60–75. doi: 10.1177/075910630006600106,

70. Riley, AW. Evidence that school-age children can self-report on their health. Ambul Pediatr. (2004) 4:371–6. doi: 10.1367/A03-178r.1

71. Baldwin, JR, Reuben, A, Newbury, JB, and Danese, A. Agreement between prospective and retrospective measures of childhood maltreatment: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat. (2019) 76:584–93. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0097

72. Kramer, TL, Sigel, BA, Conners-Burrow, NA, Savary, PE, and Tempel, A. A statewide introduction of trauma-informed care in a child welfare system. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2013) 35:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.10.014

73. Zhang, SJ, Conner, A, Lim, Y, and Lefmann, T. Trauma-informed Care for Children Involved with the child welfare system: a Meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. (2021) 122:122. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105296

74. Sonuga-Barke, EJS, Kennedy, M, Kumsta, R, Knights, N, Golm, D, Rutter, M, et al. Child-to-adult neurodevelopmental and mental health trajectories after early life deprivation: the Young adult follow-up of the longitudinal English and Romanian adoptees study. Lancet. (2017) 389:1539–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30045-4

Keywords: adolescence, adverse childhood experiences, child welfare system, family dysfunction, maltreatment, measures, psychometrics, validation

Citation: Oláh B, Fekete Z, Kuritárné Szabó I and Kovács-Tóth B (2023) Validity and reliability of the 10-Item Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (ACE-10) among adolescents in the child welfare system. Front. Public Health. 11:1258798. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1258798

Received: 17 July 2023; Accepted: 02 November 2023;

Published: 17 November 2023.

Edited by:

Wulf Rössler, Charité University Medicine Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Andrómeda Ivette Valencia-Ortiz, Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo, MexicoCopyright © 2023 Oláh, Fekete, Kuritárné Szabó and Kovács-Tóth. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Beáta Kovács-Tóth, a292YWNzLXRvdGguYmVhdGFAbWVkLnVuaWRlYi5odQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.