- Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action, Mumbai, India

Background: The burden of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) in urban informal settlements across Lower and Middle Income Countries is increasing. In recognition, there has been interest in fine-tuning policies on NCDs to meet the unique needs of people living in these settlements. To inform such policy efforts, we studied the care-seeking journeys of people living in urban informal settlements for two NCDs—diabetes and hypertension. The study was done in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region, India.

Methods: This qualitative study was based on interviews with patients having diabetes and hypertension, supplemented by interactions with the general community, private doctors, and public sector staff. We conducted a total of 47 interviews and 6 Focus Group Discussions. We synthesized data thematically and used the qualitative software NVivo Version 10.3 to aid the process. In this paper, we report on themes that we, as a team, interpreted as striking and policy-relevant features of peoples’ journeys.

Results: People recounted having long and convoluted care-seeking journeys for the two NCDs we studied. There were several delays in diagnosis and treatment initiation. Most people’s first point of contact for medical care were local physicians with a non-allopathic degree, who were not always able to diagnose the two NCDs. People reported seeking care from a multitude of healthcare providers (public and private), and repeatedly switched providers. Their stories often comprised multiple points of diagnosis, re-diagnosis, treatment initiation, and treatment adjustments. Advice from neighbors, friends, and family played an essential role in shaping the care-seeking process. Trade-offs between saving costs and obtaining relief from symptoms were made constantly.

Conclusion: Our paper attempts to bring the voices of people to the forefront of policies on NCDs. People’s convoluted journeys with numerous switches between providers indicate the need for trusted “first-contact” points for NCD care. Integrating care across providers—public and private—in urban informal settlements—can go a long way in streamlining the NCD care-seeking process and making care more affordable for people. Educating the community on NCD prevention, screening, and treatment adherence; and establishing local support mechanisms (such as patient groups) may also help optimize people’s care-seeking pathways.

1 Introduction

Recently, urban informal settlements across Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) have noted an increase in the burden of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) (1–3). Evidence suggests that residents of such settlements are at increased risk for NCDs due to a range of factors, including chronic stress, unfavorable working conditions, poor diets, and environmental pollution (4–6). Furthermore, access to high-quality healthcare is frequently lacking in such areas (7, 8). The adverse influence of financial insecurity and social marginalization, added to all of this (9, 10), further compromises NCD outcomes in this population group.

As a consequence, there is interest across LMICs in aligning and fine-tuning health policies to respond to the increasing NCD burden in urban informal settlements. One compelling way to aid such policy endeavors is through empirical understandings of people’s care-seeking journeys for NCDs in these spaces. A care-seeking journey is characterized as a sequence of actions that begins with awareness about something not being right, following which intervention from formal and informal health resources is sought (11). Examining care-seeking journeys can enable contextualized understandings of people’s physical and emotional experiences and, thereby, help include community voices in policy discussions (12–14). Studies of patient journeys in the past have provided policy evidence for strengthening diagnostic processes, tweaking treatment regimens, and reducing delays in the care-seeking process (15, 16). Overall, such inquiries have served as important tools for making health policies more people-centered (17). Indeed, the recent “intent to action” series by the World Health Organization treats the lived experiences of patients as key evidence for improving NCD policies (18).

This study aims to get deeper insights into the care-seeking journeys of people for two NCDs—diabetes and hypertension. The study was done in three informal settlements in the peripheral areas of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region in India. The two NCDs—diabetes and hypertension—were chosen since a high prevalence of these diseases has been reported in urban informal settlements in India (19, 20).

This qualitative study adds to existing evidence on care-seeking journeys for NCDs in LMICs. Earlier studies on this topic have highlighted issues of delayed diagnosis and lack of continuity in NCD care—owing to poor quality primary healthcare systems, cost concerns, and a lack of clarity over where to seek care, inter alia (12, 16, 21). We add to this evidence a study that considers the unique context of urban informal settlements, such as the existence of a mixed (public and private) health system and the resource constraints faced by the urban poor in accessing care.

1.1 Indian context

In India, Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) attributed to NCDs has risen from 30% in 1990 to 55% in 2016 (22). A recently undertaken nationally representative population-based study in India estimated the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension as 11.4 and 35.5% respectively, with a higher burden of NCDs in urban areas compared to rural areas (23). Whereas NCDs were earlier perceived as “diseases of the rich” (1), confined to the urban elite, there is increasing recognition that the urban poor are also vulnerable to this set of diseases (24, 25).

The urban public health system, particularly at primary levels of care, is underdeveloped in most places in the country (26, 27). Also, this system has conventionally focussed on providing select services for maternal and child health, and certain infectious diseases of national priority. Though a national program to combat NCDs has existed for many years in the country, the intent to integrate NCD care comprehensively into all tiers of the public health system has only recently gained political priority (28). Presently, policies in India strongly support free screening, treatment, and management of NCDs through the public health system (28, 29). However, the implementation of policies on NCDs has not been without challenges. The addition of NCD services appears to put even more pressure on the nation’s already overburdened and under-resourced public health system (30).

At present, much of primary-level curative care in India happens in the private sector, through out-of-pocket payments, and in the hands of Non Degree Allopathic Practitioners (NDAPs) (31–33). NDAPs practice allopathy without formal qualifications in modern medicine in close proximity to the community (32, 34). There is evidence that NDAPs are often the first-contact points for care for most minor acute ailments in both rural areas and urban slums in the country (32, 35). But at present, their role in the diagnosis and treatment of NCDs is less documented. In general, the nuances of care-seeking for NCDs is less understood in the Indian context. This study is an attempt to elucidate the nuances of care-seeking for two common NCDs, diabetes and hypertension, by the urban poor.

2 Methods

2.1 Study setting

This study was done in a peripheral Municipal Corporation (urban geographical region under a local governing body) in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region, Maharashtra, India. This corporation has a population of 0.7 million, of which 44% live in informal settlements. The density of people per square kilometer is 26,871 (36). Historically, these settlements grew around a textile industry hub. Hence, many of these settlements are home to migrants who work in the loom industry. The study area has access to a mix of public and private healthcare providers. One public secondary-level hospital (100 beds) serves as a referral unit for 15 primary-level facilities operating under this Municipality.

2.2 Study design

This is a cross-sectional, qualitative study that employs quasi-inductive approaches to examine patient journeys. Such approaches allow for context-specific theorization grounded in data from research participants even while pragmatically allowing learnings from existing theories and frameworks to be incorporated in the analysis (37, 38). The data in this study mainly comprises interviews with patients with diabetes (10 patients) or hypertension (9 patients) or both (7 patients) who shared their care-seeking stories with us based on their memories. These interviews were supplemented with information from community-level group discussions (40 participants), visits to the public secondary-level hospital and one primary-level facility in the area (13 participants), and interviews with local private healthcare providers (8 participants). The supplementary information we collected enabled us to understand the care-seeking journeys of patients from a broader perspective that acknowledged the context of healthcare provision in this area.

2.3 Participant selection and recruitment

This study was conducted in the field areas of the Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action (SNEHA), a nongovernmental organization that has been working in urban informal settlements in Mumbai since 1999. SNEHA has a long-standing relationship with the community in the study area. The field staff of SNEHA initially identified patients, community members, and doctors based on the diversity criteria suggested by the research team. In their work related to maternal and child health, the field staff regularly perform home visits within the community. During these visits, they identified individuals within the family who had diabetes and hypertension. They explained to them the purpose of the study and inquired about their willingness to participate. Similarly, SNEHA also works closely with the public health system in the area to establish a stronger link between the healthcare systems and the community. This collaboration allowed us to engage with the public health staff to collect data. The researchers from SNEHA thereafter conducted the interviews and discussions as per the participants’ convenience after a formal process of informed consent. We purposively sampled for diversity in age and gender (all study participants), migration status (all community participants), and years of diagnosis/treatment of the disease (only patients).

2.4 Data collection

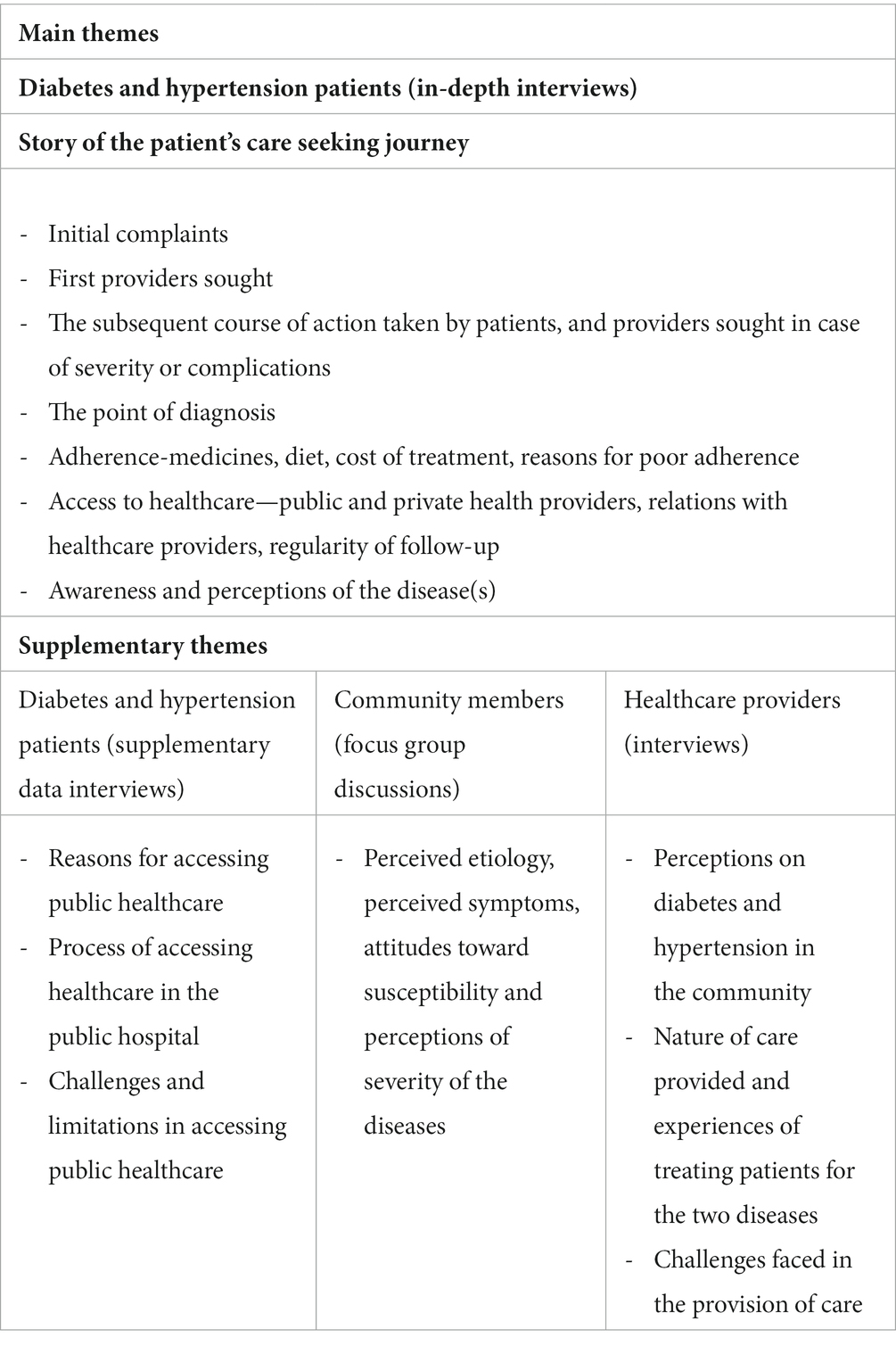

Data collection was done from September to December 2022. The main topics discussed during our interactions are summarized in Table 1. A total of 34 in-depth interviews (IDIs), 13 short-duration interviews, and 6 Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were conducted. Out of 26 patients interviewed, 18 were above 50 years of age and many (17) had lived in the community for more than two decades. An equal number of men and women patients (13 each) were interviewed. Diversity in years of diagnosis was ensured—11 patients were diagnosed 2 years prior to the interaction, 7 between 3 and 5 years and 8 were diagnosed more than 5 years prior to the interaction. Forty community members participated in the FGDs, of which 27 were less than 35 years old and 13 were male. Majority (27) had lived in the community for more than a decade. Details of the participants’ demographics are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

The participants’ preferred local languages, Hindi and Marathi, were used during the interactions. Authors MB, JS, and SR conducted the interactions; all three are well-trained in qualitative data collection methods and familiar with the local context. On average, the IDIs and FGDs lasted 20–30 min. The interviews with patients were conducted in their homes while those with healthcare professionals were conducted in their workplaces. FGDs, facilitated by a moderator (MB or JS) and a note-taker, were held in anganwadis (local government playschools) or one of the participants’ homes. Short-duration interviews (lasting 10–15 min each) were conducted outside the NCD outpatient department of the public hospital when patients were either waiting for consultation or exiting after consultation. Similar interviews with public health staff were conducted after their working hours on the hospital premises. These interviews took less time since they were meant to provide only supplementary information on patient care pathways, and validate the concerns raised by patients in our study. Such supplementary interviews are a well-established mechanism in qualitative research to triangulate information, in order to ensure data quality (39).

As is the practice in qualitative studies, the exact sample size was not pre-determined. We used the concept of information redundancy as a criterion to ensure data saturation, after which, we stopped the recruitment of additional participants.

2.5 Data analysis

All interactions with community members and patients (except the eight short-duration supplementary interviews at the hospital) were recorded. Of the eight interviews with private providers, five were recorded; and of the five interviews with public health staff, three were recorded (as per the participants’ preferences). These recordings were transcribed into English for further analysis. Individuals who were proficient in Hindi, Marathi and English carried out the translation and transcription. Subsequently, MB and JS listened to the audio recordings and reviewed the transcribed content to ensure quality. For the non-recorded interviews, we took detailed field notes. As is typical of qualitative studies, data analysis processes were initiated simultaneously with data collection (40).

We followed the steps that Miles and Huberman recommend for the analysis of data, starting with data reduction (initial condensing), then working with data displays (compressed assemblies of information), and finally, drawing meaningful interpretations (38). We had data debriefing sessions after every data collection visit to discuss emerging themes. Ideas from the transcripts were also discussed in a team to arrive at a standard set of codes. The transcripts and field notes were sorted and coded using the qualitative software NVivo Version 10.3.

2.6 The analytical framework used

To choose an analytical framework for our study, we examined existing literature on patient journeys for NCDs. We found that many papers used clinical headings—such as diagnosis, initiation of treatment, follow up and management of the disease—to explicate the patient journey (11, 41–43). For example, a recent review of NCDs in LMICs used the term “touchpoints” (awareness, screening, diagnosis, treatment, and adherence) to describe the patient journey through the health system (11). Other articles have also noted the importance of examining patient journeys through a “continuum of care” approach as care-seeking for NCDs should ideally involve multiple follow-ups with repeated points of contact with the health system (44, 45).

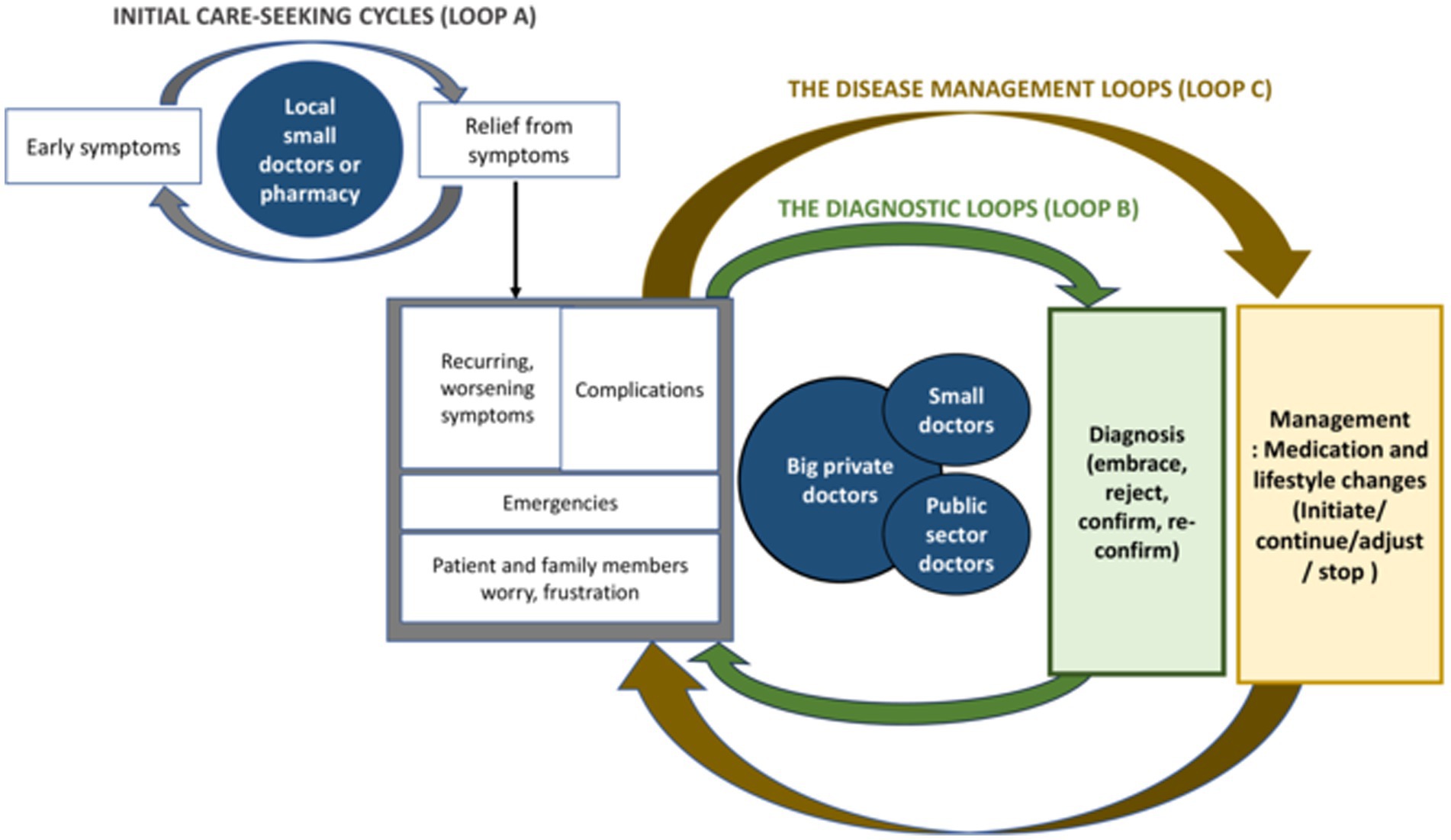

These ideas informed the initial tools of our study. We also based our preliminary analysis on the different “touchpoints” we encountered in patient stories. But our preliminary analysis revealed that some of the unique findings in our context did not fit into the existing frameworks very well. For instance, patient journeys in our study appeared to be highly convoluted and could not be confined to distinct touchpoints alone. Further, given the existence of a mixed (public and private) and pluralistic (allopathic and alternate medicine) healthcare system in India (46), there was constant “hopping” between different providers for NCD care. These issues were not being captured through existing NCD care-seeking frameworks. Thus, in our paper, we have built further on existing ideas and employed quasi-inductive approaches to develop a framework (38) to better represent that chaotic situation of care-seeking for NCDs on the ground. Since this framework evolved iteratively from our data, we have discussed it at the end of the paper (see Figure 1).

2.7 Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the research was obtained from Sigma Research and Consulting Pvt. Ltd. on 28th September 2022. Informed consent was verbally obtained from all participants. In cases where the participant granted permission to audio record the interviews, the consent and ensuing interactions were recorded on a smartphone device. In cases where the participants did not agree to audio recording, non-recorded verbal consent was obtained, and field notes were taken during and after the interaction. Permissions were obtained from the municipal ward corporator responsible for the population under study and relevant public health system authorities in the area.

3 Findings

People recounted having long and convoluted care-seeking journeys for the two NCDs we studied. These journeys often involved multiple “hops” between different kinds of providers, as well as experimentation with different types of treatment regimens. In most of the stories we heard, the diagnosis of the two NCDs was delayed until people’s life routines were extensively disrupted due to worsening symptoms. Further, few people spoke of routine follow-ups. In this section, we have described some of the salient features of people’s care-seeking journeys that our team interpreted as noteworthy.

3.1 Initial complaints and the first providers sought

Many patients began their stories by talking about symptoms that interfered with their lives. These symptoms often included headaches, body pain, anxiety, dizziness, and tiredness. Since patients’ early memories were hazy, it was challenging to determine how long these symptoms had manifested in people’s lives prior to a formal diagnosis. Most patients said that they dealt with these early, not-very-serious symptoms by going to a nearby source of healthcare, such as a pharmacy (drugstore) for over-the-counter drugs and visiting a local private doctor referred to as a “small” doctor:

“His clinic is not big but has been there for many years. All members of our family get medicine only from him. On this road, he is a famous doctor. He himself gives the medicine. He takes only fifty rupees” (Female, 32 years, diagnosed with diabetes six months prior to the interaction).

“Over time when I started feeling uneasy, I went to my family doctor. He said my BP (blood pressure) was high, so he gave me a pill to keep it on my tongue. He also asked me to visit a big doctor” (Male, 52 years, diagnosed with hypertension eight years prior to the interaction).

“Small” doctors were typically NDAPs, had private clinics within the narrow lanes of the informal settlements, and were easily accessible to people. Patients shared that “small” doctors spoke kindly, often provided “small” medicines during the consultation, and, importantly, charged fees that they could afford. These fees were typically only a fraction of the fee charged by an urban allopathic doctor (Allopathic doctors charged 500 to 1,000 Indian National Rupees (INR) and in contrast, these doctors took a fee of 50 to 100 INR). The ‘small’ doctors also shared that they occasionally accommodated patients’ requests by deferring taking fees for consultation until the patients could afford to pay them.

Many “small” doctors admitted that they usually provided symptomatic treatment for minor ailments:

“If someone feels uneasy, I give them medicine to help them relax. I make them lie down with their legs up, and I make them chew on ginger. Because of this, the heaviness in their chest and lack of oxygen starts recovering” (Small doctor, clinical practice for twenty-five years).

Less than one-fourth of the patients we interviewed had been diagnosed by the “small” doctors. These doctors preferred to refer patients to more qualified doctors for the formal diagnosis and continued treatment of NCDs. Long-term treatment for NCDs was perceived as costly. One doctor also noted that recommending such long-term, costly treatment regimens to patients would undermine their reputation as a reasonably-priced doctor and have a negative impact on their practice.

3.2 The subsequent journey involved many “hops” between different kinds of providers

When the symptoms experienced by patients were not controlled as anticipated, people did one or more of the following. They either returned to the “small” doctors with more extensive complaints or reached out to “big” private doctors. “Big” private doctors usually possessed at least an undergraduate degree in allopathic medicine, and their workspaces were outside the informal settlements and sometimes even in adjoining cities. Less often, people reported seeking care from the public sector and non-profit hospitals.

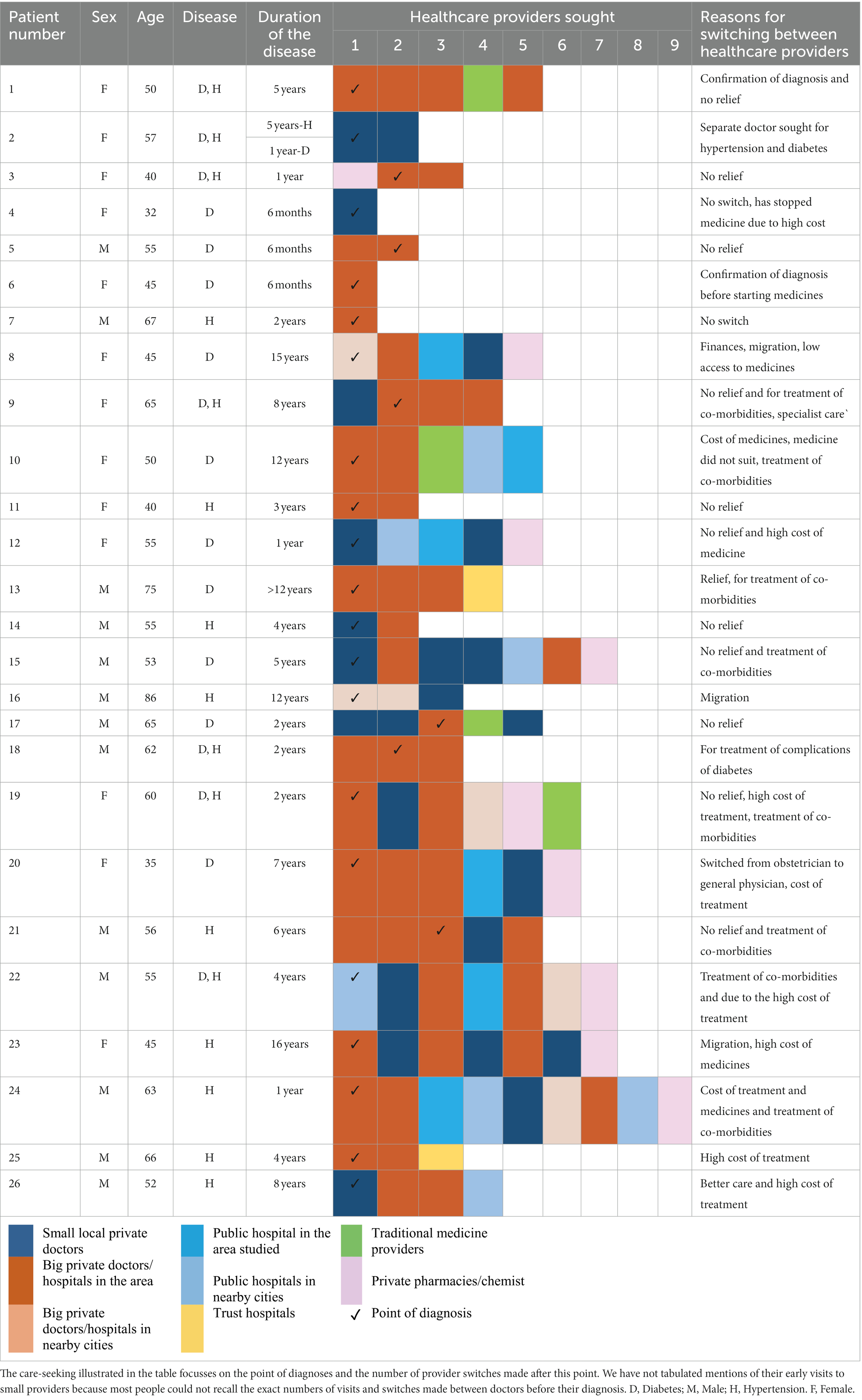

One of the most striking features of this part of the care-seeking journey was the multitude of providers sought by people. Table 2 notes the number of providers sought by each patient we spoke to. We found that most patients switched providers multiple times, including hopping between “small” and “big” doctors, the public and private sectors (profit and non-profit), and the allopathic and alternate medicine sectors. We found only three patients who recalled visiting just one doctor as part of this journey (and two of these three patients reported being diagnosed only 6 months prior to our interaction with them).

People reported switching providers for multiple reasons, including the confirmation of diagnoses; no improvement in symptoms; in search of better-suited treatment; due to co-morbidities; to avoid the high cost of consultations that people could not afford at certain points in time; and based on the assortment of advice they received from well-wishers on the varied expertise of different healthcare providers.

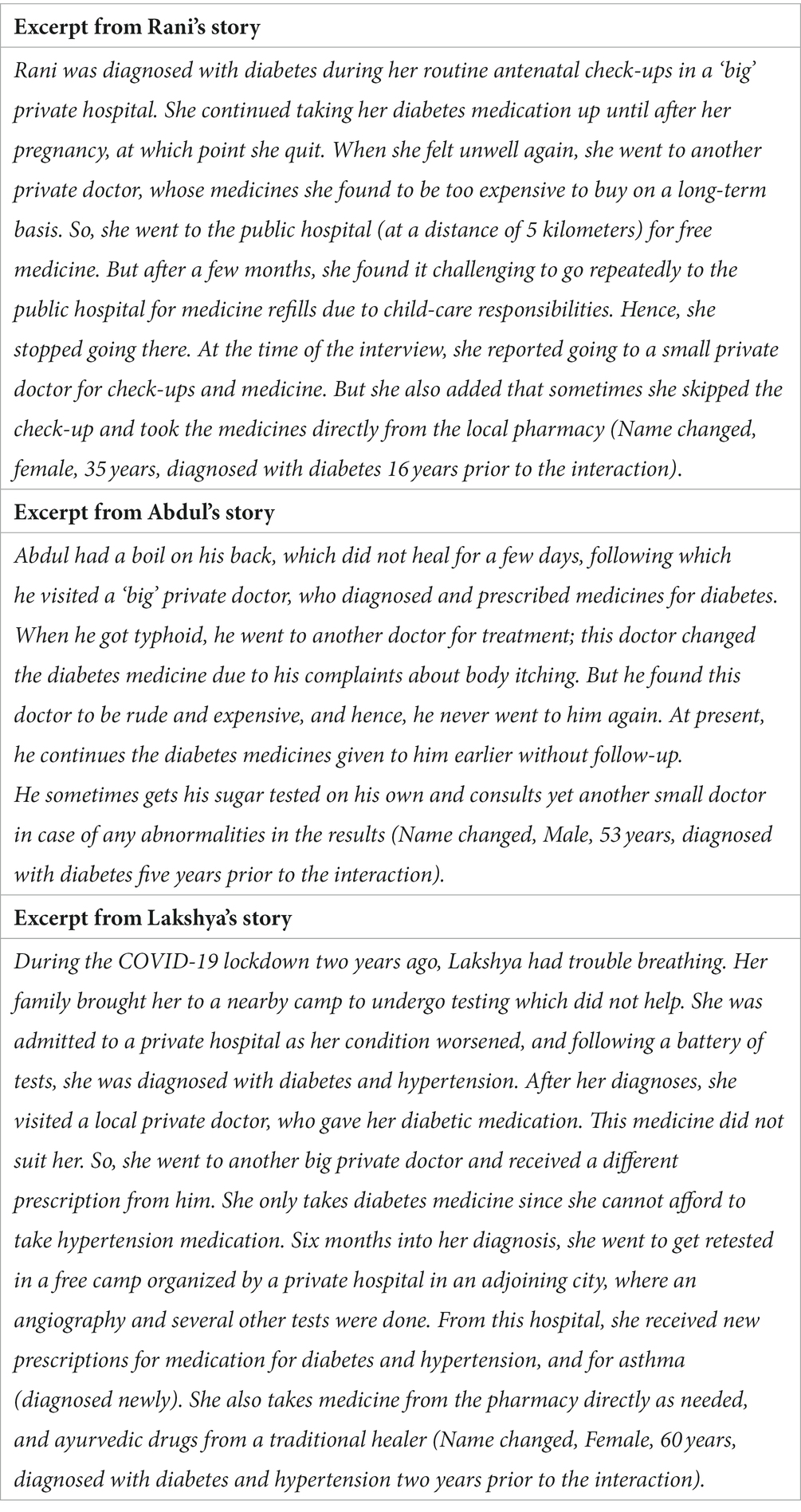

The reasons shared by people for switching doctors signal the lack of a clear-cut pathway for accessing NCD care. To begin with, the familiar circle of “small” doctors, whom people were accustomed to, could often not diagnose or treat NCDs in this setting. Thus, people had to explore a previously unexplored set of providers—the “big” private doctors—who were more qualified but, at the same time, costlier. Patients often expressed feeling powerless in the face of the high costs they incurred at the “big” private clinics. They also felt uneasy asking the “big” doctors (who were perceived as very busy) for advice and questioned the legitimacy of the tests prescribed by these doctors. This lack of familiarity with the formal private sector also contributed to extensive experimentation with different kinds of providers and diverse treatment regimens. Advice from well-wishers (family and friends) and “try and see” attitudes appeared to guide the entire care-seeking journey. The three cases in Table 3 illustrate some of these points.

3.3 The care-seeking journey was cyclic, with multiple diagnoses and treatment points

We found that people did not move from awareness to diagnosis and further from diagnosis to treatment in a linear manner. People’s stories often comprised multiple points of diagnosis and re-diagnosis; and multiple points of treatment initiation, adjustment, stopping, and re-initiation. Since these points were often cyclically encountered, we have described these points in terms of two “loops” in the care-seeking journey: the diagnostic loops and the disease management loops. We have explained these two loops below, but also discuss these further in Figure 1 in section 4 of the paper.

3.3.1 The diagnostic loops

Around three-fourths of the patients we interviewed reported that their diagnosis was done at the “big” private doctor (see Table 2, which marks the point of first diagnosis). However, this diagnosis did not immediately or always lead to effective treatment and management. This was because patients often ignored the early diagnosis, only to be re-diagnosed subsequently after the symptoms worsened. A few went to a range of doctors to confirm their diagnosis before believing it. For instance, one woman who was diagnosed with diabetes by a skin specialist found it hard to see the connection between diabetes and her skin problems, and struggled to believe her diagnosis:

“I had a cut that did not heal and became painful. I went to a private skin doctor, who diagnosed me with diabetes. But my family was worried and asked me to confirm. I went to another doctor to confirm, and there it also showed up. I went to five doctors in total. When they all told me I have sugar (diabetes), that is when I believed it” (Female, 60 years, diagnosed with diabetes five years prior to the interaction).

Some others got diagnosed, initiated, and then stopped treatment and subsequently had to be re-diagnosed. Additionally, the re-diagnosis was frequently done by healthcare providers who were not necessarily aware of the patient’s history.

There were two departures from this typical diagnostic pathway. One departure occurred when the diagnosis happened incidentally. We interviewed five patients who had gone to the hospital for various reasons (such as a COVID-19 test or vaccine or a pregnancy check-up) and discovered that they had diabetes or hypertension by chance. The second departure occurred in five cases, where the diagnosis was made extremely late, when the patients were admitted to a hospital, frequently with a stroke or a heart attack. The quote below is from one such patient:

“I had a heart attack, and I went from one private hospital to another before finally going to a public hospital in Mumbai. There, they did my angioplasty… At that time, I found out that I had hypertension” (Male, 63 years, diagnosed with hypertension two years prior to the interaction).

3.3.2 The many loops in the management of diabetes and hypertension

We found several variations in the ways that patients worked with their treatment regimens. They sometimes completely stopped all medicines; or adjusted dosages on their own; or took partial medicines; or reserved costlier allopathic medicines only for emergencies while opting for home remedies and alternative medicine on a routine basis. In many stories, people reported taking medication in a cyclic manner. That is, they stopped when they felt better or had financial constraints; and restarted when the symptoms emerged again. Fatima’s case below is an illustrative example of how people adjusted their medicine cyclically.

Fatima lived in a modest one-room house with her family. She had a bedridden husband and a daughter who was mentally challenged. Her son earns, and she supplements his income by pearl-beading necklaces. Upon being diagnosed with diabetes, she took medicines from a private doctor (who charged her reduced fees). Fatima took these medicines for some time, but when she started feeling better, she stopped taking them to save money. After a few months, her symptoms reappeared. She again went to the doctor, who requested that she continue the medicine. However, the cost of medicine was too high for her. So, she went to the public hospital for free medicines on the advice of a neighbour. But she felt the medicines given by the public hospital were too strong for her, and she discontinued them. Currently, she purchases the medicines prescribed by the earlier private doctor whenever she has some money and stops them on days when she feels better (Name changed, female, 55 years, diagnosed with diabetes one year prior to the interaction).

A few patients also reported restarting their discontinued medicines after facing dire consequences (like a heart attack). Such patients often admitted to having “learnt their lesson” on playing with medication. Adherence to treatment also appeared to benefit from the presence of supportive family members. In this regard, male patients frequently referred to their wives, who would remind them to take their medications and make wholesome meals for them to eat.

3.4 The constant balancing act between getting relief and lowering costs

Throughout their care-seeking journeys, people in urban informal settlements continually attempted to strike a compromise between the need for relief and the need for lowering costs. For instance, when poor health hindered livelihoods and daily routines, patients shifted from “small” private doctors to more expensive big private doctors. Conversely, when people felt better, and the symptoms were less severe, or the costs of big private doctors became burdensome, they shifted from private to public doctors and from costlier allopathic medicines to cheaper traditional medicines. People also tried to save costs by adjusting their treatment regimens—they took medicines intermittently, bought partial medicines, or continued medicines without regular check-ups. The following quotes emphatically illustrate the trade-offs that people made between saving money and getting relief.

“I am not able to take medicines regularly. The diabetes medicine I was advised, they are so expensive. If we have money, I get it (medicines). Otherwise, I take one Ayurvedic syrup. Only if my condition gets worse, I take the allopathy medicine” (Female, 60 years, diagnosed with diabetes two years prior to the interaction).

“Now I am old, so they (the loom owners) do not use me for running the machines. I am sitting idle for one and a half months with no work. If I go to the private doctor, he will give me two injections and three-times medicine and will take 100 rupees. If he writes medicine (to be bought) from outside, then 150 rupees. He gave me a strip of medicine from which I take half a tablet every day (Male, 65 years, diagnosed with diabetes two years prior to the interaction).

The doctor lectures me and says that when he tells me first to get checked up and then take the medicine, I do not listen to him. To save a few rupees, I buy the medicine from the shop and take it (Female, 45 years, diagnosed with hypertension 16 years prior to the interaction).

Recognizing the inability of vulnerable population groups to pay out of pocket for chronic illnesses, free services for hypertension and diabetes has been made available in the public health sector in India. However, these free services were perceived as being far from adequate by the community. Interviews at the referral hospital in the area revealed that though the facility had a specific cell for NCDs, the doctor’s position has been vacant for the last 6 months. When we visited, an overworked substitute doctor was overseeing the diagnosis and the disbursal of medicines for a few NCDs. Also, we were told during the interviews that medicines for both diabetes and hypertension were not always available or sufficient. The public sector outreach workers associated with primary-level public health facilities were only partially trained and had not yet formally been assigned responsibilities pertaining to NCD care. Further, we found that the community was often unaware of the availability of NCD services in the public sector. People also shared past experiences of long waiting hours, rudeness of staff, and feelings of not being treated well in public facilities in the area studied. Quoting from one patient interview:

“It is not that we do not want to go there (public hospital). We would save some hard-earned money if we do that. If only they provide us with information properly” (Female, 32 years, diagnosed with diabetes six months prior to the interaction).

Such experiences generally discouraged care-seeking from the public health sector or compelled patients to travel to better public hospitals in nearby cities in the metropolitan region when needed.

3.5 Lay perceptions: notable absence of the concept of prevention of NCDs in communities

3.5.1 Perceptions of the community about diabetes and hypertension

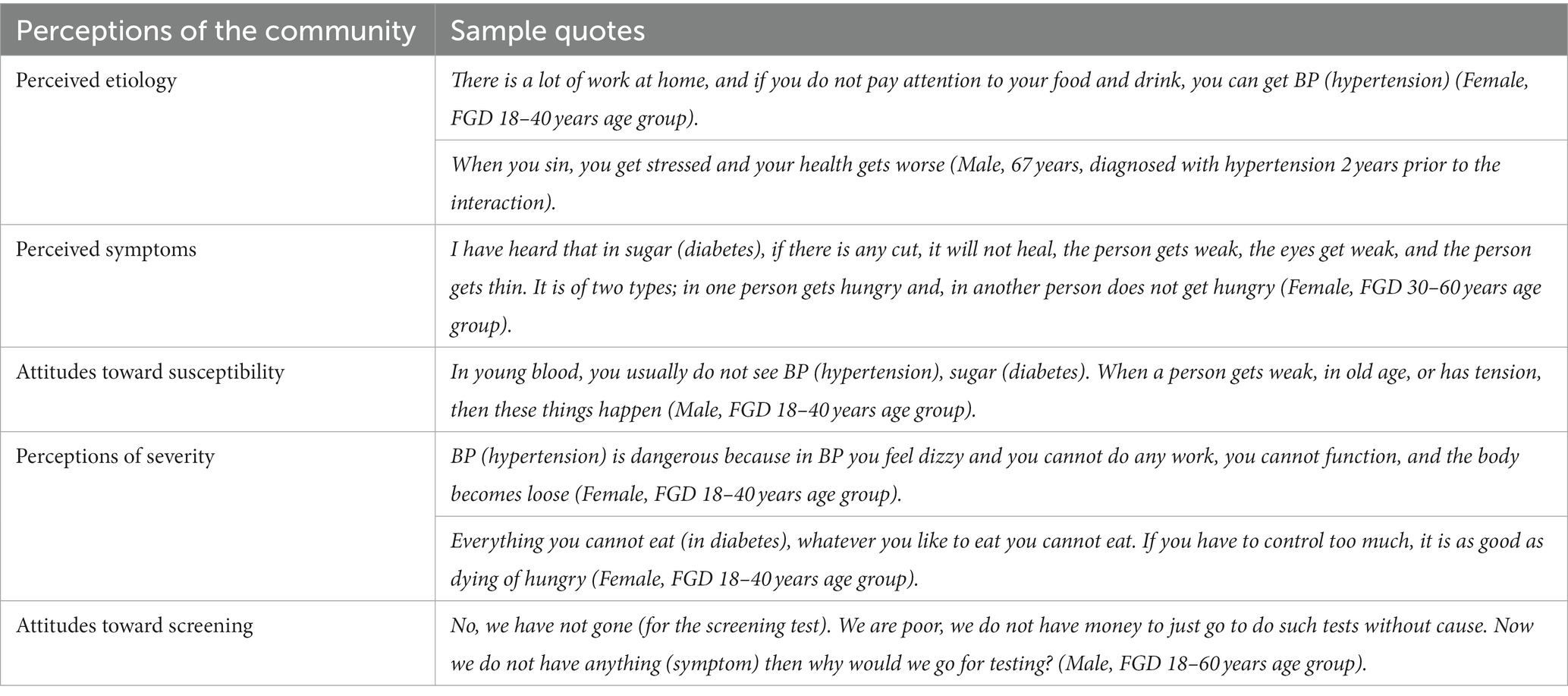

In our FGDs with the community, we found that people were generally aware of both diabetes and hypertension. Women seemed to know more details about testing for diabetes and hypertension than men due to the checkups done during pregnancy. We present below the perceptions of the community under four themes in brief—perceived etiology, perceived symptoms, attitudes toward susceptibility and perceptions of severity. Table 4 depicts illustrative quotes from each of the themes below.

Perceived etiology: Poor diet and stress were perceived as triggers of both diabetes and hypertension. Heredity and other lifestyle issues (lack of exercise, obesity) were not mentioned by participants as contributors. Religious beliefs also shaped perceptions of the causes and impact of the diseases.

Perceived symptoms: People shared that diabetes manifests as weakness in the body, aches and pains, wounds that do not heal, frequent urination and dizziness, and hypertension manifests as dizziness, anxiety, confusion and anger.

Attitudes toward susceptibility: Most people believed that the young are not susceptible. Old age and tension were seen as precipitators. Both men and women were seen as equally susceptible to diabetes and hypertension.

Perceptions of severity: There was consensus that both conditions were dangerous and disruptive to people’s lives in many ways. Patients particularly noted diet restrictions and the challenges in adhering to these restrictions if diagnosed with diabetes or hypertension.

3.5.2 Influence of lay perceptions on people’s care seeking journeys

The above perceptions of diabetes and hypertension influenced people’s care-seeking journeys in many ways. For one, these perceptions did not engender the need for preventive lifestyle changes or early screening. It was believed that stressful events caused the body to be weak and precipitated such ailments. Since stressful and emotional life events were perceived as beyond the control of participants, notions of preventing diabetes and hypertension were largely missing from people’s narratives. While patients recognized the dire consequences of the diseases, they felt the need to take action only if these disrupted daily routines and ability to work. Therefore, screening which involved precious costs in terms of time and money, was considered illogical in the absence of bothersome symptoms.

While people acknowledged the role of diet control as necessary in managing diabetes and hypertension after diagnosis, changing lifestyles and diets as preventive measures were not mentioned in the general community. Several patients/family members spoke of practicing diet restrictions, while others said it was challenging due to the lack of availability of healthy food where they worked. But we did not find any patients who emphasized the importance of exercise in managing these two NCDs. When we probed on this, two patients mentioned the lack of space near their houses to walk or exercise. Others regarded their daily work as adequate exercise. As one female participant in a community discussion told us, “We have so much work in the household, we are on our feet, bending-whether it is filling water or washing, that is our exercise.”

4 Discussion

We have structured our discussion in two sections. The first section discusses the study’s contribution to conceptual thinking on care-seeking for NCDs in LMICs. The second section summarizes the key policy implications of this study.

4.1 Care-seeking pathways for NCDs in LMICs

Figure 1 is our attempt to represent the diverse care-seeking pathways for NCD care encountered in our study in the form of a framework. Figure 1 depicts three cyclic components of the pathway: the initial care-seeking cycles (loop A), the diagnostic loops (loop B), and the disease-management loops (loop C). Loop A comprises the pursuit of symptomatic relief from “small” private doctors and local pharmacies. People usually exit this loop only when their symptoms worsen, making it challenging for them to carry on with routine activities. On exiting loop A, people enter the diagnostic loops (loop B). Here, people embrace, confirm, or reject diagnoses. Diagnosis is often not a single point in the patient journey but occurs repeatedly in a loop-like fashion. Intersecting with the diagnostic loops are the disease management loops (loop C). In loop C, people initiate, adjust, stop, or restart disease management. In both loops B and C, care is sought from a mix of healthcare providers.

Our framework attempts to add conceptual richness to current thinking on care-seeking pathways for NCDs. It acknowledges that care-seeking journeys for NCDs can be messy and cyclic in low-resource settings; and cannot be linearly portrayed in simplistic ways. While it includes the two touchpoints-diagnosis and treatment used in earlier studies (11, 43, 44), these get considered as cyclic occurrences (“loops”) in our framework rather than as sequential events. Further, the framework explicitly depicts “hopping” providers, a phenomenon that is of particular concern in LMICs.

It can be argued that cycles are a positive phenomenon in NCD care-seeking and that the occurrence of multiple diagnostic and disease management cycles signal “continuum of care” for these ailments (45, 46). But in our data, repeats in diagnosis or changes in the course of treatment, were typically not a part of meticulous “follow-up” by patients. Instead, these repeats were most often a response to previously disregarded diagnoses or poorly followed treatment advice.

Our study found that people’s care seeking pathways were characterized by numerous hops between diverse providers. The reasons that people reported in our study for hopping providers—such as costs, distances, quality of care, and patient satisfaction—echo findings from other informal settlements in India, Kenya, and other African contexts (47–49). But, in a broader sense, the sheer number of “hops” in almost every patient journey clearly signal constant dissatisfaction with the care that people received. The “hops” are indicative of the urgent need for trusted and reliable “first-contact” points for NCD care, as well as for the integration of care provided by different providers—two essential characteristics of good primary care (50).

The phenomenon of “hopping” providers in our study also explains why the bypass of primary care, an important issue of policy concern (51, 52), is challenging to comprehend in LMICs. Our data suggests that, with respect to care for NCDs, people do not “bypass” one provider in favor of another. Instead, they experiment with multiple options for care, sometimes even simultaneously, and continually search for options that balance the need for relief and the need to save on healthcare costs.

Our findings also point to delays in diagnosis and problems with treatment adherence. Diagnostic delays in our study had many causes, including the lack of providers who advised on necessary screening tests during the early stage of the disease and people’s resistance to believing the diagnosis. We felt that there were many missed opportunities for early detection, an issue of concern in other LMIC settings as well (16, 43, 53). With regard to adherence to treatment for hypertension and diabetes, our findings were consistent with those reported in other LMICs, and included both structural factors (cost of medicines and lack of continuity of care) and behavioral factors (lack of knowledge and unfavorable attitudes toward long-term treatments) (54–56). Similar to another study in urban India, we found that the lack of adherence to treatment regimens was intentional and did not stem from mere forgetfulness of patients (57). In summary, though patients gave a variety of explanations for issues in diagnosis and treatment, these issue stemmed from the absence of affordable and integrated healthcare in our study area.

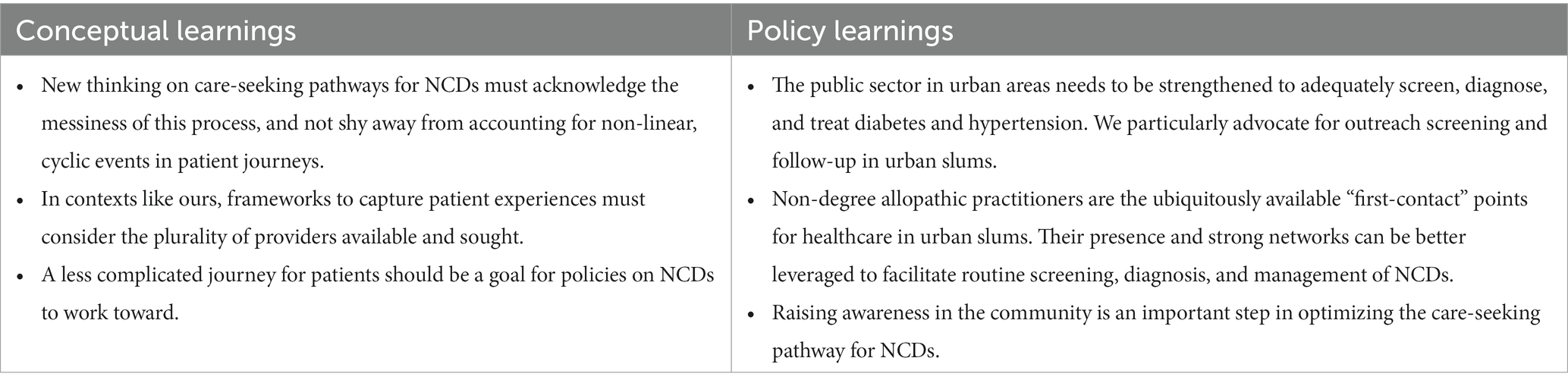

4.2 Policy implications

We have summarized the key learnings from this paper in Table 5. From our findings, we suggest below three ways in which NCD care for people living in urban informal settlements in India can be strengthened.

First, the urban public health sector needs to play a more active and integrated role in managing NCDs. Recent studies show that the public health sector in India is not being utilized adequately for the screening, treatment, and follow-up of NCDs (58, 59). One recent survey confirms that, despite recent policy efforts, the preparedness of India’s public primary and secondary care facilities to integrate care provision for NCDs is weak (60). Also, the public health system in most of India at present lacks the strong coordination and follow-up mechanisms needed to effectively treat chronic diseases (61, 62). While the integration of NCDs into primary care has begun in many places in the country, more concerted action on this front is needed, particularly in urban areas.

Second, the government-run NCD programs in the country’s urban areas can benefit from better engagement with the “small” doctors (NDAPs). The advantages of “small” doctors in delivering first-contact primary care, such as their intimate ties to the community, responsiveness to the needs felt by the community, and affordability, have been extensively discussed in literature (63, 64). Concerns have also been raised regarding the quality of care that “small” doctors offer (65). Despite these concerns, small providers have been leveraged by the National Tuberculosis Control Program (66) and recently during the COVID-19 pandemic (67) to strengthen service delivery. In terms of NCDs, the role of these doctors has so far been limited. Since these doctors are often the first points of healthcare contact for the community, their non-involvement speaks to a missed opportunity for screening and early diagnosis of NCDs. Training this set of healthcare providers on NCD screening and diagnosis and leveraging their community networks to support the public sector in NCD care can go a long way in streamlining the care-seeking journey for people. Across LMICs, the plurality of providers in urban health systems is being increasingly recognized (68). While it is imperative to strengthen the urban public sector for NCD care, the role that the local private sector in such areas can play cannot be ignored.

Lastly, advice from neighbors and friends, as well as support from families, plays an important role in shaping people’s care-seeking journeys. We found that while the community was aware of diabetes and hypertension as diseases, there was a paucity of knowledge about how the diseases were linked to lifestyle and heredity. Notions of “prevention” and “screening” for NCDs were entirely missing from community narratives. Raising awareness in the community is an important first step to optimizing the care-seeking pathway for NCDs. For doing so, “educational” interventions such as group communication, individual counseling, and mass awareness campaigns—including interventions led by community health workers and lay facilitators—have been suggested (69). Experiences from LMICs also tout patient “support” groups as a valuable strategy for empowering patients, improving long-term adherence to medicines, and spreading awareness about NCDs (70, 71).

While this study offers fresh perspectives by analyzing patient care seeking journeys for non-communicable diseases in urban informal settlements, it has some limitations. One limitation arises from gathering information through memory recall. Some patients could remember only key events in their care-seeking journeys, such as the treatment during worsening symptoms or catastrophic health events. Many could not remember dates and concrete timelines. Often, patients did not relate several “every day” symptoms to their disease, providing little information about their journeys before diagnosis or about simultaneous journeys related to other diseases. We tried our best to deal with recall bias and specifically probe and clarify events. While we tried our best to diversify the participants involved in our study, we could not completely eliminate selection bias. Since the patients were sampled through SNEHA’s existing maternal and child health program in the community, the selection of participants included only those with families living in the informal settlements. We also did not have access to recently migrated male workers who were single and living in this area, and we acknowledge that their care-seeking journeys could have been different.

4.3 Conclusion

This study found that care-seeking for NCDs in urban informal settlements was convoluted, with patients hopping from one provider to another. People in our study area reported experimenting with three healthcare options—the local private sector comprising of “small” doctors, the formal allopathic private sector, and the public sector. The first option—the “small” doctors were regarded by the community as both affordable and accessible; however, these doctors could not always diagnose and treat NCDs. The second option—the formal private sector, comprising providers trained in allopathic medicine, was regarded by this population as both costly and unfamiliar. The third option—the urban public health sector was often considered as being difficult to access, inadequate in terms of coverage, and non-sympathetic to people’s felt needs. Thus, none of the three healthcare options seemed to meet the NCD care needs of people living in the urban informal settlements we studied.

Empirical studies of care-seeking journeys like ours can serve as important tools for policies to understand people’s needs and expectations. The findings of this study suggest that there is an urgent need for trusted “first-contact” points for NCD care and for integrating care across healthcare providers in urban informal settlements. Raising awareness in the community is also an important step in optimizing the care-seeking pathway for NCDs. Urban health policies should strive to make journeys less challenging for patients, rather than assuming that care-seeking events linearly unfold from awareness to diagnosis and treatment.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SR: Conceptualization, Supervision, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. MB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Project administration. JS: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Methodology. SwP: Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. SS: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. ShP: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Validation. VD’S: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AJ: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Validation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded through the Epic Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors express our gratitude to all the individuals who participated in this study, as their valuable perspectives and experiences made it possible. We extend our appreciation to the entire team involved in SNEHA’s maternal health program for their contributions. We acknowledge the field support provided by Clipsy Banji, Sujata Tambe, and Kalyani Upadhayay. Lastly, we would like to thank the members of the SNEHA Research Group for their valuable feedback.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1257226/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Mohan, D, Ranjit Mohan, A, Datta, M, Venkat, N, and Viswanathan, M. Convergence of prevalence rates of diabetes and Cardiometabolic risk factors in middle and low income groups in urban India: 10-year follow-up of the Chennai urban population study. J Diabetes Sci Technol. (2011) 5:918–27. doi: 10.1177/193229681100500415

2. Ayah, R, Joshi, MD, Wanjiru, R, Njau, EK, Otieno, CF, Njeru, EK, et al. A population-based survey of prevalence of diabetes and correlates in an urban slum community in Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:371. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-371

3. Snyder, RE, Rajan, JV, Costa, F, Lima, HCAV, Calcagno, JI, Couto, RD, et al. Differences in the prevalence of non-communicable diseases between slum dwellers and the general population in a large urban area in Brazil. Tropic Med Infect Dis. (2017) 2:47. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed2030047

4. Rawal, LB, Biswas, T, Khandker, NN, Saha, SR, Bidat Chowdhury, MM, Khan, ANS, et al. Non-communicable disease (NCD) risk factors and diabetes among adults living in slum areas of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Islam FMA, editor. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0184967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184967

5. Joshi, MD, Ayah, R, Njau, EK, Wanjiru, R, Kayima, JK, Njeru, EK, et al. Prevalence of hypertension and associated cardiovascular risk factors in an urban slum in Nairobi, Kenya: a population-based survey. BMC Public Health. (2014) 14:1177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1177

6. Lumagbas, LB, Coleman, HLS, Bunders, J, Pariente, A, Belonje, A, and de Cock, BT. Non-communicable diseases in Indian slums: re-framing the social determinants of health. Glob Health Action. (2018) 11:1438840. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2018.1438840

7. de Siqueira Filha, NT, Li, J, Phillips-Howard, PA, Quayyum, Z, Kibuchi, E, Mithu, MIH, et al. The economics of healthcare access: a scoping review on the economic impact of healthcare access for vulnerable urban populations in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Equity Health. (2022) 21:191. doi: 10.1186/s12939-022-01804-3

8. Bhojani, U, Mishra, A, Amruthavalli, S, Devadasan, N, Kolsteren, P, De Henauw, S, et al. Constraints faced by urban poor in managing diabetes care: patients’ perspectives from South India. Glob Health Action. (2013) 6:22258. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.22258

9. Ezeh, A, Oyebode, O, Satterthwaite, D, Chen, YF, Ndugwa, R, Sartori, J, et al. The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. Lancet. (2017) 389:547–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31650-6

10. de Snyder, VNS, Friel, S, Fotso, JC, Khadr, Z, Meresman, S, Monge, P, et al. Social conditions and urban health inequities: realities, challenges and opportunities to transform the urban landscape through research and action. J Urban Health. (2011) 88:1183–93. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9609-y

11. Devi, R, Kanitkar, K, Narendhar, R, Sehmi, K, and Subramaniam, K. A narrative review of the patient journey through the Lens of non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries. Adv Ther. (2020) 37:4808–30. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01519-3

12. Kane, S, Joshi, M, Desai, S, Mahal, A, and McPake, B. People’s care seeking journey for a chronic illness in rural India: implications for policy and practice. Soc Sci Med. (2022) 312:115390. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115390

13. Patient journey mapping . Experience 360. (n.d.). Available at: https://experience360.com.au/patient-journey-mapping/#:~:text=The%20backbone%20of%20patient%20centred%20care%20is%20a (Accessed November 20, 2023).

14. Richter, P, and Schlieter, H. Understanding patient pathways in the context of integrated health care services—implications from a scoping review. Wirtschaftsinformatik 2019 Proceedings. (2019); Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/wi2019/track08/papers/6/

15. Keshri, VR, Abimbola, S, Parveen, S, Mishra, B, Roy, MP, Jain, T, et al. Navigating health systems for burn care: patient journeys and delays in Uttar Pradesh, India. Burns. (2023) 49:1745–55. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2023.03.009

16. Mendoza, JA, Lasco, G, Renedo, A, Palileo-Villanueva, L, Seguin, M, Palafox, B, et al. (De)constructing “therapeutic itineraries” of hypertension care: a qualitative study in the Philippines. Soc Sci Med. (2021) 300:114570. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114570

17. Ly, S, Runacres, F, and Poon, P. Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:915. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06934-y

18. World Health Organization . Intention to action series: people power. Perspectives from individuals with lived experience of noncommunicable diseases, mental health conditions and neurological conditions. (2023). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240069725

19. Uthman, OA, Ayorinde, A, Oyebode, O, Sartori, J, Gill, P, and Lilford, RJ. Global prevalence and trends in hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus among slum residents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e052393. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052393

20. Banerjee, S, Mukherjee, TK, and Basu, S. Prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension in the slums of Kolkata. Indian Heart J. (2016) 68:286–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2015.09.029

21. Chary, AN, Nandi, M, Flood, D, Tschida, S, Wilcox, K, Kurschner, S, et al. Qualitative study of pathways to care among adults with diabetes in rural Guatemala. BMJ Open. (2023) 13:e056913. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056913

22. Indian Council of Medical Research, Public Health Foundation of India, and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . India: health of the Nation’s states – the India state-level disease burden initiative. New Delhi, India: ICMR, PHFI, and IHME;(2017). Available at: https://phfi.org/india-health-of-the-nations-states/

23. Anjana, RM, Unnikrishnan, R, Deepa, M, Pradeepa, R, Tandon, N, Das, AK, et al. Metabolic non-communicable disease health report of India: the ICMR-INDIAB national cross-sectional study (ICMR-INDIAB-17). Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2023) 11:474–89. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(23)00119-5

24. Wilson, V, and Nittoori, S. Risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus among urban slum population using Indian diabetes risk score. Indian J Med Res. (2020) 152:308–11. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1597_18

25. Mishra, A, Rao Seshadri, S, Pradyumna, A, Pinto, PE, Bhattacharya, A, and Saligram, P. Health care equity in urban India. (2021). Available at: http://publications.azimpremjifoundation.org/3038/1/Health%20Care%20Equity%20in%20Urban%20India_Arima.pdf

26. Kumar, S, Sharma, A, Sood, A, and Kumar, S. Urban health in India. J Health Manag. (2016) 18:489–98. doi: 10.1177/0972063416651608

27. Gupta, I, and Mondal, S. Urban health in India: who is responsible? Int J Health Plann Manag. (2014) 30:192–203. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2236

28. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India . National Health Policy 2017. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (2017).

29. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India . Operational guidelines National Programme for prevention and control of non-communicable diseases (2023). Available at: https://app.clinally.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Revised_Operational_Guidelines_of_NP_NCD_2023_2030__1684379790-1.pdf.

30. Bhojani, U, Devedasan, N, Mishra, A, De Henauw, S, Kolsteren, P, and Criel, B. Health system challenges in organizing quality diabetes Care for Urban Poor in South India. PLoS One. (2014) 9:e106522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106522

31. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India . National Health Accounts Estimates for India (2019-20). National Health Systems Resource Centre. (2023). Available at: https://nhsrcindia.org/national-health-accounts-records

32. Gautham, M, Binnendijk, E, Koren, R, and Dror, DM. “First we go to the small doctor”: first contact for curative health care sought by rural communities in Andhra Pradesh & Orissa, India. Indian J Med Res. (2011) 134:627–38. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.90987

33. Prasad, B, Tripathy, J, Thekkur, P, and Muraleedharan, V. Insights from national survey on household expenditure for primary healthcare services availed through informal healthcare providers. J Fam Med Prim Care. (2021) 10:1912. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2274_20

34. May, C, Roth, K, and Panda, P. Non-degree allopathic practitioners as first contact points for acute illness episodes: insights from a qualitative study in rural northern India. BMC Health Serv Res. (2014) 14:182. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-182

35. Abdul Azeez, EP, Selvi, GA, Sharma, G, and Senthil Kumar, AP. What attracts and sustain urban poor to informal healthcare practitioners? A study on practitioners’ perspectives and patients’ experiences in an Indian city. Int J Health Plann Manag. (2020) 36:83–99. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3068

36. Population Census Maharashtra. (2011) Available at: https://www.census2011.co.in/

37. Patton, MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications (2002).

38. Miles, MB, and Huberman, AM. Qualitative data analysis an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications (1994).

39. Seale, C. Quality in qualitative research. Qual Inq. (1999) 5:465–78. doi: 10.4135/9780857020093

40. Ritchie, J, Lewis, J, McNaughton Nicholls, C, and Ormston, R. Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Los Angeles, California: Sage Publications (2014).

41. Yellappa, V, Lefèvre, P, Battaglioli, T, Devadasan, N, and Van der Stuyft, P. Patients pathways to tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment in a fragmented health system: a qualitative study from a south Indian district. BMC Public Health. (2017) 17:635. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4627-7

42. Kapoor, SK, Raman, AV, Sachdeva, KS, and Satyanarayana, S. How did the TB patients reach DOTS Services in Delhi? A study of patient treatment seeking behavior. PLoS One. (2012) 7:e42458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042458

43. Kasujja, FX, Nuwaha, F, Daivadanam, M, Kiguli, J, Etajak, S, and Mayega, RW. Understanding the diagnostic delays and pathways for diabetes in eastern Uganda: a qualitative study. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0250421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250421

44. Gabert, R, Ng, M, Sogarwal, R, Bryant, M, Deepu, RV, McNellan, CR, et al. Identifying gaps in the continuum of care for hypertension and diabetes in two Indian communities. BMC Health Serv Res. (2017) 17:846. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2796-9

45. Jayanna, K, Swaroop, N, Kar, A, Ramanaik, S, Pati, MK, Pujar, A, et al. Designing a comprehensive non-communicable diseases (NCD) programme for hypertension and diabetes at primary health care level: evidence and experience from urban Karnataka, South India. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:409. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6735-z

46. Selvaraj, S, Karan, K, Srivastava, S, Bhan, N, and Mukhopadhyay, I. India: health system review. Health Systems in Transition. World Health Organization. Regional office for south-East Asia. (2022);11. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/352685

47. Prince, RJ. Malignant stories: the chronicity of cancer and the pursuit of care in Kenya. Vaughan M, Adjaye-Gbewonyo K, Mika M, editors. JSTOR UCL Press; (2021). p. 322–349. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv14t4769.18

48. Pakhare, A, Nimesh, V, Halder, A, Mitra, A, Kumar, S, Joshi, A, et al. Patterns of healthcare seeking behavior among persons with diabetes in Central India: a mixed method study. J Fam Med Prim Care. (2019) 8:677–83. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_433_18

49. Conlan, C, Cunningham, T, Watson, S, Madan, J, Sfyridis, A, Sartori, J, et al. Perceived quality of care and choice of healthcare provider in informal settlements. PLOS Glob Public Health. (2023) 3:e0001281–1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0001281

50. Starfield, B, Shi, L, and Macinko, J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. (2005) 83:457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

51. Gauthier, B, and Wane, W. Bypassing health providers: the quest for better price and quality of health care in Chad. Soc Sci Med. (2011) 73:540–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.008

52. Bell, G, Macarayan, EK, Ratcliffe, H, Kim, JH, Otupiri, E, Lipsitz, S, et al. Assessment of bypass of the nearest primary health care facility among women in Ghana. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2012552. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12552

53. Kabir, A, Karim, MN, and Billah, B. Health system challenges and opportunities in organizing non-communicable diseases services delivery at primary healthcare level in Bangladesh: a qualitative study. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:5245. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1015245

54. Chauke, GD, Nakwafila, O, Chibi, B, Sartorius, B, and Mashamba-Thompson, T. Factors influencing poor medication adherence amongst patients with chronic disease in low-and-middle-income countries: a systematic scoping review. Heliyon. (2022) 8:e09716. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09716

55. Baghcheghi, N, and Koohestani, HR. Beliefs about medicines and its relationship with medication adherence in patients with chronic diseases. Qom Univ Med Sci J. (2021) 15:444–53. doi: 10.32598/qums.15.6.2414.1

56. Atinga, RA, Yarney, L, and Gavu, NM. Factors influencing long-term medication non-adherence among diabetes and hypertensive patients in Ghana: a qualitative investigation. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0193995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193995

57. Lakshmi, N, Algotar, P, and Bhagyalaxmi, A. A community based study on medication adherence and its determinants among people with non communicable diseases in Ahmedabad. Int J Multidiscip Res Dev. (2019) 6:01–4.

58. Bhor, N. Care-seeking practices for non-communicable chronic conditions in a low-income neighborhood in southern India. PLOS Glob Public Health. (2023) 3:e0002074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002074

59. Lall, D, Engel, N, Devadasan, N, Horstman, K, and Criel, B. Challenges in primary care for diabetes and hypertension: an observational study of the Kolar district in rural India. BMC Health Serv Res. (2019) 19:44. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-3876-9

60. Krishnan, A, Mathur, P, Kulothungan, V, Salve, HR, Leburu, S, Amarchand, R, et al. Preparedness of primary and secondary health facilities in India to address major non-communicable diseases: results of a National non-communicable Disease Monitoring Survey (NNMS). BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:757. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06530-0

61. Pati, MK, Swaroop, N, Kar, A, Aggarwal, P, Jayanna, K, and Van Damme, W. A narrative review of gaps in the provision of integrated care for non-communicable diseases in India. Public Health Rev. (2020) 41:8. doi: 10.1186/s40985-020-00128-3

62. Lall, D, Engel, N, Devadasan, N, Horstman, K, and Criel, B. Team-based primary health care for non-communicable diseases: complexities in South India. Health Policy Plan. (2020) 35:ii22–34. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa121

63. Gautham, M, Shyamprasad, KM, Singh, R, Zachariah, A, Singh, R, and Bloom, G. Informal rural healthcare providers in north and South India. Health Policy Plan. (2014) 29:i20–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt050

64. George, A, and Iyer, A. Unfree markets: socially embedded informal health providers in northern Karnataka, India. Soc Sci Med. (2013) 96:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.022

65. Cross, J, and MacGregor, HN. Knowledge, legitimacy and economic practice in informal markets for medicine: a critical review of research. Soc Sci Med. (2010) 71:1593–600. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.040

66. Thapa, P, Jayasuriya, R, Hall, JJ, Beek, K, Mukherjee, P, Gudi, N, et al. Role of informal healthcare providers in tuberculosis care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic scoping review. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0256795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256795

67. Meghani, A, Hariyani, S, Das, P, and Bennett, S. Public sector engagement of private healthcare providers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Uttar Pradesh, India. PLOS Glob Public Health. (2022) 2:e0000750. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000750

68. Elsey, H, Agyepong, I, Huque, R, Quayyem, Z, Baral, S, Ebenso, B, et al. Rethinking health systems in the context of urbanization: challenges from four rapidly urbanizing low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. (2019) 4:e001501. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001501

69. Correia, JC, Lachat, S, Lagger, G, Chappuis, F, Golay, A, and Beran, D. Interventions targeting hypertension and diabetes mellitus at community and primary healthcare level in low- and middle-income countries:a scoping review. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:1542. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7842-6

70. Pastakia, SD, Manyara, SM, Vedanthan, R, Kamano, JH, Menya, D, Andama, B, et al. Impact of bridging income generation with group integrated care (BIGPIC) on hypertension and diabetes in rural Western Kenya. J Gen Intern Med. (2016) 32:540–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3918-5

Keywords: non-communicable diseases, patient journeys, care-seeking pathways, primary health care, diabetes, hypertension, urban slums, informal settlements

Citation: Ramani S, Bahuguna M, Spencer J, Pathak S, Shende S, Pantvaidya S, D’Souza V and Jayaraman A (2024) Many hops, many stops: care-seeking “loops” for diabetes and hypertension in three urban informal settlements in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. Front. Public Health. 11:1257226. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1257226

Edited by:

Nicolai Savaskan, District Office Neukölln of Berlin Neukölln, GermanyReviewed by:

Peter Delobelle, University of Cape Town, South AfricaSuresh Munuswamy, Public Health Foundation of India, India

Copyright © 2024 Ramani, Bahuguna, Spencer, Pathak, Shende, Pantvaidya, D’Souza and Jayaraman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anuja Jayaraman, YW51amFAc25laGFtdW1iYWkub3Jn

Sudha Ramani

Sudha Ramani Manjula Bahuguna

Manjula Bahuguna Anuja Jayaraman

Anuja Jayaraman