1 Introduction

Since its inception, Israel has provided universal public health care for all its citizens via four not-for-profit health maintenance organizations (HMOs). Definitions of public health abound, including the organized response by society to protect and promote health, to prevent injury, illness, and disability, and to “provide the necessary conditions for a population to be healthy (1). Universal or national health systems view the right to health as a human right (2). Based on that view, the Israel National Health Insurance Law (3) made health insurance mandatory, stipulating that every resident, irrespective of age, religion, ethnicity, or socio-economic status, is entitled to an exceptionally broad basket of health services (4). The implementation of the law has indeed increased equality though inequalities still exist (5–9). Most of the inequality in health policies and services relates to religious minorities such as the Ultra-Orthodox Jews and Muslim Arabs (10, 11).

The inequality in a universal system is a major concern of policy makers and health authorities who make continuous efforts to reduce inequalities and shape culturally sensitive policies for planning and delivery of care (4, 8, 12, 13). Sensitive policies include social participation of all members of society, which albeit being a complex undertaking in practice, is acknowledged by the WHO as an important means for policymakers to develop responsive health policies with a higher likelihood of being implemented (14). A universal health system, by definition, needs to ensure the right to equitable physical and mental health so that rights are not infringed, and policies don't negatively weigh outcomes on both marginalized groups and society (2). Inequity in the Israeli universal system due to cultural differences has been studied (4, 15, 16). Research on policies and inequalities during COVID-19 and their effect on wellbeing, however, remains remarkably absent (17). The pandemic generated an opportunity to explore inequity underlying health policies that were applied to the health crisis as a response by policymakers and authorities. The pandemic warrants an exploration of the policies as means of reducing inequities by inclusiveness (16, 17).

The concept of inclusive health focuses on good health and well-being for everyone. This concept resonates with a rights-based approach to health including political, social, economic, scientific, and cultural actions that are geared toward advancing good health and well-being for all (18). This study seeks to enhance the understanding of the linkage between health policies during a health crisis, inclusiveness, and inequities, using COVID-19 policies in Israel as a case example. The topic of this study falls within the second group of the basic framework for One Health research which is captured in The World 2050 Initiative (TWI) (19). This author argues for the need to form inclusive health responses, not only in routine but also during public health emergencies for public health promotion. Insights from this study may inform policy makers and health authorities of universal systems and direct interventions for reducing inequities and ensuring inclusiveness.

1.1 Religious minorities in Israel

There are seven religious minorities in Israel comprising 37.5% of the population. In Israel, the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community, and the Arab population (Muslim and Christian) are the most prominent and well-defined minority groups (20, 21). According to the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics 2018, there are three population groups: Jews, who constitute 75% of the population; Arab Israelis, who account for 21% of the population, and others, 4% of the population which include non-Arab Christians, Buddhists, Hindus, Samaritans, and Bahá'ís. In 2015, the Arab Israeli population reached 1.8 M and is comprised of 84% Muslims, 8% Druze, and 8% Christians. Bedouins account for 16% of the Muslim population (22). These religious minorities are collectivist, and the identity of the group transcends that of the individual (23). The ultra-Orthodox and Muslim minorities have large families, live in close-knit communities, have death rituals that distinguish them from other marginalized groups, have a complicated relationship with the government and their behavior is guided by their spiritual leaders (24).

1.2 Religious minorities in Israel during COVID

Compliance with physical distancing across religious minorities has been shown to be relatively poorer compared to the majority group (23, 25, 26). The Jewish ultra-Orthodox minority comprises 12.6 of the population but 40–60% of all coronavirus patients were Jewish ultra-Orthodox; similarly, the Arab population comprises 21% of the population but 33% of all coronavirus patients were Arab (27). The social representation theory stresses the need to design culturally adapted messages to reflect the shared reality of each marginalized group (28). Throughout COVID-19, however, although risk perception has cultural roots, messages calling for physical distancing were not culturally adapted, leading to poor compliance with guidelines (29, 30).

1.3 Health policies during the pandemic and inclusiveness in Israel

The COVID-19 pandemic, a public health emergency, affected many countries worldwide and necessitated measures to contain the virus. Like other countries, Israel implemented measures of preservation of hygiene, mandatory mask wearing, and maintaining physical distancing (27, 31, 32). Physical distancing refers to maintaining physical separation to reduce close contact between people (33). Practices of physical distancing included self-isolation, quarantine, preventing assemblies of people in community settings, and closures of schools, gyms, bars, and restaurants (34, 35). Physical distancing remained the primary intervention throughout the five waves of the pandemic (36, 37). Health authorities invested efforts to implement the physical distancing policy by education, persuasion, legislation, incentives, and coercion, which offended members of certain religious minorities (33, 38). These measures to contain the virus prevented communal traditions, including religious practices, death rituals, and funerals (34, 35). Coercion infringed human rights, and lead to higher stress, distress, family conflicts, and loneliness (39).

Although collective religious practices foster connectedness and resilience, there were no platforms to foster spirituality throughout the adversity faced by minorities (40–42). Furthermore, minority members claimed that activities in synagogues and mosques, which are critical for spirituality, for social support of bereaved, for family conflict resolution, for marriages, divorces, funerals, and for individual counseling, were banned under the guidelines, without any discussion with spiritual leaders about safe alternatives that had been applied in previous pandemics (41). Other public places (i.e., parks, bars) were allowed, from the third wave of the pandemic, to open whereas places of worship remained closed, leading to disappointment and anger at health authorities and the disengagement of minority members and their leadership from the fight against COVID-19.

Due to their poor compliance with guidelines, members of religious minorities, who had to cope with linguistic, employment-related, and socioeconomic challenges, became more vulnerable as it was harder for them to understand and apply public health measures (43). Members of religious minorities faced heightened discrimination by the majority group (23). The involvement of the police to enforce the health guidelines created fear and a sense of humiliation (41). Reports in the mass media depicted members of religious minorities as lacking respect for the physical distancing measures and jeopardizing public health (44).

Media reports kept exposing the lack of compliance of the Jewish ultra-Orthodox population with the law mandating hospitalization in public hospitals in cases of severe COVID-19. To avoid having their followers die in solitude, in overflowing, understaffed hospitals, the leadership of the ultra-Orthodox established underground hospitals which were an innovative implementation of patient-centered care in a health crisis (45). Several months later, the health authorities themselves adapted the policy enabling hospitalization in the community of patients with moderate COVID-19.

Moreover, the disempowerment of the religious minority spiritual leaders responsible for the sustainability of their communities during the five waves of the pandemic caused a breach of trust between these communities and the health authorities and inhibited the support of religious leaders for public health measures (41). COVID-19 guidelines inhibited the practice of death rituals and created multi-level clashes between values and beliefs and guidelines, inhibiting effective processing of grief and effective functioning following loss. Muslims, in particular, experienced disenfranchised grief at the individual and community levels, jeopardizing wellbeing and leading to distrust of authorities and policymakers, deeper polarization in the society, lower utilization of health services, poor mental health, and worsening of chronic illnesses (41).

1.4 Actions of health authorities

Core activities of public health include community education, outbreak investigation and communicable disease control, risk factor and disease surveillance, screening, development and implementation of public health interventions, evaluation, and research. Since the 1970s, public health has been emphasizing the partnership approach, which aims at community engagement, health promotion, and inter-sectoral partnerships (1). The partnership and collaboration approach throughout COVID-19 in Israel, however, was deficient.

Health authorities and policy makers were perceived by members and leaders of religious minorities as failing to recognize the loss of community; as devaluing the spiritual leaders of religious minorities who are responsible for the continuation of community and excluding them from decision making; as unaware of potential adaptations to religious values and beliefs that were possible in previous pandemics; failing to provide resources to help community members plan for practical needs after death; failing to improve wellbeing and resilience through grief counseling and self-care for elders during this challenging time; failing to create and make accessible communication platforms that alleviate anxiety and process collective loss in order to restore social identity (24, 41, 41, 45, 46). These experiences resulted in distrust, disappointment, and anger at health authorities, rejection of the vaccine, poor compliance with guidelines, ineffective grief, deeper polarization from the majority population, and poor utilization of health services.

2 Discussion

This study explored the inclusiveness of health policies during the pandemic in the Israeli universal health system. The pandemic revealed weaknesses and blind spots in responding to it as a universal health system should. Although reducing inequities by community engagement has been promoted as a key element of epidemic responses, a collaborative approach with minority leaders was found to be lacking (24, 41, 46–48). Responses to the pandemic exacerbated inequalities that already existed; marginalized underrepresented groups were reported to be left behind and discriminated against partly due to COVID-19 policy responses (2, 24, 41). Highlighting the system's blind spots, the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how important it is to ensure an inclusive health approach to health emergencies.

Inclusive responses to public health emergencies are a tenet of public universal health systems (18). Since it was important to balance risks to public safety the insensitivity toward minorities, may have been understandable through the second wave, but from the third wave onward, authorities could have engaged in ongoing negotiations with leaders of religious minorities as the crisis evolved. Lack of inclusion was detrimental to achieving a commitment from minority populations to respect the control measures advocated by public health authorities (49). As in other countries, health authorities in Israel may have underestimated the capacity of the leadership and of members of these religious minorities to become active in designing the response to the pandemic (50). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, health responses failed to be empowering and to enhance wellbeing. Voices of minorities were excluded from social discourse and thereby from policy making. Although a public universal system is expected to attend and serve all citizens, this author demonstrated that religious minorities experienced non-inclusive public health responses throughout COVID-19 (2, 24, 41, 44).

Failing to recognize and address the needs of every marginalized group in the population based on the right to health led to distrust and translated into less compliance, as was demonstrated in Israel by 12% rejection of the first two vaccines, mostly by members of marginalized groups and by 48% rejection of the subsequent boosters (44, 50). If leaders of a marginalized group are excluded from decision making on policy and guidelines, the efficacy of a pandemic response may be severely undermined (49, 51). Exclusionary policies may have a long-term effect on utilization of health services long after the pandemic by neglecting alternative understandings that challenge dominant constructions of health and healthcare (40). Such neglect weakens the capacity of participatory action to promote transformative change through dialogical orientation (51, 52). Moreover, it may produce or exacerbate health inequities, as policies and services become increasingly adapted to the demands of vocal majorities (23).

Participation of leaders of marginalized groups in decision-making foster culturally adapted policies which make more responsive policies, and, consequently, healthier populations (53). Initiatives that focus on community empowerment are increasingly prominent in public health policy. However, while participation and inclusion are necessary conditions for empowerment, attention to the breadth of inclusion and to the extent to which it is experienced as empowering was insufficient (54). Several recommendations are proposed to promote inclusiveness in responses of universal systems to a health crisis.

2.1 Practice implications for policy makers and health authorities

Health authorities have a role in promoting the substantive inclusion of marginalized groups in healthcare decision-making (51). Health authorities must be strategic and proactive in reaching out to specific groups, to identify and address their needs, to disseminate transparent and accurate public health information, and shape actionable options to enhance public trust in health authorities and policymakers (49). Actively listening to leaders of religious minorities can facilitate collaborations with the communities which will reduce tensions through the process of reclaiming trust in authorities and policy makers. A collaborative approach may lead to open conversations that elucidate the challenges that religious minorities experience and the effects on equity and public health principles, especially in universal health systems.

There are implications for policy makers and authorities at three levels: Leadership, community levels, and collaborators. At the leadership level, to establish trust of leaders and their communities, in authorities, health authorities must validate the leadership of minorities by approaching it, initiating dialogues, providing transparent empirical data, and understanding disparities in approach and objections. Authorities and policymakers should avoid top-down imposition of solutions using a one-size-fits-all model (55). At the community level, authorities are called upon to understand the sources of objection and distrust and use culturally appropriate channels to communicate. Regarding collaborators, this author proposes to engage clinicians from religious minorities and collaborate with them to initiate community-based efforts to understand their needs, concerns, and possible solutions.

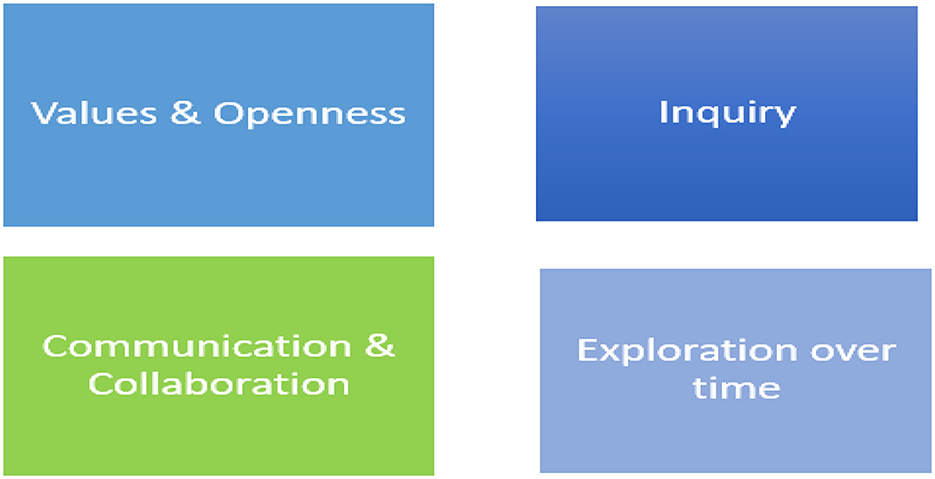

To succeed in promoting inclusiveness, authorities, and policy makers should apply the VOICE model in several steps. First explore their Values regarding inclusiveness in universal health systems. Second, be Open: the knowledge does not lie only with policymakers. Reflect and ask what we learned during COVID-19. Although there is a universal health system that aspires to eliminate inequities, state policies in practice reduced inclusiveness and enhanced perceived and actual inequities between the majority population and religious minorities. Third, Inquire about needs, concerns, objections of minorities. Fourth, Communicate and Collaborate to develop possible culturally adapted alternatives to the policies to preserve public health on the one hand and to respond in a way that includes religious minorities, on the other. Fifth, Explore alternatives over time. Figure 1 presents the VOICE model.

Looking forward, health authorities may intervene to ensure inclusiveness in health services for all members of society. Ensuring inclusive health responses is important in addressing health inequities in the short and long term (56). This author proposes six interventions to foster inclusiveness: (a) Create future inclusiveness through leadership education making sure that the health authority boards that make policy decisions reflect the diversity of the population. (b) Train the next generations of leaders by inclusive communication, public engagement, involved networks, as well as recruiting agents from each minority and setting up advisory groups. With time these measures will help the leaders of religious minorities to gain influence on shaping policies and help reclaim trust in policy makers health authorities. (c) Employ measures to prevent the infringement of civil rights of minorities and assess it as an important measure for health quality (d) Reward practices of inclusiveness to direct conduct toward this goal. (e) Critically appraise practice by evaluating and measuring trust, polarization, and utilization of health services.

3 Conclusions

Inclusive, dynamic, multi-stakeholder, responses of health systems remain critical in the context of health emergencies. Responses of public health authorities and health systems are to be more strategic, proactive, and inclusive, reaching out to all minorities and addressing their specific needs, values, and beliefs. Such an inclusive health approach may foster solidarity and health equity, perhaps leading to more effective responses of religious minorities to public health interventions in both emergencies and routine. Shaping strategies to target diverse multi-stakeholders is a first step to engage everyone in society, reduce discrimination, health inequity, and health deterioration. A commitment to an inclusive system implies that activities and responses will be sensitive to all, so no minority is left behind. This maintains the commitment of health systems to be universal health systems, for everyone, including in emergencies. As the COVID-19 pandemic, an unprecedented humanitarian crisis, continues to threaten and impact public health systems around the world, disrupting the well-being of people, inclusiveness in public health universal systems, cannot only exist in declarations. Inclusiveness cannot be overlooked. Policies should link policymakers and public health authorities with members and leaders of religious minorities to better respond to the needs of all.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Weeramanthri TS, Bailie RS. Grand challenges in public health policy. Front Pub Health. (2015) 3:29. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00029

2. Adebisi YA, Lucero Prisno DE. Towards an inclusive health agenda: people who inject drugs and the COVID-19 response in Africa. Pub Health. (2020) 190:e7. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.10.017

3. Israel. National Health Insurance Law. Clause 3(d). Jerusalem: Israeli Book of Laws 5754. No. 1469 (1994).

4. Baum N, Kum Y, Shalit H, Tal M. Inequalities in a national health care system from the perspective of social workers in Israel. Qual Health Res. (2017) 27:855–65. doi: 10.1177/1049732316648668

5. Epstein L. The Existence of Inequalities in Health and Health Services in Israel. In:Y Blesher, L Epstein, , editors, Inequalities in Health in Israel. Ramat Gan: The Israel Medical Association (2008), 5–15.

6. Epstein L, Horev T. Inequality in Health and in Health Systems: Presentation of the Problem and Guidelines for Policy to Address it. Jerusalem: Taub Center for Research of Social Policy in Israel (2007).

7. Horev T. Decreasing Inequality in Health: Implementation of the International Experience in Israel. Jerusalem: Taub Center for Research of Social Policy in Israel (2008).

8. Kumar A, Colombo F, Abi-Aad G, Chi YL, Raleigh V, Klazinga N, et al. Reviews of Health Care Quality Israel. Paris: OECD (2012).

9. Wilf-Miron R, Shem-Tov O, Lewenhoff I, Porath A, Kokia E. A Health Plan's Focus on the Social Periphery: From Measurement to an Action Plan to Reduce Disparities and Increase Equity. In: Paper presented at the 7th Annual Conference of the Forum for the Study of Social Policy. Ramat-Gan, Israel (2010).

10. Bina R. Seeking help for postpartum depression in the Israeli Jewish Orthodox community: factors associated with use of professional and informal help. Women Health. (2014) 54:455–73. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.897675

11. Elnekave E, Gross R. The healthcare experiences of Arab Israeli women in a reformed healthcare system. Health Policy. (2004) 69:101–16. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2003.12.005

12. Averbuch E, Kaidar N, Horev T. Inequality in Health and Management Thereof. Jerusalem: The Ministry of Health, Health Economics and Insurance Division (2010).

13. Ochieng BM. Black African migrants: the barriers with accessing and utilizing health promotion services in the UK. Eur J Public Health. (2013) 23:265–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks063

14. World Health Organization. Voice, Agency, Empowerment - Handbook on Social Participation for Universal Health Coverage. Geneva: WHO (2021).

15. Goldblatt H, Cohen M, Azaiza F, Manassa R. Being within or being between? The cultural context of Arab women's experience of coping with breast cancer in Israel. Psycho-Oncol. (2013) 22:869–75. doi: 10.1002/pon.3078

16. Nan X, Iles IA, Yang B, Ma Z. Public health messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: lessons from communication science. Health Commun. (2022) 37:1–9. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2021.1994910

17. Yin XC, Pang M, Law MP, Guerra F, O'Sullivan T, Laxer RE, et al. Rising through the pandemic: a scoping review of quality improvement in public health during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Pub Health. (2022) 22:248. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12631-0

18. Maclachlan M, Khasnabis C, Mannan H. Inclusive health. Trop Med Int Health. (2012) 17:139–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02876.x

19. Laaser U, Bjegovic-Mikanovic V, Seifman R, Senkubuge F, Stamenkovic Z. Editorial: One health, environmental health, global health, and inclusive governance: What can we do? Front Pub Health. (2022) 10:932922. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.932922

20. Central Bureau of Statistics. Society in Israel. Report No. 10. Jerusalem: Central Bureau of Statistics (2018).

21. Chernichovsky D, Bisharat B, Bowers L, Brill A, Sharony C. The health of the Arab Israeli population. State Nation Rep. (2017) 325:8–20.

22. Saban M, Myers V, Wilf-Miron R. Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic—the role of leadership in the Arab ethnic minority in Israel. Int J Equity Health. (2020) 19:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01257-6

23. Gabay G, Gere A, Naamati-Schneider L, Moskowitz H, Tarabieh M. Improving compliance with physical distancing across religious cultures in Israel. Israel J Health Policy Res. (2021) 10:1–2. doi: 10.1186/s13584-021-00501-w

24. Gabay G, Tarabeih M. Underground COVID-19 home hospitals for Haredim: non-compliance or a culturally adapted alternative to public hospitalization? J Religion Health. (2021) 60:3434–53. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01407-2

25. Taragin-Zeller L, Rozenblum Y, Baram-Tsabari A. Public engagement with science among religious minorities: lessons from COVID-19. Sci Commun. (2020) 42:643–78. doi: 10.1177/1075547020962107

26. Waitzberg R, Davidovitch N, Leibner G, Penn N, Brammli-Greenberg S. Israel's response to the COVID-19 pandemic: tailoring measures for vulnerable cultural minority populations. Int J Equity Health. (2020) 19:71. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01191-7

27. Abouk R, Heydari B. The immediate effect of COVID-19 policies on social-distancing behavior in the United States. Public Health Rep. (2021) 136:245–52. doi: 10.1177/0033354920976575

28. Wagner W. Social representations and beyond: brute facts, symbolic coping and domesticated worlds. Cultural Psych. (1988) 4:297–329. doi: 10.1177/1354067X9800400302

29. Bourassa KJ, Sbarra DA, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Physical distancing as a health behavior: county-level movement in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with conventional health behaviors. Ann Behav Med. (2020) 8:548–56. doi: 10.1093/abm/kaaa049

30. Michie S, West R, Amlôt R, Rubin J. Slowing down the COVID-19 outbreak: changing behaviour by understanding it. BMJ. (2020) 2:1–14.

31. Atangana E, Atangana A. Facemasks simple but powerful weapons to protect against COVID-19 spread: can they have sides effects? Results Phys. (2020) 19:103425. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103425

32. Marroquín B, Vine V, Morgan R. Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: effects of stay-at-home policies, social distancing behavior and social resources. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 293:113419. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113419

33. Bonell C, Michie S, Reicher S, West R, Bear L, Yardley L, et al. Harnessing behavioural science in public health campaigns to maintain “social distancing” in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: key principles. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2020) 74:617–9. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214290

34. Courtemanche C, Garuccio J, Le A, Pinkston J, Yelowitz A. Strong social distancing measures in the United States reduced the COVID-19 growth rate. Health Aff. (2020) 39:1237–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00608

35. Cronin CJ, Evans WN. Private Precaution and Public Restrictions: What Drives Physical Distancing and Industry Foot Traffic in the COVID-19 Era? Report w27531. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research (2020).

36. Fadda M, Albanese E, Suggs LS. When a COVID-19 vaccine is ready, will we all be ready for it? Int J Public Health. (2020) 65:711–2. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01404-4

37. Weill JA, Stigler M, Deschenes O, Springborn MR. Physical distancing responses to COVID-19 emergency declarations strongly differentiated by income. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2020) 117:19658–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009412117

38. Canning D, Karra M, Dayalu R, Guo M, Bloom DE. The association between age, COVID-19 symptoms, and physical distancing behavior in the United States. medRxiv. (2020) 1–23. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.19.20065219

39. Laforest J, Roberge M, Maurice P. Response Rapide: COVID-19 et R'percussions Psychosociales. Quebec: Institut national de sant' publique du Qu'bec (2020).

40. Campbell H. The Distanced Church: Reflections on Doing Church Online. London: Digital Religion Publications (2020).

41. Gabay G, Tarabeih M. Death from COVID-19, Muslim death rituals and disenfranchised grief-a patient-centered care perspective. OMEGA. (2022). doi: 10.1177/00302228221095717

42. Sheikhi RA, Seyedin H, Qanizadeh G, Jahangiri K. Role of religious institutions in disaster risk management: a systematic review. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2021) 15:239–54. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2019.145

43. Cleveland J, Hanley J, Jaimes A, Wolofsky T. Impacts de la crise de la COVID-19 Surles ≪Communaut's Culturelles≫ montralaises-Enquite sur les Facteurs Socioculturels et Structurels Affectant les Groupes vuln'rables. Institut Universitaire Sherpa. (2020). Available at: https://sherpa-recherche.com/en/publication/impacts-de-la-crise-de-la-covid-19-surles-communautes-cultu~relles-montrealaises/ (accessed May 22, 2023).

44. Gabay G, Tarabieh M. Science and behavioral intentions among Israeli Jewish ultra-Orthodox males: death from COVID-19 or from the COVID-19 vaccine? A thematic study. Public Understand Sci. (2022) 31:410–27. doi: 10.1177/09636625211070500

45. Gabay G, Tarabeih M. Invalidating the leadership of Muslim spiritual leaders in death from COVID-and shaping the grief journey—a narrative inquiry. OMEGA. (2022) doi: 10.1177/00302228221137393

46. Gillespie AM, Obregon R, El Asawi R, Richey C, Manoncourt E, Joshi K, et al. Social mobilization and community engagement central to the ebola response in West Africa: lessons for future public health emergencies. Glob Health Sci Pract. (2016) 4:626–46. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00226

47. Wiginton JM, King EJ, Fuller AO. 'We can act different from what we used to': Findings from experiences of religious leader participants in an HIV-prevention intervention in Zambia. Glob Pub Health. (2019) 14:636–48. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2018.1524921

48. World Health Organization. COVID-19 Strategy Update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2020).

49. Wong AS, Kohler JC. Social capital and public health: responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Health. (2020) 16:88. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00615-x

50. El Enany N, Currie G, Lockett A. A paradox in healthcare service development: professionalization of service users. Soc Sci Med. (2013) 80:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.004

51. De Freitas C, Martin G. Inclusive public participation in health: policy, practice and theoretical contributions to promote the involvement of marginalised groups in healthcare. Soc Sci Med. (2015) 135:31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.019

52. Aveling EL, Jovchelovitch S. Partnerships as knowledge encounters: a psychosocial theory of partnerships for health and community development. J Health Psychol. (2014) 19:34–45. doi: 10.1177/1359105313509733

53. Cornwall A. Unpacking ‘Participation': models, meanings, and practices. Community Dev J. (2008) 43:269–83. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsn010

54. Lewis S, Bambra C, Barnes A, Collins M, Egan M, Halliday E, et al. Reframing “participation” and “inclusion” in public health policy and practice to address health inequalities: evidence from a major resident-led neighbourhood improvement initiative. Health Soc Care Community. (2019) 27:199–206. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12640

55. Wilkinson A, Parker M, Martineau F, Leach M. Engaging 'communities': anthropological insights from the West African Ebola epidemic. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. (2017) 372:20160305. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0305

Keywords: inclusiveness, health policies, religious minorities' communities, lessons from COVID-19, equity, public health

Citation: Gabay G (2023) Is it the “public” health system? The VOICE model for inclusiveness in universal (national) health systems - lessons from COVID-19. Front. Public Health 11:1243943. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1243943

Received: 21 June 2023; Accepted: 24 November 2023;

Published: 13 December 2023.

Edited by:

Maximilian Pangratius de Courten, Victoria University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Rui Dang, Westminster International University in Tashkent, UzbekistanCopyright © 2023 Gabay. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gillie Gabay, Z2lsbGllLmdhYmF5QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Gillie Gabay

Gillie Gabay