95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Public Health , 06 September 2023

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1230303

This article is part of the Research Topic Endometriosis: Focus on Quality of Life, Psychological, Sexual, and Social Aspects of the Disease View all 4 articles

Introduction: Endometriosis is a common gynecological disorder affecting approximately 10–15% of women of reproductive age. The main complaints of patients with endometriosis are pain and fertility problems. Symptoms of endometriosis can impact the psychological functioning of the patients and significantly compromise their mental health.

Methods : The aim of this review was to assess the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms and quality of life in endometriosis patients. For this systematic review, we searched the PubMed, MEDLINE, ProQuest, EMBASE, Cochrane, CINAHL, Google Scholar, Scopus, and ScienceDirect electronic databases up to March 2023 to identify potentially relevant studies. The systematic review in the present paper is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance.

Results: Of four records identified, 18 were eligible to be reviewed on the association between endometriosis and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Of 8,901 records identified, 28 were reviewed on the association between endometriosis and quality of life. The reviewed articles showed a prevalence ranging from 9.8 to 98.5% for depressive symptoms and 11.5 to 87.5% for anxiety. The quality of life in patients with endometriosis was significantly impaired, regardless of the tool used for evaluation.

Discussion: This systematic review shows that endometriosis is associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms and impaired HRQoL. Broad correlating factors modulate mental health outcomes, indicating the complex relationship between the disease and the psychological health of the patients.

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial cells outside their natural location. It is a common gynecological disorder that affects approximately 10–15% of women of reproductive age and up to 50% of women with pelvic pain and/or fertility problems (1, 2). Despite many years of research, the pathogenesis of endometriosis remains enigmatic. There have been many theories proposing the etiology of the disease, but no single one of them explains all the different clinical presentations and pathological features of endometriosis. It is possible that different subtypes of endometriosis may develop via different pathogenetic mechanisms (3). The main clinical manifestation of the disease is the presence of painful symptoms such as dysmenorrhea (pain during menstruation), dyspareunia (pain during sexual intercourse), chronic pelvic pain, acyclic pain, or dyschezia (painful defecation). The presence of pain affects the psychological and social functioning of endometriosis patients which has a profound impact on their quality of life. In endometriosis patients, the pain affects QoL more negatively than in women with other benign gynecological conditions. Moreover, each group is influenced by a different type of pain. The intensity of general perception of pain and dysmenorrhea is greater in women with endometriosis than those suffering from other painful diseases (4). Endometriosis significantly impacts the psychological functioning of the patients and compromises their mental health (5). Long-term history of endometriosis is associated with higher levels of perceived stress, suggesting that the chronicity of the disease is an independent factor affecting the perception of stress (6). Endometriosis is often present, and more often severe, among infertile women (7). Negative impact of the disease was also reported on obstetric outcomes. Women with endometriosis after natural conception have an increased risk of preterm delivery and neonatal admission to an intensive care unit, and when a severe adenomyosis is coexistent with endometriosis, a higher risk of placenta previa and cesarean delivery was observed (8).

The treatment of endometriosis includes surgical and pharmacological management. The choice of treatment method depends on the type and stage of the disease and the patient’s expectations. Therapy strategies aim mainly to increase QoL and improve fertility while lowering the risk of recurrence (9). Many medical and surgical treatments for endometriosis demonstrate comparable benefits, mainly in pain control and improvement in QoL (10). Surgical approach has a positive impact on organ impairment and sexual function in women with deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) (10) and shows a promising benefit on fertility outcomes (9). However, the repetitive surgery was revealed to have a potential negative role on psychological well-being of the patients, with an increasing number of interventions correlating with higher levels of perceived stress (6). Hormone therapy administered in the preoperative period can have a role in reducing endometriosis-associated pain; however, no significant differences on health-related quality of life were found (11).

A systematic review was conducted to evaluate the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms and quality of life assessment in patients with endometriosis. The systematic review in the present paper is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance (12).

Participants with a diagnosis of endometriosis were included, regardless of the diagnostic examination performed. Included studies evaluated the occurrence of depressive and anxiety symptoms and assessed the quality of life in patients with endometriosis. Animal studies, case series and reports, reviews, published conference abstracts, and articles published in languages other than English or Polish were excluded. Articles with paid access to the full text were excluded.

A thorough literature search was conducted via PubMed (RRID: SCR_004846), MEDLINE (RRID: SCR 002185), ProQuest (RRID: SCR_006093), EMBASE (RRID: SCR_001650), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (RRID: SCR_006576), EBSCO CINAHL (RRID: SCR_022707), Google Scholar (RRID: SCR_008878), and Scopus (RRID: SCR_022559) electronic databases up to March 2023. The search strategy for reviewing the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms included the use of the following Boolean operators: (“depressi*” OR “anxi*”) AND “endometriosis” in the titles and abstracts of articles. The sequence of terms used to identify the studies that evaluated the quality of life implemented the use of key terms such as (“quality of life” OR “QoL”) AND “endometriosis” in the titles and abstracts of the articles.

Records identified through database searching were imported into a reference manager. All records were screened by title and abstract by two independent researchers, and potentially eligible studies were identified. The full texts were assessed against the inclusion criteria of the review by two independent reviewers. Any disagreements between screeners were solved by consensus, or the opinion of a third researcher was obtained. From each report included in the present paper, the data were extracted by one reviewer and checked by another. We collected data on variables of interest that included: the report (author, year of publication); number and characteristics of participants (sample size, mean age); the study (definition and criteria for endometriosis); and the main findings (how they were ascertained, what outcomes were assessed, other variables). When available, quantitative measurements of the outcomes assessed were collected, with means and standard deviations extracted as a first choice.

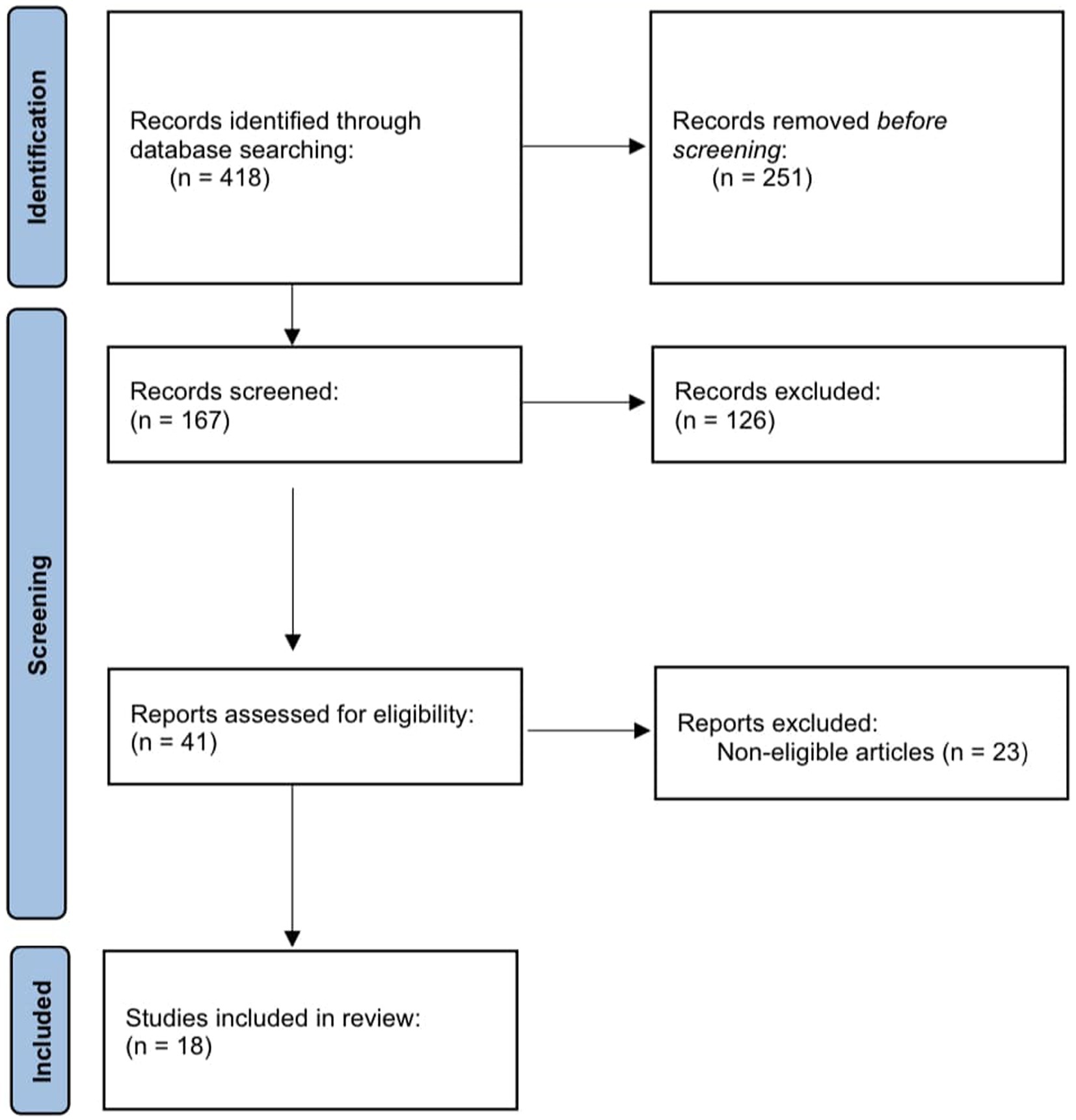

From a total of 418 records identified through database searching, 167 items were screened by title and abstract, and 41 items were assessed in full text. After the exclusion of noneligible articles, 18 studies were found to fulfill the eligibility criteria and were included in the review. For a flow diagram summarizing the article selection process, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram summarizing the selection process of articles on depressive and anxiety symptoms.

From a total of 1,192 records identified through database searching, 521 items were screened by title and abstract, and 79 items were assessed in full text. After the exclusion of noneligible articles, 28 studies were found to fulfill the eligibility criteria and were included in the review. For a flow diagram summarizing the article selection process, see Figure 2.

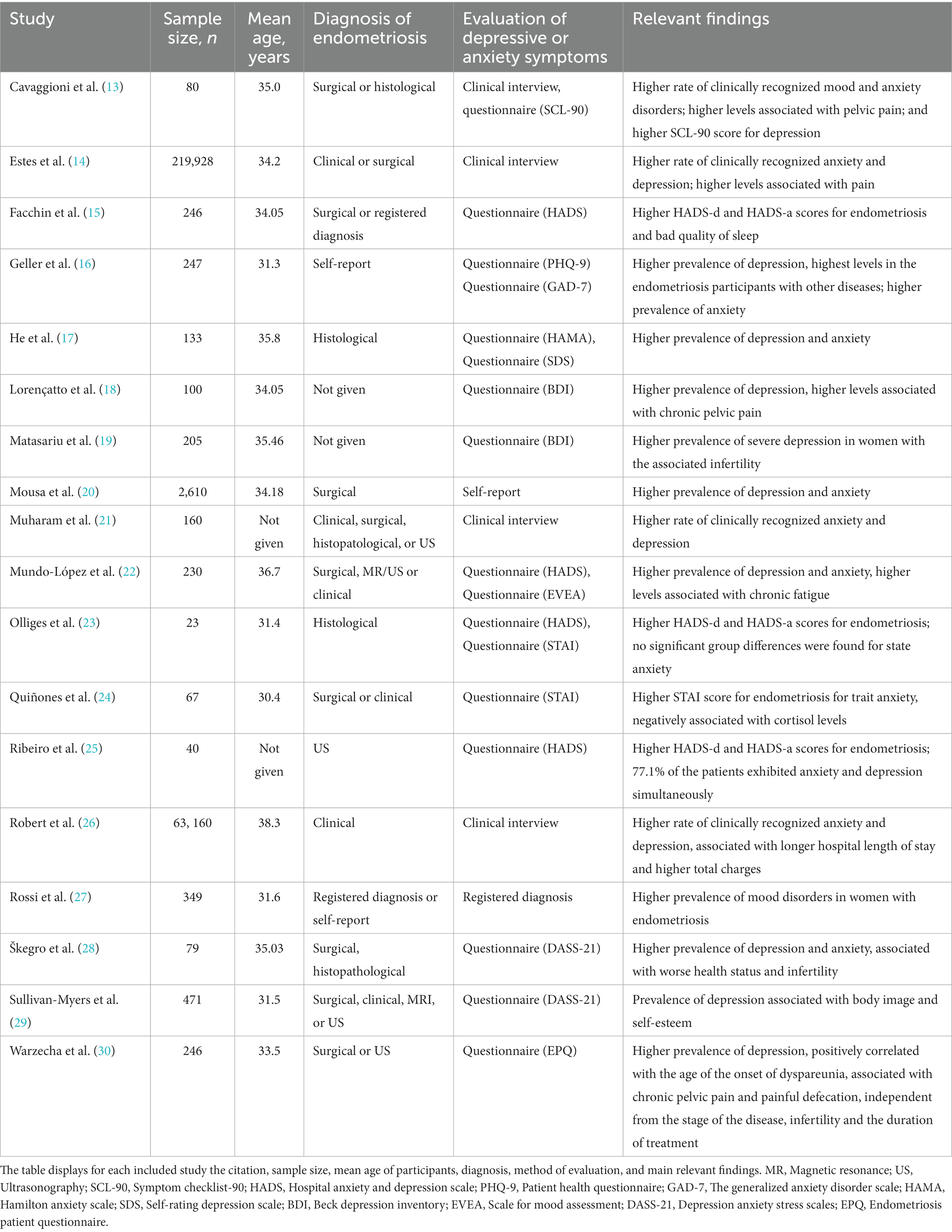

A total of 18 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. The general characteristics of the articles included in the review and their main relevant findings are presented in Table 1. Most of the articles we published during the last decade. The number of participants per study ranged from 23 to 219, 928 (total n = 288,374). The total mean age of the population was 32.45 years, and in two studies, the information was not given. The diagnostic criteria for endometriosis included surgical (55.6%), histological (27.8%), clinical (33.3%), and registered diagnosis (11.1%); self-report (11.1%); or imaging techniques such as ultrasonography or magnetic resonance (27.8%).

Table 1. Characteristics and outcomes of the included studies evaluating the impact of endometriosis on depressive and anxiety symptoms.

The most commonly applied tool to evaluate the prevalence of depressive and anxiety syndromes was a structured questionnaire. With regard to the assessment of depressive symptoms, among the most common questionnaires used were the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (22.2%) and Beck Depression Inventory (11.1%). Concerning the evaluation of anxiety symptoms, the most used questionnaire was the State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (11.1%). Three studies (16.7%) performed a structured clinical interview to assess depressive and anxiety symptoms, and one study (5.6%) based the assessment of the outcomes on a self-reporting measurement tool.

Depending on the assessment tool used, depressive symptoms occurred in 9.8–98.5% of patients with endometriosis and anxiety symptoms occurred in 11.5–87.5%. In comparison, depressive symptoms occurred in 6.6–9.3% of control groups in the included studies and anxiety symptoms in 6.0–10.1%. Estes et al. (14) reported an increased risk of developing clinically recognized depression (HR: 1.48, 95% CI: 1.44–1.53) and anxiety (HR: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.34–1.42) for patients with endometriosis compared with women never diagnosed with endometriosis. In the same study, it was observed that the hazard ratios for depression were stronger in women younger than 35 years than women ≥35 years of age.

A strong association was reported between higher rates of depression and anxiety symptoms and endometriosis-associated pain (i.e., chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, or painful defecation) and pain-related comorbidities (13, 14, 18, 29). Warzecha et al. (30) observed that the prevalence of depression was positively correlated with the age of the onset of dyspareunia (14.5 years of age, SD = 4.3 vs. 19.6, SD = 7.4 in the group without depression, p = 0.002). Inconclusive findings were reported in regard to infertility. Two studies found that higher levels of depression were associated with infertility (19, 30), and one study reported that the diagnosis of infertility was not related to the incidence of depression (OR = 0.7 95% CI 0.4–1.4) (29). Higher rates of depression and anxiety were associated with fatigue (14, 28). One study found that the incidence of depressive symptoms or chronic fatigue was independent of the stage of endometriosis (p = 0.8 to 0.9 for each stage) (29). The same study reported that the duration of treatment of endometriosis was not related to the incidence of depression (OR = 0.9 95% CI 0.8–1.2).

Other risk factors associated with incident depression and incident anxiety included prior use of opioid analgesics and asthma. Prior use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and oral contraceptives was associated with elevated rates of depression, and interstitial cystitis, allergic rhinitis, and allergies were associated with elevated rates of anxiety (14). One study reported an association between body image disturbances and the negative response of depression symptoms (18). Several factors were associated with significantly lower rates of depression and anxiety among women with endometriosis. Women who had a prior pregnancy, uterine fibroids, and hyperlipidemia had lower rates of depression and anxiety. Vitamin D deficiency was associated with a low risk of depression, and the use of oral contraceptives was associated with a low risk of anxiety (14).

Robert et al. (26) observed that women with psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and anxiety had a longer hospital stay and higher total charges compared with the non-psychiatric cohort.

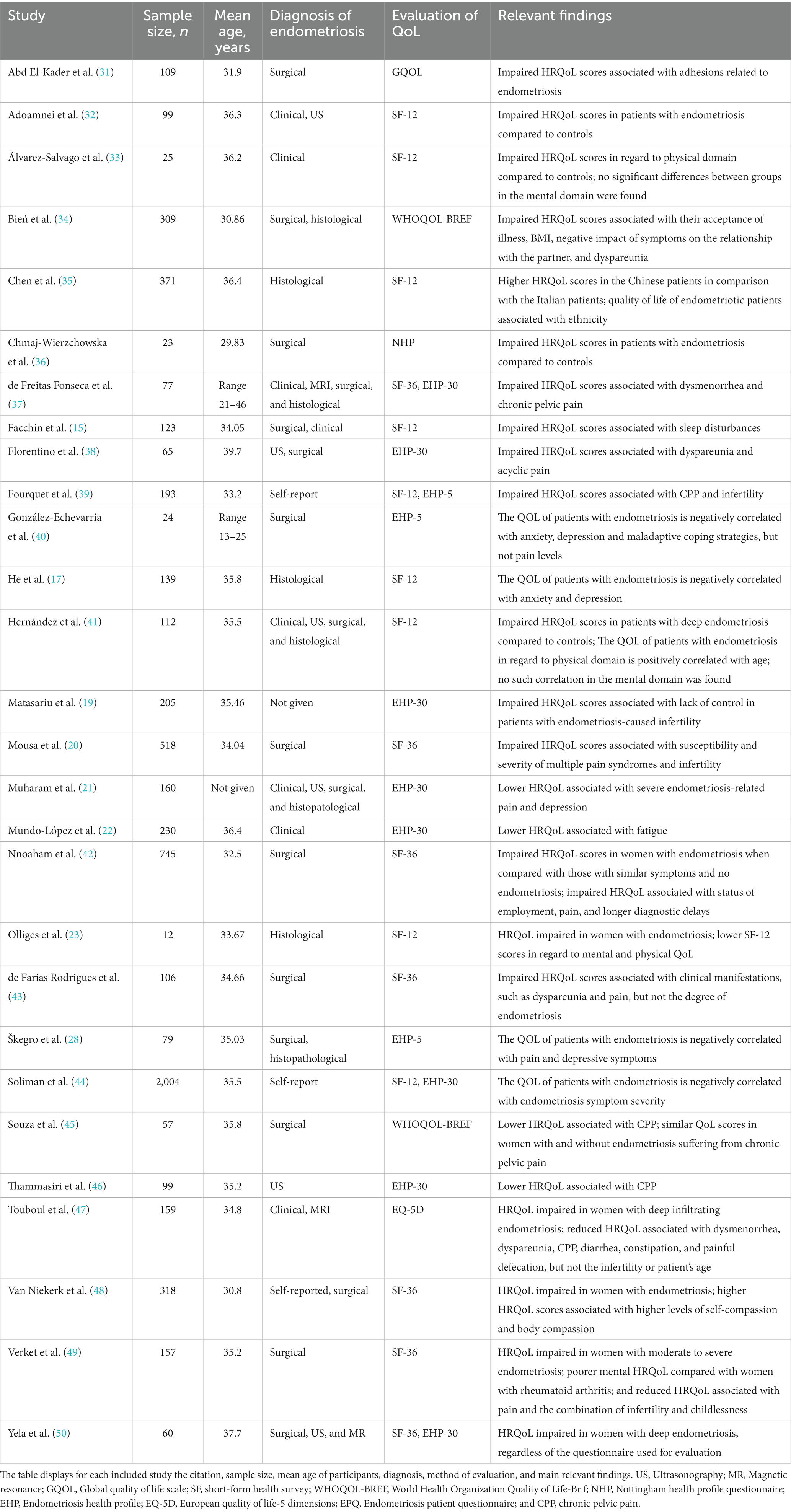

A total of 28 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. The general characteristics of the articles included in the review and their main relevant findings are presented in Table 2. Most of the articles were published during the last decade. The number of participants per study ranged from 12 to 2,004 (total n = 6,578). The total mean age of the population was 34.7 years, and in three studies, the information was not given. The diagnostic criteria for endometriosis included surgical (60.7%), histological (28.6%), clinical (28.6%), self-report (10.7%), or imaging techniques such as ultrasonography or magnetic resonance (28.6%).

Table 2. Characteristics and outcomes of the included studies evaluating the impact of endometriosis on QoL.

From the 28 selected publications, a total of eight scales for evaluation of quality of life in patients with endometriosis were identified. Thirteen of the included studies applied generic scales, and 11 studies used endometriosis-specific instruments. The most frequently used instruments were SF-36 (25%) and its short form the SF-12 (32.1%) for the generic questionnaires and EHP-30 (28.6%) and its short form the EHP-5 (10.7%) for the specific ones. Both generic and disease-specific instruments were used to evaluate the quality of life in endometriosis in four of the included studies, producing similar results (26, 37, 39, 44). Generic scales allow comparisons between patients with endometriosis and the general population. Disease-specific questionnaires better reflect the many aspects and properties of HRQoL that are important to women with endometriosis (50).

The results showed that the quality of life in patients with endometriosis was significantly impaired, regardless of the tool used for evaluation. The impairment of QoL in women affected by endometriosis is greater in both mental and physical spheres when compared to non-endometriosis conditions that appear to not affect the physical sphere of QoL (4). Lower HRQoL scores were found in comparison with women from the general population (23, 32, 33, 36, 42, 51), and poorer mental health was observed when compared with women with rheumatoid arthritis (49). Inconsistent findings on the impairment of HRQoL were observed in comparison with those with similar symptoms and no endometriosis. Nnoaham et al. (42) reported a significantly reduced physical HRQoL in women with endometriosis (n = 745) compared with symptomatic women without endometriosis (n = 587). However, Souza et al. (45) with a smaller sample size found that the presence of endometriosis in addition to chronic pelvic pain was not an independent factor impacting quality of life.

HRQoL was diminished in the large majority of the health scales of the SF-12 (seven out of eight) in Spanish women with endometriosis when compared with the control group, suggesting the influence of the disease on patients’ quality of life (22). The same study found that women with endometriosis were 8.36 times (95% CI: 4.06–17.2) more likely than controls to have lower scores in the physical domain of quality of life. Six other studies found significantly reduced physical HRQoL in affected women (32, 36, 37, 39, 42, 45). Inconsistent findings were reported in regard to the mental health component of HRQoL. Three studies noted disability in mental health status in patients with endometriosis (37, 39, 42), two studies found no significant differences between endometrial and control groups (32, 51), and one study reported higher mental health scores than the reference population (45). It was also reported that endometriosis had a negative impact on work productivity across countries and ethnicities, mainly owing to reduced effectiveness at work (36, 37).

Inconsistent findings on the quality of life in women with endometriosis were observed regarding its correlation with age. One study reported a positive correlation between the impairment of HRQoL and age (31). However, no such correlation was found in another study (41). Higher HRQoL scores were associated with higher education levels (20) and status of employment (36). Both the physical and mental scores of women in the Chinese population were higher than those of women in the Italian population, suggesting that ethnicity may affect quality of life in patients with endometriosis (35).

Quality of life was significantly impaired by the presence of adhesions resulting from endometriosis when compared with endometrial women without adhesions (49). No statistically significant differences were found in QoL based on the degree of endometriosis (45). A negative correlation between the QoL scores of the patients and their BMI was found (34). Pain was the main symptom correlated with impaired QoL in women with endometriosis (19, 20, 23, 30, 31, 36, 39, 43). Poor HRQoL was associated with different types of endometriosis pain, such as dysmenorrhea (26, 34, 47), dyspareunia (21, 31, 34, 47), acyclic pain (21, 39), and chronic pelvic pain (26, 34, 37, 38, 49). In addition, QoL was negatively correlated with pain intensity (26, 39, 47, 49). Another indicator of lower HRQoL was the presence of dyschezia (painful defecation) and diarrhea or constipation (34). In regard to infertility, inconsistent findings were reported. A negative relationship between endometriosis and infertility was found in three studies (19, 37, 43), and similar HRQoL in infertile and non-infertile women with endometriosis was found in two studies (23, 34). However, Verket et al. (49) found that childless infertile women had significantly lower mental HRQoL in comparison with infertile women with children, suggesting it may not be infertility per se but the combination of infertility and childlessness that affects mental health in women with endometriosis.

The HRQoL of patients with endometriosis was negatively correlated with anxiety and depression (19, 40, 43, 46). Facchin et al. (15) reported a strong association between sleep disturbances and poorer psychological health and quality of life in women with endometriosis. In addition, a strong association between fatigue and lower QoL was found (28). Other independent correlation factors in relation to HRQoL were the acceptance of illness, the impact of symptoms on the relationship with the partner (47), body compassion and self-compassion (48), the loss of control over the symptoms and altered emotional status (30), and maladaptive coping strategies (46).

Nnoaham et al. (42) reported an association between longer diagnostic delay and reduced physical HRQoL in affected women.

Endometriosis is a disease that affects both the physical and psychological health of patients. The aim of this systematic review was to give an overview of the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms and quality of life assessment in women with endometriosis. We also investigated the dependent factors correlated with those associations. Each of the studies included in the review reported a high rate of prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in women with endometriosis. Ribeiro et al. (25) reported that 77.1% of patients exhibited anxiety and depression simultaneously, indicating a high rate of comorbidity in women with endometriosis. In addition, it was reported that patients with endometriosis had an increased risk of developing clinically recognized depression and anxiety compared with women never diagnosed with endometriosis. The evidence presented should raise awareness of the link between endometriosis and the psychological functioning of the patients. We suggest integrating a psychological assessment of women with endometriosis in order to identify those at risk of developing symptoms of depression or anxiety and providing them with adequate support to improve the psychological outcomes.

The quality of life of patients with endometriosis was significantly impaired. The HRQoL scores were lower in comparison with women from the general population and women with rheumatoid arthritis, but inconsistent findings were reported when compared with those with similar symptoms and no endometriosis. More studies are needed to assess the impairment of HRQoL in conditions representing chronic pelvic pain to further evaluate this association.

The studies investigating sociodemographic characteristics associated with higher rates of affective symptoms found that women with endometriosis younger than 35 years of age had a higher rate of clinically recognized depression. Inconsistent findings were reported on the correlation between age and quality of life in patients with endometriosis, whereas a positive association was found between higher education levels or status of employment and HRQoL.

It has been reported that it is not the stage of endometriosis that impacts the QoL of women with endometriosis, but rather the clinical manifestations of the disease (34). Endometriosis-associated pain such as chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, or painful defecation was associated with a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms and lower QoL. The incidence of depressive and anxiety symptoms appears to be higher in endometriosis patients compared with other forms of chronic pelvic pain (4). Pain intensity was positively correlated with depressive and anxiety scores, and a negative correlation was found between pain intensity and HRQoL scores, which led to the interpretation that the more intense the pain, the higher the occurrence of affective symptoms and the worse the quality of life. The current evidence does not allow for the conclusion that infertility in women with endometriosis is associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety or impairment of QoL. Perhaps it is the combination of infertility and childlessness that affects the mental health of women with endometriosis, as Verket et al. (49) found that childless infertile women had significantly lower mental HRQoL in comparison with infertile women with children. Studies investigating quality of sleep as a dependent factor reported a strong association between sleep disturbances and poorer psychological health and quality of life in women with endometriosis. In addition, bad quality of sleep among endometriosis patients was associated with greater fatigue, and fatigue was correlated with higher rates of depression and anxiety and lower QoL scores. Those findings suggest a need for a holistic approach in healthcare assistance for endometriosis patients. A better integration of all aspects of patient care is likely to improve both the physical and psychological outcomes.

Other studies included in this review suggest that risk factors correlated with depressive and anxiety symptoms in women with endometriosis include prior use of opioid analgesics and asthma. Elevated rates of depression were associated with prior use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and oral contraceptives; and interstitial cystitis, allergic rhinitis, and allergies were associated with elevated rates of anxiety. Independent correlation factors in relation to HRQoL include the acceptance of illness, the impact of symptoms on the relationship with the partner, the loss of control over the symptoms and altered emotional status, and maladaptive coping strategies. These findings indicate that the relationship between endometriosis and poorer psychological health and impaired quality of life is complex and that many dependent factors are involved in this association. Awareness of the relationship between endometriosis and mental health of the patients informs tailored care and allows for a patient-centered approach.

Furthermore, an association between longer diagnostic delay and reduced HRQoL was reported, which indicates the importance of heightened awareness of the disease among clinicians. Psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and anxiety in women with endometriosis are associated with a longer hospital mean length of stay and higher total charges. In addition, endometriosis was found to exert a negative impact on productivity at work. Earlier diagnosis and symptom control strategies should translate into improving psychological health, a shorter hospital length of stay, lower total charges, and better work productivity of the affected women.

This systematic review shows that endometriosis is associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms and impaired HRQoL. Broad correlating factors modulate mental health outcomes, indicating a complex relationship between the disease and the psychological health of the patients. We hope that the evidence presented in this paper will raise awareness of the link between endometriosis and symptoms of depression and anxiety. We suggest integrating a psychological assessment of these patients in order to identify those at risk of developing mental health issues and providing them with adequate support. A better integration of all aspects of patient care is likely to improve both the physical and psychological outcomes.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

MS and RT contributed to conception and design of the study. MS, RT, and KK contributed to the methodology of the study and reviewed and edited the sections of the manuscript. RT performed the formal analysis. MS and KK organized the database and curated the data. MS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RT and KK were responsible for the project administration. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Smolarz, B, Szyłło, K, and Romanowicz, H. Endometriosis: epidemiology, classification, pathogenesis, treatment and genetics (review of literature). Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:10554. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910554

2. Missmer, SA, Hankinson, SE, Spiegelman, D, Barbieri, RL, Marshall, LM, and Hunter, DJ. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. (2004) 160:784–96. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh275

3. Signorile, PG, Viceconte, R, and Baldi, A. New insights in pathogenesis of endometriosis. Front Med. (2022) 9:879015. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.879015

4. Centini, G, Lazzeri, L, Dores, D, Pianigiani, L, Iannone, P, Luisi, S, et al. Chronic pelvic pain and quality of life in women with and without endometriosis. J Endometr Pelvic Pain Disord. (2013) 5:27–33. doi: 10.5301/JE.5000148

5. Laganà, AS, La Rosa, VL, Rapisarda, AMC, Valenti, G, Sapia, F, Chiofalo, B, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with endometriosis: impact and management challenges. Int J Women's Health. (2017) 9:323–30. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s119729

6. Lazzeri, L, Orlandini, C, Vannuccini, S, Pinzauti, S, Tosti, C, Zupi, E, et al. Endometriosis and perceived stress: impact of surgical and medical treatment. Gynecol Obstet Investig. (2015) 79:229–33. doi: 10.1159/000368776

7. Strathy, JH, Molgaard, CA, Coulam, CB, and Melton, LJ. Endometriosis and infertility: a laparoscopic study of endometriosis among fertile and infertile women. Fertil Steril. (1982) 38:667–72. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)46691-4

8. Berlanda, N, Alio, W, Angioni, S, Bergamini, V, Bonin, C, Boracchi, P, et al. Impact of endometriosis on obstetric outcome after natural conception: a multicenter Italian study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2022) 305:149–57. doi: 10.1007/s00404-021-06243-z

9. Daniilidis, A, Angioni, S, Di Michele, S, Dinas, K, Gkrozou, F, and D'Alterio, MN. Deep endometriosis and infertility: what is the impact of surgery? J Clin Med. (2022) 11:6727. doi: 10.3390/jcm11226727

10. Di Donato, N, Montanari, G, Benfenati, A, Monti, G, Leonardi, D, Bertoldo, V, et al. Sexual function in women undergoing surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis: a comparison with healthy women. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. (2015) 41:278–83. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2014-100993

11. Mabrouk, M, Frascà, C, Geraci, E, Montanari, G, Ferrini, G, Raimondo, D, et al. Combined oral contraceptive therapy in women with posterior deep infiltrating endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2011) 18:470–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2011.04.008

12. Page, MJ, Moher, D, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160

13. Cavaggioni, G, Lia, C, Resta, S, Antonielli, T, Benedetti Panici, P, Megiorni, F, et al. Are mood and anxiety disorders and alexithymia associated with endometriosis? A preliminary study. Biomed Res Int. (2014) 2014:786830. doi: 10.1155/2014/786830

14. Estes, SJ, Huisingh, CE, Chiuve, SE, Petruski-Ivleva, N, and Missmer, SA. Depression, anxiety, and self-directed violence in women with endometriosis: a retrospective matched-cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. (2021) 190:843–52. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwaa249

15. Facchin, F, Buggio, L, Roncella, E, Somigliana, E, Ottolini, F, Dridi, D, et al. Sleep disturbances, fatigue and psychological health in women with endometriosis: a matched pair case-control study. Reprod BioMed Online. (2021) 43:1027–34. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.08.011

16. Geller, S, Levy, S, Ashkeloni, S, Roeh, B, Sbiet, E, and Avitsur, R. Predictors of psychological distress in women with endometriosis: the role of multimorbidity, body image, and self-criticism. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:3453. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073453

17. He, G, Chen, J, Peng, Z, Feng, K, Luo, C, and Zang, X. A study on the correlation between quality of life and unhealthy emotion among patients with endometriosis. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:830698. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.830698

18. Lorençatto, C, Petta, CA, Navarro, MJ, Bahamondes, L, and Matos, A. Depression in women with endometriosis with and without chronic pelvic pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (2006) 85:88–92. doi: 10.1080/00016340500456118

19. Matasariu, RD, Mihaila, A, Iacob, M, Dumitrascu, I, Onofriescu, M, Crumpei Tanasa, I, et al. Psycho-social aspects of quality of life in women with endometriosis. Acta Endocrinol. (2017) 13:334–9. doi: 10.4183/aeb.2017.334

20. Mousa, M, Al-Jefout, M, Alsafar, H, Becker, CM, Zondervan, KT, and Rahmioglu, N. Impact of endometriosis in women of Arab ancestry on: health-related quality of life, work productivity, and diagnostic delay. Front Glob Womens Health. (2021) 2:708410. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2021.708410

21. Muharam, R, Amalia, T, Pratama, G, Harzif, AK, Agiananda, F, Maidarti, M, et al. Chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis is associated with psychiatric disorder and quality of life deterioration. Int J Women's Health. (2022) 14:131–8. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s345186

22. Mundo-López, A, Ocón-Hernández, O, San-Sebastián, AP, Galiano-Castillo, N, Rodríguez-Pérez, O, Arroyo-Luque, MS, et al. Contribution of chronic fatigue to psychosocial status and quality of life in Spanish women diagnosed with endometriosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3831. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113831

23. Olliges, E, Bobinger, A, Weber, A, Hoffmann, V, Schmitz, T, Popovici, RM, et al. The physical, psychological, and social day-to-day experience of women living with endometriosis compared to healthy age-matched controls-a mixed-methods study. Front Glob Womens Health. (2021) 2:767114. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2021.767114

24. Quiñones, M, Urrutia, R, Torres-Reverón, A, Vincent, K, and Flores, I. Anxiety, coping skills and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in patients with endometriosis. J Reprod Biol Health. (2015) 3:2. doi: 10.7243/2054-0841-3-2

25. Ribeiro, H, Paiva, AMF, Talibeti, B, Gonçalves, ALL, Condes, RP, and Ribeiro, P. Psychological problems experienced by patients with bowel endometriosis awaiting surgery. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. (2021) 43:676–81. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1735938

26. Robert, CA, Caraballo-Rivera, EJ, Isola, S, Oraka, K, Akter, S, Vrma, S, et al. Demographics and hospital outcomes in American women with endometriosis and psychiatric comorbidities. Cureus. (2020) 12:e9935. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9935

27. Rossi, HR, Uimari, O, Terho, A, Pesonen, P, Koivurova, S, and Piltonen, T. Increased overall morbidity in women with endometriosis: a population-based follow-up study until age 50. Fertil Steril. (2023) 119:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.09.361

28. Škegro, B, Bjedov, S, Mikuš, M, Mustač, F, Lešin, J, Matijević, V, et al. Endometriosis, pain and mental health. Psychiatr Danub. (2021) 33:6326–36.

29. Sullivan-Myers, C, Sherman, KA, Beath, AP, Cooper, MJW, and Duckworth, TJ. Body image, self-compassion, and sexual distress in individuals living with endometriosis. J Psychosom Res. (2023) 167:111197. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2023.111197

30. Warzecha, D, Szymusik, I, Wielgos, M, and Pietrzak, B. The impact of endometriosis on the quality of life and the incidence of depression—a cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3641. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103641

31. Abd El-Kader, AI, Gonied, AS, Lotfy Mohamed, M, and Lotfy Mohamed, S. Impact of endometriosis-related adhesions on quality of life among infertile women. Int J Fertil Steril. (2019) 13:72–6. doi: 10.22074/ijfs.2019.5572

32. Adoamnei, E, Morán-Sánchez, I, Sánchez-Ferrer, ML, Mendiola, J, Prieto-Sánchez, MT, Moñino-García, M, et al. Health-related quality of life in adult Spanish women with Endometriomas or deep infiltrating endometriosis: a case-control study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:5586. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115586

33. Álvarez-Salvago, F, Lara-Ramos, A, Cantarero-Villanueva, I, Mazheika, M, Mundo-López, A, Galiano-Castillo, N, et al. Chronic fatigue, physical impairments and quality of life in women with endometriosis: a case-control study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3610. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103610

34. Bień, A, Rzońca, E, Zarajczyk, M, Wilkosz, K, Wdowiak, A, and Iwanowicz-Palus, G. Quality of life in women with endometriosis: a cross-sectional survey. Qual Life Res. (2020) 29:2669–77. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02515-4

35. Chen, H, Vannuccini, S, Capezzuoli, T, Ceccaroni, M, Mubiao, L, Shuting, H, et al. Comorbidities and quality of life in women undergoing first surgery for endometriosis: differences between Chinese and Italian population. Reprod Sci. (2021) 28:2359–66. doi: 10.1007/s43032-021-00487-5

36. Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K, Rzymski, P, Wojciechowska, M, Parda, I, and Wilczak, M. Health-related quality of life (Nottingham health profile) in patients with endometriomas: correlation with clinical variables and self-reported limitations. Arch Med Sci. (2020) 16:584–91. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2019.82744

37. De Freitas Fonseca, M, Aragao, LC, Sssa, FV, Dutra de Resende, JA Jr, and Crispi, CP. Interrelationships among endometriosis-related pain symptoms and their effects on health-related quality of life: a sectional observational study. Obstet Gynecol Sci. (2018) 61:605–14. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2018.61.5.605

38. Florentino, AVA, Pereira, AMG, Martins, JA, Lopes, RGC, and Arruda, RM. Quality of life assessment by the endometriosis health profile (EHP-30) questionnaire prior to treatment for ovarian endometriosis in Brazilian women. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. (2019) 41:548–54. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1693057

39. Fourquet, J, Báez, L, Figueroa, M, Iia, TRI, and Flores, I. Quantification of the impact of endometriosis symptoms on health-related quality of life and work productivity. Fertil Steril. (2011) 96:107–12. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.04.095

40. González-Echevarría, AM, Rosario, E, Acevedo, S, and Flores, I. Impact of coping strategies on quality of life of adolescents and young women with endometriosis. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. (2019) 40:138–45. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2018.1450384

41. Hernández, A, Muñoz, E, Ramiro-Cortijo, D, Spagnolo, E, Lopez, A, Sanz, A, et al. Quality of life in women after deep endometriosis surgery: comparison with Spanish standardized values. J Clin Med. (2022) 11:6192. doi: 10.3390/jcm11206192

42. Nnoaham, KE, Hummelshoj, L, Webster, P, D’Hooghe, T, De Cicco Nardone, F, De Cicco Nardone, C, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. (2011) 96:366–373.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.090

43. de Farias, P, Rodrigues, M, Lima Vilarino, F, De Souza Barbeiro Munhoz, A, Da Silva Paiva, L, De Alcantara Sousa, LV, et al. Clinical aspects and the quality of life among women with endometriosis and infertility: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. (2020) 20:124. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-00987-7

44. Soliman, AM, Sigh, S, Rahal, Y, Robert, C, Defoy, I, Nisbet, P, et al. Cross-sectional survey of the impact of endometriosis symptoms on health-related quality of life in Canadian women. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. (2020) 42:1330–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2020.04.013

45. Souza, CA, Oliveira, LM, Scheffel, C, Genro, VK, Rosa, V, Chaves, MF, et al. Quality of life associated to chronic pelvic pain is independent of endometriosis diagnosis--a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2011) 9:41. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-41

46. Thammasiri, C, Amnatbuddee, S, Sothornwit, J, Temtanakitpaisan, T, and Buppasiri, P. A cross-sectional study on the quality of life in women with Endometrioma. Int J Women's Health. (2022) 14:9–14. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s341603

47. Touboul, C, Amate, P, Ballester, M, Bazot, M, Fauconnier, A, and Daraï, E. Quality of life assessment using EuroQOL EQ-5D questionnaire in patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis: the relation with symptoms and locations. Int J Chronic Dis. (2013) 2013:452134. doi: 10.1155/2013/452134

48. Van Niekerk, LM, Dell, B, Johnstone, L, Matthewson, M, and Quinn, M. Examining the associations between self and body compassion and health related quality of life in people diagnosed with endometriosis. J Psychosom Res. (2023) 167:111202. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2023.111202

49. Verket, NJ, Uhlig, T, Sandvik, L, Andersen, MH, Tanbo, TG, and Qvigstad, E. Health-related quality of life in women with endometriosis, compared with the general population and women with rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (2018) 97:1339–48. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13427

50. Yela, DA, Quagliato, IP, and Benetti-Pinto, CL. Quality of life in women with deep endometriosis: a cross-sectional study. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. (2020) 42:090–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1708091

Keywords: women’s mental health, women’s psychological functioning, endometriosis, depression, anxiety, quality of life

Citation: Szypłowska M, Tarkowski R and Kułak K (2023) The impact of endometriosis on depressive and anxiety symptoms and quality of life: a systematic review. Front. Public Health. 11:1230303. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1230303

Received: 01 June 2023; Accepted: 21 August 2023;

Published: 06 September 2023.

Edited by:

Diego Raimondo, University of Bologna, ItalyReviewed by:

Maurizio Nicola D'Alterio, University of Cagliari, ItalyCopyright © 2023 Szypłowska, Tarkowski and Kułak. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Małgorzata Szypłowska, bWFsZ29yemF0YS5zenlwbG93c2thQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.