- 1Primary Care Mental Health Research Program, The Department of General Practice and Primary Care, Melbourne Medical School, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

- 2The ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

- 3Co-Design Living Labs Program Members, Primary Care Mental Health Research Program, The Department of General Practice and Primary Care, Melbourne Medical School, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

There is increased recognition that people with lived-experience of mental ill-health ought to be centred in research design, implementation and translation, and quality improvement and program evaluation of services. There is also an increased focus on ways to ensure that co-design processes can be led by people with lived-experience of mental ill-health. Despite this, there remains limited explanation of the physical, social, human, and economic infrastructure needed to create and sustain such models in research and service settings. This is particularly pertinent for all health service sectors (across mental and physical health and social services) but more so across tertiary education settings where research generation occurs for implementation and translation activities with policy and services. The Co-Design Living Labs program was established in 2017 as an example of a community-based embedded approach to bring people living with trauma and mental ill-health and carers/family and kinship group members together with university-based researchers to drive end-to-end research design to translation in mental healthcare and research sectors. The program’s current membership is near to 2000 people. This study traces the evolution of the program in the context of the living labs tradition of open innovation. It overviews the philosophy of practice for working with people with lived-experience and carer/family and kinship group members—togetherness by design. Togetherness by design centres on an ethical relation of being-for that moves beyond unethical and transactional approaches of being-aside and being-with, as articulated by sociologist Zygmunt Bauman. The retrospective outlines how an initial researcher-driven model can evolve and transform to become one where people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carer/family kinship group members hold clear decision-making roles, share in power to enact change, and move into co-researcher roles within research teams. Eight mechanisms are presented in the context of an explanatory theoretical model of change for co-design and coproduction, which are used to frame research co-design activities and provide space for continuous learning and evolution of the Co-Design Living Labs program.

1 Introduction

Embedding lived-experience (or what is also termed within the published literature as service users, experts-by-experience, and within government reports/policies as consumers and/or carers perspectives) within research, service design/re-design and systems re-design, and healthcare improvement has evolved into a wider trend of participation called the Participatory Zeitgeist, or “the spirit of our times” (1). This Zeitgeist has been driven by a confluence of social, cultural, political, and economic forces that permeates all sectors and indeed much of our public and personal lives (2). This spirit of our times has led to a dramatic increase in ‘co’ practices and recognition from social, academic, and political circles of the importance of experiential knowledge as evidence-based approaches. However, the extent to which this experiential knowledge is afforded equivalent weighting within the established hierarchy of evidence applied in research, policy, and service design and practice is limited (3–5).

Additionally, the growth in “co” practices has led to an increase in what has been termed co-biquity (6). This has been defined as “an apparent appetite for participatory research practice and increased emphasis on partnership working, in combination with the related emergence of a plethora, of ‘co’ words” (6). Although part of the co-biquity challenge is that many of the participatory methods and practices outlined as co-design or coproduction and other collaborative terms are rarely evaluated against core criterion such as who has been involved, how have people been engaged in collaborative processes of designing together, and what was designed or made for change or implemented as a result. Similarly, it is rare to see an evaluation of the extent to which co-design processes, methods, and outcomes have addressed structural and interpersonal inequalities in power and decision-making (7). Where evaluation material is available, it is largely qualitative interview reports of people’s experiences participating in co-design projects for service improvement (8).

Over a decade ago, authors in co-design fields began to raise concerns over the dilution and conflation of meanings and practices from collaborative traditions and the misappropriation of the terms co-design and coproduction (9). Such broad usage of coproduction and co-design terminology across a range of research disciplines (for example, urban planning, public management, environmental studies, design fields broadly, and education) and within healthcare quality improvement and in service design/re-design, has seen participatory approaches adopted in expansive ways. The pendulum has swung further in the co-design field when looking at healthcare quality improvement practices and what might be termed ‘mainstream’ service design/re-design processes. Where co-design once was defined as “the creativity of designers and people not trained in design working together in the design development process” (10), it has now come to focus on a central role for people with lived-experience (9, 11).

Historically, published literature has been replete with reference to the concept of “user/s” to define the goal for design to centre user’s needs and perspectives (12). This phenomenon of user participation is not all that new; participatory design definitions and practices have been premised on this also (11). Lucero and Vaajakallio (13) reported that “researchers have started to see ‘everyday people’ not only as the recipients of the artefacts of the design process, but as active participants in the design and production process itself, capable of adapting products to better meet their own needs”. In short, as Steen has argued previously, co-design thus reflects “an instance of moral [e]nquiry…” and a return to pragmatist ethics where the “return to ordinary life-experiences of inherently social, embodied, and historically situated beings” (9) is key.

In the current context of co-design, however, lived-experience-centred models mean more than a workshop with users about the appropriateness or usability of a product or technology, more than the ordinary and situated life experience, and more than user engagement. Quality and service improvement fields quite rightly are about bringing “service providers, service users and other relevant stakeholders [together to] use design tools and methods to work collaboratively to ensure service provision is informed by their shared experiences” (14). In mental healthcare (both in relation to research and to the delivery of care), significant power disparities exist, and indeed human rights abuses have occurred. Thus, active participation through methods that centre experience is essential to ensure that the goals of social justice are met. In this respect, experience-based processes of co-design are core to working with existing inequities and human rights abuses and exploring experiential injustices. The current emphasis on mental health reform, at least in Australia, also means that it is critical to consider how people with lived-experience may increasingly lead or co-lead co-design processes (15). That means there is a need to attend to co-analysis and interpretation of the results of co-design so that epistemic injustices (how knowledge is formed, shared, implemented, and evaluated) are not repeated inadvertently (5). In the shorter term, where co-design is espoused, there is a need for actively attending to how power was re-balanced and where designers were positioned within co-design processes. We need to shed light not only on what happened in co-design but also on what was implemented, where it might have led to change, and what the impacts of this might have been.

While mainstream service design/re-design, quality improvement, and systems transformation efforts have grappled with the implementation of co-design for some time now, there has been less examination of how to configure academic, university, and other research settings to embed lived-experience-centred models for research implementation and translation efforts (4, 12). Given the hierarchical nature of academic contexts and the diversity of mental health research disciplines, this is challenging, and there is a need to evaluate how lived-experience is being somewhat uncomfortably positioned as an indicator of political and social recognition of inclusion (16, 17). Centring lived-experience is particularly important in spaces where people have experienced systemic injustices and possibly significant harm and have not had the full protection of human rights and recognition of their voices. In these circumstances, people may not have been included in decisions about service design, development, or what programs are offered and how care is delivered. Inclusion alone, however, is not an indicator of political and social recognition. Increasingly, literature is emerging on co-designed interventions or co-design for research projects, and it can be an expectation by funders to illustrate co-design (or consumer and community participation as government agencies word it) in research grants (18). This gives cause to consider the kind of research architecture that is needed to embed lived-experience within end-to-end research design to translation using co-design. It also means we must pay close attention to how lived-experience is understood and included in co-design efforts.

Contemporarily, lived-experience refers to both working collectively with people who have direct experiences of the topic, issues, or problem in focus for co-design and the interaction of experiential knowledge within co-design, ensuring epistemic justice (valuing of experiential knowledge) is achieved (5). It includes attention to the framings for co-design, being clear about what social justice issues are being addressed, and how co-design is explicitly addressing power imbalances (19). In more recent developments in mental health research, suicide prevention, and within First Nations methodologies and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing programs, lived-experience has become key to addressing harms that have been experienced with the removal of rights and human rights abuses. Defining the parameters of lived-experience within co-design has become important, and ensuring lived-experience reflects “direct, first-hand substantive experience of mental distress, illness, diagnosis and/or mental health services. [Or] as associated with Lived Experience of poverty, trauma and other forms of prejudice and discrimination (e.g., racism and ableism)” (20) (p. 3) is fundamental. Publications on the importance of inclusion and lived-experience leadership expand upon substantive experience to suggest that diverse qualities are held and enacted by people with lived-experience, which generate change within and across mental health and social sectors (such as championing justice, centring lived-experience, and building relationships with peers and allies) (17). In the context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, lived-experience is expanded to “recognise the effects of ongoing negative historical impacts of colonisation or specific events on the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It encompasses the cultural, spiritual, physical, emotional, and mental wellbeing of the individual, family, or community” (21). Attention to lived-experience has become key to ensuring social justice and issues of inequity, and structural inequalities are in focus within co-design.

In the Co-Design Living Labs program and its philosophy of practice, lived-experience is described and applied as “community-led lived-experience.” This means that people engage as members of the program (referred to in our current day-to-day activities and engagements as co-designers) with their direct, personal experiences of mental ill-health and service systems or support expertise as carer/family and kinship groups. Importantly, there may also be nuances and elements of lived-experience located from identities in community stories, events, and happenings that are critical to the framing and shaping of experience. Therefore, conveners of co-design aim to always work closely with how the communities we are collaborating with shape and define lived-experience from the perspectives and positionalities of people within co-design. Community-led lived-experience thus acknowledges a need to recognise framings that may encompass cultural, social, and political differences to direct experience. This includes attention to the appropriateness of methods that are adopted within co-design.

This study outlines the establishment and evolution of the Co-Design Living Labs program and its philosophy of practice within The University of Melbourne between 2017 to present. It documents the establishment and transitions of the program from researcher-led to increasingly co-designer-led over this period. By philosophy of practice, we refer to the values upheld in our study, the roles and responsibilities of our ways of working together for change in implementation and translational research, and the component parts required for the operationalisation of the program. We call this philosophy of practice “togetherness by design.” The philosophy of practice couples theoretical work from sociologist Zygmunt Bauman’s articulation of three forms of togetherness: being-aside, being-with, and being-for (22). Co-design is understood as the “co” equating with togetherness and therefore the practices being about “designing together”. However, in keeping with co-design traditions, designing together means thinking about both what is made and how that making attends to social justice. It includes an evaluation of supported and shared decision-making processes that were applied and how power imbalances were addressed as they play out in the living labs’ tradition of open innovation and collective empowerment (23).

2 Materials and method

The Co-Design Living Labs program was founded within the Primary Care Mental Health research group in 2017. The program is now expanding as part of a national network in the ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council 2021–2026 (GNT2002047) as part of a Special Initiative in Mental Health. The ALIVE National Centre’s mission is transforming mental health and wellbeing through primary care and community action. Its vision is for vibrant communities that support mental health and wellbeing to enable people to thrive. There are currently 17 university partners engaged in the Centre’s work, with membership growing across three networks supporting research program implementation and translation. The Centre grows lived-experience research capabilities within a tailored arm of a Next Generation Researcher network called the Lived-Experience Research Collective. An Implementation and Translation network is focused on growing capabilities and a national infrastructure to support adaptive co-design, demonstration projects, and promising models. The Co-Design Living Labs network will connect co-design programs across universities to expand end-to-end research design to translation. This builds on the aim of the Co-Design Living Labs program to create a purposeful space for people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carers/family and kinship group members to co-create research and translation activities. Since its establishment in 2017, the program has grown from a membership of 600+ people to current membership of nearly 2000 people across Victoria and other states and territories of Australia. In this retrospective, we mark the transitions from an initially researcher-driven operational model set up by the lead author, who has lived-experience of mental ill-health (24), to one where co-designers now identify priorities for research and where their perspectives are shaping the research questions and approaches that are developed. It is important to acknowledge that the personal experiences of the lead author in navigating the re-definition of self that comes with lived-experience was a key motivator for program establishment. This included a view that there was a need to improve community-led mental health research and for better engagement processes in university-based research (25). These foundational values mean that lived-experience has shaped the co-design practices and processes undertaken since inception. More recent transitions in the program now include that co-designers have moved to co-researcher roles (which we will explain later) and an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander co-design research lead has been appointed in 2021. This study does not outline the transition to the inclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-led work; this will be detailed in a separate article illustrating the role of Indigenous Knowledge Systems whereby co-design may be articulated with different cultural practices (26). The future goal is that co-designers in the current program will adopt the living labs as a social enterprise utilising cooperative, democratic structures to maintain a commitment to the important issues of justice, power, and shared decision-making. This would support co-designers to drive the research agendas and co-convene the activities of the program with direct fiscal benefit flowing to them.

2.1 Recruitment to the co-design living labs program

The Co-Design Living Labs program membership base was grown by inviting former research participants (people with lived-experience) from completed mental health research studies to join. Two longitudinal studies were completed in the primary care mental health research program in 2016 and 2017: (a) a world-first stepped wedge cluster randomised trial (9) of an adapted mental health experience co-design approach for service improvement and psychosocial recovery outcomes, with 287 people living with conditions described in the literature as severe mental illness (herein referred to as mental ill-health)—the CORE Study (2012–2017) and (b) the diamond study (17) exploring over 700+ people’s experiences of living with depression and health services use (2003–2016). Completion of these flagship studies provided a turning point and an opportunity to shift away from what may be characterised as transactional research processes and agendas to relationally oriented practices.

2.1.1 The adoption of a living labs approach

The living labs concept was identified as an open innovation pathway for mental health research to build on cooperative traditions and relational practices. It was adopted with a view to a future cooperative structured social enterprise being established from the program, as mentioned in the above section. Additionally, we sought to disrupt the idea that research practices located within a medical setting are only about scientific lab-based research, which has historically been characterised as having limited engagement of the public. Living labs in these environments have also tended to foster a test bed model where users are the objects of study rather than co-creators (12). Here, the term living lab was adopted to signal life, living, being alive and dynamic, and the importance of working with people in medical and health research activities every day with lived-experience. Bringing co-design and living labs together enabled the program to foreground social justice, power, and shared decision-making in activities.

In the literature, four key traits of living labs have been described: (1) a purpose to innovate products and services; (2) co-creation with users; (3) completion of activities in real-life settings; and (4) fostering public–private partnerships (27). These traits are essential where the focus is on innovation and co-creation, and they enable our program and future network-based activities to effectively operate an anywhere, everywhere living laboratory focused on real-life settings. This fits with the European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL) definition of living labs as “user-centred open innovation ecosystems based on a systematic user co-creation approach, integrating research and innovation processes in real-life communities and settings” (28). Our approach, however, expands the living labs’ tradition from a grounding in social innovation, partnerships, and open approaches to operationalisation of these factors within a lived-experience context. Therefore, we intentionally brought together the practices of Co-Design with Living Labs for the naming and setup of the program (19, 29).

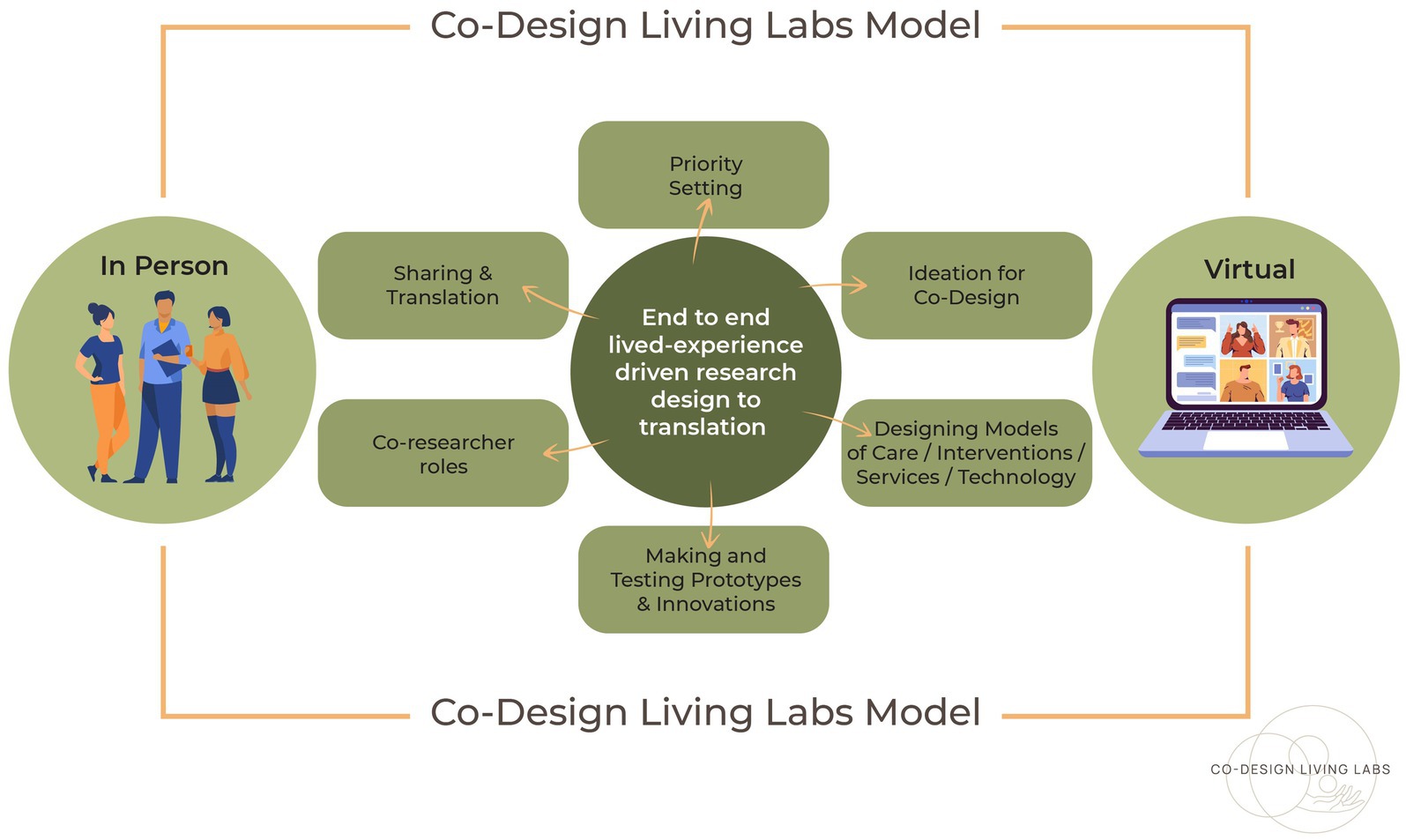

In this relational form of engagement, the goal was to ensure lived-experience became embedded within the priority setting of research grant proposals and the establishment of research questions. This included the ideation on component parts of these grants or other innovations, the co-creation of new models of care (also termed interventions in the health sciences literature) and healthcare technologies and processes, and the making and shaping of prototypes (using paper to technology-facilitated approaches, and with co-research and dissemination and communication). These aforementioned goals form the foundations of the Co-Design Living Labs operating model, which is presented in Figure 1.

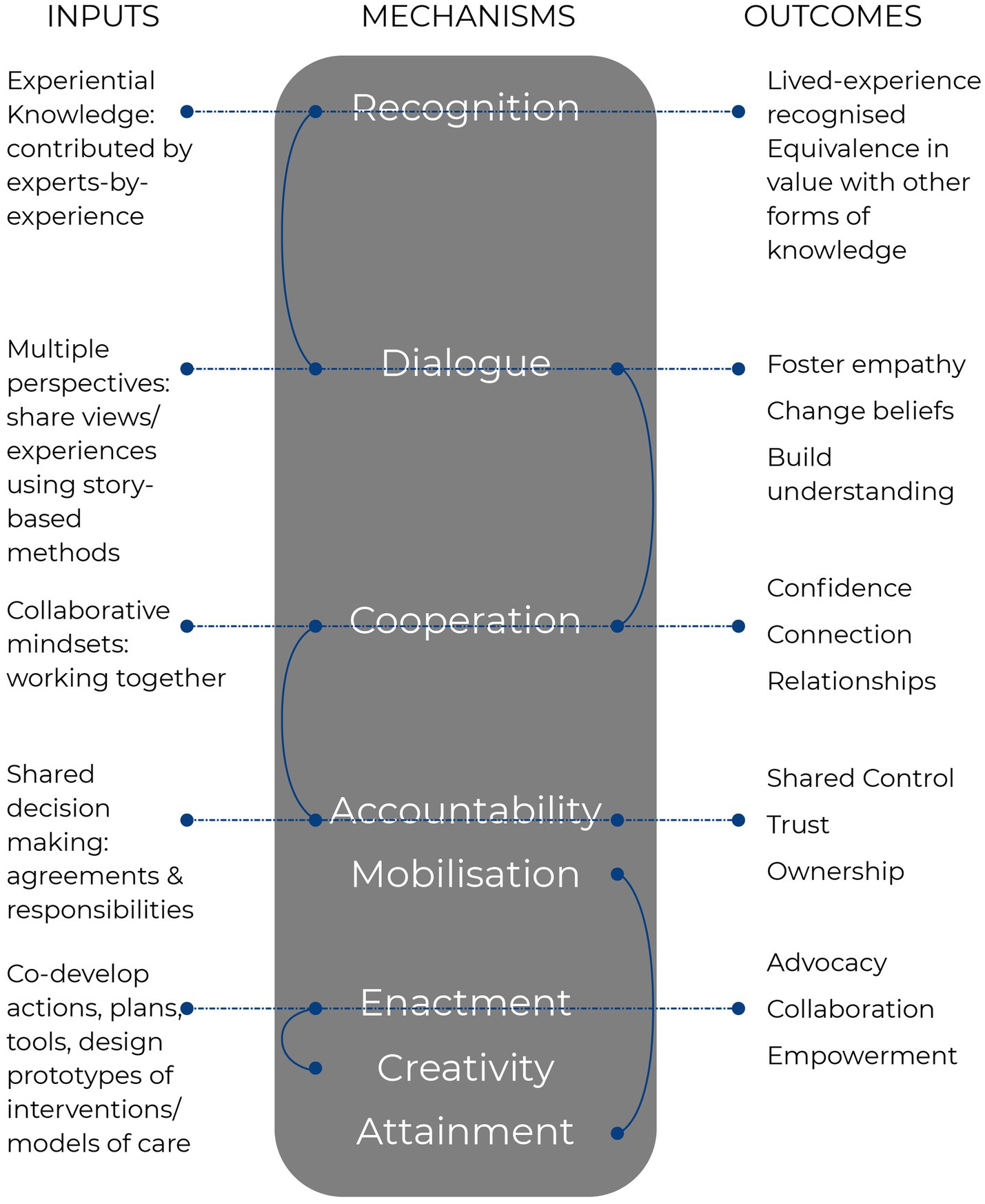

In the next section, we provide an overview of the evolution of the Co-Design Living Labs philosophy of practice called ‘togetherness by design.’ This philosophy of practice connects the ontology of our study (our ways of being together) with the epistemology of our study (how knowing shapes experiential knowledge and coproduced knowledge) and the doing (the practices for how we work together). Ideally, these ways of being, knowing, and doing shape ways of seeing through the implementation of the ideal relation of being-for (explained next). In Table 1, the component parts of the Co-Design Living Labs program, within which the philosophy of practice is operationalised, are detailed.

We describe the evolution of the program with reference to selected examples of co-design activities undertaken during 2017–2022; the full overview of co-design conducted between 2017 and 2022 is presented in Figure 2 also.

Figure 2. The evolution of end to end research design to translation activities in the co-design living labs program (2017-2022).

3 Results—development of a philosophy of practice “Togetherness-by-Design”

3.1 Ontology—ways of being

As noted earlier, the implementation of our philosophy of practice hinges on a specific commitment to ways of working and being together that draws on three forms of togetherness. These forms of togetherness were originally outlined by Zygmunt Bauman and drew heavily on the work of philosopher Emmanuel Levinas (22). Bauman described the forms as being-aside, being-with, and being-for. These are types of relations exist in our everyday worlds and can be practiced (and not practiced) between people. The three forms of togetherness provide the program with a guide to how we work collaboratively with co-designers and partners of our program.

To understand what is meant by the being-aside relation, it is helpful to think of a physical space that is shared between two parties or entities (beings). In this space, these entities may indeed be co-present, but there is no recognition by any of the entities that the ‘other’ is there, has any importance, or is even “person-like”. This relation can be seen, for example, when people get on and off public transport. There is shared space but no recognition of each other; we move aside and move on. Being-aside offers a way to understand inhumane engagements characterised by people occupying physical spaces aside from each other but not seeing or acknowledging the person, the identity, or experience (30). There is no sense of need for this recognition nor associated connection in being-aside relations. It leaves people feeling deeply isolated and disconnected from each other; unseen, unheard, and unknown. For this reason, being-aside is an important relation to be aware of in ways of working in co-design—it might even be said to be the antithesis of co-designing together.

In contrast, being-with relations advance beyond the reality of occupying space together towards some recognition that there are others around us. Unfortunately, in being-with relations, this recognition is based largely on interests. Being-with, according to Bauman and his use of Levinas’ notion of the Other, is an encounter of ‘no more than the topic at hand permits’, and once exchanges have been made, nothing more evolves or continues; no more of the self is given to the encounter than the transaction that underpins it. At a community level, being-with is played out at the shopping centre with short hellos, exchanges of money for products, and a departure from the setting without further thought given to the encounter or those within it.

The ideal form of togetherness, according to Bauman (22), is being-for, where people and beings are honoured as contributors to relationships regardless of the status they bring. In being-for, actions are always oriented towards a dialogical connection—that is, my story is connected with your story, but it is not my story to share, it is always incomplete, and I can never close this off. This is a relation we share in and should be seen as beyond individual one-to-one notions of engagement and expanded to communal worldviews. In Levinas’ conception of the Other, it is a totality that can never be entirely and fully known, but it is a relational connection that persists beyond time and space. For Bauman (drawing on Levinas), one must be for the Other before one can be with the Other (31). This means seeing the face of the Other and coming to share responsibility with each other.

As a philosophy of practice, togetherness by design enables the Co-Design Living Labs program activities to move from the transactional space of being-with to enact being-for as the relational goal from which we work together with co-designers and communities beyond the university. This contrasts with the way communities have traditionally been invited to participate in research, which has largely been more reminiscent of Bauman’s concept of being-with. Sadly, in some instances, being-aside has also characterised research endeavours where there has been active exclusion, avoidance, and lack of engagement with some communities. Togetherness-by-Design, with its orientation to being-for, also enables us to share unconditional responsibilities for and with each other.

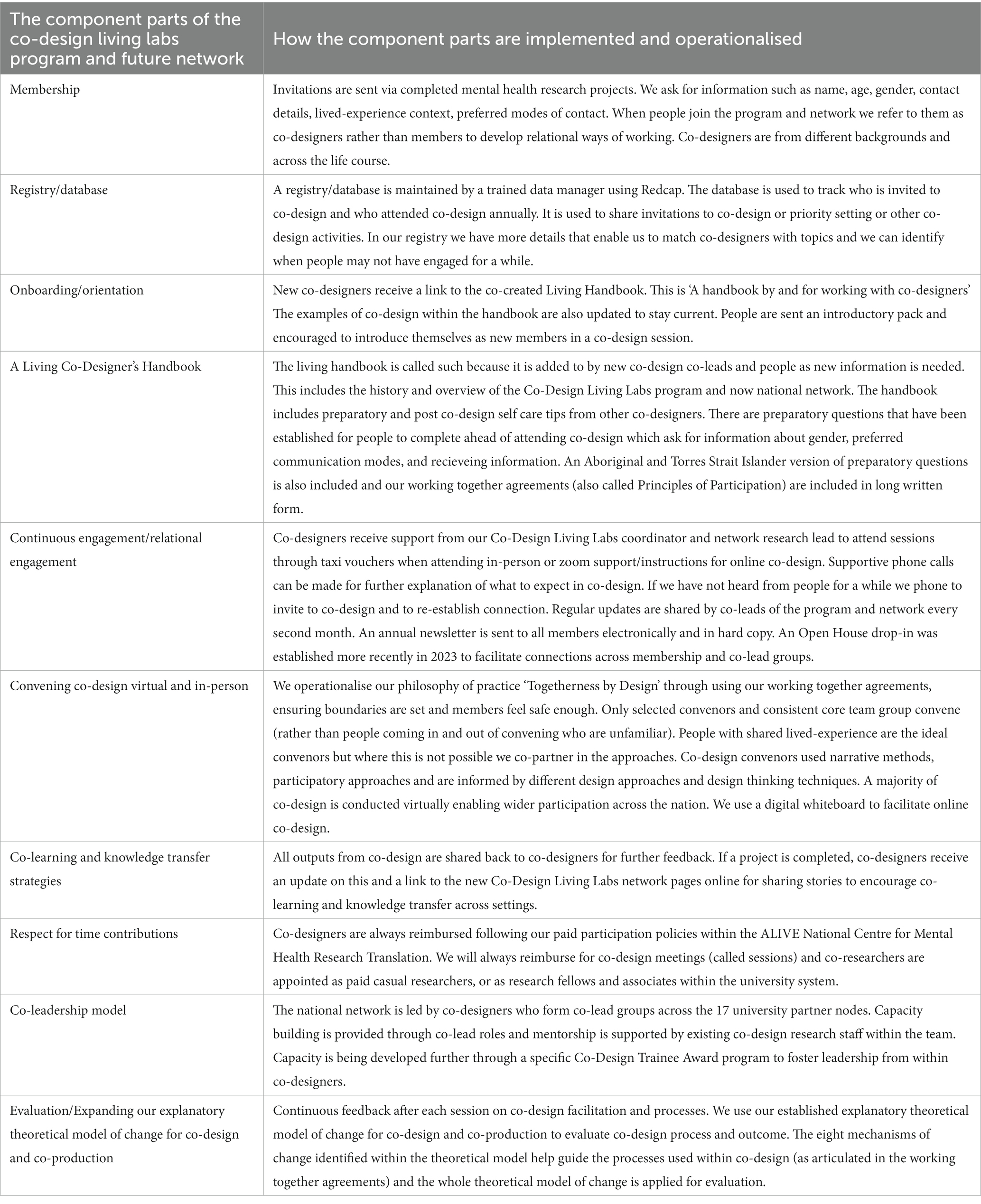

To create the conditions for change and a commitment to being-for, eight mechanisms of change are employed to set relations and evaluate Togetherness-by-Design. These mechanisms are presented in Figure 3 and have been adapted from an existing explanatory theoretical model of change for co-design and coproduction in healthcare improvement (1). The mechanisms have informed our working together agreements that we articulate in each co-design session for creating safety and shared understanding for co-design. Coupled with the theoretical model, these mechanisms can also be used to evaluate co-design processes and outcomes.

The Co-Design Living Labs philosophy of practice thus expands university–community relationships beyond transactional one-off research engagements where they are based on no more than the topic at hand permits (25). Evaluative evidence from 11 of the co-designers, who contributed to the development of the conceptual design for a digital service model for people with complex mental health needs (32), suggested that the practice of ‘Togetherness-by-Design’ does foster connections and dialogical relations consistent with the goals of being-for. The co-designers comprised both existing members within the program and people external to the program who were invited from partnered organisations also. The co-designers, when they were asked about the sessions, said: ‘people felt that the group members did not talk over each other, people did not have to compete to feel heard, everybody had a chance to talk, the group was accommodating of a diversity of experiences, the ways of working were open, respectful, and the activities using pictorial descriptions to talk about experiences and ideals were valued’. Co-designers who provided this feedback also added that, for them, ‘feelings of empowerment were fostered by their voices being heard, the engagement was enjoyable and met their hopes for coming to co-design’. The hopes people said that they had for engaging in the co-design included ‘the importance of being a part of solutions, creating positive change, creating better services and sharing experiences, and that a new set of ideas that others may not have thought of may emerge’. Importantly, the feedback included aspects of discomfort and challenges that co-designers had observed. Some co-designers sensed anger within the group, but the comments on this indicated that they remained comfortable expressing their discomfort around this without needing to close-off the anger or other person’s experiences. This illustrates the operationalisation of being-for as part of our togetherness as, despite conflict, the group managed to still see each other in all the forms of human expression and be in that together.

3.2 Epistemology—how knowing shapes experiential knowledge and coproduced knowledge

Togetherness-by-Design is further enacted by applying being-for to ways of knowing. Here, lived-experience is seen as a form of knowing that is essential to what is coproduced. The Co-Design Living Labs program has grown from following experience-based co-design in the early establishment phases to employing Togetherness-by-Design in its practices and processes. Originally established by Bate and Robert for service and quality improvement (33, 34), experience-based co-design (EBCD) commonly refers to two stages in a service or quality improvement process. Stage one is information gathering and stage two is co-design; these two stages are interconnected and integral to each other, so they should not be seen in isolation. What is important to highlight here is that the methods used to understand and elicit experience within experience-based co-design are deeply centred around narrative, participatory methods, and learning theory. Narrative is key as it centres on how socio-cultural contexts matter in identities and as a method; it values identity as central to the experience. Experience-based co-design enabled the program to enact being-for as a relation instead of falling to other methods where being-with might be the norm. An example of this might be in research activities where we ask for no more than the topic at hand permits. For example, structured surveys might be a case in point where often, when views have been exchanged in a question-and-answer format and submitted, the interaction is complete. The engagement is momentary and passes; nothing more occurs beyond this transaction, and often further interaction and engagement are discouraged in the style of survey administration. With experience-based co-design and its emphasis on narrative, we have fostered dialogical approaches to connect with peoples’ stories, identities, and values.

As indicated above, the Co-Design Living Labs program has therefore been shaped by narrative, learning theory, participatory, creative arts, and visual methods to elicit and shape experiential knowledge for co-design. This has ensured that experiential knowledge is key to what is made and shaped. The central focus on coproduced knowledge reflects the enactment of being-for as our relational way of working. The program also importantly builds on the living labs tradition of open innovation, collaboration, and partnerships across community, industry, and government to achieve this ideal (35, 36).

In the Co-Design Living Labs program, experiences, therefore, foreground and shape all activities, and our goal is for an epistemology that elevates experiential knowledge so that it is afforded what Fricker termed “epistemic justice” (37). In this respect, we are interested in how justice in the context of knowledge can be both discriminatory (how experience is valued, heard, and acted on, for example) and distributive (how goods are distributed, for example, through information sharing or education) (37). Justice also operates within the knowledge production processes of research and the institutional settings where it is carried out. Therefore, embedding co-designers within the leadership of the program and the now national network has been important as a strategy for the distribution of justice.

Our study indicates that experience is a fundamental first premise, and this is noted within the eight mechanisms of change (as presented in Figure 3) as essential for shifting to novel interventions and models of care that can facilitate lasting change. This means the experience drives not only what is improved in healthcare or other settings but also extends to what is researched, the research questions, and the research process from the study design to the translation processes; experience is embedded within the fabric of the program of study. This is shown in the Figure 1 model of operation. Although, critical measures of success must be about more than togetherness. They must necessarily move towards evaluating if the implementation of co-designed research projects and models of care is effective. The questions must be asked as to whether co-design results in structural and systemic shifts in power, addressing social injustices and ultimately creating better healthcare experiences and outcomes.

The Co-Design Living Labs program mirrors many elements of the arrival of the era of coproduced knowledge (38). This era of coproduced knowledge is seen as a push towards the valuing of experiential knowledge equally to that which is generated through medical and scientific positivist-focused research. Expertise based on experience has often been neglected due to the associations of subjectivity, the view that individual perspectives may be potentially biased and too subjective, and the complexity of experiential knowledge (39). Sociologist Borkman (40) referred to “experiential knowledge” in the 1970s as “the truth based on personal experience with a phenomenon.” Experiential knowledge is described as holistic and emerge from the multi-faceted and ongoing experiences of living with a particular condition or experience (41). Our philosophy of practice acknowledges that different forms of togetherness bring multiple ways of knowing; what is key is to share in the understanding of these for future change. This means honouring community-led lived-experience and ensuring this knowledge is at the heart of co-design practices.

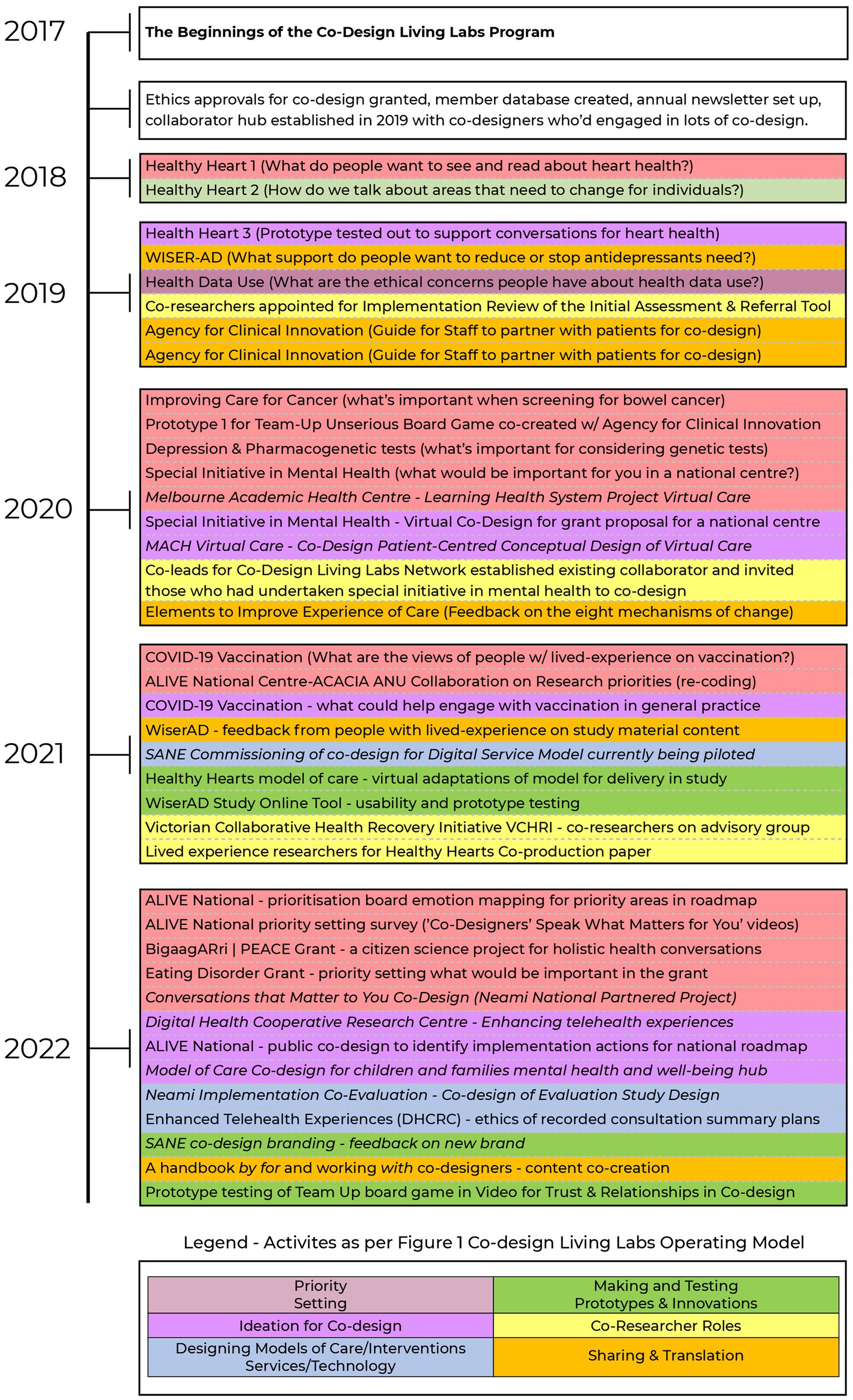

Our enactment of being-for to coproduce knowledge and new systems for implementation research was most recently demonstrated in the vision for the ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation, for which a short case story can be read here.1 Following the funding scheme being announced for the ALIVE National Centre, we sought to establish what the research priorities for our co-designers might be to ensure the grant proposal reflected the priorities of people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carer/family kinship groups. To do this, three open-ended questions were circulated to co-designers by email as follows:

1. What would be important to you in a national research centre dedicated to mental health research?

2. What are the main areas you think researchers should be looking at in mental health? What are the vital signs that we should be doing better in within mental health?

3. How would you like to be involved in a national centre, for example, would you participate in training activities for research, workshops about mental health research, meetings to network and grow expertise, or would you want to be trained to be a researcher?

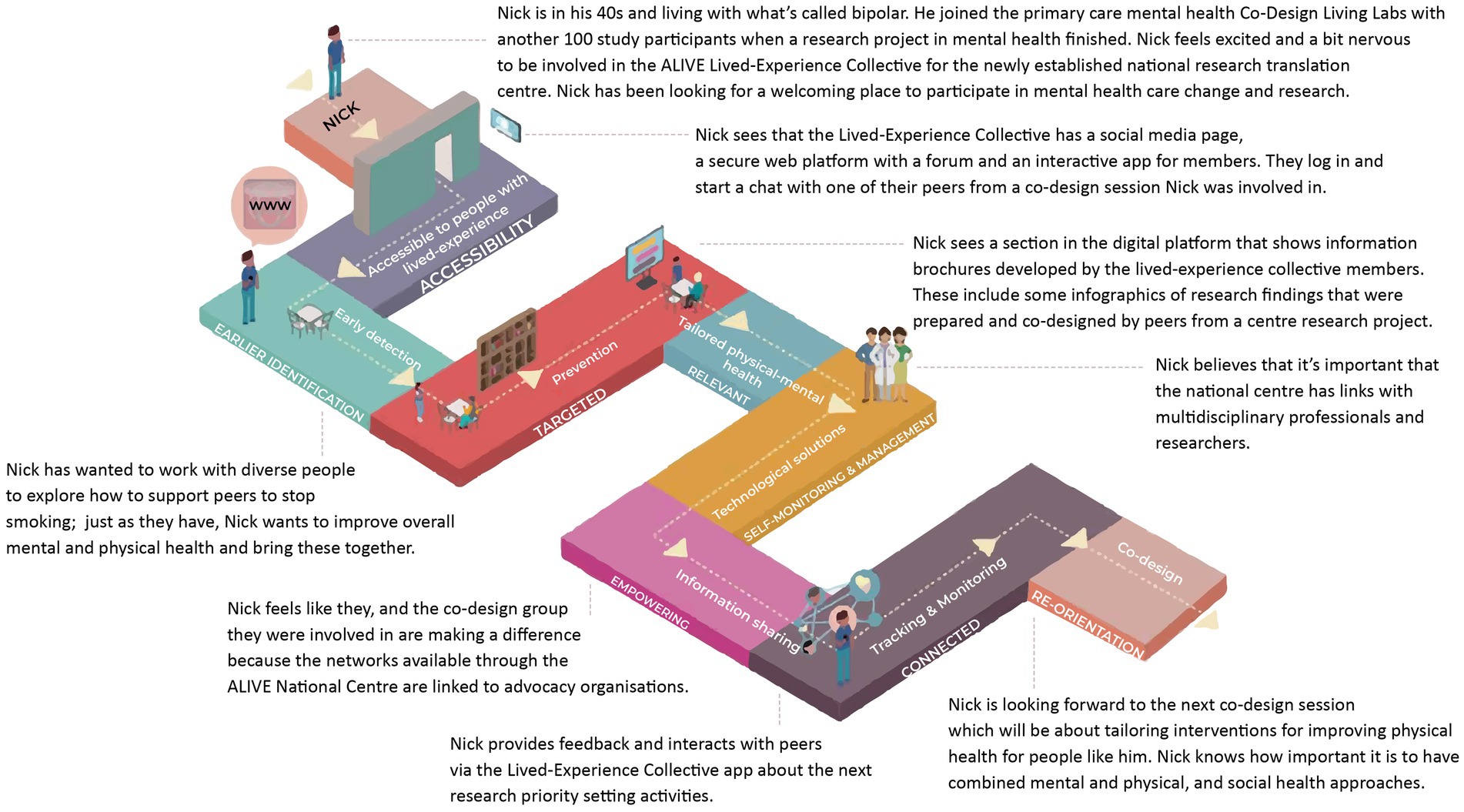

The email request was circulated for 2 weeks, and priorities were read by the lead for the Centre proposal (Palmer) and two researchers within the Primary Care Mental Health Research program. Responses were organised into thematic statements to formulate the research programs and their objectives. The overall experiential journey that someone with lived-experience of mental ill-health might have in the ALIVE National Centre was co-designed with 27 co-designers in three further ideation sessions. Of this group, eight co-designers were then named as co-leads within the grant proposal. Figure 4 presents how the thematic statements and priorities for research were translated into an ideal journey of a co-designer called Nick for the Centre’s proposal.

Figure 4. Conceptual design of the ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation research priorities and experiential journeys.

The pathway Nick takes shows the research priorities as the foundational blocks of the path and the experiential elements that were ideated on within co-design meetings along the top of the path. These experiential elements for the ALIVE National Centre included accessibility of services, early detection, prevention, tailored physical and mental health responses, technological solutions, for information sharing, tracking, and monitoring, and co-design. The research priorities (foundational blocks) were articulated similarly for the goals of delivering at-scale mental healthcare. The goals included accessibility, earlier intervention, prevention, targeted, relevant, self-monitoring and self-management, empowering, connected, and reorientation. Importantly, this is an assemblage of a range of people’s priorities and views constructed for grant purposes, and we note that experiences rarely ever mirror a neat linear path. The desired journeys articulated by people with lived-experience through the ALIVE National Centre are shared in the text as an example. This ideation and shaping of a Centre vision reflect coproduced knowledge in action whereby people with lived-experience have set out priorities and the experiential journey within the Centre, and this has subsequently been implemented within the Centre’s establishment and operationalisation.

3.3 Practice—ways of doing and undoing co-design

Ways of being and knowing that privilege being-for are critical to how we practice co-design in the program. We recognise that some existing tools and techniques for co-design need to be evaluated for whether they support these ideal relations (42). Currently, the processes and techniques within the Co-Design Living Labs program draw on participatory design practices, narrative approaches, participatory action research, visual methods, and creative arts-based methods (43). However, this still means that design methods need to be continuously re-evaluated and appropriate cultural framings applied. There must be a critical evaluation and expansion of the kind of co-design techniques and processes used. It is important to also implement ways of undoing co-design. For example, we critically evaluate whether personas are essential to the co-design processes given that there are risks of these being unintentionally stigmatising with stereotypical representations. To ensure cultural security and intersectionality is respected within co-design, all methods require rigorous evaluation and consideration of appropriateness for identities and existing knowledge systems—being-for the other precedes working together.

Implementation of Togetherness-by-Design has seen the program shift its language use from Co-Design Living Labs program members to ‘co-designers’, as explained in the introduction. This is an important signification of collaborative relationships, where power can ultimately be shared rather than represented as a member–researcher relationship, signalling a transactional value system. Researchers within the program have had to unlearn and shift beyond the terminology of research subjects or participants and see people as they are, as individuals who bring their life stories and experiences to support research design and translation activities. This has been an important step in moving from researcher-initiated processes to increasingly co-designer-led approaches. In valuing experiential knowledge and contributions, we therefore seek to recognise this in authorship practices and, in the longer term, in moving to a community-owned (social enterprise) model. The recognition of contributions and co-creation currently varies from the co-created pieces generated. Many co-designers prefer the use of first names only in some outputs to retain privacy or protect safety where they may be survivors of abuse, intimate partner and/or family violence. Some co-designers have become co-researchers within research teams and others also contribute actively to paper writing, editing and crafting work. Others are named on research grants as co-investigators and not solely as advisory group or committee members or as associate investigators which can be a dominant research practice. Co-designers are always reimbursed for their time contributions to co-design sessions—illustrating the importance of resourcing within the architecture and the component parts of the program (shown in Table 1). The role of the facilitators (or conveners) is to support engagement in co-development, to provide explicit frameworks, to share decisions and facilitate power-sharing arrangements, and to co-design and then use this to synthesise and develop either a set of design principles or a tangible artefact or model of care as required. At a deeper level, operating in a being-for relation also means changing our relational ways of connecting inwardly and outwardly for change to be sustained.

Co-design sessions have largely used whiteboards (digital whiteboards when virtual—a lot of co-design has been online since the COVID-19 pandemic onset in 2020). Experience and journey maps have been co-created and explored through facilitated group discussion, and final outputs were created by using emotion mapping within processes. The activities used within co-design sessions are usually selected to be matched with the co-design objectives and the experiences of people in the room; it is important to reiterate that our ways of doing are constantly in motion and changing. These reflect the evolutionary trajectory of the program over time. In current practices, many linear maps have been replaced with circular models reflecting how people with lived-experience engage in story-telling and sharing their experiences. Table 2 presents some greater detail of the adapted methods that were used within co-design sessions of the new digital service model for SANE Australia that the ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation conducted with an explanation of why these methods were used. These methods are overviewed in multiple articles but Milton and Rogers’ research methods in product design succinctly describes them (43). The table illustrates how these were adapted within our co-design approach.

Table 2. Ways of practice – examples of design activities used in the co-design of a conceptual model of care for a digital service model for people with complex mental health needs.

The commitment to co-creation and genuine/equal collaboration within the Co-Design Living Labs program extends to the data analysis stages of research and co-designed outputs, as well representing our being-for commitment to epistemic justice. To facilitate this, conceptual designs are shared with co-designers and expanded upon before delivery to partners. This is in keeping with fostering shared decision-making throughout co-design processes so that people are making choices about how input is configured and shared; this, in turn, embeds lived-experience at the heart of the conceptual designs and outputs. The Co-Design Living Labs program has ongoing ethics approval from the university human research ethics committee, which enables co-design to be responsive and iterative. This provides us with the capacity to run a continuous model of co-design to service the Australian mental health sector in the future and to embed lived-experience within research and improvement, re-design, and change efforts in implementation and translational research. Since we commenced in 2017, we have evolved working together agreements from our eight mechanisms of action (as noted in a previous section, and referred to as well as principles of participation), which are shared at the commencement of each co-design session (8). The eight mechanisms are part of an explanatory theoretical model of change that enables our program to enact continuous learning and evaluation of activities as well. Figure 3 details these adapted mechanisms within the program.

3.4 Ways of seeing—continuous learning and expansion of the program

The theoretical explanatory model of change enables documentation of experiential knowledge as a central driver in changing mental healthcare systems and to appreciate the concept of recognition as critical to change (44). It is important to also note that while the eight mechanisms appear neatly listed, they are not hierarchical and always remain interconnected—the intent is not for a usual program logic pathway that follows a, if this, then that, will result. In this respect, recognition and dialogue are critical to the shared understanding of narrative and storying, and the acknowledgement of polyphony (many voices) within co-design. Cooperation is then enacted through the sense of solidarity for communal causes, working together, and developing a shared agenda for making change. Accountability enables the shared agenda for change to grow through motivation as a group and agreeing to mobilise to make change happen. In this model, the co-development of actions must be accompanied by enactment of these actions with creative implementation to attain change. Actions without implementation lead only to more co-designed ideas without lasting change.

4 Discussion

The establishment of a Co-Design Living Labs program and the evolution of its philosophy of practice have been described in this paper. Using examples of co-design that have been undertaken, we have outlined the philosophy of practice for the program, Togetherness-by-Design. The key purpose of the Co-Design Living Labs program is to ensure that lived-experience is at the heart of mental health research, service design, delivery, improvement and evaluation, and research translation. Having recently celebrated its fifth year of operation, this article has shared the retrospective story of the evolution of the program. It has illustrated how Togetherness-by-Design is enacted across the model of operation by a commitment to being-for as an ideal relational ethic that shapes the ways of being, knowing, and doing in our work. The program architecture has resulted in component parts of the program that are fundamental to the realisation of our vision. These component parts have included a research-managed registry/database since inception, which has facilitated continuous replenishment of the membership base and coordination of activities in a structured approach. Having a coordinator to invite and support people to come to co-design, whether in person or virtual, has been a critical ingredient for togetherness. This is possibly because co-designers feel connected with and in a relationship with the research team. In addition, the registry/database has enabled focused engagement efforts as it is possible to see who might not have engaged and connect with people via telephone to hear more about what people would like to be engaged in.

As a successfully funded research program, there has been continued opportunity to grow the community base of co-designers, as reflected in the recent establishment of the Alex McLeod Co-Design Training Award in 2022. This award supports two co-designers per year (until 2022–2026) to hold paid part-time roles to learn about program operations and to grow co-design capabilities for future leadership. Our growth of a registry/database living labs approach ensures that much diversity can be reflected within end-to-end co-design. In the future, we will become a program that has membership across the life course and expands with an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-led component of study. Saying this, it is important to acknowledge that the Aboriginal-led program may have cultural practices and approaches that connect with, but are different from the current approaches. Additionally, there are always gaps and limitations within research structures and impositions on the conduct of activities that are funded. For example, research projects where co-designers have been recruited to date may have had specific eligibility criteria, which means that certain groups have been excluded due to the language requirements of those studies; thus, we must ask how to improve these situations. Ensuring that there is space for togetherness in these circumstances may require more attention as we move into the future. The program may not reach people who do not want to engage within what might be perceived as traditional research structures or who seek to represent their experiences in different ways to what is on offer. This is where co-partnership and relationships beyond the Co-Design Living Labs are key. As the Co-Design Living Labs network expands nationally, the membership base will necessarily need to reflect greater diversity for different local contexts. Currently, where gaps exist in the program, when we undertake co-design, we ensure that we co-partner with organisations to embed community-led approaches.

The Co-Design Living Labs engagements (or sessions) are typically short-term and entirely opt-in. We are conscious that there is potential to create high demand on people with lived-experience and carer/family and kinship group members around requests for co-design, and there are always risks of programs such as this being seen as service models—things that exist to serve other organisational needs. There will be a need to turn attention outward to explore how being-for is maintained as the ideal relation in these instances of collaboration. Given that government relationships are largely transitory and often replicate being-with as the primary relation, the opportunities for transformation from co-design will be limited. The registry/database provides the potential for the research team to manage invitations and for targeted in-reach to co-designers with specific expertise. The program also shows how it is possible to ensure community-led lived-experience is at the forefront of mental health research and that it can be embedded within traditional academic structures and work towards power-sharing despite known hierarchical systems. Saying this, however, it must be acknowledged that human resource systems are not well-designed in university contexts to support reimbursement of co-design activities and funding to ensure that participation is paid appropriately can be a challenge. When co-designers move into co-researcher roles, the pathways for engaging in research and career development are also poorly designed. The establishment of the Co-Design Living Labs program reflects how universities ought to aspire to engage not only with but with the relation of being-for communities. Being guided by Bauman’s (22) three forms of togetherness, the philosophy of practice Togetherness-by-Design supports a reorientation of research hierarchies in the process of working together and disrupts power-laden practices of who decides what is researchable and how this is undertaken. As the model expands and disrupts its own traditional structures with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-led research in focus in the ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation, being-for will be a critically important foundation to re-distribute power for community-led approaches (23). Ways of doing may simply need to become ways of undoing in some circumstances.

As all funding agencies increasingly implement the prerequisite for co-design with people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carers/family/kinship group members within grant proposals and research (18), and as health researchers increasingly dabble in co-designed interventions and digital health technologies, it is critical that the processes and methods used for co-design are better articulated, understood, and evaluated. One example of improving the information shared was recently provided by Knowles et al. (45) in a description of Public Patient Involvement (PPI) within a United Kingdom (UK) Learning Health System (LHS) project. In that article, the co-design questions, method, and proposed outcome were detailed within an overarching table to show rationales and intended outcomes; we have emulated this within our study in Table 2 to follow good practice. This is a positive first-step practice for health researchers who undertake co-design to include as part of the processes of describing interventions, model of care, or technology development. However, we must also be conscious of the need to couple this with detailed overviews of ways of working that articulate clear philosophies of practice so that the relational focus of co-design is not eroded, overlooked, and subsumed. Additionally, evaluative frameworks for the impacts and outcomes of co-design are required—this includes paying greater attention to whether structural and systemic injustices are remedied from co-designed research and how impact and outcomes might be measured. It also means acknowledging where change within established co-design programs of work might be needed in keeping with the dynamic, changing, and shifting nature of co-design more broadly. One theoretical model of change designed for evaluation has been presented within this article as useful to setting conditions for co-design, understanding processes, and evaluating for impact at individual, social, community, and organisational levels (1).

5 Conclusion

As the Co-Design Living Labs program moves from a local program model to part of a national network with the ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation, fostering capabilities within local university nodes will be important. The key characteristics of the approach, the dedication to relationship formation, and the commitment to Togetherness-by-Design as the philosophy of practice must remain front and centre. Feedback from co-designers has suggested that Togetherness-by-Design has supported the goals, values, and processes of co-design processes and outcomes. This indicates that Togetherness-by-Design helps to realise the mechanisms of change (recognition, dialogue, cooperation, accountability, mobilisation, enactment, creativity, and attainment) in co-design. This means shared values that facilitate relational ways of being, knowing, and doing and a full appreciation of the distinctions between non-relational and transactional ways of working (being-aside and being-with) with relational ways of togetherness (being-for) are even more important. The Co-Design Living Labs program represents one example of an adaptive and embedded approach for people with lived-experience of mental ill-health to drive mental health research design to translation, which can be delivered at scale. These approaches need to be embedded in architecture across research, government policy and practice, and service settings. As scaling commences, the emphasis on co-leadership from co-designers and the transition to a living labs cooperative social enterprise model will become key.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

VP conceptualised the establishment of the Co-Design Living Labs program using participatory design expertise and knowledge from the world first trial of adapted co-design for mental health settings they led and developed the philosophy of practice with input from co-designers over the life of the program. JB co-convenes co-design activities and leads research activities within the program and supports co-lead group meetings. ML has co-convened healthy hearts project related co-design sessions with VP and works regularly with ED who is a lived-experience co-researcher from the program. KD established the registry/database for the program using redcap and provides statistical updates on membership, participation and withdrawals. RK coordinates invitations to join the program and sessions within the program and supports KD for analyses. ED, PS, AD, BH, TS, ND, and GM are co-leads within the program (with an unnamed carer co-lead) who meet once a month to guide progression and activities of the national network and foster leadership within the program. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author team thanks Professor Jane Gunn for sharing the invitations (with ethics approval) to the diamond study participants (2003–2016) which was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (GNT299869, GNT454463, GNT566511, and GNT1002908) and the Victorian Centre for Excellence in Depression and Related Disorders, an initiative between Beyond Blue and the State Government of Victoria; the Target-D study (2014–2018) was funded by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (GNT1059863) and Link-Me (2017–2021) was funded by the Commonwealth Government Department of Health. The CORE study (2012–2017) was funded by the Victorian Government Mental Illness Research Fund and Psychiatric Illness and Intellectual Disability Trust Fund led by Professor Victoria Palmer.

Acknowledgments

The Co-Design Living Labs program research team is honoured to work with the near to 2000 people in the community who have lived-experience of mental distress, illness, mental ill-health, trauma, and accessing services for mental health support. Some of our members also identify as carers/family and kinship group members, and many express having experiences of both. The ongoing commitment to the program is what makes it succeed, and we are indebted to co-designers. The contributions of our co-design co-lead groups cannot be undervalued. For this study, the co-authors are the first round of co-design leads named on the ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation proposal, one of whom chose to remain anonymous. The others have been named co-authors on this study to reflect their contributions to what has evolved. The team expresses thanks to Dr. Caroline Tjung for the visual preparation of the Co-Design Living Labs program operational model and to Ms. Amy Coe for research support and thematic analysis of co-designer contributions to the ALIVE National Centre vision and the co-creation of Nick’s journey with Professor Victoria Palmer. Our thanks also go to the research leads of mental health studies who have enabled us to invite people from completed studies from within the Primary Care Mental Health Research Program (formerly the Integrated Mental Health Research Program) located in the Department of General Practice, Melbourne Medical School, The University of Melbourne. Special thanks to carer co-lead Bev Harding for approving the naming of the Co-Design Trainee Award in memory of Bev’s son Alex McLeod. Alex lived with mental ill-health and left the world far too young the year the ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation was funded.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

1. Palmer, VJ, Weavell, W, Callander, R, Piper, D, Richard, L, Maher, L, et al. The participatory zeitgeist: an explanatory theoretical model of change in an era of coproduction and codesign in healthcare improvement. Med Hum. (2019) 45:247–57. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2017-011398

2. Palmer, VJ. The participatory zeitgeist in health care: it is time for a science of participation. J Particip Med. (2020) 12:e15101. doi: 10.2196/15101

3. Faulkner, A. Survivor research and mad studies: the role and value of experiential knowledge in mental health research. Dis Soc. (2017) 32:500–20. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2017.1302320

4. Callard, F, Rose, D, and Wykes, T. Close to the bench as well as at the bedside: involving service users in all phases of translational research. Health Expect. (2012) 15:389–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00681.x

5. Okoroji, C, Mackay, T, Robotham, D, Beckford, D, and Pinfold, V. Epistemic injustice and mental health research: a pragmatic approach to working with lived experience expertise. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 14:1114725. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1114725

6. Williams, O, Sarre, S, Papoulias, SC, Knowles, S, Robert, G, Beresford, P, et al. Lost in the shadows: reflections on the dark side of co-production. Health Res Pol and Sys: BMC; (2020). 18:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-00558-0

7. Carras, M, Machin, K, Brown, M, Marttinen, TL, Maxwell, C, Frampton, B, et al. Strengthening review and publication of participatory mental Health Research to promote empowerment and prevent co-optation. Psychiatr Serv. (2023) 74:166–72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.20220085

8. Palmer, VJ, Chondros, P, Furler, J, Herrman, H, Pierce, D, Godbee, K, et al. The CORE study—an adapted mental health experience codesign intervention to improve psychosocial recovery for people with severe mental illness: a stepped wedge cluster randomized-controlled trial. Health Expec. (2021) 24:1948–61. doi: 10.1111/hex.13334

9. Steen, M. Co-design as a process of joint inquiry and imagination. Des Issues. (2013) 29:16–28. doi: 10.1162/DESI_a_00207

10. Sanders, E, and Stappers, P. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign. (2008) 4:5–18. doi: 10.1080/15710880701875068

11. Steen, M. Upon opening the black box and finding it full: exploring the ethics in design practices. Sci Tech Hum Values. (2015) 40:389–420. doi: 10.1177/0162243914547645

12. Leminen, S. Coordination and participation in living lab networks (November 2013). Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. (2013) 3:5–1.

13. Vaajakallio, K, and Lucero, A, editors. Co-designing mood boards: Creating dialogue with people. Proceedings of Third IASTED International Conference Human-Computer interaction, Innsbruck, Austria; (2008): ACTA Press.

14. Robert, G, Williams, O, Lindenfalk, B, Mendel, P, Davis, LM, Turner, S, et al. Applying Elinor Ostrom’s design principles to guide co-design in health (care) improvement: a case study with citizens returning to the community from jail in Los Angeles county. Int J Integr Care. (2021) 21: 7, 1–15. doi: 10.5334/ijic.5569

15. Government. Royal Commission into Victoria’s mental health system, final report, volume 1: A new approach to mental health and wellbeing in Victoria. Victoria: State government; (2021). Document 2 of 6.

16. Jones, N, Atterbury, K, Byrne, L, Carras, M, Brown, M, and Phalen, P. Lived experience, research leadership, and the transformation of mental services: building a researcher pipeline. Psych Serv. (2021) 72:591–3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000468

17. Loughhead, M, Hodges, E, McIntyre, H, Procter, NG, Barbara, A, Bickley, B, et al. A model of lived experience leadership for transformative systems change: activating lived experience leadership (ALEL) project. Leadersh Health Serv (Bradf Engl). (2023) 36:9–23. doi: 10.1108/LHS-04-2022-0045

18. NHMRC. Statement on consumer and community involvement in health and medical research. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council (2016).

19. McKercher, K. Beyond sticky notes: Co-Design for Real. Australia: Thorpe-Bowker Identifier Services (2020).

20. Waddingham, R. Mapping the lived experience landscape in mental Health Research. United Kingdom: NSUN and MIND (2021).

21. Blackdog Institute. Definition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander lived experience Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander lived experience Centre; (2023). Available at: https://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/education-services/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-network/ (Accessed October 13, 2023).

22. Bauman, Z. Life in fragments: Essays in postmodern morality. United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell Publishers (1995).

23. Wright, M, Culbong, T, Webb, M, Sibosado, A, Jones, T, Guima China, T, et al. Debakarn Koorliny Wangkiny: steady walking and talking using first nations-led participatory action research methodologies to build relationships. Health Sociol Rev. (2023) 32:110–127. doi: 10.1080/14461242.2023.2173017

24. Palmer, V. Narrative repair: [re]covery, vulnerability, service, and suffering. Illn Crisis Loss. (2007) 15:371–88. doi: 10.2190/IL.15.4.f

25. Garlick, S, and Palmer, VJ. Toward an ideal relational ethic: re-thinking university-community engagement. Gateways Int J Comm Res Engag. (2008) 1:73–89. doi: 10.5130/ijcre.v1i0.603

26. Yunkaporta, T. Sand talk: How indigenous thinking can save the world / Tyson Yunkaporta. Victoria: Text Publishing Melbourne (2019).

27. Schuurman, D, and Tõnurist, P eds. Innovation in the public sector: exploring the characteristics and potential of living labs and innovation labs, vol. 2016 OpenLivingLab Days (2016).

28. Hossain, M, Leminen, S, and Westerlund, M. A systematic review of living lab literature. J Clean Prod. (2019) 213:976–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.257

29. Zipfel, N, Horreh, B, Hulshof, C, de Boer, A, and van der Burg-Vermeulen, SJ. The relationship between the living lab approach and successful implementation of healthcare innovations: an integrative review. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e058630. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058630

30. Palmer, V. [un]feeling: embodied violence and dismemberment in the development of ethical relations. Rev J Polit Philos. (2008) 6:17–33.

32. Australia, S. Welcome to SANE's guided service Australia: SANE Australia; (2022) [How was the guided service developed?]. Available at: https://www.sane.org/get-support/guided-service.

33. Bate, P, and Robert, G. Experience-based design: from redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Qual Saf Health Care. (2006) 15:307–10. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.016527.

34. Bate, P, and Robert, G. Bringing user experience to healthcare improvement: The concepts, methods and practices of experience-based design. United Kingdom: Radcliffe Publishing (2007).

35. Bergvall-Kåreborn, B, Eriksson, C, Ståhlbröst, A, and Svensson, J, editors. A milieu for innovation: Defining living labs. ISPIM innovation symposium: 06/12/2009–09/12/2009; (2009).

36. Leminen, S, Niitamo, VP, and Westerlund, M. (Eds.). A brief history of living labs: From scattered initiatives to global movement. Proceedings of the research day conference; (2017).

37. Fricker, M. Epistemic justice as a condition of political freedom? Synthese. (2013) 190:1317–32. doi: 10.1007/s11229-012-0227-3

38. Palmer, V. Through the looking glass: Or, Alice's foray into the qualitative world looking for a new paradigm [keynote presentation]. International qualitative methods conference July 8, 2021. (2021).

39. Byrne, LHB. Reid-Searl K. Lived experience practitioners and the medical model: World's colliding? J Ment Health. (2016) 25:217–23. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1101428

40. Borkman, TJ. Experiential knowledge: a new concept for the analysis of self-help groups. Soc Serv Rev. (1976) 50:445–56. doi: 10.1086/643401

41. Borkman, TJ. Experiential, professional and lay frames of reference In: T Powell, editor. Working with self-help. Silver Spring, MD: National Association of Social Workers Press (1990). p. 3–330.

42. Fletcher, G, Waters, J, Yunkaporta, T, Marshall, C, Davis, J, and Manning, BJ. Indigenous systems knowledge applied to protocols for governance and inquiry. Syst Res Behav Sci. (2023). 40:757–760. doi: 10.1002/sres.2932

43. Milton, A, and Rogers, P. Research Methods for Product Design. United Kingdom: Laurence King Publishing (2023).

44. Ricoeur, P. The Course of Recognition. Vienna: Institute for Human Sciences Vienna Lecture Series (2007). p. 320.

Keywords: experience co-design, co-design, living labs, lived-experience, mental health, research design, implementation, mental health research translation

Citation: Palmer VJ, Bibb J, Lewis M, Densley K, Kritharidis R, Dettmann E, Sheehan P, Daniell A, Harding B, Schipp T, Dost N and McDonald G (2023) A co-design living labs philosophy of practice for end-to-end research design to translation with people with lived-experience of mental ill-health and carer/family and kinship groups. Front. Public Health. 11:1206620. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1206620

Edited by:

Evdokimos Konstantinidis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, GreeceReviewed by:

Gareth Priday, Swinburne University of Technology, AustraliaSonja Pedell, Swinburne University of Technology, Australia

Copyright © 2023 Palmer, Bibb, Lewis, Densley, Kritharidis, Dettmann, Sheehan, Daniell, Harding, Schipp, Dost and McDonald. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Victoria J. Palmer, di5wYWxtZXJAdW5pbWVsYi5lZHUuYXU=

Victoria J. Palmer

Victoria J. Palmer Jennifer Bibb1,2,3

Jennifer Bibb1,2,3 Matthew Lewis

Matthew Lewis Konstancja Densley

Konstancja Densley