- 1Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

- 2Department of Pediatrics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

- 3Office of Student Health and Wellness, Chicago Public Schools, Chicago, IL, United States

- 4Sinai Urban Health Institute, Chicago, IL, United States

Introduction: While schools represent key venues for supporting health, they continue to experience gaps in health resources. The integration of community health workers (CHWs) into schools has the potential to supplement these resources but has been underexplored. This study is the first to examine perspectives of experienced CHWs about how CHWs can be applied in school settings to support student health.

Methods: This qualitative study involved conducting semi-structured interviews focused on implementation of CHWs in schools with individuals who held positions aligned with the CHW scope of work. De-identified transcripts were analyzed, and codes were organized into domains and themes.

Results: Among 14 participants, seven domains emerged about the implementation of CHWs in schools: roles and responsibilities, collaborations, steps for integration, characteristics of successful CHWs, training, assessment, and potential challenges. Participants shared various potential responsibilities of school-based CHWs, including educating on health topics, addressing social determinants of health, and supporting chronic disease management. Participants emphasized the importance of CHWs building trusting relationships with the school community and identified internal and external collaborations integral to the success of CHWs. Specifically, participants indicated CHWs and schools should together determine CHWs' responsibilities, familiarize CHWs with the school population, introduce CHWs to the school community, and establish support systems for CHWs. Participants identified key characteristics of school-based CHWs, including having familiarity with the broader community, relevant work experience, essential professional skills, and specific personal qualities. Participants highlighted trainings relevant to school-based CHWs, including CHW core skills and health topics. To assess CHWs' impact, participants proposed utilizing evaluation tools, documenting interactions with students, and observing indicators of success within schools. Participants also identified challenges for school-based CHWs to overcome, including pushback from the school community and difficulties related to the scope of work.

Discussion: This study identified how CHWs can have a valuable role in supporting student health and the findings can help inform models to integrate CHWs to ensure healthy school environments.

1. Introduction

Childhood chronic conditions have become more prevalent within the past five decades (1). Youth who identify as non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic or from low socioeconomic backgrounds are at greater risk for developing chronic health conditions and experiencing greater morbidity (2, 3). Along with negative health outcomes, children with chronic illnesses are more likely to have lower educational achievement as compared to those without them (4). Further, childhood chronic conditions are associated with increased morbidity and mortality in adulthood (5). Thus, it is essential for children with chronic illnesses to have access to healthcare, especially for vulnerable groups.

Outside of the healthcare system, schools—where youth spend a majority of their waking hours—are recognized as importance venues to promote a culture of health by providing chronic disease management and preventive services to students (6). Impacts of school-based health services include improvement in academic performance, increased access and utilization of health services, as well as better management of health conditions among students (7, 8). Such services are crucial to health, however, many US schools are unable to provide comprehensive health services, including screening, treatment, and linkage to community-based resources, due to school nurse shortages and unsustainable health programming (9, 10). School nurses play an important role in fostering the wellbeing of the school community, including offering direct care to students, educating students on health, conducting health screenings and referrals, leading school health policies, and managing the system of care within schools (9, 11). However, the majority of school nurses work in multiple schools with a ratio of one nurse for every 950 students, impacting their workload (12). Additionally, 11.4% of public schools have no school nursing (9). Other barriers to sustainable health programming in schools include insufficient resources, such as limited funding as well as a lack of knowledge and confidence among teachers when delivering health education outside their typical expertise (10).

To address the deficiencies in school health services, the integration of community health workers (CHWs) into school settings can support student health and foster a culture of health within school communities (13). Community members and/or individuals who possess a thorough understanding of the community can become CHWs who serve as culturally competent liaisons between health and social services and the community (14), supporting education, counseling, navigation, and advocacy (15). CHW programs have been utilized globally to address health disparities within clinical and community settings (16–19). Within clinical settings, CHWs support clinicians to tailor care through their unique connections with patients to understand their needs and situation (20). Within community settings, CHWs provide health education and connect community members to local health and social services (15). Such CHW interventions have shown positive outcomes, including improving chronic health management among adults (21, 22) and children (21, 23–26), connecting clients to resources (27, 28), and promoting healthy behaviors (17, 29).

Although there is strong evidence for the positive impact of CHWs and the CHW workforce is expanding (30), the implementation of CHW interventions in schools has been underexplored (31). This study is the first to examine the perspectives of experienced CHWs about how CHWs can be integrated and utilized in US school settings to work as part of school-based health teams to support student health and healthy school environments. Although CHWs have been integrated in a few US schools and school-based health centers (32, 33), it remains an uncommon practice globally that requires guidance, particularly from the perspective of seasoned CHWs.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This qualitative study was carried out within an academic-community partnership between an academic medical center, public school district, and community-based research institute in Chicago. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with experienced CHWs regarding the integration and implementation of CHWs in the school setting. It focused on CHWs serving the Chicagoland area as the findings would inform program implementation in Chicago schools. This study was deemed exempt by University of Chicago's Institutional Review Board (IRB21-1786).

2.2. Population

Participants were individuals who had work titles or positions that aligned with the CHW's scope of work. Participants were recruited through emails disseminated within CHW-focused organizations and networks in the Chicagoland area. Interested individuals contacted the study team directly and were asked to confirm their work background and/or training to qualify for the study. This study utilized snowball sampling with participants asked at the end of their interview to recommend other potentially eligible CHWs.

2.3. Data collection

One-on-one interviews were conducted and audio-recorded via Zoom between January and April 2022. All interviews were conducted by a research project coordinator with a master's degree in public health and four years of qualitative methods experience. The coordinator was employed by the academic medical center and did not have any influence on the CHWs' employment or programs. Verbal consent was obtained prior to the start of interviews.

An interview guide was utilized with questions under six key topics: potential roles and responsibilities of CHWs in schools, qualities and skills needed for CHWs in schools, collaborations within the school community, preparation for integration, methods for assessing the intervention, and challenges CHWs in school may face. Each interview lasted 60–120 min. Participants received $50 e-gift cards for completing the interview. Interviews continued until data saturation was reached. Interviews were transcribed and de-identified by the coordinator to maintain anonymity.

2.4. Data analysis

Interview transcripts were analyzed using inductive reasoning with thematic analysis based in grounded theory (34, 35). For the first five interviews, four research team members (AV, LG, MK, NY) independently read and coded one interview at a time and then met to compare codes and resolve discrepancies through discussion. Codes from the first five interviews were organized into themes and domains, with domains adapted from the interview guide's key topics. This framework was applied by three researchers (LG, MK, NY) to the remaining interviews, with themes further refined through iterative discussions. Once the final thematic framework was developed, all transcripts were re-coded by two researchers per interview. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Dedoose software (Version 9.0.46) was used for analysis.

3. Results

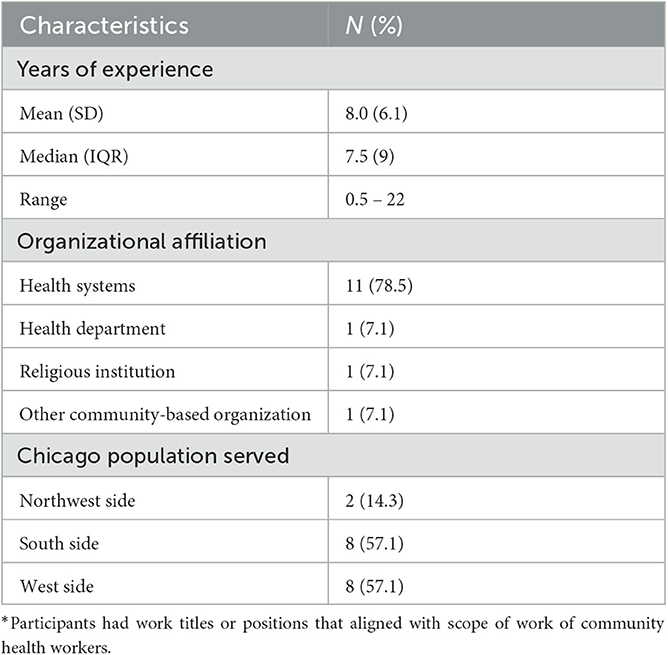

Fourteen individuals participated in the study (Table 1). Titles varied, including CHW, CHW supervisor, communicable disease investigator, and COVID-19 response worker. Participants had a mean of 7.5 years of experience (range = 0.5-22 years). The majority of CHWs worked within health systems (n = 11, 78.5%) and served populations in Chicago's west side (n = 8, 57.1%) and south side (n= 8, 57.1%).

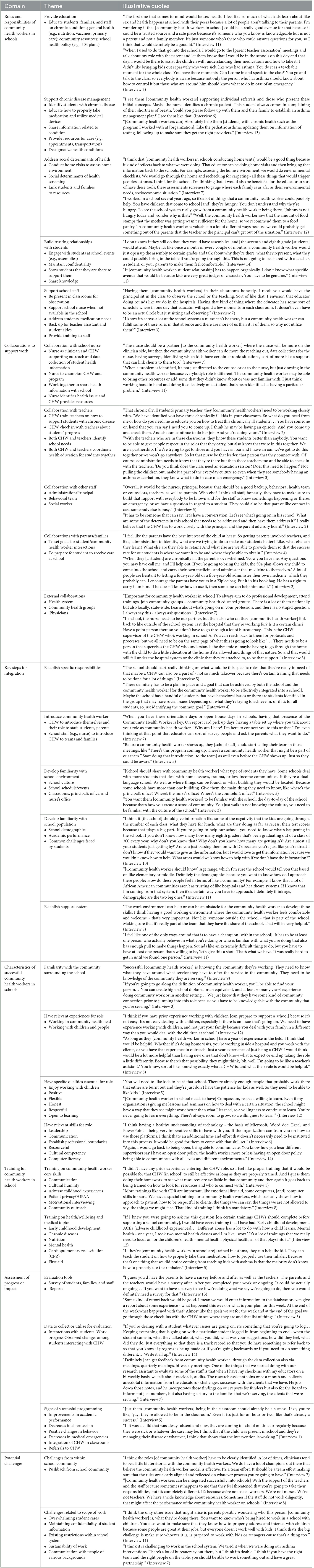

Seven domains emerged for incorporating CHWs in schools: roles and responsibilities of CHWs in schools; collaborations to support work; key steps for integration; characteristics of successful CHWs; training for CHWs in schools; assessment of progress or impact; and potential challenges (Table 2).

Table 2. Domains, themes, and quotes from experienced community health workers (CHWs) about CHW integration in schools.

3.1. Roles and responsibilities of CHWs in schools

Participants identified various responsibilities that school-based CHWs can perform to strengthen health promotion in schools, including educating school communities about health, addressing social determinants of health affecting students and families, supporting chronic disease management among students, supporting school staff, and building trusting relationships.

Participants emphasized CHWs' main role is to support the school community. They described a key responsibility to educate students, families, and staff about health, including chronic health conditions, general health (e.g., nutrition, vaccinations), and school health policies. Participants suggested that CHWs can also address social determinants of health among students and families through screenings, home visits, and linkages to health and social resources. One participant shared: “Johnny [a student] is not hungry today and wonder why? The CHW saw that the amount of food stamps the mother was getting wasn't sufficient for the home, so recommended them to a food pantry.” Additionally, participants described how CHWs can serve as resources for students with chronic health conditions through education, linkage to resources and care, and advocacy for students to properly manage their condition(s) at school with section 504 plans. For example, participants stated that CHWs can teach all students about specific health conditions. One participant explained, “You do it as a teachable moment. You talk to the class so everybody is aware because not only the person who has asthma should know about how to control it, but those around him should know what to do in an emergency.”

Along with supporting students and families, participants shared CHWs can support school staff including nurses and teachers. For school nurses, CHWs can assist with responsibilities that do not require licensing (e.g., administrative work). One participant said, “The educator [CHW] and the nurse should be partner[s]. The nurse will be more on the clinician side, then the CHW can do the reaching out, data collections for the nurse, identifying which kids have certain chronic situations.” Participants highlighted that supporting school nurses can involve fostering communication, tracking student health data, and reviewing medication management plans with students. Additionally, they suggested CHWs can support teachers by visiting classrooms and monitoring students for health emergencies. For students with chronic health conditions, CHWs could educate teachers about supporting these students and responding to health emergencies.

For CHWs to support the school community, participants indicated it is important for CHWs to build trusting relationships, especially with students. Methods cited for organically developing relationships with students and staff include having a consistent presence, maintaining confidentiality, and sharing knowledge. One participant suggested, “Maybe it's once a month or every couple of months, a CHW would open up the assembly to certain grades and talk about why they're there, what they represent, what they could possibly bring to the table.”

3.2. Collaborations to support work

Collaborations with school staff, parents/guardians, and external organizations were identified by participants as critical for enabling CHWs to successfully encourage healthy environments within schools.

Participants recommended CHWs work closely with school staff to address student needs and build a culture of health in schools. They described a partnership with the school nurse in which both collaborate to identify and address health issues among students, such as through communication between students, parents, and school nurses facilitated by CHWs; care provided by the school nurse; and resources identified by the CHW. Additionally, participants indicated school nurses can play a critical role in CHW integration by introducing the role to the school community. One participant explained, “A CHW needs a vehicle to get into the space. The most logical part is the nurse. The nurse introduced them and said, ‘This is the CHW. When I'm not here, this is your go-to person.”'

Along with the school nurse, participants suggested a collaboration between teachers and CHWs, since “teachers who are in these classrooms know students better than anybody,” as one participant said. Such collaboration could entail coordinating health education for all students and supporting students with chronic conditions. Participants also emphasized the importance of CHWs working with all school staff (e.g., administration, behavioral health team) to better understand their role and how to maximize their work in addressing school needs. The CHW can train all staff to identify students' health needs and respond to medical symptoms or emergencies. One participant stated, “[CHWs] have to make sure to build that rapport with everybody to be known and for the staff to know something's happening or there's an emergency, or we have a question in regard to a student.”

Participants also highlighted an essential collaboration with parents/guardians of students with chronic health conditions. Participants envisioned CHWs learning from parents about children's needs and setting goals together. Additionally, they suggested CHWs can work with parents to understand policies that support their children's right to manage their condition at school. One participant shared, “For a healthy environment, the parent and school know from the 504 plan and IEP things this kid is allowed to do. One of my biggest issues was that teachers did not want to take out time of a lesson to give a treatment. [CHW] will help support the laws and the benchmarks that [school district] has.”

Outside of the school community, participants proposed CHWs develop external collaborations with health systems and community organizations. These collaborations would serve dual purposes – to expand resources to the school community and to support CHWs' ongoing professional development.

3.3. Key steps for integration

Participants identified specific steps that would be needed to successful integrate CHWs in schools: establish responsibilities of CHW, familiarize CHW with the school environment and population, introduce CHW to the school community, and establish a support system for CHW.

Participants expressed that expectations of CHWs should be well-established before the program's start. These expectations may depend on students' needs, as one participant shared, “Maybe the school has a handful of students that have behavioral issues or students identified in the group that may have social issues. Depending on what they're trying to achieve in [working with CHW], or if it's for all students, so just identifying the common goal.” To identify CHWs' responsibilities, participants stated it is important for the CHW to understand the school community and its needs. They advised CHWs should familiarize themselves with the school, including existing health programs, policies, and culture, and the student population, including demographics, academic performance, and needs. One participant stated, “[The school] should give information like the negativity the kids are going through, the number of each class, what they have for lunch, what are they doing as far as recess, their test scores. If you're going to help our school, you need to know what's happening in the school.” Some participants suggested CHWs can perform a needs assessment to identify needs and risk factors of students, parents, and school staff, which can inform CHWs' responsibilities and priorities.

Participants indicated it is also important for CHWs to be introduced to school staff, students, and parents during integration. Participants suggested CHWs join staff meetings and parent-teacher conferences to build relationships within the community, as such introductions help establish trust and awareness of the CHW role as well as enable CHWs to gain more familiarity with the school community. One participant elaborated, “When you have these orientation days or open house days in schools, having that presence of the CHW is key. That educator can survey people and ask the parents what they want to do.” Participants also recommended school leaders and nurses take initiative to introduce CHWs to their teams to integrate CHWs into the school setting more seamlessly. Participants recognized that it is important for CHWs to be part of teams and acknowledged within schools for their work to be effective. “You have to have a champion,” said one participant. “It has to be at least one person who believes in what you're doing or who is familiar with what you're doing that also has enough pull to make things happen.”

3.4. Characteristics of successful CHWS

Participants identified four key characteristics that CHWs should possess to positively impact school communities: (1) familiarity with the community surrounding the school, (2) related work experience, (3) essential professional skills, and 4. specific personal qualities.

Participants stressed CHWs should be knowledgeable about the community surrounding the school, including demographics and nearby resources. “[Success] is knowing the community they're working,” said one participant. “They need to know what they have around, what service they have to offer the service to the community.” Having a connection to the community prior to beginning the CHW position, such as being a member of the neighborhood, was reported as useful. Also, participants indicated it was important for CHWs to have prior work experience in community health and/or with people. Previous experience and confidence working with children is valuable, particularly as CHWs support students during formative years of social, physical, and cognitive development. One participant stated, “What you do with a student can be lifelong. When you get the experience of dealing with different temperaments, different cultures, different things that students have gone through, it just prepares you better.”

In addition, participants highlighted several professional skills and personal qualities necessary for serving in schools. Relevant skills included leadership, communication, resourcefulness, problem-solving, and reliability. Participants reported CHWs should also be culturally competent, specifically approachable, non-judgmental, and able to communicate effectively with others from different backgrounds. Computer literacy was also identified as valuable, with proficiency in programs like spreadsheets and presentations useful for tracking progress. Because community health work can be emotionally challenging, participants emphasized the importance of self-care and the ability to maintain professional boundaries. Additional personal characteristics mentioned were positivity, flexibility, honesty, respect, compassion, and willingness to learn. Participants also emphasized CHWs should enjoying working with children. One participant said, “You will need to like kids to be at that school. There [are] already enough people that work there that either are burnt out and they're just don't have the patience for kids.”

3.5. Training for CHWs in schools

Participants discussed the importance of training to equip CHWs with the knowledge and skills necessary to provide CHW services in schools, focusing on two primary areas: core skills and health/medical topics. They suggested training can be delivered through different methods, including online modules and shadowing.

Participants identified core skills training should include communication, de-escalation, cultural humility, and patient privacy. Additional skills cited as important were motivational interviewing, community outreach, resource identification, and evaluation. Depending on students' ages, participants recommended that CHWs be prepared to work with children, including training in early childhood development and adverse childhood experiences. One participant described, “[Make] sure that the CHW is trained to be in the environment that the facility wants them to be in. So if there's early childhood, learn how to deal with a child.”

Participants also voiced that training on varied health-related topics should be required to enable CHWs to focus on relevant aspects of student health. They stated CHWs should be trained in general health topics (e.g., nutrition, mental health) and chronic diseases prevalent at the school (e.g., asthma, diabetes), so they are prepared to help students with those conditions manage their care. One participant summarized, “We're talking about students, so anything that has to do with behavioral issues, how health issues affect children in school, how does it affect their learning depending on what the health issue is, how you approach children who are dealing with certain health issues, anything that opens the door for better understanding, better communication, better ways to be able to deal with students in an open environment.” Furthermore, participants advised school-based CHWs should know first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in case of emergencies.

3.6. Assessment of CHW impact

Participants shared their recommendations for assessing the impact of CHWs on school communities, including evaluation tools, data collection, and indicators of success.

Participants proposed conducting surveys to obtain feedback from the school community on the quality of CHW services. They identified the utilization of CHWs as an additional indicator of success, such as in-house referrals to CHWs and the inclusion of CHWs in classrooms. Beyond survey and utilization data, participants suggested monitoring academic and health indicators of successful programming. For example, they described CHWs' positive impact may be signaled by changes in student outcomes such as improved academic performance, decreased absenteeism, favorable behavioral changes, and fewer medical emergencies.

Participants also recommended CHWs collect both quantitative and qualitative data when recording progress. For example, CHWs can document general feedback and details of their student interactions, as one participant explained: “Keep everything that is going on with a particular student logged in from beginning to end – when the student came in, what they talked about, what you did, what was your suggestions, how did they feel, what did they do. So you have something to refer back to so that you know if progress is being made or if you need to do something different.” Participants suggested online databases can be used to track weekly progress and inform follow-up with students as necessary. To summarize the work and impact of CHWs, participants communicated that CHWs can compile formal reports to share with school administrators and program evaluators using data from surveys, documentation, and school outcomes.

3.7. Potential challenges

Participants anticipated school-based CHWs may need to overcome challenges in their role arising from within the school community or related to their scope of work that could hinder their integration.

Participants identified a major challenge to successfully integrating CHWs into schools may be pushback from the school community. Specifically, existing school staff may perceive CHWs as threats to their own positions, and parents may be wary of having an unknown person work with their children. To address this challenge, participants suggested that CHWs be prepared to explain their role and communicate their qualifications. One participant explained: “Just be open. Be transparent and be willing to answer questions. Just say, ‘I'm here to partner with you in this process because we have the same common goal to make sure the student is taken care of and is healthy in mind, body and spirit.”'

Participants also shared that CHWs may face challenges related to their scope of work, such as communicating with people of various backgrounds and maintaining student confidentiality while being a mandated reporter. Other potential challenges related to CHWs' scope of work included overwhelming numbers of student cases, emotional toll of difficult situations, and existing limitations within school systems (e.g., funding, resources). Participants stressed CHWs should rely on their support system (e.g., colleagues, supervisors) and other resources (e.g., mental wellbeing trainings) to overcome these challenges.

4. Discussion

This study is the first to describe the perspectives of experienced CHWs about the potential roles and impact of CHWs in schools. Much of the existing literature focuses on CHWs in clinical or community settings, rather than in schools. This study explores important considerations for integrating CHWs in schools to support student health and healthy school environments.

The proposed services for CHWs in schools in this study are consistent with literature exploring CHW roles in other settings. Studies describing CHWs in primary care settings found they commonly conducted health assessments, made connections to community resources, and provided health education and coaching (20, 36, 37). Literature on CHWs in community settings reported similar responsibilities as in primary care, including advocacy for clients' health and linkage to health care services (38, 39). Participants in this study detailed additional responsibilities specific to school settings, such as education on school health policies and guidance to all school community members–not solely individuals with health conditions–about responding to health emergencies. While few studies have detailed the responsibilities of CHWs in school-based programs, a systematic literature review of CHWs in schools observed the majority of interventions reported positive outcomes, with nearly all successful interventions involving CHWs providing health education or coaching to students (13). Other research has identified needs within schools that CHWs can address; for example, one study showed school staff and parents viewed each other as responsible for providing nutrition education to students (40). CHWs can fill this role and empower both school personnel and parents to support healthy behaviors among students (41).

Successful programming in schools is a multifaceted process that includes developing collaborations. Participants in our study highlighted the importance of CHWs partnering with school nurses. Literature has identified CHWs and school nurses share overlapping goals, including providing care coordination and bridging gaps between healthcare and education (42). By leveraging their unique trainings and skills, CHWs and school nurses can complement each other to deliver health education as well as perform health screenings and contact tracing to prevent infectious disease spread (42). Both this study and prior research recommend that CHWs working with children also collaborate with parents to address social determinants of health (38). Whereas participants in this study stressed the importance of external collaborations to expand resources and support professional development, existing literature further highlights how relationships with local organizations can enable CHWs to reach more individuals and increase awareness of CHW services within communities (43).

To effectively integrate CHWs into schools, prior literature has emphasized the importance of having a champion for the CHW program, aligning with participants' recommendation to establish support systems (44). This study primarily focuses on actions that CHWs can take for successful integration, while previous literature concentrates on how other individuals can prepare to work effectively with CHWs (44). Specifically, it is important to inform clients about CHWs to increase their readiness to utilize these services. In school settings, this is akin to participants' suggestion that school leaders disseminate information about the CHW to the school community. Such introductions are important to prepare school members to optimally utilize the CHW, as CHWs have been shown to have greater readiness than clients and higher odds of anticipating themselves capable of performing services than clients reported a need for such services (45, 46).

Most recommended skills and qualities proposed by participants for CHWs working in schools align with those reported in existing literature. Specifically, studies describe it is important for CHWs to be attentive listeners, understand community needs, and function without biases to perform their duties effectively (36, 47). A major strength of CHWs, as described in this study and other research, is their ability to relate personally to clients. Participants recommended that school CHWs be members of the surrounding community to understand the school's needs, similar to research describing that a key asset for CHWs to build trust is sharing life experiences with clients from the same community (47, 48). While not highlighted in this study, recommendations from other research to consider for implementing CHWs in schools is to provide enabling work environments for CHWs with a manageable number of tasks and easy access to supplies (49, 50).

The trainings in core skills and health-related topics recommended in this study, including communication, cultural competency, and mental health, are similar to those described in prior research. Literature supports that evidence-based trainings, including cultural sensitivity, are important for CHWs to work effectively (51). Other specialized trainings from prior studies to consider include program management, advocacy, and evaluation (43).

In terms of evaluating the impact of CHW programming in schools, participants in this study recommended recording CHWs' interactions with the school community, similar to previous research highlighting the importance of tracking the number and quality of interactions between CHWs and clients, team members, and external organizations (52). While not emphasized in this study, other relevant metrics of success described in the literature include cost-efficiency, sustainability, job satisfaction, and CHW involvement in other areas such as school policy (36, 44, 53). Fewer studies have endorsed specific evaluation methods; however, some recommend mixed-methods approaches, aligning with participants who indicated qualitative data can capture nuances while quantitative data can provide summative assessments of effects as well as inform future programs and grant applications (52, 54).

Finally, this study adds to the literature about challenges CHWs may face in their work environment and responsibilities. Participants reported that inadequate resources and overwhelming workloads, which literature also identifies as major barriers for CHWs, may negatively impact work quality (51). Prior studies also observe excessive work demands can lead to stress, social isolation, and burnout, which aligns with the emotional toll that participants described school CHWs may experience (51, 55). Further, participants' comments about CHWs facing pushback from the school community expands upon the limited research about CHWs being potentially unwelcome in the workplace. CHWs working in health care teams have previously shared the importance of dedicating time to building trust with team members during integration (56). As team members may be unaware of how to partner with CHWs, preparing them to work alongside CHWs can help resolve any disruptions related to the integration of CHWs into the team (44, 56).

An important strength of this study is that it elicited rich data from one-on-one interviews with CHWs to thoroughly examine their reflections and ideas. This study highlights the perspectives of CHWs, who have unique insights from their personal work experiences into their role and how it may be applied in school settings. However, this study is not without its limitations. While theme saturation was reached, this study may have limited generalizability due to the sample size and location of participants, with all in the Chicagoland area and most affiliated with a health system. The results may not apply to non-urban or rural communities, although they are foundational to efforts to integrate CHWs in Chicago schools. Furthermore, participants' status as paid employees and demographics (e.g., race, ethnicity, socioeconomic class) are not reported, which may shape their perspectives on integration into schools. Selection bias and recall bias may have also influenced findings. Future studies can examine perspectives from a wider range of CHWs and other relevant stakeholders across communities and regions.

While schools may have an ethical obligation to provide health support to students (57), the schools that would likely derive the most benefit from CHWs may be the least likely to have the capacity or resources to integrate them, which could potentially exacerbate inequalities. Implementing CHWs into under-resourced schools would require obtaining funding, which can be achieved through budgeting administrative dollars toward CHW services, obtaining Department of Education funding, or reimbursing their services through state Medicaid plans if the state acknowledges CHWs as Medicaid providers (58). For schools that lack infrastructure, the implementation of CHWs in schools would require developing unique partnerships with health systems or CHW-focused organizations to facilitate the hiring and integration of school-based CHWs.

CHWs play a valuable role in the health care system, increasing access to care by connecting vulnerable communities to health and social services. While CHWs interventions have positive outcomes in clinical and community settings, the implementation of CHWs in schools has been underexplored. This study engaged experienced CHWs to obtain critical insights on how CHWs can be integrated and utilized in school settings. The results can serve as guidance for schools integrating CHWs and states expanding school-based health services, particularly in the setting of the free care rule reversal by Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (59). This study's findings are especially relevant to clinicians, researchers, and school leaders responsible for ensuring a healthy environment for students within schools.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

This study involved human participants and was reviewed and approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JC, TD, KF, SI, and AV acquired funding for this study. JC, TD, KF, SI, MK, and AV conceptualized and designed this study. MK collected data. NY, MK, LG, and AV analyzed and interpreted data. MK and NY wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program. AV was also supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL143128).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants in this study for their willingness to share their insights and experiences. We would also like to acknowledge Sinai Urban Health Institute for helping facilitate this study and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program for supporting our efforts in promoting health equity.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1187855/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Perrin JM, Bloom SR, Gortmaker SL. The increase of childhood chronic conditions in the United States. JAMA. (2007) 297:2755–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.24.2755

2. Perrin JM, Anderson LE, Van Cleave J. The rise in chronic conditions among infants, children, and youth can be met with continued health system innovations. Health Aff. (2014) 33:2099–105. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0832

3. Gitterman BA, Flanagan PJ, Cotton WH, Dilley KJ, Duffee JH, Green AE, et al. Poverty and Child Health in the United States. Pediatrics. (2016) 137:e20160339. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0339

4. Eide ER, Showalter MH, Goldhaber DD. The relation between children's health and academic achievement. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2010) 32:231–8. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.08.019

5. Margolis R. Childhood morbidity and health in early adulthood: life course linkages in a high morbidity context. Adv Life Course Res. (2010) 15:132–46. doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2010.10.001

6. WHO WHO Expert Committee on Comprehensive School Health Education and Promotion (199) Geneva S Organization WH. Promoting health through schools : report of a WHO Expert Committee on Comprehensive School Health Education and Promotion]. World Health Organization) (1997). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/41987 (accessed May 7, 2023).

7. Walker SC, Kerns SEU, Lyon AR, Bruns EJ, Cosgrove TJ. Impact of school-based health center use on academic outcomes. J Adoles Health. (2010) 46:251–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.07.002

8. Leroy ZC, Wallin R, Lee S. The role of school health services in addressing the needs of students with chronic health conditions: a systematic review. J School Nurs. (2017) 33:64–72. doi: 10.1177/1059840516678909

9. Willgerodt MA, Brock DM, Maughan EM. Public school nursing practice in the United States. J School Nurs. (2018) 34:232–42. doi: 10.1177/1059840517752456

10. Herlitz L, MacIntyre H, Osborn T, Bonell C. The sustainability of public health interventions in schools: a systematic review. Implement Sci. (2020) 15:4. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0961-8

11. Council on School Health. Role of the school nurse in providing school health services. Pediatrics. (2008) 121:1052–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0382

12. Nwabuzor OM. Legislative: shortage of nurses: the school nursing experience. Online J Issues Nurs. (2007) 12:10. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol12No02LegCol01

13. Harries MD, Xu N, Bertenthal MS, Luna V, Akel MJ, Volerman A. Community health workers in schools: a systematic review. Acad Pediatr. (2023) 23:14–23.

14. American Public Health Association. Community Health Workers. Available from: https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers/ (accessed July 31, 2022).

15. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Role of Community Health Workers. (2014). Available online at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/healthdisp/role-of-community-health-workers.htm (accessed July 31, 2022).

16. Bliznashka L, Yousafzai AK, Asheri G, Masanja H, Sudfeld CR. Effects of a community health worker delivered intervention on maternal depressive symptoms in rural Tanzania. Health Policy Plan. (2021) 36:473–83. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa170

17. Hejjaji V, Khetan A, Hughes JW, Gupta P, Jones PG, Ahmed A, et al. A combined community health worker and text messaging based intervention for smoking cessation in India: Project MUKTI—A mixed methods study. Tob Prev Cessat. (2021) 7:23. doi: 10.18332/tpc/132469

18. Grossman-Kahn R, Schoen J, Mallett JW, Brentani A, Kaselitz E, Heisler M. Challenges facing community health workers in Brazil's family health strategy: a qualitative study. Int J Health Plann Manage. (2018) 33:309–20. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2456

19. Musoke D, Atusingwize E, Ndejjo R, Ssemugabo C, Siebert P, Gibson L. Enhancing performance and sustainability of community health worker programs in Uganda: lessons and experiences from stakeholders. Glob Health Sci Pract. (2021) 9:855–68. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-21-00260

20. Hartzler AL, Tuzzio L, Hsu C, Wagner EH. Roles and functions of community health workers in primary care. Annals Family Med. (2018) 16:240–5. doi: 10.1370/afm.2208

21. Campos BM, Kieffer EC, Sinco B, Palmisano G, Spencer MS, Piatt GA. Effectiveness of a community health worker-led diabetes intervention among older and younger latino participants: results from a randomized controlled trial. Geriatrics. (2018) 3:47. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics3030047

22. Hughes MM, Yang E, Ramanathan D, Benjamins MR. Community-based diabetes community health worker intervention in an underserved Chicago population. J Community Health. (2016) 41:1249–56. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0212-8

23. Martin MA, Mosnaim GS, Olson D, Swider S, Karavolos K, Rothschild S. Results from a community-based trial testing a community health worker asthma intervention in Puerto Rican youth in Chicago. J Asthma. (2015) 52:59–70. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.950426

24. Margellos-Anast H, Gutierrez MA, Whitman S. Improving asthma management among African-American children via a community health worker model: findings from a Chicago-based pilot intervention. J Asthma. (2012) 49:380–9. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.660295

25. Campbell JD, Brooks M, Hosokawa P, Robinson J, Song L, Krieger J. Community health worker home visits for medicaid-enrolled children with asthma: effects on asthma outcomes and costs. Am J Public Health. (2015) 105:2366–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302685

26. Pappalardo AA, Martin MA, Weinstein S, Pugach O, Mosnaim GS. Improving adherence in urban youth with asthma: role of community health workers. J Aller Clin Immunol In Pract. (2022) 10:3186–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.08.030

27. Schechter SB, Lakhaney D, Peretz PJ, Matiz LA. Community health worker intervention to address social determinants of health for children hospitalized with asthma. HospPediatrics. (2021) 11:1370–6. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2021-005903

28. Fiori KP, Rehm CD, Sanderson D, Braganza S, Parsons A, Chodon T, et al. Integrating social needs screening and community health workers in primary care: the community linkage to care program. Clin Pediatr. (2020) 59:547–56. doi: 10.1177/0009922820908589

29. Murayama H, Taguchi A, Spencer MS, Yamaguchi T. Efficacy of a community health worker-based intervention in improving dietary habits among community-dwelling older people: a controlled, crossover trial in Japan. Health Educ Behav. (2020) 47:47–56. doi: 10.1177/1090198119891975

30. Park J, Regenstein M, Chong N, Onyilofor CL. The use of community health workers in community health centers. Med Care. (2021) 59:S457. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001607

31. Harries MD, Xu N, Bertenthal MS, Luna V, Akel MJ, Volerman A. Community health workers in schools: a systematic review. Acad Pediatr. (2022) 3:9. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2022.08.015

32. Beatriz E, Aird R, Northrup J. Role of Community Health Workers into Massachusetts School-Based Health Centers. In. American Public Health Association (2019).

34. Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 4th ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. (2014). 456 p.

35. Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine (1967). 271 p.

36. Covert H, Sherman M, Miner K, Lichtveld M. Core competencies and a workforce framework for community health workers: a model for advancing the profession. Am J Public Health. (2019) 109:320–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304737

37. Glenton C, Javadi D, Perry HB. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 5. Roles Tasks Health Res Pol Sys. (2021) 19:128. doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00748-4

38. Schroeder K, McCormick R, Perez A, Lipman TH. The role and impact of community health workers in childhood obesity interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. (2018) 19:1371–84. doi: 10.1111/obr.12714

39. Pérez LM, Martinez J. Community health workers: social justice and policy advocates for community health and wellbeing. Am J Public Health. (2008) 98:11–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100842

40. Patino-Fernandez AM, Hernandez J, Villa M, Delamater A. School-based health promotion intervention: parent and school staff perspectives. J Sch Health. (2013) 83:763–70. doi: 10.1111/josh.12092

41. Moon J, Williford A, Mendenhall A. Educators' perceptions of youth mental health: Implications for training and the promotion of mental health services in schools. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2017) 73:384–91. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.01.006

42. Boldt A, Nguyen M, King S, Breitenstein SM. Community health workers: connecting communities and supporting school nurses. NASN School Nurse. (2021) 36:99–103. doi: 10.1177/1942602X20976545

43. Sherman M, Covert H, Fox L, Lichtveld M. Successes and lessons learned from implementing community health worker programs in community-based and clinical settings: insights from the gulf coast. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2017) 23:S85. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000653

44. Findley S, Matos S, Hicks A, Chang J, Reich D. Community health worker integration into the health care team accomplishes the triple aim in a patient-centered medical home: a bronx tale. J Ambul Care Manage. (2014) 37:82–91. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000011

45. Lewis CM, Gamboa-Maldonado T, Belliard JC, Nelson A, Montgomery S. Preparing for community health worker integration into clinical care teams through an understanding of patient and community health worker readiness and intent. J Ambul Care Manage. (2019) 42:37–46. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000261

46. Lewis CM, Gamboa-Maldonado T, Belliard JC, Nelson A, Montgomery S. Patient and community health worker perceptions of community health worker clinical integration. J Community Health. (2019) 44:159–68. doi: 10.1007/s10900-018-0566-1

47. Surjaningrum ER, Jorm AF, Minas H, Kakuma R. Personal attributes and competencies required by community health workers for a role in integrated mental health care for perinatal depression: voices of primary health care stakeholders from Surabaya, Indonesia. Int J Ment Health Syst. (2018) 12:46. doi: 10.1186/s13033-018-0224-0

48. Balcazar H, Rosenthal EL, Brownstein JN, Rush CH, Matos S, Hernandez L. Community health workers can be a public health force for change in the United States: three actions for a new paradigm. Am J Public Health. (2011) 101:2199–203. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300386

49. Jaskiewicz W, Tulenko K. Increasing community health worker productivity and effectiveness: a review of the influence of the work environment. Hum Resour Health. (2012) 10:38. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-10-38

50. Brown O, Kangovi S, Wiggins N, Alvarado CS. Supervision strategies and community health worker effectiveness in health care settings. NAM Perspect. (2020) 5:10.31478/202003c. doi: 10.31478/202003c

51. Garcini LM, Kanzler KE, Daly R, Abraham C, Hernandez L, Romero R, et al. Mind the gap: Identifying training needs of community health workers to address mental health in US Latino communities during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:928575. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.928575

52. Sherman M, Covert HH, Lichtveld MY. “The more we know, the more we're able to help”: participatory development of an evaluation framework for community health worker programs. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2022) 28:E734. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001528

53. Wiggins N, Maes K, Palmisano G, Avila LR, Rodela K, Kieffer E, et al. Community participatory approach to identify common evaluation indicators for community health worker practice. Prog Commun Health Partnerships: Res Edu Action. (2021) 15:217–24. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2021.0023

54. Kok M, Crigler L, Musoke D, Ballard M, Hodgins S, Perry HB. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 10. Programme Perfor Assess Health Res Policy Sys. (2021) 19:108. doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00758-2

55. Johnson LJ, Schopp LH, Waggie F, Frantz JM. Challenges experienced by community health workers and their motivation to attend a self-management programme. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. (2022) 14:2911. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v14i1.2911

56. Allen CG, Escoffery C, Satsangi A, Brownstein JN. Strategies to improve the integration of community health workers into health care teams: “A Little Fish in a Big Pond”. Prev Chronic Dis. (2015) 12:E154. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.150199

57. Crawford PB, Gosliner W, Kayman H. Peer reviewed: The ethical basis for promoting nutritional health in public schools in the United States. Prevent Chron Dis. (2011) 8:A95. Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2011/sep/10_0283.htm (accessed February 22, 2023).

58. Haldar S, Hinton E. State Policies for Expanding Medicaid Coverage of Community Health Worker (CHW) Services. KFF. (2023). Available online at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/state-policies-for-expanding-medicaid-coverage-of-community-health-worker-chw-services/ (accessed May 10, 2023).

59. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid Payment for Services Provided without Charge (Free Care). (2014). Available online at: https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd-medicaid-payment-for-services-provided-without-charge-free-care.pdf (accessed May 10, 2023).

Keywords: child, community health workers, healthy environments, qualitative analysis, school setting, student health

Citation: Yao N, Kowalczyk M, Gregory L, Cheatham J, DeClemente T, Fox K, Ignoffo S and Volerman A (2023) Community health workers' perspectives on integrating into school settings to support student health. Front. Public Health 11:1187855. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1187855

Received: 16 March 2023; Accepted: 23 May 2023;

Published: 21 June 2023.

Edited by:

Graça S. Carvalho, University of Minho, PortugalReviewed by:

Ivan Santolalla Arnedo, University of La Rioja, SpainFlorian Steger, University of Ulm, Germany

Copyright © 2023 Yao, Kowalczyk, Gregory, Cheatham, DeClemente, Fox, Ignoffo and Volerman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anna Volerman, YXZvbGVybWFuQHVjaGljYWdvLmVkdQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Nicole Yao

Nicole Yao Monica Kowalczyk

Monica Kowalczyk LaToya Gregory1

LaToya Gregory1 Jeannine Cheatham

Jeannine Cheatham Stacy Ignoffo

Stacy Ignoffo Anna Volerman

Anna Volerman