95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Public Health , 18 May 2023

Sec. Public Health Policy

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1182328

This article is part of the Research Topic Community Series in Mental Illness, Culture, and Society: Dealing with the COVID-19 Pandemic, Volume VI View all 10 articles

Ellen Kuhlmann1,2*†‡

Ellen Kuhlmann1,2*†‡ Michelle Falkenbach3†‡

Michelle Falkenbach3†‡ Gabriela Lotta4

Gabriela Lotta4 Tim Tenbensel5‡

Tim Tenbensel5‡ Alexandra Dopfer-Jablonka1,6‡

Alexandra Dopfer-Jablonka1,6‡Introduction: Violence against healthcare workers is a global health problem threatening healthcare workforce retention and health system resilience in a fragile post-COVID ‘normalisation’ period. In this perspective article, we argue that violence against healthcare workers must be made a greater priority. Our novel contribution to the debate is a comparative health system and policy approach.

Methods: We have chosen a most different systems comparative approach concerning the epidemiological, political, and geographic contexts. Brazil (under the Bolsonaro government) and the United Kingdom (under the Johnson government) serve as examples of countries that were strongly hit by the pandemic in epidemiological terms while also displaying policy failures. New Zealand and Germany represent the opposite. A rapid assessment was undertaken based on secondary sources and country expertise.

Results: We found similar problems across countries. A global crisis makes healthcare workers vulnerable to violence. Furthermore, insufficient data and monitoring hamper effective prevention, and lack of attention may threaten women, the nursing profession, and migrant/minority groups the most. There were also relevant differences. No clear health system pattern can be identified. At the same time, professional associations and partly the media are strong policy actors against violence.

Conclusion: In all countries, muchmore involvement from political leadership is needed. In addition, attention to the political dimension and all forms of violence are essential.

Violence against healthcare workers (HCWs) is a persistent and pressing concern, and the COVID-19 pandemic has added new threats. Systematic data and monitoring are still lacking, yet international organisations and mounting individual cases call to action, highlighting sharp increases and qualitatively new dimensions of hate, harassment, and severe violent attacks against HCWs (1–4). An increase in violence amidst a major global health crisis is exceptionally problematic, considering the dire need for HCWs who are subjected to immense pressures and run high risks of illness (5, 6). These attacks threaten individual HCWs and may even result in traumatisation and temporary absence due to illness. They also create long-term risks for the healthcare workforce (HCWF) and strain recruitment and retention efforts. Since women account for about 75% of HCWs in most countries, the gender-based and sexual violence dimensions, as well as the threats to nurses, are evident (1, 3, 6).

Increased violence against the HCWs comes at a critical point in the global health crisis when countries worldwide struggle to meet population health demands due to severe HCWF shortages (7–10). Given the resolute nature of the concern, its impact on health and care systems, and its detrimental effect on HCWs and gender equality, it is time that violence against HCWs is given much greater priority as a policy problem.

This perspective article brings policy and politics into the debate on violence against HCWs. Available evidence shows that violence was heightened during the pandemic, even in countries with formal democratic institutions and upper-middle to high-resourced healthcare systems. This raises questions as to whether and how institutional/systemic, epidemiological, and pandemic policy conditions shape the debate on violence. Applying a comparative lens and exploring the problem within various countries may help identify policy gaps and develop new policy solutions.

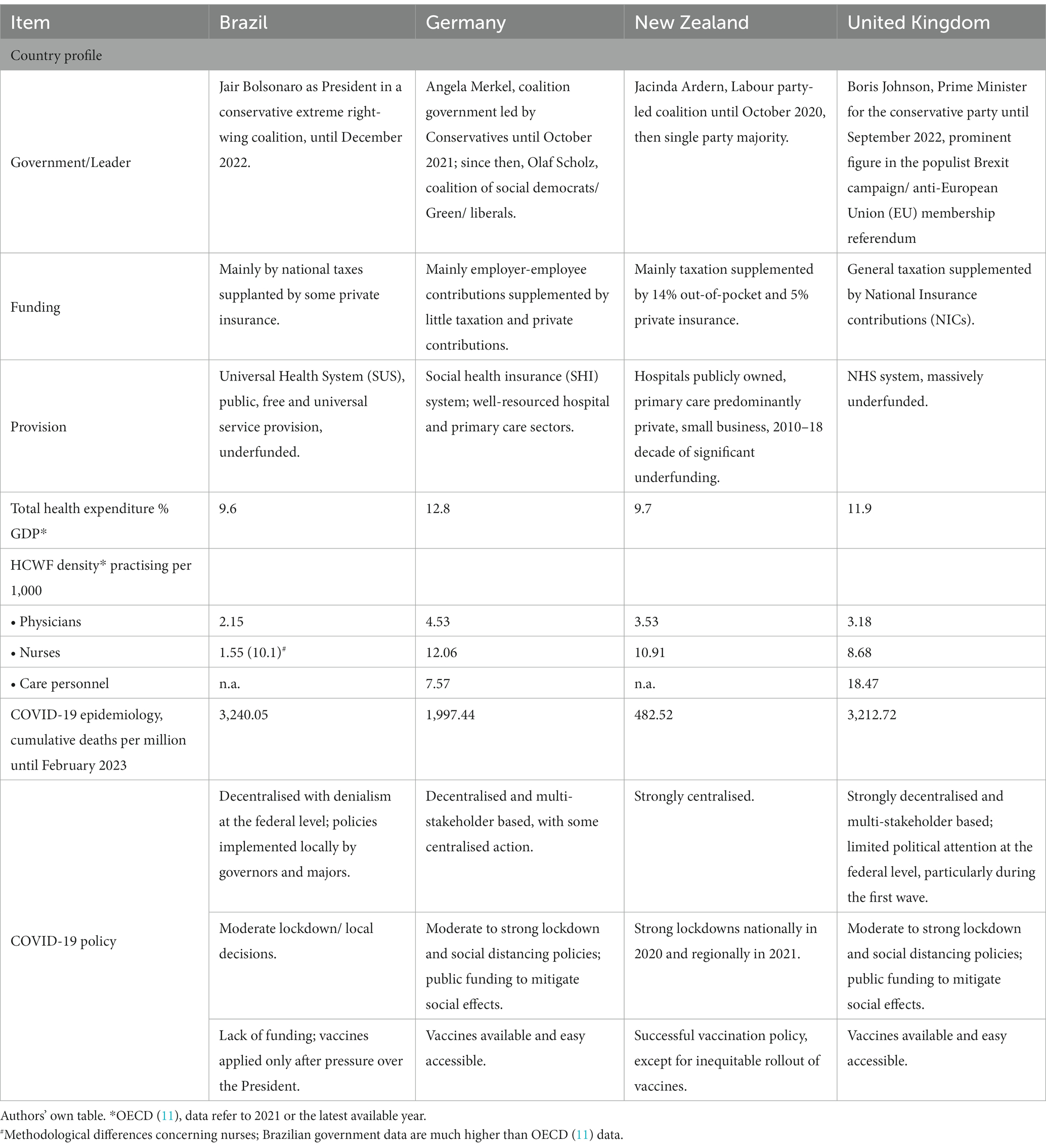

We have chosen a most different systems comparative approach concerning the epidemiological, political, and geographic contexts. In our research design (Table 1), Brazil (under the Bolsonaro government) and the United Kingdom (under the Johnson government) serve as examples of countries that were strongly hit by the pandemic in epidemiological terms while also displaying policy failures attributed to populist right-wing governments (12, 13). New Zealand and Germany represent the opposite. They serve as representatives of countries that managed the pandemic comparatively well under more moderate and balanced political constellations (14, 15). We refer to the period of the COVID-19 pandemic from its onset in 2020 until the end of 2022.

Table 1. Mapping the country sample: health system, workforce, and COVID-19 pandemic characteristics.

We rapidly assessed available data, policy responses and actors, and material on the discourse surrounding violence and actions taken against it in the four selected countries. A topic guide served as a framework for the comparative assessment, drawing on country expertise and secondary sources (media reports, documents, public data, and surveys).

Our comparative assessment (Table 2) highlights two significant elements: the global dimension of violence against HCWs, and specific policy gaps that may hamper action taken to prevent violence. The results concerning the global dimension broadly reveal similar challenges in a country sample characterised by institutional and epidemiological differences in higher-middle and high-income countries (Table 1). This is an important finding because it suggests that violence occurs no matter how rich, developed or epidemiologically advanced a country may be. Therefore, increased funding and staffing are essential but insufficient to resolve the problem without additional measures. At the same time, we found some important differences related to policy and actors. Against this backdrop, a better understanding of policy gaps may pave the way for new opportunities for action both globally and in the national context.

Available data is scattered, and access is generally limited in all countries. Evidence is mainly based on either criminal (police) statistics or surveys, both of which are limited in their ability to tell a holistic story. While pre-COVID survey data exists in New Zealand and the UK, suggesting that violence was a relevant health system problem before the pandemic, a lack of systematic data and monitoring systems makes it difficult to explore to what extent and why violence actually increased during the pandemic. Insufficient empirical evidence hampers a critical debate and the development of effective policy solutions and also opens the door for various forms of interest-driven politics.

Strong political leadership and effective policies play a critical role in aiding HCWs. Unfortunately, political leadership in the examined countries has remained sparse; however, health professional associations (doctors, nurses, and paramedics) have proven to be important and valuable supporters. The nurses’ associations appear to play the biggest supportive role in Brazil, while doctors’ associations take the lead in Germany. The associations in New Zealand and the UK also matter, including hospital organisations and paramedics associations.

The policy initiatives among the cases reflect country-specific governance arrangements, particularly centralised vs. decentralised governance structures. The most centralised efforts can be seen in the UK, where the NHS is working to improve data collection and analysis across NHS trusts, propelled by the #WorkWithoutFear campaign. The associations and some regional (Länder) governments called for a centralised register system to monitor attacks in Germany. In addition, legal action was taken to improve policy statistics; here, we can observe more decisive action taken on the organisational and operational levels of governance (e.g., increasing security services and technical support). The other two countries showed limited initiative. Overall, sensitivity to the problem seems to be increasing, yet change is incremental, action is limited to piecemeal work, and actor collaboration is poorly developed (reflecting professional silos). Much more involvement from political leadership is necessary to set the agenda throughout government and society, thereby increasing the likelihood of action and, hopefully, changing the status quo on violence against the HCW.

If violence is addressed, this mainly relates to doctors and nurses as the most significant groups, with some country-specific variation. However, health workforce policy primarily focuses on health labour markets and system needs rather than on HCWs as human beings with specific conditions and needs related to age, sex, gender, ethnicity/race, and other social positions. Ignoring the human behind every HCW seriously obstructs the opportunity to protect HCWs better and improve prevention. This creates additional policy gaps exacerbating existing social inequalities in the HCWF, especially in professional groups with more women and migrant HCWs.

The connection to the COVID-19 pandemic was substantial, especially in Germany and Brazil, where increased violence against HCWs was most prominent. New Zealand and especially the United Kingdom have faced the challenge of violence well before the pandemic; however, only the latter country has developed the beginnings of a strategy to combat it. We generally observed an overall lack of attention to the political dimension of violence against HCWs. However, there were also some examples of explicit connections to the populist radical right movement in Brazil.

Violence against HCWs is and will remain a problem long after the pandemic subsides. If political action is not taken, HCWs will have an additional reason to leave their profession and workplace, and potential candidates will be made to consider the increasing risks of HCWs and pursue a different line of work. In a time when countries across the globe are struggling with HCW retention and recruitment protecting the health and care workforce is essential. Getting support and protection right enhances the retention of the existing workforce and will attract new generations of HCWs. Improved working conditions, mental health, and physical safety of HCWs are an obligation not only of organisations and employers but also of governments and policymakers. This will require governments to prioritise developing feasible and effective policy responses that tackle the many individual risk factors the HCWs face on a daily basis, as well as the health workforce and system-related risks.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

EK and MF had the idea, developed the framework, supervised the analysis, and prepared a draft. EK, MF, GL, TT, and AD-J collected the country cases, contributed to the analysis, commented on the draft, and have read and approved the final version. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

We wish to thank Gemma Williams for the very helpful information and comments.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1182328/full#supplementary-material

1. International Council of Nurses (ICN). International Committee Red Cross (ICRC), International Hospital Federation (IHF), World Medical Federation (WMF). Violence against health care: current practices to prevent, reduce or mitigate violence against health care. Geneva: ICN, ICRC, IHF and WMF. (2022). Available at: (https://www.icn.ch/system/files/2022-07/Violence%20against%20healthcare%20survey%20report.pdf).

2. International Labour Organisation (ILO). Joint programme launches new initiative against workplace violence in the health sector. Geneva: ILO. (2022). Available at: https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_007817/lang--en/index.htm (accessed February 28, 2023).

3. Women in Global Health (WGH). Policy Report #HealthToo. New York: WGH. (2022). Available at: https://womeningh.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/WGH-Her-Stories-SEAH-Report_Policy-Report-Dec-2022.pdf (accessed February 28, 2023).

4. World Health Organisation (WHO). Preventing violence against health workers. Geneva: WHO (2022). Available at: https://www.who.int/activities/preventing-violence-against-health-workers (accessed February 28, 2023).

5. Brigo, F, Zaboli, A, Rella, E, Sibilio, S, Canelles, MF, Magnarelli, G, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on temporal trends of workplace violence against healthcare workers in the emergency department. Health Policy. (2022) 126:1110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.09.010

6. Kuhlmann, E, Brînzac, MG, Czabanowska, K, Falkenbach, M, Ungureanu, MI, Valiotis, G, et al. Violence against healthcare workers is a political problem and a public health issue: a call to action. Eur J Pub Health. (2023) 33:4–5. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckac180

7. McKay, D, Heilser, M, Mishori, R, Catton, H, and Kloiber, O. Attacks against health-care personnel must stop, especially as the world fights COVID-19. Lancet. (2020) 395:1743–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31191-0

8. Thornton, J. Violence against healthcare workers rises during COVID-19. Lancet. (2022) 400:348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01420-9

9. World Health Organisation European Region (WHO Euro). Health and care workforce in Europe. Time to act Copenhagen: WHO Euro. (2022). Available at: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289058339 (accessed February 28, 2023).

10. Ziemann, M, Chen, C, Forman, R, Sagan, A, and Pittman, P. Global health workforce responses to address the COVID-19 pandemic: what policies and practices to recruit, retain, reskill, and support health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic should inform future workforce development?. Brussels: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2023). Available at: https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/global-health-workforce-responses-to-address-the-covid-19-pandemic-what-policies-and-practices-to-recruit-retain-reskill-and-support-health-workers-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-should-inform-future-workforce-development (Accessed 21 April 2023).

12. Massard da Fonseca, E, Nattrass, N, Bolaffi Arantes, L, and Bastos, FI. COVID-19 in Brazil In: SL Greer, EJ King, E Massard da Fonseca, and A Peralta-Santos, editors. Coronavirus Politics. The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19. Michigan: University of Michigan Press (2021).

13. Williams, GA, Rajan, S, and Cylus, JD. COVID-19 in the United Kingdom: how austerity and a loss of state capacity undermined the crisis response In: SL Greer, EJ King, E Massard da Fonseca, and A Peralta-Santos, editors. Coronavirus Politics. The Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19. Michigan: University of Michigan Press (2021).

14. Bromfield, N, and McConnell, A. Two routes to precarious success: Australia, New Zealand, COVID-19 and the politics of crisis governance. Int Rev Adm Sci. (2021) 87:518–35. doi: 10.1177/0020852320972465

Keywords: healthcare workforce, violence against healthcare workers, health policy, global health crisis, public health, COVID-19 pandemic, international comparison

Citation: Kuhlmann E, Falkenbach M, Lotta G, Tenbensel T and Dopfer-Jablonka A (2023) Violence against healthcare workers in the middle of a global health crisis: what is it about policy and what to learn from international comparison? Front. Public Health. 11:1182328. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1182328

Received: 08 March 2023; Accepted: 13 April 2023;

Published: 18 May 2023.

Edited by:

Ravi Philip Rajkumar, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), IndiaReviewed by:

Arielle Kaim, Tel Aviv University, IsraelCopyright © 2023 Kuhlmann, Falkenbach, Lotta, Tenbensel and Dopfer-Jablonka. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ellen Kuhlmann, a3VobG1hbm4uZWxsZW5AbWgtaGFubm92ZXIuZGU=

†These authors share first authorship

‡ORCID: Ellen Kuhlmann, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7337-114X

Michelle Falkenbach, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5073-5193

Gabriela Lotta, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2801-1628

Tim Tenbensel, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7832-3318

Alexandra Dopfer-Jablonka, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7129-100X

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.