- 1Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 2National Association of County and City Health Officials, Washington, DC, United States

- 3Department of Clinical Research and Leadership, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, United States

- 4San Mateo County Health, San Mateo, CA, United States

- 5Alala Advisors, LLC., Irvine, CA, United States

Objectives: The aim of this study was to collect qualitative data regarding the violence faced by public health officials during the COVID-19 pandemic and create a guideline of recommendations to protect this population moving forward.

Methods: Two focus groups were conducted virtually from April 2022 to May 2022. All nine participants were public health officials from across California. A grounded theory approach was used to analyze the data from these focus groups.

Results: The main recurrent experiences among public health officials were harassment, psychological impact, systemic backlash, and burnout. Several recommendations for supporting public health officials were highlighted, including security and protection, mental health support, public awareness, and political/institutional support.

Conclusion: Our study captures the violent experiences that health officials have faced during the COVID-19 pandemic. To maintain the integrity of the public health system, timely changes must be made to support and protect health officials. Our guideline of recommendations provides a multi-faceted approach to the urgent threats that officials continue to face. By implementing these solutions, we can strengthen our public health system and improve our response to future national emergencies.

Introduction

Throughout the past 3 years, the COVID-19 pandemic has sparked several unforeseen circumstances, such as violence, stigma, and the politicization of the public health system in the United States (1, 2). The backbone of this system is comprised of public health personnel who have worked tirelessly to prevent the spread of COVID-19 (3). Prior to the pandemic, the public health system was weakened by systematic flaws and chronic underfunding (4). Between 2003 and 2021, funding for Public Health Emergency Preparedness dropped by approximately 50% after adjusting for inflation (5). Along with being fiscally unsupported, the pandemic has exposed several weaknesses across all facets of the healthcare and public health system (6). Between 2020 and 2021, USA Facts reported a total of 101,918 COVID-19-related deaths in California and an estimated 11,263,545 reported cases. These staggering numbers further strained healthcare workers, including public health officials. Furthermore, healthcare personnel have faced tremendous violence due to the political frustration of citizens nationally, who feel that their personal liberties have been encroached (3, 6–8). Dye et al. found that, even after controlling for various confounders, healthcare workers are significantly more likely to experience COVID-19-related bullying or stigma compared to others (1).

Public health officials comprise a particularly vulnerable subset of this population and have faced extreme violence during the COVID-19 pandemic (6, 7, 9). Two survey waves reported that American adults who believed that harassment of health officials due to business closures was justified rose from 20% to 25% in November 2020 and from 15% to 21% from July 2021 to August 2021 (10). Harassment includes death threats, vandalism, hate speech, and physical endangerment (9). In 2020, an estimated 9%−12% of public health officials reported receiving either individual or family threats (11).

There have been numerous breaches of officials' personal information as their residential addresses, phone numbers, and emails were doxed through the Internet (12, 13). Many officials fear the loss of their jobs or putting themselves at further risk, leaving them silent and isolated (7, 9, 14). This also pressures officials to comply with public or political opinions rather than focusing on what is best for community health (7). Officials who are harassed are vulnerable to stress intolerance, a lack of meaning in work, and greater turnover rates (15, 16). These conditions also contribute to mental illness among officials during and following the pandemic's heights (16).

Bryant et al. reported that 53% of public health workers had reported feeling at least one symptom of mental illness in the previous 2 weeks (14). Anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were among the most prevalent conditions (14). Despite suffering from these illnesses, officials continued working 12–14 h per day with a minimal number of employees and negligible support (17).

Attrition rates among public health officials have increased since the first spike of retirements in May 2020 (18). Ward et al. reported that from March 2020 to January 2021, a total of 120 resignations, 58 retirements, 20 firings, and 24 other departures occurred among health officials in the United States (18). Some public health experts claim that this is the greatest exodus of public health workers throughout American history, with 1 in 6 Americans losing a local public health official during the pandemic (19).

The public health system will further suffer, along with its officials, if timely changes are not made to prevent violence moving forward (13, 20). Topazian et al. highlighted strategies to support health officials, such as additional funding, more protection, and an improved system against violence (10, 16). Furthermore, Ward et al. reported that, in order to understand violence among public health officials, affected individuals must have a platform to share their personal experiences (18).

The 2020 Forces of Change Survey Report by the National Association of County and City Health Officials, along with other literature, captures quantitative data showing the violence toward public health officials during the pandemic (11). However, there is a lack of qualitative research on this topic. The goal of our study was to fill this research gap and provide public health officials with the opportunity to openly discuss their experiences during the pandemic. In August 2022, the American Journal of Public Health produced a podcast that shed light on the experiences of public health officials during the pandemic (12). Our study expands on several of the issues that were discussed, such as the negative and abrupt spotlight on public health, the isolation of officials, and the politicization of the pandemic. Furthermore, through collaboration with public health personnel, we will create a robust guideline of changes and recommendations to better support and protect this targeted population in the future. We hope that these proposed solutions will also shape political and institutional actions moving forward.

Methods

This qualitative study was a collaborative effort between the University of Southern California, a local health officers' organization, and the National Association of City and County Health Officials. Institutional Review Board approval was received to collect quantitative and qualitative data from public health officials from across California. A total of two focus groups were held, with a total of nine participants overall. These were conducted between April 2022 and May 2022.

Population

A total of nine English-speaking public health officials took part in this study. Participants were recruited through an organization of health officers in California via electronic approaches such as email. No participants dropped out of the study.

Measures

Before the focus groups, participants answered a short demographic survey that assessed officials' duration of public health experience and their contemplations on holding their positions during the pandemic. Focus groups were then led by a senior researcher (R.V.B.), who facilitated the discussion with the officials. A research assistant (A.S.D.) was also present in the focus groups to take notes. The researchers had no prior connections with the participants before the focus groups were conducted. Participants were informed that the goal of the project was to understand the experiences of public health officials during the pandemic and to propose solutions to any negative experiences. An outline of the interviewers' script for each focus group is provided in the Appendix and includes the introduction, questions, and closing statement.

Two focus groups lasting ~1 h and a half each were conducted, with three to six participants in each. Each participant was present for only one of these groups. Focus groups were kept small to ensure that participants could speak freely in private settings. Additional focus groups were not conducted since this was a pilot study, and more subjects are anticipated to be added in the future. Our sample size was limited because the officials were overwhelmed and stressed and often struggling with mental illnesses such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Both focus groups were conducted via Zoom using audio and video recording, with informed consent from all participants.

Statistical analysis

A grounded theory approach, established by Glaser et al. (21), was used to analyze the qualitative data. This strategy was utilized because it is a flexible approach that can cope with highly exploratory scenarios where little is known. To analyze the data, the discussion from each focus group was transcribed, and participants were deidentified. These transcripts were kept confidential and viewed only by the primary coder (A.S.D.) and the principal investigator (R.V.B.). The data from the demographic surveys were organized using Microsoft Excel. The primary coder (A.S.D.) established codes to summarize the data on ATLAS.ti (Version 9.1.3; ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). A conventional content analysis approach was used to organize the rich qualitative data from the focus groups. To ensure that the coding was both valid and reliable, the criteria for assigning a specific code to a block of text were systematically developed and well documented using the ATLAS.ti software. The coding scheme was refined and expanded upon to reflect and include emerging insights throughout the coding process. Twenty percent of the coder's cases were double-coded by another coder to ensure continued inter-coder reliability and validity. Disparities in coding were discussed and resolved. These codes lead to the development of larger concepts. There was a simultaneous and iterative process of data collection, analysis, and theory construction that resulted in adaptive changes in the focus groups as the study progressed. In Tables 2, 3, various quotes were mentioned in bold to highlight their importance and significance within each concept.

Results

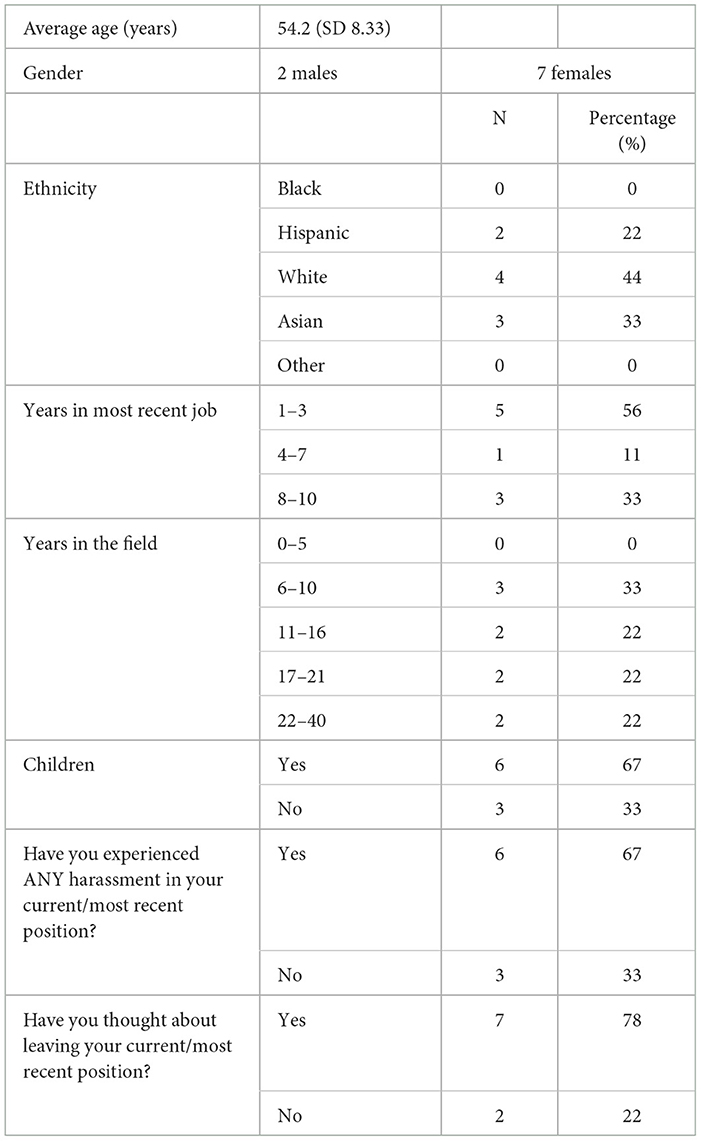

The participants' demographic information is summarized in Table 1. All the participants had 5 or more years of experience working in the public health field, with a majority (66%) having 10+ years of experience. Over half (56%) of the participants had been in their most recent job for 1–3 years, while the remainder had worked at their jobs for more than 4 years. Seven (78%) participants had considered leaving their most recent position. Six (67%) participants reported experiencing some form of harassment in their most recent position, compared to three (33%) participants who did not.

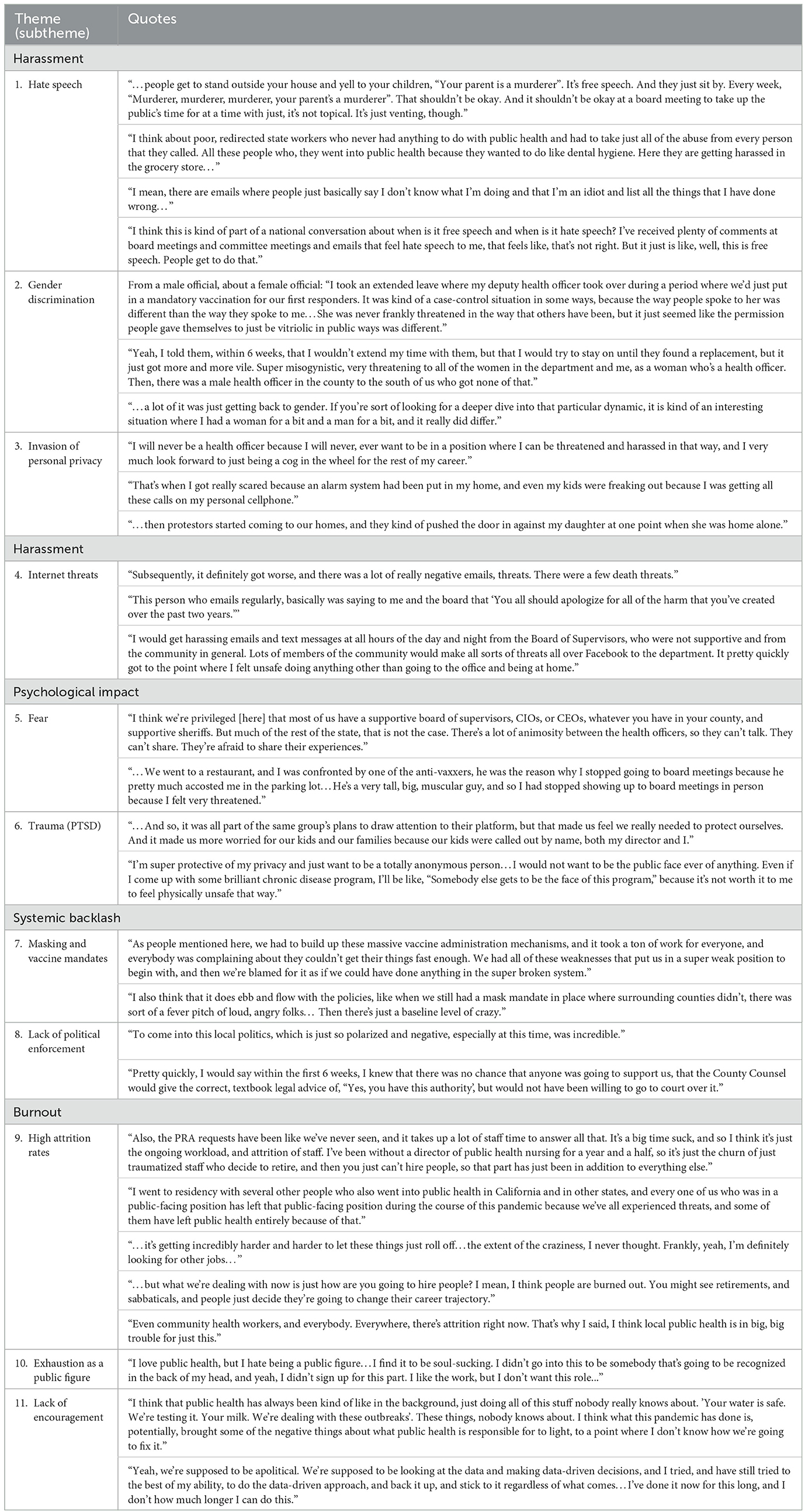

The qualitative data displayed several repetitive themes among the experiences of public health officials. These themes included (1) harassment, (2) psychological impact, (3) systemic backlash, and (4) burnout.

Experiences among public health officials

Harassment

Within the past 3 years, the general public has associated health officials with the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. In response, there were several acts of violence toward officials. Furthermore, angry protestors have knocked down officials' doors, invaded their personal privacy, and committed other forms of threatening harassment. Evidence shows that female public health officials have been treated with disproportionally more violence than their male counterparts. Although officials' assistants are trained to screen text messages and emails for threatening messages, officials often still receive these threats (Table 2, Theme 4).

Psychological impact

Public health officials suffered from many mental illnesses such as PTSD, anxiety, and depression. Harassment from citizens instilled fear in officials for their personal safety and their families' safety. Respondents reported that this fear kept them isolated from their communities and neighborhoods. Many officials reported losing friends during the pandemic due to their grueling work schedules and the isolation of holding public health positions. Lastly, some officials reported that they could not sit still as their anxiety was too overpowering. They stated that these conditions were not sustainable and contributed to high levels of burnout.

Systemic backlash

The systemic backlash from Administrative Board Members and government institutions made it difficult for officials to do their jobs properly. Particularly, there was often backlash due to masking and vaccine mandates, and public health officials were faced with the brunt of this hostility. Officials were often unsupported by political leaders and law enforcement, which restricted their autonomy and power (Table 2, Themes 6 and 7).

Burnout

Attrition rates have heightened as many experienced individuals were exhausted and overworked. Officials stepped down from public-facing positions that were constantly targeted by the public. Many who had not yet quit were searching for other job opportunities since the beginning of the pandemic. After 10+ years working in public health, many officials were pessimistic about the future of this field.

Recommendations and solutions

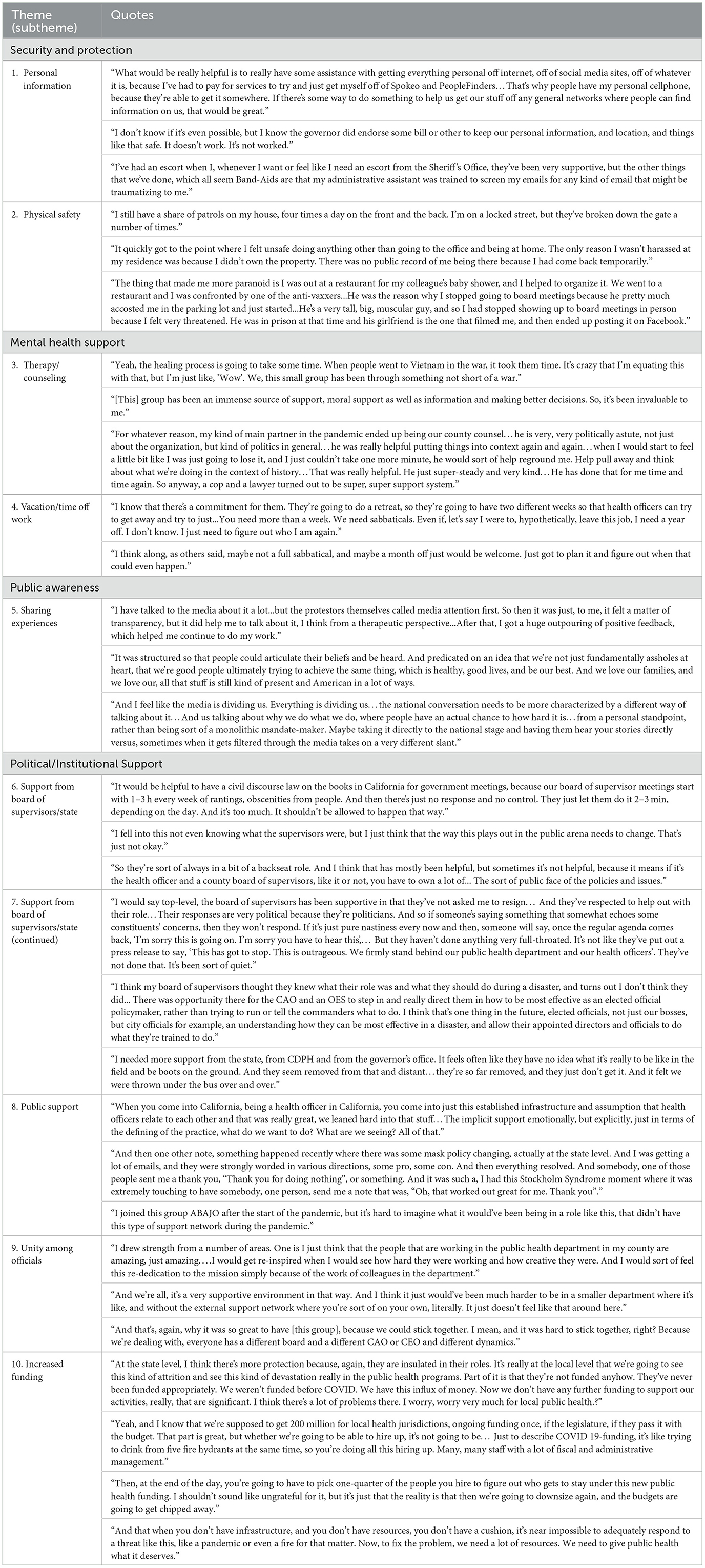

Throughout the focus groups, officials spoke about several recommendations that could better support and protect them in the future.

Security and protection

Officials believed that improved security would make them feel safer and improve mental illness. First, law enforcement authorities must make a greater effort to protect officials from the doxing of their personal information. This can be accomplished by sweeping the Internet of personal emails, phone numbers, and addresses to mitigate threats that officials receive. Health departments should be equipped with resources to implement security protections or hire personnel who have the skills to do so. Lastly, protection of personal residential addresses would prevent angry protestors from storming officials' houses and properties. Quote 3 in Theme 2 shows how aggression and hostility can also transcend the workplace, illustrating the need for protection in other environments as well (Table 3).

Finally, officials' physical safety must be safeguarded during the completion of their jobs. Many officials were urged to go into their offices unprotected, despite angry riots and protests. A remote option should be available to ensure that officials are not in physical danger.

Mental health support

The pandemic sparked several mental health illnesses among public health officials, and there must be support provided for officials to heal as they continue to work. This includes resources allocated toward therapy, counseling, and sabbaticals for officials. Without these interventions, officials' PTSD, depression, and anxiety will only continue to develop and worsen. Participants stated that although this is not a long-term solution to the abuse that they have faced, it would be an opportunity for them to heal after months of stress.

Public awareness

Providing public health officials with a space to share their experiences is vital to humanizing this population for the public. It has been a challenge for officials to speak openly about the tough circumstances under which they have worked. Having a non-filtered line of communication between officials and the public would be beneficial for both parties as it could help build an understanding of their frustrations. Officials also shared their positive experiences talking with citizens respectfully and how this has helped to amend their differences in opinions. The media can assist with this process by combating the spread of misinformation.

Political/institutional support

Participants reported that the most comprehensive change that could be made was to encourage support throughout several institutions that interface with, support, fund, or regulate local public health departments. In our focus groups, officials frequently discussed the lack of support from their Board of Supervisors. Conflicts between officials and other groups often trickle down to their counties, causing further frustration among citizens.

Furthermore, the officials shared that they were frustrated by politicians who try to appeal to the public rather than to show support. To combat this, the officials stated that leaders must be better educated on public health topics to understand the reasoning behind public health decisions. Law enforcement must also follow in these efforts by ensuring that people respect and follow mandates.

Discussion

The results from our study are consistent with other literature that illustrates the intense, negative circumstances that public health officials have endured during the pandemic (17, 22, 23). Four major themes were identified to summarize public health officials' experiences during the pandemic, including harassment, psychological impact, systemic backlash, and burnout. Other literature identified similar themes such as under-recognized expertise, disorganized infrastructure, and politicized public health (24). An estimated 59% of officials felt that their expertise was undermined during the pandemic (8, 25), contributing to the isolation that many officials felt in their most recent positions (17, 19, 23).

Officials stated that harassment during the pandemic has been the driving factor of their desire to resign. Since the beginning of the pandemic, an increasing number of American adults believe that harassing public health officials is justified (10, 12). Two-thirds of participants in our study reported feeling harassed in their current or most recent position. In a national survey by the National Association of County and City Health Officials and analyzed by Ward et al., there were 1,499 reports of harassment across 57% of departments, with 43% of officials reporting that they had been individually targeted (11, 18). Another study reports that 41% of public health executives felt bullied, harassed, or threatened by people outside of the health department.

Other studies show that the impact of workplace aggression leads to lower self-efficacy, higher turnover rates, and less job satisfaction (14). Poor mental health has been a leading cause of burnout and depression among public health officials, leading to higher attrition rates (16). In fact, a survey from March 2021 showed that 36.8% of public health workers reported feeling at least one symptom of PTSD in the previous 2 weeks (14). However, 19.6% of public health workers reported needing mental health counseling in the previous month but not receiving it (14).

The CDC reported a similar trend to our results, with the percentage of public health officials who had reported considering leaving their jobs increasing from 44% to 76% before and after the pandemic began, respectively (6). One-third of the public health workforce is estimated to have the intention of resigning in the next year (25, 26). Several participants in our focus groups reported that they had been searching for new positions since the pandemic began and were considering leaving the public health field altogether. These high attrition rates weaken the public health system, especially as new, less experienced individuals fill these roles (19, 23).

Some say that politics is the “public health poison,” as it interrupts how the system works effectively (23). The National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) found that political pressure had caused 32 agency leaders from 25 departments to resign, change positions, or be fired (18). Officials in our focus groups shared that this pressure had become unbearable, especially when establishing masking or vaccine protocols. Participants shared that their county's political values significantly impacted the extremity of violence that they endured. Funk et al. showed that most Democrats believed that efforts to protect public health have been too scarce (46%), while most Republicans (40%) felt that there was too much priority given to supporting public health (2). Extreme public disapproval has led to national movements to limit health departments' power to make decisions that protect community health (27). As of May 2021, 15 legislatures were considering or had already passed laws to limit the legal jurisdiction of public health agencies (27).

An analysis of our qualitative data showed three main themes for solutions that were discussed: (a) security and protection, (b) mental health support, and (c) political or institutional support. The ongoing stress from fear of personal endangerment is an urgent problem contributing to high rates of burnout in the field (20, 28). To address this, more protective measures must be taken to protect officials and their families.

Many participants felt that there were no punitive actions after they had been harassed or threatened. An estimated 20% of COVID-19 scientists and professionals who reported receiving death threats had employers who were unresponsive or unsupportive (29). To prevent this, there must be strict punishments for those who threaten or harass public health officials (7). Additionally, there must be a better reporting system for acts of violence toward officials. This will help to account for violent incidents and ensure that punitive actions are taken. A 50-statewide survey showed that states vary significantly in their punitive statutes to protect public health officials (30). Creating more cohesive laws that protect public health officials might help to tranquilize national violence toward this targeted population.

Kalmoe et al. showed that when political leaders discourage violence from their followers, it has a strong effect on their behavior (31). Although the politicization of the pandemic has had a negative impact thus far, if more political leaders leveraged their power to stand by public health officials, it could reduce violence in the future (22).

Sharing experiences and communicating openly can also combat the spread of misinformation and increase public awareness of the officials' experiences (1, 23). Evidence shows that when people understand the meaning behind public health policy decisions, there tends to be more support for these policies (26). Therefore, providing public health officials with an opportunity to discuss their decisions may help to ease frustration on a local and state level.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, only nine public health officials were included in the focus groups so that participants could feel safe and promote disclosure. Additionally, there was a low number of participants since this was a pilot study, and we plan to recruit more participants in the future. Additionally, it was difficult to obtain more officials for our study due to the anxiety and stress that this population was enduring at the time. This small sample size limits the results of our study as they may not be generalizable to a broader population of public health officials. There is also a geographical limitation as all participants were from counties throughout California. In future research, it would be beneficial to include participants from across the nation. De Beaumont Foundation reported that the public health workforce is 54% white, 18% Hispanic, 15% Black, and 7% Asian (25, 26). However, our sample did not include any Black officials, which may have impacted our results. Despite trying to create a safe environment for participants, there is a possibility that some officials still felt uncomfortable sharing personal experiences from the pandemic. Finally, symptoms of PTSD or other mental illnesses could have resurfaced among participants, making it difficult for them to share their perspectives.

Conclusion

Our study and other literature show that public health officials have suffered greatly from violence and harassment throughout the pandemic. Our proposed recommendations and solutions provide a multi-faceted approach to the urgent threats that public health officials continue to face. These solutions can be implemented at the local, state, and national levels to spark change throughout the nation. In order to maintain the integrity of the public health system, it is vital that timely changes are made to protect and support public health officials moving forward. Although the COVID-19 pandemic has been a tragedy for many, it offers a unique opportunity to learn from the weaknesses that caused this intense violence toward public health officials. In doing this, we can work with, rather than against, public health officials to strengthen our public health system and improve our response to national emergencies moving forward.

Data availability statement

This research involved qualitative data that was generated from our various focus groups. We then pulled data from these conversations and included them in our article, including the quotes in Tables 2, 3. However, the raw qualitative data is not able to be shared since it possesses identifiable information from the subjects. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to cml0YS5idXJrZUBtZWQudXNjLmVkdQ==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Southern California, Health Sciences Campus, Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

RB: conceptualized, drafted, and revised the manuscript. AD: drafted, revised, and finalized the manuscript. AA, TM, SD, EH, and LC-K: critically revised the article and drafted the content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by NACCHO through a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Award ID: 78516). The views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily reflect the views of Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Conflict of interest

LC-K was employed by Alala Advisors, LLC.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1175661/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

R.V.B., Rita V. Burke; A.S.D., Anna Distler; PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder; NACCHO, The National Association of County and City Health Officials.

References

1. Dye TD, Alcantara L, Siddiqi S, Barbosu M, Sharma S, Panko T, et al. Risk of COVID-19-related bullying, harassment and stigma among healthcare workers: an analytical cross-sectional global study. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e046620. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046620

2. Funk C, Tyson A, Pasquini G, Spencer A. Americans Reflect on Nation's COVID-19 Response. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center. (2022). Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/07/07/americans-reflect-on-nations-covid-19-response/ (accessed October 15, 2021).

3. Larkin H. Navigating attacks against health care workers in the COVID-19 Era. JAMA Network. (2021) 325:1822–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.2701

4. Leider JP, Pineau V, Bogaert K, Ma Q, Sellers K. The methods of PH WINS 2017: approaches to refreshing nationally representative state-level estimates and creating nationally representative local-level estimates of public health workforce interests and needs. J. Public Health Manage. Pract. (2019) 25:S49–S57. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000900

5. Lieberman DA, McKillop M. Ready or not: protecting the public's health from diseases, disasters, and bioterrorism. In: Trust for America's Health. (2020). Available online at: https://www.tfah.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/2021_PHFunding_Fnl.pdf (accessed October 15, 2021).

6. Hare Bork R, Robins M, Schaffer K, Leider JP, Castrucci BC. Workplace perceptions and experiences related to COVID-19 response efforts among public health workers—public health workforce interests and needs survey, United States, September 2021–2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2022) 71:920–4. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7129a3

7. Delaney TP, Fielding JM, Pittman MA. When the truth becomes the threat: standing in support of our public health officials. In: Public Health Alliance of Southern California. (2020). Available online at: https://phasocal.org/when-the-truth-becomes-the-threat-standing-in-support-of-our-public-health-officials/

8. Mello MM, Greene JA, Sharfstein JM. Attacks on public health officials during COVID-19. JAMA. (2020) 324:741–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.14423

9. Said, C. California health officers facing protests, even death threats, over coronavirus orders. In: San Francisco Chronicles. (2020). Available online at: https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Area-health-officers-confront-harassment-15375304.php

10. Topazian RJ, McGinty E, Han H, et al. 2022 US adults' beliefs about harassing or threatening public health officials during the COVID-19 pandemic. AMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e2223491. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.23491

11. Hall K, Brees K, McCall TC, Cunningham MC, Alford AA. 2020 Forces of Change: The COVID-19 edition. Washington, DC: National Association of County City Health Officials. (2022). Available online at: https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/2020-Forces-of-Change-The-COVID-19-Edition.pdf (accessed October 15, 2021).

12. Morabia, A. Harassment of public health officials. Am J Public Health. (2022). 112: 728–30. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2022.306797

13. Krisberg K. Threatened, harassed, doxxed: public health workers forge on—security teams protecting health officers. Nation's Health. (2021) 51:1–13.

14. Bryant-Genevier J, Rao CY, Lopes-Cardozo B, KoneA, Rose C, Thomas I, et al. Symptoms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation among state, tribal, local, and territorial public health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, March–April 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:947–52. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7048a6

15. Callier JG. The impact of workplace aggression on employee satisfaction with job stress, meaningfulness of work, and turnover intentions. Public Person Manage. (2021) 50:159–182. doi: 10.1177/0091026019899976

16. Gainer DM, Nahhas RW, Bhatt NV, Merrill A, McCormack J. Association between proportion of workday treating COVID-19 and depression, anxiety, and PTSD outcomes in US physicians. J Occup Environ Med. (2021) 63:89–97. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002086

17. Weber L, Barry-Jester A, Smith MR. The associated press. public health officials face wave of threats, pressure amid Coronavirus response. In: Kaiser Family Foundation. (2020). Available online at: https://khn.org/news/public-health-officials-face-wave-of-threats-pressure-amid-coronavirus-response/

18. Ward JA, Stone EM, Mui P, Resnick B. Pandemic-related workplace violence and its impact on public health officials, March 2020–January 2021. Am J Public Health. (2022) 112:736–46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306649

19. Smith MR, Press TA, Weber L, Recht H. Public health experts worry about boom-bust cycle of support. In: Kaiser Family Foundation. (2022). Available online at: https://khn.org/news/article/public-health-experts-worry-about-boom-bust-cycle-of-support/ (accessed April 30, 2022).

20. Ivory D, Baker M. Public health officials in the U.S. need federal protection from abuse and threats, a national group says. In: The New York Times. (2021). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/19/us/public-health-threats-abuse.html

21. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. London: AldineTransaction A Division of Transaction Publishers New Brunswick (USA) and London (UK). (1967).

22. Gollust SE. Supporting the public health workforce requires collective actions to address harassment and threats. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e2223501. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.23501

23. Barry-Jester AM, Recht H, Smith MR, Weber L. Pandemic backlash jeopardizes public health powers, leaders. In: AP News. (2020). Available online at: https://apnews.com/article/pandemics-public-health-michael-brown-kansas-coronavirus-pandemic-5aa548a2e5b46f38fb1b884554acf590 (accessed April 30, 2022).

24. Jackson, DZ. Blaming the COVID-19 messengers: public health officials under siege. In: Union of Concerned Scientists. (2020). Available online at: https://blog.ucsusa.org/derrick-jackson/covid-19-public-health-officials-under-siege/ (accessed April 30, 2022).

25. De Beaumont Foundation. PH WINS: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: rising stress and burnout in public health. In: Public Health Workforce and Interest Survey. (2021). Available online at: https://debeaumont.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2022/03/Stress-and-Burnout-Brief_final.pdf (accessed April 30, 2022).

26. Morain S, Mello MM. Survey finds public support for legal interventions directed at health behavior to fight noncommunicable disease. Health Aff (Millwood). (2013) 32:486–96. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0609

27. Krueger J. Proposed limits on public health authority: dangerous for public health. In: The Network for Public Health Law Webinar. (2021). Available online at: https://www.networkforphl.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Proposed-Limitson (accessed October 27, 2022).

28. Fraser MR. Harassment of health officials: a significant threat to the public's health. Am J Public Health. (2022) 112:728–730.

29. COVID scientists in the public eye need protection from threats. Nature. (2021). 598:236. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-02757-3

30. Torton B. 50 State survey: legal protections for public health officials. In: The Network for Public Health Law. (2020). Available at: https://www.networkforphl.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/50-State-Survey-Legal-Protections-for-Public-Health-Officials.pdf (accessed April 30, 2022).

Keywords: COVID-19, harassment, violence, public health, California, doxing

Citation: Burke RV, Distler AS, McCall TC, Hunter E, Dhapodkar S, Chiari-Keith L and Alford AA (2023) A qualitative analysis of public health officials' experience in California during COVID-19: priorities and recommendations. Front. Public Health 11:1175661. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1175661

Received: 27 February 2023; Accepted: 09 August 2023;

Published: 13 September 2023.

Edited by:

Meghna Ranganathan, University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Adam Hege, Appalachian State University, United StatesEduardo Siqueira, University of Massachusetts Boston, United States

Copyright © 2023 Burke, Distler, McCall, Hunter, Dhapodkar, Chiari-Keith and Alford. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rita V. Burke, cml0YS5idXJrZUBtZWQudXNjLmVkdQ==

Rita V. Burke

Rita V. Burke Anna S. Distler

Anna S. Distler Timothy C. McCall

Timothy C. McCall Emma Hunter4

Emma Hunter4 Aaron A. Alford

Aaron A. Alford