95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 26 April 2023

Sec. Life-Course Epidemiology and Social Inequalities in Health

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1136744

This article is part of the Research Topic Psychosocial, Behavioral, and Clinical Implications for Public Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic View all 16 articles

Gary Ka-Ki Chung1,2*

Gary Ka-Ki Chung1,2* Yat-Hang Chan1

Yat-Hang Chan1 Thomas Sze-Kit Lee3

Thomas Sze-Kit Lee3 Siu-Ming Chan4

Siu-Ming Chan4 Ji-Kang Chen5

Ji-Kang Chen5 Hung Wong1,5

Hung Wong1,5 Roger Yat-Nork Chung1,2,6

Roger Yat-Nork Chung1,2,6 Esther Sui-Chu Ho3

Esther Sui-Chu Ho3Background: Adolescents, especially the socioeconomically disadvantaged, are facing devastating psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic during their critical developmental period. This study aims to (i) examine the socioeconomic patterning of the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing, (ii) delineate the underlying mediating factors (i.e., overall worry about COVID-19, family's financial difficulty, learning problems, and loneliness), and (iii) explore the moderating effect of resilience in the inter-relationship among adolescents under COVID-19.

Methods: Based on maximum variation sampling of 12 secondary schools of diverse socioeconomic background in Hong Kong, 1018 students aged 14-16 years were recruited and completed the online survey between September and October 2021. Multi-group structural equation modeling (SEM) by resilience levels was employed to delineate the pathways between socioeconomic position and the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing.

Results: SEM analysis showed a significant total effect of socioeconomic ladder with the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing during the pandemic in the overall sample (β = −0.149 [95% CI = −0.217 – −0.081], p < 0.001), which operated indirectly through learning problems and loneliness (both p < 0.001 for their indirect effects). Consistent pattern with stronger effect size was observed in the lower resilience group; nonetheless, the associations were substantially mitigated in the higher resilience group.

Conclusion: In addition to facilitating self-directed learning and easing loneliness during the pandemic, evidence-based strategies to build up resilience among adolescents are critical to buffer against the adverse socioeconomic and psychosocial impacts of the pandemic or other potential catastrophic events in the future.

With the emergence of new variants of concern, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread across the globe. Apart from the significant disease burden and far-reaching economic consequences, an extensive body of evidence suggests that the pandemic has exposed and amplified the underlying social inequalities in societies. In addition to the higher incidence and mortality in the disadvantaged communities (1) the broader impact of the pandemic on social determinants of health and the associated health inequalities have also been widely observed, (2) even in regions such as Hong Kong with relatively less severe outbreak due to the differential impact of the mandatory COVID-19 containment measures across the socioeconomic ladder (3–6).

In particular, adolescents are facing detrimental psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic during their critical developmental period (7, 8) especially for the socioeconomically disadvantaged (9, 10) Under the ongoing epidemic, prolonged school closure and stringent social distancing policies exacerbated the psychosocial wellbeing of adolescents and a range of social conditions such as learning opportunities (11, 12) social relationships and connectedness,(13, 14) as well as worries on the pandemic and sense of financial insecurity (15, 16). While most existing studies focus on one specific type of these social conditions, few examined the full picture on how different social conditions during the pandemic are socioeconomically patterned and hence disproportionately worsen the psychosocial wellbeing of adolescents. To inform policy entry points for interventions to mitigate the socioeconomic inequalities in psychosocial wellbeing during the pandemic, it is indispensable to identify the social conditions that are most severely affected by the pandemic among adolescents across the socioeconomic ladder.

Despite the well-documented evidence on the inequitable psychosocial impact of COVID-19, the potential heterogeneity in the socioeconomic patterning of psychosocial wellbeing deserves further investigation into why some adolescents, even if of similar socioeconomic background, have fared better than the others in response to COVID-19. Notably, as highlighted by Dvorsky et al. (17) the resilience of adolescents plays a crucial role in mitigating or even evading the social and mental health challenges under the pandemic, where a higher level of self-resilience facilitates successful adaptation, coping, and recovery in the context of the COVID-19-induced psychosocial distress. While existing COVID-19 studies support the protective effect of resilience on psychosocial wellbeing and its effect modification on certain psychosocial risk factors (18–21), whether resilience status could buffer the impacts of socioeconomic position on psychosocial wellbeing and its determinants remains understudied.

In light of the aforementioned knowledge gaps, the present study aims to (i) assess the association between socioeconomic position and the worsening of psychological wellbeing among adolescents, (ii) delineate how different psychosocial determinants disrupted by the pandemic mediate any observed association between socioeconomic position and the worsening of psychological wellbeing, and (iii) explore the potential moderating effect of resilience on the associations and mediating roles.

Data were collected from a purposive sample of 12 secondary schools of different socioeconomic background (see the socioeconomic classifications in Supplementary Table 1) in Hong Kong via online survey between September and October 2021 (22). Invitation letters were sent to members of the Hong Kong Association of the Heads of Secondary Schools (established by dedicated secondary school principals with a vision to enhance professionalism and the understanding of education in secondary schools) to recruit all Secondary 3 students enrolled to each participating school (equivalent to Grade 9 in the United States or Year 10 in the United Kingdom). Among the 1,467 enrolled Secondary 3 students, 1,254 students were successfully surveyed with a response rate of 85.48%. According to the pre-determined inclusion criteria on age range, 1,095 students aged 14–16 years who consented to participate were eligible for this study. After excluding 77 students with incomplete responses, 1,018 students were included for analysis.

Information on respondents' self-perceived socioeconomic ladder, psychosocial wellbeing and related determinants during COVID-19, resilience status, as well as other socio-demographic and health factors were collected for analyses, with details listed below.

The self-perceived family's socioeconomic position of respondents was measured using the social ladder measure of the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status – Youth Version (23). Respondents was asked to mark the rung that best represents where their family would be on a socioeconomic ladder ranging from rung 1 (the worst off) to rung 10 (the best off) on a 10-point Likert scale. The MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status – Youth Version was adopted as a previous systematic review showed that it is most strongly associated with health outcomes related to psychological processes (24) whereas, previous studies also showed its superior role over objective socioeconomic measures in predicting health outcomes such as self-rated health, depression, and wellbeing among adolescents (24). The socioeconomic ladder was re-categorized into six groups according to the reported score (i.e., ≤3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and ≥8) for analysis.

To assess the change in psychosocial wellbeing, respondents were asked how much more/less they have felt during the pandemic when compared with the time before COVID-19 in terms of (i) relaxed, (ii) confident about future, (iii) cheerful, (iv) anxious/stressed, and (v) hopeless with five ordinal options (i.e., 1= much less; 2 = somewhat less; 3 = about the same; 4 = somewhat more; 5 = much more), which were adopted and modified from the COVID-19 Adolescent Symptom & Psychological Experience Questionnaire. (25) The five selected items captured both positive and negative emotions for a more comprehensive assessment because psychosocial wellbeing refers not only to a high level of positive affect but also a low level of negative affect (26). The latent construct on the ‘worsening of psychosocial wellbeing' was created based on these five items, of which the first three positively worded items were reversely coded for analysis to consistently show the results in one direction.

Four domains of psychosocial determinants during COVID-19 were analyzed as potential mediators of the association between socioeconomic ladder and the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing, which included (i) overall worry about COVID-19, (ii) family's financial difficulty, (iii) learning problems, and (iv) loneliness.

The first two domains were measured using single-item questions. Regarding overall worry about COVID-19, respondents were asked how worried they were about the local COVID-19 situation with five ordinal options (i.e., 1 = not at all; 2 = slightly; 3 = moderately; 4 = very; 5 = extremely). As for family's financial difficulty, respondents were asked to what extent the changes related to the COVID-19 outbreak have created financial problems for their family with five ordinal options (i.e., 1 = not at all; 2 = slightly; 3 = moderately; 4 = very; 5 = extremely). The latter two domains were measured as latent constructs. Regarding learning problems, respondents were asked to what extent they experienced the following problems including (i) internet access, (ii) finding a quiet place to study, (iii) understanding my school assignments, and (iv) finding someone who could help me with my school work, each with four ordinal options (i.e., 1 = never; 2 = sometimes; 3 = often; 4 = always). Loneliness was measured using the UCLA 3-item loneliness scale (27) on (i) feeling that you lack companionship, (ii) feeling left out, and (iii) feeling isolated from others, each with three ordinal options (i.e., 1= hardly ever; 2 = some of the time; 3 = often).

As a potential moderator for stratified analyses, resilience was measured using the 6-item Brief Resilience Scale which assesses the ability to bounce back or recover from adversities and to cope with health-related stressors (28). Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” with a possible average score ranging from 1 to 5. The score was then divided into the “higher resilience” and “lower resilience” groups using the sample mean score as the cut-off to ensure similar sample size between the two resilience groups.

Descriptive statistics of respondents were derived using mean with standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and count with percentages for categorical variables. Confirmatory factor analyses and reliability tests were performed for the latent constructs (i.e., worsening of psychosocial wellbeing, learning problems, and loneliness) to ensure that each of these latent constructs was well-explained by its corresponding observed variables. The minimum acceptable factor loading of the observed variables is 0.30 (29). Separate correlation matrices of the aforementioned variables and constructs were derived for the overall sample, lower resilience group, and higher resilience group.

The inter-relationship among socioeconomic ladder, psychosocial determinants, and the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing during COVID-19 was examined using structural equation modeling (SEM), with adjustments for gender, household size (i.e., six groups ranging from “1” to “6 or above”), and baseline self-reported health status (i.e., a retrospective recall of health status before COVID-19 based on a five-point scale ranging from “poor” to “excellent”). In addition, multi-group SEM analysis was employed to assess the potential heterogeneity of the inter-relationship across the lower and higher resilience groups, which was tested based on the χ2 difference between the unconstrained model and structural weight model (i.e., assuming all the paths are equal between the two resilience groups).

We obtained the regression weights of variables as well as the direct and indirect effects on the endogenous variables. Since there are multiple potential mediators in the SEM model, covariance was specified in each of the possible pairs so that the resulted indirect effect of each mediator would be adjusted for the effects of all other mediators. Bootstrapping of 2000 samples and 95% bias-corrected confidence level (CI) were used to estimate the indirect paths. We also estimated the goodness-of-fit of the SEM model, where a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value below 0.08 is deemed having a good model fit (30). Other goodness-of-fit indices, including comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), are considered to be satisfactory if they are above 0.90 (31) and superior if they are above 0.95. (30) The adjusted GFI (AGFI) are considered acceptable if the value is above 0.90 (30, 31). SPSS and AMOS version 26 were employed for statistical analyses. All statistical tests were two-tailed with a significant level of 0.05 unless specified.

Table 1 shows the basic characteristics of our 1018 sampled secondary school students aged 14–16 years (54.0% female). Based on the 10-rung socioeconomic ladder, the respective proportions of those who rated ≤3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and ≥8 were 11.0, 13.4, 31.8, 20.5, 13.1, and 10.2%. Regarding the change in psychosocial wellbeing, 22.6% felt less relaxed, 32.6% felt less confident about the future, 21.6% felt less cheerful, 35.6% felt more anxious or stressful, and 17.1% felt more hopeless during COVID-19. Descriptive statistics on resilience, overall worry about COVID-19, family's financial difficulty, learning problems, loneliness, and other demographic factors and health status are also reported in Table 1.

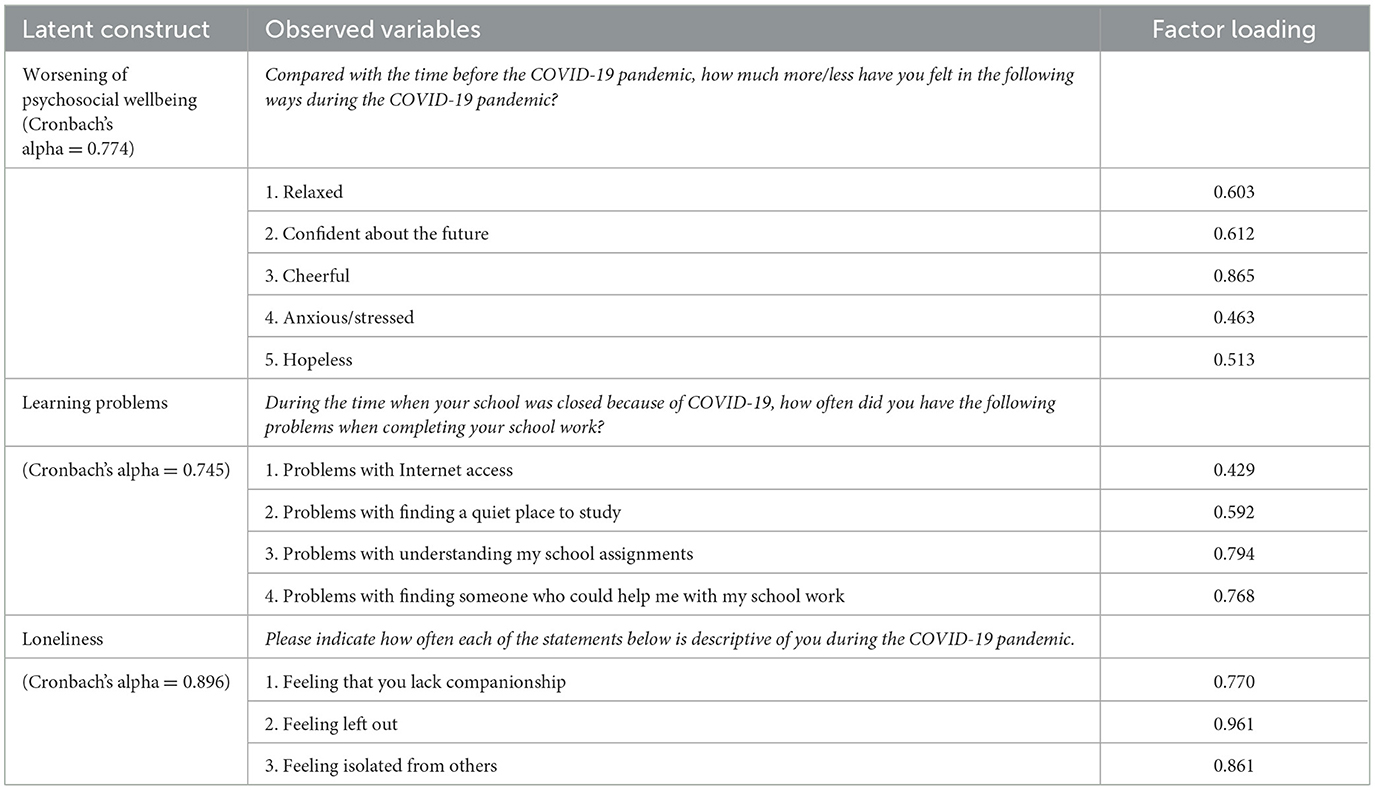

Table 2 presents the standardized factor loadings of the three latent constructs, which ranged from 0.463 to 0.865 for worsening of psychosocial wellbeing (covariance between the last two items was specified as they were negatively worded), from 0.429 to 0.794 for learning problems, and from 0.770 to 0.961 for loneliness. Acceptable reliability was observed for the three latent constructs (Cronbach's alpha = 0.774, 0.745, and 0.896, respectively).

Table 2. Standardized factor loadings of observed variables on latent constructs based on separate confirmatory factor analyses.

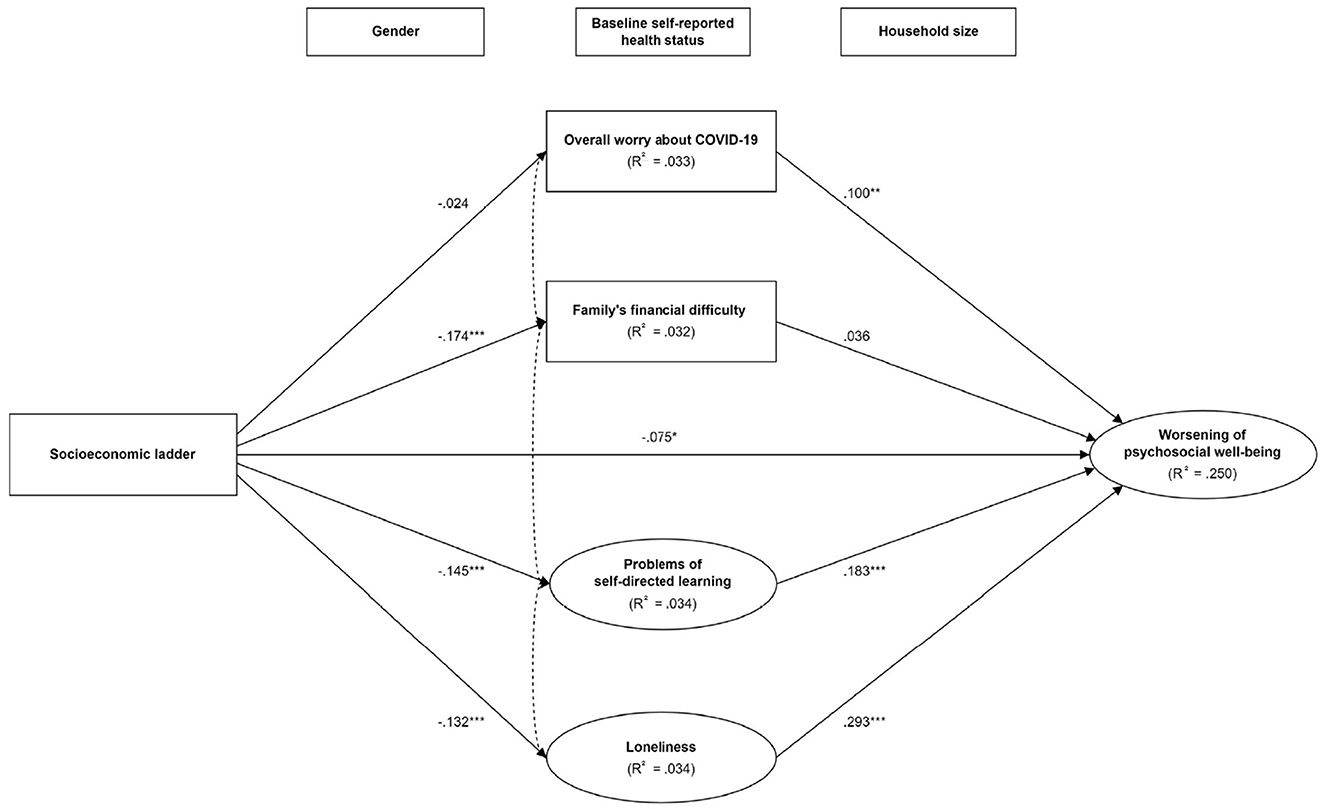

Table 3 displays the correlation matrices of all variables and constructs in the overall sample, lower resilience group, and higher resilience group. The resultant SEM model on the overall sample yielded satisfactory model fit to the data, with χ2 (df = 104, N = 1018) = 344.517, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.048, RMR = 0.032 CFI = 0.954, IFI = 0.955, TLI = 0.933, and AGFI = 0.941, suggesting a satisfactory model fit. After adjustment for gender, household size, and baseline health status, significant total effect between socioeconomic ladder and the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing due to COVID-19 was observed (β = −0.149 [95% CI = −0.217 – −0.081], p < 0.001). As shown in Figure 1, significant direct effects of the socioeconomic ladder were observed with the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing, family's financial difficulty, learning problems, and loneliness during COVID-19, whereas loneliness, learning problems, and overall worry about COVID-19 were significant predictors of the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing. Specifically, the socioeconomic patterning of the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing operated indirectly through learning problems (p < 0.001) and loneliness (p < 0.001).

Figure 1. The mediating pathways between socioeconomic position and the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing in the overall sample. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Model was adjusted for gender, household size, and baseline self-reported health status. Covariance was specified in each of the possible pairs of mediators. The dotted double arrows between mediators are simplified for better readability.

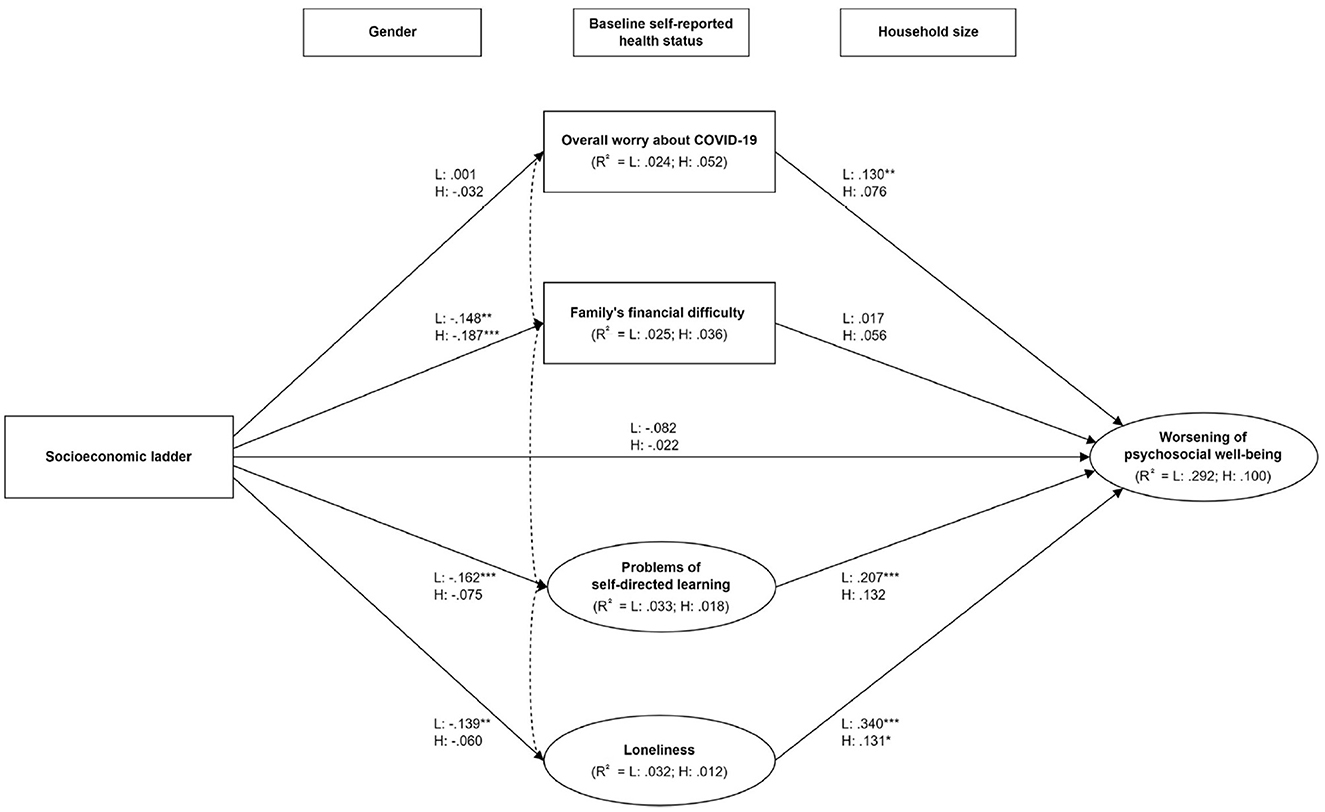

Results from the multi-group SEM analysis showed that the pattern of socioeconomic patterning and predictors of psychosocial wellbeing in the lower resilience group (n = 549) were consistent with that in the overall sample (Figure 2), with stronger effect size in most paths. Nonetheless, the adverse impact of socioeconomic ladder on psychosocial determinants (except for learning problems) and their effects on psychosocial wellbeing were substantially mitigated in the higher resilience group (n = 469). The total effect between socioeconomic ladder and the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing was significant in the lower resilience group (β = −0.166 [95% CI = −0.259 – −0.072], p < 0.001) but not in the higher resilience group (β = −0.053 [95% CI = −0.159 – 0.050], p = 0.322). In addition, the significant χ2 difference (change in χ2 = 48.703, change in df = 33, p = 0.038) between the unconstrained model and structural weight model indicated the difference of models between the lower and higher resilience groups in explaining the paths among socioeconomic ladder, mediators, and the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing. In particular, the indirect effects between socioeconomic ladder and the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing through learning problems (p = 0.001) and loneliness (p < 0.001) were significant only in the lower resilience group but not in the higher resilience group (p = 0.140 and p = 0.130, respectively).

Figure 2. The mediating pathways between socioeconomic position and the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing by resilience levels. L: Lower resilience group; H: Higher resilience group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Model was adjusted for gender, household size, and baseline self-reported health status. Covariance was specified in each of the possible pairs of mediators. The dotted double arrows between mediators are simplified for better readability.

The present study is the first to employ SEM to examine the socioeconomic patterning and psychosocial risks of COVID-19-related disrupted social conditions among adolescents of different resilience level in Hong Kong. In general, the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing was strongly patterned across the socioeconomic ladder because of the greater learning problems and loneliness experienced by socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents during the pandemic. Nonetheless, adolescents of higher resilience have fared better in response to COVID-19 and overcome part of the adverse impact of socioeconomic disadvantage on social conditions and hence their psychosocial wellbeing.

Consistent with the existing literature, our findings supported that adolescents of lower socioeconomic position are more vulnerable to psychosocial distress under the pandemic (9, 10). Given that the outbreaks in Hong Kong are relatively well-controlled with 12,650 cases and 213 deaths by the end of 2021 (32), worries about COVID-19 infection and mortality are not likely explanations for the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing. More plausibly, the stronger psychosocial impact on the socioeconomically disadvantaged might have been resulted from the differential socioeconomic impact of stringent containment measures under the “zero-infection” policy (i.e., preventing imported cases from spreading into the community to maintain zero local infection) in Hong Kong. In particular, the prolonged school closure has posed significant but disproportionate challenges to both their learning experience and psychosocial wellbeing (11, 12, 33). Although distance learning serves as a crucial educational resource and platform during the pandemic, research showed that the shifting from face-to-face to online classes by itself is a psychosocial stressor to students (34). Notably, education disruption due to school closure has resulted in poorer learning gains especially among students from low-income families. Local research also showed that the effectiveness of distance learning was patterned by household income levels (35), whereas, limitations of home environment to support self-directed learning (e.g., disturbance by family members as well as a lack of resources and space) were frequently reported even by the middle class during the pandemic (36). Given the buffering effect of distance learning satisfaction against COVID-19-induced psychosocial stressors (37), it comes as no surprise that the socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents, who faced greater difficulties and dissatisfaction with distance learning during the pandemic, had poorer adjustment in response to COVID-19 and thus suffer from greater psychosocial distress. Our findings echoed with the above studies that the socioeconomic patterning of the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing was partially mediated through the greater learning problems among the socioeconomically disadvantaged.

In addition to learning problems, the extent of loneliness during the pandemic appeared to explain part of the association between socioeconomic position and psychosocial wellbeing among adolescents. While the stringent social distancing measures imposed by the Hong Kong government during the waves of severe local outbreaks [e.g., school closure, prohibition on group gatherings of more than two/four people in public places and dine-in services at night, and closure of leisure facilities and entertainment premises, etc. (38)] have served their purpose of containing the spread of COVID-19, they also seriously disrupted the social life of adolescents. As an inadvertent consequence of social distancing measures, loneliness is particularly problematic for adolescents due to the criticality of peer support and the formation of social identity during their developmental stage (39), which in turn exacerbated the psychosocial impacts of COVID-19 (13, 40). The greater susceptibility to loneliness among socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents could possibly be attributed to the fewer quality time with and perceived support from family and friends when confined at home (16), inadequate private space for social activities (41), higher vulnerability to the harmful use of social media (42), and greater difficulty developing new hobbies to distract themselves from loneliness (43). These speculations accord with the fundamental cause theory that people of lower social status lack capabilities and resources, such as money, space, social capital, digital literacy, and other health and social advantages, to overcome stressors and improve psychosocial wellbeing (44, 45).

Our findings have provided insights on several potential entry points for interventions to buffer the psychosocial impact of further outbreaks and school closures on adolescents. To facilitate self-directed learning, feasible approaches include providing students with broadband internet access and technical support for distance learning, interactive tutorials, and counseling services for need assessment (34, 37), whereas to ease loneliness, addressing maladaptive social cognition as well as enhancing students' emotional awareness and reconciliation via improvement on inter-personal and intra-personal skills may be possible options (46, 47). In addition, deep listening and non-judgmental acceptance by parents are crucial to identify emotional issues of adolescents at an early stage (48). Besides, our results on the moderating effect of resilience also highlighted the criticality of resilience building among adolescents, especially after schools re-open as resilience-focused interventions are commonly school-based (49). As suggested by a recent systematic review, schools may be the best setting to develop resilience of students, especially the most disadvantaged group, by providing multiple types of resources including access to material resources and supportive relationships, experience of power and control, social justice, and social cohesion with others, as well as development of desirable personal identity and adherence to cultural traditions (50). In light of this, educators should work with social workers and psychologists to review the current school-based psychosocial support programs, and consider incorporating positive psychology and cognitive behavioral therapy-based approaches into resilience-focused interventions (49). From a more upstream perspective, while the stringent social distancing measures and school closure may be able to protect students from COVID-19 infections, the tremendous cost of these measures on a wide array of social determinants of health should not be overlooked. Previous research has pointed out that the “zero-infection” approach is highly prone to neglect social and health inequities, which is neither ethical nor feasible in the long run (51). Therefore, in addition to allocating extra resources to support the disadvantaged groups, policy makers should carefully consider the impact on social determinants of health when devising a long-term response to COVID-19 so as to balance disease containment with the psychosocial wellbeing, developmental opportunities, and equity of adolescents.

There are several limitations of the present study. First, the cross-sectional design of our survey could not establish temporality for causal inferences. Second, we adopted purposive sampling of schools due to the difficulty in random sampling under the pandemic. Although the selected schools were not a statistically representative sample, we recruited schools of diverse socioeconomic background with considerations for a balanced gender ratio to maximize the qualitative generalizability of our sample. Third, as the assessment of key variables were based on self-reported responses to survey, our results may be subject to recall bias and social desirability bias. Fourth, the goodness-of-fit of the SEM model may be affected by the inclusion of single-item ordinal mediators (i.e., overall worry about COVID-19 and family's financial difficulty). To this end, we have replicated the SEM analysis without these two mediators and the model fit remained satisfactory with χ2 (df = 86, N = 1018) = 301.892, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.050, RMR = 0.033 CFI = 0.957, IFI = 0.958, TLI = 0.940, and AGFI = 0.944. Last, despite adjustment for gender, household size, and baseline health status, residual confounding is possible due to the unavailability of data on history of mental health disorders, lifestyle behaviors, and healthcare access.

Adolescents of lower socioeconomic position, especially those with a lower level of resilience, were at higher risk of experiencing psychosocial distress during the COVID-19 pandemic because of greater learning problems and loneliness under the differential socioeconomic impact of stringent social distancing measures in Hong Kong. In addition to providing distance learning and social support, evidence-based strategies to build up resilience among adolescents are crucial to buffer against the adverse socioeconomic and psychosocial impacts of the pandemic.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

GKKC contributed to literature search, study design, data analysis, result interpretation, and the write-up of the manuscript. YHC and SMC were responsible for study design, data curation, and result interpretation. TSKL contributed to data collection, coordination, and data analysis. JKC was responsible for study design and provided substantial statistical advice on the analyses. HW and RYNC oversaw the project as the co-Principal Investigators, contributed to study design, and result interpretation. ESCH was responsible for data collection, data analysis, and result interpretation. All authors critically appraised and approved the manuscript.

The authors acknowledge funding support from the Worldwide Universities Network (WUN) Research Development Fund 2020. It has no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. GKKC acknowledges the Research Grant Council for its support over his Postdoctoral Fellowship (Ref. No.: PDFS2122-4H02).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1136744/full#supplementary-material

1. Wachtler B, Michalski N, Nowossadeck E, Diercke M, Wahrendorf M, Santos-Hövener C, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities and COVID-19 – A review of the current international literature. J Health Monit. (2020) 5: 3–17. doi: 10.25646/7059

2. Marmot M, Allen J. COVID-19: exposing and amplifying inequalities. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2020) 74:681–2. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214720

3. Chung RY, Chung GK, Marmot M, Allen J, Chan D, Goldblatt P, et al. COVID-19-related health inequality exists even in a city where disease incidence is relatively low. A telephone survey in Hong Kong. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2021) 75:616–23. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-215392

4. Chung RY, Chung GK, Chan SM, Chan YH, Wong H, Yeoh EK, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in mental well-being associated with COVID-19 containment measures in a low-incidence Asian globalized city. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:23161. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02342-8

5. Chung GK, Chan SM, Chan YH, Woo J, Wong H, Wong SY, et al. Socioeconomic patterns of COVID-19 Clusters in low-incidence city, Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. (2021) 27:2874–7. doi: 10.3201/eid2711.204840

6. Chung GK, Chan SM, Chan YH, Yip TC, Ma HM, Wong GL, et al. Differential impacts of multimorbidity on COVID-19 severity across the socioeconomic ladder in Hong Kong: a syndemic perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:8186. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18158168

7. Samji H, Wu J, Ladak A, Vossen C, Stewart E, Dove N, et al. Review: Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth - a systematic review. Child Adolesc Ment Health. (2021). doi: 10.1111/camh.12501

8. Luijten MA, van Muilekom MM, Teela L, Polderman TJ, Terwee CB, Zijlmans J, et al. The impact of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic on mental and social health of children and adolescents. Qual Life Res. (2021) 30:2795–804. doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-02861-x

9. Li W, Wang Z, Wang G, Ip P, Sun X, Jiang Y, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in child mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: First evidence from China. J Affect Disord. (2021) 287:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.009

10. Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Erhart M, Devine J, Schlack R, Otto C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2021). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3721508

11. Colvin MKM, Reesman J, Glen T. The impact of COVID-19 related educational disruption on children and adolescents: an interim data summary and commentary on ten considerations for neuropsychological practice. Clin Neuropsychol. (2021) 36:1–27. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2021.1970230

12. Scott SR, Rivera KM, Rushing E, Manczak EM, Rozek CS, Doom JR. “I Hate This”: a qualitative analysis of adolescents' self-reported challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health. (2021) 68:262–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.11.010

13. Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N. Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2020) 59:1218–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

14. Liu J, Zhou T, Yuan M, Ren H, Bian X, Coplan RJ. Daily routines, parent-child conflict, and psychological maladjustment among Chinese children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Psychol. (2021) 35:1077–85. doi: 10.1037/fam0000914

15. Sarkadi A, Sahlin Torp L, Perez-Aronsson A, Warner G. Children's expressions of worry during the COVID-19 pandemic in sweden. J Pediatr Psychol. (2021) 46:939–49. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsab060

16. Wang MT, Henry DA, Del Toro J, Scanlon CL, Schall JD. COVID-19 employment status, dyadic family relationships, and child psychological well-being. J Adolesc Health. (2021) 69:705–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.016

17. Dvorsky MR, Breaux R, Becker SP. Finding ordinary magic in extraordinary times: child and adolescent resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2021) 30:1829–31. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01583-8

18. Mesman E, Vreeker A, Hillegers M. Resilience and mental health in children and adolescents: an update of the recent literature and future directions. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2021) 34:586–92. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000741

19. Jacobson C, Miller N, Mulholland R, et al. Psychological distress and resilience in a multicentre sample of adolescents and young adults with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2022) 27:201–13. doi: 10.1177/13591045211056923

20. Tal-Saban M, Zaguri-Vittenberg S. Adolescents and resilience: factors contributing to health-related quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:157. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063157

21. Garagiola ER, Lam Q, Wachsmuth LS, et al. Adolescent resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the impact of the pandemic on developmental milestones. Behav Sci. (2022) 12:220. doi: 10.3390/bs12070220

22. Chung GK, Chan Y, Chan S, Chen J, Wong H, Chung RY. The impact of trust in government on pandemic management on the compliance with voluntary COVID-19 vaccination policy among adolescents after social unrest in Hong Kong. Front Pub Health. (2022) 10:992895. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.992895

23. Goodman E, Adler NE, Kawachi I, Frazier AL, Huang B, Colditz GA. Adolescents' perceptions of social status: development and evaluation of a new indicator. Pediatrics. (2001) 108:E31. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e31

24. Quon EC, McGrath JJ. Subjective socioeconomic status and adolescent health: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. (2014) 33:433–47. doi: 10.1037/a0033716

25. Ladouceur CD,. COVID-19 Adolescent Symptom Psychological Experience Questionnaire (CASPE). (2020) Available online at: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/dr2/CASPE_AdolSelfReport_Qualtrics.pdf (accessed December 31, 2022).

26. Diener E. Subjective well-being: the science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am Psychol. (2000) 55:34–43. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34

27. Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res Aging. (2004) 26:655–72. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574

28. Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. (2008) 15:194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972

29. Hair J, Black W, Babin B, Anderson R. Multivariate Data Analysis. Vol 7. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall. (2009).

30. Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Eq Model Multidis J. (1999) 6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

31. Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. (1990) 107:238–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

32. Centre for Health Protection. Latest Situation of Cases of COVID-19. (2020) Available online at: . https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/local_situation_covid19_en.pdf (accessed December 31, 2022).

33. Viner R, Russell S, Saulle R, Croker H, Stansfield C, Packer J. School closures during social lockdown and mental health, health behaviors, and well-being among children and adolescents during the first COVID-19 wave: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. (2022) 176:400–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5840

34. Carreon ADV, Manansala MM. Addressing the psychosocial needs of students attending online classes during this Covid-19 pandemic. J Public Health. (2021) 43:e385–e6. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab101

35. Mok KH, Xiong W, Bin Aedy Rahman HN. COVID-19 pandemic's disruption on university teaching and learning and competence cultivation: Student evaluation of online learning experiences in Hong Kong. Int J Chin Educ. (2021) 10:22125868211007011. doi: 10.1177/22125868211007011

36. Lau EYH, Lee K. Parents' views on young children's distance learning and screen time during COVID-19 class suspension in Hong Kong. Early Educ Dev. (2021) 32:863–80. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2020.1843925

37. Li X, Tang X, Wu H, Sun P, Wang M, Li L. COVID-19-related stressors and chinese adolescents' adjustment: the moderating role of coping and online learning satisfaction. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:633523. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.633523

38. Legislative Council Secretariat,. Updated Background Brief Prepared by the Legislative Council Secretariat for the meeting on 5 February 2021- Measures for the prevention control of coronavirus disease 2019 in Hong Kong 2021. (2021) Available online at: https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr20-21/english/panels/hs/papers/hs20210205cb4-472-4-e.pdf (accessed December 31, 2021).

39. Meeus W, Dekoviic M. Identity development, parental and peer support in adolescence: results of a national Dutch survey. Adolescence. (1995) 30:931–44.

40. Tso IF, Park S. Alarming levels of psychiatric symptoms and the role of loneliness during the COVID-19 epidemic: a case study of Hong Kong. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 293:113423. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113423

41. de Rosa AS, Mannarini T. Covid-19 as an “invisible other” and socio-spatial distancing within a one-metre individual bubble. Urban Design Int. (2021) 26:370–90. doi: 10.1057/s41289-021-00151-z

42. George MJ, Jensen MR, Russell MA. Young adolescents' digital technology use, perceived impairments, and well-being in a representative sample. J Pediatr. (2020) 219:180–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.12.002

43. Mathias K, Rawat M, Philip S, Grills N. “We've got through hard times before: acute mental distress and coping among disadvantaged groups during COVID-19 lockdown in North India - a qualitative study”. Int J Equity Health. (2020) 19:224. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01345-7

44. Riley AR. Advancing the study of health inequality: fundamental causes as systems of exposure. SSM Popul Health. (2020) 10:100555. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100555

46. UNESCO. 2014 regional study on transversal competencies in education policy and practice (phase II) school and teaching practices for twenty-first century challenges: Lessons from the Asia-Pacific region. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2016).

47. Masi CM, Chen HY, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. (2011) 15:219–66. doi: 10.1177/1088868310377394

48. Duncan LG, Coatsworth JD, Greenberg MT, A. model of mindful parenting: implications for parent-child relationships and prevention research. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. (2009) 12:255–70. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3

49. Dray J, Bowman J, Campbell E, Freund M, Wolfenden L, Hodder RK, et al. Systematic review of universal resilience-focused interventions targeting child and adolescent mental health in the school setting. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2017) 56:813–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.780

50. Ungar M, Connelly G, Liebenberg L, Theron L. How schools enhance the development of young people's resilience. Soc Indic Res. (2019) 145:615–27. doi: 10.1007/s11205-017-1728-8

Keywords: adolescents, COVID-19, psychosocial wellbeing, resilience, socioeconomic inequalities

Citation: Chung GK, Chan YH, Lee TS, Chan SM, Chen JK, Wong H, Chung RY and Ho ES (2023) Socioeconomic inequality in the worsening of psychosocial wellbeing via disrupted social conditions during COVID-19 among adolescents in Hong Kong: self-resilience matters. Front. Public Health 11:1136744. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1136744

Received: 03 January 2023; Accepted: 27 March 2023;

Published: 26 April 2023.

Edited by:

Zonglin He, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Hong Kong, ChinaReviewed by:

Birute Strukcinskiene, Klaipeda University, LithuaniaCopyright © 2023 Chung, Chan, Lee, Chan, Chen, Wong, Chung and Ho. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gary Ka-Ki Chung, Z2NodW5nQGN1aGsuZWR1Lmhr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.