94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health, 03 July 2023

Sec. Public Health and Nutrition

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1124173

Yalelet Fentaw Shiferaw1

Yalelet Fentaw Shiferaw1 Desale Bihonegn Asmamaw2

Desale Bihonegn Asmamaw2 Melaku Tadege Engidaw3

Melaku Tadege Engidaw3 Daniel Gashaneh Belay4,5

Daniel Gashaneh Belay4,5 Haileyesus Birhan6

Haileyesus Birhan6 Wubshet Debebe Negash7*

Wubshet Debebe Negash7*Background: Undernutrition is a major public health concern affecting the health, growth, development, and academic performance of adolescents studying in school. During this crucial period, dietary patterns have a vital impact on lifetime nutritional status and health. The problem of undernutrition among particular groups of adolescents attending traditional schools has not previously been studied. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the prevalence of undernutrition and associated factors among adolescents aged 10–19 years attending Orthodox Church schools in northwest Ethiopia.

Methods: An institution-based, cross-sectional study design was employed, with data collected from March 1 to 30, 2021. A simple random sampling technique was used to recruit a total of 848 male attendees of traditional schools. Data were collected via an interviewer-administered semi-structured questionnaire. The nutritional status of participants was assessed using anthropometric measurements. The WHO Anthroplus software was used for analysis. Both bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify the factors associated with nutritional status. The degree of association between the independent variables and the dependent variable was assessed using odds ratios, reported with 95% confidence intervals, and a threshold of p ≤ 0.05.

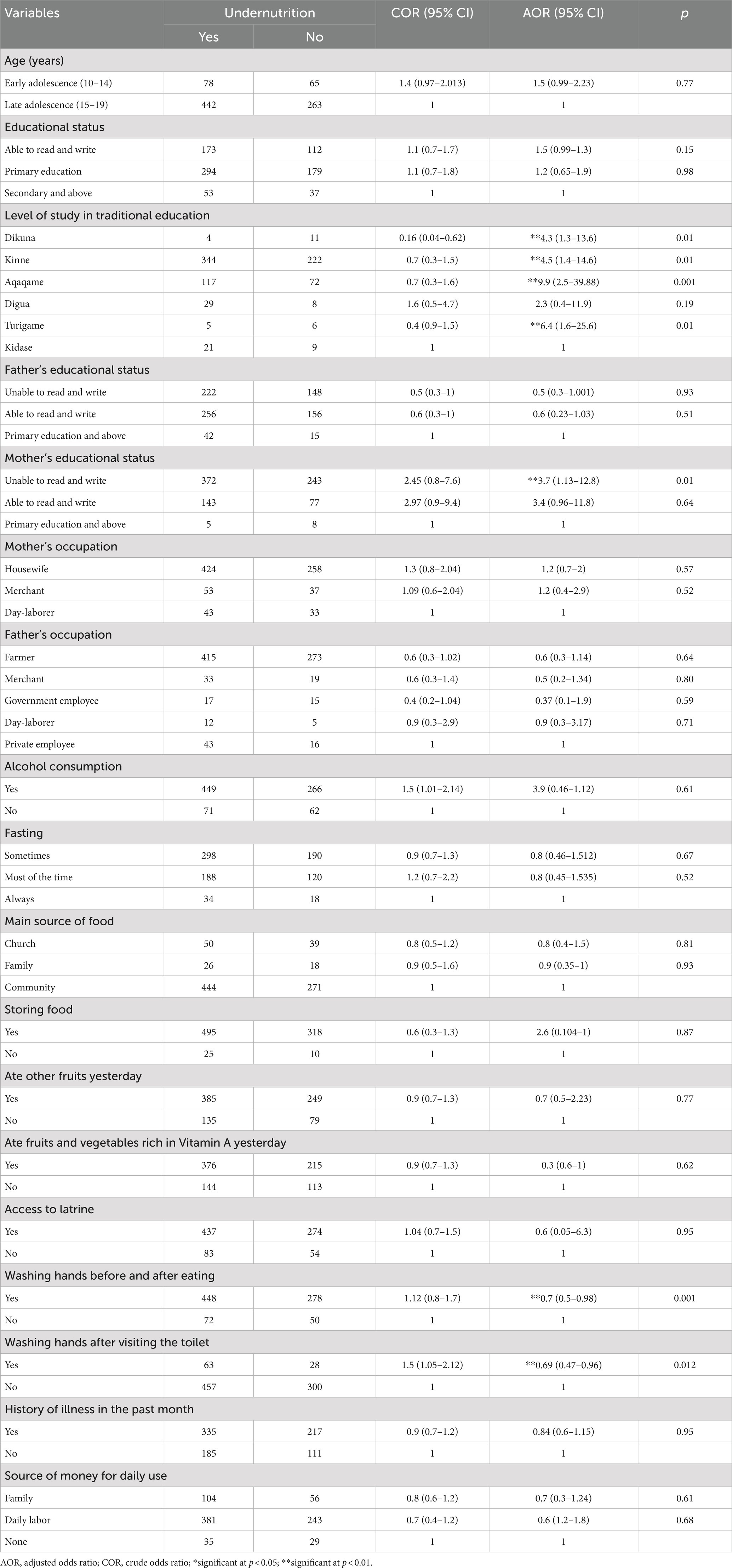

Results: The prevalence of undernutrition was found to be 61.3% [95% CI: 58.1, 64.6]. The likelihood of developing undernutrition was elevated among those adolescents who were following the traditional school levels of dikuna (AOR = 4.3, 95% CI = 1.3, 13.6), kinne (AOR = 4.5, 95% CI = 1.4, 14.6), aquaquame (AOR = 9.9, 95% CI = 2.5, 39.88), tirguame (AOR = 6.4, 95% CI = 1.6, 25.6), and among those whose mothers had no formal education [AOR = 3.7, 95% CI: 1.2, 12.8]. In contrast, those adolescents who always washed their hands after a toilet visit had lower odds of undernutrition than their counterparts [AOR = 0.7, 95%CI: 0.5, 0.98].

Conclusion: More than three out of five participating male adolescents were undernourished. Thus, to improve the nutritional status of adolescents studying in traditional church schools, extensive health education for these adolescents is essential. Moreover, the establishment of well-resourced traditional religious school, equipped for the provision of an adequate, diversified diet, is important. Developing the habit of handwashing after visiting the toilet and before and after food preparation is also recommended for adolescent students.

Adolescence is the transition period between childhood and adulthood, encompassing people aged 10–19 years (1). Adolescents account for a disproportionately large percentage of the population in developing countries (2). There are 1.2 billion adolescents aged 10–19 in the world, forming 18% of the world’s population (3). In Africa, the population of adolescents accounts for more than 265 million people (4).

Growth is faster during adolescence than at any other time; this in turn increases nutritional needs at this juncture, as adolescents gain up to 50% of their adult weight, more than 20% of their adult height, and 50% of their adult skeletal mass during this period (5). Adolescents are a nutritionally vulnerable group for a number of specific reasons, including their high requirements for growth, their eating patterns and lifestyles, their risk-taking behaviors, and their susceptibility to environmental influences (6). Inadequate nutrition in adolescence can potentially retard growth and sexual maturation, although these are also likely consequences of chronic malnutrition in early infancy and childhood (6). Short stature in adolescents resulting from chronic undernutrition is associated with reduced lean body mass and deficiencies in muscular strength and working capacity (7, 8).

Studies in Ethiopia on the magnitude of the problem of undernutrition among female adolescents have reported rates ranging from 14.4% in Gondar (9) to 19.5% in the town of Dessie (10). In addition, 29.2% of adolescents have been reported to be stunted, and 30.4% to exhibit wasting (11, 12). Systematic reviews have also revealed that the rates of stunting and underweight among adolescent girls are 20.7 and 27.5%, respectively (13). Furthermore, a recent demographic study has revealed that the prevalence of undernutrition among adolescent girls and young women is 25% (14). Factors such as large family size, occupation, diet-related knowledge, and monthly per capita income are contributors to adolescent malnutrition (15, 16). Moreover, rural residence, an unprotected source of drinking water, a lack of latrine, low dietary diversity score, and mother illiteracy have been identified as contributing factors for adolescent undernutrition (13, 17).

Teaching activities conducted by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church has been relaying traditional teachings and schools of thoughts for centuries; these teachings form a deeply embedded component of religious education, life, and ethos in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. The types of teaching provided include church singing and movement (aquaquame), poetry (kinne), and commentaries on the Bible and on the writings of the Church fathers and the monks. In addition to the many centuries of church teachings, traditional Ethiopian Orthodox education has been a deeply embedded component of education, culture, and social activities across the country (18). However, the life of students undergoing traditional teaching is hard and demanding for contemporary boys. For example, they leave their family; they beg for their food among families of the neighborhood, but also sometimes far away; and most of the time, their daily life as students within the church tradition is one of poverty and is very demanding (19).

Religious youths are less likely than other youths to engage in behaviors that are potentially detrimental to their health (20). In terms of the consumption habits of church followers in Ethiopia, religious culture here places a total taboo on the use of animal products such as milk and butter during fasting (21).

Although a great deal of research has been carried out to understand the nutritional status of formally enrolled school students during the period of adolescence in Ethiopia (22–25), to the best of the investigators’ knowledge, there has been no attempt to understand the nutritional status of male adolescents studying in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. The neglect of this topic indicates that students receiving education in the setting of traditional schools have been ignored by research efforts. Although nutritional studies have been conducted in modern schools, it is also crucial to investigate the magnitude of the problem of undernutrition among adolescents in these traditional schools. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of undernutrition and its associated factors among attendees of Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church traditional schools. The findings should alert policymakers, program developers, and healthcare workers to the need for appropriate and science-based interventions, such as boarding arrangements including the adequate provision of school food, would reduce the burden on students of searching for food in the community. Additionally, the results will serve as a baseline for future researchers within the broad area of such religious settings.

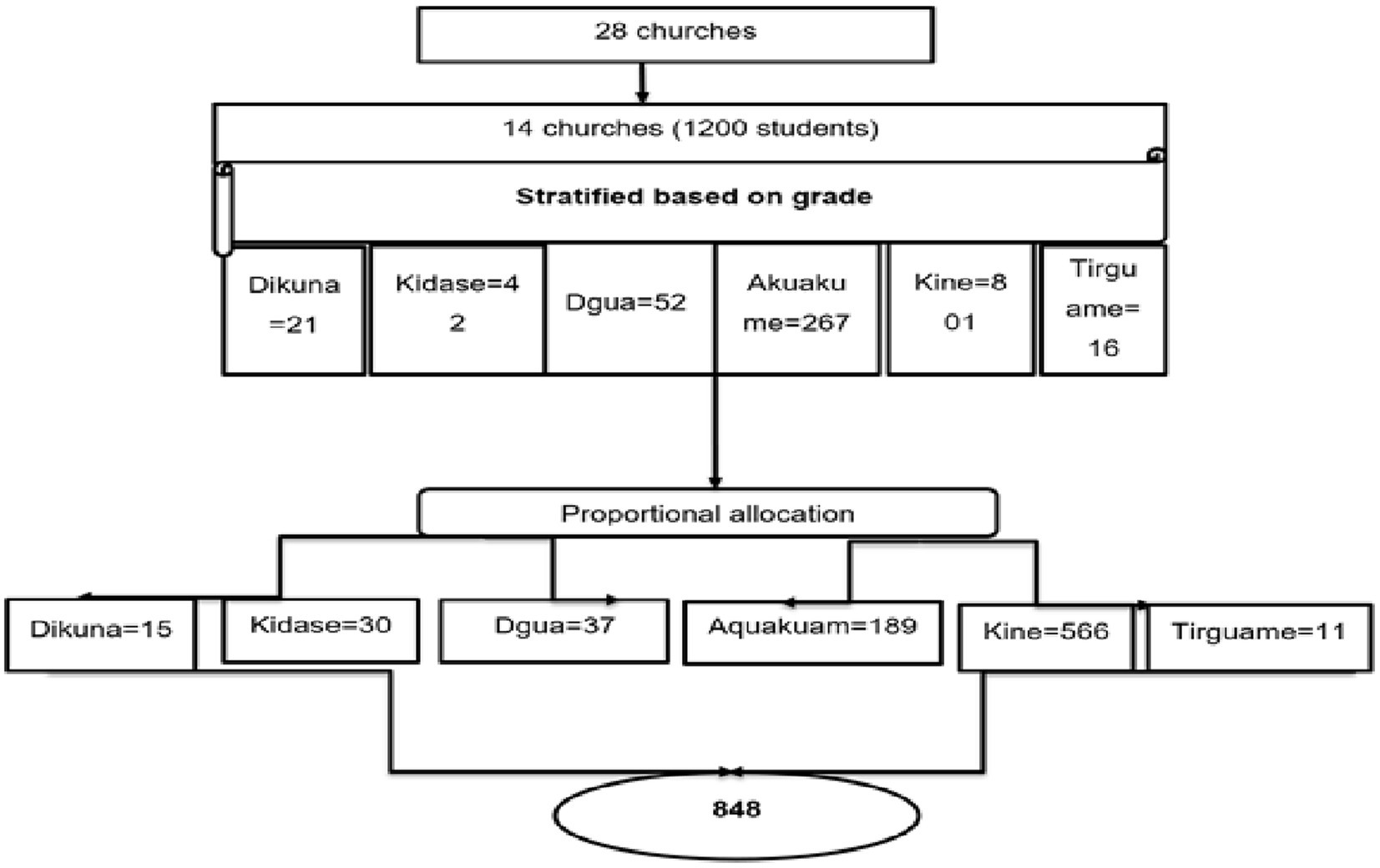

Figure 1. Schematic presentation of the sampling procedure for recruitment of adolescents in northwest Ethiopia, 2021.

An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Gondar city, northwest Ethiopia, from March 1 to 30, 2021. The institutions included in the study were specifically the orthodox churches. Gondar is one of the ancient cities and is located 728 km from Addis Ababa in northwest Ethiopia. The city has 28 orthodox churches with schools, and there are approximately 3,500 male adolescents studying at the traditional schools across these 28 churches (Figure 1).

The source population for this study consisted of all male students enrolled in traditional schools who were followers of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church in Gondar city. Almost all of these students are adolescents (aged 10–19 years). Those male adolescents who were available during the study period were included in the study population.

The required sample size for examining undernutrition was determined using the formula for a single population proportion with the following assumptions:

p = 50% (this value was taken due to a lack of previous research among traditional school students aged 10–19 years).

Z (level of significance) = 95%.

d (margin of error) = 5%.

Adding a 10% non-response rate gave a total required sample size of 424; considering the design effect of accommodating two different levels of education, the final sample size required for the study was 848.

The outcome variable of this study was the nutritional status of male adolescents who had attended a traditional school in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. Nutritional status was classified based on the World Health Organization (WHO) BMI-for-age classification of malnutrition in adolescents, under which a Z score < −3 represents severe malnutrition, Z > −3 and < −2 represents moderate malnutrition, Z > −2 < −1 represents mild malnutrition, and Z > −1 and < 1 score is normal nutrition status.

In addition to this outcome variable, the independent variables measured in this study were: sociodemographic factors (age, household income, educational status, and occupation); nutrition-related factors (hygiene, eating habits, eating pattern); environmental factors (sanitation, housing conditions, latrine access, water source); and other factors, such as social support, duration of fasting, alcohol consumption, food eating practices, history of diarrheal illness, vomiting, food sources, availability of storage for a variety of food, and number of students per house.

For this study, traditional school attendees were considered to be those students of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church schools whose age fell within the range of 10–19 years. The aspects of traditional education within these schools were classified as follows: dikuna (baseline and first level of education), kinne (church poetry), aquaquame (lessons on church hymns of differing complexity), dgua (the book of songs), tirguame (interpretation of church books), and kidase (traditional chanting) (26, 27).

Fasting was considered to entail abstaining from all food for 13 h (mid night to 1 pm during the daytime) within a 24-h period.

Those who had three or more episodes of diarrhea in the 24 h prior to the survey were considered to have diarrhea.

For this study, adolescents were considered to consume alcohol if they drank alcohol (tella, arekie, or beer) any number of times per week; alcohol consumption was coded as 1 = yes and otherwise 0 = no.

This was assessed based on whether the respondent reported eating until satiety or not.

The frequency of eating breakfast was classified as sometimes (only on Saturday and Sunday), often (on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday, and Sunday), or always (every day of the week).

Prior to collection of any data, official permission was obtained from North Gondar Church Administration Office and from the director of each traditional church school; sampling units (adolescent students) were then identified and designated with their own code corresponding to their church. Eight graduate students of health science were provided with training and were responsible for the data collection and supervisory processes for all 28 churches. The primary investigator provided 2 days of training for the data collectors and supervisors on how to conduct anthropometric measurements, the MUAC, and interview techniques. A data collection manual was prepared and provided to the data collectors and supervisors during the period of data collection. The data were collected by the trained data collectors using a face-to-face interview technique employed a coded, structured questionnaire.

The nutritional status of study participants was determined using the Measure Anthrop software package based on weight and height measurements taken according to standard procedures described by the WHO. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a Seca electronic scale with the adolescent wearing a uniform or light clothing and without shoes. Weight was recorded twice and the mean value was used in the analyses. The scale was checked for accuracy with known standard weights (e.g., 2 kg) after every measurement. A wooden stand placed on a flat surface was used to measure each individual’s height. The subject stood on the base of the device with feet together (without shoes). The shoulders, buttocks, and heels were required to touch the vertical measuring board. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm; it was recorded twice, and the mean value was calculated, recorded, and entered into the analysis. Computed Z-scores of Body Mass Index for age (BMIAZ) and height for age (HAZ) were used to assess thinness and stunting, respectively.

The questionnaire was first prepared in English and then translated to the local language (Amharic) by an expert and back-translated into English. The aim of the study was explained to the church leaders and adolescents. The quality of the data was assured by the use of a properly designed and pre-tested questionnaire and through standard and appropriate supervision of the data collectors. Overall supervision was provided by the principal investigator. For standardization of the questionnaire, a pre-test of the questionnaire and anthropometric measurements was performed at one church that was not part of the study. An appropriate modification was made after analyzing the pre-test results before proceeding with data collection. Completed questionnaires were reviewed and checked for completeness and relevance by the supervisors and principal investigator, and any necessary feedback was offered to the data collectors within a few days.

All the returned questionnaires were checked manually. The data were cleaned before being coded and entered into WHO Anthro Plus, Epi Info version 7, and SPSS software version 20. The collected data were cleaned and checked again, descriptive statistics were computed, and bivariate and multivariate analyses were conducted. Body mass index (BMI) was computed as weight (kg) per meter of height squared (m2) (kg/m2). The 2007 WHO growth reference was used as a standard reference during analysis. Crude and adjusted ORs, with their associated 95% CIs, were computed to assess the presence of associations between the explanatory variables and the outcome variable. Multicollinearity was assessed, and the data were found to contain no multicollinearity (mean VIF = 2.14). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to test for model fit; the goodness of fit was found to be p = 0.51, which is appropriate for logistic regression models.

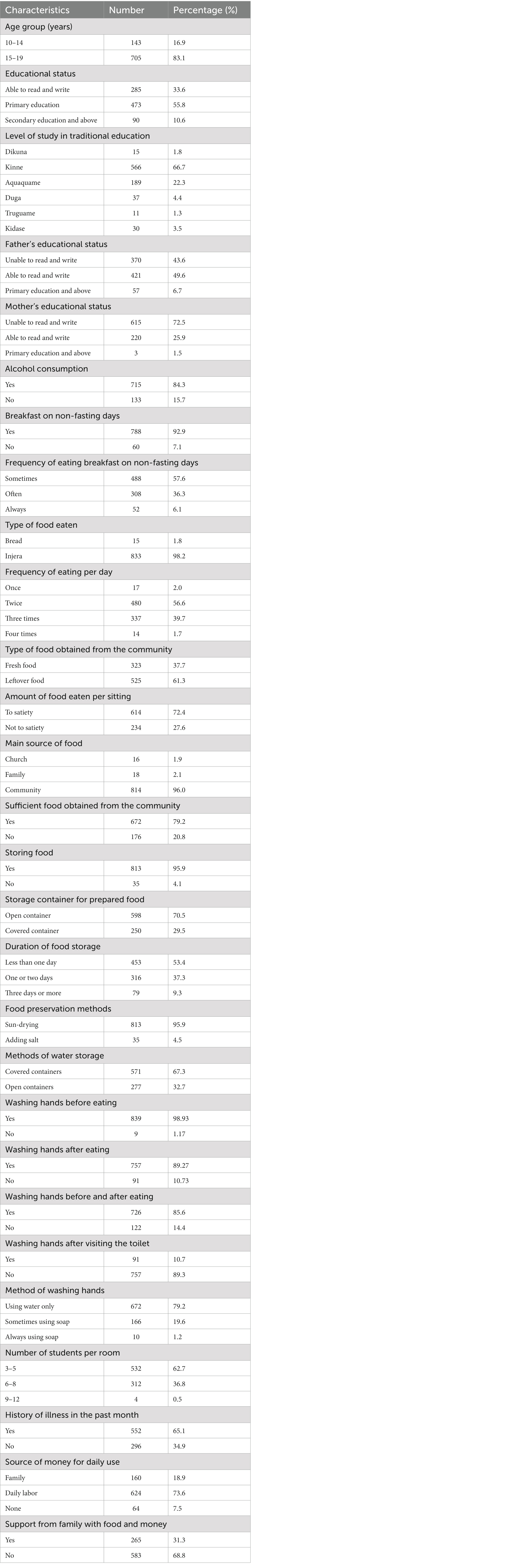

A total of 848 male adolescent respondents were included in the study. The majority of the respondents (705; 83.1%) were in late adolescence. Regarding the formal educational status of the students, 370 (43.6%) were able to read and write and 421 (49.6%) had completed their primary education. Regarding their level of traditional education, 566 (66.7%) were studying at the kinne level and 189 (22.3%) were studying aquaquame.

The main source of food (for 814 respondents; 96%) was the community. Among all study participants, 757 (89.3%) reported not washing their hands after visiting the toilet. The majority of the participants (65.1%) had a history of illness (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics and eating/fasting-related habits of male adolescents studying in traditional schools of the Orthodox Tewahedo Church, northwest Ethiopia, 2021.

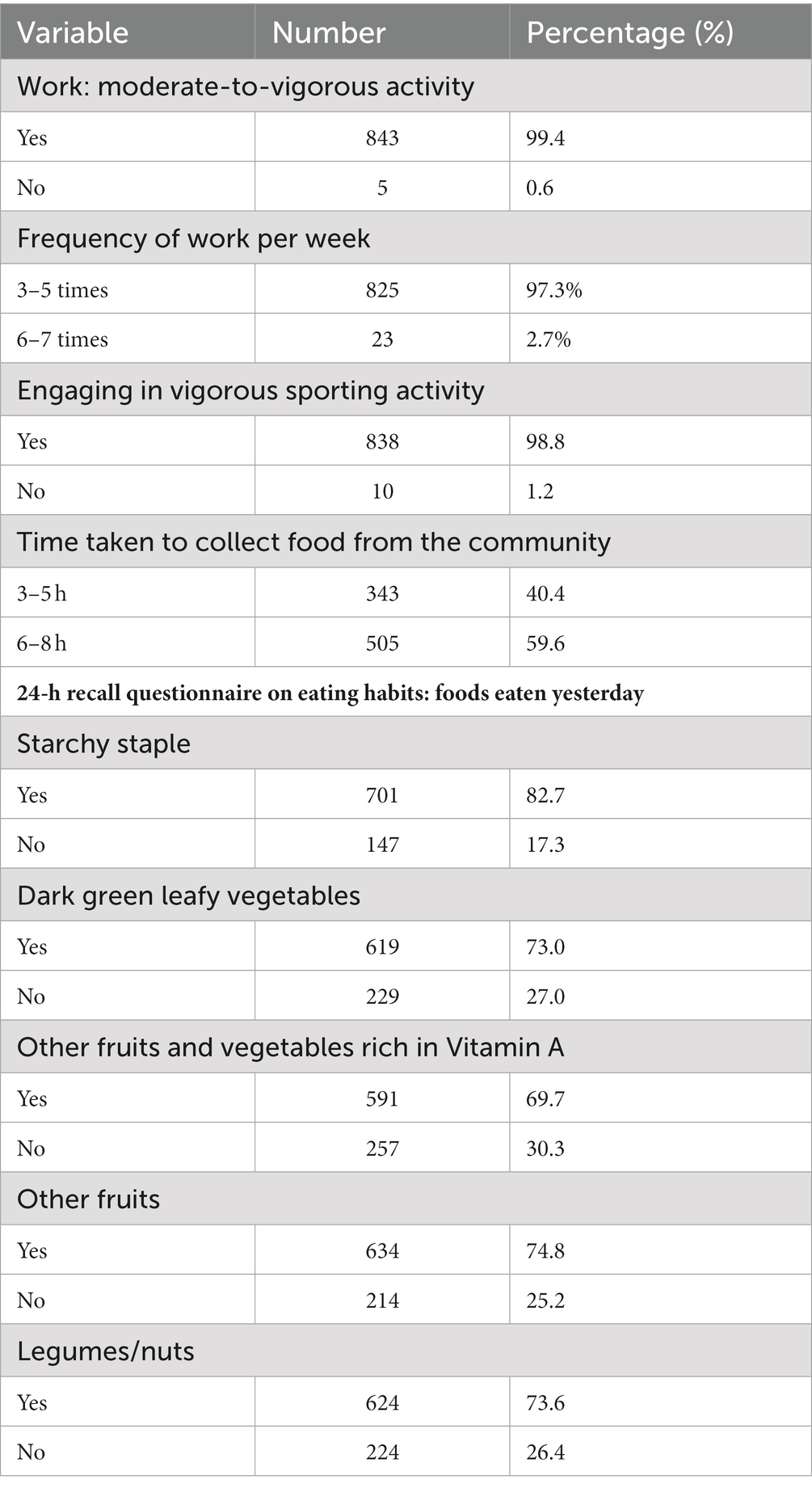

In terms of physical activity, the majority (99.4%) of respondents reported engaging in work involving moderate-to-vigorous activity, and 333 (39.3%) reported working 7 times per week. In their responses to a 24-h recall history of eating (Table 2), none of the respondents (0%) reported having consumed fresh meat, organ meat, eggs, or milk within the last 24 h.

Table 2. Physical activity and frequency of consumption of food groups among adolescents studying in traditional schools, Gondar, 2021.

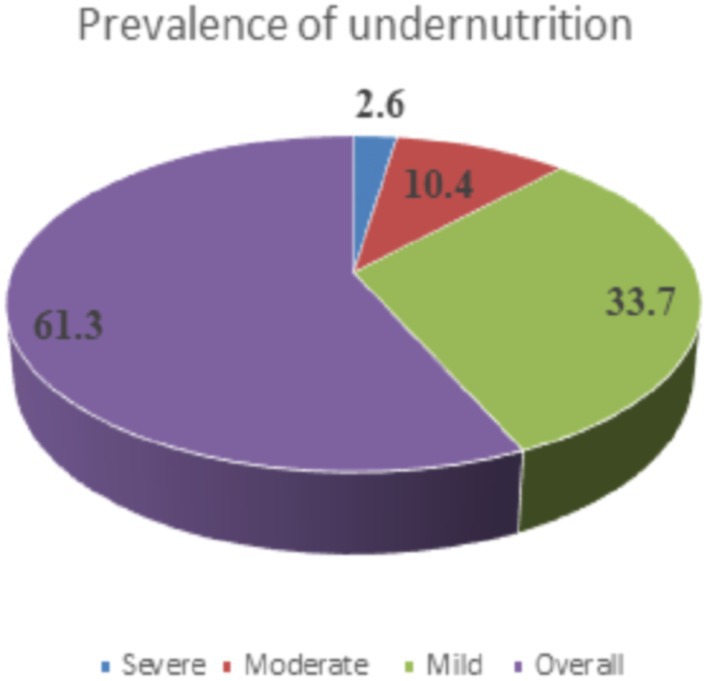

Based on anthropometric measurement, the prevalence of undernutrition among the adolescents was found to be 61.3% (95% CI: 58.1, 64.6) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Prevalence of undernutrition among male adolescents attending traditional schools in northwest Ethiopia, 2021.

Although the data were ordinal in nature, the proportional odds assumption was not found to be reasonable (p ≤ 0.001). Consequently, a binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the association of various factors with undernutrition. Variables with a p-value < 0.25 in the binary logistic regression analysis were entered into a multivariate logistic regression and associated factors were thus identified.

Compared to students of the kidase level, the odds of undernutrition among dikuna, kinne, aquaquame, and tirguame students were 4.3 (AOR = 4.3, 95% CI = 1.3, 13.6), 4.5 (AOR = 4.5, 95% CI = 1.4, 14.6), 10 (AOR = 9.9, 95% CI = 2.5, 39.88), and 6.4 (AOR = 6.4, 95% CI = 1.6, 25.6) times higher, respectively.

The odds of undernutrition were higher among those adolescents who were not able to read and write than among those who were (AOR = 3.7, 95% CI = 1.13, 12.8).

The odds of undernutrition were 0.7 times lower among those adolescents who practiced handwashing before and after eating (AOR = 0.7, 95% CI = 0.50, 0.98). Those adolescents who reported washing their hands after visiting the toilet were 0.7 times less likely to meet the criteria for undernutrition (AOR = 0.7, 95% CI = 0.47, 0.96) as compared to their counterparts (Table 3).

Table 3. Results of a multivariate logistic regression assessing factors associated with undernutrition among adolescents at traditional schools in Gondar, Ethiopia, 2021.

In terms of the prevalence of undernutrition, the findings of this study revealed that more than three out of five adolescent students at traditional schools are undernourished. This implies that a large number of Ethiopian Orthodox Church students are undernourished.

Specifically, the findings revealed that the prevalence of undernutrition in Gondar is 61.3%. This figure is higher than the findings of other studies, which have reported a prevalence of 26.4% in southern Ethiopia (28) and 14.4% in Gondar (9). A possible reason for this difference might be the differences in study population, period, and sample size. The current study was conducted among male adolescents who were attending traditional schools, whereas all the aforementioned previous studies were conducted among adolescent girls. Additionally, almost all of these previous studies were conducted 5 years ago. The higher prevalence of undernutrition in this study also might be accounted for by the fact that most of these traditional school attendees were practicing fasting for approximately 200 days per year (practice that involves abstaining from all types of foods for a large portion of the day) and that these students ate by begging for their daily food from the community (29, 30). Therefore, nutritional programs and interventions must include these traditional schools in Ethiopia. Additionally, it might be very important to enhance nutritional awareness among Ethiopian Orthodox church leaders.

Those adolescent attendees of traditional schools who were following the levels of aquaquame, Turguame, dikuna, and kinne had higher odds of undernutrition than students who were following the level of kidase. This might be because those who are following kidase are most likely to be provided with the opportunity to eat after each of the ceremonial activities of kidase (29). An additional possibility might be that all the former level of educations are finally leading to employment for kidase students after their graduation. This implies that the establishment of boarding with the provision of a diversified diet by the churches could be an important intervention.

With regard to the mother’s educational status, the findings of this study revealed that the odds of undernutrition were higher among adolescents whose mothers were unable to read and write than among those adolescents whose mothers had received some education. This might be because education enables mothers to understand the effects of undernutrition (31). Therefore, extensive education on nutritional concepts for mothers might be a very important intervention to overcome the problem of undernutrition in these traditional schools.

Finally, the likelihood of undernutrition was higher among male adolescents who did not wash their hands before and after eating. Similarly, those who did not wash their hands after visiting the toilet had higher odds of undernutrition. This finding is similar to those of other studies conducted in Ethiopia (31, 32) and Iraq (33). Therefore, personal hygiene and sanitation measures, such as washing the hands with soap after each toilet visit and before eating food, are recommended for the students.

The study had a large sample size and specifically targeted individuals attending traditional schools. On the other hand, because of the cross-sectional nature of the data, it is difficult to generalize the findings to the entire population and to identify the relationships between cause and effect.

The finding of this study showed that the prevalence of undernutrition among traditional Orthodox Church students is high. Students at the levels of aquaquame, Turguame, dikuna, and kinne were at high risk of undernutrition. Moreover, not washing one’s hands before and after eating and after visiting the toilet was significantly associated with undernutrition among male adolescents. Therefore, to improve the nutritional status of the students, the establishment of well-resourced traditional religious schools, equipped for the provision of an adequate diversified diet, is important; additionally, parents should develop the habit of serving a good diversity of foods to their adolescents. Furthermore, encouraging students to wash their hands before and after eating as well as after visiting the toilet is very important. Finally, we recommend that further research should be conducted targeting these students at traditional schools across a wide area, taking both qualitative and quantitative approaches.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional review board of University of Gondar. Additionally, Institution of Ethiopian Orthodox Church (ETOC) North Gondar Sinod Branch formal letter of cooperation was written for Gondar city intuition of church and respective churches were also obtained. Informed consent was obtained from each study subject. Respondents were also obtained about the objective of study which contributed necessary information for policy makers and other concerned bodies. Brief explanation about the purpose of the study was given to each concerned bodies. The voluntary nature of the study was explained for the study participants. Any involvement in the study was done after their complete consent was obtained. They were also informed that all data obtained from them would be kept confidential by using codes instead of any personal identifiers. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

YS and WN conceived and designed the research and performed the analysis. DA, ME, HB, and DB were involved in supervision and reviewed the manuscript. YS, DA, ME, DB, HB, and WN revised the manuscript, and WN subsequently revised the final draft of the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The University of Gondar sponsored this study. However, it played no role in the decision-making relating to manuscript preparation or publication.

The authors acknowledge the University of Gondar. The authors are also grateful to the data collectors, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and the study participants.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AOR, Adjusted odds ratio; BMI, Body mass index; COR, Crude odds ratio; ETOC, Ethiopian Orthodox Church; MUAC, Mid-upper arm circumference; OR, Odds ratio; SPSS, Statistical package for the social sciences.

2. Blum, RW . Global trends in adolescent health. J Am Med Assoc. (1991) 265:2711–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03460200091042

3. Nutrition, WA . A review of the situation in selected southeast Asian countries. New Delhi: Regional Office for South-East Asia (2006). 84 p.

4. Nations, U . Department of Economic and Social Affairs, population division, world population prospects. The 2008 Revision. (2010)

5. WHO . Improvement of nutritional status of adolescents. Report of the Regional Meeting Chandigarh. (2002) 84:7.

6. WHO . Nutrition in adolescent issues and challenges for the health sectors. Issues in Adolescent Health and Development. (2005):3.

7. Deshmukh, P, Gupta, SS, Bharambe, MS, Dongre, AR, Maliye, C, Kaur, S, et al. Nutritional status of adolescents in rural Wardha Indian. J Pediatr. (2006) 73:39–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02820204

8. Menezes, IC, Neutzling, MB, and Taddei, JD. Risk factors for overweight and obesity in adolescents of a Brazilian University: a case-control study. Nutr Hosp (2009). 24:17–24.

9. Dadi, AF, and Desyibelew, HD. Undernutrition and its associated factors among pregnant mothers in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0215305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215305

10. Diddana, TZ . Factors associated with dietary practice and nutritional status of pregnant women in Dessie town, northeastern Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2019) 19:517. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2649-0

11. Daba, DB, Shaweno, T, Taye Belete, K, and Workicho, A. Magnitude of under nutrition and associated factors among adolescent street children at Jimma town, south West Ethiopia. Nutr Diet Suppl. (2020) 12:31–9. doi: 10.2147/NDS.S233393

12. Gagebo, DD, Kerbo, AA, and Thangavel, T. Undernutrition and associated factors among adolescent girls in Damot Sore District, southern Ethiopia. J Nutr Metab. (2020) 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2020/5083140

13. Berhe, K, Kidanemariam, A, Gebremariam, G, and Gebremariam, A. Prevalence and associated factors of adolescent undernutrition in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nutr. (2019) 5:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40795-019-0309-4

14. Negash, WD, Fetene, SM, Shewarega, ES, Fentie, EA, Asmamaw, DB, Teklu, RE, et al. Multilevel analysis of undernutrition and associated factors among adolescent girls and young women in Ethiopia. BMC Nutr. (2022) 8:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40795-022-00603-x

15. Joshi, HS, Gupta, R, Joshi, MC, and Mahajan, V. Determinants of nutritional status of school children – a cross sectional study in the wetern region of Nepal. NJIRM. (2011) 2:975–9840s.

16. Tolera, GDW, and Gemede, HF. Prevalence of wasting and associated factors among preschool children in Gobu Sayo Woreda, east Wollega, Ethiopia. Food Sci Qual Manag. (2014) 28:58–9.

17. Roba, K, Abdo, M, and Wakayo, T. Nutritional status and its associated factors among school adolescent girls in Adama City, Central Ethiopia. J Nutr Food Sci. (2016) 6:2.

18. Chaillot, C . Traditional teaching in the ethiopian orthodox church: yesterday, today and tomorrow. Traditional Teaching in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. (2009):530–532s.

19. Nasser, M . Eating disorders: the cultural dimension. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (1988) 23:184–7.

20. Wallace, JM, and Forman, TA. Religion's role in promoting health and reducing risk among American youth. Health Educ Behav. (1998) 25:721–41. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500604

21. Belwal, R, and Tafesse, Y. A study of the impact of orthodox Christians fasting on demand for biscuits in Ethiopia. Afr J Mark Managess. (2010) 2:010–7.

22. Tamrat, A, Yeshaw, Y, and Dadi, AF. Stunting and its associated factors among early adolescent school girls of Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia: A School-Based Cross-Sectional Study. BioMed Res Int. (2020) 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2020/8850074

23. Tamrat, A., Yeshaw, Y., and Fekadu, A., Stunting and its determinant factors among early adolescent school girls of Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia: A school based cross-sectional study. (2019).

24. Ali, MS, Kassahun, CW, and Wubneh, CA. Overnutrition and associated factors: a comparative cross-sectional study between government and private primary school students in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia. J Nutr Metab. (2020) 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2020/3670895

25. Gebregyorgis, T, Tadesse, T, and Atenafu, A. Prevalence of thinness and stunting and associated factors among adolescent school girls in Adwa town, North Ethiopia. Int J Food Sci. (2016) 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2016/8323982

26. Ancel, S, and Ficquet, É. The Ethiopian orthodox Tewahedo church (EOTC) and the challenges of modernity In: Understanding contemporary Ethiopia: Monarchy, revolution and the legacy of Meles Zenawi (2015). 63–92.

27. Moareta, M. Contribution and challenges of Ethiopian orthodox Tewahido church for sustainable tourism development: the case of gondar city. (2015).

28. Yimer, B, and Wolde, A. Prevalence and predictors of malnutrition during adolescent pregnancy in southern Ethiopia: a community-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2022) 22:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-04460-1

29. Desalegn, BB, Lambert, C, Riedel, S, Negese, T, and Biesalski, HK. Ethiopian orthodox fasting and lactating mothers: longitudinal study on dietary pattern and nutritional status in rural Tigray, Ethiopia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:1767. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15081767

30. Desalegn, BB, Lambert, C, Riedel, S, Negese, T, and Biesalski, HK. Feeding practices and undernutrition in 6–23-month-old children of orthodox Christian mothers in rural Tigray, Ethiopia: longitudinal study. Nutrients. (2019) 11:138. doi: 10.3390/nu11010138

31. Muche, A, Melaku, MS, Amsalu, ET, and Adane, M. Using geographically weighted regression analysis to cluster under-nutrition and its predictors among under-five children in Ethiopia: evidence from demographic and health survey. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0248156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248156

32. Mutua, F.K., Mutie, I, Kuboka, M, Leahy, E, and Grace, D. Literature review on foodborne disease hazards in food and beverages in Ethiopia. (2022).

Keywords: undernutrition, Ethiopia, adolescent males, orthodox, Gondar

Citation: Shiferaw YF, Asmamaw DB, Engidaw MT, Belay DG, Birhan H and Negash WD (2023) The prevalence of undernutrition among students attending traditional Ethiopian orthodox Tewahedo church schools in northwest Ethiopia. Front. Public Health. 11:1124173. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1124173

Received: 19 December 2022; Accepted: 07 June 2023;

Published: 03 July 2023.

Edited by:

Edyta Łuszczki, University of Rzeszow, PolandReviewed by:

Beruk Berhanu Desalegn, Hawassa University, EthiopiaCopyright © 2023 Shiferaw, Asmamaw, Engidaw, Belay, Birhan and Negash. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wubshet Debebe Negash, d3Vic2hldGRuQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.