1. Falls as a focal issue for older adults

The global aging population is larger than ever before (1), and it is estimated that 155 countries will have an aging society by the year 2050 (2). In the United States alone, there are more than 50 million adults ages 65 years and older, with this sub-population projected to exceed more than 80 million by 2040 (3). The growing aging population reflects longer life expectancies largely attributed to a combination of medical advancements, accessible healthcare, and supportive and inclusive physical and social environments (4). While there is much variability in the aging process (5), the expansive older adult population brings with it increased prevalence rates of chronic conditions and other health issues (e.g., injurious falls, cognitive decline, malnutrition, mental illness, and social disconnectedness) that will further strain the already over-burdened healthcare system. While there are many pressing and costly geriatric conditions deserving of increased and immediate attention, we will focus on older adult falls as an example of a globally-recognized, age-related condition with a host of negative, but potentially preventable, sequelae (6, 7). Too often falls are narrowly viewed as a natural and inevitable part of aging, which cannot be prevented or managed. The complex and multi-factorial circumstances resulting in a fall require a more holistic view of the event (i.e., causes, facilitators, and contributors) and the older adults' physical, mental, environmental, and medical context. We contend that falls is among the most germane health issues facing older adults because a fall can represent a constellation of interwoven health events and may be centric to multi-level solutions spanning research, healthcare practice, community programming, and policy. This article aims to expand the lens through which we view falls as a public health issue by: (a) offering insights about the upstream indicators and downstream ramifications associated with falls; and (b) highlighting opportunities for interdisciplinary and cross-sectorial solutions to predict, prevent, and manage falls among older adults.

Falls in the United States are the leading cause of unintentional injuries among older adults age 65 years and older (8). The incidence of falls is substantial, with one-in-four older adults falling each year (9). Older adults who fall have an increased risk for injury, reduced physical function, loss of independence, institutionalization, and death (9, 10). The estimated annual direct medical costs of falls exceed $50 billion USD (11), which does not account for the associated costs for rehabilitation, caregiving, skilled nursing, or other resulting health issues (physical or mental). The ramifications of a fall dramatically impact the older adult, but when considered collectively, these negative consequences impose extreme duress on their families, social structures, and the clinical and community-based organizations that serve them. Although the likelihood of falling increases with age, it is not a natural part of aging. Falls are not inevitable; rather, they are largely preventable. The causes of falls are vast, individualistic, situational, and often interrelated. They include intrinsic and extrinsic factors, which are biological, behavioral, and environmental (12).

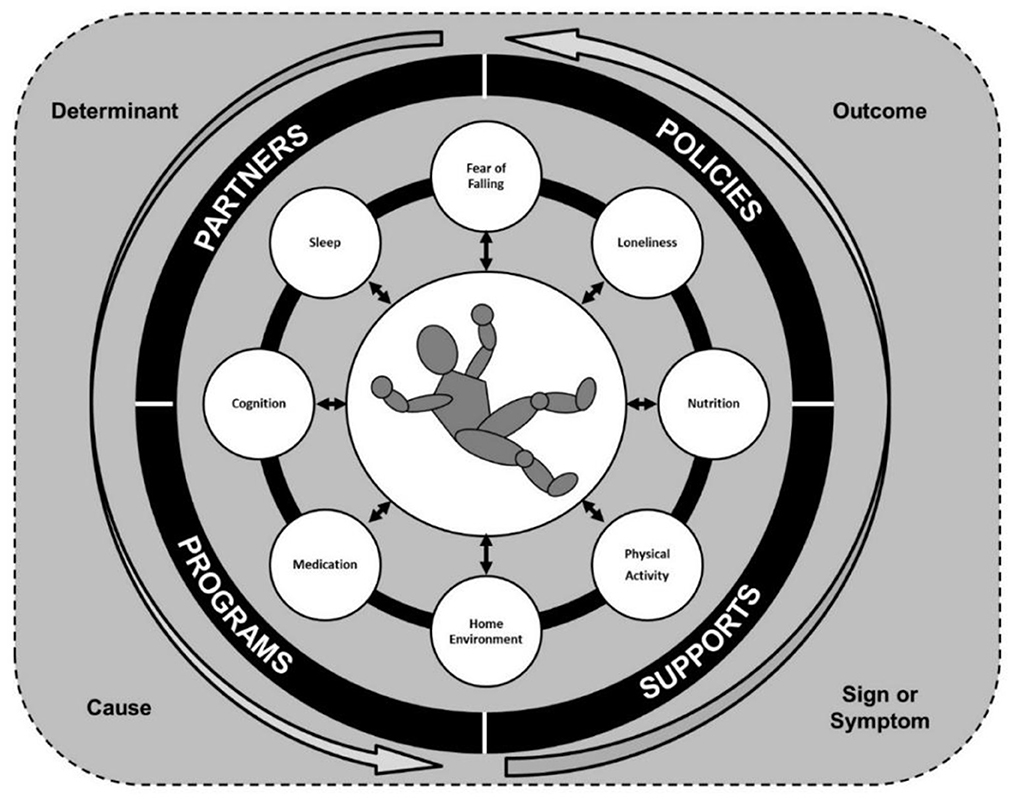

Given the common, complex, and severe nature of falls among older adults, we need to challenge the way we think about falls (13, 14). As researchers, clinicians, and community service providers, we should view falls as a multi-directional occurrence and recognize that the fall itself may not be the focal issue. As depicted in Figure 1, falls can be expressed in multiple ways and take on many roles within the lives of older adults. A fall can be an outcome that is the result of a set of personal or environmental circumstances, a sign or symptom of an underlying health issue, and/or a cause of or trigger for subsequent health consequences. As such, when an older adult presents with a fall, we must holistically assess the person and event to determine the role of the fall within the situational context. There is a need to screen the older adult, perform physical and cognitive assessments, and ask questions of the family and loved ones to understand the situational context and address the upstream and downstream correlates of the fall.

2. Select examples of multi-directional fall-related risk

In many instances, a contributing reason for a fall (risk factor) is also affected after a fall. This creates a scenario where the same risk factor can contribute to a fall, emerge after a fall occurs, or intensify after a fall when present prior to a fall. As such, there are opportunities to address these factors both before and after a fall, yet the strategies and interventions may be consistent or uniquely tailored based on the context of fall and other existing risks/complications. To illustrate this point, we provide six selective examples below to describe the multi-directionality of these risk factors as related to fall prevention (before) and management (after). However, it must be recognized that after a fall occurs, both management and prevention efforts are needed because part of managing a fall is preventing a repeated or subsequent fall.

Fear of falling is a known risk factor for falling because the fear itself causes older adults to avoid performing certain actions, movements, and activities (15). This fear, in turn, often results in muscular atrophy and reduced lower limb strength/balance/flexibility, which can contribute to the older adult being unsteady on their feet when they are mobile and attempt to perform certain activities. While fear of falling can contribute to a fall, the fear of falling can emerge or escalate after an older adult experiences a fall (16), especially in instances where an injury occurred. Many fall prevention interventions now include attention to strategies to acknowledge and reduce fear of falling.

Physical activity is a protective factor against falls in that it promotes circulatory health and lower extremity strength, balance, and flexibility (17). A variety of physical activities and exercises are recommended to promote postural stability and fall prevention, which should be performed consistently over time and become progressively more challenging for the older adult over time (depending on their functional mobility and ability levels). While physical activity is largely protective, in some instances, it can introduce opportunities for falling among older adults based on internal, situational, and environmental factors. After a fall, there is an increased likelihood of physical inactivity or sedentary behavior, especially if the fall resulted in a fracture (e.g., hip, pelvis, and femur) or traumatic brain injury. As such, it is essential to promote physical activity at all ages but allow an older adult ample time to rest and recuperate after a fall before introducing rehabilitation activities (i.e., to regain physical mobility and avoid lower extremity atrophy).

Medication, and especially polypharmacy, is a risk factor for falling because the side effects may influence blood pressure and other biological functions that can cause dizziness and postural hypotension (18). When an older adult takes multiple medications simultaneously, the opportunities for negative interaction effects amplify, as can the associated side effects, that can cause decreased consciousness (e.g., blackouts and fainting) or general postural unsteadiness. After a fall occurs, especially a fall with injury, the activities and lifestyle behaviors of a person may change during recovery. They may be prescribed prescription pain relievers, which may create interaction effect issues with existing medication regimens and medication non-adherence issues (e.g., dose, timing, and food accompaniment). Further, the biological processing of the medication may change after a fall because of resulting changes in mobility, diet (appetite suppression from prescription pain relievers), and sleep patterns. Increasing recognition of these medication-related risks have prompted doctors and pharmacists to perform routine checks of medication usage, and cross-reference for potential interaction effects, during each medical encounter.

Nutrition, and especially malnutrition, is an important and often unrecognized risk factor for falls and lower limb functioning (19–22). Protein-rich diets among older adults, which impact muscle mass and strength, may prevent the occurrence of a fall as well as accelerate the recovery time after an injurious fall (23, 24). Proper and balanced diets can provide the bones and muscles sufficient strength and functioning needed to accommodate to changing functional capacities with aging. Beyond access to healthful and affordable foods, older adults may benefit from nutritional supplements to bolster daily protein consumption and muscular function.

Loneliness, and overall social disconnectedness, is a risk factor for falls because older adults feeling isolated from others may be socially excluded or have limited support networks, thus hindering their social activities and exacerbating other risk factors associated with falls (e.g., depression, cognitive impairment, sedentary behavior, and substance use) (25). After a fall, older adults may become homebound or have limited community-based mobility, which can hinder their ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living and limit meaningful interactions with others, which can cause feelings of loneliness, isolation, and disconnectedness. This situation can be especially impact older adults without robust social networks to meet their needs and keep them socially engaged (e.g., those residing alone).

Home and Community Environments are seen as a major extrinsic risk factors for falls both within the home and in the community (26, 27). Environmental factors can be associated with common trips and slips among older adults with declining physical capacities to compensate for environmental hazards, while environmental modifications can reduce fall-related risk by introducing handrails, grab bars, and ample lighting within homes and areas frequented by older adults (28). Similarly, to reduce falls risk, there is greater appreciation of the importance of having safe, navigable outdoor environments with amenities such as crosswalks/pedestrian signals, seating for rest, and lighting/shade in recreational areas and places where older adults engage in utilitarian activities (29, 30). After a fall, older adults may be unable to drive or travel freely within their community (e.g., due to injury, immobility, or pain medication), which may limit their ability to run errands or go to doctor's appointments necessary for rehabilitation. Further, they may be unable to clean or pick-up clutter around the home, which may create or contribute to in-home fall-related hazards.

3. Solutions to advance fall prevention and management

Like many geriatric health issues, fall-related risks are multi-factorial and therefore require multi-factorial solutions and a diverse, multi-disciplinary team/workforce to: (a) reduce incidence and prevalence rates; and (b) help older adults overcome the fall after it occurs. While the fall itself is a focal point for intervention, it is often indicative of other issues occurring within the older adult's life, which highlights our need to recognize and address the complexities of upstream indicators and downstream ramifications. Therefore, we must be simultaneously reactive and proactive to address falls and fall-related risk comprehensively within our communities.

Multi-level approaches are needed to adequately and comprehensively prevent and manage falls among older adults. At the individual level, efforts are needed to routinely assess fall-related risk among older adults independently from, and within the context of, other known risk factors. As an example, in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed a comprehensive toolkit, STopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries (STEADI) to help healthcare professionals screen and assess for fall-related risk and make tailored referrals to specialists and community-based programs (31). While fall screening is useful in the falls context, additional efforts are needed to uniformly assess other associated risk factors such as malnutrition, sedentary behavior, loneliness, physical and cognitive functioning, and sleep problems. Such risk inventories interpreted in a falls context, and reviewed with multi-disciplinary teams in healthcare and community settings can elevate fall prevention efforts and assist to mitigate fall-related ramifications, if a fall occurs. The amassing body of intervention research confirms that the most successful fall prevention programs are those that are multifactorial and multicomponent (32). As such, within the United States' aging services network, there are many evidence-based fall prevention programs disseminated at the national, state, and local levels (33). These interventions are critical to address intrinsic and extrinsic fall-related risks to prevent and manage older adult falls. However, to reach a sufficient number of older adults with effective programming, a diverse delivery infrastructure is needed that includes healthcare, community non-profit, residential, faith-based, government, education, and industry partners (34, 35). Then, after establishing infrastructure, dedicated efforts and funding are needed for program scalability and sustainability (36). At the community level, the creation of national- and state-based coalitions (or task forces, action alliances, etc.) to address falls and other issues facing older adults have great potential to unify efforts and embed evidence-based solutions and best practices across communities over time and geography (37–39). Further, the United States has an active age-friendly communities movement, which encourages attention to environmental and policy issues to support livable and connected communities that facilitate increased physical activity, access to resources, and social interactions (i.e., thereby ameliorating important fall risks) (40, 41).

The Otago Exercise Program (OEP) is an example of an effective fall prevention program that fits within a multi-level fall prevention framework and fosters multi-sectorial collaboration and action (13, 42). Adopted in the United States from New Zealand (43, 44), OEP is an innovative model of in-home, one-on-one physical therapy sessions targeting frailer older adults. These home-bound older adults are the primary audience for this program because they are typically older, have more comorbidities, face more environmental and social challenges, and are at greater risk for recurring falls. Based on the older adult's risk and ability levels, the physical therapist engages participants in 17 strength and balance exercises over a series of six visits. The intensity of exercises is progressively increased to improve older adults' lower-limb strength, balance, and flexibility. OEP is complemented by a weekly walking program to assist participants be more active between physical therapy visits and encourage mobility outside the home (45). Older adults are often referred to OEP by healthcare providers following a clinical risk assessment (e.g., STEADI) or being discharged after a fall (46). After participating in OEP, participants are often referred to other evidence-based fall prevention programs in community settings (e.g., A Matter of Balance, Stepping On, Tai Chi: Moving for Better Balance) so they can continue to mitigate fall-related risk and become more physically active. OEP has been shown to significantly improve participants' functional performance (i.e., Timed Up-and-Go, 30-Second Chair Stand, Four-Stage Balance Test) (47, 48). Based on these outcomes, OEP was translated so it could reach more older adults and be implemented in more clinical and community settings. As a result, OEP has been translated for delivery in group and community settings, facilitation by non-physical therapists (e.g., certified occupational therapy assistants, lay leaders of evidence-based programs) (48, 49), and virtual dissemination using an avatar-guided platform (50). These translated OEP versions have also demonstrated effectiveness, respectively. The delivery and evolution of OEP illustrate the importance of cross-sectoral screening, referral, and intervention to identify frail home-bound older adults needing assistance and assist them prevent and overcome falls.

Offering multi-level, multi-sectoral solutions in the United States is consistent with the global initiatives promulgated by the United Nations' Decade of Healthy Aging (2021–2030), which gives concrete actions for making healthy aging a global reality (51). Because falls are a central and complex health issue impacting the older population, coordinated multi-level research, practice, and policy efforts are needed to understand the many roles of falls, its drivers, and its consequences. Considering a fall can be an outcome, sign or symptom, or cause or trigger, it is necessary that we examine the context of each fall among older adults to gain a holistic view of their health risks and conditions. As a society, at all levels, we must proactively screen, assess, refer, intervene, treat, and follow-up with our older adults to prevent falls and protect older adults from related (and potentially preventable) sequelae. In the coming decade, we must view and prioritize falls as a pressing health issue within the aging population and collectively advocate for multi-level solutions spanning research, healthcare practice, community programming, and policy.

4. Conclusions

The situations and circumstances surrounding a fall are complex and should be viewed as a multi-directional occurrence. Researchers, practitioners, and policy makers must challenge the way they think about falls and recognize that the fall itself may not be the focal issue. Collectively, we must assess the upstream indicators and downstream ramifications of falls and identify practical and effective solutions to address these factors both before and after a fall. While we have implemented strategies to identify falls in clinical settings and refer at-risk older adults to evidence-based fall prevention programs across community sectors, we must also consider how falls fit within the greater context of other health issues (e.g., malnutrition, physical inactivity, cognitive impairment, social disconnectedness, polypharmacy, and the built environment). Despite our many advancements, additional multi-level, multi-sectorial solutions are needed to prevent and manage falls among the growing and diverse global aging population. Our efforts must span research, healthcare practice, community programming, and policy to ensure solutions are practical, effective, replicable, scalable, and sustainable.

Author contributions

MS conceptualized and wrote the article. MO wrote the article. All authors reviewed and approved the submitted manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. (2022). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health#:~:text=At%20this%20time%20the%20share,2050%20to%20reach%20426%20million (accessed November 1, 2022).

2. United Nations Department Department of Economic Social Affairs Population Division. (2019). World Population Ageing 2019 - Highlights. Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Highlights.pdf (accessed November 1, 2022).

3. Administration for Community Living. Projected Future Growth of Older Population. (2022). Available online at: https://acl.gov/aging-and-disability-in-america/data-and-research/projected-future-growth-older-population (accessed November 1, 2022).

4. McMaughan DJ, Oloruntoba O, Smith ML. Socioeconomic status and access to healthcare: Interrelated drivers for healthy aging. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:231. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00231

5. Ory MG, Smith ML. What if healthy aging is the “new normal”? Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14:1389. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111389

6. Mackenzie L, Tan MP, Silveria Gomes AR, Dennis S, Pit SW, Wales Smith ML. Falls Prevention for Older People in Primary Care Settings. (2022). Available online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/19002/falls-prevention-for-older-people-in-primary-care-settings (accessed November 1, 2022).

7. Frieson CW, Tan MP, Ory MG, Smith ML. Evidence-based practices to reduce falls and fall-related injuries among older adults. Front Public Health. (2018) 6:222. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00222

8. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Injury Prevention and Control. Keep on Your Feet – Preventing Older Adult Falls. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features/older-adult-falls/index.html (accessed November 1, 2022).

9. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Older Adult Fall Prevention. Facts about Falls. (2021). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/falls/facts.html (accessed November 1, 2022).

10. Vaishya R, Vaish A. Falls in older adults are serious. Indian J Orthop. (2020) 54:69–74. doi: 10.1007/s43465-019-00037-x

11. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Older Adult Fall Prevention. Cost of Older Adult Falls. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/falls/data/fall-cost.html (accessed November 1, 2022).

12. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Fact Sheet – Risk Factors for Falls. (2017). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/Risk_Factors_for_Falls-print.pdf (accessed November 1, 2022).

13. Shubert TE, Smith ML, Schneider EC, Wilson AD, Ory MG. Commentary: Public health system perspective on implementation of evidence-based fall-prevention strategies for older adults. Front Public Health. (2016) 4:252. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00252

14. Shubert TE, Smith ML, Prizer LP, Ory MG. Complexities of fall prevention in clinical settings: A commentary. Gerontologist. (2014) 54:550–8. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt079

15. Schoene D, Heller C, Aung YN, Sieber CC, Kemmler W, Freiberger E. a systematic review on the influence of fear of falling on quality of life in older people: Is there a role for falls? Clin Interv Aging. (2019) 14:701. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S197857

16. Lavedán A, Viladrosa M, Jürschik P, Botigué T, Nuín C, Masot O, et al. Fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults: A cause of falls, a consequence, or both? PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0194967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194967

17. van Gameren M, Hoogendijk EO, van Schoor NM, Bossen D, Visser B, Bosmans JE, et al. Physical activity as a risk or protective factor for falls and fall-related fractures in non-frail and frail older adults: A longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. (2022) 22:1. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03383-y

18. Ie K, Chou E, Boyce RD, Albert SM. Fall risk-increasing drugs, polypharmacy, and falls among low-income community-dwelling older adults. Innov Aging. (2021) 5:igab001. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igab001

19. Eckert CD, Tarleton EK, Pellerin J, Mooney N, Gell NM. Nutrition risk is associated with falls risk in an observational study of community-dwelling, rural, older adults. J Aging Health. (2022) 29:8982643221096944. doi: 10.1177/08982643221096944

20. Corish CA, Bardon LA. Malnutrition in older adults: Screening and determinants. Proc Nutr Soc. (2019) 78:372–9. doi: 10.1017/S0029665118002628

21. Esquivel MK. Nutritional assessment and intervention to prevent and treat malnutrition for fall risk reduction in elderly populations. Am J Lifestyle Med. (2018) 12:107–12. doi: 10.1177/1559827617742847

22. Lackoff AS, Hickling D, Collins PF, Stevenson KJ, Nowicki TA, Bell JJ. The association of malnutrition with falls and harm from falls in hospital inpatients: Findings from a 5-year observational study. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29:429–36. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15098

23. Coelho-Júnior HJ, Milano-Teixeira L, Rodrigues B, Bacurau R, Marzetti E, Uchida M. Relative protein intake and physical function in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients. (2018) 10:1330. doi: 10.3390/nu10091330

24. Ten Haaf DS, Nuijten MA, Maessen MF, Horstman AM, Eijsvogels TM, Hopman MT. Effects of protein supplementation on lean body mass, muscle strength, and physical performance in nonfrail community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. (2018) 108:1043–59. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy192

25. Petersen N, König HH, Hajek A. The link between falls, social isolation and loneliness: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2020) 88:104020. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104020

26. Clemson L, Stark S, Pighills AC, Torgerson DJ, Sherrington C, Lamb SE. Environmental interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochr Datab Systemat Rev. (2019) 2019:CD013258. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013258

27. Lee S. Falls associated with indoor and outdoor environmental hazards among community-dwelling older adults between men and women. BMC Geriatr. (2021) 21:1–2. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02499-x

28. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Check for Safety: A Home Prevention Checklist for Older Adults. (2015). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/check_for_safety_brochure-a.pdf (accessed November 1, 2022).

29. Lee C, Lee C, Stewart OT, Carlos HA, Adachi-Mejia A, Berke EM, et al. Neighborhood environments and utilitarian walking among older vs. younger rural adults. Front Public Health. (2021) 2021:532. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.634751

30. Li W, Procter-Gray E, Lipsitz LA, Leveille SG, Hackman H, Biondolillo M, et al. Utilitarian walking, neighborhood environment, and risk of outdoor falls among older adults. Am J Public Health. (2014) 104:e30–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302104

31. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. STEADI – Older Adult Fall Prevention. (2021). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/index.html (accessed November 1, 2022).

32. Hopewell S, Adedire O, Copsey BJ, Boniface GJ, Sherrington C, Clemson L, et al. Multifactorial and multiple component interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochr Datab Systemat Rev. (2018). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012221.pub2

33. Smith ML, Towne SD Jr, Herrera-Venson A, Cameron K, Horel SA, Ory MG, et al. Delivery of fall prevention interventions for at-risk older adults in rural areas: Findings from a national dissemination. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:2798. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122798

34. Smith ML, Ory MG, Ahn S, Belza B, Mingo CA, Towne SD Jr, et al. Reaching diverse participants utilizing a diverse delivery infrastructure: A replication study. Front Public Health. (2015) 3:77. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00077

35. Towne Jr SD, Smith ML, Ahn S, Altpeter M, Belza B, Kulinski KP, et al. National dissemination of multiple evidence-based disease prevention programs: Reach to vulnerable older adults. Front Public Health. (2015) 2:156. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00156

36. Smith ML, Durrett NK, Schneider EC, Byers IN, Shubert TE, Wilson AD, et al. Examination of sustainability indicators for fall prevention strategies in three states. Eval Program Plann. (2018) 68:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2018.02.001

37. Ory MG, Towne Jr SD, Howell D, Quinn C, Eblen KJ, Swierc SM, et al. Commentary: Working toward a multi-program strategy in fall prevention. Front Public Health. (2017) 5:14. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00014

38. Schneider EC, Smith ML, Ory MG, Altpeter M, Beattie L, Scheirer MA, et al. State fall prevention coalitions as systems change agents: An emphasis on policy. Health Promot Practice. (2016) 17:244–53. doi: 10.1177/1524839915610317

39. Smith ML, Chaudhary S, Nieb S, Bayakly R, Graham K, Head E. Commentary: Building the older adult fall prevention movement–Steps and lessons learned. Front Public Health. (2016) 4:277. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00277

40. Lee C, Zhu X, Lane AP, Portegijs E. Healthy aging and the community environment. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:737955. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.737955

41. AARP. AARP Network of Age-Friendly States and Communities. (2022). AARP Livable Communities. Available online at: https://www.aarp.org/livable-communities/network-age-friendly-communities/ (accessed November 1, 2022).

42. Smith ML, Schneider EC, Byers IN, Shubert TE, Wilson AD, Towne Jr SD, et al. Reported systems changes and sustainability perceptions of three state departments of health implementing multi-faceted evidence-based fall prevention efforts. Front Public Health. (2017) 5:120. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00120

43. Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Tilyard MW, Buchner DM. Randomised controlled trial of a general practice programme of home based exercise to prevent falls in elderly women. Br Med J. (1997) 315:1065–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1065

44. Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Buchner DM. Falls prevention over 2 years: A randomized controlled trial in women 80 years and older. Age Ageing. (1999) 28:513–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.6.513

45. Shubert TE, Smith ML, Ory MG, Clarke CB, Bomberger SA, Roberts E, et al. Translation of the Otago Exercise Program for adoption and implementation in the United States. Front Public Health. (2015) 2:152. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00152

46. Stevens JA, Smith ML, Parker EM, Jiang L, Floyd FD. Implementing a clinically based fall prevention program. Am J Lifestyle Med. (2017) 5:1559827617716085. doi: 10.1177/1559827617716085

47. Shubert TE, Smith ML, Jiang L, Ory MG. Disseminating the Otago Exercise Program in the United States: Perceived and actual physical performance improvements from participants. J Appl Gerontol. (2018) 37:79–98. doi: 10.1177/0733464816675422

48. Shubert TE, Smith ML, Goto L, Jiang L, Ory MG. Otago exercise program in the United States: Comparison of 2 implementation models. Phys Ther. (2017) 97:187–97. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20160236

49. Shubert TE, Goto LS, Smith ML, Jiang L, Rudman H, Ory MG. The otago exercise program: Innovative delivery models to maximize sustained outcomes for high risk, homebound older adults. Front Public Health. (2017) 5:54. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00054

50. Shubert TE, Chokshi A, Mendes VM, Grier S, Buchanan H, Basnett J, et al. Stand Tall—A virtual translation of the Otago Exercise Program. J Geriatr Phys Ther. (2020) 43:120–7. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0000000000000203

51. World Health Organization. UN Decade of Healthy Ageing. (2022). Available online at: https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing (accessed November 1, 2022).

Keywords: falls, fall prevention and management, older adults, intervention, evidence-based practice, multi-level intervention

Citation: Smith ML and Ory MG (2023) Multi-directional nature of falls among older adults: A rationale for prevention and management. Front. Public Health 11:1117863. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1117863

Received: 07 December 2022; Accepted: 31 January 2023;

Published: 21 February 2023.

Edited by:

Paolo Vineis, Imperial College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Stefano Orlando, University of Rome Tor Vergata, ItalyCopyright © 2023 Smith and Ory. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthew Lee Smith,  bWF0dGhldy5zbWl0aEB0YW11LmVkdQ==

bWF0dGhldy5zbWl0aEB0YW11LmVkdQ==

Matthew Lee Smith

Matthew Lee Smith Marcia G. Ory

Marcia G. Ory