- 1The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, Guizhou, China

- 2Zhuhai Center for Maternal and Child Health Care, Zhuhai Women and Children's Hospital, Zhuhai, China

- 3School of Medicine, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

- 4Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

- 5School of Stomatology, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

- 6School of Nursing, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

Background: The prevalence of mental distress is common for medical students in China due to factors such as the long duration of schooling, stressful doctor-patient relationship, numerous patient population, and limited medical resources. However, previous studies have failed to provide a comprehensive prevalence of these mental disorders in this population. This meta-analysis aimed to estimate the prevalence of common mental disorders (CMDs), including depression, anxiety, and suicidal behaviors, among medical students in China.

Methods: We conducted a systematic search for empirical studies on the prevalence of depression, anxiety, suicide attempt, suicide ideation, and suicide plan in Chinese medical students published from January 2000 to December 2020. All data were collected pre-COVID-19. The prevalence and heterogeneity estimations were computed by using a random-effects model and univariate meta-regression analyses.

Results: A total of 197 studies conducted in 23 provinces in China were included in the final meta-analysis. The prevalence data of depression, anxiety, suicide attempt, suicide ideation, and suicide plan were extracted from 129, 80, 21, 53, and 14 studies, respectively. The overall pooled crude prevalence for depression was 29% [38,309/132,343; 95% confidence interval (CI): 26%−32%]; anxiety, 18% (19,479/105,397; 95% CI: 15%−20%); suicide ideation, 13% (15,546/119,069; 95% CI: 11%−15%); suicide attempt, 3% (1,730/69,786; 95% CI: 1%−4%); and suicide plan, 4% (1,188/27,025; 95% CI: 3%−6%).

Conclusion: This meta-analysis demonstrated the high prevalence of CMDs among Chinese medical students. Further research is needed to identify targeted strategies to improve the mental health of this population.

Introduction

Worldwide, medical schools aim to train and produce competent medical doctors to meet healthcare needs and promote public health. This is achieved through arduous training that requires high motivation, intelligence, and endurance. Globally, medical students usually experience high-pressure situations during school, such as the long duration of training (1), the heavy workload of intern clinical practice (2), sleep deprivation (3), financial concerns (4), intensive exams, and career uncertainty (5). Such pressures could cause negative effects on medical students' wellbeing (6) and academic performance (7) and precipitate mental distresses such as depression, anxiety symptoms, and suicidal behaviors (8, 9). A systematic review and meta-analysis including 167 cross-sectional empirical studies reported a global prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in medical students of 27.2 and 11.1%, respectively, indicating high psychological morbidities in this population (10). Furthermore, a meta-analysis involving 57 studies (n = 25,735) demonstrated a substantial prevalence of poor sleep quality of 52.7% among medical students worldwide (11). Burnout among medical students is common as well. A systematic review of 58 studies reported a wide range of burnout prevalence, varying from 7.0 to 75.2% (12). Even before entering residency, the burden of burnout is substantial, as demonstrated by a meta-analysis encompassing 17,431 medical students, which found that 44.2% of global medical students experienced burnout, regardless of gender (13). Anxiety is another significant concern affecting medical students, with a substantially higher prevalence compared to the general population. Globally, about one in three (33.8%) medical students experience anxiety, with a higher prevalence observed among medical students from the Middle East and Asia (14). Furthermore, as medical students advance to higher levels of training and enter residency, they continue to face a significant risk of experiencing mental distress. A meta-analysis that incorporated data from 31 cross-sectional and 23 longitudinal studies revealed an overall pooled prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms of 28.8% among resident physicians (15). Moreover, another meta-analysis involving 22,778 residents indicated that the prevalence of burnout was 51.0% (16). This further highlighted the enduring vulnerability of resident physicians to mental health challenges.

Undetected or untreated mental distress can have persistent and worsening effects, particularly for medical students (17). These effects can manifest in various adverse outcomes, including poor academic performance, a higher dropout rate, limited professional development (18), and impaired quality of life (19). Additionally, there is an increased risk of engaging in unhealthy coping mechanisms such as alcohol and substance abuse, as well as an elevated risk of suicide (20). Furthermore, the presence of chronic psychological distress among medical students can contribute to a decline in empathy and enthusiasm toward patients, resulting in higher rates of medical errors and increased levels of job burnout in future clinical practice (21). This, in turn, can further strain the doctor-patient relationship, diminish treatment quality (22), and ultimately impact the overall culture of the medical profession (20). It highlights the urgency of addressing mental health issues among medical students to prevent these detrimental consequences and ensure the wellbeing of both students and the patients they will serve in their future medical careers.

In China, the medical education system and healthcare environment differ in certain areas compared to Western or other Asian countries. China has great complexity in the levels of programs designed to train doctors. The main current medical education system in China comprises a 3-year junior college medical program, a 5-year medical bachelor's degree program, a “5 + 3” medical master's degree program, and an 8-year medical doctoral degree program (23). Usually, medical students have to go through the “5 + 3” model before gaining the formal job of a medical doctor. One type of “5 + 3” model is finishing 5 years of undergraduate medical education first (leading to a bachelor's degree), then completing 3 years of standardized residency training (SRT). The other type of “5 + 3” model encompasses 5 years of undergraduate education, the postgraduate entrance examination, and 3 years of a professional master's degree (master of medicine, MM) program (including SRT) (24). However, with the increasing demands and expectations of society and the medical system for doctors, more and more medical students choose to achieve a doctoral degree. The long medical schooling cycle that the medical students have to go through is undoubtedly a substantial burden for them. The numerous patient populations and relatively limited medical resources cause overwhelming workload pressures, which could further lead to burnout and low wellbeing (5). Recently, more stressful doctor-patient relationships for Chinese doctors in work settings (25) have been common. This unstable relationship frequently led to workplace violence, and with the patients as perpetrators, healthcare workers experienced greater physical and mental health burdens. These factors are likely to contribute to depression, anxiety symptoms, and suicidal behaviors (e.g., suicidal ideation).

The above findings warrant broader awareness of and greater attention to medical students' mental health in China. Previous meta-analyses have reported the pooled prevalence of mental distress in this population; however, some study limitations exist. For example, a meta-analysis of Chinese medical students published in 2019 and including 21 empirical studies demonstrated a mean prevalence of depression and anxiety of 32.74 and 27.22%, respectively (26). However, this study only investigated psychological morbidities in undergraduate medical students, excluding those at the graduate levels, who might bear a higher burden of mental distress due to higher academic pressure and challenging working environments (27). Another review with 10 primary studies reported the pooled prevalence of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation as 29%, 21%, and 11%, respectively (28). However, the review did not provide a comprehensive analysis of prevalence in this population in China because it failed to search related articles in Chinese databases. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed a 27% comprehensive prevalence of depression in Chinese medical students (29), but reported only the pooled estimate of one mental disease, i.e., depression, which failed to provide an overview of CMDs in this population.

Given this serious public health problem and the limitations of previous reviews, we aimed to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis by conducting a systematic search of English and Chinese databases to (1) systematically assess the comprehensive prevalence of common mental distresses (including depression, anxiety, suicide attempt, suicide ideation, and suicide plan) among medical students in China; (2) conduct subgroup analysis; and (3) explore the sources of heterogeneity among studies.

Materials and methods

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the standards of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement (30) and the Meta-Analyses Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines (31). This study was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42019142527).

Search strategy and study eligibility

An electronic search was conducted to identify original articles published from January 2000 to December 2020 that reported the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and suicidal behaviors (including suicide attempt, suicide ideation, and suicide plan) in Chinese medical students. Databases searched included PubMed, Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and the Chinese databases such as China National Knowledge Infrastructure [CNKI], WANFANG Data, and Weipu (CQVIP) Data. The key terms were “common mental disorders,” “depression,” “anxiety,” “suicide,” and “Chinese medical students.” The detailed search strategy is provided in the Supplementary material. Due to COVID-19, we did not include articles published after January 2021.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included in this meta-analysis if they (1) reported original quantitative studies, including cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control studies; (2) were published in peer-reviewed journals; (3) were written in English or Chinese language; (4) reported on the population comprised of medical students in China (including Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan); and (5) used validated assessment tools with good reliability and validity to evaluate the level of depression, anxiety, and suicidal behaviors among medical students.

Studies were excluded if the (1) prevalence data could not be extracted by indirect calculation or by contacting the corresponding author; (2) publication format was a conference abstract, review, meta-analysis, export opinion, or letter; (3) reported sample size was <30 individuals; (4) the reported participants were not from China; (5) reported population was non-medical students; and (6) reported mental health problems arose under emergency or special circumstances, such as severe acute respiratory syndromes (SARS), Wenchuan earthquakes, and COVID-19.

Selection procedure and data extraction

First, two reviewers (JW and JB) independently identified and screened the articles by title and abstract to determine their eligibility for further examination. Then, the full texts were assessed against eligibility criteria independently by two reviewers (JW and JB), and any disagreement was resolved by a third reviewer (ML or PX; Figure 1). Finally, two reviewers (JW and JB) conducted data extraction from the final included studies. The extracted data included first author, year of publication, study location, sampling method, recall period, measurement tool and cutoff score, study type, sample size, number of medical students with mental problems (including depression, anxiety, and suicide attempt/ideation/plans), and sample characteristics (including age, grade, sex, school type, and major category).

Quality appraisal

The quality appraisal was conducted independently by JW and JB using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Quality Assessment Tool (32). The tool was validated well and was popularly used in previous studies (33, 34). JBI is a renowned and efficient quality tool for assessing the credibility, relevance, and outcomes of prevalence studies. It is composed of 10 items, with each item scored from 0 to 2. A score of 0 represents “not mentioned,” 1 represents “mentioned but not described in detail,” and 2 represents “detailed and comprehensive description.” The higher the total score, the better the quality of the study in terms of credibility, relevance, and outcomes. The detailed scores of each included study are shown in the Supplementary material.

Data synthesis and analysis

The pooled prevalence estimates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal behaviors were calculated by using random-effects models, which were applied when differences in study designs and methodology were assumed to produce variations in effect sizes across individual studies. The Q-statistic was used to evaluate the heterogeneity of effect sizes across studies, and a significant p-value indicated meaningful heterogeneity (35). The I2 statistic, a variance ratio, which described the proportion of heterogeneity observed in the total variability attributed to the heterogeneity between the studies and not to chance, was calculated (36). I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% indicated low, middle, and high levels of heterogeneity, respectively. To further explore the possible sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analysis and univariate meta-regression analysis were performed based on the following characteristics: study region, survey year, sample size, sampling method, recall period of suicidality, measurement tool, and cutoff score. Specifically, the regional classification was based on China's geographic divisions, including North China, East China, South China, Central China, Northeast China, Northwest China, Southwest China, and others (such as multiple regions and not reported). Sensitivity analyses were performed by serially excluding each study to determine the influence of individual studies on the overall prevalence estimates. Egger's test (37) and Begg's test (38) were utilized to investigate publication bias, with p < 0.05 demonstrating statistical publication bias. All statistical analyses were performed using the Stata software (version 14.2; StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States) (39).

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

A total of 197 studies involving 294,408 medical students in China were included in the final meta-analysis (Figure 1). The median sample size was 690 (range: 100–10,344). Among the included studies, 129 reported the prevalence of depression, with a combined sample size of 132,343 individuals. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms was reported in 80 studies, with a combined sample size of 105,397 individuals. The prevalence of suicide attempt, suicide ideation, and suicide plan was reported in 21, 53, and 14 studies, respectively, with combined samples of 69,786, 119,069, and 27,025 individuals.

Of the included studies, 172 were written in Chinese and 26 were written in English. A cross-sectional design was used in 197 studies, and only one study used a randomized controlled trial design. The JBI quality score of the 197 included studies ranged from 6 to 20, with a mean score of 15.

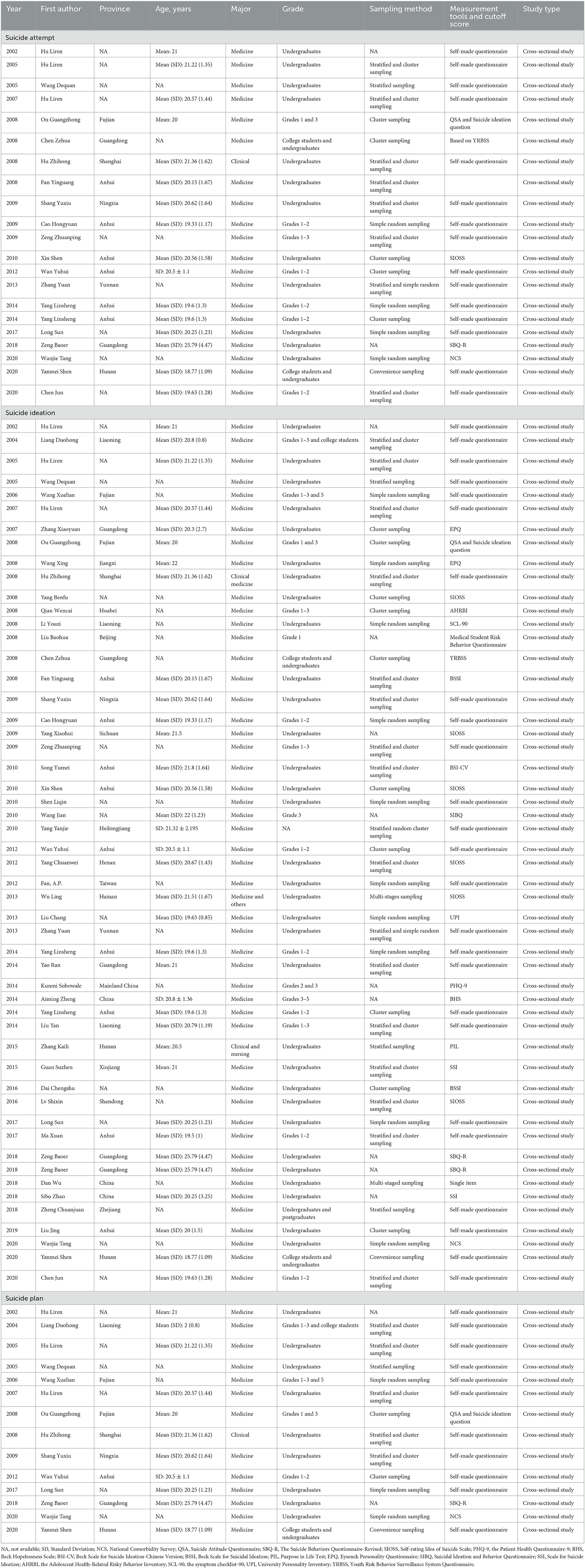

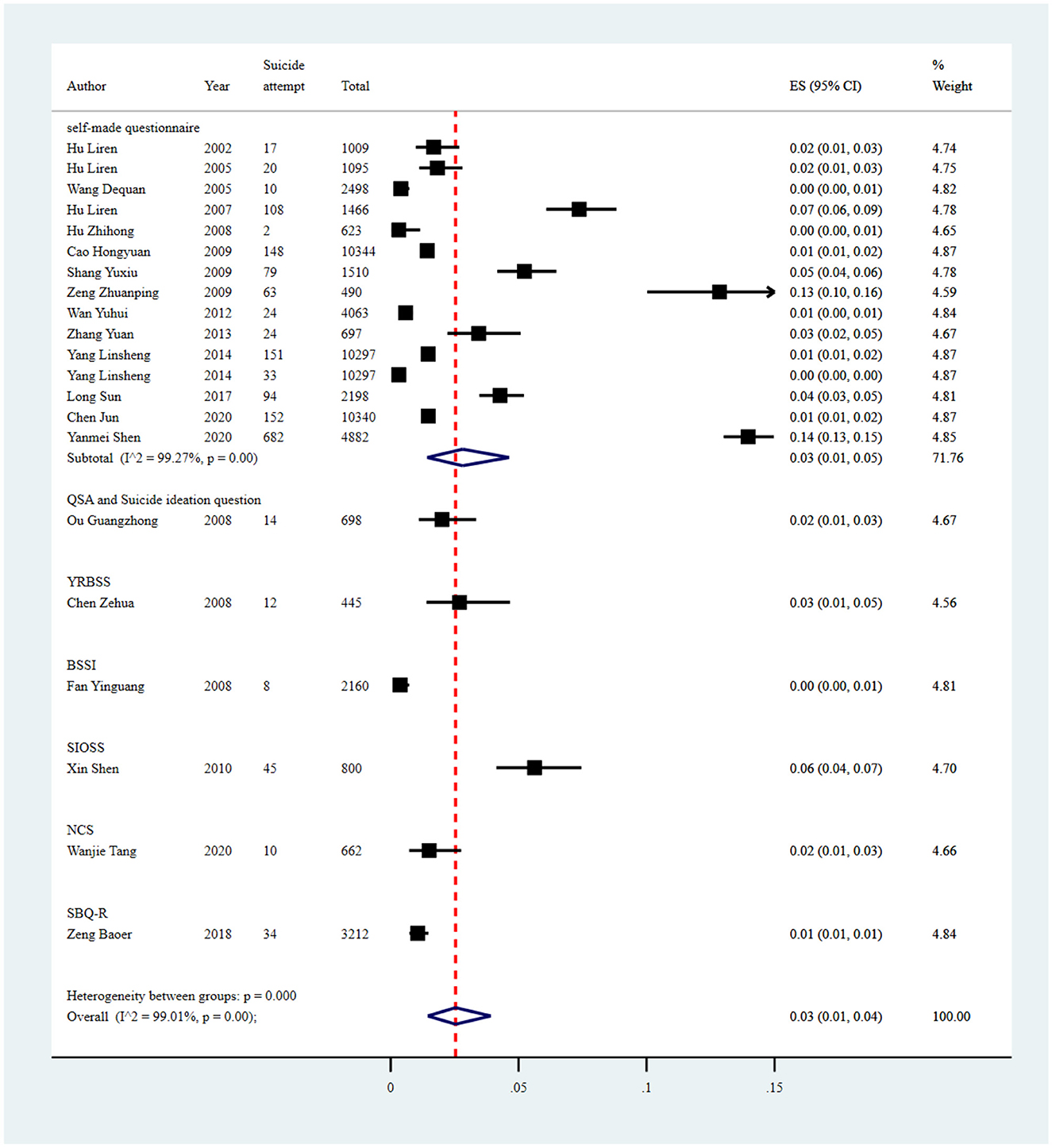

Publication years ranged from 2000 to 2020, and the study regions covered 23 provinces on the mainland and Taiwan Province of China. The most common sampling methods used were multiple sampling methods (n = 58), cluster sampling (n = 55), and simple random sampling (n = 44). Other methods, such as convenience sampling, stratified sampling, and multi-stage sampling, were also used in some of the included studies. With regard to measurement tools or items, 17, 13, and 19 types of tools were used to assess depression, anxiety symptoms, and suicidal behaviors (including suicide attempt, suicide ideation, and suicide plan), respectively. Common measurement tools for depression were Zung's Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), and the Beck Depression Rating Scale (BDI), which were used in 66, 17, and 17 of the included studies, respectively. Anxiety measurement tools were the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), the symptom checklist-90 (SCL-90), and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), used in 52, 10, and 5 of the included studies, respectively. The assessments used for suicidal behaviors were self-made questionnaires or standardized scales, such as the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) and Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire (SBQ). The recall period to measure suicidal behavior included “past 1 week,” “past 6 months,” “past 1 year,” “past 2 years,” and “lifetime.” A detailed summary of the characteristics of the included studies is provided in Tables 1–3.

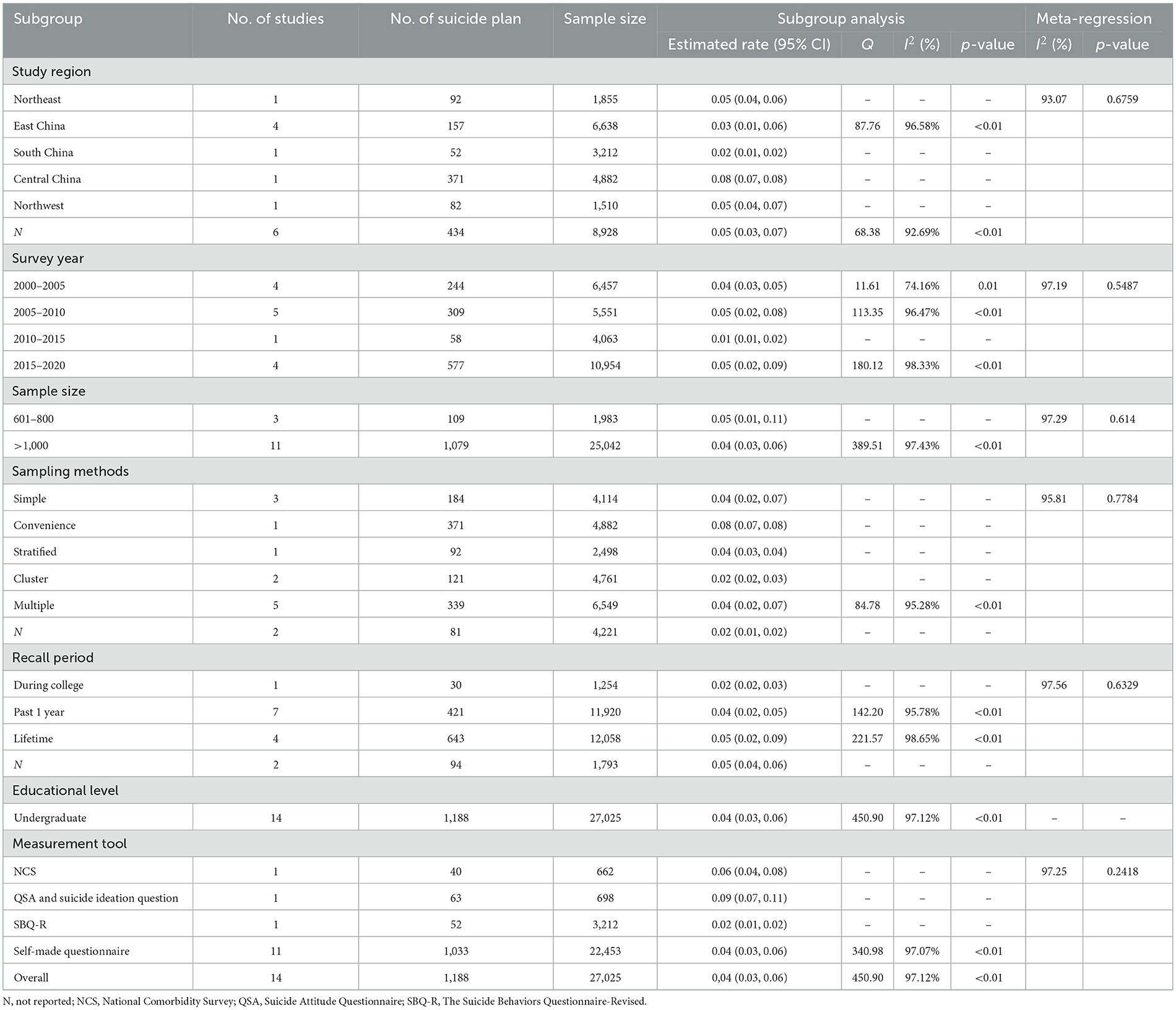

Table 3. Characteristics of the 21, 53, and 14 studies included on suicidal attempt, suicidal ideation, and suicidal plan in this review.

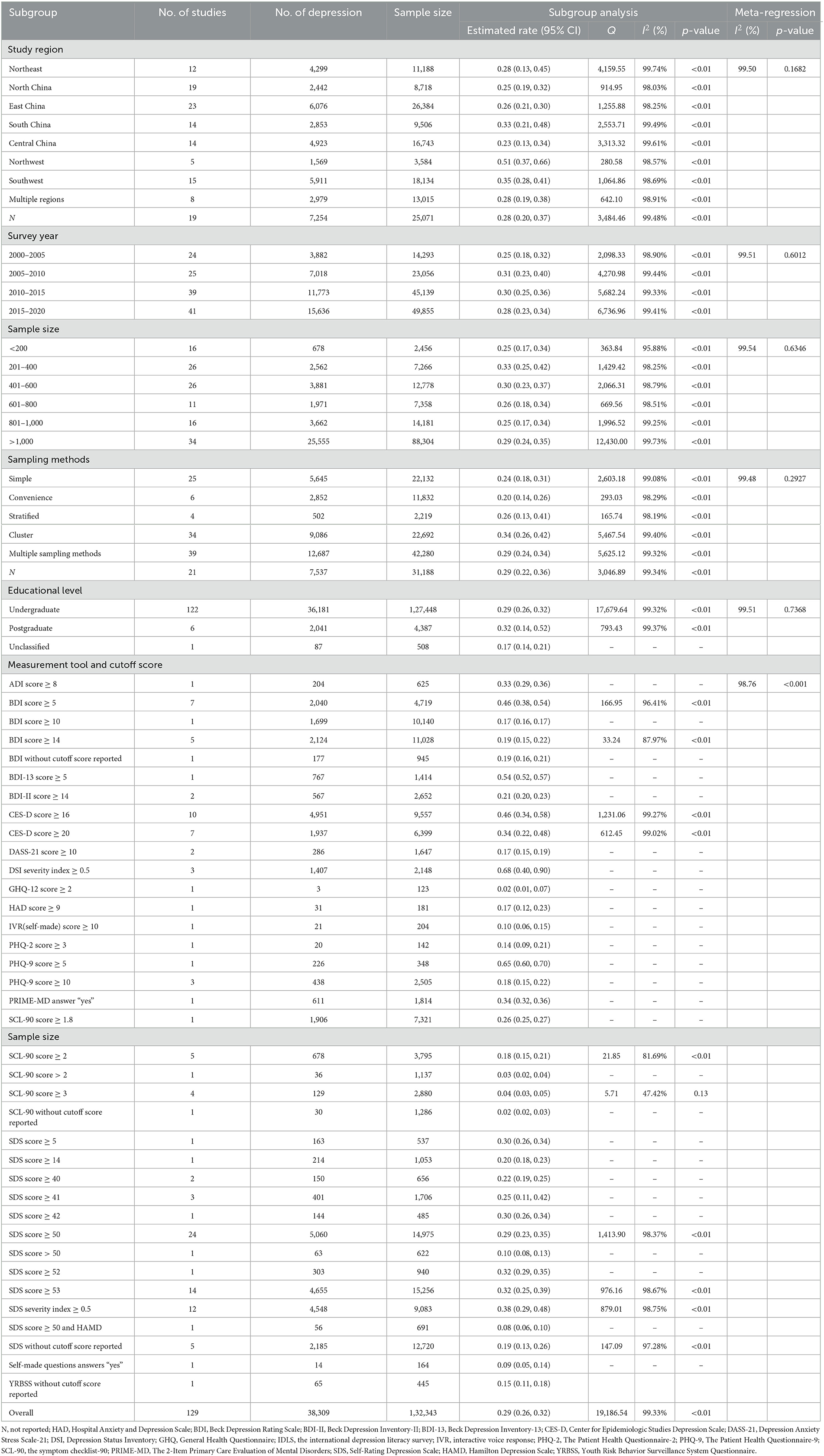

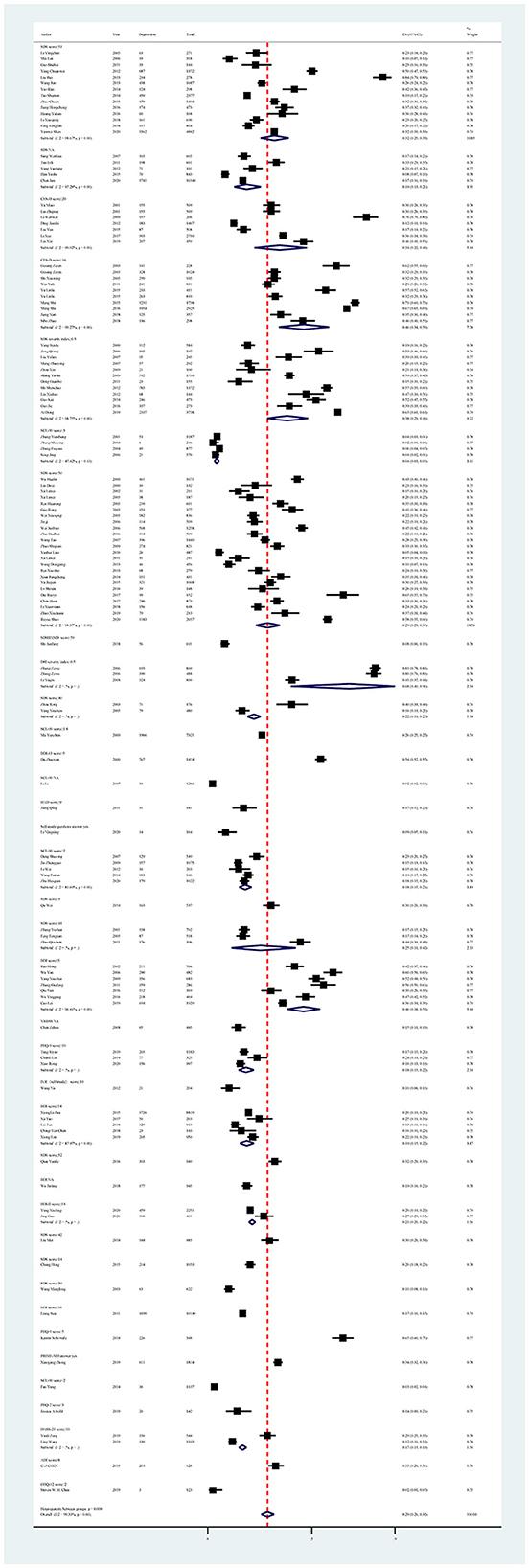

Depression

Depression symptoms reported in the 129 included studies yielded a pooled prevalence of 29% (38,309/132,343; 95% CI: 26%−32%), with substantial evidence of between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 99.33%; Figure 2, Table 4). Sensitivity analysis showed that no individual study significantly affected the overall result (Supplementary material S5, Figure 1). In subgroup analysis, heterogeneity was reduced in studies using BDI with a score ≥ 14 (I2 = 87.97%), SCL-90 with a score ≥ 2 (I2 = 81.69%), and SCL-90 with a score ≥ 3 (I2 = 47.42%; Table 4).

Subgroup analysis showed differences in prevalence based on study regions, recall periods, sampling methods, measurement tools, and cutoff scores. In this study, the pooled prevalence of depression symptoms was higher in the northwest region of China, with an estimate of 51% (95% CI: 37%−66%). Furthermore, studies conducted between 2005 and 2010 found a higher prevalence of depression symptoms (31%; 95% CI: 23%−40%). All studies that used a cluster sampling method reported a higher prevalence of depression symptoms than other sampling methods. In terms of measurement tool and cutoff score, studies using the Depression Status Inventory (DSI) with a severity index ≥ 0.5 and the BDI-13 with a score ≥ 5 reported a higher estimated prevalence, with a pooled prevalence of 68% (95% CI: 40%−90%) and 54% (95% CI: 52%−57%), respectively (Figure 3, Table 4).

In all univariate meta-regression analyses, only the measurement tool and cutoff score could explain the heterogeneity between studies (p < 0.001). The result of Egger's test showed publication bias, with p < 0.01 (Supplementary material S6, Figure 1).

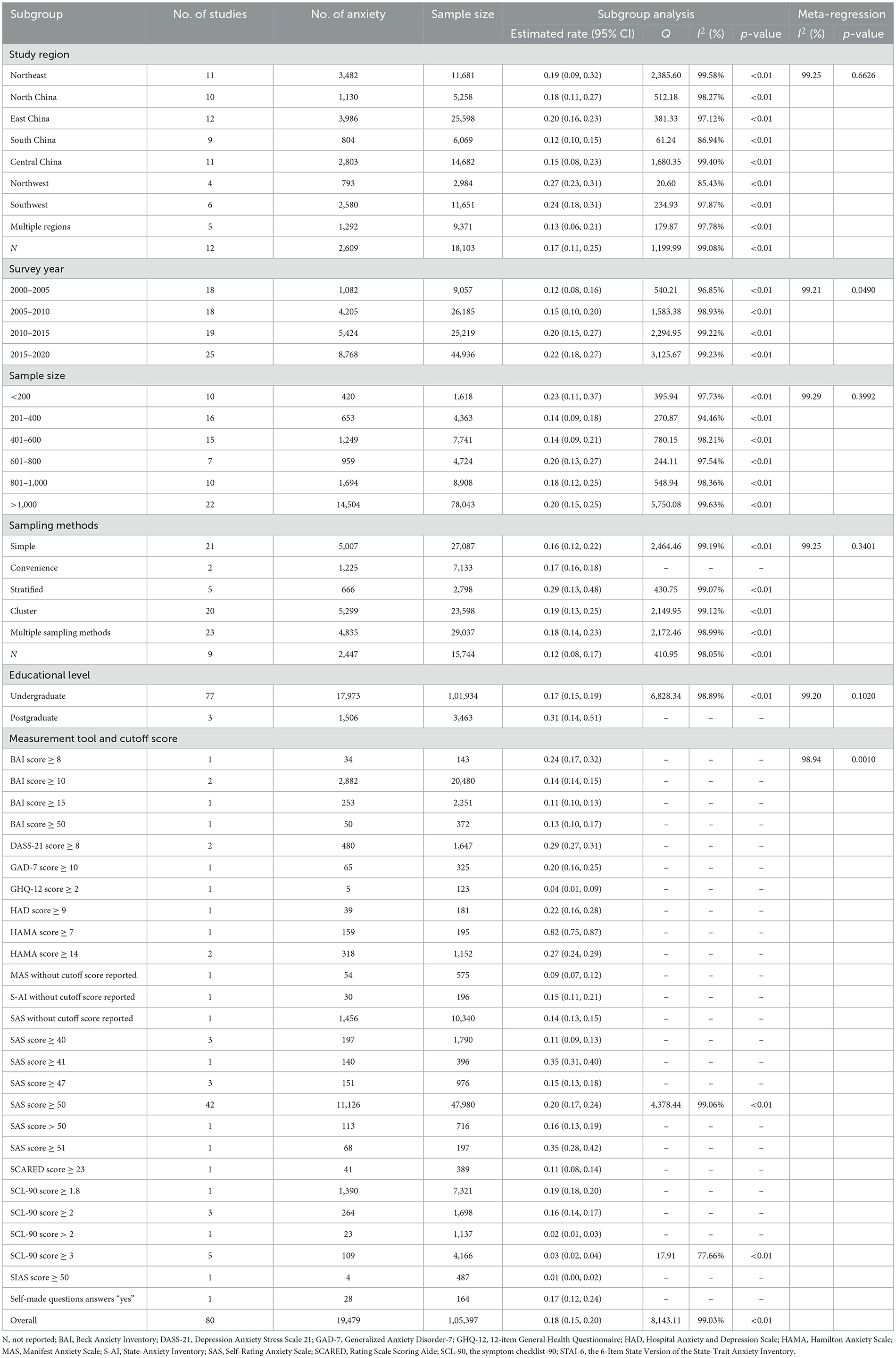

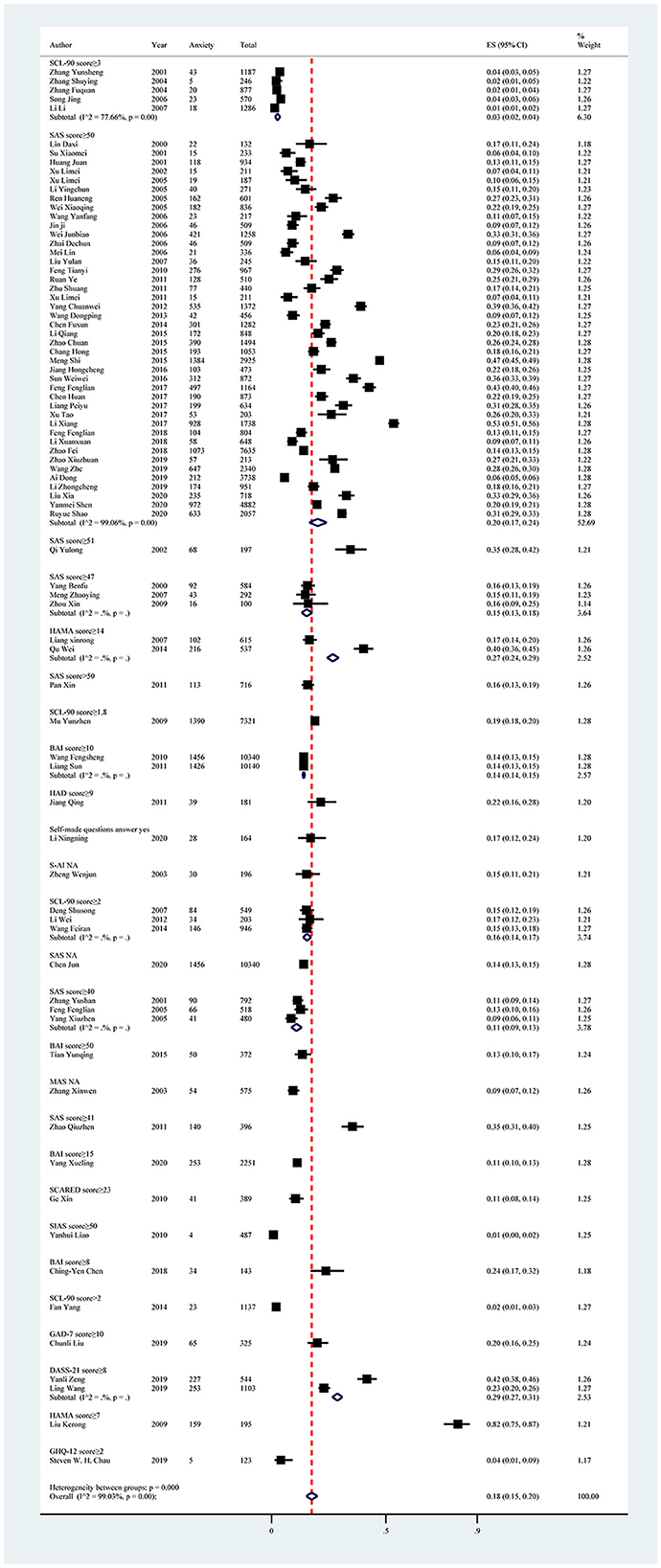

Anxiety

The anxiety symptoms reported in the 80 included studies yielded a pooled prevalence of 18% (19,479/105,397; 95% CI: 15%−20%), with substantial evidence of between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 99.03%; Figure 4, Table 5). Sensitivity analysis showed that no individual study significantly affected the overall result (Supplementary material S5, Figure 2). In the subgroup analysis, heterogeneity was found to be reduced in the southwest region (I2 = 97.87%), south China (I2 = 86.94%), and in studies using SCL-90 with a score ≥ 3 (I2 = 77.66%; Table 5).

Subgroup analysis showed differences in prevalence based on study regions, survey years, sampling methods, measurement tools, and cutoff scores. Among all study regions, the estimated prevalence of anxiety symptoms was highest in the northwest region (27%; 95% CI: 23%−31%), followed by the southwest region (24%; 95% CI: 18%−31%). Furthermore, studies conducted between 2015 and 2020 showed a higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms (22%; 95% CI: 18%−27%) than other years. Among all sampling methods, the estimated prevalence of anxiety symptoms was highest in studies using stratified sampling methods (29%; 95% CI: 13%−48%), followed by cluster sampling methods (19%; 95% CI: 13%−25%). In terms of measurement tools and cutoff scores, the highest prevalence of anxiety symptoms was reported in the study using the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMA) with a score ≥ 7 (82%; 95% CI: 75%−87%; Figure 5, Table 5).

In all univariate meta-regression analyses, only the measurement tool and cutoff score (p = 0.0010) could explain the heterogeneity between studies. Publication bias was found in the pooled prevalence analysis (p < 0.001 using Egger's test; Supplementary material S6, Figure 2).

Suicidal behaviors

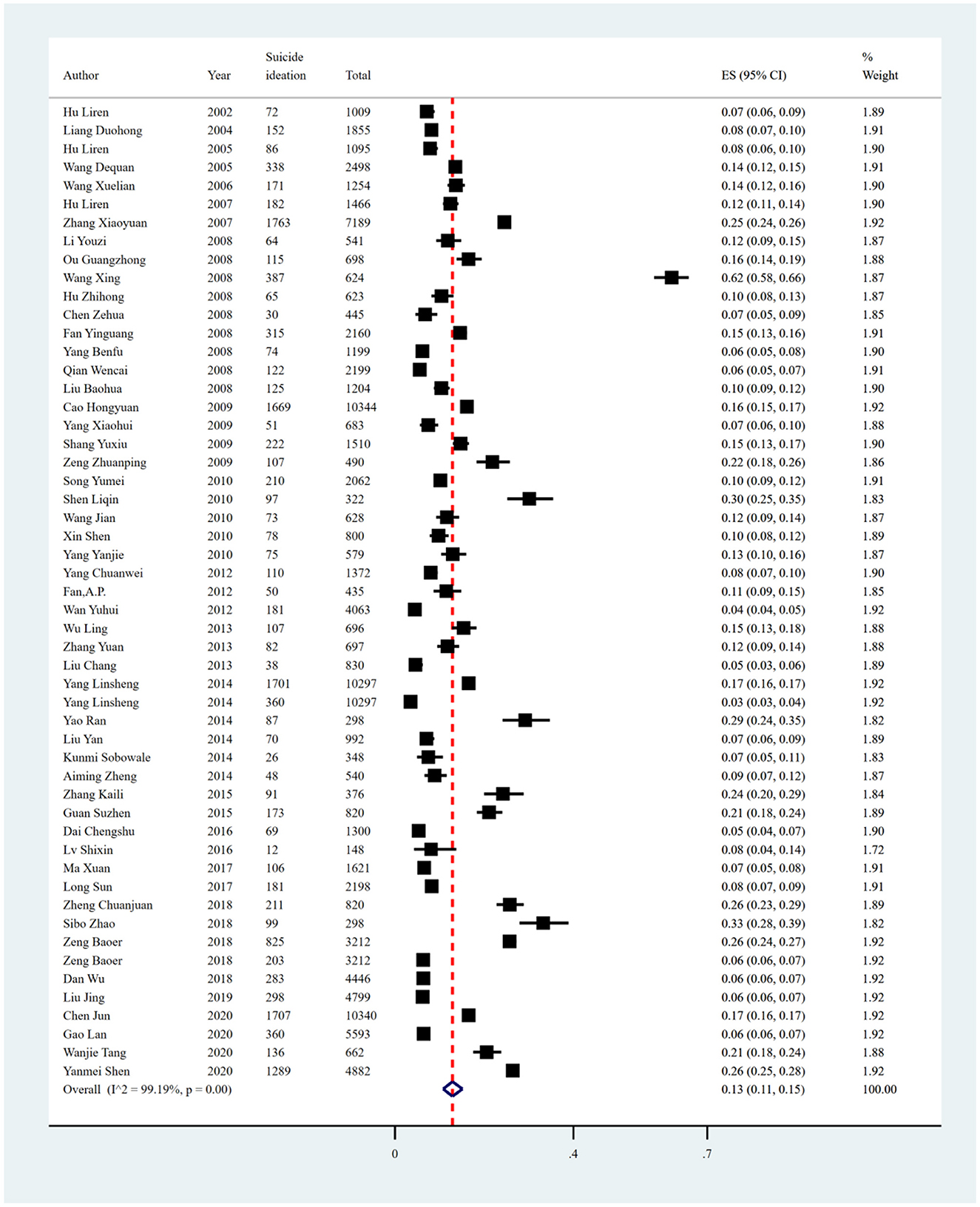

Suicidal ideation

The pooled prevalence of suicide ideation reported in 53 studies was 13% (15,546/119,069, 95% CI: 11%−15%), with significant heterogeneity of 99.19% among included studies (Figure 6, Table 6). Sensitivity analysis showed that no individual study significantly affected the overall result (Supplementary material S5, Figure 3). In the subgroup analysis, heterogeneity was found to be reduced in the northeast region (I2 = 85.58%), recall period of the past 1 week (I2 = 84.33%), and in studies using the Self-rating Idea of Suicide Scale (SIOSS) to identify suicide ideation (I2 = 88.71%).

Subgroup analysis showed differences in prevalence based on study regions, sampling methods, recall periods, and measurement tools. The estimated prevalence of suicide ideation was highest in central China (19%; 95% CI: 7%−34%), followed by south China (17%, 95% CI: 9%−26%) and the southwest region (17%; 95% CI: 15%−18%). Furthermore, studies conducted between 2005 and 2010 had a higher prevalence of suicide ideation than other survey years (15%; 95% CI: 11%−18%). The estimated prevalence was higher in those studies using convenience sampling methods (26%; 95% CI: 25%−28%) compared with other sampling methods. Among all recall periods reported in the included studies, those studies using the recall period “lifetime” reported a higher estimated prevalence of suicide ideation (19%; 95% CI: 15%−24%). In terms of measurement tools, studies using the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ), SSI, and Purpose in Life Test (PIL) reported higher pooled prevalence, with estimates of 27% (95% CI: 26%−28%), 24% (95% CI: 22%−27%), and 24% (95% CI: 20%−29%), respectively (Figure 7, Table 6).

Figure 7. Subgroup analysis of suicide ideation in Chinese medical students based on measurements tools.

Univariate meta-regression analyses demonstrated that measurement tools (p = 0.0282) could explain the potential source of the heterogeneity. Publication bias was found in the pooled prevalence analysis (p < 0.001 using Egger's test; Supplementary material S6, Figure 3).

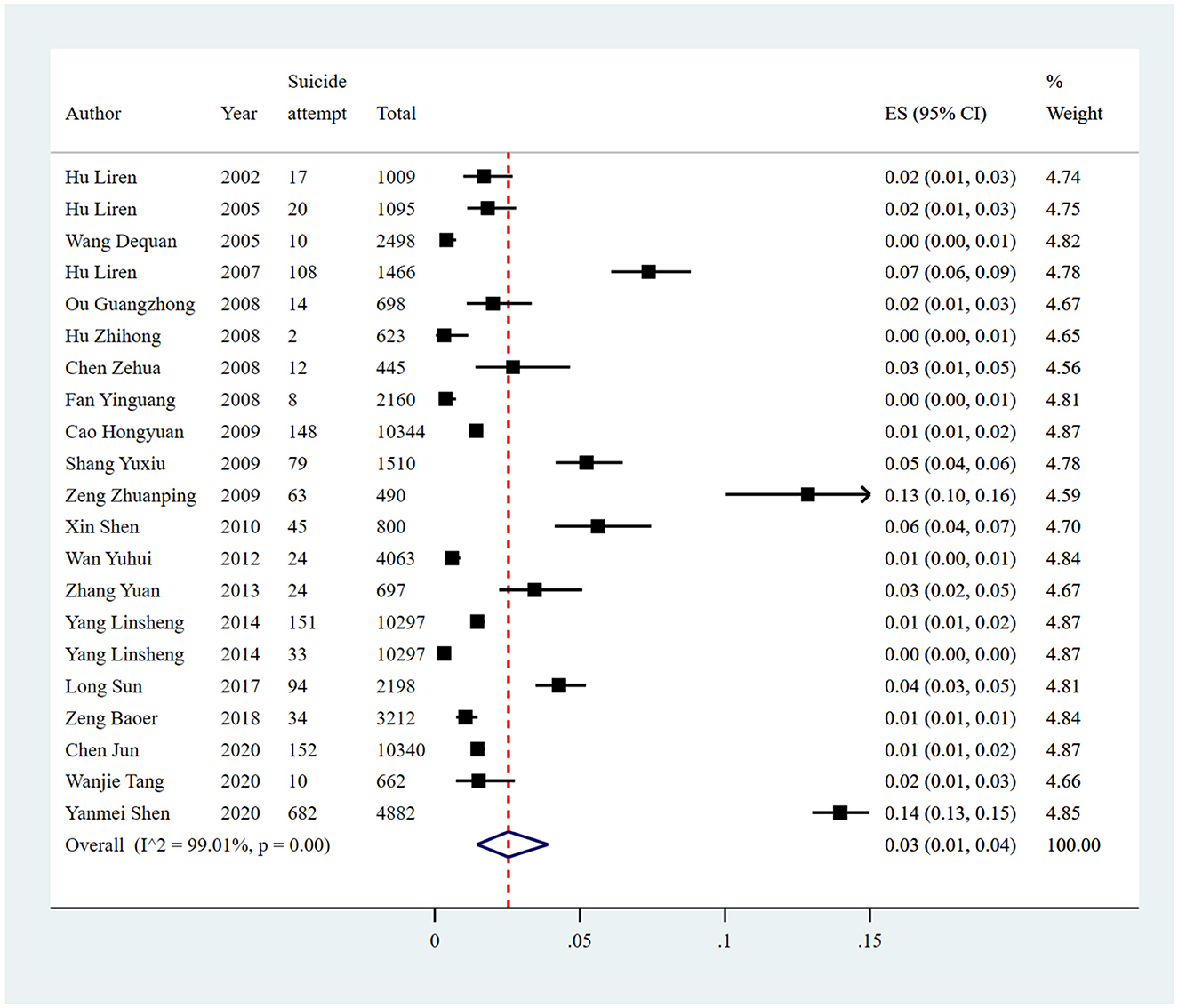

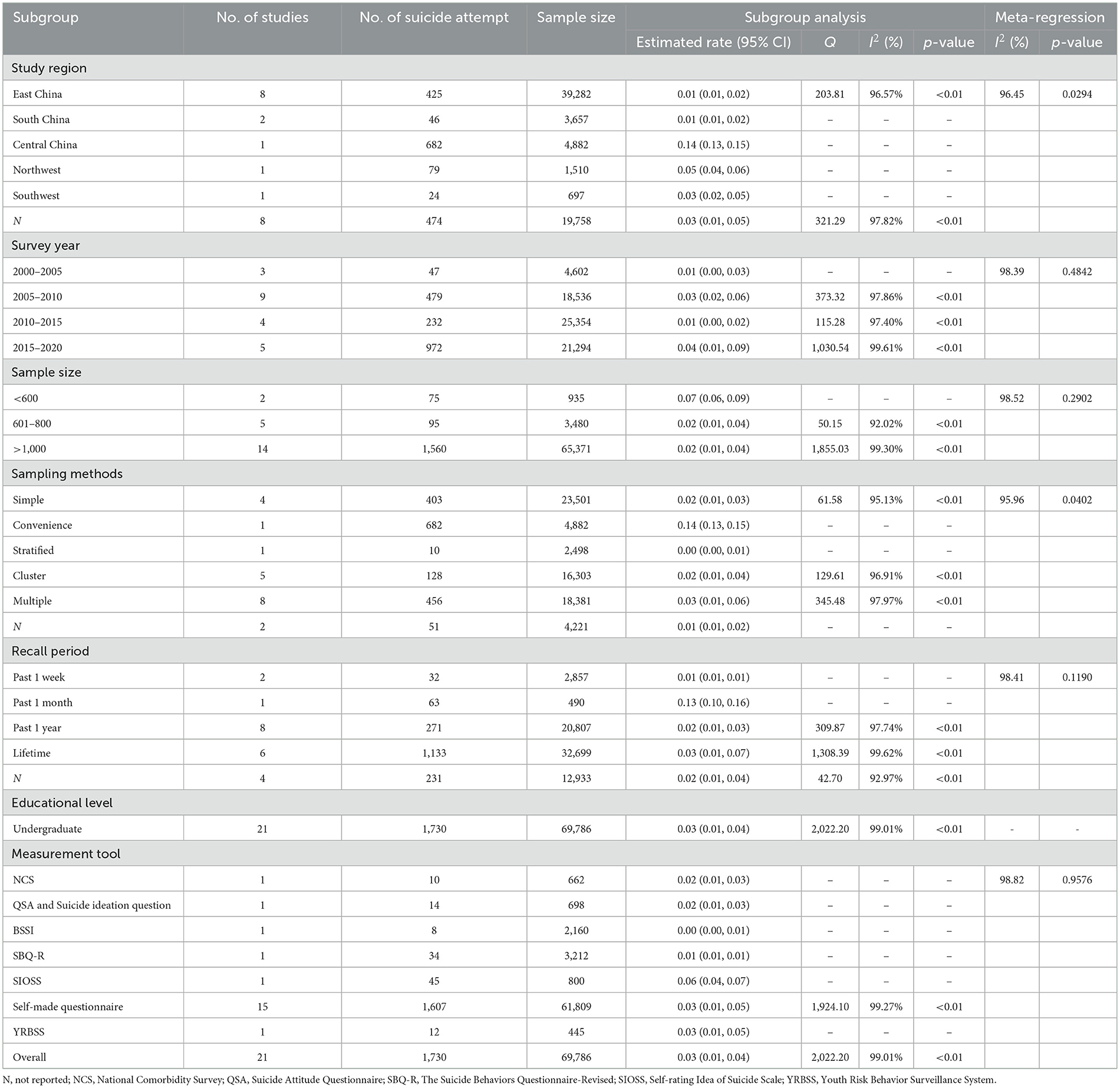

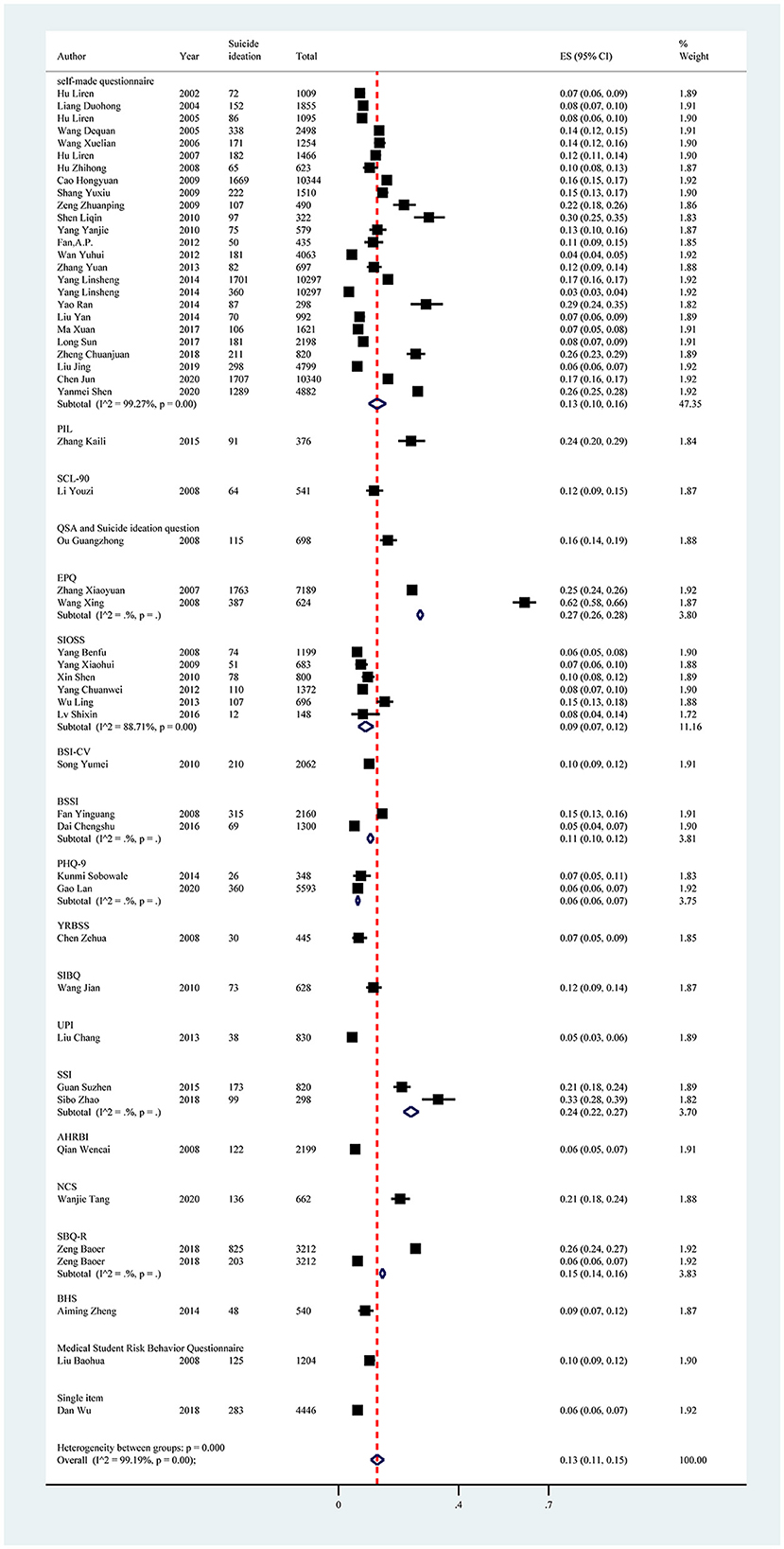

Suicidal attempt

The pooled prevalence of suicide attempts reported in 21 studies was 3% (1,730/69,786, 95% CI: 1%−4%), with significant heterogeneity of 99.01% among the included studies (Figure 8, Table 7). Sensitivity analysis showed that no individual study significantly affected the overall result (Supplementary material S5, Figure 4).

Subgroup analysis showed differences in prevalence based on study regions, survey years, sampling methods, recall periods, and measurement tools. The estimated prevalence of suicide attempt was higher in central China (14%; 95% CI: 13%−15%) than other regions. Studies conducted between 2015 and 2020 (4%; 95% CI: 1%−9%) had a higher prevalence of suicide attempt than other survey years. Furthermore, the estimated prevalence was higher in those studies using convenience sampling methods (14%; 95% CI: 13%−15%) than other sampling methods. The studies with a recall period of the past 1 month reported a significantly higher pooled prevalence (13%; 95% CI: 10%−16%) than other recall periods. As for measurement tools, the studies using SIOSS reported a higher pooled prevalence of suicide attempt, with an estimate of 6% (95% CI: 4%−7%; Figure 9, Table 7).

Figure 9. Subgroup analysis of suicide attempt in Chinese medical students based on measurements tools.

Univariate meta-regression analyses demonstrated that study region (p = 0.0294) and sampling method (p = 0.0402) could explain the potential source of the heterogeneity. Publication bias was found in the pooled prevalence analysis (p < 0.001 using Egger's test; Supplementary material S6, Figure 4).

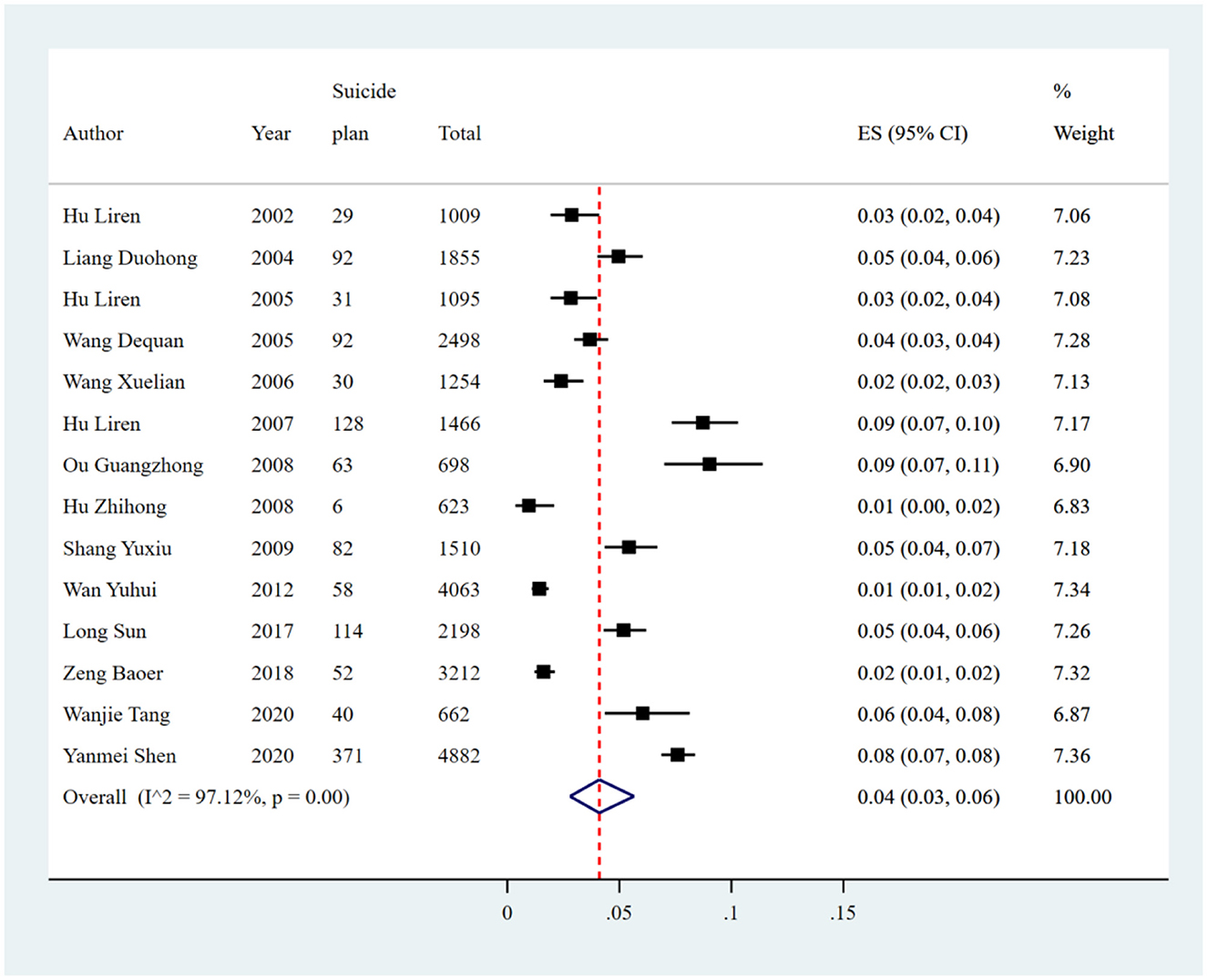

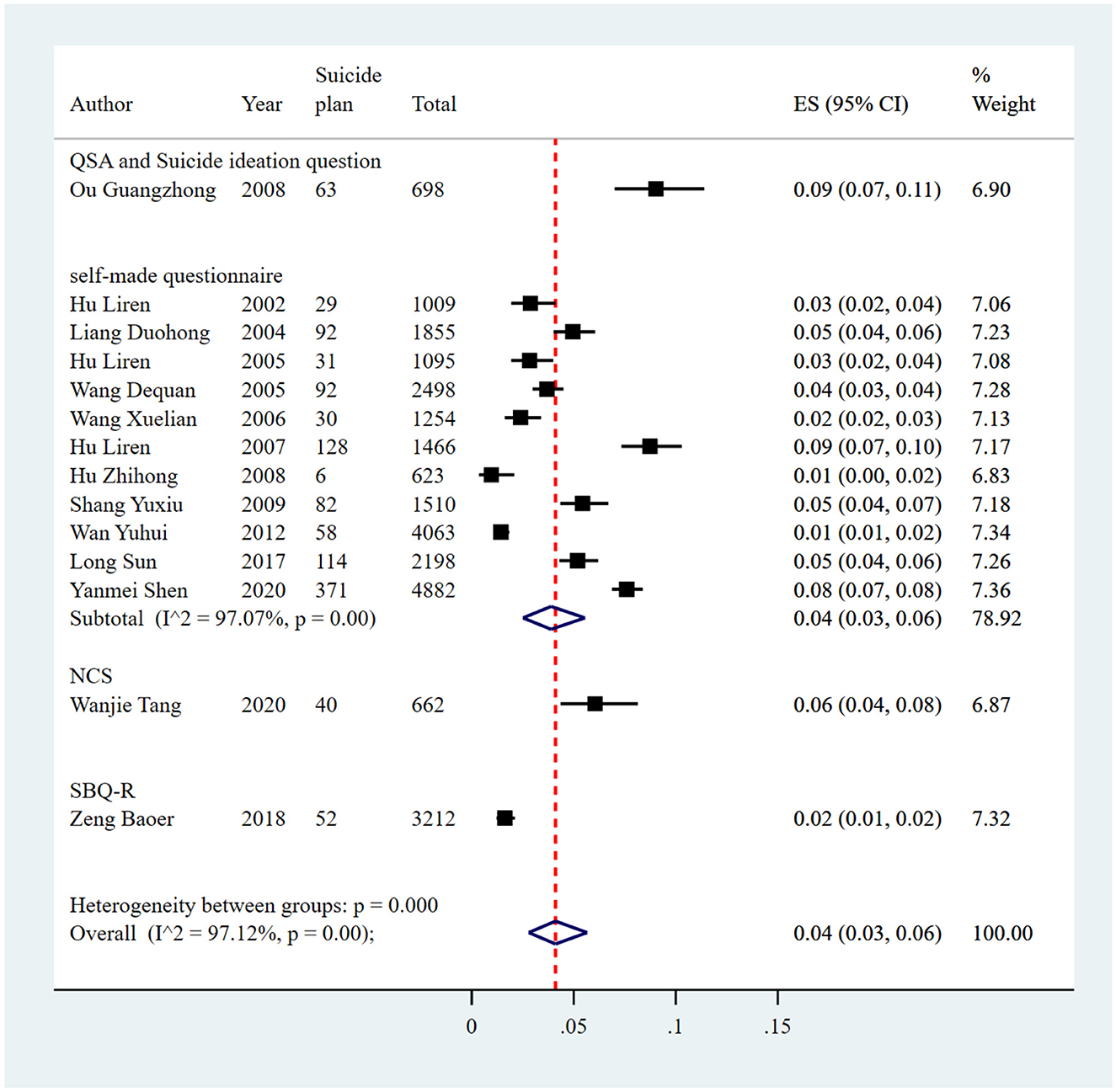

Suicidal plan

The pooled prevalence of suicide plan reported in 14 studies was 4% (1,188/27,025, 95% CI: 3%−6%), with significant heterogeneity of 97.12% among the included studies (Figure 10, Table 8). Sensitivity analysis showed that no individual study significantly affected the overall result (Supplementary material S5, Figure 5). In the subgroup analysis, heterogeneity was found to be reduced in the survey years from 2000 to 2005 (I2 = 74.16%).

Subgroup analysis showed differences in prevalence based on study regions, survey years, sampling methods, and measurement tools. The estimated prevalence of suicide attempt was higher in central China (8%; 95% CI: 7%−8%). Additionally, studies conducted between 2010 and 2015 had the lowest prevalence of suicide attempt (1%; 95% CI: 1%−2%) among all survey years. The estimated prevalence was higher in those studies using convenience sampling methods (8%; 95% CI: 7%−8%) than other sampling methods. Among all measurement tools, studies using the Questionnaire of Suicide Attitude (QSA) and Suicide Ideation Question reported a higher prevalence (9%; 95% CI: 7%−11%; Figure 11, Table 8).

Figure 11. Subgroup analysis of suicide plan in Chinese medical students based on measurements tools.

Significant results were not found in all univariate meta-regression analyses to explain the heterogeneity between studies. Publication bias was found in the pooled prevalence analysis (p < 0.001 using Egger's test; Supplementary material S6, Figure 5).

Discussion

Summary of results

To the best of our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the prevalence of CMDs among Chinese medical students. Our study revealed that the pooled prevalence of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, suicidal attempt, and suicidal plans was 29%, 17%, 13%, 3%, and 4%, respectively. The high prevalence values emphasize the need for CMD prevention and intervention for Chinese medical students.

Depression

Our study demonstrated a pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese medical students of 29%, which was higher than that for general university students (24.4%) in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (40) and previously reported studies (28.4 and 23.8%) in China (41, 42). This may be because medical students may experience higher academic pressure due to the arduous training curriculum, less time for relaxing or seeking psychological help (18, 43), and employment stress since pursuing a master's or even doctoral degree is commonly required to enter a hospital in China (44). These two factors are unique to medical students (45). Furthermore, our results revealed that the prevalence of depression symptoms among Chinese medical students was higher than the global prevalence in medical students (28.0%) (46). This finding could be the result of cultural differences among different countries. Compared with Western countries, Asian countries with a prominent Confucian Heritage Culture, such as China, emphasize academic excellence starting at a young age (47). Such high expectations often result in excessive pressure on students, which could influence their psychological wellbeing. In this situation, students, especially medical students, who bear more stressors from clinical curriculums and trainings, might report higher levels of depression.

The prevalence of depression in our study was similar to that reported by resident physicians worldwide (28.8%) (15), which suggested that depression was a problem affecting all levels of medical training. However, the result of our study was lower than that found in nursing students (34.0%) of similar age and education level. The possible explanation is that nursing has been a female-dominated profession for decades, and it has been confirmed that women tend to be more commonly affected by mental disorders than men (48).

Thus, it is suggested that more attention should be paid to medical students with signs and symptoms of depression, and timely screening and proper interventions are highly necessary.

Anxiety

This study demonstrated that the pooled prevalence of anxiety was 18%, which was much higher than that for Asian medical students (7.04%) (49). Interestingly, our result was lower than the prevalence of anxiety worldwide and even in other LMICs. For example, previous research has shown a pooled prevalence of anxiety among medical students of 33.8% worldwide (14), 32.9% in Brazil (50), and 34.5% in India (51). Different medical education systems and healthcare working environments among different countries could explain the discrepancies found in different areas.

However, anxiety among medical students was much higher than in the general population. Available data suggest that the prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in the general population ranges from 5 to 7% worldwide (52, 53). The long-term heavy academic burden (1), high intensity internships (2), complex doctor-patient relationships (54), and future uncertainty (5) could result in a higher prevalence of anxiety among medical students than the general population. Like depression, persistent anxiety symptoms could also lead to many undesirable consequences, such as poor academic performance, impaired cognitive function, burnout, and even suicidality (18, 55, 56). Thus, the anxiety in this population should be taken seriously and prevented effectively.

Suicidal behaviors

This study identified that the pooled prevalence of suicide ideation, suicide attempt, and suicide plan was 13%, 3%, and 4%, respectively. The pooled prevalence of suicide ideation in this study was similar to the global pooled prevalence (11.1%) and the pooled prevalence in China published in previous studies (11%) (10, 28). Furthermore, the pooled prevalence of suicide plan was also similar to the results of a Chinese language meta-analysis, which demonstrated that 4.4% of medical students reported suicidal plans (57).

When compared with physicians worldwide, minor differences were found between our findings and a previous meta-analysis. In this study, the summarized life-time prevalence of suicidal ideation was 17.4%, while the 1-year prevalence was 8.6% and the 6-month prevalence was 11.9%. With respect to suicidal attempt, the lifetime prevalence was 1.8%, while the 1-year prevalence was 0.3% (58). Combined with the above results, Chinese medical students in our study were less likely to report suicidal ideation (2% in recent 6 months) but more likely to report suicidal attempt (2% in recent 1 year) than physicians in recent recall periods.

These results suggested that Chinese medical students, similar to other populations with clinical training (such as physicians), had a higher risk for suicide-related thoughts and behaviors. The possible reasons might be a high rate of depression, work burnout, medical adverse events and errors, and a lower likelihood of seeking psychological help among medical students and physicians (10, 59, 60). Effective preventive efforts and the accessibility of mental health services for medical students should be developed in the future.

Limitations of this review and included studies

Our study has some limitations. First, the data were mostly derived from studies with a cross-sectional design, which limited a dynamic analysis of mental distress in this meta-analysis. Second, the data from different specialties (e.g., clinical medicine, dental medicine, preventive medicine, and nursing) and grades could not be extracted for final analysis, leaving substantial heterogeneity among studies unexplained. Third, it was impossible to perform a gender analysis since many studies did not provide separate prevalences of mental disorders for men and women. Fourth, a wide variety of screening instruments with different cutoff scores for mental distress were used in different studies, resulting in high heterogeneity across individual studies. Fifth, current studies on mental distress among Chinese medical students focused on limited mental problems. The investigation of other mental distresses such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, irritable bowel syndrome, bipolar disorders, and combinations of these was lacking in most studies. Finally, publication bias existed in our study, and the results should be interpreted with caution.

Implications for further research

Most included studies used a cross-sectional design with small sample sizes, which limits the generalization of the results to a wider population. Thus, future research should include prospective, randomized, multicenter studies with larger sample sizes. Additionally, most included studies solely focused on major mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal behaviors. Future studies should investigate other mental health disorders, such as bipolar, obsessive-compulsive, and eating disorders, alone and in combination. More subgroup and stratified analyses are also suggested to identify the prevalence of mental health problems in different subgroups of Chinese medical students, such as different grades, to provide targeted and personalized intervention programs. Finally, more interventional studies are needed to find ways to address the poor mental health of this population.

Implications for practice

Given the high prevalence of mental health disorders among medical students, there is a pressing need for further research utilizing standardized screening instruments with valid cutoff scores to accurately assess those disorders. It is suggested that medical schools implement regular monitoring of students' psychological wellbeing and establish comprehensive psychological interventions or programs that have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing students' mental health disorders. For instance, organizing structured programs with validated approaches like life skills training (61) and mindfulness therapy (62) could be implemented for medical students experiencing anxiety. Additionally, providing mental support within the college setting, including mental health-related courses and accessible counseling centers, is essential (26). Furthermore, continuous efforts are necessary to destigmatize mental health issues among medical students and promote a culture of help-seeking behavior. Medical schools can play a vital role in this by explicitly stating that having mental health problems will not result in demerit points or negative consequences for students. Sharing the successful experiences of senior doctors in managing mental health challenges may also encourage medical students to approach their own mental health struggles more positively (14). By prioritizing standardized assessments, implementing evidence-based interventions, and fostering a supportive environment, medical schools can actively address the mental health needs of their students. This multifaceted approach can not only alleviate the burden of mental health disorders but also create a positive and thriving learning environment for future healthcare professionals.

Conclusion

Our findings showed that Chinese medical students had a high level of depression, anxiety, and suicidal behaviors. Thus, timely screening and targeted intervention programs in this population to improve their mental health are needed. However, high heterogeneity and publication bias across the included studies were found in this review, suggesting that the results should be interpreted with caution.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PX: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. JWa, ML, and JB: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, visualization, and writing—original draft. YC, BL, and RW: writing—original draft. JL and JWu: data curation, investigation, and methodology. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

PX was supported by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2022A1515110261) and the Guangzhou Basic and Applied Basic Research Project (No. 202201010205). JX was supported by the grant of the Science and Technology Project of Qiandongnan Prefecture (2022, No. 05). The funding bodies had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1116616/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

SRT, standardized residency training; MM, master of medicine; CMDs, common mental disorders; SDS, Zung's Self-Rating Depression Scale; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Rating Scale; SAS, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; SCL-90, the symptom checklist-90; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7; NCS, National Comorbidity Survey; SBQ, Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire; IES, Impact of Event Scale; DSI, Depression Status Inventory; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Scale; QSA, Questionnaire of Suicide Attitude; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Scale; SIOSS, Self-Rating Idea of Suicide Scale; PIL, Purpose in Life Test; EPQ, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; SSI, Scale for Suicide Ideation; CI, confidence interval; WPV, workplace violence.

References

1. Kang X, Zhang L, Zhang G, Lv H, Fang F. Research on psychological health status of Chinese Young doctors from Hebei province. Neuropsychiatry. (2016) 6:85–7. doi: 10.4172/Neuropsychiatry.1000125

2. Fawzy M, Hamed SA. Prevalence of psychological stress, depression and anxiety among medical students in Egypt. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 255:186–94. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.027

3. Perotta B, Arantes-Costa FM, Enns SC, Figueiro-Filho EA, Paro H, Santos IS, et al. Sleepiness, sleep deprivation, quality of life, mental symptoms and perception of academic environment in medical students. BMC Med Educ. (2021) 21:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02544-8

4. Roh M-S, Jeon HJ, Kim H, Han SK, Hahm B-J. The prevalence and impact of depression among medical students: a nationwide cross-sectional study in South Korea. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1384–90. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181df5e43

5. Lane A, McGrath J, Cleary E, Guerandel A, Malone KM. Worried, weary and worn out: mixed-method study of stress and well-being in final-year medical students. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e040245. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040245

6. Mosley TH, Perrin SG, Neral SM, Dubbert PM, Grothues CA, Pinto BM, et al. Stress, coping, and well-being among third-year medical students. Acad Med. (1994) 69:765–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199409000-00024

7. Curcio G, Ferrara M, De Gennaro L. Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Med Rev. (2006) 10:323–37. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.11.001

8. Aktekin M, Karaman T, Senol YY, Erdem S, Erengin H, Akaydin M, et al. Anxiety, depression and stressful life events among medical students: a prospective study in Antalya, Turkey. Med Educ. (2001) 35:12–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00726.x

9. Desalegn GT, Wondie M, Dereje S, Addisu A. Suicide ideation, attempt, and determinants among medical students Northwest Ethiopia: an institution-based cross-sectional study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. (2020) 19:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12991-020-00295-2

10. Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. (2016) 316:2214–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17324

11. Rao W-W, Li W, Qi H, Hong L, Chen C, Li C-Y, et al. Sleep quality in medical students: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies. Sleep Breath. (2020) 24:1151–65. doi: 10.1007/s11325-020-02020-5

12. Erschens R, Keifenheim KE, Herrmann-Werner A, Loda T, Schwille-Kiuntke J, Bugaj TJ, et al. Professional burnout among medical students: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Med Teach. (2019) 41:172–83. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1457213

13. Frajerman A, Morvan Y, Krebs M-O, Gorwood P, Chaumette B. Burnout in medical students before residency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. (2019) 55:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.08.006

14. Tian-Ci Quek T, Wai-San Tam W, Tran BX, Zhang M, Zhang Z, Su-Hui Ho C, et al. The global prevalence of anxiety among medical students: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:2735. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152735

15. Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, Khan R, Guille C, Angelantonio EDi, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. (2015) 314:2373–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15845

16. Chirico F, Magnavita N. Burnout syndrome and meta-analyses: need for evidence-based research in occupational health. Comments on prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 17:741. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030741

17. Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1998) 55:56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56

18. Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among US and Canadian medical students. Acad Med. (2006) 81:354–73. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009

19. Lins L, Carvalho FM, Menezes MS, Porto-Silva L, Damasceno H. Health-related quality of life of students from a private medical school in Brazil. Int J Med Educ. (2015) 6:149. doi: 10.5116/ijme.563a.5dec

20. Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Medical student distress: causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. (2005) 80:1613–22. doi: 10.4065/80.12.1613

21. Dyrbye LN, Harper W, Moutier C, Durning SJ, Power DV, Massie FS, et al. A multi-institutional study exploring the impact of positive mental health on medical students' professionalism in an era of high burnout. Acad Med. (2012) 87:1024–31. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31825cfa35

22. Khuwaja AK, Qureshi R, Azam S. Prevalence and factors associated with anxiety and depression among family practitioners in Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. (2004) 54:45.

23. Liu X, Feng J, Liu C, Chu R, Lv M, Zhong N, et al. Medical education systems in china: development, status, and evaluation. Acad Med. (2023) 98:43–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004919

24. Wang W. Medical education in china: progress in the past 70 years and a vision for the future. BMC Med Educ. (2021) 21:453. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02875-6

25. Xiong P, Hu SX, Hall BJ. Violence against nurses in China undermines task-shifting implementation. Lancet Psychiatry. (2016) 3:501. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30046-3

26. Mao Y, Zhang N, Liu J, Zhu B, He R, Wang X, et al. A systematic review of depression and anxiety in medical students in China. BMC Med Educ. (2019) 19:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1744-2

27. O'Reilly E, McNeill KG, Mavor KI, Anderson K. Looking beyond personal stressors: an examination of how academic stressors contribute to depression in Australian graduate medical students. Teach Learn Med. (2014) 26:56–63. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2013.857330

28. Zeng W, Chen R, Wang X, Zhang Q, Deng W. Prevalence of mental health problems among medical students in China: a meta-analysis. Medicine. (2019) 98:e15337. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015337

29. Jin T, Sun Y, Wang H, Qiu F, Wang X. Prevalence of depression among Chinese medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med. (2021) 27:2212–28. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1950785

30. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

31. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. (2000) 283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

32. Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. (2015) 13:147–53. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054

33. Santoso AMM, Jansen F, de Vries R, Leemans CR, van Straten A, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. Prevalence of sleep disturbances among head and neck cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. (2019) 47:62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.06.003

34. Yang W, Yang X, Cai X, Zhou Z, Yao H, Song X, et al. The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome among chinese university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public health. (2022) 10:864721. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.864721

35. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2002) 21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186

36. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. (2003) 327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

37. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. (1997) 315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

38. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. (1994) 50:1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446

40. Akhtar P, Ma L, Waqas A, Naveed S, Li Y, Rahman A, et al. Prevalence of depression among university students in low and middle income countries (LMICs): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2020) 274:911–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.183

41. Lei X-Y, Xiao L-M, Liu Y-N, Li Y-M. Prevalence, of depression among Chinese University students: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0153454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153454

42. Gao L, Xie Y, Jia C, Wang W. Prevalence of depression among Chinese university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72998-1

43. Ngasa SN, Sama C-B, Dzekem BS, Nforchu KN, Tindong M, Aroke D, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with depression among medical students in Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. (2017) 17:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1382-3

44. Xu L, Qiao X. Comparison and analysis about anxiety and depression of medical students during entrance and graduation stage. Chin Med Rec. (2011) 12:56–7.

45. Lin L, Yuqin W, Jing X. Investigation on psychological sources of stress among clinical medical students and its countermeasure. Occup Health. (2010) 26:486–9.

46. Puthran R, Zhang MW, Tam WW, Ho RC. Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: a meta-analysis. Med Educ. (2016) 50:456–68. doi: 10.1111/medu.12962

47. Tan JB, Yates S. Academic expectations as sources of stress in Asian students. Soc Psychol Educ. (2011) 14:389–407. doi: 10.1007/s11218-010-9146-7

49. Cuttilan AN, Sayampanathan AA, Ho RC-M. Mental health issues amongst medical students in Asia: a systematic review [2000–2015]. Ann Transl Med. (2016) 4:72. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2016.02.07

50. Pacheco JP, Giacomin HT, Tam WW, Ribeiro TB, Arab C, Bezerra IM, et al. Mental health problems among medical students in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Psychiatry. (2017) 39:369–78. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2223

51. Sarkar S, Gupta R, Menon V. A systematic review of depression, anxiety, and stress among medical students in India. J Ment Health Hum Behav. (2017) 22:88. doi: 10.4103/jmhhb.jmhhb_20_17

52. Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol Med. (2013) 43:897–910. doi: 10.1017/S003329171200147X

53. Ferrari A, Somerville A, Baxter A, Norman R, Patten S, Vos T, et al. Global variation in the prevalence and incidence of major depressive disorder: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Psychol Med. (2013) 43:471–81. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001511

54. Sparr LF, Gordon GH, Hickam DH, Girard DE. The doctor-patient relationship during medical internship: the evolution of dissatisfaction. Soc Sci Med. (1988) 26:1095–101. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90184-0

55. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, de Graaf R, Asmundson GJ, ten Have M, et al. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2005) 62:1249–57. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249

56. van Venrooij LT, Barnhoorn PC, Giltay EJ, van Noorden MS. Burnout, depression and anxiety in preclinical medical students: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Adolesc Med Health. (2017) 29:1–9. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2015-0077

57. Fuxia R, Xiuping H, Wenjun Z, Yulian R, Xiaolong C, Wang H, et al. Prevalence of suicidal plans among college students in mainland China: a meta-analysis. Chin J Sch Health. (2019) 40:42–5. doi: 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2019.01.011

58. Dong M, Zhou FC, Xu SW, Zhang Q, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, et al. Prevalence of suicide-related behaviors among physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2020) 50:1264–75. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12690

59. Dyrbye LN, Harper W, Durning SJ, Moutier C, Thomas MR, Massie Jr FS, et al. Patterns of distress in US medical students. Med Teach. (2011) 33:834–9. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.531158

60. Gold KJ, Sen A, Schwenk TL. Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the national violent death reporting system. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2013) 35:45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.08.005

61. Li C, Chu F, Wang H, Wang X-p. Efficacy of Williams LifeSkills training for improving psychological health: a pilot comparison study of Chinese medical students. Asia Pac Psychiatry. (2014) 6:161–9. doi: 10.1111/appy.12084

Keywords: common mental disorders (CMDs), depression, anxiety, suicidal behaviors, medical students, meta-analysis

Citation: Wang J, Liu M, Bai J, Chen Y, Xia J, Liang B, Wei R, Lin J, Wu J and Xiong P (2023) Prevalence of common mental disorders among medical students in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 11:1116616. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1116616

Received: 05 December 2022; Accepted: 04 August 2023;

Published: 31 August 2023.

Edited by:

Iman Permana, Muhammadiyah University of Yogyakarta, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Rebecca Erschens, University of Tübingen, GermanyBochra Nourhène Saguem, University of Sousse, Tunisia

Copyright © 2023 Wang, Liu, Bai, Chen, Xia, Liang, Wei, Lin, Wu and Xiong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peng Xiong, cGF1bHhpb25nd2h1QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Jinxingyi Wang1†

Jinxingyi Wang1† Min Liu

Min Liu Jian Bai

Jian Bai Yuhan Chen

Yuhan Chen Peng Xiong

Peng Xiong