- 1Beijing Key Laboratory of Applied Experimental Psychology, National Demonstration Center for Experimental Psychology Education, Faculty of Psychology, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

- 2Department of Psychology, School of Education, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, China

- 3School of Biology and Basic Medical Sciences, Medical College of Soochow University, Suzhou, China

- 4Psychological Education and Counselling Center, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

Introduction: Positive personality traits have been associated with personal well-being in previous research. However, the pathways through which positive personality may affect social well-being remain unclear. The present study hypothesized that the cognitive strategies for achieving well-being (i.e., orientation to happiness) mediate the association between good personality and social well-being in the Chinese culture.

Methods: A survey including the Good Personality Questionnaire, Social Well-being Scales, and Orientations to Happiness was administered to 1,503 Chinese secondary school students and adults.

Results: The results indicated that orientation to meaning mediated the relation between good personality and social well-being, but not orientation to pleasure.

Discussion: This is in line with the normative well-being model and the cognition instrumental model of well-being, which contributes to developing more targeted interventions to promote social well-being in the Chinese cultural.

1. Introduction

Well-being is a complex construct that is crucial for psychological and physical health (1). In the field of positive psychology, it was generally defined as an optimal psychological functioning (2–4). Research on well-being converged in three domains: subjective well-being (i.e., positive emotional functioning) (5), psychological well-being (i.e., happiness that comes from realizing one’s potential) (6), and social well-being (i.e., examines people’s well-being in a social-ecological context) (7, 8). Social well-being distinguished itself from the other two types of well-being since it focuses on assessing people’s well-being in a macro social context rather than from an individual perspective (9, 10). Compared with the other two types of well-being, social well-being is relatively less studied. As was mentioned before, social well-being is critical for health (1, 11), and exploring its contributors would provide new sights to promote a healthy life.

Positive personality traits, such as extraversion, were among the most studied variables related to social well-being (9, 12–15). The fact that most contemporary personality theories rely heavily on western cultural, sociological, and philosophical assumptions about people (16) made it challenging for psychologists to comprehend how personality models may vary between cultures. Psychologists used to compare distinctions between people living in various parts of the world using Western theories, concepts, and instruments, which means people are assessed by using the standards that are potentially culturally unsuitable for them. According to the cultural-psychology perspective (16), the meanings and behaviors of a specific sociocultural context determine individuals’ personalities. To describe the variations among Chinese people in terms of their daily lives, a Chinese personality idea is applied in this essay.

As far as Chinese Confucianism is concerned, a good personality is a positive moral character. There is no doubt that Confucianism’s classics have had the most impact on Chinese culture than any other literary or intellectual work. The Confucian philosophers, typified by Confucius and Mencius, who proclaimed the idea of “benevolence” and championed “benevolent administration” highly valued goodness. The essential cultural and psychological underpinnings of “benevolence” in China were based on the fundamental intellectual presuppositions of Confucius, Mencius, and Confucian scholar Seosso regarding human nature’s intrinsic goodness and evil. The Chinese people’s collective memory has been shaped by this cultural essence of goodness, which has left its stamp on their national identity, national character, and essential aspects of their personality (17). Personality psychology study with Chinese cultural components focuses on the good personality. Therefore, studying good personality is a good starting point for investigating the unique characteristics of Chinese people. In sum, the present study aimed to examine how Confucianism’s good personality may impact the social well-being of Chinese people.

The Social-Cognitive Model of Normative Well-Being postulates that personality and cognition both play important roles in well-being. It underlines how personality may influence well-being via cognitive factors (18). The model also describes how cognitive factors interact to preserve well-being under normal conditions according to empirical study (19, 20). Therefore, this study aimed to explore whether good personality in the Chinese cultural context augmented cognitive resources (e.g., orientation to happiness) and then improved social well-being.

1.1. Good personality and social well-being

Social well-being refers to an assessment of a person’s circumstances and social roles (7). It consists of five fundamental elements, including the perception and evaluation of social integration (i.e., a sense of belonging to the society), social acceptance (i.e., human nature and society are viewed positively), social actualization (i.e., a belief that the society will evolve), social contribution (i.e., being aware of one’s social value), and social coherence (i.e., a sense of meaning living in the social world) (7, 13). The correlation between social well-being and (subjective and psychological) personal well-being is moderate (7, 21), suggesting that social well-being and personal well-being are related, but are different constructs (22). Social well-being deserves as much attention as personal well-being that is more often studied in the past. Given the naming of social well-being, it is influenced by the cultural context by nature. Specifically, western culture stresses individual autonomy, whereas individuals in eastern cultures, such as Chinese, value social embeddedness and care more about contributing to others, the country, and the society (8, 23).

Good personality is characterized by positive moral personality in Chinese Confucianism, referring to whether s/he will be helpful to others (24, 25). Structure, inclination, sociality, and morality are the fundamental characteristics of good personality (24, 25). In this sense, the four qualities of a good personality are integrity, altruism, amiability, and magnanimity (24, 25). Dispositions allude to the reality that people of various good personalities often express their words and acts with a specific moral slant. Dual processing systems theory states that people have two processing systems: deliberate processing (controlled processing), which involves slow, energy-intensive conscious processing; and intuitive processing (heuristic processing), which concerns quick, low-energy processing that allows people to act by their inclinations and inner thoughts (26). Kindness individuals behave in a beneficial way intuitively (26). A good personality is formed due to many different social influences, and personality also affects how other people perceive and react to you in social situations.

According to Hillson (1999), personality qualities can be classified as positive and negative (27). In terms of stress-coping, positive personality is associated with problem-focused coping strategies (e.g., positive reappraisal strategies) (28), whereas negative personality is related to emotional strategy [e.g., denial, venting of emotions (29, 30)]. This may partially explain why positive and negative personalities affect physical and mental health differently. Specifically, positive personality (e.g., openness, extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) is beneficial to mental health (31, 32), and it plays a significant role in promoting social well-being (9, 12, 15). In addition, the neural basis of the association between good personality and social well-being has also been revealed, which include the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (13), the orbitofrontal cortex (14), the right orbitofrontal sulcus (33), and the left postcentral sulcus (33). In contrast, negative personality may be detrimental to mental health, with research showing that Machiavellianism and psychopathy made it challenging to achieve long-term happiness (34).

Though previous research showed that moral character shaped subjective well-being (35) and predicted life satisfaction (36), little is known about the influence of good personality on social well-being. Concerning social well-being, amongst few studies conducted in Chinese, one found its correlation with big five personality (37) and another with family harmony and social dedication (38). Good personality is rooted in the Chinese cultural context, and examining the contribution of good personality to social well-being can provide intervention studies with important targets to promote social well-being. Thus, it is worthwhile to investigate how good personality affects social well-being, and we assumed a positive relationship between them.

1.2. Orientation to happiness as potential mediator

The social-cognitive model of normative well-being emphasizes the importance of personality and cognitive abilities in well-being, and it also assumes that cognitive variables could mediate the well-being effects of personality (18). Many studies have validated the normative well-being model outside Chinese culture (19, 20). The present study investigated whether good personality contributes to social well-being via the cognitive resources associated with orientations to happiness. Some research showed that cognitive variables were instrumental to understanding the link between personality traits and well-being, such that personality traits influence how individuals choose their situations and experience life, which further affects their subjective well-being (39, 40). It was found that cognitive mechanisms partially contribute to subjective well-being by mediating personality traits, supporting the instrumental model (41).

The present study aimed to understand the association between good personality and social well-being by considering the potential mediating role of the cognitive strategies individuals use to seek social well-being (i.e., orientation to happiness). As aforementioned, good personality is positive moral personality with Chinese cultural components (24, 25). Thus, this paper provides an opportunity to explore cognitive mediating variables in relation to culture. Culture has been suggested to significantly influence people’ happiness orientations (42). In the Chinese culture, harmonious interpersonal relationships (43) and dedication to society (i.e., putting others’ needs before one’s own) (44) are highly valued. A study showed that contribution to society provided Chinese happiness (45). That said, Chinese emphasize the importance of pursuing happiness through orientation to meaning. Meanwhile, due to China’s rapid economic growth and increasing globalization, people are more likely to be exposed to commercial advertisements through mass media (46, 47). Chronic exposure to such information made some Chinese endorse materialistic values and believe wealth acquisition is the foundation of happiness (48, 49). Moreover, materialistic values may facilitate hedonism and pleasure-seeking (50). Taking these into account, orientation to meaning and orientation to pleasure are two important mediators to consider when studying good personality and social well-being, especially in Chinese culture. In addition, a study showed that manipulating happiness orientation to meaningful rather than pleasant experience promotes well-being, further supporting the potential mediating role of orientation to happiness (51).

Based on previous research, there are two distinct but complementary cognitive strategies that individuals can use to pursue well-being: Eudaimonia and Hedonia (52). Eudaimonia believes that well-being comes from fully utilizing and developing oneself (6, 45). However, from the hedonistic perspective, an individual can achieve well-being by engaging in pleasure (52, 53). In a similar vein, the Orientations to Happiness Scale developed by Peterson and colleagues (53) encompassed two subscales: orientation to meaning and orientation to pleasure, which corresponds to eudaimonia and hedonia, respectively.

Positive personalities were found to be associated with orientation to happiness. For instance, positive personalities such as extraversion, agreeableness, hope, curiosity, gratitude, bravery, and conscientiousness were found consistently positively related to orientation to meaning (54, 55). However, the results about orientation to pleasure was inconsistent. For example, extraversion, hope, bravery, fairness, creativity, honesty, prudence, and modesty were found positively (54, 55), while honesty-humility was found negatively associated with orientation to pleasure (55). Albeit this inconsistency, most positive personalities were found to be positively associated with orientation to pleasure. Accordingly, we propose that good personality would be positively associated with orientation to meaning and orientation to pleasure.

In addition, the relationship between orientation to happiness and well-being has been extensively examined in previous studies (56–60), and the findings were relatively consistent. Specifically, meaning orientation seemingly played a more important role than pleasure orientation in predicting subjective well-being (54, 56, 61). This can be explained as orientation to meaning leads to better emotional regulation (56, 62) and more attention paid to interpersonal relationships and the world around them (63), which in turn leads to more resources for constructing well-being. In contrast, orientation to pleasure does not lead to the development of long-lasting emotional resources, but only short-term emotional improvements (62). Notably, these studies mainly focused on the association between happiness orientation and personal well-being (i.e., subjective well-being and psychological well-being) (15, 52, 53, 57–60), leaving social well-being less investigated. There is only one study found that social well-being correlated positively with orientation to meaning, while its correlation with orientation to pleasure was nonsignificant (64). Given the limited evidence, more empirical studies are needed for results validation.

1.3. An overview of the current study

The present study aimed to examine the mechanisms underlying the association between good personality and social well-being by exploring the potential mediating role of orientation to happiness. It was hypothesized that good personality was positively related to social well-being, and orientation to happiness mediated this relationship.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and procedure

Participants included high school, vocational college, and university students and those who had already graduated and started working. A total of 1,503 participants were included (age range: 14–57 years, Mage = 18.7 years, SD = 4.27, 543 males). Three participants did not report age (0.02%),592 were between 14 and 16 years (39.39%), 317 were between 17 and 18 years (21.09%), 498 were between 19 and 25 years (33.13%), and 93 were over 25 years (6.19%). Five participants did not report subjective socioeconomic status, and the socioeconomic status ranged from 1 to 10 (M = 6.10, SD = 1.52).

The participants were informed that the survey would remain confidential and not be revealed to anyone else, so that they would be able to complete it honestly. Upon completing the informed consent, participants completed a survey that measured good personality, orientations to happiness, and social well-being either online or in the classroom.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Good personality questionnaire

The Good Personality Questionnaire includes 15 items, covering four dimensions, namely integrity (4 items; e.g., “I can admit my mistakes to others truthfully”), altruism (5 items; e.g., “I will not hesitate to go to help when I see someone in danger”), amicability (3 items; e.g., “People around me think I’m an easy person to get close to”), and magnanimity (3 items; e.g., “I will help the people who have hurt me regardless past grievances”) (65). Participants were asked to rate their agreement or disagreement on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The reliability and validity of this questionnaire was proved to be satisfactory (24, 25, 66), and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the whole questionnaire and the four subscales were 0.89, 0.79, 0.81, 0.82, and 0.73, respectively in the present study.

2.2.2. Social well-being

The social well-being scale includes 15 items (7) containing five subscales, e.g., the actualization of society (3 items; e.g., “Society is constantly evolving and progressing”), the coherence of society (3 items; e.g., “It’s easy for me to understand what’s going on in the world”), the integration of society (3 items; e.g., “Being a part of my community makes me feel close to others”), the acceptance of society (3 items; e.g., “Other people’s problems matter to people”), and social contribution (3 items; e.g., “As part of my daily activities, I contribute to the community in any way I can”). Ratings are based on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the whole questionnaire and the five subscales were 0.89, 0.88, 0.76, 0.68, 0.93, and 0.75 in the present study.

2.2.3. Orientations to happiness

The Orientation to Happiness scale has two 6-item subscales that measure meaning orientation (e.g., “It is my responsibility to improve the world”) and pleasure orientation (e.g., “It is always important for me to consider whether or not what I am doing will bring me joy before making a decision”) separately (53). Participants rated each item from 1 (extremely unlike me) to 5 (extremely like me). A higher subscale score implies a higher likelihood of endorsing that orientation. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in the present study were 0.79 and 0.73 for these two dimensions, which were satisfactory.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The analyses were performed in IBM SPSS 25 and Mplus 7. First, the correlations between the main variables were calculated. Then a multiple mediation analysis was conducted with Mplus 7 to examine the mediating role of the orientations to happiness between good personality and social well-being. Based on the nonparametric bootstrap method (5,000 samples), a 95% confidence interval (CI) containing no zero was considered significant (66).

3. Results

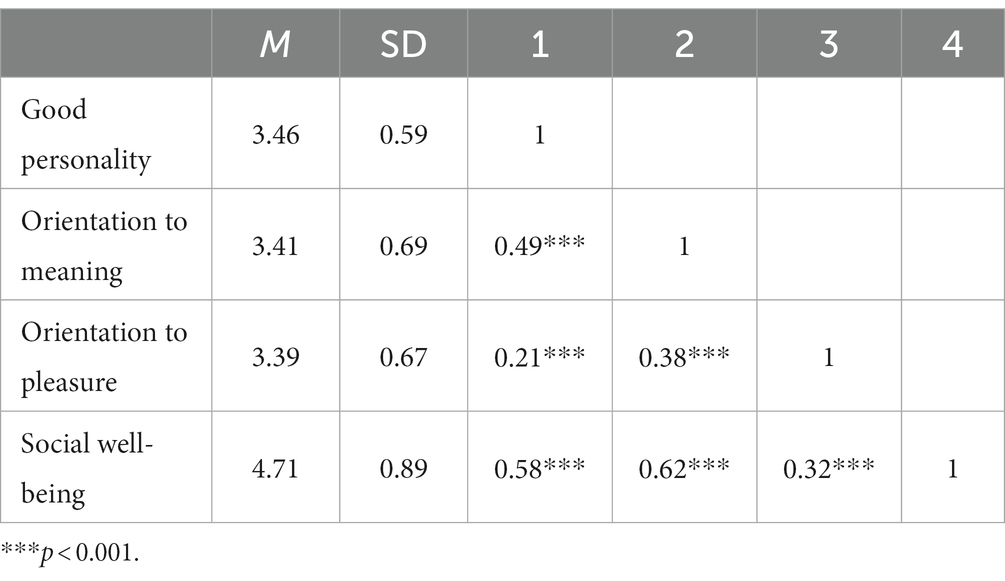

Table 1 presents correlations, means, and standard deviations between variables. Good personality was positively correlated with orientation to meaning (r = 0.49, p < 0.001), orientation to pleasure (r = 0.21, p < 0.001), and social well-being (r = 0.58, p < 0.001). Orientation to meaning was positively associated with orientation to pleasure (r = 0.38, p < 0.001) and social well-being (r = 0.62, p < 0.001). Orientation to pleasure (r = 0.32, p < 0.001) was positively correlated with social well-being (r = 0.32, p < 0.001).

Two latent variables (good personality, social well-being) and 9 observed variables formed the measurement model. A significant factor loading was observed for each indicator (ps < 0.001), which indicated that the observed indicators adequately reflected the two latent variables. The measurement model satisfactorily fitted the data: χ2 = 296.69, df = 26, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.08; SRMR = 0.04; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.92.

The mediation model with good personality as the independent variable, orientation to meaning and orientation to pleasure as mediating variables, and social well-being as the dependent variable were examined. Since age was positively correlated with good personality(r = 0.10, p < 0.001), orientation to meaning (r = 0.08, p < 0.01), and social well-being (r = 0.10, p < 0.001), The mediation model was run will age controlled. As three participants lacked age information, the analyses involved 1,500 participants.

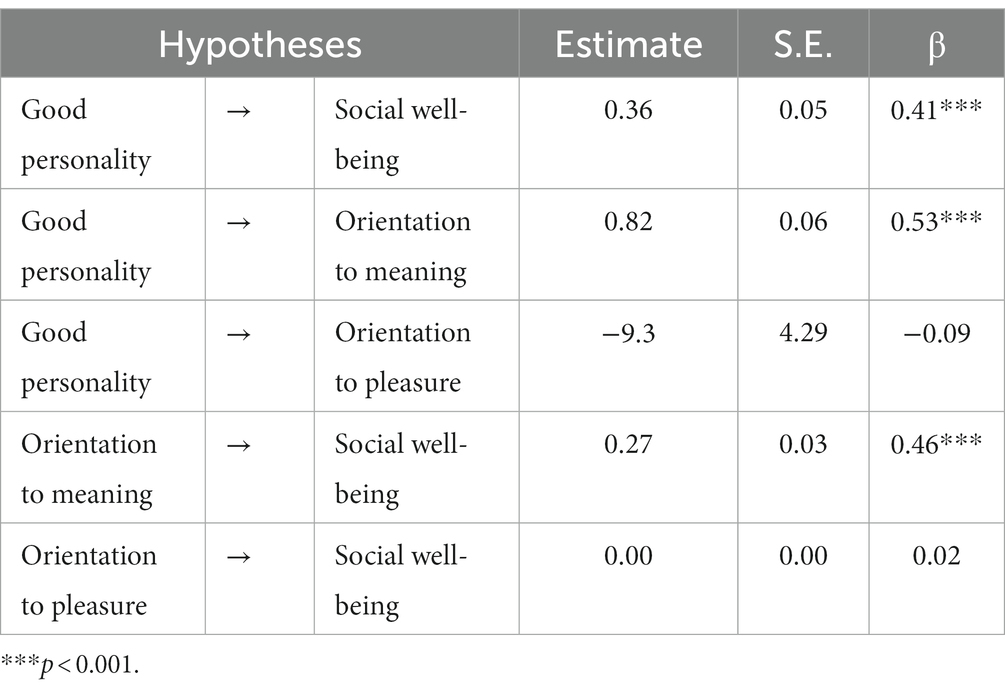

According to Table 2, good personality has a significant impact on social well-being (β = 0.41, p < 0.001) and orientation to meaning (β = 0.53, p < 0.001). Furthermore, orientation to meaning had a significant effect (β = 0.46, p < 0.001) on social well-being, as did not orientation to pleasure (β = 0.02, p = 0.41).

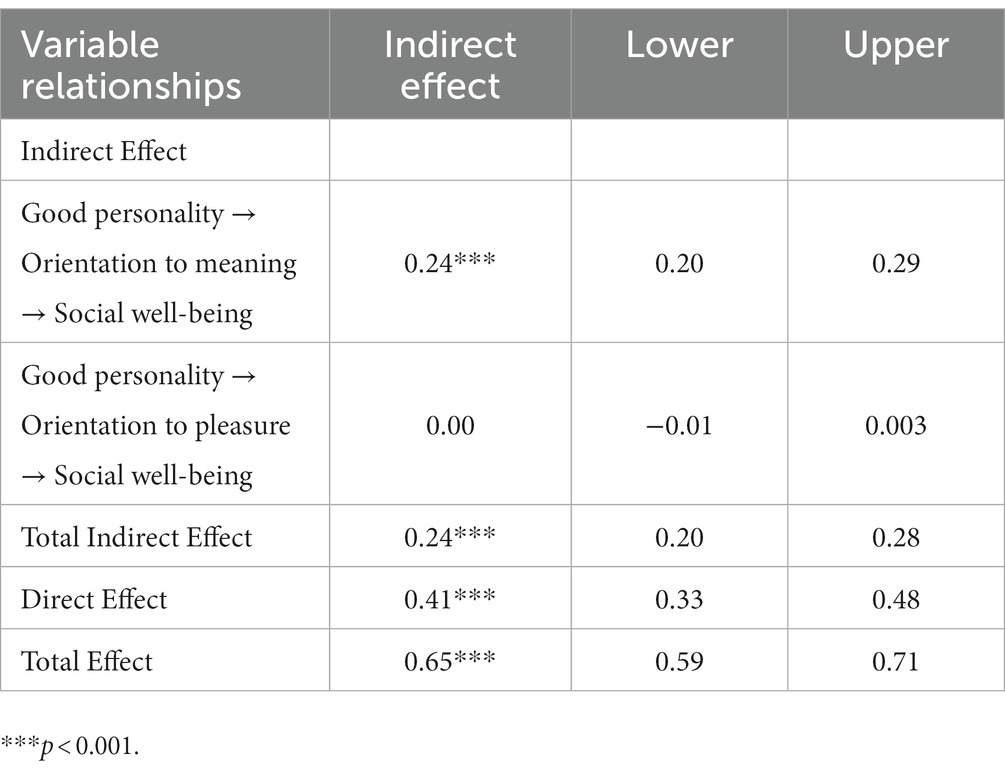

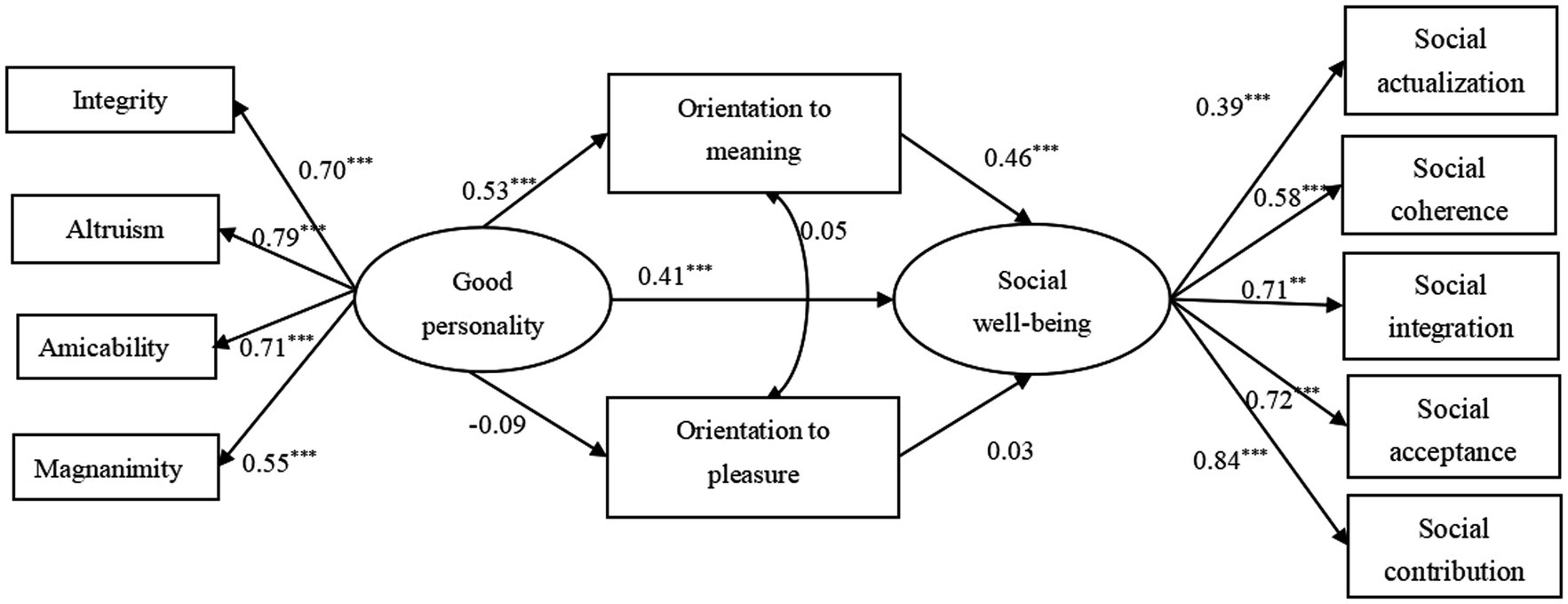

As shown in Table 3, orientation to meaning (95% CI = [0.20, 0.29]) partially mediated the association between good personality and social well-being, while the mediating effect of orientation to pleasure was not significant (95% CI = [−0.01, 0.003]), as was shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Shows the direct effects of the variables. Model fitted well to the data (χ2 = 228.52, df = 44, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.08; SRMR = 0.04; CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.90).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the association between good personality and social well-being, and the mediating role of orientations to meaning and pleasure. As it was hypothesized, a positive relationship between good personality and social well-being was demonstrated, which was mediated by meaning orientation but not pleasure orientation. This supported Lent’s normative model of well-being (18) and the cognition-instrumental model of well-being (41).

The finding that good personality and social well-being correlate positively was consistent with previous research (9, 12–15). These studies found an association between big five personality and social well-being in different cultures (37). There is also indirect evidence from a longitudinal study conducted in Chinese showing that Junzi personality (i.e., ideal persons) predicted interpersonal competence and satisfaction, which is an important component of social well-being (67). The positive relationship found here coincides with the Confucian cultural view, which strongly emphasizes virtue as a prerequisite for pleasure and holds that “Doing good deeds leads to happiness. Good deeds are the foundation of happiness. One cannot achieve happiness if s/he lacks goodness. The pursuit of happiness always enhances one’s goodness, and the maximum satisfaction is attained when goodness is perfected.” One of the theoretical contributions of this study is its combination of traditional philosophical, theoretical frameworks and culturally relevant personality notions to describe personal change and provide insights into social well-being in the context of Chinese culture.

Another major theoretical contribution of this study is that the results support Lent’s normative model of well-being (18) and the cognitive instrumental model proposed by Tkach and colleagues (41). The main finding of a mediating role of meaning orientation rather than pleasure orientation between good personality and social well-being indicates that good personality can facilitate social well-being by assigning individual talents in doing things that benefit humanity instead of entertaining oneself (68). This might be because orientation to meaning affects one’s emotional regulation (56, 62) and attention distribution (e.g., to their surroundings) (63), resulting in more resources available for configuring well-being. By contrast, orientations to pleasure did not lead to long-term but only momentary emotional enhancements (62).

The practical implication of this research includes improving Chinese citizen’ social well-being through cognitive intervention (e.g., orientation to meaning). The results may also inspire individuals to be kind. One’s sense of social well-being can be increased by acting morally, raising one’s sense of purpose and, ultimately, willingness to act morally. Furthermore, the present findings may provide some guidance in character cultivation and moral education.

Several limitations exist in this study. First, although all questionnaires used have good psychometric characteristics, they are self-reported measures. In addition, given the cross-sectional nature of this study, the causal relationship between the variables cannot be identified. To establish their causal relationship, longitudinal studies or laboratory experiments are needed in the future. Last, research involving more diverse ethnic and racial samples helps examine the generalization of the present findings.

5. Conclusion

According to the results of the current study, having good personality was positively associated with social well-being. Importantly, orientation to meaning partially mediate their relationship, which supported the normative and cognition instrumental models of well-being. Longitudinal research is called for in the future to clarify their causal relationship.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from Beijing Normal University (IRB Number: 202208220094). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

XX: conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, and writing—original draft preparation. YaL: conceptualization, validation, review, and editing. LJ: validation, data curation, review, and editing. YW: resources and data curation. MY: data curation and writing—review and editing. YiL: review and editing. YZ: resources and data curation. YX: funding acquisition and supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

There are two funding sources for this study: the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31671160) and the Major Project of the National Social Science Foundation (19ZDA363).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Van Lente, E, Barry, MM, Molcho, M, Morgan, K, Watson, D, Harrington, J, et al. Measuring population mental health and social well-being. Int J Public Health. (2012) 57:421–30. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0317-x

2. Ml, K. The neural correlates of well-being: a systematic review of the human neuroimaging and neuropsychological literature. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. (2019) 19:779–96. doi: 10.3758/s13415-019-00720-4

3. Lyubomirsky, S, Sheldon, KM, and Schkade, D. Pursuing happiness: the architecture of sustainable change. Rev Gen Psychol. (2005) 9:111–31. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111

4. Ryan, RM, and Deci, EL. On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and Eudaimonic well-being. Annu Rev Psychol. (2001) 52:141–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

5. Diener, E, Emmons, RA, Larsen, RJ, and Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. (1985) 49:71–5. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

6. Ryff, CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1989) 57:1069–81. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

8. Li, M, Yang, D, Ding, C, and Kong, F. Validation of the social well-being scale in a Chinese sample and invariance across gender. Soc Indic Res. (2015) 121:607–18. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0639-1

9. Hill, PL, Turiano, NA, Mroczek, DK, and Roberts, BW. Examining concurrent and longitudinal relations between personality traits and social well-being in adulthood. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. (2012) 3:698–705. doi: 10.1177/1948550611433888

10. Keyes, CLM. Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2005) 73:539–48. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539

11. Shapiro, A, and Keyes, CLM. Marital status and social well-being: are the married always better off? Soc Indic Res. (2008) 88:329–46. doi: 10.1007/s11205-007-9194-3

12. Joshanloo, M, Rastegar, P, and Bakhshi, A. The big five personality domains as predictors of social wellbeing in Iranian university students. J Soc Pers Relat. (2012) 29:639–60. doi: 10.1177/0265407512443432

13. Kong, F, Hu, S, Xue, S, Song, Y, and Liu, J. Extraversion mediates the relationship between structural variations in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and social well-being. Neuro Image. (2015) 105:269–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.10.062

14. Kong, F, Yang, K, Sajjad, S, Yan, W, Li, X, and Zhao, J. Neural correlates of social well-being: gray matter density in the orbitofrontal cortex predicts social well-being in emerging adulthood. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. (2019) 14:319–27. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsz008

15. Wilt, J, Cox, KS, and McAdams, DP. The Eriksonian life story: developmental scripts and psychosocial adaptation. J Adult Dev. (2010) 17:156–61. doi: 10.1007/s10804-010-9093-8

16. Markus, HR, and Kitayama, S. The cultural psychology of personality. J Cross-Cult Psychol. (1998) 29:63–87. doi: 10.1177/0022022198291004

17. Li, H, and Chen, AT. On the Chinese basic personality structure influenced by benevolence. J Southwest China Normal Univ. (2003) 29:16–21. doi: 10.13718/j.cnki.xdsk.2003.02.003

18. Lent, RW. Toward a unifying theoretical and practical perspective on well-being and psychosocial adjustment. J Couns Psychol. (2004) 51:482–509. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.51.4.482

19. Garriott, PO, Hudyma, A, Keene, C, and Santiago, D. Social cognitive predictors of first- and non-first-generation college students’ academic and life satisfaction. J Couns Psychol. (2015) 62:253–63. doi: 10.1037/cou0000066

20. Sheu, H-B, Mejia, A, Rigali-Oiler, M, Primé, DR, and Chong, SS. Social cognitive predictors of academic and life satisfaction: measurement and structural equivalence across three racial/ethnic groups. J Couns Psychol. (2016) 63:460–74. doi: 10.1037/cou0000158

21. Lamers, SMA, Westerhof, GJ, Kovács, V, and Bohlmeijer, ET. Differential relationships in the Association of the big Five Personality Traits with positive mental health and psychopathology. J Res Pers. (2012) 46:517–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2012.05.012

22. Steel, P, Schmidt, J, and Shultz, J. Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychol Bull. (2008) 134:138–61. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.138

23. Yang, D, and Zhou, H. The comparison between Chinese and Western well-being. Open J Soc Sci. (2017) 05:181–8. doi: 10.4236/jss.2017.511013

24. Jiao, L, Yang, Y, Guo, Z, Xu, Y, Zhang, H, and Jiang, J. Development and validation of the good and evil character traits (GECT) scale. Scand J Psychol. (2021) 62:276–87. doi: 10.1111/SJOP.12696

25. Jiao, L, Yang, Y, Xu, Y, Gao, S, and Zhang, H. Good and evil in Chinese culture: personality structure and connotation. Acta Psychol Sin. (2019) 51:1128–42. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2019.01128

26. Haidt, J, and Graham, JJSJR. When morality opposes justice: conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Soc Justice Res. (2007) 20:98–116. doi: 10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z

27. Hillson, JMC. (1999). An investigation of positive individualism and positive relations with others: Dimensions of positive personality. APA PsycInfo®(619438953; 1999-95002-010). Available at: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/investigation-positive-individualism-relations/docview/619438953/se-2 (Accessed 27, October 2022).

28. Connor-Smith, JK, and Flachsbart, C. Relations between personality and coping: a meta-analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2007) 93:1080–107. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1080

29. Ficková, E. Reactive and proactive coping with stress in relation to personality dimensions in adolescents. Stud Psychol. (2009) 51:149–60.

30. Roesch, SC, Wee, C, and Vaughn, AA. Relations between the big five personality traits and dispositional coping in Korean Americans: acculturation as a moderating factor. Int J Psychol. (2006) 41:85–96. doi: 10.1080/00207590544000112

31. Karademas, EC. Self-efficacy, social support and well-being the mediating role of optimism. Personal Individ Differ. (2006) 40:1281–90. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.10.019

32. Karademas, EC. Positive and negative aspects of well-being: common and specific predictors. Personal Individ Differ. (2007) 43:277–87. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.11.031

33. Li, Y, Li, C, and Jiang, L. Well-being is associated with local to remote cortical connectivity. Front Behav Neurosci. (2022) 16:737121. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2022.737121

34. Ng, HKS, Cheung, RY-H, and Tam, K-P. Unraveling the link between narcissism and psychological health: new evidence from coping flexibility. Personal Individ Differ. (2014) 70:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.06.006

35. Lerner, RM, Lerner, JV, Lewin-Bizan, S, Bowers, EP, Boyd, MJ, Mueller, MK, et al. Positive youth development: processes, programs, and problematics. J Youth Dev. (2011) 6:38–62. doi: 10.5195/JYD.2011.174

36. Zhou, Z, Shek, DTL, Zhu, X, and Lin, L. The influence of moral character attributes on adolescent life satisfaction: the mediating role of responsible behavior. Child Indic Res. (2021) 14:1293–313. doi: 10.1007/s12187-020-09797-7

37. Yu, Y, Zhao, Y, Li, D, Zhang, J, and Li, J. The relationship between big five personality and social well-being of Chinese residents: the mediating effect of social support. Front Psychol. (2021) 11:8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.613659

38. Wang, T, Jia, Y, You, XQ, and Huang, XT. Exploring well-being among individuals with different life purposes in a Chinese context. J Posit Psychol. (2021) 16:60–72. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2019.1663253

39. McCrae, RR, and Costa, PT. Adding Liebe Und Arbeit: The Full Five-Factor Model and Well-Being. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. (1991) 17:227–32. doi: 10.1177/014616729101700217

40. Strobel, M, Tumasjan, A, and SpÖRrle, M. Be yourself, believe in yourself, and be happy: self-efficacy as a mediator between personality factors and subjective well-being. Scand J Psychol. (2011) 52:43–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2010.00826.x

41. Tkach, C, and Lyubomirsky, S. How do people pursue happiness?: relating personality, happiness-increasing strategies, and well-being. J Happiness Stud. (2006) 7:183–225. doi: 10.1007/s10902-005-4754-1

42. Park, N, Peterson, C, and Ruch, W. Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction in twenty-seven nations. J Posit Psychol. (2009) 4:273–9. doi: 10.1080/17439760902933690

43. Bond, MH. The pan-culturality of well-being: but how does culture fit into the equation? Asian J Soc Psychol. (2013) 16:158–62. doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12024

44. Liu, L. Quality of life as a social representation in China: a qualitative study. Soc Indic Res. (2006) 75:217–40. doi: 10.1007/s11205-004-3198-z

45. Lu, L. Understanding happiness: a look into the Chinese folk psychology. J Happiness Stud. (2001) 2:407–32. doi: 10.1023/A:1013944228205

46. Chan, K, Zhang, H, and Wang, I. Materialism among adolescents in urban China. Young Consum. (2006) 7:64–77. doi: 10.1108/17473610610701510

47. Van Auken, S, Wells, LG, and Borgia, DJ. Assessing materialism among the future elites of China. J Int Consumer Market. (2014) 26:88–105. doi: 10.1080/08961530.2014.878202

48. Ku, L. Development of materialism in adolescence: the longitudinal role of life satisfaction among Chinese youths. Soc Indic Res. (2015) 124:231–47. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0787-3

49. Shek, DTL, Ma, CMS, and Lin, L. The Chinese adolescent materialism scale: psychometric properties and normative profiles In: S DTL, C Ma, L Yu, and J Merrick, editors, vol. 2014. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers. 239–53.

50. Lins, S, Dóka, Á, Bottequin, E, Odabašić, A, Pavlović, S, Merchán, A, et al. The effects of having, feeling, and thinking on impulse buying in European adolescents. J Int Consumer Market. (2015) 27:414–28. doi: 10.1080/08961530.2015.1027028

51. Giannopoulos, VL, and Vella-Brodrick, D. Effects of positive interventions and orientations to happiness on subjective well-being. J Posit Psychol. (2011) 6:95–105. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2010.545428

52. Huta, V, and Ryan, RM. Pursuing pleasure or virtue: the differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and Eudaimonic motives. J Happiness Stud. (2010) 11:735–62. doi: 10.1007/s10902-009-9171-4

53. Peterson, C, Park, N, and Seligman, MEP. Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: the full life versus the empty life. J Happiness Stud. (2005) 6:25–41. doi: 10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z

54. Buschor, C, Proyer, RT, and Ruch, W. Self- and peer-rated character strengths: how do they relate to satisfaction with life and orientations to happiness? J Posit Psychol. (2013) 8:116–27. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2012.758305

55. Pollock, NC, Noser, AE, Holden, CJ, and Zeigler-Hill, V. Do orientations to happiness mediate the associations between personality traits and subjective well-being? J Happiness Stud. (2016) 17:713–29. doi: 10.1007/s10902-015-9617-9

56. Ortner, CNM, Corno, D, Fung, TY, and Rapinda, K. The roles of hedonic and Eudaimonic motives in emotion regulation. Personal Individ Differ. (2018) 120:209–12. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.006

57. Chen, G-H. Validating the orientations to happiness scale in a Chinese sample of university students. Soc Indic Res. (2010) 99:431–42. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9590-y

58. Ruch, W, Harzer, C, Proyer, RT, Park, N, and Peterson, C. Ways to happiness in German-speaking countries: the adaptation of the German version of the orientations to happiness questionnaire in paper-pencil and internet samples. Europ Assoc Psychol Assess. (2010) 26:227–34. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000030

59. Schueller, SM, and Seligman, MEP. Pursuit of pleasure, engagement, and meaning: relationships to subjective and objective measures of well-being. J Posit Psychol. (2010) 5:253–63. doi: 10.1080/17439761003794130

60. Vella-Brodrick, DA, Park, N, and Peterson, C. Three ways to be happy: pleasure, engagement, and meaning--findings from Australian and us samples. Soc Indic Res. (2009) 90:165–79. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9251-6

61. Chan, DW. Orientations to happiness and subjective well-being among Chinese prospective and in-service teachers in Hong Kong. Educ Psychol. (2009) 29:139–51. doi: 10.1080/01443410802570907

62. Giuntoli, L, Condini, F, Ceccarini, F, Huta, V, and Vidotto, G. The different roles of hedonic and Eudaimonic motives for activities in predicting functioning and well-being experiences. J Happiness Stud. (2021) 22:1657–71. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00290-0

63. Sirgy, MJ. The Psychology of Quality of Life: Hedonic Well-Being, Life Satisfaction, and Eudaimonia. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer Science (2012).

64. Kong, F, Xue, S, and Wang, X. Amplitude of low frequency fluctuations during resting state predicts social well-being. Biol Psychol. (2016) 118:161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2016.05.012

65. Jiao, L, Shi, H, Xu, Y, and Guo, Z. Development and validation of the Chinese virtuous personality scale. Psychol Explor. (2020) 40:538–44.

66. Hayes, AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, vol. xvii. New York: Guilford Press (2013). 507 p.

67. Ge, X. Oriental wisdom for interpersonal life: Confucian ideal personality traits (Junzi personality) predict positive interpersonal relationships. J Res Pers. (2020) 89:104034. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104034

Keywords: good personality, social well-being, orientation to meaning, orientation to pleasure, multiple mediation

Citation: Xu X, Liu Y, Jiao L, Wang Y, Yu M, Lai Y, Zhang Y and Xu Y (2023) Good personality and social well-being: The roles of orientation to happiness. Front. Public Health. 11:1105187. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1105187

Edited by:

Wulf Rössler, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, GermanyCopyright © 2023 Xu, Liu, Jiao, Wang, Yu, Lai, Zhang and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yan Xu, eWFueHVfYm51QDE2My5jb20=

Xiaodan Xu

Xiaodan Xu Yang Liu2

Yang Liu2 Yongming Wang

Yongming Wang Mengke Yu

Mengke Yu Yingjun Zhang

Yingjun Zhang Yan Xu

Yan Xu