- 1Clinic for Rheumatology and Immunology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany

- 2Department of Public Administration, Getulio Vargas Foundation, São Paulo, Brazil

- 3Center for Metropolitan Studies, São Paulo, Brazil

- 4Institute of Political Science, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, Brazil

- 5Department of Health Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), London, United Kingdom

- 6College of Health and Biomedicine, University of Victoria, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 7Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Boston, MA, United States

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted healthcare and societies, exacerbating existing inequalities for women and girls across every sphere. Our study explores health system responses to gender equality goals during the COVID-19 pandemic and inclusion in future policies.

Methods: We apply a qualitative comparative approach, drawing on secondary sources and expert information; the data was collected from March–July 2022. Australia, Brazil, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the USA were selected, reflecting upper-middle and high-income countries with established public health and gender policies but different types of healthcare systems and epidemiological and geo-political conditions. Three sub-goals of SDG5 were analyzed: maternity care/reproductive health, gender-based violence, and gender equality/women's leadership.

Results: We found similar trends across countries. Pandemic policies strongly cut into women's health, constrained prevention and support services, and weakened reproductive rights, while essential maternity care services were kept open. Intersecting gender inequalities were reinforced, sexual violence increased and women's leadership was weak. All healthcare systems failed to protect women's health and essential public health targets. Yet there were relevant differences in the responses to increased violence and reproductive rights, ranging from some support measures in Australia to an abortion ban in the US.

Conclusions: Our study highlights a need for revising pandemic policies through a feminist lens.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic “exacerbates existing inequalities for women and girls across every sphere—from health and the economy to security and social protection” [(1), see also (2–6)]. Health research illustrates the intersections between gender inequalities and racial, sexual, economic, and other forms of social inequality during the pandemic (7–13). Lack of attention to women's healthcare needs (of all ages, including girls) in pandemic policies was accompanied by antifeminist discourses and violation of reproductive rights. The recent US Supreme Court decision to no longer guarantee safe and legal access to abortion and related care (14) is proof of these developments but marks only the tip of the iceberg (15, 16).

An increase in gender inequalities during a major global public health crisis calls for a critical review of both pandemic policies and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG5) “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls” (17) and its national/regional implementation, including gender mainstreaming approaches. However, a comprehensive gender-sensitive monitoring system of the impact of COVID-19 and pandemic policies is lacking; information is mainly collected by international NGOs (12, 18–20) and feminist networks (1, 8, 21, 22).

Gender equality issues remain marginal (if not absent) in most high-level COVID-19 policy briefs and pandemic recovery plans and are often not included in key recommendations (23, 24). Some statements mention women's health and gender equality but lack systematic data and analysis (25, 26). Against this backdrop, we sought to carry out a rapid assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on gender equality and the action taken in selected countries and areas of SDG5. Our research clarifies three major issues. How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect women's health and gender equality goals in upper-middle and high-income countries? What action (if any) was taken by health policy to protect gender equality goals during the pandemic? What role do the SDG5 targets play in future policies and pandemic recovery plans?

Methods

We apply a qualitative comparative approach based on explorative country case studies. The case studies draw on experts' information and secondary sources, including published literature, websites, and document analysis; the material was collected in March/April 2022 with some amendments until July 2022. A rapid assessment and expert-based approach seem to be most helpful in a situation where information is scattered, research evidence poor and comparative data lacking.

Connecting SDG5 “Gender Equality” and SDG3 “Health”: An analytical framework

Our study is informed by health systems and governance theories and comparative health policy (27–30) and research into gender and health and feminist global health policy (1, 11, 13, 21, 22, 31, 32). We focus on developments at the interface of SDG5 (11) and SDG3 “Ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages” (33). Inspired by the concept of “co-production” (28), we sought to identify intersecting targets. Four SDG5 (17) sub-targets were selected:

• End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere (SDG5.1).

• Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres (SDG5.2).

• Ensure women's full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life (SDG5.5).

• Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights (SDG5.6).

For SDG3 (33), we have chosen three sub-targets.

• Reduce maternal mortality (SDG3.1).

• Universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services (SDG3.7).

• Reduce violence everywhere (SDG target 16.1).

Another important area includes women's participation in new COVID-19 boards and female leadership in pandemic policy (34). The Pan-European Commission on Health and Sustainable Development (35) assessed the challenges posed by COVID-19 in the WHO European region and recommended, among others, improving gender equality and “explicit quotas… for the representation of women on public bodies that are involved in the formulation and implementation of health policy” (36). The concept of “feminist global health security” (37) moves beyond quotas and connects intersecting inequalities to gender mainstreaming, using infectious disease prevention and pandemic policy as examples (37).

Against this backdrop, we chose three interconnected topics of SDG3 and SDG5, considering different dimensions of gender equality.

1. Provision of maternity care and access to reproductive rights and services during the pandemic (SDG3.1, SDG3.7, and SDG5.6).

2. Prevention of gender-based and sexual violence against women during the pandemic (SDG3 16.1 and SDG5.2).

3. Support for gender equality and equity, including ensuring women's participation in all areas and on all levels of health policy-making and strengthening female leadership (SDG 5.1 and SDG5.5).

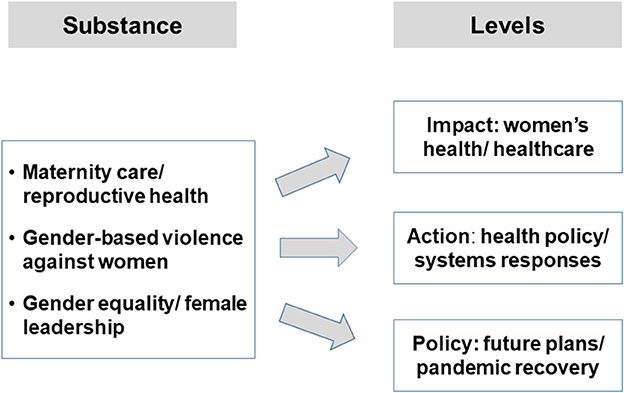

A generic conceptual framework (Figure 1) was developed, connecting the substance and the levels of analysis. “Substance” focuses on the three selected thematic areas, while “levels” are defined as follows: “impact” of the COVID-19 pandemic on women's health and service provision, “action” taken on the institutional level (with some consideration of civil society engagement) and future “policy” and pandemic recovery plans.

Selecting the country cases: Criteria and sample

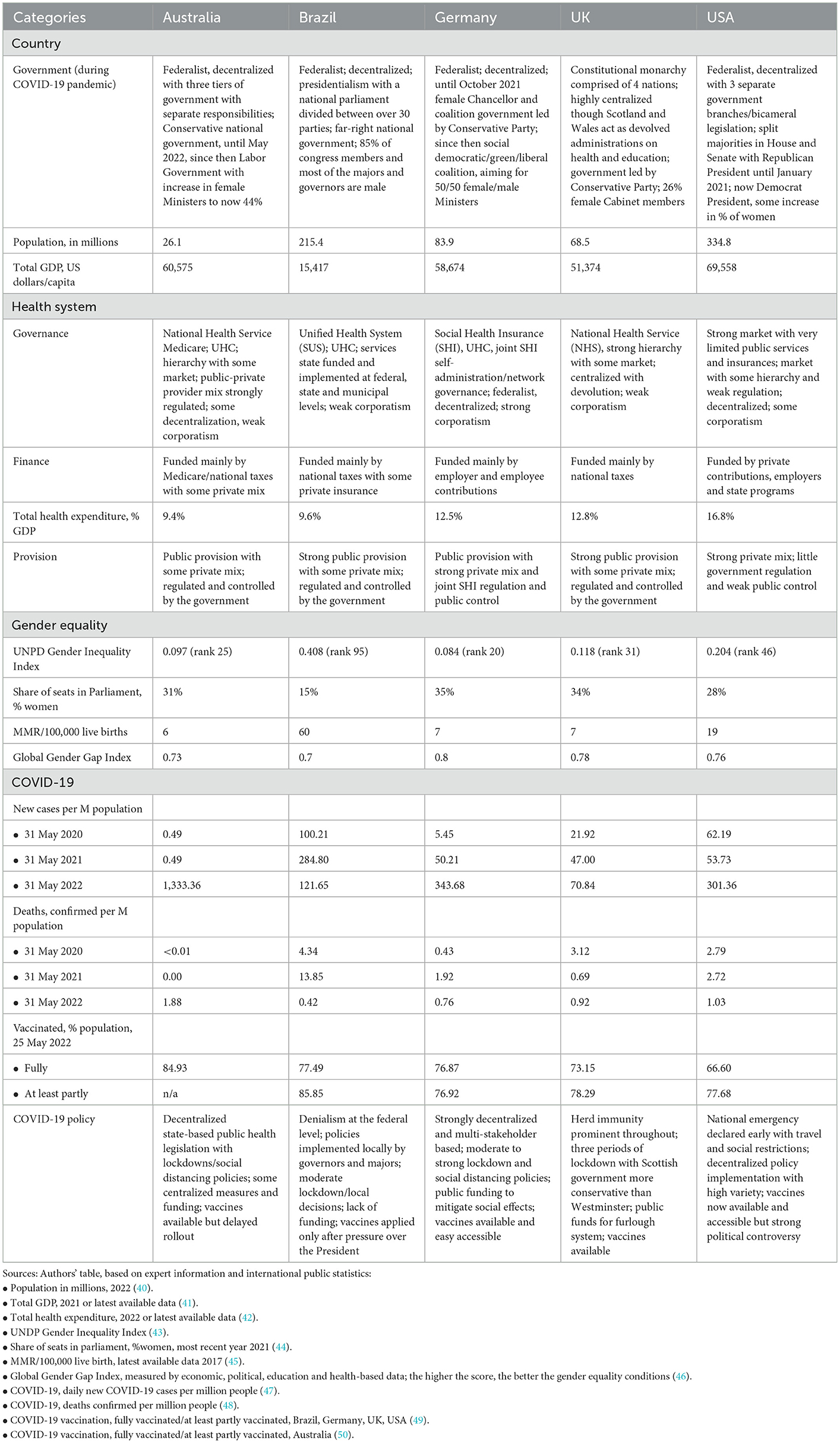

Comparative health policy mainly draws on health system typologies (38), scores and quantitative indicators. COVID-19 revealed the weaknesses of these approaches. For instance, the global Epidemic Preparedness Index (EPI) put the US and UK in the highest and Brazil in the second-highest category of preparedness on a five-point score (39), but all three countries performed extremely poorly during COVID-19 (Table 1). System-based approaches largely ignore gender equality or limit the analysis to a few basic sex-based quantitative indicators. Feminist studies, in contrast, have developed alternative suggestions that take into account complexity and qualitative research (7, 21, 22, 51).

Our country sample is inspired by more complex qualitative approaches and moves beyond typologies. We consider diversity in relation to the geographical location, the types/institutional conditions of governments and healthcare systems, COVID-19 indicators and pandemic policies (Table 1). The selected countries show also some variation in relation to gender equality measures but have established gender equality policies, humanitarian rights and democratic political institutions. Our sample comprises five upper-middle and high-income countries: Australia, Brazil, Germany, the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (USA).

Collecting and analyzing country data comparatively: A qualitative approach

We developed a step-by-step approach, informed by qualitative comparative research.

Step 1: Based on the framework shown in Figure 1, a topic guide was developed and agreed upon among authors, which served as a template for preparing the country cases. Information was collected for each country by the respective author(s) in our team and a first country draft was prepared.

Step 2: The lead authors discussed and reviewed all case studies, identified gaps, and queries, harmonized the categories and terminology and produced a revised, more coherent topic guide. Findings were discussed and adapted by the team; the authors revised their country cases accordingly and prepared a more condensed draft.

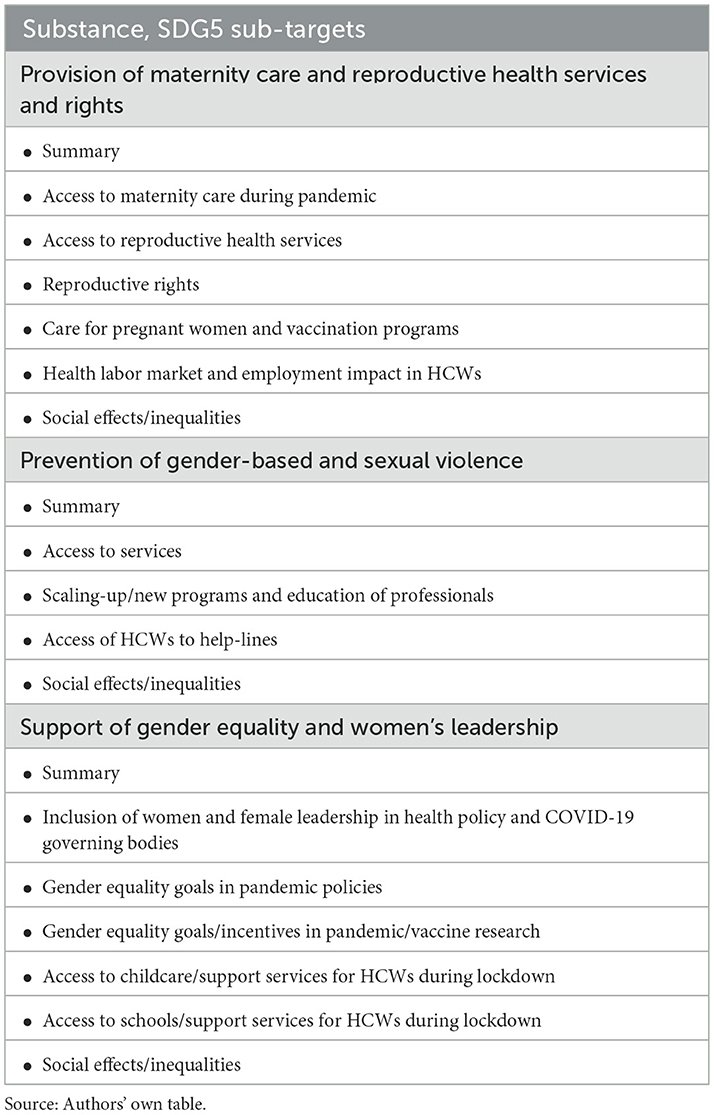

Step 3: the procedure was repeated until the topic guide was sufficiently coherent and standardized, comprising 19 items related to three major research areas (Table 2). Gaps were closed and the material was summarized in a table prepared for every country (Tables S1–S5 in Supplementary Appendix).

The comparative analysis followed a similar approach. The two lead authors carried out the first analysis across the five cases and prepared a draft manuscript, which all authors discussed and revised. The procedure was repeated until the findings were sufficiently condensed, generalized categories developed and agreement achieved on the findings.

Results

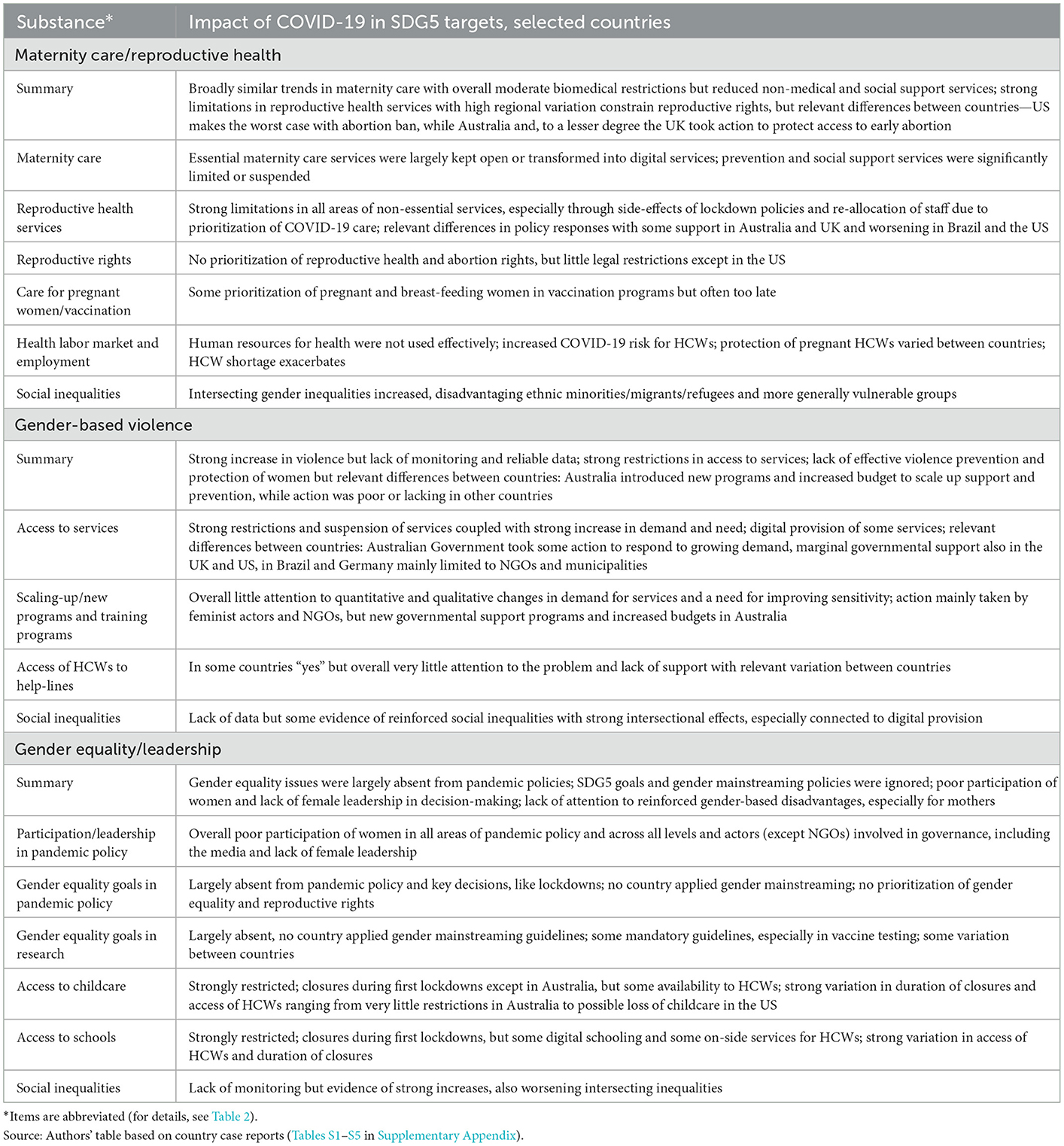

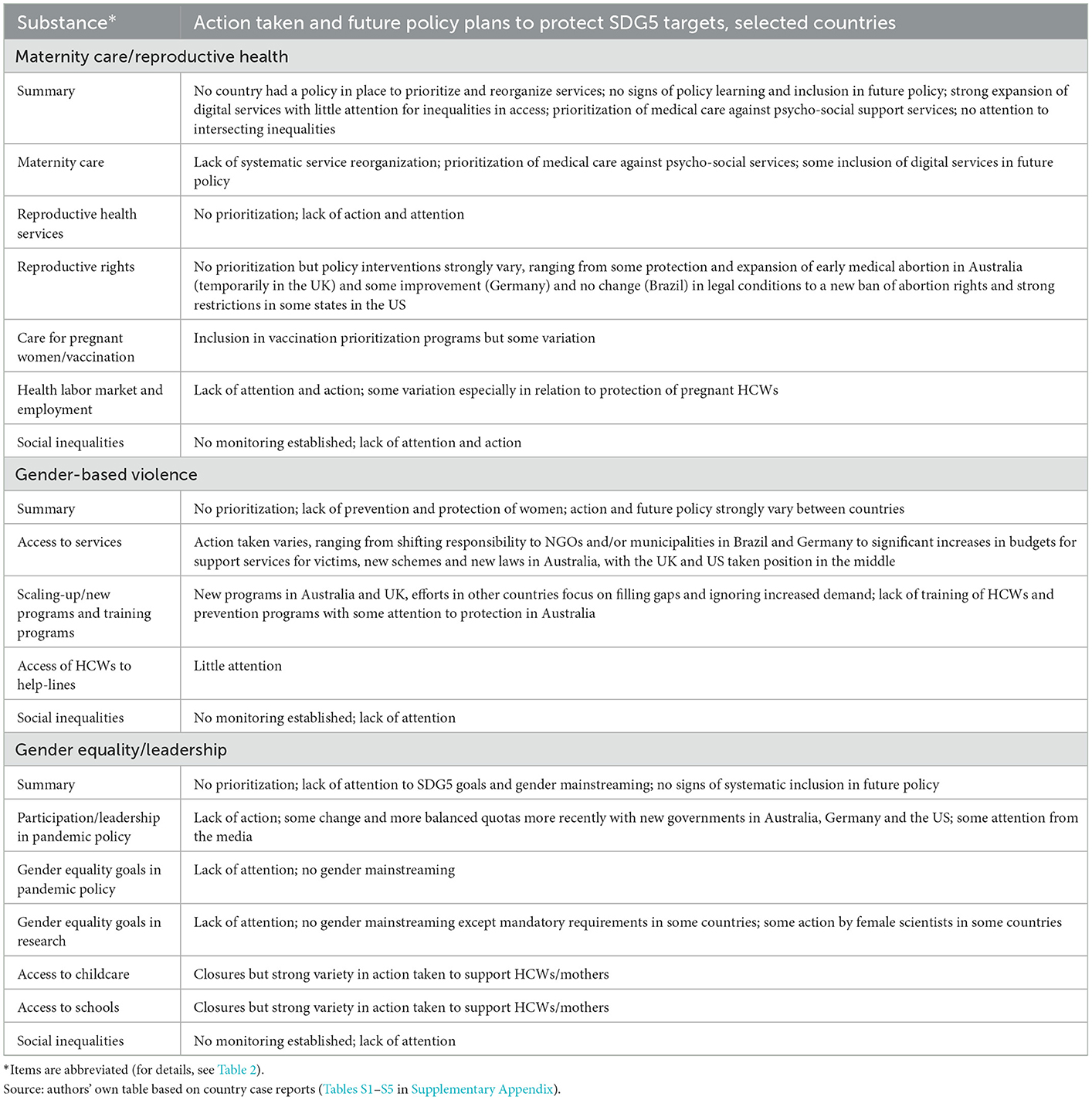

The three thematic areas (substance) served to structure the comparative analysis. Table 3 summarizes the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in our countries, while Table 4 introduces the action taken and future policy. Some illustrative examples taken from the country cases bring “flesh to the bones” of the tables and provide in-depth information, also paying attention to differences between the countries (see for more detailed references, Tables S1–S5 in Supplementary Appendix).

Table 3. Comparing the impact of COVID-19 in key areas of SDG5 targets in five selected upper-middle and high-income countries.

Table 4. Comparing action taken and future policy plans to protect SDG5 targets in times of COVID-19 pandemic in five selected upper-middle and high-income countries.

Provision of maternity care and reproductive health and rights

All countries included in this study made efforts to maintain essential maternity and reproductive services during the pandemic, but with stronger inclusion of digital services (we refer to “digital services” as an umbrella term including all services provided virtually, e.g., telemedicine, eHealth, mHealth, video/telephone hotlines). The new emergent opportunities of digital provision helped to maintain services. Across countries, we found only incremental change with little direct restrictions in essential maternity care services—looking at access without considering quality and accessibility. The impact was much stronger in non-essential services, where we found severe limitations and suspensions that most strongly affected prevention, counseling and all forms of social support services (e.g., visitors, support of partners during birthing) (Tables 3, 4). The situation was more diverse concerning reproductive health and rights. We observed no change in reproductive rights and little impact on essential services (especially abortion) in some countries, but reductions and new abortion bans in others. However, non-essential reproductive health services were significantly restricted in all countries.

Direct policy interventions (such as suspension of services) and lack of attention to women's healthcare needs may combine and create severe threats that pose risks to women's lives. In Brazil, 1,088 maternal deaths were documented in 2020/2021 with a weekly average of 22.2 maternal deaths, indicating an increase of 40% in maternal deaths compared to the previous year. Notably, this increase was much higher than in the general Brazilian population where COVID-19-related deaths caused a 29% increase in mortality (52).

The maternal mortality rate is the most evidence-based indicator of the threats, but it does not show the whole picture. In Germany, for instance, we found no signs of higher death rates and overall little signs of increased medical risks (e.g., slightly higher rates of premature birth and cesarean section rates in 2020). However, the strong limitations in support services and preventative care are likely to cause long-term effects on women's mental health and wellbeing (53). The Australian case shows that prevalence rates of antenatal depression more than doubled or even nearly tripled compared to pre-pandemic rates; an increase was associated with COVID-19 distress of having a baby during a COVID-19 outbreak (54).

Health workforce policy, in particular the situation of midwives, is another issue for consideration. In the US, poor pandemic policy and high COVID-19 infection rates among midwives caused restrictions of services, which were reinforced through cuts in support services (ante- and post-natal) provided by doulas due to restrictions in visits and accompanying partners. In Germany, new COVID-19 administrative requirements and the move to digital services may have reduced services provided by self-employed midwives, who could not afford to pay for additional training and technology. Both cases show that available health workforce capacity is not used effectively to support pregnant women. On the other hand, the case of the UK reveals that pregnant healthcare workers (HCWs) working in the National Health Service (NHS) were poorly protected and exposed to COVID-19 patient care during the first wave; yet legal protection improved and the government introduced mandatory risk assessment for pregnant employees.

Another important issue across countries was the lack of attention to an exacerbation of inequalities. Data are overall poor, but our cases indicate that COVID-19 policies may affect vulnerable groups, migrants and asylum seekers more strongly than others (11, 13, 55). A particular area of concern arises through the replacement of services with digital offerings. For instance, in Brazil, access to virtual maternity care services was more difficult for women who lived in areas without (or with reduced) access to technologies [for international results (56)]. Digitalization may exacerbate inequalities concerning vulnerable groups, if they lack financial resources, infrastructures or skills. Yet there may also be some positive effects, e.g., through improved access to comprehensive evidence-based data and the opportunity to critically review governmental COVID-19 information and policy. No country had adequate policies and programs in place to identify and monitor the complex psycho-social, structural and political dimensions of new digital health services during the pandemic and mitigate intersecting gender inequalities.

Regarding reproductive health, we found strong limitations in non-essential services in all countries. Negative effects appear most severe in the US. Women who experienced shifts in their family planning preferences were sometimes not able to obtain contraception or abortion. These developments strongly impacted women's reproductive rights and have potentially created a policy window for new legislative bans, such as the US Supreme Court decision on abortion (14). The situation was different in other countries included in our assessment. Lockdown policies affected the availability and accessibility of contraception and prevention services but did not change abortion rights. In Australia and the UK, access to early medical abortion even improved during the pandemic through the inclusion of the digital provisions. In Germany, physicians' advertisement of early abortion services was legalized in 2022. This was not directly in response to COVID-19 and other restrictions on abortion and women's rights remained unchanged.

Despite some important differences in reproductive health and rights, we found strong similarities indicating the need for greater attention. First, no healthcare system had a policy in place to prioritize and reorganize services under COVID-19 conditions and there were little if any signs of systematic policy learning and prioritization in future health policy and pandemic recovery plans. Notably, the sustainability of Australian efforts to protect and support early abortion and counseling services in reproductive health is currently not clear. In this situation, changes may happen “sideways” and may be unintended. These intended changes may occur due to limited access during lockdowns, prioritization of COVID-19 services and shortage of healthcare workers. Second, pandemic policies fueled a biomedical approach, while important public health and psycho-social services were significantly weakened or closed due to other priorities. A revival of biomedicalization (the establishment and dominance of commercialized medical offers for natural phenomena) (57) of maternity care and reproductive health services during COVID-19 happened through the backdoor without policy debate and public involvement.

Prevention of gender-based and sexual violence

Prevention of gender-based and sexual violence was strongly affected by pandemic policy and restrictions. At the same time, the need for these services increased dramatically in all countries. We focus on women (and children) who account for the vast majority, but men and non-binary people may also become victims of gender-based violence and in some cases, the offender might be female.

Data are overall poor and no country established an adequate monitoring system that could provide a clearer picture of the impact of COVID-19 and pandemic policies and support gender-responsive pandemic protection policies. Information was mainly drawn from surveys, regional data, or NGO reports. In the UK, for example, two-thirds of General Practitioners (GPs) surveyed before August 2021 said abuse had worsened in the last year due to COVID and exacerbated waiting times. Exact numbers are not available and depend on the data sources, as information from Germany may illustrate (local data, city of Göttingen). According to police data, violence reported to the police offices showed an increase of 9.5% in 2020 and 8.3% in 2021 compared to the previous year. A local feminist emergency service documented a much higher increase: in 2020, 27% more women than in the previous year called for help because of partner violence; 26% more persons called for help because they had observed domestic violence (personal information). In the UK, calls to the Domestic Violence helpline showed a similar figure of a 25% increase (Table S4 in Supplementary Appendix). Data are not directly comparable but show a clear trend and are particularly concerning given domestic violence is typically under-reported.

Under-reporting of all forms of sexual violence and discrimination has long been highlighted by feminist organizations (19). COVID-19 further worsened the situation for several reasons. Women were often not able to call for help because they were living with the offender and lockdowns forced them to stay at home. The COVID-19 disruption also affected the police services and the judicial system that judges cases of violence, as data from the US illustrate: For example, Washington, DC, showed a 43% decrease in patients seeking treatment for sexual assault at one hospital compared to pre-pandemic times; at the same time, women had less access to the legal system and hearings were postponed (Table S5 in Supplementary Appendix). Similar problems were reported in Brazil, where the decrease in reported cases was lower (14% in 2020) (Table S2 in Supplementary Appendix).

Across countries, policies in response to COVID-19 have exacerbated gender-based and sexual violence and limited access to services due to COVID-19 policies. A strong increase in violence (regardless of exact numbers) is a clear indicator of policy failure in all countries. It puts a spotlight on the lack of prevention of violence and protection of women, affecting vulnerable groups the most and exacerbating social inequalities.

There were important differences in the ways governments responded to the problem of domestic violence and the integration of violence prevention into future pandemic plans. In Australia, the Federal Government announced the Coronavirus Domestic Violence Support Package in March 2020 (58). This package provided Australian $150 (AUD) million in funding, with AUD 130 million to be provided to state and territory governments to increase frontline family and domestic violence services through a new National Partnership Agreement on COVID-19 Domestic and Family Violence Responses. There was a particular focus on safer housing and emergency accommodation, counseling and outreach, crisis support and helplines, men's behavior change programs and other perpetrator interventions, assisting frontline services to manage the demand and explore new technology-based services and delivery methods, and responding to unique challenges in regional, rural, and remote locations (58).

Action was also taken by the UK government, which provided £2 million in April 2020 to bolster domestic abuse helplines and online support services. £76 million was pledged in May 2020 to support vulnerable people, of which £25 million was allocated to domestic abuse services (59). In November 2020, the Ministry of Justice provided a further £10.1 million for rape and domestic abuse support, alongside a further £683,000 from the Home Office (60). A public awareness campaign was launched by the government to support survivors of domestic abuse. Another important innovation was the establishment of a scheme in partnership with UK pharmacies called “Ask for ANI” (Action Needed Immediately); this code word helped women who could not talk about the offense (e.g., because they live with the offender/could not go out) (61). Lessons drawn from the pandemic also led to the introduction of the Domestic Abuse Act in April 2021, aiming to protect survivors and better address the behavior of perpetrators (62).

In contrast, in Brazil and Germany (partly also in the US), action was mainly taken by non-state actors and municipalities. Governments showed very little if any efforts to step up prevention services and to provide support for those who experienced violence. The findings indicate that NHS systems might provide better opportunities to integrate services related to gender-based violence compared to the other types included in our assessment, but the case of Brazil illustrates that the type of system does not fully predict the policy response to sexual violence.

Gender equality and women's leadership

SDG5 targets and women's leadership were largely absent from the pandemic debate. No country analyzed here applied gender mainstreaming and equality policies systematically to organize and govern service provision during the COVID-19 pandemic and there was generally no attention to the monitoring of social inequalities. Across countries, we found limited participation of women in decision-making bodies and a lack of women's leadership. For instance, in the UK, no gender advisors were included in the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) in 2020 and 43% of the daily COVID-19 press conferences featured an all-male line-up with no female politician or expert present. Unsurprisingly, gender was not explicitly considered at any point during the government's response. For example, in Brazil the government did not establish any national coordination body during the pandemic and most of the legislation about COVID-19 did not include gender issues. In the US, the White House Coronavirus Task Force contained only two female members of 24 total members.

In Germany, we found that women's voices were marginal in a high-level national think tank. Legally binding guidelines and access of equal opportunity officers to decision-making bodies were ignored when new Corona Task Forces were established at the hospital level. Very few women held leadership positions in relevant academic disciplines; for instance, only 12% of heads of departments in virology are female (63). Female experts were also less visible than their male colleagues in the media. Notably, this happened under a female Chancellor during the first 1.5 years of the pandemic. Exacerbating the marginalization of gender inequality, female experts who raised their voices publicly, often faced hate and strong attacks on social media, and increasingly even physical offenses.

We also observed some signs of growing sensitivity to gender inequalities in the media and/or academia. In Germany, for instance, a small NGO “ProQuoteMedien” developed a list of high-level female COVID-19 experts to increase the visibility of women in public debate. This action was inspired by the 50/50 program introduced by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) in the UK that aimed to achieve a balanced quota of women in the media. Despite some sensitivity—and an increase of women and minorities in government in Australia, Germany and the US—there were little if any signs of more systematic inclusion of gender equality in future policies. However, it might be too early for recent changes to transform the power structures and governance mechanisms.

The second area of assessment were the programs introduced to mitigate women's disadvantages caused by gender-based roles and task distribution, with a focus on women with childcare responsibilities. Data from Australia show that women with children reported spending ~43 more hours per week on childcare during the pandemic than men. Also, women withdrew from higher education at greater rates than men during the pandemic, with 86,000 fewer women enrolled to study in May 2020 than in May 2019, compared with just over 21,000 fewer men (64). In all the cases, we found only little effort to provide meaningful support for them. In the UK, the government decided to suspend the mandatory gender pay reporting for employers (65).

In all countries, childcare facilities and schools faced limitations, especially during the lockdown periods of the first waves of COVID-19 and, in some countries lasting until the end of 2021. These conditions dramatically increased women's responsibility for childcare and affected the employment and career chances of mothers. Their needs were not systematically included in lockdown policies and schooling schemes, but governments responded in different ways. In the UK, childcare facilities and schools were closed except for children of essential workers, including healthcare workers. Germany applied a similar policy but with longer periods of closure and variation between states and providers. The situation was worse in the US, where even healthcare workers sometimes lost childcare support, and in Brazil, where childcare services were closed for 18 months with no support for healthcare workers. In Australia, in contrast, childcare facilities remained open and the government provided free childcare during the first lockdown. Schools experienced periods of interruption with high variation between states and territories but remained open for essential workers and vulnerable families. The examples highlight that governments may either reinforce or mitigate the disadvantageous effects of COVID-19 in women with childcare responsibilities.

Discussion

Our comparative assessment reveals similar trends across different health systems and geopolitical and epidemiological contexts. Pandemic policies strongly cut into women's health and healthcare, but no country has taken action to adequately protect women's health and rights and to strengthen their voices in the policy process.

The United Nations warned us early, that the COVID-19 pandemic puts the limited gains in gender equality and women's rights made over the decades at risk of being rolled back (12). Available data highlighted the social costs of lockdowns, especially the “second pandemic” (66) and “shadow pandemic”: “UNFPA had projected that if lockdowns were to continue for 6 months, 31 million additional gender-based violence cases can be expected, and for every 3 months the lockdown continues, an additional 15 million additional cases of gender-based violence are to be expected” [(20), p. 36]. Feminists across the world, therefore, called to action to protect human rights and the health of women and the UN Secretary-General urged ‘governments to put women and girls at the center of their recovery plans' (67).

However, governments set other priorities. No country prioritized SDG5 goals in the COVID-19 policies and future recovery plans. A global public health emergency response was blind to gender equality and human rights and threatened women's health and social participation on a large scale (1, 12, 13, 15, 20, 68, 69). This holds for countries with male and female political leaders, for different epidemiological scenarios and lockdown policies, and various areas of SDG5 and health. This failure raises important questions not only about the SDGs but also about pandemic policies and recovery plans, including the role of public health institutions (22).

One explanation of these policy failures might be the creation of a discourse of “crisis” as a global narrative, in which epidemiological measures (daily incidence, contract tracing, personal protective equipment, etc.) and medical and system indicators (death rates, hospital beds, respirators, etc.) dominated public debate and societies. The severity of the global COVID-19 crisis and its disruptions opened policy windows to outflank established democratic institutions and public control. Existing “power hubs” in societies were strengthened, such as politics, science and the media that were better equipped for immediate action to define priorities and transform governance procedures. On an institutional level, men usually dominate these power hubs in terms of numbers and hegemonic interests. New bodies and models of management provided a power boost because they may act more easily than established ones “under the radar” of gender equality measures (70). In relation to cultural powers, the making of a biomedical discourse of pandemic risk and protection marched in step with reductionist and positivist approaches in science and healthcare (71). The “neutrality” claims embedded in these approaches made the needs of women, minorities and vulnerable groups invisible and nurtured social inequalities during the pandemic (11, 13, 21, 66).

The reasons for exacerbating gender inequalities during the pandemic are therefore complex, yet a global discourse of “crisis” with its new priorities and powers might explain why we found similar trends across countries with different institutional settings. Discursive governing powers might be strong, regardless of real changes in the institutions, and institutional settings may furnish this discourse with additional power if met with antifeminist politics. Examples are the ban on abortion rights in the US (14) or an increase in maternal mortality rates in Brazil (52). On the other hand, inclusion of reproductive health and violence prevention in public health policy and pandemic responses might counteract these powers to some degree; some efforts were observed in Australia, Germany and the UK (although they were very weak and may not be sustainable). Recent increases in the numbers of women (and minorities) in governments, observed in Australia, Germany and the US, might in the future also weaken a gender-blind crisis discourse, although mere changes in sex ratios do not automatically translate into a change in gender relations.

Limitations

A rapid assessment of time-sensitive ongoing developments and policy action in an under-researched area with poor data sources has several limitations. Firstly, data collection was based on secondary sources and some expert information; primary data were mostly unavailable. Secondly, our qualitative comparative approach focused on exploring problems but does not provide representative data. Thirdly, we did not analyze regional differences and our selection of examples may not provide the full country picture. Fourth, we refer to the intersectionality of gender inequality, but a more detailed analysis of complex social inequalities would go beyond the scope of SDG5 and this research. Our comparative study should be read as a pilot that makes gaps in pandemic policies visible and supports feminist calls for action.

Conclusions

Our assessment highlights a need for gender mainstreaming in COVID-19 policies and recovery plans that should be intersectional to account for the complex social inequalities. A strong connection exists between SDG5 and public health goals. Gender equality, preventative care, mental health and social support services, and the health and wellbeing of healthcare workers were all weakened by the pandemic and structural inequalities exacerbated, while a reductionist biomedical crisis discourse was revamped. Greater attention to governance may help us to further explore these processes and identify windows of opportunity for feminist actors and policy approaches.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

EK and GL had the idea for this study, developed the comparative research framework and wrote a first draft. All authors prepared country case studies (KW and J-LM: Australia, GL and MF: Brazil, EK and LMF: Germany, CW and AH-C: UK, and LP: USA), contributed to the comparative analysis and the revisions, and have read and approved the final version.

Acknowledgments

The idea for this study was inspired by a chapter on SDG5 and SDG3 (EK and GL) for a project on co-benefits for the SDGs (28).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1078008/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table S1. Australia, country case study summary.

Supplementary Table S2. Brazil, country case study summary.

Supplementary Table S3. Germany, country case study summary.

Supplementary Table S4. United Kingdom, country case study summary.

Supplementary Table S5. USA, country case study summary.

References

1. Feminist Response to COVID-19 Collective,. A Feminist Monitoring Advocacy Toolkit for Our Feminist Future. (2022). Available online at: https://www.feministcovidresponse.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Feminist-Response-to-COVID-19-Advocacy-Monitoring-Toolkit-English-2.pdf (accessed October 22, 2022).

2. UN Women,. UN Secretary-General's Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women. UN Women Headquarters (2020). Available online at: https://eca.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/04/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-2 (accessed January 4, 2023).

3. Pan American Health Organisation (PHA). Gendered Health Analysis: COVID-19 in the Americas. (2021). Available online at: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/55432 (accessed January 4, 2023).

4. WHO African Region,. COVID-19 Takes a Heavy Toll on Women's Health. (2022). Available online at: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/congo/news/covid-19-takes-heavy-toll-womens-health (accessed January 4, 2023).

5. International Labour Organisation (ILO). The Gender Pay Gap in the Health and Care Sector: A Global Analysis in the Time of COVID-19. Geneva: ILO (2022). Available online at: https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_850909/lang–en/index.htm (accessed January 4, 2023).

6. European Union,. European Parliament Briefing. The Need for a Gendered Response. (2021). Available online at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/689348/EPRS_BRI(2021)689348_EN.pdf (accessed January 4, 2023).

7. Adams-Prassl A, Boneva T, Golin M, Rauh C. Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: evidence from real time surveys. J Public Econ. (2020) 189:104245. doi: 10.1016/J.JPUBECO.2020.104245

8. Asefa A, Semaan A, Delvaux T, Huysmans E, Galle A, Sacks E, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on the provision of respectful maternity care: findings from a global survey of health workers. Women Birth. (2022) 35:378–86. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.09.003

9. Bambra C, Albani V, Franklin P. COVID-19 and the gender health paradox. Scand J Public Health. (2021) 49:17–26. doi: 10.1177/1403494820975604

10. Lalor J, Ayers S, Celleja Agius J, Downe S, Gouni O, Hartmann K, et al. Balancing restrictions and access to maternity care for women and birthing partners during the COVID-19 pandemic: the psychosocial impact of suboptimal care. BJOG. (2021) 128:1720–25. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16844

11. Lotta G, Fernandez M, Pimenat D, Wenham C. Gender, race and health workers in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. (2021) 397:1264. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00530-4

12. UN Women,. The COVID-19 Shadow Pandemic: Domestic Violence in the World of Work. New York: UN Women (2020). Available online at: https://www.weps.org/resource/covid-19-shadow-pandemic-domestic-violence-world-work-call-action-private-sector (accessed October 22, 2022).

13. Wenham C Smith J Morgan R on on behalf of the Gender and COVID-19 Working Group. COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet. (2020) 395:846–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2

14. New, York Times. Tracking the States Where Abortion is Banned, Update 30 December 2022. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade.html (accessed January 4, 2023).

15. UNFRA. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Planning and Ending Gender-based Violence, Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage. New York: UNFRA (2020). Available online at: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/COVID-19_impact_brief_for_UNFPA_24_April_2020_1.pdf (accessed October 22, 2022).

16. Bojovac N, Stanisljevic J, Giunti G. The impact of COVID-19 on abortion access: insights from the European Union and the United Kingdom. Health Policy. (2021) 125:841–58. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.05.005

17. United Nations (UN). Sustainable Development Goal 5: Achieve Gender Equality Empower All Women Girls. New York: UN (2020). Available online at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal5 (accessed October 22, 2022).

18. EuroHealthNet. Gender Equality Policy and COVID-19. (2021). Available online at: https://eurohealthnet.eu/publication/gender-health-and-inequalities-before-and-after-the-pandemic-where-we-go-from-here/ (accessed October 22, 2022).

19. IDLO—International Organization of Development Law. Justice for Survivors of Gender-Based Violence in Complex Situations: Delivering on the 2030 Agenda for Women and Girls. (2022). Available online at: https://www.idlo.int/news/events/justice-survivors-gender-based-violence-complex-situations-delivering-2030-agenda-women; https://www.idlo.int/sites/default/files/2022/other/documents/survivor-centred_justice_handout-v5.pdf (accessed October 22, 2022).

20. UN Women,. Statement: Reproductive Rights are Women's Rights Human Rights. New York: UN Women (2022). Available online at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/statement/2022/06/statement-reproductive-rights-are-womens-rights-and-human-rights (accessed October 22, 2022).

21. Morgan R, Davies SE, Feng H, Gan CRG, Grepin KA, Harman S, et al. Using gender analysis matrixes to integrate a gender lens into infectious diseases outbreaks research. Health Policy Plan. (2022) 37:935–41. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czab149

22. Tomsick E, Smith J, Wenham C. A gendered content analysis of the World Health Organization's COVID-19 guidance and policies. PLoS Glob Public Health. (2022) 2:e00006490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000640

23. Monti M, Torbica A, Mossialos E, McKee M. A new strategy for health and sustainable development in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. (2021) 398:1019–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01995-4

24. OECD. Building a Resilient Recovery: Emerging Stronger From the COVID-19 Pandemic. Paris: OECD (2020). Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/ (accessed October 22, 2022).

25. Unruh L, Allin S, Marchildon G, Burke S, Barry S, Siersbaek R, et al. A comparison of 2020 health policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States of America. Health Policy. (2022) 126:427–37. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.06.012

26. WHO Regional Office for Europe. The European Health Report. Taking Stock of the Health-Related Sustainable Development Goals in the COVID-19 Era With a Focus on Leaving No One Behind, 2021. Highlights. Copenhagen: WHO (2021). Available online at: 9789289057608-eng.pdf (accessed October 22, 2022).

27. Blank RB, Burau V, Kuhlmann E. Comparative Health Policy, 5th Edition. Basingstoke: Palgrave (2018).

28. Greer SL, Falkenbach M, Wismar M, Figueras J, editors. Health for All Policies: How Investment in Health and Health Systems Contributes to Achieving the SDGs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2023).

29. Gilson L, editor. Health Policy and Systems Research: A Methodology Reader. Geneva: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research/WHO (2012).

30. Greer SL, Rozenblum S, Falkenbach M, Löblová O, Jarmana H, Williams N, et al. Centralizing and decentralizing governance in the COVID-19 pandemic: the politics of credit and blame. Health Policy. (2022) 126:408–17. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.03.004

31. Kuhlmann E, Annandale E. Gender and healthcare policy. In:Kuhlmann E, Blank RH, Bourgeault I, Wendt C, , editors. The Palgrave International Handbook of Healthcare Policy and Governance. Basingstoke: Palgrave (2015). pp. 578–96.

32. Kuhlmann E, Lotta G. SDG 3 Health and SDG 5 Gender Equality: co-benefits and challenges. In:Greer SL, Falkenbach M, Wismar M, Figueras J, , editors. Health for All Policies: How Investment in Health and Health Systems Contributes to Achieving the SDGs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2023).

33. United Nations (UN),. Sustainable Development Goal 3: Ensure Healthy Lives Well-Being for All at All Stages. New York: UN (2020). Available online at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3 (accessed October 22, 2022).

34. Gabster RP, van Daalen K, Dhatt R, Barry M. Challenges for the female academic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. (2020) 395:1968–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31412-4

35. Pan European Commission on Health and Sustainable Development Goals. Copenhagen: WHO (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/europe/groups/pan-european-commission-on-health-and-sustainable-development (accessed October 22, 2022).

36. Forman R, Azzopardi-Muscat N, Kirkby V, Lessof S, Limaro N, Pastorino G, et al. Drawing light from the pandemic: rethinking strategies for health policy and beyond. Health Policy. (2022) 126:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.12.001

38. Burau V, Blank RB, Pavolini E. Typologies of healthcare systems. In:Kuhlmann E, Bank RB, Bourgeault IB, Wendt C, , editors. International Handbook of Healthcare Policy and Governance. Basingstoke: Palgrave (2015). p. 101–15.

39. Oppenheimer B, Gallivan M, Madhav NK, Brown N, Serhiyenko V, Wolfe ND, et al. Assessing global preparedness for the next pandemic: development and application of an Epidemic Preparedness Index. BMJ Global Health. (2019) 4:e001157. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001157 mic

40. United, Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). World Population Dashboard, Total Population in Millions, 2022. Available online at: https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population-dashboard (accessed October 22, 2022).

41. OECD. Data, Gross Domestic Product (GDP). (2022). Available online at: https://data.oecd.org/gdp/gross-domestic-product-gdp.htm (accessed October 22, 2022).

42. OECD. Health Statistics. (2022). Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm (accessed October 22, 2022).

43. United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Gender Inequality Index (GII). (2022). Available online at: https://www.hdr.undp.org/en/content/gender-inequality-index-gii (accessed October 22, 2022).

44. World Bank. Proportion of Seats Held by Women in National Parliaments%. (2023). Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SG.GEN.PARL.ZS (accessed January 4, 2023).

45. Maternal Mortality Ratio (2017). Available online at: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/maternal-and-reproductive-health/maternal-mortality-country-profiles (accessed October 22, 2022).

46. Global Gender Gap Index (2022). Available online at: https://www.statistica.com/ (accessed October 22, 2022).

47. Our World in Data. Coronavirus Pandemic, Country Profiles. Available online at: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus#coronavirus-country-profiles (accessed January 4, 2023).

48. Our World in Data. Coronavirus Death. Available online at: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-deaths (accessed January 4, 2023).

49. Our World in Data. COVID-19 Vaccination. Available online at: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (accessed January 4, 2023).

50. Johns Hopkins University. Coronavirus Resource Centre, Australia. Available online at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/region/australia (accessed January 4, 2023).

51. Wrede S, Benoit C, Bourgeault IL, van Teijlingen E, Sandall J, de Vries R. Decentred comparative research: context sensitive analysis of maternal health care. Soc Sci Med. (2006) 63:2986–97. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.011

52. Diniz D, Brito L, Rondon G. Maternal mortality and the lack of women-centred care in Brazil during COVID-19: preliminary findings of a qualitative study. Lancet Reg Health Am. (2022) 10:100239. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100239

53. Schmiedhofer M, Derksen C, Dietl JE, Häussler F, Louwen F, Hüner B, et al. Birthing under the condition of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: interviews with mothers, partners, and obstetric health care workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:1486. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031486

54. Frankham LJ, Thorsteinsson EB, Bartik W. Antenatal depression and the experiences of Australian women in the maternity system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Open J Depress. (2021) 10:155–67. doi: 10.4236/ojd.2021.104010

55. Engelhardt M, Krautstengel A, Patzelt L, Gaudion M, Kamhiye J, Borde T. Auswirkungen der COVID-19 Pandemie auf die Versorgungssituation von geflüchteten Frauen während Schwangerschaft und Geburt. Z Geburtshilfe Neonat. (2021) 225:P141. doi: 10.1055/S-0041-1739903

56. Galle A, Semaan A, Huysmans E, Audet C, Asefa A, Delvaux T, et al. A double-edged sword–telemedicine for maternal care during COVID-19: findings from a global mixed-methods study of healthcare providers. BMJ Glob Health. (2021) 6:e004575. doi: 10.1136/BMJGH-2020-004575

57. Christiaens W, van Teijlingen E. The four meanings of medicalization: childbirth as a case study. Salute Soc. (2009) 8:123–41. doi: 10.3280/SES2009-EN2009

58. Parliament of Australia. Family Violence in Australia and the National Plan. Canberra (2020). Available online at: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Social_Policy_and_Legal_Affairs/Familyviolence/Report/section?id=committees%2Freportrep%2F024577%2F75208 (accessed October 22, 2022).

59. UK Parliament,. Domestic Abuse COVID-19: A Year into the Pandemic. (2021). Available online at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/domestic-abuse-and-covid-19-a-year-into-the-pandemic/ (accessed January 4, 2023).

60. UK Government,. Press Release. Funding Boost for Rape Domestic Abuse Support. (2020). London: GOV.UK. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/funding-boost-for-rape-and-domestic-abuse-support (accessed January 4, 2023).

61. UK Government. Pharmacies Launch Codeword Scheme to Offer ‘Lifeline' to Domestic Abuse Victims. (2021). London: GOV.UK. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pharmacies-launch-codeword-scheme-to-offer-lifeline-to-domestic-abuse-victims (accessed October 20, 2022).

62. UK Government. Domestic Abuse Act 2021: Overarching Factsheet. (2022). London: GOV.UK. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/domestic-abuse-bill-2020-factsheets/domestic-abuse-bill-2020-overarching-factsheet (accessed January 4, 2023).

64. Zhou N. Female enrolment at Australian universities dropped by 86,000 in 2020 as ‘pink recession' hit. The Guardian. (2020). Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/nov/12/female-enrolment-at-australian-universities-dropped-by-86000-in-2020-as-pink-recession-hit (accessed October 22, 2022).

65. Government Equalities Office,. Employers Do Not Have to Report Gender Pay Gaps. (2020). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/employers-do-not-have-to-report-gender-pay-gaps#:~:text=Due%20to%20the%20COVID%2D19,year%20(2019%20to%202020) (accessed January 4, 2023).

66. Fiske A, Galasso I, Eichinger J, McLennan S, Radhuber I, Zimmermann B, et al. The second pandemic: examining structural inequalities through reverberation of COVID-19 in Europe. Soc Sci Med. (2022) 292:114634. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021

67. United Nations (UN). Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 5: Response to COVID-19. New York: UN (2020). Available only at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ (accessed 22 October, 2022).

68. Flor LS, Friedman J, Spencer CN, Cagney J, Arrieta A, Herbert ME. Quantifying the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender equality on health, social and economic indicators. Lancet. (2022) 399:2381–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00008-3

69. Smith J, Davies SA, Feng H, Gan CCR, Grepin KA, Harman S. More than a public health crisis: a feminist political economic analysis of COVID-19. Global Public Health. (2021). 16:8–9. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1896765

70. Kuhlmann E, Ovseiko P, Kurmeyer C, Gutiérrez-Lobos K, Steinböck S, von Knorring M, et al. Closing the gender leadership gap: a multi-centre cross-country comparison of women in management and leadership in academic health centres in the European Union. Hum Resour Health. (2017) 15:2. doi: 10.1186/s12960-016-0175-y

Keywords: SDG5 gender equality, COVID-19 pandemic, health systems and policy, international comparison, upper-middle and high-income countries

Citation: Kuhlmann E, Lotta G, Fernandez M, Herten-Crabb A, Mac Fehr L, Maple J-L, Paina L, Wenham C and Willis K (2023) SDG5 “Gender Equality” and the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid assessment of health system responses in selected upper-middle and high-income countries. Front. Public Health 11:1078008. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1078008

Received: 23 October 2022; Accepted: 19 January 2023;

Published: 03 February 2023.

Edited by:

Jonathan Ling, University of Sunderland, United KingdomReviewed by:

Sofia Ribeiro, University of Lisbon, PortugalZuzana Kotherová, Charles University, Czechia

Lara Maestripieri, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Kuhlmann, Lotta, Fernandez, Herten-Crabb, Mac Fehr, Maple, Paina, Wenham and Willis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ellen Kuhlmann,  a3VobG1hbm4uZWxsZW5AbWgtaGFubm92ZXIuZGU=

a3VobG1hbm4uZWxsZW5AbWgtaGFubm92ZXIuZGU=

†These authors share first authorship

Ellen Kuhlmann

Ellen Kuhlmann Gabriela Lotta2,3†

Gabriela Lotta2,3† Michelle Fernandez

Michelle Fernandez Jaimie-Lee Maple

Jaimie-Lee Maple Ligia Paina

Ligia Paina Karen Willis

Karen Willis