95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 21 March 2023

Sec. Public Health Education and Promotion

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1007328

This article is part of the Research Topic Understanding, Assessing, and Guiding Adaptations in Public Health and Health Systems Interventions: Current and Future Directions View all 23 articles

Introduction: Cultural factors are constructs that capture important life experiences of Latinx/Hispanic individuals, families, and communities. Despite their importance for Latinx communities, Latinx cultural factors have yet to be fully incorporated into the literature of many social, behavioral science, and health service fields, including implementation science. This significant gap in the literature has limited in-depth assessments and a more complete understanding of the cultural life experiences of diverse Latinx community residents. This gap has also stifled the cultural adaptation, dissemination, and implementation of evidence based interventions (EBIs). Addressing this gap can inform the design, dissemination, adoption, implementation, and sustainability of EBIs developed to serve Latinx and other ethnocultural groups.

Methods: Based on a prior Framework Synthesis systematic review of Latinx stress-coping research for the years 2000–2020, our research team conducted a thematic analysis to identify salient Latinx cultural factors in this research field. This thematic analysis examined the Discussion sections of 60 quality empirical journal articles previously included into this prior Framework Synthesis literature review. In Part 1, our team conducted an exploratory analysis of potential Latinx cultural factors mentioned in these Discussion sections. In Part 2 we conducted a confirmatory analysis using NVivo 12 for a rigorous confirmatory thematic analysis.

Results: This procedure identified 13 salient Latinx cultural factors mentioned frequently in quality empirical research within the field of Latinx stress-coping research during the years 2000–2020.

Discussion: We defined and examined how these salient Latinx cultural factors can be incorporated into intervention implementation strategies and can be expanded to facilitate EBI implementation within diverse Latinx community settings.

The cultural adaptation of evidence-based interventions (EBIs) is now recognized as an important procedure for the effective dissemination and implementation of EBIs that are culturally relevant and acceptable within many Latinx/Hispanic1 communities (1). The Latinx population in the US is the largest racial/ethnic population in the nation, with an estimated population in 2021 of 61.3 million, which constitutes 18.9 percent of the total US population of 326.195 million (2).

Cultural adaptations can increase an intervention's capacity to engage participants, also potentially increasing the intervention's effectiveness. Over the past decade, the cultural adaptation of EBIs has been recognized as essential for effective EBI dissemination and implementation within diverse ethnocultural communities (3, 4). Unfortunately, implementation strategies have been almost non-existent that utilize cultural factors to inform the design, dissemination, adoption, implementation, adaptation, and sustainability of EBIs for effective delivery with residents from diverse ethnocultural communities (5, 6). This paper discusses approaches in the cultural adaptation of EBIs that can be enhanced by the utilization of cultural factors. A long-term goal of these cultural adaptations is to implement these strategies toward attaining health equity outcomes within various Latinx communities (7).

The Fidelity-Adaptation Dilemma emerged in the early 2000's. It juxtaposes two perspectives about the delivery of evidence-based interventions. One argument focused on EBI implementation with high fidelity for maintaining its effectiveness in changing targeted intervention outcomes (8). A concern with EBI adaptations was that making intervention changes could erode the intervention's effectiveness. A competing argument was a recognition of the need to make necessary EBI adaptations in response to significant problems encountered in EBI implementation (9). Framed as an either-or proposition, this debate highlighted controversies and consequences of taking one course of action over the other (10). The approach of identifying a “balance,” point among both alternatives emerged as a possible solution, although ultimately it was unsatisfactory for resolving this dilemma.

After two decades of this controversy, the view emerged that fidelity and adaptation are equally important. This reframing introduced a more nuanced yet more effective approach for advancing beyond this original “either-or” dichotomy into a more inclusive “both-and” strategy (5, 10, 11). Specifically, defining adaptations as additions to intervention content or structure, rather than simply a lack of fidelity, helped to define which adaptations may be advantageous in promoting cultural fit and in enhancing intervention effectiveness (12, 13).

Reference to “cultural factors” and to “cultural variables” emerged in the early 1970s in an article in 1973 by social psychologists Triandis, Malpass, and Davidson that connected psychology with culture (14). In the 1990s and into the year 2000, Latinx investigators indicated that certain cultural constructs (cultural concepts, cultural variables, cultural factors) captured important cultural experiences in the daily lives of many Latinos and Latinas in the US (15, 16). This led to conceptualizing and creating new scales that provided reliable and valid measures of these important cultural constructs. In the drug and alcohol research field, cultural factors believed to capture important life experiences among ethnocultural communities included: (a) acculturation experiences; (b) aspects of stress, coping, and social support; and (c) cultural beliefs and attitudes about drug and alcohol use and misuse (16). Incorporating cultural factors into regression models advanced our understanding of how cultural factors such as acculturation stress could influence alcohol and drug use, and how racial and ethnic values, gender norms, and other cultural variables could operate as moderators or mediators of drug and alcohol use and misuse among various Latinx/Hispanic communities (17).

In 1995, Cuellar and colleagues examined what they called cognitive referents of acculturation. They regarded these cultural referents as important constructs for understanding the role of culture among persons of Mexican heritage (18). Constructs that Cuellar and collaborators examined were: familism (familismo), fatalism, machismo, personalismo, and folk beliefs. Those investigators measured these constructs with new scales which they developed that had sound psychometric properties. In their psychometric analyses, Cuellar and colleagues found that each of these constructs, except personalismo, were negatively correlated with levels of acculturation to the US society as measured with a unidimensional scale of the acculturation construct. This indicated that these four constructs were more strongly endorsed by Mexican Americans of lower acculturation status, that is, persons most actively endorsing and practicing in their daily lives Mexican cultural beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and other sociocultural activities. Generally these cultural practices have often been associated with beneficial outcomes (e.g., fewer internalizing and externalizing symptoms, lower rates of alcohol use, and improved academic self-efficacy and achievement), when examined in longitudinal research with Mexican American adolescents (19–21).

Many definitions of “culture” describe three of its core aspects (22). First, culture consists of a cognitive schema or “world view,” shared by a social group and that it is distinct from that of another social group. This schema has also been described as a “subjective culture,” which is, “a cultural group's characteristic way of perceiving its social environment,” and consists of, “attitudes, norms, roles, values, expectancies, and other constructs” [(14), p. 359]. Second, culture consists of well-established community focused normative beliefs and behaviors accepted and practiced by members of that social group. Third, this cultural schema is transmitted across generations from elders to youth, so that the norms that define that culture persist across time (22). Implicit and explicit strategies for transmitting these cultural values from parents to children are referred to as ethnic socialization, which has been demonstrated to promote multiple positive outcomes among Latinx youth, particularly in the face of discrimination (20). Beyond ethnocultural groups, diverse entities including organizations, also develop social norms, spoken or unspoken, that operate as standards of conduct that govern organizational beliefs and behaviors (22).

In 1991 the National Institute on Drug Abuse identified 13 principles of effective drug abuse treatment (23). However, among these 13 principles, none mentioned or alluded to culture or cultural factors as important for effective drug abuse treatment of ethnocultural clients or patients. Similarly, in the field of implementation science, the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project introduced 73 strategic recommendations to guide approaches for intervention dissemination and implementation (24). Here also, none of these strategic recommendations mentions or alludes to the utilization of culture or cultural factors in the delivery of EBIs. Given this absence of cultural factors in research, Ramirez Garcia (25) emphasized that a major gap exists in several research fields. This includes the field of dissemination and implementation research.

Traditional cultural factors, the classic cultural factors often mentioned in prior Latinx social and behavioral science research literature include: (a) familismo, Latino family closeness and cohesion; (b) machismo, traditional Latinx male identity characteristics, both positive and negative; (c) personalismo, the importance of warm interpersonal relations; (d) respeto, respectful exchanges in interpersonal relations; and (e) simpatia, a deferential interpersonal style that strives to maintain harmony in interpersonal relations (6, 26) (see Table 1). Cultural factors also include constructs that describe the process of cultural change among immigrants and others during the process of acculturation (27). These include experiences of discrimination (20, 28).

Table 1 presents important cultural factors mentioned as pan-cultural (multiethnic), and those that are specific to Latinx communities. Castro and Kessler describe other cultural factors of importance within major ethnocultural communities in the US: African American/Black, Asian American and Pacific Islander, Native American/American Indian, and other ethnocultural groups (6).

In summary, despite prior research on cultural factors as constructs that capture the deep structure cultural experiences of Latinx communities, these major cultural constructs have seldom been utilized to guide EBI development and strategic planning in EBI dissemination and implementation. Accordingly, the need exists for guidelines and strategies for incorporating cultural factors into EBI design, dissemination and implementation for delivery with Latinx and other ethnocultural groups in the US: Blacks/African Americans, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans/American Indians and Alaska Natives.

Mixed methods research focuses on the integration of qualitative and quantitative data for producing a greater “yield” of information generated from a deep structure analysis that utilizes mixed methods approaches (29), and can yield more comprehensive answers to overarching research questions.

Qualitative data can yield contextual descriptions of complex “real world” situations. This context can inform the development of culturally-relevant EBI adaptations (4), and inform complex process analyses about effective implementation strategies. Typically, qualitative data consist of verbal responses to open ended questions often obtained from individual interviews or focus groups. These rich, complex, nuanced, and informative text narratives can inform the design of culturally relevant EBIs (30). These data include qualitative descriptive observations of interactions or environmental processes, such as socialization practices for teaching children how to respond to discrimination (31). Furthermore, such observational data also includes the identification of an EBI's problematic content or processes that can be rectified with cultural adaptations (32).

Typically, quantitative data are obtained from surveys and questionnaires that capture data using numeric ratings and scales. Generated quantitative (numeric) data, i.e., measured variables allow the analysis of correlations between a scaled (measured) cultural factor and numerically transformed data, i.e., thematic variables (33). Data analyses that examine associations among measured variables and thematic variables can be conducted using multiple regression model analyses. In summary, whereas qualitative data are useful for conducting in-depth, often exploratory data analyses, quantitative data are useful for conducting confirmatory analyses that allow hypothesis testing, and testing a variety of models.

The hallmark of mixed methods approaches is the purposeful integration of qualitative (QUAL) and (QUAN) quantitative data, to generate greater yield (explanatory output) from the analysis of these integrated datasets. In these analyses, cultural factors often can be modeled as potential effect modifiers, that is, as moderator variables, that may change the effects of a predictor variable on an outcome variable (34). Mixed methods research typically adopts a pragmatic approach that is initiated with an overarching research question, followed by the planful utilization of mixed methods procedures to yield a more complete answer to that overarching research question (29).

Palinkas and collaborators identified five major reasons for using mixed methods designs in intervention research that focuses on dissemination and implementation issues (35). These reasons include: (a) using quantitative methods to measure intervention and/or implementation outcomes, and qualitative methods to understand process; (b) conducting both exploratory and confirmatory research; (c) examining both intervention content and context; (d) examining consumers' perspectives about the effects of an EBI or other clinical practices, e.g., the views of practitioners and clients; and (e) the capacity to compensate for one type of data analytic method by using another type of data analytic method.

Mixed methods can inform the “unpacking” of complex, multidimensional constructs, including several cultural factors. A mixed methods convergent design can be used to conduct thematic analyses to reveal underlying dimensions (themes) that define facets of a cultural construct, such as traditionalism (36). After conducting a thematic analysis, and utilizing Scale Coding (33), investigators can examine associations among the construct's emerging themes.

Using Scale Coding, an identified thematic category (scored 1 = present in a case, and 0 = not present) can be transformed into numeric form, i.e., into a thematic variable (33), which affords the ability to create a mixed methods correlations matrix to examine select correlations among measured variables and transformed thematic variables (33, 36). Then, re-contextualization involves a return to the analysis of select qualitative text narratives from cases identified by significant correlations within a mixed methods matrix.

In summary, cultural factors can be utilized to inform implementation strategies that can improve EBI implementation among low resource and ethnocultural communities. The incorporation of cultural factors in the cultural adaptation of an original EBI is an important strategy for promoting health equity (37, 38) among diverse communities of color. Cultural adaptation is an important approach that can contribute to increasing the relevance of implementation science for improving the transfer of science to practice for delivery among diverse ethnocultural communities. This approach can build on the rich array of theories, models and frameworks developed under the auspices of implementation science (39). These theories, models, and frameworks (TMFs), constitute organized approaches for guiding adaptation planning (40). Many of these TMFs have undergone revisions to support a health equity focus (41). This provides opportunities for incorporating cultural factors into EBIs to increase the EBI's cultural relevance toward producing effective outcomes when delivered with diverse Latinx community residents.

Across time, dissemination and implementation (D&I) science has brought greater attention to implementation context and strategies (42) in which cultural factors can operate as contextual factors, often as moderator variables, of effect modifying conditions. One D&I model that describes the influences of contextual factors is the Practical Robust Implementation Sustainability Model (PRISM) (43). This model can inform various approaches in implementation planning.

Regarding ways to conduct EBI adaptations, experts in the D&I field have recommended the need to document details of the adaptation process as conducted during the process of an EBI's implementation. This documentation consists of clearly describing additions, deletions, and other necessary modifications (42, 44). This careful documentation can inform future implementation protocols as well as generating empirical evidence to refine and expand these TMFs. A methodology for documenting and tracking adaptations to EBIs is the FRAME. Wiltsey Stirman et al. (13) recently expanded the FRAME for more precise documentation and tracking of adaptations and modifications to an original EBI's implementation strategies.

In a prior study, Castro et al. (45) conducted a Framework Synthesis Review (46) of the Latinx/Hispanic stress literature for the years 2000–2020. The Framework Synthesis approach utilizes an initial model that is informed and expanded by results from the subsequent framework synthesis review of the literature. The purpose of that prior study was to review two decades of Latinx stress-coping research to inform the development of an expanded and culturally relevant Stress-Coping-Outcomes Model. Our team of four research investigators consisted of two senior research investigators (FC and RC) and two early career investigators (DS and CD).

In that Framework Synthesis Review, we conducted a conventional PRISMA literature review protocol consisting of four steps: (a) identification, (b) screening, (c) quality assessment, and (d) inclusion (45). We used PsycInfo and Medline as search engines to identify empirical Latinx stress-coping research studies conducted from the years 2000 to 2020. From this article screening and analysis, our team identified 50 articles from high-impact journals, those having an Impact Factor of 1.5 or higher, for possible inclusion into this systematic review. In this selection process our quality assessment of candidate articles consisted of two quality assessment criteria: (a) Stress Model Relevance—the requirement that the empirical article examined and described in detail one or more stress-coping model constructs or factors, and (b) Latinx Cultural Relevance—that the empirical article utilized a Latinx theoretical framework on culture that examines and describes in detail major cultural aspects of Latinx cultures. For thoroughness in coverage, we conducted an additional screening of select competitive articles from low-impact factor journals. We reviewed these articles using the same review protocol used in our original rigorous screening process. In this manner and based on the review and analysis of 16 candidate articles, our coding team of four investigators included 10 articles that passed our noted two-factor quality assessment.

Our team of four investigators conducted an exploratory identification of Latinx cultural factors from the Discussion section from each of these 60 empirical journal articles from the field of Latinx stress-coping research. We focused on Discussion sections of these included journal articles (n = 60), since Discussion sections typically provide an analysis and interpretation of the empirical study's research outcomes, at times mentioning relevant Latinx cultural factors. Each of our four investigators screened 15 articles from among these 60, to identify candidate cultural factors. We utilized a Cultural Factor Extraction Form that our team developed. We then created a Word file of the text narrative of each journal article's Discussion section, and each investigator utilized the Word software program's highlight function to mark a relevant text narrative, typically one to two sentences containing a candidate cultural factor. In follow-up Zoom meetings, we conducted a Roundtable Discussion (33) to consider each candidate cultural factor and included it in this screening analysis if endorsed by all investigators thus reaching consensus on its inclusion.

Results of these analyses were entered into a Cultural Factor Listing. From this process we identified 58 constructs/cultural factors. Each of these was “tagged” with the originating journal article's identifier ID number. Under a hierarchical structure, we identified 10 “word stems” as the superordinate term (core construct) that formed the basis of related sub-terms (sub-constructs). For example, the word stem of “acculturation” served as the core construct for the related sub-terms: “acculturation gap,” “acculturation process,” “acculturative stress” and “level of acculturation” (see Table 2).

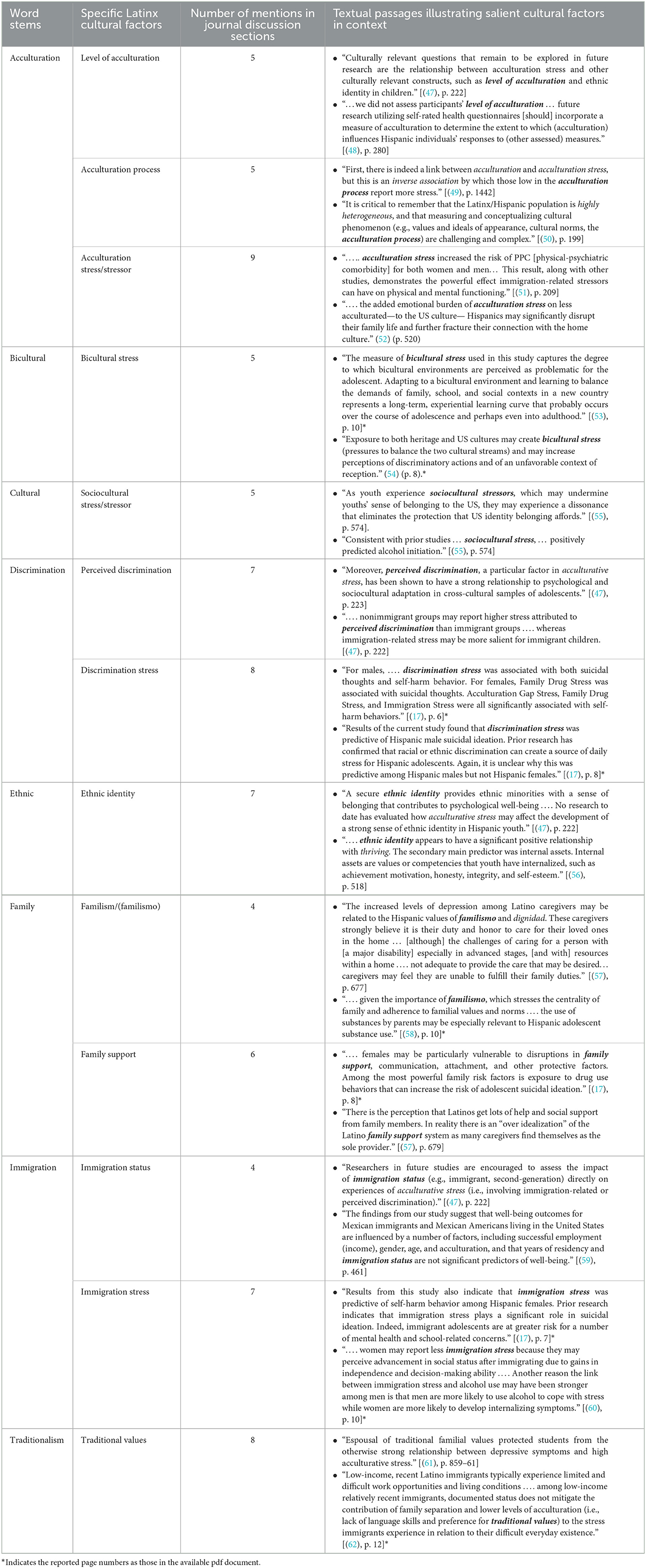

Table 2. Empirically identified cultural factors in Latinx stress-coping-outcomes literature: years 2000–2020.

Theme identification has been described as, “One of the most fundamental tasks of qualitative research” [(63), p. 85]. The identification of themes has also been described as a key step in unpacking the factorially complex construct of “culture.” Based on our Part 1 exploratory analyses we utilized NVivo 12 Pro to conduct a rigorous confirmatory thematic analysis to identify salient Latinx cultural factors using our original 10 word stems (i.e., acculturation, bicultural, caregiver, cultural, discrimination, ethnic, family, identity, immigration, and traditionalism).

As examined across textual contents in the 60 Discussion sections we conducted a textual search of candidate cultural factors identified in our exploratory analyses, also indicating their frequency of mention (occurrence). We scanned these Discussion sections using a Key-Word-in-Context (KWIC) procedure to identify salient Latinx cultural factors from the Latinx stress-coping literature across the years 2000–2020. In this casewise analysis of these Discussion sections, we regarded each journal's discussion section as an independent observation. Here, the unit of analysis, the “case,” was the journal article based on our text review of its Discussion section. Finally, we defined the occurrence of a theme as the mention (occurrence) of a given cultural factor in four of these journals, thus constituting a “logical thread” that was mentioned across four or more of these independent journal observations (63). In summary, in this confirmatory analysis, we utilized the NVivo 12 Word Search Wizard to scan each journal article's Discussion section to detect the occurrences (mentions) of each of our candidate cultural factors, to identify the cultural factors mentioned across independent observations, i.e., journals, also indicating their frequency of mention. The cut-point of at least four mentions across different journals was used to identify the occurrence of a theme, which indicates the salience of that candidate cultural factor. The identification of that salient Latinx cultural factor constitutes a logical thread occurring across two decades within the Latinx stress-coping literature.

As noted, we conducted a rigorous approach to confirm the prior exploratory analysis of cultural factors. We used the NVivo 12 software program to conduct a Key-Word-in-Context (KWIC). In this analysis we identified 13 themes that constitute salient Latinx cultural factors appearing in the Latinx stress-coping research literature for the years 2000–2020 (see Table 2).

Table 2 presents these 13 specific Latinx cultural factors (see column 2). Eight of the our original 10 stem terms, i.e. “acculturation,” “bicultural” etc., are presented in column 1, as the stem terms were used to identify these Latinx cultural factors. These eight stem terms revealed a total of 13 specific Latinx cultural factors, which could be defined as salient Latinx cultural factors (see Table 2, column 2). Presented in column 3 is the number of different journal articles mentioning cultural factors in their Discussion section. Finally, column 4 presents illustrative textual passages from relevant journal article sections that illustrate in context the application of each salient Latinx cultural factor in the research study in which this factor appeared. Here we include two passages for a broader illustrative context.

From the broader construct of acculturation, three related salient Latinx cultural factors emerged: “level of acculturation,” “acculturation process,” and “acculturation stress/stressors.” Relevant contextual quotations included in column 4 provide meaning and context for understanding and assessing various aspects of acculturation among diverse Latinx communities. The heterogeneity of the Latinx/Hispanic population is also indicated, suggesting the utility of conducting in-depth analyses with distinct Latinx population sectors by level of acculturation (low acculturation, bicultural, high acculturation).

The construct of bicultural stress refers to the daily experiences of US-born and immigrant Latinx individuals who often struggle to succeed within two distinct cultural environments, i.e., the American and Latinx cultures. These passages reveal that efforts at adaptation to a new culture or setting are often stressful, resulting from exposures to conflicting sociocultural stressors, including discrimination, and structural barriers to social and economic mobility (53).

External events (stressors) and the tension they produce (stress) can produce acute and chronic distress followed by mild-to-severe psychological symptoms that can develop into diagnosable psychiatric disorders such as Anxiety and Depressive Disorders, as well as the Drug and Alcohol Abuse Disorders (51, 64).

Discrimination is often a stressful experience for Latinos and Latinas, when experienced at any of several developmental stages of life. Certain Latinx groups often experience greater exposure to discrimination based on their acculturation status and features of their personal identity. These situations can impede normal youth development and identity formation. Among some Latinx individuals, discrimination may lead to suicidal ideation and other forms of self-harm (17).

Developing a strong and secure ethnic, gender, and other forms of personal identity can contribute to a sense of belonging and well-being. Some research reports a positive association between ethnic identity formation and thriving (51, 56).

A strong sense of familism (familismo) is often regarded as a personal asset. The context in which familism and family social supports occur often influences a youth's family identification, belongingness, and sense of well-being. However, among some Latinx caretakers of a disabled family member, Latinx family values involving familismo and dignidad (dignity), coupled with insufficient resources, can produce stressful family conflicts. Substance use by some caretakers to cope with the stressors of caretaking may prompt substance use among adolescent members of the family (58). While familismo is prevalent among many Latinx families, this broad view has been questioned, referring to familismo as an “over idealization” (57). This can occur among some Latinx caretakers for whom traditional Latinx family expectations and ascribed caretaker roles create burdens for a single family member who is expected to serve as the sole family caretaker (57).

Research shows that in coming to the US some Latinas and young adults gain social status, independence, and decision-making abilities, which may empower them for adapting effectively within the US culture (60). Stress experiences among Latinx individuals can vary in relation to gender and to immigration status. Various gender patterns have emerged involving alcohol use among immigrant Latinas in response to multiple sociocultural stressors. Among some Latinx adolescents, immigration stress can prompt suicidal ideation particularly among adolescent Latinas (females) (17).

Among Latinx young adults, in some families traditional Latinx family values involving strict parental expectations encourage adult children to remain close to the family and to adhere to restrictive traditional family rules (61). Conversely, traditional Latinx family values in everyday life can also exert a positive effect on a family members' health and well-being. Within this context, the intersectionality of traditional family values with gender, low level of acculturation, immigrant status, and other sociocultural variables can exert complex beneficial and adverse influences on a family member's health and well-being (62).

In comparing the classic Latinx cultural factors presented in Table 1, with the empirically identified Latinx cultural factors in Table 2, some concordance appears in the joint identification of four cultural factors: acculturation, acculturation stress, familismo, and traditionalism (traditional family values). By contrast, other empirically identified cultural factors involve various specific types of stress: bicultural stress, sociocultural stress, discrimination stress, and immigration stress. Future studies that examine other areas of research such as family systems research may reveal the salience of several of the traditional Latinx cultural factors which include: familismo, machismo, personalismo, respeto, and simpatia. Those analyses may identify other important Latinx cultural factors that capture other deeply rooted and important aspects of Latinx cultures.

There is a growing recognition of the importance of collaborative partnerships between researchers and community-based organizations to inform the development and enhance the implementation of culturally responsive EBIs. Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approaches (65) are now regarded as essential procedures for EBI adoption, adaptations, dissemination, and implementation.

A study by Orengo-Aguayo et al. established a university-community partnership for the dissemination and implementation of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy (TF-CBT) for delivery in three low-resource settings. These interventions and settings were: (a) the delivery of telehealth in a rural community in South Carolina, (b) the delivery of this TF-CBT in the island of Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, and (c) building the local infrastructure and workforce for delivering the TF-CBT within impoverished war-ravaged communities within the country of El Salvador (66).

This international translation study that was conducted in El Salvador featured the traditional Latinx cultural factor of personalismo, a relational style that emphasizes “personal attention and courtesy in interpersonal relations” (15, 18) (see Table 1). Applying personalismo involves relationship building for engaging in intervention activities that facilitate open discussions and mutual collaborations. Among traditional Latinx communities, the act of social engagement observes a Latinx-Hispanic cultural norm and expectation of personalismo in customary actions that should precede collaboration in a collective activity.

These investigators recognized the value of using an implementation framework, such as the EPIS (67), while also asserting that these frameworks can be, “extremely limited in terms of contextual adaptabilities” [(66), p. 1172]. These investigators emphasized that D&I research investigators must listen to local community stakeholders to truly hear their concerns. They also asserted that such listening can inform the development and implementation of, “sweeping solutions to many of the biggest challenges currently facing dissemination and implementation science within low-resource settings” [(66), p. 1172].

In a study by Hirchak and collaborators, university investigators in the Southwestern United States established a strong partnership with a large American Indian/Native American community (68). This Tribal-University Partnership fostered community engagement activities during the pre-implementation stage by engaging in active partnerships with residents from this indigenous community. This pilot study consisted of three intervention adaptations aimed at incorporating “cultural re-centering” in an adapted version of the original EBI. Using an Interactive Systems Framework they examined facilitators and barriers encountered in planning for recruitment, training, and sustainability, in their approach to capacity building which focused on three areas. These areas are: (a) implementation and evaluation, (b) training and technical support provided to tribal residents serving as study collaborators, and (c) generating new data to inform the dissemination of new scientific evidence. Generally these intervention projects focused on building capacity to create implementation delivery infrastructures within these low-resource communities. This approach could be enhanced by incorporating specific cultural factors such as: collectivism-individualism, familismo, traditionalism, personalismo, respeto, and simpatia (see Table 1).

Although research on familismo emerged in sociological research conducted with Latinx families, there exists a cross cultural recognition regarding the importance of familismo among many world cultures. Williams and collaborators conducted an international implementation project in China's rural Hunan Province. They conducted a culturally adapted nursing intervention to improve medication adherence among people living with AIDS (PLWA) (3). Investigators established an adaptation team in partnership with a local Community Advisory Board. This partnership included persons living with AIDS and local healthcare workers. Cultural issues encountered included: (a) the high value and importance of the family (high familismo) within rural Chinese communities; (b) stigma as a barrier to treatment participation based on the strong Chinese value and cultural factor of “saving face,” which emphasizes avoiding behaviors that bring shame to one's family, and the importance of preserving family honor; (c) travel barriers existing within the rural Hunan province; and (d) the low level of knowledge about HIV/AIDS among many residents of these rural Chinese communities.

From this study investigators offered six recommendations for conducting cultural adaptations in a low resource community: (a) involve stakeholders from the beginning; (b) throughout the project, conduct a needs assessment that involves continual assessments; (c) evaluate the original intervention for necessary adaptations to intervention implementation; (d) identify mismatches in intervention components and activities with local culture beliefs and values; (e) identify sources of fidelity-fit tensions; and (f) throughout the project document the process of adaptation (3).

Iguchi et al. conducted a cultural adaptation of a Family-Based Treatment (FBT) for anorexia nervosa for implementation in Japan (69). Investigators reported on systemic cultural barriers encountered in this implementation. Given the strong value of familismo within Japanese culture, especially among families who observe traditional gender roles, investigators report that often clinical staff would exclude a youth's parents from participating in the treatment process. Investigators regarded this exclusion as a means of inadvertently disempowering parents and distancing them from a direct role in caring for their child's anorexic nervosa (69). This emerged as a significant cultural mismatch and barrier to the implementation of a Family-Based Treatment for anorexia nervosa in Japan.

Within this context, the investigator needed to consider that traditional Japanese cultural norms and gender role expectations dictate that Japanese mothers are expected to serve as their child's caretaker, whereas Japanese fathers are expected to be uninvolved with these caretaker duties. These traditional culture gender role expectations needed to be reframed to encourage parental participation. Accordingly, in their cultural adaptation, investigators invited the father to participate in accord with their ascribed role as head of the household. The father was encouraged to attend educational sessions designed to empower parents and to involve them jointly in their child's care. Investigators report that these reframed cultural adaptations improved the delivery of this child-focused anorexia treatment intervention as implemented in Japan.

These studies illustrate some common strategies for incorporating cultural factors into intervention adaptations in the service of intervention dissemination and implementation with diverse ethnocultural groups. These strategies are: (a) from the beginning, establishing a collaborative partnership with community stakeholders by incorporating CBPR principles (3, 66); (b) building community resources to promote implementation readiness such as training in intervention delivery (66, 68); (c) conducting a pre-implementation assessment that includes evaluating intervention contents to rectify cultural mismatches and to increase the intervention's cultural acceptability among local community residents (68, 69); (d) conducting a stage-wise process of implementation activities that support drivers of the implementation process; (e) monitoring implementation progress by documenting adaptation changes and reasons for them; and (f) engaging in sustainability planning to ensure intervention continuity.

From the 73 identified implementation strategies presented by the Expert Recommendations for Implementation Change (ERIC) project, Table 3 presents six selected implementation strategies expanded to illustrate how Latinx cultural factors may be integrated into some of these 73 recommendations. For each of six implementation strategies presented, the descriptive column titled, “Possible Expansion with Cultural Factors” presents the original journal article text as supplemented with a cultural adaptation using certain Latinx cultural factors. These culturally adapted extensions are indicated in italic bold face font.

For example, one strategy is developing university or academic partnerships for, “sharing training and bringing research skills to an important project.” A cultural expansion of this strategy could add that, “Intervention project staff can invite the participation of Latinx academic scholars” to provide their disciplinary expertise to “describe and explain how cultural factors can aid in tailoring the intervention for greater cultural relevance for community residents from the major Latinx acculturation sectors (low acculturation, bicultural, high acculturation).” In a similar manner, efforts can promote the acceptability of an intervention by clarifying “which elements of the intervention must be maintained to preserve fidelity.” This strategy can be expanded by determining also “what must be modified or new modules added to increase the intervention's cultural relevance for each of the major cultural sectors from the local Latinx community.” This addition emphasizes an approach to cultural adaptation from the perspective of a resolution of the Fidelity-Adaptation Dilemma described earlier. This also involves the need to address the within-population heterogeneity in Latinx populations, by attending to major acculturation sectors that exist among the residents of the local community.

Our study may be one of the first to conduct an empirically based identification of the most salient Latinx cultural factors in the literature from the stress-coping research field based on quality research studies published in the years 2000–2020. We also advance beyond other descriptions of Latinx cultural factors by providing specific contexts that can aid in understanding the role of these salient cultural factors in EBI enhancement and fit, and for delivery with Latinx patients/consumers. This may facilitate EBI implementation within diverse Latinx community settings.

Our study also argues that the field of implementation science has not incorporated cultural factors generally, and Latinx cultural factors in particular, as components that can improve implementation strategies in dissemination and implementation research. Although other fields also lack such a focus on cultural factors, given the importance of promoting health equity (38) among ethnocultural groups in the US, we encourage implementation scientists to explore the utilization of various cultural factors to inform the strategic development and adaptation of various EBIs for their effective implementation especially with ethnocultural groups and communities.

Based on the present review's focus on the field of Latinx stress-coping research, our study identified the most salient Latinx cultural factors from that field. We also describe the effects of these salient Latinx cultural factors within the context of stress-coping research. A similar review from literature in a significantly different Latinx research field may produce themes and related cultural factors that differ from those identified in the present study. By contrast, some of the more salient identified themes in our review, such as “acculturation,” “discrimination,” and “immigration” might still emerge in reviews conducted with other research areas.

Future research can further describe and apply Latinx cultural factors to assess their effects in developing a secure ethnic identity toward increasing the efficacy of an intervention such as Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. As we promote the effective reach, dissemination, implementation, and sustainability of EBIs within diverse Latinx communities, implementation scientists are encouraged to discover, examine, and apply implementation facilitators and strategies as supplemented by Latinx cultural factors in EBI implementation within diverse Latinx community settings.

As we have described and illustrated, Latinx cultural factors are rich constructs that can add depth of cultural description and analysis for designing EBIs, and for their dissemination and implementation within various Latinx communities. A greater understanding of contextual aspects introduced by specific cultural factors, such as levels of acculturation and Latinx traditional family values may reduce or eliminate implementation barriers and inform intervention implementation. In the past, given that Latinx cultural factors received little coverage and utilization in the field of implementation science, implementation scientists are encouraged to better understand the use of Latinx cultural factors, to inform more effective dissemination and implementation strategies. This can enhance an intervention's acceptability and effectiveness and improve its implementation within diverse Latinx and other communities of color.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

FC conceptualized this study, conducted the NVivo qualitative data analyses with support from his research assistants, and prepared the initial draft of this manuscript. CB contributed to the review of literature, editing, and introduced questions and issues for consideration. DE contributed editorial comments and raised issues and questions to improve this manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^In this article we use the terms “Hispanic” and “Latinx” synonymously. The term Latinx refers to Latino men (Latinos) and women (Latinas) with the general term Latinx serving as a non-gendered term. Presently, among Latinx/Hispanic scholars there is no consensus in preference for the use of these two terms. The US Census uses the term “Hispanic” to refer to, “people whose origin is Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Spanish-speaking Central and American countries, or other Hispanic/Latino regardless of race” (2).

1. Barrera MJ, Berkerl C, Castro FG. Directions for the advancement of culturally adapted preventive interventions: local adaptations, engagement, and sustainability. Prev Sci. (2017) 18:640–8. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0705-9

2. U.S. Census. Table 1. Population by Sex, Age, Hispanic Origin, and Race: 2021, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 2021. US Bureau of the Census (2022).

3. Williams AB, Wang H, Burgess J, Li X, Danvers K. Cultural adaptation of an evidence-based nursing intervention to improve medication adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in China. Int J Nurs Stud. (2013) 50:487–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.08.018

4. Balis LE, Kennedy LE, Houghtaling B, Harden SM. Red, yellow, and green light changes: adaptations to extention health promotion programs. Prev Sci. (2021) 22:903–12. doi: 10.1007/s11121-021-01222-x

5. Castro FG, Yasui M. Advances in EBI development for diverse populations: towards a science of intervention adaptation. Prev Sci. (2017) 18:623–9. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0809-x

6. Castro FG, Kessler R. Cultural factors in prevention. In:O'Donohue W, Zimmerman M, , editors. Handbook of Evidence-Based Prevention of Behavioral Disorders in Integrated Care. Berlin: Springer Nature (2021). p. 51–81.

7. Boyd RC, Castro FG, Finigan-Carr N, Okamoto SK, Barolw A, Kim BE, et al. Strategic directions in prevention intervention research to advance health equity. Prev Sci. (2022). doi: 10.1007/s11121-022-01462-5

8. Elliott DS, Mihalic S. Issues in disseminating and replicating effective prevention programs. Prev Sci. (2004) 5:47–53. doi: 10.1023/B:PREV.0000013981.28071.52

9. Castro FG, Barrera MJ, Martinez CR. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prev Sci. (2004) 5:41–6. doi: 10.1023/B:PREV.0000013980.12412.cd

10. Mejia A, Keijten P, Lachman JM, Parra-Cadona JR. Different strokes for different folks? Contrasting approaches to cultural adaptation of parenting interventions. Prev Sci. (2017) 18:630–9. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0671-2

11. Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Schoenfelder E, Sandler IN. Putting the pieces together: an integrated model of program implementation. Prev Sci. (2011) 12:23–33. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0186-1

12. Dusenbury LA, Brannigan R, Hansen WB, Walsh J, Falco M. Quality of implementation: developing measures crucial to understanding the diffusion of preventive interventions. Health Educ Res. (2005) 20:308–13. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg134

13. Wiltsey Stirman S, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. (2019) 14:58. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0898-y

14. Triandis HC, Malpass RS, Davidson AR. Psychology and culture. Annu Rev Psychol. (1973) 24:355–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.24.020173.002035

15. Castro FG, Hernendez Alarcon E. Integrating cultural variables into drug abuse prevention and treatment with racial/ethnic minorities. J Drug Issues. (2002) 32:783–810. doi: 10.1177/002204260203200304

16. Terrell MD. Ethnocultural factors and substance abuse: towards culturally sensitive treatment models. Psychol Addict Behav. (1993) 3:162–7. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.7.3.162

17. Cervantes RC, Goldbach JT, Varela A, Santisteban DA. Self-harm among Hispanic adolescents: investigating the role of culture-related stressors. J Adol Health. (2014) 55:633–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.05.017

18. Cuellar I, Arnold B, Gonzalez G. Cognitive referents of acculturation: assessment of cultural constructs in Mexican Americans. J Community Psychol. (1995) 21:339–56. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(199510)23:4<339::AID-JCOP2290230406>3.0.CO;2-7

19. Atherton O, Ferrer E, Robins RW. The development of externalizing symptoms from late childhood through adolescence: a longitudinal study of Mexican-origin youth. Dev Psychol. (2018) 54:1135–47. doi: 10.1037/dev0000489

20. Berkel C, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Tein J-Y, Roose MW, Gonzales NA, et al. Discrimination and adjustment for Mexican American adolescents: a prospective examination of the benefits of culturally-related values. J Res Adol. (2010) 20:893–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00668.x

21. Roosa MW, Zeiders KH, Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Tien J-Y, Saenz D, et al. A test of the social development model during the transition to junior high with Mexican American adolescents. Dev Psychol. (2011) 47:527–37. doi: 10.1037/a0021269

22. Lehman DR, Chiu C, Schaller M. Psychology and culture. Annu Rev Psychol. (2004) 55:689–714. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141927

23. National Institute on Drug Abuse N. Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse N (1999).

24. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

25. Ramirez Garcia JI. Integrating Latina/o ethnic determinants of health in research to promote population health and reduce health disparities. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. (2019) 25:21–31. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000265

27. Parra-Cadona JR, Bybee D, Sullivan CM, Rodriguez Dominich MM, Dates B. Examining the impact of differential cultural adaptation with Latina/o immigrants exposed to adapted parent training interventions. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2021) 85:58–71. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000160

28. Umana-Taylor AJ, Updegrall KA. Latino adolescents' mental health: exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depression. J Adolesc. (2007) 30:549–67. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002

29. Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 5th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage (2018).

30. Peters MF. Racial socialization of young Black children. In:McAdoo HP, , editor. Black Children: Social, Educational, and Parental Environments. Los Angeles, CA: Sage (2002). p. 57–72.

31. Caughy MO, Randolph S, O'Campo PJ. The africentric home environment inventory: an observational measure of the racial socialization features of the home environment for African American preschool children. J Black Psychol. (2002) 28:37–52. doi: 10.1177/0095798402028001003

32. Berkel C, Murry VM, Roulson KJ, Brody GH. Understanding the art and science of implementation in the SAAF efficacy trial. Health Educ. (2013) 11:297–323. doi: 10.1108/09654281311329240

33. Castro FG, Kellison JG, Boyd SJ, Kopak A. A methodology for conducting integrative mixed methods research and data analyses. J Mix Methods Res. (2010) 4:342–60. doi: 10.1177/1558689810382916

34. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression Approach. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford (2018).

35. Palinkas L, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, Chamberlain P, Hurlbert M, Landsverk J. Mixed methods designs in implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. (2011) 38:44–53. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0314-z

36. Castro FG, Coe K. Traditions and alcohol use: a mixed methods analysis. Cult Diversity Ethnic Minor Psychol. (2007) 13:269–84. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.269

37. Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. (2006) 27:167–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103

38. Brownson RC, Kumanyika SK, Kreuter MW, Haire-Joshu D. Implementation science should give higher priority to health equity. Implement Sci. (2021) 16:28. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01097-0

39. Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

40. Kwan BM, Brownson RC, Glasgow RE, Morrato EH, Luke DA. Designing for dissemination and sustainability to promote equitable impacts on health. Annu Rev Public Health. (2022) 43:331–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052220-112457

41. Adsul P, Chambers D, Brandt HM, Fernandez ME, Ramanadhan S, Torres E, et al. Grounding implementation science in health equity for cancer prevention and control. Implement Sci Commun. (2022) 3:56. doi: 10.1186/s43058-022-00311-4

42. Cabassa L, Baumann AA. A two-way street: bridging implementation science and cultural adaptations of mental health treatments. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-90

43. McCreight MS, Rabin BA, Glasgow RE, Ayele RA, Leonard CA, Gilmartin HM, et al. Using the practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) to qualitatively assess multilevel contextual factors to help plan, implement, evaluate, and disseminate health services programs. Transl Behav Med. (2019) 25:1002–11. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz085

44. Baumann AA, Cabassa L. Reframing implementation science to address inequities in health care delivery. Serv Res. (2020) 20:190. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4975-3

45. Castro FG, Cervantes RC, Salinas D, Dilli C. Stress Research in Hispanics 2000 to 2020: A Framework Synthesis Review. Manuscript in preparation.

46. Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage (2017).

47. Suarez-Morales L, Dillon FR, Szapocznik J. Validation of acculturation stress inventory for children. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. (2007) 13:216–24. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.3.216

48. Cucciare MA, Gray H, Azar A, Jimenez D, Gallagher-Thompson D. Exploring the relationship between physical health, depression symptoms, and depression diagnosis in Hispanic dementia caregivers. Aging Ment Health. (2010) 14:274–82. doi: 10.1080/13607860903483128

49. Caetano R, Ramisetty-Minkler S, Caetano Veth PA, Harris TR. Acculturation stress, drinking, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic couples in the U. S. J Interpers Violence. (2007) 22:1431–47. doi: 10.1177/0886260507305568

50. Warren CS, Rios RM. The relationship among acculturation, acculturation stress, endorsement of Western media, social comparison, and body image in Hispanic male college students. Psychol Men Masc. (2013) 14:192–201. doi: 10.1037/a0028505

51. Erving CL. Physical-psychiatric co-morbidity: implications for health measurement and the Hispanic Epidemiological Paradox. Soc Sci Med. (2017) 64:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.10.015

52. Cervantes RC, Fisher DG, Padilla AM, Napper LE. The Hispanic stress inventory version 2: Improving assessment of acculturation stress. Psychol Assess. (2016) 28:509–22. doi: 10.1037/pas0000200

53. Forster M, Grigsby T, Soto DW, Schwartz MD, Unger JB. The role of bicultural stress and perceived context of reception in the expression of aggression and rule breaking behaviors among recent-immigrant Hispanic youth. J Interpers Violence. (2015) 30:1807–27. doi: 10.1177/0886260514549052

54. Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Zamobanga BL, Loranzo-Blanco E, Des Rosiers SE, et al. Trajectories of cultural stressors and effects of mental health and substance use among Hispanic immigrant adolescents. J Adolesc Health. (2015) 56:433–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.011

55. Meca A, Zamboanga BL, Lui PP, Schwartz SJ, Lorenzo-Blanco E, Gonzales-Backen MA, et al. Alcohol initiation among recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents: Roles of acculturation and social stress. Am J Orthopsychiatry. (2019) 89:569–78. doi: 10.1037/ort0000352

56. Alvarado M, Ricard RJ. Developmental assets and ethnic identity as predictors of thriving in Hispanic adolescents. Hisp J Behav Sci. (2013) 35:510–23. doi: 10.1177/0739986313499006

57. Arevalo-Flechas LC, Action GJ, Escamilla MI, Bonner PN, Lewis SL. Latino Alzheimer's caregiving: what is important to them? J Manag Psychol. (2014) 29:661–84. doi: 10.1108/JMP-11-2012-0357

58. Goldbach JT, Berger Cardozo J, Cervantes RC, Duran L. The relationship between stress and alcohol use among Hispanic adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav. (2015) 29:960–8. doi: 10.1037/adb0000133

59. Cuellar I, Bastida E, Braccio SM. Residency in the United States, subjective well-being, and depression in an older Mexican-origin sample. J Aging Health. (2004) 16:447–66. doi: 10.1177/0898264304265764

60. Cano MA, Sanchez M, Trepka MJ, Dillon FR, Sheehan DM, Rojas P, et al. Immigration stress and alcohol use severity among recently immigrated Hispanic adults: examining moderating effects of gender, immigration status, and social support. J Clin Psychol. (2017) 73:294–307. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22330

61. Cheng H, Hitter TL, Adams EM, Williams C. Minority stress and depressive symptoms: familism, ethnic identity, and gender as moderators. Couns Psychol. (2016) 44:841–70. doi: 10.1177/0011000016660377

62. Arbona C, Olivera N, Rodriguez N, Hagan J, Linares A, Weisner M. Acculturative stress among documented and undocumented Latino immigrants in the United States. Hisp J Behav Sci. (2010) 32:362. doi: 10.1177/0739986310373210

63. Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Method. (2003) 15:85–109. doi: 10.1177/1525822X02239569

64. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. (2013).

65. Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, Minkler M. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass (2018).

66. Orengo-Aguayo R, Stewart RW, Villalobos BT, Hernandez Rodriguez J, Dueweke AR, de Arellano MA, et al. Listen, don't tell: partnership and adaptation to implement trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy in low-resource settings. Am Psychol. (2020) 75:1158–74. doi: 10.1037/amp0000691

67. Aarons GA, Hurlbert M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. (2011) 38:4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7

68. Hirchak KA, Herndndez-Vallant A, Herron J, Cloud V, Tonigan JS, McCrady B, et al. Aligning three substance use disorder interventions among a tribe in the Southwest United States: pilot feasibility for cultural re-centering, dissemination, and implementation. J Ethn Subst Abuse. (2020) 21:1219–1235. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2020.1836701

Keywords: cultural adaptations, cultural factors, mixed methods and research methodology, Latinx (Hispanic), NVivo

Citation: Castro FG, Berkel C and Epstein DR (2023) Cultural adaptations and cultural factors in EBI implementation with Latinx communities. Front. Public Health 11:1007328. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1007328

Received: 30 July 2022; Accepted: 06 February 2023;

Published: 21 March 2023.

Edited by:

Marina McCreight, United States Department of Veterans Affairs, United StatesReviewed by:

Calia A. Morais, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Castro, Berkel and Epstein. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Felipe González Castro, YXRmZ2NAYXN1LmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.