- 1College of Landscape Architecture and Art, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China

- 2Department of Urban Planning, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, China

- 3International Digital Economy College, Minjiang University, Fuzhou, China

- 4Department of Spatial Culture Design, Kookmin University, Seoul, South Korea

Urban parks have consistently played an important role in people's living environment, reflecting house prices and the extent of the people's attention. Although many studies have been conducted in this filed, the consolidated related research has not been discussed often. Therefore, related papers on the impact of urban park green spaces on housing prices in recent years should be sorted out. Different choices of urban parks and green areas will undoubtedly influence research methods, housing preferences and the nature of the effects. Consequently, a logical framework of previous studies must be constructed. This study will review the literature from four aspects: (i) review of research methods on how park green spaces affect home prices (i.e., Research techniques, such as hedonic price analysis methods, geographically weighted regression models and neural network models, are frequently used in studies, and methodological advancements have helped the field advance); (ii) examining the varying effects of the same or similar types of parkland on home values; (iii) review of studies on the subject, analyzing variations in the scope and degree of the effects of various parks on home values in terms of such factors as park size, accessibility and serving size and (iv) review of innovative research perspectives, translating the issue of impact of parklands on housing prices into a study of the capitalization and amenity of parklands.

Introduction

People are increasingly demanding high-quality living environments as modern civilization spreads globally. The physical environment is an essential determinant of environmental health (1–3), and parklands are amongst the most significant measures of the quality and wellness of the urban environment. Particularly, parks are public green spaces in cities, serving as places for recreation, ecological maintenance, environmental beautification and disaster mitigation and refuge, apart from providing a variety of recreational amenities and services Park green spaces are directly and indirectly beneficial to city dwellers (4) and have the advantages of enhancing aesthetics and physical and mental health, regulating microclimate to reduce energy consumption and providing habitat for wildlife, as well as carbon sequestration (5). Parklands have become amongst the most important considerations of people when buying a property, resulting from the focus on how living near parklands benefits wellbeing and emotional health. Thus, effects of parks on people's living environments is increasingly becoming significant.

Living standards are substantially influenced by environmental health, and the costs (property prices) of high-quality homes reflects this idea directly. Banzhaf and Farooque (6) noted that housing prices are a significant indicator of how people live. As such, they may be used as a criterion to assess a location's livability or attractiveness (7, 8). This idea is particularly relevant when examining the impact of urban environmental health concerns on the assessment of living standards. Given the likelihood that park planning would directly affect people's decisions to buy homes, several academics have begun to investigate the effects of urban parklands on real estate prices. Accordingly, assessing the external economic value of parklands to measure their impact on residential prices provides insights into people's preferences when choosing where to live and also provides important advice for urban planning and real estate development decisions (9). Hence, the impact of urban parklands on prices of residential spaces has become of considerable research interest.

Although the majority of prior research has supported the notion that urban parks may increase the value of residential spaces by enhancing residential amenities, studies and surveys have revealed that parks can, in some circumstances, devalue real estate. For example, unkempt or abandoned amenities, intrusive noise and lights and lack of parking spots on busy streets can have detrimental effects on the value of real estate near parks (10). Accordingly, reviewing the extensive and intricate studies conducted on the issue is evidently important and fascinating.

The three modeling techniques that have been most often employed in this type of study are the hedonic pricing, geographically weighted regression and neural network models (11, 12). The majority of research on how urban parks affect home prices has relied on hedonic price models in conjunction with recent methods, such as geographically weighted regression models, which measure how much buyers are willing to pay for parklands surrounding their homes and use price models to analyze the relationship between parklands and home prices. Synthetic neural network models have become a significant advancement in this field of forecasting in recent years. The reason is that these models are more accurate than conventional hedonic pricing models at anticipating the effects of parks on home values.

Prior research has demonstrated that the effects of various types of parks on home prices vary. Therefore, different parklands could have a certain amount of appreciation and depreciation on their impact on neighborhood house prices by considering the extent to which different sizes, service radii and accessibility of parklands have an impact on home prices. Owing to differences in how purchasers perceive the demand for parks, different park types' effects on house prices can vary significantly between regions and countries. Additionally, different properties are affected differently by the same sort of park. An analysis of the impact of parklands on house prices in terms of market segmentation effects shows heterogeneity in the impact of the same type of park on house prices over time, space and property.

Meanwhile, there are many other different viewpoints on the effects of urban parklands on property prices. Accordingly, some academics have proposed that the research strategy be expanded to include studies on such topics as capitalization of parkland issues and issue of amenity. Such a novel point of view gives government funding for parks and urban green space development a markedly intuitive reference meaning, thereby helping encourage equalization of park green space services and enhancing people's wellbeing.

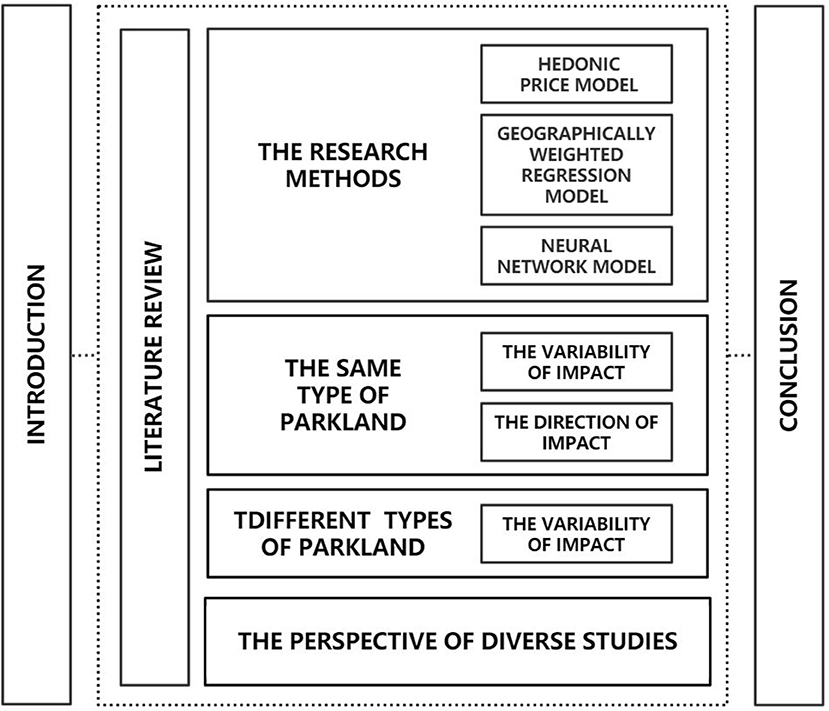

To provide theoretical and literature support for future research on the influence of park green spaces on residential prices, this article will build on the body of existing research on the role of urban park green spaces in affecting residential prices, thoroughly classify the pertinent studies and construct a logical and clear literature framework. This article is divided into three main sections (Figure 1): background introduction, followed by a classification of the literature review and a conclusion of the review.

Literature review

The development and planning of parklands have a considerable impact on urban real estate prices, apart from enhancing and enriching the lives of the people who live there. The review, which was conducted in the following order and examined the literature in terms of research techniques, research viewpoints, comparative contrasts and reviews of significance, presents the following aspects: (i) review of research methods on how parklands affect home prices; (ii) overview of variability on the impact of the same or the same type of parkland on house prices; (iii) overview of how different types of parkland affect home prices differently and (iv) overview of other varied research perspectives.

Theme I: Review of research methods on the impact of parklands on house prices

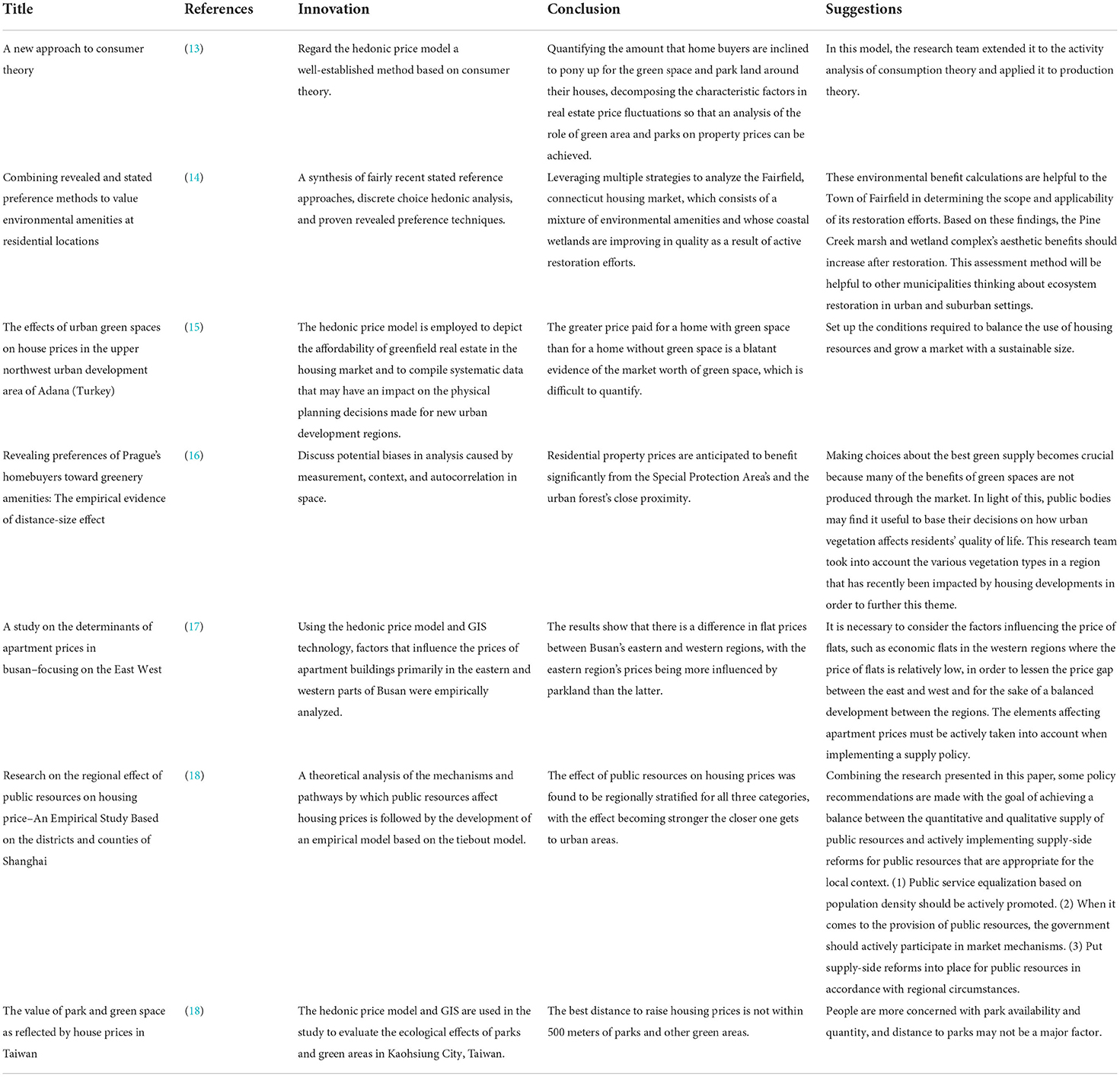

The hedonic price approach has a strong analytical function in terms of spatial relationships and is widely used in the study of natural green space because it can explore micro-level performance. Lancaster (13) suggested that the hedonic price model is a well-established method based on consumer theory. To analyze the effects of parklands on house values, typical components in real estate price fluctuations should be broken down by quantifying the amount that buyers are ready to pay for green spaces around their homes. Earnhart (14) used a joint analysis of Hedonic pricing to precisely quantify the economic and aesthetically pleasing benefits connected to the availability and caliber of environmental facilities in residential communities. Altunkasa and Uslu (15) demonstrated the spatial viability of parklands in the housing market through a pricing assessment approach to gather systematic data that may affect physical planning decisions for future urban development zones. Numerous studies have been conducted in this area on the use of non-market valuation methodologies, particularly the hedonic pricing approach (also known as the hedonic model) to calculate the value of urban parks and greenery to inform urban greening policy. Melichar and Kaprová (16) used a Hedonic price approach as basis in utilizing data from the real market in Prague, the largest urbanized region in the Czech Republic, and discussing the impact of several services provided by the urban environment on house prices in urban areas. Lee et al. (17) used a hedonic price model to study the Busan region chronologically over the period 1960–2011 for house sales and price data. They concluded that the larger the apartment building and the further away from the underground station and park, the lower the house price. Chen (18) explained that urban parks and green spaces are equivalent to such services as transportation and hospitals, and their direct benefits cannot be calculated based on home values. Lai (19) assessed the ecological benefits of parks and green spaces in Kaohsiung City using a typical price model and GIS spatial analytic methodologies. Their results revealed that the closer to parks and green spaces, the higher the property prices.

To deal with the geographical and temporal non-stationarity in real estate market data, researchers have included the spatio-temporal impact of house price movements into geographically weighted regression (GWR) models. This technique has allowed for a better fit to the findings of studies in areas relevant to house prices. Tang et al. (20) evaluated two models to show the spatial heterogeneity of property prices in Shanghai communities and the effects of various influencing factors: regionally weighted regression model and global ordinary least squares (OLS) technique. They concluded that GWR performs better than the global parameter estimates offered by OLS in breaking down local parameters. Moreover, they indicated that GWR can offer insights into the complex relationship between house prices and spatial influencing factors by presenting an overall picture of urban house prices. Zhang et al. (21) used spatial GWR as basis in investigating and assessing the factors impacting the spatial variance of housing in Harbin City. Their findings indicated that the primary factors impacting spatial disparities in home prices are schools, hospitals and greening characteristics. Parks and subways had less of an effect on home prices, whereas commercial centers and building age could raise home values.

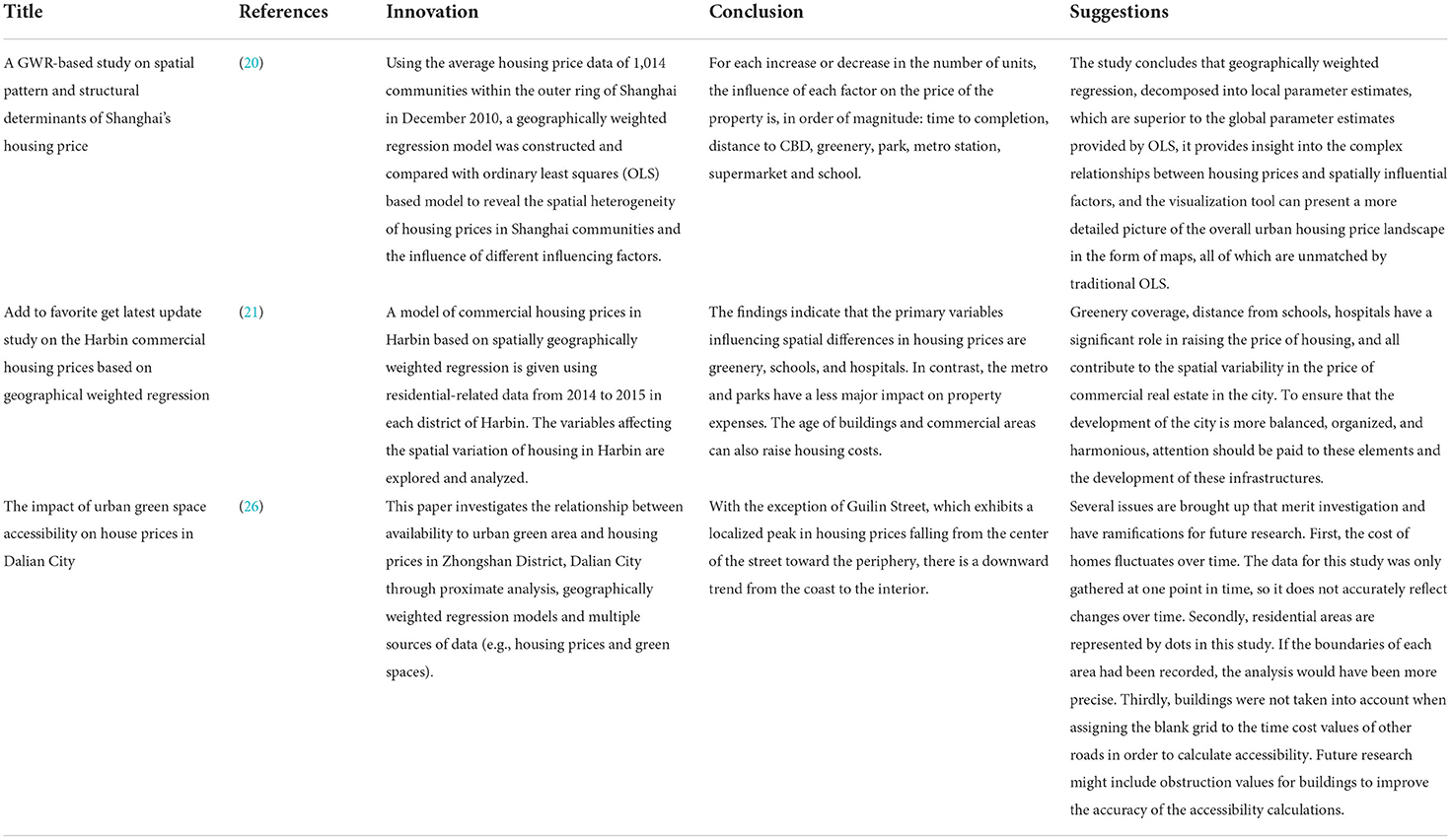

In non-linear multivariate forecasting, synthetic neural network models that have recently gained popularity have excelled and significantly improved forecasting of home prices. House prices and property values are typically estimated using the hedonic price model. This model is straightforward, simple to use and can be utilized to determine the relationship between various variables and home prices. However, traditional hedonic price models are primarily linear and logarithmic models, and both have limitations. The linear model is less effective in explaining the state of multiple non-linear variables, whilst the logarithmic model is more vulnerable to extreme values in the data set and has accuracy issues. Xu et al. (22) used the error sum of the minimum standard absolute value of the linear combination model to calculate the weight of each model in the prediction results. Thereafter, they combined it with neural networks to further improve the accuracy of the prediction; its application in the prediction of house prices in Hefei City achieved the expected results. Ge et al. (23) explained that artificial neural network (ANN) models are a method designed to automatically capture functional forms, allowing the discovery of hidden non-linear relationships between modeled variables. ANN models are ANN methods with the ability to map complex non-linear relationships between variables and have good predictive power. However, the “black box” nature of ANNs is a major limitation because they lack explanatory power. Wang et al. (24) used a delayed neural network model to forecast Singapore's social property prices; the model was successful in producing accurate fits and estimates. Li et al. (25) used hedonic price and neural network models to predict house prices, and compared the accuracy of the two models in predicting the impact of park green space accessibility on house prices. They likewise found that predictions of the neural network model are more accurate than that of the hedonic price model. Tables 1–3 present the specific explanatory research methods.

Theme II: Overview of variability on the impact of the same or the same type of parkland on house prices

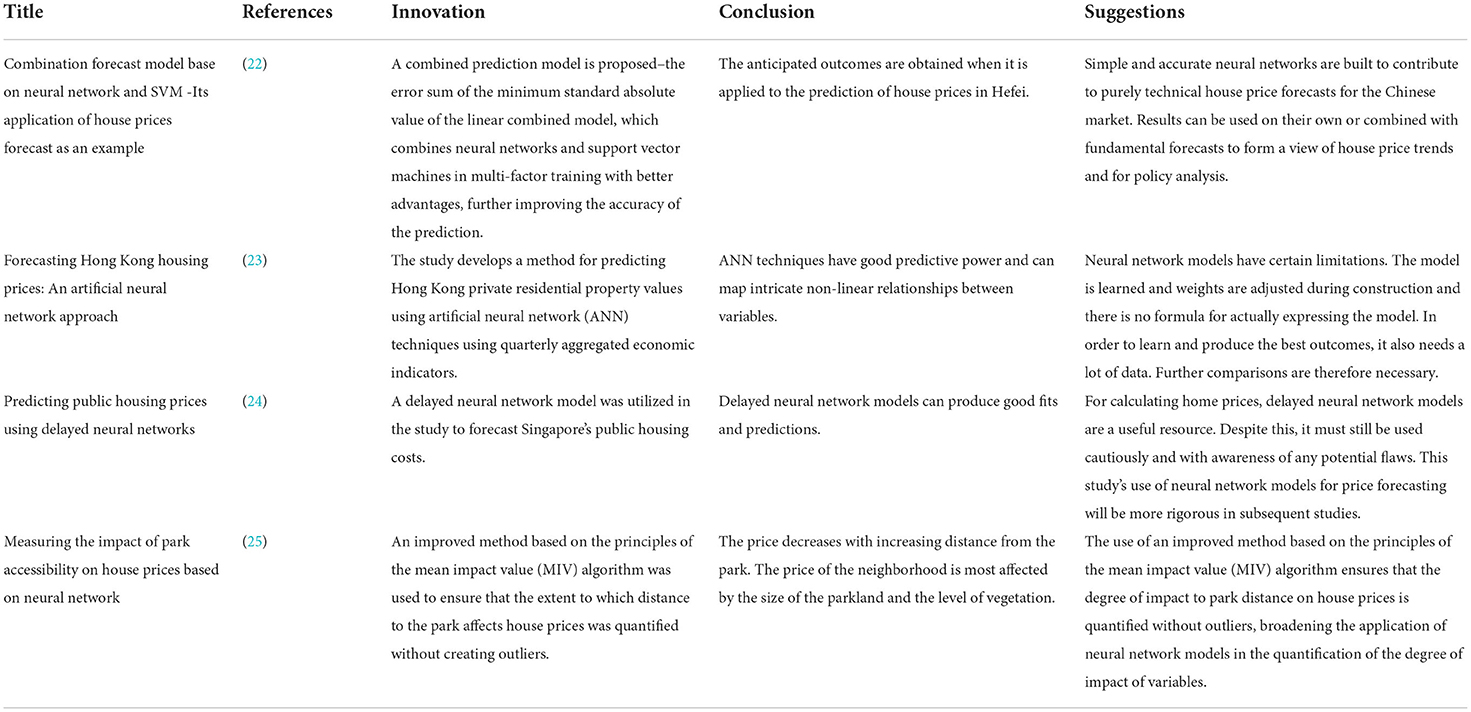

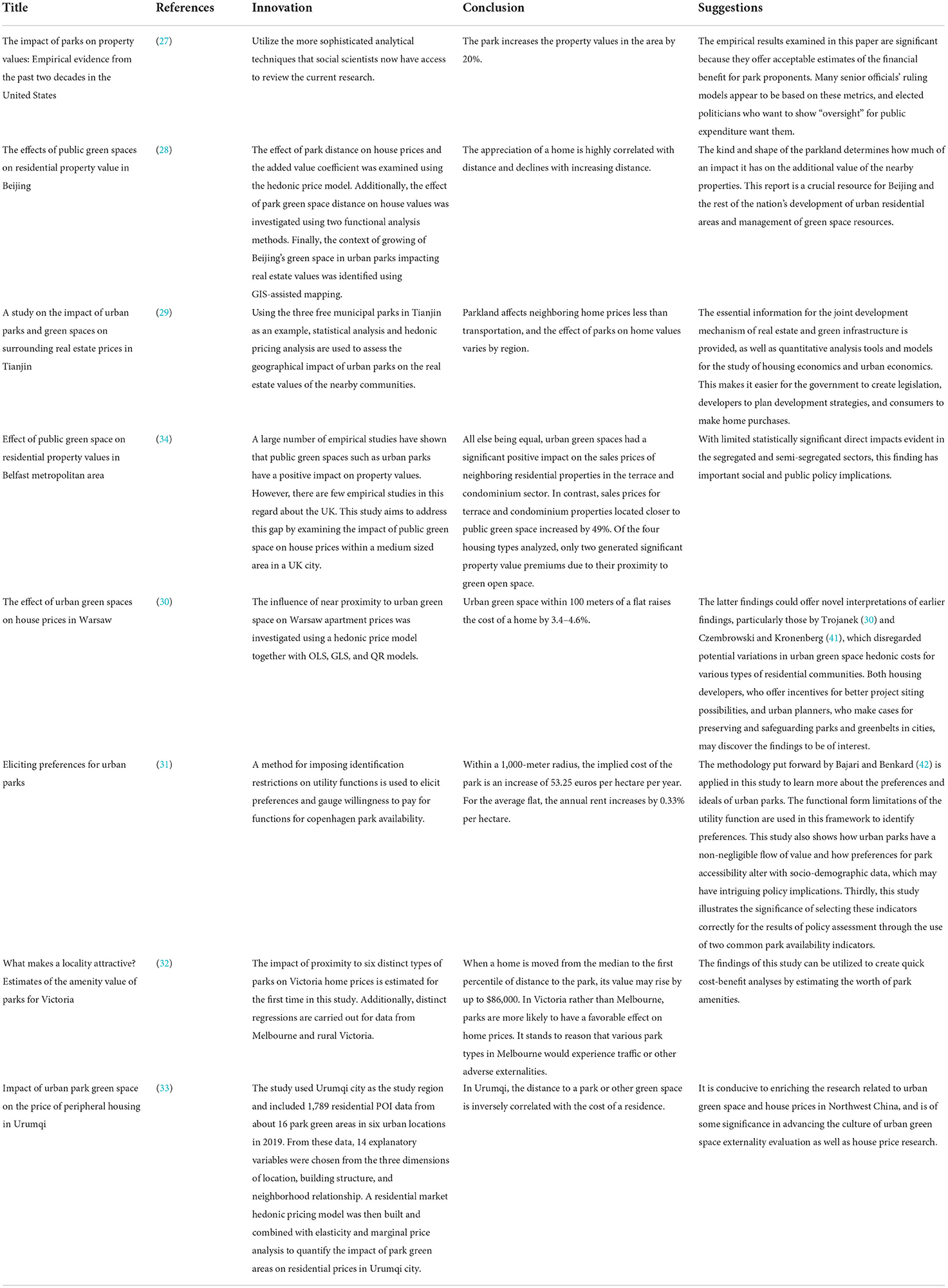

Heterogeneity of time, space and property should be considered when analyzing variables that affect house prices in parklands. As research advances, findings on the degree to which the same or the same type of parkland has a differential impact on house prices have become significant. Crompton (27) stated that the real estate value of parks adjacent to parks will have a positive impact of 20%. Zhang et al. (28) analyzed the impact of urban parklands on real estate values in Beijing by subdividing the parks into six categories by size and type to conduct a detailed analysis to strengthen the findings. They concluded that parklands can have a 0.5–14.1% value-added effect on property prices in the 850–160-m range in their vicinity. Tian (29) used the three free civic parks in Tianjin as examples and concluded that the impact of park green spaces on neighborhood property prices is less than that of traffic, and that the impact of parks on property prices varies between areas. Trojanek et al. (30) used the hedonic price approach, OLS, GLS and QR models to conclude that urban green space within 100 m of a home increases residential prices by 3–4%. Panduro et al. (31) used the hedonic pricing approach to explore the implicit price of urban green space availability. They concluded that within a 1,000-m radius park implicit price is an annual rent increase of 0.33% per annum (31). Evangelio et al. (32) provided a preliminary estimate of the impact of parks on house prices within Victoria. They estimated the hedonic regression of house prices in terms of distance to six types of parks and various other amenities that may affect house prices. Additionally, they determined that certain types of parks can have a significant positive impact on house prices. Liu and Chen (33) concluded that a 1-km decrease in distance to parklands is associated with an average increase in residential prices of RMB 21,840.

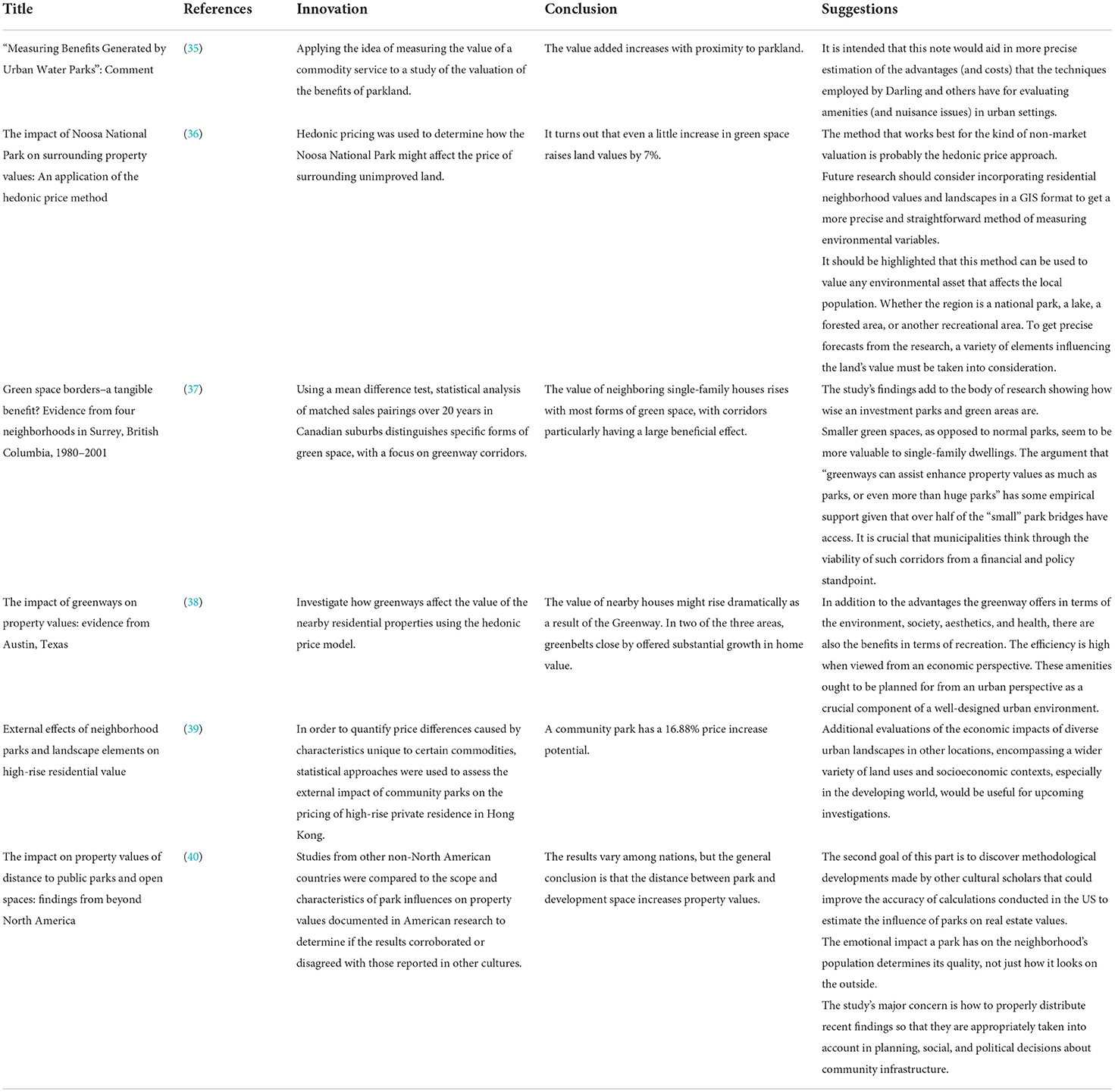

McCord et al. (34) concluded from early research on the hedonic price approach that parklands tend to have an appreciative impact on quality of life and property values. However, several research perspectives have emerged from previous studies. Some scholars have argued that different types of parks have an appreciating and depreciating impact on neighborhood property values. McMillan's (35) analysis of measuring the benefits generated by urban water parks was the beginning of research on the assessment of the economic benefits of urban parks on real estate. Subsequent studies in this area have mostly concluded that urban park green spaces have a positive impact on house prices. However, there is a subset of scholars with different findings, such as Pearson et al. (36), who studied the impact of Noosa National Park on the price of surrounding undeveloped land. They concluded that residential values increased by 7% with a small amount of additional green space resources. However, for properties located south of the park, the value was only 85% of that of properties in the north and did not generate an increase in value. Hobden et al. (37) conducted a statistical analysis of parks in suburban Canada. Particularly, they compared matched sales over a 20-year period and concluded that most types of green space increase the value of nearby single-family homes, with corridor green spaces having an impact on adjacent property values. However, there are some exceptions that negatively affect residential values. Nicholls and Crompton (38) selected three communities in the same city for comparison, two of which are adjacent to green spaces and produce significant property value appreciation benefits. Greenways were found to have a significant positive impact on the sales price of neighboring properties, but the reverse had a negative impact. Jim and Chen (39) purposefully compared the impact of community parks, streetscapes and oceanfront architectural views on surrounding house prices. They concluded that community parks add the most significant value to residential prices, followed by ocean views, boosting premiums by 5.1%, with streetscapes and architectural views being less attractive to residents, thereby resulting in depressing prices. Crompton and Nicholls (40) analyzed the literature on parks and development space on residential values outside North America by US scholars. They concluded that from 11 studies in China, five revealed a relationship of expected appreciation, four reported mixed results of appreciation and depreciation, and two showed no effect of parks on house prices. Three studies from Japan and Australia also showed different results, with subtle differences between the results. Tables 4, 5 provide specific explanatory variable details.

Theme III: Overview of the differential impact of different types of parkland on house prices

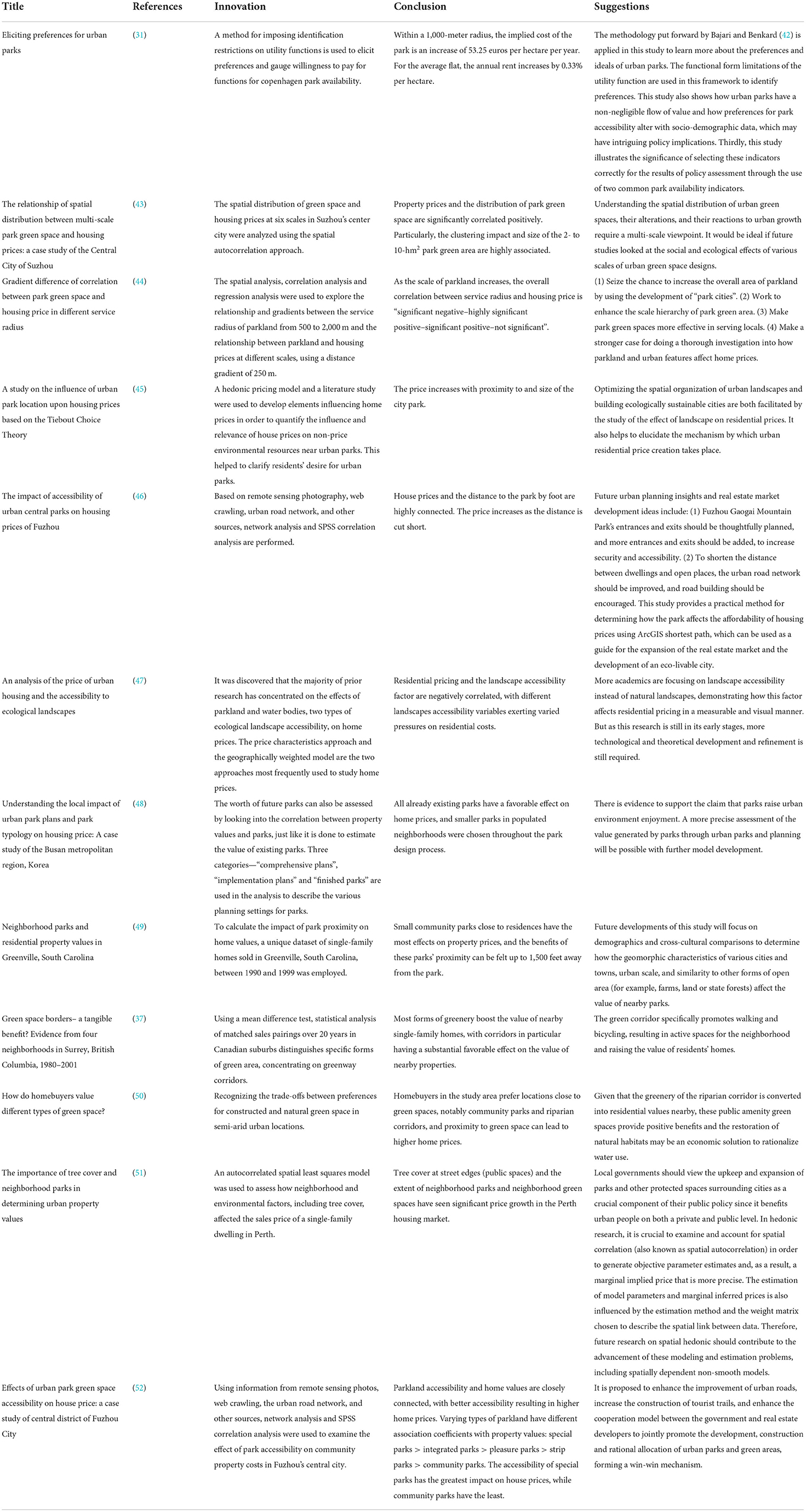

The extent to which different sizes, service radii and accessibility of parklands affect house prices relatively vary, and academic scholars are at a relatively advanced stage of research in this area. Some scholars have studied the extent to which different classes of parkland affect residential prices, concluding that the implicit value of different classes of parks on house prices varies. Panduro et al. (31) proposed a classification of green spaces into eight different types of spaces. They concluded that the types of green spaces with higher ratings in terms of accessibility and maintenance levels had higher implicit prices, whilst the types with lower ratings had lower implicit values. Wu et al. (43) analyzed the spatial distribution of green spaces and house prices at six scales in the central city of Suzhou. The distribution of park green spaces and real estate prices were significantly and positively correlated. Particularly, the scale of 2–10 hm2 park green space was closely related, and the clustering effect was prominent. Wu et al. (43) proposed an analysis of the impact of park green spaces at different scales, dividing parks into five classes according to size. The overall trend of “overlooked spot clustering–overlooked spot and hot spot clustering–hot spot clustering–divergence–insignificant” and the overall spatial distribution of park green spaces and property prices showed a significant positive correlation. The findings are an innovation on the basis of previous research findings and present new research ideas in this area. Subsequently, Wu and Shao (44) proposed a gradient difference in the correlation between parklands and housing prices at different service radii based on the analysis of parklands at different scales (with a distance gradient of 250 m). They concluded that housing with higher prices generally had more parklands around a 1,000-m service radius, and that for every 100-hm2 increase in parkland within 2,000 m of a residential area, housing unit prices increased by about RMB 1,000/m2. Many cases in the literature have shown that the accessibility of parklands is used as a differentiator for housing prices. Yang (45) focused on the choice of residential location and further investigated the effects of park size and distance on housing prices, concluding that houses will cost more the closer they are to urban parks and the bigger the parks' area are. Tan et al. (46) categorized accessibility issues from another perspective for comparison. The analysis of the impact on house prices in Fuzhou City delineated urban park accessibility within the Third Ring Road and urban park accessibility outside the Third Ring Road by proximity to the city center. They concluded that park accessibility within the Third Ring Road has higher impact on property prices than in urban areas outside the Third Ring Road, with higher accessibility leading to higher house prices overall. Liu (47) determined that the landscape accessibility factor has a negative relationship with residential prices, and that different landscapes accessibility factors have different effects on residential prices.

The degree of impact of different types of parkland on house prices in different areas can vary, and scholars in different countries have reached their respective conclusions. Kim et al. (48) selected flats in Busan, South Korea as subject of their study to categorize the temporal context of different plans for parks. Specifically, they integrated planned, implemented plans and completed parks to investigate what scale of park types were preferred by planners at different times. The degree of influence of parklands varies from one region to another and from one country to another. Chinese and foreign scholars have analyzed different types of parks and found that domestic residents prefer specialized types of parks with themes, whilst residents of some European and American countries prefer smaller community parks. Espey and Owusu-Edusei (49) found that proximity to small community parks had the greatest impact on house prices. Hobden et al. (37) analyzed four Surrey neighborhoods and found that most forms of green space increase the costs of single-family homes, with particular emphasis on the significant positive impact of ribbon greening on property values. Bark et al. (50) concluded a preference for green corridor-type parks in semi-arid urban areas. Pandit et al. (51) concluded that tree cover at the edge of a street is equivalent to a further 10% increase in other parks. However, Tan et al. (52) divided types of parks into five main categories and showed that strip parks have a smaller impact on house values and the greatest impact was seen in the dedicated park category. This difference is rooted in the different value demands that residents want parks and green spaces to provide. Chinese residents consider the location of strip parks and the limited thematic content they carry to be of a lower quality than specialized parks, and demand more content and quality from their parks. Residents in Europe and the US consider corridors and ribbon parks to be convenient for their daily exercise and considerably more accessible than large parks. They also consider that high-grade parks will inevitably create more noise and parking shortages, which will substantially reduce their home comfort. Therefore, they prefer to buy houses with small green belt parks nearby. Table 6 shows the specific explanatory variable details.

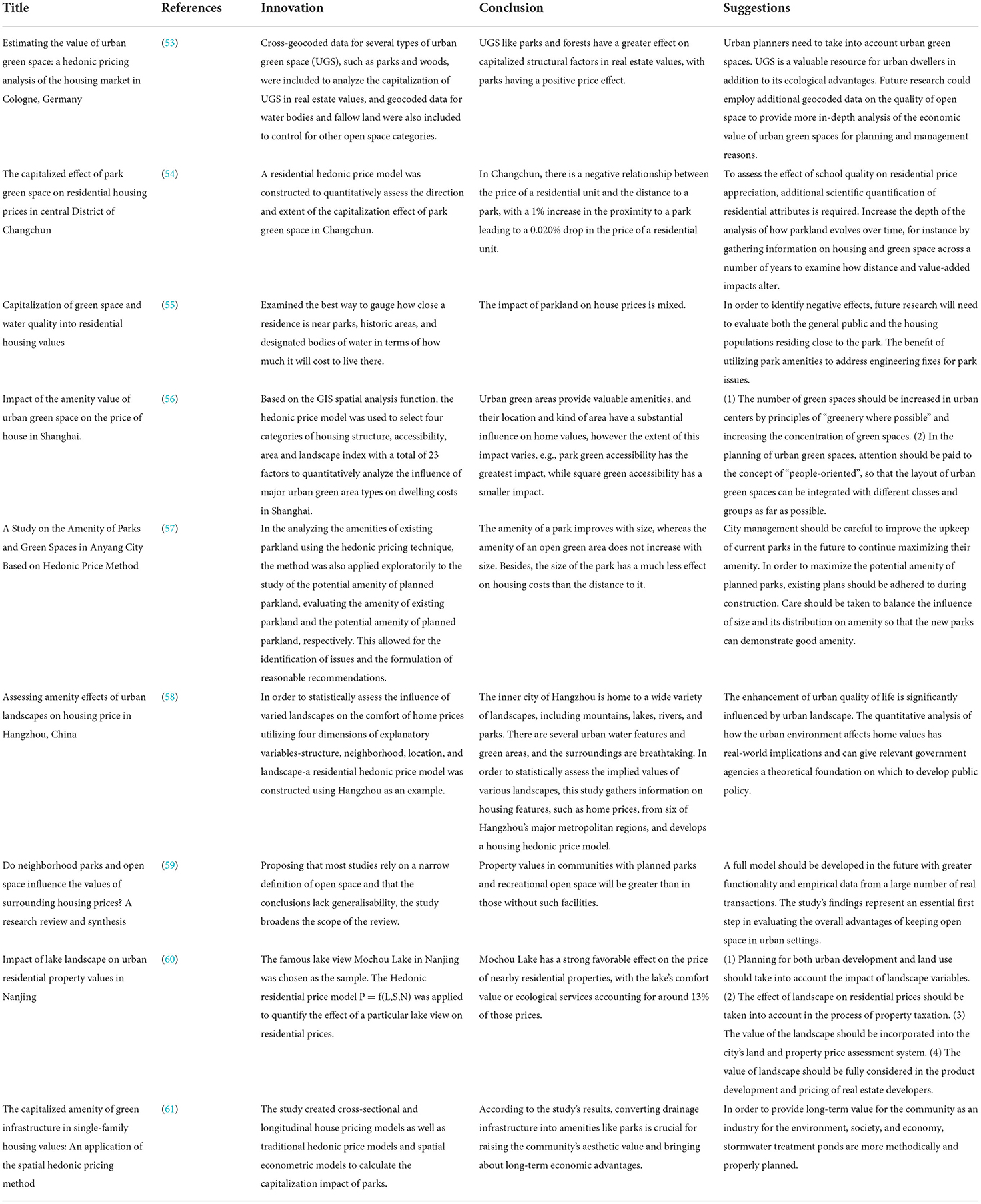

Theme IV: Retrospective overview on the perspective of diverse studies

Although the research on the impact of parklands on house prices has progressed, apart from the traditional direct research on the impact of parklands on changes in residential prices, the research has been suggested to possibly be transformed into studies on such aspects as capitalization issues and amenity issues of parklands. Kolbe and Wüstemann (53) showed that urban greenery, such as parklands, has a significant impact on the capitalization structure variable in real estate prices by calculating the coverage of parklands around dwellings and the continuous distance from them. Cai and Liu (54) proposed to translate the study into an assessment of the capitalization benefits of park green spaces. They showed that a 1% increase in distance to park green spaces is associated with a 0.020% decrease in residential unit prices. Bedell (55) investigated how to value the relationship with parks in terms of residential prices. Specifically, they proposed to capitalize on green spaces and water quality to assess the degree of impact on residential values. He concluded that proximity to parks has a negative impact on housing values, with a positive impact if there is greater continuity of park facilities valued. Amenity value of urban green spaces refers to the degree to which the ecological, economic and socio-cultural functions provided by these spaces are satisfying to urban residents. Yin et al. (56) referred to the concept of urban green space amenity and applied this implicit concept to a hedonic price model commonly used in economics to assess the impact of green space amenity on housing prices. They likewise provided advice to urban planners on the need for orderly “greening”. Qi (57) referred to the concept of amenity in her article titled “A Study on the Amenity of Parks and Green Spaces in Anyang City Based on Hedonic Price Method”, suggesting the necessity for urban planners and policy makers to have a more accurate grasp of the amenity of urban green spaces to effectively control and guide the expansion of urban spaces. Wen et al. (58) used Hangzhou as an example and used structural, neighborhood, location and landscape dimensions as explanatory variables. Additionally, they applied a residential hedonic price model to objectively assess the impact of various landscapes on house prices in terms of amenity. They concluded that when the proximity to West Lake and nearby parks increases by 1%, house prices decrease by 0.229 and 0.052%, respectively, whilst a 1% increase in park area increases house prices by 0.008%. Aliyu et al. (59) suggested that the presence of green spaces in parks enables residents to live in a more enjoyable environment and substantially increases personal wellbeing. Extensive surveys have indicated that parks positively affect property values, with planned parks and recreational open space community parks adding the most value. Research on parkland amenity issues has confirmed the reliability of the hedonic price approach in existing parkland studies and its potential application to planned parklands (60). Sohn et al. (61) evaluated the market value of residential properties in four zoning districts in Houston and concluded that living near green spaces has a positive capitalizing effect on the costs of a single-family property. Accordingly, living nearby promotes house price increases over a 10-year period. Table 7 shows the context of diverse studies.

Conclusion

Research on the impact of urban parklands on house prices has been well-referenced, and this paper provides a categorized review of previous studies in terms of research methods, findings and research perspectives. From a research perspective, previous research methods have focused on the common hedonic price modeling, GWR and neural network modeling approaches, all of which have been relatively well-established and remain widely used in relevant price system studies. The review of the findings is divided into two main sections: (1) differential impact of the same type of parkland on the price of different homes and (2) differential impact of differential parkland on the price of homes. The final section reviews other relevant research perspectives on the impact of parklands on house prices. We are optimistic that this literature review will be useful for future scholars to engage in related research directions at the supplementary and reference levels. We are likewise looking forward to scholars and researchers supplementing and improving previous studies in terms of more research methods, research subjects and research perspectives, so that research on the impact of parklands on house prices can be more mature to serve all people with relevant opinions.

Lastly, there are also some possible future research directions suggested in this article. Studies are limited on how urban parklands affect pricing when other factors are considered, even though research on the impact of parks on housing prices is relatively well-established. Additionally, there is a dearth of study on the variations in the effect of parkland variables on home prices over time, and the majority of previous studies have focused on the effects of parkland variables on house prices at the same period. Additionally, earlier research has concentrated more on the association between parklands' effects on home values and those prices than on the cause of that effect. In the future, the causality of parks on home prices should be explored using more comparative methodologies, such as the difference-in-differences model.

Author contributions

KC contributed to conception and design of the study. HL organized the database. KC and SY performed the statistical analysis. KC and HL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SY and YH wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from Chengdu Park City Demonstration Zone Construction Center (Chengdu gongyuan chengshi shifan qu jianshe yanjiu zhongxin) (No. GYCS2021-YB004).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Yang L, Tang X, Yang H, Meng F, Liu J. Using a system of equations to assess the determinants of the walking behavior of older adults. Transactions in GIS. (2022) 26:1339–54. doi: 10.1111/tgis.12916

2. Yang L, Ao Y, Ke J, Lu Y, Liang Y. To walk or not to walk? Examining non-linear effects of streetscape greenery on walking propensity of older adults. J Transp Geogr. (2021) 94:103099. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103099

3. Yang L, Liu J, Liang Y, Lu Y, Yang H. Spatially varying effects of street greenery on walking time of older adults. ISPRS Int J Geo Inf. (2021) 10:596. doi: 10.3390/ijgi10090596

4. Wimalasiri N, Hemakumara G. GIS Based Analysis To Assess The Benefits Of Green Areas In The Urban Core (With Special Reference To The Vihara Maha Devi Park In Colombo. Bangalore: IJRET (2016).

5. Sadeghian MM. The Health Benefits of Urban Green Spaces, a Literature Review. New Delhi: IJARIIE (2018).

6. Banzhaf HS, Farooque O. Interjurisdictional housing prices and spatial amenities: Which measures of housing prices reflect local public goods? Reg Sci Urban Econ. (2013) 43:635–48. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2013.03.006

7. Yang L, Zhou J, Shyr OF, Huo DD. Does bus accessibility affect property prices? Cities. (2019) 84:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2018.07.005

8. Yang L, Liang Y, He B, Lu Y, Gou Z. COVID-19 effects on property markets: the pandemic decreases the implicit price of metro accessibility. Tunnell Underground Space Technol. (2022) 125:104528. doi: 10.1016/j.tust.2022.104528

9. Hagerty JK, Stevens TH, Allen PG, More T. Benefits from urban open space and recreational parks: a case study. J Northeast Agric Econ Council. (1982) 11:13–20. doi: 10.1017/S0163548400003125

10. Crompton JL. The Proximate Principle: The Impact of Parks, Open Space and Water Features on Residential Property Values and the Property Tax Base. Ashburn: National Recreation and Park Association (2004).

11. Yang L, Chau KW, Szeto WY, Cui X, Wang X. Accessibility to transit, by transit, and property prices: Spatially varying relationships. Transport Res Part D Transp Environ. (2020) 85:102387. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2020.102387

12. Yang L, Chu X, Gou Z, Yang H, Lu Y, Huang W. Accessibility and proximity effects of bus rapid transit on housing prices: heterogeneity across price quantiles and space. J Transp Geogr. (2020) 88:102850. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102850

13. Lancaster KJ. A new approach to consumer theory. J Polit Econ. (1966) 74:132–57. doi: 10.1086/259131

14. Earnhart D. Combining revealed and stated preference methods to value environmental amenities at residential locations. Land Econ. (2001) 77:12–29. doi: 10.2307/3146977

15. Altunkasa MF, Uslu C. The effects of urban green spaces on house prices in the upper northwest urban development area of Adana (Turkey). Turk J Agric Forest. (2004) 28:203–9. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.28625.43367

16. Melichar J, Kaprová K. Revealing preferences of Prague's homebuyers toward greenery amenities: the empirical evidence of distance-size effect. Landsc Urban Plann. (2013) 109:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.09.003

17. Lee O, Chol J. A study on the determinants of apartment prices in busan—focusing on the east west. Resident Environ Institut Korea. (2015) 13:53–66. Available online at: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE06386695&language=ko_KR&hasTopBanner=true

18. Chen X. Research on the Regional Effect of Public Resources on Housing Price–An Empirical Study Based on the districts and counties of Shanghai (Master's Thesis). East China Normal University, Shanghai (In Chinese) (2016).

19. Lai P. The Value of Park and Green Space as Reflected by House Prices in Taiwan (No. eres2017_353). Delft: European Real Estate Society (ERES) (2017).

20. Tang Q, Xu W, Ai F. A GWR-based study on spatial pattern and structural determinants of Shanghai's housing price. Econ. Geogr. (2012) 32:7 (in Chinese) doi: 10.1109/GeoInformatics.2011.5980723

21. Zhang B, Cao L, Wang L, Gao Y. Add to favorite get latest update study on the harbin commercial housing prices based on geographical weighted regression. Nat Sci J Harbin Normal Univ. (2016) 3:11–14 (in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-5617.2016.03.004

22. Xu F, Xie R, Hao J. Combination forecast model base on neural network and SVM–Its application of house prices forecast as an example. J Chaohu College. (2012) 6:1–7 (in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-2868.2012.06.003

23. Ge JX, Runeson G, Lam KC. Forecasting Hong Kong housing prices: an artificial neural network approach. In: International Conference on Methodologies in Housing Research. Stockholm (2003).

24. Wang L, Chan F, Wang Y, Chang Q. Predicting public housing prices using delayed neural networks. In: 2016 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON). Singapore: IEEE (2016). p. 3589–92.

25. Li W, Niu Z, Zhang Y. Measuring the impact of park accessibility on house prices based on neural network. Price Monthly. (2020) 9:7–13 (in Chinese). doi: 10.14076/j.issn.1006-2025.2020.09.02

26. Yang J, Bao Y, Jin C. The impact of urban green space accessibility on house prices in dalian city. Scientia Geographica Sinica. (2018) 38:1952–60. doi: 10.13249/j.cnki.sgs.2018.12.002

27. Crompton JL. The impact of parks on property values: empirical evidence from the past two decades in the United States. Manag Leisure. (2005) 10:203–18. doi: 10.1080/13606710500348060

28. Zhang B, Xie G, Xia B, Zhang C. The effects of public green spaces on residential property value in Beijing. J Resour Ecol. (2012) 3:243–52. doi: 10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2012.03.007

29. Tian Y. A study on the impact of urban parks and green spaces on surrounding real estate prices in Tianjin. J Southeast Univ. (2013) 92–7 (in Chinese). doi: 10.13916/j.cnki.issn1671-511x.2013.s2.032

30. Trojanek R. The impact of green areas on dwelling prices: the case of Poznań city. Entrepreneur Bus Econom Rev. (2016) 4:27–35. doi: 10.15678/EBER.2016.040203

31. Panduro TE, Jensen CU, Lundhede TH, von Graevenitz K, Thorsen BJ. Eliciting preferences for urban parks. Reg Sci Urban Econ. (2018) 73:127–42. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2018.09.001

32. Evangelio R, Hone S, Lee M, Prentice D. What makes a locality attractive? Estimates of the amenity value of parks for Victoria. Econ Papers. (2019) 38:182–92. doi: 10.1111/1759-3441.12259

33. Liu Y, Chen T. Impact of urban park green space on the price of peripheral housing in Urumqi. J Arid Land Resour Environ. (2020) 11:36–43 (in Chinese). doi: 10.13448/j.cnki.jalre.2020.295

34. McCord J, McCord M, McCluskey W, Davis PT, McIlhatton D, Haran M. Effect of public green space on residential property values in Belfast metropolitan area. J Finan Manag Prop Constr. (2014) 19:117–37. doi: 10.1108/JFMPC-04-2013-0008

35. McMillan M. “Measuring Benefits Generated by Urban Water Parks”: Comment. Land Econ. (1975) 51:379–81. doi: 10.2307/3144955

36. Pearson LJ, Tisdell C, Lisle AT. The impact of Noosa National Park on surrounding property values: an application of the hedonic price method. Econ Anal Policy. (2002) 32:155–71. doi: 10.1016/S0313-5926(02)50023-0

37. Hobden DW, Laughton GE, Morgan KE. Green space borders–a tangible benefit? Evidence from four neighborhoods in Surrey, British Columbia, 1980–2001. Land Use Policy. (2004) 21:129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2003.10.002

38. Nicholls S, Crompton JL. The impact of greenways on property values: evidence from Austin, Texas. J Leis Res. (2005) 37:321–41. doi: 10.1080/00222216.2005.11950056

39. Jim C, Chen W. External effects of neighbourhood parks and landscape elements on high-rise residential value. Land Use Policy. (2010) 27:662–70. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.08.027

40. Crompton J, Nicholls S. The impact on property values of distance to public parks and open spaces: findings from beyond North America. World Leis J. (2022) 64:61–78. doi: 10.1080/16078055.2021.1910557

41. Czembrowski P, Kronenberg, J. Hedonic pricing and different urban green space types and sizes: insights into the discussion on valuing ecosystem services. Landsc Urban Plann. (2016) 146:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.10.005

42. Bajari P, Benkard CL. Demand estimation with heterogeneous consumers and unobserved product characteristics: a hedonic approach. J Polit Econ. (2005) 113:1239–76. doi: 10.1086/498586

43. Wu D, Shao D, Liu Z, Yu H, Wang J. The relationship of spatial distribution between multi-scale park green space and housing prices: a case study of the Central City of Suzhou. Chin Landsc Architect. (2018) 11:113–8 (in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6664.2018.11.023

44. Wu D, Shao D. Gradient difference of correlation between park green space and housing price in different service radius. J China Urban Forest. (2020) 4:50–4 (in Chinese). doi: 10.12169/zgcsly.2019.04.25.0001

45. Yang S. A Study on the Influence of Urban Park Location upon Housing Prices based on the Tiebout Choice Theory (Master's Thesis). Ming Chuan University, Taoyuan, Taiwan (2007).

46. Tan W, Liu L, Cui Y, Chen J, Lin F, Zhong Y, et al. The impact of accessibility of urban central parks on housing prices of Fuzhou. In: E3S Web of Conferences. Vol. 165. Changchun: EDP Sciences (2020).

47. Liu Q. Research on the impact of urban landscape accessibility on housing prices in the central area of Chongqing (Master's Thesis). Southwest University, Chongqing, China. (2021). doi: 10.27684/d.cnki.gxndx.2021.002903

48. Kim HS, Lee GE, Lee JS, Choi Y. Understanding the local impact of urban park plans and park typology on housing price: a case study of the Busan metropolitan region, Korea. Landsc Urban Plan. (2019) 184:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.12.007

49. Espey M, Owusu-Edusei K. Neighborhood parks and residential property values in Greenville, South Carolina. J Agric Appl Econ. (2001) 33:487–92. doi: 10.1017/S1074070800020952

50. Bark RH, Osgood DE, Colby BG, Halper EB. How do homebuyers value different types of green space? J Agric Resour Econ. (2011) 395−415. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.117210

51. Pandit R, Polyakov M, Sadler R. The importance of tree cover and neighbourhood parks in determining urban property values.In: 56th AARES Annual Conference. Fermantle, WA: Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society (2012).

52. Tan W, Chen T, Wang Q, Lin F, Huang Y, Cui Y, et al. Effects of urban park green space accessibility on house price:a case study of central district of Fuzhou City. J China Urban Forest. (2021) 1:66–71 (in Chinese).

53. Kolbe J, Wüstemann H. Estimating the value of urban green space: a hedonic pricing analysis of the housing market in cologne, Germany. Folia Oecon Stet. (2014). p. 43–58. doi: 10.13140/2.1.3777.1048

54. Cai W, Liu Z. The capitalized effect of park green space on residential housing prices in central district of Changchun. Hubei Agric Sci. (2017) 14:2768–72 (in Chinese). doi: 10.14088/j.cnki.issn0439-8114.2017.14.043

55. Bedell WB. Capitalization of Green Space and Water Quality Into Residential Housing Values (Master Thesis). University of Kentucky, Kentucky, United States (2018).

56. Yin H, Xu J, Kong F. Impact of the amenity value of urban green space on the price of house in Shanghai. Acta Ecol Sin. (2009) 29:4492–500 (in Chinese). doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1000-0933.2009.08.057

57. Qi J. A Study on the Amenity of Parks and Green Spaces in Anyang City Based on Hedonic Price Method (Master's Thesis). Sichuan Agricultural University, Ya'an (in Chinese) (2013).

58. Wen H, Zhang Y, Zhang L. Assessing amenity effects of urban landscapes on housing price in Hangzhou, China. Urban Forest Urban Greeni. (2015) 14:1017–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2015.09.013

59. Aliyu AA, Adamu H, Gambo MJ, Auwal U, Raymond D. Do neighbourhood parks and open space influence the values of surrounding housing Prices? A research review and synthesis. In: Book of Proceedings/Abstract and Programme: the 10th Academic Conference of Hummingbird Publications and Research International on Challenge and Prospects Vol.11 No.1 on 4th August, 2016-Conference Hall, Administrative Complex, Osun State University. Oso (2016).

60. Wu D, Guo Z, Chen H. Impact of lake landscape on urban residential property values in Nanjing. Resour Sci. (2008) 30:1503–9 (in Chinese).

Keywords: urban parks, green spaces, residence price, environmental health, healthy city

Citation: Chen K, Lin H, You S and Han Y (2022) Review of the impact of urban parks and green spaces on residence prices in the environmental health context. Front. Public Health 10:993801. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.993801

Received: 14 July 2022; Accepted: 22 August 2022;

Published: 07 September 2022.

Edited by:

Yibin Ao, Chengdu University of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Yang Chen, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaBingjie Yu, Southwest Jiaotong University, China

Copyright © 2022 Chen, Lin, You and Han. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuying You, c3lvdW9vQDE2My5jb20=

Kaida Chen1,2

Kaida Chen1,2 Shuying You

Shuying You