95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

COMMUNITY CASE STUDY article

Front. Public Health , 19 August 2022

Sec. Public Health Education and Promotion

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.958654

This article is part of the Research Topic Anti-Asian Racism and Public Health View all 24 articles

Erin Manalo-Pedro1,2*

Erin Manalo-Pedro1,2* Andrea Mackey1

Andrea Mackey1 Rachel A. Banawa1,2,3

Rachel A. Banawa1,2,3 Neille John L. Apostol1

Neille John L. Apostol1 Warren Aguiling1,4

Warren Aguiling1,4 Arleah Aguilar1

Arleah Aguilar1 Carlos Irwin A. Oronce1,2,5

Carlos Irwin A. Oronce1,2,5 Melanie D. Sabado-Liwag1,6

Melanie D. Sabado-Liwag1,6 Megan D. Yee1,7

Megan D. Yee1,7 Roy Taggueg1,8

Roy Taggueg1,8 Adrian M. Bacong1,9

Adrian M. Bacong1,9 Ninez A. Ponce1,2,3

Ninez A. Ponce1,2,3A critical component for health equity lies in the inclusion of structurally excluded voices, such as Filipina/x/o Americans (FilAms). Because filam invisibility is normalized, denaturalizing these conditions requires reimagining power relations regarding whose experiences are documented, whose perspectives are legitimized, and whose strategies are supported. in this community case study, we describe our efforts to organize a multidisciplinary, multigenerational, community-driven collaboration for FilAm community wellness. Catalyzed by the disproportionate burden of deaths among FilAm healthcare workers at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the accompanying silence from mainstream public health leaders, we formed the Filipinx/a/o Community Health Association (FilCHA). FilCHA is a counterspace where students, faculty, clinicians, and community leaders across the nation could collectively organize to resist our erasure. By building a virtual, intellectual community that centers our voices, FilCHA shifts power through partnerships in which people who directly experience the conditions that cause inequities have leadership roles and avenues to share their perspectives. We used Pinayism to guide our study of FilCHA, not just for the current crisis State-side, but through a multigenerational, transnational understanding of what knowledges have been taken from us and our ancestors. By naming our collective pain, building a counterspace for love of the community, and generating reflections for our communities, we work toward shared liberation. Harnessing the collective power of researchers as truth seekers and organizers as community builders in affirming spaces for holistic community wellbeing is love in action. This moment demands that we explicitly name love as essential to antiracist public health praxis.

“They say some stories need to wait to be toldBut I need a way to unfoldAll of the weight of the people before meWho never got chances to speak from they soul”–Ruby Ibarra, “Skies”

A critical component for health equity lies in the inclusion of structurally excluded voices, such as Filipinx/a/o Americans1 (FilAms) (1). Because FilAm invisibility is normalized, denaturalizing these conditions requires reimagining power relations regarding whose experiences are documented, whose perspectives are legitimized, and whose strategies are supported (2–4). To spark this reimagination, we begin with a reminder from Pinay rapper Ruby Ibarra of the multigenerational burden generated from the silencing of FilAm stories.

In this community case study, we describe our efforts to organize a multidisciplinary, multigenerational, community-driven collaboration for FilAm community health. Catalyzed by the disproportionate burden of deaths among FilAm healthcare workers at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the accompanying silence from mainstream public health leaders, we formed the Filipinx/a/o Community Health Association (FilCHA). FilCHA is a national public health organization dedicated to advancing health equity, justice, and wellbeing in the Filipinx/a/o community through community-driven, collaborative, and data-informed approaches.

FilCHA operates as a counterspace where students, faculty, clinicians, and community leaders collectively organize to resist our erasure, abolish oppressive structures, and promote our wellness. Wellness is the harmonizing of mind, body, emotion and spirit that connects self and community actualization (5, 6). By building a virtual, intellectual community that centers our voices, FilCHA shifts power toward people who directly experience the conditions that cause inequities have leadership roles and avenues to share their perspectives (7). We demonstrate the need for counterspaces as progressive values evolve in public health (8).

Current conceptions of antiracist public health praxis may not fully account for FilAm complexities. Partially due to racialization as Asian American model minorities, FilAms are infrequently included in structural racism research (9). Population-level analyses often invisibilize FilAms by neglecting to systematically collect racial/ethnic data and by aggregating Asian American subgroups (10). Upon disaggregation, traditional health indicators (e.g., high English proficiency, baccalaureate degree attainment, household income) do not correlate with positive health outcomes for FilAms who are more likely hypertensive, diagnosed with cancer, and disproportionately represented in healthcare COVID-19 deaths (1). More nuanced analyses that contextualize FilAm health are needed.

One such infrequently examined area in health research is FilAms' historical trauma, which stems from a turbulent colonial history with the United States (US) under the guise of benevolent assimilation (1, 11). The physical harm caused by the Philippine-American war resulted in the deaths of an estimated 20,000 Pilipino combatants and more than 200,000 civilians from combat and disease. As a means of cultural dispossession, generations of Pilipinos were then educated in a system “designed [for] the economic and political reality of American conquest” (12). The centrality of the US in early Pilipino migration and its evolution into a sophisticated system of federally-backed policies (e.g., the creation of the Overseas Employment Development Board in 1974) contribute to the continued economic reliance of the Philippines to export skilled labor out of the country (13), producing a global diaspora of displaced Pilipino families. As a survival strategy, FilAm families emphasized assimilation and acculturation. Across the US, even along the West and East coasts where most FilAms reside, FilAms may struggle to find community (2). Disrupting the multigenerational effects of this hegemonic miseducation and isolation requires reflection and action (14).

Praxis refers to the constant cycle of reflection and action with an underlying commitment to naming and transforming the world (14). This iterative approach is reflected in the National Campaign Against Racism which names racism, asks how it operates, and organizes and strategizes to dismantle it (15). Public Health Critical Race Praxis, an antiracist methodology for public health research and practice, focuses on contemporary patterns of racial relations, knowledge production, conceptualization and measurement, and action (16). Although each focus has shaped our health equity work, we center our case study on knowledge production, given the paucity of public health literature on FilAm knowledge producers.

Scholars of color face barriers to knowledge production in traditional academic arenas which are rooted in colonialism, dehumanization, imperialism, unfreedom, and isolation (3, 17, 18). Amidst rigorous academic and professional programs, students of color are frequently exhausted by the barrage of overt and covert reminders of their otherness (19). They often taken on the burden of remediating these harmful racial climates through uncompensated labor (e.g., diversity committees, student organizing) (20). Similarly, Black, Indigenous, Latine,2 and Asian American faculty have enumerated their own microaggressions, connecting these everyday assaults to poor health outcomes and the denial of tenure (21, 22). As such, racial campus climates have been detrimental for the FilAm faculty pipeline (23–25).

In addition to devaluing bodies of color, white supremacy also denigrates the knowledges of communities of color. One inconspicuous yet powerful form of epistemic oppression is epistemicide, which refers to the “killing of knowledge systems” through the erasure of non-Western ways of knowing (26). The historical theft and cooptation of non-Western knowledge systems has implications for today's prospective knowledge makers (3, 27). That is, when students of color are deprived from knowing “how autonomous, resourceful, and abundant their civilizations were prior to their relationship to colonialism… it becomes difficult to imagine a world beyond colonial domination” (28).

Yet imagination can illuminate alternative paths toward health equity (7). People who have been, historically and presently, structurally excluded from societal privilege possess the unique ontological and epistemic privilege to know, most intimately, the conditions of their oppression (29). Notwithstanding the increased attention to community-partnered participatory research as an approach to centering community voices in public health research (30), dismantling the dominant narratives that dehumanize FilAms “requires that the people experiencing/embodying realities of oppression retain narrative control—not the credentialed” (7). That is, the margins of society serve as a site of possibility and resistance for inhabitants (31)—not a brief stopover for “health equity tourists” who seek to co-opt recent streams of resources intended to address racial injustice (32). Indeed, health equity scholar Lisa Bowleg has argued for critical epistemologies as necessary to dismantle harmful narratives and radically change the underlying conditions that structure exclusion (33, 34).

How do alternate knowledges advance antiracist public health praxis? In this case study, we examine how the Filipina American feminist lens of Pinayism can explain the development of FilCHA by centering FilAm narratives.

We were compelled to create FilCHA as a counterspace because existing academic public health and governmental institutions had not sufficiently prioritized FilAm health on a national level in general, and COVID-19 disparities in particular. Counterspaces emerged as a concept at the intersection of critical race theory and education (35). Initially theorized as a response to negative racial campus climates, counterspaces provide a safe community for marginalized people to bring their full selves to collectively engage in meaning-making and transformative change (36, 37). Whether as formally enrolled students, curious researchers, or lifelong learners, we who identify as members of marginalized communities seek “spaces that would support [our] ideas, [our] research, and [our] commitments” (38).

Counterspaces offer respite from microaggressions, deficit framing, and erasure through affirming relationship building (35, 36). Socorro Morales, a Critical Race Feminista, defines counterspace as an intellectual place for transformation where marginalized people bring their full selves in their complexities to critically discuss their overlapping and distinct realities (37). That is, counterspaces disrupt the invisibility and isolation that people of color face in academic settings, akin to the pedagogy of collegiality through which students “[learn] about community organizing while actually being a community” (39). Stretching beyond the confines of a single course, however, counterspaces also resemble an academic home, inviting multiple generations of interdisciplinary scholars and community members to vulnerably share raw ideas, critically yet caringly offer feedback, and generate novel insights rooted in the common struggle for justice (38).

Thus, one strategy for advancing health equity is to create counterspaces that facilitate knowledge production and promote actions toward holistic wellness. Producing knowledge in counterspaces enables us to reflect on our own epistemologies, analyze and critique oppressive systems that threaten our wellness, and act toward liberation (15, 40).

To guide our inquiry, we turned to Pinayism, which offers a unique, intersectional standpoint on the dynamic inclusion/exclusion of FilAm voices. Originating in the 1920's, “Pinay” refers to the political identity of Filipinas in the United States (41). Ethnic studies professor Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales (42) conceptualized Pinayism as feminist praxis, connecting Pinay stories at the global, local, and personal levels to reveal the complexities of intersectionality for transformative change. Just as feminism is not limited to females, Pinayism is not limited to Pinays. Rather, Pinayism centers the experiences of Pinays to generate a deeper understanding of local issues by framing oppression globally and facilitating individuals' capacity to affect change (42). Thus, Pinayism aligns with recent calls to address contemporary public health crises by engaging in intersectional praxis (43).

As an individual and communal process of humanization, Pinayism offers a valuable perspective for deepening antiracist public health praxis. According to the decolonialist body of Sikolohiyang Pilipino (i.e., Filipino Psychology), colonialism ruptured kapwa, the Pilipino core value of unity with others, indicating a deep connection with and commitment to community (44–46). Pinayist scholars restore kapwa through a shared understanding of contemporary struggles through decolonial, feminist, and antiracist contexts (40). Critical kapwa pedagogy, a strategy for teaching FilAm students, builds on kapwa value as a pertinent approach for collective healing through humanization, wholeness, and decolonizing epistemologies (46). Other examples of scholarship related to community health include the colonial roots of chronic diseases in the FilAm community juxtaposed against the FilAm healthcare workforce (47); ethnic studies as community responsive wellness (5, 6); and antiracist mothering amidst the coronavirus pandemic (48).

Public health literature has yet to robustly engage Pinayism. Notably, scholar-activists Maglalang et al. (49) recently argued for infusing Asian American Studies into public health training to develop critical consciousness among future health educators and to enhance their capacity to address anti-Asian racism through practice. For example, Asian American Studies and feminist theory guided an empirical paper and revealed that family and economic considerations kept nurses in specific settings that increased COVID-19 exposure risk (50). However, explicit application of Pinayism to explain FilAm health inequities has yet to find its place within public health's peer-reviewed journals.3

Even when informed by historical context, health disparities scholarship often frames communities of color by their deficits (33, 51). In contrast, Pinayism aligns more closely with desire-based research (2), “intent on depathologizing the experiences of dispossessed and disenfranchised communities” (52). To generate a more complete story, Pinayism encourages self-determination through the individual and communal process of acknowledging pain, showing love, and engaging in reflection toward community actualization and liberation, as summarized by the equation, pain + love + reflection = liberation (40).

While initially articulating Pinayism as “pain + love = growth,” Tintiangco-Cubales also described it as a fluid concept focused on revolutionary action, self-affirming conduct, and a self-determining system (42). In keeping with valuing the multiplicity of Pinay experiences and the fluidity of self-determination, the elements of the equation remain unbound by rigid definitions to be imposed onto others. Rather, the intention is for Pinayists to engage in “deep self-reflection as a means toward collective liberation” (i.e., pain + love + reflection = liberation) (40).

As Pinay scholar-activists engaged with FilAm studies as a means for healing (46), the first and second authors proposed applying the lens of Pinayism to reflect on our involvement with FilCHA. We leveraged the Pinayism equation as an analytical tool for decomposing the elements that contributed to FilCHA as a liberatory space. Conscious of the tendency for FilAms to avoid conflict rooted in the deeply valued concept of pakikisama (i.e., getting along with others) (44), we chose to name our pain. Furthermore, to counter the primarily positivist and deficit-oriented field of public health, we also reflected upon our actions as love for our community. Lastly, to acknowledge the sociopolitical implications of historical trauma on contemporary struggles for health equity (53), we reflected on our humanizing practices in the context of the ongoing struggle for collective liberation.

For the Pinay “to name her scars… and to uncover its connections to her subjectivity” (54), both data and analytical lenses are grounded in Pinay experiences (48). We embrace the Critical Race Feminista concept of cultural intuition, which leverages both shared experiences and community memory to enhance our interpretation of data (55). Indeed positivist claims to objectivity are fundamentally inappropriate for feminist and intersectional epistemological analyses which posit that knowledge is socially constructed (33). Instead, rigor is evaluated by the logic used to link data to the stated propositions and addressing rival explanations for findings. Case studies on unusual cases emphasize departures from convention to reveal insights about the status quo (56). Similarly, examining the proposition that FilCHA serves as a counterspace reveals how mainstream systems of knowledge production in public health have hindered FilAm health research.

We drew on two forms of data collection to make sense of FilCHA's development. We reviewed documentation (e.g., emails, agendas, internal documents, social media) that chronicled our milestones. Concurrently, we reflected together on our process as active members and/or co-founders, and thus participant-observers, to facilitate our meaning-making of what transpired. The authorship group for this commentary includes five members of the inaugural FilCHA board, including senior researchers and current students. In fact, the majority of authors are graduate students or recent alumni from programs in public health, medicine, and sociology. Although we all identify as FilAms, each author's lens has been shaped by lived experiences in various regions of the US, tied to different familial contexts of migration.

We summarize our findings through the Pinayism process of pain + love + reflection = liberation.

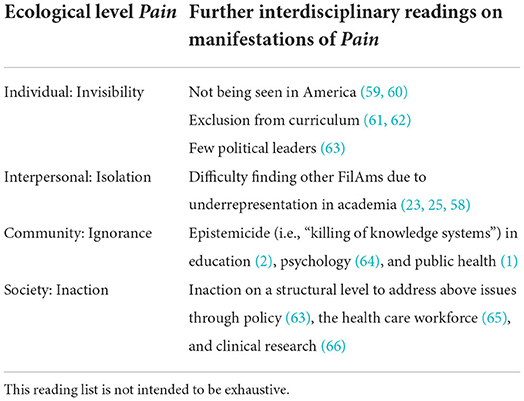

The Pain experienced by the FilAm community during the pandemic is multifaceted and rooted in a long history of colonial violence dating back to the 16th century under Spanish rule. Since the late 1500's, Spain, and subsequently the US from 1899 to 1946, exploited Philippine society, land, and people, uprooting connections to place, history, nature, spirit, ancestry, and community through various tools of colonialism, imperialism, and racism (57). As a result of this historical trauma, FilAms experience psychological and social hardships that ultimately manifest as health problems (1). Yet in pursuit of higher education to address these health problems, FilAm students often experience unrecognized marginalization, isolation from other FilAm students and mentors, siloed scholarship on FilAm issues which contribute to disciplinary ignorance, and institutional inaction to remedy said challenges (58). Ecologically, these harms further marginalization across individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels. In Table 1, we highlight a non-exhaustive list of interdisciplinary publications that historicize examples of Pain experienced by the FilAm community. Omitting this context, which otherwise would inform why knowledge production remains a challenge, further perpetuates the epistemicide that thwarts attempts to alleviate the Pain.

Table 1. Manifestations of pain experienced by the Filipinx/a/o American community by ecological level.

The pandemic exacerbated the ongoing disinvestment in FilAm health on a national and global scale. Early on, we witnessed a disproportionate number of deaths among FilAm healthcare workers. Despite FilAms comprising 4% of registered nurses, they made up nearly 30% of COVID-related deaths, according to the National Nurses United, a statistic underscored by the poignant digital memorial KANLUNGAN, which was curated by the transnational anti-imperialist feminist organization, AF3IRM.4 Against the backdrop of America's racial reckoning, anti-Asian hate crimes, and global exploitation of Filipino health care workers, the pandemic compounded the burdens of Pinay racial equity scholars (48). Acknowledging the multilayered pain inflicted on the FilAm community serves as the first step to adequately address the continued marginalization we have historically endured.

FilCHA's origins preceded the pandemic. Drawing upon a wealth of shared community resources [e.g., aspirational, resistant, navigational, social forms of community cultural wealth (67)], FilAms previously established local grassroots organizations and professional associations in medicine, nursing, psychology, education, and ethnic studies to reimagine ways to heal the bodies, minds, and souls of our community (40). In public health, however, there remained a void that pan-Asian organizations had not filled (68). Longing for an interprofessional space that centered our epistemologies in the discourse, we organized toward our collective liberation and healing in public health, as illustrated in the timeline in Figure 1 (40).

As the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated over the early months, high-profile media articles calling attention to the burden on FilAm nurses5 brought urgency and prompted FilAm public health scholars to connect and organize virtually. A shared recognition of the invisibility of FilAm COVID-19 disparities in cases and deaths culminated with a September 2020 letter to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Addressing the COVID-19 Vaccine Allocation Framework, the letter served as an act of resistance by critiquing the context of ongoing FilAm health inequities. In December 2020, signatories of the letter gathered to form an ad hoc group, the Filipinx/a/o COVID-19 Resource and Response Team (FilCOVID), largely inspired by the National Pacific Islander COVID-19 Response Team (69). Initially, we sought to educate and recommend policies for FilAm COVID-19 equity, yet our mission transformed into engaging in decolonization, self-determination, humanization, and relationship building within public health.

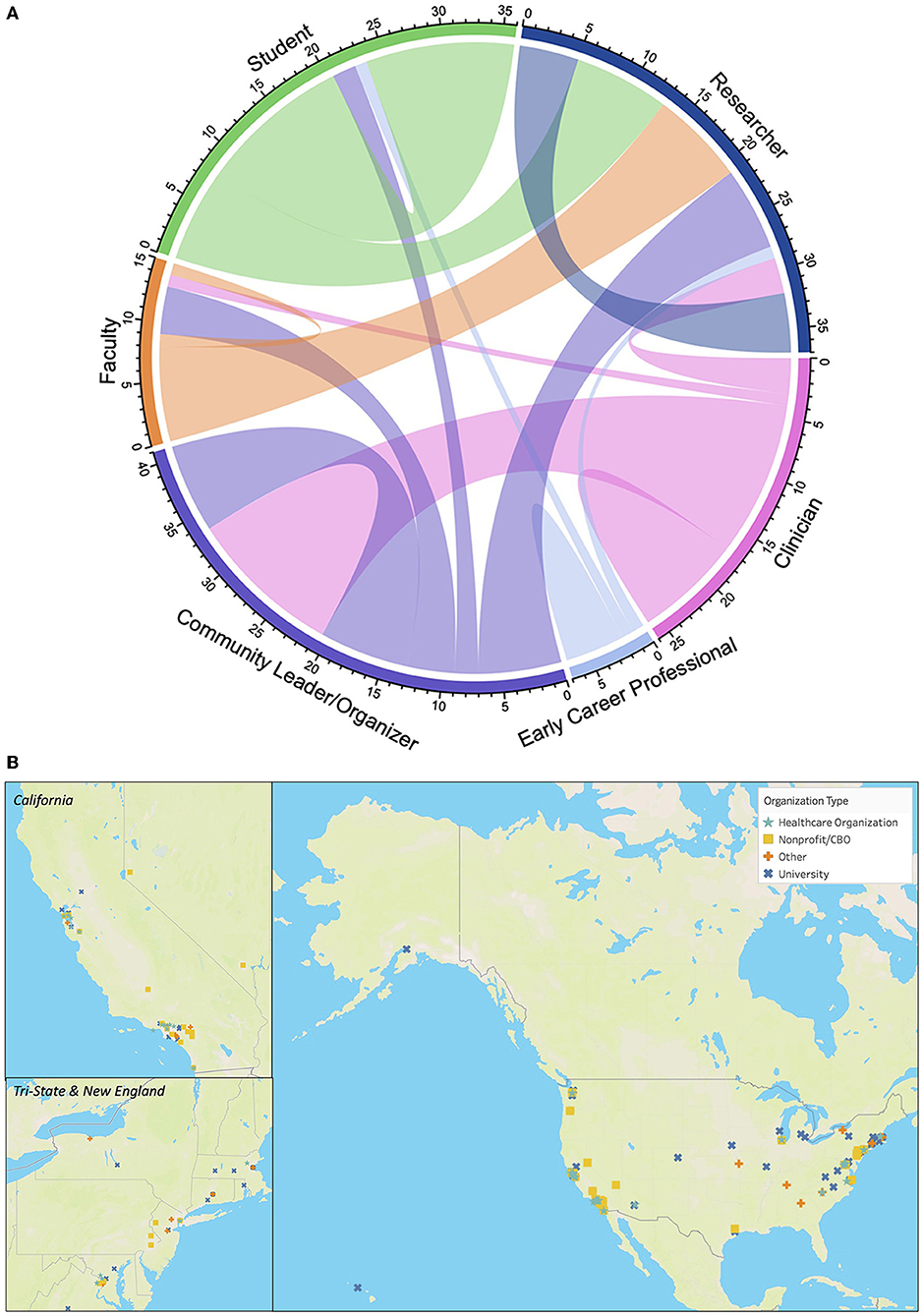

Through weekly Zoom meetings, inviting colleagues from other networks, and a growing social media presence, FilCOVID rapidly grew in size and influence. FilCOVID evolved into FilCHA, a transdisciplinary, interprofessional, and intergenerational organization consisting of over 100 members. Our members have diverse academic trainings and backgrounds in ethnic studies, history, sociology, anthropology, political science, epidemiology, policy, economics, social work, psychology, health services research, community health sciences, and medicine. FilCHA members include students, community leaders and organizers, researchers, clinicians and community-based direct service providers, faculty, and early career professionals, with many of our members serving in multiple roles. Figure 2A illustrates and quantifies the diversity in the roles of our members: out of 36 students, 8 are also researchers; out of 26 clinicians, 13 are also community leaders; out of 12 faculty members, 4 are also community leaders and organizers. As a virtual, intellectual space, FilCHA has become a hub for FilAm health equity scholar-activists where our Filipinx/a/o communities' epistemologies can be centered in our discussions and organizing.

Figure 2. Diversity and geographic reach of the Filipinx/a/o Community Health Association network. (A) Composition of Filipinx/a/o Community Health Association membership illustrating diversity and overlapping of roles. Chords that connect to the same role indicate members who serve one role. Chords that connect from one role to another represent members who serve in both roles. Clinician is inclusive of community-based direct service providers. Generated with circlize package in R (70). (B) Geographic distribution of organizations from more than 600 individuals who signed the January 2021 policy letter to the Biden-Harris Health Equity Task Force regarding COVID-19 and the Filipinx/a/o American community.

The influential impact and broad reach of our members enabled us to compile more than 600 signatures within a few days for a January 2021 policy letter to the Biden-Harris Health Equity Task Force regarding COVID-19 and the FilAm community.6 Illustrating the geographic spread of the signatories, Figure 2B displays the geographic location of the signatories' organization affiliations. The overwhelming response across multiple sectors (e.g., non-profit, academic, professional) provided us the momentum and validation needed to organize for health equity. The swift mobilization of our community emerged because of the combination of love, care, commitment, knowledge, responsibility, respect, and trust (71). The letter reached across different networks, sharing a recognition of pain but the power of the counternarrative. In a time of crisis, the letter offered context and space to understand, challenge, and transform established belief systems (72–74). Further, the letter provided new possibilities and connections for those on the margins.

Recognizing that COVID illustrated the broader issue of FilAm invisibility in public health discourse and practice, members clarified its mission. FilCOVID transitioned to the Filipinx/a/o Community Health Association (FilCHA), a collective non-profit space we created to honor our ancestors, share hope and joy, and individually and collectively heal by identifying holistic wellness through self-determination. We adopted a broader vision to ensure visibility, accurate data, and equitable allocation of resources for the Filipinx/a/o community, empowering new and existing movements to create sustainable healing.

By combining our interprofessional, multidisciplinary membership with a digital presence, FilCHA inhabits a unique space in the FilAm community. We are not directly affiliated with a specific academic institution. Rather, we pair the strengths of academic perspectives with a community focus and partner with other community-based organizations. This allows us to coordinate and build kapwa with each other nationally and outside of academic institutions that have not traditionally valued the importance of critical cultural production of engaged scholarship that expresses our own perspectives in public health. Benefiting from elders' expertise with incorporation, we formalized the national organization by acquiring 501(c)3 non-profit designation in January 2022.

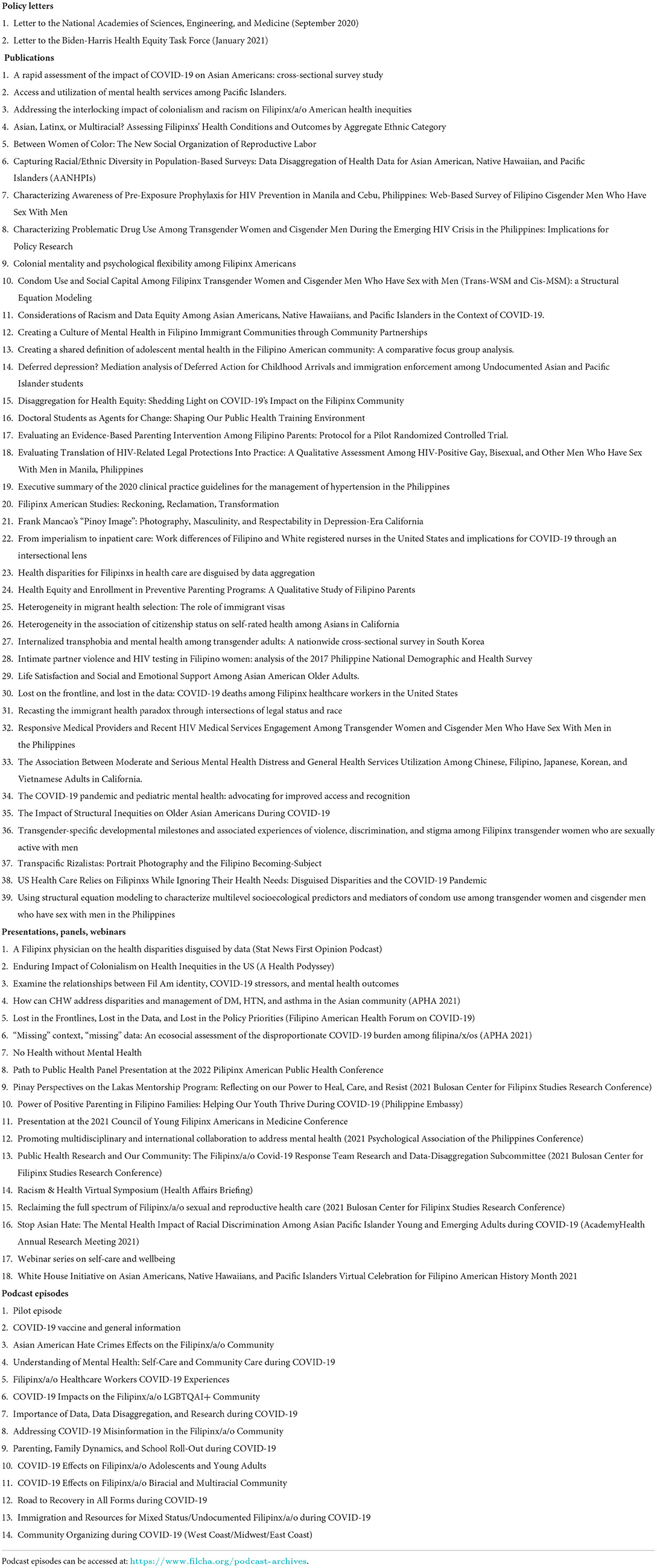

To overcome the erasure of FilAm knowledge in health equity discourse, we collectively redefined, restored and redistributed power by gathering and analyzing our own knowledge to raise visibility within the field of public health and the broader FilAm community. Table 2 lists knowledge produced by FilCHA members: policy letters, publications, presentations, and podcast episodes. Upon seeing the continued omission of FilAms from COVID-19 equity discussions, we collaboratively drafted policy letters in hopes of addressing structural change in the areas of vaccine allocation, data collection and disaggregation, and classification as underrepresented minorities, including our letter to the Biden-Harris Health Equity Task Force.

Table 2. Knowledge produced by Filipinx/a/o Community Health Association members, December 2020–May 2022.

In facilitating research on and with FilAms, FilCHA members published at least 39 articles since December 2020. Many of the publications emphasized the health and social needs of FilAms. Our multidisciplinary collaboration led to an article on colonialism and racism on FilAm health inequities in the Health Affairs special issue on racism and health (1). The infrequent integration of sociological and historical context, chronic disease, mental health, and policy relevance generated new research questions for future studies with the potential to tangibly improve FilAm health. Additionally, we developed community resources that have been fundamental for disseminating FilAm knowledge and strengthening future FilAm power relations: a publicly viewable bibliography of FilAm health articles and an email distribution list for members to share funding opportunities, policy updates, community-defined healing services, and study participant recruitment. An online repository for FilAm oral histories and other datasets is under development.

Leveraging extensive networks built over decades of organizing, we also engaged the broader FilAm community to cocreate knowledge through a funded podcast series, webinars, and presentations. We preserved experiences of FilAms at various intersections of oppression while highlighting strategies for healing. FilCHA decentered positivist approaches to research by uplifting kuwentuhan (talking story) through our 14-episode podcast series, titled “The Pilipinx/a/o Sharing Stories Together (PSST) Podcast.”7 PSST alludes to the sound that FilAms often make to get someone's attention. The podcast featured perspectives from clinicians, researchers, community organizers, creatives, youth, parents, undocumented immigrants, LGBTQI+, and multiracial FilAms. The podcast gained traction on social media platforms8; on Twitter, FilCHA's largest social media platform, 191 tweets about the podcast amassed over 204,600 impressions. Similarly, on Facebook 99 posts about the podcast reached 16,437 individuals. Our mental health webinars incorporated activities such as karaoke, cooking, and Zumba, reaching more than 2,000 individuals. Through more than a dozen presentations, we shared our ideas with diverse audiences including public health professionals, FilAm youth, and mental health professionals in the Philippines.

These collective successes were built upon the intellectual and emotional labor of prior rejections as individuals. One of the earliest collaborations started in May 2020. After connecting on Twitter, two FilCHA co-founders decided to draft an op-ed article on data disaggregation for COVID-19 data, centering their argument on the growing number of FilAm healthcare worker deaths. Days later, AF3IRM launched the KANLUNGAN tribute website and the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research launched the COVID-19 Race/Ethnicity and Risk Factors Dashboard. Enhanced with new data sources and a senior third author, the op-ed was submitted. Month after month, while the deaths of FilAm healthcare workers kept climbing, news outlets and scholarly journals rejected the op-ed. Facilitated through the senior author's media recognition, the article finally found its home accompanying KCET's Power & Health documentary9 in March 2021.

While this persistence may be admirable, it is also exhausting. In various committee meetings, several FilCHA members expressed similar frustrations over rejected publications, grant applications, and panel presentations that centered on FilAms. An established FilAm researcher shared that grant reviewers commented that studies that focused only on FilAms were not warranted. Rather than processing these setbacks individually, FilCHA created a space for being vulnerable, exposing common struggles, and sustaining each other despite setbacks. This unrecognized labor takes a toll. Similarly burdened, counterspaces have “nurtured what would become a growing lineage of U.S. Filipino education scholar-activists” (38). We extend this idea toward growing a lineage of U.S. FilAm scholar-activists for health equity.

Through FilCHA as a counterspace, we have built pathways toward collective healing. Transforming conditions to reach health equity requires continuous collective commitment to liberation from all oppression. Indeed, as a community-driven effort, sustaining counterspaces depends on individual and communal praxis. FilCHA engages in decolonization, humanization, self-determination, and relationship-building practices (40).

Acknowledging the legacies of colonialism on FilAm health within public health literature is just the first step toward decolonization. FilCHA seeks to advance self-determination and healing with other peoples who continue to be impacted by colonial legacies. For example, our contribution to the Health Affairs special issue on racism and health has sparked cross-racial conversations regarding anticolonialism (1). Alongside American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, and other Asian American scholars, our members have advocated for visibility through disaggregated data (10, 75, 76). This current paper attempts to bridge ethnic studies, critical race theory in education, and public health praxis. To transform public health, we continue to invest in cultivating health social movements, learning critical theories, decolonizing methods, and health promoting practices from antiracist scholars and community organizers across disciplines.

Driven by our shared humanity, we prioritize telling the stories of FilAms within and beyond FilCHA. The podcast was one of several ways we brought attention to the nuances of FilAm experiences (e.g., multiracial, undocumented, queer). We also spotlighted FilCHA members on social media platforms, highlighting reasons for joining, relevant projects, and experience with the COVID-19 vaccine. Additionally, in the scholarship we produced, we often referenced the KANLUNGAN tribute website to the more than 200 healthcare workers of Philippine descent who passed away from COVID-19. All of this is intentionally in contrast to the dominant epidemiological representations of people of color who are often presented as statistics devoid of context (77). As members of the FilAm community, we embody our ancestors' resistance and struggle, sharing experiences with those whose health outcomes we prioritize.

Moreover, FilCHA facilitates our self-determination by setting our own agenda and mobilizing our vast network to increase our impact. We share the common goal to serve, address, and answer FilAm community health and wellbeing needs. Covering the areas of research, policy, outreach, and mental health, FilCHA committees provide the infrastructure for supporting member-driven initiatives. Current collaborations include this manuscript, participation in the #WeCanDoThis campaign, online “Zoomba” workshop for wellbeing, administratively advocating for equitable health polices at the federal level, and intentionally mentoring rising public health leaders.

Finally, the relational culture within FilCHA signifies the ongoing reclamation of kapwa. In contrast to elitism and individualism, we welcome and support members at whichever stage they are in their journey. Decisions are consensus-driven, rather than defaulting to those with seniority or professional roles conventionally seen as most prestigious (e.g., physician). Though many members are credentialed, respect and familiarity are extended through the honorifics of “Ate,” “Tita,” or “Ninang” (older sister, auntie, or godmother) rather than “Doctor.” Having survived marginalization in their own careers, elders share their wisdom, networks, and resources. Opportunities for skill development (e.g., speaking at conferences, coauthoring manuscripts, and leading projects) are shared during virtual meetings and through online collaboration tools (e.g., Google Groups, Slack, and social media). Challenging dominant values that breed competition, FilCHA seeks to reunite our fellow FilAms by seeing ourselves in each other.

“There is power in seeing each other. …in hearing each other. …in speaking to each other. There is power in ‘us.' There is power because they cannot fathom what we can do together.” –Cee Carter and Korina M. Jocson (78).

The development of FilCHA demonstrates how community-driven efforts disrupt epistemicide, an overlooked expression of structural racism against Asian Americans. Through disciplinary self-critique, our case study advances public health praxis by articulating the need for counterspaces to facilitate self-determined knowledge production. Further, by leveraging Pinayism as our analytical tool, we exhibited how epistemic privilege aids our collective understanding of the complex barriers to health equity. We encourage a sincere love for the people toward a more humanizing public health.

As people affected by the legacy of colonialism, we, as public health scholar-activists, sought to recover our significance and “learn to love ourselves again” (79, 80). By naming our collective pain, building a counterspace for love of the community, and generating reflections for our communities, we work toward shared liberation. Analyzing the development of FilCHA through the lens of Pinayism guided our approach to understand our actions, not just in the current crisis State-side, but through a multigenerational, transnational understanding of what knowledges have been taken from us and our ancestors (27). Digital artifacts, such as meeting minutes, generated within counterspaces can help to illuminate differences from the normalized processes of knowledge production. Additionally, participant observation embraces reflexivity, acknowledges the situatedness of the researcher within the research, and promotes cultural intuition (55, 81). Counterspaces illuminate the possibilities for antiracist public health praxis by placing people of color at the center of knowledge production and case study as a method offers another tool for understanding the complexity of racism and antiracist public health praxis (56).

The racialization of FilAms as colonized “model minorities” without unmet health needs sparked the development of FilCHA. As an example of preparation meeting opportunity, the coronavirus pandemic catalyzed a critical mass of FilAm scholars and community leaders to engage in online conversations around the disproportionate burden among the FilAm community and their roots in colonial legacies. This ignited our agency and creativity to not only make meaning of our community's unequal exposure to COVID-19 but also comprehend the limited response from conventional public health organizations.

Exclusion from both mainstream public health efforts and conventional “minority health” initiatives to curb COVID-19 spurred us to act. FilCHA was birthed by connecting existing networks of FilAm community organizations and Asian American public health entities through our shared struggle to achieve holistic community wellbeing. In broader discussions of racial health equity, attention to FilAm health tends to waver between the omission altogether of Asian Americans from population health analyses, positioning as white-adjacent model minorities to denigrate other communities of color, and, less frequently, inclusion within disaggregated Asian American data (1). Indeed, education scholars have argued that the incessant need for FilAms to develop counterspaces is perpetuated by insidious, systemic underfunding and inequitable decision-making structures (2).

Liberation fundamentally requires an ongoing commitment to transform the spaces we occupy (82). Abolishing oppressive systems must be motivated by emotion (83). Love is enacted by sustaining each other and sharing the collective responsibility (71, 84). Efforts to address anti-Asian hate should also seek to cultivate love.

As a globally displaced diaspora, FilAms are undeniably complicit as settlers on stolen land (85). As we prioritize consciousness raising to highlight FilAm stories of resistance and struggle, how FilCHA relates to Indigenous people from the Philippines has yet to be determined.10 As the organization and its' membership grow, FilCHA aims to intentionally wrestle with the incommensurability of FilAm health and Indigenous sovereignty (85).

Through our ongoing process of (un)learning, we benefit from the intellectual work advanced by Indigenous scholar-activists [e.g., decolonizing methodologies (3), historical trauma (53, 86, 87), loss of culture (88), colonial schooling (89)]. We encourage anticolonial stances in public health literature in hopes that increased attention to colonialism as a determinant of health will yield more collective power and resources to disrupt it.

As a precursor to unsettling stolen land, we assert that we must learn to love ourselves, our people, and our culture, to cultivate the desire and means to reunite with our homeland. Notably, the exodus continues; 46,000 Pilipinos immigrated to the U.S. in 2018 (90). By engaging in self-determined antiracist praxis, we aim to make visible the mechanisms through which white supremacy and U.S. imperialism have and continue to maintain the conditions that separate FilAms from our wholeness and our potential for collective liberation.

Our case study advances the idea that antiracist public health praxis is both an individual and a collective process facilitated through counterspaces. This cannot be done in isolation and fundamentally contradicts public health's long held focus on individuals as the unit of analysis and the assumed neutrality of researchers. In solidarity with other communities that struggle for visibility, we offer lessons learned and recommendations for shifting attention to the margins through kapwa (Table 3).

We must interrogate how population-level approaches erase the experiences of structurally excluded groups, including FilAms. We push back on the notion that FilAm health is only worth studying or intervening upon when juxtaposed against whiteness (2). We commit to exposing the structures that reject grant proposals and scientific papers on the faulty logic that rationalize FilAms as undeserving of investment or attention. Rather, examining, enacting, and advocating for FilAm health is warranted because of our complexities and inherent deservingness. Multidisciplinary, community-led organizing for public health rooted in love for the people is essential for disrupting our continued erasure and promoting community wellness.

FilAms and other overlooked communities would benefit from institutionalized investment in interdisciplinary collaboration and self-determination. This paper briefly touched on a few strengths-based approaches [e.g., desire-based research (52)] and community-based healing [e.g., critical kapwa (46) and community responsive wellness (5)]. Numerous other ways of knowing exist. Scholarship on anti-Asian racism and public health could benefit from theories rooted in ethnic studies (91), critical race theory (92), and decolonizing methodologies (2).

The conditions surrounding FilCHA were unique but developing counterspaces for antiracist public health praxis is not only feasible but imperative for health equity. “Resistance should not be mistaken for remedy” (2) but rather an opportunity to engage in reflection on how public health must transform. Regardless of numeric representation, tackling health equity remains elusive if lived experiences of those students and community members are not genuinely valued as legitimate ways of knowing (33). Though not formally theorized as a counterspace, the National Cancer Institute's pre-doctoral Minority Training Program in Cancer Control Research has exemplified a humanizing space for graduate students of color to engage in collective meaning-making since 1999 (93). We recommend that health workforce diversity programs similarly prioritize the humanization of scholars of color and encourage public health educators to promote concepts from critical race theory of education (e.g., counterspace) and intersectional epistemologies (e.g., Pinayism) (7, 94).

Pinayism guided our realization that kapwa has been our strategy for survival. Using critical kapwa for our collective healing restores our shared power, driven not by obligation but a loving commitment to community (46). FilCHA emerged out of an interconnected network of relationships. As with deep systems changes that originate from small interactions and relationship building, it was through the tweets, letters, and conversations that built FilCHA as a counterspace to humanize, heal, and decolonize. FilCHA has become a site for exposing struggle and reclaiming collective power.

The field of public health is not immune to the white supremacist culture and structures upon which the United States was founded. Dismantling anti-Asian racism requires more than documenting incidence rates of overt hate. Harnessing the collective power of researchers as truth seekers and organizers as community builders in affirming spaces for holistic community wellbeing is love in action. This moment demands that we explicitly name love as essential to antiracist public health praxis.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This work was supported by the Pilipinx/a/o Sharing Stories Together (PSST) Podcast series would not have occurred without the Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations, whose administrative support and prior success with the Koviki Talk Podcast for Pacific Islanders led to a grant through the Walmart Foundation. Open access publication fees were provided by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. RB reports support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as part of the Los Angeles Area Health Services Research Training Program (T32 Predoctoral Fellowship) during the conduct of this study. CO reports support from the Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations through the VA Advanced Health Services Research Fellowship, during the conduct of the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The contents do not represent the views of the authors' employer or institution, including those of the US Department of Veteran Affairs and the US government.

1. ^We use “Pilipino” to refer to people with ancestral ties to the regions of Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao residing in what is now known as the Republic of the Philippines. We use the term “Filipinx/a/o American” as a gender-inclusive term for people with Philippine ancestry residing in what is now known as the United States of America. We also incorporate “Pinay” as a political reference to the inseparability of U.S. imperialism on Filipinas in the United States.

2. ^We use “Latine” to refer to people with ancestral ties to the region now known as Latin America. Latine was introduced by queer, non-binary, and feminist Spanish speakers to push back against gender and heteronormative bias (https://callmelatine.com/2020/12/14/an-open-letter-to-allies/).

3. ^PubMed search for “Pinayism” produced 0 results. “Pinay” yielded 2 results that were not related to the author last name “Pinay”: one was a 2010 article on action research in reference to a Filipino Canadian domestic worker organization and the other was a 2021 reflection from a Pinay social worker that did not explicitly reference “Pinayism.”

4. ^https://www.kanlungan.net/

5. ^https://www.statnews.com/2020/04/28/coronavirus-taking-outsized-toll-on-filipino-american-nurses/, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-07-21/filipino-americans-dying-covid, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/largest-share-migrant-nurses-entire-u-s-filipino-community-hit-n1237327

6. ^http://tiny.cc/filcovidletter

7. ^https://www.filcha.org/podcast-archives

8. ^https://twitter.com/filxao_cha, https://instagram.com/filxao_cha, https://www.facebook.com/FilxaoCHA

9. ^https://www.kcet.org/shows/power-health/disaggregation-for-health-equity-shedding-light-on-covid-19s-impact-on-the-filipinx-community

1. Sabado-Liwag MD, Manalo-Pedro E, Taggueg R, Bacong AM, Adia A, Demanarig D, et al. Addressing the interlocking impact of colonialism and racism on Filipinx/a/o American health inequities. Health Aff. (2022) 41:289–95. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01418

2. Maramba DC, Curammeng ER, Hernandez XJ. Critiquing empire through desirability: A review of 40 years of Filipinx Americans in education research, 1980 to 2020. Rev Educ Res. (2021) 2021:003465432110608. doi: 10.3102/00346543211060876

3. Smith LT. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous People. 2nd ed. London: Zed Books Ltd (2012).

4. Collins PH. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. 2nd ed. London: Routledge (2002).

5. Macatangay G, Tintiangco-Cubales A, Duncan-Andrade J. On Becoming Community Responsive: Centering Wellness in the Educational Paradigm-Community Responsive Education. Community Responsive Education (2020).

6. Tintiangco-Cubales A, Duncan-Andrade J. Chapter 2: Still fighting for ethnic studies: the origins, practices, and potential of community responsive pedagogy. Teach Coll Rec Voice Scholarsh Educ. (2021) 123:1–28. doi: 10.1177/016146812112301303

7. Petteway RJ. Poetry as Praxis + “Illumination”: Toward an epistemically just health promotion for resistance, healing, and (re)imagination. Health Promot Pract. (2021) 22:20S−6. doi: 10.1177/1524839921999048

8. Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. Commentary: Just what is critical race theory and what's it doing in a progressive field like public health? Ethn Dis. (2018) 28(Supp 1):223. doi: 10.18865/ed.28.S1.223

9. Shah NS, Kandula NR. Addressing Asian American misrepresentation and underrepresentation in research. Ethnicity Dis. (2020) 30:513–6. doi: 10.18865/ed.30.3.513

10. Gee GC, Morey BN, Bacong AM, Doan TT, Penaia CS. Considerations of racism and data equity among asian americans, native hawaiians, and pacific islanders in the context of cOVID-19. Curr Epidemiol Rep. (2022) 2022:0123456789. doi: 10.1007/s40471-022-00283-y

11. Sotero M. A conceptual model of historical trauma: implications for public health practice and research. J Health Dispar Res Pract. (2006) 1:93–108. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1350062

13. Cabato DM. A note on the Philippine policy on managing migration. Philipp Labor Rev. (2006) 30:2–16.

15. Jones CP. Toward the science and practice of anti-racism: launching a national campaign against racism. Ethn Dis. (2018) 28(Supp 1):231. doi: 10.18865/ed.28.S1.231

16. Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. The public health critical race methodology: Praxis for antiracism research. Soc Sci Med. (2010) 71:1390–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.030

17. Patton LD. Disrupting postsecondary prose: toward a critical race theory of higher education. Urban Educ. (2016) 51:315–42. doi: 10.1177/0042085915602542

18. Rodríguez D. Racial/colonial genocide and the “Neoliberal academy”: In excess of a problematic. Am Q. (2012) 64:809–13. doi: 10.1353/aq.2012.0054

19. Gwayi-Chore MC, Del Villar EL, Fraire LC, Waters C, Andrasik MP, Pfeiffer J, et al. “Being a person of color in this institution is exhausting”: Defining and optimizing the learning climate to support diversity, equity, and inclusion at the University of Washington School of Public Health. Front Public Heal. (2021) 9:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.642477

20. Lerma V, Hamilton LT, Nielsen K. Racialized equity labor, university appropriation and student resistance. Soc Probl. (2020) 67:286–303. doi: 10.1093/socpro/spz011

21. Niemann YF, Gutiérrez y Muhs G, Gonzalez CG. Presumed Incompetent II: Race, Class, Power, and Resistance of Women in Academia. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press (2020). doi: 10.7330/9781607329664

22. Linh K, Valverde C, Dariotis WM. Fight the Tower: Asian American Women Scholars' Resistance and Renewal in the Academy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press (2019).

23. Maramba DC, Nadal KL. Exploring the Filipino American faculty pipeline: implications for higher education and Filipino American college students. In Maramba DC, Bonus R, editors. The “Other” Students: Filipino Americans, Education and Power. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing Inc. (2013).

24. Matias CE. Ripping our hearts: three counterstories on terror, threat, and betrayal in U.S. universities. Int J Qual Stud Educ. (2020) 33:250–62. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2019.1681546

25. Bui LT. On the experiences and struggles of Southeast Asian American academics. J Southeast Asian Am Educ Adv. (2021) 16:e1218. doi: 10.7771/2153-8999.1218

26. Hall BL, Tandon R. Decolonization of knowledge, epistemicide, participatory research and higher education. Res All. (2017) 1:6–19. doi: 10.18546/RFA.01.1.02

27. Coloma RS, Hsieh B, Poon OY, Chang S, Choimorrow SY, Kulkarni MP, et al. Reckoning with anti-asian violence: racial grief, visionary organizing, and educational responsibility. Educ Stud - AESA. (2021) 57:378–94. doi: 10.1080/00131946.2021.1945607

28. Camangian PR, Cariaga SM. Social and emotional learning is hegemonic miseducation: students deserve humanization instead. Race Ethn Educ. (2021) 2021:1–21. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2020.1798374

29. Sweet PL. Who Knows? Reflexivity in feminist standpoint theory and bourdieu. Gend Soc. (2020) 34:922–50. doi: 10.1177/0891243220966600

30. Chandanabhumma PP, Duran BM, Peterson JC, Pearson CR, Oetzel JG, Dutta MJ, et al. Space within the scientific discourse for the voice of the other? Expressions of community voice in the scientific discourse of community-based participatory research. Health Commun. (2020) 35:616–27. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2019.1581409

31. Hooks B. Marginality as a site of resistance. In: Ferguson R, Gever M, Minh-ha TT, West C, Tucker M, editors. Out There: Marginalization and Contemporary Cultures. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (1990).

32. Lett E, Adekunle D, McMurray P, Asabor EN, Irie W, Simon MA, et al. Health equity tourism: ravaging the justice landscape. J Med Syst. (2022) 46:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10916-022-01803-5

33. Bowleg L. “The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house”: Ten critical lessons for black and other health equity researchers of color. Heal Educ Behav. (2021) 48:237–49. doi: 10.1177/10901981211007402

34. Bowleg L. Towards a critical health equity research stance: why epistemology and methodology matter more than qualitative methods. Heal Educ Behav. (2017) 44:677–84. doi: 10.1177/1090198117728760

35. Solórzano DG, Ceja M, Yosso T. Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate: the experiences of African American college students. J Negro Educ. (2000) 69:60–73. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2696265

36. Allen WR, Solórzano DG. Affirmative action, educational equity and campus racial climate: a case study of the University of Michigan law school. Berkeley La Raza Law J. (2001) 821:97. doi: 10.15779/Z388D40

37. Morales S. Re-defining Counterspaces: New Directions and Implications for Research and Praxis. Los Angeles, CA (2017).

38. Solórzano DG. My journey to this place called the RAC: Reflections on a movement in critical race thought and critical race hope in higher education. Int J Qual Stud Educ. (2022) 2022:1–12. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2022.2042613

39. Chávez V, Turalba RAN, Malik S. Teaching public health through a pedagogy of collegiality. Am J Public Health. (2006) 96:1175–80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062950

40. Tintiangco-Cubales A, Sacramento J. Pin[a/x]yism Revisited. In Amorao AS, Kandi DK, Soriano J, editors. Closer to Liberation: Pin[a/x]y Activism in Theory and Practice. San Diego, CA: Cognella Academic Publishing (2022).

41. Mabalon DB. Little Manila Is in the Heart: The Making of the Filipina/o American Community in Stockton, California. Durham: Duke University Press (2013) doi: 10.1515/9780822395744

42. Tintiangco-Cubales A. Pinayism. In: Pinay Power : Peminist Critical Theory : Theorizing the Filipina American Experience. New York, NY: Routledge (2005).

43. Bowleg L. Evolving intersectionality within public health: From analysis to action. Am J Public Health. (2021) 111:88–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306031

44. David EJR, Sharma DKB, Petalio J. Losing Kapwa: Colonial legacies and the Filipino American family. Asian Am J Psychol. (2017) 8:43–55. doi: 10.1037/aap0000068

45. Pe-Pua R, Protacio-Marcelino E. Sikolohiyang Pilipino (Filipino psychology): A legacy of Virgilio G. Enriquez. Asian J Soc Psychol. (2000) 3:49–71. doi: 10.1111/1467-839X.00054

46. Desai M. Critical “Kapwa”: Possibilities of collective healing from colonial trauma. Educ Perspect. (2016) 48:34–40.

47. Magbual RS, Daus-Magbual RR. The health of Filipina/o America: Challenges and opportunities for change. In: Yoo GJ, Le MN, Oda AY, editors. Handbook of Asian American Health. New York, NY: Springer New York (2013). doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-2227-3_4

48. Matias C, Tintiangco-Cubales A, Jocson K, Sacramento J, Buenavista TL, Daus-Magbual AS, et al. Raising love in A time of lovelessness: kuwentos of pinayist motherscholars resisting COVID-19's Anti-Asian racism. Peabody J Educ. (2022) 2022:1–20. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2022.2055886

49. Maglalang DD, Peregrina HN, Yoo GJ, Le M-N. Centering ethnic studies in health education: lessons from teaching an Asian American community health course. Health Educ Behav. (2021) 48:371–5. doi: 10.1177/10901981211009737

50. Nazareno J, Yoshioka E, Adia AC, Restar A, Operario D, Choy CC. From imperialism to inpatient care: Work differences in characteristics and experiences of Filipino and white registered nurses in the United States and implications for COVID-19. Gender Work Organ. (2021) 28:1426–46. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12657

51. Fleming PJ. The importance of teaching history of inequities in public health programs. Pedagog Heal Promot. (2020) 2020:237337992091522. doi: 10.1177/2373379920915228

52. Tuck E. Suspending damages. Harv Educ Rev. (2009) 79:409–28. doi: 10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15

53. Hartmann WE, Wendt DC, Burrage RL, Pomerville A, Gone JP. American indian historical trauma: Anticolonial prescriptions for healing, resilience, and survivance. Am Psychol. (2019) 74:6–19. doi: 10.1037/amp0000326

54. Nievera-Lozano M-AN. The pinay scholar-activist stretches: A Pin@y decolonialist standpoint. Ninet Sixty Nine. (2013) 2:1. Available online at: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6nj877c0

55. Delgado Bernal D. Using chicana feminist epistemology in educational research. Harvard Educ Rev. (1998) 68:55–82. doi: 10.17763/haer.68.4.5wv1034973g22q48

56. Yin RK. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc. (2018).

57. Mendoza SL. Back from the Crocodile's Belly: Christian formation meets indigenous resurrection. HTS Teol Stud/Theol Stud. (2017) 73:1–8. doi: 10.4102/hts.v73i3.4660

58. Nadal KL, Pituc ST, Johnston MP, Esparrago T. Overcoming the model minority myth: Experiences of Filipino American graduate students. J Coll Stud Dev. (2010) 51:694–706. doi: 10.1353/csd.2010.0023

59. Cordova F. Filipinos, Forgotten Asian Americans : A Pictorial Essay, 1763-circa 1963. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Pub. Co. (1983).

60. Campomanes O V. The new empire's forgetful and forgotten citizens: unrepresentability and unassimilability in Filipino-American postcolonialities. Hitting Crit Mass. (1995) 2:2.

61. Maramba DC, Bonus R. The “Other” Students : Filipino Americans, Education, and Power. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing Inc. (2013).

62. Halagao PE. Holding up the mirror: The complexity of seeing your ethnic self in history. Theory Res Soc Educ. (2004) 32:459–83. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2004.10473265

63. de Leon ES, Daus GP. Filipino American political participation. Polit Groups Identities. (2018) 6:435–52. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2018.1494013

64. David EJR, Nadal KL, del Prado A. S.I.G.E.!: Celebrating Filipina/x/o American psychology and some guiding principles as we “go ahead”. Asian Am J Psychol. (2022) 13:1–7. doi: 10.1037/aap0000277

65. Oronce CIA, Adia AC, Ponce NA. US health care relies on filipinxs while ignoring their health needs. JAMA Heal Forum. (2021) 2:e211489. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1489

66. Ð*oàn LN, Takata Y, Sakuma KLK, Irvin VL. Trends in clinical research including Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander participants funded by the US National Institutes of Health, 1992 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open. (2019) 2:197432. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7432

67. Yosso TJ. Whose culture has capital? A Critical Race Theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethn Educ. (2005) 8:69–91. doi: 10.1080/1361332052000341006

68. Nadal KL. Pilipino American identity development model. J Multicult Couns Devel. (2004) 32:45–62. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1912.2004.tb00360.x

69. Morey BN, Tulua'Alisi, Tanjasiri SP, Subica AM, Keawe'aimoku Kaholokula J, Penaia C, et al. Structural racism and its effects on native hawaiians and pacific islanders in the united states: issues of health equity, census undercounting, and voter disenfranchisement. AAPI Nexus J Asian Am Pacific Islanders Policy, Pract. (2020) 17:1. Available online at: http://www.aapinexus.org/2020/11/24/structural-racism-and-its-effects-on-native-hawaiians-and-pacific-islanders/

70. Gu Z, Gu L, Eils R, Schlesner M, Brors B. Circlize implements and enhances circular visualization in R. Bioinformatics. (2014) 30:2811–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu393

72. Delgado R. Storytelling for oppositionists and others : a plea for narrative. Mich Law Rev. (1989) 87:2411–41. doi: 10.2307/1289308

73. Solórzano DG, Yosso TJ. Critical race methodology: counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qual Inq. (2002) 8:23–44. doi: 10.1177/1077800402008001003

74. Lawson R. Critical race theory as praxis: a view from outside the outside. Howard Law J. (1995) 38:353–70.

75. Penaia CS, Morey BN, Thomas KB, Chang RC, Tran VD, Pierson N, et al. Disparities in Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander COVID-19 mortality: A community-driven data response. Am J Public Health. (2021) 111:S49–52. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306370

76. Soon NA, Akee R, Kagawa M, Morey BN, Ong E, Ong P, et al. Counting race and ethnicity for small populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. AAPI Nexus J Asian Am Pacific Islanders Policy Pract. (2020) 17:1. Available online at: http://www.aapinexus.org/2020/09/18/article-counting-race-and-ethnicity-for-small-populations-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

77. Petteway RJ. Something something something by race, 2021. Int J Epidemiol. (2022) 2022:1–2. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyac010

78. Carter C, Jocson KM. Untaming/untameable tongues: methodological openings and critical strategies for tracing raciality. Int J Res Method Educ. (2022) 2022:1–14. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2022.2043843

79. Strobel LM. Coming Full Circle : The Process of Decolonization Among Post-1965 Filipino Americans. Quezon City: Giraffe Books (2001).

80. Tintiangco-Cubales A, Halagao PE, Cordova JMT. Journey ‘back over the line': critical pedagogies of evaluation. J Multidiscip Eval. (2020) 16:20−37. Available online at: https://journals.sfu.ca/jmde/index.php/jmde_1/article/view/655

81. Berger R. Now I see it, now I don't: researcher's position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual Res. (2015) 15:219–34. doi: 10.1177/1468794112468475

82. Buenavista TL, Cariaga S, Curammeng ER, McGovern ER, Pour-Khorshid F, Stovall DO, et al. A praxis of critical race love: toward the abolition of cisheteropatriarchy and toxic masculinity in educational justice formations. Educ Stud - AESA. (2021) 57:238–49. doi: 10.1080/00131946.2021.1892683

83. Matias CE, Allen RL. Amplifying messages of love in critical race theory do you feel me? J Educ Found. (2016) 29:5–28. Available online at: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eue&AN=125890471&site=ehost-live

84. Espinoza D, Narruhn R. “Love and Prayer Sustain Our Work” building collective power, health, and healing as the community health board coalition. Genealogy. (2020) 5:3. doi: 10.3390/genealogy5010003

85. Tuck E, Yang KW. Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization Indig Educ Soc. (2012) 1:1–40. Available online at: https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630

86. Walters KL, Mohammed SA, Evans-Campbell T, Beltrán RE, Chae DH, Duran B. Bodies don't just tell stories, they tell histories: Embodiment of Historical Trauma among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Du Bois Rev. (2011) 8:179–89. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X1100018X

87. Brave Heart MYH, Chase J, Elkins J, Altschul DB. Historical trauma among Indigenous peoples of the Americas: Concepts, research, and clinical considerations. J Psychoactive Drugs. (2011) 43:282–90. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.628913

88. Whitbeck LB, Adams GW, Hoyt DR, Chen X. Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian people. Am J Community Psychol. (2004) 33:119–30. doi: 10.1023/B:AJCP.0000027000.77357.31

89. Solomon TGA, Starks RRB, Attakai A, Molina F, Cordova-Marks F, Kahn-John M, et al. The generational impact of racism on health: voices from American Indian communities. Health Aff. (2022) 41:281–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01419

90. Budiman A. Key Findings About U.S. Immigrants. Pew Research Center. (2020). Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/ (accessed May 31, 2022).

91. Nham K, Huynh J. Contagious heathens : exploring racialization of COVID-19 and Asians through stop AAPI hate incident reports. AAPI Nexus J Asian Am Pacific Islanders Policy Pract. (2020) 17:1. Available online at: http://www.aapinexus.org/2020/11/13/article-contagious-heathens-exploring-racialization-of-covid-19-and-asians-through-stop-aapi-hate-incident-reports/

92. Bacong AM, Nguyen A, Hing AK. Making the invisible visible : the role of public health critical race praxis in data disaggregation of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. AAPI Nexus J Asian Am Pacific Islanders Policy, Pract. (2020) 17:1. Available online at: http://www.aapinexus.org/2020/09/18/article-making-the-invisible-visible-the-role-of-public-health-critical-race-praxis-in-data-disaggregation-of-asian-americans-and-pacific-islanders-in-the-midst-of-the-covid-19-pandemic/

93. Pasick RJ, Kagawa-Singer M, Stewart SL, Pradhan A, Kidd SC. The minority training program in cancer control research: impact and outcome over 12 years. J Cancer Educ. (2012) 27:443–9. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0375-7

Keywords: Pinayism, racism and antiracism, counterspaces, critical race theory, health equity, Filipino, Public Health Critical Race Praxis, community organizing & grassroots development

Citation: Manalo-Pedro E, Mackey A, Banawa RA, Apostol NJL, Aguiling W, Aguilar A, Oronce CIA, Sabado-Liwag MD, Yee MD, Taggueg R, Bacong AM and Ponce NA (2022) Learning to love ourselves again: Organizing Filipinx/a/o scholar-activists as antiracist public health praxis. Front. Public Health 10:958654. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.958654

Received: 31 May 2022; Accepted: 02 August 2022;

Published: 19 August 2022.

Edited by:

Anne Saw, DePaul University, United StatesReviewed by:

Michelle V. Porche, University of California, San Francisco, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Manalo-Pedro, Mackey, Banawa, Apostol, Aguiling, Aguilar, Oronce, Sabado-Liwag, Yee, Taggueg, Bacong and Ponce. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Erin Manalo-Pedro, ZW1hbmFsb0BnLnVjbGEuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.